Professional Documents

Culture Documents

S14Ethics of Bhagavad Gita and Kant

S14Ethics of Bhagavad Gita and Kant

Uploaded by

jose rodriguezCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

S14Ethics of Bhagavad Gita and Kant

S14Ethics of Bhagavad Gita and Kant

Uploaded by

jose rodriguezCopyright:

Available Formats

The Ethics of the Bhagavadgita and Kant

Author(s): S. Radakrishnan

Source: International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 21, No. 4 (Jul., 1911), pp. 465-475

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2376569 .

Accessed: 06/01/2014 13:56

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

International Journal of Ethics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BHAGAVADGITA AND KANT. 465

ness, and it is to this ever-evolvingand developingcon-

ciousness,-withfullopportunities givento it to manifest

its life at its best,-thatwe mustlook forthe emergence

of those highertypeswhichthis secretand mysterious

realmholds withinits illimitabledomain.

It willbe obvious,I think,fromthispaper,thattheDar-

winiantheoryof evolutionhas enrichedthewholefieldof

ethicalstudy. It has broughtnewethicalproblemsto our

noticeandhas shownhowintimately connectedthescience

of ethicsis withevolutionary thought.Whetherour indi-

vidual standpointis naturalisticor spiritualistic,

we can-

notbut expressour indebtedness to thelaborsof the evo-

lutionists,and join handstogetherin theworkofendeavor-

ing to solve the problemswhichthis great upheaval of

thoughthas broughtmorefullyand clearlyintothelight

of day. The cause of ethicalprogressis a platformon

whichall can meet.

RAMSDEN BALMFORTH.

CAPE ToWN.

THE ETHICS OF THE BHAGAVADGITA AND

KANT.

S. RADAKRISHNAN.

MUCH has been made of the apparentsimilarity

betweenthe ethical systemsof the Bhagavadgita

and Kant, the criticalphilosopher. To the superficial

reader,thesimilarity is no doubtstriking.Both systems

preach againstthe rule of the senses; both are at one

in holdingthat the moral law demandsdutyfor duty's

sake. In spite of the agreementsbetweenthe two sys-

tems,however,sober secondthoughtwill disclosediffer-

encesof greatmoment.In the presentarticle,thewriter

has neitherthe space, nor is he competent, to make a

criticalstudyof the two systems. All thathe can hope

to do, is to lay bare thepracticalside of theVedantasys-

tem,or, moreaccurately, the Bhagavadgita,and to com-

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

466 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ETHICS.

pare its teachingwiththat of Kant on the fundamental

questionsof free will, the moral problem,and the law

of duty.

In the Vedanta system,religion,metaphysics,and

ethicsare so closelyboundup, one withanother,thatit

is difficult

for us to separate them. One can, however,

state,withoutfear of contradiction,

thatthe elementsof

a scienceof ethics,thoughnot a perfectedsystem,are to

be foundthere. The main questionsand topics of dis-

pute are the same as those whichoccupythe!attention

of the westernmoralists. Hedonismand rationalism, in

all theirvarieties,struggle'forsupremacy. The Katha

Upanishad declaresin unambiguous'language, that the

good or the ethicalideal oughtnot to be identified

with

pleasure: "The good is one thing,thepleasantanother;

these two, having differentobjects, chain a man. It is

well with him who clings to the good; he who chooses

the pleasant,misseshis end."'

Ethics,in theVedantasystem,appears in thephenom-

enal realm,or the sphereof relativity.Reality,accord-

ing to the Vedanta,has two aspects,the higherand the

lower,the fixedand the changing,the absoluteand the

relative. The higheraspect of realityis Brahman,the

unconditioned, and perfect. The lower aspect,

infinite,

or the universe,appears and disappears,in turns,in the

higher reality of Brahman. The theory does not deny

the realityof the world or the individual souls in it. The

plurality of individual souls and the material universe

are not 'real' in the absolutesenseof theword,for they

are subject to change. They are only relativelyreal.

Ethics belongsto thisworld,whichis real for all prac-

tical purposes. The late Professor Max Muller says: "For

all practical purposes, the Vedantist would hold that the

whole phenomenalworld, both in its objective and sub-

jective character, should be accepted as real. It is as

1Max Miuller," The Upanishads," p. 8 (Sacred Books of the East Series,

Vol. XV).

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BHAGAVADGITA AND KANT. 467

real as anythingcan be to the ordinarymind. It is not

mere emptiness,as the Buddhists maintain." 2

But it may seem to some that the very conception of

the ethics of the Bhagavadgita is impossible, since it is

incompatible with a belief in the doctrine of karma..

What is the use of teaching and preaching about duty

if a man's predeterminedconditionrendershim incapable

of profitingby the counsel? 'What is the use of applying

moral judgments,if man's actions do not represent his

character? Freedom of the will is the fundamental

postulate of morality,withoutwhich the moral life loses

its integrity. Plainly, there can be no such thing as

Vedanta ethics. This idea is expressed in the tersestand

most extreme terms by Hegel, one of the greatest of

the world's philosophers,when he says: "No morality,

no determinationof freedom,no rights,no duties have

any place here; so that the people of India are sunk in

completeimmorality."

But the cautious reader of the Bhagavadgita will find

that the real meaning of karma.does not exclude free will.

In a verse of that famous book we findit said: "Every

sense has its affectionsand aversions to its objects fixed;

one should not, become subject to them, for they are

one's opponents."8 The law of karma, or necessity,is

true. Every action will be followedby its proper result;

every cause has an effect. Our actions in our past life

have resulted in certain fixed tendencies, which are

termed 'affections' and 'aversions.' A Nyaya aphorism

declares that "our actions, though apparently disappear-

ing, remain, unperceived, and reappear in their effects

as tendencies" (pravrittis). But we must not become

'subject ' to them. We are, so to say, tempted to act

according to these tendencies; but we must not allow

themto have their own way; we must not surrenderour-

2Max Miller, "The Vedanta Philosophy,"p. 161.

8

I I Bhagavadgita,

" p. 56. Referencesare to Telang's translationin

Sacred Books of the East Series.

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

468 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ETHICS.

selves to the senses, throughwhich alone the tendencies

show themselves.

Karma, thus,is a name for the sumtotalof the tenden-

cies with which a man is born; along the lines marked

out for him by his inner nature and outer circumstances,

man has to develop a character,good or bad. The uni-

versal of law of karma has nothing to do with the real

man, if he understandswhat is his real nature. We have

to throwoffthe yoke of the passions and rise to rational

freedom; in exercisingthe power of reason to subjugate

the senses, or the given element,man is free. To adopt

a metaphor,wind and tide have to be controlledby the

steersman's mind; that is, he has to make use of them

and see to it that they will carry him to his goal. But,

it is urged, should they prove too strong,what is he to

do? In spite of the best intentions,owing to the "nig-

gardly provisionof a stepmotherly nature," calamitymay

overtake us. Carve as we will the mysteriousblock of

which our life is made, the dark vein of'destiny again

and again appears in it. The force of this objection is

much weakened by the fact that, accQoxihgto the Gitaic

ideal, virtue consists,not so much in the achievementof

any externalresults,qs in the noble bearing of the agent

amidst the vicissitudesand accidents of fortune. We are

asked to do our duty without caring for the results.

"Blessed are the pure in heart." The soul, though it

may be opposed in the realization of its volitionby many

untoward occurrences,would still shine,like Kant's will,

"by its own light, as a thing which has its whole value

in itself." 4

This reconciliationof freedom and necessity is some-

times considered to be identical with Kant's, solution of

the same problem. With Kant, freedomis a matter of

inference. SIn the "Principles of the Metaphysics of

Ethics" he says: "Freedom, however, we could not

'lKant's "Principles of the Metaphysicsof Ethics" (Abbott's transla-

IP. 11.

tion),

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BHAGAVADGITA AND KANT. 469

proveto be actuallya propertyof ourselves,or of human

nature; only,we saw, that it mustbe presupposed,if

we wouldconceivea beingas rational,and consciousof

its causalityin respectof its actions,i. e., as endowed

witha will" (p. 81). All thatwe knowis thatwe have

such a thingas an absolutelyobligatoryor categorical

judgment: I oughtto act in such and such a way, re-

gardless of my inclinations.Thou oughtest; therefore

thou canst. But if we regard ourselvesas free agents,

how shall we avoid laying ourselvesopen to criticism

fromthe scientificsphere? The foundationof science

is the law of universalcausality,whichwe oughtnot to

violate. Some way to hold conjointlybothfreedomand

necessitymustbe devised; or else our mentalhousewill

be dividedagainstitself.

Kant holdsthatman is bothdetermined and free; de-

termined, with regard to his relationsas a memberof

the phenomenalrealm,and free,withregard to his re-

lationsas a memberof the noumenalrealm. The same

act is determined whenregardedas belongingto the em-

pirical series,and free whenwe considerit due to the

underlying cause, the noumenon.Freedom,therefore, is

vestedin man,thenoumenon;thecause is noumenal,the

effectphenomenal. The empiricalseries of antecedents

and consequentsis but the phenomenon of the noumenal

self.

What shallwe say by way of a relativeestimateof the

two theories? What have the two systemsin common?

To thequestionof determinism or freedom,'both systems

reply,determinism and freedom;but the similarityends

there. On ultimateanalysis,we findthatKant offersus

only the semblanceof freedom'and not the realityof

it. Moral relationsexist in the phenomenalrealm; and

there,accordingto Kant, it is necessitythat rules. Be-

sides, Kant'Is'solutionseems only anotherformof de-

terminism.If theempiricalchainof antecedents and con-

sequentsis but the phenomenon of the noumenalself,it

is plain that it cannotbe otherthan it is. On such a

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

470 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ETHICS.

theory,moral regenerationand moral progress seem out

of place. As Schurman remarks: "That Judas betrayed

Christ, neitherhe himself,nor any other creature could

have prevented; nevertheless,the betrayal was not a

necessity,but 'an act of perfect freedom."5 The free-

domrwhichKant offersus is thus emptyand unreal. The

solution offered by the Vedanta theory gives us real

freedom,freedom even in the phenomenal realm, where

we are powerful enough to check our impulses, to resist

our passions, and lead a. life of satisfiedselfhoodin which

the lower passions are regulatedby reason.

Let us next turnour attentionto the originof the moral

problem and the law of morality. The opening section

of the Bhagavadgita indicates to us that the problem of

morality arises only when there is a conflictbetween

reason and sense, duty and inclination. Had Arjuna been

mere reason, therecould have been no Bliagavadgita. If,

on the other hand, he had been mere sensibility,what

would have been the occasion for it? It is because he

was dominated by both sensibility and reason, and be-

cause, there was a perpetual conflictbetween them,that

we have the Gita. In spite of all his knowledge,prowess,

and other admirable'qualities, Arjuna is just an ordinary

mortal, endowed, among other things,with both reason

and sense. Fully convinced of the righteousnessof his

cause, he comes to the battlefieldof Kurukshetra, pre-

pared to meet the enemy and fight to the bitter'end.

Taking a position between the hostile ranks, whom does

he behold? The flower and choice nobility of Indian

chivalrydrawn up in the order of battle. Looking at the

beautiful array of-troops in his front,all come to fight.

in this civil war in which every man's hand was to be

turned against his brother's, Arjuna, smitten with de-

spondency,flingsaway his arms and falls down. He cares

not for victory,throne,wealth, or glory, for they have

to be purchased at a great cost. They have to be won

5" Kantian Ethics and the Ethics of Evolution.," p. 7.

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BRAGAVADGITAAND KANT. 471

by profaningthe religiousrites,by destroyingso many

of God's children,by the regular slaughterof one's

nearest and dearest. Arjuna, in deep distressand de-

spair,exclaims:

I do not wish for victory,0 Krishna! Nor sovereignty,

nor pleasure.

to us, 0 Govinda! What enjoyments,

What is sovereignty and even life,

Even thoseforwhosesake we desiresovereignty,

enjoyments,and pleasures,

are standing here for battle, abandoning life and wealth. . . . It is not

proper for us to kill our own kinsmen. . . . For how, 0 Madhaval shall

we be happy,afterkillingour ownrelatives?8

Arjuna had cometo thebattlefield thinking thatit was

his religiousdutyto fightuntothe verydeath; but now

the claims of blood and friendshipassert themselvesin

him. Lowerpassionsstruggleforthemastery,and doubt

divideshis mind. And to quell the qualms of an edu-

cated conscience,scripturaltexts are quoted. Be the

cause'as righteousas it may,the eternallaw whichde-

clares,Thou shaltdo no murder,has to be violated. Bet-

terwereit,then,to die thanto fightagainstpart of one's

ownnature.

Here is a situation,a most critical-one, requiringa

solution. Reasonstands againstsense; dutyis opposed

to inclination.Arjuna refersthe matterto Krishna,his

divineguide: "With a heart contaminated by the taint

of helplessness,witha mindconfoundedas to my duty,

I ask you to tell me what is assuredlygood for me. I

am yourdisciple. Instructme who have thrownmyself

on yourindulgence."'>7Krishna asks Arjuna to be of

good cheerand fight. He says: There is no cause for

grief: you cannotkill or' be killed,for you and your

relativesare all immortalsouls,and thoughthe bodybe

slain in the performanceof your dutiesin life,you and

theyare, in essence,indestructible.If you shirkfrom,

or declineto do, yourduty,you will sin. And, besides,

you can neverbe actionless.by shunningaction. Life is

actionand actionmustgo on. Comegood or evil,wealth

or poverty,do yourdutyregardlessof results.

I"Bhagavadgita," pp. 40, 41. 7 " Bhagavadgita," p. 43.

Vol. XXI.-No. 4. 31

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

472 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ETHICS.

Therefore,arise, thou son of KuntiI brace

Thine arm for conflict,nerve thy heart to meet

As thingsalike to thee-pleasureor pain,

Profitor ruin,victoryor defeat;

So minded,gird thee to the fight; for so

Thou shalt not sin.8

The demands of the lower self, or sense, have to be

subordinatedto the dictates of reason.

The case of Arjuna is typical of what is taking place

every minute of our lives. It expresses what every one

of us has often felt, it points out to us how our moral

life is, after all, a conflictbetween duty and inclination,

a struggle between reason and sense, and impressively

instillsinto our minds the great truth,that moralitycon-

sists in doing one's duty. What is the battlefield of

Kurukshetra if it is not the battlefieldof life? Who is

Arjuna if he is not an ordinary mortal endowed with

both reason and sense? Who are the Kauravas and others

standingin array before Arjuna if theyare not the lower

passions and temptations? Who is Krishna if he is not

the voice of God echoing in every man? Each one of

us stands in the battlefieldof life,in his chariot of mortal

fleshdrawn by the horses of his passions and sense facul-

ties. These faculties, according to the ethics of the

Bhagavadgita, are to be controlledand intelligentlyguided

by reason and are not to be allowed to carry him to the

abysmal depthsof ruin.

Kant declares that the problem of moralityarises only

for beings in whom there is a conflictbetween duty and

8 Edwin Arnold, " The Song Celestial, " p. 16. Compare: " You have

grieved for those who deserve no grief, and you talk words of wisdom-

learned men grieve not for the living nor the dead-never did I not exist,

nor you, nor these rulers of men; nor will any one of us ever hereafter

cease to be ... therefore do engage in battle. . . . He who thinks to be

the killer and he who thinks to be killed, both know nothing.. . . There-

fore you ought not to grieve for any being. Having regard to your own

duty also, you ought not to falter. .. . . But if you will not fight this

righteous battle, then you will have abandoned your own duty"

("Bhagavadgita," pp. 43-47).

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

BHAGAVADGITAAND KANT. 473

inclination,menin whomreasonand sensestandopposed.

Were we completely membersof the rationalworld,our

actionswouldtallywiththelaw of reasonor duty. And

again,if we weremerelymembersof theworldof sense,

our actionswould take place accordingto the laws of

sense,and couldneverbe made to conform to duty. "If,

therefore, I were onlya memberof the worldof under-

standing,thenall myactionswouldperfectly conformto

the principlesof autonomyof pure will; if I were only

a part of the worldof sense,theywould necessarilybe

assumedto conformwhollyto thenaturallaw of desires

and inclinations"(Kantls Ethics,page 7).

Thuswe findthatboththeBhagavadgitaand Kant hold

betweenduty and inclinationis the es-

that the conflict

sentialruleofmorality, and thesuppressionof inclination

by duty,theconditionof moralworth. Thoughmenmay

agree to differon thispoint,it is, nonetheless,truethat

onlyin such-a conflict can true moral characterbe re-

vealed. As ProfessorPaulsen has said: "Where there

has neverbeen a conflictbetweeninclinationand duty,

wherethewill has neverhad an opportunity of deciding

againstinclinationand for duty,the characterhas not

beentested."

Turningour attentionto the moral law, we findthat

bothGita and Kant preachdutyforduty'ssake. "Your

businessis withactionalone,notby anymeanswithfruit.

Let not the fruitof actionbe your motiveto action."9

"That an actiondonefromduty,derivesits moralworth,

not fromthe purposewhichis to be attainedby it, but

fromthemaximby whichit is determined, and therefore

does not dependon the realizationof the object of the

action,but merelyon the principleof volition,by which

the actionhas takenplace, withoutregardto any object

of desire."10 Thus accordingto both Gita and Kant,

the highesttype of moralityconsistsin doing duty for

"' Bhagavadgita," p. 48.

'Abbott's translation of Kant's Ethics, p. 19.

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

474 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ETHICS.

duty's sake, without any personal attachment or hope

of reward. The moralman mustdo his dutysimplybe-

cause it is duty. A man's will is good, "not because of

what it performsor effects,not by its aptnessfor the

attainmentof some proposed end, but simply by virtue

of the volition,i. e., it is good in itself." 1

Thus far the two systemsare agreed; but as we pro-

ceed we findthat Kant excludes frommoral actions,

actionswhichare consistent withduty,but yet are done

frominclination.A traderis honestfromgood policy;

a man preserveshis life 'as dutyrequires'and not 'be-

cause dutyrequires.' "It is a dutyto maintainone's life;

and, in addition,everyone has also a directinclination

to do so. But on this account,the oftenanxious care

whichmostmen take for it, has no intrinsicworth,and

theirmaximhas no moral import. They preservetheir

life, as duty requires, no doubt,but not because duty

requires." 12 Acts donefrominclination, are not,accord-

ingto Kant,moral. It is a defectof Kant's ethicaltheory

thathe conceivesan act of dutyas positivelyindifferent,

nay,disagreeableto the senses. He even definesdutyas

"compulsionto a purposeunwillingly adopted."

The Gita ethics,on the otherhand, does not ask us

to destroytheimpulses,but asks us onlyto controlthem,

to keep themin theirproperorder,to see thattheyare

always subordinatedto and regulatedby reason. By a

life of reason the Gita ethicsdoes not mean a passion-

less life,butone in whichpassionis transcended." Great

are thesenses; greaterthanthe sensesis themind; and

greaterthanthemindis theunderstanding." 13 Though

the Gita ethics does not enjoin upon us the complete

eradicationofthesensuousimpulses,thedemandfortheir

controlis so insistentas to lead us to thinkthatit also

advocatestheirtotal suppression.

How shall we explainthis outcryagainstthe senses

The Vedantadoes scorntheswayof thesenses. The Ve-

t Ibid., p. 11. " P. 16. 13Telang 's translation, p. 57.

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE UNWRITTENDOUBLE STANDARD. 475

dantin fliesfromsensuouspleasure in everyform,not

because it is sinfulin itself,but becauseit is too apt to

endangerthe soul by fettering it to thatwhichis earthly

and perishable. "Pleasure," says ProfessorPaulsen in

his description of theChristianconception of life,."is the

bait withwhichthe devil ensnaresthe soul to chainit to

the world." Things of the earth are the burdensthat

weighus down and crush our hearts. Every great re-

ligious teacherhas taughtthis importanttruth. Jesus

rightlyperceivedthat it was easier for a camel to go

throughthe eye of a needlethanfora richman to enter

intothekingdomofGod. Wealthalienatesus fromGod.1

But thisdoesnotmeanthatwe mustlive a lifeof passion-

less quietism. We are not asked to uprootall desires;

for that would implythe cessationof all activity. But

life is actionand actionmustgo on. The Vedanta does

not see any evil in the earthlylife as such. It does not

ask us to withdrawfromthe ordinarypursuitsof life;

but it does ask us to renouncethe luxuriesof life. We

are asked to live the spiritualor the unworldlylife in

the world. The asceticism,if we may say so, whichis

insistedupon in the Gita ethics,is the asceticismof the

innerspiritand not of the outwardconduct.

S. RADHAKRISHNAN.

PRESIDENCY COLLEGE, MADRAS, INDIA.

THE WRITTEN LAW AND THE UNWRITTEN

DOUBLE STANDARD.

ADA ELIOT SHEFFIELD.

T HE enforcement of a law has its most far-reaching

effectin drivinghometo the publicminda moral

standard. Crude thoughthe legal distinctions between

rightand wrongmay be, they on the whole reflectthe

scruplesof the average man, and theygo to formthe

pp. 88fl).

" Paulsen's "System of Ethics" (Thilly's translation,

This content downloaded from 134.161.28.20 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 13:56:10 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5807)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- NOTA Sobre SG OCLAEDocument1 pageNOTA Sobre SG OCLAEjose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Voucher 7978100Document3 pagesVoucher 7978100jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- El Pasquìn 20Document4 pagesEl Pasquìn 20jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Secretariado General OclaeDocument4 pagesSecretariado General Oclaejose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Boletín Universidad de Los Andes No. 31 Junio 1973Document12 pagesBoletín Universidad de Los Andes No. 31 Junio 1973jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Sgaa Plan 7059 Actualizado 21 22Document1 pageSgaa Plan 7059 Actualizado 21 22jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Protocolo Prevencion Violencias GeneroDocument25 pagesProtocolo Prevencion Violencias Generojose rodriguezNo ratings yet

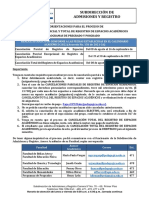

- Listado de Elegibles y Programacion de Entrevistas 2Document16 pagesListado de Elegibles y Programacion de Entrevistas 2jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Tutorial para Aplicar A Convocatoria Monitores de Investigacion 2023 IDocument12 pagesTutorial para Aplicar A Convocatoria Monitores de Investigacion 2023 Ijose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Decreto 041 de 2022Document4 pagesDecreto 041 de 2022jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- CUN/SN: 4433231002170498 Señor (A)Document2 pagesCUN/SN: 4433231002170498 Señor (A)jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Anexo 1 - Formato Postulacion Aspirantes Doctorado en EducaciónDocument8 pagesAnexo 1 - Formato Postulacion Aspirantes Doctorado en Educaciónjose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Acuerdo 173 CA Del 17 Diciembre 2021Document1 pageAcuerdo 173 CA Del 17 Diciembre 2021jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Anexo 3. FOR047GFN Autorizacion de Pago Abono en Cuenta 1Document1 pageAnexo 3. FOR047GFN Autorizacion de Pago Abono en Cuenta 1jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Acuerdo 123 CA Del 14 Diciembre 2022Document4 pagesAcuerdo 123 CA Del 14 Diciembre 2022jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Certificado Pago 45712Document1 pageCertificado Pago 45712jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Avianca - ConfirmaciónDocument4 pagesAvianca - Confirmaciónjose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Orientaciones Cancelacion Total y Parcial de RegistroDocument1 pageOrientaciones Cancelacion Total y Parcial de Registrojose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Gaceta Upn 149Document32 pagesGaceta Upn 149jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Administrador,+Gestor a+de+La+Revista,+2290 6692 1 CEDocument9 pagesAdministrador,+Gestor a+de+La+Revista,+2290 6692 1 CEjose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Análisis de La Reforma A La Ley 30 de Educación Superior de 1992Document61 pagesAnálisis de La Reforma A La Ley 30 de Educación Superior de 1992jose rodriguezNo ratings yet

- S14Ethics of Bhagavad Gita and KantDocument12 pagesS14Ethics of Bhagavad Gita and Kantjose rodriguezNo ratings yet