Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The New

Uploaded by

Muhammad AtifOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The New

Uploaded by

Muhammad AtifCopyright:

Available Formats

Introduction: Grassroots History: Global Environmental Histories from Below

Author(s): Robert Michael Morrissey and Roderick I. Wilson

Source: Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities , Vol. 3, Environmental

Humanities from Below (Winter/Spring/Fall 2015-2016), pp. 1-13

Published by: University of Nebraska Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5250/resilience.3.2016.0001

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5250/resilience.3.2016.0001?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Nebraska Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Introduction:

Grassroots History: Global Environmental

Histories from Below

Robert Michael Morrissey and

Roderick I. Wilson

On January 21, 2016, the front page of the website for the New York

Times featured an attention-grabbing headline. “The Hottest Year on

Record,” bold letters declared, “Globally, 2015 Was the Warmest Year

in Recorded History.”1 Beneath the Times’ straightforward headline ap-

peared a detailed discussion that touched on the various complexities

surrounding the discussion of climate change: how scientists arrive at

global averages, how broad trends have differential effects on local en-

vironments, the complex ways broad climate shifts manifest in extreme

heat waves and droughts at the regional scale. Climate scientists, along

with the journalists who translate their findings to a popular audience,

are accustomed to explaining and exploring the complex relationship

between local conditions and truly global environmental changes and

processes. They are used to scaling up from local phenomena to global

patterns. And they are increasingly effective at communicating a central

point, which is that to understand the changing relationship between

people and nonhuman nature, you need a global perspective. Some-

times the big scale is necessary.

For their part, historians have been making this point for decades.

In the past generation, a dedicated branch of historical scholarship has

brought together two approaches—environmental history and global,

or world, history—to a produce a new arena of inquiry. In a way, the

resulting conversation within the humanities does for the past what

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

climate scientists have been doing for world climate conditions in the

present: explaining and exploring the complex relationship between

local histories and global environmental changes and processes. To be

sure, climate change might be a dramatic example, and some now use

the term Anthropocene to argue that we are living in a totally new era.2

But it is not unprecedented that the human relationship with nature

transcends nation-state and regional boundaries. For environmental

historians, a global perspective has yielded new insights about events

and processes that a regional or local perspective obscures. Whether

examining commodification or capitalism, disease or scientific revolu-

tions, colonization or conservation, a generation of environmental his-

torians has recognized the possibilities and the fascination inherent in

scaling up to global histories. And although environmental historiog-

raphy mostly began with regional-scale stories about particular land-

scapes, predominantly in the North American West, this key insight

about the global scale of many environmental phenomena has trans-

formed the field in recent years.

The scale and mode of inquiry reflected in global environmental his-

tory clearly has its predecessors. For many decades, historical geogra-

phers in countries around the world have examined people’s activities

and relations in local environments.3 In the mid-twentieth century, his-

torians associated with the journal Annales: Economies, Sociétés, Civil-

isations, particularly under the stewardship of Fernand Braudel, also

found in the environment what Samuel Kinser has described as “geo-

historical structures” of historical change.4 In North America, where

the self-conscious effort to create the field of environmental history has

its oldest and deepest roots, a few of the earliest and most influential

environmental histories were global in scope and anticipated regular

calls for the field as a whole to become more international and glob-

al in its membership and coverage.5 Many historians apparently heed-

ed that call, with notable examples being the American Stephen Pyne’s

global history of fire and the Australian Richard Grove’s history of con-

servation in the British empire.6 Like Pyne and Grove, other historians

have scaled up to big history, searching for broad patterns on a truly

vast time scale or at the level of civilizations.7 Still others have offered

transnational histories of particular commodities or diseases.8 In recent

years, historians have written broad syntheses, provocative global histo-

ries of important eras, and offered histories of transnational and global

2 Resilience Vol. 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

movements.9 Now the field is even mature enough to feature its own in-

troductory reader, several synthetic essays, and essay collections.10

At the same time, given that many of the themes of global environ-

mental history often involve colonialism, capitalist expansion, and global

integration in the early modern and modern periods, this project can be

prejudiced when it comes to perspective. Specifically, given the nature

of the archives and still-entrenched dominant trajectories of global his-

tory, it is all too easy for historians to arrive at narratives that ignore or

overshadow local and indigenous peoples or local patterns in favor of the

assumed and often-unquestioned agents in history—the supposed mov-

ers, explorers, exploiters, and transformers.11 When historians scale up to

big history and explore themes such as the fate of empires, the quotidian

experience of regular people living in their environments is often left out.

Whether the action is colonization or conservation or commodification,

a pernicious inertia guides narratives toward the inclusion of certain ac-

tors like industrialists and government officials to the exclusion of others

like women and racial or religious minorities.

But this inertia is not irresistible, and other perspectives can enrich

our histories of global environmental history. The premise of the es-

says in this volume is that global environmental history can be told best

when good effort is made by historians to consider how this history

looked “from below,” from the standpoint of subaltern, marginalized,

and often-ignored actors. Taking inspiration from E. P. Thompson and

others, this volume aims at exploring history from the perspective of

regular people and even nonhuman actors, placing them at the center

of the story of global-scale environmental changes and phenomena.12

While the field is increasingly scaling up to offer new global environ-

mental histories, our hope is to infuse this shift with an important ex-

ploration of bottom-up perspectives.

Genesis of This Special Volume

This special volume grew out of a broader intellectual project aimed at

better incorporating these bottom-up perspectives into the writing of

global histories. Initiated by Antoinette Burton and the Center for His-

torical Interpretation at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

(uiuc) in 2011, these from-below histories first addressed theoretical

frameworks and urban histories before turning to the newer field of en-

Morrissey and Wilson: Introduction 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

vironmental history. Beginning in the fall of 2013, scholars at uiuc held

monthly meetings to discuss readings aimed at developing our under-

standing of what “the below” means in terms of global environmental

history. In the spring of 2014, these meetings culminated in the sym-

posium “Grassroots Histories: Global Environmental Histories from

Below” at uiuc. At the symposium, contributors from uiuc and else-

where presented original papers that offered distinctive approaches to

addressing this theme. This volume includes articles from many of that

symposium’s original participants, namely Tariq Ali, Andrew Bauer,

David Bello, Mark Frank, Zachery Poppel, and Roderick Wilson. Desir-

ing to extend the topical and institutional scope of this volume, we an-

nounced a call for papers that resulted in ten additional contributions

to this volume.

In each of the iterations that led to the publication of this special

volume, both the organizers and the contributors have grappled with

what it means to tell histories from below and, at the same time, what it

means to tell truly global histories. All along, scale has been a key prob-

lem. By scaling up, we lose specificity, and as Anna L. Tsing argues, we

risk excluding both cultural and biological diversity.13 By scaling down

to work mostly in local archives, we potentially lose the global perspec-

tive that can potentially shed light on obscured relations between often-

distant phenomena. In other words, we need to emphasize the dialogic

relationship between the global and the local as well as hold on to spe-

cific scales, for comparisons to make sense. Meanwhile, for historians

interested in this kind of inquiry, we also face a technical problem—

how to write about places outside our own expertise?

While these issues have surely been on the minds of the contributors

to this volume, the authors do not pretend to have solved these shared

dilemmas of global history and environmental history. Indeed, few of

them explicitly tackle the global as such. Instead, most write from a lo-

cal perspective about questions and phenomena that are global in their

scope. In that sense, the project here is comparative and cumulative—

viewing these essays together is one way by which we can arrive at the

global, even if few of the articles try to tackle a global perspective on

their own. At the same time, the authors approach the local with spe-

cific attention to often-marginalized historical actors, adding this im-

portant dimension of history from below. Taken together, these articles

show that global environmental history needs to take account of histor-

4 Resilience Vol. 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ical agency and the tensions at the grassroots level. To help organize the

individual themes of this special volume, we have divided the articles

into the below four sections.

Local Practices and Global Processes

The first group of essays explores the tensions between local commu-

nities and the forces that tried to integrate them into global processes,

whether economic, cultural, or governmental. These essays show the

important ways in which a from-below history can complicate top-

down narratives and force their revision.

David Bello explores the formation of fugitive environmental rela-

tionships that developed on so-called “sand flats” in the Lower Yangzi

River valley of Jiangsu Province during the late Qing Dynasty. While

state efforts at water control were intended to expand arable lands

and the imperial tax base, Bello shows that both people and insects—

particularly locusts—exploited for their own purposes the unintention-

al landscapes that resulted from silted riverbeds, undermining expert

efforts and complicating the power dimensions of environmental en-

gineering. His study not only calls into question the notion of water

control, which is too often taken for granted, but shows how such state

efforts floundered on their own contradictions and specifically because

they did not take into account the actors from below.

In Yan Gao’s article, “‘The Revolt of the Commons’: Resilience and

Conflicts in the Water Management of Jianghan Plain in Late Imperial

China,” water management is once again an issue. In this case, however,

it was not state efforts at water control, but rather an increasing popu-

lation and extensive land reclamation during the eighteenth and nine-

teenth centuries, that put a strain on local networks of resource man-

agement. As Gao shows, local knowledge and local networks were the

key to a resilient and stable system of land use in this flood-prone land-

scape, but the knowledge and networks were increasingly undermined

as the local population dependent on this riparian environment grew. It

was amid these challenges and the resulting conflict over diminishing

resources that a system of unified water management and stronger pri-

vate property rights emerged from below. Moreover, the violence sur-

rounding access to and control over water both foreshadowed and ex-

acerbated the revolutionary changes that led to the collapse of the Qing

empire in the early twentieth century.

Morrissey and Wilson: Introduction 5

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

If water attracted attempts to centralize and control environments, so

too did fire. In the next essay, Andrea Duffy explores how the tensions

of colonialism played out through competing uses of fire in French Al-

geria in the nineteenth century. For French colonial administrators in

Algeria, fire was dangerous, and its suppression was an important part

of rational land management—the way to save what they viewed as a

“ruined” landscape. For mobile pastoralists indigenous to the forests

and pasture of the country, fire was a useful tool. In the nineteenth cen-

tury, colonizers and the colonized clashed in their competing views of

fire. Duffy recovers a fire regime from the bottom up and uses it to tell

the story of indigenous resistance to colonialism.

Tariq Ali tells a similar story about centralizing state experts and a

resistant colonial hinterland. In his essay, he explores how a statist and

capitalist effort to transform the mofussil, or up-country, of the Ben-

gal delta into a productive hinterland of the postcolonial Pakistani state

met the realities of a resistant ecology on the ground. In this case, like

others, a centralizing and capitalistic state tried to maximize the pro-

duction and export of a marketable commodity—jute. But as in the

previous case studies, this was easier to imagine than to realize; in the

mofussil, state efforts ultimately ran against the unpredictable and un-

controllable shifting ecology of the delta. Thwarting the techniques of

governmentality, the delta thus emerged as a more complicated hinter-

land with its own logic, one that did not match the centralizing logic of

the emergent nation-state.

Like Ali, Mark Frank explores a local population and hinterland re-

sistant to central state administration in the short-lived Xikang Prov-

ince of the Republic of China. Building off James C. Scott’s idea that

pastoralists are refugees from the state, Frank nuances this idea by ar-

guing that pastoralism actually counteracted state efforts at fostering

agricultural practices. For Frank the assemblage of people, topography,

and nonhuman agents in the distinctive region created a history from

below that challenges simple narratives of modernization and progress.

Environmental Politics from Below

A second group of essays looks closely at not just environmental prac-

tices but also politics more generally; and in so doing, the articles un-

cover important stories of environmental activism around the world.

6 Resilience Vol. 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

As these papers show, the view from below—whether from marginal-

ized communities or from complicated hybrid spaces—forces us to tell

more-complicated stories about the history of environmental activism.

Diana J. Fox and Jillian M. Smith analyze an interesting social move-

ment in Trinidad, a fascinating example of ecological restoration from be-

low. Telling the story of Fondes Amandes, a village in the foothills north of

the country’s capital, Smith and Fox explain how a small Afro-Trinidadian

community managed to create and sustain a vibrant ecomovement under

the guidance of women leaders beginning in the 1970s. Locating the ori-

gins of this community in a combination of social movements—feminism,

black power, and Rastafarianism—Smith and Fox show how an alternative

community took root within a nation dominated by the legacies of a plan-

tation economy, patriarchy, and colonialism.

Rupert Medd explores an initiative sponsored by various stakehold-

ers in Peru’s Amazon region to promote and archive environmental

journalism online. Arguing that the writer-activists of the Premio Re-

portaje sobre Biodiversidad (prb), and particularly women journal-

ists, represented an important form of resistance to negative effects of

globalism and the legacy of colonialism, Medd brings to light a little-

known example of what Joan Martinez-Alier calls “the environmental-

ism of the poor.”14 Contextualizing this latter-day environmental jour-

nalism in a long tradition of travel writing and nature literature in the

region, Medd shows how the prb was an important turning point in

consciousness building and testimony from below.

If Medd explores self-conscious environmentalists emerging in the

Peruvian Amazon, Traci Brynne Voyles ponders the lack of environ-

mentalist activism at California’s Salton Sea. As Voyles points out, the

Salton Sea plays important roles as a stopover for bird migrations and

habitat for important aquatic species, and yet it attracts little atten-

tion from environmental activists. To explain this conundrum, Voyles

considers the origins of the sea, which she describes as being neither

natural nor human made. Clearly not an untouched wilderness that

still resonates at the roots of much of American environmentalism,

the Salton Sea ecosystem challenges environmentalists to rethink the

nature-verses-culture view of the environment, a feat of imagination

many have so far been unable to accomplish. For Voyles, considering

the relationship between humans and nonhumans from below requires

recognizing that the division between humans and nonhumans can of-

Morrissey and Wilson: Introduction 7

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ten not be sharply drawn in places like the Salton Sea and so many oth-

ers. In this way, Voyles’s environmental history from below challenges

the very categories through which we view human relationships with

local environments.

Methods and Models of Global

Environmental History from Below

Another group of essays adds to the conversation by proposing new

methodologies or approaches. First, Roderick Wilson critiques the

popular perception that people in preindustrial Edo (Tokyo) and Japan

had a particularly harmonious relationship with their environment by

examining the transformation of Edomae—a toponym used to describe

a local fishery that in the early modern period expanded to include fish

and shellfish caught throughout the region surrounding the massive

city of Edo. In exploring this history, he also questions the modernist

worldview on which these kinds of popular histories depend—namely,

that places like Edomae have an a priori objective existence that is later

ascribed with meaning by the people who encounter and interact with

them. In lieu of this commonplace perspective, he uses an alternative

ontology that he calls “environmental relations” to argue that places are

constantly being produced and reproduced through the activities of

assemblages constituted of both humans and nonhumans. In this way,

the below in Wilson’s account focuses on the activities of boat pilots,

merchants, fishers, fish, shellfish, and the tides and currents of the very

ocean itself.

Like Wilson, Gregory Rosenthal offers a self-conscious exploration

of how to pursue environmental history from below, but he takes on a

huge challenge when he contemplates a bottom-up method to environ-

mental history in the nineteenth-century Pacific Ocean. Recognizing

the fundamental ways in which the Pacific was a world in motion, he

argues that a focus on workers and indigenous peoples can counterbal-

ance historical narratives too often told over the shoulder of colonial-

ists, capitalists, and Western explorers. In contemplating and modeling

such a history from below, Rosenthal conducts three case studies and

defines a new environmental history defined by distinctive spaces—

ship holds, mines, plantations, and prisons. From these places, a new

perspective on environmental history is possible, one that weaves to-

8 Resilience Vol. 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

gether massive environmental change with tremendous human mobil-

ity, diverse encounters, and large-scale social dislocation and conflict.

Finally, we are proud to include an essay by the pioneering environ-

mental historian Cynthia Radding, who offers a methodological reflec-

tion focused on recovering perceptions of the natural world from below.

Author of several books including the topically and methodologically

influential Landscapes of Power and Identity: Comparative Histories in

the Sonoran Desert and the Forests of Amazonia from Colony to Repub-

lic, Radding shows in her essay how indigenous peasants in eighteenth-

century northern New Spain maintained their own perceptions of the

landscape rooted in subsistence strategies and the labor at the center

of those strategies.15 Reading an archive of legal proceedings and land

claims against the grain in order to recover indigenous meanings of the

land, Radding explores how indigenous actors shaped long-standing

subsistence patterns and defended them against Spanish claims and

competing uses of mining and agriculture. Radding not only recovers

an interesting story of colonial contestation but provides a model for

scholars looking to recover perceptions of the environment from below.

Recovering Agency from Below

A fourth group of essays is more explicitly focused on recovering the

complex agency of historical actors. While many environmental histo-

ries cast marginalized and subaltern peoples in simple roles as victims

or resistors, these histories from below reveal that a more nuanced sto-

ry is possible when we examine the story closely. For instance, as Colin

Fisher shows in his essay about the Back of the Yards neighborhood,

located around Chicago’s notorious industrial-food powerhouse, the

Union Stock Yards, workers were not just downtrodden victims of so-

cial and environmental inequalities. Surely, historians have not been

wrong to focus on the exploitation of human labor in the service of the

exploitation of nature on the famous “disassembly lines” of the Armour

factories and other landmark meatpackers. And yet, as Fisher argues,

the workers were not defined by this exploitation; a history from below

reveals the many ways in which stockyard families used urban parks

and wild green spaces in the city as an antidote to their marginalized

position. As Fisher concludes, the worst human victims of “the Jungle”

had another side to their lives.

Morrissey and Wilson: Introduction 9

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Rebecca Jones writes about local traditions with a similar sensibility

for reconstructing environmental relationships from below. In her arti-

cle “Possums, Quandongs and Kurrajongs: Wild Harvesting as a Strate-

gy for Farming through Drought in Australia,” she examines how Aus-

tralian settler farmers between 1890 and the 1940s used wild harvesting

as a way to cope with their drought-prone environment. While these

strategies have been eliminated and forgotten in today’s industrial ag-

riculture, they were an important means by which farm families raised

cash and calories in dire times. Recapturing these resilient strategies is a

fascinating example of environmental history from below.

Zachary Poppel explores another case study of resilience when he

writes about local residents who capitalized on a development project

in twentieth-century rural Sierra Leone. When the government of Sier-

ra Leone partnered with University of Illinois professors to build a new

research university after the model of the American land-grant univer-

sity, much of the project was conducted in a top-down manner, even

extending to the depopulation of an already-existing British colonial

college near Njala. At the same time, Poppel shows how local popu-

lations in the village of Njala participated and in many ways benefited

by the agricultural experiments of the development-focused institution.

In particular, Poppel demonstrates how local residents resisted some

of the agendas of the new university by cultivating ginger, an option-

making root that allowed local farmers to continue their own priorities

in the face of the powerful new institution in their midst.

The Anthropocene from Below

The final essay in the collection is a critical assessment of the much-

discussed concept of the Anthropocene from a philosophical and polit-

ical standpoint. In particular, Andrew Bauer’s essay highlights ways in

which the Anthropocene concept imagines our own time as distinctive

from a romanticized past age in which humans had no great effect on

nonhuman nature. Objecting to this view of human history for the way

it reifies the very binary that it seeks to dissolve, Bauer critiques the

concept of the Anthropocene in a way that reminds us of the important

continuities of history—the ways in which humans and other life forms

have always shaped their environments in profound ways. A powerful

argument against what he sees as a presentist concept, Bauer’s essay also

10 Resilience Vol. 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

provides a framework for appreciating the agency of humans across

time in ways that dovetail with the from-below project.

In a final contribution to this volume, Robert Rouphail provides a

review of a recent and popular introductory reader in the field of global

environmental history. Taken together, we hope these essays and this

volume will be a useful resource for the emerging field of global en-

vironmental history, even as they push the field forward toward more

complex narratives and richer perspectives.

About the Authors

Robert Michael Morrissey is an associate professor of history at the Universi-

ty of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He is the author of Empire by Collaboration:

Indians, Colonists, and Governments in Colonial Illinois Country (Philadel-

phia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015) and several articles about the

social and environmental history of the colonial Mississippi Valley and Great

Lakes regions. He is currently at work on a new environmental history of the

tallgrass prairie region of North America and its indigenous inhabitants from

1200 through the early 1800s.

Roderick Wilson earned a PhD in East Asian history from Stanford Uni-

versity in 2011 and is an assistant professor with a joint appointment in the

Department of History and the Department of East Asian Languages and Cul-

tures at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. He regularly teaches

a course on global environmental history as well as a variety of courses about

the history of Japan and East Asia. His research focuses on people’s interac-

tions with their local environments in early modern and modern Japan with a

particular focus on rivers, cities, and science and technology. Most recently, he

has published a review of two documentary films about the 2011 Fukushima

nuclear disaster and an essay on the artist Yoshida Hatsusaburo. Currently, he

is working on a book manuscript entitled “Turbulent Stream: Reengineering

Environmental Relations along the Rivers of Japan, 1750-1950” as well as a sec-

ond book-length project about the urban and environmental history of Tokyo.

Notes

1. Justin Gillis, “2015 Was Hottest Year in Historical Record, Scientists Say,” New York

Times, January 20, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/21/science/earth/2015-hottest-year

-global-warming.html.

2. Paul J. Crutzen and Eugene F. Stoemer, “The ‘Anthropocene,’” Global Change NewsLet-

ter 41 (2000): 17–18; Crutzen, “Geology of Mankind,” Nature 415, no. 6867 (January 3, 2002):

23, doi:10.1038/415023a; Dipesh Chakrabarty, “The Climate of History: Four Theses,” Critical

Inquiry 35 (2009): 197–222.

Morrissey and Wilson: Introduction 11

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

3. Michael Williams, “The Relations of Environmental History and Historical Geogra-

phy,” Journal of Historical Geography 20, no. 1 (1994): 3–21. See, for example, the following

massive volume: William L. Thomas Jr., ed., Man’s Role in Changing the Face of the Earth

(Chicago: University of Chicago, 1956).

4. Samuel Kinser, “Annaliste Paradigm? The Geohistorical Structuralism of Fernand

Braudel” American Historical Review 86, no. 1 (1981): 83. See also Lucien Febvre, A Geograph-

ical Introduction to History, with Lionel Bataillon, trans. E. G. Mountford and J. H. Paxton

(London: K. Paul Trench, Trubner, 1925); Fernand Braudel, The Mediterranean and the Med-

iterranean World in the Age of Philip II, 2nd rev. ed., trans. Siân Reynolds (Berkeley: Uni-

versity of California Press, 1995; originally published 1966); Fernand Braudel, Civilization

and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century, trans. Siân Reynolds, 3 vols. (New York: Harper and Row,

1982–1984).

5. See, for example, Alfred W. Crosby, The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural

Consequences of 1492, 30th Anniversary ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003;

originally published 1972); Donald Worster, “World without Borders: The Internationalizing

of Environmental History,” Environmental Review 6 (1982): 8–13, cited in Donald Hughes,

“Global Dimensions of Environmental History” Pacific Historical Review 70, no. 1 (2001): 91.

6. Stephen J. Pyne, World Fire: The Culture of Fire on Earth (1995; repr. Seattle: University

of Washington Press, 1997); Richard Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical

Island Edens, and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860 (New York: Cambridge Uni-

versity Press, 1995).

7. Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies (New York: Nor-

ton, 1998); William R. Dickinson, “Changing Times: The Holocene Legacy,” Environmental

History 5, no. 4 (2000): 483–502, doi:10.2307/3985583.

8. J. R. McNeill, Mosquito Empires (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010); John

Soluri, Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption, and Environmental Change in Honduras

and the United States, 1st ed. (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2005).

9. John R. McNeill, Something New under the Sun: An Environmental History of the

Twentieth-Century World (New York: Norton, 2000); John F. Richards, The Unending Fron-

tier: An Environmental History of the Early Modern World (Berkeley: University of Califor-

nia Press, 2003); Ramachandra Guha, Environmentalism: A Global History, Longman World

History Series (New York: Longman, 2000).

10. J. R. McNeill and Erin Stewart Mauldin, eds., A Companion to Global Environmental

History, 1st ed. (Hoboken, nj: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012); Edmund Burke and Kenneth Pomer-

anz, “Introduction: The Environment and World History,” in The Environment and World

History, ed. Edmund Burke and Pomeranz, Kenneth (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2009); John Robert McNeill and Alan Roe, Global Environmental History: An Intro-

ductory Reader, Rewriting Histories (New York: Routledge, 2013); Paul Sutter, “What Can US

Environmental Historians Learn from Non-US Environmental Historiography?,” Environ-

mental History 8, no. 1 (2003): 109–29.

11. On the problem of these all-too-often-colonial archives, see the following: Lisa Lowe,

The Intimacies of Four Continents (Durham, nc: Duke University Press, 2015); Ann Stoler,

Along the Archival Grain: Epistemic Anxieties and Colonial Common Sense (Princeton, nj:

Princeton University Press, 2009).

12 Resilience Vol. 3

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12. E. P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class (New York: Vintage Books,

1963); E. P. Thompson, Customs in Common: Studies in Traditional Popular Culture (New

York: New Press, 1991); Karl Jacoby, Crimes against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves, and

the Hidden History of American Conservation, 1st ed. (Berkeley: University of California

Press, 2003).

13. Anna L. Tsing, “On Nonscalability: The Living World Is Not Amenable to Precision-

Nested Scales,” Common Knowledge 18, no. 3 (2012): 507.

14. Joan Martinez-Alier, “The Environmentalism of the Poor: Its Origins and Spread,” in

A Companion to Global Environmental History, ed. J. R. McNeill and Erin S. Mauldin (Lon-

don: Blackwell, 2012), 513–29.

15. Cynthia Radding, Landscapes of Power and Identity: Comparative Histories in the So-

noran Desert and the Forests of Amazonia from Colony to Republic (Durham, nc: Duke Uni-

versity Press, 2006).

Morrissey and Wilson: Introduction 13

This content downloaded from

157.182.150.22 on Thu, 14 Mar 2019 14:56:52 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Worster, Doing Environmental HistoryDocument14 pagesWorster, Doing Environmental HistoryjoshBen100% (2)

- Madeleine Leininger Transcultural NursingDocument5 pagesMadeleine Leininger Transcultural Nursingteabagman100% (1)

- HULME 2010 - Problems With Making and Governing Global Kinds of KnowledgeDocument7 pagesHULME 2010 - Problems With Making and Governing Global Kinds of KnowledgefjtoroNo ratings yet

- Lynton Keith Caldwell, Paul Stanley Weiland - International Environmental Policy - From The Twentieth To The Twenty-First Century-Duke University Press (1996)Document494 pagesLynton Keith Caldwell, Paul Stanley Weiland - International Environmental Policy - From The Twentieth To The Twenty-First Century-Duke University Press (1996)Esnaur RaizarNo ratings yet

- IT ParksDocument12 pagesIT ParksDivam Goyal0% (1)

- Coursera International Business - Course 2 Week 2Document3 pagesCoursera International Business - Course 2 Week 2prathamgo100% (2)

- Case Study of Hyper Loop TrainDocument3 pagesCase Study of Hyper Loop TrainkshitijNo ratings yet

- Power Point Bahasa Inggris Sma Kelas XDocument21 pagesPower Point Bahasa Inggris Sma Kelas XMuammar Jumran91% (45)

- Jinh A 01410Document24 pagesJinh A 01410Balouch 36No ratings yet

- J R MCNEILL Environmental - History.Document39 pagesJ R MCNEILL Environmental - History.Sarah MishraNo ratings yet

- Environmental HistoryDocument34 pagesEnvironmental HistoryvionkatNo ratings yet

- Environmental HistoryDocument22 pagesEnvironmental Historydobojac73No ratings yet

- Tsing GlobalSituation 2000Document35 pagesTsing GlobalSituation 2000Camila VanacorNo ratings yet

- LEVI, Giovanni. Frail FrontiersDocument13 pagesLEVI, Giovanni. Frail FrontiersMiguel Angel OchoaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 8.9.5.148 On Sat, 25 Feb 2023 17:39:43 UTCDocument14 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 8.9.5.148 On Sat, 25 Feb 2023 17:39:43 UTCLuis Enrique Salcedo NietoNo ratings yet

- Doing Environmental History in Urgent TimesDocument23 pagesDoing Environmental History in Urgent TimesjoaoNo ratings yet

- Environmental History: Methodologies and Their Interactions: Tannistha BanerjeeDocument6 pagesEnvironmental History: Methodologies and Their Interactions: Tannistha BanerjeeTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- On The Largest Scale: Big History: The Struggle For Civil Rights (Teachers College Present (New Press)Document6 pagesOn The Largest Scale: Big History: The Struggle For Civil Rights (Teachers College Present (New Press)Elaine RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Environmental History and British ColonialismDocument19 pagesEnvironmental History and British ColonialismAnchit JassalNo ratings yet

- Society For History EducationDocument19 pagesSociety For History EducationBisht SauminNo ratings yet

- 8372-Article Text-39910-3-10-20230601Document2 pages8372-Article Text-39910-3-10-20230601João ManuelNo ratings yet

- 3 DimensionspdfDocument13 pages3 DimensionspdfFelipe Uribe MejiaNo ratings yet

- Social History and World HistoryDocument31 pagesSocial History and World HistoryU chI chengNo ratings yet

- Sara Miglietti Ed CLIMATES PAST AND PRESENTDocument11 pagesSara Miglietti Ed CLIMATES PAST AND PRESENTteresaNo ratings yet

- Donald Worster (1990) Seeing Beyond CultureDocument7 pagesDonald Worster (1990) Seeing Beyond CultureAnonymous n4ZbiJXjNo ratings yet

- Kolen 风景传记:关键问题 2015Document29 pagesKolen 风景传记:关键问题 20151018439332No ratings yet

- Third Knowledge Spaces Between Nature and SocietyDocument25 pagesThird Knowledge Spaces Between Nature and SocietyPyae SetNo ratings yet

- FLEMING ClimateChangeHistory 2014Document11 pagesFLEMING ClimateChangeHistory 2014Kashish GuptaNo ratings yet

- Periodizing World History PDFDocument14 pagesPeriodizing World History PDFLeyreNo ratings yet

- Book Review: From World History Connected June 2011 atDocument4 pagesBook Review: From World History Connected June 2011 atOctavian VeleaNo ratings yet

- Environmental HistoryDocument10 pagesEnvironmental HistoryShreya Rakshit0% (1)

- Seeing The Wood and The Trees: Why Environmental History MattersDocument8 pagesSeeing The Wood and The Trees: Why Environmental History Mattersshiv161No ratings yet

- Hall, A. (2022) That Fine Rain That Soaks You ThroughDocument12 pagesHall, A. (2022) That Fine Rain That Soaks You ThroughAntonio OscarNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 09 00474Document11 pagesSustainability 09 00474martha aulia marcoNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 3.109.20.163 On Sat, 11 Jun 2022 04:41:10 UTCDocument30 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 3.109.20.163 On Sat, 11 Jun 2022 04:41:10 UTCPrashant AnandNo ratings yet

- LEIDO Heise-LocalRockGlobal-2004Document28 pagesLEIDO Heise-LocalRockGlobal-2004Juan Camilo Lee PenagosNo ratings yet

- Presentasi Genealogies of The Global FeatherstoneDocument7 pagesPresentasi Genealogies of The Global FeatherstoneJorge de La BarreNo ratings yet

- Worster 2 1 PDFDocument13 pagesWorster 2 1 PDFFrank Molano CamargoNo ratings yet

- 12) Colonialism in The Anthropocene - The Political Ecology of The Money-Energy-Technology ComplexDocument15 pages12) Colonialism in The Anthropocene - The Political Ecology of The Money-Energy-Technology ComplexFabian Mauricio CastroNo ratings yet

- Carson Future Environmental HistoryDocument76 pagesCarson Future Environmental HistoryPiyush TiwariNo ratings yet

- El Nino in World History 1St Edition Richard Grove Download 2024 Full ChapterDocument30 pagesEl Nino in World History 1St Edition Richard Grove Download 2024 Full Chapterbarbara.carter575100% (11)

- Essay On Indus Valley CivilizationDocument3 pagesEssay On Indus Valley Civilizationdnrlbgnbf100% (2)

- 4 IntroductionTheMediaCommons-Murphy2017Document18 pages4 IntroductionTheMediaCommons-Murphy2017Matúš BocanNo ratings yet

- Routes Beyond Gandhara Buddhist Rock Carvings in The Context of The Early Silk RoadsDocument535 pagesRoutes Beyond Gandhara Buddhist Rock Carvings in The Context of The Early Silk Roadsgeyteeara_599666046No ratings yet

- Global Environmental Change: Lists Available atDocument10 pagesGlobal Environmental Change: Lists Available atMateus ArndtNo ratings yet

- Conservation Paleobiology: Science and PracticeFrom EverandConservation Paleobiology: Science and PracticeGregory P. DietlNo ratings yet

- Conservation Through Ages: ObjectivesDocument7 pagesConservation Through Ages: Objectivesmann chalaNo ratings yet

- Melosi 1993 City Environmental HistoryDocument24 pagesMelosi 1993 City Environmental HistoryAmrElsherifNo ratings yet

- University of Kirkuk College of Engineering Civil DepartmentDocument3 pagesUniversity of Kirkuk College of Engineering Civil DepartmentAhmed falahNo ratings yet

- Binford - Mobility Housing and EnvironmentDocument35 pagesBinford - Mobility Housing and EnvironmentjoaofontanelliNo ratings yet

- The Social Metabolism A Socio EcologicalDocument35 pagesThe Social Metabolism A Socio EcologicalSalvador PenicheNo ratings yet

- Mazlish Comparing World GlobalDocument12 pagesMazlish Comparing World GlobalIván Parada HernándezNo ratings yet

- The Problem ofDocument24 pagesThe Problem ofGeraldo CoutoNo ratings yet

- History and Origin of GlobalizationDocument29 pagesHistory and Origin of Globalizationblaze14911No ratings yet

- Globalizing Legal HistoryDocument11 pagesGlobalizing Legal HistoryEstudante NordesteNo ratings yet

- Buell EcocriticismEmergingTrends 2011Document30 pagesBuell EcocriticismEmergingTrends 2011Aisha RahatNo ratings yet

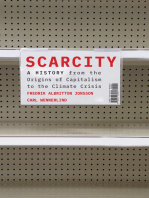

- Scarcity: A History from the Origins of Capitalism to the Climate CrisisFrom EverandScarcity: A History from the Origins of Capitalism to the Climate CrisisNo ratings yet

- History and the Climate Crisis: Environmental history in the classroomFrom EverandHistory and the Climate Crisis: Environmental history in the classroomNo ratings yet

- After The Ice: A Global Human History 20,000-5000 BC. by Steven MithenDocument3 pagesAfter The Ice: A Global Human History 20,000-5000 BC. by Steven MithenN HasibNo ratings yet

- Disrupted Landscapes: State, Peasants and the Politics of Land in Postsocialist RomaniaFrom EverandDisrupted Landscapes: State, Peasants and the Politics of Land in Postsocialist RomaniaNo ratings yet

- Social Forces, University of North Carolina PressDocument9 pagesSocial Forces, University of North Carolina Pressishaq_4y4137No ratings yet

- CABRAL. Horizontality, Negotiation, and Emergence: Toward A Philosophy of Environmental History (2021)Document25 pagesCABRAL. Horizontality, Negotiation, and Emergence: Toward A Philosophy of Environmental History (2021)DaniloMenezesNo ratings yet

- WIREs Climate Change - 2023 - Mercer - Imperialism Colonialism and Climate Change ScienceDocument17 pagesWIREs Climate Change - 2023 - Mercer - Imperialism Colonialism and Climate Change ScienceYéla Tan PuchakiNo ratings yet

- White - 1990 - Environmental History, Ecology, and MeaningDocument7 pagesWhite - 1990 - Environmental History, Ecology, and MeaningDaniloMenezesNo ratings yet

- Bernhard - New 2022Document24 pagesBernhard - New 2022Muhammad AtifNo ratings yet

- The New One 4Document26 pagesThe New One 4Muhammad AtifNo ratings yet

- The New 1Document4 pagesThe New 1Muhammad AtifNo ratings yet

- Alaimo Manifesto 1.1Document3 pagesAlaimo Manifesto 1.1Muhammad AtifNo ratings yet

- Point of Sale - Chapter 3Document6 pagesPoint of Sale - Chapter 3Marla Angela M. JavierNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Foundations of American DemocracyDocument9 pagesUnit 1 - Foundations of American DemocracybanaffiferNo ratings yet

- Intacc 1 NotesDocument19 pagesIntacc 1 NotesLouiseNo ratings yet

- Poultry: Professional Products For The Poultry IndustryDocument1 pagePoultry: Professional Products For The Poultry IndustryzoilaNo ratings yet

- Yamuna Action PlanDocument12 pagesYamuna Action PlanShashank GargNo ratings yet

- McDonald's RecipeDocument18 pagesMcDonald's RecipeoxyvilleNo ratings yet

- Propulsive PowerDocument13 pagesPropulsive PowerWaleedNo ratings yet

- Team2 - Rizal's Life in Paris and GermanyDocument26 pagesTeam2 - Rizal's Life in Paris and Germanydreianne26No ratings yet

- Accomplishment and Narrative Report OctDocument4 pagesAccomplishment and Narrative Report OctGillian Bollozos-CabuguasNo ratings yet

- Grade 12 Mathematical Literacy: Question Paper 1 MARKS: 150 TIME: 3 HoursDocument53 pagesGrade 12 Mathematical Literacy: Question Paper 1 MARKS: 150 TIME: 3 HoursOfentse MothapoNo ratings yet

- Manual Murray OkDocument52 pagesManual Murray OkGIOVANNINo ratings yet

- VW Touareg 2 Brake System EngDocument111 pagesVW Touareg 2 Brake System EngCalin GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Polaris Ranger 500 ManualDocument105 pagesPolaris Ranger 500 ManualDennis aNo ratings yet

- Message From The School Head, Roy G. CrawfordDocument6 pagesMessage From The School Head, Roy G. Crawfordapi-22065138No ratings yet

- Mini Lecture Morphology of Skin LesionDocument48 pagesMini Lecture Morphology of Skin LesionAlkaustariyah LubisNo ratings yet

- Lectra Fashion e Guide Nurturing EP Quality Logistics Production Crucial To Optimize enDocument8 pagesLectra Fashion e Guide Nurturing EP Quality Logistics Production Crucial To Optimize eniuliaNo ratings yet

- Stop TB Text Only 2012Document30 pagesStop TB Text Only 2012Ga B B OrlonganNo ratings yet

- SCAM (Muet)Document6 pagesSCAM (Muet)Muhammad FahmiNo ratings yet

- SlumsDocument6 pagesSlumsRidhima Ganotra100% (1)

- Periyava Times Apr 2017 2 PDFDocument4 pagesPeriyava Times Apr 2017 2 PDFAnand SNo ratings yet

- Ch05 P24 Build A ModelDocument5 pagesCh05 P24 Build A ModelKatarína HúlekováNo ratings yet

- 6 - Cash Flow StatementDocument42 pages6 - Cash Flow StatementBhagaban DasNo ratings yet

- Oracle E-Business Suite TechnicalDocument7 pagesOracle E-Business Suite Technicalmadhugover123No ratings yet

- Henri Fayol A StrategistDocument13 pagesHenri Fayol A StrategistTerence DeluNo ratings yet

- 2 CSS Word FileDocument12 pages2 CSS Word Fileronak waghelaNo ratings yet