Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jstor 1

Uploaded by

Pushp SharmaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jstor 1

Uploaded by

Pushp SharmaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Individual, Society, or Both?

A Comparison of Black, Latino, and White Beliefs

about the Causes of Poverty

Author(s): Matthew O. Hunt

Source: Social Forces , Sep., 1996, Vol. 75, No. 1 (Sep., 1996), pp. 293-322

Published by: Oxford University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2580766

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Oxford University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Social Forces

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Individual, Society, or Both?

A Comparison of Black, Latino, and White

Beliefs about the Causes of Poverty*

MATTHEW 0. HUNT, Indiana University

Abstract

In a sample of southern Californians, three questions were investigated: (1) Are there

race/ethnic differences in beliefs about the causes of poverty? (2) Do two social

psychological variables, namely internal and external self-explanations, signi.ficantly

affect beliefs about poverty net of respondents' background characteristics? and (3) Do

the determinants of beliefs about poverty differfor blacks, Latinos, and whites? Results

indicate that in each case the answer is yes. First, blacks and Latinos are more likely

than whites to view both individualistic and structuralist explanations for poverty as

important. Second, respondents' self-explanations have significant effects on poverty

beliefs. Lastly, the patterns of effects of several variables that predict beliefs about poverty

differ across race/ethnic groups. Results con.firm, contradict, and extend current

knowledge of beliefs about poverty.

Interest in the causes and consequences of beliefs about social inequality can be

traced to Marx's ([1859] 1970; Marx & Engels [1845] 1970) discussions of class

and consciousness. Building on this foundation, scholars have continued the

research tradition by investigating the determinants and consequences of

"beliefs about inequality," often noting the roles of ideology and consciousness

in the maintenance, stability, and reproduction of social stratification (Feagin

1975; Huber & Form 1973; Kluegel & Smith 1986; Robinson & Bell 1978). While

there is an extensive literature on the determinants and consequences of class

* A version of this article was the recipient of the American Sociological Association Social

Psychology Section's 1995 Graduate Student Paper Award and the Southern Sociological

Society's 1995 Howard W. Odum Award for outstanding graduate student paper. In addition,

it was presented at the 1994 American Sociological Association meetings in Los Angeles. The

research was supported by NIMH Grant PHS-T32 MH14588-18. The author wishes to thank

Sheldon Stryker and Richard Serpe for the opportunity to participate in the survey inves-

tigation producing the data used in this study. Thanks are also due to Sheldon Stryker, Robert

V. Robinson, John Pease, and Janet Hunt for their helpftul comments on earlier drafts of this

article. I am particularly indebted to Larry Hunt and Brian Powellfor their helpfiul suggestions

and careful assistance during several revisions of this article. Direct all correspondence to

Matthew Hunt, Department of Sociology, 744 Ballantine Hall, Indiana University,

Bloomington, IN 47405. E-mail: mohunt@indiana.edu.

i The University of North Carolina Press Social Forces, September 1996, 75(1):293-322

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

consciousness or identification (Centers 1949; Jackman & Jackman 1983;

Vanneman & Cannon 1987), comparatively little is known about the determi-

nants of other stratification beliefs such as explanations of why people are poor.

Past research into the determinants of such beliefs has neglected independent

variables other than objective social position (e.g., age, income, occupation).

Further, to the extent that we have knowledge of race/ethnic differences in

stratification beliefs, studies have virtually all focused on black/white differenc-

es.

This study advances this research tradition by investigating race/ethnic

differences in beliefs about poverty across three groups in American society:

African Americans, Latinos, and whites.' Further, in an attempt to map what

Mills (1959) calls the intersections of social structure and biography, I examine

the effects of two previously unexamined social psychological variables,

measuring internal and external explanations for personal positions, on beliefs

about poverty.

The dependent variables in this study represent stratification beliefs

involving individualistic and structuralist interpretations of why poverty exists

(Feagin 1972). I ask three basic questions: (1) Do race/ethnic differences exist

regarding what is believed about poverty? (2) Do social-psychological variables

affect poverty beliefs net of the effects of respondents' background characteris-

tics? and (3) Do the effects of sociodemographic and social-psychological

variables differ for blacks, Latinos, and whites?

Theoretical Background

BELIEFS ABOUT POVERTY

Feagin (1975) noted that beliefs about poverty are of three types: (1) individual-

istic - in which characteristics of persons are used to explain poverty,

(2) structuralist - in which the larger socioeconomic system is seen as the cause

of poverty, and (3) fatalistic - in which supra-individual, but non-social-

structural forces (e.g., luck, chance) are pointed to as the source of poverty. Past

studies document the greater popularity of individualistic views of poverty

among Americans (Feagin 1975; Huber & Form 1973; Kluegel & Smith 1986).

Public beliefs about the sources of poverty center on the lack of a proper work

ethic, the lack of ability, and other character defects of the poor themselves. In

short, the picture painted by these studies is one of perceived personal deficien-

cies of those who are poor - an image consistent with Ryan's (1971) claim that

Americans "blame the victim" when thinking about poverty.

Research into the antecedents of beliefs about poverty has generally found

that persons of higher status (e.g., those with higher incomes, whites, and older

people) favor individualistic explanations. Lower status has been found to

increase use of structuralist explanations, "but not necessarily with greatly

diminished support for individualism" (Kluegel & Smith 1986:93). The adher-

ence to individualism among lower status people is explained as evidence of the

strength of the dominant ideology, which is thought to be a general cultural

trait, having broad, universalistic effects on all Americans. In contrast to the

stable effects of individualism, structuralist beliefs are more variable, more

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 295

responsive to group memberships, personal experiences, and the prevailing

social climate, and layered onto, instead of replacing, the existing individualistic

base. Kluegel and Smith (1986) suggest that during times of extreme social or

economic strain, structuralist beliefs may actually predominate in public

opinion. Supporting this position is Piven and Cloward's (1971) observation that

during the Great Depression, structuralist beliefs, in the form of support for the

redistribution of wealth and other social welfare initiatives, dominated

Americans' beliefs about the causes of unemployment, inequality, and other

social ills.

QUESIION 1: DO RACF( ETHNIC DIFFERENCES EXIST?

An example of a group in which structuralist beliefs generally predominate is

African Americans. Research on race has shown that blacks are generally equal

to or slightly less individualistic than whites, but much more likely to view

structural factors as contributing to the existence of poverty (Feagin 1975;

Kluegel & Smith 1986). By comparison, little is currently known about Latino

beliefs about poverty. The pattern among blacks of greater structuralism, along

with levels of individualism similar to that of whites, supports the argument

that structuralist beliefs may be combined with, or layered on to, an existing

individualistic base. Following this reasoning and past research, I expect that

race/ethnic minorities, compared with whites, will exhibit more structuralist outlooks,

but will not differ significantly in individualistic outlooks.

The argument that individualistic and structuralist beliefs may be combined

contrasts with the assumption of earlier research that people take an either-or

approach to thinking about inequality. In past research, ideologies, value

systems, and belief systems were assumed to exist in opposing pairs - e.g.,

right versus left, individualism versus structuralism - apparently reflecting a

basic cognitive tendency.2 Recent research shows that these dichotomies are not

always warranted since seemingly inconsistent or contradictory beliefs can be

combined into compromise explanations (Kluegel & Smith 1986; Lee, Jones &

Lewis 1990).3 For example, with regard to beliefs about poverty, people may

combine an acknowledgment that structural barriers exist in society with the

belief that anyone who works hard enough can overcome such barriers. Mann

(1970) links this image of value inconsistency to the stability of stratified social

orders in arguing that, rather than resting on a consensus over basic system-

legitimating values such as individualism, the social cohesion of liberal

democracies rests on the lack of a consensus on system-challenging values -

particularly among the working class and oppressed minority groups. For

Mann, societal stability and the lack of acute group-based conflict are rooted in

the inconsistency of the belief systems (e.g., some individualistic and system-

challenging beliefs) of potentially recalcitrant groups.

Bobo (1991) reaches a similar conclusion as Mann regarding the duality of

the beliefs of relatively low-status groups in arguing for the existence of an

egalitarian and structuralist "social responsibility" outlook in American culture

that oppressed groups are especially likely to draw upon to counter economic

individualism. Bobo interprets his finding of a potent social responsibility belief,

existing alongside individualism among the American public, as support for

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

Mann's inconsistency argument and critique of consensus theories (Bobo

1991:87). More specifically, Bobo argues against what he characterizes as the

"consensus on individualism" position of most accounts of American public

opinion (which treat individualism as a true dominant ideology). He argues that

individualism retains its appearance as a hegemonic value in the larger society

not because of the lack of alternatives, but rather because of the lack of political

influence and low status of persons most committed to egalitarian beliefs.

Evidence of simultaneous adherence to both types of poverty explanation will

be interpreted as support for the view that these beliefs are not ideological

alternatives and may be combined in a form of dual consciousness. Following

the reasoning of Bobo (1991) and Mann (1970), I expect that this dual conscious-

ness will be more prevalent among disadvantaged groups such as racial/ethnic

minorities.

Because research into race/ethnic differences in beliefs about poverty is

limited, the literature on social welfare beliefs suggests some additional lines of

reasoning. While beliefs about poverty and beliefs about welfare are clearly not

identical, correlations found in past research between structuralist beliefs about

poverty and support for social welfare, and between individualistic beliefs about

poverty and opposition to welfare (Feagin 1975; Kluegel & Smith 1986) suggest

sufficient similarity exists between the two issues to reason from one to the

other. Research into race differences in support for social welfare has found that

whites are typically opposed to social welfare programs, particularly those

aimed at reducing inequality (Bobo 1988; Jackman & Muha 1984). Blacks, and to

a lesser extent Latinos, are more supportive of social welfare initiatives

(Steelman & Powell 1993:225).

There are two competing explanations for racial/ethnic minorities' stronger

structuralist outlook (and support for welfare). The first is that beliefs about

poverty follow from economic self-interest: Individuals in groups that are

disproportionately poor - such as racial minorities, women, younger persons

- tend to hold structuralist beliefs. The key to this self-interest explanation is

that structuralist beliefs are correlated with socioeconomic status (SES).

Following this logic, race/ethnic differences should mirror SES differences in

support for structuralist outlooks. Evidence for the self-interest argument is

mixed to negative as indicated by studies that find income to be a weak

predictor of social welfare support (Form & Hanson 1985; Hasenfeld & Raffe

1989). Further, to the extent that education represents a component of socioeco-

nomic status, following the logic of the self-interest argument, one would expect

an inverse relationship between education and structuralist outlooks. Research

has generally shown the opposite, moving some to argue for an enlightening

effect of education that increases awareness of inequality and compassion

toward the disadvantaged (Hyman & Wright 1979).

The second explanation for race differences in stratification beliefs holds that

individuals identify with the generalized experiences of the groups to which they

belong and respond in line with these group identifications. Following this

logic, minorities - regardless of whether they have experienced difficulties

directly - will tend to identify with the struggles of their fellow group

members (Gurin, Miller & Gurin 1980; Steele 1994). This group identification

model suggests that structuralist outlooks are determined by an individual's

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 297

perception of the general condition of his or her group rather than his or her

own SES. Schuman, Steeh, and Bobo (1985) find support for this argument in

strong black support for social welfare initiatives when controlling for SES,

suggesting that such support is better explained by racial collective experience

than individual socioeconomic standing. In interpreting the relationship between

race and SES on beliefs about poverty, if race/ethnic differences in attitudes are

reduced significantly when controlling for SES, the self-interest perspective will gain

support. In contrast, if race/ethnic differences persist following the introduction of SES

controls, the group identification explanation will be supported.5

QUESnION 2: DO SOCIAL PSYCHOLOGICAL VARIABLES MATI`ER?

To move beyond previous research, I also consider two social-psychological

independent variables. These variables measure respondents' "internal" and

"external" explanations (i.e., attributions) for their personal outcomes in the

domains of work and education. For Mills (1959), the essence of the sociological

imagination lies in explicating the intersections between biography and social

structure, or, from a symbolic interactionist standpoint, "self and society"

(Stryker 1980). For Mills, social structural effects take on more depth and

relevance when viewed in conjunction with effects registered at the level of

identity. Similarly, symbolic interactionist theorizing in sociology stresses the

importance of the self-concept as a mediating force between social structure and

beliefs or behavior. Building on the structural symbolic interactionist (Stryker

1980) premise that social structure shapes selves, one way of tapping variation

in peoples' experiences and perceptions of the larger society is through an

examination of explanations that people use in making sense of their personal

biographies.

Past research (e.g., the attribution tradition) suggests that it is useful to

differentiate people according to whether they use vocabularies that contain

intemal or extemal reference points.6 Research documents that Americans favor

"dominant ideology" internal self-explanations; those in higher status positions

are especially likely to favor intemal explanations (Kluegel & Smith 1986), and

such personal beliefs shape ideological beliefs about issues related to equality

and inequality. For example, attribution research shows that, net of socio-

demographic factors, beliefs about economic outcomes are significantly affected

by intemal and extemal self-orientations (Bains 1983; Weiner 1974). Further,

Kluegel and Smith (1986) argue that people tend to generalize in limited but

consistent ways from their personal explanations to their explanations for

poverty and other societal-level phenomena (e.g., wealth). For example,

reporting ability and effort (i.e., "intemal" attributions) as primary reasons for

one's own current standard of living tends to increase beliefs in individualism,

while invoking "bad luck, being helped or held back by other people, or the

circumstances of the job a person holds" (i.e., "external" attributions) for one's

own outcomes increases beliefs in structural causes of poverty (Kluegel & Smith

1986:81-85). Similarly, Heaven (1989) reports that, net of one's background

characteristics, internal self-explanations lead to individualistic beliefs about

poverty, while extemal self-explanations lead to structuralist beliefs.

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

In line with this research tradition, I investigate whether self-explanations

referring to properties internal to self, and to properties of the larger, supra-

individual, external environment, shape people's beliefs about the im,portance of

individualistic and structuralist factors in the genesis of poverty. Given the

findings of attributional consistency in past research, I expect that internal self-

explanations will lead to individualistic poverty beliefs, while external self-explanations

uwill lead to structuralist outlooks.8

QUESIION 3: DO THE INDEPENDENT VARIABLES OPERATE DIFFERENTLY FOR THE THREE

RACF ETHNIC GROUPS?

Much social psychological research makes the implicit assumption that the

determinants of attitudes and beliefs are the same across large-scale social

categories such as race and ethnicity. In short, it is generally assumed that the

determinants of a belief among the race/ethnic subgroups that make up a

sample are the same as among the total sample. As a consequence of this

assumption of similarity, the hypothesis that the beliefs and attitudes of

understudied (i.e., nonwhite) race/ethnic groups might be influenced in

different ways by various structural and social psychological factors has gone

largely untested.9 I test this hypothesis, guided by the assumption that groups

with widely different experiences and conditions of existence may differ in how

particular variables affect ideological beliefs. The historical oppression and

continued segregation (Massey & Denton 1992) of blacks is an obvious source

of group distinction. At a more social-psychological level, Steele (1994) argues

that even successful blacks, who are on a par with middle-class whites from the

standpoint of socioeconomic status, stili must cope with knowledge of the

historical reality of race-based discrimination, as weli as the continuing

perception of racism as a force influencing self and feliow group members, in

forming an ideological orientation toward American society.-l The relatively

recent migration of many Latinos to southern California from Central and South

America (Donato 1994) may differentiate them from most blacks and non-Latino

whites in the region. These factors alone make it clear that blacks and Latinos

have distinct experiences and histories that may have implications for how

members of these groups perceive themselves, other groups, and American

society.

A final factor contributing to the origin and perpetuation of the assumption

of race/ethnic similarity has been the insufficient numbers of minority respon-

dents in past surveys for the type of statistical analyses needed to compare the

determinants of dependent variables such as beliefs about poverty. In contrast

to past research, the data base used in this study contains sizable subsamples of

blacks and Latinos, aliowing for statistical subgroup comparisons that directly

examine the validity of the assumption of similarity.

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 299

Data and Measures

DATA

The data for this study derive from a computer-assisted telephone sample

survey of five counties (Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino, and

San Diego) in southern California, conducted between January and March 1993.

The survey used the Waksberg (1978) method of random-digit dialing and

covered all working exchanges in the five counties under examination. The

response rate was just above 70% and 2,854 interviews were completed. The

race breakdown was 1,245 whites, 737 Latinos, 646 blacks, 148 Asians, and 62

"others" (16 people refused to answer the race self-identification question).

Given the extreme cultural heterogeneity of the Asian category (which includes

Japanese, Chinese, Koreans, Vietnamese, and others), I elected to exclude Asians

from the study in order to focus on a comparison of the three major race/ethnic

groups (N - 2,628). The survey purposely oversampled blacks, resulting in a

sample in which whites represent 47.4% of respondents, blacks represent 24.6%

of respondents, and Latinos represent 28% of respondents."1 A weighting

correction adjusts the sample to mirror existing race/ethnicity and gender

population proportions according to 1990 census information. This procedure

changes the race/ethnic percentages to whites = 60.2%, blacks = 8.7%, and

Latinos = 31.1%. I use the weighted sample for the calculation of the frequen-

cies, variable means, and standard deviations, which appear in Tables 1 and 2.

Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish according to the language the

respondent preferred. A complex translation, back-translation technique was

used to ensure the linguistic equivalence of the survey instrument in English

and Spanish.12

Belief Measures

STRATIMCATION BELIEFS

The two dependent variables measure the importance attributed to individua

tic and structuralist reasons for poverty. The items used in these measures we

adapted from Feagin's (1972) 1969 survey study of poverty beliefs and appear

in the Appendix. A principal components factor analysis (varimax rotation)

performed on these items reveals two underlying dimensions that are interpret-

ed as individualistic and structuralist reasons for poverty (results in Table 1).

Identical factor analyses performed with each race/ethnic subgroup revealed the

same two underlying dimensions. The two dependent variables are standard-

ized summed scales rather than factor-score scales.'3

The individualism scale (am .674) is composed of the following items:

"personal irresponsibility, lack of discipline among those who are poor," "lack

of effort by those who are poor," "lack of thrift and personal money manage-

ment," and "lack of ability and talent among those who are poor." The

structuralism scale (a = .697) includes "low wages in some businesses and

industries," "failure of society to provide good schools for many Americans,"

"prejudice and discrimination," and "failure of private industry to provide

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

enough good jobs." Respondents were asked whether they thought that each

reason was "very important" (coded 4), "somewhat important" (3), "not very

important" (2), or "not at all important" (1), as a reason for poverty.

SELF-EXPLANATIONS

Intemal and extemal self-explanations are measured with standardized,

summed scales composed of four items each. Respondents were asked to rate

the importance of ability, effort, opportunities, and luck in determining their

success in education and work. The intemal scale (a =.551) was constructed by

combining the two ability and two effort attribution items. The external scale

(a -.647) was constructed by combining two opportunities and the two luck

attribution items. The interviewer's statement on education was "Now we

would like you to think about your education. Think about the highest degree

you have earned. Please indicate how important the following were in deter-

mining your educational success: How important would you say your abilities,

things like talents, intelligence, and skills, were in determining your educational

success? How important would you say your opportunities, things like your

family background and other life circumstances, were in determining your

educational success? How important would you say your effort, things like

desire, dedication, and motivation, were in determining your educational

success? How important was luck, that is, fate or chance, in determining your

educational success?" Response options were the same as for the dependent

variables (very important = 4, range = 14). Readers interested in the slig

wording differences for work items, as well as the measurement of respondents'

sociodemographic characteristics (which followed standard procedures), are

directed to the Appendix.

Findings

BELIEFS ABOUT POVERTY: A SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA SIRUCTURALISM?

Before explicitly examining race/ethnic differences, I discuss some unexpected

findings that warrant brief comment. Table 1 reports a comparison of responses

to the ten items originally examined by Feagin (1972) in a 1969 study, replicated

by Kluegel and Smith (1986) in their 1980 stratification beliefs survey, and

employed here.14 The results of the two earlier national studies reveal the

greater popularity of individualistic items, compared with structuralist items,

with individualistic items constituting four of the five most likely to be labeled

very important. In the Kluegel and Smith data, the average proportion

responding "very important" across individualistic items is 50%, while for

structuralist items it is 34%. The picture is clear in the previous research:

Americans favor individualistic beliefs about poverty.

Analysis of the 1993 southern California data shows a markedly different

picture - specifically, a stronger popularity of structuralist reasons than would

be expected from previous studies of the U.S. as a whole. The 1993 data show

an average proportion responding "very important" across structuralist reason

is 52%, while for individualistic reasons the average is 42%. Further, four of the

five most popular items in 1993 are structuralist (the top four all structuralist).

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 301

Analysis of the marginals by race/ethnic subgroup reveals that, even among

whites, three of the five most popular reasons are structuralist (the top two

structuralist). Blacks and Latinos are similar in their responses, with four

structuralist reasons in the five most commonly rated "very important."

One possible explanation of these unexpected findings is that southern

Californians have always been more structuralist than the rest of the country,

and this anomaly has been masked by the weaker structuralism of other regions

in national studies. Doubts about the stability over time of a relatively strong

southern California structuralism are raised, however, when one examines

Kluegel and Smith's (1986) analysis of the impact of region on the two poverty

beliefs under examination. They report that the West region, controlling for

Midwest and South, with East as the omitted category, is significantly less

structuralist on the subject of poverty.

Following Kluegel and Smith (1986), who suggest that structuralist beliefs

should come to the fore in response to events that heighten awareness of

inequality and structural problems, the more probable source of the greater

structuralist support across major race/ethnic lines is the recent social climate

and events of the region under examination. Given the severe economic

recession in the region, crises in California's educational system, the Rodney

King incident - in which several white police officers were acquitted of beating

a black motorist - and the most recent riots in Los Angeles, it is perhaps not

surprising that survey items referring to the lack of adequate schooling,

prejudice, discrimination, and other system-blaming factors were especially

salient to southem Californians.

QUESTION 1: ARE THERE RACE/ EITHNIC DIFFERENCES IN BELIEFS ABOUT POVERTY?

Despite the consensus on the importance of structuralist reasons for poverty

seen across all three race/ethnic groups, some significant race/ethnic differences

do exist. Table 2 presents means on all variables appearing in subsequent

analyses and comparisons by race/ethnicity. Perhaps surprisingly, Latinos rank

highest on individualism followed by blacks and whites in that order. On the

structuralism scale, both minority groups show a similar mean (not significantly

different from each other) and both are significantly more structuralist in their

beliefs than whites. Thus, it appears that both minority groups, compared with

whites, are more likely to invoke both poverty explanations. Further, examina-

tion of the zero-order correlations between the two dependent variables lends

additional support to the view that these beliefs are not ideological alternatives

(especially for minorities) and may be combined in a dual consciousness. For

the whole sample, the correlation is .202 (p < .001); for whites r = -.013 (not

significant at p < .05); for blacks r = .298 (p < .001); and for Latinos r = .401

(p < .001).15

To explore the descriptive finding that blacks and Latinos are more likely to

endorse both individual and structural reasons for poverty in comparison with

whites, I turn to a series of multiple regression analyses. These analyses

examine whether the pattern of race/ethnic differences in the dependent

variables, suggesting greater dual consciousness among minorities, is stable

when controlling for other ways in which the groups differ.'6

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

302 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

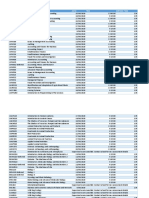

TABLE 1: Reasons for Poverty: Marginals in 1969, 1980, and 1993a

1969 Data 1980 Data

(Percent) (Percent)

Very Important Not Very Important Not

Important Important Important Important

Reason

Lack of thrift and proper

money management 59 31 11 64 30 6

Lack of effort by

the poor themselves 57 34 9 53 39 8

Lack of ability and talent 54 34 12 53 35 11

Personal irresponsibility,

lack of discipline among

those who are poortt 50 32 18 44 30 27

Sickness and physical

handicaps 46 39 14 43 41 15

Low wages in some

businesses and industries 43 36 21 40 47 14

Failure of society

to provide good schools

for many Americans 38 26 36 46 29 26

Failure of private

industry to provide

enough good jobs 29 38 33 35 39 28

Prejudice and

discriminationtt 34 39 27 31 44 25

Just bad luck 8 28 63 12 32 56

Table 3 shows the regression of each dependent variable on three sets of

independent variables, run in hierarchical fashion. Model 1 includes only

race/ethnicity dummy variables. Model 2 includes only other sociodemographic

variables (sex, income, education, age). Model 3 combines the independent

variables from the first two models. Model 1 regressions reiterate the previously

observed pattern of blacks and Latinos attributing more importance to both

explanations of poverty. Thus, the prediction that race/ethnic minorities would

be more structuralist, but not significantly different on individualism in

comparison with whites, is not supported.17 Further, the equations composing

model 3 lend support to the group identification explanation of race/ethnic

differences in stratification beliefs, since the effects of the race/ethnicity dummy

variables remain significant after the introduction of SES statistical controls. The

group identification explanation of structuralist beliefs is complicated, however,

by the simultaneous greater levels of support found for individualistic thinking.

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 303

TABLE 1: Reasons for Poverty: Marginals in 1969, 1980, and 1993a (Continued)

1993 Data Factor

(Percent) Loadings

[Present study]

Very Important Not Structural Individual

Important Importantt

Reason

Lack of thrift and proper

money management 45 (5)t 43 13 .14 .63

Lack of effort by

the poor themselves 40 (8) 42 18 -.01 .78

Lack of ability and talent 38 (9) 37 25 .24 .60

Personal irresponsibility,

lack of discipline among

those who are poortt 45 (6) 38 17 -.04 .78

Sickness and physical

handicaps 40 (7) 40 20 .45 .38

Low wages in some

businesses and industries 48 (3) 39 13 .74 .07

Failure of society

to provide good schools

for many Americans 62 (1) 26 14 .70 -.00

Failure of private

industry to provide

enough good jobs 48 (4) 37 15 .69 .14

Prejudice and

discrimination4t 49 (2) 36 14 .70 .03

Just bad luck 12 (10) 32 56 .26 .22

a Weighted sample and factor analysis

percentage of respondents saying "very important" in the 1969 data.

t "Not very important" and "Not at all important" response categories have been collapsed

to " Not important."

* The rank ordering of "very important" responses for the 1993 sample is given in

parentheses.

tt This item read "loose morals and drunkenness" in the two earlier studies.

# This item included "against blacks" in 1980 and "against Negroes" in 1969.

This dual consciousness pattern resonates with the arguments of Bobo (1991)

and Mann (1970) as well as with Kluegel and Smith's (1986) assertion that

blacks demonstrate the strongest group consciousness in their support for

structural challenges to the dominant ideology but "stop short of denying the

justice of economic inequality in principle and of dismissing the ideas that the

rich and poor as individuals are deserving of their fate" (290). While past

research has found blacks to be slightly less than or just as individualistic as

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

304 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

TABLE 3: Unstandardized QIS Results of Stratification Beliefs Dependent

Variables Regressed on Three Models Composed of Race and

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Dependent Variables

Model 1 Model 2 Model 3

Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc.

Independent variables

Latino .354*** .418*** .208*** .339***

(.030) (.027) (.035) (.032)

Black .190*** 381*** .116*** .346*

(.032) (.028) (.031) (.028)

Sex (female - 1) -.014 .125* -.011 .125***

(.026) (.024) (.026) (.023)

Income -.017** -.034* -.010 -.020***

(.006) (.006) (.026) (.006)

Education (years) -.046*** -.020*** -.037*** -.008*

(.004) (.004) (.004) (.004)

Age (years) .002 -.003* .002** -.001

(.001) (.001) (.001) (.001)

R2 .06 .13 .09 .08 .11 .16

N 2,082 2,107 2,082 2,107 2,082 2,107

a Standard errors appear in parentheses u

* p <.05 ** p <.01 *** p < .001

whites, the current findings show that blacks (and Latinos) may surpass the

individualism of whites, even while exhibiting the greater levels of structural

thinking about inequality.

Finally, the effects of several of the sociodemographic variables included in

model 3, and used in past research on beliefs about poverty, warrant brief com-

ment. Consistent with an underdog perspective (Robinson & Bell 1978), which

predicts that relatively disadvantaged groups (e.g., those with low incomes,

women) will favor beliefs that challenge the dominant ideology: women are

more likely than men to see structuralist reasons for poverty as important, and

a lower household income increases the likelihood that structuralist beliefs will

be invoked. Having more education reduces the likelihood of seeing either type

of poverty belief as important. The negative impact of education on

individualism supports an enlightenment perspective, while the negative effect

on structuralism supports perspectives (e.g., the underdog viewpoint) that

emphasize the role of education as a component of socioeconomic status. Finally,

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 305

consistent with past research, older respondents in model 3 are more likely to

be individualistic on the subject of poverty.

In sum, the models composing Table 3 demonstrate that there are significant

race/ethnic differences in beliefs about poverty.

QUESTION 2: DO THE SOCIAL-PSYCHOLOGICAL VARIABLES AFFECT BELIEFS ABOUT

POVERTY?

Table 4 recreates all regressions from Table 3 and adds the internal and external

self-explanation variables in an effort to incorporate the self-concept into our

understanding of how beliefs about poverty are shaped. Across the six

equations in Table 4, the race/ethnicity and sociodemographic findings are

largely consistent with those reported previously. (Exceptions are that, in model

6, the age variable does not show the previously observed significant effect on

individualism and the education variable does not show the previously

observed significant effect on structuralism.)18 The self-explanation effect

consistent across all three models. Contrary to prediction, respondents in the

complete sample do not generalize neatly from self-explanations to beliefs about

poverty: internal self-explanations do not lead solely to individualistic thinking

about poverty, nor do external self-explanations lead solely to the invocation of

only structuralist reasons for poverty. While these patterns seem to show that

both internal and external self-explanations significantly increase both individu-

alistic and structuralist thinking about poverty, further analyses reveal that the

effect results from two distinct patterns, corresponding with whites and

nonwhites, that are superimposed in Table 4.

Nonetheless, Table 4 provides an affirmative answer to the second main

question of this study: social-psychological variables do have significant effects

on beliefs about poverty net of respondents' background characteristics. In an

effort to further deconstruct the findings reported in Table 4, I reran models

within race/ethnic subgroups to explore how blacks, Latinos, and whites may

contribute differently to the patterns reported for the whole sample.

QUESTION 3: DO RACE/ETHNIC GROUPS DIFFER IN THE DETERMINANTS OF BELIEFS

ABOUT POVERTY?

Table 5 represents the final set of analyses, which directly test the assumption

of similarity concerning the determinants of poverty beliefs for the three

race/ethnic groups. To address this third main question of the study, the

equations with only sociodemographic variables (model 2) and equations with

both sociodemographic and the self-explanation variables (model 5) were run

again within the three separate race/ethnic subsamples. These analyses further

specify links between race, the self, and ideological beliefs, or in Mills's (1959)

language, some ideological consequences of the intersections of social structure

and biography. The significance of race/ethnic group differences in the

regression coefficients for each independent variable (from the equations run

separately within each subgroup) is assessed using a difference-of-slope test.

This test is comparable to testing the significance of the interaction term of the

independent variable with race/ethnicity (Kmenta 1971).

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

306 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

TABLE 4: Unstandardized OLS Results of Stratification Beliefs Dependent

Variablesa

Model 4 Model 5 Model 6

Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc.

Independent variables

Latino .326*** .335*** .209*** .293***

(.039) (.035) (.044) (.039)

Black .212*** .363*** .194*** .334***

(.039) (.035) (.039) (.035)

Sex (female - 1) .004 .140*** -.001 .129***

(.031) (.029) (.031) (.028)

Income -.014 -.030*** -.006 -.019*

(.008) (.008) (.008) (.008)

Education (years) -.042*** -.011* -.035*** -.003

(.005) (.005) (.006) (.005)

Age (years) .001 -.003* .002 -.001

(.001) (.001) (.001) (.001)

Internal .159*** .088* .203*** .125** .184*** .097**

(.042) (.037) (.042) (.039) (.042) (.037)

External .137*** .146*** .124*** .167*** .101*** .134***

(.023) (.021) (.023) (.022) (.024) (.021)

.13 .17 .13 .13 .15 .19

N 1,355 1,362 1,355 1,362 1,355 1,362

a Regressed on three models composed of race,

explanations. Standard errors are in parentheses.

* p <.05 **p < .01 *** p < .001

Among whites, the sociodemographic variables composing model 2 show

several of the same effects seen among the whole sample, in which several

variables significantly affect poverty beliefs. Specifically, among whites, women

are more likely than are men to endorse structuralist beliefs, greater income

decreases adherence to structuralist beliefs, and more education reduces the

likelihood of viewing individualistic beliefs about poverty as being important.

Among blacks, having more income decreases individualistic beliefs about

poverty, an effect not seen among other groups or in past research. For Latinos,

as with whites, having more education decreases individualistic thinking, which

is consistent with the enlightenment interpretation of education effects. While

more significant effects are observed among whites than the minority groups,

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 307

TABLE 5: Unstandardized OLS Results of Separate Regressions of Models 2 and

5 for Each Stratification Beliefs Dependent Variable within Race

Subgroupsa

Whites

Model 2 Model 5

Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc.

Independent variables

Female .018 .179***c -.002 .167***

(.046) (.046) (.046) (.045)

Income 015b -.026* .016b -.023

(.012) (.012) (.012) (.012)

Education .046***b --005 .049***b,c .004

(.009) (.009) (.009) (.009)

Age .003 -.001 .002 -.001

(.002) (.002) (.002) (.002)

Internal .245***c -.014b,c

(.064) (.061)

External .007b'c 206***bc

(.036) (.036)

R 2 .04 .04 .06 .08

N 663 665 663 665

a~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

a Standard errors are in parentheses.

b Differences between slopes for whites and blacks are significant at p < .05.

c Differences between slopes for whites and Latinos are significant at p < .05.

d Differences between slopes for blacks and Latinos are significant at p < .05.

* p <.05 ** p <.01 *** p < .001

the difference-of-slope test reveals that none of these effects is significantly

stronger for whites than for both blacks and Latinos. Instead, a mixed picture

emerges when examining the significance of across-group comparisons of the

effects of particular independent variables: specifically, education is a stronger

predictor of individualism for whites and Latinos than for blacks, income is a

stronger (negative) predictor of individualism for blacks than either whites or

Latinos, and being female is a stronger predictor of structuralism for whites

than for Latinos (in model 2).

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

308 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

TABLE 5: Unstandardized OLS Results of Separate Regressions of Models 2 and

5 for Each Stratification Beliefs Dependent Variable within Race

Subgroupsa (Continued)

Blacks

Model 2 Model 5

Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc.

Independent variables

Female -.011 .097 -.018 .091

(.071) (.053) (.070) (.052)

Income 053**b,d -.017 _.047*bd -.015

(.019) (.014) (.018) (.014)

Education _.011 d .002 -.010b .001

(.014) (.010) (.014) (.010)

Age .004 -.002 .003 -.003

(.003) (.002) (.003) (.002)

Internal .167 .218***b

(.085) (.063)

External .155**b .056b

(.048) (.035)

R2 .04 .02 .09 .07

N 317 318 317 318

a Standard errors are i

b Differences between s

c Differences between

Differences between sl

* p <.05 ** p <.01

The regression equations that include sociodemographic and self-explana-

tion independent variables (model 5) reveal an increase in predictive power,

along with the same patterns for the sociodemographic variables found when

the more restricted equations (model 2) are run within each race/ethnic group.19

Analysis of the self-explanation effects within each race/ethnic subgroup reveals

an interesting contrast between whites and race/ethnic minorities not observ-

able in the analyses reported for the whole sample (Table 4). Contrary to the

mixed picture seen for the significance of white-versus-minority differences in

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 309

TABLE 5: Unstandardized OLS Results of Separate Regressions of Models 2 and

5 for Each Stratification Beliefs Dependent Variable within Race

Subgroups (Continued)

Latinos

Model 2 Model 5

Indiv. Struc. Indiv. Struc.

Independent variables

Female .004 .085c .027 .090*

(.054) (.046) (.051) (.044)

Income -.017d -.018 003d -.011

(.017) (.014) (.016) (.014)

Education 040***d -.013 -.025**c -.007

(.008) (.007) (.008) (.007)

Age -.000 .000 -.002 -.002

(.003) (.002) (.003) (.002)

Internal .045c .188**c

(.071) (.062)

External .226***C Q90*c

(.041) (.036)

R 2 .10 .03 .18 .09

N 375 379 375 379

a Standard errors are in

b Differences between s

c Differences between s

d Differences between

* p <.05 ** p <.01 *** p < .001

the impact of the sociodemographic variables, a clear and significant white-

versus-minority pattern emerges for the effects of the self-explanations.

For whites, internal self-explanations increase the likelihood that individual-

istic reasons are seen as important causes of poverty, while external self-

explanations increase the likelihood that structuralist reasons are viewed as

important. The effects of internal self-explanations on thinking structurally and

external self-explanations on thinking individualistically are not significant for

whites. Thus, whites tend to think about the situations of self and others in

similar, consistent ways - a pattern that conforms with past research and with

the predicted pattern not observed in the whole sample. Internal self-explana-

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

310 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

tions, a component of the dominant ideology, lead to holding individuals

primarily responsible for being poor. External self-explanations, a stance at odds

with dominant modes of explaining personal success, increase the likelihood of

perceiving structuralist reasons as important in producing poverty. In short, the

system is interpreted in universalistic terms; specifically, all people are thought

to experience the world similarly.20 When whites say "I made it because of me,"

they tend to view the society as an open system in which people have similar

chances, personal responsibility is the rule applied to everyone, and poverty

gets explained in the terms of internal/individual-level factors. Similarly, when

whites believe they have been held back by outside, external forces, following

universalistic norms they also assume that similar supra-individual barriers in

society must exist for others (e.g., the poor).

For blacks and Latinos, the general relationshi between self-explanations

and beliefs about poverty is dramatically different. Specifically, for minorities,

internal self-explanations significantly increase the likelihood of seeing struc-

turalist (but not individualistic) reasons for poverty as important, while external

self-explanations significantly increase individualistic (but not structuralist)

thinking on the subject of poverty. These patterns suggest that there is some-

thing about the minority experience that shapes the relationship between

explanations for self and others' situations in a different way than among

whites. One possibility is that minority experience is conditioned by the facts of

both class and caste.

Steele (1994) highlights the central role of race/ethnic status in the forma-

tion of minority-group consciousness, noting the way in which race/ethnic

group membership and social class/personal success exert conflicting pressures

on the opinions, beliefs, and values of many blacks.22 Given that the respon-

dents in the models that include self-explanations are all employed, consider-

ation of the general societal position of employed minorities reveals possible

sources of the unique minority patterns observed. For Steele, the personal

success and social class position of gainfully employed blacks reinforce norms

of hard work, individual effort, and a sense of distinctiveness relative to those

in poverty. In short, success for minorities enhances the basic legitimacy of the

system and the tendency to view it in a class-based way that assumes that

universalistic chances for mobility exist. At the same time, competing with these

forces is the powerful effect of race/ethnicity, serving as a constant reminder of

the importance of the castelike nature of social placement of race/ethnic

minorities and the existence of structural barriers in society. In short, the

minority experience combines the realities of class and caste, which complicates

consciousness - undercutting the use of universalistic norms and the possibility

of psychological consistency - by reinforcing the reality of ascribed status and

the particularistic experiences of nonwhite groups in America.

Following this logic, employed minorities in this study can be thought of as

occupying a distinct structural position in the middle of the American success

pie: they are better off than the abject poor but still relatively disadvantaged

compared with middle-class whites. Using symbolic interactionism's conceptual-

ization of the self as a multidimensional phenomenon whose structure reflects

the larger society, one's social group memiberships, and one's personal experi-

ences, the self-concept of employed blacks and Latinos likely reflects their

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 311

general structural position, which provides two basic reference groups: one that

highlights their relative success and the importance of beliefs in internal,

individual sources of advancement, and a second that highlights minorities'

relative disadvantage and the continuing significance of external, environmental

barriers to equality with whites. From a symbolic interactionist perspective these

self-explanations can be understood to represent two distinct components of

identity, or "vocabularies of motive" (rather than different poles of a single

continuum as the locus-of-control concept assumes), which may have a different

salience for different respondents (from different experiences of the world), as

well as different levels of salience within the selves of particular respondents.

For minorities, the salience of internal self-explanations leads to the

increased adoption of structuralist beliefs as a response to personal struggles in

a caste-conditioned system. Internal self-explanations are made salient from a

sense of having worked hard and having made sacrifices to achieve personal

success and the status that gainful employment brings. However, unlike whites,

who operate with a view of the stratification system that causes them to

generalize (in universalistic fashion) from personal experiences to the poor,

employed minorities' beliefs are more complex and are shaped by the compet-

ing pull of the castelike reality of race/ethnic status. Thus, even when the

dominant ideology internal terms are salient in explaining one's own biography,

minorities also contend with a sense of having had to overcome structural

barriers to achieve their success, while acknowledging that similar barriers exist

for other members of one's group. The internal self-orientation does not

dominate consciousness but remains one component of a dual consciousness

characteristic of minority groups. In short, the intemal attribution of responsibil-

ity is fully compatible with more structural modes of thinking that place some

responsibility outside the individual realm. This finding is consistent with

Steelman and Powell's (1993) finding that among African Americans, support

for government funding of higher education (interpreted as a form of social

welfare) is fully consistent with a sense of personal responsibility among parents

for funding their children's education. For blacks and Latinos, assuming

personal responsibility, or saying "I made it because of me," does not preclude

- indeed it can increase - the acknowledgment that structural barriers exist in

society.

The pattern of external self-explanations leading to individualistic beliefs

about poverty among minorities is understood with a similar dual-consciousness

logic, supplemented by theories of cognitive attribution biases (Nisbett & Ross

1980; Ross 1977). Studies of ego-defensive or self-serving attribution biases

suggest that external self-explanations are commonly adopted by vulnerable

persons to deflect responsibility for personal outcomes away from the self and

toward the larger environment23 Studies also suggest that working Americans'

views of the poor are shaped by such ego-defensive tendencies. Lewis (1978)

argues that the projection of personal responsibility for failure onto the poor

allows certain vulnerable strata to feel better about their own limited successes.

Lane (1962) makes a similar point in arguing that many working Americans

exhibit a fear of equality, since living close to poverty (in the sense of limited

income, limited resources, the threat of falling into poverty) produces a need for

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

312 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

greater psychological distance from the poor in order to maintain a favorable

self-identity. Moral superiority is reaffirmed through an emphasis on individual-

istic factors in producing other peoples' poverty. Anderson (1990) documents

the same pattern in the black community. He notes that

by many employed and law-abiding blacks who live in the inner city, members of the

underclass are viewed, and treated, as convenient objects of scorn, fear, and embarrass-

ment. In this way the underclass serves as an important social yardstick that allows

working class blacks to compare themselves favorably with others they judge to be worse

off, a social category stigmatized within the community. (66)

Each of these authors emphasizes the tendency of employed strata residing

immediately above the poor to blame those in poverty to satisfy a need for

psychological distance and to legitimate their own limited successes.

Given the general structural position of employed minorities, I interpret the

effect of external self-explanations leading to individualistic beliefs as follows:

External self-explanations likely emerge as salient in an ego-defensive maneuver

arising from the sense of being held back by external, environmental forces in

one's own life (and almost certainly, given the strong group identification of

minorities, perceptions of general group deprivation and continued relative

disadvantage compared with whites). At the same time, however, these external

accounts do not dominate consciousness in psychologically consistent or

sociologically universalistic fashion as among whites because employed

minorities' relative success and perceptions of personal difference from the poor

are symbolically enhanced by using individualistic reasons for poverty. In this

way, the ego-defensive, external self-explanation is coupled with the ego-

defensive tendency to invoke individualistic explanations for the poor in an

effort to "salvage the sell" (Lewis 1978) and maintain a favorable self-identity.

Thus, whether internal or external self-explanations are salient, minorities

appear to exhibit a particularistic logic that implies a "sense of personal

difference"; different cultural themes are used to explain one's own biography

than are used to explain poverty. For minorities, in contrast with whites, what

is felt to be true for self is not the general rule applied to other members of

society. These findings, along with the patterns seen for several other variables

in Table 5, provide a clear answer to question 3 investigated by this article:

several of the included independent variables do operate differently for different

race/ethnic groups.24

Summary and Conclusions

This study has explored race/ethnic differences in stratification beliefs, focusing

specifically on the effects of race/ethnicity, other sociodemographic variables,

and two previously unexamined social-psychological variables on beliefs about

the causes of poverty. My interest in mapping what is believed, exploring

various antecedents to beliefs, and investigating differences in the determinants

across race/ethnic subgroups has resulted in complex set of results.

A finding consistent with past researRh was that blacks are significantly

more structuralist than whites in their thinking about poverty. Also consistent

with past studies are the reported effects of income, education, age, and sex.

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 313

Finally, I find support for the group identification explanation of stratification

beliefs, since significant race/ethnicity effects remain after the introduction of

SES statistical controls. The group identification explanation of structuralist

beliefs is complicated, however, by the simultaneous greater support found for

individualistic thinking among minorities, an unpredicted pattern that sets the

stage for a discussion of some counterintuitive findings.

Findings that past research did not lead us to expect dominate the current

study. The first counterintuitive findings are seen in an examination of the

marginals for the items representing the two dependent variables in Table 1. In

contrast to past research, which documents the dominance of individualistic

beliefs about poverty, this study finds that southern Californians in 1993 were

more structuralist in their thinking about the poor. This pattern holds for all

three race/ethnic groups. Kluegel and Smith's (1986) argument that structuralist

beliefs will increase in popularity during times of unusual socioeconomic crises

and racial strain explain the data. Considering the structural conditions and

recent events in the region under examination, including crises in the education-

al system, a recent economic recession, and the rioting in response to the

racially charged verdict in the Rodney King case, the popularity of items such

as "failure of society to provide good schools for many Americans," "failure of

private industry to provide enough good jobs," and "prejudice and discrimina-

tion" is not surprising.

The second main counterintuitive pattern is that blacks and Latinos attribute

more importance to both individualistic and structuralist reasons for poverty.

This finding runs counter to the prediction that racial/ethnic minorities would

be more structuralist, but not more individualistic, than whites. The observed

pattern is consistent with the arguments of Bobo (1991) and Mann (1970) that

general value consensus and individual value-consistency may be commonly

overestimated in theories of public opinion. Further, since it is the minority

populations who subscribe most strongly to structural thinking, Bobo's (1991)

explanation for the relative weakness of more egalitarian, structuralist outlooks

in American society is supported: it is not that such ideas are culturally

unavailable. Rather, the voices subscribing most strongly to alternatives to the

dominant ideology are the politically weakest voices in the crowd.

This study's separate treatment of Latinos adds to a growing body of

literature that demonstrates that this rapidly growing American minority group

warrants separate treatment in sociological studies of ideological beliefs. Latinos

clearly differ from both whites and blacks in objective status and ideological

characteristics. Also of interest, however, is the fact that despite the differences,

Latinos are also similar in some ways to blacks, suggesting that the influence of

similar social-structural positions as minority groups may override other

historical and cultural differences.

The other main contribution of this study is the examination of how various

variables operate differently within race/ethnic subgroups. The effects of self-

explanations are the most striking examples of such differences. The differences

suggest that our assumptions about consistency may be more a reflection of

whites' experience of the world and use of universalistic norms than a general

psychological tendency. Future social psychological research should consider the

extent to which our knowledge of such issues is shaped by the lack of studies

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

314 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

that include nonwhites. Further, such research should consider the implications

that minorities' distinct structural positions and experiences have on the content

and organization of the self, as well as how various patterns of self-organization

(e.g., the relative salience of internal and external self-explanations) affect

ideological beliefs about inequality and other social and political issues.

Future research should also investigate race/ethnic differences in how

persons' self-perceptions of their relative success or failure shape ideological

thinking. While I lack direct measures of perceived success or failure, it is

reasonable to suggest in light of our knowledge of attribution biases that

internal self-explanations are indicative of perceived relative success, while

external self-explanations are adopted in an ego-defensive manner to deflect

responsibility from the self when relative failure is perceived. Given this logic,

one can speculate about the distinctive effects of self-explanation in minority

groups. Specifically, the internal orientation is likely indicative of a kind of ego

security that enables respondents to adopt a more compassionate view of the

poor. As the poor represent no threat to the self when internal self-explanations

are salient, structural barriers can be invoked to explain others' poverty in a

"while I've made it because of me, the system keeps others down" fashion. For

minorities, personal biography is explained in particularistic fashion - in this

case, as an exception to the general rule that validates the moral claims of the

underdog. In contrast, external self-explanations likely flow from a kind of ego

vulnerability that is not conducive to the development of a structuralist

consciousness. Rather, extemal self-explanations among minorities appear to

cause actors to interpret others' lack of success in individualistic terms in a

"while I've been limited by outside forces, the poor only have themselves to

blame" fashion. Again, minority personal biography is understood in particular-

istic terms, in this case relative to ideological beliefs about the poor that deny

the moral claims of the underdog in the service of maintaining personal

exceptionalism and a favorable self-identity.

The growing inequality between a gainfully employed class and a growing

urban underclass within minority communities should motivate future

ethnographic and survey studies of ideological beliefs to examine the applicabil-

ity of theories of "middle" Americans' beliefs about the poor that were

originally developed among white populations (e.g., Lane 1962; Lewis 1978).

Further, future research should address in greater detail the ideological

implications of various manifestations of the self-concept in an effort to move

beyond those aspects of this study that have been necessarily speculative.

Speculation aside, however, this study has produced answers to the three main

questions posed at the outset: First, race/ethnic differences do exist in beliefs

about poverty. This study documents the unexpected pattem of blacks and

Latinos showing greater support for both structural and individualistic thinking

in comparison with whites. Second, the social-psychological variables do have

significant mediating effects on poverty beliefs net of respondents' background

characteristics. Finally, this study shows that the effects of several of the

independent variables on poverty beliefs do differ by race group, which calls

into question the implicit idea that these basic social-psychological processes

operate similarly for persons of all groupstand social locations.

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Race/ Ethnicity and Beliefs about Poverty / 315

Notes

1. Race/ethnicity is based on respondents' self identifications. The terms race/ethnicity and

race, African American and black, and Latino and Hispanic are used interchangeably in this

study.

2. Such reasoning can be traced to thinkers such as Levi-Strauss (1966) who hold that such

bipolar dichotomies are the result of oppositional human thought processes rooted in the

structure of the mind. This imagery survives in theories that assume that all beliefs can be

scaled along a single dimension (e.g., liberal-conservative), as well as in cognitive consistency

theories (Abelson et al. 1968), which hold that inconsistency is an unpleasant state that creates

a motivational drive toward resolution and consistency in beliefs (Kluegel & Smith 1986:15).

3. Kluegel and Smith (1986) state that "individual and structural explanations are not

alternatives" (17). Much research (Huber & Form 1973; Lane 1962; Mann 1970) supports the

"principle of cognitive efficiency," which holds that persons can hold both types of beliefs

simultaneously, rather than viewing them as alternatives in the quest for consistency (Kluegel

& Smith 1986).

4. Given Gurin, Miller, and Gurin's (1980) finding of strongest group identification among

blacks, along with the relative weakness of any class consciousness or class awareness in

American history, it is argued that racial minorities are more likely to respond to race

cleavages in forming a group identification.

5. See Sears and Funk (1991) for a thorough review of the concept of self-interest and its use in

studies of social and political attitudes. Sears and Funk are critical of the use of demographic

measures of self-interest and document the consistently greater explanatory power of symbolic

politics measures in predicting attitudes. While I am conceptualizing personal self-interest in

socioeconomic status terms, my comparison is with race/ethnicity (rather than symbolic politics

measures) in understanding beliefs about poverty.

6. Rather than assuming a single internal-external personality continuum (i.e., locus of control)

as conceptualized by Rotter (1966) and other psychological social psychologists, I take a

symbolic interactionist approach to analyzing the effects of two separate variables representing

vocabularies that individuals draw upon in varying degrees to explain their circumstances.

7. I am not arguing that these are identical, parallel attribution tendencies with one simply

referring to the self, and the other to the issue of poverty. I do, however, believe that it is

reasonable to assume a general similarity between the tendency to refer to internal/individual-

level properties of the self and to internal/individual-level properties of other people in

explaining why they are poor. Similarly, there is a basic similarity between the tendency to

refer to nonindividual/noninternal forces affecting the self and to nonindividual/noninternal

forces causing poverty. Kluegel and Smith (1986) use a similar interpretive strategy in referring

to ability and effort attributions as representing the person level, while referring to luck and

"being helped or held back by other people" (81) as external attributions. The empirical

implications of including and excluding luck in the measurement of the dependent variables

is explored in note 24.

8. While questions of causality between attitudes about self and other objects remain, I argue

- in light of past research, and the importance accorded to the self-concept in symbolic

interactionism - that it is reasonable to ask whether the way that people think about their

own societal positions affects how they think about other people's positions in society (e.g., the

poor). As a safeguard, models were run each way (i.e., with self-explanations as independent

variables and poverty beliefs as dependent variables, and vice versa) to ensure that the patterns

of effects are similar both ways. Results demonstrate that the patterns of effects are the same.

9. Several studies examining the beliefs and attitudes of nonwhite race/ethnic groups have

appeared in recent years (e.g., Guarnaccia, Angel & Worobey 1991; Smith 1990; Welch &

Sigelman 1988), most of which focus on race/ethnic group differences in adherence to

particular beliefs and attitudes (e.g., Banks & Juni 1991; Booth-Kewley, Rosenfeld & Edwards

1992). Despite these developments, studies that compare race/ethnic groups on the determinants

of beliefs and attitudes are still a rarity. It is the dearth of studies examining group differences

This content downloaded from

13.234.42.52 on Thu, 18 Aug 2022 12:39:23 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

316 / Social Forces 75:1, September 1996

APPENDIX: Items and Coding Used in Variable Construction

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC VARIABLES

Race Black - 1 Latino - 1

Other - 0 Other - 0

Gender Female - 1

Male - 0

Household Income

1. less than $14,999

2. between $15,000 and $24,999

3. between $25,000 and $34,999

4. between $35,000 and $44,999

5. between $45,000 and $59,999

6. between $60,000 and $74,999

7. between $75,000 and $99,999

8. above $100,000

Education Measured in years.

Age Measured in years.

STRATLFICATION BELIEFS

Interviewer statement: The following statements refer to possible reasons for poverty in

America. For each of the reasons, please tell me whether you think it is

(4) very important

(3) somewhat important

(2) not very important

(1) not at all important

as a reason for poverty.

Individualism (ct - .674):

1. Personal irresponsibility, lack of discipline among those who are poor.

2. Lack of effort by those who are poor.

3. Lack of thrift and personal money management.

4. Lack of ability and talent among those who are poor.

Structuralism (ct - .697):

1. Low wages in some businesses and industries.

2. Failure of society to provide good schools for many Americans.

3. Prejudice and discrimination.

4. Failure of private industry to provide enough jobs.

This content downloaded from