Professional Documents

Culture Documents

End Useracceptanceofacloud Basedteledentistrysystem

Uploaded by

Dannilo CerqueiraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

End Useracceptanceofacloud Basedteledentistrysystem

Uploaded by

Dannilo CerqueiraCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/288904159

End-user acceptance of a cloud-based teledentistry system and Android

phone app for remote screening for oral diseases

Article in Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare · January 2017

DOI: 10.1177/1357633X15621847

CITATIONS READS

40 3,185

7 authors, including:

Mohamed Estai Di Xiao

University of Western Australia The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation

41 PUBLICATIONS 1,178 CITATIONS 30 PUBLICATIONS 628 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Janardhan Vignarajan Stuart M Bunt

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation University of Western Australia

15 PUBLICATIONS 368 CITATIONS 33 PUBLICATIONS 1,727 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Forensic dentistry Dental age estimation in adults View project

Retinal Image Analysis View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Mohamed Estai on 13 October 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

J Telemed Telecare OnlineFirst, published on December 30, 2015 as doi:10.1177/1357633X15621847

RESEARCH/Original Article

Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare

0(0) 1–9

End-user acceptance of a cloud-based ! The Author(s) 2015

Reprints and permissions:

teledentistry system and Android phone sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1357633X15621847

app for remote screening for oral diseases jtt.sagepub.com

Mohamed Estai1, Yogesan Kanagasingam2, Di Xiao2,

Janardhan Vignarajan2, Stuart Bunt1, Estie Kruger1

and Marc Tennant1

Abstract

Objective: This study aimed to evaluate users’ acceptance of a teledentistry model utilizing a smartphone camera used for

dental caries screening and to identify a number of areas for improvement of the system.

Methods: A store-and-forward telemedicine platform ‘‘Remote-I’’ was developed to assist in the screening of oral diseases

using an image acquisition Android app operated by 17 teledental assistants. A total of 485 images (five images per case) were

directly transmitted from the Android app to the server. A panel of five dental practitioners (graders) assessed the images and

reported their diagnosis. A user acceptance survey was sent to the graders and smartphone users following completion of the

screening program.

Results: Of the 22 surveys sent out, 20 (91%) were completed. Generally, users showed optimism towards the use of the

teledentistry system, and strongly positively assessed items on content and service quality. The majority of graders took less

than 15 min to read the images while phone users took 5–10 min to complete the dental photography using the Android app.

This study identified a number of factors that are essential for improving the current system, such as optimization of smart-

phone camera features, the format of the server, and the orientation of images and using oral retractors during photography.

Conclusions: Users appear to be generally satisfied with the proposed teledentistry model. However, they have specific

concerns to address, many of which could be resolved through more effective training, coordination between sites and

upgrading the current system.

Keywords

Attitude, dentist, dental screening, store-and-forward, smartphone, telemedicine

Date received: 8 September 2015; Date accepted: 19 November 2015

Introduction There are many methods for screening for oral diseases.

Teledentistry, as a subspecialty of telemedicine, can be However, the most common method is the face-to-face

defined as ‘‘the provision of real-time and off-line dental examination. The rapid advances in digital imaging and

care such as diagnosis, treatment planning, consulting and other technologies have provided practitioners with alterna-

follow up via electronic transmission from different tives to traditional settings.9 Assessment of intra-oral photo-

sites.’’1 (p. 399) For several decades, telemedicine has graphs can maintain a good level of sensitivity and

played a role in bridging gaps and overcoming barriers specificity of visual detection of caries.10 Dental photog-

through spreading healthcare to previously unreachable raphy can also be less stressful and intimidating for young

populations.2 Most teledentistry studies were at a small children than a conventional dental examination.9 With

scale and limited to short-term outcomes,3 utilizing now

superseded technologies or expensive peer-to-peer system 1

Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology, University of

approaches. Evidence indicates that teledentistry examin- Western Australia, Australia

ations are comparable to clinical examinations in screen- 2

Australian e-Health Research Centre, The Commonwealth Scientific and

ing for caries.4–6 However, none has demonstrated Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Australia

superior clinical results (i.e. validity, reliability, and effect-

iveness) compared to traditional settings. It is postulated Corresponding author:

Estie Kruger, International Research Collaborative, Oral Health and Equity,

that teledentistry offers a cost-effective means to help Department of Anatomy, Physiology and Human Biology (M309), University

reduce some obstacles to optimal oral health, particularly of Western Australia, 35 Stirling highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia.

for underserved populations.7,8 Email: estie.kruger@uwa.edu.au

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

2 Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 0(0)

smartphone camera technology improving significantly and distance. The images captured using the smartphone

widespread availability of the cellular networks, utilization were deleted from the phone immediately after transmis-

of smartphone cameras in dental imaging has grown.11–13 sion of the images to the Remote-I system to avoid any

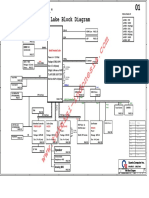

Derived from the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), privacy issues (Figure 1). The components of the teleden-

the technology acceptance model (TAM) aims to explain tistry system are summarized in Table 1.

user acceptance and to predict the adoption of technolo-

gies.14 TAM has been widely adopted in research, due to

its parsimonious nature and wealth of recent empirical

Participants (users)

support of its role in predicting the acceptance behaviour Graders (dental practitioners). Reviewing of dental images

of a technology.15,16 TAM posits that behavioral intention was carried out by five independent dental practitioners

is determined jointly by attitude and perceived usefulness, using a web-based data and image-viewing app built upon

the latter also affects attitude directly. Meanwhile, the the Remote-I system. Although graders did not receive

perceived ease of use directly influences both attitude any training on how to use the system, a simple user

and perceived usefulness.17 TAM works as an appropriate manual and cover letter were sent to graders explaining

framework for our survey as it gives attitude a key role in the purpose of the study and how to use the system. They

predicting the potential user’s behavioural intention to use were able to access the database using individual user

a technology; a role that has been shown to be fundamen- identities (IDs) and passwords. The system enabled gra-

tal in the acceptance of telemedicine.15,18 ders to review images and insert comments on the prede-

In response to the increasing demand for oral care ser- fined oral assessment form and submit reports or

vices, particularly in remote or rural regions, we have recommendations into the Remote-I server (Figure 2).

developed a store-and-forward telemedicine platform

called ‘‘Remote-I’’ and a novel image acquisition Teledental assistants (smartphone users). Patient recruitment

Android app that can be used for screening purposes.19 and dental photography were performed by 17 trained

The present study builds on an initial validation (proof- teledental assistants (dental students, dental assistants,

of-concept trial) study that tested the validity and reliabil- dental practitioners) using a smartphone camera. The tel-

ity of the teledentistry approach in the screening for dental edental assistants received hands-on training on how to

caries.19 The findings show that the proposed teledentistry capture good quality images using a smartphone camera.

model for dental screening using a smartphone camera Recruitment of patients and dental photography were

offers a valid and reliable alternative to visual dental completed in a series of locations; a small practice, hos-

examination.19 Since perceived usefulness and ease of pital, and large dental facility. Over six months, up to 100

use are critical factors in the acceptance of a technology, records were uploaded to the Remote-I server; these com-

we sought to evaluate users’ acceptance of the teledentis- prised 485 images (approximately five images per case)

try model and to identify the factors that contribute to the and anonymous patient demographic data.

improvement of the current system.

Questionnaire instrument

Methods The survey questions are based on a standard, validated,

and reliable instrument for end-user satisfaction modified

Teledentistry system for telemedicine.21,22 Our study has good content validity,

A telemedicine system, ‘‘Remote-I,’’ based on a store- as the survey items were vetted and revised by three dental

and-forward method, was developed by the Australian practitioners, and the questions reflected their concerns

E-Health Research Centre (AEHRC) to work as a plat- and areas of satisfaction. The survey comprised four sec-

form for data storage and management.20 Remote-I is tions. The first section included questions about the users’

capable of image acquisition, data entry, storage and demographic characteristics. The second section com-

retrieval of data. An image acquisition app was built prised of 11, five-point, Likert-type questionnaire (never/

and installed on a Motorola MotoG smartphone (USA) almost never ¼ 1; seldom ¼ 2; about half the time ¼ 3;

to facilitate entering patient details and capturing dental most of the time ¼ 4; always/almost always ¼ 5) used to

photos, and then uploading data corresponding to each assess the quality of the system which comprised five

patient to Remote-I, using Wi-Fi hotspots or cellular data dimensions; content, format, information quality (accur-

networks. After obtaining their informed consent, partici- acy), ease of use, service quality, and support. An add-

pants were enrolled in a trial to obtain oral images using itional two items were included to assess the usefulness

smartphone cameras. Each participant received an in- and overall satisfaction with applications. The third sec-

person oral examination by a dentist to record caries tion examined the average time that was spent to create a

and existing restorations, before trained teledental assist- record and complete photography using the Android app

ants took photographs from each participant’s oral cavity, and grade a record on the Remote-I server. The final sec-

using a Motorola smartphone camera. Records were then tion solicited free comments about whether users have

directly transmitted as encrypted data from the smart- suggestions to improve existing systems. Following com-

phone to the Remote-I for evaluation by a dentist at a pletion of the trial, the survey was distributed by e-mail

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

Estai et al. 3

Figure 1. Architecture of the teledentistry system.

Table 1. The components of the teledentistry system.

Items Description

Teledentistry system A telemedicine platform that utilizes store-and forward and smart phone technology to screen for oral diseases

at distance.

Remote-I server Cloud-based platform that enables data entry, storage, image acquisition, retrieval of large amount of data.

Android app An image acquisition app ‘‘Teledental’’ installed on a smartphone device that enables entering patient data, taking

dental images, and uploading a record to Remote-I using a 3G Internet or Wi-Fi connection.

Smartphone Motorola MotoG, Android – 5.0 Lollipop.

Camera360 Ultimate Third party Android camera app that is used for dental photography instead of the default Motorola camera app.

Teledental assistant Obtain consent from the patient, create records, and obtain dental photographs.

Grader Review and assess records stored in Remote-I.

with a cover letter stating the purpose of the survey. A majority of respondents (80%) were women. The respond-

reminder was sent to all users who did not respond to the ents’ professions were dentists (n ¼ 11; 55%), dental ther-

initial correspondence. The protocol for this study was apists (n ¼ 3; 15%), dental students (n ¼ 3; 15%) and

approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of nurses (n ¼ 3; 15%). All respondents confirmed that they

The University of Western Australia. used computers both at home and work, and reported

good typing proficiency.

Results

User acceptance of Remote-I system and

A total of 22 requests for completion of the survey were

sent to all users of either the smartphone (teledentistry

smartphone app

assistants) or Remote-I (graders) users. A total of 20 com- The overall level of satisfaction with both the Remote-I

pleted surveys were received (91% response rate); only server and Android app was positive. Generally, smart-

two smartphone users did not respond to the survey. phone users had strong positive assessments on items

The mean age of respondents was 34 years and the assessing content, format and service quality (system’s

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

4 Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 0(0)

Figure 2. Snapshot of Remote-I server illustrating the dental chart.

stability). The answers to ‘‘How often is the content pre-

Time taken for dental photography and grading

sented in the app sufficient and appropriate?,’’ ‘‘How

often does the content meet your needs?,’’ ‘‘How often The assessment time of records depended on the quality of

do you think the output is presented in a useful the images and the severity of the oral diseases, but most

format?,’’ and ‘‘How often is the information clear?’’ graders spent less than 15 min to assess each record on the

were given as ‘‘most of the time’’ or ‘‘always’’ by more Remote-I system. On the other hand, the majority of

than 87% of app users. The answer to ‘‘How often is the smartphone users took 5–10 min to create a record in

system subject to technical problems or crashes?’’ was the Android app and complete the dental photography

answered with ‘‘seldom’’ or ‘‘never’’ by 80% the users. for a patient (Table 4).

Remote-I users had strong positive assessments on

items assessing content, information quality and service

Users’ suggestions of ways to improve the system

quality (system’s stability). The answers to ‘‘How often

is the dental chart content appropriate for oral health Users were enthusiastic about the use of the teledentistry

assessment?’’ and ‘‘How often are you satisfied with the system for screening for caries based on photographic

accuracy of the system?’’ were given ‘‘most of the time’’ or assessments. The majority of smartphone users (67%) sug-

‘‘always/almost always’’ by 80% of respondents while the gested a number of areas for improvement; in particular in

item ‘‘How often is the system subject to technical the zoom and autofocus features of the smartphone

problems or crashes?’’ was answered with ‘‘seldom’’ or camera. Similar opinions were expressed by other users

‘‘never’’ by all users. Users were somewhat less positive (27%) who felt that the quality of some images was not

towards the Android app in terms of the information good due to lighting issues related to the inbuilt camera

quality (quality of taken images), the ease of use of flash (Figure 3). More than half of smartphone users

camera and training received. Graders were somewhat (53%) suggested using disposable retractors during pho-

less positive towards the Remote-I server in terms of the tography to help in obtaining clear images. Few users

format and ease of use. However, both graders and smart- (20%) suggested developing an app that can support

phone users sometimes had negative assessments about other operating systems such as iphone operating system

whether they get the assistance they need from the (iOS) and Windows, and also suggested making the app

research team (Table 2 and 3). available in the Google or Apple stores.

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

Estai et al. 5

Table 2. End-user acceptance survey of the Android smartphone app.

n (%)

Negative Positive

Items and subscale 1 2 3 4 5 (%) (%)

Content

1. How often is the content presented in the – – 1 (7%) 6 (40%) 8 (53%) – 93%

app sufficient and appropriate?

2. How often does the content meet your needs? – – 2 (13%) 8 (53.50%) 5 (33.50%) – 87%

Information quality (accuracy)

3. How often are you satisfied with the accuracy of the app? – 3 (20%) 2 (13%) 4 (27%) 6 (40%) 20% 67%

4. How often are the captured dental images clear? – 3 (20%) 3 (20%) 9 (60%) – 20% 60%

Format

5. How often do you think the output is – – 1 (7%) 8 (53%) 6 (40%) – 93%

presented in a useful format?

6. How often is the information clear? – – 2 (13%) 6 (40%) 7 (47%) – 87%

Ease of use

7. How often is the smart phone camera easy to use? – 3 (20%) 3 (20%) 9 (60%) – 20% 60%

8. How often is the app user-friendly? – – 4 (27%) 7 (46.50%) 4 (26.50%) – 73%

Service quality (system stability)

9. How often is the system subject to technical 5 (33%) 7 (47%) 1 (7%) 2 (13%) – 80% 13%

problems or crashes?

Support

10. How often do you get the assistance you need 1 (7%) 5 (33%) 5 (33%) 3 (20%) 1 (7%) 40% 27%

from the research team?

11. How often are you satisfied with training received? – 3 (20%) 3 (20%) 7 (47%) 2 (13%) 20% 60%

Additional items

12. Do you feel the app is useful? – – 4 (27%) 5 (33%) 6 (40%) – 73%

13. Overall, are you satisfied with the app? – 2 (13%) 3 (20%) 6 (40%) 4 (27%) 13% 67%

Never/almost never ¼ 1; seldom ¼ 2; about half the time ¼ 3; most of the time ¼ 4; always/almost always ¼ 5. The percentage of respondents reporting ‘‘most of

the time’’/’’great’’ and ‘‘always/almost always’’/’’very great’’ (Likert scales ‘‘4’’ and ‘‘5’’) within a given scale were charted as percent positive, while the percentage

reporting ‘‘never’’/’’not at all’’ and ‘‘seldom’’/’’very little’’ (Likert scales ‘‘1’’ and ‘‘2’’).

Despite their satisfaction with the content, most dental real-time and in-person models in some clinical discip-

graders asked for improvement of the format of the tele- lines.8,25,26 Historically, mobile devices suffered from a

dental system, in particular dental charting, as this would low storage space and low quality of imaging, and this

facilitate inserting comments and avoid making errors. could be a reason for underusing smartphones in dental

One grader suggested improving the orientation and label- photography. With recent significant improvements in

ing of saved images as some labeling was incorrect. Others smartphone camera technology, utilization of smart-

(two graders) suggested using oral retractors during pho- phones in dental photography and for screening purposes

tography for a better view of posterior teeth as some has grown.11–13 Even when a telemedicine system proves

images were difficult to read because some posterior to be useful, users also note room for improvement or

teeth (molars) were not clear or not shown (Table 5). offer suggestions. Collecting feedback on areas of satisfac-

tion, barriers, and suggestions from users about a tele-

medicine program can help foster better-designed

Discussion

programs that can be more successfully implemented.27

Overall, our survey showed that users perceived the store- Despite the majority of users believing that the

and-forward based teledentistry system positively as Remote-I system is accurate, stable, easy to use, and pre-

useful for screening purposes. This reflects previous sented in a useful format, our findings showed that per-

research which has shown excellent levels of acceptance ceived accuracy, format, and ease of use could be

of real-time based teledentistry system by both patients improved. A few concerns persist among respondents,

and professionals.23,24 Although, most teledentistry sys- including difficulty in reviewing posterior teeth because

tems utilize a real-time modality,3 the practices of asyn- the oral cavity was not retracted enough, system architec-

chronous or store-and-forward telemedicine have proven ture such as dental chart layout and design, and orienta-

to be more cost-effective and efficient compared to tion of images and labelling. Another matter affecting the

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

6 Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 0(0)

Table 3. End-user acceptance survey of the Remote-I server.

n (%)

Negative Positive

Items and subscale 1 2 3 4 5 (%) (%)

Content

1. How often is the dental chart content – – 1 (20%) 3 (60%) 1 (20%) 0 80%

appropriate for oral health assessment?

2. How often does the content meet your needs? – – 2 (40%) 3 (60%) – 0 60%

Information quality (accuracy)

3. How often are you satisfied with the – – 1 (20%) 2 (40%) 2 (40%) 0 80%

accuracy of the system?

4. How often are patients’ images clear? – 1 (20%) 1 (20%) 3 (60%) – 20% 60%

5. How often are teeth gradable? – – 2 (40%) 3 (60%) – – 60%

Format

6. How often do you think the output is – – 2 (40%) 3 (60%) – 0 60%

presented in a useful format?

7. How often is the information clear? – 1 (20%) 1 (20%) 3 (60%) – 20% 60%

Ease of use

8. How often is the system easy to use? – – 2 (40%) 2 (40%) 1 (20%) 0 60%

9. How often is the system user-friendly? – – 2(40%) 1 (20%) 2 (40%) 0 60%

Service quality (system stability)

10. How often is the system subject to technical 3 (60%) 2 (40%) – – – 100% 0

problems or crashes?

Support

11. How often do you get the assistance you need – 2 (40%) 2 (40%) 1 (20%) – 40% 20%

from the research team?

Additional items

12. Do you feel Remote-I is useful? – – 1 (20%) 2 (40%) 2 (40%) – 80%

13. Overall, are you satisfied with the server? – 1 (20%) 1 (20%) 3 (60%) – 20% 60%

Never/almost never ¼ 1; seldom ¼ 2; about half the time ¼ 3; most of the time ¼ 4; always/almost always ¼ 5. The percentage of respondents reporting ‘‘most of

the time’’/’’great’’ and ‘‘always/almost always’’/’’very great’’ (Likert scales ‘‘4’’ and ‘‘5’’) within a given scale were charted as percent positive, while the percentage

reporting ‘‘never’’/’’not at all’’ and ‘‘seldom’’/’’very little’’ (Likert scales ‘‘1’’ and ‘‘2’’).

Table 4. Duration of dental photography and grading process.

<5 min 5–10 min 10–15 min 15–20 min >20 min Total

Time taken to review a record on the server – 2 2 1 – 5

Time taken to create a record and for photography 1 9 4 1 – 15

graders’ ability to review images and grade teeth is the that the Android app was accurate and easy to use, the

quality of the images that the teledental assistants send. survey results showed that a substantial number of

The quality of images and the capability to grade images Android users (20%) experienced difficulty with the use

accurately are very important factors when evaluating the of the smartphone camera and a majority of the smart-

feasibility of telediagnosis of diseases.28 Many of the prob- phone users suggested that the quality of images and the

lems encountered could be overcome following further smartphone camera need further improvement. Users’

modification and optimization of the server. concerns with the smartphone camera mainly pertained

Despite attention to many issues (over bright or dark to the difficulty of obtaining good images due to issues

images) related to smartphone camera use, and adjust- relating to the optimization of phone camera features,

ment of photography protocols prior to starting the the absence of oral retractors, or lack of training.

trial, concerns with the information quality and ease of The survey shows that the average time spent on creat-

use of smartphone camera were observed (Figure 3). ing a record, uploading and grading was 20 min. Although

Although, the majority of the smartphone users believed this time is longer than an in-person oral assessment

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

Estai et al. 7

were not found to influence the intention to use the

system significantly and the latter could be attributed to

the absence of coordination between sites and lack of

prior personal experience with teledentistry. Another

important factor that may affect a user’s intention to use

telemedicine is the need for collaboration and coordin-

ation between remote and hub sites when implementing

a telemedicine system.30 Because the supervisory dental

team at the hub site cannot do a hands-on examination,

they have to rely on the assessment performed by the local

practitioner at the remote site. Repeated practice, estab-

lishing confidence, and good working relationships

between team members at both sites can establish a reli-

able and smooth teledentistry process.30

This study was not designed to examine in depth the

users’ perception of teledentistry, but it gives insights on

its acceptance. Further investigations on how different

types of factors (external or internal) operate to support

or hinder the adoption of a teledentistry model need to be

addressed. Despite the rapid growth of teledentistry, it has

not yet become an integral part of mainstream oral health

care. Future research is needed to determine the obstacles

that delay the implementation of teledentistry as an

adjunct for a comprehensive health care system.

Identifying and addressing the barriers to adoption of

teledentistry could motivate dental providers to adopt

the use of telemedicine services in daily practice.

Figure 3. Example of a smartphone camera shots. (a) An intraoral

occlusal view of upper teeth with poor image quality (blurred) due Conclusion

to being out of focus. It is not possible to observe teeth or soft Generally, users considered the teledentistry model as

tissue in this image. (b) Shows intraoral occlusal view of upper teeth useful, despite their concerns with specific aspects of the

with excellent image quality. It is possible to see decayed first molars

system. This study provides developers with key observa-

and decayed left second molar.

tions about user needs when building a teledentistry

system and can form the basis for the development of a

more user-friendly system. Utilization of teledentistry

(10–15 min), a duration of 20 min is still considered approaches for caries screening has steadily gained accept-

acceptable as the only alternative is to spend hours travel- ance in recent years. More recently mobile teledentistry,

ing to the nearest practice or sending a practitioner to a often seen as a sub-set of telemedicine, has also emerged as

remote site. Although training of teledental assistants to a possible means of screening for oral diseases. This area is

provide good quality oral images was provided and does particularly attractive due to the fact that many smart-

not consume much time, adherence to the photography phones are now equipped with digital cameras, and

protocol provided was hard to achieve. Many Android there is widespread penetration of smartphones and cellu-

users’ concerns could be resolved through more effective lar network reception globally even in underserved

training and hands-on experience. regions. We believe that these technologies (teledentistry

The results of this study partly support the TAM model and smartphones) can be combined to create an inexpen-

of telemedicine acceptance. Similar to the assertion of sive and powerful tool for screening purposes. This

TAM, perceived ease of use and usefulness was relatively approach could offer a practical and potential cost-

high among users and was positively associated with users’ saving means to screen for oral diseases among a popula-

attitude toward using the system, and these results are tion with high levels of need who have no access to care.

consistent with previous reports.14,29 However, our data The development of a cloud-based server and an image-

indicates that the perception of the system’s stability, con- acquisition Android app for screening purposes is the first

tent, and format have a strong influence on the attitude of its kind in Australia and has the potential to serve rural

towards teledentistry system. The intention to use the providers to reduce inappropriate referrals and waiting

system is not only predicted by its perceived usefulness lists for consultation as well as facilitating timely informa-

but also determined by the system’s stability, format, tion to the local practitioner for better decision-making.

and content which were rated consistently high in the Evaluation of users’ acceptance provides valuable insight

survey. Perceptions of information quality and support into the factors which impact professionals’ intentions to

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

8 Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare 0(0)

Table 5. Categories and frequencies of suggestion by respondents.

Suggestions of ways to improve the system n (%)

Remote-I (five users)

The layout of the dental chart should be further improved, e.g. making the layout horizontal rather than vertical. It would 1 (20%)

be better if the server was upgraded to a system similar to the Dental4Windows program.

Make sure that the orientation and labeling of images are correct. 3 (60%)

An image must be closed in order to use the chart. It would be easier for the clinician if the image was kept open while 1 (20%)

recording on the chart.

The headings of the columns for the dental chart are at the top, so when you record at bottom of the page, you need to 2 (40%)

scroll back to the top every time to identify the actual headings; this may lead to increased errors.

The posterior teeth were the most difficult to review due to lack of buccal retraction. Simple retraction devices such as 2 (40%)

tongue depressors would be useful.

It is impossible to edit or make corrections once a record is evaluated and the report submitted. It would be helpful to 3 (60%)

validate and double check some records if the system supported editing and corrections after submitting the records.

Android phone app (15 users)

Improve camera features such as zooming and autofocus. The quality of some captured photos was poor because the 10 (67%)

camera features are not optimized.

Improve the camera flash. Some photos were either over exposed or dark because the camera flash is not optimized. 4 (27%)

Uploading records from the Android app to the server depends on the availability of the Internet connection. I would 1 (7%)

suggest improving the current app to allow storage of records in the smartphone memory to be uploaded into the server

at a later time.

Photography of lateral views or posterior teeth was difficult because photography was done without oral retractors as per 8 (53%)

image protocol. I would suggest using disposable retractors during photography as this will help in obtaining good dental

images.

Make this app available free in the Google or Apple stores. 2 (13%)

The phone app only works on Android devices. I would suggest developing an application that can support iOS and 1 (7%)

Windows phones.

adopt teledentistry services. Building on these experiences, Shannon G (eds) Telemedicine: Theory and practice.

the next step will be the implementation of multi-site, com- Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas, 1997, pp.265–288.

munity-based, and large-scale projects that can incorporate 3. Mariño R and Ghanim A. Teledentistry: A systematic

remote dental screening and oral health promotion, and review of the literature. J Telemed Telecare 2013; 19:

involve different members of the dental team such as 179–183.

dental therapists, dental hygienists, and dental nurses. 4. Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT, Billings RJ and McConnochie

KM. Dental screening of preschool children using

Acknowledgement teledentistry: A feasibility study. Pediatr Dent 2007; 29:

209–213.

We thank Professor Boyen Huang from the Charles Sturt 5. Torres-Pereira CC, Morosini Ide A, Possebon RS, et al.

University for his contribution. We also thank all dental students Teledentistry: Distant diagnosis of oral disease using

contributed in this study. e-mails. Telemed J E Health 2013; 19: 117–121.

6. Morosini Ide A, de Oliveira DC, Ferreira Fde M, et al.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests Performance of distant diagnosis of dental caries by teledentis-

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with try in juvenile offenders. Telemed J E Health 2014; 20: 584–589.

respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this 7. Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT and Billings RJ. Comparative

article. The authors report no potential conflicts of interest. effectiveness study to assess two examination modalities

used to detect dental caries in preschool urban children.

Funding Telemed J E Health 2013; 19: 834–840.

8. Mariño R, Tonmukayakul U, Manton D, et al. Cost-analy-

The author(s) received no financial support for the research,

sis of teledentistry in residential aged care facilities.

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

J Telemed Telecare. Epub ahead of print 30 September

2015. DOI: 1357633X15608991.

9. Kopycka-Kedzierawski DT and Billings RJ. Teledentistry in

References inner-city child-care centres. J Telemed Telecare 2006; 12:

1. Bradley M, Black P, Noble S, et al. Application of teleden- 176–181.

tistry in oral medicine in a community dental service, N. 10. Neuhaus KW, Ellwood R, Lussi A, et al. Traditional lesion

Ireland. Br Dent J 2010; 209: 399–404. detection aids. Monogr Oral Sci 2009; 21: 42–51.

2. Baer L, Cukor P and Coyle JT. Telepsychiatry: Application 11. Daniel SJ and Kumar S. Access to oral care through tele-

of telemedicine to psychiatry. In: Bashshur R, Sanders J and dentistry. In: Kumar S (ed.) Teledentistry. Health informatics

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

Estai et al. 9

series. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International 21. Otieno OG, Toyama H, Asonuma M, et al. Nurses’ views on

Publishing, 2015, pp.65–74. the use, quality and user satisfaction with electronic medical

12. Carey E, Payne KFB, Ahmed N, et al. The benefit of the records: Questionnaire development. J Adv Nurs 2007; 60:

smartphone in oral and maxillofacial surgery: Smartphone 209–219.

use among maxillofacial surgery trainees and iphone apps 22. Top M, Yilmaz A and Gider Ö. Electronic medical records

for the maxillofacial surgeon. J Maxillofac Oral Surg 2015; (EMR) and nurses in Turkish hospitals. J Med Syst 2013;

14: 131–137. 26: 281–297.

13. Aziz SR and Ziccardi VB. Telemedicine using smartphones 23. Mariño R, Hopcraft M, Tonmukayakul U, et al.

for oral and maxillofacial surgery consultation, communica- Teleconsultation/telediagnosis using teledentistry technol-

tion, and treatment planning. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009; ogy: A pilot feasibility study. Int J Adv Life Sci 2014; 6:

67: 2505–2509. 291–299.

14. Davis FD, Bagozzi RP and Warshaw PR. User acceptance 24. Mariño R, Clarke K, Manton DJ, et al. Teleconsultation

of computer technology: A comparison of two theoretical and telediagnosis for oral health assessment: An

models. Manage Sci 1989; 35: 982–1003. Australian perspective. In: Kumar S (ed.) Teledentistry.

15. Hu PJ, Chau PY, Sheng ORL, et al. Examining the Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing,

technology acceptance model using physician acceptance 2015, pp.101–112.

of telemedicine technology. J Manage Inform Syst 1999; 25. Butler TN and Yellowlees P. Cost analysis of store-and-for-

16: 91–112. ward telepsychiatry as a consultation model for primary

16. Agarwal R and Prasad J. Are individual differences germane care. Telemed J E Health 2012; 18: 74–77.

to the acceptance of new information technologies? Decision 26. Okunseri C, Pajewski NM, Jackson S, et al. Wisconsin

Sci 1999; 30: 361–391. Medicaid enrollees’ recurrent use of emergency departments

17. Chau PY and Hu PJ-H. Investigating healthcare profes- and physicians’ offices for treatment of nontraumatic dental

sionals’ decisions to accept telemedicine technology: An conditions. J Am Dent Assoc 2011; 142: 540–550.

empirical test of competing theories. Inform Manage- 27. Whitten P and Love B. Patient and provider satisfaction

Amster 2002; 39: 297–311. with the use of telemedicine: Overview and rationale for

18. Paré G, Sicotte C and Jacques H. The effects of creating cautious enthusiasm. J Postgrad Med 2005; 51: 294–300.

psychological ownership on physicians’ acceptance of clin- 28. Vaziri K, Moshfeghi DM and Moshfeghi AA. Feasibility of

ical information systems. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2006; 13: telemedicine in detecting diabetic retinopathy and age-

197–205. related macular degeneration. Semin Ophthalmol 2015; 30:

19. Estai M, Kanagasingam Y, Xiao D, et al. A proof- 81–95.

of-concept evaluation of a cloud-based store-and-forward 29. Chen R-F and Hsiao J-L. An empirical study of physicians’

telemedicine app for screening for oral diseases. J Telemed acceptance of hospital information systems in Taiwan.

Telecare. Epub ahead of print 16 September 2015. DOI: Telemed J E Health 2012; 18: 120–125.

1357633X15604554. 30. Fricton J and Chen H. Using teledentistry to improve access

20. Xiao D, Vignarajan J, Boyle J, et al. Development and prac- to dental care for the underserved. Dent Clin North Am 2009;

tice of store-and-forward telehealth systems in ophthalmol- 53: 537–548.

ogy dental and emergency. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015;

214: 167–173.

Downloaded from jtt.sagepub.com at University of Western Australia on January 11, 2016

View publication stats

You might also like

- Machine Learning in DentistryFrom EverandMachine Learning in DentistryChing-Chang KoNo ratings yet

- Futuristic Advances That Might Change The Future of Oral Medicine and RadiologyDocument15 pagesFuturistic Advances That Might Change The Future of Oral Medicine and RadiologyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- The Orthodontic Mini-Implants Failures Based On Patient Outcomes: Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesThe Orthodontic Mini-Implants Failures Based On Patient Outcomes: Systematic ReviewKristin HalimNo ratings yet

- TeledentistryDocument4 pagesTeledentistrypopat78100% (1)

- Using Digital Stethoscopes in Remote Patient Assessment Via Wireless Networks: The User's PerspectiveDocument7 pagesUsing Digital Stethoscopes in Remote Patient Assessment Via Wireless Networks: The User's PerspectiveHelmi NurmaNo ratings yet

- Tooth Detection and Numbering in Panoramic Radiographs Using Convolutional Neural NetworksDocument11 pagesTooth Detection and Numbering in Panoramic Radiographs Using Convolutional Neural Networksalexis casanovaNo ratings yet

- Applications of Teledentistry: A Literature Review and UpdateDocument9 pagesApplications of Teledentistry: A Literature Review and UpdateAyu SawitriNo ratings yet

- Teledentistry: A Review On Its Present Status and Future PerspectivesDocument6 pagesTeledentistry: A Review On Its Present Status and Future PerspectivesNiki Pratiwi WijayaNo ratings yet

- Real-Time Teleophthalmology Versus Face-To-Face Consultation: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesReal-Time Teleophthalmology Versus Face-To-Face Consultation: A Systematic ReviewJatinderBaliNo ratings yet

- A Smart Home Dental Care System: Integration of Deep Learning, Image Sensors, and Mobile ControllerDocument9 pagesA Smart Home Dental Care System: Integration of Deep Learning, Image Sensors, and Mobile ControllerLarissa AndradeNo ratings yet

- Title: Whatsapp Is An Effective Tool For Obtaining Second Opinion in Oral PathologyDocument21 pagesTitle: Whatsapp Is An Effective Tool For Obtaining Second Opinion in Oral PathologySarahNo ratings yet

- Teledentistry For Saudi CareDocument7 pagesTeledentistry For Saudi Caredoc purwitaNo ratings yet

- EBD Nature Journal-Clinical Outcomes of Implant Supported-2023Document8 pagesEBD Nature Journal-Clinical Outcomes of Implant Supported-2023NARESHNo ratings yet

- Dentistry 11 00125 v2Document13 pagesDentistry 11 00125 v2KWAKU AGYEMANG DUAHNo ratings yet

- Glass Teletox JMTDocument6 pagesGlass Teletox JMTRanze UyNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics 12 00224Document11 pagesDiagnostics 12 00224abdulrazaqNo ratings yet

- Running Title: Digital Vs Conventional Implant Impressions: DDS, MS, PHDDocument41 pagesRunning Title: Digital Vs Conventional Implant Impressions: DDS, MS, PHDÁł ÃăNo ratings yet

- 2 Can Artificial Intelligence Make Screening Faster, More Accurate, and More AccessibleDocument6 pages2 Can Artificial Intelligence Make Screening Faster, More Accurate, and More Accessible钟华No ratings yet

- Bioburden in Chronic WoundDocument24 pagesBioburden in Chronic Woundeva arna abrarNo ratings yet

- Comparison of the Accuracy of Optical Impression Systems in Three Different Clinical SituationsDocument8 pagesComparison of the Accuracy of Optical Impression Systems in Three Different Clinical SituationsMathias SchottNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S030057121830099X MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S030057121830099X Mainkiara wardanaNo ratings yet

- Cjy 066Document9 pagesCjy 066Meris JugadorNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Deep Learning in The Field of Dentistry: Jae-Joon Hwang, Yun-Hoa Jung, Bong-Hae Cho, Min-Suk HeoDocument7 pagesAn Overview of Deep Learning in The Field of Dentistry: Jae-Joon Hwang, Yun-Hoa Jung, Bong-Hae Cho, Min-Suk Heomahendra dwi irawanNo ratings yet

- Implementing Teledentistry for Orthodontic PracticesDocument5 pagesImplementing Teledentistry for Orthodontic PracticesRonald R Ramos MontielNo ratings yet

- WIREs Data Min Knowl - 2023 - Shaik - Remote Patient Monitoring Using Artificial Intelligence Current StateDocument31 pagesWIREs Data Min Knowl - 2023 - Shaik - Remote Patient Monitoring Using Artificial Intelligence Current StateMadhuri DesaiNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence For Long-Term RespiratoryDocument6 pagesArtificial Intelligence For Long-Term Respiratorydrnasir31No ratings yet

- Digitization and Its Futuristic Approach in ProsthodonticsDocument10 pagesDigitization and Its Futuristic Approach in ProsthodonticsManjulika TysgiNo ratings yet

- Mechanical Paque RemovalDocument16 pagesMechanical Paque RemovalMihaiNo ratings yet

- IA e OrtodontiaDocument9 pagesIA e OrtodontiaCarolina DezanNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877042813037609 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S1877042813037609 Mainliyun19981234No ratings yet

- Histopathologic Oral Cancer Prediction Using Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Biopsy Empowered With Transfer LearningDocument14 pagesHistopathologic Oral Cancer Prediction Using Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Biopsy Empowered With Transfer Learningvera cruNo ratings yet

- Identification of Cancerous Cell From Noisy ImagesDocument5 pagesIdentification of Cancerous Cell From Noisy ImagesIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Comparison of artificial intelligence vs. junior dentists' diagnostic performance based on caries and periapical infection detection on panoramic imagesDocument10 pagesComparison of artificial intelligence vs. junior dentists' diagnostic performance based on caries and periapical infection detection on panoramic imageskarenyaxencorrearivasNo ratings yet

- Deep Convolutional Neural Networks in Thyroid Disease Detection-Full TextDocument10 pagesDeep Convolutional Neural Networks in Thyroid Disease Detection-Full TextJamesLeeNo ratings yet

- Suresh2022 PDFDocument8 pagesSuresh2022 PDFFilipe do Carmo Barreto DiasNo ratings yet

- Ejoi 2021 02 s0157Document24 pagesEjoi 2021 02 s0157Daniel AtiehNo ratings yet

- Pneumonia Detection in X-Ray Chest Images Based On CNN and Data AugmentationDocument18 pagesPneumonia Detection in X-Ray Chest Images Based On CNN and Data AugmentationIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Teledentistry in Periodontal Diagnosis: A New Age PracticeDocument7 pagesTeledentistry in Periodontal Diagnosis: A New Age PracticeInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Detection of Cancer Using Boosting Tech Web AppDocument6 pagesDetection of Cancer Using Boosting Tech Web AppIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- JCM 11 06854 v2Document9 pagesJCM 11 06854 v2Juliana ÁlvarezNo ratings yet

- journal.pone.0269323 (1)Document13 pagesjournal.pone.0269323 (1)sowmiNo ratings yet

- Digital Cytopathology JCDocument26 pagesDigital Cytopathology JCAchin KumarNo ratings yet

- Jcda 2021 AiDocument8 pagesJcda 2021 AiSherienNo ratings yet

- Cureus-Diagnosis AidsDocument10 pagesCureus-Diagnosis AidsAshish KushwahNo ratings yet

- Caries DetectionDocument7 pagesCaries DetectionShahid ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Prediction of pulp exposure before caries excavation using artificial intelligence Deep learning-based image data versus standard dental radiographsDocument7 pagesPrediction of pulp exposure before caries excavation using artificial intelligence Deep learning-based image data versus standard dental radiographskarenyaxencorrearivasNo ratings yet

- 2019 - CBCT in Orthodontics - de GrauweDocument9 pages2019 - CBCT in Orthodontics - de GrauweSrdjan StojanovskiNo ratings yet

- Digital Intraoral ScannerDocument16 pagesDigital Intraoral ScannerReham RashwanNo ratings yet

- Prevention Work AccidentDocument6 pagesPrevention Work AccidenthumairohimaniaNo ratings yet

- Applications of Teledentistry A Literature Review and UpdateDocument4 pagesApplications of Teledentistry A Literature Review and Updatec5j07dceNo ratings yet

- A Perspective On The Diagnosis of Cracked ToothDocument22 pagesA Perspective On The Diagnosis of Cracked ToothImplantologia Oral Reconstructuva UnicieoNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Kidney Stones Using Machine LearningDocument10 pagesPrediction of Kidney Stones Using Machine LearningIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Marlière Et Al. 2018 ProsthodonticsDocument8 pagesMarlière Et Al. 2018 ProsthodonticsApril FloresNo ratings yet

- Device-Related Pressure Ulcers SECURE PreventionDocument52 pagesDevice-Related Pressure Ulcers SECURE Preventionasn1981No ratings yet

- Improvement of Automatic Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours Using MLDocument6 pagesImprovement of Automatic Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Tumours Using MLIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Factors Affecting Compliance of Infection Control Measures Among Dental RadiographersDocument11 pagesResearch Article: Factors Affecting Compliance of Infection Control Measures Among Dental RadiographersPRADNJA SURYA PARAMITHANo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of The Research Evidence For The Benefits of TeledentistryDocument10 pagesA Systematic Review of The Research Evidence For The Benefits of TeledentistryJaime GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Vet Care ApplicationDocument5 pagesVet Care ApplicationIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence in Ododontics Current Application and Future DirectionsDocument6 pagesArtificial Intelligence in Ododontics Current Application and Future DirectionsYoussef BoukhalNo ratings yet

- Using E-Technologies in Clinical Trials Rosa 2015Document14 pagesUsing E-Technologies in Clinical Trials Rosa 2015Itzcoatl Torres AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Mural HaDocument1 pageMural HaDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Automated Caries Detection With Smartphone Color PDocument17 pagesAutomated Caries Detection With Smartphone Color PDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- 9755 ArticleText 18338 1 10 20200723Document6 pages9755 ArticleText 18338 1 10 20200723Dannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of Dental Photography Professional Vs SmaDocument7 pagesAccuracy of Dental Photography Professional Vs SmaDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Digital Dental Photography Usage in RomaniaDocument6 pagesDigital Dental Photography Usage in RomaniaDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- PreciousPrecarious Images Cameroonian Studio PhotoDocument21 pagesPreciousPrecarious Images Cameroonian Studio PhotoDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Control lighting and rotation for product photography with IoT Mini StudioDocument2 pagesControl lighting and rotation for product photography with IoT Mini StudioDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 19OMCT32 VOL21 AZRIN 115121Document8 pagesJurnal 19OMCT32 VOL21 AZRIN 115121Dannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Paper14e 001-SmallDocument11 pagesPaper14e 001-SmallDannilo CerqueiraNo ratings yet

- Oil-Free Screw Compressors: Water-Injected TechnologyDocument12 pagesOil-Free Screw Compressors: Water-Injected TechnologyCsaba SándorNo ratings yet

- 056-123 Simulation Injection TestingDocument6 pages056-123 Simulation Injection TestingRoxanneNo ratings yet

- Progress Test 02Document21 pagesProgress Test 02andrewlaurenNo ratings yet

- SM - Project Report - Group-11Document15 pagesSM - Project Report - Group-110463SanjanaNo ratings yet

- Sharp CD E700 CD E77Document60 pagesSharp CD E700 CD E77Randy LeonNo ratings yet

- AIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA I CardDocument2 pagesAIRPORTS AUTHORITY OF INDIA I Cardkallul5551350100% (1)

- CIO 100 2011 - Google Apps For Business-Keval Shah-SumariaDocument9 pagesCIO 100 2011 - Google Apps For Business-Keval Shah-SumariaCIOEastAfricaNo ratings yet

- Role of Print Media in AdvertisementDocument14 pagesRole of Print Media in AdvertisementMoond0070% (1)

- Electric MachineDocument26 pagesElectric MachinealexNo ratings yet

- Sample - Table - Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesSample - Table - Literature ReviewKeyur KevadiyaNo ratings yet

- The National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan: 2019 UpdateDocument50 pagesThe National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan: 2019 UpdateDarth VaderNo ratings yet

- Cockpit and Passenger Compartment Separation Solutions 1588230875Document14 pagesCockpit and Passenger Compartment Separation Solutions 1588230875rubenarisNo ratings yet

- Eds Management Center ExamDocument5 pagesEds Management Center ExamJez MavNo ratings yet

- 22 Simple Ways To Increase Instagram Engagement (Free Calculator)Document3 pages22 Simple Ways To Increase Instagram Engagement (Free Calculator)you forNo ratings yet

- Intel Gemini Lake Block Diagram EJ-11 ZHE 11"Document37 pagesIntel Gemini Lake Block Diagram EJ-11 ZHE 11"Tomy Aditya PratamaNo ratings yet

- Mrs J's Resource Creations ©Document7 pagesMrs J's Resource Creations ©syddysNo ratings yet

- Action Plan Custodian SY 2018 FinalDocument2 pagesAction Plan Custodian SY 2018 FinalStarLord JedaxNo ratings yet

- BS en 12953-12-2003Document22 pagesBS en 12953-12-2003Tuấn ChuNo ratings yet

- Memorandum: From: TJC and Associates, Inc. Date: March, 2014 Subject: Seismic Anchorage Submittals ChecklistDocument2 pagesMemorandum: From: TJC and Associates, Inc. Date: March, 2014 Subject: Seismic Anchorage Submittals ChecklistponjoveNo ratings yet

- Consultancy Dossier 1Document4 pagesConsultancy Dossier 1Ghita NaaimyNo ratings yet

- Systems 11 00237Document20 pagesSystems 11 00237EX MOBILENo ratings yet

- Sprinkler Protection Guidance For Lithium-Ion Based Energy Storag e SystemsDocument46 pagesSprinkler Protection Guidance For Lithium-Ion Based Energy Storag e SystemsAlexNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence Big Data 01 Research PaperDocument32 pagesArtificial Intelligence Big Data 01 Research PapermadhuraNo ratings yet

- Atswa: Study TextDocument479 pagesAtswa: Study TextBrittney JamesNo ratings yet

- Advanced Isometric Configuration in AutoCADPlant3DDocument49 pagesAdvanced Isometric Configuration in AutoCADPlant3DRoobens SC Lara100% (1)

- C-Zone SDN BHD: WWW - Czone.myDocument2 pagesC-Zone SDN BHD: WWW - Czone.myFirman SyahNo ratings yet

- Merlin Gerin Medium Voltage Distribution Switchgear Technical ManualDocument18 pagesMerlin Gerin Medium Voltage Distribution Switchgear Technical ManualMohammed Madi100% (1)

- 2.2 Organizational StructureDocument60 pages2.2 Organizational StructureMateo Valenzuela Rodriguez100% (1)

- Sugar Mommy PDF 3Document1 pageSugar Mommy PDF 3mudashiradebamiji100% (2)

- Energy Saving HRC Fuse-Links: Blade Type HN 63 A - 800 A Cylindrical Type HF 2 A - 63 ADocument8 pagesEnergy Saving HRC Fuse-Links: Blade Type HN 63 A - 800 A Cylindrical Type HF 2 A - 63 AprekNo ratings yet