Professional Documents

Culture Documents

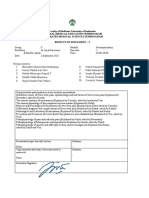

Exercise BMT

Exercise BMT

Uploaded by

Mohammad Al SarairehCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Exercise BMT

Exercise BMT

Uploaded by

Mohammad Al SarairehCopyright:

Available Formats

Exercise

Downloaded on 01 20 2018. Single-user license only. Copyright 2018 by the Oncology Nursing Society. For permission to post online, reprint, adapt, or reuse, please email pubpermissions@ons.org

Intervention

Attrition, compliance, adherence, and progression following

M

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Tara Peters, BS, Ruby Erdmann, RD, LDN, and Eileen Danaher Hacker, PhD, APN, AOCN®, FAAN

BACKGROUND: Exercise is widely touted as an MORE THAN 20,000 HEMATOPOIETIC STEM CELL TRANSPLANTATIONS (HSCTs) were

effective intervention to optimize health and performed in the United States in 2015, a rate that continues to increase (D’Souza

well-being after high-dose chemotherapy and & Zhu, 2016). This figure includes recipients of autologous and allogeneic

hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. HSCTs. The preparatory regimens used in conjunction with HSCT frequently

result in a wide range of acute and chronic side effects, such as infection, throm-

OBJECTIVES: This article reports attrition, bocytopenia, and fatigue (Copelan, 2006). Recipients of allogeneic HSCT are

compliance, adherence, and progression from the at risk for additional complications, including graft-versus-host disease.

strength training arm of the single-blind random- The adverse effects of the high-dose chemotherapy may be severe and

ized, controlled trial Strength Training to Enhance highly distressing, negatively affecting the recipient’s quality of life (Cohen

Early Recovery (STEER). et al., 2012). Although many side effects are temporary and resolve within

three to six months, others are long-term and develop months or years after

METHODS: 37 patients were randomized to the HSCT (Morrison et al., 2016). For example, moderate to severe persistent

intervention and participated in a structured strength fatigue has been documented during the early recovery period and years

training program introduced during hospitalization after HSCT (Gielissen et al., 2007; Hacker, Fink, et al., 2017; Jim et al., 2016).

and continued for six weeks after release. Research Interventions to address these distressing symptoms are needed to improve

staff and patients maintained exercise logs to docu- the long-term outcomes of HSCT recipients.

ment compliance, adherence, and progression. Strong interest exists in the development of effective exercise interventions

for patients receiving intensive cancer therapy, including those undergoing

FINDINGS: No patients left the study because of HSCT. Fewer than 20 randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) testing exer-

burden. Patients were compliant with completion cise interventions have been conducted in this population (Hacker, Collins,

of exercise sessions, and their adherence was high; et al., 2017; Jacobsen et al., 2014; Persoon et al., 2013). Although the general

they also progressed on their exercise prescription. evidence supports the use of exercise in this population, implementation

Because STEER balances intervention effectiveness varies across studies, such as timing of exercise initiation and the exercise

with patient burden, the findings support the likeli- modality, intensity, and duration. Because of the challenges associated with

hood of successful translation into clinical practice. conducting exercise studies and then translating these findings into clinical

practice, multiple additional pragmatic factors need to be fully assessed prior

to implementing exercise interventions in the general population of patients

KEYWORDS undergoing HSCT. These study factors include the following:

attrition; compliance; adherence; progres- ɐɐ Patient attrition (number of patients leaving the study prior to completion)

sion; hematopoietic stem cell transplantation ɐɐ Exercise compliance (ability to complete the prescribed number of exer-

cise sessions)

DIGITAL OBJECT IDENTIFIER ɐɐ Exercise adherence (ability to complete the specific exercises as detailed in

10.1188/18.CJON.97-103 the exercise prescription)

ɐɐ Exercise progression (ability to advance the exercise prescription)

CJON.ONS.ORG VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING 97

EXERCISE INTERVENTION

In addition, information related to how actively HSCT recipients

participated in the exercise activities when categorized according

to age, gender, and type of transplantation may prove helpful when

“Fewer than 20

translating evidence into practice.

A single-blind RCT conducted by Hacker, Collins, et al. (2017)

randomized,

(Strength Training to Enhance Early Recovery [STEER]) found

that strength training positively affected fatigue, physical activity,

controlled trials

muscle strength, and functional ability in those assigned to

strength training compared to usual care plus attention control

testing exercise

with health education. The purpose of this article is to provide

more detailed information regarding patient attrition and exer-

interventions have

cise compliance, adherence, and progression from the strength

training arm of the STEER study to help facilitate translation into

been conducted in

practice and to report exercise compliance, adherence, and pro-

gression based on age, gender, and type of transplantation.

this population.”

Methods

Design patients needed to be ambulatory (with or without the use of

The methods and study procedures for the main study have an assistive device) to continue participation in the moderate-

been reported (Hacker, Collins, et al., 2017). As a review, the intensity strength training phase of the study.

single-blind RCT examined the efficacy of the STEER interven- The study was open to enrollment from May 2013 to July

tion compared to usual care plus attention control with health 2015. Overall, 118 patients were eligible to participate, and 84

education following HSCT on fatigue, physical activity, muscle (71%) agreed. Reasons for refusal included feeling overwhelmed

strength, functional ability, and quality of life. The sample was and being uninterested in research participation. Five of the 84

stratified by type of transplantation (allogeneic, autologous) patients did not proceed to HSCT and were withdrawn from the

and age (aged younger than 60 years, aged 60 years or older). study prior to completing any research activities. Seventy-nine

Random allocation to treatment and allocation concealment patients completed baseline testing, and four were later withdrawn

were achieved using sequentially numbered sealed envelopes because they did not proceed to HSCT. Seventy-five patients

(Doig & Simpson, 2005). All patients were recruited from the were randomized to the STEER intervention (n = 37) or to usual

University of Illinois Hospital and Health Systems in Chicago. care plus attention control with health education (n = 38). Seven

Strength training instruction and active range of motion began patients died during the study, and one was lost to follow-up.

during HSCT hospitalization, with moderate-intensity training These deaths were unrelated to the research. A total of 67

for six weeks following hospital discharge. This article details patients completed all research activities (STEER, n = 33; usual

the attrition, compliance, adherence, and progression findings care plus attention control with health education, n = 34). This

from those randomized to the moderate-intensity strength train- article focuses solely on those randomized to the STEER arm of

ing arm following HSCT hospitalization to facilitate translation the study.

into practice. The University of Illinois at Chicago’s institutional

review board approved the study. Strength Training Intervention

The STEER intervention is a comprehensive exercise program that

Sample employs progressive resistance exercise to strengthen the upper

Eligibility criteria for the STEER study included being aged 18 and lower body and abdominal muscles. Strength training instruc-

years or older, being cognitively able to provide informed con- tion and active range of motion began during hospitalization for

sent, and receiving HSCT for treatment of a malignancy. Potential HSCT (two times per week). Following hospital discharge, patients

HSCT recipients undergo an extensive medical workup prior to completed the moderate-intensity strength training portion of the

HSCT, which is the standard of care. The results of this workup program using elastic resistance bands. Moderate intensity was

were reviewed by the treating physicians who provided approval defined as a self-reported rating of moderately hard using the Borg

for patients to take part in the study if randomized to the strength Rating of Perceived Exertion scale (Borg, 1998). This phase of the

training arm. Patients were ineligible if they had a condition that program lasted six weeks, for a total of 18 exercise sessions (three

would make exercise unsafe, such as an impending pathologic times per week for six weeks).

fracture or other musculoskeletal condition that resulted in a Eleven preselected exercises with concentric and eccentric

nonambulatory status. Following discharge from the hospital, muscle contractions were included in the STEER intervention.

98 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CJON.ONS.ORG

Eight exercises used elastic resistance bands (chest fly, bicep TABLE 1.

curl, tricep extension, shoulder shrug, shoulder upright row, SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS BY GROUP

shoulder lateral raise, knee flexion, and knee extension) and

three exercises used body weight as resistance (wall push-up, HOSPITAL POST-HOSPITAL

EXERCISE GROUP EXERCISE GROUP

squat, and bed sit-up). The exercise prescription was tailored to (N = 37) (N = 33)

the individual’s capabilities. Because safety was a primary con-

cern, patients were prescribed as many exercises as they could CHARACTERISTIC n n

safely perform, beginning with the easiest and progressing to the

Age (years)

most complex. For example, a patient with low exercise tolerance

would be initially prescribed fewer exercises and/or fewer repe- Younger than 60 23 22

titions or sets, with additional exercises, repetitions, and/or sets

60 or older 14 11

added in later weeks as his or her exercise tolerance improved.

Return demonstrations were required for all patients to ensure Gender

proper form, assess tolerance, and reduce the risk of injury. Using

downtime during regularly scheduled clinic visits, patients gen- Male 22 20

erally exercised once a week under the supervision of a member Female 15 13

of the research team and completed the remaining two sessions

unsupervised at home. The STEER intervention took about 20 Race

minutes to complete. Changes to the exercise prescription, pri-

Black or African American 15 14

marily advancements, were made during the supervised sessions.

Progression of the exercise prescription was structured to first White or Caucasian 17 14

increase the number of repetitions, followed by an increase in

Latino, Hispanic, or Mexican

the number of sets (from one to two sets) and an increase in the American

4 4

resistance level of elastic bands. Patients and research staff main-

tained detailed exercise logs documenting the completion of each Other 1 1

individual exercise, including information about the number of

Marital status

repetitions and sets on preprinted exercise logs. Queries related

to exercise tolerance were made during weekly clinic visits. If Never married 6 6

a weekly visit was not scheduled with the healthcare provider,

Married 21 18

patients were contacted by telephone to review the exercise pre-

scription, tolerance, and progress. Divorced 7 6

All equipment needed for study participation was provided to

the participating patients. Each patient received elastic resistance Separated 2 2

bands with handles for upper-body exercises, elastic resistance Widowed 1 1

bands with extremity straps for lower-extremity exercises, a

door anchor for exercises that required external fixation (chest Education level

fly), individualized preprinted exercise instructions, preprinted

Some high school 2 2

exercise logs for tracking, a folder to store the instructions and

logs, and a small gym bag to carry all equipment for a total supply Graduated from high school 10 9

weight of less than three pounds. Patients were instructed to

Some college 16 15

bring all supplies to the weekly supervised sessions.

Graduated from college 6 5

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics Graduate school 3 2

Thirty-seven patients undergoing HSCT were randomized into

Type of HSCT

the STEER intervention group. Demographic and clinical charac-

teristics are reported in Table 1. Those randomized to STEER were Autologous 21 20

—

primarily middle-aged (X = 53.1 years, SD = 13.5), and slightly more

Allogeneic 16 13

than half were male (n = 22) and married (n = 21). The sample was

racially diverse. Most patients had completed some high school, Continued on the next page

graduated from high school, or attended some college, and they

CJON.ONS.ORG VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING 99

EXERCISE INTERVENTION

TABLE 1. (CONTINUED) Adherence

SAMPLE CHARACTERISTICS BY GROUP The adherence results for the moderate-intensity strength train-

ing portion of the study are reported in Table 3. The strength

HOSPITAL POST-HOSPITAL training prescription was tailored to the individual’s capabilities

EXERCISE GROUP EXERCISE GROUP

(N = 37) (N = 33)

and contained information related to the number of exercises

to be performed, the number of sets and repetitions for each

CHARACTERISTIC n n exercise, and the color of the elastic resistance bands to be used

Annual family income ($) for exercises employing bands. Adherence rates are reported

as the number of exercises performed in each session divided

Less than 40,000 23 21 by the total number of exercises prescribed for each session. A

41,000–60,000 4 3 maximum of 11 exercises could be prescribed, depending on the

patient’s physical condition. Patients were highly adherent to the

61,000 or more 10 9 exercise prescription, with an adherence rate of 89%. Although

Diagnosis little difference was noted between recipients of autologous and

allogeneic HSCT, men and those aged 60 years or older were

Acute lymphoblastic leukemia 2 2 more likely to adhere to the exercise prescription. Most patients

Acute myelogenous leukemia 9 7 completed 9–11 exercises during each session.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia 1 1 Progressions After Initial Prescription

Chronic myelogenous leukemia 2 2 The ability of a patient to progress on the exercise prescription

generally indicates improving health fitness. Progression may

Hodgkin lymphoma 2 2 occur by adding more exercises to the exercise prescription, adding

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma 6 5 repetitions to the individual exercise(s), adding sets to the individ-

ual exercise(s), and/or increasing resistance used, as demonstrated

Multiple myeloma 12 12 by using a band with increased resistance. The mean number of

Myelodysplastic syndrome 3 2 progressions for patients assigned to the strength training arm was

2.6 (SD = 1.6).

HSCT—hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

Discussion

reported annual family income levels of less than $40,000. Most Growing evidence supports the health benefits of exercise in

received autologous transplantations. the population of patients undergoing HSCT (Persoon et al.,

2013; van Haren et al., 2013). However, wide variation exists in

Attrition the HSCT population examined, timing of the exercise interven-

Four patients died during the study because of disease- and/or tion, and exercise mode, duration, and intensity. Understanding

treatment-related complications, which represented an 11% patient attrition, along with exercise compliance, adherence,

attrition rate. None of the deaths, which occurred during HSCT and progression, is important for interpreting outcomes. A sin-

hospitalization, were attributable to STEER study–related activ- gle-blind RCT supports the use of strength training for reducing

ities. This resulted in a post-hospital STEER intervention group fatigue and improving functional ability (Hacker, Collins, et al.,

of 33 patients. 2017). Results from this study provide additional information

for clinicians to translate these findings into clinical practice. In

Compliance this study, no patients assigned to the STEER intervention left

The compliance results for the moderate-intensity strength the study because it was too burdensome. In addition, patients

training portion of the study (number of sessions completed of demonstrated high compliance and adherence. Patients assigned

18 scheduled sessions) are reported in Table 2. Overall, patients to the STEER intervention were able to demonstrate progression

—

were highly complaint, with a compliance rate of 83% (X = 15 ses- on the exercise prescription, further indicating improvement in

sions, SD = 4). One patient did not complete any exercise sessions; health status. Findings from the current study, along with out-

when this patient was removed from the analysis, the compliance comes from the main study, suggest that the STEER intervention

—

rate rose to 86% (X = 15.4 sessions, SD = 3). Independent sam- is effective for reducing fatigue and improving functional abil-

ples t tests were used to compare compliance rates based on age, ity. The STEER intervention effectively balances intervention

gender, and type of transplantation. No significant differences effectiveness with patient burden, as evidenced by the very low

were observed in compliance rates based on these variables. attrition and high compliance and adherence rates, as well as by

100 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CJON.ONS.ORG

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE

ɔɔ Realize that recipients of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

(HSCT) may be able to tolerate a moderate-intensity strength train-

ing intervention during the acute recovery period following HSCT.

the ability of patients to progress on the exercise intervention ɔɔ Address pragmatic concerns (e.g., attrition, compliance, adher-

during the study. ence, progression) in exercise studies with positive outcomes for

Putting evidence into practice is a key component of oncology interpretation of study findings and eventual translation into clinical

nursing care. As clinicians pool results from RCTs that examine practice.

the effects of exercise on health outcomes following HSCT, ɔɔ Use a patient-centered approach when developing exercise inter-

answers to multiple pragmatic questions can serve as a template ventions to balance intervention effectiveness with patient burden.

for translating results into clinical practice. Issues to address

include attrition, compliance, adherence, and progression so that

RCT findings can be interpreted in light of practical issues fre- people receiving intensive cancer therapy. Compared to other

quently faced in the clinical setting. For example, understanding cancer populations, patients undergoing HSCT are understudied

why patients drop out of exercise studies following HSCT is in exercise intervention studies because of methodologic chal-

important for assessing acceptability of the exercise interven- lenges, such as initiating an exercise routine despite severe

tion. HSCT exercise studies that are highly effective but have fatigue during the acute recovery period. The STEER interven-

high dropout rates related to the exercise intervention may be tion required more than three years of pilot testing to ensure

more difficult to implement in a clinical setting, particularly if the feasibility, acceptability, and safety, laying the foundation for this

patient burden is too high. single-blind RCT (Hacker, Collins, et al., 2017; Hacker, Larson,

Thoughtful consideration of the specific needs of the patient Kujath, et al., 2011; Hacker, Larson, & Peace, 2011). Importantly,

population must be given when developing an exercise inter- STEER was designed to be a pragmatic, inexpensive, nurse-driven

vention; this becomes even more important when working with intervention that could be seamlessly integrated into clinical prac-

tice. To facilitate this, the STEER intervention was implemented

TABLE 2. in two phases. The inpatient phase of the study was designed

COMPLIANCE WITH MODERATE-INTENSITY to instruct patients on the exercises, initiate muscle memory

STRENGTH TRAINING AFTER HSCT HOSPITAL by having patients perform active range of motion to simulate

DISCHARGE the exercises, and establish rapport so patients would become

familiar with the exercise team. The second phase, moderate-

EXERCISE SESSIONS COMPLETED intensity strength training, began following hospital discharge

— when patients were considered to be medically stable. Because of

COMPLIANCE N X SD %

the two-phase process, the moderate-intensity strength training

Compliance was likely perceived as a continuation of their exercise program

33 15 4 83

overall

and not as a new activity. This is important because the transi-

Compliance of tion from hospital to home can be a particularly stressful time for

32 15.4 3 86

active patients patients and their families. Initiating new activities during this

Type of HSCT time frame may be difficult. As a result, the inpatient phase was

instrumental for the success of the moderate-intensity training

Autologous 20 15.1 4.9 84 following hospital discharge.

Allogeneic 13 14.9 2.3 82 Adopting a patient-centered approach to implementing an

exercise intervention is also important for successful outcomes

Age (years) and translation into clinical practice. This study capitalized on

Younger than common clinical situations to implement the study and interven-

22 15.1 4.2 84

60 tion. For example, this study did not require extra visits outside

of the patients’ regularly scheduled clinic visits. The supervised

60 or older 11 14.7 3.7 82

exercise sessions were conducted in the clinic during downtime

Gender to make effective use of the patients’ time. Many people prefer to

exercise with a partner; having patients exercise with a member

Male 20 15.9 2.9 88

of the research team in the clinic examination room created a

Female 13 13.5 5.1 75 friendly and respectful relationship. These simple strategies were

implemented to maximize benefit to patients while minimizing

HSCT—hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; STEER—Strength Training to Enhance

Early Recovery burden. Findings from this study suggest that this approach was

Note. Compliance was defined as the number of STEER sessions completed divided by highly successful, as evidenced by high compliance and adher-

the total number of STEER sessions. Participants were expected to complete 18 exercise

sessions following hospital discharge (three times per week for six weeks). ence to the moderate-intensity strength training program. This

is important because patients undergoing HSCT are arguably one

CJON.ONS.ORG VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING 101

EXERCISE INTERVENTION

of the most complex cancer populations, particularly during the among people with cancer include community-based exercise

acute recovery period following transplantation. programs for cancer survivors (Musanti & Murley, 2016) and the

Other activities and advancements in technology may prove power of exercise from a survivor’s perspective (Hope, 2016).

beneficial in exercise studies following HSCT in the future. For

example, motivational text or voice messages may be used as an Conclusion

extra tool to facilitate compliance and adherence (Wang et al., Recipients of HSCT are able to tolerate a moderate-intensity

2015). Incentives, such as goal-related certificates or small prizes, strength training intervention during the acute recovery period

have been used in other studies with good results and should be following transplantation, as demonstrated by the low attrition

considered for future studies (Brassil et al., 2014). Adding a wear- and high compliance and adherence rates, as well as the patients’

able step counter may also be beneficial to patients enrolled in ability to progress on their exercise prescription during the study.

studies. Some patients could find the addition of group exercise These findings suggest that the STEER intervention maintains a

sessions in the clinical setting to be helpful; however, the need for beneficial sustained exercise regimen without placing additional

constant individualized reevaluation of exercise prescription may stress on an already highly burdened population. Addressing the

make that unmanageable. pragmatic concerns of intervention effectiveness and uptake

From a clinical practice perspective, oncology nurses are among participants provides important information to translate

uniquely qualified to lead programs aimed at increasing physical successful interventions, such as STEER, into clinical practice.

activity across the cancer survivorship trajectory. In consultation

with other oncology practitioners, efforts geared toward assessing Tara Peters, BS, is a visiting research specialist in the College of Nursing in the

patients for functional limitations, designing individualized phys- Department of Biobehavioral Health Science at the University of Illinois at Chicago;

ical activity and exercise interventions, and providing patients Ruby Erdmann, RD, LDN, is the director of nutrition services at Near North Health

with appropriate resources to facilitate successful implementa- Service Corporation in Chicago; and Eileen Danaher Hacker, PhD, APN, AOCN®,

tion will help to move exercise science forward (Austin, Damani, FAAN, is a professor in the School of Nursing and chair of the Department of

& Bevers, 2016; Haas, Hermanns, & Kimmel, 2016; McNeely, Science of Nursing Care at Indiana University in Indianapolis and was, at the time

Dolgoy, Al Onazi, & Suderman, 2016; Musanti & Murley, 2016). of this research, an associate professor in the College of Nursing at the University

Examples of initiatives to promote physical activity and exercise of Illinois at Chicago. Hacker can be reached at edhacker@iu.edu, with copy to

CJONEditor@ons.org. (Submitted April 2017. Accepted for publication June 19,

TABLE 3. 2017.)

ADHERENCE TO MODERATE-INTENSITY STRENGTH

TRAINING AFTER HSCT HOSPITAL DISCHARGE The authors gratefully acknowledge Kevin Grandfield, MFA, for his editorial

assistance.

MEAN ADHERENCE

CHARACTERISTIC N RATE (%)

The authors take full responsibility for this content. This study was funded by a Research Scholar

Overall 33 89 Grant (RSG, 13-054-01-PCSM; principal investigator: Hacker) from the American Cancer Society.

The article has been reviewed by independent peer reviewers to ensure that it is objective and

Type of HSCT

free from bias.

Autologous 20 92

REFERENCES

Allogeneic 13 92

Austin, A., Damani, S., & Bevers, T. (2016). Clinical approach for patient-centered physical

Age (years) activity assessment and interventions. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(Suppl. 2),

S3–S7. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.S2.3-7

Younger than 60 21 86

Borg, G. (1998). Borg’s perceived exertion and pain scales. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

60 or older 11 96 Brassil, K.J., Szewczyk, N., Fellman, B., Neumann, J., Burgess, J., Urbauer, D., & LoBiondo-

Wood, G. (2014). Impact of an incentive-based mobility program, “Motivated and Moving,”

Gender

on physiologic and quality of life outcomes in a stem cell transplant population. Cancer

Male 20 95 Nursing, 37, 345–354. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182a40db2

Cohen, M.Z., Rozmus, C.L., Mendoza, T.R., Padhye, N.S., Neumann, J., Gning, I., . . . Cleeland,

Female 13 80

C.S. (2012). Symptoms and quality of life in diverse patients undergoing hematopoietic

HSCT—hematopoietic stem cell transplantation stem cell transplantation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 44, 168–180. https://

Note. The adherence rate was defined as the number of exercises performed during a doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.08.011

session divided by the total number of exercises prescribed. A maximum of 11 exercises

could be prescribed. Copelan, E.A. (2006). Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. New England Journal of

Medicine, 354, 1813–1826. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra052638

102 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CJON.ONS.ORG

D’Souza, A., & Zhu, X. (2016). Current uses and outcomes of hematopoietic cell transplantation Jacobsen, P.B., Le-Rademacher, J., Jim, H., Syrjala, K., Wingard, J.R., Logan, B., . . . Lee, S.J. (2014).

(HCT): CIBMTR summary slides. Retrieved from https://www.cibmtr.org/ReferenceCenter/ Exercise and stress management training prior to hematopoietic cell transplantation: Blood

SlidesReports/SummarySlides/pages/index.aspx and Marrow Transplant Clinical Trials Network (BMTCTN) 0902. Biology of Blood and Marrow

Doig, G.S., & Simpson, F. (2005). Randomization and allocation concealment: A practical guide Transplantation, 20, 1530–1536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.05.027

for researchers. Journal of Critical Care, 20, 187–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrc.2005 Jim, H.S., Sutton, S.K., Jacobsen, P.B., Martin, P.J., Flowers, M.E., & Lee, S.J. (2016). Risk factors

.04.005 for depression and fatigue among survivors of hematopoietic cell transplantation. Cancer,

Gielissen, M.F., Schattenberg, A.V., Verhagen, C.A., Rinkes, M.J., Bremmers, M.E., & Bleijenberg, 122, 1290–1297. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29877

G. (2007). Experience of severe fatigue in long-term survivors of stem cell transplantation. McNeely, M.L., Dolgoy, N., Al Onazi, M., & Suderman, K. (2016). The interdisciplinary rehabil-

Bone Marrow Transplantation, 39, 595–603. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bmt.1705624 itation care team and the role of physical therapy in survivor exercise. Clinical Journal of

Haas, B.K., Hermanns, M., & Kimmel, G. (2016). Incorporating exercise into the cancer treat- Oncology Nursing, 20(Suppl. 2), S8–S16. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.S2.8-16

ment paradigm. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(Suppl. 2), S17–S24. https://doi Morrison, E.J., Ehlers, S.L., Bronars, C.A., Patten, C.A., Brockman, T.A., Cerhan, J.R., . . . Gastin-

.org/10.1188/16.CJON.S2.17-24 eau, D.A. (2016). Employment status as an indicator of recovery and function one year after

Hacker, E.D., Collins, E., Park, C., Peters, T., Patel, P., & Rondelli, D. (2017). Strength training hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 22,

to enhance early recovery after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biology of 1690–1695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.05.013

Blood and Marrow Transplantation, 23, 659–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j Musanti, R., & Murley, B. (2016). Community-based exercise programs for cancer survivors. Clinical

.bbmt.2016.12.637 Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(Suppl. 2), S25–S30. https://doi.org/10.1188/16.CJON.S2.25-30

Hacker, E.D., Fink, A.M., Peters, T., Park, C., Fantuzzi, G., & Rondelli, D. (2017). Persistent fatigue Persoon, S., Kersten, M.J., van der Weiden, K., Buffart, L.M., Nollet, F., Brug, J., & Chinapaw, M.J.

in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation survivors. Cancer Nursing, 40, 174–183. https:// (2013). Effects of exercise in patients treated with stem cell transplantation for a hemato-

doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0000000000000405 logic malignancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treatment Reviews, 39,

Hacker, E.D., Larson, J., Kujath, A., Peace, D., Rondelli, D., & Gaston, L. (2011). Strength training 682–690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.01.001

following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer Nursing, 34, 238–249. https:// van Haren, I.E., Timmerman, H., Potting, C.M., Blijlevens, N.M., Staal, J.B., & Nijhuis-van der

doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181fb3686 Sanden, M.W. (2013). Physical exercise for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell

Hacker, E.D., Larson, J.L., & Peace, D. (2011). Exercise in patients receiving hematopoietic stem transplantation: Systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials.

cell transplantation: Lessons learned and results from a feasibility study. Oncology Nursing Physical Therapy, 93, 514–528. https://doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20120181

Forum, 38, 216–223. https://doi.org/10.1188/11.ONF.216-223 Wang, J.B., Cadmus-Bertram, L.A., Natarajan, L., White, M.M., Madanat, H., Nichols, J.F., . . .

Hope, A. (2016). A survivor’s perspective on the power of exercise following a cancer diagnosis. Pierce, J.P. (2015). Wearable sensor/device (Fitbit One) and SMS text-messaging prompts

Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 20(Suppl.), S31–S32. https://doi.org/10.1188/16 to increase physical activity in overweight and obese adults: A randomized controlled trial.

.CJON.S2.31-32 Telemedicine and e-Health, 21, 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0176

CJON.ONS.ORG VOLUME 22, NUMBER 1 CLINICAL JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY NURSING 103

You might also like

- Nop2 10 2877Document9 pagesNop2 10 2877Oncología CdsNo ratings yet

- Ijcri 1001209201412 MalothDocument10 pagesIjcri 1001209201412 MalothFirah Triple'sNo ratings yet

- Revised Global Consensus Statement On Menopausal Hormone TherapyDocument4 pagesRevised Global Consensus Statement On Menopausal Hormone TherapyluishelNo ratings yet

- Owen 2013Document9 pagesOwen 2013Yacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- Acute-Phase Response Following Full-Mouth Versus Quadrant Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment: A Randomized Clinical TrialDocument10 pagesAcute-Phase Response Following Full-Mouth Versus Quadrant Non-Surgical Periodontal Treatment: A Randomized Clinical TrialValeria ParraNo ratings yet

- High Intensity Interval Training For Hypertension .9Document7 pagesHigh Intensity Interval Training For Hypertension .9Leticia N. S. NevesNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1470204520306665 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S1470204520306665 MainshangrilaNo ratings yet

- Letter To The Editor: Antibiotic Prophylaxis Regimens in Trauma and Orthopaedic SurgeryDocument3 pagesLetter To The Editor: Antibiotic Prophylaxis Regimens in Trauma and Orthopaedic SurgerytanyasisNo ratings yet

- 5 4 Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine In.20Document6 pages5 4 Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine In.20Carlyna Septi AisyaNo ratings yet

- Pain Management & MedicineDocument6 pagesPain Management & MedicinelinggaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Artificial Nutrition OnDocument12 pagesImpact of Artificial Nutrition OnKabomed QANo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Prophylaxis in The Surgical ManagementDocument7 pagesAntibiotic Prophylaxis in The Surgical ManagementRAHUL SHINDENo ratings yet

- De Leo November 2023 ONFDocument16 pagesDe Leo November 2023 ONFfitrimaNo ratings yet

- Enteral FeedingDocument5 pagesEnteral Feedingricardo arreguiNo ratings yet

- Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesSystematic ReviewNaren GangadharanNo ratings yet

- Nurse Education Today: Kyoungja Kim, Insook Lee TDocument6 pagesNurse Education Today: Kyoungja Kim, Insook Lee TRAQUEL BRITONo ratings yet

- Module 2 PDFDocument23 pagesModule 2 PDFRui ViegasNo ratings yet

- 3356-Article Text-5117-1-10-20211130Document5 pages3356-Article Text-5117-1-10-20211130dkhatri01No ratings yet

- Surgical Site InfectionsDocument5 pagesSurgical Site Infectionsapi-320469090No ratings yet

- Total Marrow Irradiation: A Comprehensive ReviewFrom EverandTotal Marrow Irradiation: A Comprehensive ReviewJeffrey Y. C. WongNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Chronic Skin Wounds and Their Risk.10Document10 pagesPrevalence of Chronic Skin Wounds and Their Risk.10Ima KholaniNo ratings yet

- Ovarian CancerDocument17 pagesOvarian CancerVinitha DsouzaNo ratings yet

- Development of A Risk Stratification Test in EEIIDocument10 pagesDevelopment of A Risk Stratification Test in EEIICamilo Basualto CastilloNo ratings yet

- Uji Klinis 4Document9 pagesUji Klinis 4Verliatesya TugasNo ratings yet

- 3 ING (Yoga, CBT, Versus Education To Improve Quality of Life and Reduce Healthcare Costs in People With Endometriosis) PDFDocument7 pages3 ING (Yoga, CBT, Versus Education To Improve Quality of Life and Reduce Healthcare Costs in People With Endometriosis) PDFAzucenaNo ratings yet

- ProfilaksisDocument4 pagesProfilaksisLatifah MaharaniNo ratings yet

- PIIS0140673616309461Document9 pagesPIIS0140673616309461Jose Angel BarreraNo ratings yet

- Promotility Agents For The Treatment of Ileus In.38 PDFDocument13 pagesPromotility Agents For The Treatment of Ileus In.38 PDFRendi ER PratamaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of PLGA In-Situ Forming ImplantsDocument21 pagesAn Overview of PLGA In-Situ Forming ImplantsthanaNo ratings yet

- GrowthFactors201028p 111-6Document7 pagesGrowthFactors201028p 111-6endyjuliantoNo ratings yet

- SR Diabetic Foot UlcerDocument11 pagesSR Diabetic Foot UlcerDeka AdeNo ratings yet

- Effects of Back Massage On Chemotherapy-Related Fatigue and Anxiety: Supportive Care and Therapeutic Touch in Cancer NursingDocument8 pagesEffects of Back Massage On Chemotherapy-Related Fatigue and Anxiety: Supportive Care and Therapeutic Touch in Cancer NursingFauzul AzhimahNo ratings yet

- Cancer Regional Therapy: HAI, HIPEC, HILP, ILI, PIPAC and BeyondFrom EverandCancer Regional Therapy: HAI, HIPEC, HILP, ILI, PIPAC and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Trismus Xerostomia and Nutrition Status PDFDocument9 pagesTrismus Xerostomia and Nutrition Status PDFAstutikNo ratings yet

- Lee 2010Document11 pagesLee 2010Gabriella Kezia LiongNo ratings yet

- Bailey (2020)Document9 pagesBailey (2020)Nerea AlvarezNo ratings yet

- First-Year Follow-Up of Newborns Operated For EsopDocument7 pagesFirst-Year Follow-Up of Newborns Operated For EsopPhilippe Ceasar C. BascoNo ratings yet

- Molecules: Drug Delivery Systems of Natural Products in OncologyDocument23 pagesMolecules: Drug Delivery Systems of Natural Products in OncologyrollandoNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Nurses' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers Towards Pressure Injuries PreventionDocument6 pagesCritical Care Nurses' Knowledge, Attitudes, and Perceived Barriers Towards Pressure Injuries PreventionzaynmalikNo ratings yet

- Critique Article Group 2Document6 pagesCritique Article Group 2Fouzia GillNo ratings yet

- Comparative Gonadotoxicity of The Chemotherapy DruDocument12 pagesComparative Gonadotoxicity of The Chemotherapy Druأحمد علي حبيبNo ratings yet

- Critical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyDocument10 pagesCritical Reviews in Oncology / HematologyLiterasi MedsosNo ratings yet

- Effect of Covid On OrthoDocument9 pagesEffect of Covid On OrthoDebangshu KumarNo ratings yet

- Drug Study: West Visayas State UniversityDocument2 pagesDrug Study: West Visayas State Universityw dNo ratings yet

- Health Resource Utilization and Medical Care Cost of Acute Care Elderly Unit PatientsDocument7 pagesHealth Resource Utilization and Medical Care Cost of Acute Care Elderly Unit Patientspintoa_1No ratings yet

- Comparison of The Effect of Three Treatment Interventions For The Control of Meniere 'S Disease: A Randomized Control TrialDocument6 pagesComparison of The Effect of Three Treatment Interventions For The Control of Meniere 'S Disease: A Randomized Control Trialian danarkoNo ratings yet

- Grosse-Sundrup2012 Score PredictifDocument2 pagesGrosse-Sundrup2012 Score PredictifZinar PehlivanNo ratings yet

- Bochner 2003Document13 pagesBochner 2003nimaelhajjiNo ratings yet

- Case Study (1) 1: Patient ProfileDocument8 pagesCase Study (1) 1: Patient ProfileYaser Zaher0% (1)

- Disaster Rehabilitation Response Plan: Now or NeverDocument8 pagesDisaster Rehabilitation Response Plan: Now or NeverAgus SGNo ratings yet

- BJR 11 171Document9 pagesBJR 11 171David SadigurskyNo ratings yet

- Challenges in Making A Business Case For Effective Pain Management in Nursing HomesDocument12 pagesChallenges in Making A Business Case For Effective Pain Management in Nursing HomeslemootpNo ratings yet

- Bladder Cancer (NMBC)Document1 pageBladder Cancer (NMBC)alex amcNo ratings yet

- Harm Worksheet: CitationDocument3 pagesHarm Worksheet: CitationDavid PakpahanNo ratings yet

- Johnson 2017Document4 pagesJohnson 2017febrian rahmatNo ratings yet

- Jadp 07 339Document4 pagesJadp 07 339Marden OcatNo ratings yet

- Prochaska JO Velicer The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior PDFDocument11 pagesProchaska JO Velicer The Transtheoretical Model of Health Behavior PDFClaudio M. Cruz-FierroNo ratings yet

- Implantes en InmunosuprimidosDocument8 pagesImplantes en InmunosuprimidosLeandro PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Urinary Tract Infection in Male VeteransDocument7 pagesUrinary Tract Infection in Male VeteransJave GajellomaNo ratings yet

- Joacp 35 5Document9 pagesJoacp 35 5faundraNo ratings yet

- Administering Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Injections CANVASDocument54 pagesAdministering Intramuscular and Subcutaneous Injections CANVASAinaB ManaloNo ratings yet

- Level Worksheet: 2 DripDocument3 pagesLevel Worksheet: 2 DripDiksha AhluwaliaNo ratings yet

- Vision ProvidersDocument18 pagesVision ProvidersherndonNo ratings yet

- Medical College Choices 08 NovDocument1 pageMedical College Choices 08 NovamitNo ratings yet

- Kel 5 Roleplay Past TenseDocument5 pagesKel 5 Roleplay Past TenseDesma LindaNo ratings yet

- Concept of HealthDocument2 pagesConcept of Healtharzubin fiza100% (1)

- Department of HealthDocument2 pagesDepartment of HealthdenNo ratings yet

- 2023 Job Vacancies Template DOLEDocument3 pages2023 Job Vacancies Template DOLEcarlo velascoNo ratings yet

- Fake News About CovidDocument5 pagesFake News About Covidrocyn benamerNo ratings yet

- CertificateDocument1 pageCertificateShravani DongreNo ratings yet

- WPSD - Medication Harm 2022Document17 pagesWPSD - Medication Harm 2022PMKP RSKBRNo ratings yet

- An Insight Into Indian Healthcare ServicesDocument66 pagesAn Insight Into Indian Healthcare ServicesKarthikeyan GanesanNo ratings yet

- Naga City Is Galing Pook 2018 AwardeeDocument2 pagesNaga City Is Galing Pook 2018 AwardeeMarvin CabantacNo ratings yet

- English 1 Q3 M3 Answer SheetsDocument2 pagesEnglish 1 Q3 M3 Answer SheetsARLENE TOLENTINONo ratings yet

- Medical CV Examples UkDocument5 pagesMedical CV Examples Ukphewzeajd100% (2)

- Jurnal ATSPPHDocument10 pagesJurnal ATSPPHNova SafitriNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing and Treating Latent TB Infection (LTBI) : Module 14 - March 2010Document38 pagesDiagnosing and Treating Latent TB Infection (LTBI) : Module 14 - March 2010wisnu kuncoroNo ratings yet

- End of Life CareDocument18 pagesEnd of Life CareselvarajNo ratings yet

- Tantangan Dan Solusi Pendidikan Keperawatan Pada Masa Pandemi Covid 19 Di Indonesia (Tinjauan Literatur) Ade Suryaman Ismail Fahmi Amelia GanefiantyDocument4 pagesTantangan Dan Solusi Pendidikan Keperawatan Pada Masa Pandemi Covid 19 Di Indonesia (Tinjauan Literatur) Ade Suryaman Ismail Fahmi Amelia Ganefiantyreditaelok winantiNo ratings yet

- Chapter Three Research MethodologyDocument7 pagesChapter Three Research MethodologyNejash Abdo IssaNo ratings yet

- Sometimes A Simple Change Isn't So SimpleDocument9 pagesSometimes A Simple Change Isn't So SimpleRembrandtNo ratings yet

- Classification of DrugsDocument3 pagesClassification of DrugsChianlee CarreonNo ratings yet

- Department of Psychiatric Nursing Faculty of Health Studies Brandon University Integrative Clinical Practicum 69:442Document14 pagesDepartment of Psychiatric Nursing Faculty of Health Studies Brandon University Integrative Clinical Practicum 69:442ENo ratings yet

- Discussion Report Form 2 - Group C - PBL 1Document3 pagesDiscussion Report Form 2 - Group C - PBL 1Irma NareswariNo ratings yet

- Joel Paris-The Intelligent Clinician's Guide To The DSM-5®-Oxford University Press (2013)Document265 pagesJoel Paris-The Intelligent Clinician's Guide To The DSM-5®-Oxford University Press (2013)JC Barrientos100% (9)

- Do Not Use AbbreviationsDocument6 pagesDo Not Use AbbreviationsgerajassoNo ratings yet

- ICN Framework - Disaster Mitigation & PrepDocument7 pagesICN Framework - Disaster Mitigation & PrephaslindamayasariNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Human Resource Planning AT VDCDocument65 pagesProject Report On Human Resource Planning AT VDCNagireddy Kalluri100% (1)

- Abdominal Ultrasound For Pediatric Blunt Trauma FAST Is Not Always BetterDocument3 pagesAbdominal Ultrasound For Pediatric Blunt Trauma FAST Is Not Always BetterInryuu ZenNo ratings yet

- Advancing Digital Health FDA Innovation During COVID-19Document3 pagesAdvancing Digital Health FDA Innovation During COVID-19Lucien DedravoNo ratings yet