Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation

Uploaded by

paperocamilloCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation

Uploaded by

paperocamilloCopyright:

Available Formats

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation

Author(s): János Fügedi

Source: Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae , 2003, T. 44, Fasc. 3/4

(2003), pp. 393-410

Published by: Akadémiai Kiadó

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/25047390

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Akadémiai Kiadó is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studia

Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation

J?nos F?GEDI

Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

Budapest

Abstract: It can be stated that dance notation was proved to be an established tool for

dance research and dance education in understanding and analyzing movement. This

theorem is especially valid in cases where, the structure of dance is amorphous, the

units of movement sequences differ from that of the accompanying music, the tempo of

the dance is high. Dance notation is used rather isolated in the field of traditional dance

in Hungary, mainly in dance research. In the light of the research introduced above it is

highly recommended to introduce dance notation in research, education, aesthetics and

criticism in the other genres of dance.

Keywords: dance notation, education, movement cognition

Introduction

The vast majority of our movements is acquired by learning, especially great

effort is spent on movement skills such as dancing - still these movements are

performed without consciousness. Because of this automated unconscious

ness one meets great difficulties in verbally formulating the characters, struc

ture, the manner of exact performance of movements, that is including them in

cognitive process. In spite of the fact that consciousness is a base of both sci

ence and education dealing with movement, unfortunately a conceptual frame

is generally missing even from the expert thinking which would be able to de

fine movement adequately on the level of consciousness. The intention of this

study is to prove that in case of dance this deficiency can be helped by the

means of dance notation and its supporting movement analytical tools.

The dance notation which the central feature of the present investigation is

a young science, hardly looking back a hundred years of past. The dancer's

movement is identified by symbols, in an abstract way in this system. Because

of its abstract nature and its resemblance of a language its use is not so general

in the dance world (among teachers, researchers and artists) such as the nota

tion in music. Our experience is that many dance experts regard dance nota

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003, pp. 393-410

0039-3266/2003/$ 20.00 ? 2003 Akad?miai Kiad?, Budapest

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

394 J?nos F?gedi

tion with reservations, especially because of its complicated syntax and its

strict - conceptualizing movement at conscious level. The consequences are

expected to prove that movement consciousness is the main advantage of a

dance notation by which cognitive procedure can be performed on dance.

To prove the importance of movement consciousness, great attention is

paid to the theories and experimental results in cognitive psychology, and that

of motor learning are surveyed as well. After sketching the movement cogni

tive background the notion, history and forms of application of dance notation

are shortly introduced. It is followed by the discussion of an experiment and

the analysis of results.

Human movement as a procedural knowledge

One of the most basic and frequently used human skills, the motor or

psychomotor skill is regarded by Gardner (1983) a significant form of human

intelligence. The cognitive psychology divides knowledge to procedural and

declarative types (Anderson 1980). Annett ( 1996) thinks that the motor skill is

a typical procedural knowledge, which Ferrari (1996) believes to be acquired

by imitative-observational ways. The procedural knowledge is usually out of

the domain of the consciousness, verbally cannot be expressed or with great

difficulties while the declarative knowledge behaves quite the contrary: ver

bally can be expressed easily and is the field of consciousness.

In connection with movement performance under the line of conscious

ness 19th century researcher William James (1890) stated that "habit dimin

ishes the conscious attention" with which the discreet motor sequences are

performed. James called attention that when the sequence is in the early stages

of learning there is a strong cognitive influence. But late in the practice, when

the action becomes "habitual", once started, the well-integrated motor chain is

run off without conscious awareness or intervention; the movement is auto

matic, as is common to say.1

The most widespread cognitive psychological approach to human move

ment is Schmidt's (1975) schema theory. Schmidt (1975) proposed that a fun

damental aspect of the learning of motor skills involved the acquisition of

schemata that define the relationships among the information involved in the

production and evaluation of motor responses. The schema theory has three

major components : the generalized motor program, the recall schema and the

recognition schema. The generalized motor program is an abstract memory

1 A diverse set of psychologists have endorsed a version of the hypothesis in recent times: cognitive

psychologists (Miller, Galanter and Pribam 1960), behaviorist (Kimble and Perlmuter 1970), developmen

tal psychologists (McCabe 1979), differential psychologists (Fleishman and Hempel 1955), and motor

learning theorists (Adams 1971 ; Fitts and Posner 1967; Schmidt 1975).

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 395

structure that causes movement to occur. It can be thought of as a program that

governs a given class of movements requiring a common movement pattern.

In order to achieve a desired outcome, an independent memory state, the recall

schema selects the parameters for executing the generalized motor program

properly. And at last, another independent memory state, the recognition

schema is responsible for the response evaluation.

Movement cognition and the conscious knowledge

about human movement

Research on knowledge representation stated that the knowledge structure

(such as plans, descriptions, definitions, sch?mas, prototypes) represent ge

neric conceptions in different levels of abstraction.2 Applying the theories of

knowledge representation stemming from the fields of cognitive sciences to

motor skill, many researchers (Bandura 1969; Adams 1971; Schmidt 1975;

Newell and Barclay 1982) came to the conclusion that memory stores the in

formation on movement in terms of generic concepts as well. According to the

experiments of Georgieff and Jeannerod (1998) the information on acts may

have a double coding system in mind because the movement consciousness is

independent from the information on movement control.

Motor skill and metacognition. The experimental investigation of knowl

edge on knowledge allowed a further insight into the character of conscious

ness. Koriat (2000) stated that metacognitive processes were integrated parts of

the work controlled by mind. He made difference between two metacognitive

components: the observations and control. The subjective observation of

knowledge, the knowledge on knowledge seems to be a determinant part of con

sciousness, because it indicates not only our knowledge but also our being

aware of this knowledge. Control is connected firmly to the idea of conscious

ness. Posner and Snyder (1975) contrasted the controlled processes with the

automated ones in a conceptional structure as a sign of conscious action. Flavell

(1981) placed the motor metacognitive experience in an affective dimension

which returns a conscious inner feedback on the execution and effectiveness of

an action therefore influencing its result positively or negatively.

Motor learning and cognition

In connection with the acquisition of motor skill Fitts (1964) established three

determinant phases. The first is the cognitive phase, during which the subject

2 Knoweldge representation was defined by Miller, Galanter and Pribam ( 1960) as plans, by Schank and

Abelson (1977) as descriptions, by Norman et al. ( 1975) as definitions, by Rumelhart and Ortony ( 1977) as

sch?mas, by Rosche (1975) as prototypes.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

396 J?nos F?gedi

learns the basic skills and verbal aid is often used. The second is the associa

tive phase, which represents a transition between the verbally conscious phase

into the more automated one. Here the components supporting the successful

performance are stored and the ones with failure are rejected. In the third, the

autonomie or automated phase, consciousness plays a very minor role, the

movement is performed fast and attention can be directed to other tasks during

performance. Adams (1971) also pointed out the importance of the cognitive

processes in the early practice of motor skills. He evaluated his results that the

motor performance becomes automated after a fixation achieved by multiply

practice, therefore cognitive factors need little attention. Adams (1971) called

the beginning phase of movement performance verbal-motor phase, and the

fixated section motor phase.

Following Fitts' and Adams' theories a number of motor researchers came

to the conclusion that the introductory part of motor skill acquisition contains

cognitive structures such as cognitive maps, plans, models, patterns. The learn

ing of new motor patterns include the building on the old structures. The ele

ments of a task can be understood and organized on the base of the cognitive

declaration (Kleinman 1983), and selecting the proper motor program and its

parameters. As a summary of the above theories Carroll and Bandura (1987)

stated that the motor information can be gained by the selective perception of

critical characteristics, and by the symbolic coding and cognitive attempts to be

transformed into cognitive representations of motor tasks. The movement is

controlled by cognitive representation. Beyond the attention and memory pro

cesses which defines the acquisition of cognitive representation, a conception

comparison governs the transformation of representation into acts. The repro

duction of a modeled action patter is helped by the observation simultaneous

with performance, but only then, when the adequate representation of action

patter has already been formed. After the exact cognitive representation a dem

onstrated movement sequence can be reproduced from memory just as exactly

as if it was presented simultaneous with the performed action.

Cognitive determinants of motor skill

Piaget (1974) stated that if movement is intended to be made conscious, a new

conceptual knowledge must be created about the executed movement. A form

of conceptualization can be the verbalization. The importance of verbaliza

tion as the cognitive determinant of discrete motor sequences a number of

other researchers stressed also, because the individual striving to understand

the movement can get to the independent formulation of idea on movement

(Cantor 1965; Goss 1955; McAllister 1953; Sage 1984). But the cognition of a

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 397

motor task can have a non-verbal aspect, and imagery is the candidate for it

(Paivio 1971; Piaget 1974; Engelkamp 1991).

Minas (1980) separated the continuous or interactive motor skills into two

main components: the first is the sequence of the movements, the second is the

nature ofthat. The mental practice - the imagery of large muscle movements

without actual performance (Minas 1978) - can influence both mentioned as

pects of the skill.3 On the measured bases of the effect of mental practice

Minas (1980) declared that the mental practitioners could achieve a better re

sult in the acquisition of motor tasks compared to a control group, because

only they had the possibility to structure and organize their action plan prior

performance.

Minas (1980) believes that the success of mental practice validated by ex

periments supports the notion that the movement information is represented in

high level cognitive units. These units can be manipulated by clear psycholog

ical processes, and not necessarily include the simultaneous performance of

motor task. Beyond this fact the mental practice supported the formulation of

new motor schema with the selection and planning of old movement experi

ence as well as this support was manifested in the quality of the movement too.

Dance education and movement consciousness

The overall applied method of dance education is the imitation - as Beck

(1988) put it the "movement-mimicri" - a generally accepted way of teaching

dance based on the authority of history. The traditionally imitative way of

dance education was criticized by Locke (1970). Since during education the

teacher requires imitation and on correcting the mistakes s/he does not give the

possibility to the student to follow the origination of correction, the student be

comes dependent from the teacher's movement patterns. The process can be

called rather taming - says Locke - and it could be called education only if the

student gets a creative insight into the structure of the movement.

Many authors stress the importance of movement observation and analysis

in the territory of movement education. Sweeney (1970) thinks that if the stu

dent can conceptualize and verbalize the movement, s/he also understands it.

By the means of understanding the acquisition of the movement needs less re

hearsal and the movement stays in memory for a longer time. Therefore Swee

ney regards the understanding and the ability of analysis among advantages of

the mental rehearsals. Hannah (1999) believes that the knowledge on how the

parts of the body can move in the threefold unity of space-time-force and how

3 Sackett (1934) argues that mental practice is primarily for determining the symbolic or cognitive as

pect of a movement task.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

398 J?nos F?gedi

the meaning is embodied through style or content can shape the learning and

understanding of different dances.

The advantage of conceptualization was pointed out by Foley (1991) in

comparing the performance of simple and complex movement tasks by danc

ers and non dancers. The dancers were able to code the unknown movement

sequences not only in movement but also verbally, therefore they achieved

significantly better results in the memory tests compared to non dancers, who

could call up the dance only in movement.

Certain representatives of dance education have already paid attention to

the great advantages of movement consciousness dance teaching. Dimond

stein (1971) regards an important part of the school dance education programs

the development of kinesthetic consciousness. Acquiring the kinesthetic con

sciousness the learner can achieve a consciousness beyond the pure perform

ance of the movement, that how and why the movement is formulated. The

connection between body and possibility of expression can be understood

only this way. A goal of Tillotson (1967) was to increase the students' move

ment consciousness and understanding, so she included in the main areas of

her education program the development of consciousness on spatial and

bodily movement possibility.

Moomaw (1967) believed that the dance notation education greatly in

creases the children's ability of understanding and analyzing movement. In

her view dance notation improves the teaching and peforming ability, the

structure and parts of a notated choreography can be analyzed, and the flow,

dynamics of the individual movement units can be studied. Beck et al. ( 1987a,

1987b) made dance notation playing a central role in their textbook on dance

for young ballet students in favour of replacing the already mentioned move

ment-mimicri with integrated body-mind approach. Moses (1990) and War

burton (2000) examined in experimental conditions the validity of their hy

pothesis, whether students learn a notation system, they get better results in

recognizing and performing movement. According their results the applica

tion of dance notation really helps the child's movement cognitive-symbolic

development and the understanding dance.

Dance notation

Dance notation is the literature of dance, a symbol system for notating dance,

just as in music the musical score. During the history of dance in Europe the

notation of dance4 appeared first in the 15th century, and in this age it belonged

4 The earliest forms of dance notation in the European tradition date back to the late Middle Ages, the

Renaissance. The development and announcement of different dance notation systems last until these days.

(Hutchinson 1984; F?gedi 1993).

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 399

to the court culture of higher classes. From the point of dance literature two

outstanding period must be mentioned: the 18th and the 20th century. The 18th

century Feuillet-Beauchamp system5 (Feuillet 1700) was in use for about 150

years. In the 20th century the symbolic notation system of the Hungarian ori

gin Rudolf Laban6 spread all over the world under the name of Labanotation or

Kinetography Laban.7 Beck (1988) states that Labanotation now influences

the dancer's training, the dance history research, dance criticism, dance analy

sis, the creative process of choreography making and dance education. Further

on under the title "dance notation" Labanotation is understood.8

The kinetographic notation of dance is not only a set of graphic symbols

corresponding to movement phenomena, but a system of movement analytical

theories and rules taking into account the syntax and meaning of dance.9 Fol

lowing Hutchinson (1977,1983) it could be regarded the written language of

dance.

A verbalization-like tool of movement, but for its perspicuity and inte

grated movement information character Laban (1956) takes the system far

more effective than verbal description. While investigating the theories of ar

tistic symbolism Goodman (1976) thinks Labanotation an impressive scheme

of analysis and description which refutes the common belief that continuous

complex motion is too recalcitrant a subject matter for notational articulation.

In the view of Briston (1991) dance notation lifts the art of dance out of the

illiterate age; beyond preserving dance it makes possible studying in depth,

helps emerging the real dance history and dance tradition, because all these

cannot exist today without notation archives containing large amount of

notated material.10

5 For the education of this system only indirect data could be found but the system was a part of the cul

ture in the royal courts (Hutchinson 1984). It is a question why its use was abandoned. Some researchers

reason that the system could not follow the development of dance technique, others believe that dance cul

ture got into the hands of tradesman where literature and reading stood out of interest (Horwitz 1988).

6 Rudolf Laban was a determinant personality of the 20th century modern dance (Laban 1975; Maletic

1987;HodgsonandPreston-Dunlop 1990).

7 Hutchinson 1977; Knust 1979; Szentp?l (no year/a).

8 Dance notation describes the spatial three dimensionality, the time and dynamic values of dance. All

these factors must be determined for the whole body and for all the independently moveable body parts. An

important part of the system is also the indication of relations to objects, partners, groups, and other imagi

native shapes such as die circular paths, etc. With a musical comparison the notation of one person's move

ment resembles rather a score of an orchestra than a single instrument.

9 On the development and application of the system a large number of study have been published. For a

full list of sources see Warner(1984,1988,1995).

10 The most significant dance archives are: the Conservatoire de Paris; the Dance Notation Bureau in

New York; the Institute for Musicology of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in Budapest, Hungary; the

Language of Dance Centre in London; the National Resource Centre for Dance in Guilford, UK; the Ohio

State University in Columbus, USA; the Folkwang Hochschule in Essen, Germany.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

400 J?nos F?gedi

The hypothesis of research

From the point of the present investigation the cognitive psychology showed

important results. The theories proved that in spite of the fact that the move

ment becomes automated while learnt, its performance is controlled by cogni

tive sch?mas. The observation and conscious control of movement is the do

main of metacognition. Our knowledge on movement is procedural; to make

this knowledge conscious the knowledge must be transformed into the cate

gory of declaration. It is believed here that in case of dance the procedural

knowledge can be effectively transformed into a declarative one by the means

of dance notation. Since dance notation is a symbolic and an analytic system, it

naturally provides the high level cognitive units of movement information, the

classes of conceptualization beyond even verbalization, and it also demands

the use of movement imagery and mental practice of movement. The knowl

edge on movement becomes conscious in structured categories, therefore the

reconstructor acts in the higher sphere of movement metacognition.

Our research hypothesis is, that on reconstructing dance from notation the

result is more authentic than imitative reconstruction because the reconstructor

- gets independent from the space and time difficulties during the identifica

tion of the movement sample

- is disengaged from the effects of movement stereotypes, the danger of

changing the pattern to imitate with expected cognitive patterns already learnt

- recognizes the coherent units of movement and gets free from the influence

possibly differently structured music accompanying dance

- recognizes and gets deeper in understanding the structure of movement se

quences and gets deeper in understanding.

The description of the experiment-comparing dance reconstruction

from Labanotation and from video

In the experiment the interpretive performance of an 18 member Notation

Group (NG) from Labanotation and an imitative performance of the same

dance material from video by an 18 member Video Group (VG) was com

pared. The task for both groups was to reconstruct 11 authentic movement se

quence11 - motives or motive sequence - and in the case of a motive sequence

to state its structure.12 The Notation Group got the movement sequences in no

tation and could not see the original performance. The Video Group could

11 The movement sequences were selected from the Folk Dance Archive of the Institute for Musicology

of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

12 On the structure of folk dance and the idea of dance motive see: Martin - Pesov?r 1960; Szentp?l 1961 ;

Martin 1964.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 401

watch the same on video but were not helped by any cognitive means, there

fore they could learn the dances purely by imitating them. The original, 1-8

measures long movement sequences were performed by male dancers.

Both groups consisted of 18 persons, between age of 20 and 40, six profes

sionals and twelve amateur dancers.13 NG members were trained in Labano

tation for two or three years (at corresponding courses), and all graduated at

the Hungarian Dance Academy as dance teachers. VG members were selected

not being educated in the analytical approach of Labanotation, or at very low

level, not being able to use it in the case of the introduced tasks requiring high

level analytical capabilities. The movement sequences (MS) were deemed to

reflect the most important and generally known movement features of Central

European folk dances.14 From the point of the threefold space-time-force

unity of movement, the reconstruction were judged by the following general

movement genres.15

Space direction, level, movement category, distribution of weight and partial

weight, contact, rotation

Time rhythm, relation to the main beat of the music

The MS were ordered in an increasing difficulty of technique, rhythm,

structure and tempo from Nos. 1-11, the task defining the structure was identi

fied as No. 12. There was no time limit for reconstruction, members of both

groups could spend as much time as they needed to achieve a result satisfying

for themselves. All solutions were recorded on video on the bases of which the

evaluation was carried out. All movement sequences were evaluated accord

ing to different sets of criteria suiting their movement characters the best ways

and selected from the points given above. The right solution was given a value

1, a wrong solution value 0. Samples for the movement criteria and for the

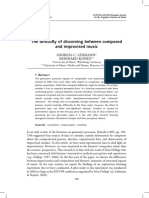

evaluations can be seen in Figures 1-4.

The results of reconstruction

Investigating the space-time appropriateness of reconstruction it could be

stated that the Notation Group achieved a significantly better result compared

to that of Video Group. A summarized general movement appropriateness

13 All participants started dancing before age 10, therefore even the amateurs could be regarded qualified

performers. This education is believed important from the point required movement understanding.

14 Szentp?l (no year/b); F?gedi 1997.

15 From the point of the threefold space-time-force unity of movement the force category has not been

thoroughly investigated in folk dance yet. During the experiment only one genre, the "bouncing spring" was

taken into consideration as a criteria - see Szentp?l no year/b.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

402 J?nos F?gedi

Notati on G o up Video Group

3.1 3 3.4 3.5 3.1 3.2 I 3.3 3.5 3.5

21. H

22. A

/ 23. A

24.

H/

lW

25.

s *v

26.

___Z'

V

4

28.

fi 29.

V 30.

31.

0 32.

,1 33.

__

34.

35.

? 36.

3.1 Measure 2: performing the triplet

3.2 Measure 3, beat 2: touching gesture

3.3 Measure 4, beat 1: direction and rotation of leg gesture

3.4 Measure 4, beat 2 : direction and rotation of leg gesture

Figure 1: Movement sequence 3

showed a 90.45 % result in the case of NG while VG achieved 35.81 % good

solutions.

Applying dance notation showed an even more outstanding advantage in

case of certain tasks. Such tasks were as 3, 10 and 11. Task No. 3 illustrated in

Figure 1 deviates from a Stereotypie performance in its amorphous structure

and the appearance of a triplet in the second measure. The right reconstruction

solution could be witnessed in NG = 96% versus VG = 22% proportion. In the

case of taskNo. 10 (Figure 2) the shift of the movement sequence unit compared

to the musical main beat (as a result of the uneven, 5/8 inner structure of the

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 403

Qfo

Notation Group Video Group

10.1 10.2 10.3 10.1 10.2 10.3

19.

20.

3. 21.

22.

23.

6. 24.

25.

8. 26.

27.

10. 28.

Jl 11. 29.

12. 30.

13. 31.

14. 32.

15. 33.

13

I

16. 34.

17. 35.

{ ?

18. 36.

10.1 Recognizing the uneven, 5/8 motive structure

10.2 Performing the shift in relation to the music

Figure 2: Movement sequence 10

motive) caused difficulty. Reconstruction resulted NG=100% versus

VG = 36%, wherethe 100%solutionbytheNGisreallyremarkable.Inthecase

of the most difficult task of the experiment, task 11, the very high tempo (J = cca.

200) caused a special reconstruction difficulty for the VG both in spatial and

temporal perception, while the NG had no difficulties in this respect, since the

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

404 J?nos F?gedi

*' i ' 11.1 Recognizing the rhythm

11.2 ; The accuracy of movement 1

i i, 11.7 The accuracy of movement 6

11.8 Performance in the original tempo

Notati Ion Group Video Group

19. 0 0

20. 0 ! 0 1 0

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32. 1

33.

34.

35. 1I1

36.

Figure 3: Movement sequence 11

static notation provided a comfortable understanding. Th

motive in the original tempo was a problem especially fo

dancers. Aside from the difficulties caused by the high temp

comparison of the two groups showed NG = 99% versus

Taking the temporal aspect into account as well, the resu

general, NG = 92 % versus VG = 33% could be noted.16

16 Even the temporal aspect would be much better in the case of NG if enough

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 405

%n:_-v

PKTZZ}

i__E_t

__E_t__

Notation Group Video Group

12.1 12.1 12.2

1. 19.

H 20.

21.

lu ^1 j4

22.

23.

24.

7. 25.

B*. 8. 26.

f

>

9. 27.

10. 28.

* u

11. 29.

12. 30.

N 13.

14.

31.

32.

15. 33.

16. 34.

17. 35.

_Q_ 18.

12.1 Structure stated by two measures (based on music)

12.2 i Structure stated by one measure (based on notation)

Figure 4: Movement sequence 12

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

406 J?nos F?gedi

Significant differences could be experienced also in the case of task No. 12,

where the structure of a short, 8 measure long movement sequence had to be

defined - see Fig. 4. The NG could go deeper to one measure level in establish

ing the structure in a pure cognitive way. Many from the VG could analyze the

sequence only after learning it. All of them identified two measure units,

which corresponded primarily with the phrases of the accompanying music.

Discussion and conclusion

The results of the experiment represent a very sharp distinction between the

performance of the two groups. The approximately three times better recon

struction of NG confirms very convincingly the validity of cognitive struc

tures in research and education of movement. They point out also that the

movement cognition can be developed and an outstanding tool for this devel

opment is the dance notation. Therefore the experiment proved the hypothesis.

The reason for the significantly better result of the NG was, that dance no

tation, discovering the structure, the spatial and temporal relations of the

movement material, provided the information on movement structures and

conceptions represented in cognitive units, this way the reconstructor became

independent from the difficulties of identifying the movement patter in space

and time. Members of the NG escaped the burden of memorizing and creating

cognitive patters of the required movement sequences, only transforming the

already memory-stored, and notationally evoked movement primitives into

real movements (remember the double coding system described by Georgieff

and Jeannerod 1998). Dance notation represented an especially great advan

tage in case of high tempo.

From the point movement research the result, that NG solved all the tasks

significantly better, which required the recognition of structure, seems essen

tial. The NG was also able to discover deeper structural correspondence in the

case of the non-reconstructural task than the VG, whose members identified

the structural unit by the music and not by the inner sequences of the dance it

self.17

As a summary it can be stated that dance notation was proved to be an es

tablished tool for dance research and dance education in understanding and

analyzing movement. This theorem is especially valid in cases where

-the structure of dance is amorphous

- the units of movement sequences differ from that of the accompanying music

- the tempo of the dance is high.

17 This phenomenon needs further investigation, and may indicate that the musical ordonnance in mind

is stronger than that of the visual impressions.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 407

Dance notation is used rather isolated in the field of traditional dance in

Hungary, mainly in dance research. In the light of the research introduced

above it is highly recommended to introduce dance notation in research, edu

cation, aesthetics and criticism in the other genres of dance (such as ballet,

modern and social dance).

References

ADAMS, J. A. (1971): A closed-loop theory of motor learning. Journal of Motor Behavior,

3,111-149.

ADAMS, J. A. ( 1981 ): Do Cognitive Factors in Motor Performance Become Nonfunctional

with Practice?JournalojMotor Behavior, 13,262-273.

ANDERSON, J. R. (1980): Cognitive Psychology and its Implications. New York: W. H.

Freeman

ANNETT, John (1996): On knowing how to do things: a theory of motor imagery. Cognitive

Brain Research, 3,65-69.

BANDURA, A. (1969): Principles of Behavior Modification. New York: Holt, Rinehart &

Winston.

BECK, Jill with LYNN, Enid & FLEMING, Diane ( 1987a) : My First Ballet Workbook. Parts I

II. Hartford: School of the Hartford Ballet.

BECK, Jill with LYNN, Enid & FLEMING, Diane (1987b): My Second Ballet Workbook.

Parts I?II. Hartford: School of the Hartford Ballet.

BECK, Jill (1988): Labanotation: Implication for the Future of Dance. Choreography and

DanceVol A,69-91.

BRISTON, Peter (1991): Dance as Education: Towards a National Dance Culture. New

York: The Falmer Press.

CANTOR, J. H. (1965): Transfer of stimulus pretraining to motor paired-associate and dis

crimination learning tasks. In: L. P. Lipsitt & C. C. Spiker (Eds.) Advances in Child De

velopmentandBehavior(Vol. 2). New York: Academic Press.

CARROLL, W. A. & BANDURA, A. (1987): Translating Cognition Into Action: The Role of

Visual Guidance in Observational Learning. Journal of Motor Behavior, 19,385-398.

DIMONDSTEIN, G?raldine (1971): Children Dance in the Classroom. New York:

Macmillan Publishing Co. Inc.

ENGELKAMP, J. (1991): Memory of Action Events: Some Implications for Memory Theory

and for Imagery. In: C. Cordony & M. A. McDaniel (Eds.) Imagery and Cognition.

New York, Berlin: Springer Verlag.

FERRARI, Michel (1996): Observing the Observer: Self-Regulation in the Observational

Learning of Motor Skills. Developmental Review 16,203-240.

FEUILLET, R. A. (1700): Chor?graphie, ou l'art de d?crire la danse. Paris. Reprint. New

York: George Olms, 1979.

FlTTS, P. M. (1964): Perceptual motor skill learning. In: A. W. Melton (Ed.) Categories of

Human Learning. New York: Academic Press, 244-284.

FlTTS, P. M. & POSNER, M. I. (1967): Human Performance. Belmont: Brooks/Cole.

FLAVELL, J. H.( 1981): Cognitive monitoring. In: W. P. Dickson (Ed.) Children's Oral

Communication Skills. New York: Academic Press, 35-60.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

408 J?nos F?gedi

Fleishman, E. A. & HEMPEL, W. E., Jr. (1955): The relation between abilities and im

provement with practice in a visual discrimination reaction task. Journal of Experi

mentalPsychology 49,301-312.

FOLEY, A. M. (1991): The effects of enactive encoding, type of movement, and imagined

perspective on memory of dance. Psychological Research 53,251-259.

F?GEDI, J?nos (1997): An Analysis and Classification of Springs. Proceedings of the

Twentieth Biennial Conference of the International Council ofKinetography Laban,

August 9-14,1997, held at the Hong Kong Academy for Performing Arts, Hong Kong,

41-76.

F?GEDI, J?nos (1993): T?nclejegyzo rendszerek (Dance notation systems) MIL

T?ncm?v?szet XVIII, 1-2,48^9,3-4,49-51,5-6,47-49.

GARDNER, Howard (1983): Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiply Intelligence. New

York: Basic Books.

GEORGIEFF, Nicolas & JEANNEROD, Marc (1998): Beyond Consciousness of External Re

ality: A "Who" System for Consciousness of Action and Self-Consciousness. Con

sciousness and Cognition 1,465-477.

GOODMAN, Nelson ( 1976): Languages of Art. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company,

Inc.

GOSS, A. E. (1955): A stimulus-response analysis of the interaction of cue-producing and

instrumental responses. Psychological Review 62,20-31.

HANNAH, Judith Lynn (1999): Partnering Dance and Education; Intelligent Moves for

changing Times. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

HODGSON, John & PRESTON-DUNLOP, Valerie (1990): Rudolf Laban -An Introduction to

his Works & Influence. Plymouth: Northcote House.

HORWITZ, Dawn Lille (1988): Philosophical Issues Related to Notation and Reconstruc

tion. Choreography andDance Vol. 1,37-53.

HUTCHINSON, Ann (1977): Labanotation or Kinetography Laban - The system of Ana

lyzing and Recording Movement. Third Edition, Revised. New York: Theatre Art

Books.

HUTCHINSON, Ann (1983): Your Move: A New Approach to the Study of Movement and

Dance. New York: Gordon and Breach.

HUTCHINSON, Ann ( 1984) : Dance Notation : The process of recording movement on paper.

London: Dance Books.

JAMES, W. (1890): The principles of psychology QJo\. 1). New York: Holt.

KIMBLE, G. E. & PERLMUTER, L. D. (1970): The problem of volition. Psychological Re

view11,361-384.

KLEINMAN, Matthew (1983): The Acquisition of Motor Skill. Brooklyn College of the City

University of New York: Princeton Book Company.

KNUST, A. (1979): A Dictionary ofKinetography Laban ML Plymouth: Macdonalds and

Evans.

KORIAT, Asher (2000): The Feeling of Knowing: Some Metatheoretical Implications for

Consciousness and Control. Consciousness and Cognition 9,149-171.

LABAN, Rudolf (1956): Laban 's Principles of Dance and Movement Notation. London:

Macdonald and Evans.

LABAN, Rudolf ( 1975): A Life for Dance. London: Macdonald and Evans.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Movement Cognition and Dance Notation 409

LOCKE, Lawrence (1970): A Critique of Movement Education. In: Robert T. Sweeney

(Ed.) Selected Readings in Movement Education. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley

Publishing Company, 187-202.

MALETlC,Verei(\9%7): Body-Space-Expression. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

MARTIN, Gy?rgy & PESOV?R, Ern? (1960): A magyar n?pt?nc szerkezeti elemz?se (Struc

tural analysis of the Hungarian folk dance). T?nctudom?nyi Tanulm?nyok 1959-1960,

211-248.

MCALLISTER, D. E. (1953): The effect of various kinds of relevant verbal pretraining on

subsequent motor performance. Journal of Experimental Psychology 45,329-336.

MCCABE, A. E. ( 1979) A paradox of self-regulation in speech-motor interaction: Semantic

degradation and impulse segmentation. In: G. Zivin (Ed.) The development of self reg

ulation through private speech. New York: Wiley.

MILLER, G. A. & GALANTER, E. & PRIBAM, K. H. (I960): Plans and the Structure of

Behavior, New York: Henry Holt.

MINAS, S. C. (1978): Mental practice of a complex perceptual motor skill. Journal of

Human Movement Studies 4,102-107.

MINAS, S. C. (1980): Acquisition of a motor skill following guided mental and physical

practice. Journal of Human Movement Studies 6,127-141.

MOOMAW, Virginia (1967): The Notated Creative Thesis. Research in Dance: Problems

and Possibilities. Proceeding of the Preliminary Conference on Research in Dance.

Greystone Conference Center, Riverdale, New York, 133-136.

MOSES, Nancy H. (1990): The Effects of Movement Notation on the Performance,

Cognitions and Attitudes of Beginning Ballet Students at the College Level. In:

Lynnette Y Overby & James H. Humphrey (Eds.) Dance - Current Selected Research.

Vol.2.New York: AMS Press, 105-112.

NEWELL, K. M. & BARCLAY, C. R. (1982): Developing Knowledge About Action. In: J. A.

S. Kelso & J. E. Clark (Eds.) The Development of Movement Control and Co-ordina

tion. NewYork: John Wiley and Sons, Ltd. 175-212.

NORMAN, D. A. & RUMELHART, D. E. & LNR Research Group (1975): Explorations in

Cognition. San Francisco: Freeman.

PAIVIO, A. ( 1971 ) : Imagery and verbal process. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

PIAGET, J. (1974): Laprise de conscience. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

POSNER, M. I. & SNYDER, C. R. R. (1975): Attention and cognitive control. In: R. Solso

(Ed.) Information processing and cognition: The Loyola symposium. Hillsdale, New

York: Erlbaum.

ROSCHE, E. (1975): Universals and cultural specifies in human categorization. In: R.

Brislin, S. Bochern and W. Lonner (Eds.) Cross-cultural Perspectives of Learning.

New York: Sage-Halsted.

RUMELHART, D. E. & ORTONY, A. (1977): The representation of knowledge in memory. In:

R. C. Amderson, R. J. Spiro and W. E. Motague (Eds.) Schooling and the Acquisition of

Knowledge. Hillsdale, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum.

SACKETT, R. S. (1934): The influences of symbolic rehearsal upon the retention of maze

habit. Journal of General Psychology 10,376-395.

SAGE, George H. (1984): Motor Learning and Control: A Neuropsychological Approach.

University of Northern Colorado, Dubuque, Iowa: Wm.C. Brown Publishers.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

410 J?nos F?gedi

SCHANK, R. C. & ABELSON, R. P. (1977): Scripts, Plans, Goals and Understanding. Hills

dale, New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.

SCHMIDT,R. A. {1915). Motor Skills. New York: Harper&Row.

Szentp?l, Olga (1961): A magyar n?pt?nc formai elemz?se (Formal analysis of the Hun

garian folk dance). Ethnogr?fia LXXII, 3-55.

Sz. SZENTP?L, M?ria (no year/b) : T?ncjel?r?s -L?b?n kinetogr?fia Mil (Dance notation -

Laban's kinetography). Budapest: N?pm?vel?si Propaganda Iroda.

Sz. SZENTP?L, M?ria (no year/b): A mozdulatelemz?s alapfogalmai (Basic concepts of

movement analysis). Budapest: N?pm?vel?si Propaganda Iroda.

SWEENEY, Robert T. (1970): Motor Learning: Implications for Movement Education. In:

Robert T. SWEENEY (Ed.) Selected Readings in Movement Education. Reading Mass.:

Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, 203-207.

TlLLOTSON, Joan (1967): A Program of Movement Education for Plattsburg Elementary

Schools. Research in Dance: Problems and Possibilities. Proceeding of the Prelimi

nary Conference on Research in Dance. Greystone Conference Center, Riverdale, New

York, 114-118.

WARBURTON, Edward C. (2000): The Dance on Paper: The Effect of Notation-use on

Learning and Development in Dance. Research in Dance Education, Vol. 1, No. 2,193

213.

WARNER, Mary Jane (1984,1988,1995): Labanotation Scores: An International Bibliog

raphy. An ICKL Publication. Chelsea, Michigan.

Studia Musicologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae 44/3-4, 2003

This content downloaded from

45.134.22.173 on Fri, 15 Jul 2022 13:41:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Benesh Movement Notation Was Devised by Rudolf and Joan Benesh and First Published in 1956Document1 pageBenesh Movement Notation Was Devised by Rudolf and Joan Benesh and First Published in 1956monique_cauchiNo ratings yet

- Introduction to LabanotationDocument15 pagesIntroduction to LabanotationEmanuel Castañeda100% (1)

- CHOREOGRAPHYDocument17 pagesCHOREOGRAPHYPramendra AryaNo ratings yet

- Choreography A Pattern LanguageDocument8 pagesChoreography A Pattern Languagefreiheit137174No ratings yet

- Jose LimonDocument8 pagesJose LimonKathleen ColesNo ratings yet

- Michael Klein, ChoreographyDocument233 pagesMichael Klein, ChoreographyKatarzyna Słoboda100% (2)

- 11 Kuwait Food MallsDocument34 pages11 Kuwait Food MallspoNo ratings yet

- Dance Composition BasicsDocument105 pagesDance Composition BasicsSharie Faith Binas100% (1)

- Ohad NaharinDocument15 pagesOhad NaharinmartinaNo ratings yet

- Martha GrahamDocument3 pagesMartha GrahamMark allenNo ratings yet

- Labanotation Movement LanguageDocument11 pagesLabanotation Movement Languageplavi zecNo ratings yet

- Motor Learning and The Dance Technique Class Science Tradition and PedagogyDocument10 pagesMotor Learning and The Dance Technique Class Science Tradition and PedagogyDoDongBulawinNo ratings yet

- Improvising Philosophy: Thoughts On Teaching and Ways of BeingDocument6 pagesImprovising Philosophy: Thoughts On Teaching and Ways of BeingMoyra SilvaNo ratings yet

- CV FarhanDocument2 pagesCV FarhanFarhan FurganiNo ratings yet

- Maya Plisetskaya's Groundbreaking Career as a Soviet BallerinaDocument10 pagesMaya Plisetskaya's Groundbreaking Career as a Soviet BallerinaAnonymous J5vpGuNo ratings yet

- Dance Expertise Embodied CognitionDocument21 pagesDance Expertise Embodied CognitionIrene Alcubilla TroughtonNo ratings yet

- The Role of Attention Perception and Mem PDFDocument13 pagesThe Role of Attention Perception and Mem PDFMarian ChiraziNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Use of Sonification in Higher Education in Physics Final DraftDocument21 pagesEvaluating The Use of Sonification in Higher Education in Physics Final DraftjxhnbarberNo ratings yet

- Acta Psychologica: A B C D e FDocument11 pagesActa Psychologica: A B C D e FSabanal CharlieNo ratings yet

- Neurocognitive DanceDocument12 pagesNeurocognitive DanceKristina KljucaricNo ratings yet

- Conocimiento Corporal Reflexiones Epistemológicas Sobre La DanzaDocument18 pagesConocimiento Corporal Reflexiones Epistemológicas Sobre La DanzaNuria AvantNo ratings yet

- Bartenieff - Hackney - Jones - Zile - Wolz - The Potential of Movement Analysis As A Research ToolDocument25 pagesBartenieff - Hackney - Jones - Zile - Wolz - The Potential of Movement Analysis As A Research ToolBia VasconcelosNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Expertise in Music Reading: Cross-Modal CompetenceDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Expertise in Music Reading: Cross-Modal CompetenceMaani TajaldiniNo ratings yet

- SMT - Unifying Music Cognitive Theory and Aural TrainingDocument13 pagesSMT - Unifying Music Cognitive Theory and Aural Traininggoni56509No ratings yet

- Pressing - Improv MethodsDocument50 pagesPressing - Improv Methodsmatejadolsak_7303486No ratings yet

- Philmusieducrevi 26 1 06Document18 pagesPhilmusieducrevi 26 1 06ireneNo ratings yet

- Pressing - Improvisation - Methods and ModelsDocument58 pagesPressing - Improvisation - Methods and ModelsDaniel De León González100% (1)

- The Effect of Aging On Memory For Recent and Remote Egocentric and Allocentric Information (Lopez Et Al., 2018)Document18 pagesThe Effect of Aging On Memory For Recent and Remote Egocentric and Allocentric Information (Lopez Et Al., 2018)FraParaNo ratings yet

- Music, Meaning and The Mind: EmbodiedDocument84 pagesMusic, Meaning and The Mind: EmbodiedЮрий СемёновNo ratings yet

- Styles EnglishDocument13 pagesStyles EnglishMarija JovanovicNo ratings yet

- A Motion Capture Library For The Study of Identity, Gender, and Emotion Perception From Biological MotionDocument8 pagesA Motion Capture Library For The Study of Identity, Gender, and Emotion Perception From Biological MotionStanko.Stuhec8307No ratings yet

- The Oxford Handbook of Music and The Body - The Body As Musical InstrumentDocument20 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of Music and The Body - The Body As Musical Instrumentgiordi79No ratings yet

- Skill Development in Music ReadingDocument52 pagesSkill Development in Music ReadingEverton Dias100% (1)

- Integrating Semi-Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique TrainingDocument18 pagesIntegrating Semi-Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique TrainingNehir CantasNo ratings yet

- Dance Accion and Social Cognition Brain and CognitionDocument6 pagesDance Accion and Social Cognition Brain and CognitionrorozainosNo ratings yet

- Integrating Semi Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique TrainingDocument19 pagesIntegrating Semi Structured Somatic Practices and Contemporary Dance Technique TrainingYonoh YorohNo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Episodic Memory To Efl Learners: PsycholinguisticDocument11 pagesThe Implementation of Episodic Memory To Efl Learners: PsycholinguisticAndy Hamzah FansuryNo ratings yet

- Orienteering: Spatial Navigation Strategies and Cognitive ProcessesDocument8 pagesOrienteering: Spatial Navigation Strategies and Cognitive ProcessesJuan Fran CoachNo ratings yet

- Jazz PatternsDocument46 pagesJazz Patternslaladodo64% (11)

- Music Performance As Knowledge Acquisition: A Review and Preliminary Conceptual FrameworkDocument17 pagesMusic Performance As Knowledge Acquisition: A Review and Preliminary Conceptual Frameworkelpidio59No ratings yet

- Embodied Mind Situated Cognition and ExpDocument29 pagesEmbodied Mind Situated Cognition and Expponyrider4No ratings yet

- Using Face Expression Detection, Provide Music RecommendationsDocument7 pagesUsing Face Expression Detection, Provide Music RecommendationsIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Adrienne Kaeppler Tongan DanceDocument46 pagesAdrienne Kaeppler Tongan DanceJNo ratings yet

- Motion Verbs Emotions PDFDocument0 pagesMotion Verbs Emotions PDFnancy_1100% (2)

- On Cultural SchemataDocument21 pagesOn Cultural SchematapangphylisNo ratings yet

- Psych PaperDocument7 pagesPsych PaperMalyk HassaiouneNo ratings yet

- Embodied CognitionDocument13 pagesEmbodied Cognitionbphq123No ratings yet

- Presentation PsychologyDocument10 pagesPresentation Psychologyapi-624478936No ratings yet

- Learning Styles: Implications For Distance Learning: Cite This PaperDocument14 pagesLearning Styles: Implications For Distance Learning: Cite This PaperAndy Delos ReyesNo ratings yet

- BodyPercussioninthePhysicalEducation BAPNEDocument12 pagesBodyPercussioninthePhysicalEducation BAPNEholawuenastardesxdxdNo ratings yet

- Abdallah, Gold, Marsden - 2016 - Analysing Symbolic Music With Probabilistic GrammarsDocument33 pagesAbdallah, Gold, Marsden - 2016 - Analysing Symbolic Music With Probabilistic GrammarsGilmario BispoNo ratings yet

- Development of bodily-kinesthetic intelligence through creative danceDocument10 pagesDevelopment of bodily-kinesthetic intelligence through creative danceChí Huỳnh MinhNo ratings yet

- Neural Mechanisms SubservingDocument7 pagesNeural Mechanisms SubservingRandy HoweNo ratings yet

- tmpADE TMPDocument10 pagestmpADE TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- Body Movements For Affective ExpressionDocument19 pagesBody Movements For Affective ExpressionSinan SonluNo ratings yet

- Fpsyg 11 01480Document22 pagesFpsyg 11 01480María Isabel Gutiérrez BlascoNo ratings yet

- Perceptual DisordersDocument40 pagesPerceptual Disordersisos.mporei.vevaios.0% (1)

- Teorija, Terapija I Istrazivanje Senzorne IntegracijeDocument10 pagesTeorija, Terapija I Istrazivanje Senzorne IntegracijeJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- The Neuroscience of Musical ImprovisationDocument25 pagesThe Neuroscience of Musical ImprovisationJorge Mario Mendoza Gutierrez100% (1)

- Witt Lich 1977Document20 pagesWitt Lich 1977paperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Listening to Jazz: The Rhythm SectionDocument2 pagesListening to Jazz: The Rhythm SectionpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Pentatonic Improvisation (Evan Tate)Document93 pagesPentatonic Improvisation (Evan Tate)paperocamillo75% (4)

- On Repeat - How Music Plays The MindDocument4 pagesOn Repeat - How Music Plays The MindpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Turning The Analysis Around Africa-DerivDocument21 pagesTurning The Analysis Around Africa-DerivpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Beginning Speak,: ReadDocument7 pagesBeginning Speak,: ReadpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- R P A C: AC S T S: Rhythmic Prototypes Across CulturesDocument23 pagesR P A C: AC S T S: Rhythmic Prototypes Across CulturespaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- The Takadimi System Reconsidered: Its Psychological Foundations and Some Proposals For ImprovementDocument15 pagesThe Takadimi System Reconsidered: Its Psychological Foundations and Some Proposals For ImprovementpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- R P A C: AC S T S: Rhythmic Prototypes Across CulturesDocument23 pagesR P A C: AC S T S: Rhythmic Prototypes Across CulturespaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Universality Versus Cultural SpecificityDocument49 pagesUniversality Versus Cultural SpecificitypaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- 03 Brown JMTP Vol-34Document37 pages03 Brown JMTP Vol-34paperocamilloNo ratings yet

- 01 App 02 RhythmicCountingSyllablesDocument2 pages01 App 02 RhythmicCountingSyllablespaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- A Study of The Kodaly Approach To Music Teaching PDFDocument190 pagesA Study of The Kodaly Approach To Music Teaching PDFricardo_jaraujoNo ratings yet

- (Oxford Studies in Music Theory) Grant, Roger Mathew - Beating Time & Measuring Music in The Early Modern Era-Oxford University Press (2014)Document329 pages(Oxford Studies in Music Theory) Grant, Roger Mathew - Beating Time & Measuring Music in The Early Modern Era-Oxford University Press (2014)paperocamillo100% (1)

- Wiggins2007 PDFDocument9 pagesWiggins2007 PDFpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Sound Playback Studies: AND MortonDocument2 pagesSound Playback Studies: AND MortonpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Microtonal Music and Its Relationship To PDFDocument69 pagesMicrotonal Music and Its Relationship To PDFSzymon BywalecNo ratings yet

- Rhythmical Crossover Between Tabla Phras PDFDocument91 pagesRhythmical Crossover Between Tabla Phras PDFpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Music Is Not A Language Re-Interpreting PDFDocument24 pagesMusic Is Not A Language Re-Interpreting PDFEurico RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Lehmann PDFDocument8 pagesLehmann PDFcyrcosNo ratings yet

- Improvisation: Towards A Maturing Understanding of Its Importance To The 21st Century MusicianDocument72 pagesImprovisation: Towards A Maturing Understanding of Its Importance To The 21st Century Musicianpaperocamillo100% (2)

- The Difficulty of Discerning Between Composed and Improvised MusicDocument17 pagesThe Difficulty of Discerning Between Composed and Improvised MusicpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- The Rhythmic Structure of Music - ReviewDocument7 pagesThe Rhythmic Structure of Music - Reviewpaperocamillo100% (1)

- But If Its Not Music What Is It DefiningDocument18 pagesBut If Its Not Music What Is It DefiningpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- The Phrygian Inflection and The Appearances of Death in MusicDocument36 pagesThe Phrygian Inflection and The Appearances of Death in Musicpaperocamillo100% (1)

- Music Perception and Cognition - A Review of Recent Cross-Cultural ResearchDocument15 pagesMusic Perception and Cognition - A Review of Recent Cross-Cultural ResearchpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Mue 2040 PDFDocument5 pagesMue 2040 PDFpaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Tut 359 EthesisDocument126 pagesTut 359 EthesispaperocamilloNo ratings yet

- Excerpts From - . .: Developing Musicianship Through ImprovisationDocument24 pagesExcerpts From - . .: Developing Musicianship Through Improvisationpaperocamillo0% (1)

- Modern Dance Exam Guide to Forerunners, Pioneers & Second GenerationDocument7 pagesModern Dance Exam Guide to Forerunners, Pioneers & Second Generationkimber brownNo ratings yet

- Development of 'Stick Figure' Notation For African DancesDocument19 pagesDevelopment of 'Stick Figure' Notation For African DancesAssociation of Dance Scholars and Practitioners of NigeriaNo ratings yet

- The Perpetual Present of Dance Notation PDFDocument20 pagesThe Perpetual Present of Dance Notation PDFjosefinazuainNo ratings yet

- Choreographing History: Susan Leigh FosterDocument19 pagesChoreographing History: Susan Leigh Fosteriamjohnsmith82No ratings yet

- Beyond Writing, Elizabeth Hill BooneDocument20 pagesBeyond Writing, Elizabeth Hill BooneRicardo UribeNo ratings yet

- Improvisational Choreography As A Design PDFDocument25 pagesImprovisational Choreography As A Design PDFFabio JotaNo ratings yet

- Choreographic ObjectsDocument271 pagesChoreographic ObjectsManea RaduNo ratings yet

- Effort - Rudolf Von LabanDocument112 pagesEffort - Rudolf Von LabanGeorgy Plekhanov100% (1)

- Aesthetics of Bugaku DanceDocument22 pagesAesthetics of Bugaku DancehelenamxNo ratings yet

- Labanotator No 01Document10 pagesLabanotator No 01Raymundo RuizNo ratings yet

- Alwin Nikolais' Choroscript Notation SystemDocument12 pagesAlwin Nikolais' Choroscript Notation SystemManuel CoitoNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Von LabanDocument2 pagesRudolf Von LabanRejill May LlanosNo ratings yet

- Dynamics FINAL4 PDFDocument162 pagesDynamics FINAL4 PDFGmmmm123100% (1)

- Dance Notation, DomeniccoDocument119 pagesDance Notation, DomeniccoBarbara MalavogliaNo ratings yet

- Philosophical and Histo-Cultural Perspectives of Local Folk DancesDocument14 pagesPhilosophical and Histo-Cultural Perspectives of Local Folk DancesPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- In The Company of Visionaries. Dalcroze, Laban and Perrottet - Paul MurphyDocument5 pagesIn The Company of Visionaries. Dalcroze, Laban and Perrottet - Paul MurphyAlexandre FunciaNo ratings yet

- Choreographing HistoryDocument19 pagesChoreographing Historyiamjohnsmith82No ratings yet

- Labanotator No - 62Document8 pagesLabanotator No - 62Raymundo RuizNo ratings yet

- Organizational Principles in Dance ChoreographyDocument23 pagesOrganizational Principles in Dance ChoreographyJay R BayaniNo ratings yet

- A Representation of Semantics of Human Movement Based On Labanotation (PDFDrive)Document95 pagesA Representation of Semantics of Human Movement Based On Labanotation (PDFDrive)Aryon KnightNo ratings yet

- The Development of A Gestural Vocabulary For Choal Conductors Based On The Movement Theory of Rudolf LabanDocument97 pagesThe Development of A Gestural Vocabulary For Choal Conductors Based On The Movement Theory of Rudolf LabanMonica SaenzNo ratings yet

- The MIT Press: The MIT Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To TDR (1988-)Document16 pagesThe MIT Press: The MIT Press Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To TDR (1988-)LazarovoNo ratings yet

- Labanotation Movement LanguageDocument11 pagesLabanotation Movement Languageplavi zecNo ratings yet

- Kaeppler - Dance in Anthropological PerspectiveDocument20 pagesKaeppler - Dance in Anthropological PerspectivePatricio FloresNo ratings yet

- Laban Movement AnalysisDocument8 pagesLaban Movement AnalysisUchiha Syukri50% (2)

- Brenda Farnell and The Laban Script in Anthropology Studies - Mei-Chen Lu - ACHEI PROCURANDO WOLPUTTEDocument4 pagesBrenda Farnell and The Laban Script in Anthropology Studies - Mei-Chen Lu - ACHEI PROCURANDO WOLPUTTELedsonNo ratings yet

- Laban Movement by Jillian CampanaDocument10 pagesLaban Movement by Jillian CampanaMihaela Socolovschi100% (1)

- 19-Article Text-51-1-10-20191231 PDFDocument25 pages19-Article Text-51-1-10-20191231 PDFBojan MarjanovicNo ratings yet

- Tracing The Discipline: Eighty Years of Ethnochoreology in SerbiaDocument29 pagesTracing The Discipline: Eighty Years of Ethnochoreology in SerbiaTijana DV StankovićNo ratings yet

- Özge Hamurcu Interior Design PortfolioDocument40 pagesÖzge Hamurcu Interior Design PortfolioÖZGE HAMURCUNo ratings yet