Professional Documents

Culture Documents

BRC 0015 0281

Uploaded by

ElisaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

BRC 0015 0281

Uploaded by

ElisaCopyright:

Available Formats

Research Article

Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 Received: June 4, 2019

Accepted: August 9, 2019

DOI: 10.1159/000502636 Published online: September 18, 2019

Metastatic Breast Cancer as a Chronic

Disease: Evidence-Based Data on a

Theoretical Concept

Constanze Elfgen a, b Giacomo Montagna c, d Seraina Margaretha Schmid d, e

Walter Bierbauer f Uwe Güth a, d

a Department

of Breast Surgery, Brust-Zentrum Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland; b Department of Senology,

Institute of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University of Witten-Herdecke, Witten, Germany; c Breast Center,

University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland; d Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics,

University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland; e Breast Center St. Gallen, Spital Grabs, Grabs, Switzerland;

f Department of Psychology, Applied Social and Health Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

Keywords gard to temporal progression and above all the case fatality

Metastatic breast cancer · Chronic disease · rate. More than 90% of patients in the “chronic disease sub-

Noncompliance · Long-term survival · Patient-physician group” died of the disease with a MDS of 2–3 years (even

communication those who underwent systemic palliative therapies). Doctors

and patients might understand the term “chronic disease”

differently. The term must be used sparingly and explained

Abstract carefully in order to create a common level of communica-

Background: We challenge the concept of metastatic breast tion based on a shared understanding which avoids awaken-

cancer (MBC) as a chronic disease. Methods: We analyzed an ing false hopes and fostering misleading expectations.

unselected cohort of 367 patients who were diagnosed with © 2019 S. Karger AG, Basel

MBC over a 22-year period (1990–2011). Results: In order to

create a “chronic disease subgroup”, we separated those pa-

tients from the entire cohort in whom systemic therapy was Introduction

not applied after the diagnosis of MBC (n = 53; 14.4%). Three

hundred fourteen patients (85.6%) comprised the “chronic Distant metastatic breast cancer (MBC) is generally

disease subgroup”. The vast majority of those patients considered to be a treatable, but not curable, condition

(89.8%) died of progressive disease after a median metastat- [1]. However, through the introduction of a new genera-

ic disease survival (MDS) of 25 months. Twenty patients tion of effective agents with safer profiles, together with

(6.4%) died of non-MBC-related causes (MDS 38.5 months). considerable advances in supportive care, longer survival

Approximately 1 in 4 patients (26.8%) died within the first times have been achieved during the last 2 decades, result-

year after the MBC diagnosis. The 3- and 5-year MDS rates ing in an increasing number of women living with MBC

were 35.4 and 16.2%, respectively. Only 12 patients (3.8%) [2]. As a result of this positive development, one of the

were exceptional survivors (MDS > 10 years). Conclusion: memes now embraced by both physicians and patients is

The term “chronic disease” might be appropriate in selected that of “metastatic cancer as a chronic disease” [3–6].

MBC cases, bringing MBC into alignment with “classical” The term “chronic disease” is applied to a wide range

chronic diseases such as diabetes and hypertension. How- of conditions [7]. In developed countries, in addition to

ever, most cases display fundamental differences with re- cardiovascular diseases (e.g., high blood pressure), dia-

karger@karger.com © 2019 S. Karger AG, Basel Uwe Güth

www.karger.com/brc Department of Breast Surgery, Brust-Zentrum Zürich

Seefeldstrasse 214

CH–8008 Zurich (Switzerland)

E-Mail uwe.gueth @ unibas.ch

betes, obesity, arthritis, neurologic diseases, and respi- Patients and Methods

ratory ailments such as bronchial asthma and chronic

Data from the prospective relational Basel Breast Cancer Data-

obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cancer is also

base (BBCD), which includes all newly diagnosed primary invasive

considered as one of the leading chronic disorders [8– breast cancer cases treated at the University Women’s Hospital

13]. The list of chronic diseases is very heterogeneous, Basel (Switzerland) since 1990, provided the basis for this study.

and each disease has considerable variability in its de- For this study, data from all female patients who were diagnosed

gree of severity and its course. This makes it difficult to with breast cancer up to and including 2009 was analyzed (n =

1,459).

generalize the therapeutic approach. One main thera-

During this 20-year period, 92 patients (6.3%) had primary

peutic task in the management of chronic diseases is MBC at diagnosis (stage IV). In 2011, with the exception of 37 pa-

fulfilled when a disease that cannot be completely cured tients (2.5% of the entire cohort), who were lost to follow-up after

can be treated with continuous or periodic therapy that a median follow-up time of 36 months (range 1–166), outcome

controls its progression and alleviates its symptoms information was available for all patients recorded in the BBCD.

As of March 2011, two hundred seventy-eight patients (20.3% of

with limited toxicity. One could argue that metastatic all patients who had stage I–III disease at initial diagnosis) had de-

cancer and chronic diseases share this general thera- veloped secondary distant metastases over time. Ultimately, the

peutic principle. entire cohort of women with confirmed MBC consisted of 370 pa-

The concept of MBC as a chronic disease is widely de- tients. Three patients were not considered for analysis because we

bated not only by physicians but also in many patient did not have reliable information about their distant recurrent-free

survival times and their palliative systemic therapies (overall sur-

blogs. However, more and more critical objections are vival of these patients: 25, 85, and 116 months, respectively).

being made that the label “chronic disease” is inappropri- We recorded the general type of therapy during the course of

ate for MBC [3–6]. In fact, the term “chronic disease” the disease. Furthermore, the reasons that systemic therapy was

used in discussions between physicians and patients di- not carried out were found to be as follows:

agnosed with MBC poses risks in that a common level of − Noncompliance: the patient did not start any palliative system-

ic therapy that was on offer or had been recommended. In this

communication based on a shared language (and a study, we generally defined “noncompliance” as the unwilling-

shared understanding of key terms) is no longer appli- ness of the patient to accept starting any palliative systemic

cable [7]. It may give patients the idea that they do not therapy that was on offer or had been recommended. We not

have a life-threatening and in most cases also a lethal only defined those patients who decided not to start any ther-

condition. apy as “noncompliant” but also extended this definition on pa-

tients who stopped therapy after a short time, that is, after re-

In this study we challenge the concept of MBC as a ceiving only one cycle of chemotherapy or after the intake of <

chronic disease. Evidence-based data which might eluci- 2 weeks of endocrine therapy.

date this concept is scarce. This deficit arises from the − Not recommended: patients who did not receive a recommen-

relative absence in the MBC literature of robust data with dation to undertake systemic palliative therapy for various

respect to the following 2 factors which are essential pre- medical reasons.

− Acute medical events: systemic therapy could not be started as

requisites for such an analysis: a result of unexpected internal medical or MBC-related events.

1. Reliable data collection on the long-term survival of Out of the 367 patients who were ultimately included in the

MBC patients. study cohort, 355 patients (96.7%) were followed until death; in

2. Noncompliance on systemic palliative therapy. One these cases, the year of and age at death and the cause of death were

main inclusion criterion for a chronic disease process recorded. Two patients (0.5%) were lost to follow-up (metastatic

disease survival [MDS] at time of last consultation: 16 and 61

is that its progress can be controlled or stabilized by months, respectively). Ten patients (2.7%) who remained alive

continuous or periodic systemic therapy. In this study, were followed until November/December 2018 (median MDS at

we established a “chronic disease subgroup” by dis- the time of the last follow-up: 174 months, range 108–300).

counting from the full study cohort those patients who In all but 4 cases, information regarding the year of and age at

did not undergo systemic therapy after the diagnosis MBC diagnosis, the location of the first metastatic lesion, and the

number of metastatic sites was recorded. In all but 5 cases we had

of MBC. complete information regarding adjuvant and palliative therapy

Based on a prospectively maintained breast cancer da- courses.

tabase which includes all newly diagnosed cases at a large

Swiss breast center over a 20-year period (1990–2009), we Statistical Analysis

Using the Kaplan-Meier method, MDS was calculated from the

analyzed an unselected, consecutive cohort of MBC pa- date of diagnosis of MBC to the date of death or, for patients who

tients. Since our data covers an observation period of al- survived, the date of last follow-up. Statistical differences between

most 30 years, we are able to report the frequency of the groups in terms of survival curves were analyzed using the log-

occurrence of long-term MBC survivors. Additionally, rank test. To compare ordinal variables between 2 groups, the non-

we can provide information about a subgroup of patients parametric Wilcoxon test was performed. To compare ordinal

variables between more than 2 groups, the nonparametric Krus-

which is commonly underreported in the oncologic lit- kal-Wallis test was performed. Comparisons between nominal pa-

erature, i.e., those patients who, for various reasons, do rameters were made with Fisher’s exact test. p < 0.05 was consid-

not receive palliative systemic therapy. ered statistically significant.

282 Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 Elfgen/Montagna/Schmid/Bierbauer/

DOI: 10.1159/000502636 Güth

Table 1. Clinicopathologic characteristics of 367 patients with MBC (entire cohort)

Variable Entire cohort No systemic Chronic disease p value

(n = 367) therapy (A) subgroup (B) A vs. B

(n = 53) (n = 314)

Age at diagnosis, years 64 (28–94) 78 (30–94) 62 (28–92) <0.001

Year of MBC diagnosis

1990–1999 145 (39.5) 18 (34.0) 127 (40.4) 0.45

2000–2011 222 (60.5) 35 (66.0) 187 (59.6)

TNM stage at the initial diagnosis

Stage IV 91 (24.8) 4 (7.5) 87 (27.7) 0.001

Hormonal receptor status1

Positive 268 (74.4) 27 (51.9) 241 (78.2)

Negative 92 (25.6) 25 (48.2) 67 (21.8) <0.001

Not available 7 1 6

Her2 status1,2, n 113 17 96

Positive 30 (26.5) 4 (23.5) 26 (27.1)

Triple negative 21 (18.6) 8 (47.5) 13 (13.5) NA

Not available – – –

Pattern of metastases at the time

of MBC diagnosis

Visceral metastases 260 (71.4) 37 (71.2) 223 (71.5) 1.00

Bone only 103 (28.3) 14 (26.9) 89 (28.5)

Unknown 3 1 2

Solitary metastatic organ site 207 (57.0) 25 (48.1) 182 (58.3) 0.18

Metastatic sites

Bone 226 (62.1) 34 (65.4) 192 (61.5) 0.65

Lung 137 (37.6) 25 (48.1) 112 (35.9) 0.12

Liver 92 (25.3) 18 (34.6) 74 (23.7) 0.12

Lymph nodes3 88 (24.2) 8 (15.4) 80 (25.6) 0.11

Brain 24 (6.6) 11 (21.2) 13 (4.2) <0.001

Others 36 (9.9) 4 (7.7) 32 (10.3) 0.80

Comparison between patients without systemic palliative therapy (subgroup A) and patients who received

systemic palliative therapy (chronic disease subgroup). Values are presented as means ± SD or medians (range).

Bold indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05). NA, not available.

1 Hormonal receptor status and HER2 status were measured in the primary breast tumor.

2 Because HER-2 status has been routinely assessed for all patients since 2002, we included data from 2002 to

2009 (only in the analysis of this particular characteristic).

3 Other than ipsilateral BC-related locoregional lymph nodes.

Results tire study cohort, see subgroup A) were not included in

the “chronic disease subgroup”. The reasons why system-

The clinicopathology, treatment, and outcome charac- ic palliative therapy was not carried out are as follows

teristics of the 367 patients with MBC included in this (Fig. 1):

study are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. − Noncompliance (n = 42). The median age of this sub-

group was 69 years (range 44–94), and the median

Criteria for a “Chronic Disease Subgroup” MDS was 2.5 months (range 0.5–69).

The “chronic disease subgroup” on which our analysis − Not recommended (n = 7). The median age of this sub-

was based was a cohort consisting of those patients who group was 88 years (range 78–91), and the median

received systemic therapy after the diagnosis of MBC. It MDS was 2.5 months (range 1–16).

was created from the full cohort by discounting those pa- − Acute medical events (n = 4).

tients who did not receive such treatment. Figure 1 illus- The frequency of patients who, for various reasons, did

trates the paths of this selection process. After careful not receive systemic therapies after MBC diagnosis was

analysis of the disease and therapy courses, 314 patients equally distributed over time (1990–1999: 12.4% vs.

(85.6%) comprised the “chronic disease subgroup” (Ta- 2000–2011: 15.8%, p = 0.45).

bles 1, 2, subgroup B). In total, 53 cases (14.4% of the en-

MBC as a Chronic Disease Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 283

DOI: 10.1159/000502636

Table 2. Therapy and outcome characteristics

Variable Entire cohort No systemic Chronic disease p value

(n = 367) therapy (A) subgroup (B) A vs. B

(n = 53) (n = 314)

Previous systemic therapy

None (therapy naive) 147 (40.1) 17 (32.1) 130 (41.5) 0.23

Unknown 1 – 1

Palliative systemic therapy, n (%)

None 55 (15.0) – 2 (0.6) NA

ET alone 85 (23.2) 4 85 (27.2)

CT1 alone 85 (23.2) 3 85 (27.2)

Combined therapy: ET + CT1 141 (38.5) – 141 (45.0)

Unknown regimen 1 – 1

Therapy lines, n 3 (1–13) – 3 (1–13)

Outcome status

Died on MBC 333 (90.7) 51 (96.2) 282 (89.8) 0.20

Died of other causes 22 (6.0) 2 (3.8) 20 (6.4)

Alive (metastatic disease)2 5 (1.4) – 5 (1.6)

Alive (no evidence of disease)2 7 (1.9) – 7 (2.2)

Survival time2

DRFS, months 38.5 (2–215) 39 (6–184) 38.5 (2–215) 0.72

MDS, months 21 (0.5–300) 2 (0.5–69) 26.5 (1–300) <0.001

MDS ≤3 months 47 (12.8) 31 (58.5) 16 (5.1) NA

MDS ≤12 months 130 (35.4) 46 (86.8) 84 (26.8)

MDS ≥3 years 112 (30.5) 1 (1.9) 111 (35.4)

MDS ≥5 years 52 (14.2) 1 (1.9) 51 (16.2)

MDS ≥10 years 12 (3.3) – 12 (3.8)

Overall survival, months 54 (1–341) 37 (2–186) 56.5 (1–341) 0.006

The entire cohort consisted of 367 patients. Values are presented as means ± SD, medians (range), or numbers

(%). Bold indicates a statistically significant difference (p < 0.05).

Subgroup A: patients who did not receive systemic palliative therapy. Subgroup B: “chronic disease subgroup”.

1 Includes also immunotherapy with trastuzumab.

2 Two patients were lost to follow-up (MDS at the time of the last consultation: 16 and 61 months, respectively).

The patient with the longer MDS had ovarian metastases at the initial MBC diagnosis; endocrine therapy was given

for hormone receptor-positive disease; there was no evidence of disease at the last follow-up. MBC, distant metastatic

breast cancer; DRFS, distant recurrence-free survival; ET, endocrine therapy; CT, chemotherapy; NA, not available.

Comparison of Both Subgroups diagnosis of the primary disease to the time of MBC

Compared with the “chronic disease subgroup”, those (DRFS: 39 vs. 38.5 months, p = 0.72), survival times after

who remained untreated were significantly older (78 vs. MBC diagnosis were significantly shorter in the “no-ther-

62 years, p < 0.001), more often had an aggressive tumor apy group” (MDS: 2 vs. 26.5 months, p < 0.001).

subtype (hormone receptor-negative carcinomas: 48.2 vs.

21.8%, p < 0.001) and secondary MBC (92.5 vs. 72.3%, Outcome of the “Chronic Disease Subgroup”

p = 0.001). Figure 2 shows the survival curve of the entire cohort

Between patients in the “chronic disease subgroup” (n = 367) as well as the survival curve of the “chronic dis-

and those who did not receive systemic therapy there ease subgroup” (n = 314). It displays a shift in the MDS

were no significant differences with regard to the pres- rates from 21 months (entire cohort) to 26.5 months

ence of visceral metastases (71.5 vs. 71.2%, p = 1.00). We (“chronic disease subgroup”, p = 0.046). Table 2 shows

observed a lower percentage of multiple metastatic sites that approximately 1 out of 4 patients died within the first

in the “chronic disease group”, though this did not reach year after MBC diagnosis. The 3- and 5-year MDS were

statistical significance (>1 metastatic organ site: 41.7 vs. 35.4 and 16.2%, respectively. Twelve patients (3.8%) were

51.9%, p = 0.18). With regard to the distribution of vis- exceptional survivors, with an MDS of more than 10

ceral metastatic sites, the patients in whom no systemic years.

therapy had been performed had significantly more fre- Figure 3 shows survival times with regard to different

quent brain metastases (21.2 vs. 4.2%, p < 0.001). While clinicopathologic characteristics. Even in a subcohort of

both subgroups were similar in terms of the interval from patients who displayed a combination of several favorable

284 Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 Elfgen/Montagna/Schmid/Bierbauer/

DOI: 10.1159/000502636 Güth

Color version available online

Fig. 1. Selection process of the “chronic disease subgroup”. CT, tion; MDS: 4 weeks. 3 Age at MBC diagnosis: 66 years; MS: bone

chemotherapy; ET, endocrine therapy; HR, hormone receptor; (multiple), mediastinal lymph node; palliative therapy: anterior

MS, metastatic organ site. 1 Age at MBC diagnosis: 79 years; MS: cervical corpectomy; MDS: 8 weeks. 4 Age at MBC diagnosis: 93

lymph nodes; MDS: 1 week. 2 Age at MBC diagnosis: 30 years; MS: years; MS: bone (multiple); palliative therapy: orthopedic surgery

brain; palliative therapy: transsphenoidal pituitary tumor resec- (pathological fracture of the hip); MDS: 1 week.

clinicopathologic characteristics (a younger age, hor-

mone receptor-positive disease, and only 1 metastatic or-

gan site; n = 87; 27.7% of the “chronic disease subgroup”)

the median MDS was only 37 months.

At the time of data analysis in November/December

2018, the vast majority of the patients (89.8%) had died of

progressive disease after a median MDS of 25 months

(range 1–127) at a median age of 65 years (range 29–93).

It is to be expected that this percentage will increase

slightly up to approximately 91–92%. Four long-term

survivors (1.3%) were still alive at the time of the last fol-

low-up but suffered from progressive disease. These pa-

tients had a median MDS of 136.5 months (range 112–

188) and were of an advanced age (72, 79, 84, and 85 years,

respectively).

Twenty patients (6.4%) died of other, non-MBC re-

Fig. 2. Comparison of MDS of unselected patients with MBC (en-

lated causes. Those women had a median MDS of 38.5 tire cohort, n = 367, grey line) vs. the “chronic disease subgroup”

months (range 3–126). The median age at diagnosis of (n = 314, black line); one-tailed test: p = 0.046.

MBC was 72.5 years (range 46–89) and the median age at

death was 74.5 years (range 52–94). It is to be expected

that this percentage will increase to approximately 8% Discussion

due to 6 long-term survivors (1.9%) who were not only

alive at last follow-up but who had also exhibited no evi- Our study has some limitations. First, it only includes

dence of disease. These women had a median MDS of 139 patients from a single region of a small country with a

months (range 108–300). The median age at diagnosis of high socioeconomic status where all inhabitants have

MBC was 47 years (range 39–60). universal access to health care. Second, it is a retrospective

MBC as a Chronic Disease Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 285

DOI: 10.1159/000502636

Fig. 3. MDS times with regard to different clinicopathologic characteristics. HR, hormone receptor.

analysis. However, this study has the important strength those patients who received no systemic antineoplastic

of an almost complete data documentation of: therapy during their palliative disease course. Conse-

− The entire cohort. Our prospectively maintained data- quently, approximately 14% of the patients of the entire

base included all patients newly diagnosed with breast cohort were excluded from the chronic disease subgroup;

cancer over a 20-year period (1990–2009). The rate of the majority of these patients (83%) had actively decided

patients who were lost-to-follow-up was very low (< against the recommended therapy and could therefore

3%), and only very few patients, who could have po- also be designated as a “noncompliance subgroup”. Inter-

tentially developed MBC, were missed. estingly, there was no change in the frequency of occur-

− The group of patients who were diagnosed with MBC. rence of patients who did not receive palliative systemic

The vast majority (>98%) of the palliative courses were therapy over time. It might have been assumed that with

completely documented with regard to metastatic pat- the new generation of effective agents with safer profiles

terns and palliative therapy. and with considerable advances in supportive care (a de-

velopment that started around the late 1990s) the reserva-

Criteria for a “Chronic Disease Subgroup” tions of patients about oncologic therapies would have

In order to challenge the concept of MBC as a chronic decreased. That was not the case in our cohort.

disease, we created a “chronic disease subgroup”. One Our model of data analysis could also be usefully ap-

main inclusion criterion for a chronic disease is that its plied in other retrospective analyses of large cancer co-

progress can be controlled or stabilized by continuous or horts. For a clear and comprehensive real-world picture

periodic systemic therapy. Due to the complete docu- of the effectiveness of palliative systemic therapy on MDS

mentation of the entire cohort, we were able to separate in an otherwise unselected cohort it is essential to take

286 Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 Elfgen/Montagna/Schmid/Bierbauer/

DOI: 10.1159/000502636 Güth

into account those patients who had undergone systemic chronic disease. The nature of MBC is clearly different

therapy and to separate them from those patients who for from that of obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, arthri-

whatever reason did not undergo systemic therapy. After tis, or COPD. These diseases can lead to death, but not

creating this “chronic disease subgroup”, we observed a inevitably so. In contrast, more than 90% of the MBC pa-

marked shift in the MDS rates from 21 to 26.5 months. tients die of the disease, with a survival time of 2–3 years

after diagnosis of distant metastases – even those who un-

Is MBC a Chronic Disease? dergo systemic palliative therapies.

There can be no doubt that there are overlaps in defi-

nition between “classical” chronic diseases and metastat- “MBC Is Like Diabetes:” the Term “Chronic Disease”

ic cancer: they are both long-lasting or recurrent; they as a Potential Source of Misinterpretation in Patient-

both require long-term treatment, supervision, observa- Physician Communication

tion or care; they are caused by nonreversible pathologi- It is one of the most unpleasant and difficult tasks for a

cal alterations; and they can be altered but not cured by doctor to have to explain to a patient that they are suffering

medication [14, 15]. Furthermore, the general therapy from an incurable metastatic disease which, despite thera-

principles of chronic disease (long-term stabilization py, will in the normal course of events result in their death

with a good tolerance to drugs that have a limited cumu- within 2–5 years. The physician has the important task of

lative toxicity) also correspond with those of palliative providing a clear and sensitive prognosis while building the

cancer therapy. On the other hand, the majority of chron- courage and the confidence to face the coming course of the

ic diseases and MBC display fundamental differences disease. It may be superficially attractive to designate the

with regard to temporal progression and above all the further course of the disease as “chronic”, but it should not

case fatality rate. surprise the doctor that a patient understands the term

The term “chronic” has its origin in Greek (khronikos, “chronic disease” differently [7]. The median age of the pa-

i.e., of time). In the particular case of illness, it now means tients of our “chronic disease subgroup” was 62 years; ap-

in English “persisting for a long time or constantly recur- proximately one third of the patients were older than 70

ring” [16]. The criteria and definitions of just how much years. The majority of the women at this age had already

time must pass before the term can legitimately be applied been confronted with one or more chronic diseases with

vary widely in medical practice. Often only general, non- which they have learned to cope over many years [8, 10, 11].

specific formulations are given, e.g., “persists for a long The statement by the doctor that the MBC constitutes just

time” [10], “persistent or otherwise long-lasting” [11], or one more chronic disorder will not be particularly unset-

“of long duration and generally slow progression” [9]. tling for many patients. The term “chronic disease” might

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention be misleading because patients might interpret that MBC

(CDC) define chronic diseases as “conditions that last 1 could be controlled by long-term disciplined care similarly

year or more and require ongoing medical attention” [8]. to diabetes or hypertension [7]. Patients may even draw a

The most commonly used marker for a chronic condition comparison to AIDS in that new cancer drugs might be as

is a 3-month time span [11–13]. It is remarkable that this successful as the antiretroviral therapy which transformed

period is also used by the National Cancer Institute [12], this disease from an almost invariably fatal infection into a

even though in oncology and especially in relation to met- manageable chronic condition that for many will span sev-

astatic diseases this period makes very little sense. To ex- eral decades of life [17]. Because of this, the danger exists of

emplify this, in the case of progressive metastatic disease departing from a common level of communication based

which leads to death within 6–12 months the definition on a shared language and understanding: using the term

period has been clearly exceeded, but the course of the “chronic disease” might awaken false hopes and misleading

disease “hardly seems to fall under what a reasonable per- expectations that patients do not have a lethal disease [3, 4]

son would think of as a chronic disease” [6]. – which is clearly not the case.

A well-established parameter for estimating the prog- A misleading message might result in a high prognosis

nosis of a particular disease is the 5-year survival rate. discordance between the patient and the oncologist.

When this period is taken as the potential criterion for Gramling et al. [18] reported this discordance in approxi-

characterizing a disease as chronic, only 16% of the chron- mately 70% of cases. In that study patients with advanced

ic disease subgroup patients of our study cohort achieved cancer estimated their 2-year survival probability without

this survival time. Only approximately 4% of the patients exception more favorably than their physicians did. Nine-

had an MDS of more than 10 years. When after the diag- ty percent of the patients were not aware that their on-

nosis of MBC the doctor informs the patient of the prog- cologists held a much more skeptical prognosis than they

nosis, this long-term survival rate might arguably be pre- did but believed that their doctors shared their own posi-

sented as a prospective goal. However, it seems unjustifi- tive viewpoint. If a patient with advanced cancer expects

able to represent the MBC condition as a whole as a with 90–100% certainty to survive more than 2 years when

MBC as a Chronic Disease Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 287

DOI: 10.1159/000502636

at the same time the doctor estimates the 2-year survival The term “chronic disease” appears inappropriate in

as 10–20%, this can be problematic for the further course this situation. We must confront this terminological

of the disease because the patient’s unrealistic perceptions problem. Particularly at the end of life an appropriate pa-

of the survival prognosis might lead to inappropriate ther- tient-physician communication in a mutually under-

apies with a questionable impact on survival. stood terminology is essential to achieve an oncologic

Nevertheless, there are situations in which doctors surveillance that honors a patient’s values, preferences,

may feel the need to use a term such as “chronic disease”, and wishes [18, 19].

but in this situation it must be used sparingly and ex-

plained carefully in order to avoid miscommunication

[7]. Numerous studies have shown that advanced cancer Statement of Ethics

patients and their families, but also their doctors, avoid

The study design and data collection methods were approved

delicate issues concerning the limitation on life and the

by the institutional review board.

prognosis of survival time [19]. The term “chronic” could

lead to a trivialization of the disease and might then be-

come part of a mutual avoidance strategy. Disclosure Statement

It is probably better to avoid describing a complex,

multifaceted disease such as MBC with a single term. In The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

each individual case we have to ask ourselves what termi-

nology can be appropriately used to describe the disease

progress and prognosis of a patient who has just been di- Author Contributions

agnosed with MBC and who:

− is living with progressive disease, that Prof. Uwe Güth had full access to all of the data in the study and

takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of

− will lead in the vast majority of cases to death, but who the data analysis. All of the authors directly participated in the

− is clearly not in the terminal phases of illness and who planning of the study concept, analysis and interpretation of the

− may receive targeted cancer treatment which is often data, and drafting and critical revision of this paper. They read and

able to stabilize the disease over several years with tol- approved the final version submitted for publication.

erable toxicity.

References

1 Cardoso F, Senkus E, Costa A, Papadopoulos 7 Bernell S, Howard SW. Use Your Words 13 About chronic conditions [Internet]. Wash-

E, Aapro M, André F, et al. 4th ESO-ESMO Carefully: What Is a Chronic Disease? Front ington, DC: National Health Council; 2016

International Consensus Guidelines for Ad- Public Health. 2016 Aug;4:159. Mar 21 [cited 2019 Apr 10]. Available at;

vanced Breast Cancer (ABC 4). Ann Oncol. 8 About chronic diseases [Internet]. Druid http://www.nationalhealthcouncil.org/news-

2018 Aug;29(8):1634–57. Hills (GA): Centers for Disease Control and room/about-chronic-conditions.

2 Mariotto AB, Etzioni R, Hurlbert M, Penber- Prevention (CDC); 2018 Mar 8 [cited 2019 14 Lubkin I, Larsen P. Chronic Illness. Sudbury

thy L, Mayer M. Estimation of the Number of Apr 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc. (MA): Jones & Bartlett; 2002.

Women Living with Metastatic Breast Cancer gov/chronicdisease/about/index.htm. 15 Norris S, Glasgow R, Engelgau M, et al.

in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Bio- 9 Noncommunicable Diseases [Internet]. Ge Chronic disease management: a definition

markers Prev. 2017 Jun;26(6):809–15. neve, Switzerland: World Health Organiza- and systematic approach to component inter-

3 Brenner BA. Treating breast cancer as a re tion (WHO); 2019 Jan 10 [cited 2019 Apr 10]. ventions. Dis Manag Health Outcomes. 2003

current-not chronic-disease. San Francisco Avaialble from: https://www.who.int/ncds/ Oct;11(8):477–88.

(CA): Breast Cancer Action [Internet]. Post- en/. 16 Definition of "chronic" in English [Internet].

ed on March 21, 2009 [cited 2019 Apr 10]. 10 Shiel WC Jr. Medical definition of chronic Oxford (UK): In Dictionary. Oxford English

Available from: https://bcaction.org/2009/ disease [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Medicine Dictionary; 2019 Apr 10 (cited 2019 Apr 10).

03/21/treating-breast-cancer-as-a-recurrent Net; 2018 Dec 21 [cited 2019 Apr 10]. Avail- Available at: https://en.oxforddictionaries.

%E2%80%94not-chronic.%E2%80% able at: https://www.medicinenet.com/script/ com/definition/chronic.

94disease main/art.asp?articlekey=33490. 17 Deeks SG, Lewin SR, Havlir DV. The end of

4 O’Brien K. Please Stop Calling Metastatic 11 Chronic condition [Internet]. San Francisco AIDS: HIV infection as a chronic disease.

Breast Cancer a Chronic Disease [Internet]. (Ca): Wikipedia; 2019 Apr 10 [cited Apr 2019 Lancet. 2013 Nov;382(9903):1525–33.

Posted on July 30, 2018 [cited April 5 2019). 10]. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/ 18 Gramling R, Fiscella K, Xing G, Hoerger M,

Available from: https://www.linkedin.com/ wiki/Chronic_condition. Duberstein P, Plumb S, et al. Determinants of

pulse/please-stop-calling-metastatic-breast- 12 NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms: chronic Patient-Oncologist Prognostic Discordance

cancer-chronic-disease-o-brien/. disease [Internet]. Maryland (MD): National in Advanced Cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016 Nov;

5 Sledge GW Jr. Musings of a Cancer Doctor: Cancer Institute (NCI); 2019 Apr 10 [cited 2(11):1421–6.

chronic. Oncology Times. 2014;36(20):7–11. 2019 Apr 10]. Available at: https://www.can- 19 Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of

6 Sledge GW Jr. Curing Metastatic Breast Can- cer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer- Physicians High Value Care Task Force.

cer. J Oncol Pract. 2016 Jan;12(1):6–10. terms/def/chronic-disease. Communication about serious illness care

goals: a review and synthesis of best practices.

JAMA Intern Med. 2014 Dec; 174(12): 1994–

2003.

288 Breast Care 2020;15:281–288 Elfgen/Montagna/Schmid/Bierbauer/

DOI: 10.1159/000502636 Güth

You might also like

- PHYSICS Engineering (BTech/BE) 1st First Year Notes, Books, Ebook - Free PDF DownloadDocument205 pagesPHYSICS Engineering (BTech/BE) 1st First Year Notes, Books, Ebook - Free PDF DownloadVinnie Singh100% (2)

- Design of Aqueduct TroughDocument4 pagesDesign of Aqueduct TroughVinay Chandwani100% (1)

- Rms Auto Ut Corrosion Mapping PDFDocument6 pagesRms Auto Ut Corrosion Mapping PDFSangeeth Kavil PNo ratings yet

- Tad2 - Functional Concepts and The Interior EnvironmentDocument10 pagesTad2 - Functional Concepts and The Interior EnvironmentJay Reyes50% (2)

- CH 13 Lecture PresentationDocument97 pagesCH 13 Lecture PresentationDalia M. MohsenNo ratings yet

- Advanced Planning and SchedulingDocument7 pagesAdvanced Planning and Schedulingsheebakbs5144100% (1)

- APO SNP Training - GlanceDocument78 pagesAPO SNP Training - GlanceAshwani SharmaNo ratings yet

- CC Assignments CurrentDocument53 pagesCC Assignments Currentranjeet100% (3)

- Vendetta by Catherine Doyle EXCERPTDocument33 pagesVendetta by Catherine Doyle EXCERPTI Read YA50% (2)

- Nihms 528278Document19 pagesNihms 528278Adrian HaningNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Follow-Up of Children, Adolescents, and Young Adult Cancer SurvivorsDocument6 pagesLong-Term Follow-Up of Children, Adolescents, and Young Adult Cancer Survivorsشهر رمزحنNo ratings yet

- Cancer Patients Experiences Bad NewsDocument12 pagesCancer Patients Experiences Bad NewsDolores GalloNo ratings yet

- ST Gallen 2021 A OncologyDocument20 pagesST Gallen 2021 A OncologyJorge Apolo PinzaNo ratings yet

- Individual Management of Cervical Cancer in Pregnancy (Jurnal Ana)Document12 pagesIndividual Management of Cervical Cancer in Pregnancy (Jurnal Ana)Awilia Eka PutriNo ratings yet

- Dietary Supplement Use in Ambulatory Cancer Patients: A Survey On Prevalence, Motivation and AttitudesDocument9 pagesDietary Supplement Use in Ambulatory Cancer Patients: A Survey On Prevalence, Motivation and AttitudespilarerasoNo ratings yet

- Breast CancerDocument17 pagesBreast CancerLaura CampañaNo ratings yet

- Visceral CrisisDocument11 pagesVisceral CrisisshokoNo ratings yet

- ST Gallen 2013Document18 pagesST Gallen 2013Claudinete SouzaNo ratings yet

- Addressing Cancer Survivorship Care Under COVID 19 P - 2021 - American JournalDocument5 pagesAddressing Cancer Survivorship Care Under COVID 19 P - 2021 - American JournalEstreLLA ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Esmo Mama Metastasico 2022Document21 pagesEsmo Mama Metastasico 2022Djuvensky CharlesNo ratings yet

- Anxiety During Cancer Diagnosis - Examining The Influence of Monitoring Coping Style and Treatment PlanDocument19 pagesAnxiety During Cancer Diagnosis - Examining The Influence of Monitoring Coping Style and Treatment PlanJosé Carlos Sánchez RamírezNo ratings yet

- Cancers 13 02978 v2Document21 pagesCancers 13 02978 v2RevinandaVinaNo ratings yet

- The Lancet Volume Issue 2016 (Doi 10.1016/S0140-6736 (16) 31891-8) Harbeck, Nadia Gnant, Michael - Breast CancerDocument17 pagesThe Lancet Volume Issue 2016 (Doi 10.1016/S0140-6736 (16) 31891-8) Harbeck, Nadia Gnant, Michael - Breast CancerAlf RobNo ratings yet

- Manisfetasi Klinis Kanker PayudaraDocument7 pagesManisfetasi Klinis Kanker PayudaraRahmi Mutia UlfaNo ratings yet

- Sylvester 2018Document3 pagesSylvester 2018DavorIvanićNo ratings yet

- Artículo Terapia Fotodinámica CIN VPHDocument8 pagesArtículo Terapia Fotodinámica CIN VPHVicky SolaNo ratings yet

- ArticleText 78614 1 10 20191030Document7 pagesArticleText 78614 1 10 20191030Melody CyyNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Options For Management of Gynecologic CancersDocument4 pagesCOVID-19 Global Pandemic: Options For Management of Gynecologic CancersMuhammad FaisalNo ratings yet

- Xu 2021Document9 pagesXu 2021Drsaumyta MishraNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 695311Document19 pagesNi Hms 695311Sri WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Cancer PainDocument8 pagesDissertation On Cancer PainCollegePapersToBuySingapore100% (1)

- Breast Cancer JournalDocument14 pagesBreast Cancer JournalYASSER ALATAWINo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument26 pagesUntitledAounAbdellahNo ratings yet

- Early ViewDocument34 pagesEarly Viewyesid urregoNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal of Prognostic Study: A Prognostic Study of Patients With Cervical Cancer and HIV/ AIDS in Bangkok, ThailandDocument22 pagesCritical Appraisal of Prognostic Study: A Prognostic Study of Patients With Cervical Cancer and HIV/ AIDS in Bangkok, ThailandHappy Ary SatyaniNo ratings yet

- Breast Conserving Therapy For Central Breast Cancer in The United StatesDocument11 pagesBreast Conserving Therapy For Central Breast Cancer in The United StatesMariajanNo ratings yet

- Predictors of the risk of fibrosis at 10 years after breast conserving therapy for early breast cancer – A study based on the EORTC trial 22881–10882 ‘boost versus no boost’ / European Journal of Cancer Collette, 2008Document13 pagesPredictors of the risk of fibrosis at 10 years after breast conserving therapy for early breast cancer – A study based on the EORTC trial 22881–10882 ‘boost versus no boost’ / European Journal of Cancer Collette, 2008saipraveen03No ratings yet

- Cancer Entangled: Anticipation, Acceleration, and the Danish StateFrom EverandCancer Entangled: Anticipation, Acceleration, and the Danish StateRikke Sand AndersenNo ratings yet

- Triple Negative Breast Cancer, Experience of Military Hospital Rabat: About 52 CasesDocument10 pagesTriple Negative Breast Cancer, Experience of Military Hospital Rabat: About 52 CasesIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer in The Pregnant PopulationDocument15 pagesCervical Cancer in The Pregnant PopulationLohayne ReisNo ratings yet

- ST Gallen 1988Document5 pagesST Gallen 1988Nicola CrestiNo ratings yet

- Djaa 048Document17 pagesDjaa 048Satra Azmia HerlandaNo ratings yet

- Granulomatous Mastitis: Etiology, Imaging, Pathology, Treatment, and Clinical FindingsDocument8 pagesGranulomatous Mastitis: Etiology, Imaging, Pathology, Treatment, and Clinical FindingsAlejandro Abarca VargasNo ratings yet

- Gemcitabine Vs BCGDocument8 pagesGemcitabine Vs BCGmulkikimulNo ratings yet

- Review: Second Consensus On Medical Treatment of Metastatic Breast CancerDocument11 pagesReview: Second Consensus On Medical Treatment of Metastatic Breast Cancermohit.was.singhNo ratings yet

- 10 11648 J Ejpm 20140203 11Document4 pages10 11648 J Ejpm 20140203 11intansarifnosaaNo ratings yet

- Nursing Proces NewDocument10 pagesNursing Proces NewBrandy SangurahNo ratings yet

- In The Literature: Palliative Care in CKD: The Earlier The BetterDocument3 pagesIn The Literature: Palliative Care in CKD: The Earlier The BetterMaria ImakulataNo ratings yet

- A New Treatment Method of Advanced Metastic TumorsDocument7 pagesA New Treatment Method of Advanced Metastic TumorsDiana DíazNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0422763815301023 MainDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S0422763815301023 MainEghar EverydayishellNo ratings yet

- Pone 0221946Document15 pagesPone 0221946Nur Laila SafitriNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer in Pregnancy A Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesBreast Cancer in Pregnancy A Literature Reviewgvzwyd4n100% (1)

- Metastasis Patterns and PrognoDocument17 pagesMetastasis Patterns and Prognosatria divaNo ratings yet

- Fungating Breast Cancer Di Pelayanan Perawatan Paliatif: Literature ReviewDocument14 pagesFungating Breast Cancer Di Pelayanan Perawatan Paliatif: Literature ReviewAnna Fi'ulNo ratings yet

- Weeks 2016Document15 pagesWeeks 2016InêsNo ratings yet

- Medi 97 E11220Document9 pagesMedi 97 E11220iraNo ratings yet

- Mangacu (Cancer Journal)Document2 pagesMangacu (Cancer Journal)Diana Rose MangacuNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1526820922000647 MainDocument16 pages1 s2.0 S1526820922000647 MainMarina UlfaNo ratings yet

- 329-Article Text-1733-1-10-20211207Document10 pages329-Article Text-1733-1-10-20211207antaresNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Global Pandemic: Options For Management of Gynecologic CancersDocument4 pagesCOVID-19 Global Pandemic: Options For Management of Gynecologic CancersRendyNo ratings yet

- ArticuloDocument9 pagesArticulodrjlgf7No ratings yet

- Anxiety and Depression Comorbidities in Moroccan Patients With Breast CancerDocument7 pagesAnxiety and Depression Comorbidities in Moroccan Patients With Breast CancerNabila ChakourNo ratings yet

- Reflection Paper Pediatric Community-Acquired Pneumonia in The United StatesDocument3 pagesReflection Paper Pediatric Community-Acquired Pneumonia in The United StatesLecery Sophia WongNo ratings yet

- COGNITION A Prospective Precision Oncology TrialDocument12 pagesCOGNITION A Prospective Precision Oncology Trialveaceslav coscodanNo ratings yet

- OutDocument10 pagesOutErwinNo ratings yet

- Anatomy and Breast Cancer STAGINGDocument17 pagesAnatomy and Breast Cancer STAGINGVikash SinghNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated ReviewDocument30 pagesBreast Cancer-Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Classification, Prognostic Markers, and Current Treatment Strategies-An Updated ReviewTrịnhÁnhNgọcNo ratings yet

- ESGOESTROESP Guidelines For The Management of Patients With Cervical Cancer - Update 2023Document32 pagesESGOESTROESP Guidelines For The Management of Patients With Cervical Cancer - Update 2023Limbert Rodríguez TiconaNo ratings yet

- 1019 5298 1 PBDocument11 pages1019 5298 1 PBm907062008No ratings yet

- Martinal LEO - Product RangeDocument6 pagesMartinal LEO - Product RangeAdamMitchellNo ratings yet

- Astm C 22C 22MDocument2 pagesAstm C 22C 22MProfessor Dr. Nabeel Al-Bayati-Consultant EngineerNo ratings yet

- Conference Tool Setup - RuckusDocument11 pagesConference Tool Setup - RuckusJohn MontuyaNo ratings yet

- Class6 Assignment10 2022-23Document29 pagesClass6 Assignment10 2022-23Debaprasad MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Who Can Learn Diploma CivilDocument19 pagesWho Can Learn Diploma CivilGururaj TavildarNo ratings yet

- Epson C82 Service ManualDocument48 pagesEpson C82 Service ManualPablo RothNo ratings yet

- Pierson's Puppeteer R.C.C.Document6 pagesPierson's Puppeteer R.C.C.Strider KageNo ratings yet

- C O P D: Hronic Bstructive Ulmonary IseaseDocument53 pagesC O P D: Hronic Bstructive Ulmonary IseaseLe KhoaNo ratings yet

- Design of BeamsDocument112 pagesDesign of BeamskbkwebsNo ratings yet

- Student Exploration: HomeostasisDocument3 pagesStudent Exploration: HomeostasisJordan TorresNo ratings yet

- Martin Gwapo JheroDocument8 pagesMartin Gwapo Jherokent baboys19No ratings yet

- Manual of Microbiological Culture Media - 9Document1 pageManual of Microbiological Culture Media - 9Amin TaleghaniNo ratings yet

- CM (1921) Monthly Test-1 - Off LineDocument20 pagesCM (1921) Monthly Test-1 - Off Linemehul pantNo ratings yet

- Chinese Journal of Chemistry, 31 (1), 15-17 (2013) - DrospirenoneDocument3 pagesChinese Journal of Chemistry, 31 (1), 15-17 (2013) - DrospirenoneSam SonNo ratings yet

- Method Statement KOM HG - 01Document15 pagesMethod Statement KOM HG - 01Hussain GodhrawalaNo ratings yet

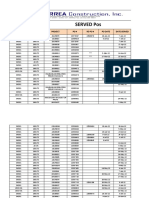

- Served POsDocument21 pagesServed POsYay DumaliNo ratings yet

- ENSTO клеммыDocument92 pagesENSTO клеммыenstospbNo ratings yet

- SLB Lean Level 2 Module 19 TestDocument3 pagesSLB Lean Level 2 Module 19 TestEdiith CarvajalNo ratings yet

- Secondary Steering PumpDocument5 pagesSecondary Steering PumpStar SealNo ratings yet

- 7.6.2. Poly-Silicon Gate TechnologyDocument14 pages7.6.2. Poly-Silicon Gate TechnologyHarshad KulkarniNo ratings yet