Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ira O. Wade - Organic Unity in Diderot. Vertumnis, Quotquot Sunt, Natus Iniquis

Uploaded by

나경태Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ira O. Wade - Organic Unity in Diderot. Vertumnis, Quotquot Sunt, Natus Iniquis

Uploaded by

나경태Copyright:

Available Formats

Organic Unity in Diderot: Vertumnis, quotquot sunt, natus iniquis

Author(s): Ira O. Wade

Source: L'Esprit Créateur , Spring 1968, Vol. 8, No. 1, Denis Diderot (Spring 1968), pp. 3-

14

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26277462

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to L'Esprit Créateur

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Organic Unity in Diderot

Vertumnis, quotquot sunt, natus iniquis

Ira Ο. Wade

HE PROBLEM of Diderot's unity is not new. Diderot himse

ί y in his correspondence with Sophie Volland often reverted to

his almost endless attempts to explain himself to his mistress but

above all to himself. The explanation was based more upon his tem

ment (see H. Dieckmann, "Zur Diderots Interpretation," Rom. F

1938, pp. 46-84), than upon the nature of his intellectual preoccupat

or the central focus of his interests, or the relative importance of

varied works. Diderot did see himself in that correspondence as

director of the Encyclopédie and the author of a number of unpubli

works. He acknowledged that his contemporaries would have to ju

him as encyclopedist, whereas his successors would want to judge

in terms of his unpublished work. There is no doubt, I suppose, th

the thing, in his opinion, which welds the two Diderots together —

Diderot of the Encyclopédie, and the Diderot of the unpublished wor

is thought. In the opening page of the Neveu, where the author is

obviously struggling to find a logical justification for his inner reality,

he places it squarely upon his thought ("mes pensées, ce sont mes

catins"). He even characterizes very neatly the nature of that thought and

the way it is brought by him into some organic unity: "Je m'entretiens

avec moi-même de politique, d'amour, de goût, ou de philosophie." If

one may trust the authenticity of an author's self-portrait, it is obvious

that Diderot saw himself as a kind of dialectician pursuing the rhythm

of his ideas as they eluded him, or as they varied in almost incessantly

paradoxical contradictions, or as they shifted like the weather vanes

in Langres of which he spoke when he sought an appropriate metaphor

for his inner personality.

There is much analogy between the way he saw himself and

Montaigne's discovery that man is "vain, divers, et ondoyant." One

might even extend the comparison and note that Diderot, like Montaigne,

Vol. Vin, No. 1

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

is constantly "essaying" an extraordinarily nimble wit upon the phen

ena of the universe. He, like Montaigne, is constantly trying to dep

the rhythm of becoming rather than the nature of being. Like Montaigne

also, he has some deep apprehension of the vitalism in that becomin

Finally, like his predecessor, he regards the ultimate goal of this in

lectual becoming as esthetic. However, if one examines carefully the

statement which we have just quoted from the Neveu, he would hav

to conclude that while the esthetic goal is readily apparent, the ultim

goal, even for Diderot, is philosophical. He saw himself, just as

contemporaries saw him, as "the Philosophe." That should induce

to give more attention to what he added to Dumarsais' article "Philo

phe" in the Encyclopédie.

Diderot's portrait of his inner self has been attempted often by tho

who have struggled with the problem of his unity. Sainte-Beuve, one

the first to take up the problem anew in the Portraits littéraires, I,

264, rather contradicts himself at every moment in his effort to get

the crux of the matter. Without much evidence, he declares that the

eighteenth-century writer was both "philosopher and artist," adds th

he was little interested in politics, although in philosophy, he was,

to speak, "the sould and the organ of the century." Sainte-Veuve insi

that Diderot is fundamentally encyclopedist, a kind of journalist, an

recalls Grimm's estimate of his colleague when he compared him

nature as Diderot always thought of nature — "riche, fertile, douce

sauvage, simple et majestueuse, bonne et sublime, mais sans aucu

principe dominant, sans maître et sans Dieu." Before he reaches the e

of his sprightly portrait, Diderot has become the atheistic philosop

who is so little atheistic that he is hardly more than a deist, the biologica

vitalistic, materialistic, natural philosopher whose naturalism tends

that inevitable deism. As artist and critic, he is, insists Sainte-Beuv

"eminent," while in the correspondence, he is "moraliste, peintre, c

que." It must be confessed that the portrait is excellent in rendering

intellectual dispersal of the eighteenth-century encyclopedist, in wh

the nineteenth-century critic could apparently find, to quote Grim

remark, "no dominating principle."

One of those in the early part of the twentieth century who did much

to attribute to Diderot the importance which he deserved was Profes

Jean Thomas whose Humanisme de Diderot (1932) has always b

considered one of the fine critical analyses of the eighteenth-centu

author. Thomas sees in Diderot a rather diminished replica of the hum

4 Spring 1968

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wadb

ist Montaigne, much overshadowed by Goethe. The sources

humanism, Thomas finds in the scientific training which Dider

himself and which preserved him from utopianism. His sen

has given him a sense of the beauty of the human body and the

awakened in him an enthusiasm for all the arts. His contact with artisans

and artists has made him respectful of the technical arts. Thus by

temperament, by his scientific training, by his artistic taste, and his

curiosity in the technical arts, Diderot's "humanism" has become the

most authentic, the richest, the most concrete of all the philosophies

of the century (p. 160). Thomas' presentation has received very general

commendation. Vernière approves his seeing in Diderot two important

principles: one a principle of unity dealing with the permanent proce

dures of his intellectual method, the other a principle of evolution,

responsible for the progress of his wisdom. He adds, though, that "dans

ce champ immense qui épuise les visées humaines, la clarté des approches

demeure diffuse" (P. Vernière, Diderot·. Œuvres philosophiques, Paris,

1956, p. xviii).

Professor Mornet also commended the Humanisme de Diderot·.

"M. Jean Thomas a eu raison de dire, dans un livre pénétrant, que le

Diderot de 1770 est assez différent du Diderot de 1746-1760, et que, de

la confusion de ses premières aspirations, il a peu à peu dégagé celles

qui lui étaient essentielles." However, not for that does Mornet approve

either the notions of unity or of evolution in Diderot. In his introduction

to Diderot, l'homme et l'œuvre (Paris, 1941), one of his most penetrating

eighteenth-century studies, Mornet calls the editor of the Encyclopédie a

"homo duplex," one of the most changeable and contradictory of men,

and adds that "there has not been any real evolution in Diderot" (p. 10).

Mornet grants that Diderot himself wanted to be a thinker, a "Philo

sophe," and a writer, an "artist." To achieve these two ambitions he was

forced to utilize two faculties utterly distinct: a lucid intelligence, cold,

logical, and conducted by experience, and sudden inspiration which

wells up from the heart, from enthusiasm, from genius. These two sources

of his thought are often in opposition, which accounts for the contra

dictions in his principles, in his methods, and in his conclusions. Mornet

notes that Diderot's conception of nature, his materialism, forms a unity,

but finds itself in conflict with the doctrine of human freedom, one of

Diderot's strongest assertions. There is a similar conflict between the

simple life of the savage and the necessity of a belief in progress. Mornet

concludes that always the author finds himself in disaccord with himself

Vol. VIII, No. 1 5

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

and that his thought and his work are directed often in two opposi

directions.

Since there is so much difficulty in establishing a unity in Didero

there has been a general tendency in Diderot criticism to seek out t

area in which he was most active and of most consequence. Beginnin

with Hermand's Morale de Diderot (1923) and continuing down

Proust's Diderot et l'Encyclopédie (1962) there have been numer

attempts to make Diderot a moralist, an esthetician, an Encyclopedi

a political and economic theorist, and a formal philosopher. Th

presentations are not always exclusive ; the critic may, on occasion, of

for study two aspects of his life as in the case of Professor L. Crocke

Two Diderot Studies: Ethics and Esthetics (Baltimore, 1952).

Crocker confesses in a foreword his inability to "bend Didero

thought to a mythical unity, rational or psychological." For him Di

rot's struggle "is his real personality, his real unity." Yet, elsewher

(p. 4), he declares it an error to analyze Diderot's ethics "without re

ence to the evolution of his thought in general," and he does not hesi

to characterize the structure of Diderot's thought as an interplay betw

morals and nature. He divides me etnicai tnougnt mto periods : a period

of "formalistic ethics," the moralistic type of thinking, a subsequent

period dominated by "scientific inquiry and positivistic naturalism,"

a period of "evolutionary" morality, etc. We must note, further, that this

ethical thought is said to have progressed dialectically and yet that

Diderot left "this synthesis in an undeveloped form that has concealed

its true worth and significance."

In the second essay, Crocker attempts a réévaluation of Diderot's

esthetic ideas. After quoting G. Boas to the effect that there is no need

for unity in eighteenth-century esthetic theory, L. Venturi's remark that

Diderot "has no original esthetic ideas," and F. O. Nolte's opinion

that Diderot was "primarily interested in social and moral, rather than in

esthetic values" (p. 51), Crocker sets out to discuss Diderot's treatment

of subjectivism and objectivism as a means of getting a clearer under

standing of the character of this esthetic thinking, through an analysis

of his attitudes toward basic problems which concern 1. the nature of

beauty, 2. the relationship between the artist and outside reality, 3.

whether the artist is merely an imitator of the beauty of the outside

world or whether he creates that beauty? 4. what is the role of the

imagination? and 5. the moral effect of the artist's work. Crocker finds

that, as in the case of the ethics, there is some sort of dialectical move

6 Spring 1968

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wade

ment in Diderot's concept of art which fluctuates (or hesitate

the objective and the subjective, and renders difficult the esta

of Diderot's ideas on taste and the role of the imagination

These hesitations Crocker attributes "to conflicting tendenc

himself" (p. 106). He notes that "his esthetics are not an inde

growth," that there is little "systematic theory," only "fragment

ments" which we have to piece together without imposing u

a "unity which Diderot never gave them" (p. 109). Nonetheless

tends to emphasize "a certain unity that underlies the divergen

and which our discussion has tried to make apparent. This u

in the nature of his [Diderot's] approach to art, in his consta

cupation with the artist's function of selecting and combinin

according to the triple standard of beauty, truth, and moralit

He concludes that "the simple fact is that Diderot has no defin

ent, esthetic philosophy, but a multiplicity of theories, flyin

the spokes of a wheel" (p. 114). Finally, he expresses a wel

impatience with those who treat Diderot's philosophy in par

And he concludes, in agreement with Dieckmann (op. cit., p.

"we must consider Diderot's work in its totality [italics Croc

else falsify him."

I want now to consider three other of our distinguishe

scholars who have turned from a Diderot "moraliste," a

rot "esthéticien" to espouse a Diderot "politique." The first o

Mr. Franco Venturi. Contrary to Mornet's belief that there is no

in Diderot's thought, Venturi (La Jeunesse de Diderot, Paris,

the preface of his work (p. 10) has distinguished three p

a period of preparation for the Encyclopédie, when Diderot

together his energy, his forces, and his ideas. This first phas

an end with the Penseés sur l'interprétation de la nature (1753

was followed by the period of the Encyclopédie and the thea

aspects, said Venturi, of the same movement. This second ph

1—4.4.1— J xl- - -ect

vi viijymiujuii, UUU1VJ, UJUU LAJLV^ OJL AA1 Hid LIV7JUL fl iUtad

(1750-65). 3. The Encyclopédie completed, Diderot withdr

public, writes for himself, and puts his experiences in a se

works, which he refuses to publish. He thus enters upon a

in which he attempts to refine and deepen the ideas

became the leader of his time. Of more consequence is V

tence that Diderot is too new to his ideas and too violent

to be considered a "littérateur," that he is neither a phil

Vol. Vin, No. 1 7

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

véritable sens du mot" nor a poet "au sens profond." His masterp

says Venturi, is the Encyclopédie. His great contribution consiste

giving a political meaning to Enlightenment philosophy (p. 9). Ve

calls it the new force of the Enlightenment coming after the lit

force and the religious force of the first half of the century, an

transformed France into the core of European Enlightenme

inserting the ideas and the aspirations of the philosophes int

history of France and of Europe. Diderot is largely responsible for

new political force.

Professor J. Proust (Diderot et L'Encyclopédie, Paris, 1962) con

ses in his preface that he has tried to seize Diderot's thought

becoming. The dominant nature of that thought being political,

admits that he has centered his study upon politics. He has giv

miciCMiiig ucumiiuu υι .l/iuciui s uuiiucpuuii ui puiiuus. îuui «tiixuic

de Diderot," he writes, "quelque soit son contenu, a d'abor

modifier l'opinion du lecteur pour en faire un citoyen

plus utile, et faire avancer par là une 'Révolution' néce

That is to say, it is first and foremost a political article.

that Venturi was of the same opinion. Nonetheless, h

parently feel that politics constitutes, even with the bro

he proposed, a unifying element in Diderot's thought, sin

himself for not treating Diderot's scientific contribution

pédie on the grounds that it has been fully treated in J. M

Curiously, he assures that this exclusion will not falsify o

of Diderot. On the other hand, he finds that, even with t

there is a coherence in Diderot's ideas for the period 1750

was writing for the Encyclopédie, although he fails to br

what this coherence amounts to. And his inference that there is a

difference between this period 1750-65 and the later period 1765-84

which proves that "son évolution n'est achevée en 1765," certainly

indicates that Diderot's unity consists of at least two things.

Professor Vernière has also returned to the importance of politics

in Diderot's thought. In the four volumes of Diderot texts with their

very important introductions, Vernière has undertaken to present a

philosophical, an esthetic, a political Diderot and the author of the

novels. He has not attempted, however, a synthesis of the four aspects

of the editor of the Encyclopédie. On the contrary, in the introduction

to the Œuvres philosophiques, he notes how risky it would be to give

off-hand an interpretation of the man and reduce his doctrines artificially

8 Spring 1968

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wade

to a unity (p. iii). Vernière admits that he has no ready expl

Diderot. He sees among contemporary critics two schools o

those who temper Diderot's prudences and judge him an id

humanist whose theses are fine paradoxes, and those who en

under their banner as a pretext for advancing a particular i

It is as a philosopher interested in politics that Vernière s

present-day importance of the eighteenth-century philosoph

notes that Diderot never passed for a political thinker, and quot

"Dans l'ordre politique, son influence est nulle." Howeve

states that in recent years, the rediscovery of Diderot's pape

ea a numoer or new worxs poriucany orienrea. verniere notes mat one

idea dominates the political essays of 1770-74: enlightened despotism

is not the true politics of the Enlightenment. Contrary to Proust wh

sees in the whole political development of Diderot in the Encyclopédie

a general tendency toward reform (see Proust, op. cit., chapters on

"Principes d'une politique" and "Diderot réformateur"), Vernière sees

in his conclusion a Diderot with a double vocation: "révolutionnaire et

réformiste, l'une qui pousse à reconstruire le monde, l'autre à l'amé

nager."

I have tried to present the considered opinions of these Diderot

scholars not with any desire to combat them. As a matter of fact, I find

them extremely interesting and, for the most part, well substantiated

opinions. It is true that they are at times self-contradictory and often the

judgments of one contradict the opinion of others. Since they are dealing

with a strong character who has these same characteristics, it is only

reasonable that their analyses should partake of this quality. Their error,

if error there is, consists not in misinterpreting Diderot's ideas, but in

failing to analyze the structure of his thinking until they attain the form

of his thought.

It should be noted that Diderot certainly did not pass through the

same sort of intellectual development which we have seen in Voltaire.1

Of the seven forces which combined to form ultimately Voltaire (free

thinking, Horatian poetry, seventeenth-century classical literature, utopie

novelists, England, deism, seventeenth-century philosophers), not one

was really essential to the formation of Diderot save the last one. Voltaire

See Professor Wade's article on "Organic Unity in Voltaire," in the winter

1967 issue of L'Esprit Créateur (Ed. note).

Vol. VIII, No. 1

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

had come into a world which was making a changeover from arts

letters to science, history, and philosophy with the result that he h

reorient himself totally to that changeover. Diderot, due to the fac

he appeared on the scene some twenty years after the debut of Vol

was not confronted with any necessity to readapt himself ; he could pr

by the change which had already been wrought. He had in reality

heir to all these changes chiefly through Voltaire's Lettres philos

ques, the Traité de métaphysique, the Eléments de la philosoph

Newton, and the histories. If it makes sense to divide the Enlighten

into a period of preparation and a period of philosophical express

Diderot only appeared with Rousseau at the beginning of the p

of philosophical expression.

He made his debut very modestly by adapting Shaftesbury's es

to his needs. His Pensées philosophiques tackled some of the deist

blems, but only at second hand. More effort was directed to the pr

of final causes in the Essai sur les aveugles, and problems of psyc

ical impact in the Essai sur les sourds et muets. With the Pensées

l'interprétation de la nature, whatever preparation Diderot had to

had been completed. These fragmentary attempts at structuring

always be characteristic of his work. Always the foundation of h

vities will be his thoughts. Always the range of these thoughts w

encyclopedic in character, that is, they will fluctuate in some sor

dialectical way over a wide area of content. They seem to express a

an open-ended dialectic which is incomplete. If they have any nuc

it will be in the realm of science, chiefly physiological science, but alw

with a philosophical conclusion. Diderot's interests in philosoph

both broad and deep. In a curious way, he pursues his ideas with

consistency, but he always attributes to them analogies which are

startling. The two essays on the blind and the deaf and dumb hav

their nature, biological connotations, but by analogy they carry metaph

ical as well as esthetic implications, since they concern the apprehe

of nature, the expression of nature, and the communication of n

Diderot does not, like Voltaire, reduce all science to morality. But

does try to equate the good, the true, and the beautiful, that is, he

that esthetic values enhance moral values, and moral values augm

metaphysical values. He has to be very concerned not only with t

analogies, but with their coherent integration.

The problem is very definitely a problem in methodology: inv

in it is 1. how to pass from the fact to the idea to the theory to

10 Spring 1968

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wade

doctrine to integrated action. Voltaire faced the same problem

too, had pretensions to being both encyclopedist and philosop

the fundamental problem of passing from thought to action

also the necessity of having to organize completely the catego

(religion, art, ethics, science, politics and economics, etc.) an

ities of the structured categories into the full life. And it en

the coherent, consistent, continuous expression of this full li

a way that it constantly changed not only the thought but, a

has noted in his Philosophy of the Enlightenment, the accept

thinking. Diderot's thought at first glance appears fragmentary,

contradictory, and above all, paradoxical. We readily concur

ambiguous, eclectic, self-assertive in an explosive way, and s

dictory in its facile conclusions. This is so because life is

v^juv^jwiwpc-vjioiii ίο uiLimaitiy a way υι uiiiuviiig, aiiu. aj_iww nig,

and philosophy, which is not a subject, but a way of life, draw

energy from the freedom of the human to wander among all th

subjects of life and to constitute thereby ways of thinking and being

All of this is clearly stated by Diderot himself in the article "é

me" in the Encyclopédie. There he defines the eclectic as a philo

who crushes out prejudices, tradition, antiquity, universal co

authority, everything which enslaves the mind, dares think by h

work back to the clearest general principles, examine them,

them, accept nothing except on the evidence of his experience or

son, and of all the philosophies he has examined impartially cre

private philosophy of his own. For the ambition of the eclectic is

be preceptor of humankind than to be its disciple, less to reform

than to reform himself, less to know the truth than to make it know

others. He is not one to plant, but rather one to harvest, and to s

wheat from the chaff. Diderot contrasts him with the sectarian. While

the latter has embraced the doctrine of another philosopher, the eclectic

recoenizes no master.

Diderot denies that there could exist an eclectic sect, unless one

designates a sect a group of people who have one principle in common.

For the eclectic, this principle is to submit his thoughts to no one, to

judge only by his own experience, and to doubt a truth, rather than risk,

by failing to examine things carefully, admitting a falsity. Diderot likens

them to sceptics, but he points out that they are not sceptics, because

they choose those things they believe true. They do not doubt every

thing. They are also more jealous of freedom of thought.

Vol. ΥΙΠ, No. 1 11

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

Eclecticism is thus not a new philosophy. Diderot argues that p

tically all heads of philosophical schools (Plato, Pythagoras, etc.) h

been eclectics. He finds it very difficult for a man of judgment acquain

with several schools of philosophy not to fall either into sceptici

eclecticism. However, eclecticism is not syncretism which is a sect

syncretist strengthens his sect by modifying the opinions of his maste

Diderot calls Luther, Cardano, Bruno syncretists; Francis Bacon is

eclectic — indeed, he established modern eclecticism. Finally, sync

are very numerous, eclectics are rare.

Diderot carefully describes the way the eclectic operates with

He does not gather truths in helter-skelter fashion; he does not

them isolated; he does not make them fit other truths according

definite plan. If a newly-discovered truth fits with a preceding pr

tion, he considers it true, if it does not fit, he suspends his judgm

if it opposes a previous proposition, he rejects it as false.

In spite of his obvious enthusiasm for eclecticism, Diderot has

tempt for the eclectic school which flourished at Alexandria from

fourth to the eighth century, calling it "le système d'extravagan

plus monstrueux qu'on puisse imaginer." He nonetheless in discussin

group (V, 273) was led to examine the relationship between their th

and poetic genius, enthusiasm, metaphysics, and the systematic s

This digression is important, since Diderot approved of this relatio

between poetry and philosophy.

He experienced some difficulty in bringing out these relations

however, all the more since he approved of modern eclectics as f

as he disapproved of ancient, alexandrian eclectics. He consequ

confused the eclectic's qualities which he admired with the exagger

of those qualities at Alexandria which he deplored. For him the t

eclectic is not an Alexandrian like Plotinus, it is Enlightened man

Descartes or Leibniz, or Diderot himself. Consequently, there are

analogies between an eclectic of this kind, and the poet, the enthu

the metaphysician, and the systematic philosopher. For, says Did

what is the genius of the poet except the talent of finding imag

causes for real effects, or imaginary effects for real causes? What

effect of enthusiasm in an inspired man, except the capacity to per

relationships in far-distant objects which no one has ever seen or

imagined? Where can not a metaphysician attain, who, aband

himself to meditation, turns his thoughts to God, Nature, space

12 Spring 1968

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Wade

time? What result will a systematic philosopher not achiev

pursue the explanation of a phenomenon through a long ch

jectures? The conclusion to which this leads is the convictio

eclectic is the poetic genius, the enthusiast, the metaphy

the systematic philosopher. He is, above all, Diderot.

Diderot attributed the movement of thought from the Re

to the activities of the eclectics. In a magnificent passage w

miniature philosophy of history, a personal confession, and

for the future, the editor of the Encyclopédie sums up the

of thought from the Renaissance to his day, tries to find

the continuation of thought, and proclaims the remaking of

by the eclectic (V, 283 ; regrettably, the passage is too long

in its entirety). Fundamental with Diderot is the conviction that

of human knowledge is a predestined road, from which it is

impossible for the human mind to stray. Every century h

and its great figures, and requires its special talents. He wh

with special talents no longer desirable in the age must eith

that age or consent to die. In the renewal of letters in the R

«rTiof «roc παργ!pH of fi-rcf «roc r»r\t fii=»«r nmrlnpfintic Knt o-r» pxrolnofirvr» rvF

the previous creations. And so, the intelligent turned toward

of grammar, erudition, criticism of literature and the objects of a

When finally the works of the past were understood, one proc

imitate them, and thereby appeared "discours oratoires," "vers

espèce," and a flowering of philosophical works. "On argumen

bâtit des systèmes, dont la dispute découvrit bientôt le fort et

It was at that moment that it became clear that no system co

cepted or rejected in entirety. The efforts made to establish

one gave rise to syncretism. But syncretism brought out the w

in all philosophies:

La nécessité d'abandonner la place qui tombait en ruine de tout c

jetter dans une autre qui ne tardait pas à éprouver le même sort, et

ensuite de celle-ci dans une troisième, que le temps détruisait encore

enfin d'autres entrepreneurs... à se transporter en rase campagne, afi

truire des matériaux de tant de places ruinées, auxquels on reconnaîtr

solidité, une cité durable, éternelle, et capable de résister aux efforts

détruit toutes les autres: ces nouveaux entrepreneurs s'appellèrent éc

In gathering the solid pieces from the ruins of the past, t

covered that some pieces were lacking for the new structure

Vol. VIII, No. 1 13

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

L'Esprit Créateur

universe. In fact, there was lacking "une infinité de matériaux." Con

vinced these materials are in nature, they set to work to discover them

That is what we now call "cultiver la philosophie expérimentale." It w

not enough, however, to select from the stones of the past those whic

are still valid and to add to them the newly-discovered materials

nature. "Il fallût s'assurer par la combinaison, qu'il était absolume

impossible d'en former un édifice solide et régulier, sur le modèle de

l'univers qu'ils avaient devant les yeux." Because, said Diderot, the

eclectics proposed nothing less than to rediscover the portfolio of th

"Grand Architecte" and the lost blueprints of the universe. But the m

terials are infinite, and the ways of putting them together are infini

also. Many of these ways, in fact, have been tried, but with little succe

Nonetheless, the eclectics continue the quest. These are the systemat

eclectics. Those who are convinced that nothing satisfactory can be ma

out of the present materials, seek new materials, while those who thin

that the moment of reconstruction of the old and the new material h

come, try to rebuild some part of the future edifice. That is the sta

we have now reached:

D'où l'on voit qu'il y a deux sortes d'eclectisme, l'un expérimental, qui consiste

à rassembler les vérités connues et les faits donnés, et à en augmenter le nombre

par l'étude de la nature; l'autre systématique qui s'occupe à comparer entr'elles

les vérités connues et à combiner les faits donnés, pour en tirer ou l'explication

d'un phénomène, ou l'idée d'une expérience. L'eclectisme expérimental est le

partage des hommes laborieux, l'eclectisme systématique est celui des hommes

de génie; celui qui les réunira, verra son nom placé entre les noms de Démocrite,

d'Aristote, et de Bacon.

Thus the human mind must always structure the inner human reality.

Revision is always a new form of vision ; reform, another kind of form ;

evolution, a different sort of revolution. Always change, not chance, is

king. The blueprints of the universe, though, have not been lost, as

Diderot assumed, they just have never been discovered. It could be that

they have not yet been made; it could even be that it is our task to

make them.

Princeton University

j4 Spring 1968

This content downloaded from

145.40.215.184 on Mon, 29 Aug 2022 09:10:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Cummins: ISX15 CM2250Document17 pagesCummins: ISX15 CM2250haroun100% (4)

- Derrida's of Grammatology'Document6 pagesDerrida's of Grammatology'Dave GreenNo ratings yet

- The Other Twelve Part 1Document5 pagesThe Other Twelve Part 1vv380100% (2)

- Deconstructing Derrida: Review of "Structure, Sign and Discourse in The Human Sciences"Document8 pagesDeconstructing Derrida: Review of "Structure, Sign and Discourse in The Human Sciences"gepeatNo ratings yet

- Baby DedicationDocument3 pagesBaby DedicationLouriel Nopal100% (3)

- Prose of the World: Denis Diderot and the Periphery of EnlightenmentFrom EverandProse of the World: Denis Diderot and the Periphery of EnlightenmentNo ratings yet

- Design of Purlins: Try 75mm X 100mm: Case 1Document12 pagesDesign of Purlins: Try 75mm X 100mm: Case 1Pamela Joanne Falo AndradeNo ratings yet

- Deleuze's NietzscheDocument19 pagesDeleuze's Nietzschelovuolo100% (1)

- Linux and The Unix PhilosophyDocument182 pagesLinux and The Unix PhilosophyTran Nam100% (1)

- Vattimo, Santiago Zabala (Editor) - Nihilism and Emancipation - Ethics, Politics, and Law (European Perspectives - A Series in Social Thought and Cultural CritDocument248 pagesVattimo, Santiago Zabala (Editor) - Nihilism and Emancipation - Ethics, Politics, and Law (European Perspectives - A Series in Social Thought and Cultural CritVlkaizerhotmail.com KaizerNo ratings yet

- Imagine There's No Heaven: How Atheism Helped Create the Modern WorldFrom EverandImagine There's No Heaven: How Atheism Helped Create the Modern WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (22)

- 03 IGT-Influence of Codes Guidelines and Other Regulations On The Tunnel Design in AustriaDocument48 pages03 IGT-Influence of Codes Guidelines and Other Regulations On The Tunnel Design in AustriaSudarshan GadalkarNo ratings yet

- RS2 Stress Analysis Verification Manual - Part 1Document166 pagesRS2 Stress Analysis Verification Manual - Part 1Jordana Furman100% (1)

- Castoriadis On Insignificance DialoguesDocument161 pagesCastoriadis On Insignificance DialoguesveraNo ratings yet

- Brill Numen: This Content Downloaded From 194.177.218.24 On Wed, 10 Aug 2016 22:30:43 UTCDocument26 pagesBrill Numen: This Content Downloaded From 194.177.218.24 On Wed, 10 Aug 2016 22:30:43 UTCvpglamNo ratings yet

- Rimbaud, Father of Surrealism. BaysDocument8 pagesRimbaud, Father of Surrealism. BaysAndrea M. Guardia H.No ratings yet

- Catherine & Diderot: The Empress, the Philosopher, and the Fate of the EnlightenmentFrom EverandCatherine & Diderot: The Empress, the Philosopher, and the Fate of the EnlightenmentNo ratings yet

- Diderot, DenisDocument3 pagesDiderot, DenisBrandon LookNo ratings yet

- The Metamorphosis of CultureDocument18 pagesThe Metamorphosis of CultureAryan DevNo ratings yet

- Eyal Peretz Dramatic Experiments Life According To DiderotDocument274 pagesEyal Peretz Dramatic Experiments Life According To DiderotDebjyoti SarkarNo ratings yet

- El Dorado en VoltaireDocument10 pagesEl Dorado en VoltaireWalter RomeroNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 134.122.135.234 On Sun, 01 Jan 2023 13:41:35 UTCDocument9 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 134.122.135.234 On Sun, 01 Jan 2023 13:41:35 UTCYanjieNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 133.9.137.186 On Tue, 01 Jun 2021 07:28:09 UTCDocument22 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 133.9.137.186 On Tue, 01 Jun 2021 07:28:09 UTCzokoNo ratings yet

- Jaep 82 54-69Document16 pagesJaep 82 54-69facien033314No ratings yet

- A Prophet in A Cloak of Reason FINALDocument7 pagesA Prophet in A Cloak of Reason FINALBrenda RubinoNo ratings yet

- Louis-Ferdinand Céline: Trolling For Another Time?: Luke WardeDocument16 pagesLouis-Ferdinand Céline: Trolling For Another Time?: Luke WardejendralaliciaNo ratings yet

- Remarks at MoMaDocument4 pagesRemarks at MoMaFrancis ProulxNo ratings yet

- The Society of The SpectacleDocument228 pagesThe Society of The SpectaclePepe PapaNo ratings yet

- The Eldorado Episode in Candide (William F. Bottiglia)Document10 pagesThe Eldorado Episode in Candide (William F. Bottiglia)ROBSON100% (1)

- DaseinDocument4 pagesDaseincabezadura2No ratings yet

- The Society of The Spectacle - Guy Debord - First, 2021 - Unredacted Word - 9781736961803 - Anna's ArchiveDocument227 pagesThe Society of The Spectacle - Guy Debord - First, 2021 - Unredacted Word - 9781736961803 - Anna's ArchivezenithwzjNo ratings yet

- Singer 1989Document13 pagesSinger 1989pitert90No ratings yet

- Wilhelm Dilthey's Doctrine of World Views - 1993Document23 pagesWilhelm Dilthey's Doctrine of World Views - 1993Manuel Dario Palacio Muñoz100% (1)

- Jean Francois LyotardDocument5 pagesJean Francois LyotardCorey Mason-SeifertNo ratings yet

- Logic and Sin: Wittgenstein's Philosophical Education at The Limits of LanguageDocument12 pagesLogic and Sin: Wittgenstein's Philosophical Education at The Limits of Languagemattsharpe1No ratings yet

- Die Blume Des Mundes': The Poetry of Martin Heidegger: Oxford German StudiesDocument22 pagesDie Blume Des Mundes': The Poetry of Martin Heidegger: Oxford German StudiesGuanaco TutelarNo ratings yet

- Mario PerniolaDocument14 pagesMario PerniolaGiwrgosKalogirouNo ratings yet

- Artifacts for Diderot's Elements of Physiology: An Expanded, Hybrid Translation and CommentaryFrom EverandArtifacts for Diderot's Elements of Physiology: An Expanded, Hybrid Translation and CommentaryNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University Press ELH: This Content Downloaded From 202.121.96.148 On Fri, 28 Apr 2017 14:28:22 UTCDocument20 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University Press ELH: This Content Downloaded From 202.121.96.148 On Fri, 28 Apr 2017 14:28:22 UTCracheltan925No ratings yet

- Documents Ines LindnerDocument20 pagesDocuments Ines LindneranthonyblokdijkNo ratings yet

- The Eldorado Episode in CandideDocument10 pagesThe Eldorado Episode in CandideFrancisco VidelaNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Boulter - Melancholy and The Archive - Trauma, History and Memory in The Contemporary Novel (Continuum Literary Studies) - Continuum (2011) PDFDocument217 pagesJonathan Boulter - Melancholy and The Archive - Trauma, History and Memory in The Contemporary Novel (Continuum Literary Studies) - Continuum (2011) PDFLouiza Inouri100% (1)

- Modernity and Its VicissitudesDocument26 pagesModernity and Its VicissitudesIana Solange Ingrid MarinaNo ratings yet

- DerridaDocument25 pagesDerridashilpi karakNo ratings yet

- L'Esthétique Naît-Elle Au Xviiie Siècle ?, Coordonné Par SergeDocument4 pagesL'Esthétique Naît-Elle Au Xviiie Siècle ?, Coordonné Par SergeAquinoNo ratings yet

- Jeannine Verdes Leroux Deconstructing Pierre Bourdieu Against Sociological Terrorism From The Left 2001 PDFDocument288 pagesJeannine Verdes Leroux Deconstructing Pierre Bourdieu Against Sociological Terrorism From The Left 2001 PDFdionisio88No ratings yet

- Heidegger's Philosophy SummaryDocument4 pagesHeidegger's Philosophy SummaryHomer NasolNo ratings yet

- The Odd Couple Heidegger and DerridaDocument36 pagesThe Odd Couple Heidegger and DerridaSanti MondejarNo ratings yet

- Heideggers ReticenceDocument33 pagesHeideggers ReticenceАнтон СвердликовNo ratings yet

- Diderot and The Encyclopædists (Vol 1 of 2) by Morley, John, 1838-1923Document139 pagesDiderot and The Encyclopædists (Vol 1 of 2) by Morley, John, 1838-1923Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Department of The Classics, Harvard UniversityDocument37 pagesDepartment of The Classics, Harvard UniversityJackob MimixNo ratings yet

- 10.2307@40903476 enDocument23 pages10.2307@40903476 enpedroboica2No ratings yet

- Dolan - The Right To Be - Heidegger 2020Document25 pagesDolan - The Right To Be - Heidegger 2020Nemo Castelli SjNo ratings yet

- Setenger Debaise 2018Document8 pagesSetenger Debaise 2018Carolina EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Essay On Rabindranath Tagore in HindiDocument8 pagesEssay On Rabindranath Tagore in Hindifeges1jibej3100% (2)

- Looking Back at Bourdieu PDFDocument19 pagesLooking Back at Bourdieu PDFmuhammad7abubakar7raNo ratings yet

- Situation Ism - Intro From WikipediaDocument91 pagesSituation Ism - Intro From WikipediaNativeSonFLNo ratings yet

- Nissani - 10 Cheers For InterdisciplinarityDocument16 pagesNissani - 10 Cheers For InterdisciplinarityAtiq AslamNo ratings yet

- Deconstructing Derrida: An Exploration of Jacques Derrida's Philosophy and DeconstructionFrom EverandDeconstructing Derrida: An Exploration of Jacques Derrida's Philosophy and DeconstructionNo ratings yet

- From Fraternity To SolidarityDocument24 pagesFrom Fraternity To Solidaritygharbiphilo7206No ratings yet

- Mark Taylor Derrida ObituaryDocument3 pagesMark Taylor Derrida ObituaryselenotropeNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 2.84.16.202 On Fri, 18 Mar 2022 10:02:04 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 2.84.16.202 On Fri, 18 Mar 2022 10:02:04 UTCrafaela sampaio agapito fernandesNo ratings yet

- Prophets of Extremity: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, DerridaFrom EverandProphets of Extremity: Nietzsche, Heidegger, Foucault, DerridaRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- J. Hillis Miller - "Derrida Enisled"Document29 pagesJ. Hillis Miller - "Derrida Enisled"xuaoqunNo ratings yet

- All Nobel Prizes in LiteratureDocument16 pagesAll Nobel Prizes in LiteratureMohsin IftikharNo ratings yet

- Materials Management - 1 - Dr. VP - 2017-18Document33 pagesMaterials Management - 1 - Dr. VP - 2017-18Vrushabh ShelkarNo ratings yet

- 2396510-14-8EN - r1 - Service Information and Procedures Class MDocument2,072 pages2396510-14-8EN - r1 - Service Information and Procedures Class MJuan Bautista PradoNo ratings yet

- Paper 1 Computer Science ASDocument194 pagesPaper 1 Computer Science ASLailaEl-BeheiryNo ratings yet

- Yu ZbornikDocument511 pagesYu ZbornikВладимирРакоњацNo ratings yet

- ManualDocument24 pagesManualCristian ValenciaNo ratings yet

- VTB Datasheet PDFDocument24 pagesVTB Datasheet PDFNikola DulgiarovNo ratings yet

- Half Yearly Examination, 2017-18: MathematicsDocument7 pagesHalf Yearly Examination, 2017-18: MathematicsSusanket DuttaNo ratings yet

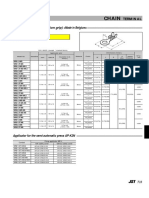

- Chain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)Document1 pageChain: SRB Series (With Insulation Grip)shankarNo ratings yet

- Aman Singh Rathore Prelms Strategy For UPSCDocument26 pagesAman Singh Rathore Prelms Strategy For UPSCNanju NNo ratings yet

- Kaun Banega Crorepati Computer C++ ProjectDocument20 pagesKaun Banega Crorepati Computer C++ ProjectDhanya SudheerNo ratings yet

- Review Course 2 (Review On Professional Education Courses)Document8 pagesReview Course 2 (Review On Professional Education Courses)Regie MarcosNo ratings yet

- Sousa2019 PDFDocument38 pagesSousa2019 PDFWilly PurbaNo ratings yet

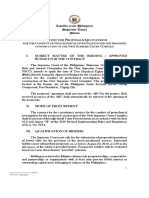

- Request For Proposals/quotationsDocument24 pagesRequest For Proposals/quotationsKarl Anthony Rigoroso MargateNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Familiarize The VmgoDocument10 pagesWeek 1 Familiarize The VmgoHizzel De CastroNo ratings yet

- Uniden PowerMax 5.8Ghz-DSS5865 - 5855 User Manual PDFDocument64 pagesUniden PowerMax 5.8Ghz-DSS5865 - 5855 User Manual PDFtradosevic4091No ratings yet

- The Philippine GovernmentDocument21 pagesThe Philippine GovernmentChristel ChuchipNo ratings yet

- Calendar of Activities A.Y. 2015-2016: 12 Independence Day (Regular Holiday)Document3 pagesCalendar of Activities A.Y. 2015-2016: 12 Independence Day (Regular Holiday)Beny TawanNo ratings yet

- Nursing Assessment in Family Nursing PracticeDocument22 pagesNursing Assessment in Family Nursing PracticeHydra Olivar - PantilganNo ratings yet

- A Structural Modelo of Limital Experienci Un TourismDocument15 pagesA Structural Modelo of Limital Experienci Un TourismcecorredorNo ratings yet

- Presentation LI: Prepared by Muhammad Zaim Ihtisham Bin Mohd Jamal A17KA5273 13 September 2022Document9 pagesPresentation LI: Prepared by Muhammad Zaim Ihtisham Bin Mohd Jamal A17KA5273 13 September 2022dakmts07No ratings yet

- Adolescents' Gender and Their Social Adjustment The Role of The Counsellor in NigeriaDocument20 pagesAdolescents' Gender and Their Social Adjustment The Role of The Counsellor in NigeriaEfosaNo ratings yet

- Shoshana Bulka PragmaticaDocument17 pagesShoshana Bulka PragmaticaJessica JonesNo ratings yet