Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journalofnegroeducation

Journalofnegroeducation

Uploaded by

miracle 951013Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journalofnegroeducation

Journalofnegroeducation

Uploaded by

miracle 951013Copyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/235667194

Ecological Approaches to Mental Health Consultation with Teachers on Issues

Related to Youth and School Violence

Article in The Journal of Negro Education · June 1996

DOI: 10.2307/2967350

CITATIONS READS

40 1,193

3 authors, including:

Ron Avi Astor Ronald O Pitner

University of California, Los Angeles University of Alabama at Birmingham

316 PUBLICATIONS 5,527 CITATIONS 77 PUBLICATIONS 925 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

HIV/AIDS and Substance Abuse Interdisciplinary Workgroup View project

"HIV Stigma-Related Trauma" in African American HIV Positive Women: A Mixed Method Approach to Measure Development View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Ron Avi Astor on 29 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Journal of Negro Education

Ecological Approaches to Mental Health Consultation with Teachers on Issues Related to Youth

and School Violence

Author(s): Ron Avi Astor, Ronald O. Pitner and Brent B. Duncan

Source: The Journal of Negro Education, Vol. 65, No. 3, Educating Children in a Violent

Society, Part I (Summer, 1996), pp. 336-355

Published by: Journal of Negro Education

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2967350 .

Accessed: 22/09/2013 00:16

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Journal of Negro Education is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal

of Negro Education.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

EcologicalApproachesto Mental Health

Consultationwith Teacherson Issues

Related to Youthand School Violence

ofMichigan;and

Ron Avi Astor and Ronald 0. Pitner,University

BrentB. Duncan, HumboldtState University

Thisarticlearguesthatecologicalissuesareat thecoreofconcerns abouttheviolence

U.S.

students,

particularlythoseinlow-incomeurbancommunities, areexposedtoorexperience

within

oroutsideofschool.Consequently,itsuggeststhatecological

systems mental

theory-based health

forteachers

consultation shouldbean essentialcomponent ofschoolviolence services.

prevention

itoutlines

Further, a broadframeworkforgenerating andschool-based

teacher- interventions

based

on empiricaldatafromtheyouthandschoolviolence literatures,

ecological

systems and

theory,

consultation

consultee-centered models.

It lies within our reach, before the end of the twentiethcentury,to change the futureof disadvantaged

children.The childrenwho today are at riskof growinginto unskilled,uneducated adults, unable to help

theirown childrento realize theAmericandream,can, instead,become productiveparticipantsin a twenty-

firstcenturyAmerica whose aspirationsthey will share. The cycle of disadvantage thathas appeared so

intractablecan be broken. (Schorr,1988).

Almost everychild in my class knows someone who was murderedor shot.I know it gets to themand

theycan't always thinkabout the lesson or school-but it's hard forme to thinkabout lessons too. I know

that most of my kids are on the streetsafterschool and they don't have any place to go and I'm afraid

thatsome of them mightget shot or beat up. Some of the kids come in and talk about walking to school

by the boarded-up houses and I think.. ."thankGod theymade it to school today." (a third-gradeteacher,

froman interviewwith the authors,January1994)

Such contrastingimagesof hope and despairhave hauntedmanyteachersworkingin

Americanschoolsin thepastfewdecades.Increasingly, problemsrelatedto issuessuch

as childmaltreatment, poverty, racism,and familyand community violencetendto be

systemic and overwhelming in someschoolsettings.Additionally,

manyoftheteachers

in theseschoolsare themselves experiencingproblemssimilarto thoseoftheirstudents.

Often,theseadultsneitherconfidenorconsultwiththeirfellowprofessionals aboutthe

violentexperiencestheyand theirstudentsshareorwitnesswithinand outsidetheschool

Instead,theirintenseand profound

setting. ofhopelessness,

feelings frustration,

isolation,

and angerfocuson theirstudentsand theproblemstheseyouthbringto school.Com-

poundingthissituation, mostschool-basedinitiativesaimedat eliminating or reducing

theincidenceand impactof youthand schoolviolenceare primarily directedtoward

students,implemented by nonteaching fromoutsidethe school,and not

professionals

partofthedailyfunctioning ofteachersortheschool.As such,theyoftenfailtorecognize

thatteachers, and otherschoolpersonnelmustaddressissues of violencein

principals,

ongoing,intimate,and complexways thatare frequently overlookedin curricularpack-

ages,programs, or auditorium eventsaimedat addressingthisissue.

JournalofNegroEducation,Vol. 65, No. 3 (1996)

336 Copyright

? 1998,HowardUniversity

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Ourexperiences in mentalhealthconsultationpracticewithteachersand othereduca-

tionalprofessionalsinschoolsplaguedbyviolencehaveled us tobelievethatan expanded

andrefocused conceptual framework isneededtohelpeducatorsdevelopa comprehensive

and school-linkedapproachto violenceprevention. Thus,thisarticleoffersa framework

thatwillenableeducationaland psychological consultantsto moreclearlyconceptualize

theenvironmental and community contextofyouthand schoolviolence:ecologicaldevel-

opmentaltheory.We posit thatthe mentalheathconsultantsmusthave a thorough

understanding oftheecologicalcontextinwhichyouthandschoolviolenceoccurs.Further,

by blendingtheempiricalliterature on youthand schoolviolencewithteacher-centered

(Caplan& Caplan,1993)and ecologicaldevelopmental

case consultation theory(Bronfen-

brenner,1979),consultation servicescan be reframed to addresstheneeds of teachers,

otherschool-based andstudents

professionals, affected

ineducationalsettings byviolence.

Empiricalfindings toschoolviolencecanbe viewedthrough

relevant thelensofecological

developmental theoryand can,in turn,be used to guide and directconsultation.

This articlehas two purposes.First,it presentsa discussionof practicalissues we

believemustbe consideredwhenconsulting withteacherson issuesrelatedtoyouthand

schoolviolence.Thoughthe literature notesthatyouthand schoolviolenceoccursin

everycommunity in theUnitedStatesand in almosteveryschool(Lee & Croninger, 1995;

Metropolitan Life InsuranceCompany & HarrisPoll, 1993,1994,1995),this discussion

focuseson violenceinschoolsthatarelocatedinlow-income andhigh-crime communities

in theU.S. becausethesecommunities and schoolshave been shownto be moresignifi-

cantlyaffected by or involvedin violenceof a more lethaland interminable nature

(AmericanPsychological Association[APA],1993b;Astor,Behre,Fravil,& Wallace,1997;

Furlong,Babinski,Poland, & Mufioz,1996;National CenterforEducationStatistics

[NCES],1991).Second,it presentsecologicaldevelopmental theoryas an important tool

formentalhealthconsultants inhelpingteachersand otherschoolpersonnelframeappro-

priatequestionsand generateeffective, school-basedresponsesto youthand school

violence.

THE SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Whiledecreaseshavebeennotedin thenumberofadultviolentcrimescommitted in

citiesacrosstheUnitedStatesin thelast10 years,thenumberoflethalcrimescommitted

by adolescentsand youngchildrenhas burgeoned(Dohrn,1995;Sautter,1995).Indeed,

American youthhavebecomeparticularly vulnerable toassaultsand injury-related deaths

(Hausman, Spivak, & Prothrow-Stith,1994;Kachur et al., 1996).Between1985 and 1993,

therateofhomicideamongadolescents grewfaster thanitdid amongthegeneralpopula-

tion(Ash,Kellermann, Fuqua-Whitley,& Johnson, 1996).Homicidehasbecomethesecond

leadingcauseofmortality amongall adolescentsin theU.S. (Satcher, 1995).Nationaldata

revealthatadolescentsare at highand increasing riskofbeingvictimsand perpetrators

ofviolentacts.However,closerexamination of thedata revealsthatnotall adolescents

are equallyat risk.Forexample,theprevalenceofassaultiveviolenceand injury-related

deathsis morepronouncedamongmaleadolescentsand youngadults.As Harlow(1989)

reports,assaultinjuriesamongthisgrouparenotonlymorefrequent butaremorelikely

tobe severe.Indeed,youngmalesexperience violentcrimesat a ratedoublethatoftheir

femalecounterparts 1990;Hammond& Yung,1993).

(Christoffel,

Thepatterns ofyouthviolenceareevenmoredisconcerting whenspecificracial/ethnic

groupsare examined.AfricanAmericanyouthsin particularare at thegreatestriskof

beingbothvictimsand perpetrators ofassaultivecrimes(Hammond& Yung,1993;Gray,

1991;Isaacs,1992;Prothrow-Stith & Weissman,1991;Shakoor& Chalmers,1991).Homi-

TheJournalofNegroEducation 337

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

cideis theleadingcauseofdeathforAfrican American youths(Ashetal.,1996;Hammond

& Yung,1994;NationalCenterforHealthStatistics, 1992).As Ash etal. (1996)note,the

rateoffirearm-related homicidesmorethantripledforAfrican American maleadolescents

from1985to 1993.

Garbarino,Dubrow,and Pardo(1992)comparedtheeffects ofviolenceon childrenin

war-tomdevelopingcountries and childreninimpoverishedinner-cityareasoftheUnited

States.Theirfindings suggestseveraldisturbingconclusions.First,theyfoundthatpoor

childreninU.S.innercitiesobserveandexperience as muchormoreviolencethanchildren

in manywarringnations.Second,whencomparingshort-and long-term mentalhealth

implications,theymaintainedthatthe U.S. childrenfaredworseon bothcounts(e.g.,

post-traumatic sleepand conductdisorders,

stress,depression, etc.)thandid thechildren

in somewar-torn countries.Moreover,in someinner-cityU.S. communities, theschool,

thoughsurrounded by whatoftenappearstobe senselessand uncontrollable familyand

community violence,is theurbanchild'sonlysafehaven.

The Natureand Frequencyof School Violence

Violent

School-Associated Deaths.Consistent withthepatterns oflethalviolenceamong

adolescentsand youngchildrennotedoverthepast decade,an increasehas also been

notedin thelethality oftheviolentactsthatoccurin thenation'sschools.Althoughit is

notentirely clearwhatpercentofyouthviolenceoccursin schoolsettings, manyforms

of violencebetweenyouthsare associatedwiththe social or physicalcontextsof the

school.As earlyas 1978,theSafe SchoolStudymandatedby Congresssuggestedthat

schoolsmaybe themostviolentsetting forAmericanyouths(NationalInstitute ofEduca-

tion& U.S. Department ofHealth,Educationand Welfare, 1978).Thefindings ofa recent

Galluppoll indicatethat92% ofthegeneralpublicbelieveviolenceis a seriousproblem

in U.S. schools(Elam,Rose,& Gallup,1994).

Reporting on data gatheredfrom1992to 1994,Kachuretal. (1996)estimatethatthe

overallincidenceofschool-associated violentdeathsforchildrenin grades9 through12

was 0.27per 100,000student-years. Theyfurther contendthatracial/ethnic in

minorities

urbanschoolswereat greatestriskofinvolvement in theseincidents.

AfricanAmerican

studentsin all gradeshad thehighestestimatedrateofschool-associated violentdeaths

(0.28per100,000student-years forAfrican American students comparedto0.03per100,000

forWhiteAmericanstudents).Similarly, such deathsweremorelikelyto occuramong

studentsin urbansettingscomparedto thosein ruralor suburbansettings(.18,.09,and

.02 per 100,000,respectively). The mostshockingaspectof thesenumbers,however,is

thattheyrepresent actualdeathsand do not includeattempted murders,assaultswith

deadlyweapons,sexualassaults,feloniousbattery, or beatingsthatdo notresultin fatal

injuries.As such,theypresenta conservative and extreme measureofthedegreeofschool-

associatedviolencethatis reallyoccurring and can onlyhintat theactualprevalenceof

violencein ournation'sschools.

Injury-Related

Fighting. A recentnationalsurveyconductedby theCentersforDisease

Controland Prevention (1996)notesthat46%ofhighschoolmalesand 30%ofhighschool

femalesreportedbeingin at least one fightover a 12-month periodthatwas serious

enoughto requiremedicaltreatment by a doctoror nurse.Nevertheless, aggregated

nationaldata hide some important regionaldifferences and geographicalvariationsin

the scope of school violence.For example,duringa 12-month period,42% of polled

studentsin Detroitschoolsreportedbeingin injury-related fightscomparedto only28%

of studentsin San Franciscoschools.Likewise,the12-month incidenceof suchfighting

338 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

formale highschoolstudentsin Detroitwas 199.6fightsper 100 studentscomparedto

96.4per 100studentsin San Francisco.

Whereand WhenSchool ViolenceOccurs

Previousstudieshave underscored theimportance ofdocumenting whereand when

schoolviolenceoccurs.For example,thelandmarksafeschoolstudyconductedduring

the1970sfoundthatviolenceusuallyoccurredin areassuchas stairways, hallways,and

cafeterias;

and thattheriskofschoolencounterswas greatestduringthetransition

periods

betweenclasses(NationalInstitute ofEducation& U.S. DepartmentofHealth,Education

and Welfare,1978).Thatstudyfurther notedthat80% of theviolentcrimescommitted

againstyouthand adultsat schoolsoccurredduringregularschoolhours.Manyother

articlesand policyreportshave implicatedtheseand otherdangerousschoollocations

and times (Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development,1993; Goldstein,1994;

D. C. Gottfredson,1995;G. D. Gottfredson,

1985;Kachuretal., 1996;Olweus,1991;Slaby,

Barham,Eron,& Wilcox,1994).Ofall assaultsandrobberiesreportedatsecondaryschools,

forexample,a NationalInstitute ofEducationand U.S. DepartmentofHealth,Education

and Welfare(1978)studyreportsthat32% occurredbetweenclass periods,while26%

occurredduringlunch.

Perceptionsof School Violence

Severalnationalsurveyshave indicatedthatschoolviolenceis a seriousconcernfor

elementary schoolteachers(Metropolitan LifeInsuranceCompany& HarrisPoll,1994;

NCES, 1991).Likewise,commonthemesand difficulties emergewhenteachers'concerns

about schoolviolenceare ecologicallyoriented.For example,Astor,Meyer,and Behre

(1997)notethatduringtheconsultation process,teachersoftendiscussschoolviolence

as itrelatesto otherecologicalissuessuchas teacherburnout, absenteeism,and turnover

rates.Teachersalso mentionisolation,lackofadministrative support,and lackofclarity

abouthow tointervene whenviolenteventsoccuras issuesfurther hinderingtheirability

to intervene effectively.

Otherpractitioners workingin schoolsare also likelyto encounter potentiallylethal

or lethaleventsin theirworkplaces.Forexample,in a recentnationalsurveyon school

violence,71% of school-basedsocial workersreportedthe occurrenceof a potentially

lethalor lethaleventin theschoolsin whichtheyservedduringthelastacademicyear

(Astoretal., 1997).Over 87% of thesocial workerspolled who servedin low-socioeco-

nomic-status, schoolsreportedsimilareventsin theirschools.However,very

inner-city

high percentagesof social workersin urban (78%), suburban(70%), and rural(81%)

schoolsalso reportedat leastone potentiallylethalor lethaleventat theirschoolsin the

same year.In anothersurvey,over 30% of school-basedsocial workersindicatedthat

theyconsideredleavingtheprofession due to theirconcernsoverschoolviolence(Astor

etal., 1997).

ECOLOGICAL SYSTEMS THEORY AND MENTAL HEALTH CONSULTATION WITH TEACHERS:

A FOCUS ON YOUTH AND SCHOOL VIOLENCE

An understanding oftheinterplay ofhistorical, and psychosocial

sociocultural, forces

in theschoolsettingis a prerequisite

foranytypeofeffective mentalhealthconsultation

withteachers(Caplan & Caplan, 1993).In guidingthe developmentof teacher-based

interventions,

theconsultant mustexploreand monitoran interconnected fieldofforces:

the school community, the teachers'and consultants'representative

organizationsor

TheJournal

ofNegroEducation 339

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

agencies,teachersand consultants individually,and youthclientsand theirfamilies.

Professionalsin severalfieldsrelatedto childand familymentalhealthhave developed

modelsthatemphasizea multidisciplinary and coordinated approachto servicedelivery

(APA, 1993a;Behrman,1992;Burchard,1990;Morrill,1992;Stroul& Friedman,1986).

Ongoingmultidisciplinary consultation-collaborationservicesare essentialcomponents

of thesemodels.Unfortunately, however,mostare psychologically orientedand focus

mainlyonemotional, behavioral,orcognitive deficits

withinindividualchildren oryouth.

Thespecifictoolsforhelpingconsultants understand theoverburdened ecologicalenviron-

mentsofviolence-plagued schoolsarerarelydescribedin theconsultation nor

literature,

are thecomplexservicedeliverysystemsconfounding contemporary youthand school

violenceinterventioneffortsdiscussedto anygreatextent.

EcologicalSystemsTheory

Ecologicalsystems theory is an important toolformentalhealthconsultants inhelping

teachersand otherschoolpersonnelframeappropriate questionsand generateeffective,

school-basedresponsesto youthand schoolviolence.The foundational workof Lewin

(1935,1951),Bronfenbrenner (1977,1979,1980),Hobbs(1966),Garbarino (1982),Garbarino

et al. (1992),and others(Jessor, 1993;Sameroff, Seifer,Barocas,Zax, & Greenspan,1987;

Sameroff & Fiese,1990) articulatesand definesa theoretical and researchbase foran

ecologicalmodelofdevelopment. Theseauthorsdescribea multilevel approachforconcep-

tualizingand studying thedevelopment ofthechild.Bronfenbrenner (1979),forexample,

identifies fourinseparableand interconnected systemsthatframeall humantransactions

and influence humandevelopment-themicrosystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and the

macrosystem-which togetherencompassthe ecosystem.An integration of schematic

representations of Bronfenbrenner's conceptualizationby Hobbs (1966) and Garbarino

(1982)visuallydepictsthechildin thesefoursystems(see FigureI).

TheMicrosystem. Microsystems arethosedomainsinvolvingdirectinteraction between

a childand an environment. Accordingto Bronfenbrenner (1979),a microsystem is "a

patternof activities, roles and interpersonal relationsexperiencedby the developing

personin a givensettingwithparticularphysicaland materialcharacteristics" (p. 22).

Thereare manymicrosystems in a child'slife-his or herimmediateinteractions within

thehome,schoolsetting, or neighborhood peergroup,forexample-each ofwhichcan

be further brokendown intosmallerand smallersubsystems.

Researchsuggeststhatchildren developingin overburdened orimpoverished commu-

nitiesfrequently have a verylimitednumberofsupportive microsystems. Someofthese

childrenmay onlyhave the school as a safe physicalsetting(Garbarinoetal., 1992),

whileothersmaybe experiencing theirdevelopment in potentiallyharmful, negative,or

functionally nonexistent microsystems. Bothcircumstances place an enormousstrainon

thechild,family, and school.In turn,teachersworkingwithchildrenfromphysically or

psychologically impoverished environments mayfeelhopelessor overwhelmed by the

added burdensplacedon them.

Froman ecologicalperspective, havingdetailedknowledgeof both students'and

teachers'microsystems is essentialforeffective mentalhealthconsultation, particularly

as itrelatesto theprevention ofyouthand schoolviolence.Forexample,an ecologically

sensitiveconsultant will ask questionsthathelp teachersexploreand becomeaware of

theeffects of thenumberand qualityof normative developmental settingsavailableto

thestudentsin theirclassrooms.

TheMesosystem. Themesosystem referstothatpattern ofinteractionsand relationships

betweentwoor moremicrosystems in whicha childparticipates. Forexample,relations

340 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

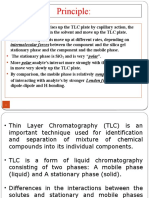

FIGURE I

An EcologicalRepresentation

ofChildDevelopment:

TheMicro-,Meso-,Exo-,and Macrosystems

-> -> '-* TIMEANDDEVELOPMENT - -> >

Politics Meda Macrosystem Religion Holidays

wcpMesosystemm

\ ~~~Nfosystem Microsystem

/i g y

/policeD<pt.\ R *wk / ~~~~Parents

/ Doctors \/Sibl/ngs a

wyers Gags F EcI

COMMUNITYAIL

i

c ol Yuth Groups Pak CHrL oeEnvirommeict/

NEIGHBORHOOD | SCHOOL

T

\ Pl\

Play Grounds

Teachers

Seach'Ai

Aid Peers

PEe!.inst

Centers

Shopping SpeechTherapist

Psychologists

'ea1e Microsystem Microsystem

O

47

Mesosystem /y

Laws Macrosystem Norms

AdaptedfromHobbs (1966) and Garbarino(1982).

The Journalof Negro Education 341

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

betweena child'shome and school constitute a mesosystem. Mesosystemsassume a

varietyofformsand combinations thatinclude,in Bronfenbrenner's (1979)view,"other

personswho participate activelyin bothsettings, intermediate linksin a socialnetwork,

formal andinformal communications amongsettings, and,againclearlyinthephenomeno-

logicaldomain,theextentand natureofknowledgeand attitudes existingin one setting

abouttheother"(p. 25).

Researchsuggeststhatchildrenin overburdenedenvironments frequently have

extremely negativeor nonexistent mesosystems. Veryoftenin such settings, students'

parentsand peergroupshave historiesofextremely negativepersonalexperiences with

schoolsystemsrangingfromschooldropoutto academicfailure.For example,Duncan

and Burns(1994)foundthatparentsoftroubledchildrenfrequently reporthavingsuch

seriousproblemswithschoolpersonnelthatcommunication patternsare markedlydis-

turbed.Perhapsmorefrequently, overburdened schoolstendto avoid suchparents,and

vice-versa.Moreover, withaggressive andemotionally impairedchildren, parentalcontact

is frequentlyrestricted to discussionofsevereproblems.

A restricted rangeof microsystems leads to a limitednumberof mesosystems such

as therelationship betweentheschooland socialserviceagencies,youthprograms, police,

and volunteer organizations. In suchinstances, teachersoftenstrugglewiththequestion

ofwhoseroleor responsibility it is withinthebroaderecologicalenvironment to handle

a child'sproblem.Quitecommonly, theyresistorarereluctant toaddresssocialproblems

thattheysee as theresponsibility ofothermicrosystems. Someteachersmayblameother

microsystems suchas thehomeormentalhealthsystemfortheproblem, and subsequently

designatetheproblemas outsidetheresponsibility of theschool.However,ecological

theorymaintainsthatthehealthymaintenance of mesosystems are essentialforproper

individualas well as organizational development.

TheExosystem. As Bronfenbrenner (1979)relates,theexosystem refers to "one ormore

settingsthatdo notinvolvethedevelopingpersonas an activeparticipant, butin which

eventsoccurthataffector are affected by whathappensin the settingcontaining the

developingperson"(p. 25). Schoolboarddecisions,stressful eventsin a parent'semploy-

ment,eventsin theteacher'sfamilylife,or changesin thenetworkof a child'sparental

supports(e.g.,friends) areexamplesofsuchevents.Whiletheyaffect thechild'smicrosys-

temsin an indirectmanner,theycan also alterthe qualityand natureof interaction

betweenthechildand each ofthemesosystems.

Exosystem factors havebeenshowntoexertpowerful influence onandwithinimpover-

ishedsettings(APA,1993a;Eron,Gentry, & Schlegel,1994;Garbarinoetal., 1992;Jessor,

1993;Hammond& Yung,1993).In suchsettings, parentalunemployment orunderemploy-

ment,highratesofteacherburnoutorstress,internal battlesamongschooldistrict person-

nel,conflictive schoolboard policies,or nonexistent or fragmented provisionof school

servicesand equipmenthave a huge and negativeimpacton children'sdevelopment.

TheMacrosystem. Themacrosystem includestheoverallstructural patterns oftheculture

in whicha child lives and grows.The economy,laws, politicalevents,and religious

beliefsof a societyor community fall withinthe macrosystem domain.Accordingto

Bronfenbrenner (1979),themacrosystem refersto "consistencies, in theformand content

oflower-order systems(micro-, meso-,and exo-)thatexist,or couldexist,at thelevelof

the subcultureor the cultureas a whole,along withany beliefsystemsor ideology

underlying such consistencies" (p. 26). Thisincludesthesimilarities in thestructure of

education,familycustomsand behavior,and government withina specificcultureas well

as thedissimilarities betweensubgroupsor subsystems.

Culturaldifferences at thesocietallevelare obvious,butthesedifferences maynotbe

as apparenton an interpersonal level.Forexample,schoolsservingurban,minority, and

342 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

low-incomestudentshave been shownto be underfunded at everylevel comparedto

thoseservingsuburban,non-minority, and middle-to upper-income students(Kantor&

Brenzel,1992;Kozol, 1991).Additionally,however,thelackofresourcesdevotedto the

formermay cause inordinatestressand organizationalconflictwithinthesesettings.

Subsequently,theirteachersmayframea violenceprobleminterpersonally whenin fact

itis primarily

relatedto lackofresourcesorinequitablepolicydecisions.In suchsettings,

thementalhealthconsultant shoulddirectteachersto exploretherelationship between

themacrosystem and theirown interpersonaltransactionsof concern.

Teacher-Centered MentalHealthConsultationWithinan Ecological

SystemsFramework

Understandinga child'sdevelopment is onlypossiblewhenone understands thetotal

contextinwhichhe orshelives.Viewingdevelopment as a continualtransaction

between

thechild'smicro-,meso-,exo-,and macrosystems requiresthementalhealthconsultant

to considerdevelopment on a varietyoflevelsand in a multitude ofnaturalsettings.

In

thislight,behavioris considerednormalor abnormalonlyin relationto a complexset

ofdirectand indirectreactionsand transactionsbetweenthechildand elementsofeach

oftheseecologicalsystems. Thus,a childwho exhibits behavioralor emotionalproblems

is symptomaticofdisequilibriumin theecosystem.Itis notonlythechildwhois troubled,

but ratherthe entireecosystemof which the child is part.As Conoley and Gutkin

(1986)note:

From this perspective dysfunctionalbehavior patternsexhibitedby individuals are seen as failures in

matchingenvironmentaldemands with individual skills, attitudesor developmental stages... Problems

exist not withinpeople or environmentsper se, but ratherwithinthe interactionbetween the individual

and the contextualcomplexity.(p. 403)

The underlyingpremiseofteacher-centered mentalhealthconsultation is to improve

theabilityofthosewithdirectresponsibility forchildren withinoneofthemostimportant

elementsofthemicrosystem to addressfourcriticaldeficitareas:teachers'lackofknowl-

edge,lackofskill,lackofprofessional objectivity,

and lackofself-confidence (Caplan &

Caplan,1993).Whenecologicalor systemicissues are theprimaryfocusof a teacher's

problems, thedistinctionsbetweenthesefourareasbecomenoticeably blurred.Moreover,

in highlyoverburdened or distressedenvironments, all fourdeficitsmay be present

simultaneously.

In such settings,

however,it becomesless helpfulto conceptualizethe problemas

residingwithintheteachers. Anexclusivefocusonteachers inadvertentlyplacestheblame

ontheseprofessionals whentheproblemis infactsystemwide. Consequently, consultation

inoverburdened settingsshouldfocusongroupempowerment ororganizational strategies

thatteacherscan use to overcomeecologicalbarriers. Thisapproachcontrasts withmany

currentviolenceinterventions, whichfocusonly on the individual(e.g., social skills

training)and thusimplythattheproblemexistswithintheindividualand can be solved

by changingtheindividual.Theecologicalapproachreframes theproblembyexamining

how the individualor groupwith commonproblemscan alterselectaspectsof the

burdensomecontext.

Theecologicalapproachtomentalhealthconsultation inthedistressed schoolenviron-

mentpositsthatinformation on youthand schoolviolenceis a toolforteacherempower-

mentratherthana prescription forsolvingtheproblemor an excuseforinaction.What

at firstmay appear as teachers'lack of objectivityor confidence withregardto these

issuesmayin factbe due to theirlackofknowledgeaboutand awarenessoftheeffects

of the environment or of the availabilityof community resourcesand organizational

support.Thus,theconsultant is encouragedto sharewithhis or herteacher-consultees

TheJournal

ofNegroEducation 343

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

current research findings on theirgeneraland specific areasofconcernas wellas informa-

tionon resourcesand supportive programs. Thisknowledgecanfrequently inform teach-

ers' decisionmakingand facilitateeffective teacheradaptationand problemsolving

aroundissuesofviolenceandviolenceprevention. Inthesetypesofsituations, consultation

servicesshouldbe guidedby thefollowingquestions:

* Is theteacherawareofresearchdirectly relevantto theissue or topicofconcern?

* Is theteacherknowledgeable aboutthepotentialschoolor community resourcesavail-

able regarding thisproblem?

* Has theteacherthoughtof,discussed,or assessedhis or herconcernwiththeparents?

* Has the teacherdiscussedtheproblemwithpotentialsourcesof supportwithinthe

school?

* Is theteacheropen to receivingor availableto receivethisinformation?

* Aretherenaturalsupportswithinthesettingthattheteacherhas notutilized?

* Arethereotherconsultees withinthesystemexperiencing thesameorsimilarproblems?

Teachers'lack ofskillin handlingproblemsrelatedto youthand schoolviolencein

overburdened settingsmaybe due to deficitsin theirpreserviceor inservicetraining,

administrative support,parentalsupport,co-teachersupport,or inadequatephysical

resources. Underthesecircumstances, thementalhealthconsultant's ethicalresponsibility

is tohelpteachers identify resourceswithintheirschoolcommunities, orbuildings

districts,

thatcan addresstheproblemmoreeffectively or help teachersgaintheskillstheyneed

to do so. Towardthisend,theconsultant's knowledgeofschool,district, and community

resourcesis essential.Consultantsshould also be aware thatpersonsor organizations

withtheskillstoaddressschoolandyouthviolencemayexistwithinanothermicrosystem

suchas thechild'shome,neighborhood, or largercommunity.

Caplanand Caplan's(1993)approachis particularly comprehensive and detailedwith

regardtotheobstaclesteachers'lackofobjectivity maycreate.However,in overburdened

settings,teacher-consultees mayexpressstrong, openlyracist,derogatory, or prejudicial

attitudes towardcertaingroupsina schoolcommunity ortowardparentsand/orchildren

of a particular racial,ethnic,or religiousgroup.Whenthesefeelingsand attitudesare

systemic and embeddedwithintheschooland schooldistrict organizations,mentalhealth

consultants mustweightheeffects-individually andcollectively-of teachers'stereotypi-

cal attitudes,behaviors,and feelingstowardvariouspopulations.

Our consultation experiencessuggestthatschoolwideor groupinserviceworkshops

or smallgroupdialoguesessionsare themosteffective meansfordispellingstereotypes

withininstitutions. Encouragingand structuring positivecontactbetweentwo or more

microsystems, suchas theschooland thehomeor theschooland community groups,is

also a usefulmeansofsuspendingteachers'tendenciesto view theirstudentsand their

students'parentsand homecommunities stereotypically.

Froman ecologicalperspective, teachers'lack of confidenceabout theirabilityto

handleproblemsofyouthand schoolviolenceis theresultofa numberofrelateddeficits:

a lackofadministrative support;insufficient remuneration or otherformsofrecognition;

thepresenceofan abundanceofoverwhelmed, disturbed, or otherwisedifficultstudents

in theirclassrooms;and inadequatepreservice or inservicetraining abouttheirstudents

andtheproblemstheyface.Factorsoriginating outsideoftheschoolsetting-thosearising

inteachers'family lives,forexample-also lead toan erosionofself-confidence. Ironically,

therehas beenverylittleresearchinvestigating how teachers'personallivesand stresses

outsidetheirworklivesaffect thequalityoftheirteaching, theirmotivation to teach,or

theirself-confidence in theirabilityto teach.Consultants shouldbe awarethatexternal

stressescan affectteachers'work performance. Similarly,stressorswithinthe school

bureaucracy itselfcan diminishteachers'feelingsofself-efficacy.

344 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

In schoolswhereteachersfacea numberof deficitssuch as poor salaries,low per-

pupilexpenditures,highstudentfailurerates,and difficult

studentpopulations,teachers

maybe experiencing severestressand notbe awarethatthesituationis largelyoutside

oftheircontrol.Thementalhealthconsultantin thistypeofsetting

mustbe acutelyaware

thatlack of resourcesand supportcreatesa situationin whichteachers'lack of self-

confidenceis appropriate

and normative.

The Complexityof School Violence:Social Statusand Hierarchy

The following statement,

relatedto us by an inner-city

elementary

schoolprincipalin

1992,capsulizesa recurring

themein our consultationswithschoolprofessionals:

I have about 25 childrenin thisschool who are constantlygettingintofights.They are in my officeeveryday

almost all the time... it doesn't matterwhich teachertheyhave, they act out and get into fights.I know

theyare all having some troubleat home and the stufftheysee on the streetsdoesn't help any. If we can't

get to these childrensooner or later theywill get into more serious things.I've seen it beforewith other

youngstersover and over again.

Ecologicaltheorysuggeststhatnegativesocialattribution cyclesbetweenpeers,school

personnel, and highlyaggressivechildrenmaycontribute to theperpetuation ofviolence

in theschoolsetting.It further suggeststhatresearchon and observation ofthewaysin

whichclassroomand school social hierarchiesinteractwiththosechildrenwho are

involvedin youthand schoolviolencecanbe used todesignclassroominterventions that

arewithintheteacherscontrol. Forexample,severalrecurring themesemerging fromour

consultationswithschoolpersonnelare corroborated in theliterature. One of themost

compellingof theseis thefindingthathighlyaggressivechildrenare overwhelmingly

perceivednegatively by peers,teachers, and schooladministrators (Beynon& Delamont,

1984;Cairns& Cairns,1991;Lancelotta& Vaughn,1989;Patterson, 1982;Pearl,1987;

Younger& Piccinin,1989).

Conversely,thesechildrenhave negativeperceptions ofothermembersoftheschool

socialsystem(Dodge,1980,1986,1985;Guerra& Slaby,1989;Dodge,Pettit, McClaskey,

& Brown,1986).Theyalso seemtobe awareoftheirnegativesocialstatus.As such,they

cometoviewschoolas a punitivesetting and subsequently losetheirmotivation toremain

investedin schoolsocialsystems.Thispatternof socialrejectionand isolationhas been

outlinedby Cairnsand Cairns(1991)and others(Coie, Underwood,& Lochman,1991;

Younger& Piccinin,1989),who positthatby thethirdgrade,highlyaggressivechildren

tendto gravitatetowardotheroutcastor similarly rejectedyouthand formaggressive

peer groups.Eron's (1987) longitudinalstudysuggeststhatearlyaggressionactively

interferes

withinitialacademicgains,thuscontributing significantlyto a patternofaca-

demicfailure.Forsomechildren, theseschool-based cyclesmaybe veryfirmly established

as earlyas kindergarten and firstgrade(Patterson, Capaldi,& Bank,1991).

Whatalso emergesfroma reviewof developmental researchis a pictureofa strong

socialhierarchy withinschoolsthatseparateschildrenwho "act out" theiraggressions

fromthosewho are nonaggressive. Froma youngage, manyaggressivechildren(or

groupsofaggressivechildren) maintaina socialstatusnearthebottomoftheschoolsocial

hierarchy.Thathierarchy is maintained bothby theaggressivechildren'sactionsand by

adults'and peers'perceptions ofbehavioralpatterns withintheschool.

Based on the stability of peer and teacherratingsof aggressivechildren,it is clear

that,withina givenschool setting,virtuallyeveryoneknowswho thesechildrenare,

and thisremainsconstantformostchildrenthroughout theirelementary schoolyears.

However,teachersand principalsin elementary schoolshave the abilityto influence

children'ssocialgroupsand playgroups.Iftheybecomeawareofthissocialpatternthey

can develop ways to increasean aggressivechild'spositiveinvolvement with"non-

TheJournal

ofNegroEducation 345

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

rejected"childrenand stop the trajectoryof isolationand rejection.Ecologicaltheory

suggeststhatteachersshoulduse thisknowledgeto generatesolutionsto youthviolence

that:(a) raisethesocialhierarchyofhighlyaggressivechildrenwithintheschoolsocial

hierarchy, and (b) facilitate

morepositiveperceptions betweenthesechildrenand the

variousschoolsocialsubsystems.

FOSTERING TEACHER-BASED SCHOOL VIOLENCE PREVENTION EFFORTS

TableI presentsa snapshotofhowecologicalconceptscanbe appliedtomentalhealth

consultationatthemicro-,meso-,exo-,and macrosystemlevelsinoverburdened violence-

riddenschoolsettings.As shown,theseconceptsguideconsultation in fourcriticalareas:

theinterpretationofpsychologicalknowledge,theassessmentoftheschoolecology,the

development ofpotential

interventions, ofquestionsforfuture

andthegeneration research.

TableII delineatesand presentsexamplesofteacher-generated

violenceprevention inter-

ventionsbased in parton thisapproach.

Changeat theMesosystemLevel

Effecting

Home-School Interactions.

Researchdemonstrates thatthehome-schoolrelationship of

violentchildrenis typicallyweak (Garbarinoetal., 1992;Olweus,1991;Patterson, 1982;

Pattersonetal., 1991).Typically,outreacheffortson thepartofschoolpersonneltoward

theparents(or othercaretakers) ofthesechildrenis rareand negative(Olweus,1991).In

manycases,theseparentshave themselves experienced schoolfailureand othernegative

experiencesin schoolsettings.Manyhave also beenfoundtobe ineffective in controlling

violencewithintheirownhomesettings (Eron,Huesmann,& Zelli,1991;Patterson, 1982).

Nevertheless, teachersand principalscontinueto expectsuchparentsto disciplinetheir

childrenafterthelatterhave been involvedin violentepisodesat school.Subsequently,

theseparents'oftenintenseand mutualfeelingsof frustration createa cyclethatonly

increasesthenegativeattitudesand interactions betweenhomeand school.At thevery

minimum,the aggressivechildlearnsthathis or her school and parentsrarelyhave

positivecontact, ifanycontactat all.

Ecologicaltheorypredictsthatchildren'sawarenessofa weak mesosystem or lackof

communication betweensettings maycontribute to thefrequency oftheirinvolvement in

aggressiveactionsandepisodes(Bronfenbrenner, 1979;Goldstein& Huff,1993).Therefore,

mentalhealthconsultation withteachersshouldfocuson ways to help teacherschange

the negativeperceptionsexistingwithinthe home and school.They shouldbeginby

sharingwithteachersfindings gleanedfromresearchinthisarea.Consulteeswhobecome

aware of thisresearchoftenattemptto createa positiverelationship betweenthetwo.

Theyfrequently becomeless angryat theparentsand morewillingto contactthehomes

ofviolentchildren aftertheyencounter researchsuggesting thatparentsareusuallyunable

to controlthechild'saggressionat home.Thisinformation helpslay thefoundation for

a potentialallianceand sharedset of goals betweenteachersand parents,the school

and thehome.Consultantscan thenlead teacherstowarddesigningor implementing

interventionsthatattempt toportray schoolsas supportive settings

forparentsoftroubled

childrenratherthanpunitiveor blamingones.In theformer, teachersand otherschool

personnelacknowledgeand sharethedifficult taskofhandlingaggressivechildren while

emphasizingand strengthening theparents'capacityto raisethosechildrencorrectly.

Community-School andPeerGroup-School Interactions.Patterson's

(1982;Patterson etal.,

1991)researchstronglysupportsthe notionthataggressivechildrenneed to be more

comprehensively monitored andsupervised byadultsthanotherchildren. Ampleevidence

supportsthenotionthatpeersocialization beforeandafterschoolandduringtheweekends

346 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLEI

OrientedDimensions

Ecologically forConsideration

inMentalHealthConsultation

withTeachers

on ViolencePrevention,

bySystemLevels

ROLE SYSTEM LEVEL RECOMMENDED APPROACHES

Interpretation Micro- Providerelevant information and research on possibledynamics in

ofSocialand theschoolsetting (e.g.,peergroupdynamics, schoolclimate,

Psychological teacher-child interactions, teachersupport systems, teacherburnout

Knowledge prevention, schoolpolicy,etc.)through teacherin-service training,

groupconsultations, or on a case-by-case basis.

Meso- Shareresearch findings on effective home-schoolinteractions (e.g.,

school-based programs, parentalinvolvement activities);

familiarize

teacherswithschemataoutlining thedomainsofthehome,

community, and school;provideinformation aboutspecific

community resources availableto theschool.

Exo- Heighten teachers'awarenessofexosystems through data,research,

and school-based examples;helpthemto integrate knowledge

aboutlackofmesosystem supports intoan awarenessofthearrayof

forcesaffecting theproblemofschoolviolence.

Macro- Describemacrosystem interactions (interpersonal and intergroup)

withtheexo-,meso-,and microsystems usingresearch on the

impactofracism,poverty, community violence,and lackofmaterial

resources on education;discusshowsocialdefinitions ofviolence

affectsschools'responses to violence.

Assessmentof Micro- Assessthedynamics withinand betweenvariousschoolsubgroups

theSchool (e.g.,teachers;administrators; secretarialstaff;

pupilpersonnel

Ecology professionals; maintenance staff;transportation workers; classroom,

schoolyard, and lunchroom assistants;and schoolmonitors); explore

theeffectiveness ofnatural support systems withinand betweenthe

differentsubgroups; assessteachers'understanding oftheirschools'

vision,purpose,procedures, and informal powerhierarchies; assess

thenumber and quantity ofothermicrosystems.

Meso- Assesstherelationship betweentheschooland othermicrosystems

suchas local agencies,peergroups,home,religious organizations,

youthgroups,and recreation facilities.

Exo- Assesstheextent to whichexosystem forcesaffect thehomeand

schoolenvironment; determine howtheeducationalsystem

accommodates to meettheneedsofparents whoare under-or

unemployed or singleparents; determine theextent oforganized

criminal activities (e.g.,gangs)intheschoolcommunity; assessthe

impactofdistrict and statelevelpolicieson teachersalaries,per-

pupilspending, schoolfunctioning, dropouts, homevisits,

absenteeism, etc.;determine thelevelofcontinuing education

trainingavailableforteachers.

Macro- Assesstheimpactofracism,poverty, religion,and local and state

politicson theschool;discussthefunction and roleoftheschoolin

thecommunity setting; assesspresent schoolactivities withina

historicaltimeframe.

TheJournalofNegroEducation 347

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLEI (continued)

EcologicallyOrientedDimensionsforConsiderationin Mental Health ConsultationwithTeachers

on Violence Prevention,by SystemLevels

ROLE SYSTEM LEVEL RECOMMENDED APPROACHES

Assistance

in Micro- Encourage teachers to use thestrengths ofschoolsubsystems as

Intervention supports; explorewithteachersthedomainofvariousprofessionals

Planning within theschooland discusshowtheymight worktogether to

addresstheproblem;ifconcernsaresharedbymanyconsultees,

encouragegroupconsultations to developa moresystemic solution

and reduceisolation; encourageteachersto thinkoftheschoolas a

sociodevelopmental entityakinto thefamily; clarifywithin-school

policyand procedures.

Meso- Exploreand/or strengthen a rangeofmesosystem interventions (e.g.,

family celebrations, homevisits,student presentations, frequent

telephonecontacts, home-schoolcommunications methods, use of

theschoolforadulteducationactivities, creationofan activePTA).

Exo- Attend schoolboardmeetings; writeletters to districtlevel

administrators;becomeawareoftheeffect oflocal industry,

factories,and employment strainson children's families; workwith

law enforcement, library system,and socialagenciesto provide

supports forfamilies or neighborhoods.

Macro- Use mediasourcesto expandpublicawarenessaboutchronicand

pervasive issuesrelatedto schoolviolence.Advocateforsupportive

statelawsor educationalcodes. Have theschoolbecomeawareof

theimpactofethnicity, race,religionand poverty and develop

teacher-initiatedcurricula or programs thatintegrate theseissues.

Helpconsulteesinterpret and understand socialand politicalforces

affectingthem.

Helping Micro- Collectdataon theeffect ofpoorlyequippedclassrooms and

Teachers deterioratingbuildings on teachers'and children's mentalhealth,

Conduct and on children's academicachievement; determine children's

TheirOwn understanding ofviolenceand schooldynamics; exploretheeffects

Researchon ofteachersupport systems on student performance; determine how

theSchool andto whatextent teachersare affected byschoolpolicyor school

Ecology organization.

Meso- Evaluatetheeffectiveness ofhome-schoolinterventions (e.g.,home

visitsortelephonecalls,family celebrations in school,school

performances); collectdataon theeffects of

community-school-teacher interventions on schoolattendance,

dropout, and academicachievement.

Exo- Evaluatedistrict-level supportsto theclassroom, continuing

educationclassesforteachers, and teacherinvolvement indistrict-

levelpolicymaking; determine effectsofexosystem pressures (e.g.,

theshutdown ofor massivelay-offs at localfactories) on children's

behavioral and schoolperformance; determine effects ofper-pupil

spending levelson thementalhealthofteachersand students.

Macro- Assessteacher'sawarenessand integration ofmacrosystem issues

thateffectthemon an interpersonal basis;explorethepoliticaland

socialmeaning oftheschoolwithchildren, parents, teachers, and

community members; exploreresponsibility issueswithregardto

violenceprevention.

348 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE11

Consultation

Outcomes:SampleTeacher-Generated

Interventions

SYSTEM LEVEL TEACHER-GENERATED

INTERVENTIONS

MICROSYSTEM Developconflict management programs targeting children,teachers, staff,

aides,

bus drivers, cafeteria workers, parents,and volunteers

Developclearand detailedschoolprocedures and policyon howstudents,

teachers, parents, shouldrespondto perpetrators and victims ofaggression

Raisethesocialstatusand prosocialbehaviorofaggressive children within the

peergroupbyinvolving themas visibleleadersin peertutoring orschool

beautification programs; instudent-organized violenceprevention dramatic or

artprograms; oras principal orteacherassistants, yardor assembly monitors,

trafficguards, or iunchroom assistants.

Increasethenumber ofadultmonitors during classroom transitionperiodsand in

high-risk schoollocations

Provideviolenceprevention trainingforhalland yardmonitors and forbus

drivers

Developsystems ofmonitoring childrenbeforeand after schooland betweenthe

schooland homesettings

Assignteachersas mentors and buddiesto students throughout theirschoolyears

MESOSYSTEM Institute frequent andfriendly visitsbyteachersand principals to thehomesof

all students

Establish frequent positivephonecontactswithparents to relaynewsofstudent

progress and oftheschool'svisionforchildren's academicand socialfutures

Initiateschoolwideorclassroom family-oriented celebrations(e.g.,sciencefairs,

performances, dinners, picnics)whereteachersand parents can interact

informally

Recruit volunteers fromand linkchildren up withneighborhood religious

organizations, sportsprograms, and youthgroups

Compilea resource bookforteachers, parents,and students oflocal support

organizations and services

Establish a formal linkagebetweentheschooland relevant socialserviceand

othersupport organizations and institutions

(e.g.,policeyouthdivisions, child

protective services, local newspaper reporters)

Petition and playa keyroleintheestablishment ofmoremicrosystems suchas

parks,recreational centers,libraries,transportationservices,etc.

EXOSYSTEM Participate inschoolboardmeetings focusingon district-levelschoolviolence

policy

Workwiththecitycouncilto blockoffthestreets aroundcertainschoolsduring

schoolhoursto reduceoreliminate drugtraffic,drive-by violence,and gang

activityand to improve playground safety

Workwithlocal employers to promote theprovision ofacademicandfamily

mentalhealthservicesforchildren whoseparents havebeen laidoffor are

unemployed

Workwithlocal agenciesororganizations to establishHead Start, infant/toddler,

or parenting programs

Establish jointschool-neighborhood programs to walkchildren to and from

school

TheJournalofNegroEducation 349

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE11(continued)

Interventions

ConsultationOutcomes: Sample Teacher-Generated

SYSTEM LEVEL TEACHER-GENERATED

INTERVENTIONS

MACROSYSTEM Encourage parents and caretakersto reducethenumber ofhourschildren spend

watching television,particularlyviolentshows

Workwithlocaltelevision stationsto improve ofviolentactivities

theirreporting

inthesurrounding community and to increasetheirreporting

ofschoolor

community successes

Addresschildren's concernsaboutpoverty or racismand theconnection ofthese

issuesto community and schoolviolence

Help children cope withtheviolencetheyhavewitnessed ina variety

ofsettings

Collectdataon district suspensions and expulsion forviolentbehaviorinschools

and present itto statelegislators

Monitor students' schoolprogress, particularlyduringperiodsofdevelopmental

transition

Redefine theclassroomand schoolas democratic entities

thatembody

democratic procedures, rules,and decisionmaking processes

Advocatefora definition ofschoolviolencethatis consistent withresearch

findings

can affecta child's tendency to engage in violent activities at school and elsewhere (Astor,

1995; Goldstein, 1994; D. C. Gottfredson, 1995; G. D. Gottfredson, 1985). Many highly

aggressive children have been found to receive peer enculturation in unmonitored groups

such as gangs or street groups in their neighborhoods (Dryfoos, 1990; Eron et al., 1994;

Garbarino et al., 1992; Goldstein & Huff, 1993). As mentioned earlier, these children often

have few positive microsystems (e.g., home, school, neighborhood). Therefore, increasing

the number of adult-supervised microsystems in such children's lives, and encouraging

stronger linkages between these subsystems and the school, should be a key theme in

teacher-based violence prevention consultation. The goal of this structured involvement,

which can include membership in sports teams, clubs, the arts, or other peer-oriented

activities, is to reduce the amount of time children spend with violent and unsupervised

peers. Another teacher-based mesosystem strategy is the recruitmentof model individuals

from the communities of troubled youth to work with teachers in the classroom and in

implementing other school and extracurricular activities.

Effecting Change at the Exosystem Level

Interventions at the exosystem level are not widely described or mentioned in the

research literature. However, many school districts have developed and implemented

policies regarding suspension and expulsion that directly relate to incidents of youth and

school violence (National Education Goals Panel, 1994a, 1994b, 1995, 1996). These policies

include those that mandate the creation of crisis intervention plans and formal guidelines

for teacher involvement with violent students. However, districts can add significantly

to order or chaos in schools distressed by violence by increasing the allotment of trained

as opposed to novice teachers at these schools and taking steps to reduce their teacher

turnover rates. Districts can also provide funds for school beautification projects and

350 The Journalof Negro Education

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

providesupportand rewardsforteacherswho developand initiateinnovative

programs

thatincreasetheirschools'readinessto addressviolence.

Effecting

Changeat theMacrosystem

Level

Using the ecologicalsystemsframework, manyof the teacher-consultees we have

workedwithhave attempted macrosystem-level interventions.

Some have woventheir

students'experiences withor againstviolenceintotheschools'history, art,drama,and

Othershaveorganizedpoliticalprotests,

socialstudiescurricula. vigils,school-community

ritualsofmourning, oryouthgroupsdenouncingviolence.Mostcontendthatsuchmea-

suresare veryeffective in givingchildrenin distressedenvironments a senseofcontrol,

expression,and self-worth as well as a way to understandand expressappropriate pain

and angertowardsocietyfornotstoppingthesenselessviolencein theirlives.Teachers

andprincipals alikehaveobservedthattheseinterventions maybe morehelpfultochildren

thantherapy groupsorindividualtherapy becausetheyareschoolwide, lessstigmatizing,

and do notfocusthepathologyofviolenceupon children.

Is youthand schoolviolencepartof a largersocietalpatternthatcan be sortedout

and understoodon thesocietallevel?Prominent socialscientists

(Donnerstein, Slaby,&

Eron,1994)andtheAmerican Psychological Association (1993b)havetakenstrong political

positionson thelevelsand typesofaggressive, violentbehaviorportrayed in themedia.

Yet,manyresearchstudieshave suggestedthatthemassmedia-particularly television,

motionpictures, popularmusic,and printjournalism-influence theoverallincidenceof

youthviolence.Researchon televisionand violencealso suggeststhatwhencompared

to theirpeers,aggressivechildrenspendmanymorehoursper day watchingtelevision,

and theywatchmoreviolentprograms(Eron,1987).Indeed,theaveragechildspends

moretimewatchingtelevision thanattending school.Thistimespentwatchingtelevision

is also timenot spentplayingwithfriends,doinghomework,or interacting in other

microsystems. Whenprovidedwithinformation on thenatureand extentof children's

televisionviewing,manyteachersand principalshave focusedon strategiesaimed at

reducingtheamountand typesoftelevisionchildrenare exposedto on a dailybasis.For

example,someteachers havesentnoteshometoalloftheparentsintheirclassesexplaining

theresearchon televisionexposure.Thesenoteshaveincludedsuggestions fortheamount

oftimechildren ofdifferentages shouldspendwatchingtelevision; theyalso recommend

showschildrenshouldwatch.

CONCLUSION

Mentalhealthconsultation servicesthatsupportteachersin developingmoreeffective

school-based responsestoyouthandschoolviolencearecritical toeffortsaimedatempow-

eringteachersand otherschool personnelin overburdenedsettings.To successfully

addresstheviolencechildrenand adultsexperienceand witnesswithinand outsideof

theschool,innovativeconsultation-collaboration modelsmustbe developedand imple-

mented.Theecologicalsystems approachtoteacher-based, mentalhealthviolencepreven-

tionconsultationis suchan approachbecauseithelpsteachersrealizeand maximizetheir

rolein enculturating,politicizing,

and guidingstudentsto understand and eliminatethe

aggressivebehaviortheywitnessor expresswithinthecontextofU.S. society.

An ecologicalsystemsapproachtoyouthand schoolviolenceconsultation withteach-

ersdemandsthatthementalhealthconsultant be awareofthecomplexities andpersuasive-

nessofviolencein oursociety.It also recognizestheimportance forconsultants

tounder-

standthatalthoughsome violenceintervention can be gearedtowardyouth

initiatives

in general,othersshouldbe directedtowardtheecologicaldynamicsthatmakeminority

TheJournalofNegroEducation 351

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

youthin high-density, low-incomeurbanenvironments morevulnerableto or inclined

towardviolence.Thatconsultants gainspecificknowledgeaboutnationaltrendsin youth

and schoolviolenceis criticalinthisregard.Suchknowledgeframesthemeaningofyouth

and youthand schoolviolenceinbroadterms.However,demographic dataalonedo not

help schoolpersonnelunderstandtherelationship of different ecologicalenvironments

totheincidence orprevalence ofviolenceamongcertain youth.Consultants shouldsystem-

aticallyexplorewiththeirteacher-consultees thereasonswhyteachersbelieveviolence

occursin theirschools,whentheybelieveviolenceis likely,and how thesetimesand

spaces interactwiththe prescribedsocial structure of the school (e.g., teacherroles,

administrator roles,etc.).Becauseyouthand schoolviolenceis so specificwithregardto

location,an examination ofteachers'and students'perceptions ofthecombinedphysical

and social structure of the school as it relatesto violencemay be important forthe

generation ofeffectiveinterventions in a givenschool.

REFERENCES

AmericanPsychological Association.(1993a).Guidelinesforprovidersofpsychological ser-

vicesto ethnic,linguistic, and culturallydiversepopulations.American 48,45-48.

Psychologist,

American Psychological Association. (1993b).Violenceandyouth: Psychology'sresponse(Vol.1).

Washington DC: Author.

Ash,P., Kellermann, A., Fuqua-Whitley, D., & Johnson, A. (1996).Gun acquisitionand use

byjuvenileoffenders. JournaloftheAmerican MedicalAssociation,275,1754-1758.

Astor,R. A. (1995).Schoolviolence:A blueprint forelementary schoolinterventions. Social

Workin Education, 17,65-128.

Astor,R.,Behre,W.,Fravil,K.,& Wallace,J.(1997).Perceptions ofschoolviolenceas a problem

and reportsofviolentevents:A nationalsurveyofschoolsocialworkers.SocialWork, 42,55-68.

Astor,R. A., Meyer,H., & Behre,W.J.(1997).Usingmapsandfocusgroupstodevelop school-

basedinterventions:An assessment Paperpresentedat theannualmeetingoftheAmerican

process.

EducationalResearchAssociation, Chicago,IL.

Behrman, R. E. (1992).Introduction. TheFutureofChildren: School-LinkedServices,2(1),32-43.

Beynon, J.,& Delamont, S. (1984).Thesoundandthefury: Pupilperceptions ofschoolviolence.

In N. Frude,& H. Gault(Eds.),Disruptive behaviour inschools (pp. 137-151).New York:JohnWiley

& Sons.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977).Towardand experimental ecologyofhumandevelopment. Ameri-

canPsychologist,32,513-531.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979).Theecology ofhuman development.Cambridge, MA: HarvardUniver-

sityPress.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1980).Ecologyofchildhood.SchoolPsychology Review, 9, 294-297.

Burchard, J.(1990,April).Themainstream revisited:Theneedforcommunity-based wraparound

servicesforchildren withsevereemotional disturbance. Paper presentedat the 24thannual School

Psychology Conference, University ofCalifornia-Berkeley, Berkeley, CA.

Cairns,R. B., & Cairns,B. D. (1991).Socialcognition and socialnetworks: A developmental

perspective.In D. J.Pepler& K. H. Rubin(Eds.),Thedevelopment andtreatment ofchildhood aggression

(pp.249-278).Hillsdale,NJ:Erlbaum.

Caplan,G., & Caplan,R. B. (1993).Mentalhealth consultationandcollaboration.San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass.

CamegieCouncilon AdolescentDevelopment.(1993).A matter oftime:Riskandopportunity

in nonschoolhours.New York:Author.

CentersforDisease Controland Prevention. (1996).Youthriskbehaviors United

surveillance:

States,1995(No. SS-4).Atlanta,GA: Author.

Christoffel,K. (1990).Violentdeathand injuryin U.S. childrenand adolescents.American

JournalofDiseasesofChildhood, 144,697-706.

352 ofNegroEducation

TheJournal

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Coie, J.D., Underwood, M., & Lochman,J.E. (1991). Programmaticintervention with aggres-

sive childrenin the school setting.In D. J.Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Thedevelopment

and treatment

ofchildhood aggression(pp. 389-407). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Conoley,J.C., & Gutkin,T. (1986). School psychology:A reconceptualizationof servicedeliv-

eryrealities.In S. Elliot& J.Witt(Eds.), Thedelivery

ofpsychological in schools:Concepts,

services

processesand issues (pp. 393-424). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Dodge, K. A. (1980). Social cognition and children's aggressive behavior. Child

Development,

51, 162-172.

Dodge, K. A. (1985). Attributional

bias in aggressivechildren.In P. C. Kendall (Ed.), Advances

in cognitive

behavioral

research

andtherapy: 4. New York:AcademicPress.

Volume

Dodge, K. A. (1986). A social informationprocessingmodel of social competencein children.

In M. Perlmutter(Ed.), Minnesotasymposium in childpsychology

(pp. 77-125). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Dodge, K. A., Pettit,G. S., McClaskey,C. L., & Brown,M. M. (1986). Social competence in

children(SerialNo. 213).Monographs forResearch

oftheSociety in ChildDevelopment,

51,2.

Dohm, B. (1995). Undemonizing our children.EducationDigest,61, 4-6.

Donnerstein,E., Slaby, R. G., & Eron,L. (1994). The mass media and youth aggression. In

& P. Schlegel(Eds.),Reasontohope:A psychosocial

L. D. Eron,J.H. Gentry, onviolence

perspective and

youth(pp. 219-250). Washington,DC: AmericanPsychologicalAssociation.

at risk:Prevalence

Dryfoos,J.(1990).Adolescents andprevention.

New York:OxfordUniver-

sityPress.

Duncan, B. B., & Burns,S. (1994). A comprehensivecommunity-basedcontinuumof care:

Overall findingsfromthe Butte-VenturaSED Research Project.In C. R. Ellis & N. N. Singh (Eds.),

andadolescents

Children withemotional

orbehavioral

disorders:

Proceedings

ofthefourth

annualVirginia

Beachconference (p. 55). Richmond,VA: CommonwealthInstituteforChild and AdolescentStudies,

Medical College of Virginia,VirginiaCommonwealthUniversity.

Elam, S. M., Rose, L. C., & Gallup, A. M. (1994,September).The 26thannual Phi Delta Kappan/

Gallup Poll of the public's attitudestoward the public schools. Phi Delta Kappan,41-56.

Eron,L. D. (1987).Aggression through [Special issue onbullies]. Malibu, CA:

theages:Schoolsafety

National School SafetyCenter,Pepperdine University.

Eron, L. D., Gentry,J.H., Schlegel,P. (Eds.). (1994). Reasontohope:A psychosocial perspective

on violenceand youth.Washington,DC: AmericanPsychologicalAssociation.

Eron, L. D., Huesmann, R., & Zelli, A. (1991). The role of parental factorsin the learningof

In D. J.Pepler& K. H. Rubin(Eds.),Thedevelopment

aggression. andtreatment

ofchildhood

aggression

(pp. 169-186). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Furlong, M. J.,Babinski, L., Poland, S., & Munioz,J. (1996). School psychologistsrespond

to school violence: A national survey of currentpractice and trainingneeds. Psychologyin the

33,28-37.

Schools,

J.(1982).Children

Garbarino, andfamiliesin thesocialenvironment.

New York:Aldine.

J.,Dubrow,N., & Pardo,C. (1992).Children

Garbarino, indanger:

Copingwiththeconsequences

ofcommunity violence.San Francisco:Jossey-Bass.

Goldstein,A. (1994). Theecologyofaggression.New York: Plenum.

Goldstein,A. P., & Huff,R. C. (Eds.). (1993). Thegang intervention

handbook.Champaign,IL:

Research Press.

Gottfredson, D. C. (1995,December). Creatingsafe,disciplined, schools.Paper prepared

drug-free

forthe conference,"ImplementingRecentFederal Legislation," sponsored by the Officeof Educa-

tional Research and Improvement,U.S. Departmentof Education, and the American Sociological

Association,St. Petersburg,FL.

Gottfredson,G. D. (1985). Victimizationin schools.New York: Plenum.

Gray,D. (1991).TheplightoftheAfrican

American

male:An executive ofa legislative

summary

hearing.Detroit,MI: Council PresidentPro Tem Gil, the DetroitCityCouncil Youth AdvisoryCom-

mission.

Guerra, N., & Slaby, R. (1989). Evaluative factorsin social problem solving by aggressive

boys.Journal

ofAbnormal

ChildPsychology,

17,277-289.

Hammond, R., & Yung, B. (1993). Psychology'srole in thepublic healthresponseto assaultive

violence among young African-American men. AmericanPsychologist, 48, 142-154.

TheJournalofNegroEducation 353

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Hammond, R. W., & Yung, B. R. (1994). AfricanAmericans. In L. D. Eron, J.H. Gentry,&

P. Schlegel(Eds.),A reasonto hope:A psychosocial on violence

perspective and youth(pp. 105-118).

Washington,DC: AmericanPsychologicalAssociation.

Harlow, C. (1989). Injuriesfromcrime(Bureau of JusticeStatistics,Special ReportsNo. NCJ-

116811).Washington,DC: U.S. Departmentof Justice.

Hausman, J.,Spivak, H., & Prothrow-Stith, D. (1994). Adolescents' knowledge and attitudes

about and experiencewith violence. JournalofAdolescentHealth,15, 400-406.

Hobbs, N. (1966). Helping disturbedchildren:Psychologicaland ecological strategies.Ameri-

canPsychologist,

21, 1105-1115.

Isaacs,M. (1992).Violence:

Theimpactofcommunity violence

on African

American

children

and

families:

Collaborative to prevention

approaches and intervention. VA: NationalCenterfor

Arlington,

Education in Maternal and Child Health.

Jessor,R. (1993). Successfuladolescentdevelopmentamong youthin highrisksettings.Ameri-

canPsychologist,

48,117-126.

Kachur P., Stennies,G., Powell, K., Modzeleski, W., Stephens,R., Murphy,R., Kresnow,M.,

Sleet,D., & Lowry,R. (1996). School-associated violent deaths in the United States, 1992 to 1994.

oftheAmerican

Journal 275,1729-1733.

MedicalAssociation,

Kantor,H., & Brenzel,B. (1992). Urban education and the'trulydisadvantaged': The historical

roots of the contemporarycrisis,1945-1990. TeachersCollegeRecord,94, 278-314.

Kozol,J.(1991).Savageinequalities:

Children schools.

inAmerica's New York:HarperPerennial.

Lancelotta,G., & Vaughn, S. (1989). Relation between types of aggression and sociometric

status:Peer and teacherperceptions.JournalofEducationalPsychology, 81, 86-90.

Lee, V. E., & Croninger,R. G. (1995). Thesocialorganization

ofsafehighschools.Paper presented

at theGoals 2000,Reauthorizationof the Elementaryand SecondaryEducation Act,and the School-

to-WorkOpportunitiesAct Conference,Palm Beach, FL.

Lewin, K. (1935). Dynamictheory ofpersonality.New York: McGraw-Hill.

Lewin, K. (1951). Psychologicalecology. In D. Cartwright(Ed.), Field theoryin social science:

SelectedtheoreticalpapersbyKurtLewin(pp. 170-187). New York: Harper & Row.

MetropolitanLife Insurance Company & Harris Poll. (1993). The Metropolitan Lifesurveyof

theAmericanteacher,1993. New York, NY: Author.

MetropolitanLife Insurance Company & Harris Poll. (1994). The Metropolitan Lifesurveyof

theAmericanteacher,1994. New York,NY: Author.

MetropolitanLife Insurance Company & Harris Poll. (1995). The Metropolitan Lifesurveyof

theAmericanteacher, 1995. New York,NY: Author.

Morrill,W. A. (1992). Overview of servicedeliveryto children.TheFutureofChildren:School-

Linked

Services,

2 (1), 32-43.

National CenterforEducation Statistics.(1991). Publicschoolteachersurveyon safe,disciplined,

and drug-freeschools.Washington,DC: U.S. Departmentof Education.

National CenterforHealth Statistics.(1992). [Unpublisheddata tablesfromtheNCHS mortal-

itytapes.] Atlanta,GA: CentersforDisease Control.

National Education Goals Panel. (1994a). The nationaleducationgoals report(Vols. I & II).

Washington,DC: U.S. GovernmentPrintingOffice.

National Education Goals Panel. (1994b). Proceedingsof theNational EducationGoals Panell

National

Alliance

ofPupilService

Organizations' safestudents

safeschools, conference.

ChapelHill,NC:

Educational Resources Clearing House.

National Education Goals Panel. (1995). The national educationgoals report(Vols. I & II).

Washington,DC: U.S. GovernmentPrintingOffice.

National Education Goals Panel. (1996). The nationaleducationgoals report(Vols. I & II).

Washington,DC: U.S. GovernmentPrintingOffice.

National Instituteof Education & U.S. Departmentof Health, Education and Welfare.(1978).

Violentschools-Safeschools:Thesafeschoolstudyreportto Congress(No. 1). Washington,DC:

U.S. GovernmentPrintingOffice.

Olweus, D. (1991). Bully/victimproblems among schoolchildren:Basic factsand effectsof a

school-basedintervention program.In D. J.Pepler & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Thedevelopment

andtreatment

ofchildhoodaggression(pp. 411-448). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

354 TheJournal

ofNegroEducation

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Patterson,G. R. (1982). A social learningapproachtofamilyintervention.

Eugene, OR: Casitilia

Publishing.

Patterson,G. R., Capaldi, D., & Bank,L. (1991). An early startermodel forpredictingdelin-

quency.In D. J.Pepler& K. H. Rubin(Eds.), Thedevelopment

and treatment

ofchildhood

aggression

(pp. 139-168). Hillsdale, NJ:Erlbaum.

Pearl,D. (1986). Familial,peer and televisioninfluenceson aggressiveand violentbehavior.In

D. H. Crowell, I. M. Evens, & C. R. O'Donnell (Eds.), Childhoodaggression

and violence(pp. 231-247).

New York: Plenum.

Prothrow-Stith,D., & Weissman, M. (1991). Deadlyconsequences. New York: Harper Collins.

Sameroff,A. J.,& Fiese, B. H. (1990). Transactionalregulation and early intervention.In

S. J.Meisels & J.P. Shonkoff(Eds.), Handbook ofearlychildhood education.

Cambridge: Cambridge

UniversityPress.

Sameroff,A., Seifer,R., Barocas, R., Zax, M., & Greenspan,S. (1987). Intelligencequotient

scores of 4-year-oldchildren:Social-environmentalrisk factors.Pediatrics, 79, 343-350.

D. (1995).Department

Satcher, HealthandHumanServices,

ofLabor, andrelated

Education, agencies

1996 (Part3) [Hearingbeforea subcommitteeof theCommitteeon Appropriations,

appropriationsfor

U.S. House of Representatives].Washington,DC: U.S. GovernmentPrintingOffice.

Sautter,C. (1995). Standingup to violence. Phi Delta Kappan,76, K1-K12.

Schorr,L. (1988). Withinour reach:Breakingthecycleofdisadvantage. New York: Doubleday.

Shakoor, B., & Chalmers, D. (1991). Co-victimizationof AfricanAmerican children who

witnessviolence:Effectson cognitive,emotional,and behavioraldevelopment.Journal oftheNational

83,233-238.

MedicalAssociation,

Slaby,R. G.,Barham,J.,Eron,L. D., & Wilcox,B. L. (1994).Policyrecommendations:Prevention

and treatmentof youth violence. In L. D. Eron,J.H. Gentry,& P. Schlegel (Eds.), Reasonto hope:A

psychosocial

perspective on violenceandyouth(pp. 447-456). Washington,DC: AmericanPsychological

Association.

Stroul,B. A., & Friedman,R. M. (1986). A systemofcareforseriouslyemotionally

disturbed

children

and youth.Washington,DC: Child and Adolescent Service System Program Technical Assistance

Center at GeorgetownUniversity.

Younger, A. J., & Piccinin, A. M. (1989). Children's recall of aggressive and withdrawn

behaviors: Recognitionmemoryand likabilityjudgments.ChildDevelopment, 60, 580-590.

TheJournal

ofNegroEducation 355

This content downloaded from 132.174.255.3 on Sun, 22 Sep 2013 00:16:04 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

View publication stats

You might also like

- School Ict Accomplishment ReportDocument2 pagesSchool Ict Accomplishment ReportMarites Del Valle Villaroman100% (16)

- Receipt of Lab Report Submission (To Be Kept by Student)Document4 pagesReceipt of Lab Report Submission (To Be Kept by Student)Dylan YongNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Bullying AbstractDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About Bullying Abstractscongnvhf100% (1)

- Research Paper About Bullying IntroductionDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About Bullying Introductiongvzph2vh100% (1)

- Group Research PaperDocument9 pagesGroup Research PaperLei Andrew PatunganNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 4 No. 5 May 2016Document14 pagesInternational Journal of Education and Research Vol. 4 No. 5 May 2016karimNo ratings yet

- Awareness and Prevention of Bullying Among Students of GGNHSDocument35 pagesAwareness and Prevention of Bullying Among Students of GGNHSGil Bert100% (1)

- Introduction For A Research Paper On BullyingDocument4 pagesIntroduction For A Research Paper On Bullyingxvrdskrif100% (1)