Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brittlebank - Sakti and Barakat - The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of The Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysore

Uploaded by

Bidisha SenGuptaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brittlebank - Sakti and Barakat - The Power of Tipu's Tiger. An Examination of The Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of Mysore

Uploaded by

Bidisha SenGuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

Sakti and Barakat: The Power of Tipu's Tiger.

An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of

Tipu Sultan of Mysore

Author(s): Kate Brittlebank

Source: Modern Asian Studies , May, 1995, Vol. 29, No. 2 (May, 1995), pp. 257-269

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/312813

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Modern Asian Studies

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Asian Studies 29, 2 (1995), pp. 257-269. Printed in Great Britain

Sakti

Sakti and

andBarakat:

Barakat:The

The

Power

Power

of Tipu's

of Tipu's

Tiger

An Examination of the Tiger Emblem of Tipu Sultan of

Mysore

KATE BRITTLEBANK

Monash University

A figure who walks larger than life through the p

century south-Indian history is Tipu Sultan Fath

power in Mysore from 1782 until his death at the

in 1799. In general, scholars of his reign have ta

centric approach, essentially concentrating on h

ships and activities, particularly with regard to

British,' while more recently there has been som

economy and administration.2 Recent research into

religion in south India raises issues which sugges

ruler was reassessed in his own terms, from the po

cultural environment in which he was operating.3

has been made to do this.4 One matter which meri

is his use of symbols, particularly in connection

expression of kingship. Given Tipu's somewhat a

a parvenu, whose legitimacy as ruler was quest

I am grateful to Dr Ian Mabbett for his critical comment

i See, for example, Mohibbul Hasan, History of Tipu Sul

1971); B. Sheik Ali, A Study of Diplomacy and Confrontation

2 For example, Nikhiles Guha, Pre-British State System in S

i799 (Calcutta, 1985); Asok Sen, 'A Pre-British Economic Fo

Late Eighteenth Century: Tipu Sultan's Mysore', Barun De (e

Sciences I (Calcutta, I977), pp. 46-I 19; Burton Stein, 'State

Reconsidered: Part One', Modern Asian Studies I9, 3 (I985)

3 See, for example, Arjun Appadurai, Worship and Conflict

South Indian Case (Cambridge, i98I); Susan Bayly, Saints, Godd

and Christians in South Indian Society I7oo-90oo (Cambridge

The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom (Cambr

has been Burton Stein's Peasant State and Society in Medieval

4 While Hasan addresses the question of religion, for exam

a minor way. Stein's article is really the only work which

within his cultural context.

oo26-749X/95/$5.oo+.oo ? 1995 Cambridge University Press

257

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

258 KATE BRITTLEBANK

appear to be a fruitful area for research.5

was the tiger, yet while it has captured t

in other disciplines,6 it has not exercised

any extent.7 It is the aim of this paper t

looking at this symbol in the light of the

has underlined the strongly syncretic natur

Drawing upon both written and oral mat

the interaction which has taken place be

Christian traditions, the result of which

and ideas, a frequently shared vocabulary

motifs within a common sacred landscape

the imagery associated with the ammans o

It is my contention that an examination o

reveal that it is firmly rooted in this syncr

and that this should emphasize to us the

Mysore ruler within his cultural context

actions, particularly from the point of view

Tipu's adoption of the tiger as an emble

naturalistic representation of the tiger (ofte

tion and the tiger stripe motif alone. The la

to as babri, from babr, meaning tiger, altho

appears more properly to refer to the

appeared.9 His use of this emblem seems

upon the obsessive.10 In one or other for

his arms, both large and small, on the unifo

coins, as wall decoration, on his flags a

3 Tipu's status in relation to the Wodeyar Kart

complex matter and one which will be addressed e

6 See, for example, Mildred Archer, Tippoo's Tig

et al., Tigers round the Throne: The Court of Tipu Su

7 Hasan, for example, pays it no attention.

8 Susan Bayly, Saints; also 'Hindu Kingship and th

gion. State and Society in Kerala, I750-1850', Mod

pp. 177-213; 'Islam in Southern India: "Purist" or

D. H. A. Kolff (eds), Two Colonial Empires: Comparati

and Indonesia in the Nineteenth Century (Dordrecht, 1

9 William Kirkpatrick, Select Letters of Tippoo Sulta

(London, I8i I), Letter CCCLIII. The term is used

10 This type of 'obsession' is not without precede

II of Bijapur displayed a similar attachment to th

Ghauri, 'Kingship in the Sultanates of Bijapur an

(1972), pp. 43, 46. It should be noted that the tiger

by Tipu. A sun motif, a not uncommon Indian roy

of the name of his father, Haidar Ali, are also frequ

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE POWER OF TIPU S TIGER 259

spectacular

spectacular example,

example,

on his throne,

on his whichthrone,

displayed a whi

mass

tiger

tiger headhead

with crystal

with teeth."

crystalThe stripe

teeth."was stamped

The strip on th

ings

ings of of

his books

his books

and servedand

as theserved

watermark

as the

on hiswate

paper

is

isdescribed

described leavingleaving

the palace the

'. . . in

palace

a dress and

'. . accoutr

. in

adorned

adorned withwith

the tyger's

thehead"3

tyger's

and the head"3

main entrance

and the to hism

area

areaat at

Seringapatam

Seringapatam

was guardedwas by four

guarded

tigers chained

by fo w

passage.'4

passage.'4 A particularly

A particularly

well-known well-known

artefact from his arte

reign

mechanical

mechanical man-eating

man-eating

tiger, now in tiger,

the collection

now in of the

thV

and

and Albert

AlbertMuseumMuseum

in London.15

in However,

London.15 the mostHoweve

evocati

resentation,

resentation, I believe,

I believe,

and the oneand

of most

the significance

one of formost

this

is

istoto

be be

found

found

on a green

on silk

a green

banner which

silk is

banner

still extant.

wh It

aacalligraphic

calligraphicdesign design

of a tiger'sof

mask

a tiger's

(see Fig. I),mask

the w

which

which readread

'The Lion

'Theof God

Lion is Conqueror'

of God or, is alternatively

Conquero

Victorious

Victorious Lion of

Lion

God'. of

'LionGod'.

of God''Lion

(Asad Allah)

of God'

is an epit

(A

Ali,

Ali, one

one

of the

offirst

the four

first

Caliphs

four

of Islam

Caliphs

and believed

of Islam

by th

to be the true successor to Muhammad.16

Tipu's use of the tiger motif is not as original as some have

thought.'7 Within India itself tigers are clearly associated with roy-

alty. Two contemporary writers refer to the 'royal tiger18 and a tiger

skin seat is found among the royal regalia of Shivaji.'9 Tigers are also

1 A large number of illustrations of the different uses made of the tiger motif can

be found in Buddle, Tigers. See also Denys Forrest, Tiger of Mysore: The Life and Death

of Tipu Sultan (London, 1970) and J. R. Henderson, The Coins of Haidar Ali and Tipu

Sultan (Madras, 192i). Henderson fails to identify the babri stripe, which he merely

refers to as an 'obliquely twisted pointed oval', but it is clear from illustrations that

this is in fact what it is, p. 31.

12 Kirkpatrick, Letters, p. 395.

13 Munshi M. Qasim, 'An Account of Tipu Sultan's Court', India Office Library,

MS Eur.C.io.

14 Francis Buchanan, Journey from Madras through the Countries of Mysore, Can

Malabar, 3 vols (London, 1807), I, p. 72.

15 For a description of this gruesome machine, see Archer, Tiger.

16 A photograph of the banner can be found in Buddle, Tigers, p. 18. Kirk

states that this image appeared on most of Tipu's arms. Letters, p. 155

Victoria and Albert Museum, The Indian Heritage: Court Life and Arts unde

Rule (London, 1982), p. 139.

17 Buddle, Tigers, p. i8; Kirkpatrick, Letters, p. 138, n. I.

18 Alexander Beatson, A View of the Origin and Conduct of the War with Tippo

Comprising a Narrative of the Operations of the Army under the Command of Lieutenan

Harris, and of the Siege of Seringapatam (London, 800o), p. 154; MMDLT, H

and Revolution in India (The History of Hyder Shah Alias Hyder Ali Khan Bahad

published 1784 (Delhi, 1988), p. 28.

19 Michael H. Fisher, A Clash of Cultures: Awadh, The British, and the

(Riverdale, 1987), p. 158. See also Ronald Inden, 'Ritual, Authority, and

Time in Hindu Kingship', J. F. Richards (ed.), Kingship and Authority in Sou

2nd edn (Madison, I98i), pp. 45, 53. It is interesting to note that in Tib

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

260 KATE BRITTLEBANK

revered

revered in various parts

in ofvarious

India, most notably

partsBengal andofRajasthan

India, most n

asas

well well

as the Deccan.20

as the This appears

Deccan.20

to have led to the This

use of the appears to

tiger

tiger

as a symbol

as both

a on symbol

arms and standards.21

both The onmotif, arms

more and sta

particularly

particularlythe stripe, is alsothe

found within

stripe,the Islamicisworld.

also

The found w

Ottoman

Ottoman rulers were especially

rulers fond were

of this design

especially

(although it was fond of

not

notidentical

identical

to Tipu's stripe), which

to Tipu's

they used on textiles,

stripe), for which

example,

example, and which wasandoften accompanied

whichby was three dots,

often

thought accompa

toto

represent

represent

leopard spots.22 Sulayman

leopard the Magnificent

spots.22 used the Sulayman

stripe

stripeto decorate

tothe decorate

seat of his campaignthe

throne.23 seat

Althoughof the his campa

Mughal

Mughal emperors are

emperors

known to have copied

arethis pattern,

known they do not

to have cop

appear

appearto have used

to it extensively.24

have used Even so, it

it is very

extensively.24

possible that Eve

Tipu

Tipuwas familiar

was withfamiliar

this motif since the

with

influence this

of Ottoman motif sinc

designs

designs

and fabricsand

had beenfabrics

particularly strong

hadin thebeen

Deccani states,

particularly s

asas

opposed

opposed

to the north.25to

That the

there is anorth.25

connection is also suggested

That there is a

bybythe dictionary

the dictionary

definition of babri bayan:

definition

'A kind of military cloak

of babri baya

made

made of a leopard's

of skin a leopard's

(such as worn by Rustam)';

skin among(such

its other as worn b

definitions

definitions is: 'a linen garment

is:worn'a bylinen

kings in battle

garment

and held worn b

ominous'.26

ominous'.26 It does seem, therefore,

It does that although

seem, the pattern

therefore,

may tha

have

havebeen original,

been this type

original,

of decoration was

thisnot an invention

typeofof decorat

the

theruler of

ruler

Mysore. of Mysore.

Furthermore,

Furthermore, in the past the tiger

in as anthe

emblempast

or crest had

thenot tiger as a

been

beenunknown unknown

in the region under in

Tipu'sthe

sway. Each

region

ruling dynasty

under Tipu

inin

this this

area had itsarea

own insignia

had whichits

playedown

an important

insignia

role in which

the

the

symbolism

symbolism

of kingship. It appeared

ofonkingship.

royal seals, copper-plate

It appeared

inscriptions,

inscriptions,

lithic records andlithic

flags, and when

records

a ruler was conquered

and flags, and

by

byanother,

another,

the victor adopted

thethe insignia

victorof the vanquished.27

adopted Mais- the insigni

skins

skins were symbolic

were of '... symbolic

wealth, power, authority,

of status'... and

wealth,

guardianship.' power, auth

Daniel

Daniel Shaffer, 'In

Shaffer,

the Forests of the'InNight',

the Hali 41 Forests

(Sept-Oct 1988), pp.of 44-5.the Night', Ha

2020 Asutosh

Asutosh

Bhattacharyya, Bhattacharyya,

'The Tiger-Cult and its Literature in'The Lower Bengal',

Tiger-Cult and

Man

Man in Indiain27 (1947),

Indiapp. 44-5.27 (1947), pp. 44-5.

21

21 Examples

Examples

can be found in Sadashiv

can Gorakshkar

be found (ed.), Animal

inin Sadashiv

Indian Art Goraksh

(Bombay,

(Bombay, 1979), p. 31; Victoria

1979), and Albert

p. Museum,

31; Victoria

Heritage, p. I57. and Albert Muse

2222 Arts Arts

Council of Great

CouncilBritain, Theof

Arts ofGreat

Islam (London,Britain,

1976), p. 82. Colour

The Arts of I

photographs

photographs can be found in Donald

canKing, be 'Treasures

found of the Topkapi

in DonaldSaray', Hali King, 'Tre

3434(April-June

(April-June

I987), pp. 28, 3I. I amI987),

grateful to Susan

pp.Scollay28, for3I.

discussing

I am with grateful to

me

me the Ottomans'

the Ottomans'

use of the stripe. use of the stripe.

2323 Viewed

Viewed

by the author.by the author.

2424 Victoria

Victoria

and Albert Museum,

and Heritage,

Albert pp. 98-9. AMuseum,

Mughal girdle with this

Heritage, pp. 9

design

design is illustrated

is inillustrated

Leigh Ashton, The Art of in India

Leigh

and PakistanAshton,

(London, I950), The Art of

P1. 76.

25 Victoria and Albert Museum, Heritage, pp. 25, 92. Curiously enough, an ident-

ical stripe to Tipu's can be found on a Syrian 8th-century stone carving of a tiger.

Illustrated in Claude Humbert, Islamic Ornamental Design (London, I980), P1. 995.

26 F. Steingass, A Comprehensive Persian-English Dictionary (New Delhi, 1981).

27 T. V. Mahalingam, South Indian Polity, 2nd edn (Madras, 1967), p. 87.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE POWER OF TIPU'S TIGER 26I

tre

tre de de

la Tour

la Tour

refers torefers

this practice

to when

thisdescribing

practice the when

magnificent

describi

state

state procession

procession

of HaidarofAli, Haidar

in which these

Ali,'marks

in which

of honour'these

were 'ma

carried.28 The choice of emblem seems often to have been related to

the religious affiliation of the holder. For example, the Wodeyars of

Mysore, who were Vaishnavas, had among their insignia the boar,

the discus (Chakra) and the garuda, all of which are associated with

Vishnu.29 As for the tiger as an emblem, this was adopted by the

Colas, who were Saivites, who used it on their crests and banners, as

did the Hoysalas of Dvarasamudra.30 That there is an association of

the tiger with rulers of Mysore is also suggested by the fact that the

old city (later destroyed by Tipu) is described in the early eighteenth

century as having 'tiger-faced' gates.31 The Wodeyars, however, do

not appear to have used it as an emblem, which may have been

significant from Tipu's point of view, since, no doubt, he would have

wished to distance himself from the previous ruling dynasty. This

seems to be confirmed by the design on the heel plate of one of his

sporting guns, in which two tigers are depicted killing the double-

headed eagle, or ghandabherunda, an emblem of the deposed royal

line.32 From his gift of a piece of babri cloth to one of his commanders,

to be used in an article of clothing,33 one can infer that he was operat-

ing within the same cultural meaning of the symbol. As an incorporat-

ive mechanism, emblems were made as gifts by south Indian rulers

to their inferiors.34

Let us now turn to the central issue of this paper: why should Tipu

have chosen the tiger and not some other feature as his main emblem?

Why not choose something more overtly Islamic? He does not appear

to have inherited it from Haidar, whose uniform, for example, is

described as being mainly yellow with gold flowers.35 It has been

claimed that Tipu means tiger in Kanarese but this is not the case.36

28 MMDLT, Haidar, p. I80.

29 Mahalingam, Polity, pp. 87-90. C. Hayavadana Rao, History of Mysore (i399-

'799 A.D.), 3 vols (Bangalore, 1943-46), I, pp. 66, 95, 507.

30 Mahalingam, Polity, pp. 90-2. The Hoysalas had a close affiliation withJainism.

31 Rao, History, I, p. 389.

32 Victoria and Albert Museum, Heritage, p. I39.

33 Kirkpatrick, Letters, CCCLIII.

34 Dirks, Hollow Crown, p. 47. On incorporation see also Bernard S. Cohn, 'Repres-

enting Authority in Victorian India', An Anthropologist among the Historians and Other

Essays (Delhi, I987), pp. 635-7, 641: M. N. Pearson (ed.), Legitimacy and Symbols: The

South Asian Writings of F. W. Buckler (Ann Arbor, 1985), pp. 177-8.

33 MMDLT, Haidar, p. 23. Haidar seems to have particularly favoured the use of

yellow, a colour '. . . much affected by the emperor and the Subas'. Ibid., p. I80.

36 Archer, Tiger, p. 4. Rao, History, III, p. 914. Rao, however, later contradicts

himself. III, p. 1030.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

262 KATE BRITTLEBANK

This

This misconception

misconceptioncould possibly have

could arisenpossibly

from the fact have

that the a

British

British called the

called

Mysorethe ruler 'the

Mysore

Tiger of Mysore',

ruleralthough

'the ITiger have

found

found no evidence

no evidence

to suggest thatto Tipusuggest

referred to himself

that in Tipu

that

way.

way. BritishBritish

writers ofwriters

the time believed

of thethe answer

time lay both

believed

in Tipu's t

reverence

reverence for Ali, for

who weAli,have seen

who is referred

we have to as theseen

Lion ofis God,ref

and

and in theincoincidence

the coincidence

of Haidar, the name ofofHaidar,

his father, also

the meaning

name

'lion'

'lion' and also

and being

also

a title

being

of Ali.37 a

Thetitle

basis forof this

Ali.37

argumentThe is thatba

at

at thethelinguistic

linguistic

level in India level

there is no

indistinction

India made there between

is the

no d

lion

lion and and

the tiger,

the the tiger,

words usedthe for eachwords

being interchangeable.38

used for ea

Thus,

Thus, to Tipu,

toAsadTipu,Allah could

Asad haveAllah

meant 'Tigercouldof God'.39

have Thisme is

an

an important

important point and one point

which is andvital to

one our understanding

which is of vi

Tipu's

Tipu's choice.choice.

It is my view It that

is the

my earlyview

writersthat

were onthethe right

earl

track

track and that

and thisthat

is supported

this byisthesupported

calligraphic designby of the

the tigercal

mask

mask referred

referred

to above. It to

is this

above.

design which

It Iis believe

this is the

design

key to

the issue.

Before proceeding further, we need to examine the reasons for the

Mysore ruler's quite obvious reverence for Ali, for here there lies

another clue. First and foremost, Tipu was a warrior; as a successor to

Vijayanagara traditions, the society in which he moved was a warrior

society.40 Such was his son's zeal as a youth, Haidar feared for his

safety.41 That he should have chosen Ali as '. .. the guardian genius, or

tutelary saint, of his dominions; as the object of his veneration, and as

an example to imitate'42 is not surprising. As well as being revered by

the Shi'as, Ali is honoured by Muslims as a great warrior, with all

Sunnis invoking his name in battle.43 The words 'God' and 'Ali' are

found inscribed on the sword of Aurangzeb and the names of royal

weapons listed by Manucci include 'Ali's Help'.44 The following coup-

let in Persian is said to have appeared on Haidar's seal:

Fath Haidar was manifested, or born to conquer the world;

There is no man equal to Ali and no sword like his.45

37 Beatson, View, pp. I55-6. Kirkpatrick, Letters, p. 394.

38 This is well demonstrated in Rao, History, III, p. 525, n. 39, where an Indian

writer states that '. . . Haidar means tiger and that it was the title of Hazrat Ali .. .'.

In addition, in Tipu's Marine Regulations the word used for tiger to describe a

decoration on the model of a warship is sher and not babr. Sher is frequently translated

'lion'. Kirkpatrick, Letters, Appendix K, p, lxxix, n.6.

39 It does seem, though, that a visual distinction is made. Tipu's choice is very

clearly the tiger; nowhere is the lion found visually represented.

40 Dirks, Hollow Crown, pp 43 ff; Bayly, Saints, p. i59.

41 MMDLT, Haidar, p. 299.

42 Beatson, View, p. I55.

43 S. A. A. Rizvi, Shah Wali-Allah and His Times: A Study of Eighteenth Century Islam,

Politics and Society in India (Canberra, I980), p. 75.

44 Abdul Aziz, Arms andJewellery of the Indian Mughals (Lahore, I947) pp. 21-2, 29.

45 Cited in Rao, History, III, p. 524, n. 39. Fath Haidar was Tipu's grandfather.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE POWER OF TIPU S TIGER 263

The

Theswordsword

is Ali's symbolis

andAli's

on the respective

symbol chases ofand

a pair on the r

of

ofTipu's

Tipu's

tiger-muzzledtiger-muzzled

cannon are found the sword cannon

of Ali and a are foun

broad-bladed

broad-bladeddagger within tiger

dagger

stripes.46 The

within

extent of Tipu's

tigerdevo- stripes.46

tion

tionis demonstrated

is demonstrated

by his wish to fund the building

by his of a canal

wishfrom to fund th

the

theEuphrates

Euphrates

to Ali's burial place

to of Najaf.47

Ali'sOneburial

of his servants

place of Na

describes

describeshim wearinghim

a turban wearing

wound in a plaitedastyle

turban

known as wound i

'Moula Alee's shield'.48

To understand the significance of the above we need to understand

the nature of the world in which Tipu lived. This was a world in

which forces were at work which needed to be propitiated or invoked.

Long before they arrived in India, Muslims did not doubt the efficacy

of magic, the influence of the stars, the mysterious qualities of pre-

cious stones, and the importance of signs and omens.49 Humayun's

faith in astrology, for example, is well known. Both Haidar and Tipu

consulted Brahman astrologers about the most auspicious days to

carry out military manoeuvres, and their tenacious enemies, the Mar-

athas, did the same.5? The sacred number seven also featured strongly

in Tipu's life. Munshi Qasim writes that

On every Saturday he unfailingly made an offering to the seven stars, of

seven different kinds of grain, and of an iron pan full of sesame oil, and a

blue cap and coat, and one black sheep, and some money according to the

advice of the astrologers, which was bestowed on the Brahmins and others.51

The colour of the stone in the ring on his finger was changed every

day, '.. . according to the course of the seven stars', and the Depart-

ments in his government numbered seven.52 These were matters

which were taken very seriously and were not mere 'mumbo-jumbo'

or superstition. Francis Buchanan, who interviewed many astrologers

46 Victoria and Albert Museum, Heritage, p. 140.

47 Kirkpatrick, Letters, CCXXXIII. The implementation of this plan was to be

carried out on the way by the embassy despatched in 1786 to the Ottoman Sultan

at Constantinople. With his customary attention to detail, Tipu writes to the Darogha

of the Tosha-Khana at Seringapatam that the chest containing the funds for this

project should be labelled: 'In this chest are deposited the rupees composing the Nuzr

to be appropriated to the construction of an aqueduct [from the Euphrates] to the

sepulchre of holy.' Ibid., CCCC. The project never came to fruition.

48 Qasim, Account.

49 M. Mujeeb, The Indian Muslims (London, 1967), p. 379.

50 Narendra Krishna Sinha, Haidar Ali, 4th edn (Calcutta, 1969), pp. Iio, n. 3,

184; Mir Hussein Ali Khan Kirmani, The History of the Reign of Tipu Sultan Being a

Continuation of the Neshani Hyduri, tr. W. Miles, rpt 1844 edn (New Delhi, 1980), p.

178. On the day he was killed, Tipu had been advised by his astrologers that the

day was inauspicious. To counteract this he gave gifts to Brahmans and alms to the

poor, as well as carrying out certain rituals. Ibid.

31 Qasim, Account.

52 Ibid.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

264 KATE BRITTLEBANK

during his survey of the dominions of Tipu, wa

that astrology was '. . . looked upon as a c

having anything miraculous in it . . ..53 As w

with his astrologers, Tipu also consulted his p

to heal of these hakims who practised unani me

be closely associated with the supernatural.55

record of his dreams, writing them down a

sometimes recording his interpretation of th

also drew upon the power of the written wo

he was particularly fond, had woven in it the

O God! may thy fortune be ever awake

May fate ever be propitious to thee

May the flower of thy greatness forever lo

And be a thorn in the sides of thy enemies

On his right arm when he died was found a t

son describes it thus: '. .. sewed up in pieces o

amulet of a brittle metallic substance of the col

manuscripts in magic, Arabic, and Persian

power of these lines in Arabic is the baraka

onlooker.59 This power, literally blessing or

God, is often referred to as the 'charisma' of

transferred to his descendants upon his death

becomes a shrine. The meaning of Tipu's ban

The barakat conveyed by the complex callig

carried would have been a powerful protectio

Apart from the power of Ali's name, the in

illegibility of the design would have added to

33 Buchanan, Journey, I, p. 235.

34 Qasim, Account.

35 Bayly, Saints, p. 99.

36 Mahmud Husain, (tr.), The Dreams of Tipu Sultan: Tr

Persian with Introduction and Notes (Karachi, nd).

37 Qasim, Account.

38 Beatson, View, Appendix XXXIII, p. ciii. These m

have been given to Tipu by a Sufi pirzada. Eaton tells t

Bijapur receiving a piece of paper with a prayer writt

the muzzle of the city's cannon before firing it at the M

Sufis of Bijapur 1300-1700: Social Role of Sufis in Medieval

59 Annemarie Schimmel, Calligraphy and Islamic Cult

1984), pp. 84, 86. Schimmel writes: 'Even seemingly mea

can convey some blessing, provided they have been writt

by a skilled amulet maker; and inscriptions on metalw

mere fragments of blessing formulas, may still bear the

60 Ibid., p. 0o.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE POWER OF TIPU S TIGER 265

But does this really explain why Tipu chos

If the key element is his reverence for Ali,

sword, for example? What was it that at

'Lion (or tiger) of God'? Why should it

influence upon him that he chose the

emblem in his life? Was it just the prevalen

which prompted this choice, or their asso

answer, I believe, can be found if we look a

in which Tipu was operating.

In what are almost throwaway lines, wit

two twentieth-century south-Indian writer

for this enquiry, their inevitable closen

giving them a better understanding of

more distant. Mahalingam, referring to

emblem, believed it was chosen '.. . on accou

and Rao, in his History of Mysore, wrot

adopted by Tipu as emblematic of himself

this power to which they refer and why sh

That a ruler should be seen to be powerfu

Buchanan found that the Wodeyar fami

obscurity, that it [was] no longer looked

the natives in general [was] the only thin

of loyalty.'63 More significantly, there i

power of kings and the power of gods.

long perceived the power of divine being

form of the power which was claimed a

would-be rulers';64 and in south India the s

leads to the same perception of this sacre

the Hindu and Muslim communities.65 Th

within the religious landscape to all sout

refers to as 'divinities of blood and power',

tion are warrior goddesses, locally know

gods, both of whom are representations o

the Muslim tradition this power is repre

pir, who is perceived in virtually the sam

61 One only has to read Buchanan to realize that

the lives of villagers and travellers in the area. Jou

62 Mahalingam, Polity, p. 87; Rao, History, III, p

63 Buchanan, Journey, II, pp. 72-3.

64 Bayly, Saints, p. 2. See also pp. I84-5.

65 Ibid., p. 147.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

266 KATE BRITTLEBANK

goddesses.66

goddesses.66Known under

Known

various names,

under

such as Kali

various

or Kaliamma,

names

Durga

Durga or Mariamma,

or Mariamma,

these goddesses have

these

'an extragoddesses

endowment' of hav

sakti,

sakti,the dangerous

the dangerous

female energy of the

female

gods, and energy

are associated of t

with

with Siva.67

Siva.67

While

WhileBayly Bayly

is writing mainly

is writing

of the Tamil mainly

country, thereof

is nothe T

doubt

doubtthat these

that figures

these

were (and

figures

still are) found

werein the (and

Mysore still

dominions.68

dominions.68In nearly every

In village

nearly which Buchanan

everyvisited village

he en- whi

countered

counteredwhat he called

what 'destructive

he called

spirits', named,

'destructive

for example, sp

'Marima,

'Marima,Pualima, Pualima,

Mutialima, and Gungoma',

Mutialima,and commonly

and Gu

referred

referredto by theto

localby

Brahmans

theaslocal

'Saktis, or

Brahmans

ministers of Siva'.69

as 'Sak

The

TheBedars

Bedars

of Chitaldrug,

of in Chitaldrug,

the north of the State,

inbuilt

the a temple

north o

to

toKaliKali

on top on

of their

top durgof

or fort,

theirand propitiated

durg the orgoddess

fort, withand pr

offerings

offeringsof the heads

ofofthe

their victims

heads in battle.

of their

As a resultvictims

they

believed their fortress was unassailable.70 It is claimed that the name

Mysore itself is derived from Mahishasura, the buffalo-headed demon

slain by Durga, who, as Chamundi or Chamundesvari, is the tutelary

goddess of the Wodeyars.71 Whitehead identified seven 'Mari' deities

of Mysore city, all sisters, who were associated with Siva, and in

Mysore villages, Mahadeva-Amma, or the great goddess, and Huli-

amma, 'the tiger-goddess', were worshipped.72 These goddesses, fre-

quently associated with sickness, like small-pox for example, are

objects of great power and awe, which rather than being worshipped

are propitiated. Srinivas encountered them when he carried out

fieldwork in the late i940o in a village not far from Seringapatam,

the site of Tipu's capital. Referring to Mari (also known as Kali),

the local goddess, he wrote that she demanded blood sacrifices and

'. .. killed her offspring right and left when she was angry with them',

66 Ibid., pp. 27-3I, I34.

67 Ibid., p. 28. For a discussion of Durga-Kali as the martial deity or warrior

goddess see Wendell Charles Beane, Myth, Cult and Symbols in Sakta Hinduism: A Study

of the Indian Mother Goddess (Leiden, 1977), pp. 177-80.

68 The assumption here of cultural continuity between the area examined by Bayly

and that of Mysore is based primarily upon Stein's discussion of an identifiable

macro-region within southern India, which, with some regional variation, has dis-

played over the centuries a cultural homogeneity. Peasants, pp. 30-62; see also

pp. I00-I, 366-4i6. In addition, Tipu's patronage of a Sufi shrine at Penukonda

(see below), in the area examined by Bayly, reinforces this assumption.

69 Buchanan, I, pp. 242-3 and passim. Although the Brahmans claimed to abhor

the worship of these divinities, they sent surreptitious offerings in times of sickness.

70 Rao, History, III, p. 251.

71 Ibid., , p. 5I7; see also Henderson, Coins, p. ii6.

72 H. Whitehead, The Village Gods of South India, 2nd edn (Calcutta, 1921), pp. 29,

8o-i. The seven sisters are probably the 'Seven Mothers' or saptamatrikas referred to

by Burton Stein in Peasant, p. 238.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE POWER OF TIPU'S TIGER 267

while

while her devotees

her devotees

felt craven fear,

felt

not love.73

craven In addition,

fear, thenot

villa- love.73 In

gers

gers also also

worshipped

worshipped

Madeshvara (Siva),

Madeshvara

an awe-inspiring vegetarian

(Siva), an awe-in

deity,

deity,who also

who induced

alsorespect

induced

bordering respect

on fear, whosebordering

temple, on fea

situated

situatedin dense

in jungle,

densewas described

jungle, by Buchanan

was described

as 'very by Bu

celebrated'.74

celebrated'.74

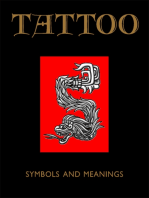

Fig.

Fig. I. Calligraphic

I. Calligraphic

design of a tiger's

design

mask. of a tiger's mask.

Source:

Source:Anne Buddle

Anne et al.,

Buddle

Tiger round

et the

al.,

Throne:

TigerThe Court

roundof Tipu

the

Sultan

Throne:

(1750-1790) The Court of

(London,

(London,I990), p.38.

I990), p.38.

That these warrior divinities are to be found within a culture that

is obviously martial is no coincidence. For example, the expansion in

the worship of the goddesses was tied to the rise in power, following

the decline of Vijayanagara, of the petty rulers or warrior chiefs

known as poligars or nayakas.75 Hindu rulers in the south, including

the Vijayanagara kings, celebrated a festival in honour of their patron

goddess - in the case of Vijayanagara it was Durga - which symbol-

ized conquest of a new kingdom and called upon the blessings of the

goddess for both themselves and their subjects.76 Known variously as

Navaratri, Mahanavami and Dasara, this festival was instituted in

Mysore by Raja Wodeyar in A.D. I6Io.77. The Muslim warrior pir,

73 M. N. Srinivas, The Remembered Village (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1976), pp.

295, 302.

74 Ibid., p. 302; Buchanan, Journey, II, p. I82.

73 Bayly, Saints, p. 30. 'Poligar' is a term coined by the British from the Tamil

'palaiyakkarar' or 'men of military encampments'. Stein, Peasant, p. 50. On the rise of

the Wodeyar Kartars of Mysore, see Rao, History, I.

76 Bayly, Saints, p. 66; Mahalingam, Polity, p. 28. See also Dirks, Hollow Crown, p.

167; Stein, Peasants, pp. 384-92.

77 Rao, History, I, p. 68. For a detailed description of the festival as it was celeb-

rated by Kanthirava-Narasaraja Wodeyar I in the seventeenth century, see pp.

I86-93.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

268 KATE BRITTLEBANK

saint

saint martyr,

martyr,or shahid

or shahid

was easilywas

accepted

easily

into accepted

this traditio

ated as he was with the world of the forest, which in Hinduism is the

world of Siva.78 Bayly writes: 'The martial pir was not a divisive

being in south Indian society. On the contrary, he was a figure of

universal power with deep roots in the world of the Tamil goddess

cults and power divinities'.79

And this leads us back to the tiger, who features strongly in Saivite

tradition. As we saw earlier, the Saivite Colas took the tiger as their

emblem. Madeshvara, for example, rides a tiger,80 and the link

between the warrior pirs and the martial goddesses is clearly displayed

when we realize that the former are often 'lion-mounted', while the

vehicle or vahana of Durga-Kali is the lion or the tiger;81 the tomb of

one lion-mounted warrior saint, Sultan Saiyid Baba Fakiruddin Hus-

sain Sistani, which apparently received patronage from Tipu, was

attended by a tiger.82 In addition, as noted above, the power of the

warrior goddesses is sakti, '... the dynamic, awesome, and sacred

power which is the goddess Durga-Kali'.83 In fact, Kali is Para-sakti,

absolute power,84 and '... the fury of Devi, the Supreme Goddess

may be projected as a ravenous lion or tiger'.85 The power of the pir,

on the other hand, is his barakat. But in south India these two concepts

have merged, so that in the biography of a Tamil pir, the word used

to describe his awesome power is not barakat but sakti.86

There is no reason to doubt that Tipu was steeped in this warrior

culture, that as a warrior and a ruler he wished to convey to both

his subjects and his enemies the awesome power that was his, a power

which in the mind of the south Indian was synonymous with the

power of the gods, the sakti and the barakat of the warrior goddess

78 Bayly, Saints, pp. 34, i20-I.

79 Ibid., p. I90. Tipu's close association with Sufi pirs and their descendants is

unquestioned. Kirkpatrick writes that the Mysore ruler was frequently in contact

with the 'priests' of shrines throughout the south, who, it seems, held him in very

high regard. Letters, pp. 306, 459. Also see, for example, Letters CCCLXIX,

CCCLXXXV.

80 Srinivas, Remembered, p. 299. It has been suggested that the tiger was

ive vehicle of Siva, prior to Nandi the bull. Bhattacharyya, 'Tiger-Cu

81 Bayly, Saints, p. 122; Beane, Myth, p. 52.

82 Bayly, Saints, pp. 122-3. See also her 'Islam in Southern India', p

83 Beane, Myth, p. 41.

84 Ibid., p. i80.

85 Heinrich Zimmer, Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilizatio

1946), cited ibid., p. 53. Alternatively, the tiger has been described as 't

Sakti'. As the master of this power, Siva '.. . carries the skin of the tiger

Alain Danielou, Hindu Polytheism (New York, 1964), p. 216.

86 Bayly, Saints, pp. 136-7.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE POWER OF TIPU'S TIGER 269

and the martial pir.87 Little wonder that he surroun

images of the tiger and used it as his emblem. F

animal was associated with Ali, the archetypal

whose name was invoked when going into battle.

ive symbol could Tipu have chosen than one whic

sakti of the tiger and the barakat of Ali's name: the

mask which glares out from his banner at all who

87 That Tipu, following his 'martyrdom' has been given th

is now himself revered as a shahid, complete with an 'urs fest

of his death, suggests that he achieved his aim. I am gratefu

manyam for this information.

This content downloaded from

223.187.96.167 on Sun, 16 Oct 2022 08:11:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Japan's Longest Day: A Graphic Novel About the End of WWII: Intrigue, Treason and Emperor Hirohito's Fateful Decision to SurrenderFrom EverandJapan's Longest Day: A Graphic Novel About the End of WWII: Intrigue, Treason and Emperor Hirohito's Fateful Decision to SurrenderRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- The Dragons of Somerset: And Their Relation to Dragons of the WorldFrom EverandThe Dragons of Somerset: And Their Relation to Dragons of the WorldNo ratings yet

- Assyrian Tree of Life OriginsDocument49 pagesAssyrian Tree of Life OriginsCaz ZórdicNo ratings yet

- Mason CoreaNativeArtists 1886Document5 pagesMason CoreaNativeArtists 1886terzian mikeNo ratings yet

- Wittkower 1939Document40 pagesWittkower 1939Anthony McIvorNo ratings yet

- A Yaksi Torso From SanchiDocument6 pagesA Yaksi Torso From SanchiArijit BoseNo ratings yet

- (26659077 - Manusya Journal of Humanities) The Rite of The Elephant Duel in Thai-Burmese Military HistoryDocument10 pages(26659077 - Manusya Journal of Humanities) The Rite of The Elephant Duel in Thai-Burmese Military HistoryCode 9No ratings yet

- تاكيتوس وتيبريوسDocument13 pagesتاكيتوس وتيبريوسmohammed hemidaNo ratings yet

- Camel Tracks: A History of Exploration, Warfare and Policing in the Modern Imperial AgeFrom EverandCamel Tracks: A History of Exploration, Warfare and Policing in the Modern Imperial AgeNo ratings yet

- On The Trail of Kume The Transcendent (M Bulletin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Vol. 79) (1981)Document25 pagesOn The Trail of Kume The Transcendent (M Bulletin (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), Vol. 79) (1981)Carlos Mercado LunaNo ratings yet

- Assyrian Tree of LifeDocument49 pagesAssyrian Tree of LifeseymourbuttstuffNo ratings yet

- Social Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art: Family Tree: Pebbles from North & South AmericaFrom EverandSocial Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art: Family Tree: Pebbles from North & South AmericaNo ratings yet

- WITTKOWER - Eagle and Serpent, A Study in The Migration of SymbolsDocument40 pagesWITTKOWER - Eagle and Serpent, A Study in The Migration of SymbolsormrNo ratings yet

- The Accomplished Muskrat Trapper A Book on Trapping for AmateursFrom EverandThe Accomplished Muskrat Trapper A Book on Trapping for AmateursNo ratings yet

- The Moths of the British Isles, First Series Comprising the Families Sphingidae to NoctuidaeFrom EverandThe Moths of the British Isles, First Series Comprising the Families Sphingidae to NoctuidaeNo ratings yet

- Japanese SwordDocument78 pagesJapanese Swordmaria jose carrion ramosNo ratings yet

- 6 - The Serpent Sword: RhonabwyDocument3 pages6 - The Serpent Sword: RhonabwynikoNo ratings yet

- 2008 Springer RopeKnotsDocument4 pages2008 Springer RopeKnotsmai refaatNo ratings yet

- Witkower Eagle and SerpentDocument40 pagesWitkower Eagle and SerpentJames L. Kelley100% (1)

- The Ivory King: History of the elephant and its alliesFrom EverandThe Ivory King: History of the elephant and its alliesNo ratings yet

- JSS 052 2d PhyaAnumanRajadhon ThaiCharmsAndAmuletsDocument38 pagesJSS 052 2d PhyaAnumanRajadhon ThaiCharmsAndAmuletsRichard FoxNo ratings yet

- An Exhibition of Japanese Sword MountsDocument5 pagesAn Exhibition of Japanese Sword MountsAbdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Symbols of The WayDocument240 pagesSymbols of The Waycelimarcel100% (1)

- Discovering Tut The Saga ContinuesDocument6 pagesDiscovering Tut The Saga ContinuesAryan KumarNo ratings yet

- Illustrated Guide to Samurai History and Culture: From the Age of Musashi to Contemporary Pop CultureFrom EverandIllustrated Guide to Samurai History and Culture: From the Age of Musashi to Contemporary Pop CultureNo ratings yet

- The Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharaoh of EgyptFrom EverandThe Life and Times of Akhnaton, Pharaoh of EgyptNo ratings yet

- Mughal Imperial Treasury - Abdul AzizDocument608 pagesMughal Imperial Treasury - Abdul AzizNehaVermaniNo ratings yet

- Politecnico Di Torino Porto Institutional Repository: (Book) Ancient Egyptian Seals and ScarabsDocument55 pagesPolitecnico Di Torino Porto Institutional Repository: (Book) Ancient Egyptian Seals and ScarabskbalazsNo ratings yet

- Notable Sabers of The Qing Dyna - UnknownDocument16 pagesNotable Sabers of The Qing Dyna - UnknownAbdul RehmanNo ratings yet

- Japanese Fairy Tales by OzakiDocument334 pagesJapanese Fairy Tales by OzakiEmma EmmaNo ratings yet

- The Ivory King: A popular history of the elephant and its alliesFrom EverandThe Ivory King: A popular history of the elephant and its alliesNo ratings yet

- M.B. BASTURK Thoughts On The Trident MotDocument13 pagesM.B. BASTURK Thoughts On The Trident MotAlireza EsfandiarNo ratings yet

- Three-Legged Animals in Mythology and FolkloreDocument12 pagesThree-Legged Animals in Mythology and FolkloreLloyd GrahamNo ratings yet

- Hiyama, Satomi and Robert Arlt - View of The Discovery of Two Stucco Heads of The Vidusaka in Gandharan ArtDocument7 pagesHiyama, Satomi and Robert Arlt - View of The Discovery of Two Stucco Heads of The Vidusaka in Gandharan ArtShim JaekwanNo ratings yet

- The Godhardunneh Cave Decorations of North-Eastern Somaliland By: I.M. LewisDocument3 pagesThe Godhardunneh Cave Decorations of North-Eastern Somaliland By: I.M. LewisAbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- MricchakatikaDocument210 pagesMricchakatikaDivyaNo ratings yet

- Gazelle JarDocument16 pagesGazelle JarsicoraxNo ratings yet

- Haiku Vol2Document456 pagesHaiku Vol2jn mt100% (1)

- Kara-Tur - The Eastern Realms (AD&D Forgotten Realms Oriental Adventures)Document280 pagesKara-Tur - The Eastern Realms (AD&D Forgotten Realms Oriental Adventures)Raymon Lawrence100% (1)

- Roy 2011Document32 pagesRoy 2011Bidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Nile Green - Who's The King of The CastleDocument18 pagesNile Green - Who's The King of The CastleBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- No Man Can Serve Two MastersDocument10 pagesNo Man Can Serve Two MastersBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Levi in Peter Burke - New Perspectives On Historical WritingDocument314 pagesLevi in Peter Burke - New Perspectives On Historical WritingBidisha SenGupta100% (1)

- Bhadra - Two Frontier Uprisings in Mughal IndiaDocument18 pagesBhadra - Two Frontier Uprisings in Mughal IndiaBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Aditya Mukherjee - Empire, How Colonial India Made Modern BritainDocument11 pagesAditya Mukherjee - Empire, How Colonial India Made Modern BritainBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- What Is Micro HistoryDocument7 pagesWhat Is Micro HistoryBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Response Paper 7 - BidishaDocument2 pagesResponse Paper 7 - BidishaBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- The Devadasis Dance Community of South India A LegDocument39 pagesThe Devadasis Dance Community of South India A LegBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- Response Paper 6 - BidishaDocument2 pagesResponse Paper 6 - BidishaBidisha SenGuptaNo ratings yet

- El Prezente: Journal For Sephardic Studies Jurnal de Estudios SefaradisDocument69 pagesEl Prezente: Journal For Sephardic Studies Jurnal de Estudios SefaradisEliezer PapoNo ratings yet

- mg318 AllDocument24 pagesmg318 AllsyedsrahmanNo ratings yet

- Holiness in A World of EvilDocument26 pagesHoliness in A World of EvilRUTH POLICARPIONo ratings yet

- Workers With Christ. (Mill Star)Document3 pagesWorkers With Christ. (Mill Star)Gideon OlschewskiNo ratings yet

- VVDocument11 pagesVVJOSEPH MONTESNo ratings yet

- Cut To The Chase - WK2 Curse of The Kobold EyeDocument33 pagesCut To The Chase - WK2 Curse of The Kobold EyeDiss onanceNo ratings yet

- Kahlil Gibran: Christopher BuckDocument18 pagesKahlil Gibran: Christopher BuckBassem KamelNo ratings yet

- Christ in Christian TraditionDocument466 pagesChrist in Christian TraditionEudes SilvaNo ratings yet

- Pak726 Thatta Uc Settlements L A3 v1 20190205Document1 pagePak726 Thatta Uc Settlements L A3 v1 20190205ej ejazNo ratings yet

- Forgiveness - ScriptDocument5 pagesForgiveness - ScriptCat RightonNo ratings yet

- Chinese Horoscopes - The SnakeDocument10 pagesChinese Horoscopes - The SnakeFrancis Marie Gonzales Casco100% (2)

- T T 2544575 Eyfs Phase 2 Christmas Phonics Advent Calendar PowerpointDocument27 pagesT T 2544575 Eyfs Phase 2 Christmas Phonics Advent Calendar PowerpointRuslanaNo ratings yet

- Lifting The Veil David Icke Interviewed by Jon RappoportDocument136 pagesLifting The Veil David Icke Interviewed by Jon RappoportT. Anthony50% (2)

- Kamulegeya - MAK - ResDocument3 pagesKamulegeya - MAK - ResKAWEESI ALEXANDERNo ratings yet

- Ancient Concept of Progress and Other Essays On Greek Literature and Belief PDFDocument222 pagesAncient Concept of Progress and Other Essays On Greek Literature and Belief PDFraul100% (1)

- Dhaka FETDocument105 pagesDhaka FETmarwabinti23No ratings yet

- Religious Harmony and Peaceful Co-Existence: A Quranic PerspectiveDocument16 pagesReligious Harmony and Peaceful Co-Existence: A Quranic PerspectiveFaryal Yahya MemonNo ratings yet

- Ps Moot PetDocument35 pagesPs Moot PetMehak RakhechaNo ratings yet

- SankardevDocument14 pagesSankardevChinmoy TalukdarNo ratings yet

- Richard Rohr 5Document90 pagesRichard Rohr 5fnavarro2013100% (1)

- Djinn Incantation Effective and - Eric HughesDocument5 pagesDjinn Incantation Effective and - Eric HughesWouter van WykNo ratings yet

- 5 Ways The Devil Attacks You and What The Bible Says You Should Do About ItDocument8 pages5 Ways The Devil Attacks You and What The Bible Says You Should Do About ItJosemaria KamauNo ratings yet

- Intercessionary Prayer To St. Mary in EnglishDocument4 pagesIntercessionary Prayer To St. Mary in EnglishAlbin JoyNo ratings yet

- Greek Drama FeaturesDocument6 pagesGreek Drama FeaturesMahmud MohammadNo ratings yet

- Sigil MagicDocument6 pagesSigil MagicTroy Kaye100% (1)

- Law Lesson - by SlidesgoDocument9 pagesLaw Lesson - by SlidesgoAfif NajmiNo ratings yet

- John 5 and Bar KokhbaDocument10 pagesJohn 5 and Bar KokhbamalikmarcinNo ratings yet

- Bonfante The UrnDocument16 pagesBonfante The UrntwerkterNo ratings yet

- Rite of Misraïm 4°-14°Document195 pagesRite of Misraïm 4°-14°Anniva DavidsonNo ratings yet