Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols

Uploaded by

on miniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocols

Uploaded by

on miniCopyright:

Available Formats

review

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols:

Time to change practice?

Megan Melnyk, MSc, MD; Rowan G. Casey, MBChB, MD, FRCS(Urol); Peter Black, MD, FRCSC, FACS;

Anthony J. Koupparis, MBChB MD FRCS(Urol)

Department of Urological Sciences, University of British Columbia, Gordon & Leslie Diamond Health Care Centre, Vancouver, BC

Cite as: Can Urol Assoc J 2011;5(5): 342-8;DOI:10.5489/cuaj.11002

early recovery after surgical procedures by maintaining pre-

operative organ function and reducing the profound stress

Abstract response following surgery. The key elements of ERAS proto-

Radical cystectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection remains cols include preoperative counselling, optimization of nutri-

the standard treatment for patients with muscle invasive bladder tion, standardized analgesic and anesthetic regimens and

cancer. Despite improvements in surgical technique, anesthe- early mobilization.4-8 Despite the significant body of evi-

sia and perioperative care, radical cystectomy is still associated dence indicating that ERAS protocols lead to improved out-

with greater morbidity and prolonged in-patient stay after surgery comes,9,10 they challenge traditional surgical doctrine, and as

than other urological procedures. Enhanced recovery after sur- a result their implementation has been slow. Although much

gery (ERAS) protocols are multimodal perioperative care pathways of the data arise from colorectal surgery, the evidence is

designed to achieve early recovery after surgical procedures by applicable to major urological surgery, in particular radical

maintaining preoperative organ function and reducing the pro- cystectomy. The present article discusses particular aspects

found stress response following surgery. The key elements of ERAS

of ERAS protocols which represent fundamental shifts in

protocols include preoperative counselling, optimization of nutri-

surgical practice, including perioperative nutrition, manage-

tion, standardized analgesic and anesthetic regimens and early

mobilization. Despite the significant body of evidence indicating ment of postoperative ileus and the use of mechanical bowel

that ERAS protocols lead to improved outcomes, they challenge preparation.

traditional surgical doctrine, and as a result their implementation

has been slow. What is ERAS?

The present article discusses particular aspects of ERAS proto-

cols which represent fundamental shifts in surgical practice, includ- Initiated by Professor Henrik Kehlet in the 1990s,11 ERAS,

ing perioperative nutrition, management of postoperative ileus and enhanced recovery programs (ERPs) or “fast-track” programs

the use of mechanical bowel preparation. have become an important focus of perioperative manage-

ment after colorectal surgery,12 vascular surgery,13 thoracic

surgery14 and more recently radical cystectomy.7,8,15 These

Introduction programs attempt to modify the physiological and psycho-

logical responses to major surgery,16 and have been shown

Radical cystectomy with pelvic lymph node dissection to lead to a reduction in complications and hospital stay,

remains the standard treatment for patients with muscle improvements in cardiopulmonary function, earlier return

invasive bladder cancer.1 Despite improvements in surgi- of bowel function and earlier resumption of normal activi-

cal technique, anesthesia and perioperative care, radical ties.9,10 The key principles of the ERAS protocol include pre-

cystectomy is still associated with greater morbidity and operative counselling , preoperative nutrition, avoidance of

prolonged in-patient stay after surgery than other urological perioperative fasting and carbohydrate loading up to 2 hours

procedures. Overall complication rates have been reported preoperatively, standardized anesthetic and analgesic regi-

as high as 64% at 90 days,2 with an average in-patient stay mens (epidural and non-opiod analgesia) and early mobili-

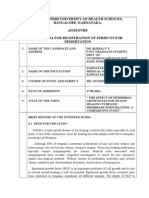

of 17.4 days.3 zation (Fig. 1).17 There are relatively few reports on the use

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols are of ERAS in urological surgery. The introduction of ERAS in a

multimodal perioperative care pathways designed to achieve centre in the United Kingdom lead to a significant reduction

342 CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5

© 2011 Canadian Urological Association

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 342 9/30/11 4:01 PM

Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols

in hospital stay and equivalent morbidity in radical cystec- one or more of the following: weight loss >10% to 15% in 6

tomy patients, compared to traditional approaches.7,15 The months, body mass index <18.5 kg/m2 or a serum albumin

protocol focused on reduced bowel preparation, standard- of <30 g/L.17 The British Association of Parenteral and Enteral

ized feeding schedule and standardized analgesic regimens uses similar parameters as part of the Malnutrition Universal

(Table 1). Similar findings have been replicated in a small Screening Tool (MUST) to risk stratify patients according to

number of other urological publications.18,19 their nutritional level. What is interesting when considering

the patients who undergo radical cystectomy is how many

Perioperative nutrition would be classified as high risk or severe nutritional risk after

appropriate assessment. Correction of preoperative nutri-

tional deficiencies may sometimes require prolonged par-

Preoperative nutrition enteral, or a combination of parenteral and enteral nutrition

depending on the severity of the problem and the patient’s

It is well-known that poor nutrition is detrimental to out- gastrointestinal function. However, in most cases patients

comes postoperatively.20,21 It frequently occurs with comor- can be managed with appropriate input from a dietician or

bidities and with underlying disease processes, such as can- nutritionist, and the use of a standard whole protein liquid

cer.22 Inadequate nutrition, particularly for cancer patients nutritional supplement.

undergoing surgery, is an independent risk factor for compli-

cations, increased hospital stay and costs.23 The importance Carbohydrate loading and early enteral feeding

of nutritional status in patients undergoing radical cystec-

tomy has long been noted,24 with reported complications The stress response is initiated by a variety of physical

rates as high as 80% in patients with poor nutrition.25 More insults, such as tissue injury, infection, hypovolemia or

recently, data from Vanderbilt University demonstrate that hypoxia. The ERAS program is aimed at attenuating the

nutritional deficiency preoperatively is a strong predictor of body’s response to surgery which is characterized by its

90-day mortality and poor overall survival.26 It is therefore catabolic effect.27 Autonomic afferent impulses from the area

unsurprising that assessment and treatment of poor nutrition of injury or trauma stimulate the hypothalamus-pituitary-

is an essential component of ERAS protocols. In terms of adrenal axis and mediate the body’s subsequent endocrine

defining the problem, the European Society of Parenteral and response.28 Increased cortisol levels stimulate gluconeo-

Enteral Nutrition (ESPEN) defines “severe” nutritional risk as genesis and glyconeogenesis in the liver, with triglyercides

Table 1. An enhanced recovery after surgery for radical cystectomy ± neobladder focusing on reduced bowel preparation

and standardized feeding and analgesic regimens

Day before radical cystectomy Day 3 and 4

- Normal breakfast - Remove epidural on day 3

- Admit to hospital - Continue to mobilize and encourage self-care

- Unrestricted clear fluids - Light diet as tolerated

- Refer to dietician - Start planning for discharge

- Stoma therapist to see patient

- Assess social circumstances and refer if needed

Day of radical cystectomy Day 5, 6 and 7

- Clear carbohydrate drinks up to 2 hours before surgery, - Dietician to assess nutritional requirements on day 5

then nil by mouth - If a patient is not eating or drinking after 5 to 6 days,

- Restart clear fluids as tolerated when in recovery but with bowel activity, then start nasogastric feeding

- Start food chart - If there is no bowel activity then start total parenteral nutrition

- Epidural analgesia in situ

After radical cystectomy: Day 1 Day 8

- Free fluids as tolerated - Stents out (no stentogram)

- Female patients, remove vaginal pack

- Mobilize and refer to physiotherapist Day 10

- Ranitidine 3 times daily intravenously or twice daily orally - Remove clips

- Remove drain if draining <50 mL in 24 hours

- Flush 20 mL into neobladder, twice hourly for 12 hours

and then 4 times hourly

Day 2 Day 11 to 14

- Light diet as tolerated - Continue as previous and schedule for return to home

- Mobilize and encourage self-care (catheter care/flushing in

neobladders, and stoma bag emptying in patients with a

conduit)

CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5 343

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 343 9/30/11 4:01 PM

Melnyk et al.

Mid-thoracic epidural anesthesia/analgesia Preadmission counselling

No nasogastric tubes Fluid and carbohydrate loading

Prevention of nausea and vomiting No prolonged fasting

Avoidance of salt and water overload No/selective bowel preparation

Early removal of catheter Antibiotic prophylaxis

Early oral nutrition Thromboprophylaxis

Postoperative Preoperative

Non-opioid oral analgesia/NSAIDS No premedication

Early mobilization ERAS

Short-acting anesthetic agents

Stimulation of gut motility Intraoperative

Mid-thoracic epidural

Audit of compliance and outcomes anesthesia/analgesia

No drains

Avoidance of salt and water overload

Maintenance of normothermia (body warmer/warm intravenous fluids)

Fig. 1. Key aspects of ERAS protocols. Adapted from Donat et al. Early nasogastric tube removal combined with metoclopramide after radical cystectomy and

urinary diversion. J Urol 1999;162:1599-602.70

being converted to glycerol and fatty acids providing the regurgitation or related morbidity compared to the standard

substrates for gluconeogensis. Adrenocorticotropic hormone fasting from midnight policy.36 Furthermore, if patients are

and cortisol production leads to protein catabolism, weight allowed to take solids up to 6 hours preoperatively and

loss, muscle (skeletal and visceral) wasting and nitrogenous clear fluids up to 2 hours, there is no increase in complica-

loss.27 There is also a relative lack of insulin and peripheral tions,36,37 which forms the basis of preoperative guidelines

insulin resistance occurs due to alpha-2-adrenergic inhibi- adopted by the Royal College of Anaesthetists38 and the

tion of pancreatic B cells (facilitated by catecholamines) American Society of Anesthesiologists.39

and defects in the insulin receptor/intracellular signalling As mentioned previously, the use of carbohydrate loading

pathway. Hyperglycaemia is therefore a significant finding attenuates postoperative insulin resistance, reduces nitro-

after cystectomy,29 and the observed insulin resistance is gen and protein losses,40,41 preserves skeletal muscle mass

a major variable influencing length of stay,30 poor wound and reduces preoperative thirst, hunger and anxiety.42-44 It

healing and increased risk of infective complications. The involves the use of clear carbohydrate drinks the day prior

degree of insulin resistance is associated with the extent of to surgery and up to 2 hours before. In addition to the meta-

surgery, and if postoperative hyperglycaemia is controlled, bolic effects, it facilitates accelerated recovery through early

mortality and morbidity can be reduced by half.31 Methods return of bowel function and shorter hospital stay, ultimately

which reduce the insulin resistance include adequate pain leading to an improved perioperative well-being.45-47 As a

relief,32,33 avoiding a prolonged period when oral intake is result, it is an important element of the nutritional aspects of

interrupted, and the use of carbohydrate loading. ERAS and should replace the practice of overnight fasting.

The practice of fasting patients from midnight is used to

avoid pulmonary aspiration after elective surgery; however, Role of mechanical bowel preparation

there is no evidence to support this.34 Preoperative fasting

actually increases the metabolic stress, hyperglycemia and The routine use of preoperative mechanical bowel prepara-

insulin resistance, which the body is already prone to dur- tion (MBP) has long been a tradition in colorectal surgery;

ing the surgical process.30 Changing the metabolic state of due to the use of bowel segments, MBP is used routinely

patients by shortening preoperative fasting not only decreas- for radical cystectomy patients. The aim of MBP is to rid the

es insulin resistance, but reduces protein loss and improves large bowel of solid fecal contents and to lower the bacterial

muscle function.35 A review of 22 RCTs comparing differ- load, thereby reducing the incidence of postoperative com-

ent perioperative fasting regimens and perioperative com- plications. However, MBP liquefies solid faeces, which may

plications revealed that there is no evidence to suggest a increase the risk of intra-operative spillage of contaminant,

shortened fluid fast results in an increased risk of aspiration, and it is almost impossible to reduce the bacterial load in the

344 CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 344 9/30/11 4:01 PM

Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols

bowel due to the vast number of micro-organisms present trend towards a lower incidence of anastomotic dehiscence,

in the digestive tract.48 wound infection, pneumonia, intra-abdominal abscess or

The routine practice of MBP has been challenged for over mortality in patients who received early enteral feeding. A

30 years. In 1972, Hughes originally questioned MBP and Cochrane review in 2006 found a direction of effect towards

concluded that vigorous mechanical bowel preparation is a reduction in complications and mortality rate,65 and in an

unnecessary.49 Not only does MBP cause metabolic and update to their original metanalysis, Lewis and colleagues

electrolyte imbalance, dehydration, abdominal pain/bloating confirmed no benefit to keeping patients nothing by mouth

and fatique,50-53 but it may actually have detrimental effects (NBM) postoperatively, a reduction in complications and a

on surgical outcome.54 Multiple RCTs and meta-analyses reduced mortality rate; although, the mechanism for reduced

have been published over the last decade suggesting that it mortality remains unclear.66

is safe to abandon MBP.54-59 One of the largest RCTs from

Denmark was published in 2007.60 The primary objective Prevention of prolonged postoperative ileus

was to assess the outcome of elective colorectal resections

with or without MBP. The authors examined 1431 patients Bowel complications, and particularly paralytic ileus, are

at 13 colorectal centres and found no difference in anas- among the most common problems following radical cys-

tamotic leakage, septic complications, fascial dehiscence tectomy.3,7,67,68 The etiology of postoperative ileus is multi-

or mortality between the groups. In addition to an absence factoral, with bowel function relying on a combination of

of benefit, MBP is also likely associated with an increased the enteric and central nervous systems, hormonal influ-

risk of complications, particularly anastamostic leakage.59 ences, neurotransmitters and local inflammatory pathways.69

A meta-analysis of 10 trials and nearly 2000 patients pub- Surgical stress, bowel handling, opioids and intraoperative

lished in 2007, not only found an increased incidence of fluid resuscitation can disrupt these normal arrangements

anastamotic leaks and wound infections, but also a trend within the gastrointestinal tract and lead to postoperative

toward increased incidence of intra-abdominal abscesses and ileus and impaired gastrointestinal absorptive function.64

extradigestive complications.54 With this in mind, Slim and Factors that help reduce this include epidural anesthesia,

colleagues published an updated meta-analysis and review minimally invasive surgery, gentle tissue handling, avoiding

of the literature which included 14 RCTs and nearly 5000 of fluid overload70 and early feeding.18,71 Furthermore, the

patients.61 Although it did not confirm the harmful effect of use of routine nasogastric decompression should be avoid-

MBP as previously suggested, it demonstrated that any kind ed after surgery as the incidence of fever, atelectasis and

of MBP can safely be omitted before colonic surgery. pneumoniae are increased in patients with nasogastric tube

In terms of radical cystectomy, Shafii and colleagues con- drainage, and any nasogastric tubes placed during surgery

ducted a retrospective study assessing no bowel prepara- should be removed prior to extubation.10,72

tion versus bowel preparation before cystectomy and urinary Chewing gum has previously been used in an attempt

diversion. They authors concluded that in the group who to improve the postoperative recovery of bowel function

received MBP, there was a higher incidence postoperative in patients. Chewing gum in the postoperative period has

ileus, slower commencement of diet, greater risk of wound been described as a form of sham feeding,73 whereby a

dehiscence and longer hospital stay (31.6 vs. 22.8 days) food substance is chewed but does not enter the stomach.

compared to the group who did not receive MBP.62 Gum is postulated to increase cephalo-vagal stimulation,

leading to increased gastric motility and reduced inhibitory

Postoperative nutrition inputs from the sympathetic nervous system. Gastrointestinal

hormones, such as gastrin, neurotensin, cholecystokinin

In addition to preoperative carbohydrate loading, early pos- and pancreatic polypeptide, are also increased and result

toperative nutrition can ameliorate the metabolic response in vagal stimulation of smooth muscle fibres.74 Chewing

leading to less insulin resistance, lower nitrogen losses and gum also increases secretion of saliva and pancreatic juices,

reduce the loss of muscle strength.63,64 An assessment of and a recent study proposed that sorbitol and hexitol found

gastrointestinal function and patient tolerability is essential in sugar-free gum may also play a role in the reduction

when commencing postoperative oral intake. Multiple stud- of postoperative ileus.75 A number of studies exist which

ies exist on the timing of post-operative nutrition. One of demonstrate the benefits in patients undergoing colorectal

the early meta-analyses, although relatively small, found surgery.73,74,76-78 A meta-analysis of several RCTs evaluating

that there is no advantage in keeping patients nil by mouth the effect of chewing gum on postoperative ileus has sub-

after elective gastrointestinal resection and early feeding may sequently been published. Although there are relatively low

actually be beneficial by reducing infectious complications patient numbers and a significant heterogeneity of studies,

and length of hospital stay.63 Lewis and colleagues dem- chewing gum offers significant benefits by reducing the time

onstrated no detrimental effect with early feeding, but a to pass flatus and the time until first bowel movement.79-82

CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5 345

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 345 9/30/11 4:01 PM

Melnyk et al.

The use of bowel segments in the reconstruction of the Conclusions

urinary tract after cystectomy lead Kouba and colleagues to

examine the use of chewing gum following cystectomy.83 Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols were initially

The time to flatus was shorter in patients who received gum described in open colorectal surgery, but have since been

compared with controls (2.4 vs. 2.9 days). Also, time to studied in a variety of surgical specialties, including urology.

bowel movement was reduced in patients who received Although growing evidence from several RCTs, systematic

gum (3.2 vs. 3.9 days). There was no significant difference reviews and meta-analyses suggest significant benefits from

in length of hospital stay between gum-chewing patients ERAS pathways, there are still major difficulties when intro-

and controls (4.7 vs. 5.1 days). A similar picture was noted ducing these evidence-based guidelines into routine prac-

by Koupparis and colleagues who examined the addition of tice.9,84,87 The fact that less than half of patients are involved

chewing gum postoperatively to their established enhanced in a postoperative care pathway suggests that perioperative

recovery program.15 The authors noted a significant reduc- care continues to resemble traditional and conventional atti-

tion in the duration of postoperative ileus, but with only a tudes.88,89 Many surgeons state that they have “never heard

trend towards a reduced in-patient stay. of ERAS,” while others cite inadequate multidisciplinary and

community support as an impediment to implementation.90

Health economic benefits In terms of barriers to introducing ERAS, even the simple

measures discussed in this review still represent fundamental

The implementation of ERAS protocols represents a signifi- changes in practice, and can therefore be difficult to achieve.

cant change in practice and a potential increase in the use of Kahokher and colleagues outlined the key aspects required

resources. Certain aspects, such as chewing gum, represent a for the implementation of an ERAS protocol.91 One of the

simple and cheap intervention, which could potentially lead most important aspects is the ERAS team, which includes

to significant cost savings. Schuster and colleagues estimated pre-admission staff, dieticians, nurses, physiotherapists,

that the use of chewing gum following colectomy could save social workers, occupational therapists and doctors. All team

$118 828 000 per year in the United States.76 However, few members must be familiar ERAS principles and be motiv-

studies have examined the impact of introducing an ERAS ated to carry out the program; they must be able to over-

program on quality of life or health economic outcomes come traditional concepts, teaching and attitudes towards

in the months after surgery. The benefits of ERAS will be perioperative care. In light of such compelling evidence, the

markedly reduced if the costs are simply transferred to the evidence-based environment in which we practice demands

community or if patients suffer a greater deterioration in that we review the perioperative management of radical

quality of life than is experienced with conventional care. cystectomy patients and alter it accordingly.

King and colleagues examined information regarding in-

patient days, out-patient and general practitioner visits and Competing interests: None declared.

the use of community services and estimated costs from

national published figures.84 Direct medical and indirect

non-medical costs were significantly lower in the ERAS This paper has been peer-reviewed.

group. Similarly, Sammour and colleagues have recently

published a cost-analysis of ERAS in colorectal surgery.85

They evaluated whether costs saved by reduced postopera- References

tive resource utilization would offset the financial burden

of setting up and maintaining such an ERAS program. There 1. Ghoneim MA, el-Mekresh MM, el-Baz MA, el-Attar IA, Ashamallah A. Radical cystectomy for carcinoma of

the bladder: critical evaluation of the results in 1,026 cases. J Urol 1997;158:393-9.

was a significant reduction in total hospital stay, intravenous

2. Shabsigh A, Korets R, Vora KC, et al. Defining early morbidity of radical cystectomy for patients with

fluid use, complications and duration of epidural use in bladder cancer using a standardized reporting methodology. Eur Urol 2009;55:164-74.

the ERAS group. The implementation of an ERAS program 3. Novotny V, Hakenberg OW, Wiessner D, et al. Perioperative complications of radical cystectomy in a

costs about $102 000, but this was offset by costs saved in contemporary series. Eur Urol 2007;51:397-401; discussion 01-2.

reduced postoperative resource utilization, with an overall 4. Wilmore DW, Kehlet H. Management of patients in fast track surgery. BMJ 2001;322:473-6.

5. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg 2002;183:630-41.

cost-saving of roughly $6900 per patient.

6. Kehlet H, Dahl JB. Anaesthesia, surgery, and challenges in postoperative recovery. Lancet 2003;362:1921-8.

An ongoing trial is the Tapas-study. It was conceived 7. Arumainayagam N, McGrath J, Jefferson KP, et al. Introduction of an enhanced recovery protocol for

to determine which of the three treatment programs (open radical cystectomy. BJU Int 2008;101:698-701.

conventional surgery, open “ERAS” surgery or laparoscopic 8. Kehlet H, Mogensen T. Hospital stay of 2 days after open sigmoidectomy with a multimodal rehabilitation

“ERAS” surgery for patients with colon carcinomas) is the programme. Br J Surg 1999;86:227-30.

9. Eskicioglu C, Forbes SS, Aarts MA, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs for patients

most cost-effective.86 Primary outcome parameters are direct

having colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:2321-9.

medical costs and indirect non-medical costs, with the aim 10. Lassen K, Soop M, Nygren J, et al. Consensus review of optimal perioperative care in colorectal surgery:

of directing future investment appropriately. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group recommendations. Arch Surg 2009;144:961-9.

346 CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 346 9/30/11 4:01 PM

Enhanced recovery after surgery protocols

11. Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. Br J Anaesth 42. Nygren J, Soop M, Thorell A, et al. Preoperative oral carbohydrate administration reduces postoperative

1997;78:606-17. insulin resistance. Clin Nutr 1998;17:65-71.

12. Wind J, Polle SW, Fung Kon Jin PH, et al. Systematic review of enhanced recovery programmes in colonic 43. Soop M, Nygren J, Thorell A, et al. Preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment attenuates endogenous

surgery. Br J Surg 2006;93:800-9. glucose release 3 days after surgery. Clin Nutr 2004;23:733-41.

13. Podore PC, Throop EB. Infrarenal aortic surgery with a 3-day hospital stay: A report on success with a 44. Soop M, Myrenfors P, Nygren J, et al. Preoperative oral carbohydrate intake attenuates metabolic changes

clinical pathway. J Vasc Surg 1999;29:787-92. immediately after hip replacement. Clinical Nutrition 1998;17(Supp 1):3-4.

14. Tovar EA, Roethe RA, Weissig MD, et al. One-day admission for lung lobectomy: an incidental result of a 45. Nygren J, Thorell A, Ljungqvist O. Preoperative oral carbohydrate nutrition: an update. Curr Opin Clin Nutr

clinical pathway. Ann Thorac Surg 1998;65:803-6. Metab Care 2001;4:255-9.

15. Koupparis A, Dunn J, Gillatt D, et al. Improvement of an enhanced recovery protocol for radical cystecomy. 46. Hausel J, Nygren J, Lagerkranser M, et al. A carbohydrate-rich drink reduces preoperative discomfort in

British Journal of Medical and Surgical Urology 2010;3:237-40. elective surgery patients. Anesth Analg 2001;93:1344-50.

16. Fearon KC, Ljungqvist O, Von Meyenfeldt M, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery: a consensus review 47. Noblett SE, Watson DS, Huong H, et al. Pre-operative oral carbohydrate loading in colorectal surgery: a

of clinical care for patients undergoing colonic resection. Clin Nutr 2005;24:466-77. randomized controlled trial. Colorectal Dis 2006;8:563-9.

17. Weimann A, Braga M, Harsanyi L, et al. ESPEN Guidelines on Enteral Nutrition: Surgery including organ 48. Mahajna A, Krausz M, Rosin D, et al. Bowel preparation is associated with spillage of bowel contents in

transplantation. Clin Nutr 2006;25:224-44. colorectal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum 2005;48:1626-31.

18. Pruthi RS, Chun J, Richman M. Reducing time to oral diet and hospital discharge in patients undergoing 49. Hughes ES. Asepsis in large-bowel surgery. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1972;51:347-56.

radical cystectomy using a perioperative care plan. Urology 2003;62:661-5; discussion 65-6. 50. Beloosesky Y, Grinblat J, Weiss A, et al. Electrolyte disorders following oral sodium phosphate administra-

19. Pruthi RS, Nielsen M, Smith A, et al. Fast track program in patients undergoing radical cystectomy: results tion for bowel cleansing in elderly patients. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:803-8.

in 362 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg 2010;210:93-9. 51. Frizelle FA, Colls BM. Hyponatremia and seizures after bowel preparation: report of three cases. Dis

20. Durkin MT, Mercer KG, McNulty MF, et al. Vascular surgical society of great britain and ireland: contribu- Colon Rectum 2005;48:393-6.

tion of malnutrition to postoperative morbidity in vascular surgical patients. Br J Surg 1999;86:702. 52. Beck DE. Mechanical bowel cleansing for surgery. Perspect Colon Rectal Surg 1994;7:97-114.

21. van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA, van Leeuwen PA, Sauerwein HP, et al. Assessment of malnutri- 53. Kim HJ, Yoon YM, Park KN. The changes in electrolytes and acid-base balance after artificially induced

tion parameters in head and neck cancer and their relation to postoperative complications. Head Neck acute diarrhea by laxatives. J Korean Med Sci 1994;9:388-93.

1997;19:419-25. 54. Bucher P, Mermillod B, Gervaz P, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a

22. Von Meyenfeldt MF, Meijerink WJ, Rouflart MM, et al. Perioperative nutritional support: a randomised meta-analysis. Arch Surg 2004;139:1359-64; discussion 65.

clinical trial. Clin Nutr 1992;11:180-6. 55. Brownson P, Jenkins SA, Nott D. Mechanical bowel preparation before colorectal surgery: results of a

23. Correia MI, Caiaffa WT, da Silva AL, et al. Risk factors for malnutrition in patients undergoing gastroen- prospective randomized trial. Br J Surg 1992;79:461-2.

terological and hernia surgery: an analysis of 374 patients. Nutr Hosp 2001;16:59-64. 56. Santos JC Jr, Batista J, Sirimarco MT, et al. Prospective randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation

24. Mohler JL, Flanigan RC. The effect of nutritional status and support on morbidity and mortality of bladder in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 1994;81:1673-6.

cancer patients treated by radical cystectomy. J Urol 1987;137:404-7. 57. Miettinen RP, Laitinen ST, Makela JT, et al. Bowel preparation with oral polyethylene glycol electrolyte

25. Herranz Amo F, Garcia Peris P, Jara Rascon J, et al. [Usefulness++ of total parenteral nutrition in radical solution vs. no preparation in elective open colorectal surgery: prospective, randomized study. Dis Colon

surgery for bladder cancer]. Actas Urol Esp 1991;15:429-36. Rectum 2000;43:669-75; discussion 75-7.

26. Gregg JR, Cookson MS, Phillips S, et al. Effect of preoperative nutritional deficiency on mortality after 58. Zmora O, Mahajna A, Bar-Zakai B, et al. Colon and rectal surgery without mechanical bowel preparation:

radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. J Urol 2011;185:90-6. a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg 2003;237:363-7.

27. Desborough JP. The stress response to trauma and surgery. Br J Anaesth 2000;85:109-17. 59. Bucher P, Gervaz P, Soravia C, et al. Randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation versus no

28. Hall GM. The anaesthetic modffication of the endocrine and metabolic response to surgery. The Annals preparation before elective left-sided colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2005;92:409-14.

of The Royal College of Surgeons of England 1985;67:25-29. 60. Contant CM, Hop WC, van’t Sant HP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery:

29. Mathur S, Plank LD, Hill AG, et al. Changes in body composition, muscle function and energy expenditure a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 2007;370:2112-7.

after radical cystectomy. BJU Int 2008;101:973-7; discussion 77. 61. Slim K, Vicaut E, Launay-Savary M-V, et al. Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized

30. Thorell A, Nygren J, Ljungqvist O. Insulin resistance: a marker of surgical stress. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Clinical Trials on the Role of Mechanical Bowel Preparation Before Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg

Metab Care 1999;2:69-78. 2009;249:203-9.

31. van den Berghe G, Wouters P, Weekers F, et al. Intensive insulin therapy in the critically ill patients. N 62. Shafii M, Murphy DM, Donovan MG, et al. Is mechanical bowel preparation necessary in patients undergo-

Engl J Med 2001;345:1359-67. ing cystectomy and urinary diversion? BJU Int 2002;89:879-81.

32. Greisen J, Juhl CB, Grofte T, et al. Acute pain induces insulin resistance in humans. Anesthesiology 63. Lewis SJ, Egger M, Sylvester PA, Thomas S. Early enteral feeding versus “nil by mouth” after gastrointes-

2001;95:578-84. tinal surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. BMJ 2001;323:773-6.

33. Uchida I, Asoh T, Shirasaka C, et al. Effect of epidural analgesia on postoperative insulin resistance as 64. Correia MI, da Silva RG. The impact of early nutrition on metabolic response and postoperative ileus. Curr

evaluated by insulin clamp technique. Br J Surg 1988;75:557-62. Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2004;7:577-83.

34. Crowe PJ, Dennison A, Royle GT. The effect of pre-operative glucose loading on postoperative nitrogen 65. Andersen HK, Lewis SJ, Thomas S. Early enteral nutrition within 24h of colorectal surgery versus later

metabolism. Br J Surg 1984;71:635-7. commencement of feeding for postoperative complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006:CD004080.

35. Ljungqvist O, Soreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg 2003;90:400-6. 66. Lewis SJ, Andersen HK, Thomas S. Early enteral nutrition within 24 h of intestinal surgery versus later

36. Brady M, Kinn S, Stuart P. Preoperative fasting for adults to prevent perioperative complications. Cochrane commencement of feeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2009;13:569-75.

Database Syst Rev 2003:CD004423. 67. Resnick J, Greenwald DA, Brandt LJ. Delayed gastric emptying and postoperative ileus after nongastric

37. Brady M, Kinn S, O’Rourke K, et al. Preoperative fasting for preventing perioperative complications in abdominal surgery: part II. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:934-40.

children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD005285. 68. Resnick J, Greenwald DA, Brandt LJ. Delayed gastric emptying and postoperative ileus after nongastric

38. Anaesthetists TRCo. Guidance on the provision of anaesthesia services for Pre-operative Care, 2009. abdominal surgery: part I. Am J Gastroenterol 1997;92:751-62.

39. Practice guidelines for preoperative fasting and the use of pharmacologic agents to reduce the risk of pul- 69. Luckey A, Livingston E, Tache Y. Mechanisms and treatment of postoperative ileus. Arch Surg

monary aspiration: application to healthy patients undergoing elective procedures: a report by the American 2003;138:206-14.

Society of Anesthesiologist Task Force on Preoperative Fasting. Anesthesiology 1999;90:896-905. 70. Varadhan KK, Lobo DN, Ljungqvist O. Enhanced recovery after surgery: the future of improving surgical

40. Svanfeldt M, Thorell A, Hausel J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of preoperative oral carbohy- care. Crit Care Clin 2010;26:527-47, x.

drate treatment on postoperative whole-body protein and glucose kinetics. Br J Surg 2007;94:1342-50. 71. Donat SM, Slaton JW, Pisters LL, et al. Early nasogastric tube removal combined with metoclopramide

41. Soop M, Carlson GL, Hopkinson J, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effects of immediate enteral after radical cystectomy and urinary diversion. J Urol 1999;162:1599-602.

nutrition on metabolic responses to major colorectal surgery in an enhanced recovery protocol. Br J Surg 72. Inman BA, Harel F, Tiguert R, et al. Routine nasogastric tubes are not required following cystectomy with

2004;91:1138-45. urinary diversion: a comparative analysis of 430 patients. J Urol 2003;170:1888-91.

CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5 347

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 347 9/30/11 4:01 PM

Melnyk et al.

73. Asao T, Kuwano H, Nakamura J, et al. Gum chewing enhances early recovery from postoperative ileus 84. King PM, Blazeby JM, Ewings P, et al. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery

after laparoscopic colectomy. J Am Coll Surg 2002;195:30-2. for colorectal cancer within an enhanced recovery programme. Br J Surg 2006;93:300-8.

74. Quah HM, Samad A, Neathey AJ, et al. Does gum chewing reduce postoperative ileus following open 85. Sammour T, Zargar-Shoshtari K, Bhat A, et al. A programme of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)

colectomy for left-sided colon and rectal cancer? A prospective randomized controlled trial. Colorectal is a cost-effective intervention in elective colonic surgery. N Z Med J 2010;123:61-70.

Dis 2006;8:64-70. 86. Reurings JC, Spanjersberg WR, Oostvogel HJ, et al. A prospective cohort study to investigate cost-minimis-

75. Tandeter H. Hypothesis: hexitols in chewing gum may play a role in reducing postoperative ileus. Med ation, of Traditional open, open fAst track recovery and laParoscopic fASt track multimodal management,

Hypotheses 2009;72:39-40. for surgical patients with colon carcinomas (TAPAS study). BMC Surg 2010;10:18.

76. Schuster R, Grewal N, Greaney GC, et al. Gum chewing reduces ileus after elective open sigmoid colectomy. 87. Gouvas N, Tan E, Windsor A, et al. Fast-track vs standard care in colorectal surgery: a meta-analysis

Arch Surg 2006;141:174-6. update. Int J Colorectal Dis 2009;24:1119-31.

77. Matros E, Rocha F, Zinner M, et al. Does gum chewing ameliorate postoperative ileus? Results of a 88. Polle SW, Wind J, Fuhring JW, et al. Implementation of a fast-track perioperative care program: what are

prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Surg 2006;202:773-8. the difficulties? Dig Surg 2007;24:441-9.

78. Hirayama I, Suzuki M, Ide M, et al. Gum-chewing stimulates bowel motility after surgery for colorectal 89. Maessen J, Dejong CH, Hausel J, et al. A protocol is not enough to implement an enhanced recovery

cancer. Hepatogastroenterology 2006;53:206-8. programme for colorectal resection. Br J Surg 2007;94:224-31.

79. Purkayastha S, Tilney HS, Darzi AW, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized studies evaluating chewing gum 90. Walter CJ, Smith A, Guillou P. Perceptions of the application of fast-track surgical principles by general

to enhance postoperative recovery following colectomy. Arch Surg 2008;143:788-93. surgeons. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2006;88:191-5.

80. Fitzgerald JE, Ahmed I. Systematic review and meta-analysis of chewing-gum therapy in the reduction of 91. Kahokehr A, Sammour T, Zargar-Shoshtari K, et al. Implementation of ERAS and how to overcome the

postoperative paralytic ileus following gastrointestinal surgery. World J Surg 2009;33:2557-66. barriers. Int J Surg 2009;7:16-9.

81. Noble EJ, Harris R, Hosie KB, et al. Gum chewing reduces postoperative ileus? A systematic review and

meta-analysis. Int J Surg 2009;7:100-5. Correspondence: Dr. Anthony Koupparis, Consultant Urological Surgeon, Department of Urological

82. Parnaby CN, MacDonald AJ, Jenkins JT. Sham feed or sham? A meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials Sciences, University of British Columbia, Gordon & Leslie Diamond Health Care Centre, Level 6-2775

assessing the effect of gum chewing on gut function after elective colorectal surgery. Int J Colorectal

Laurel St., Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9; anthonykoupparis@googlemail.com

Dis 2009;24:585-92.

83. Kouba EJ, Wallen EM, Pruthi RS. Gum chewing stimulates bowel motility in patients undergoing radical

cystectomy with urinary diversion. Urology 2007;70:1053-6.

348 CUAJ • October 2011 • Volume 5, Issue 5

CUAJVolume5No4Oct2011.indd 348 9/30/11 4:01 PM

You might also like

- Implementation of A Urogynecology-Specific EnhancedDocument10 pagesImplementation of A Urogynecology-Specific EnhancedangelinputriNo ratings yet

- Vision I 2017Document9 pagesVision I 2017Hamam PrakosaNo ratings yet

- Perioperative Pathways Enhanced Recovery After SurgeryDocument11 pagesPerioperative Pathways Enhanced Recovery After SurgeryRIJANTONo ratings yet

- Scott 2015Document20 pagesScott 2015Raíla SoaresNo ratings yet

- Haywood 2020Document9 pagesHaywood 2020bokobokobokanNo ratings yet

- Protocolo ERAS FebrasgoDocument8 pagesProtocolo ERAS FebrasgoJulianna Vasconcelos GomesNo ratings yet

- ERAS Guidelines PDFDocument8 pagesERAS Guidelines PDFWadezigNo ratings yet

- Acta Anaesthesiol Scand - 2015 - ScottDocument20 pagesActa Anaesthesiol Scand - 2015 - ScottVasile ArianNo ratings yet

- Early Post Op. MobillizationDocument21 pagesEarly Post Op. MobillizationGenyNo ratings yet

- Nauseas y Vomitos ERAsDocument14 pagesNauseas y Vomitos ERAsLiliesther Erminda Hernandez VallecilloNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ajog 2019 06 041Document9 pages10 1016@j Ajog 2019 06 041FebbyNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in Emergency Abdominal Surgery: Background, Preoperative Components of ERAS, Intraoperative Components of ERASDocument9 pagesEnhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) in Emergency Abdominal Surgery: Background, Preoperative Components of ERAS, Intraoperative Components of ERASAndre F SusantioNo ratings yet

- Colo RectalDocument6 pagesColo RectalHilyatul UlaNo ratings yet

- Eras SystectomyDocument9 pagesEras Systectomymehmet kabaaliNo ratings yet

- Guinan 2016Document12 pagesGuinan 2016tusharsinghbainsNo ratings yet

- Diet Modification Based On The ERACSDocument6 pagesDiet Modification Based On The ERACSniken maretasariNo ratings yet

- Emergency LaparotomyDocument13 pagesEmergency LaparotomyDianita P Ñáñez VaronaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Role of Post Operative Physiotherapy in General Surgical Enhanced Recovery After Surgery PathwaysDocument7 pagesWhat Is The Role of Post Operative Physiotherapy in General Surgical Enhanced Recovery After Surgery PathwaysmitchNo ratings yet

- [Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association] Development of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols in veterinary medicine through a one-health approach_ the role of anesthesia and locoregional techniquesDocument9 pages[Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association] Development of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols in veterinary medicine through a one-health approach_ the role of anesthesia and locoregional techniquesFrancisco Laecio Silva de AquinoNo ratings yet

- Protocolo ERASDocument6 pagesProtocolo ERASDEMETRIO MAYORAL PARDONo ratings yet

- Association Between Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Compliance and Clinical ComplicationsDocument11 pagesAssociation Between Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Compliance and Clinical ComplicationsClarissa Simon FactumNo ratings yet

- 17 - Enhanced Recovery PrinciplesDocument7 pages17 - Enhanced Recovery Principlesbocah_britpopNo ratings yet

- Protocolo Eras Jama2017Document7 pagesProtocolo Eras Jama2017caza_nova032282No ratings yet

- 10.1007@s12306 019 00603 4Document6 pages10.1007@s12306 019 00603 4JoseNo ratings yet

- English PB 23Document7 pagesEnglish PB 23shah hassaanNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument14 pages1 PBwanggaNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Association Between Compliance With Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) ProtocolsDocument13 pages2022 - Association Between Compliance With Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) ProtocolsClarissa Simon FactumNo ratings yet

- Essential Elements For Enhanced Recovery After Intra-Abdominal SurgeryDocument4 pagesEssential Elements For Enhanced Recovery After Intra-Abdominal SurgeryJonathan MartinNo ratings yet

- Pre Operativ Dan Post Operative Care in EnglishDocument89 pagesPre Operativ Dan Post Operative Care in Englishamallia yunindyNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1743919113001738Document5 pagesPi Is 1743919113001738Yacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- 4 BaruDocument4 pages4 BaruAnditha Namira RSNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in Paediatrics A Review of LiteraturaDocument7 pagesEnhanced Recovery After Surgery in Paediatrics A Review of LiteraturaFernando LopezNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia For Major Urologic Surgery: James O.B. Cockcroft,, Colin B. Berry,, John S. Mcgrath,, Mark O. DaughertyDocument8 pagesAnesthesia For Major Urologic Surgery: James O.B. Cockcroft,, Colin B. Berry,, John S. Mcgrath,, Mark O. DaughertyJEFFERSON MUÑOZNo ratings yet

- The Impact of A Standardized Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocol in Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Heart Valve SurgeryDocument13 pagesThe Impact of A Standardized Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Protocol in Patients Undergoing Minimally Invasive Heart Valve SurgeryRaj KumerNo ratings yet

- Yeh 2019Document5 pagesYeh 2019sigitdwimulyoNo ratings yet

- 12 BaruDocument8 pages12 BaruAnditha Namira RSNo ratings yet

- Eras GynDocument6 pagesEras GynFirah Triple'sNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery For Cesarean Delivery: Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology February 2020Document9 pagesEnhanced Recovery After Surgery For Cesarean Delivery: Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology February 2020Diana BuleuNo ratings yet

- ErasDocument7 pagesErasQwesxzNo ratings yet

- Orthopedic Principles To Facilitate Enhanced RecovDocument14 pagesOrthopedic Principles To Facilitate Enhanced RecovBader ZawahrehNo ratings yet

- A2 MANEJO DE LIQUIDOS E ILEO POSTOPERATORIODocument7 pagesA2 MANEJO DE LIQUIDOS E ILEO POSTOPERATORIOPablo García HumérezNo ratings yet

- A Prospective Treatment Protocol For Outpatient Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Acute AppendicitisDocument5 pagesA Prospective Treatment Protocol For Outpatient Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Acute AppendicitisBenjamin PaulinNo ratings yet

- Protocol oDocument8 pagesProtocol oCynthia ChávezNo ratings yet

- Adler 2007Document11 pagesAdler 2007Anand KarnawatNo ratings yet

- ESPEN Practical Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryDocument17 pagesESPEN Practical Guideline Clinical Nutrition in SurgeryMaríaJoséVegaNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology: Contents Lists Available atDocument12 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Anaesthesiology: Contents Lists Available atAnil Kumar100% (1)

- Enhanced Recovery After Surgery JournalDocument9 pagesEnhanced Recovery After Surgery JournalDea DickytaNo ratings yet

- Protocol For Acute Complicated and Uncomplicated AppendicitisDocument7 pagesProtocol For Acute Complicated and Uncomplicated AppendicitisMarce SiuNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1743919114008735Document3 pagesPi Is 1743919114008735Firman FajriNo ratings yet

- Development and Implementation of A Comprehensive Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Eras Protocol For Lumbar Spine Fusion The Singapore ExperienceDocument8 pagesDevelopment and Implementation of A Comprehensive Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Eras Protocol For Lumbar Spine Fusion The Singapore ExperienceHerald Scholarly Open AccessNo ratings yet

- Goal-Directed Fluid Therapy Does Not Reduce Primary Postoperative Ileus After Elective Laparoscopic Colorectal SurgeryDocument14 pagesGoal-Directed Fluid Therapy Does Not Reduce Primary Postoperative Ileus After Elective Laparoscopic Colorectal SurgeryNurul Dwi LestariNo ratings yet

- The American Journal of Surgery: Original Research ArticleDocument7 pagesThe American Journal of Surgery: Original Research ArticleManish AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Parrish April 2016Document9 pagesParrish April 2016neiris lopezNo ratings yet

- Bun V34N3p223Document6 pagesBun V34N3p223pingusNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation For Hip Arthros PDFDocument4 pagesRehabilitation For Hip Arthros PDFMónica Sabogal JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Randomized Clinical Trial of Epidural, Spinal or Patient-Controlled Analgesia For Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Colorectal SurgeryDocument11 pagesRandomized Clinical Trial of Epidural, Spinal or Patient-Controlled Analgesia For Patients Undergoing Laparoscopic Colorectal Surgeryvalerio.messinaNo ratings yet

- Meta-Analysis of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)Document13 pagesMeta-Analysis of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS)piceng ismailNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1743919114008735Document3 pagesPi Is 1743919114008735Firman FajriNo ratings yet

- Keys to Successful Orthotopic Bladder SubstitutionFrom EverandKeys to Successful Orthotopic Bladder SubstitutionUrs E. StuderNo ratings yet

- Biliopancreatic Endoscopy: Practical ApplicationFrom EverandBiliopancreatic Endoscopy: Practical ApplicationKwok-Hung LaiNo ratings yet

- Pengadaan BarangDocument17 pagesPengadaan BarangMana AngelNo ratings yet

- List Stok Obat RanapDocument3 pagesList Stok Obat RanapMana AngelNo ratings yet

- Master List Obat Fast MovingDocument4 pagesMaster List Obat Fast MovingMana AngelNo ratings yet

- List Obat Emergency Dan UgdDocument1 pageList Obat Emergency Dan UgdMana AngelNo ratings yet

- List Stok Obat RanapDocument3 pagesList Stok Obat RanapMana AngelNo ratings yet

- Master List Obat Fast MovingDocument3 pagesMaster List Obat Fast MovingMana AngelNo ratings yet

- 3-Drug InteractionsDocument37 pages3-Drug InteractionsMirza Shaharyar BaigNo ratings yet

- Mri Referral Package For Axxess Imaging April 2020Document4 pagesMri Referral Package For Axxess Imaging April 2020JovanyGrezNo ratings yet

- Legal Med FinalDocument59 pagesLegal Med FinalCriminology Criminology CriminologyNo ratings yet

- 001 201373074 CB6 117 1 PDFDocument1 page001 201373074 CB6 117 1 PDFknowledge WorldNo ratings yet

- Module 4 English BookDocument1 pageModule 4 English BookksenijaNo ratings yet

- Brgy. Talandang and Baganihan 2022 ConsolidatedDocument6 pagesBrgy. Talandang and Baganihan 2022 Consolidatedevelyn d. pepitoNo ratings yet

- 2.3 Cohort StudiesDocument6 pages2.3 Cohort StudiesMiguel C. Dolot100% (1)

- 5 Everyday Workplace SafetyDocument11 pages5 Everyday Workplace SafetyBUTCH FAJARDONo ratings yet

- Abnormal NipplesDocument1 pageAbnormal NipplesdrpamiNo ratings yet

- 2023 - UK Guidelines - UK Concussion Guidelines For Grassroots (Non-Elite)Document20 pages2023 - UK Guidelines - UK Concussion Guidelines For Grassroots (Non-Elite)RobinNo ratings yet

- 23 Top Natural Ways To Combat PainDocument23 pages23 Top Natural Ways To Combat PainPaulina DeyanovaNo ratings yet

- TMS ChecklistDocument1 pageTMS ChecklistMuhammad HussnainNo ratings yet

- Vector-Borne Disease PPT FinalDocument17 pagesVector-Borne Disease PPT FinalKenj100% (3)

- HospitalsDocument5 pagesHospitalsDevi RINo ratings yet

- Vicente Et Al., 2024 Perspectivas Da Psicoterapia Na DemênciaDocument12 pagesVicente Et Al., 2024 Perspectivas Da Psicoterapia Na DemêncialalaNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. Annexure Proforma For Registration of Subjects For DissertationDocument6 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. Annexure Proforma For Registration of Subjects For DissertationGirish SubashNo ratings yet

- Hiatal Hernia - JUSTIFICATION OF PRIORITIESDocument1 pageHiatal Hernia - JUSTIFICATION OF PRIORITIESJona Mae Pascual JuanNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Disability/Mental Retardation: Presented By: Miahlee Madrid & Rose Ann PadillaDocument32 pagesIntellectual Disability/Mental Retardation: Presented By: Miahlee Madrid & Rose Ann PadillazsanikaNo ratings yet

- Gingko Biloba and Brain FogDocument4 pagesGingko Biloba and Brain FogAdnanNo ratings yet

- Broselow Color: Grey/Pink: ET Uncuffed Tube Size: 3.5 ET Cuffed Tube Size: 3.0Document6 pagesBroselow Color: Grey/Pink: ET Uncuffed Tube Size: 3.5 ET Cuffed Tube Size: 3.0Dimas Bayu FirdausNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia NotesDocument5 pagesDysphagia Notesapi-31372205650% (2)

- Management of Eyelid Lacerations: CornerDocument6 pagesManagement of Eyelid Lacerations: CornerBrando PanjaitanNo ratings yet

- Fatores Determinantes Da Sarcopenia em Indivíduos Com Doença de Parkinson - LUZ, Marcella Campos Lima, 2020Document7 pagesFatores Determinantes Da Sarcopenia em Indivíduos Com Doença de Parkinson - LUZ, Marcella Campos Lima, 2020Tícia RanessaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Auricular Acupuncture 2nd EditionDocument57 pagesChinese Auricular Acupuncture 2nd Editiongordon.gibson456100% (43)

- 30-8 Final Ann Konker, PIT, Treg CetakDocument4 pages30-8 Final Ann Konker, PIT, Treg CetakHabiby Habibaty Qolbi100% (1)

- TM 2 - Medical Procedure and Equipment (Autosaved)Document30 pagesTM 2 - Medical Procedure and Equipment (Autosaved)누렀나No ratings yet

- 2018 CPC Review AnswersDocument90 pages2018 CPC Review AnswersEsther Rani100% (4)

- Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections, (David Schlossberg (Editor) )Document815 pagesTuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections, (David Schlossberg (Editor) )MAHassanChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- 100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology-532hlm (Warna Hanya Cover)Document11 pages100 Case Studies in Pathophysiology-532hlm (Warna Hanya Cover)Haymanot AnimutNo ratings yet

- 2020 DNB AnesthesiaDocument33 pages2020 DNB AnesthesiasreesaichowdaryNo ratings yet

![[Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association] Development of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols in veterinary medicine through a one-health approach_ the role of anesthesia and locoregional techniques](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/597027379/149x198/4e86c3e723/1710567751?v=1)