Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1987 A Neuropsychological Hypothesis Explaining Posttraumatic - Kolb

Uploaded by

Luana SouzaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1987 A Neuropsychological Hypothesis Explaining Posttraumatic - Kolb

Uploaded by

Luana SouzaCopyright:

Available Formats

Special Articles

A Neuropsychological Hypothesis Explaining

Posttraumatic Stress Disorders

Lawrence C. Koib, M.D.

minants or early traumatic experiences? In short, are

The author reports findings from recent the phenomena of the stress disorders only reflections

psychophysiological and biochemical research on of psychological processing of information signifying

Vietnam combat veterans with chronic posttraumatic existential threat, or are they representative of other

stress disorder. Applying these data and the analogy (possibly preceding) psychopathological and/or neural

of the known functional and structural defects in the changes?

peripheral (cranial) sensory system consequent to

high-intensity stimulation, he hypothesizes that

cortical neuronal and synaptic changes occur in RECENT CLINICAL OBSERVATIONS

posttraumatic stress disorder as the consequence of

excessive and prolonged sensitizing stimulation It is my work over the past 9 years with men who

leading to depression of habituating learning. He have come to suffer the severe forms of chronic

postulates that the “constant” symptoms of the posttraumatic stress disorder that I shall report in this

disorder are due to the changes in the agonistic paper. Due to my World War II clinical experiences in

neuronal system which impair cortical control of diagnosis and treatment of patients with acute combat-

hindbrain structures concerned with aggressive induced posttraumatic stress disorders, it was possible

expression and the sleep-dream cycle. for me to quickly recognize the chronic and delayed

(Am J Psychiatry 1987; 144:989-995) forms of these disorders in many hospitalized men.

The data to be reported here come from personal

examination and engagement in treatment of more

C ontroversy continues to rage over the posttrau- than 300 Vietnam veterans with chronic or delayed

matic stress disorders. Are the symptoms evidence posttraumatic stress disorder, 10 prisoners of war of

only of a consistent process set in motion following World War II, and a sizable number of patients whose

any major threat to one’s security? Does the condition chronic and delayed posttraumatic stress disorder

merit consideration as a clinical entity to be classified from the Korean and World War II conflicts had been

separately in our diagnostic scheme? Are the stress missed-as well as many noncombatant Vietnam-era

disorders merely variants of other personality disor- veterans without posttraumatic stress disorder in hos-

ders? Is massive psychological trauma the etiologic pital in- and outpatient services. The majority of these

agent? May the condition be induced in adulthood patients had experienced long and high-level combat

without preceding genetic and/or constitutional deter- exposure. My impression is that the more disabled

patients, with predominantly dissociative, “catete-

noid,” or psychosomatic symptoms, have come or

Presented in part at the 138th annual meeting of the American

Psychiatric Association, Dallas, May 18-24, 1985. Received July 22,

have been brought to the hospital services for years.

1985; revised June 6 and Sept. 8, 1986; accepted Nov. 3, 1986. Among the earlier and more severely disturbed

From the Department of Psychiatry, Veterans Administration Mcd- patients were a number of men with socially impairing

ical Center, and the Department of Psychiatry, Albany Medical

dissociative states (flashbacks) or panic attacks. Many

College, Albany, N.Y. Address reprint requests to Dr. Kolb, Depart-

indicated the persistence of a startle reaction with

ment of Psychiatry, VA Medical Center, 1 13 Holland Ave., Albany,

NY 12208. associated physiological arousal on exposure to sharp

Supported by NIMH grant MH-37839. sounds produced by helicopters or other explosive

Am ] Psychiatry 1 44:8, August 1987 989

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL HYPOTHESIS

noises. When pushed to describe their combat experi- with and four without psychiatric disorders), 1 1 same-

ence, these men often provided sketchy accounts with- aged university students, and 14 civilians with other

out associated affect. anxiety disorders. Since that study, Blanchard et al. (3)

For 18 of these patients, treatment using a modified have examined a total of 91 combat veterans-57 with

form of narcosynthesis directed at verifying the exist- and 34 without posttraumatic stress disorder.

ence of repressed emotion was initiated to provide All participants took the following psychological

emotional “de-repression.” An audiovisual recording tests: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, Beck Depression

of these patients’ behavior during the treatment was Inventory, and Buss-Durkee Hostility Scale (2). The

made to be used as confrontation in later psychother- veterans scored significantly (p<.OO1) higher than

apy. The narcosynthetic technique was also modified control subjects on all measures, indicating more pa-

to test the existence of a conditioned emotional re- thology.

sponse. Rather than verbal suggestion, which was used The physiological data analyzed to date have yielded

in treatment of severely, acutely disturbed patients the most interesting findings. Analyses of the six

during World War II, each patient was exposed to a physiological responses revealed three statistically sig-

brief train of combat sounds as the initiating stimulus nificant (p<.OO1) differences between the veterans

for abreaction. with posttraumatic stress disorder and the control

Fourteen of the 1 8 men exposed to a moderate- subjects: heart rate, systolic blood pressure, and dias-

intensity combat sound stimulus of 30 seconds while in tolic blood pressure. In each instance the veterans with

arousable pentobarbital anesthesia immediately re- posttraumatic stress disorder showed more arousal in

sponded with time regression and reenacted a Vietnam response to the combat sounds than did the control

combat experience with intense emotional abreaction subjects. The arousal of many men was so distressing

of the affects of fear, rage, indignation, sadness, and personally that they terminated the experiment at low

guilt. No responses were elicited by musical stimuli or levels of sound intensity. The later study (3), using a

by silence, and two noncombat veterans exposed to the single cutoff rate for highest heart rate response fol-

sound train also failed to abreact. The characteristics lowing exposure to combat sounds, found that heart

of this group of men and their responses have been rate response alone accurately identified 40 (70.2%) of

described in some detail elsewhere (1). The emotion- the 57 combat veterans with posttraumatic stress

ality was so evident during abreaction that an effort disorder and 30 (88.2%) of the 34 combat veterans

was made to monitor various physiological systems. without posttraumatic stress disorder. Using this cutoff

No clear-cut abnormalities were discovered in the resulted in only six false-positives among the 34 vet-

subnarcotic state, presumably because the injected erans without the disorder. Four of these false-posi-

drug obscured related organ responses during the tives would have met the diagnostic criteria for

emotional storm. posttraumatic stress disorder in the past and were

therefore considered clinically remitted. Further anal-

ysis using the other physiological measures is now

RECENT PSYCHOPHYSIOLOGICAL RESEARCH underway in this group of veterans.

There are two other reports of psychophysiological

To examine the hypothesis that autonomic arousal assessment of combat veterans with chronic posttrau-

did indeed occur following the startle reactions on matic stress disorder. Dobbs and Wilson (4) compared

exposure to a meaningful sound stimulus reminiscent the psychophysiological responsivity to audiovisual

of combat, I initiated a collaborative study with Prof. stimuli of two groups of World War II veterans with

Edward Blanchard of the Stress Laboratory of the the chronic posttraumatic stress disorder of combat

State University of New York at Albany. Initially, he (13 men considered socially compensated and eight

and his colleagues, Thomas Pallmeyer and Robert men considered socially decompensated some 10 years

Gerardi, exposed 12 combat veterans who met the after their war experiences) with that of a group of 10

operational criteria of DSM-III for posttraumatic noncombatant university students. Increases in pulse

stress disorder to a train of combat sounds of varying and respiratory rate as well as a decrease in alpha

intensity given at varying times and interspersed with rhythm occurred in the vast majority of the combat

periods of music and silence (2). The veterans were in veterans when exposed to the audiovisual stimuli but

a fully conscious state, and their diastolic and systolic not in the control group. Many of the men in the

blood pressure, heart rate, finger-tip skin temperature, socially decompensated group were unable to corn-

and galvanic skin reflex were monitored. In addition to plete the test, leaving the experimental setting before

the combat sounds, the subjects were also exposed to the sound stimulation was completed.

an arousal sound. They were also given an intellectual Malloy et a!. (5) compared the physiological re-

stress test and a variety of standardized psychological sponses of 10 Vietnam combat veterans with posttrau-

tests. Their responses to these instruments were corn- matic stress disorder, 10 noncombat veteran control

pared with those of control subjects tested in precisely subjects, and 10 psychiatric inpatients without post-

the same manner. The control groups consisted of 10 traumatic stress disorder. As stimuli they presented

Vietnam combat veterans without posttraumatic stress both combat-related and noncombat audiovisual

disorder, 16 Vietnam-era noncombat veterans (12 scenes.

990 Am J Psychiatry 144:8, August 1987

LAWRENCE C. KOLB

Physiologically, during exposure to the combat intensities), none was able to do so without arousing

stress scenes the veterans with posttraumatic stress somatic responses. One, angered at his failures, played

disorder showed an increase in heart rate and skin the tape at high intensity on his sound system, disso-

resistance; these increases did not occur in either group ciated cognitively, and in a violent rage tore apart his

of control subjects. Multivariate analyses of the van- workroom. Beyond that, the long-term follow-up of

ous physiological, behavioral, and self-report observa- patients in continuing treatment has demonstrated

tions successfully discriminated all of the Vietnam time and again the recrudescence of the constant

combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms of the condition, as defined by Kardiner and

from all of the control subjects. Spiegel (9). These symptoms arise in the face of either

To summarize, three entirely independent and unre- a current stressful life event involving threat or loss-

lated studies of American combat veterans from two arousing once again emotions of terror, sadness, or

wars with the clinical symptoms of posttraumatic anger-or a threat to the individual’s own body by acute

stress disorder exhibited more abnormal behavioral illness or an accident. On exposure to such stimuli,

and physiological arousal than control subjects from a patients with posttraumatic stress disorder respond

variety of groups when exposed to meaningful stimuli with immediate and excessive physiological arousal,

reminiscent of combat (6). Thus, psychophysiological particularly in their cardiovascular and neuromuscular

assessment offers strong potential not only for diag- systems, and are at risk for cognitive dissociation.

nostic identification of a special subgroup of patients We have, then, a clinical condition induced by either

with war-induced posttraumatic stress disorder but a single massive psychological assault or by recurrent

also for assessment of the severity of the disorder. The or continued exposure to experiences associated with

total number of subjects with posttraumatic stress violent death, destruction, and/or mutilation of others,

disorder now tested from the three studies equals 88, which induce high-intensity emotional arousal. The

and the number of control subjects is now 64. emotions of fear, terror, and helpless despair are

followed by a number of constant yet repetitive behav-

ioral, cognitive, and physiological processes. In many,

SIGNIFICANCE OF FINDINGS withdrawal from exposure, nonrecurrence of expo-

sure, or avoidance of memory-arousing experiences

These findings define a subgroup of combat veterans similar to the initial stressing events is followed by

with chronic, delayed, or remitted forms of posttrau- extinction of these phenomena. In some the extinction

matic stress disorder who have a persisting condi- is only partial; somatic arousal still may be observed

tioned emotional response to stimuli reminiscent of when the gross clinical symptoms have remitted. Other

battle. We may postulate that in such men there exists patients go on to suffer delayed, recurrent, or persist-

not only an ongoing perceptual abnormality (impair- ent display of the consequences of the overwhelming

ment of the ability to discriminate specific sensory emotional assault. I emphasize “emotional” and not

inputs associated with the traumatic event) but also “psychological.” Emotion implies stimulus facilita-

excessive autonomic arousal of central adrenergic or- tion. Depending on the intensity of stimulation, it may

igin. facilitate or destroy cognitive processing. Among those

Two other research studies suggested abnormal who fail to recover from the initial assault are a group

physiological functioning in posttraumatic stress dis- who suffer recurrent or persistent clinical symptoms

order. Wenger (7) carried out extensive psychophysi- and demonstrate evidence of a conditioned emotional

ological testing to examine the assumption that differ- response.

ences in autonomic balance existed between 298

World War II combat flyers convalescing from what

was then designated in the Air Force as “operational CONDITIONED FEAR IN ANIMALS

fatigue” and 482 aviation students in training who had

not yet been to combat. He recorded without stimula- Much has been learned about conditioned fear in

tion 20 different tests of autonomic function and found animals that seems directly relevant here. Directly

that nine attained differential statistical significance pertinent to chronic posttraumatic stress disorder are

and supported his hypothesis that excessive sympa- the studies of Anderson and Parmenter (10) of the

thetic function is characteristic of operational fatigue. long-term effects of experimentally induced neurosis in

Mason et a!. (8) reported on separating out neuro- animals. These researchers followed both sheep and

chemically a group of nine men with posttraumatic dogs over 12 years after induction of experimental

stress disorder and depression from 10 others with neuroses in which electric shock was used as the

major depressive disorders. The former had unusually unconditional stimulus and the sound of a metronome

high urine levels of norepinephnine as well as a dis- was used as the conditioning stimulus. The long-term

criminating norepinephrine-cortisol ratio. behavioral and physiological hyperactivity of these

Pertinent here are some clinical observations re- animals was remarkably similar to that noted in the

ported in a paper cited earlier (6). Of seven men whom chronic posttraumatic stress disorder of combat veter-

I had instructed to use a tape of combat sounds for ans with conditioned emotional response. This hyper-

desensitization (initially to be played at subliminal activity included hyperalertness to touch, the startle

Am ] Psychiatry 1 44:8, August 1987 991

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL HYPOTHESIS

reaction to sound (crouching, trembling, running, and out gross neunoanatomical rearrangement. Kandel’s

even defecation), a “set” toward overreaction, gener- sensitization experiments have not been carried to the

alization of the reaction to other stimuli, and restless- point of excessive stimulation oven long periods of

ness. Some animals later developed a state of immo- time.

bility when placed in the experimental room, as Reiser (14) recognized the relationship between the

though they were afraid to move. Also noted in these new neurobiological understandings and psychological

animals over a period of years was continued cardiac processing and illustrated this in an analysis of a

and respiratory dysfunctions. Tachycardia occurred typical case of social stress. My clinical and research

when the animals were brought to the laboratory. data derive from the consequence of overwhelming,

In their work on traumatic avoidance learning in often repeated catastrophic stress. Such stress requires

animals, Solomon and Wynne (11) stated, “In the case that we go beyond the ordinary learning experiences or

of intense anxiety established with the support of an their absence and examine the consequences of exces-

initial pain-fear reaction, we believe that the classically sive sensitizing stimulation on the neural structure.

conditioned responses have become incapable of corn-

plete extinction.” Further, they postulated a relatively

permanent “decreased threshold phenomenon or sen- NEURONAL EFFECTS OF HIGH-INTENSITY

sitization phenomenon,” which leads to “an increase STIMULATION

in probability of occurrence.”

That environmental experiences provide the sensory That excessive external stimulation might affect

stimulation on which both functional and anatomical neuronal structure has been postulated in the past.

development of the brain depends is now cleanly Freud (15) described a “stimulus barrier” consisting of

evident from neurobiological research. These findings a series of neunoanatomical structures-including the

became possible only through the advances in electro- skin, the peripheral sense organs, and an internalized

physiological, neurochemical, and imaging techniques. neuronal layer-developed to protect organisms from

For instance, Hubel and Wiesel (12) demonstrated that excessive and destructive external stimulation. Miller

the visual cortex (area 17) of both cats and macaque (16) brought together the physiological and psycholog-

monkeys fails to develop physiologically if they are ical data pertaining to excessive stimulation under the

deprived of monocular vision at critical periods of rubric of overload of information processing. In gen-

early life. Neurons from the opposite geniculate nu- era!, the data indicate that as information input in-

cleus tend to grow into visually deprived and undevel- creases, information output initially increases but

oped columns of cortical dominance. These findings gradually falls behind at the level of channel capacity.

suggested to the researchers that a form of competitive With further increases in input, output decreases to

interaction takes place between the neuronal growth of complete nonfunction and psychological confusional

the two opposing visual pathways. Stimuli from the states occur. Before that, a variety of efforts at adap-

eye not deprived of vision induce electrophysiological tation to overload take place; these are evident in

activity in the maldeveloped area. These maldevelop- obvious errors, omissions, etc. Possible central neuno-

ments were confirmed neuroanatomically by autora- nal structural (neuroanatomical) change as the result

diographic techniques. of such overload has not been studied.

Studies of learning processes in the simple nervous Nevertheless, both clinical and laboratory data exist

system of the snail Aplysia californica by Kandel (13) that demonstrate both functional and structural

have made it clear that synaptic function changes change following high-intensity stimulation of the

depending on the nature of the learning process. Thus, peripheral nervous system. The known consequences

during habituation of the gill reflex of Aplysia, when of such stimulation for the acoustic system provide an

the animal learns “to recognize and ignore a particular excellent model to conceptualize central neunonal

stimulus because its consequences are trivial” (a prim- change. Clinical observations (17, 18) have established

itive form of perception), many synaptic connections that such stimulation-either remittent on of long

become inactive without the intervention of revenber- duration-causes deafness of varying types and duna-

ating circuits as in a closed set of neurons. Kandel’s tion. Clinically, such loss of function may occur

studies on sensitization learning are particularly rele- acutely, may be temporary, or may be permanent;

vant to questions related to posttraumatic stress disor- these outcomes relate to both the intensity and the

den. Sensitization enhances the animal’s attention to duration of the sound stimulation. Thus, volunteers

threatening stimuli. It involves postsynaptic facilita- exposed to 1 10 to 130 decibels for periods of 1 to 64

tion mediated by axo-axonic synapses. If habituation minutes consistently develop temporary high-tone

has been achieved, sensitization reverses the presynap- hearing loss. In animal experimental studies of induced

tic and behavioral depression produced by either noise deafness after excessive sound stimulation, light

short- on long-term learning. Although change is evi- microscopy has demonstrated initial changes in the

dent electrophysiologically, it is not now fully under- external hair cells in the form of deformation of

stood what occurs at the synaptic terminals during the swelling of the cell body. With more severe injuries,

learning process. Kandel suggested that neurochemi- other cells (pillar, Deitens’ and Hensen’s), including the

cal changes must occur at synaptic connections with- internal hair cells, are damaged, and eventual cochlean

992 Am J Psychiatry 144:8, August 1987

LAWRENCE C. KOLB

neuronal atrophy ensues. A variety of neunonal bio- ogy to explain posttraumatic stness disorder psychopa-

chemical changes have also been identified as follow- thology. Their two-factor theory relies both on symp-

ing the stimulus trauma. From these studies it has been tom explanation through classical conditioning

suggested that moderate intensities of acoustic stimu- (through association a fear response is learned) as well

lation lead to increased metabolic activity. If excessive, as on instrumental learning principles (individuals

the changes proceed to exhaustion of enzymes and learn to avoid cues that arouse emotion). This hypoth-

glycogen stones, diminished oxygen tension, decreased esis accounts for the startle reaction in posttnaumatic

energy output, irreversible anatomical change, and stress disorder as well as its arousal by a variety of

permanent deafness. stimuli that the individual has associated with the

The emerging evidence of the existence of psycho- traumatic event-sounds, smells, and a wide variety of

physiological, neuroendocnine, and neunochemical ab- visual perceptions, including people. Keane et a!. nec-

nonmalities in chronic posttraumatic stress disorder ognized that posttraumatic stress disorder victims dis-

outruns the potential of the current psychological play a much widen range of symptoms in that they

explanations derived from psychoanalytic on learning respond to other crises not associated with the event.

theories. Confronted with the phenomenology of acute To explain this phenomenon, they invoked higher-

cases of wan neuroses, Freud (19) stated, “The wan onden conditioning and generalization for those symp-

neuroses insofar as they ane distinguished from the toms not definable by their two-factor theory. I have

ordinary neuroses of peacetime by special chanactenis- discussed and critiqued these various explanations in a

tics are to be regarded as traumatic neuroses whose paper presented during a National Institute of Mental

occurrence has been made possible by a conflict in the Health workshop on delayed effects of posttraumatic

ego.” The conflict was perceived as occurring between stress disorders held in April 1986.

the individual’s striving to maintain his moral integrity

as a soldier against the drive for self-preservation. The

breakdown was perceived as due to the overwhelming A NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL HYPOTHESIS

of the psychological defensive structure of the exposed.

Plagued by the challenge to both dream and libido Using the analogy of the effect of excessive stimula-

theory in the face of the repetitive dreams and night- tion on the contact barrier leading to change in

mares of combat, psychoanalysts later offered the drive neunonal function and/on structure, we can easily

for mastery through repetition as an explanation for accommodate the symptoms and signs of posttraumat-

these symptoms as well as for related neurotic and ic stress disorder within traditional neunopsychological

chanacterological changes (20). theory (22). The primary result of excessive emotional

From their examination of many patients with stimulation is its effect on the function and perhaps the

chronic war neurosis from World Wan I, Kandiner and structure of the cortical neunonal barrier, particularly

Spiegel (9) came to the conclusion that the condition as it concerns control of aggnessivity. Such stimulus

was a “physioneunosis.” They suggested that the star- overload occurs when the human organism’s capacity

tie reaction seen in the patients with chronic neurosis to process information signaling threat to life oven-

was due to “conditioning” and that the existence of whelms the cortical defensive structural processes con-

this pattern was central to understanding patients with cenned with perceptual discrimination and effective

chronic disorders as the cause of the irritability and the adaptive responses for survival. Such stimulation may

psychosomatic symptoms. To them, the chronic war be thought to first lead to synaptic changes related to

neurosis was different from social neurosis in that the the process of neunophysiological sensitization, as de-

central focus of distress in the former nested in the scnibed by Kandel (13). If continued at high intensity

individual’s difficulty with his body image-his so- and repeated frequently over time, the processes may

matic functioning-and not with social conflict. The lead to depnession of those synaptic processes which

personality reactions were considered secondary and permit habituation and thus discriminative perception

reactive to the physioneurosis. This hypothesis more and learning. As Kandel has suggested, subtle

satisfactorily covers most of the criteria needed to neunochemical changes may occur in synaptic func-

explain the observed symptoms than do others. tions that currently defy detection by available meth-

Dobbs and Wilson (4) concluded that there existed ods. We cannot exclude the potential of actual

“remarkable similarity of the behavioral and physio- neuronal death. Sapolsky et a!. (23) reported hip-

logical responses of the war neuroses to those pro- pocampal neunonal death in cells with high glucocon-

duced experimentally in animals through condition- ticoid receptors-interpreted as the result of response

ing.” They suggested that sounds and sights simulating to stress oven time.

those of combat serve as conditioned stimuli to induce The neunonal synaptic structures affected are prob-

the self-preservative emotional responses of fight, ably located in the temponal-amygdaloid complex con-

flight, or paralysis, which become the conditioned cenned with agonistic behavior; these structures are

responses. They did not attempt to explain the coex- stressed by necunnent intensive stimulation. They may

isting personality reactions of their patients. recover, be temporarily impaired, or undergo perma-

Elaborating on this hypothesis, Keane et a!. (21) nent change, which is known to occur in the peripheral

offered a two-factor learning theory of psychopathol- (acoustic) sensory system.

Am J Psychiatry 144:8, August 1987 993

NEUROPSYCHOLOGICAL HYPOTHESIS

In terms of clinical expression in behavior, the cal expressions of the startle reaction or conditioned

individual reverts (regresses) to a state of hypensensi- emotional response-expressed subjectively as palpita-

tivity in which a multitude of stimuli, both internal and tions, panic attacks, and other pains, including head-

external, lead to arousal. Recurrent intensive emo- ache, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

tional arousal both sensitizes further and simulta- “Delay,” intensification of symptoms, and dissocia-

neously disrupts those processes related to learning tion may be recognized as expressions of primary

and habituation. This leads to reappearance or inten- cortical functional impairment. Each successive anous-

sification of existing symptoms. al of aggressive emotion by exposure to external

With excessive cortical sensitization and diminished stimuli or social incidents arousing the traumatic com-

capacity for habituation of the agonistic neunonal plex, if intense enough to overwhelm the central

system, lower brainstem structures, such as the medial controls, leads to activation of the lower centers,

hypothalamic nuclei and the locus ceruleus, activated which in turn reactivates the cortical areas related to

by the neurotransmitter norepinephnine (24), escape emotions and memory. Highly intense arousal, as in

from inhibitory cortical control. Through their exten- terror, widely disrupts cognitive functioning and pro-

sive cortical and subcortical connections, they, in turn, duces dissociative behaviors.

repeatedly reactivate the perceptual, cognitive, affec- It is the inescapable recurrence of the physiological

tive, and somatic clinical expressions related to the disturbance that affects personality organization and

original traumata. Thus, in the face of perceived stability. The repeated reminders of the traumatic

threats there occurs excessive sympathetic arousal- event associated with somatic symptoms disrupt the

including neuroendocrine disturbances as well as be- sufferer’s body image and self-concept. Subsequent

havioral expressions of rage and irritability and repet- cognitive processing induces the reactive symptoms,

itive cortical reactivation of memories related to the which present as various avoidance behaviors and a

traumatic events. The latter are projected in the day- chronic dysphonic-anxious state. Thus, one sees avoid-

time as intrusive thoughts and at nighttime in the ance behaviors such as social withdrawal, distancing

recurrent traumatic nightmares of posttraumatic stress from others, alcohol and drug abuse, or compulsive

disorder in all forms. The “constant symptoms” of activities (including work) and affective disturbances

posttraumatic stress disorder, then, are explainable as (depression, survival guilt, and shame with suicidal

expressive of cortical synaptic change related to those ideation). These symptoms cause diagnostic difficulty

processes which underlie sensitization, learning, and only when examiners fail to probe for the primary

habituation. symptoms mentioned heretofore in this paper.

It may well be that other central neuronal changes Additional intrapsychic attempts lead to restitutive

occur that underlie certain other features of chronic symptoms and behaviors as the individual recognizes

posttraumatic stress disorder. Hoppe and Bogen (25) his deficiencies in social relations due to loss or fear of

have likened the alexithymia of commissurotomized loss of control of aggressive behavior. In conflict, he

patients to that of survivors of the Nazi concentration musters up whatever personality resources and psy-

camps (chronic posttraumatic stress disorder) and chological defenses are available to him. The sufferers

psychosomatic patients. are often thought to have a personality disorder. Lindy

The hypothesis presented here of functional change and Titchenen (26) emphasized that character change

in neuronal and synaptic cortical processing of intense is to be expected after exposure to overwhelming

memories of aversive stimulation allows an under- personal disasters.

standing of the variegated symptom expressions of the As for predisposition to develop the chronic form of

condition. We may define the symptoms of posttrau- posttraumatic stress disorder and its variable impair-

matic stress disorder as 1) impaired perceptual, cogni- ment of psychosocial functioning, I now classify all

tive, and affective functions, 2) release of functions, 3) patients as having severe, moderate, on mild forms of

reactive affective states and avoidance behaviors, and the disorder. These classifications depend on the num-

4) restitutive symptoms and behaviors. ben of symptoms, their expression, and evidence of the

The primary symptoms, due to cortical neuronal conditioned emotional response as well as the poten-

change, are those of impairment of perceptual discnim- tial for later intensification of symptom expression on

ination, lessened capacity to control agonistic im- re-exposure to emotional stress. If change has occurred

pulses, and, perhaps, affective blunting. Discnimina- through excessive stimulation, future processing of

tion of threatening stimuli is less accurate, as such messages will vary according to the extent of

demonstrated in the increased sensitivity to a multi- sensitizing change brought about by the excessive

tude of external cues associated by conditioning to the traumatic stimulation as well as the number of acti-

threatening traumatic incident or incidents. vated neurons available.

The symptoms of release, due to excessive activation Younger persons are said to be more susceptible to

of hindbrain centers, are the “constant” symptoms of the development of posttnaumatic stress disorder. They

the condition. These are the startle reaction (condi- have had less experience and therefore, perhaps, less

tioned emotional response), irritability, hypenalertness, neunonal activation. Olden persons, who are also more

intrusive thinking, repetitive fearful nightmares and susceptible, are already undergoing neuronal inactiva-

dreams of the event, and the various psychophysiologi- tion. As for the reported greater resistance of military

994 Am J Psychiatry 144:8, August 1987

LAWRENCE C. KOLB

officers to developing posttnaumatic stress disorder, we 5. Malloy PF, Fairbank JA, Keane TM: Validation of a

multimethod assessment of post-traumatic stress disorders in

may presume that their neuronal network is numeni-

Vietnam veterans. J Consult Clin Psychol 1983; 51:488-494

cally larger than that of nonofficers and, through

6. Kolb LC: The post traumatic stress disorders of combat: a

education and diverse experiences, better evolved and subgroup with a conditioned emotional response. Milit Med

integrated and therefore more flexible. Persons who 1984; 149:237-243

have been emotionally traumatized early in life may be 7. Wenger MA: Studies in Autonomic Balance in Army-Air Force

thought to be at risk for breakdown, depending on the Personnel: Comparative Psychological Monograph. Berkeley,

intensity and duration of the early life-threatening University of California Press, 1948

experience. My clinical experience is that surviving 8. Mason J, Giller EL, Kosten TR, et al: Elevated norepinephrine/

cortisol ratio in PTSD, in New Research Program and Abstracts,

men who developed symptoms on the combat line and

138th Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

were returned to duty only to collapse later have ended Washington, DC, APA, 1985

up with the most severe pathology-the “catetenoid” 9. Kardiner A, Spiegel H: The Traumatic Neuroses of War. New

states. On the other hand, healthy soldiers who have York, Paul Hoeber, 1947

been sensitized to exposure to emotional suffering by 10. Anderson OD, Parmenter R: Long-Term Study of the Experi-

mental Neurosis in the Sheep and Dog: With Nine Case

their near catastrophic experience often develop adap-

Histories. Psychosomatic Medicine Monograph 2(3,4), 1941

tive social behaviors; their capacity for empathic un- 11. Solomon RL, Wynne LC: Traumatic avoidance learning: the

derstanding often seems enlarged. principles of anxiety conservation and partial irreversibility.

This neuropsychological hypothesis contains many Psychol Rev 1954; 61:353-385

implications for and already has influenced treatment 12. Hubel DH, Wiesel TH: Ferrier lecture: functional architecture

ofmacaque monkey visual cortex. Proc R Soc Land [Biol] 1977;

planning and procedures (27). It has led to the trial of

198: 1-59

adrenergic blocking agents to attenuate the cardinal 13. Kandel ER: Environmental determinants of brain architecture

symptoms of the disorder (28). and of behavior: early experience and learning, in Principles of

Neural Science. Edited by Kandel EP, Schwartz JH. New York,

Elsevier/North Holland, 1982

14. Reiser MF: Mind, Brain, Body: Toward a Convergence of

POTENTIAL FUTURE RESEARCH Psychoanalysis and Neurobiology. New York, Basic Books,

1984

Is possible

it through research to discover support 15. Freud 5: Beyond the pleasure principle (1920), in Complete

for the hypothesis put forward? Some immediate Psychological Works, standard ed, vol 20. London, Hogarth

Press, 1959

projects come to mind:

16. Miller JG: Living Systems. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1978

1. Examine with modern imaging techniques the 17. Schuknecht H: Pathology of the Ear. Cambridge, Harvard

physiological and neurochemical processing of mean- University Press, 1974, pp 302-303

ingful combat-simulating stimuli and nonmeaningful 18. Miller JD: Effects of noise on people. J Acoust Soc Am 1974;

56:729-740

stimuli in combat-induced posttraumatic stress disor-

19. Freud S: Preface, in Psychoanalysis and the War Neuroses. By

der victims and control groups. Ferenczi S, Abraham K, Simmel E, et al. New York, Inter-

2. Examine particularly the limbic and lower national Psychoanalytic Press, 1921

brainstem structures with modern neuropathological 20. Ferenczi S: Theory and Technique of Psychoanalysis. New

and neurochemical techniques in post-mortem mate- York, Basic Books, 1952

21. Keane TM, Zimmering RT, Caddell JM: A behavioral formu-

rial from combat veterans, concentration camp survi-

lation of post traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans.

vors, and former prisoners of war with posttraumatic Behavior Therapist 1985; 8:9-12

stress disorder. 22. Jackson JH: Selected Writings, vol II: Evolution and Dissolution

3. Examine prospectively psychophysiological, elec- of the.Nervous System. Edited by Taylor J. New York, Basic

trophysiological, and neunochemical responses in both Books, 1958

23. Sapolsky RM, Krey LC, McEwen BS: Glucocorticoid-sensinve

baseline and arousal status in abused and nonabused hippocampal neurons are involved in terminating the

children. adrenocortical stress response. Proc Nail Acad Sci USA 1984;

4. Carry out similar studies in animals with fear- 81:6174-6177

conditioned chronic states. 24. Redmond DE: Alterations in the function of the nucleus locus

coeruleus: a possible model for studies of anxiety, in Animal

Models in Psychiatry and Neurology. Edited by Hanin 1, Usdin

REFERENCES E. Oxford, Penguin Press, 1977

25. Hoppe KD, Bogen JE: Alexithymia in twelve commissurotom-

1. Kolb LC, Mutalipassi LR: The conditioned emotional response: ized patients. Psychother Psychosom 1977; 28:148-155

a sub-class of the chronic and delayed post-traumatic stress 26. Lindy JD, TitchenerJ: Acts of god and man: long term character

disorder. Psychiatr Annals 1982; 12:979-987 change in survivors of disasters and the law. Behavioral Science

2. Blanchard EB, Kolb LC, Pallmeyer TP, et al: A psychophysia- and the Law 1983; 1:85-96

logic study of post traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veter- 27. Kolb LC: A theoretical model for planning treatment of post

ans. Psychiatr Q 1983; 54:220-228 traumatic stress disorders of combat. Curr Psychiatr Ther I 986;

3. Blanchard EB, Kolb LC, Gerardi RJ, et al: Cardiac response to 23:119-127

relevant stimuli as an adjunctive tool for diagnosing post 28. Kolb LC, Burns BC, Griffiths 5: Propranolol and clonidine in

traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Behavior Ther- treatment of post traumatic stress disorders, in Post-Traumatic

apy 1986; 17:592-606 Stress Disorder: Psychological and Biological Sequelae. Edited

4. Dobbs D, Wilson WP: Observations on persistence of war by van der Kolk BA. Washington, DC, American Psychiatric

neurosis. Dis Nerv Syst 1960; 21:686-691 Press, 1984

Am] Psychiatry 144:8, August 1987 995

You might also like

- Running Head: MIAH ZAVARRO V3 Miah Zavarro V3 Name Course Institution DateDocument4 pagesRunning Head: MIAH ZAVARRO V3 Miah Zavarro V3 Name Course Institution DateSammy Chege100% (1)

- Pat Ogden Sensorimotor Therapy PDFDocument16 pagesPat Ogden Sensorimotor Therapy PDFEmili Giralt GuarroNo ratings yet

- ESC-GASTPE School COVID19 Recovery and Readiness Plan S.Y. 2020 - 2021Document5 pagesESC-GASTPE School COVID19 Recovery and Readiness Plan S.Y. 2020 - 2021Jubylyn Aficial100% (3)

- Directions In: PsychiatryDocument44 pagesDirections In: Psychiatrybrad_99100% (2)

- Neurobiology of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder - Newport & NemeroffDocument9 pagesNeurobiology of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder - Newport & NemeroffunonguyNo ratings yet

- PETRONAS Fuel Oil 80: Safety Data SheetDocument10 pagesPETRONAS Fuel Oil 80: Safety Data SheetJaharudin JuhanNo ratings yet

- Postconcussion SyndromeDocument16 pagesPostconcussion SyndromeonaNo ratings yet

- D HC OperatorsDocument5,396 pagesD HC OperatorsCoupon VampireNo ratings yet

- The Body Keeps The ScoreDocument46 pagesThe Body Keeps The ScoreCatalina Ursa50% (4)

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaDocument17 pagesPost Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaMariana VilcaNo ratings yet

- Rta Stress Horowitz 1986Document9 pagesRta Stress Horowitz 1986marielaNo ratings yet

- Andrew Oberle, Neuroscience Informed Approach To TraumaDocument5 pagesAndrew Oberle, Neuroscience Informed Approach To TraumaSilvio danteNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument43 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptL JNo ratings yet

- Peritraumatik Penyebab PTSDDocument7 pagesPeritraumatik Penyebab PTSDistianna nurhidayatiNo ratings yet

- PsychoneuroendocrinologyDocument12 pagesPsychoneuroendocrinologyFahrunnisa NurdinNo ratings yet

- Neurologic Desensitization in The Treatment of Posttraumatic StressDocument16 pagesNeurologic Desensitization in The Treatment of Posttraumatic StressVictor Lopez SueroNo ratings yet

- Structural and Functional Neuroplasticity in Relation To Traumatic StressDocument5 pagesStructural and Functional Neuroplasticity in Relation To Traumatic Stressapi-348971279No ratings yet

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder After Cerebrovascular EventsDocument2 pagesPosttraumatic Stress Disorder After Cerebrovascular EventsdenisNo ratings yet

- Context Processing and The Neurobiology of Post Traumatic PDFDocument35 pagesContext Processing and The Neurobiology of Post Traumatic PDFUSM San IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Revues - Voluntad 2Document17 pagesRevues - Voluntad 2Victor CarrenoNo ratings yet

- Central Mechanisms of Pathological PainDocument9 pagesCentral Mechanisms of Pathological PainRocio DominguezNo ratings yet

- Contrafactual ThinkingDocument8 pagesContrafactual ThinkingLucasNo ratings yet

- Progress in Neuropsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry: Etienne Vachon-PresseauDocument8 pagesProgress in Neuropsychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry: Etienne Vachon-PresseauFrancisco JavierNo ratings yet

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: In-Depth ReviewDocument5 pagesPost-Traumatic Stress Disorder: In-Depth ReviewStardya RuntuwarowNo ratings yet

- Pathological Grief Diagnosis and ExplanationDocument14 pagesPathological Grief Diagnosis and ExplanationChana FernandesNo ratings yet

- Evaluacion y Tratamiento Psicodinamico en Pacientes TraumatiDocument12 pagesEvaluacion y Tratamiento Psicodinamico en Pacientes TraumatijoNo ratings yet

- Articulo 3Document19 pagesArticulo 3Virginia ManzanoNo ratings yet

- Dissociation Affect Dysregulation Somatization BVDKDocument22 pagesDissociation Affect Dysregulation Somatization BVDKkanuNo ratings yet

- Aupperle 2012 - Executive Function and PTSDDocument9 pagesAupperle 2012 - Executive Function and PTSDElena-Andreea MutNo ratings yet

- Update On The Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Volume 38: Number 2: April 2015Document5 pagesUpdate On The Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: Volume 38: Number 2: April 2015Via Eliadora TogatoropNo ratings yet

- Factorii de Risc În Vulnerabilitatea Durerii CroniceDocument9 pagesFactorii de Risc În Vulnerabilitatea Durerii Cronicecj_catalinaNo ratings yet

- Symptomatology and Psychopathology of Mental Health Problems After DisasterDocument11 pagesSymptomatology and Psychopathology of Mental Health Problems After DisasterFelipe Ignacio Vilugron ConstanzoNo ratings yet

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: In-Depth ReviewDocument5 pagesPost-Traumatic Stress Disorder: In-Depth ReviewnovywardanaNo ratings yet

- D Jeffrey Newport and Charles B Nemeroff : Neurobiology of Posttraumatic Stress DisorderDocument8 pagesD Jeffrey Newport and Charles B Nemeroff : Neurobiology of Posttraumatic Stress DisordermapiNo ratings yet

- Body20keeps20the20score 20kolk20Document22 pagesBody20keeps20the20score 20kolk20lauraspring72No ratings yet

- PTJ 0339Document13 pagesPTJ 0339api-438956780No ratings yet

- Anxiety After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument10 pagesAnxiety After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisMeilisa KusdiantoNo ratings yet

- Acupuntura AlgoDocument6 pagesAcupuntura AlgoSergio SCNo ratings yet

- The Body Keeps The ScoreDocument22 pagesThe Body Keeps The ScoreLaura Paola Garcia100% (1)

- Psicosis Cicloide y Su Diagnóstico LongitudinalDocument6 pagesPsicosis Cicloide y Su Diagnóstico LongitudinalmarielaNo ratings yet

- Reaction To Severe Stress and Adjustment DisorderDocument22 pagesReaction To Severe Stress and Adjustment DisorderTulika SarkarNo ratings yet

- Quality of Life in Stroke SurvivorsDocument7 pagesQuality of Life in Stroke SurvivorsMiriam NovoNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: How The Neurocircuitry and Genetics of Fear Inhibition May Inform Our Understanding of PTSDDocument25 pagesNIH Public Access: How The Neurocircuitry and Genetics of Fear Inhibition May Inform Our Understanding of PTSDmapiNo ratings yet

- ASIADocument9 pagesASIADiana BNo ratings yet

- Mood Disorders Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Ricardo Jorge & Robert G. RobinsonDocument11 pagesMood Disorders Following Traumatic Brain Injury: Ricardo Jorge & Robert G. RobinsonCarolina MuñozNo ratings yet

- DialoguesClinNeurosci 13 366 PDFDocument5 pagesDialoguesClinNeurosci 13 366 PDFAfriza Bin Yuana ArifinNo ratings yet

- Tept Artículo de RevisiónDocument9 pagesTept Artículo de RevisiónVanesa Molina AcurioNo ratings yet

- Nemeroff Heim PTSDDocument12 pagesNemeroff Heim PTSDmariela100% (1)

- Coping With Gulf War Combat Stress: Mediating and Moderating EffectsDocument10 pagesCoping With Gulf War Combat Stress: Mediating and Moderating Effectstatu sorinaNo ratings yet

- Fnins 17 1281401Document16 pagesFnins 17 1281401adinjiaNo ratings yet

- Pittenger 2007Document22 pagesPittenger 2007rocambolescas perthNo ratings yet

- Psychological Therapies For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder PDFDocument5 pagesPsychological Therapies For Posttraumatic Stress Disorder PDFJessicaPudduNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Anxiety Disorders: Charles I. Shelton, DODocument4 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Anxiety Disorders: Charles I. Shelton, DODaniar N. HanifahNo ratings yet

- La Psiconeuroinmunología y El TraumaDocument27 pagesLa Psiconeuroinmunología y El TraumaAnonymous Hy99nkiNo ratings yet

- Pyszczynski 2011Document24 pagesPyszczynski 2011cutkilerNo ratings yet

- Npp201088a 2Document20 pagesNpp201088a 2Gia KuteliaNo ratings yet

- Postamatric Stress DisorderDocument1 pagePostamatric Stress DisorderDavid Felipe Gomez AcevedoNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Neurobiology of The Premonitory Urge in Tourette Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Treatment ImplicationsDocument19 pagesHHS Public Access: Neurobiology of The Premonitory Urge in Tourette Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Treatment Implicationsyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- A Cognitive Model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - Ehlers - Clark - 2000Document27 pagesA Cognitive Model of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder - Ehlers - Clark - 2000Dana Goţia100% (1)

- Caneta MágicaDocument7 pagesCaneta MágicaWeverton MedeirosNo ratings yet

- Stress Brain PlasticityDocument15 pagesStress Brain PlasticityLilian Cerri MazzaNo ratings yet

- Prolonged Psychosocial Effects of Disaster: A Study of Buffalo CreekFrom EverandProlonged Psychosocial Effects of Disaster: A Study of Buffalo CreekRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Use of Cannabis in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress DisorderFrom EverandUse of Cannabis in the Treatment of Post-Traumatic Stress DisorderNo ratings yet

- 2005 An Anthropological Hybrid The Pragmatic Arrangement of Universalism andDocument22 pages2005 An Anthropological Hybrid The Pragmatic Arrangement of Universalism andLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Fassin SD The Endurance of CritiqueDocument34 pagesFassin SD The Endurance of CritiqueLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2001 The Explanatory Models of Mental Health Amongst Low-Income Women and Health Care Practitioners in LusakaDocument8 pages2001 The Explanatory Models of Mental Health Amongst Low-Income Women and Health Care Practitioners in LusakaLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2001 - Kyol Goeu ('Wind Overload') Part I - A Cultural Syndrome of Orthostatic Panic Among Khmer RefugeesDocument30 pages2001 - Kyol Goeu ('Wind Overload') Part I - A Cultural Syndrome of Orthostatic Panic Among Khmer RefugeesLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2001 - Kyol Goeu ('Wind Overload') Part IIDocument28 pages2001 - Kyol Goeu ('Wind Overload') Part IILuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2001) - Trauma and Loss As Determinants of Medically Unexplained Epidemic Illness in A Bhutanese Refugee CampDocument9 pages2001) - Trauma and Loss As Determinants of Medically Unexplained Epidemic Illness in A Bhutanese Refugee CampLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Challenging Definitions of Psychological Trauma: Connecting Racial Microaggressions and Traumatic StressDocument15 pagesChallenging Definitions of Psychological Trauma: Connecting Racial Microaggressions and Traumatic StressLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 1986 Universal Aspects of Symbolic HealingDocument14 pages1986 Universal Aspects of Symbolic HealingLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2001 Kyol Goeu in CambodiaDocument6 pages2001 Kyol Goeu in CambodiaLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2000 - Globalizing Disaster Trauma - BreslauDocument24 pages2000 - Globalizing Disaster Trauma - BreslauLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- (Classics of Western Spirituality) Reuven Hammer - The Classic Midrash - Tannaitic Commentaries On The Bible-Paulist Press (1995)Document552 pages(Classics of Western Spirituality) Reuven Hammer - The Classic Midrash - Tannaitic Commentaries On The Bible-Paulist Press (1995)Luana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Internacional If SHW Is Not A Victime, Dows That Mean She Was Not TraumatizedDocument20 pagesArtigo Internacional If SHW Is Not A Victime, Dows That Mean She Was Not TraumatizedLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Jong2013 Collective Trauma ProcessingDocument18 pagesJong2013 Collective Trauma ProcessingLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2018 The Pain I Rise Above - How International Human Rights Can BestDocument33 pages2018 The Pain I Rise Above - How International Human Rights Can BestLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Perri Six, Susannah Radstone, Corinne Squire, Amal Treacher (Eds.) - Public Emotions-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2007)Document261 pagesPerri Six, Susannah Radstone, Corinne Squire, Amal Treacher (Eds.) - Public Emotions-Palgrave Macmillan UK (2007)Luana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Cultures of Trauma: Anthropological Views of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in International HealthDocument15 pagesCultures of Trauma: Anthropological Views of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in International HealthLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2016 Health Impact of Human Rights Testimony - Harming The Most VulnerableDocument5 pages2016 Health Impact of Human Rights Testimony - Harming The Most VulnerableLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2021 PTSD, Human Rights and Access To HealthcareDocument9 pages2021 PTSD, Human Rights and Access To HealthcareLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Internacional Why Do Rape Survivors Volunteer For Face-To-Face InterviewsDocument11 pagesArtigo Internacional Why Do Rape Survivors Volunteer For Face-To-Face InterviewsLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- 2018 Trauma, Depression and Burnout in The Human Rights Field - Identifying Barriers and Pathways To Resilient AdvocacyDocument57 pages2018 Trauma, Depression and Burnout in The Human Rights Field - Identifying Barriers and Pathways To Resilient AdvocacyLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Internacional Understanding Rape and Sexual Assault 20 Years of Progress and Future DirectionsDocument5 pagesArtigo Internacional Understanding Rape and Sexual Assault 20 Years of Progress and Future DirectionsLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- British Prisoners-of-War: From Resilience To Psychological Vulnerability: Reality or PerceptionDocument21 pagesBritish Prisoners-of-War: From Resilience To Psychological Vulnerability: Reality or PerceptionLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Irene Visser - Decolonizing Trauma Theory - Retrospect and Prospects - 2015Document16 pagesIrene Visser - Decolonizing Trauma Theory - Retrospect and Prospects - 2015Luana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Example06 Annotations e PDFDocument12 pagesExample06 Annotations e PDFratae20No ratings yet

- QuestionDocument5 pagesQuestionJavy mae masbateNo ratings yet

- Emotional Brain Revisited - (Impulsive Action and Impulse Control)Document24 pagesEmotional Brain Revisited - (Impulsive Action and Impulse Control)LauNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22: The Thyroid Gland: by Marissa Grotzke, Dev AbrahamDocument21 pagesChapter 22: The Thyroid Gland: by Marissa Grotzke, Dev AbrahamJanielle FajardoNo ratings yet

- Metil MerkaptanDocument14 pagesMetil MerkaptanEngineer TeknoNo ratings yet

- Titus Lithium Battery: Safety Data SheetDocument5 pagesTitus Lithium Battery: Safety Data SheetKittikun Ap UnitechNo ratings yet

- Activity 3: Worksheet On Developmental Tasks of Being in Grade 11Document2 pagesActivity 3: Worksheet On Developmental Tasks of Being in Grade 11Ian BoneoNo ratings yet

- Peridex (Oral Rinse)Document11 pagesPeridex (Oral Rinse)Emeka NnajiNo ratings yet

- Analysis of The Health Financing Structure of BotswanaDocument5 pagesAnalysis of The Health Financing Structure of BotswanaOlusola Olabisi OgunseyeNo ratings yet

- Sample of mkt202 ProjectDocument16 pagesSample of mkt202 ProjectMohammad Sohan Khan 2121426630No ratings yet

- A Pragmatic View of Thematic AnalysisDocument5 pagesA Pragmatic View of Thematic AnalysisLouis SpencerNo ratings yet

- Health10 q3 Mod1 Healthtrendsissues v5Document27 pagesHealth10 q3 Mod1 Healthtrendsissues v5Wensyl Mae De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Rinchuse 2006Document10 pagesRinchuse 2006Natalie JaraNo ratings yet

- Print Boarding PassDocument2 pagesPrint Boarding PassAshu SinghNo ratings yet

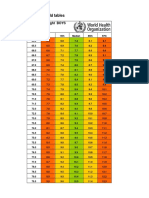

- Boys Simplified Field Tables Weight For Length 2 To 5 Years (Percentiles)Document4 pagesBoys Simplified Field Tables Weight For Length 2 To 5 Years (Percentiles)Gabrielly LopesNo ratings yet

- Citizens Civil Complaint Against Pittsfield, Cell TowerDocument65 pagesCitizens Civil Complaint Against Pittsfield, Cell ToweriBerkshires.comNo ratings yet

- Principles of CGMP in Pharmaceutical IndustriesDocument6 pagesPrinciples of CGMP in Pharmaceutical IndustriesSamer SowidanNo ratings yet

- SKM 4 - COCU - CU5 - Child - Care - Centre - ParentalDocument11 pagesSKM 4 - COCU - CU5 - Child - Care - Centre - ParentalShireen TahirNo ratings yet

- LF105 MSDS报告 2018.2.9Document15 pagesLF105 MSDS报告 2018.2.9penguking_113236970No ratings yet

- EFFECTS OF ALUGBATI (Basella Alba) On The Growth Performance of Mallard DuckDocument7 pagesEFFECTS OF ALUGBATI (Basella Alba) On The Growth Performance of Mallard DuckCyLo PatricioNo ratings yet

- Ravi Kannaiyan: QC Inspection EngineerDocument5 pagesRavi Kannaiyan: QC Inspection EngineerVinoth BalaNo ratings yet

- Sabarimala: Virtual-Q Booking CouponDocument2 pagesSabarimala: Virtual-Q Booking CouponST COMMNICATIONNo ratings yet

- Operating RoomDocument13 pagesOperating RoomrichardNo ratings yet

- EAPPQ4W4CADocument9 pagesEAPPQ4W4CAPhebi ReyNo ratings yet

- Research Paper FinalDocument12 pagesResearch Paper Finalapi-609577576No ratings yet

- Planned Parenthood Maryland 2020Document12 pagesPlanned Parenthood Maryland 2020Kate AndersonNo ratings yet