Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Relationship Between Visual-Perceptual Motor Abilities and Clumsiness in Children With and Without Learning Disabilities

Uploaded by

LauraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Relationship Between Visual-Perceptual Motor Abilities and Clumsiness in Children With and Without Learning Disabilities

Uploaded by

LauraCopyright:

Available Formats

The Relationship One visual-perceptual test, four l'isual-motor tests,

and a test of motor impairment were administered

to 22 cbildren witb learning disabilities and 22 cbil-

Between Visual- dren witbout learning disabilities, aged 5 to 8

years. Tbe cbildren with learning disabilities were

Perceptual Motor divided into two groups-"clumsy" and "non-

clumsy"-based on tbeir scores on tbe motor im-

Abilities and pairment test It was bypotbesized tbat tbe clumsy

cbildren witb learning disabilities would score sig-

Clllffisiness in Children nificantly lower on visual-perceptual and visual-

motor tests tban tbe non clumsy cbildren witb learn-

With and Without ing disabilities wbo, in turn, would score

Significantly lower tban tbe cbildren witbout learn-

Downloaded from http://research.aota.org/ajot/article-pdf/42/6/359/53515/359.pdf by Integracion Sensorial Acis, Adriana Ramirez on 30 September 2022

ing disabilities. It was furtber bypotbesized tbat

Learning Disabilities there would be a Significant correlation between

tbe degree of clumsiness and tbe degree of visual-

perceptual and visual-motor defiCit. Analysis of the

data indicated that, as expected, the clumsy chil-

Valerie O'Brien, Sharon A. Cermak, dren witb learning disabilities scored significantly

Elizabeth Murray lower tban the children without learning disabilities

(the control group). Tbere was no Significant differ-

ence between the clumsy and nonclumsy children

Key Words: dyspraxia • sensory with learning disabilities or between the nonclumsy

integration. visual perception children with learning disabilities and tbe control

group_ Degree of clumsiness Significantly correlated

with scores on four offive tests Results are discussed

in terms of subtypes of learning disabilities and

sample size.

any occupational therapists treat children

M with learning disabilities for visual-percep-

tual problems, visual-motor problems, and

motor incoordination_ Some researchers suggest that

Visual-perceptual deficits are characteristic of chil-

dren with learning disabilities (Bush & Waugh, 1982)

Others say that children with learning disabilities

have average to superior Visual-perceptual skills

(Geschwind & Galaburda, 1985) Because people

with learning disabilities form a heterogeneous

group, it is probable that there are subgroups of chil-

dren with learning disabilities who do have and who

do not have Visual-perceptual problems Rourke

Valerie O'Brien, MS, OTR, is an occupational therapist at (985) has emphasized that

the Second General Hospital, APO, New York

the confUSIOn that abounds 111 the literature dealing with the

Sharon A. Cermak, EdD, OTR, FAOTA, is Associate Profes- group of clinical problems knOWll as learning disabilities is,

sor of Occupational Therapy at Sargent CoJlege, Bosron in manywa\'s, a direct reflection of the failure of many scien-

University, One University Road, Bosron, Massachuserrs tists and praclitioners in this field to acknowledge and ad-

dress the heterogeneity and diversity extallt among the learn-

02115 ing disabled population. (p vii)

Elizabeth Murray, MEd, OTR, is Assistant Director of

He emphasizes the need to examine subtypes of

Training in Occupational Therapy, Eunice Kennedy

Shriver Center, Waltham, Massachusetts, and Adjunct As- learning disabilities

sistant Professor of Occupational Therapy at Sargent Col- In addition to visual-perceptual problems, non-

lege, Bosron University. specific awkwardness or clumsiness, though not spe-

cific to children with learning disabilities, appears in

Sharon A Cermak and Elizabeth Murray are faculty

greater numbers of these children than in children

members of Sensory Integration International, Torrance,

California without such disabilities Researchers have estimated

that between 5% and 18% of school-age children may

The Americanjournal of Occupational Therapy 359

have motor problems (Brenner, Gilman, Zangwill, & that visual-perceptual problems may be a cause of

Farrell, 1967; Gubbay, 1978; Henderson & Hall, clumsiness.

1982). These children form a heterogeneous group; Ayres (1985) also found that many dyspraxic

all show some degree of inability in their perfor- children had Visual-perceptual problems. However,

mance of skilled or complicated motor tasks. Prob- she theorized that visual perception is an end product

lems in the motor performance of children with learn- and not the basis for the clumsiness. Because factor

ing disabilities have been noted as far back as 1937 analytical studies showed that performance on tactile

when Orton (1937) described abnormal clumsiness tests significantly correlated with motor planning

in many of the children that he studied. Strauss and abilities (Ayres, 1966, 1969), Ayres (1969) suggested

Lehtinen (1947) discussed the incoordination that that tactile perceptual deficits may be a factor in the

frequently occurs in brain-injured children. Re- clumsiness.

searchers in the 1960s began to delineate this clumsi- The present study was designed to further exam-

Downloaded from http://research.aota.org/ajot/article-pdf/42/6/359/53515/359.pdf by Integracion Sensorial Acis, Adriana Ramirez on 30 September 2022

ness, or developmental dyspraxia, evident in many ine the relationship between visual-perceptual and vi-

children with learning disabilities (Gubbay, Ellis, sual-motor deficits and clumsiness in the child with

Walton, & Court, 1965; Kephart, 1960; Walton, Ellis, & learning disabilities. It was hypothesized that clumsy

Court, 1963). children with learning disabilities would score signif-

The terms developmental dyspraXia or clumsy icantly lower on Visual-perceptual and visual-motor

have been used to label children with a motor plan- tests than nonclumsy children with learning disabili-

ning problem. Gubbay (1985) described the clumsy ties, and that nonclumsy children with learning dis-

child as one "whose ability to perform skilled purpo- abilities would score significantly lower than children

sive movement is impaired, yet whose motor coordi- without learning disabilities. It was further hypothe-

nation is Virtually normal by the standards of routine, sized that there would be a significant correlation be-

conventional neurological assessment and who also tween the degree of clumsiness and the degree of

has normal bodily habits, intellect, physical strength Visual-perceptual and visual-motor deficit in the sub-

and sensory function" (p. 159). Ayres (1979) noted jects with learning disabilities.

that the clumsy child seems to have "less of a sense of

his body and what it can do" (p. 101).

Method

Clinical manifestations appear to be varied. Gen-

eral awkwardness, poor tactile perception abilities, Subjects

inadequate body scheme, delayed acqUisition of daily

liVing skills, poor gross and fine motor skills, and Forty-four children participated in the study. Twenty-

articulation deficits are a number of characteristics two had learning disabilities (age range 5 years to 8

frequently attributed to the dyspraxic child (Ayres, years 10 months) and the remaining 22, who had no

1979; Cermak, 1985; Knuckey, Apsimon, & Gubbay, learning disabilities, served as a control group (age

1983). range 5 years 6 months to 8 years 11 months). The

Visual-perceptual and visual-motor deficits have children were matched as closely as possible for age

been described as two of the many performance defi- and sex. Thirty-two of the subjects were male (16 with

cits associated with the clumsy child with learning disabilities, 16 without) and 12 were female (6 with

disabilities. These components are particularly rele- disabilities, 6 without).

vant because some researchers have suggested that The children participating in the study attended

visual-perceptual and visual-motor difficulties under- public and private schools within the Greater Boston

lie the clumsiness seen in some children with learn- area. Each child in the control group was in an age-

ing disabilities (Henderson & Hall, 1982; Hulme, appropriate grade and had no special education re-

Biggerstaff, Moran, & McKinley, 1982). Hulme, Big- quirements and no history of receiving remedial help.

gerstaff, Moran, and McKinley studied 16 clumsy and Each child in the experimental group had a diagnosed

16 normal children in a task of matching the length of learning disability and was receiving special services

lines between and within the modalities of vision and for his or her specific disability. The children with

kinesthesia. These researchers found that the visual learning disabilities (the LD group) were divided into

condition and motor performance correlated highly. two groups-"clumsy" and "nonclumsy"-based on

Although adequate kinesthetic sense was described to their scores on the Test of Motor Impairment (Stott,

be necessary to discriminate body position and am- Moyes, & Henderson, 1984). Of the LD group, 13

plitude of movement, kinesthetic and intersensory were classified as clumsy and 9 as nonclumsy. It

conditions did not correlate with motor ability. In a should be noted that 3 subjects in the control group

follow-up study (Hulme, Smart, & Moran, 1982) re- scored in the mild-clumsy range and the rest scored in

sults continued to reveal increased Visual-perceptual the nonclumsy range. (See Tables 1 and 2 for a de-

deficits in clumsy children. The authors suggested scription of subject groups.)

360 June 1988, Volume 42, Number 6

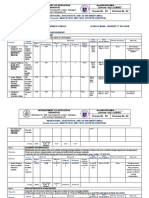

Table 1 year-olds was used. This test was considered a mea-

Description of Subjects sure of visual perception.

Children With Learning 3. Block Design (Wechsler, 1974). This subtest

Disabilities of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, Re-

Control Group

Clumsy NoncJumsy vised, requires reproduction of a presented two-di-

Age n Male Female Male Female Male Female mensional deSign by block manipulation. The test is

5 10 3 2 2 1 1 1 standardized on 6- to 16-year-olds. Scaled scores were

6 11 6 0 3 0 2 0 used, with scores extrapolated for the 5-year-olds.

7 12 3 2 3 1 1 2 4. Primary Visual Motor Test (Haworth, 1970).

8 11 4 2 2 1 2 0

This test consists of 16 designs, shown one at a time,

that the child is reqUired to copy. Suitable for 4- to

8-year-olds, it is used to assess visual-motor develop-

Downloaded from http://research.aota.org/ajot/article-pdf/42/6/359/53515/359.pdf by Integracion Sensorial Acis, Adriana Ramirez on 30 September 2022

Procedure ment and to evaluate deviation in visual motor func-

One visual-perceptual test, four visual-motor tests, tioning. Raw scores, the total number of errors, and

and the Test of Motor Impairment (TMI) were ad- category scores (impaired, or average to above aver-

ministered to each child by the same examiner in a age) were used in data analysis.

session lasting 1!4 to 1 Y2 hours. The children were 5. Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test (Waber &

tested either at their homes or at the Boston Univer- Holmes, 1985). This test, recently described in a for-

sity Occupational Therapy Clinic. mat for children, requires the child to reproduce a

The series of tests, which was administered ac- complex design using five different colored pencils

cording to the directions in the test manual for each in a specified time limit. An organization score based

test, was given in the follOWing order for each child: on the correct features drawn in the design was re-

corded in standard deviation scores.

1. Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integra- 6. Test of Motor Impairment (TMI) (StOtt,

tion, Revised (Beery & Buktenica, 1980). This test Moyes, & Henderson, 1984) This screening test is

contains a series of 24 geometric forms that are to be designed to measure the degree of motOr impairment

copied with pencil in the protocol book. Normed on in children aged 5 years and up. Children are given a

2- to 15-year-olds, it is used to assess visual-motor series of 8 tasks at their age range that evaluate manual

integration. A visual-motor age-equivalent score is dexterity, static balance, dynamic balance, and ball

obtained based on the number of correct forms com- skills. Scores are interpreted as 0 to 3.5-no impair-

pleted up to three consecutive failures. In addition to ment, 4.0 to 55-mild to moderate impairment, and

the age-equivalent score, a visual-motor age differ- above 6.0-definite impairment. For the purposes of

ence score, reported in months, was computed for use this study, 0 to 3.5 was considered normal and scores

in this study by subtracting the child's chronological 4.0 and above were considered impaired, or clumsy.

age from his or her obtained visual-motor age-equiva-

lent score Results

2. Raven ProgreSSive Matrices (Raven, 1960). In order to test the hypothesis that clumsy children

This scale consists of 60 problems divided into five with learning disabilities will score significantly

sets of 12. The problems are meaningless figures that lower on the Visual-perceptual and visual-motor tests

require observation, derivation of relationships be- than nonclumsy children with learning disabilities,

tween the figures, and reasoning to complete each and that nonclumsy children with learning disabilities

figure. The test is suitable for ages 6 years to adult. A will score Significantly lower than children without

percentile score, obtained by extrapolation for the 5- learning disabilities, one·way between-group (clumsy

LD, nonclumsy LD, and control) analyses of variance

(ANOVAs) on each dependent measure were per-

Table 2

Age in Months and TMI Score for Children With and formed. The means and standard deviation for each

Without Learning Disabilities group on each test as well as the F values of the

Children With Learning ANOVAs are presented in Table 3. As noted in this

Disabilities table, there were between-group differences on each

Control

Group Clumsy Nonclumsy of the visual-perceptual and visual-motor tests.

11 22 13 9

Scheffe multiple comparisons were performed to see

Age Mean 8450 8392 85.00 where the differences were. A consistent pattern was

lin months) SD 1485 1228 1387 found, with significant differences on each measure

TMI score Mean 187 796 2.28 between the control group and the clumsy LD group

SD 149 2.23 1.12 but no other significant between-group differences.

Note. TM1 = Test of MotOr Impairment. In order to test the hypothesis that there would

The American Journal oj Occupational Therapy 361

Table 3

Scores on the Visual-Perceptual Motor Tests for Children With and Without Learning Disabilities

Children With Learning

Disabilities

Control ANOVA

Test Group Clumsy Nonclumsy F(2, 41)

Visual Motor Integration

(age equivalent, months) x 97.32 7246 81.56 3.59"

SO 3078 21.96 24.70

Raven Matrices

(percentile score) X 9409 7661 88.11 4.88"

so 11.16 16.75 2376

WISC·R Block Design

(scale score) X 1377 9.00 11.67 7.15""

Downloaded from http://research.aota.org/ajot/article-pdf/42/6/359/53515/359.pdf by Integracion Sensorial Acis, Adriana Ramirez on 30 September 2022

SO 3.25 3.98 394

Primary Visual Motor

(raw error score) X 12.91 2854 1956 10.29" "

SO 839 11.61 10.54

Rey·Osterrieth Complex Figure

(SO score) X 021 -0.86 -0.56 6.57""

SO 1.11 0.34 0.76

"p< .05. "" P < .01.

be a significant correlation between the degree of perceptual and visual-motor tests than nonclumsy

clumsiness and the degree of visual· perceptual and children with learning disabilities and that nonclumsy

visual-motor deficit in children with learning disabili- children with learning disabilities will, in turn, score

ties, a Spearman rank order coefficient of correlation significantly lower than children without learning dis-

was used. Significant correlations (p < .05) were ob- abilities was only partially supported. For all visual-

tained between the TMI score and the Visual-percep- perceptual and visual-motor measures, the children in

tual test (Raven Progressive Matrices) as well as be- the clumsy LD group scored significantly lower than

tween the TMI and two of the three visual-motor tests the children in the control group, but the difference

(see Table 4). A point· biserial correlation was used to between the nonclumsy LD group and the control

examine the correlation between the TMI and the group and between the two LD groups-clumsy and

Primary Visual Motor Test because the scores on the nonclumsy-was not significant.

Primary Visual Motor Test result in placement in ei- One interpretation of the results is that there are

ther the impaired or the average·to·above·average indeed subgroups of learning disabilities, and one

category. A significant correlation, r = -0.44 way of categorizing these subgroups is based on

(t = -(-2.40), P < .05), was found, supporting the motor competence. Mean scores for all tests were best

hypothesis. in the control group and worst in the clumsy LD

group, indicating a trend in scores. It may be that

Discussion there was a difference between the nonclumsy and

the clumsy LD group, but, because of the small sam-

The hypothesis that clumsy children with learning ple size, the difference was not perceptible. The re-

disabilities will score significantly lower on visual- sults do suggest that visual-perceptual abilities are

Table 4

Correlations Between TMI, VMI, Raven, WISC-R Block, and Rey-Osterrieth Tests for Children With Learning Disabilities

(N = 22)

Raven WISe-R Rey·Osterrieth

TMI VMI Matrices Block Design Complex Figure

TMI: No. of errors -400" -,395" -4070 -.225

VMI age difference score" 438" .620"" 426"

Raven Matrices

percentile score 451" -.048

WISe-R Block Design

scale score .328

Rey·Osterrieth Complex

Figure SD score

Note. TMI = Test of Motor Impairment. VMI = Developmental Test of Visual Motor Integration. WISe-R = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for

Children, Revised.

'VMI age difference score obtained by subtracting chronological age from VMI age·equivalent score.

" p < .05. ""p < .01.

362 June 1988, Volume 42, Number 6

clearly not superior in people with learning disabili- Bush, W. J-, & Waugh, K. W. (1982). Diagnosing learn-

ties, as was proposed by Geschwind and Galaburda ing problems. Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill.

Cermak, S. A. (1985). Developmental dyspraxia. In

(1985).

E. A. Roy (Ed.), Neuropsychological studies of apraxia and

Degree of clumsiness did appear, indeed, to be related disorders (pp. 225-243). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

significantly related to the degree of visual-perceptual Geschwind, N., & Galaburda, A. M. (1985). Cerebral

and visual-motor deficit in that the clumsier the child lateralization. Archives ofNeurology, 42, 428-459.

was the greater was the visual-perceptual and visual- Gubbay, S. S. (1978). The management of develop-

mental dyspraxia. Developmental Medicine and Child Neu-

motor problem. Whether the clumsiness is the result

rology, 20, 448-460.

of visual-perceptual and visual-motor deficits, as sug- Gubbay, S. S. (1985). Clumsiness. In P. J Vinken,

gested by some researchers (Henderson & Hall, 1982; G. W. Bruyn, & H. L. Klawans (Eds.), Handbook of clinical

Hulme, Biggerstaff, Moran, & McKinley, 1982; neurology (pp. 159-167). New York: Elsevier.

Hulme, Smart, & Moran, 1982), or whether the visual- Gubbay, S. S., Ellis, T., Walton, J N., & Court, S. D. M.

Downloaded from http://research.aota.org/ajot/article-pdf/42/6/359/53515/359.pdf by Integracion Sensorial Acis, Adriana Ramirez on 30 September 2022

(1965). Clumsy children: A study of apraxia and agnosic

perceptual and visual-motor difficulties and clumsi- deficits in 21 children. Brain, 88,295-312.

ness all are the result of tactile and kinesthetic pro- Haworth, M. (1970) Primary Visual Motor Test New

cessing dysfunction, as noted by Ayres (1966, 1969, York: Grune & Stratton.

1979,1985), remains unclear and will be explored in Henderson, A. E., & Hall, D. (1982). Concomitants of

a future study. Further examination of the relationship clumsiness in young schoolchildren. Developmental Medi-

cine and Child Neurology, 24,461-467.

between these factors is needed because this rela- Hulme, c., Biggerstaff, A., Moran, G., & McKinley, I.

tionship would appear to have implications for the (1982). Visual, kinesthetic and cross-modal judgements of

treatment of the clumsy child with learning disabili- length by normal and clumsy children. Developmental

ties. For example, if the underlying problem involves Medicine and Child Neurology, 24,461-471.

an impairment in tactile and kinesthetic processing, Hulme, c., Smart, S., & Moran, G. (1982) Visual per-

ceptual deficits in clumsy children Neuropsychologia, 4,

then treatment would be aimed at improving sensory 475-481

processing, and procedures such as sensory integra- Kephart, N. (1960). The slow learner in the classroom.

tion would be emphasized. On the other hand, if the Columbus, OH: Charles Merrill.

problem underlying the child's clumsiness is visual- Knuckey, N. W., Apsimon, T. T., & Gubbay, S. S.

perceptual in nature, then remediation might focus (1983) Computerized axial tomography in clumsy children

with developmental apraxia and agnosia. Brain and Devel-

on visual-spatial analysis and/or activities involving opment, 5, 14-20.

the integration of visual and motor components of Orton, S. T. (1937). Reading, writing and speech

performance. As yet, the causative relationship is problems in children. New York: W. W. Norton.

speculative. Raven, J c. (1960). Guide to the Standard Progressive

Matrices. London: H. K. Lewis.

Rourke, B. P. (1985). Neuropsychology of learning dis-

References

abilities: Essentials ofsub-type analysis. New York: Guilford

Ayres, A. ]. (1966) Interrelationships among percep- Press

tual-motor functions in children. American journal of Oc- Stott, D., Moyes, F. A., & Henderson, S. E. (1984). Man-

cupational Therapy, 20, 68-71. ual of Test of Motor Impairment-Henderson Revision.

Ayres, A. J (1969). Deficits in sensory integration in Ontario: Brook Educational.

educationally handicapped children. Journal of Learning Strauss, A. A., & Lehtinen, L. E. (1947). Psychopathol-

Disabilities,2,160-168. ogy and education of the brain-injured child. New York:

Ayres, A.]. (1979). Sensory integration and the child. Grune & Stratton.

Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. Waber, D P., & Holmes,]. M. (1985) Assessing chil-

Ayres, A. ]. (1985). Developmental dyspraXia and dren's copy productions of the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Fig-

adult-onset apraxia. Torrance, CA: Sensory Integration In· ure. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychol-

ternational. ogy, 7, 264-280

Beery, K., & Buktenica, M. (1980). Developmental Test Walton, H. M., Ellis, E, & Court, S. D M. (1963).

of Visual Motor Integration, Revised. Chicago: Follett. Clumsy children: Developmental apraxia and agnosia.

Brenner, M. W., Gilman, S., Zangwill, O. L., & Farrell, Brain, 85, 603-612.

M. (1967). Visuomotor disability in schoolchildren. British Wechsler, D. (1974). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for

Medicaljournal, 4, 259-262. Children-Revised. New York: Psychological Corporation.

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 363

You might also like

- The Sensory Profile A Discrimitant Analysis of Children With and Whithout DisabilitiesDocument8 pagesThe Sensory Profile A Discrimitant Analysis of Children With and Whithout DisabilitiesProfe CatalinaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Residual Vision & Integration - BJVIDocument3 pages2 - Residual Vision & Integration - BJVISanjiv DesaiNo ratings yet

- Optometric Vision TherapyDocument6 pagesOptometric Vision TherapyBlogKing100% (1)

- Discrepancias Entre I Verbal y VisoespacialDocument9 pagesDiscrepancias Entre I Verbal y VisoespacialCarina CamponeroNo ratings yet

- Intelligence Assessments For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesIntelligence Assessments For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewZahra SativaniNo ratings yet

- Memory in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument35 pagesMemory in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Systematic Literature ReviewJenny Mndd GNo ratings yet

- Working Memory Functioning in Children With Learning Disabilities: Does Intelligence Make A Difference?Document8 pagesWorking Memory Functioning in Children With Learning Disabilities: Does Intelligence Make A Difference?Felicia NikeNo ratings yet

- FMskillsDocument14 pagesFMskillsSouban JavedNo ratings yet

- Bart 2011Document8 pagesBart 2011Andrea Gallo de la PazNo ratings yet

- Multiple Disability PresentationDocument22 pagesMultiple Disability PresentationTwefena GilzeneNo ratings yet

- Early Human DevelopmentDocument7 pagesEarly Human DevelopmentAndrés GordilloNo ratings yet

- Self Concept-Visual ImpairmentDocument12 pagesSelf Concept-Visual ImpairmentAlexandra GhiuzanNo ratings yet

- VMIpdfDocument6 pagesVMIpdfRidwan HadiputraNo ratings yet

- Fine Motor Skills in Children With Down Syndrome: January 2014Document14 pagesFine Motor Skills in Children With Down Syndrome: January 2014Lacra ApetreiNo ratings yet

- Emotional Behavioral Disorders in Classroom Handout - DD 002Document6 pagesEmotional Behavioral Disorders in Classroom Handout - DD 002FlemmingNo ratings yet

- Counseling With Exceptional Children PDFDocument12 pagesCounseling With Exceptional Children PDFihsanNo ratings yet

- Adminpujojs,+u +Psycho+12-2+Art +22Document10 pagesAdminpujojs,+u +Psycho+12-2+Art +22Marlon DaviesNo ratings yet

- Low-Dose BDNF and Specific Learning Disabilities A Possible IndicationDocument7 pagesLow-Dose BDNF and Specific Learning Disabilities A Possible IndicationRubén Omar BarraganNo ratings yet

- Thesis Write UpDocument32 pagesThesis Write UpVishwas NayakNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 SoftDocument15 pagesChapter 3 SoftBethanie Mendiola BaseNo ratings yet

- Prof-Ed3-3 MODULE 6 EVALDocument3 pagesProf-Ed3-3 MODULE 6 EVALDesame Bohol Miasco SanielNo ratings yet

- Mcdermott Disabilitypaper 2Document11 pagesMcdermott Disabilitypaper 2api-537421804No ratings yet

- Stadskleiv 2020Document7 pagesStadskleiv 2020Jonathan Billy ChristianNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Visual-Motor Perception and Cognitive Abilities of Children With Learning DisordersDocument6 pagesRelationship Between Visual-Motor Perception and Cognitive Abilities of Children With Learning DisordersGustavo Calderón-De la CruzNo ratings yet

- Develop Med Child Neuro - 2020 - Stadskleiv - Cognitive Functioning in Children With Cerebral PalsyDocument7 pagesDevelop Med Child Neuro - 2020 - Stadskleiv - Cognitive Functioning in Children With Cerebral PalsyRenata ToscanoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Clusters in SpecificDocument11 pagesCognitive Clusters in SpecificKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Visual-Motor Perception of Students With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity DisorderDocument6 pagesVisual-Motor Perception of Students With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorderkathy cantNo ratings yet

- Educational Strategies Newsletter April 2010Document1 pageEducational Strategies Newsletter April 2010Catherine StreckerNo ratings yet

- Gray Matter, Matters: Reflections on Child Brain Injury and Erroneous Educational PracticesFrom EverandGray Matter, Matters: Reflections on Child Brain Injury and Erroneous Educational PracticesNo ratings yet

- Research in Developmental Disabilities: Brigitte Vugs, Marc Hendriks, Juliane Cuperus, Ludo VerhoevenDocument13 pagesResearch in Developmental Disabilities: Brigitte Vugs, Marc Hendriks, Juliane Cuperus, Ludo VerhoevenPaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- De Clercq-Quaegebeur, 2017 Arithmetic Abilities in Children With DyslexiaDocument14 pagesDe Clercq-Quaegebeur, 2017 Arithmetic Abilities in Children With DyslexiaJorgeVictorMauriceLiraNo ratings yet

- School Children TestsDocument10 pagesSchool Children TestsMamiko Fenella SyNo ratings yet

- Najmd V1 1009Document4 pagesNajmd V1 1009merliaNo ratings yet

- The Sensory ProfileDocument8 pagesThe Sensory ProfileMirela LungNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 15 737409 2Document17 pagesFnhum 15 737409 2sciencegirls314No ratings yet

- SENSORY HANDICAP - Emotional and Behavioral Assessment of Youths With Visual Impairments Utilizing The BASCDocument3 pagesSENSORY HANDICAP - Emotional and Behavioral Assessment of Youths With Visual Impairments Utilizing The BASCJeric C. ManaliliNo ratings yet

- Reading Ability of Children Treated For AmblyopiaDocument11 pagesReading Ability of Children Treated For AmblyopiaRishabh DevNo ratings yet

- TEST PROPOSAL FinalDocument5 pagesTEST PROPOSAL Finaljomelleann.pasolNo ratings yet

- Pep RDocument12 pagesPep Rnays meetNo ratings yet

- 2 Cerebral Visual Impairment-Related Vision ProblemsDocument7 pages2 Cerebral Visual Impairment-Related Vision ProblemsMonica Laura SanchezNo ratings yet

- Autismo WiscDocument10 pagesAutismo WiscCamping Las CorrientesNo ratings yet

- Actual Motor Performance and Self-Perceived Motor Competence in Children With Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Compared With Healthy Siblings and PeersDocument6 pagesActual Motor Performance and Self-Perceived Motor Competence in Children With Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Compared With Healthy Siblings and PeersBrigita RenataNo ratings yet

- L7 Learners With Difficulty With Self Care G6 PDFDocument45 pagesL7 Learners With Difficulty With Self Care G6 PDFJefrelyn Eugenio MontibonNo ratings yet

- Differences in The Intellectual Profile of Children With Intellectual vs. Learning DisabilityDocument7 pagesDifferences in The Intellectual Profile of Children With Intellectual vs. Learning DisabilityKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- A Neuropsychological Profile of DDDocument14 pagesA Neuropsychological Profile of DDDanilkaNo ratings yet

- CH5 - Middle and Late Childhood - de Guzman - Grengia - Ines - Villanueva - YganaDocument6 pagesCH5 - Middle and Late Childhood - de Guzman - Grengia - Ines - Villanueva - YganaAlexandra Nicole EnriquezNo ratings yet

- The Efficacy of Computer Assisted Cognitive Training in The Remediation of Specific Learning DisordersDocument4 pagesThe Efficacy of Computer Assisted Cognitive Training in The Remediation of Specific Learning DisordersRakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- A Study of Ocular Abnormalities in Children With Cerebral PalsyDocument6 pagesA Study of Ocular Abnormalities in Children With Cerebral PalsySuvratNo ratings yet

- Dyspraxia in Autism Association With Motor Social and Communicative DeficitsDocument6 pagesDyspraxia in Autism Association With Motor Social and Communicative Deficits賴莙儒No ratings yet

- Intelectual DisabilitiesDocument13 pagesIntelectual DisabilitiesNadia Desanti Rachmatika100% (1)

- Early Motor Development of Blind Childre PDFDocument4 pagesEarly Motor Development of Blind Childre PDFAndrea MenesesNo ratings yet

- 99-Article Text-215-1-10-20190104Document13 pages99-Article Text-215-1-10-20190104Joi JenozNo ratings yet

- Low Vision Aids: Visual Outcomes and Barriers in Children With Low VisionDocument4 pagesLow Vision Aids: Visual Outcomes and Barriers in Children With Low VisionshishichanNo ratings yet

- BarrierstoPAforchildrenwithVI PalaestraDocument7 pagesBarrierstoPAforchildrenwithVI PalaestraPrincess PacpacNo ratings yet

- Comparing Motor Performance, Praxis, Coordination, and Interpersonal Synchrony Between Children With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)Document17 pagesComparing Motor Performance, Praxis, Coordination, and Interpersonal Synchrony Between Children With and Without Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)oetari putriNo ratings yet

- Bishop - Dore Programme Miracle or MythDocument4 pagesBishop - Dore Programme Miracle or MythLindy PangNo ratings yet

- Learning Disability and Behaviour Problems Among School Going ChildrenDocument6 pagesLearning Disability and Behaviour Problems Among School Going ChildrenDishuNo ratings yet

- What Categories of Special Children Are Entitled To Special Education Under IDEA?Document15 pagesWhat Categories of Special Children Are Entitled To Special Education Under IDEA?Edrian EleccionNo ratings yet

- Bucaille 2021Document17 pagesBucaille 2021DarkCityNo ratings yet

- Bailey AssessmentDocument5 pagesBailey AssessmentAnh BuiNo ratings yet

- Developmental Dyspraxia and The Play Skills of Children With AutismDocument6 pagesDevelopmental Dyspraxia and The Play Skills of Children With AutismLauraNo ratings yet

- Sensory Profile ToddlerDocument5 pagesSensory Profile ToddlerLauraNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of MealSense A Sensory Integration-Based Feeding Support Program For ParentsDocument7 pagesEvaluation of MealSense A Sensory Integration-Based Feeding Support Program For ParentsLauraNo ratings yet

- Prewriting SkillsDocument10 pagesPrewriting SkillsLauraNo ratings yet

- Organizing Alerting Calming Activities For Kids FINALDocument5 pagesOrganizing Alerting Calming Activities For Kids FINALLauraNo ratings yet

- Identifying Aspiration Among Infants in Neonatal Intensive Care Units Through Occupational Therapy Feeding EvaluationsDocument9 pagesIdentifying Aspiration Among Infants in Neonatal Intensive Care Units Through Occupational Therapy Feeding EvaluationsLauraNo ratings yet

- FineMotorChallenge MinutetoWinIt Activities PacketDocument11 pagesFineMotorChallenge MinutetoWinIt Activities PacketLauraNo ratings yet

- May-Benson CermakDocument7 pagesMay-Benson CermakLauraNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Outpatient OT Interventions To Improve Motor Skills For Children With SomatodyspraxiaDocument1 pageEffectiveness of Outpatient OT Interventions To Improve Motor Skills For Children With SomatodyspraxiaLauraNo ratings yet

- A Call To Reexamine Quality of Life Through Relationship-Based FeedingDocument7 pagesA Call To Reexamine Quality of Life Through Relationship-Based FeedingLauraNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Narrative Language Skills and Ideational Praxis in ChildrenDocument3 pagesThe Relationship Between Narrative Language Skills and Ideational Praxis in ChildrenLauraNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study To Measure Deficits in Proprioception in Children With SomatodyspraxiaDocument10 pagesPilot Study To Measure Deficits in Proprioception in Children With SomatodyspraxiaLauraNo ratings yet

- Differentiation of Praxis Among ChildrenDocument8 pagesDifferentiation of Praxis Among ChildrenLauraNo ratings yet

- EASI Praxis Tests Age Trends and Internal ConsistencyDocument7 pagesEASI Praxis Tests Age Trends and Internal ConsistencyLauraNo ratings yet

- Sensory Integration and Praxis Patterns in Children With AutismDocument8 pagesSensory Integration and Praxis Patterns in Children With AutismLauraNo ratings yet

- Effect of Classroom Modification On Attention and Engagement of Students With Autism or DyspraxiaDocument9 pagesEffect of Classroom Modification On Attention and Engagement of Students With Autism or DyspraxiaLauraNo ratings yet

- Deficits in Proprioception Measured in Children With SomatodyspraxiaDocument2 pagesDeficits in Proprioception Measured in Children With SomatodyspraxiaLauraNo ratings yet

- Presentation SG9b The Concept of Number - Operations On Whole NumberDocument30 pagesPresentation SG9b The Concept of Number - Operations On Whole NumberFaithNo ratings yet

- What Is A Spiral Curriculum?: R.M. Harden & N. StamperDocument3 pagesWhat Is A Spiral Curriculum?: R.M. Harden & N. StamperShaheed Dental2No ratings yet

- POC Mobile App Scoping Documentv0.1Document24 pagesPOC Mobile App Scoping Documentv0.1Rajwinder KaurNo ratings yet

- Makalah Bahasa InggrisDocument2 pagesMakalah Bahasa InggrisDinie AliefyantiNo ratings yet

- Wolof Bu Waxtaan Introductory Conversational WolofDocument15 pagesWolof Bu Waxtaan Introductory Conversational WolofAlison_VicarNo ratings yet

- Short Note:-: Neelanjan Ray 1305017048 Health Care Managemnet BBA (H) - 6 SEM BBA - 604Document8 pagesShort Note:-: Neelanjan Ray 1305017048 Health Care Managemnet BBA (H) - 6 SEM BBA - 604neelanjan royNo ratings yet

- A Description of A CelebrationDocument3 pagesA Description of A CelebrationzhannaNo ratings yet

- Arturo Leon CV May 20 2014Document27 pagesArturo Leon CV May 20 2014Guillermo Yucra Santa CruzNo ratings yet

- General Education From PRCDocument40 pagesGeneral Education From PRCMarife Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- References - International Student StudiesDocument5 pagesReferences - International Student StudiesSTAR ScholarsNo ratings yet

- Thinking and Working Scientifically in Early Years: Assignment 1, EDUC 9127Document10 pagesThinking and Working Scientifically in Early Years: Assignment 1, EDUC 9127MANDEEP KAURNo ratings yet

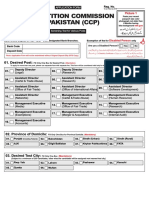

- Competition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NDocument4 pagesCompetition Commission of Pakistan (CCP) : S T NS T NMuhammad TuriNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Synthesis TemplateDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Synthesis Templateea84e0rr100% (1)

- Matalino St. DM, Government Center, Maimpis City of San Fernando (P)Document8 pagesMatalino St. DM, Government Center, Maimpis City of San Fernando (P)Kim Sang AhNo ratings yet

- ICEUBI2019-BookofAbstracts FinalDocument203 pagesICEUBI2019-BookofAbstracts FinalZe OmNo ratings yet

- Learning and Cognition EssayDocument6 pagesLearning and Cognition Essayapi-427349170No ratings yet

- Scholarship Application Form: TBS - Scholarships@tcd - IeDocument2 pagesScholarship Application Form: TBS - Scholarships@tcd - IeRoney GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Laser Coaching: A Condensed 360 Coaching Experience To Increase Your Leaders' Confidence and ImpactDocument3 pagesLaser Coaching: A Condensed 360 Coaching Experience To Increase Your Leaders' Confidence and ImpactPrune NivabeNo ratings yet

- Teaching Physical Education Lesson 1Document2 pagesTeaching Physical Education Lesson 1RonethMontajesTavera100% (1)

- MTB Mle Week 1 Day3Document4 pagesMTB Mle Week 1 Day3Annie Rose Bondad MendozaNo ratings yet

- Daniel B. Pe A Memorial College Foundation, Inc. Tabaco CityDocument3 pagesDaniel B. Pe A Memorial College Foundation, Inc. Tabaco CityAngelica CaldeoNo ratings yet

- Quality Assurance in BacteriologyDocument28 pagesQuality Assurance in BacteriologyAuguz Francis Acena50% (2)

- Bangor University - EnglandDocument11 pagesBangor University - Englandmartinscribd7No ratings yet

- COT1 Literal and Figurative 2nd QDocument3 pagesCOT1 Literal and Figurative 2nd QJoscelle Joyce RiveraNo ratings yet

- Davison 2012Document14 pagesDavison 2012Angie Marcela Marulanda MenesesNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics IXDocument7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan in Mathematics IXJen Paez100% (1)

- Little Science Big Science and BeyondDocument336 pagesLittle Science Big Science and Beyondadmin100% (1)

- Edsp - Lesson Plan - Underhand ThrowingDocument7 pagesEdsp - Lesson Plan - Underhand Throwingapi-535394816No ratings yet

- Pestle of South AfricaDocument8 pagesPestle of South AfricaSanket Borhade100% (1)

- Q3 WEEK 1 and 2 (MARCH 1-12. 2021) Grade 2Document10 pagesQ3 WEEK 1 and 2 (MARCH 1-12. 2021) Grade 2Michelle EsplanaNo ratings yet