Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Differentiation Between Malignant and Benign Gastric Ulcers: CT Virtual Gastroscopy Versus Optical Gastroendoscopy1

Uploaded by

Dipak Kumar YadavOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Differentiation Between Malignant and Benign Gastric Ulcers: CT Virtual Gastroscopy Versus Optical Gastroendoscopy1

Uploaded by

Dipak Kumar YadavCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/26258241

Differentiation between Malignant and Benign Gastric Ulcers: CT Virtual

Gastroscopy versus Optical Gastroendoscopy1

Article in Radiology · July 2009

DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2522081249 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

25 7,472

8 authors, including:

Yu-Ting Kuo Chien-Hung Lee

Chi-Mei Medical Center Kaohsiung Medical University

136 PUBLICATIONS 2,066 CITATIONS 284 PUBLICATIONS 5,350 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Tsyh-Jyi Hsieh Wan-Ting Huang

Kaohsiung Medical University Taipei Medical University Hospital

60 PUBLICATIONS 1,000 CITATIONS 65 PUBLICATIONS 933 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

The association between regular use of aspirin and the prevalence of prostate cancer: Results from the National Health Interview Survey View project

sugar-sweetened beverages(SSB) intake, obesity, and inflammation View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Yu-Ting Kuo on 30 January 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Note: This copy is for your personal non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready

copies for distribution to your colleagues or clients, contact us at www.rsna.org/rsnarights.

䡲 GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING

Differentiation between

Malignant and Benign Gastric

Ulcers: CT Virtual Gastroscopy versus

Optical Gastroendoscopy1

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

Chiao-Yun Chen, MD

Purpose: To retrospectively compare computed tomographic virtual

Yu-Ting Kuo, MD, PhD

gastroscopy (VG) and conventional optical gastroendos-

Chien-Hung Lee, PhD

copy for the differentiation of malignant and benign gastric

Tsyh-Jyi Hsieh, MD ulcers.

Chang-Ming Jan, MD

Twei-Shiun Jaw, MD, MMS Materials and The institutional review board approved this study and

Wan-Ting Huang, MD Methods: confirmed that informed consent was not required. Gas-

Fang-Jung Yu, MD tric ulcers in 115 patients (mean age, 64.7 years; range,

31– 86 years; 61 men, 54 women) were evaluated by using

endoscopy and VG. Ulcer shape, base, and margin and

periulcer folds were evaluated by two independent review-

ers. Malignant gastric ulcers were identified by irregular,

angulated, or geographic shape; uneven base; irregular or

asymmetric edges; and disrupted or moth-eaten appear-

ance of periulcer folds near the crater edge and/or clubbed

or fused folds. Benign gastric ulcers were identified by

smooth and regular shapes, even bases, clearly demar-

cated and regular edges, and folds that tapered and con-

verged toward the ulcer. The performance of VG and

endoscopy for the diagnosis of benign and malignant gas-

tric ulcers was evaluated by using histopathologic results

as the reference standard. The McNemar test was used to

compare VG and endoscopic data. A P value less than .05

was considered to indicate a significant difference.

Results: At histopathologic examination, 39 gastric ulcers were

benign, while 76 were malignant. VG and endoscopy had

sensitivities of 92.1% (70 of 76) and 88.2% (67 of 76),

respectively, for overall diagnosis of malignant gastric ul-

cers, and specificities of 91.9% (34 of 37) and 89.5% (34 of

38), respectively, for overall diagnosis of malignant gastric

ulcers. Endoscopy was more sensitive in depicting malig-

nancy according to ulcer base (85.5% [65 of 76] vs 68.4%

1

From the Department of Medical Imaging (C.Y.C., Y.T.K., [52 of 76]) (P ⫽ .034), and VG was more specific in

T.J.H., T.S.J.), Division of Gastroenterology, Department depicting malignancy according to ulcer margin (78.4%

of Internal Medicine (C.M.J., F.J.Y.), and Department of [29 of 37] vs 63.2% [24 of 38]) (P ⫽ .034).

Pathology (W.T.H.), Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital,

No. 100 Tz-You First Road, Kaohsiung City, 807 Taiwan;

Conclusion: VG and endoscopy were almost equally useful in distin-

Departments of Radiology (C.Y.C., Y.T.K., T.J.H., T.S.J.)

guishing between malignant and benign gastric ulcers.

and Internal Medicine (C.M.J.), and Department of Public

Health, College of Health Science (C.H.L.), Kaohsiung Med-

ical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan. From the 2006 RSNA 娀 RSNA, 2009

Annual Meeting. Received July 31, 2008; revision requested

September 2; revision received December 15; accepted Supplemental material: http://radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi

January 13, 2009; final version accepted March 3. Address

/content/full/2522081249/DC1

correspondence to F.J.Y. (e-mail:yufj@kmu.edu.tw ).

姝 RSNA, 2009

410 radiology.rsnajnls.org ▪ Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

G

astric cancer is one of the most in fact, malignant (8,9). However, be- abdominal CT and 5 years of experience

common causes of death from cause endoscopy is an expensive and in three-dimensional endoluminal ap-

cancer worldwide (1,2). It is the invasive procedure, many patients, proaches and interpretation) identified

second-most common cause of death even those at higher risk levels, might 135 patients with gastric ulcers who had

due to cancer in Asians from China, refuse to undergo such essential endo- undergone endoscopic examination and

Japan, and Korea (3). While it is one of scopic examinations. biopsy, as well as VG, at our institution

the least common cancers in North While investigators (10–14) have between May 2003 and August 2007. All

America, it is the eighth leading cause of found computed tomographic (CT) of the patients in our study were Tai-

cancer death in the United States. In colonography to be a potent imaging wanese. Twenty patients were excluded

2006, there were reported to be more tool for the detection and screening of because they were lost during follow-

than 22 280 new gastric cancer cases, colon cancer, CT has not been widely up, so no final diagnosis was made. The

resulting in about 11 430 deaths in the used for the stomach (15,16). Fortu- remaining 115 patients, with either ma-

United States (4). nately, gastric CT imaging by means of lignant (n ⫽ 76) or benign (n ⫽ 39)

Early diagnosis of this malignancy is three-dimensional virtual gastroscopy gastric ulcers, were included in the

crucial because patient outcome is de- (VG) and air distention of the stomach study. The clinical indications that re-

pendent on detecting it in its initial now makes better detection of subtle sulted from CT examinations in the 76

stages. In Taiwan, for example, overall mucosal changes possible, and it can be patients with malignant ulcers were that

5-year survival rates for this cancer used to provide images that are almost patients were suspected of having ma-

have been reported to be 97.9% for as detailed as those produced by using lignant gastric ulcers at endoscopy (n ⫽

stage IA disease, 92.9% for stage IB dis- endoscopy (15,16). 76). The indications for the 39 patients

ease, 63.2% for stage II disease, 50.1% We therefore conducted this retro- with benign ulcers were as follows: (a)

for stage IIIA disease, 28.7% for stage spective study to compare the perfor- patients were suspected of having ma-

IIIB disease, and 9.3% for stage IV dis- mance of CT VG with that of conven- lignant gastric ulcers at endoscopy (n ⫽

ease (5). tional optical gastroendoscopy in regard 7); (b) intractable gastric ulcers did not

Patients with gastric ulcers have to the differentiation of malignant and heal after 8 weeks of treatment with

been found to be at greater risk for de- benign gastric ulcers. proton-pump inhibitors (n ⫽ 8); (c) ul-

veloping gastric cancer (6,7). Because cer size of more than 3 cm in diameter

malignancy is best treated in its early at endoscopy (n ⫽ 8); (d) gastric ulcers

stages, it is usually recommended that Materials and Methods in the gastric body where it was difficult

all instances of gastric ulcers be fol- to exclude the possibility of malignancy

lowed up with conventional endoscopy Patients at endoscopy (n ⫽ 8); (e) previous bi-

and histopathologic studies until they The protocol for this retrospective opsy results showed cell dysplasia or

have healed to ensure that they are not, study was approved by the institutional atypia (n ⫽ 5); and (f) gastric bleeding

review board of our hospital, Kaohsiung (n ⫽ 3) (Fig 1).

Medical University Hospital, which also The mean age of the 115 patients

Advances in Knowledge determined that informed consent could was 64.7 years (age range, 31– 86

䡲 The sensitivity and specificity for be waived for this undertaking. years). These patients included 61 men

the overall diagnosis at virtual After performing a computerized

gastroscopy (VG) were 92.1% search of the medical records in our

and 91.9%, respectively, and hospital’s radiology files, one author Published online before print

88.2% and 89.5%, respectively, (C.Y.C., with 10 years of experience in 10.1148/radiol.2522081249

for the overall diagnosis at endos- Radiology 2009; 252:410 – 417

copy in the detection of malignant

gastric ulcers. Implication for Patient Care Abbreviation:

VG ⫽ virtual gastroscopy

䡲 Endoscopy was more sensitive for 䡲 While endoscopy and VG are al-

detection of malignancy based on most equally capable of depicting Author contributions:

ulcer base criteria (P ⫽ .034), malignancy by using the criteria Guarantors of integrity of entire study, C.Y.C., C.M.J.,

T.S.J., F.J.Y.; study concepts/study design or data acqui-

and VG was more specific for de- that we studied, decreased dis-

sition or data analysis/interpretation, all authors; manu-

tection of malignancy based on comfort of VG examination may

script drafting or manuscript revision for important intel-

ulcer margin criteria (P ⫽ .034); make it a preferred means of dis- lectual content, all authors; manuscript final version ap-

VG was about as accurate as en- tinguishing benign from malignant proval, all authors; literature research, C.Y.C., C.M.J.,

doscopy in identifying malignant gastric ulcers in the future, partic- T.S.J., W.T.H., F.J.Y.; clinical studies, C.Y.C., Y.T.K.,

ulcer shapes, was more accurate ularly for patients who have con- T.J.H., C.M.J., T.S.J., W.T.H., F.J.Y.; statistical analysis,

in finding the ulcer margin and traindications to or who are un- C.Y.C., C.H.L., F.J.Y.; and manuscript editing, C.Y.C.,

Y.T.K., T.J.H., C.M.J., F.J.Y.

perifold, but was less accurate in able to undergo conventional

depicting ulcer base. endoscopy. Authors stated no financial relationship to disclose.

Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009 ▪ radiology.rsnajnls.org 411

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

(mean age, 65.9 years; range, 38 – 84 detector CT scanner (Brilliance 190P; tained from the diaphragmatic domes to 2

years) and 54 women (mean age, 63.4 Philips Medical Systems, Cleveland, Ohio) cm below the lower margin of the air-

years; range, 31– 86 years). The age dis- (26 patients). All patients had fasted for at distended gastric body. The 16-section mul-

tribution was comparable between the least 8 hours and had received 6 g of gas- tidetector CT scanner parameters were set

sexes (P ⫽ .266, t test). The elapsed producing crystals with 10 mL water orally at 1.25-mm collimation, 1.375 pitch, 27.5-

time between CT and endoscopy was to enable distention of the stomach before mm/sec table speed, 1.25-mm reconstruc-

within 7 days (mean, 3 days). Of these the procedures were performed. All of the tion thickness, 0.625-mm reconstruction

patients, 112 underwent endoscopy patients were placed in the supine position interval, 250–300 mAs, and 120 kVp. The

prior to CT VG, and three patients with with their right side elevated at approxi- 64-section multidetector CT parameters

gastric bleeding underwent CT VG prior mately 30°. To ensure adequate gastric dis- were set at 0.625-mm collimation, 1.142

to endoscopy. All of the diagnoses were tention, a scanogram was obtained. An ad- pitch, 0.75-second rotation time, 1.0-mm

confirmed with histopathologic exami- ditional 3 g of gas-producing crystals were reconstruction thickness, 0.5-mm recon-

nation results, and all of the patients given to patients determined to have insuf- struction interval, 250–300 mAs, and 120

with a diagnosis of a benign ulcer were ficient air distention. CT scans were ob- kVp.

followed up for more than 6 months.

Figure 1

Endoscopy

Endoscopy was performed with the pa-

tient in the left lateral position after ad-

ministration of oropharyngeal anesthesia

(Xylocaine; AstraZeneca, Sweden). En-

doscopy, as well as directed biopsy, was

performed by two board-certified experi-

enced gastroenterologists (F.J.Y. and

C.M.J., with 10 and 20 years of experi-

ence, respectively). We analyzed the dif-

ference in age and sex distribution for the

patients examined. Patterns for the two

characteristics were found to be compa-

rable (P ⫽ .495 for sex, 2 test; P ⫽ .257

for age, t test). End-viewing fiberoptic

panendoscopes (GIF-XQ240; Olympus, Figure 1: Flowchart of study enrollment. ENDO ⫽ endoscopy, FP ⫽ false positive, TP ⫽ true positive.

Tokyo, Japan) were used in all patients.

Six specific chosen directed-biopsy speci-

mens from the edge and base of the ulcer

were collected from each patient. Endo-

Figure 2

scopic evaluations were made (F.J.Y. and

C.M.J.). During analysis of the endo-

scopic features, cases of malignant and

benign ulcers were randomly intermixed.

Each gastroenterologist reviewed the en-

doscopic images and made an indepen-

dent evaluation; they then met with each

other, went over every case, and came to

a consensus evaluation.

CT VG Studies

All of the patients underwent multidetec-

tor CT examination following the routine

procedures designed for patients sus-

pected of having abnormal gastric lesions

in our department. CT examinations

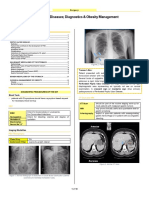

were performed by using either a 16- Figure 2: Images of malignant gastric ulcer in 65-year-old man. (a) VG image shows en face view of ulcer

section multidetector CT scanner (Light- and (b) endoscopic image shows minimal oblique view of ulcer at the gastric part of the body with uneven

ulcer base, irregular ulcer shape, irregular ulcer margin, and associated gastric folds with rugae interruption

Speed H16; GE Healthcare, Milwaukee,

(arrows).

Wis) (89 patients) or a 64-section multi-

412 radiology.rsnajnls.org ▪ Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

Reconstructed images from data are knowing that the images had been ob- on radiologic and endoscopic criteria

routinely stored in our picture archiving tained in patients with gastric ulcers but established for the recognition of each

and communication system before three- not knowing the results of endoscopic and (17,18). Our diagnoses were made by

dimensional image processing is per- pathologic examinations. Each of the two examining the available morphologic

formed. The VG images were indepen- gastrointestinal radiologists created and features of ulcer shape, base, and mar-

dently created and interpreted in the reviewed the VG features and made a gins and the relation of the ulcer to the

three-dimensional workstation (AW 4.1; record independently and then met with surrounding folds. Malignant gastric ul-

GE Healthcare) by two authors (T.S.J. each other to go over every case and cers were identified by shapes that were

and Y.T.K., with 10 and 12 years of ab- come to a consensus evaluation. irregular, angulated, or geographic;

dominal CT experience, respectively, as bases that were uneven; edges that

well as 4 years of experience each in the Image Evaluation were irregular or asymmetric; and folds

three-dimensional endoluminal ap- The locations of the gastric ulcers were that appeared to be disrupted or “moth-

proach). During analysis of the VG fea- recorded on both VG and endoscopic eaten” near the crater edge and/or were

tures, the malignant and benign ulcer images. The benign gastric ulcers were clubbed or fused (Fig E1, http:

cases were randomly intermixed. The differentiated from the malignant gas- //radiology.rsnajnls.org/cgi/content/full

two authors analyzed the VG images tric ulcers, and this process was based /2522081249/DC1; Fig 2). Benign gastric

ulcers were identified by shapes that

Figure 3 were smooth and regular, bases that

were even, edges that were clearly de-

marcated and regular, and periulcer folds

that tapered and converged toward the

ulcer (Fig E2, http://radiology.rsnajnls

.org/cgi/content/full/2522081249/DC1;

Fig 3).

A standardized form was completed

independently by the two radiologists

who interpreted the VG images and by

the two gastroenterologists who inter-

preted the endoscopic images. On this

form, the evaluators noted whether the

shapes, bases, margins, or surrounding

folds on each image had primarily be-

nign or malignant features. In addition,

the two gastroenterologists evaluating

the endoscopic images also noted the

Figure 3: Images of benign gastric ulcer in 37-year-old woman. (a) VG image and (b) endoscopic image show presence or absence of any periulcer

en face view of ulcer at the gastric angle with even ulcer base, regular triangular ulcer shape, regular ulcer margin, color change (redness, discoloration, or

and associated regular gastric folds terminating at the ulcer margin (arrows). spotty bleeding) (19). Radiologists and

gastroenterologists initially made inde-

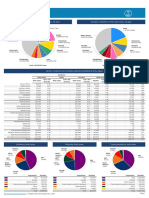

Table 1

Diagnosis of Benign and Malignant Gastric Ulcers according to Criteria at VG and Endoscopy

VG Endoscopy

Periulcer Periulcer

Ulcer Ulcer Ulcer Fold Overall Ulcer Ulcer Ulcer Fold Color Overall

Shape* Base* Margin* Change† Diagnosis* Shape* Base* Margin* Change† Change Diagnosis

Parameter B M B M B M B M B M B M B M B M B M B M B M

No. of benign ulcers (n ⫽ 39) 28 9 30 7 29 8 15 3 34 3 31 7 33 5 24 14 12 5 20 19 34 4

No. of malignant ulcers (n ⫽ 76) 6 70 24 52 2 74 2 42 6 70 8 68 11 65 2 74 5 47 5 71 9 67

Note.—B ⫽ Benign criteria of images, M ⫽ malignant criteria of images.

* Information regarding VG criteria for two patients with benign ulcers was not evaluated, and information regarding endoscopic criteria for one patient with a benign ulcer was not evaluated.

†

No fold change was determined at VG examination for 21 patients with benign ulcers and 32 patients with malignant ulcers, and no fold change was determined at endoscopic examination for

22 patients with benign ulcers and 24 patients with malignant ulcers.

Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009 ▪ radiology.rsnajnls.org 413

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

pendent records, after which they came mucosa layers with varying degrees of

to a consensus diagnosis at VG and en- inflammation or granulomatous tissue

No fold change was determined at VG examination for 21 patients with benign ulcers and 32 patients with malignant ulcers, and no fold change was determined at endoscopic examination for 22 patients with benign ulcers and 24 patients with malignant ulcers.

88.2 (80.8, 95.5)

89.5 (79.5, 99.5)

Overall Diagnosis

doscopy, respectively. infiltration in the lamina propria.

VG results showed that 98.3%

Overall Diagnosis

88.6

(113 of 115) of patients in this study

…

To perform an overall diagnosis by us- had gastric ulcers. Two patients had

93.4 (87.8, 99.1)

51.3 (35.2, 67.3)

ing the individual VG and individual en- flat ulcers, which endoscopy, not VG,

Color Change

doscopic findings for the malignancy of could depict. While endoscopy could

0.847

gastric ulcers, we calculated the ⌽ cor- depict all of the ulcers, it could not be

79.1

relation coefficient for each individual used to differentiate between benign

criterion and the malignancy. These two and malignant ulcers in one patient

Periulcer Fold Change†

sets of coefficients were used as the rel- because the lesion was found at the

90.4 (77.4, 96.2)

70.6 (55.3, 97.6)

* Information regarding VG criteria for two patients with benign ulcers was not evaluated, and information regarding endoscopic criteria for one patient with a benign ulcer was not evaluated.

ative weight for developing a diagnostic distal antrum, and a complete view

score. The receiver operating character- was impossible.

0.913

Endoscopy

85.5

istic curve method was employed to find As can be seen in Tables 1 and 2,

the cutoff value for the optimal diagnostic the interobserver agreement in the

Diagnostic Accuracy, Sensitivity, and Specificity of Criteria of VG and Endoscopy Associated with Malignant Gastric Ulcers

97.4 (91.6, 100.0)

63.2 (44.6, 76.4)

accuracy (ie, the highest sum of the values differentiation of malignant and be-

Ulcer Margin*

for sensitivity and specificity). nign gastric ulcers by using VG or en-

0.900

doscopy showed excellent reproduc-

86.0

Statistical Analysis ibility ( ⫽ 0.879 – 0.937 for VG and

By using histopathologic findings as a 0.847– 0.919 for endoscopy). For the

85.5 (75.9, 92.6)

86.8 (65.7, 92.2)

Note.—See Table 1 for numbers used to calculate sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy percentages. Data in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

generally accepted standard of evalua- diagnosis of malignant gastric ulcers,

Ulcer Base*

0.870

tion, we compared the sensitivities, VG had a sensitivity and specificity of

86.0

specificities, and accuracies of the diag- 92.1% and 75.7%, respectively, based

noses based on the image characteris- on ulcer shape, 68.4% and 81.1%

89.5 (80.8, 95.5)

81.6 (65.7, 92.2)

tics on VG and endoscopic images. The based on ulcer base, 97.4% and 78.4%

Ulcer Shape*

sensitivities and specificities were re- based on ulcer margin, and 95.5% and

0.919

86.8

ported with corresponding 95% confi- 83.3% based on periulcer fold change

dence intervals. Interobserver variability, and had an average accuracy of more

91.9 (82.9, 100.0)

Overall Diagnosis*

92.1 (85.9, 98.3)

for benign and malignant ulcer evaluation than 72.6%. For the diagnosis of ma-

resulting from VG and endoscopic exam- lignant gastric ulcers, endoscopy had a

inations, was assessed by calculating the sensitivity and specificity of 89.5% and 92.0

statistic. Statistics were interpreted by 81.6%, respectively, based on ulcer …

using the following scale: fair agreement shape, 85.5% and 86.8% based on ul-

Periulcer Fold Change†

95.5 (85.8, 100.0)

83.3 (65.3, 100.0)

was indicated by 0.21– 0.40; moderate cer base, 97.4% and 63.2% based on

agreement, 0.41– 0.60; good agreement, ulcer margin, and 90.4% and 70.6%

0.61– 0.80; and excellent agreement, based on periulcer fold change.

0.929

91.9

0.81–1.00 (20). Consistency between VG For the overall diagnosis performed

and endoscopic results was evaluated by by using the individual VG and individ-

97.4 (89.6, 99.8)

78.4 (62.5, 90.2)

using the McNemar test. A P value less ual endoscopic findings for the malig-

Ulcer Margin*

VG

than .05 was considered to indicate a sig- nancy of gastric ulcers, the correlation

P values less than .05 indicated a significant difference for values.

0.933

91.2

nificant difference. All statistical opera- coefficients were 0.69, 0.47, 0.80, and

tions were performed by using software 0.80 for ulcer shape, ulcer base, ulcer

68.4 (56.4, 77.9)

81.1 (65.7, 92.2)

(Stata, SE version 9.1 for Windows, margin, and periulcer fold change, re-

Ulcer Base*

2005; Stata, College Station, Tex). spectively, for VG findings and 0.71,

0.879

0.70, 0.68, and 0.6, respectively, for

72.6

endoscopic findings. The correlation-

Results weighted overall scores were calcu-

92.1 (85.9, 98.3)

75.7 (56.3, 85.8)

lated as follows: (0.69 䡠 shape) ⫹

Ulcer Shape*

Of the 115 patients observed in this

study, 39 had histopathologically (0.47 䡠 base) ⫹ (0.80 䡠 margin) ⫹

0.937

86.7

proved benign gastric ulcers, and 76 (0.80 䡠 fold change) for VG diagnosis

had malignant gastric ulcers (24 at and (0.71 䡠 shape) ⫹ (0.70 䡠 base) ⫹

Specificity (%)

Sensitivity (%)

Accuracy (%)

stage T1, 29 at stage T2, and 23 at (0.68 䡠 margin) ⫹ (0.60 䡠 fold change)

Value‡

Parameter

Table 2

stage T3). Histopathologic study re- for endoscopic diagnosis, with a score

sults revealed that all of the benign of 1 for positive and a score of 0 for

†

ulcers had eroded or defective gastric negative (or no fold change) findings.

414 radiology.rsnajnls.org ▪ Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

The cutoff values for VG findings were change and had an average accuracy of diagnosed as being malignant (Fig 6). In

2.29 and 1.49, respectively, for patients more than 79.1% (Table 2). addition, one malignant gastric ulcer

with and those without the periulcer fold As shown in Table 3, VG and endos- was misdiagnosed as benign at VG but

change and 2.09 and 0.70, respectively, copy had significantly different diagnostic was correctly diagnosed at endoscopy

for endoscopic findings. Patients with results in the evaluation of ulcer base and (Fig E3, http://radiology.rsnajnls.org

overall scores that were larger or equal to ulcer margin (both P ⫽ .034, McNemar /cgi/content/full/2522081249/DC1).

those of the corresponding cutoff values test). Compared with VG, endoscopy was

were determined to have a malignancy. found to more sensitively depict malig-

The sensitivity and specificity for the nancy based on the unevenness of the Discussion

overall diagnosis at VG were 92.1% and ulcer base (Fig 4), while VG had better In this study, we compared the perfor-

91.9%, respectively, and 88.2% and specificity based on the irregularity of the mance of VG and endoscopy in the dif-

89.5% at endoscopy. In addition, endos- ulcer margin (Fig 5). ferentiation between malignant and be-

copy showed 93.4% sensitivity and With both VG and endoscopic crite- nign gastric ulcers and found the diag-

51.3% specificity for periulcer color ria, two benign gastric ulcers were mis- nostic results at VG to be comparable

with those at endoscopy.

VG is a new noninvasive technique

Figure 4 capable of creating high-quality detailed

three-dimensional images of subtle mu-

cosal changes in the stomach. Its image

quality is diagnostically comparable

with that provided at optical endoscopy

(15,21). VG has a wider viewing field

than endoscopy and is better for evalu-

ating high lesser curvature sites and du-

odenal bulbs than conventional optical

endoscopy (19). Because views ob-

tained with a virtual camera can be ad-

justed without substantial limitations,

and because they can be re-formed ret-

rospectively to clear up any blind spots,

VG produces better overall views of the

whole ulcer and better views of the ul-

cer margin than endoscopy (P ⫽ .034).

Because its view comes from several an-

Figure 4: Images of malignant gastric ulcer in 65-year-old woman, with atypical benign morphologic fea-

gles, it offers a more precise measure-

ture of the ulcer base on VG image. (a) VG image shows en face view of ulcer at the low gastric body with even

ment of the abnormality. Even more im-

ulcer base (arrow). (b) Endoscopic image shows oblique view of ulcer and an uneven ulcer base (arrow).

portant, VG is technically less invasive

than endoscopy.

Table 3

Diagnostic Comparison of Individual and Overall Criteria for Imaging Findings at VG and Endoscopy for Patients with Gastric Ulcers

Ulcer Shape at Ulcer Base at Ulcer Margin at Periulcer Fold Change Overall Diagnosis at

Endoscopy Endoscopy Endoscopy at Endoscopy* Endoscopy

Parameter Benign Malignant Benign Malignant Benign Malignant Benign Malignant Benign Malignant

VG†

Benign 29 5 34 19 23 7 11 5 31 8

Malignant 8 70 8 51 1 81 2 40 10 63

2 For McNemar test‡ 0.69 (.405) 4.48 (.034) 4.50 (.034) 1.29 (.257) 0.22 (.637)

Note.—Unless otherwise indicated, data are numbers of ulcers.

* Only 58 patient pairs were available for the comparison of periulcer fold change between VG and endoscopy.

†

Patients with benign or malignant ulcers (n ⫽ 112) were compared with the same individual criteria as for those undergoing endoscopy. Data from three patients were not used: Two patients

had flat ulcers, which could not be detected at VG, and another patient had an ulcer at the distal antrum, and this could not be used to differentiate a benign from a malignant ulcer because a

complete view was impossible.

‡

Data in parentheses are P values.

Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009 ▪ radiology.rsnajnls.org 415

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

Figure 5

Figure 5: Images of benign gastric ulcer in 59-year-old man, with atypical malignant morphologic features of ulcer margin and periulcer fold change on endoscopic

image. VG images show the (a) profile view and (b) en face view of ulcer at gastric antrum with even ulcer base, regular oval ulcer shape, regular ulcer margin, and associ-

ated regular gastric folds terminating at the ulcer margin (arrows). (c) Endoscopic image shows oblique view of ulcer and asymmetric edema of ulcer margin (arrowhead)

and associated gastric folds with bulbous rugae enlargement (arrow). P ⫽ pylorus.

VG, however, has several disadvan-

tages as well. First, VG does not depict Figure 6

color change, which makes it difficult to

detect flat lesions or to evaluate subtle

changes at the ulcer base. In our study,

two patients had flat ulcers that were

undetectable at VG. Endoscopy was

also found to produce a better view of

the ulcer base (P ⫽ .034), partially be-

cause of its depiction of the color

change. Second, the use of recon-

structed algorithms is still far from

yielding perfect “natural” images. En-

doscopy, which has a pixel size of

around 0.03 mm/pixel, has better spa-

tial resolution than VG (pixel size

around 0.59 – 0.82 mm/pixel), which

makes it more difficult to detect subtle

changes in small lesions at VG. In our Figure 6: Images of acute benign gastric ulcer in 52-year-old man exhibit malignant morphologic features.

study, use of VG led to the misdiagnosis (a) VG image shows en face view of ulcer and (b) endoscopic image shows minimal oblique view of ulcer at

of one malignant gastric ulcer as benign, gastric body with uneven ulcer base, irregular ulcer shape, and irregular ulcer margin. Rugae interruption

while endoscopy clearly depicted the (arrow) and bulbous enlargement (arrowheads) are evident on a but not on b; this is because of the limited

characteristics needed to make an accu- field of view.

rate diagnosis. Additionally, when using

VG, there is a substantial dose of ioniz-

ing radiation, and biopsies cannot be

collected for histopathologic evaluation. most malignant gastric ulcers from be- Although VG may be as good as en-

Thus, optical endoscopy must still be nign ones, acute benign ulcers with se- doscopy in the depiction of a malignancy,

performed for confirmation. In fact, in vere periulcer edema might mimic ma- it must be performed by well-trained ra-

many instances, endoscopy is per- lignant ulcers. In our study, two acute diologists who can process a relatively

formed as a concomitant. benign ulcers were misdiagnosed as ma- large number of CT images and who are

We found that although using endo- lignant at both VG and endoscopy in familiar with the endoscopic appearance

scopic criteria can help differentiate evaluation of all criteria. of gastric ulcers beforehand. While CT is

416 radiology.rsnajnls.org ▪ Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009

GASTROINTESTINAL IMAGING: Virtual Gastroscopy and Endoscopy of Gastric Ulcers Chen et al

not currently performed as a routine ex- good potential alternative means for 11. Sosna J, Morrin MM, Kruskal JB, Lavin PT,

amination for the detection of gastric ul- evaluating ulcers. Further prospective Rosen MP, Raptopoulos V. CT colonography

of colorectal polyps: a metaanalysis. AJR

cers, multidetector CT, with continued randomized studies comparing VG and

Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1593–1598.

advancements in CT scanners and com- optical endoscopy are required to inves-

puter technology, may play an increas- tigate the overall efficacy and cost-effec- 12. Pickhardt PJ, Choi JR, Hwang I, et al. Com-

puted tomographic virtual colonoscopy to screen

ingly important role in the detection of tiveness of VG.

for colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic adults.

malignant gastric ulcers. Whether this N Engl J Med 2003;349:2191–2200.

will translate into improved overall sur- References

13. Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, et al. CT

vival rates for patients with gastric can- 1. Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global

colonography versus colonoscopy for the de-

cer, or to cost savings, is still unclear. cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin

tection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med

Randomized, double-blinded prospective 2005;55:74 –108.

2007;357:1403–1412.

studies with larger patient groups are re- 2. Crew KD, Neugut AI. Epidemiology of gas- 14. Neri E, Giusti P, Battolla L, et al. Colorectal

quired to validate the role of VG in the tric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2006;12: cancer: role of CT colonography in preoper-

diagnosis of gastric cancer. 354 –362. ative evaluation after incomplete colonos-

This study had some limitations. 3. Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, et al. copy. Radiology 2002;223:615– 619.

There may have been some selection bias Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current 15. Inamoto K, Kouzai K, Ueeda T, Marukawa

caused by limiting the enrollment of pa- evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol 2008;9: T. CT virtual endoscopy of the stomach:

279 –287. comparison study with gastric fiberscopy.

tients to those with gastric ulcers who

4. Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, et al. Cancer Abdom Imaging 2005;30:473– 479.

underwent CT. This may have led to an

statistics, 2006. CA Cancer J Clin 2006;56: 16. Ogata I, Komohara Y, Yamashita Y, Mitsu-

overestimation in the ability of VG to de-

106 –130. zaki K, Takahashi M, Ogawa M. CT evalua-

pict gastric ulcers. However, because the

tion of gastric lesions with three-dimensional

aim of this study was to compare the abil- 5. Wu CW, Lui WY. Current management of

display and interactive virtual endoscopy:

ity of the two modalities to help differen- gastric cancer in Taiwan. Asia J Surg 2001;

comparison with conventional barium study

24:253–257.

tiate malignant from benign gastric ul- and endoscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;

cers, rather than investigating the detect- 6. Hansson LE, Nyren O, Hsing AW, et al. The 172:1263–1270.

ability of gastric ulcers with VG, this risk of stomach cancer in patients with gas-

17. Gabrielsson N. Benign and malignant gastric

tric or duodenal ulcer disease. N Engl J Med

overestimation may not substantially ulcers: evaluation of differential diagnostics

1996;335:242–249.

have changed the results of this study. In in roentgen examination and endoscopy. En-

7. Andrade MH, Silva E, Mares-Guia M. A plau- doscopy 1972;4:73–78.

addition, there was great variation in the

sible identification of the secondary binding 18. Maruyama M, Baba Y. Gastric carcinoma.

elapsed time between the endoscopic and site in trypsin and trypsinogen. Braz J Med

VG examinations. Some benign active ul- Radiol Clin North Am 1994;32:1233–1252.

Biol Res 1990;23:1223–1231.

cers might lose edema after intensive treat- 19. Honmyo U, Misumi A, Murakami A, et al.

8. Mountford RA, Brown P, Salmon PR, Mechanisms producing color change in flat

ment. In our study, one benign ulcer with Alvarenga C, Neumann CS, Read AE. Gas- early gastric cancers. Endoscopy 1997;29:

active bleeding showed less edema at VG tric cancer detection in gastric ulcer disease. 366 –371.

than at endoscopy after 7 days of treatment Gut 1980;21:9 –17.

20. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of

with a proton-pump inhibitor. 9. Moayyedi P, Axon AT. Endoscopy and gas- observer agreement for categorical data. Bi-

In conclusion, this study found that tric ulcers. Endoscopy 1995;27:689 – 693. ometrics 1977;33:159 –174.

VG and endoscopy are almost equally

10. Yee J, Akerkar GA, Hung RK, Steinauer- 21. Kim JH, Eun HW, Goo DE, Shim CS, Auh

useful in distinguishing between malig-

Gebauer AM, Wall SD, McQuaid KR. Colo- YH. Imaging of various gastric lesions with

nant and benign gastric ulcers. The rel- rectal neoplasia: performance characteris- 2D MPR and CT gastrography performed

ative reduction in discomfort of the non- tics of CT colonography for detection in 300 with multidetector CT. RadioGraphics 2006;

invasive VG examination may make it a patients. Radiology 2001;219:685– 692. 26:1101–1116; discussion 1117–1118.

Radiology: Volume 252: Number 2—August 2009 ▪ radiology.rsnajnls.org 417

You might also like

- Surgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Gastrointestinal DiseasesFrom EverandSurgical Pathology of Non-neoplastic Gastrointestinal DiseasesLizhi ZhangNo ratings yet

- 1.2.2. Emergency Abdominal ImagingDocument51 pages1.2.2. Emergency Abdominal ImagingNoura AdzmiaNo ratings yet

- Pathology - Research and PracticeDocument5 pagesPathology - Research and PracticeGabriela MilitaruNo ratings yet

- Initial Investigation and Managenement Benign Ovariam MassesDocument12 pagesInitial Investigation and Managenement Benign Ovariam MassesleslyNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Inflammatory Bowel DiseasesFrom EverandAtlas of Inflammatory Bowel DiseasesWon Ho KimNo ratings yet

- Wa0002Document14 pagesWa0002Katya RizqitaNo ratings yet

- Original Article: A Study On Incidence, Clinical Profile, and Management of Obstructive JaundiceDocument7 pagesOriginal Article: A Study On Incidence, Clinical Profile, and Management of Obstructive Jaundicegustianto hutama pNo ratings yet

- Electrodermal Screening of Biologically Active PoiDocument12 pagesElectrodermal Screening of Biologically Active Poimerk2venezuelaNo ratings yet

- dx2 AkaDocument8 pagesdx2 AkaRADIOLOGI RS UNUDNo ratings yet

- Sahai ADocument7 pagesSahai AramisharehmanNo ratings yet

- Evaluation and Management of Postsurgical Patient.27Document14 pagesEvaluation and Management of Postsurgical Patient.27Josué EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 3 Beatrix NusaDocument6 pagesJurnal 3 Beatrix NusaMerry Beatrix 102016241No ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Oncology: A Critical Multidisciplinary Team ApproachFrom EverandGastrointestinal Oncology: A Critical Multidisciplinary Team ApproachJanusz JankowskiNo ratings yet

- Ren 2024 Phys. Med. Biol. 69 025009Document15 pagesRen 2024 Phys. Med. Biol. 69 025009r496889996No ratings yet

- Imaging in BPHDocument6 pagesImaging in BPHadityaNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Small-Bowel Capsule Endoscopy and Device-Assisted Enteroscopy For Diagnosis and Treatment of Smallbowel Disorders - European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical GuidelineDocument25 pages2015 - Small-Bowel Capsule Endoscopy and Device-Assisted Enteroscopy For Diagnosis and Treatment of Smallbowel Disorders - European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Clinical GuidelineOrlando QuirosNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0022534716309612Document9 pagesPi Is 0022534716309612IGusti Ngurah AgungNo ratings yet

- Piis0022534716309612 PDFDocument9 pagesPiis0022534716309612 PDFIGusti Ngurah AgungNo ratings yet

- Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Imaging of Hepatic NeoplasmsFrom EverandContrast-Enhanced Ultrasound Imaging of Hepatic NeoplasmsWen-Ping WangNo ratings yet

- Comparison of GLIM, SGA, PG-SGA, and PNI in Diagnosing Malnutrition Among Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Surgery PatientsDocument9 pagesComparison of GLIM, SGA, PG-SGA, and PNI in Diagnosing Malnutrition Among Hepatobiliary-Pancreatic Surgery PatientsInna Mutmainnah MusaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study and Management of Pseudocyst of Pancreas: Original Research ArticleDocument5 pagesClinical Study and Management of Pseudocyst of Pancreas: Original Research Articleneel patelNo ratings yet

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria Palpable Abdominal MassSuspected NeoplasmDocument8 pagesACR Appropriateness Criteria Palpable Abdominal MassSuspected NeoplasmAgustinaNo ratings yet

- WA FemaleDocument5 pagesWA FemaleMithun ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonographic Atlas of Splenic LesionsDocument14 pagesUltrasonographic Atlas of Splenic LesionsFlavio RojasNo ratings yet

- Dilemmas in ERCP: A Clinical CasebookFrom EverandDilemmas in ERCP: A Clinical CasebookDaniel K. MulladyNo ratings yet

- Lesiones Subepiteliales PDFDocument16 pagesLesiones Subepiteliales PDFO W Cordova AliagaNo ratings yet

- Practice Patterns and Perioperative Outcomes Of.22Document9 pagesPractice Patterns and Perioperative Outcomes Of.22drhusseinfaour3126No ratings yet

- 727 Outcomes of Antibiotic Use in Ischemic ColitisDocument2 pages727 Outcomes of Antibiotic Use in Ischemic ColitisDonNo ratings yet

- The SAGES Manual of Flexible EndoscopyFrom EverandThe SAGES Manual of Flexible EndoscopyPeter NauNo ratings yet

- 2012 3 FobtDocument7 pages2012 3 FobtcarolinaNo ratings yet

- A Study of Clinical Presentations and Management oDocument4 pagesA Study of Clinical Presentations and Management oMaria AkulinaNo ratings yet

- JIR 338421 A Novel Inflammatory Nutritional Prognostic Scoring System FDocument14 pagesJIR 338421 A Novel Inflammatory Nutritional Prognostic Scoring System FdrelvNo ratings yet

- Olinger Et Al 2024 Added Value of Contrast Enhanced Us For Evaluation of Female Pelvic DiseaseDocument15 pagesOlinger Et Al 2024 Added Value of Contrast Enhanced Us For Evaluation of Female Pelvic DiseaseThesisaurus IDNo ratings yet

- Pancreas and Biliary Tract CytohistologyFrom EverandPancreas and Biliary Tract CytohistologyAbha GoyalNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Bedah - Elsy MulyaDocument14 pagesJurnal Bedah - Elsy MulyaariesfadhliNo ratings yet

- Characterization of Renal Stones Using Gsi: Patient HistoryDocument2 pagesCharacterization of Renal Stones Using Gsi: Patient HistoryAlreem AlhajryNo ratings yet

- GI Surgery Annual: Volume 25From EverandGI Surgery Annual: Volume 25Peush SahniNo ratings yet

- Post-cholecystectomy Bile Duct InjuryFrom EverandPost-cholecystectomy Bile Duct InjuryVinay K. KapoorNo ratings yet

- IPPSDocument6 pagesIPPSAlonso CardenasNo ratings yet

- GatroDocument48 pagesGatronainggolan Debora15No ratings yet

- Batchala 2021Document6 pagesBatchala 2021qrscentralNo ratings yet

- Wa Female PidDocument5 pagesWa Female PidMithun ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Clinical Analysis of 14 Cases of Urachal CarcinomaDocument4 pagesClinical Analysis of 14 Cases of Urachal Carcinomadr.tonichenNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Young AdultsDocument9 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Young AdultsAtika RahmahNo ratings yet

- Wa Pedi MaleDocument5 pagesWa Pedi MaleMithun ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- 4323 22520 1 PBDocument4 pages4323 22520 1 PBFreddy Shanner Chávez VásquezNo ratings yet

- 1686 1698 PDFDocument13 pages1686 1698 PDFRanganadh GuttiNo ratings yet

- Stavros Solid MassesDocument12 pagesStavros Solid MassesPrasann VachhaniNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound Imaging For Assessing Functions of The GI TractDocument17 pagesUltrasound Imaging For Assessing Functions of The GI TractСергей СадовниковNo ratings yet

- Abdominal X RayDocument6 pagesAbdominal X RayLina JohananaNo ratings yet

- BCC and BRGEDocument7 pagesBCC and BRGEZahan LorenaNo ratings yet

- Ajr 14 12935Document6 pagesAjr 14 12935CuauhtémocNo ratings yet

- Chang 2007Document7 pagesChang 2007Ilse PalmaNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Prone and Supine Position Imrt For Endometrial Cancer (2007)Document5 pagesComparison Between Prone and Supine Position Imrt For Endometrial Cancer (2007)Michelle LEINo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Findings of The Gastric Mucosa During Long Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor A Multicenter StudyDocument6 pagesEndoscopic Findings of The Gastric Mucosa During Long Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor A Multicenter StudySamuel0651No ratings yet

- Endoscopic Management of Early Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of The Esophagus - Screening, Diagnosis, and Therapy AGA 2018Document16 pagesEndoscopic Management of Early Adenocarcinoma and Squamous Cell Carcinoma of The Esophagus - Screening, Diagnosis, and Therapy AGA 2018Nishiby PhạmNo ratings yet

- Real-Life Chromoendoscopy For Neoplasia Detection and Characterisation in Long-Standing IBDDocument9 pagesReal-Life Chromoendoscopy For Neoplasia Detection and Characterisation in Long-Standing IBDdeniadillaNo ratings yet

- Ju 0000000000002756Document9 pagesJu 0000000000002756Laura SaldivarNo ratings yet

- Kidney StoneDocument3 pagesKidney StoneTaoreed AdegokeNo ratings yet

- Use of Endoscopic Assessment of Gastric Atrophy For Gastric Cancer Risk Stratification To Reduce The Need For Gastric MappingDocument7 pagesUse of Endoscopic Assessment of Gastric Atrophy For Gastric Cancer Risk Stratification To Reduce The Need For Gastric MappingVanessa BecerraNo ratings yet

- Diagnose of Stomach CancerDocument24 pagesDiagnose of Stomach CancerSameem MunirNo ratings yet

- Foregut Caustic Injuries: Results of The World Society of Emergency Surgery Consensus ConferenceDocument11 pagesForegut Caustic Injuries: Results of The World Society of Emergency Surgery Consensus ConferencemetaferosiaNo ratings yet

- RevisionLevel 3 SectionB MedSurge Case Study2Document113 pagesRevisionLevel 3 SectionB MedSurge Case Study2Milagros FloritaNo ratings yet

- 20 Breast Fact Sheet PDFDocument2 pages20 Breast Fact Sheet PDFRaghad Al NatshehNo ratings yet

- Indikasi EgdDocument3 pagesIndikasi EgdAhmad MirzaNo ratings yet

- Uworld GI NotesDocument17 pagesUworld GI NotesAyodeji SotimehinNo ratings yet

- Text A1: Causes and Types of GastritisDocument4 pagesText A1: Causes and Types of GastritisIrina AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Belgian Consensus For Helicobacter Pylori Management 2023Document18 pagesBelgian Consensus For Helicobacter Pylori Management 2023Pann EiNo ratings yet

- Ck7 Negative, Ck20 Positive Gastric Cancer: More Common Than You Might ThinkDocument2 pagesCk7 Negative, Ck20 Positive Gastric Cancer: More Common Than You Might ThinkAustin Publishing GroupNo ratings yet

- Nursing of Clients With Gastrointestinal DisordersDocument228 pagesNursing of Clients With Gastrointestinal DisordersLane Mae Magpatoc Noerrot100% (1)

- Guggenheim 2012Document7 pagesGuggenheim 2012Andreea PodaruNo ratings yet

- Molecular Nutrition Food Res - 2022 - Ao - Spicy Food and Chili Peppers and Multiple Health Outcomes Umbrella ReviewDocument11 pagesMolecular Nutrition Food Res - 2022 - Ao - Spicy Food and Chili Peppers and Multiple Health Outcomes Umbrella Reviewjifajot546No ratings yet

- Oncology Portfolio ChideraDocument9 pagesOncology Portfolio ChideraChidera Henry MaduekeNo ratings yet

- DR Pradeep Jain Fortis Hospital DelhiDocument21 pagesDR Pradeep Jain Fortis Hospital DelhiJessica RochaNo ratings yet

- Vonoprazan Tablets SMPCDocument24 pagesVonoprazan Tablets SMPCMoussa Amer100% (1)

- Natural Benefits of Urine Therapy by Jagdish R. BhuraniDocument60 pagesNatural Benefits of Urine Therapy by Jagdish R. BhuraniAlejandro Yolquiahuitl100% (7)

- 1.40 (Surgery) GIT Surgical Diseases - Diagnostics - Obesity ManagementDocument10 pages1.40 (Surgery) GIT Surgical Diseases - Diagnostics - Obesity ManagementLeo Mari Go LimNo ratings yet

- Quiz BukasDocument3 pagesQuiz BukasDYRAH GRACE COPAUSNo ratings yet

- Carcinoma GástricoDocument5 pagesCarcinoma GástricoNayeli Angelica Amaya SecundinoNo ratings yet

- GastricDocument6 pagesGastricapi-282129282No ratings yet

- Cardio and Hema Super SamplexDocument24 pagesCardio and Hema Super SamplexMj Lina TiamzonNo ratings yet

- Syrgery Mock 10Document8 pagesSyrgery Mock 10Sergiu CiobanuNo ratings yet

- GastroparesisDocument31 pagesGastroparesisGaby ZuritaNo ratings yet

- Print SGD Ein Fix Gastritis BHDocument21 pagesPrint SGD Ein Fix Gastritis BHSagita Wulan SariNo ratings yet

- All Conditions Data NCTDocument506 pagesAll Conditions Data NCTMuneer Ashraf0% (1)

- May 12, 2017 Strathmore TimesDocument32 pagesMay 12, 2017 Strathmore TimesStrathmore TimesNo ratings yet

- Diseases of The Gastrointestinal TractDocument87 pagesDiseases of The Gastrointestinal TractЛариса ТкачеваNo ratings yet

- 2024 Microbiology Hons Booklet - FINALDocument54 pages2024 Microbiology Hons Booklet - FINALchand198No ratings yet

- BaDocument22 pagesBaBehailu TejeNo ratings yet