Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bava 2010

Uploaded by

vedit malhotraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bava 2010

Uploaded by

vedit malhotraCopyright:

Available Formats

Article

India and the International Studies

47(2–4) 373–386

European Union: © 2010 JNU

SAGE Publications

From Engagement to Los Angeles, London,

New Delhi, Singapore,

Strategic Partnership Washington DC

DOI: 10.1177/002088171104700419

http://isq.sagepub.com

Ummu Salma Bava

Abstract

Relations between India and the European Union (EU) have evolved over a long

period. Beginning in the early 1960s, with diplomatic relations being established

between India and the European Economic Community (EEC), it has expanded

and subsequently been transformed because both India and the EU (since 1992)

have assumed a growing significance in post-Cold War international politics.

However, this partnership has not been able to achieve its potential partly be-

cause of the low political visibility of the EU and strong bilateral relations between

India and major European powers. The India–EU relationship in the context of

the strategic partnership launched in 2004 has witnessed a dramatic expansion

of engagement from the economic to the political and security realms, although

the strategic partnership does not mean absence of differences and difficulties.

There is, however, a perception that India’s closeness to the US has impacted the

development of partnerships with both the EU and major individual countries.

Keywords

India–European Union relations, European security strategy, strategic partnership,

multi-lateralism, normative values

Introduction

India and the European Economic Community1 (EEC) established political rela-

tions in 1963 and this constituted another set of relations to the existing bilateral

relationships that India had with individual countries of the EEC, in particular the

Ummu Salma Bava is Professor, Centre for European Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru

University, New Delhi, and Associate Fellow, Asia Society, New York.

E-mail: usbava@gmail.com

The author wishes to thank the anonymous referees for their helpful suggestions.

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

374 Ummu Salma Bava

West European countries. India was also one of the first developing countries to

engage with this new entity that represented an organized attempt at regional inte-

gration. The major elements of India–EEC relations from the outset focused on

trade and commerce. Apart from this, India also received the highest amount of

development aid among all Asian and Latin American countries from the European

Community (EC).

Incremental steps that, over the years, have elevated the relationship from

commercial and trade relations to political cooperation marked India’s relations

with the EC. In 1971, the EEC introduced the general tariff preferences for ninety-

one developing countries, including India, under the Generalized System of

Preferences (GSP) scheme. This was followed by India and the EEC signing the

Commercial Cooperation Agreement in 1973. In 1981, India and the EEC signed

a five-year Commercial and Economic Cooperation Agreement. Further visibility

was gained by the EEC in 1983 when the EC Delegation was established at

New Delhi.

The EU for a long time was India’s largest economic partner. In 1984, Indian

imports from the EC represented 23 per cent of its total imports, as compared to

10 per cent from the US, 7 per cent from Japan and 6 per cent from the former

Soviet Union. Indian exports also were marked by the same trend with 20 per cent

being accounted for by the EC, 24 per cent by the US, 10 per cent by Japan and

12 per cent by the former Soviet Union (European Commission 1986: 7). Although

the 1980s witnessed enhanced trade and commercial relations, it was the end of

the Cold War that provided the impetus to moving India–EC relations forward.

Relations with the EC were in tandem with India’s relations with some of the

key countries of Western Europe—United Kingdom, France and West Germany.

With the UK in particular, India has had a multi-faceted bilateral relationship that

evolved into a new political engagement after Indian independence in 1947.

France and West Germany, also called the ‘motors of European Integration’,

engaged India differently and the political outcome was consequently more dis-

tinctive. Indo-French relations were far more formal and lacked much political

warmth until the end of the Cold War (Gupta 2009). Despite being the third largest

weapons supplier to India in this period, the political equation was restrained by

the ambivalent French attitude towards Pakistan. West Germany, on the other

hand, has a more intense relationship with India.

Indo-German relations were even more influenced by the Cold War. While India

adopted non-alignment and West Germany got integrated into the NATO; their

ideological differences limited the relationship to the areas of trade, development

assistance and education. A noted West German scholar described the German

political engagement with India as a policy of ‘benign neglect’ (Rothermund

1995: 474). In other words, the political aspect of the relationship could not de-

velop beyond these issues until 1990, when German unification took place lead-

ing to the end of the Cold War.

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

India and the European Union 375

Changing Global Geopolitics and Its Impact on India

and Europe

With the end of the Cold War, patterns of order and familiarity of structures have

given way to uncertainty, challenges and opportunities for all states. The shifting

international political and economic landscape and globalization have contributed

to a restructuring of relations between states.

In the case of India, it is no longer contained in South Asia by the Cold War

rubric (Mohan 2003). The economic crisis of the early 1990s that led to India’s

economic liberalization has also paid political dividends. The Indian nuclear tests

in 1998 and a steadily performing economy have changed not only India’s percep-

tion of itself but the world’s perception of India (Bava 2007: 2). At a speech on

‘India’s Strategic Perspective’ at Harvard University, Boston, on 25 September

2006, Pranab Mukherjee, then Defence Minister, said, ‘India’s strategic perspec-

tives have been shaped by its long civilizational history, its geography, its culture

and geopolitical realities.’ There is no denying that, since the nuclear tests, there

has been a new assertiveness in Indian foreign policy. Thus, not only is there a

new power hierarchy emerging globally but it has also transformed India’s politi-

cal, economic and security requirements. The shift in economic policy can be seen

as a watershed moment in India’s development trajectory; it also set a new course

to its political growth as an emerging power (Bava 2010: 231).

European integration, on the other hand, is a process that involves more than

just economics. The process of political and economic integration is about organ-

izing Europe in ways that the great conflicts of the past do not recur in the future.

What has emerged over a period of time, and especially over the last twenty-five

years, is an internal transformation of the EC. A process of incrementalism driven

by a political will to cooperate has led to the major achievements—the Single

European Act of 1986, the Treaty for European Union 1992, the Treaties of

Amsterdam 1994 and Nice 2000 and the Lisbon Treaty 2008. In part, the transfor-

mation of the EC in the 1990s was also a response to the shift in geopolitics after

the end of the Cold War. The rapid unification of Germany also raised issues not

only on the new boundaries of Western Europe, but more significantly, on the

enhanced power of Germany and the need for the EC to adapt to the new political

reality.

The 1992 Treaty transformed the EC into more of an economic and political

entity called the European Union (EU). It not only strengthened its institutions but

also acquired a greater ‘actorness’ in the process. As the EU itself is an ongoing

process of development, its actorness is also constantly evolving. Democracy, rule

of law, market economy and multilateralism are the values that it espouses. The

EC’s transformation into the EU shows the dynamic internal process of respond-

ing to internal and external political developments. Because the EU is constantly

evolving, it is often argued that ‘the EU is a challenge to how we conceptualize

democracy, authority and legitimacy in contemporary politics’ (Laffan 1999: 330).

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

376 Ummu Salma Bava

These broad political and economic developments at the global level provided

both India and the EU with new opportunities for engagement. The first official

New Asia Strategy of the EU was adopted in 1994 and subsequently revised in

2001. As the document states, it was a first attempt to take an integrated and bal-

anced view of the relations between the EU and its Asian partners. The changing

economic balance of power was the major reason for the EU to focus its attention

on Asia as a region and accord it high priority, although it had bilateral relations

with many countries of Asia. The 1994 Asia Strategy was aimed primarily at

Southeast Asia and it resulted in the launch of the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM)

in 1996. The economic rise of East Asia brought it far greater political visibility

as well. ‘The increasing strategic value of East Asia provided a timely and wel-

come additional impetus to intensified EU approach towards East Asia’ (Park and

Heungchong 2008: 73).

As India had just launched its economic liberalization at this time, there was a

time lag before the EU extended recognition to India as a critical partner. What is

significant is that the EU’s focus on Southeast Asia coincided with India’s launch

of its own Look East policy in 1991. An economically vibrant and emerging

Southeast Asia attracted both the EU’s and India’s attention. In addition, there

were many factors driving both to engage the region, but what distinctly stood out

was the rapid economic growth of Southeast Asia, the rise of the Asian tigers and

growing influence of China, which was transforming the region. It was not until a

decade later, that India came to be regarded by the EU as having the potential to

be engaged as a different actor.

India and the EU: The Post-Cold War Relationship

In examining the India–EU strategic partnership, one needs to pay attention to

two important elements—the shift in global politics and the transformation of

both India and the EU that culminated in the new relationship. Undoubtedly, ‘the

cornerstone of the EU-India relationship lies in trade and investment’. This state-

ment by Pascal Lamy, the European Union Trade Commissioner, in 2003 under-

scored the nature of the relationship. The 1990s still registered high trade with the

EU, accounting for 24 to 26 per cent of India’s total trade (see Table 1).

The per capita income in India doubled during the period 1990–2005 as a result

of the economic growth. Consequently, India’s trade with other countries (other

than the EU) also grew significantly and this diversification impacted India–EU

trade even as their political engagement was being transformed in the new millen-

nium. During the same period, India’s trade with the US and China registered a

faster growth trend than with any other region.

However, with the push given by the upgradation of political relations in 2004,

India–EU trade doubled from €28.6 billion in 2003 to over €55 billion in 2007.

The EU investment in India has tripled since 2003, from €759 million to €2.4 bil-

lion in 2006 and trade in commercial services has also increased from €5.2 billion

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

India and the European Union 377

Table 1. Percentage Share of India’s Trade with EU-27 during 1996–2000

Year Percentage of Total Indian Trade

1996–97 26.48

1997–98 27.21

1998–99 26.57

1999–2000 24.04

2000–01 22.47

2001–02 21.84

2002–03 21.65

2003–04 20.84

2004–05 19.25

2005–06 19.51

2006–07 18.14

2007–08 17.59

Source: Sachdeva (2008: 348).

in 2002 to €12.2 billion in 2006 (European Commission 2011). In the recent years,

the global financial crisis led to decline in trade, which has recovered since

2010.

The step-by-step upgrading of the India–EU political and economic relation-

ship to the summit level in June 2000 in Lisbon could be viewed as a signal by the

EU of its intentions to enhance its political and economic relations with India. But

the enhancing of this summit-level relationship to a strategic partnership in 2004

was driven largely by other factors that influenced the EU to define its own strate-

gic concept. One can read the EU’s intentions about the region in its Asia strategy.

The EU had set for itself the task to ‘follow a forward-looking policy of engage-

ment with Asia, both in the region and globally’ (European Commission 2001).

The strategy identified six objectives: contributing to peace and security, promot-

ing mutual trade and investment flows, protecting human rights, building global

partnerships and enhancing the awareness of Europe in Asia and vice versa.

In 2001, the EC set out a strategy for cooperation with Asia entitled ‘Europe

and Asia: A Strategic Framework for Enhanced Partnership’. A first review of the

Commission’s strategic framework for action in Asia took place in May 2007.

Subsequently, the Commission set up a Regional Programming for Asia Strategy

Document 2007–2013 and identified three priority areas: support for regional

integration, policy and know-how based cooperation in environment, energy and

climate change and support for uprooted people.

Although the 2001 document laid the blueprint for a more enhanced engage-

ment with Asia, other factors contributed to this policy shift within the EU. A

major trigger for the shift in the EU’s engagement with different countries was the

September 2001 attacks on the US. There is no denying that 9/11 proved to be

another dividing line in international politics and in particular for the transatlantic

relationship. Although the US-initiated war on terror (named Operation Enduring

Freedom) in Afghanistan found support in Europe, its subsequent invasion of

Iraq in 2003 left the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) totally in

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

378 Ummu Salma Bava

disarray. The EU could not speak in one voice and lacked a cohesive approach to

the problem. The special relationship of the United Kingdom with the US was

soon evident with the UK ardently supporting the pre-emptive war America

planned against Iraq. However, Germany and France were strongly opposed to it

and did not support such an action. Interestingly, some of the countries of Central

and Eastern Europe, which had recently joined NATO, such as Poland, partici-

pated in the war. This drew the comment from the then US Secretary of Defence,

Donald Rumsfeld that France and Germany was ‘old Europe’. This eagerness of

Poland to engage was more starkly offset by the French and German refusal to

support such an action that resulted in the NATO ambassadors turning down the

American request for advance military planning. The EU’s response at best could

be described as incoherent—while France and Germany sought legitimacy within

a UN mandate, Italy and Spain favoured a US strike, and Britain stood resolutely

in support of the US. The much-proclaimed CFSP launched a decade earlier in

1992 remained shattered.

It was this that led to soul-searching within the EU on its CFSP and the EU’s

High Representative for Common Foreign and Security Policy, Javier Solana,

presented a strategy paper in June 2003 that served as the basis for a new European

Security Strategy (ESS) to be adopted by the European Council in December that

year. Titled ‘A Secure Europe in a Better World’, the ESS was indeed a remark-

able document put out by the EU as roadmap for collective action that identified

five security threats: terrorism, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, re-

gional conflicts, state failure and organized crime. It also emphasized that the EU

would have to think globally but act locally. Although emphasizing the building

of security in its neighbourhood, the EU, for the first time, also enunciated the

need for an international order that was based on ‘effective multilateralism’.

In order to realize these security objectives, the EU proposed an approach that

envisaged developing key partnerships, working, in particular, with the US that

continues to anchor transatlantic relations with Russia, Japan, China, Canada and

India (Council of the European Union 2003). It is this that propelled the EU to

engage India in a strategic partnership since 2004.

Building a Strategic Partnership

In retrospect, one can say that the launch of the India–EU Strategic Partnership in

2004 was the recognition by the EU of India as a regional power that was gradu-

ally exerting a growing influence on many international issues. Internationally,

recognizing India’s importance has led to a new rationale for engagement and

building up the partnership with it. Emerging or rising India’s potential has

endorsed it as a likely partner in providing stability and order not merely in South

Asia but to Asia as a whole. Four years after the launch of the annual summits

between India and the EU, at The Hague Summit in 2004, it was decided to

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

India and the European Union 379

upgrade the India–EU relationship to a strategic partnership. In the following

year, at New Delhi, both sides adopted a detailed Joint Action Plan (JAP). The

Joint Action Plan committed itself to the following issues (Council of the European

Union 2005):

z Strengthening dialogue and consultation mechanisms;

z Deepening political dialogue and cooperation;

z Bringing together people and cultures;

z Enhancing economic policy dialogue and cooperation;

z Developing trade and investment.

In 2006, at the Helsinki Summit, both sides endorsed a proposal to negotiate a free

trade agreement (FTA), negotiations for which are still under way. India’s grow-

ing economic performance has enabled it to take a tough stand on trade-related

matters.

The JAP was reviewed at the 2008 summit held in Marseille, France, which

focused on promoting four areas: peace and comprehensive security, sustainable

development, research and technology, and people-to-people and cultural ex-

changes. The JAP is an ambitious agenda and emphasizes a strong political, eco-

nomic and civil society engagement. It ‘offers a roadmap for future bilateral

relations’ (Wagner 2008: 103).

In terms of the objectives laid out in the JAP, political cooperation with respect

to security and defence between India and the EU has grown extensively in the

aftermath of the Mumbai attacks in 2008. There has been a steady increase in the

dialogue on terrorism at all levels. The 2005 India–EU Joint Action Plan had

identified counter-terrorism as an area of cooperation. This was reiterated in the

2009 EU–India Summit Declaration. However, there is a need to revitalize and

restructure the cooperation which has so far been bilateral rather than multilateral.

This point was also reiterated by the EU–India Forum on Effective Multilateralism

in October 2009 in New Delhi. It said in its recommendations that ‘there is a need

to establish an India-EU Joint Working Group on counter terrorism to develop a

common understanding of issues related to terrorism and response mechanisms’

(ICWA 2009).

On the economic front, since 2007, India and the EU have been negotiating a

FTA, which covers trade in goods and services, investments, intellectual property

rights and government procurement. Supporters on both sides speak of the over-

whelming positive impact it will have on trade between India and the EU.

The delay in concluding the FTA points to problems in some key areas. One

area is the liberalization of trade and investment in banking services. The EU is

seeking a larger market access for its banks; in particular, this is being pursued

aggressively by the UK and Germany. Undoubtedly, the profitability of the Indian

economy attracts foreign banks to India. Most foreign banks in India are reporting

high profits. As on March 2010, there were nine EU-based banks operating in

India and they are keen to concentrate on niche marketing in the metros rather

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

380 Ummu Salma Bava

than on social and developmental banking in rural areas. India will need to tread

with caution in the light of the last financial crisis that also enveloped European

banks. In the absence of adequate regulations, the EU’s desire for an unrestricted

investment environment in India could cause major repercussions for the econ-

omy (Singh 2011).

Another key area of discord between India and the EU pertains to intellectual

property rights in the field of medicine. The EU would like to include data exclu-

sivity, which would impact the production of generic drugs in India. In fact, the

EU is supported by leading pharmaceutical companies in Europe, which would

like this provision to be incorporated in the FTA. Such generic drugs are exported

to Africa and other poor regions to combat endemic diseases such as HIV/AIDS,

tuberculosis and malaria. Given that generic drugs are cheaper than patented

drugs, these have played an important role in fight against these diseases. Interest-

ingly, there is protest within the EU civil society itself against this issue. The

CEO, a watchdog group on the European industries’ influence on the EU’s invest-

ment and trade relations with the developing world, accused the EC ‘of discrimi-

nating in favour of corporate lobby groups and of violating the EU’s transparency

rules’ (Godoy 2011).

Emphasis on common interests and common values notwithstanding, the need

to identify deliverable cooperation has become more important. In comparison

with the EU, India’s relations with the US witnessed a major political shift: the US

has recognized the valid claims of India’s national interest and has acted to en-

hance and strengthen India’s military, economic and technological capabilities,

while endorsing ‘common values’ (Bava 2008: 108). India–US relations have

been a game changer—bringing deliverables to the table that no other country has

been able to. It has had the impact of single-handedly transforming not only bilat-

eral ties but has had significant multilateral consequences as well. The civil

nuclear agreement between the two countries has enabled global civil nuclear

commerce and trade.

Although some of India’s interests converge with those of the EU, the differ-

ence in global aspirations would be a hindrance to a strategic convergence between

the two sides. While India is the only non-Western democracy in South Asia and

ideationally the closest to the Western democratic normative structure, its demo-

cratic practice did not get the recognition of the West for a long time.

While India and the EU have shared values based on democracy and human

rights, there had been a tendency in the past for the EU to lecture India on its

human rights practice. In stark contrast, the EU has actively engaged China

although it is not a democracy. This reiterates the fact that despite the emphasis on

normative values, the EU is driven by realistic considerations of trade (Bava 2008:

109). Although the EU is an undisputed global economic actor, it does not yet

have commensurate political or military strength. Its inability to articulate a com-

mon foreign policy position, once again evidenced by the deep divisions over the

engagement in the wake of the unrest in Libya and the strong bilateral positions

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

India and the European Union 381

articulated by individual member states, has also diminished its credibility as a

critical security player.

The undercutting of India–EU relations is partially due to the remarkable de-

velopment in India’s bilateral relationships with many European countries. The

distinct feature of the strategic partnership has been the growing significance of

India not only as an economic but also a political partner for the EU. EU’s self-

representation at the global level is replete with references to a foreign policy

guided by values and principles. Ascribing higher normative values to EU action

abroad and purely national interest to India assumes that the EU has no national/

collective interest, which is clearly not the case if one were to read the 2003 ESS

that highlights the challenges confronted by the EU and the proposed action. The

ambiguity with which the EU appears to treat the two Asian emerging powers,

China and India, only emphasizes the need for a serious strategic dialogue with

India that goes beyond the enumeration of normative principles to concrete action

that acknowledges India’s real and nascent potential as a major global actor.

Europe, as the ‘norm entrepreneur’, is a satiated power, whereas India is trying to

become a norm setter, seeking to change the status quo in matters of global gov-

ernance (Bava 2008: 112). The fact that the US and the EU engage a rising Asia

in different ways, underscores who shapes what aspect of global politics (Bava

2008: 113).

The emphasis on multilateralism has facilitated a shift in foreign policy discus-

sions from substantive policy framework to a focus on ‘co-ordination’, ‘coher-

ence’, ‘comprehensiveness’ and ‘joined-up policymaking’ (Chandler 2007). This

interplay of factors has meant that the capacity of the different actors in the global

framework has also been transformed. Both India and the EU have emerged as

significant actors since the end of the Cold War. While the EU has evolved beyond

being an economic super power, India is being engaged not only for what it stands

for but for the inherent potential that it holds for future alignments. Undoubtedly,

there has been an upgradation of the relationship but there is an information and

perception deficit on both sides.

India’s Bilateral Strategic Partnerships

The effort to build a strategic partnership with the EU has not meant an end to

bilateralism in India’s engagement with Europe. New Delhi has engaged major

players—London, Paris and Berlin—as it found them receptive. The rotating

presidency of the EU, which was in force till 2009, meant that smaller countries

also could lead the EU, but this had a rather negative impact on India–EU rela-

tions as they were seen as keen to lecture India on issues of human rights and

nuclear proliferation.

What cannot be overlooked is that India has over twenty strategic partner-

ships. What is the basis for this upturn in relations? Economics dominates all

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

382 Ummu Salma Bava

these relationships. But what is significant is the transformation of this economic

relationship—from a situation in which India was perceived as an aid recipient

developing country to a development marked by European firms’ interest in

investing in India (given its new growth profile) and Indian firms acquiring assets

in the West. As a new growth hub, there has been a repositioning of the Indian

image in the West. This move by the EU to upgrade its relations with India was

also reflected in the bilateral relations that India had with the UK, France and

Germany.

The UK upgraded its relations with India to the level of a strategic partnership

in 2004. Building on the existing institutional structure, it sought to engage India

further. In February 2010, India and the UK signed a civil nuclear cooperation

agreement. Although the large Indian diaspora is important to local politics in the

UK, it does not have the kind of transformative power and influence as is the case

in the US, where the diaspora has remained at the forefront of changing the per-

ception of India. The visit of Prime Minister, David Cameron to India in July 2010

saw the relationship elevated to ‘Enhanced Partnership for the Future’ with a

focus on enhancing trade and investments.

The bilateral relationship with France underwent a transformation after India

conducted its nuclear tests in 1998. It was one of the few nations that did not criti-

cize India’s nuclear tests; nor did it impose any economic sanctions. Although

France has supported India’s bid for a permanent seat in the UNSC, according to

some Europe watchers, there has been lack of boldness in Indo-French relations.

India and France signed a ‘Framework Agreement for Civil Nuclear Cooperation’

in January 2008 during French President Nicolas Sarkozy’s visit to India, and the

visit of Prime Minister Manmohan Singh in September 2008 led to the establish-

ment of Indo-French trade in nuclear technology.

Germany is India’s most important trade partner within the EU and the empha-

sis is on skills, goods and technology. It ranks eighth in terms of foreign direct

investment and over 1,000 companies with differing market shares are present in

India in different capacities. It is no surprise that German companies have a high

brand visibility and are valued for their quality products. Total Indian investment

in Germany after unification has amounted to €4.125 billion. Liberalization and a

decade of growth have led to new trends in the economic sector, with Indian

investments heading to Europe. There are numerous success stories of Indian

firms successfully competing and acquiring European companies, ranging from

the Mittals’ acquisition of Arcelor to the Tata group buying Land Rover.

The foreign ministers of India and Germany in May 2000 adopted the ‘Agenda

for German-Indian Partnership in the 21st Century’. This ten-point agreement

effectively launched a ‘strategic partnership’ and has become the basis for renewed

and enhanced relations between India and Germany. Going beyond economics

and trade, it enhanced political relations by institutionalizing meetings at the for-

eign ministers’ level and reiterated the intention of both countries to work on

security issues and disarmament. Even more significant is the fact that they agreed

to address the issue of reform of the United Nations.

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

India and the European Union 383

Defence cooperation has emerged as a means of upgrading and boosting mili-

tary and strategic ties between the countries. India’s military modernization,

which involves the purchase of weapons, aircraft and other systems, is one of the

largest military purchases globally, and it plans to spend an estimated $80 billion

on military modernization programmes by 2015. What is also significant in this

new political–security engagement is that these relationships are moving beyond

the buyer–seller model to one that emphasizes trust and long-term investment as

the new agreements focus on technology transfer leading to joint development

and co-production in India.

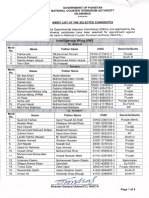

Figure 1 shows the dominant role of the former USSR and Russia as arms sup-

pliers to India not only during the Cold War period but later too. It has enabled

Russia to still exercise a reasonable level of leverage even though its own global

influence has waned. A major push factor in expanding the defence suppliers

group has been the difficulties in getting Russian supplies and spares. If the Cold

War provided a restricted arms market to India, today there has been an expansion

of defence procurement from other suppliers—noticeably Israel and the US. As

India modernizes its defence forces, the large price tag associated with it has

brought in many countries vying to get a part of the deal. The recent visit of the

German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, in May 2011 focused on whether the EADS

(a European consortium including Germany, France, the UK and Spain) would

bag the enviable contract for the US$10 billion Medium Range-Multi Role

Combat Aircraft (M-MRCA).

The issue of who are India’s partners in the current global configuration tells

a story of changing power equations. Increasing political complexities at the

Figure 1. Major Suppliers of Arms to India, 1985–2008

Source: Gallenkamp (2009: 7). This figure is based on the Trend Indicator Values (TIV), provided by

the SIPRI database on arms transfers. Available at http://www.sipri.org/contents/armstrad/

at_db.html

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

384 Ummu Salma Bava

global level require more interaction and engagement. There is growing interest

in Britain, France and Germany to enhance their relations with India and benefit

from its economic growth. Transforming the relationship indicates the recognition

of India as a significant actor in global politics. Making India a strategic partner is

something one finds in common across the three countries.

There is, however, a perception among European analysts that India’s close-

ness to the US has impacted the development of such partnerships with the UK,

France, Germany and the EU. In part, this feeling is strengthened by the fact that

none of these countries can individually or together facilitate a shift in the rules of

the global order the way America can—the civil nuclear deal is a notable example

in this context.

Conclusion

Given the difference in the capability of states at the normative and material level,

there is inherent asymmetry in strategic partnerships, which often signify that

relationships are about power and interdependence (Grevi 2008: 145). The decla-

ration of strategic partnership does not indicate the absence of differences between

the concerned parties. This point is demonstrated amply in the case of India and

the EU as well. Recognition of India’s potential as a leading global actor by the

West has been late. ‘As India’s concerns about certain global challenges get shared

with other countries, it also draws India into a larger orbit of collective action’

(Bava 2010: 120).

The EU suffers at two levels. First, ‘it suffers from a deficit of recognition as a

political actor enjoying the full array of traditional attributes of power’ (de

Vasconcelos 2008: 17). Second, the lack of political consensus within the EU on

foreign policy issues prevents New Delhi from considering Brussels as an import-

ant political actor. Despite a considerable ideational convergence between India

and the EU, it does not automatically translate into cooperation. Things in the past

happened more by chance and less by intent. Undoubtedly, there has been a shift

in the focus of relations, by changing the political equation and taking it beyond

rhetoric. India’s foreign policy today is a pragmatic blend of security and eco-

nomic imperatives. ‘As the relative capabilities of India have grown, the assess-

ment of other countries about India has also slowly shifted’ (Bava 2010: 125).

In the global context, as Joseph Nye has indicated, there are two visible simul-

taneous trends viz. power in transition and the diffusion of power (Nye 2011). In

this context, strategic partnerships stand between interdependence and power pol-

itics (Grevi 2008: 145). The significant question is whether ideational proximity

can be converted into interest convergence. In effect, the challenge for the India–

EU strategic partnership is to balance norms and realism (Bava 2008: 113). As the

EU tries to shape a universal concept of multilateralism and effectively tries to

multi-lateralize the multi-polarity, it seeks to develop partnerships with leading

and emerging global actors so that it can play a defining role alongside.

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

India and the European Union 385

Note

1. The European Economic Community is also called or referred to as the European Com-

munity (EC) and since the adoption of the Treaty of Maastricht in 1992, it is called the

European Union (EU). These different nomenclatures appear in the article in pertinence

to the specific period or year under reference.

References

BAVA, UMMU SALMA. 2006. ‘India—An Emerging Power in International Security?’ in

A.C. Vaz, ed., Intermediate States, Regional Leadership and Security: India, Brazil

and South Africa (pp. 71–86). Brasilia: University of Brasilia.

———. 2007. ‘India’s Role in the Emerging World Order’, Dialogue on Globalization,

FES Briefing Paper, New Delhi: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, pp. 1–7.

———. 2008. ‘The EU and India: Challenges to a Strategic Partnership’, in Giovanni

Grevi and Alvaro de Vasconcelos, eds, Partnerships for Effective Multilateralism.

Paris: Institute for Security Studies, No. 109, pp. 105–13.

———. 2010. ‘India: Foreign Policy Strategy between Interests and Ideas’, in Daniel

Flemes, ed., Regional Leadership in the Global System: Ideas, Interests and Strategies

of Regional Powers (pp. 11–126). Surrey, England: Ashgate.

BRETHERTON, CHARLOTTE and JOHN VOGLER. 1999. The European Union as Global Actor.

London: Routledge.

CHANDLER, DAVID. 2007. ‘The Death of Foreign Policy’, Spiked, 13 June, http://www.

spiked-online.com/index.php?/site/article/3474/ (accessed on 30 November 2011).

COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION. 2003. ‘European Security Strategy: A Secure Europe in

a Better World’, Brussels, http://www.consilium.europa.eu/uedocs/cmsUpload/78367.

pdf (accessed on 30 November 2011).

———. 2005. The India-EU Strategic Partnership, Joint Action Plan, 11984/05, Brussels.

DE VASCONCELOS, ALVARES. 2008. ‘Multilateralising Multipolarity’, in Giovanni Grevi and

Alvaro de Vasconcelos, eds, Partnerships for Effective Multilateralism. Paris: Institute

for Security Studies, No. 109, pp. 11–32.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION. 1986. ‘The European Community and India’, in Europe Information

External Relations, Brussels, 85/86, pp. 1–15.

———. 1994. ‘Towards a New Asia Strategy’, Communication from the Commission to the

Council-COM(94)314 final, Brussels.

———. 2001. ‘Europe and Asia: A Strategic Framework for Enhanced Partnerships’, Com-

munication from the Commission to the Council COM(2001) 469 final, Brussels. http://

www.developmentportal.eu/snv1/dmdocuments/strategy_asia_2001_en.pdf (accessed

on 30 November 2011).

———. 2011. ‘EU Bilateral Relations—Trade with India’, http://ec.europa.eu/trade/

creating-opportunities/bilateral-relations/countries/india/index_en.htm (accessed on

30 November 2011).

EUROPEAN COMMISSION, DG TRADE. 2011. ‘India—Main Economic Indicators and EU

Bilateral Trade and Trade with the World’, Brussels, pp. 1–11. http://trade.ec.europa.

eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113390.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2011).

GALLENKAMP, MARIAN. 2009. Indo-German Relations: Achievements and Challenges in the

21st Century. IPCS Special Report, No. 79, New Delhi: IPCS.

GODOY, JULIO. 2011. ‘EU Trade Deal with India Stalemated by Threat to Affordable

Drugs’, Global Issues, http://www.globalissues.org/news/2011/05/18/9695 (accessed

on 30 November 2011).

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

386 Ummu Salma Bava

GREVI, GIOVANNI. 2008. ‘The Rise of Strategic Partnerships: Between Interdependence and

Power Politics’, in Giovanni Grevi and Alvaro de Vasconcelos, eds, Partnerships for

Effective Multilateralism: EU Relations with Brazil, China, India and Russia. Paris:

Institute for Security Studies, No. 109, pp. 145–72.

GUPTA, SANJAY. 2009. ‘The Changing Patterns of Indo-French Relations: From Cold War

Estrangement to Strategic Partnership in the Twenty-first Century’, French Politics,

vol. 7, nos 3–4, pp. 243–62.

ICWA. 2009. ‘Report on India—EU Forum on Effective Multilateralism (8–9 October

2009) Indian Council of World Affairs, Sapru House, New Delhi’, http://www.icwa.

in/icwa_hindi/eu.html (accessed on 30 November 2011).

LAFFAN, B. 1999. ‘Democracy and the European Union’, in Laura Cram, Desmond Dinan

and Neill Nugent, eds, Developments in the European Union (pp. 330–52). London:

Macmillan.

MOHAN, C. RAJA. 2003. Crossing the Rubicon: The Shaping of India’s New Foreign Policy.

New Delhi: Viking.

NYE, JOSEPH. 2011. The Future of Power. New York: Public Affairs.

PARK, SUNG-HOON and HEUNGCHONG KIM. 2008. ‘Asia Strategy of the European Union and

Asia-EU Economic Relations: Basic Concepts and New Developments’, in Richard

Balme and Brian Bridges, eds, Europe-Asia Relations: Building Multilateralisms

(pp. 66–82). Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave.

PIENING, C. 1997. Global Europe: The European Union in World Affairs. London: Lynne

Rienner.

ROTHERMUND, DIETMAR. 1995. Indien. Kultur, Geschichte, Politik, Wirtschaft, Umwelt, Ein

Handbuch. Munich: C.H. Beck.

SACHDEVA, GULSHAN. 2008. ‘India and the European Union: Broadening Strategic Partner-

ship beyond Economic Linkages’, International Studies, vol. 45, no. 4, pp. 341–67.

SINGH, KAVALJIT. 2011. ‘India-EU Free Trade Agreement: Rethinking Banking Services

Liberalization’, Countercurrents.org, http://www.countercurrents.org/ksingh240311.

htm (accessed on 30 November 2011).

Wagner, Christian. 2008. ‘The EU and India: A Deepening Partnership’, in Giovanni

Grevi and Alvaro de Vasconcelos, eds, Partnerships for Effective Multilateralism: EU

Relations with Brazil, China, India and Russia. Paris: Institute for Security Studies,

No. 109, pp. 87–103.

International Studies, 47, 2–4 (2010): 373–386

Downloaded from isq.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NORTH DAKOTA on May 31, 2015

You might also like

- Criminal Law 1 Reviewer Bar 2021Document58 pagesCriminal Law 1 Reviewer Bar 2021Henrik Tagab Ageas100% (5)

- Our ChallengeDocument198 pagesOur ChallengeZachary KleimanNo ratings yet

- Evolution of India and The European Union Trade Relations: A Realistic Approach Towards Cooperation PDFDocument11 pagesEvolution of India and The European Union Trade Relations: A Realistic Approach Towards Cooperation PDFPradeep KumarNo ratings yet

- BIR Form 17.60Document3 pagesBIR Form 17.60ArtlynNo ratings yet

- Guevarra V BanachDocument2 pagesGuevarra V BanachRishell Miral100% (2)

- The Eu and India Common Interests Divergent PoliciesDocument14 pagesThe Eu and India Common Interests Divergent PoliciesnaveengargnsNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal: by Nishikant NaveenDocument8 pagesResearch Proposal: by Nishikant NaveennishikantnaveenNo ratings yet

- India's Role in a Multipolar WorldDocument7 pagesIndia's Role in a Multipolar WorldASHNo ratings yet

- RoadmapDocument17 pagesRoadmap王思远No ratings yet

- DP 250 Arun S Nair - 1Document102 pagesDP 250 Arun S Nair - 1Kanchan YadavNo ratings yet

- Espo PB9Document7 pagesEspo PB9Sourav BebartaNo ratings yet

- China Strategic Partnership DiplomacyDocument20 pagesChina Strategic Partnership DiplomacyIgnacio PuntinNo ratings yet

- Download India And The European Union In A Turbulent World 1St Ed Edition Rajendra K Jain full chapterDocument67 pagesDownload India And The European Union In A Turbulent World 1St Ed Edition Rajendra K Jain full chaptervirginia.webster851100% (4)

- EU Strategic Partnerships: MappingDocument56 pagesEU Strategic Partnerships: MappingMaggie PeltierNo ratings yet

- Belt and Road Initiative: Responses From Japan and India - Bilateralism, Multilateralism and CollaborationsDocument7 pagesBelt and Road Initiative: Responses From Japan and India - Bilateralism, Multilateralism and CollaborationsNecati EtliogluNo ratings yet

- Faculty of Law, University of Allahabad Prayagraj, Uttar PradeshDocument9 pagesFaculty of Law, University of Allahabad Prayagraj, Uttar PradeshPrerak RajNo ratings yet

- Topic The European Union-India Strategic Partnership: From The Hague To Brussels (2004-16)Document37 pagesTopic The European Union-India Strategic Partnership: From The Hague To Brussels (2004-16)Mukesh Shankar BhartiNo ratings yet

- Lewis2020 Chapter2Document17 pagesLewis2020 Chapter2MICHAEL CUMARNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy of India Towards China: Principles and PerspectivesDocument9 pagesForeign Policy of India Towards China: Principles and PerspectivesFaisal MezeNo ratings yet

- FULLTEXT01Document13 pagesFULLTEXT01Anish AgnihotriNo ratings yet

- The Analysis of The Relationship Between TheDocument11 pagesThe Analysis of The Relationship Between TheSurti SufyanNo ratings yet

- China's Policy Paper On The EU - Deepen The China-EU Comprehensive Strategic Partnership For Mutual Benefit and Win-Win CooperationDocument6 pagesChina's Policy Paper On The EU - Deepen The China-EU Comprehensive Strategic Partnership For Mutual Benefit and Win-Win CooperationMr LennNo ratings yet

- Note N°08/21: Japan and The EU: Shared Interests and CooperationDocument5 pagesNote N°08/21: Japan and The EU: Shared Interests and CooperationGuillaume AlexisNo ratings yet

- China and India and BrazilDocument11 pagesChina and India and Brazilcsc_abcNo ratings yet

- Indian Foreign Policy and The Multilateral WorldDocument9 pagesIndian Foreign Policy and The Multilateral WorldVlhruaia NunzemawiaNo ratings yet

- s41311-021-00288-2Document23 pagess41311-021-00288-2ganesh.uniofreadingNo ratings yet

- India-Myanmar Relations Journal ArticleDocument26 pagesIndia-Myanmar Relations Journal ArticleSanLynnAungNo ratings yet

- Unit India and European Union: StructureDocument13 pagesUnit India and European Union: StructureAbhijeet JhaNo ratings yet

- International Development and the Environment: Social Consensus and Cooperative Measures for SustainabilityFrom EverandInternational Development and the Environment: Social Consensus and Cooperative Measures for SustainabilityShiro HoriNo ratings yet

- The European Union and China - The Logics of Strategic PartnershipDocument17 pagesThe European Union and China - The Logics of Strategic PartnershipAlexandra IoanaNo ratings yet

- India s Foreign Policy Shift Adjustment and ContinuityDocument5 pagesIndia s Foreign Policy Shift Adjustment and Continuitysehajpreet kaurNo ratings yet

- A Study On India'S Bilateral Trade With JapanDocument13 pagesA Study On India'S Bilateral Trade With JapanRiti SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus International Political Economy 2021-2022Document10 pagesCourse Syllabus International Political Economy 2021-2022PalomaNo ratings yet

- 10 Shivani Chauhan VSRDIJBMR 13773 Review Paper 8 5 May 2018Document4 pages10 Shivani Chauhan VSRDIJBMR 13773 Review Paper 8 5 May 2018Dr. Sunil AgrawalNo ratings yet

- GRA - GLOBAL RESEARCH ANALYSIS X 40Document2 pagesGRA - GLOBAL RESEARCH ANALYSIS X 40RajDoshiNo ratings yet

- MEA Annual Report 2011-2012 Highlights India's Foreign RelationsDocument240 pagesMEA Annual Report 2011-2012 Highlights India's Foreign RelationsgorumadaanNo ratings yet

- The Future of EU-India Strategic RelationsDocument6 pagesThe Future of EU-India Strategic RelationsMohammad Saeed HusainNo ratings yet

- Ind EuDocument16 pagesInd EuAbdul jaleel KpNo ratings yet

- Historical Aspects of Modern Indian Foreign PolicyDocument3 pagesHistorical Aspects of Modern Indian Foreign PolicyEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- EU Environmental Policy Evolution and Mixed OutcomesDocument28 pagesEU Environmental Policy Evolution and Mixed Outcomesdiplomski DiplomskoNo ratings yet

- India: European External Action ServiceDocument23 pagesIndia: European External Action ServiceAndra GutoiuNo ratings yet

- Strengthening India-China RelationsDocument15 pagesStrengthening India-China RelationsRitam TalukdarNo ratings yet

- Indian Foreign Policy From 1972-1991Document28 pagesIndian Foreign Policy From 1972-1991Inzmamul HaqueNo ratings yet

- Political ScienceDocument5 pagesPolitical ScienceOtieno OmondiNo ratings yet

- European Union India (B)Document46 pagesEuropean Union India (B)Divyesh AhirNo ratings yet

- India's Foreign Policy: A Overview: AbstractDocument5 pagesIndia's Foreign Policy: A Overview: AbstractnopenopeNo ratings yet

- Culturally Sustainable Development Theoretical Concept or Practical PolicyDocument16 pagesCulturally Sustainable Development Theoretical Concept or Practical PolicyZuzu FinusNo ratings yet

- The Legal-Institutional Framework of EU Foreign Policy: Set-Up and ToolsDocument27 pagesThe Legal-Institutional Framework of EU Foreign Policy: Set-Up and ToolsRavi PrakashNo ratings yet

- Ran Vijay Sing - Political ScienceDocument3 pagesRan Vijay Sing - Political Sciencev.raj.iimNo ratings yet

- USStrategic Relationshipinthe 21 ST CenturyDocument30 pagesUSStrategic Relationshipinthe 21 ST Centuryemanuelmusic51No ratings yet

- Europe Must Strengthen Partnership with Emerging IndiaDocument2 pagesEurope Must Strengthen Partnership with Emerging IndiaderafNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy of Modi EraDocument15 pagesForeign Policy of Modi Erakakulsharma2005No ratings yet

- Referat Engleza 1Document7 pagesReferat Engleza 1Roxana SamsonNo ratings yet

- Keeping EU-Asia Reengagement On TrackDocument34 pagesKeeping EU-Asia Reengagement On TrackCarnegie Endowment for International PeaceNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Notes-Alternative Centres of PowerDocument8 pagesChapter 4 Notes-Alternative Centres of Powernavika VermaNo ratings yet

- SDG Interlinkages Jrc115163 Final On LineDocument48 pagesSDG Interlinkages Jrc115163 Final On LinePedro AugustoNo ratings yet

- Cost and Benefits of Integration in The European Union and in The Economic Monetary Union (Emu)Document48 pagesCost and Benefits of Integration in The European Union and in The Economic Monetary Union (Emu)Adela DeZavaletaGNo ratings yet

- China-India Relations: A S I e - V I S I o N S 3 4Document37 pagesChina-India Relations: A S I e - V I S I o N S 3 4Vân AnhNo ratings yet

- Japan–India Relations: Peaks and Troughs Over Six DecadesDocument11 pagesJapan–India Relations: Peaks and Troughs Over Six DecadesTanmay BhattNo ratings yet

- Indonesia-China Economic Relations An Indonesian PDocument27 pagesIndonesia-China Economic Relations An Indonesian PPuspa Arditha ArdithaNo ratings yet

- Gaspp 92002Document107 pagesGaspp 92002Ibrahim ZahreddineNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy, Defense, and Beyond Decoding The Multifaceted Indo-Russian NexusDocument23 pagesDiplomacy, Defense, and Beyond Decoding The Multifaceted Indo-Russian NexusPratyashaNo ratings yet

- How Venice Took Over England - (And Other Articles) EIRPalmerstonsZooDocument44 pagesHow Venice Took Over England - (And Other Articles) EIRPalmerstonsZooZoran Yaban-HitoNo ratings yet

- Merit List of Selected CandidateDocument5 pagesMerit List of Selected CandidateAli Sher0% (1)

- A Higher Level of Education in Police Work Is Essential To Improving Professional Development and Opportunities For AdvancementDocument17 pagesA Higher Level of Education in Police Work Is Essential To Improving Professional Development and Opportunities For AdvancementInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Final Exam Purposive CommunicationDocument2 pagesFinal Exam Purposive CommunicationReñer Aquino Bystander0% (1)

- A Report On 10 Netiquette Guidelines Every Online StudentsDocument1 pageA Report On 10 Netiquette Guidelines Every Online StudentsJade BehecNo ratings yet

- Commercial Banking Session 1 IntroductionDocument14 pagesCommercial Banking Session 1 IntroductionDeepika GulatiNo ratings yet

- Open Book - The Inside Track To - John C. P. Goldberg - 1Document11 pagesOpen Book - The Inside Track To - John C. P. Goldberg - 1smith smith100% (1)

- Brainy Kl6 Unit Test 1 A PDFDocument1 pageBrainy Kl6 Unit Test 1 A PDFwiktoriaNo ratings yet

- Xi-Biden Summit: US Statement in FullDocument3 pagesXi-Biden Summit: US Statement in FullscmpNo ratings yet

- City of Cagayan de Oro Oro Youth Center, 5 Floor JV Serina Building, City Hall Tel Nos (088) - 857-4281 Local 501Document2 pagesCity of Cagayan de Oro Oro Youth Center, 5 Floor JV Serina Building, City Hall Tel Nos (088) - 857-4281 Local 501Ernesto Baconga NeriNo ratings yet

- UNESCO. General Conference 14th Records of The General Conference, 14th Session, Paris, 1966, V. 1 - Resolutions 1967Document389 pagesUNESCO. General Conference 14th Records of The General Conference, 14th Session, Paris, 1966, V. 1 - Resolutions 1967Joplin28No ratings yet

- Bpo ReviewerDocument4 pagesBpo ReviewerJhaz EusebioNo ratings yet

- CISI Capital Markets Programme: DerivativesDocument9 pagesCISI Capital Markets Programme: DerivativesShilpi JainNo ratings yet

- Special 510 (K) Summary: Medtronic VascularDocument6 pagesSpecial 510 (K) Summary: Medtronic VascularManoj NarukaNo ratings yet

- Indo-Russian Relations in Recent Times: - Manali JainDocument6 pagesIndo-Russian Relations in Recent Times: - Manali JainGautya JajoNo ratings yet

- Michigan Teaching CertificateDocument1 pageMichigan Teaching Certificateapi-551502561No ratings yet

- gpujpthjp rk;kd; - Notice of Hearing in a Summary SuitDocument25 pagesgpujpthjp rk;kd; - Notice of Hearing in a Summary Suitsharanmit6630No ratings yet

- Dr. Bhimrao Ambedkar University, AgraDocument2 pagesDr. Bhimrao Ambedkar University, Agraajay sharmaNo ratings yet

- Homework 5Document2 pagesHomework 5Evelyn RiesNo ratings yet

- Final Fresno County GP LetterDocument10 pagesFinal Fresno County GP LetterMelissa MontalvoNo ratings yet

- 29 C Form Reminder LetterDocument6 pages29 C Form Reminder Letterspeed225No ratings yet

- DepEd Citizens Charter 2021 As of December 1 2021Document639 pagesDepEd Citizens Charter 2021 As of December 1 2021Annaliza Garcia EsperanzaNo ratings yet

- Amy Hall Civil Complaint Against The Brookline Police DepartmentDocument13 pagesAmy Hall Civil Complaint Against The Brookline Police DepartmentAbby PatkinNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 12th Edition, George Belch Michael BelchDocument28 pagesTest Bank For Advertising and Promotion: An Integrated Marketing Communications Perspective, 12th Edition, George Belch Michael BelchPauline Chavez100% (12)

- Mid Term Exam : Re-TakeDocument3 pagesMid Term Exam : Re-Takeabdul basitNo ratings yet

- Professional Conduct and Ethical Module 3Document10 pagesProfessional Conduct and Ethical Module 3moradasj0502No ratings yet