Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mansfried and Milner (1999)

Uploaded by

Alinea OnasisCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mansfried and Milner (1999)

Uploaded by

Alinea OnasisCopyright:

Available Formats

The New Wave of Regionalism

Author(s): Edward D. Mansfield and Helen V. Milner

Source: International Organization, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Summer, 1999), pp. 589-627

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2601291 .

Accessed: 29/09/2013 21:54

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International

Organization.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The New Wave ofRegionalism

EdwardD. Mansfieldand Helen V. Milner

Introduction

Economicregionalism appearsto be growingrapidly.Whythishas occurredand

whatbearingit will have on theglobal economyare issues thathave generated

considerableinterest

anddisagreement. Some observers fearthatregionaleconomic

as theEuropeanUnion(EU), theNorth

institutions-such American FreeTradeAgree-

ment(NAFTA),Mercosur, andtheorganization ofAsia-Pacific

EconomicCoopera-

tion(APEC)-will erodethemultilateral systemthathas guidedeconomicrelations

sincetheend ofWorldWarII, promoting protectionismand conflict.

Othersargue

willfostereconomicopennessandbolsterthemultilateral

thatregionalinstitutions

system.Thisdebatehas stimulated a largeandinfluential

bodyofresearch byecono-

mistson regionalism'swelfareimplications.

Economicstudies,however, generally placelittleemphasison thepoliticalcondi-

tionsthatshaperegionalism. Lately,manyscholarshave acknowledged thedraw-

backsof suchapproachesandhavecontributed to a burgeoning thatsheds

literature

new lighton how politicalfactorsguidetheformation of regionalinstitutions

and

theireconomiceffects.Ourpurposeis toevaluatethisrecentliterature.

Muchof theexistingresearchon regionalism centerson internationaltrade(al-

thoughefforts havealso beenmadeto analyzecurrency markets, capitalflows,and

otherfacetsofinternational

economicrelations).1 Variousrecentstudiesindicatethat

whether stateschooseto enterregionaltradearrangements andtheeconomiceffects

ofthesearrangements dependon thepreferences ofnationalpolicymakers andinter-

estgroups,as wellas thenatureandstrength ofdomesticinstitutions.Otherstudies

focuson internationalpolitics,emphasizing how powerrelationsand multilateral

Forhelpfulcomments on earlierdrafts to David Baldwin,PeterGoure-

of thisarticle,we aregrateful

vitch,StephanHaggard,PeterJ.Katzenstein, David A. Lake,RandallL. Schweller, BethV. Yarbrough,

andthreeanonymous reviewers.In conductingthisresearch, Mansfieldwas assistedby a grantfromthe

Ohio StateUniversityOfficeofResearchandbytheHooverInstitution at Stanford

University,wherehe

was a NationalFellowduring1998-99.

1. On thisissue,see Cohen1997;Lawrence1996;andPadoan1997.

International

Organization

53, 3, Summer1999,pp. 589-627

? 1999byTheIO FoundationandtheMassachusetts Institute

ofTechnology

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

590 International

Organization

institutions

affecttheformation ofregionalinstitutions,

theparticularstatescompos-

ingthem,and theirwelfareimplications. We arguethattheseanalysesprovidekey

insights

intoregionalism'scausesandconsequences. Theyalso demonstrate therisks

associatedwithignoringitspoliticalunderpinnings.At thesametime,however, re-

centresearchleavesvariousimportant theoretical

and empiricalissuesunresolved,

includingwhichpoliticalfactors bearmostheavilyon regionalism andthenatureof

theireffects.

The resolutionoftheseissuesis likelytohelpclarify thenew "wave" of

whether

regionalismwillbe benignor malign.2 The contemporary spreadof regionaltrade

arrangementsis notwithouthistoricalprecedent.

Sucharrangements promoted com-

mercialopennessduringthenineteenth buttheyalso contributed

century, to eco-

nomicinstabilitythroughouttheerabetweenWorldWarsI andII. Underlying many

debatesaboutregionalism is whether thecurrentwave willhavea benigncast,like

thewavethataroseduringthenineteenth ora maligncast,liketheone that

century,

emergedduringtheinterwar period.Here,we arguethatthepoliticalconditions

surroundingthecontemporary episodeaugurwell foravoidingmanyof regional-

ism's moreperniciouseffects, althoughadditionalresearchon thistopicis sorely

needed.

We structureouranalysisaroundfourcentralquestions.First,whatconstitutes a

regionandhow shouldregionalism be defined?Second,whyhas thepervasiveness

ofregionaltradearrangements waxedandwanedovertime?Third,whydo countries

pursueregionaltradestrategies,insteadofrelying

solelyonunilateral ormultilateral

ones;andwhatdetermines theirchoiceofpartners inregionalarrangements? Fourth,

whatarethepoliticalandeconomicconsequencesofcommercial regionalism?

Regionalism:An ElusiveConcept

Extensivescholarlyinterestin regionalismhas yetto generatea widelyaccepted

definition

of it.Almostfifty yearsago, JacobVinercommented that"economists

haveclaimedtofinduse intheconceptofan 'economicregion,'butitcannotbe said

thattheyhavesucceededinfinding ofitwhichwouldbe ofmuchaid ...

a definition

in decidingwhether twoor moreterritories werein thesame economicregion."3

Since then,neithereconomistsnorpoliticalscientistshave made muchheadway

towardsettlingthismatter.4

Disputesoverthedefinition of an economicregionandregionalism hingeon the

importanceofgeographic proximity betweeneconomicflows

andontherelationship

andpolicychoices.A regionis oftendefinedas a groupof countrieslocatedin the

samegeographically specified

area.Exactlywhichareasconstituteregions,

however,

2. Bhagwatidistinguishes two waves of regionalism

sinceWorldWarII. The firstbeganin thelate

1950sandlasteduntilthe1970s;thesecondbeganinthemid-1980s.Thesewavesarediscussedatgreater

lengthlaterin thisarticle.See Bhagwati1993.

3. Viner1950,123.

4. On thisissue,see Katzenstein 1997a,8-11.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 591

remainscontroversial. Some observers, forexample,considerAsia-Pacifica single

region,othersconsideritan amalgamation oftworegions, andstillothersconsiderit

a combination of morethantworegions.Furthermore, a regionimpliesmorethan

just close physicalproximity amongtheconstituent states.The UnitedStatesand

Russia,forinstance, arerarely considered inhabitantsofthesameregion,eventhough

Russia's easterncoast is veryclose to Alaska. Besides proximity, manyscholars

insistthatmembers ofa commonregionalso sharecultural, economic,linguistic, or

politicalties.5Reflecting thisposition,KymAndersonandHege Norheimnotethat

"whilethereis no ideal definition [ofa region],pragmatism wouldsuggestbasing

thedefinition onthemajorcontinents andsubdividing themsomewhat according toa

combination ofcultural, language,religious, andstage-of-development criteria."6

Variousstudies,however, defineregionslargelyin termsof thesenongeographic

criteria andplacerelatively littleemphasisonphysicallocation.Forexample,France

andtheFrancophone countries ofNorthwest Africaareoftenreferred toas a regional

groupingbecause of theirlinguisticsimilarities. Also, social constructivistshave

arguedthatcountries sharinga communalidentity comprisea region,regardless of

theirlocation.7 In thelattervein,PeterJ.Katzenstein maintains thatregional"geo-

graphicdesignations are not 'real,' 'natural,'or 'essential.'Theyare sociallycon-

structed andpolitically contested andthusopento change."8Morecommonamong

scholarswhodefineregionsin nongeographic termsis a focuson preferential eco-

nomicarrangements, whichneednotbe composedof statesin close proximity (for

example,theUnitedStates-Israel FreeTradeAreaandtheLome Convention).

Settingasidetheissueofhowa regionshouldbe defined, questionsremainabout

whether regionalism pertainsto theconcentration of economicflowsor to foreign

policycoordination. Some analysesdefineregionalismas an economic process

whereby economicflows growmorerapidlyamonga givengroupof states(in the

sameregion)thanbetweenthesestatesandthoselocatedelsewhere. An increasein

intraregional flowsmay stemfromeconomicforces,like a higheroverallrateof

growth withinthanoutsidetheregion,as wellas fromforeign economicpoliciesthat

liberalizetradeamongtheconstituent statesanddiscriminate againstthirdparties.9

In a recentstudy, AlbertFishlowand StephanHaggardsharplydistinguish be-

tweenregionalization, whichrefers totheregionalconcentration ofeconomicflows,

andregionalism, whichtheydefineas a political processcharacterized byeconomic

policycooperation andcoordination amongcountries. 10Definedinthisway,commer-

cial regionalism has beendrivenlargelybytheformation andspreadofpreferential

tradingarrangements (PTAs). These arrangements furnish stateswithpreferential

accesstomembers' markets (forexample, theEuropeanEconomicCommunity [EEC]/

5. See, forexample,Deutschetal. 1957;Nye 1971;Russett1967;andThompson1973.

6. Anderson andNorheim1993,26.

7. Forexample,Kupchan1997.

-8. Katzenstein 1997a,7.

9. See, forexample,Krugman1991a; andFrankel,Stein,andWei 1995.Of course,regionalismmay

stemfroma combination ofeconomicandpoliticalforcesas well.

10. FishlowandHaggard1992.See also Haggard1997,48 fn.1; andYarbroughandYarbrough 1997,

160fn.1.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

592 International

Organization

EuropeanCommunity [EC]/European Union[EU],theEuropeanFreeTradeAssocia-

tion[EFTA],NAFTA,andtheCouncilforMutualEconomicAssistance[CMEA]);

manyofthemalso coordinate members' third

tradepoliciesvis-'a-vis parties.11

Among

thevarioustypesofPTAsarecustomsunions,whicheliminate tradebarriers

internal

andimposea commonexternal (CET); freetradeareas(FTAs),whicheliminate

tariff

internal butdo notestablisha CET; andcommonmarkets,

tradebarriers, whichallow

thefreemovement of factorsof production and finished productsacrossnational

borders.

12

Since muchof thecontemporary literatureon regionalismfocuseson PTAs,we

willemphasizetheminthefollowing consider

analysis.13Existingstudiesfrequently

PTAsas a group,rather amongthevarioustypesofthesearrange-

thandifferentiating

mentsordistinguishingbetweenbilateralarrangements andthosecomposedofmore

thantwo parties.To cast our analysisas broadlyas possible,we do so as well,

although someoftheinstitutionalvariationsamongPTAs willbe addressedlaterin

thisarticle.

EconomicAnalysesofRegionalism

Muchoftheliterature on regionalism focuseson thewelfareimplications ofPTAs,

bothformembers andtheworldas a whole.Developedprimarily byeconomists, this

researchservesas a pointofdeparture forthefollowing analysis,so we nowturntoa

briefsummary ofit.Preferential trading arrangements havea two-sided lib-

quality,

eralizingcommerceamongmemberswhilediscriminating againstthirdparties.14

Since sucharrangements rarelyeliminateexternaltradebarriers, economistscon-

sidertheminferior toarrangements thatliberalizetradeworldwide. Justhowinferior

PTAs are hingeslargelyon whethertheyare tradecreatingor tradediverting, a

distinction

originallydrawnbyViner.As he explained:

Therewillbe commodities . .. forwhichone ofthemembers ofthecustoms

unionwillnownewlyimport fromtheotherbutwhichitformerly didnotimport

at all becausethepriceoftheprotected domesticproductwas lowerthanthe

priceat anyforeign sourceplustheduty.Thisshiftin thelocusofproduction as

betweenthetwocountries is a shiftfroma high-cost

to a low-costpoint....

Therewillbe othercommodities whichone ofthemembers ofthecustomsunion

willnownewlyimport fromtheotherwhereasbeforethecustomsunionitim-

portedthemfroma thirdcountry, becausethatwas thecheapestpossiblesource

11. See, forexample,Bhagwati1993; Bhagwatiand Panagariya1996,4-5; de Melo and Panagariya

1993;andPomfret 1988.

12. See Anderson andBlackhurst 1993;andthesourcesinfootnote11,above.

13. In whatfollows,we referto regionalarrangementsandPTAsinterchangeably,whichis consistent

withmuchoftheexisting on regionalism.

literature

14. As de Melo andPanagariya pointout,"becauseunderregionalism

preferences

areextendedonlyto

partners,itis discriminatory.

Atthesametimeitrepresents a movetowardsfreertradeamongpartners."

de Melo andPanagariya1993,4.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 593

oftheduty.The shiftinthelocusofproduction

ofsupplyevenafterpayment is

nownotas betweenthetwomember countriesbutas betweena low-costthird

andtheother,

country member

high-cost, country.15

Vinerdemonstrated thata customsunion'sstaticwelfareeffects on members and

theworldas a wholedependon whether itcreatesmoretradethanit diverts. In his

words,"Wherethetrade-creating forceis predominant, one ofthemembers at least

mustbenefit, bothmaybenefit, thetwocombinedmusthave a netbenefit, and the

worldat largebenefits....Wherethetrade-diverting effectis predominant, one at

leastof themembercountries is boundto be injured,bothmaybe injured,thetwo

combinedwillsuffer a netinjury, andtherewillbe injurytotheoutsideworldandto

theworldat large."16 Vineralso demonstrated thatitis verydifficult to assessthese

effects

on anything otherthana case-by-case basis.Overthepastfifty years,a wide

varietyof empiricalefforts have been madeto determine whether PTAs are trade

creatingortradediverting.As we discusslater,thereis widespread consensusthatthe

preferential

arrangements forgedduringthenineteenth century tendedto be trade

creatingandthatthoseestablished betweenWorldWarsI andII tendedto be trade

diverting;however, thereis a strikinglackofconsensuson thisscoreaboutthePTAs

developedsinceWorldWar11.17

Evenifa PTAis tradediverting, itcan nonetheless enhancethewelfareofmem-

bersbyaffecting theirtermsoftradeandtheircapacitytorealizeeconomiesofscale.

Forminga PTA typically improvesmembers'termsoftradevis-'a-vis therestofthe

world,sincethearrangement almostalwayshasmoremarket powerthananyconstitu-

entparty. At thesametime,however,Paul Krugmanpointsoutthatattempts by a

PTAtoexploititsmarket powermaybackfire ifothersucharrangements exist,since

"theblocsmaybeggareachother. Thatis, formation ofblocscan,in effect, setoffa

beggar-alltradewarthatleaveseveryone worseoff."18 He arguesthatthesebeggar-

thy-neighbor effectsare minimizedwhenthenumberof tradeblocs is eithervery

largeor verysmall.19 The existenceof a singleglobalbloc is equivalentto a free-

tradesystem, whichobviouslypromotes bothnationalandglobalwelfare. In a world

composedofmanysmallblocs,littletradediversion is expectedbecausetheoptimal

foreachblocis quitelow andthedistortionary

tariff effectofa tariffimposedbyany

oneis minimal. By contrast, Krugman claimsthata system ofthreeblocscanhavean

especiallyadverseimpacton globalwelfare.Underthesecircumstances, each bloc

has somemarket power,thepotential flowofinterbloc commerce is substantial, and

tradebarriersmarkedly distortsuchcommerce.

15. Viner1950,43. Forcomprehensive overviewsoftheissuesaddressedin thissection,see Baldwin

andVenables1995; Bhagwati1991,chap.5; Bhagwatiand Panagariya1996; Gunter1989; Hine 1994;

andPomfret 1988.

16. Viner1950,44.

17. One reasonforthelack of consensuson thisissueis thedearthof reliableinformationaboutthe

degreetowhichpricechangesinducesubstitution acrossimports fromdifferent Another

suppliers. reason

counterfactuals

associatedwithconstructing

is thedifficulty (or "antimondes") thatadequatelygaugethe

effectsofPTAs.On theseissues,see Hine 1994;andPomfret 1988,chap.8.

18. Krugman1991a,16.

19. See ibid.;andKrugman1993,61.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

594 International

Organization

Consistent withthisproposition, a seriesof simulationsby Jeffrey A. Frankel,

ErnestoStein,andShang-Jin Weirevealthatworldwelfareis reducedwhentwoor

threePTAs exist,dependingon theheightof theexternaltariffs of each arrange-

ment.20T. N. SrinivasanandEricBondandConstantinos Syropoulos, however, have

theassumptions

criticized underlying Krugman'sanalysis.2'In addition,variousob-

servershavearguedthatthestaticnatureofhismodellimitsitsabilitytoexplainhow

PTAs expandand thewelfareimplications These debatesfurther

of thisprocess.22

reflectthedifficulty thateconomistshave had drawinggeneralizations aboutthe

welfareeffects ofPTAs.As one recentsurveyconcludes,"analysisof thetermsof

tradeeffectshastendedtowardthesamedepressing ambiguityas therestofcustoms

uniontheory."23

A regionaltradearrangement can also influencethewelfareofmembers byallow-

ingfirms to realizeeconomiesof scale. Overthreedecadesago,JagdishBhagwati,

CharlesA. CooperandBentonF. Massell,andHarryJohnson foundthatstatescould

reducethecostsof achievinganygivenlevelofimport-competing industrialization

byforming a PTAwithin whichscaleeconomiescouldbe exploited andthendiscrimi-

natingagainstgoodsemanating fromoutsidesources.24 Indeed,thismotivation con-

tributedtothespateofPTAsestablished bylessdevelopedcountries (LDCs) through-

out the 1960s.25More recentstudieshave examinedhow scale economieswithin

regionalarrangements canfoster greater andcompetition

specialization andcan shift

thelocationofproduction amongmembers.26 Although theseanalysesindicatethat

PTAs could yieldeconomicgainsformembersand adverselyaffectthirdparties,

theyalso underscore regionalism's uncertain welfareimplications.27

Besidesitsstaticwelfareeffects, economists havedevotedconsiderable attention

to whether regionalism willaccelerateorinhibitmultilateral tradeliberalization,an

issuethatBhagwatirefers to as "thedynamictime-path question."28Severalstrands

of researchsuggestthatregionaleconomicarrangements mightbolstermultilateral

openness.First,MurrayC. KempandHenryWanhavedemonstrated thatitis pos-

sibleforanygroupofcountries to establisha PTAthatdoes notdegradethewelfare

of eithermembers orthirdparties,and thatincentives existfortheunionto expand

untilitincludesall states(thatis, untilglobalfreetradeexists).29Second,Krugman

andLawrenceH. Summersnotethatregionalinstitutions reducethenumberofac-

torsengagedinmultilateral negotiations, therebymutingproblems ofbargaining and

collectiveactionthatcan hampersuchnegotiations.30 Third,thereis a widespread

20. Frankel, Stein,andWei 1995.

21. See BondandSyropoulos1996a;andSrinivasan1993.

22. See BhagwatiandPanagariya1996,47;andSrinivasan1993.

23. Gunter1989,16.See also BaldwinandVenables1995,1605.

24. See Bhagwati1968;CooperandMassell 1965a,b;andJohnson1965.

25. Bhagwati1993,28.

26. See, forexample,Krugman1991b;andPadoan1997,108-109.

27. See BaldwinandVenables1995,1605-13;andGunter1989,16-21.

28. See Bhagwati1993;andBhagwatiandPanagariya1996.

29. KempandWan1976.

30. See Krugman1993;andSummers1991.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 595

beliefthatregionaltradearrangements

caninducemembers andconsoli-

toundertake

dateeconomicreforms andthatthesereforms

arelikelytopromote

multilateral

open-

ness.31

However,clearlimitsalso existon theabilityof regionalagreements to bolster

multilateralism. Bhagwati, forexample,maintains thatalthough theKemp-Wan theo-

remdemonstrates thatPTAscouldexpanduntilfreetradeexists,thisresultdoes not

specifythelikelihoodof suchexpansionorthatitwilloccurin a welfare-enhancing

way.32 In addition, BondandSyropoulosarguethattheformation ofcustomsunions

mayrendermultilateral tradeliberalizationmoredifficult by undercutting multilat-

eralenforcement.33 ButKyleBagwellandRobertStaigershowthatPTAshavecon-

tradictory effects ontheglobaltrading system. Theyclaimthat"therelativestrengths

ofthese.. . effects determinetheimpactofpreferential agreement on thetariff

struc-

tureunderthemultilateral agreement, and ... preferentialtradeagreements can be

eithergood or bad formultilateral tariff

cooperation,dependingon the param-

eters."34Theydo conclude,however, that"it is preciselywhenthemultilateral sys-

temis workingpoorlythatpreferential agreements can have theirmostdesirable

effectson themultilateral system."35

Economicanalysesindicatethatregionalism's welfareimplications have varied

starkly overtimeandacrossPTAs.As FrankelandWeiconclude,"regionalism can,

depending on thecircumstances, be associatedwitheithermoreorless generalliber-

alization."36 In whatfollows,we arguethatthesecircumstances involvepolitical

conditions thateconomicstudiesoftenneglect.Regionalism can also haveimportant

politicalconsequences, andthey, too,havebeengivenshortshrift inmanyeconomic

studies.Lately,theseissueshave attracted growinginterest, sparking a burgeoning

literatureon thepoliticaleconomyof regionalism. We assess thisliterature after

conducting a briefoverviewofregionalism's historical

evolution.

Regionalismin HistoricalPerspective

Considerable has beenexpressedin howthepreferential

interest economicarrange-

mentsformedafterWorldWarII have affected and will subsequentlyinfluence the

globaleconomy. We focusprimarily on thiseraas well;however,itis widelyrecog-

nizedthatregionalismis notjusta recentphenomenon. Analysesofthecurrent spate

of PTAs oftendrawon historical analogiesto priorepisodesof regionalism. Such

analogiescan be misleadingbecausethepoliticalsettings in whichtheseepisodes

arosearequitedifferentfromthecurrent To developthispoint,itis usefulto

setting.

31. See, forexample,Lawrence1996;andSummers1991.

32. Bhagwati1991,60-61; and 1993.

33. BondandSyropoulos1996b.

34. BagwellandStaiger1997,27.

35. Ibid.,28.

36. FrankelandWei 1998,216.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

596 International

Organization

beginbydescribing eachofthefourwavesofregionalism thathavearisenoverthe

pasttwocenturies.

The initialepisodeoccurredduringthesecondhalfofthenineteenth century and

was largelya Europeanphenomenon.37 Throughout thisperiod,intra-Europeantrade

bothrosedramatically a vastportionof globalcommerce.38

and constituted More-

over,economicintegration became sufficientlyextensivethat,by theturnof the

twentieth century,Europehad begunto function as a singlemarketin manyre-

spects.39The industrialrevolutionand technological advancesattendant to it that

interstate

facilitated commerce clearlyhadpronounced effectson Europeanintegra-

tion;butso didthecreationofvariouscustomsunionsandbilateral tradeagreements.

Besides thewell-known GermanZollverein,theAustrianstatesestablisheda cus-

tomsunionin 1850,as did Switzerland in 1848,Denmarkin 1853,andItalyin the

1860s. The lattercoincidedwithItalianstatehood, notan atypicalimpetusto the

of a PTA in thenineteenth

initiation century.In addition, variousgroupsof nation-

statesforgedcustomsunions,including SwedenandNorwayandMoldaviaandWal-

lachia.40

The development of a broadnetworkof bilateralcommercialagreements also

contributed to the growthof regionalismin Europe.Precipitated by the Anglo-

Frenchcommercial treatyof 1860,theywerelinkedbyunconditional most-favored-

nation(MFN) clausesandcreatedthebedrockoftheinternational economicsystem

untilthedepression inthelatenineteenth Furthermore,

century.41 thedesirebystates

outsidethiscommercial network togaingreateraccesstothemarkets ofparticipants

stimulatedits rapidspread.As of thefirstdecade of thetwentieth century, Great

Britainhadconcludedbilateral arrangements withforty-six

states,Germany haddone

so withthirty countries,and Francehad done so withmorethantwentystates.42

These arrangements contributedheavilyto theunprecedentedgrowthof European

integrationandtotherelatively openinternational

commercialsystem thatcharacter-

ized thelatterhalfof thenineteenth century,underpinningwhatDouglasA. Irwin

referstoas an eraof "progressivebilateralism."43

WorldWarI disrupted thegrowthof regionaltradearrangements. But a second

waveofregionalism, whichhada decidedlymorediscriminatory castthanitsprede-

cessor,begansoonafterthewarended.The regionalarrangements formed between

37. See, forexample,Kindleberger 1975; and Pollard1974.However,regionalism was notconfined

solelyto Europeduringthisera.Priorto 1880,forexample,India,China,andGreatBritaincomprised a

"tightly-knit bloc" inAsia.Afterward,

trading Japan'seconomicdevelopment anditsincreasingpolitical

powerledtokeychangesinintra-Asian tradepatterns.KenwoodandLougheedreport that"Asia replaced

EuropeandtheUnitedStatesas themainsourceofJapaneseimports, supplyingalmostone-halfofthese

needsby 1913.By thatdateAsia hadalso becomeJapan'sleadingregionalexportmarket." Kenwoodand

Lougheed1971,94-95.

38. Pollard1974,42-51, 62-66.

39. Kindleberger 1975;andPollard1974.Ofcourse,tradegrewrapidlyworldwide duringthisera,but

theextent ofitsgrowth andofeconomicintegration was especiallymarkedinEurope.

40. See Irwin1993,92; andPollard1974,118.

41. See, forexample,Irwin1993;KenwoodandLougheed1971;andPollard1974.

42. Irwin1993,97.

43. Ibid.,114.See also Pollard1974,35.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 597

WorldWarsI andII tendedtobe highlypreferential. Some werecreatedto consoli-

datetheempiresofmajorpowers,including thecustomsunionFranceformed with

members ofitsempirein 1928andtheCommonwealth systemofpreferences estab-

lishedby GreatBritainin 1932.44Most,however,wereformedamongsovereign

states.For example,Hungary, Romania,Yugoslavia,and Bulgariaeach negotiated

tariff

preferences on theiragriculturaltradewithvariousEuropeancountries. The

RomeAgreement of 1934led totheestablishment ofa PTAinvolving Italy,Austria,

and Hungary. Belgium,Denmark,Finland,Luxembourg, theNetherlands, Norway,

andSwedenconcludeda seriesofeconomicagreements throughoutthe1930s.Ger-

manyalso initiatedvariousbilateraltradeblocs duringthisera.Outsideof Europe,

theUnitedStatesforgedalmosttwodozenbilateralcommercial agreements during

themid-1930s,manyofwhichinvolvedLatinAmericancountries.45

Longstanding andunresolved debatesexistaboutwhether regionalism deepened

theeconomicdepression oftheinterwar periodandcontributed topoliticaltensions

culminating in WorldWar11.46Contrasting thisera withthatpriorto WorldWarI,

Irwinpresents theconventional view: "In thenineteenthcentury,a network oftrea-

tiescontainingthemostfavorednation(MFN) clausespurred majortariffreductions

in Europeand aroundtheworld,[ushering] in a harmoniousperiodof multilateral

free trade thatcompares favorablywith . . . the recentGATT era. In the interwar

period,by contrast, discriminatorytradeblocs and protectionistbilateralarrange-

mentscontributed to the severecontraction of worldtradethataccompaniedthe

GreatDepression."47 The latterwave of regionalism is oftenassociatedwiththe

pursuitof beggar-thy-neighbor policiesand substantial tradediversion, as well as

heightened politicalconflict.

Scholarsfrequently attribute

theriseofregionalism duringtheinterwar periodto

states'inability solutionsto economicproblems.As A. G.

to arriveat multilateral

KenwoodandA. L. Lougheednote,"The failureto achieveinternational agreement

on matters oftradeandfinancein theearly1930sled manynationsto considerthe

alternative

possibilityoftradeliberalizing

agreements on a regionalbasis."48In part,

amongthemajorpowersandtheuse of

thisfailurecanbe tracedtopoliticalrivalries

regionaltradestrategies by thesecountries formercantilist purposes.49Hence,al-

thoughregionalism was notnew,boththepoliticalcontextin whichit aroseandits

consequences werequitedifferentthanbeforeWorldWarI.

44. Pollard1974,145.

45. On thecommercialarrangements discussedin thisparagraph, see Condliffe1940, chaps. 8-9;

Hirschman [1945] 1980;KenwoodandLougheed1971,211-19; andPollard1974,49.Although ourfocus

is on commercial regionalism,itshouldbe notedthattheinterwarerawas also markedbytheexistenceof

at least fivecurrency regions.For an analysisof thepoliticaleconomyof currency regions,see, for

example,Cohen1997.

46. See, forexample,Condliffe1940,especiallychaps.8-9; Hirschman[1945] 1980; Kindleberger

1973;andOye 1992.

47. Irwin1993,91.He notesthatthesegeneralizationsaresomewhat inaccurate,

as do Eichengreen and

Frankel1995.Butbothstudiesconfirm thatregionalism effects

had different duringthenineteenth cen-

tury,theinterwar period,andthepresent;andbothviewregionalism intheinterwarperiodas mostmalign.

48. KenwoodandLougheed1971,218.

49. See Condliffe 1940;Eichengreen andFrankel1995,97; andHirschman [1945] 1980.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

598 International

Organization

RegionalismSince WorldWarII

SinceWorldWarII, stateshavecontinued toorganizecommerce on a regionalbasis,

despitetheexistenceof a multilateral economicframework. To analyzeregional-

ism's contemporary growth,some studieshave assessed whether tradeflowsare

becomingincreasingly concentratedwithingeographically specifiedareas. Others

haveaddressedtheextentto whichPTAs shapetradeflowsandwhether theirinflu-

enceis rising.Stillothershaveexaminedwhether theratesat whichPTAsformand

statesjoin themhaveincreasedovertime.In combination, thesestudiesindicatethat

commercial regionalism has grownconsiderably overthepastfifty years.

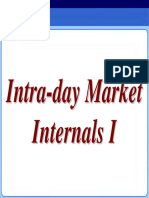

As shownin Table 1-which presentsdata used in threeinfluential studiesof

regionalism-the regionalconcentration oftradeflowsgenerally hasincreasedsince

theendofWorldWar11.50Muchofthisoveralltendency is attributable

torisingtrade

within Western Europe-especiallyamongpartiesto theEC-and within EastAsia.

Some evidenceof an upwarddrift in intraregionalcommercealso existswithinthe

AndeanPact,theEconomicCommunity of WestAfricanStates(ECOWAS), and

betweenAustraliaandNew Zealand,although outsideoftheformer twogroupings,

intraregionaltradeflowshavenotgrownmuchamongdeveloping countries.

Onecentral reasonwhytradeis so highlyconcentrated within manyregionsis that

stateslocatedincloseproximity oftenparticipateinthesamePTA.51Thattheeffects

of variousPTAs on commercehaverisenovertimeconstitutes furtherevidenceof

regionalism's growth.52As thedata in Table 1 indicate,theinfluence of PTAs on

tradeflowshasbeenfarfromuniform. Some PTAs,liketheEC, seemtohavehada

profound effect,whereasothershave had littleimpact.53 But thedataalso indicate

that,in general,tradeflowshavetendedto increaseovertimeamongstatesthatare

members ofa PTAandnotmerelylocatedinthesamegeographic region,suggesting

thatpolicychoicesare at leastpartlyresponsible fortheriseof regionalism since

WorldWarII.

East Asia, however,is an interesting exception.Virtually no commercialagree-

mentsexistedamongEast Asian countries priorto themid-1990s,butrapid,eco-

nomicgrowththroughout theregioncontributed to a dramaticincreasein intra-

regionaltradeflows.54In lightofAsia's recentfinancialcrisis,itwillbe interesting

to

see whether theprocessof regionalization continues.Severeeconomicrecession

50. Thesedefineregionalismin somewhat different

ways.Anderson andNorheimexaminebroadgeo-

graphicareas,de Melo andPanagariya analyzePTAs,andFrankel, Stein,andWeiconsidera combination

of geographiczones and PTAs. See Andersonand Norheim1993; de Melo and Panagariya1993; and

Frankel,Stein,andWei 1995.

51. On theeffectsofPTAsontradeflows,see,forexample,Aitken1973;Frankel1993;Frankel, Stein,

andWei 1995;Linnemann1966;Mansfieldand Bronson1997;Tinbergen 1962; andWintersandWang

1l994.

52. See, forexample,Aitken1973;Frankel1993;andFrankel, Stein,andWei 1995.

53. Note,however,thatsome PTAs-especially Mercosur-havehad a largeeffecton tradesince

1990.Theireffectsarenotcaptured inTable 1.We aregratefultoStephanHaggardforbringing thispoint

toourattention.

54. See Andersonand Blackhurst 1993,8; Frankel1993; Frankel,Stein,and Wei 1995; and Saxon-

house1993.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 599

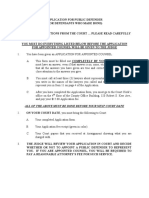

TABLE 1. Intraregionaltradeflows duringthepost-WorldWarII era

A. Intraregional

tradedividedbytotaltradeofeach region

Region 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990

EastAsia 0.199 0.198 0.213 0.229 0.256 0.293

WesternHemisphere 0.315 0.311 0.309 0.272 0.310 0.285

EuropeanCommunity 0.358 0.397 0.402 0.416 0.423 0.471

EuropeanFreeTradeArea 0.080 0.099 0.104 0.080 0.080 0.076

Mercosur 0.061 0.050 0.040 0.056 0.043 0.061

AndeanPact 0.008 0.012 0.020 0.023 0.034 0.026

NorthAmericanFreeTrade 0.237 0.258 0.246 0.214 0.274 0.246

Agreement

B. Intraregional

mnerchandise

exportsdividedbytotalmerchandise

exportsofeach region

Region 1948 1958 1968 1979 1990

WesternEurope 0.430 0.530 0.630 0.660 0.720

EasternEurope 0.470 0.610 0.640 0.540 0.460

NorthAmerica 0.290 0.320 0.370 0.300 0.310

SouthAmerica 0.200 0.170 0.190 0.200 0.140

Asia 0.390 0.410 0.370 0.410 0.480

Africa 0.080 0.080 0.090 0.060 0.060

MiddleEast 0.210 0.120 0.080 0.070 0.060

World 0.330 0.400 0.470 0.460 0.520

C. Intraregional

exportsdividedbytotalexportsofeach region

Region 1960 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990

EuropeanCommunity 0.345 0.510 0.500 0.540 0.545 0.604

EuropeanFreeTradeArea 0.211 0.280 0.352 0.326 0.312 0.282

AssociationofSoutheast

AsianNations 0.044 0.207 0.159 0.169 0.184 0.186

AndeanPact 0.007 0.020 0.037 0.038 0.034 0.046

Canada-UnitedStatesFreeTradeArea 0.265 0.328 0.306 0.265 0.380 0.340

CentralAmerican CommonMarket 0.070 0.257 0.233 0.241 0.147 0.148

LatinAmerican FreeTradeAssociation/ 0.079 0.099 0.136 0.137 0.083 0.106

LatinAmericanIntegration

Association

EconomicCommunity ofWestAfrican N/A 0.030 0.042 0.035 0.053 0.060

States

Preferential

TradingAreaforEasternand N/A 0.084 0.094 0.089 0.070 0.085

SouthernAfrica

Australia-NewZealandCloserEconomic 0.057 0.061 0.062 0.064 0.070 0.076

RelationsTradeAgreement

Source:Data inpartA aretakenfromFrankel,Stein,andWei 1995;partB, fromAndersonand

Norheim1993;andpartC, fromde Melo andPanagariya1993.

Note:N/Aindicatesdataunavailable.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

600 International

Organization

withinAsia concurrent withrobustgrowthin NorthAmericaand WesternEurope

mayredirect tradeflowsacrossregions.Thiscase illustrates

theneedwe described

earliertodistinguish betweenpolicy-induced

regionalismandthatstemming primar-

ily fromeconomicforces.How important theAssociationof SoutheastAsian Na-

tions(ASEAN) andotherpolicyinitiatives areindirectingcommerce shouldbecome

cleareras theeconomiccrisisinAsia unfolds.

Also indicativeof regionalism's growthare theincreasingratesat whichPTAs

formed and statesjoinedthemthroughout thepost-World WarII period.55Figure1

reports thenumberofregionaltrading arrangements notified

to theGeneralAgree-

mentonTariffs andTrade(GATT)from1948to 1994.Clearly,thefrequency ofPTA

formation has fluctuated.

Few wereestablishedduringthe1940sand 1950s,a surge

inpreferential agreementsoccurredinthe1960sand1970s,andtheincidenceofPTA

creationagaintrailedoffin the1980s.56Buttherehasbeena significant risein such

agreements duringthe1990s; and morethan50 percentof all worldcommerceis

currently conductedwithinPTAs.57Indeed,theyhavebecomeso pervasivethatall

buta fewpartiesto theWorldTradeOrganization (WTO) now belongto at least

one.58

Regionalism, then,seemsto have occurredin twowavesduringthepost-World

WarII era. The firsttookplace fromthelate 1950s through the 1970s and was

markedby theestablishment of theEEC, EFTA, theCMEA, and a plethoraof re-

gionaltradeblocs formedby developingcountries. These arrangements wereiniti-

ated againstthebackdropof theCold War,therashof decolonization following

WorldWarII, and a multilateral commercial framework, all of whichcoloredtheir

economicand politicaleffects. VariousLDCs formedpreferential arrangements to

reducetheireconomicand politicaldependenceon advancedindustrial countries.

Designedtodiscourage imports andencourage thedevelopment ofindigenous indus-

tries,sucharrangements fostered atleastsometradediversion.59 Moreover, manyof

themwerebesetbyconsiderable conflictoverhowtodistribute thecostsandbenefits

stemming fromregionalintegration, how to compensatedistributional losers,and

how to allocateindustriesamongmembers.60 theCMEA represented

Similarly, an

attempt by theSovietUnionto promoteeconomicintegration amongitspolitical

allies,fosterthedevelopment oflocal industries,

andlimiteconomicdependence on

theWest.Ultimately, itdidlittletoenhancethewelfareofparticipants.61 In contrast,

theregionalarrangements concludedamongdevelopedcountries-especially those

inWestern Europe-are widelyviewedas trade-creatinginstitutionsthatalso contrib-

utedtopoliticalcooperation.62

55. Mansfield1998.

56. See also de Melo andPanagariya1993,3.

57. Serraetal. 1997,8, fig.2.

58. WorldTradeOrganization 1996,38, and 1995.

59. Forexample,Pomfret 1988,138.

60. See Bhagwati1993;andForoutan1993.

61. Indeed,somescholarshavegoneso faras to characterize theCMEA as tradedestroying.

See, for

example,Pomfret 1988,94-95, 143.

62. For analysesof tradecreationand tradediversionin Europe,see Eichengreen

andFrankel1995;

FrankelandWei 1998;andPomfret 1988,128-35.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 601

35

30

?25 --

H

10 1 111 I

0-

1948-54 1955-59 1960-64 1965-69 1970-74 1975-79 1980-84 1985-89 1990-94

Source:WorldTradeOrganization

1995.

Note:Eachpreferential

trading is listedintheyearitwas signed.

arrangement

FIGURE 1. The numberofpreferentialtradingarrangementsnotifiedto the GAT7,

1948-94.

The mostrecentwaveofregionalism has arisenin a different

contextthanearlier

episodes.It emergedin thewake of theCold War's conclusionand theattendant

changesin interstate

powerandsecurity relations. Furthermore,theleadingactorin

theinternational

system(theUnitedStates)is activelypromotingandparticipatingin

theprocess.PTAsalso havebeenusedwithincreasing tohelpprompt

regularity and

consolidateeconomicandpoliticalreforms in prospectivemembers, a rarityduring

prioreras.Andunliketheinterwar period,themostrecentwave ofregionalism has

beenaccompanied byhighlevelsofeconomicinterdependence, a willingnessbythe

majoreconomicactorstomediatetradedisputes, anda multilateral(thatis,theGATT/

WTO) framework thatassiststhemin doingso and thathelps to organizetrade

As RobertZ. Lawrencenotes,

relations.63

The forcesdrivingthecurrent developments differradicallyfromthosedriving

previouswavesofregionalism in thiscentury.Unliketheepisodeofthe1930s,

thecurrentinitiativesrepresenteffortstofacilitate

theirmembers' in

participation

theworldeconomyrather thantheirwithdrawal fromit.Unlikethosein the

1950sand 1960s,theinitiatives involving developing countriesarepartofa

to liberalizeandopentheireconomiestoimplement

strategy andforeign-

export-

investment-ledpoliciesratherthantopromote importsubstitution.64

63. PerroniandWhalley1996.

64. Lawrence1996,6. On thedifferences in the1930sandin thecontemporary

betweenregionalism

andFrankel1995;Oye 1992;andPomfret

era,see also Eichengreen 1988.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

602 International

Organization

Ourbriefhistorical

overviewindicatesthatregionalism hasbeenan enduring fea-

tureoftheinternational

politicaleconomy, butbothitspervasiveness andcasthave

changedovertime.We arguethatdomesticand international politicsare centralto

explainingsuchvariationsas well as theoriginsand natureof thecurrent wave of

regionalism.

In whatfollows,we present a seriesofpoliticalframeworks foraddress-

ingtheseissuesandraisesomeavenuesforfurther research.

DomesticPoliticsand Regionalism

Although itis frequently

acknowledged thatpoliticalfactorsshaperegionalism,sur-

prisingly

few systematic attemptshave been made to addresswhichfactorsmost

fullydetermine whystateschoosetopursueregionaltradestrategies andtheprecise

natureoftheireffects.

Earlyeffortsto analyzethepoliticalunderpinningsofregion-

alismwereheavilyinfluenced by "neofunctionalism."65 JosephS. Nye pointsout

that"whatthesestudieshadincommonwas a focuson thewaysin whichincreased

transactionsandcontacts

changedattitudes andtransnationalcoalitionopportunities,

and thewaysin whichinstitutionshelpedto fostersuchinteraction."66 Lately,ele-

mentsof neofunctionalism have been revived,especiallyin researchon European

integration.

Manysuchanalysesconcludethatincreased economicflowsamongmem-

bersof theEU have changedthepreferences of domesticactors,leadingthemto

pressforpoliciesandinstitutions

thatpromote deeperintegration.67

Societal Factors

As neofunctionalstudiesindicate,

thepreferences andpoliticalinfluence ofdomestic

groupscan affectwhyregionalstrategiesareselectedandtheirlikelyeconomiccon-

sequences.Regionaltradeagreements discriminate againstthirdparties,yielding

rentsforcertaindomesticactorswhomayconstitute a potentsourceofsupport fora

PTA's formation and maintenance.68Industries thatcouldwardoffcompetitors lo-

catedin thirdpartiesor expandtheirshareof international marketsif theywere

coveredbya PTAhaveobviousreasonstopressforitsestablishment.69 So do export-

orientedindustries

thatstandto benefitfromthepreferential access to foreignmar-

ketsaffordedbya PTA.In addition, thoughitis all butimpossibletoconstruct a PTA

thatwouldnotadverselyaffectat least some politicallypotentsectors,it is often

65. See, forexample,Deutschetal. 1957;Haas 1958;andNye 1971.

66. Nye 1988,239.

67. For example,SandholtzandZysmanarguethatthe1992 projectin Europeto "completethein-

ternalmarket" resulted

froma confluenceofleadershipbytheEuropeanCommission andpressurefroma

transnational

coalitionofbusinessinfavorofa Europeanmarket. Friedenadvancesa similarargument in

explainingsupportfortheEuropeanMonetary Union,stressingthesalienceofthepreferences

ofEuropean-

orientedbusinessand financialactors.Moravcsikalso viewstheoriginsof Europeanintegrationas re-

sidingin thepressuresexertedby Europeanfirmsand industries withan externalorientationforthe

creation

ofa largermarket.See SandholtzandZysman1989;Frieden1991;andMoravcsik1998.

68. See Gunter1989,9; andHirschman 1981.

69. Forexample,Haggard1997.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 603

possibleto excludethemfromthearrangement, a tack,forexample,thatled to "the

EuropeanEconomicCommunity's exclusionof agriculture (and,in practice,steel

and manyothergoods), theCaribbeanBasin Initiative'sexclusionof sugar,and

ASEAN's exclusionofjustabouteverything ofinterest."70

Regionaltradestrategies, therefore,hold some appeal forpublicofficialswho

needtoattract thesupportofbothimport-competing andexport-oriented sectors.The

domesticpoliticalviabilityofa prospective PTA,theextenttowhichitwillcreateor

diverttrade,andtherangeofproducts itwillcoverhingepartly on thepreferences of

andtheinfluence wieldedbykeysectorsin eachcountry as wellas theparticularset

ofcountries thatcanbe assembledtoparticipate init.Unfortunately, existingstudies

offerrelatively fewtheoretical orempirical insights intotheseissues,although some

recentprogress hasbeenmadeon thisfront.

Publicofficialsmuststrikea balancebetweenpromoting a country'saggregate

economicwelfareand accommodating interest groupswhosesupportis neededto

retainoffice. GeneM. Grossman andElhananHelpmanarguethatwhether a country

choosesto entera regionaltradeagreement is determined by how muchinfluence

different interestgroupsexertand how muchthegovernment is concernedabout

voters'welfare.71Theydemonstrate thatthepoliticalviabilityof a PTA oftende-

pendson theamountof discrimination it yields.Agreements thatdiverttradewill

benefit certaininterestgroupswhilecreating costsbornebythepopulaceatlarge.If

thesegroupshavemorepoliticalcloutthanothersegments thena PTAthat

ofsociety,

is tradediverting standsa betterchanceof beingestablished thanone thatis trade

creating.72 GrossmanandHelpmanalso findthatby excludingsomesectorsfroma

PTA,governments can increasethedomesticsupport forit,thushelpingto explain

whymanyPTAsdo notcoverpolitically sensitive industries.Consistent withearlier

research, theirresultsimplythattrade-diverting PTAs will facefewerpoliticalob-

staclesthantrade-creating ones.73If so, usingpreferential arrangements as building

blocksto support liberalization

multilateral willrequiresurmounting substantialdo-

mesticimpediments.

Opinionis dividedovertheease withwhichthiscanbe accomplished. Kenneth A.

Oye arguesthatdiscriminatory PTAscan actuallylaythebasisforpromoting multi-

lateralopenness,especiallyiftheinternational trading systemis relativelyclosed.74

In his view,discrimination stemming froma preferential arrangement can mobilize

and strengthen thepoliticalhandofexport-oriented in-

(and otherantiprotectionist)

terestslocatedin thirdparties,thereby generating domesticpressurein thesestates

foragreements thatexpandtheiraccesstoPTAmembers' markets.Suchagreements,

inturn, arelikelytocontribute tointernational openness.However, Anne0. Krueger

maintainsthattheformation and expansionof PTAs maydampenthesupportof

exporters forbroaderliberalization.

As sheputsit,"For thoseexporters whowould

70. EichengreenandFrankel1995,101.

71. GrossmanandHelpman1995,668; and 1994.

72. GrossmanandHelpman1995,681. See also Pomfret

1988,190.

73. Forexample,Hirschman 1981,271.

74. Oye 1992,6-7, 143-44.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

604 International

Organization

supportfreetrade,thevalueoffurther multilateraltradeliberalization is diminished

witheverynewentrant intoa preferential tradearrangement, so thatexporters' sup-

portformultilateral liberalizationis likelyto diminishas vestedinterests profiting

fromtradediversion increase."75 Hence,itis notclearwhether exporters willsupport

regionalism insteadoforinadditiontomultilateral liberalization.

Equallyunclearis whyexporters wouldpreferto liberalizetradeon a regional

ratherthana multilateral basisinthefirst place.One possibility is thatexporters will

be morelikelyto support regionalstrategies iftheyoperatein industries character-

izedbyeconomiesofscale,since,byprotecting thesesectorsfromforeign competi-

tionand broadening theirmarketaccess,theformation of a PTA can bolstertheir

competitiveness. Indeed,Milnerarguesthatfirmsin such industries maybe key

proponents of regional,ratherthanunilateralor multilateral, tradepolicies.76But

because PTAs also liberalizetradeamongparticipants, firmswithcompetitors in

prospectivemember countries mayseektobarthesestatesfromentering an arrange-

mentoropposeitsestablishment altogether.

Thoughresearchstressing theeffects ofsocietalfactorsonregionalism offersvari-

ous usefulinsights,italso suffersfromatleasttwodrawbacks. First,thereis a lackof

empiricalevidenceindicating whichdomesticgroupssupport regionaltradeagree-

ments,whoseinterests theseagreements serve,and whyparticular groupsprefer

regionalto multilateral liberalization. For example,Oye maintains thatdiscrimina-

toryarrangements piquedtheinterest ofexporters, andMilnerclaimsthatexporters-

particularlythosewithlargescale economies-mayhavefavoredand gainedfrom

NAFTA.77 Neither, however, demonstrates thatexporterspreferred regionalarrange-

mentsto multilateral ones.Regionalliberalization mayhavebeenwhattheyhad to

settleforgiventheexistenceof strong,opposingdomesticinterests. Second,we

knowlittleaboutwhether, onceinplace,regionalarrangements foster domesticsup-

portforbroader,multilateral tradeliberalization or whether theyundermine such

support.Theseissuesoffer promising avenuesforfuture research.

DomesticInstitutions

In thefinalanalysis,thedecisiontoentera PTAis madebypolicymakers. Boththeir

preferences andthenatureofdomesticinstitutionsconditiontheinfluence ofsocietal

actorson tradepolicyas wellas independently whether

affecting stateselectto em-

barkon regionaltradeinitiatives. Of course,policymakers and politicallypotent

societalgroupssometimes sharean interestin forminga PTA. Manyregionaltrade

arrangements thatLDCs establishedduringthe1960sand 1970s,forinstance, grew

outofimport-substitutionpoliciesthatwereactivelypromoted bypolicymakers and

stronglysupported byvarioussegments ofsociety.78

75. Krueger1997,19 fn.27.

76. Milner1997.See also BuschandMilner1994.

77. See Milner1997;andOye 1992.

78. See, forexample,Krueger1993,77, 87; andNoguesandQuintanilla1993,280-88.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

New WaveofRegionalism 605

However,PTAs also havebeencreatedbypolicymakers whopreferred toliberal-

ize tradebutfaceddomesticobstaclesto doingso unilaterally. In thisvein,Barry

Eichengreen andJeffrey A. Frankelpointoutthat"ColumbiaandVenezueladecided

in November1991 to turnthepreviously moribund AndeanPact intowhatis now

one of theworld'smostsuccessfulFTAs. Policymakers in thesecountries explain

theirdecisionas a politically

easywaytodismantle protectionist

barrierstoan extent

thattheirdomesticlegislatures wouldneverhave allowedhad thepolicynotbeen

pursuedina regionalcontext."79 Evenifinfluentialdomesticactorsopposecommer-

cial liberalization institutional

altogether, factorssometimes createopportunitiesfor

policymakers to sidestepsuchoppositionby relyingon regionalor bilateraltrade

strategies.Considerthesituation NapoleonIII facedon theeve oftheAnglo-French

commercial arrangement. Anxiousto liberalizetradewithGreatBritain, he encoun-

tereda Frenchlegislature andvarioussalientdomesticgroupsthatwerehighlypro-

tectionist.Butalthough thelegislature

hadconsiderable controloverunilateral trade

policy,theconstitution of 1851 permittedtheemperor to signinternationaltreaties

without thisbody'sapproval.Napoleon,therefore, was able to skirtwell-organized

protectionistinterests muchmoreeasilybyconcluding a bilateralcommercial agree-

mentthatwould have been impossiblehad he reliedsolelyon unilateralinstru-

ments.80

Similarly,governments thatproposea programof liberaleconomicreforms and

encounter (or expectto encounter) domesticoppositionmayentera PTA to bind

themselves to thesechanges.8" Mexico's decisionto enterNAFTA,forexample,is

frequentlydiscussedin suchterms. As onerecentstudyconcludes,"NAFTAshould

be understood as a commitment device .. ., [which]combinedwiththeinfluence of

new elitesthatbenefit fromexportpromotion, greatlyincreasesthelikelihoodthat

tradeliberalizationinMexicowillnotbe derailed."82 Fora statethatis interestedin

makingliberaleconomicreforms, theattractivenessof lockingthemin through an

externalmechanism, suchas joininga PTA,is likelyto growifinfluential segments

of societyoppose reforms and if domesticinstitutions renderpolicymakers espe-

ciallysusceptibleto societalpressures.Undertheseconditions, however,govern-

mentsmusthavetheinstitutional meansto circumvent domesticopposition in order

to entersuchagreements, and thecostsof violatinga PTA mustbe highenoughto

ensurethatreforms willnotbe abrogated.

Although governments maychoosetojoinregionalagreements topromote domes-

ticreforms, theymayalso do so if theyresistreforms butare anxiousto reapthe

benefitsstemming from accesstoothermembers'

preferential markets.Existing mem-

bersof a preferential groupingmaybe able to influencethedomesticeconomic

79. Eichengreen andFrankel1995,101.

80. See Irwin1993,96; and Kindleberger1975,39-40. Moreover,thisis notan isolatedcase. Irwin

notesthat"Commercial agreements intheformofforeigntreaties

provedusefulincircumventing protec-

tionist

interests

inthelegislature Europe."Irwin1993,116fn.7.

throughout

81. See de Melo,Panagariya,andRodrik1993;Haggard1997;Summers1991;andWhalley1998.

82. Tomelland Esquivel 1997,54. See also Whalley1998,71-72. Thatthisarrangement helpedto

consolidateMexicaneconomicreforms its desirability

probablyheightened fromthestandpoint of the

UnitedStatesandCanadaas well.See, forexample,EichengreenandFrankel1995,101.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

606 International

Organization

policiesandthepoliticalinstitutions ofprospective members bydemanding thatthey

institute domesticreforms priorto accession.Alongtheselines,thereare various

cases wherePTAshavemadetheestablishment ofdemocracy a necessary condition

formembership. Both Spain and Portugalwererequiredto completedemocratic

transitions beforebeingadmitted to theEC; indeed,L. Alan Wintersarguesthat

solidifying democracy in thesestatesas wellas in Greecewas a chiefreasonforthe

EC's southern expansion.83 Similarly,Argentina andBrazilinsistedthata democratic

systemofgovernment wouldhavetobe established inParaguaybeforeitcouldenter

Mercosur.84 Morerecently, theEU hasindicated thatvariousEasternEuropeancoun-

triesmustconsolidatedemocratic reforms as one preconditionformembership. As

Raquel Fernandezmentions, "Both theEU and theCEE [CentralEast European]

countries wantedto lockin a politicalcommitment to democracy in theCEE coun-

tries;sincethepromiseof eventualEU membership impliedin theAgreements ...

was conditional on thecontinued democratization oftheCEE countries, thecostof

exitto thesecountries as a consequenceofreversion to authoritarianism

wouldnot

justbe theloss ofbenefits, ifany,oftheAgreements, buttheloss oftheprospectof

EU membership."85 Another studyechoesthisview,notingthata keymotivebehind

anyfuture eastward expansionoftheEU wouldbe fostering democracy intheformer

members oftheWarsawPact.86Clearly,we arenotsuggesting thatthedesiretogain

accessto a PTAhasbeena primary forcedriving democratization inEasternEurope

or elsewhere.However,recentexperience suggeststhatitcan sometimes be fruitful

toincludesuchaccessin a packageofinducements designedto spurpoliticalreform

innondemocratic states.

UsingPTA membership to stimulateliberaleconomicand politicalreforms is a

distinctive featureof thelatestwave of regionalism. Thatthesereforms havebeen

designedto openmarkets andpromote democracy mayhelpto accountfortherela-

tivelybenigncharacter of thecurrent wave. Underlying demandsfordemocratic

reform are fearsthatadmitting nondemocratic countries mightundermine existing

PTAs composedof democraciesand thebeliefthatregionscomposedof stablede-

mocraciesareunlikely toexperience Bothviewsremainopentoquestion.

hostilities.

But if entering a preferential arrangement actuallypromotestheconsolidation of

liberaleconomicandpoliticalreforms andmutestheeconomicandpoliticalinstabil-

itythatoftenaccompaniessuchreforms, thenthecontemporary riseofregionalism

maycontribute tobothcommercial opennessandpoliticalcooperation.87

Atthesametime,thepoliticalviability ofsuchPTAs,thecredibility oftheinstitu-

tionalchangestheyprompt, and theeffectof thesearrangements on international

opennessandcooperation dependheavilyon thepreferences of powerful domestic

groups.Whereasdomesticanalysesofregionalism havegenerally focusedon either

83. Winters1993,213.

84. Birch1996,186.

85. Femrnndez 1997,26.

86. Eichengreen andFrankel1995,103.

87. On theseissues,see HaggardandKaufman1995;HaggardandWebb1994;Lawrence1996;Mans-

fieldandSnyder1995;andRemmer1998.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 607

societalorinstitutional factors,moreattention needstobe centered on howtheinter-

actionbetweenthesefactors influences whether andwhencountries entera regional

arrangement as well as on thepoliticaland economicconsequencesof doingso.88

Greaterattention also needsto be focusedon whystateleadershave displayeda

particularpreference forentering regionaltradearrangements. One possibility is that

theydo so to liberalizetradewhenfacedwithdomesticobstaclesto reducingtrade

barriers on a unilateral ormultilateral basis.Theoriesoutlining theconditions under

whichleadersprefer toliberalizecommerce inthefirstplace,however, remainscarce.

Furthermore, theextent towhichPTAshavebeenusedas instruments forstimulat-

ingeconomicand politicalliberalization duringthecurrent wave of regionalism is

quiteunusualbyhistorical standards. Chile,forexample,withdrew fromtheAndean

Pact in 1976 becauseit wantedto completea seriesof economicreforms thatthis

arrangement prohibited.89 Moreover, attempts tospurdemocratization inprospective

PTA membersare largelyuniqueto thecontemporary wave.As notedearlier,the

recenttendencyof existingPTAs to demandthatnondemocratic statescomplete

politicalreforms priortoaccessionprobably reflects

thegrowing number ofpreferen-

tialarrangements composedofdemocracies andthewidelyheldbeliefbypolicymak-

ers in theseregionalgroupings thatfostering democracywill promotepeace and

prosperity.Nonetheless, we lacka sufficient theoretical

understanding ofthecondi-

tionsunderwhichPTA membership is used to promptliberalizing reforms and the

factors affecting thesuccessofsuchefforts.

A relatedlineofresearchsuggeststhatthesimilarity ofstates'politicalinstitutions

influences whether theywill forma preferential arrangement and itsefficacy once

established. Manyscholarsviewa regionas implying substantial institutional

homo-

geneityamongtheconstituent states.Likewise,some observersmaintainthatthe

feasibilityofcreating a regionalagreement dependson prospective members having

relativelysimilareconomicorpoliticalinstitutions.90 If tradeliberalizationrequires

harmonization in a broadsense,suchas in theSingleEuropeanAct,thenthemore

homogeneous are members'nationalinstitutions, theeasierit maybe forthemto

agreeoncommonregionalpoliciesandinstitutions. Otherspointoutthatcountries in

close geographic proximity have muchless impetusto establishregionalarrange-

mentsiftheirpoliticalinstitutions differ In Asia,forexample,thescar-

significantly.

cityofregionaltradearrangements is partlyattributableto thewidevariation in the

constituent states'politicalregimes,whichrangefromdemocracieslike Japanto

autocracies likeVietnamandChina.91

As theinitialdifferences in states'institutionsbecomemorepronounced, so do

boththepotential gainsfromand theimpediments to concludinga regionalagree-

ment.Consequently, thedegreeofinstitutional similarityamongstatesandthepros-

pectthatmembership in a regionalarrangement willprecipitate institutional

change

88. Forone studyofthissort,see de Melo,Panagariya,

andRodrik1993.

89. Nogu6sandQuintanilla 1993,285.

90. Forexample,ibid.

91. Katzenstein

1997a.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

608 International

Organization

inthesestatesmaybearheavilyon whether theyforma PTA.92The extantliterature,

however,provideslittleguidanceabouthow largeinstitutional

differencescan be

beforeregionalintegration

becomespolitically

infeasible.

Nordoesitindicatewhether

regionalagreementscanhelpmembers tolockininstitutional

reforms ifthereis little

preexisting

domesticsupport forthesechanges.

International

Politicsand Regionalism

The decisionto forma PTA restspartlyon thepreferences and politicalpowerof

varioussegments ofsociety,

theinterestsofstateleaders,andthenatureofdomestic

institutions.

In theprecedingsection,we suggestedsome ways thatthesefactors

mightoperateseparately and in combinationto influencewhether statespursuere-

gionaltradestrategies

andregionalism's economicconsequences.But statesdo not

makethedecisionto entera PTA in an international politicalvacuum.On thecon-

interstate

trary, powerandsecurity relations

as well as multilateral have

institutions

playedkeyrolesin shapingregionalism. Equallyimportant is how regionalismaf-

fectspatterns

ofconflictandcooperation amongstates.We nowturntotheseissues.

PoliticalPower,Interstate andRegionalism

Conflict,

Studiesaddressing thelinksbetweenstructural powerandregionalism haveplaced

primary stresson theeffects ofhegemony. Variousscholarsarguethatinternational

economicstability is a collectivegood,suboptimal amountsof whichwillbe pro-

videdwithout a stablehegemon.93 Discriminatory tradearrangements, in turn,may

be outgrowths of theeconomicinstability fostered by thelack or declineof sucha

country.94

Offering one explanation forthetrade-diverting character ofPTAs during

theinterwarperiod,thisargument is also invokedbymanyeconomists whomaintain

thatthecurrent wave of regionalism was triggered or acceleratedby theU.S. deci-

sionto pursueregionalarrangements in theearly1980s,once itseconomicpower

wanedandmultilateral tradenegotiations In fact,thereis evidencethatover

stalled.95

thepastfiftyyearstheerosionofU.S. hegemony has stimulated a riseinthenumber

ofPTAs andstatesentering them.96Butwhywaninghegemony has beenassociated

withthegrowthof regionalism sinceWorldWarII, whateffects PTAs formedin

responseto declininghegemony will have on themultilateral tradingsystem,and

whether variationsin hegemony contributed to earlierepisodesof regionalism are

issuesthatremainunresolved.97

92. Forexample,Hurrell1995,68-71.

93. See Gilpin1975;Kindleberger1973;andLake 1988.

94. See, forexample,Gilpin1975and 1987;Kindleberger

1973;andKrasner1976.

95. See, forexample,Baldwin1993;Bhagwati1993;BhagwatiandPanagariya1996;Krugman1993;

andPomfret 1988.

96. Mansfield1998.

97. See, forexample,McKeown1991;Oye 1992;andYarbrough andYarbrough

1992.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 609

Some observers arguethatas a hegemon'spowerrecedes,ithas reasontobehave

in an increasingly

predatory manner.98 To buffer theeffects of suchbehavior,other

statesmightforma seriesofpreferential tradingblocs,thereby offa wave of

setting

regionalism.RobertGilpinsuggeststhatthissortofprocessbeganto unfoldduring

the1980s,givingrisetoa systemoflooseregionaleconomicblocsthatis coalescing

aroundWestern Europe,theUnitedStates,andJapan.He also pointsoutthatbecause

of theinherentproblemsof "pluralist"leadership, thesedevelopments threatenthe

unityoftheglobaltrading order,a prospectthatrecallsKrugman'sclaimsaboutthe

adverseeffectson globalwelfarestemming fromsystemscomposedof threetrade

blocs.99Theextent towhichU.S. hegemony hasactuallydeclinedandwhether sucha

systemis actuallyemerging, however, remainthesubjectsoffiercedisagreement.

Furthermore, evenifsucha systemis emerging, thereareatleasttworeasonswhy

thesituationmaybe less direthantheprecedingaccountwouldindicate.First,de-

spitethepotential problemsof pluralistleadership, it is widelyarguedthatglobal

opennesscanbe maintained inthefaceofdeclining (ortheabsenceof)hegemony ifa

smallgroupof leadingcountries collaborates to supportthetradingsystem.100 The

erosionofU.S. hegemony mayhavestimulated thecreationandexpansionofPTAs

bya setofleadingeconomicpowersthatfeltthesearrangements wouldassistthem

in managingtheinternational economy.101 Drawingsmallerstatesintopreferential

groupings witha relativelyliberalcasttowardthird partiesmightreducethecapacity

of thesestatesto establisha seriesof moreprotectionist blocs and bindthemto

decisionsaboutthe systemmade by theleadingpowers.Especiallyif thereis a

multilateral

framework (liketheGATT/WTO)towhicheachleadingpower(includ-

ing thedeclininghegemon)is committed and thatcan help to facilitateeconomic

cooperation,thegrowthof regionalism duringperiodsof hegemonicdeclinecould

contributetothemaintenance ofan opentrading system.

Second,Krugmanarguesthatthedangersposedby a systemof threetradeblocs

are mutedif each bloc is composedof countries in close proximity thatconducta

highvolumeofcommerce priortoitsestablishment. Bothhe andSummers conclude

thatthese"natural"trading blocs reducetheriskof tradediversionand thatthey

makeup a largeportion oftheexisting PTAs.102Regardlessofthisargument's merits,

98. Forexample,Gilpin1987,88-90,andchap.10.

99. See ibid.;andKrugman1991aand 1993.On theproblemsassociatedwithpluralist leadership, see

also Kindleberger 1973.

100. See, forexample,Keohane1984;andSnidal1985.

101. On thisissue,see Yarbrough andYarbrough1992.

102. Krugman1991aand 1993; andSummers1991.Of course,thesefactorsmaybe related,sincean

inverserelationship costsandtradeflows.However,somestrands

tendstoexistbetweentransportation of

thisargument focuson highlevelsoftrade,whichmaybe a productofgeographical proximity, whereas

othersfocuson transportation costs,whichareexpectedtobe lowerforstatesin thesameregionthanfor

otherstates.See BhagwatiandPanagariya1996,7 fn.7. Wonnacott andLutz,whofirst coinedtheterm

"naturaltradingpartners," arguethatthe economicdevelopment of states,the extentto whichtheir

economiesarecomplementary, andthedegreeto whichtheycompetein international markets also influ-

encewhether trading arenatural.

partners Thesefactors,

however, havereceivedrelatively littleattention

andwe therefore do notexaminethemhere.See Wonnacott andLutz 1989.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

610 International

Organization

whichhavebeenhotlydebatedby economists,103 it begs an important setof ques-

tions:Whydo some "natural"tradepartners formPTAs whileothersdo not?And

whydo some "unnatural" partnersdo so as well?Thereis amplereasonto expect

thattheanswerstothesequestionshingelargelyon domesticpoliticalfactors andthe

natureofpoliticalrelations betweenstates.

Centralto thelinksbetweeninternational politicalrelationsandtheformation of

PTAs are theeffectsof tradeon states'political-military power.104JoanneGowa

pointsoutthattheefficiency gainsfromopentradepromotethegrowth of national

income,whichcanbe usedtoenhancestates'political-military capacity.105Countries

cannotignorethesecurity externalities

stemming fromcommerce without jeopardiz-

ingtheirpoliticalwell-being.She maintains thatcountriescan attendto theseexter-

nalitiesby tradingmorefreelywiththeirpolitical-military allies thanwithother

states.SincePTAsliberalizetradeamongmembers, Gowa's argument suggeststhat

sucharrangements areespeciallylikelyto formamongallies.In PTAs composedof

allies,thegainsfromliberalizingtradeamongmembers bolsterthealliance'soverall

political-military

capacity,andthecommonsecurity aimsofmembers attenuate the

politicalrisksthatstatesbenefitingless fromthearrangement mightotherwise face

fromthosebenefiting more.

Returning to theclaimsadvancedby Krugmanand Summers, certainblocs (for

example,thosein NorthAmericaandWestern Europe),therefore, mayappearnatu-

ral partlybecause theyare composedof allies,whichtendto be locatedin close

proximity and to tradeheavilywitheach other.106Furthermore, allies maybe quite

willingto formPTAs thatdiverttradefromadversaries lyingoutsidethearrange-

ment,iftheyanticipate thatdoingso willimposegreater economicdamageon their

foesthanon themselves. In thesamevein,adversaries havefewpoliticalreasonsto

forma PTA,and allies thatestablishone areunlikelyto permittheiradversaries to

join, thuslimiting thescope fortheexpansionof preferential arrangements. Either

situation couldundermine thesecurity

ofmembers, sincesomeparticipants arelikely

to derivegreatereconomicbenefits thanothersevenifall of themrealizeabsolute

gainsin welfare.It is no coincidence,forinstance,thatpreferential agreements be-

tweentheEC/EU and EFTA, on theone hand,and variousstatesformerly in the

Sovietorbit,on theother, wereconcludedonlyaftertheendoftheColdWarandthe

103. BhagwatiandPanagariya, forexample,havelodgedseveralcriticisms againstit.First,thereare

no clearempiricalstandards forgaugingwhether a givenpairof tradepartners is natural.Second,they

challengethe assumption thathightradevolumesamongnaturaltradepartners implythatlow trade

volumesexistamong"unnatural" partners,

thereby limitingthescopefortradediversion. Third,a high

initialleveloftradebetweenstatesneednotemanatefromeconomiccomplementarities; instead,itmight

stemfrompreexisting patterns If so, thesestatesmaynotbe naturaltradepartners,

ofdiscrimination. and

anyPTA theyestablishmaynotbe tradecreating. See Bhagwati1993,34-35; andBhagwatiand Pana-

gariya1996.

104. On therelationshipbetweentradeandpoliticalpower,see Baldwin1985;Gowa 1994;Hirschman

[1945] 1980;andKeohaneandNye 1977.

105. Gowa 1994.

106. On therelationship betweenalliancesand proximity, see Farberand Gowa 1997,411. On the

relationshipbetweenalliancesandtrade,see Gowa 1994;andMansfield andBronson1997.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NewWaveofRegionalism 611

collapseof theWarsawPact.107Also, althoughdeeppoliticaldivisionscontinueto

existin variouspartsof the world,thelack of competingmajorpoweralliances

mayhelpto accountfortherelatively benigneconomiccast of thelatestwave of

regionalism.

Another waythatregionalarrangements can affect

powerrelations is byinfluenc-

ingtheeconomicdependence ofmembers. Ifstatesthatderivethegreatest economic

gainsfroma PTA aremorevulnerable to disruptionsofcommercial relations within

thearrangement thanotherparticipants, thepoliticalleverageofthelatteris likelyto

grow.Thispointhasnotbeenloston stateleaders.

Prussia,forexample,establishedtheZollvereinlargelyto increaseits political

influence overtheweakerGermanstatesand to minimize Austrianinfluence in the

region.108As a result,

itrepeatedly opposedAustria'sentry intotheZollverein.Simi-

larly,bothGreatBritainandPrussiaobjectedtotheformation ofa proposedcustoms

unionbetweenFranceand Belgiumduringthe 1840son thegroundsthatit would

promoteFrenchpowerand undermine Belgianindependence. As Vinerpointsout,

"Palmerston tookthepositionthateveryunionbetweentwocountries incommercial

matters mustnecessarily tendtoa community ofactioninthepoliticalfieldalso,but

thatwhensuchcommunity is established betweena greatpoweranda smallone,the

will of thestronger mustprevail,and thereal and practicalindependence of the

smallercountry willbe lost."109Furthermore, Albert0. Hirschman andothershave

describedhow variousmajorpowersused regionalarrangements to bolstertheir

politicalinfluenceduringthe interwar periodand how certainarrangements that

seemedlikelyto bearheavilyon theEuropeanbalanceofpower(liketheproposed

Austro-German customsunion)wereactivelyopposed.110

Since WorldWarII, stronger stateshave continuedto use PTAs as a meansto

consolidatetheirpoliticalinfluence overweakercounterparts. The CMEA and the

manyarrangements thattheEC established withformer coloniesofitsmembers are

cases inpoint.The CaribbeanBasinInitiative launchedbytheUnitedStatesin 1982

hasbeendescribed in similarterms.111A relatedissueis raisedbyJosephM. Grieco,

whoarguesthat,overthepastfifty years,theextentofinstitutionalization inregional

arrangements has beeninfluenced by powerrelationsamongmembers.112 In areas

wherethelocal distribution ofcapabilities has shiftedorstateshaveexpectedsucha

shifttooccur,weakerstateshaveopposedestablishing a formalregionalinstitution,

fearing thatitwouldreflect theinterests ofmorepowerful members andundermine

theirsecurity.Another view,however, is thatregionalinstitutions

fosterstability

and

constrain theabilityof membersto exercisepower.A recentstudyof theEU, for

example,concludesthatalthoughGermany'spowerhas enabledit to shapeEuro-

107. Fora listofthesearrangements,

see WorldTradeOrganization1995,85-87.

108. Viner1950,98.

109. Ibid.,87.

110. See, forexample,Condliffe1940;Hirschman [1945] 1980;Viner1950,87-91; andEichengreen

andFrankel1995,97.

111. Forexample,Pomfret 1988,163.

112. Grieco1997.

This content downloaded from 148.61.13.133 on Sun, 29 Sep 2013 21:54:34 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

612 International

Organization

pean institutions,Germany'sentanglement withintheseinstitutions has takenthe

hardedgeoffitsinterstate bargaining anderodeditshegemony inEurope.113

The linksbetweenpowerrelationsandPTAs remainimportant in thecontempo-