Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Porter 2013

Uploaded by

Stella ÁgostonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Porter 2013

Uploaded by

Stella ÁgostonCopyright:

Available Formats

Article

Research on Social Work Practice

2014, Vol 24(1) 50-56

The New Alternative DSM-5 Model ª The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permission:

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

for Personality Disorders: Issues DOI: 10.1177/1049731513500348

rsw.sagepub.com

and Controversies

Jeffrey S. Porter1 and Edwin Risler2

Abstract

Purpose: Assess the new alternative Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) model for per-

sonality disorders (PDs) as it is seen by its creators and critics. Method: Follow the DSM revision process by monitoring the

American Psychiatric Association website and the publication of pertinent journal articles. Results: The DSM-5 PD Work Group’s

proposal was not included in the main diagnostic section of the new DSM, but it was published in the section devoted to emerging

models. The alternative DSM-5 PD constructs are radically different from those found in DSM, fourth edition, text revision.

Discussion: There are some positive conceptual changes in the new model, but reliability and validity are not generally

improved. However, social workers may be able to benefit from the use of the personality trait domains/facets of the alternative

model.

Keywords

DSM-5, personality disorders, social work, criticisms

Introduction current approach to personality disorders,’’ an ‘‘alternative

DSM-5 model for personality disorders’’ was included (APA,

Used widely by social workers, psychiatrists, psychologists,

2013, p. 761). This alternative approach uses a dimensional

and other mental health professionals, personality disorder

severity/trait model to describe PD, wherein four PD categories

(PD) diagnoses came to the forefront in the third edition of the

have been eliminated completely. The inclusion of two incon-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third

sistent diagnostic systems for the same categories in DSM-5 is

edition (DSM-III) with their relocation to the newly introduced

indicative of a lack of satisfaction with the DSM-IV-TR PDs on

Axis II. The three DSM versions that followed made many

the part of researchers and clinicians. It also reflects the wide

changes to the PD criteria, with some being major and some

range of opinions about the best way of improving PD diagno-

being minor. For example, changing some PD criterion sets sis. Most importantly, though, it signifies the APA’s present

from monothetic—that is, requiring that all criteria be met—

reluctance to make radical changes to the PD diagnoses without

to polythetic—that is, requiring that only some criteria be

sufficient time to build empirical support for them.

met—was a major change. More minor changes included

Arguments about the need for major changes to the PD diag-

rewording specific PD criteria. Even the most minor of these

nostic criteria in the new DSM are, themselves, nothing new,

changes had a powerful impact on the prevalence of PD diag-

and have been described by many authors. For a full exposition

nosis in clinical settings. For example, the prevalence of schi-

of the problems with the DSM-IV-TR PDs, see O’Donohue,

zotypal PD based on DSM-III was 11%, but that prevalence

Fowler, and Lilienfeld (2007). Looking forward, we must ask

dropped to 1% with the DSM-III-R revision of increasing the this question: Is the alternative DSM-5 model for PD an

minimum required criteria from four to five (Widiger, 2007).

improvement over the DSM-IV-TR system that has been

Bearing this sensitive nature in mind, any changes to the PD

retained in the main diagnostic section of DSM-5? This article

criteria should be cautiously and deliberately made. Contrary

to most expectations, it appears that, with regard to PD, the

American Psychiatric Association (APA) acted accordingly 1

School of Social Work MSW Program, University of Georgia, Athens, GA,

in the newly published DSM. USA

2

The multiaxial structure has been removed in DSM, fifth School of Social Work, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, USA

edition (DSM-5), while the DSM, fourth edition, text revision

Corresponding Author:

(DSM-IV-TR) PD categories have been retained with only Jeffrey S. Porter, School of Social Work, University of Georgia, Athens, GA

minor text revisions. However, in an effort to introduce ‘‘a new 30602, USA.

approach that aims to address numerous shortcomings of the Email: jsp82@uga.edu

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

Porter and Risler 51

will assess how PD is viewed diagnostically in the alternative (APA, 2012, p. 9). Their conductive argument for retaining the

DSM-5 model by explicating the constructs and highlighting remaining six PDs includes ‘‘prevalence in community and

their most recent and relevant critiques. After a brief overview clinical populations, associated functional impairment, treat-

of PD in DSM-IV-TR, each of the changes to PD diagnosis in ment and prognostic significance, and . . . neurobiological and

the alternative DSM-5 model will be laid out in order of their genetic studies’’ (APA, 2012, p. 9).

appearance in the general PD criteria. After discussing these

changes and their support, relevant criticisms will be considered. Introduction of a Dimensional Conceptualization of PDs. The most

serious criticism of the PD constructs of DSM-IV-TR is that

they are entirely based on a false premise, namely, that PDs are

PDs in DSM-5 discrete diagnostic entities that are categorical in nature. But

this contradicts the findings of taxometric analysis of the PD

The Context of the New Changes: PD in DSM-IV-TR constructs, which find no discrete PD categories (Bradley,

Traditionally, PDs have been conceptualized categorically: Conklin, & Westen, 2007). For example, Conway, Hammen,

‘‘The diagnostic approach used in [DSM-IV-TR] represents and Brennan (2012) used latent class analysis, latent trait

the categorical perspective that Personality Disorders are qua- modeling, and factor mixture modeling to determine whether

litatively distinct clinical syndromes’’ (APA, 2000, p. 689). borderline PD (BPD) is best understood categorically, dimen-

With the publication of DSM-III, all PDs were assigned to sionally as the expression of one or more traits, or as a mixture

Axis II in an attempt to differentiate them from most other of both. They found that a dimensional latent trait model

mental disorders. There were 10 specific categories of PD best represented the disorder, and that a single trait (dubbed

in DSM-IV-TR: paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, antisocial, ‘‘BPD-ness’’) best explained the variation and severity in sub-

borderline, narcissistic, histrionic, dependent, avoidant, and jects (Conway, Hammen, & Brennan, 2012).

obsessive-compulsive. However, one could be diagnosed with A dimensional conceptualization potentially serves to resolve

‘‘personality disorder: not otherwise specified’’ using the gen- the problem of comorbidity across, and heterogeneity within, the

eral PD criteria even if they were not diagnosable with any of individual DSM-IV-TR PD categories by using transcategorical

the 10 specific categories (APA, 2000). and subcategorical factors to describe PD. A dimensional under-

The general criteria of PD in DSM-IV-TR required an standing can provide more coverage than the existing categories

enduring pattern of behavior or inner experience in two of the by allowing for the description of atypical personality patholo-

following realms: cognition, affect, interpersonal functioning, gies. At the same time, a potential deficit to such an understand-

or impulse control. The pattern must have begun by early adult- ing is the necessary establishment of, perhaps, arbitrary cutoffs

hood and be inflexible across time and circumstance. It must that are essential to the binary decisions of clinical practice.

cause distress or functional impairment, must not be better Examples of these binary choices include the decisions to admit

accounted for by a general medical condition or the effects of or not admit and treat or not treat. However, cutoffs for other

a substance, and must defy cultural expectations (APA, 2000). continuous variables and their related disorders in medical

practice, such as blood pressure and hypotension, have been

established with high treatment utility, so this may not prove

Outline of the Changes in the Alternative DSM-5 Model

to be a serious problem for a dimensional conceptualization of

for PD PD (Dowson & Grounds, 1995; Widiger, 2007).

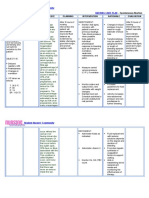

There are eight primary changes to the PD diagnostic con-

structs in the alternative DSM-5 model: (a) removal of four Introduction of a Functional Impairment Severity Rating Scale. The

PD categories, (b) introduction of a dimensional conceptualiza- DSM-5 PD Work Group incorporated into the new general

tion of PDs, (c) introduction of a functional impairment sever- PD criteria a 5-point rating scale to specify the type and degree

ity rating scale, (d) introduction of pathological personality of functional impairment found in patients. The Criterion

trait descriptors, (e) elimination of the strict temporal stability A requires ‘‘Moderate or greater impairment in personality

criterion, (f) elimination of the Axis I exclusion, (g) elimination functioning, manifested by difficulties in two or more of the

of the conduct disorder requirement for antisocial PD, and (h) following areas: (1) Identity, (2) Self-direction, (3) Empathy,

introduction of the category PD-trait specified (PDTS). or (4) Intimacy’’ (APA, 2013, p. 770). The criterion is polythetic

in that significant impairment in two categories is required to

Removal of Four PD Categories. The DSM-5 PD Work Group meet the criterion. The 5-point scale ranges from 0 (healthy func-

chose to eliminate four DSM-IV-TR PD categories, namely, tioning) to 4 (extreme impairment; APA, 2013, pp. 775–778).

paranoid, schizoid, histrionic, and dependent PDs (APA, Functional impairment of identity is measured according to

2012). The Work Group justifies the deletion of the first three the stability of sense of self, adherence to role-appropriate

of these PDs by first stating that ‘‘there are almost no empirical boundaries, and level, regulation, and tolerance of self-

studies focused explicitly on [them]’’ and second by noting that esteem. Impairment of self-direction considers coherence of

the trait compositions of all four were too simple for their inclu- goals, standards of behavior, and awareness of subjective expe-

sion. For example, the single DSM-5 trait facet of suspicious- rience. Degree of empathic impairment is measured by the

ness covers all of the DSM-IV-TR paranoid PD criteria level of understanding others’ motivations and experiences,

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

52 Research on Social Work Practice 24(1)

level of understanding and toleration of others’ perspectives, accurately describe dispositions associated with PD (APA,

and awareness of one’s own effects on others. Finally, level 2012, p. 7). That the trait model is somehow related to the FFM

of intimacy functioning is determined by existence and mainte- grants it credibility, as there is a significant amount of empiri-

nance of multiple satisfying relationships, desire for close rela- cal literature that relates the DSM-IV-TR PD categories to the

tionships, capacity for cooperation, and mutuality of regard FFM (APA, 2012; Miller, Morse, Nolf, Stepp, & Pilkonis,

reflected in interpersonal behavior (APA, 2013, p. 762). 2012). Field trials have demonstrated relatively good correla-

According to the Work Group, Criterion A is beneficial to tions (r ¼ .62 to .75) between the DSM-5 traits and the retained

the PD constructs because research ‘‘indicates that generalized DSM-IV-TR PD categories, while the test–retest reliability of

severity is the most important single predictor of concurrent the five trait domains has been positive (ICC ¼ .765 to .857;

and prospective dysfunction in assessing personality psy- APA, 2012, p. 8).

chopathology . . . ’’ (APA, 2012, p. 5). The self-other differen- A major benefit of including Criterion B is that the excessive

tiation enables the development and implementation of comorbidity among PDs is greatly reduced or, perhaps, even

superior treatment interventions and informs a more accurate resolved. This is because PD traits can and do overlap across

prognosis (APA, 2012). Furthermore, self and interpersonal PD categories as with, for example, impulsivity in BPD and anti-

functioning is not only consistent with the theoretical aspects social PD. But this does not threaten the construct validity of the

of PD, such as cognitive-behavioral, interpersonal, psychody- diagnostic constructs because any comorbidity that exists is an

namic, attachment, developmental, social cognitive, and evolu- accurate measurement of real phenomena. Criterion B also

tionary theories, but is also widely considered ‘‘a key aspect of serves to describe reliable variation within PDs, helping, in con-

personality pathology in need of clinical attention’’ (APA, junction with Criterion A, to differentiate between different PD

2012, p. 7). Finally, the test–retest reliability of Criterion A categories, as well as between subtypes within PDs (APA,

used by untrained, experienced clinicians was minimally ade- 2012).

quate (intraclass correlation coefficient [ICC] ¼ .416) in field Another problem that Criterion B resolves is that of the tem-

trials (APA, 2012). This reliability may increase as DSM-5 poral stability of PDs. In DSM-IV-TR, the general criteria for

training becomes more prevalent. PD stated that PD is stable across time (APA, 2000, p. 689).

Many of the DSM-IV-TR criteria can be described using The problem was that within the categorical conceptualization

Criterion A. For example, BPD chronic emptiness and identity of PD of DSM-IV-TR, there was no explanation for this stabi-

disturbance are functional impairments related to the self, lity. Personality trait research, however, tells us that traits

while the characteristic ‘‘stable instability’’ of relationships can become stable to a significant degree in some individuals by the

be considered a functional impairment relating to both empathy age of 3, obtain an adult-like structure by school-age, and

and intimacy, the two subcategories of interpersonal function- increase in stability from then until at least 50 years (APA,

ing. The problem of comorbidity among PDs in DSM-IV-TR is 2012). By using traits to describe PDs, DSM-5 improves upon

addressed by Criterion A in that multiple syndromes can share the explanatory scope and power of DSM-IV-TR, because it is

the same types of functional impairment without full-fledged the stability of the traits themselves that are responsible for the

co-occurrence. In addition, Criterion A helps describe genuine stability of the PDs (APA, 2012).

categorical subtypes found within DSM-IV-TR PDs, such as

overt and covert narcissistic PD (see Bradley et al., 2007), as Elimination of the Strict Temporal Stability Criterion, the Axis I

well as other heterogeneity, with relevant accuracy and Exclusion, and the Conduct Disorder Requirement for Antisocial

parsimony. PD. Criterion D of the general criteria for a PD in DSM-IV-

TR reads, ‘‘The pattern is stable and of long duration . . . ’’

Introduction of Pathological Personality Trait Descriptors. The next (APA, 2000, p. 689). The corresponding Criterion C in

major change to PDs in the alternative DSM-5 model is the DSM-5 adds the word ‘‘relatively,’’ and reads, ‘‘The impair-

addition of a set of pathological personality trait descriptors. ments in personality functioning and the individual’s personal-

The new Criterion B requires ‘‘One or more pathological per- ity trait expression are relatively [emphasis added] stable

sonality trait domains OR specific trait facets within across time . . . ’’ (APA, 2013, p. 761). This change makes for

domains . . . ’’ (APA, 2013, p. 770). The Work Group has a more accurate portrayal of PD, and is based on empirical evi-

devised a set of five trait domains, which are further defined dence showing PD symptoms to fluctuate in their expression

by 25 trait facets (see APA, 2013, pp. 779–781). For each across time, as well as the clinical course of PD patients, which

patient, the clinician will address all trait domains and facets, tends toward remission (APA, 2012).

giving a dimensional rating according to the level of expression Some PDs in DSM-IV-TR, such as paranoid, schizoid, schi-

of each trait. Criterion B is versatile in that it can be used to zotypal, and antisocial PDs, have an ‘‘Axis I Exclusion.’’ Cri-

describe maladaptive personality traits of all patients, whether terion D of antisocial PD, for example, states that ‘‘the

or not they are diagnosable with a PD. occurrence of antisocial behavior is not exclusively during the

The DSM-5 PD Work Group claims that the Criterion B trait course of schizophrenia or a manic episode’’ (APA, 2000, p.

model is ‘‘an extension of the Five Factor Model’’ (FFM) of 706). The DSM-5 PD Work Group found these exclusions to

normal personality traits, but also includes the more extreme be inconsistent and failing to take into account the possibility

and maladaptive personality traits that are necessary to of heterotypic continuity, and, therefore, deleted them from the

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

Porter and Risler 53

criteria of all PD categories (APA, 2013, pp. 764–770). Conse- dimensional trait model is the best fit for BPD. Concerning the

quently, within the alternative DSM-5 model, an individual can use of a hybrid categorical/dimensional model in DSM-5, Con-

be diagnosed with antisocial PD, even when the symptoms are way et al. (2012) conclude that ‘‘the current analysis reveals

only present during manic episodes. relatively poor fit for a hybrid latent structure of BPD . . . ’’

Finally, the Work Group eliminated the DSM-IV-TR (p. 800). They add that their research suggests that different

requirement of conduct disorder for the diagnosis of antisocial traits should be weighted differently in diagnosis, rather than

PD (APA, 2000, 2013, pp. 764–765). To justify this change, the uniformly as they are in DSM-5. Significant limitations to this

Work Group notes that antisocial PD is no different from any study include the fact that all subjects in the sample were 20

other PD in terms of pathological antecedents or precursors years of age and that subjects with maternal depression were

in childhood or adolescence (APA, 2012). By deleting this overselected. The former of these is potentially problematic

from the alternative criteria, the PD categories are more consis- because many symptoms of BPD, such as impulsivity and sui-

tent and streamlined. cidality, vary according to age, while the overselection may

have influenced the symptom presentation of BPD in the

Introduction of PDTS. All PD categories in the alternative DSM-5 subjects (Conway et al., 2012).

model follow the structure of the general criteria and only differ

in the levels and types of functional impairment (Criterion A)

and the presence and expression of maladaptive personality

Deleting Half of the DSM-IV-TR PD Categories

trait domains and facets (Criterion B). For all PDs that do not The PD Work Group removed 4 of the 10 PD categories found

fall within the six specific categories, there is the category of in DSM-IV-TR. According to the Work Group, ‘‘critiques of

PDTS. The criteria for this diagnosis are the same as those for the DSM-5 proposal have almost universally been against the

the general PD diagnosis, but the clinician must include the deletion of any of the DSM-IV PD types,’’ based on their treat-

patient’s specific levels and types of functional impairment, ment utility and heuristic value (APA, 2012, p. 12). Mullins-

as well as the patient’s specific maladaptive personality trait Sweatt, Bernstein, and Widiger (2012, pp. 691–692) make the

domains or trait facets (APA, 2013, pp. 770). PDTS will pro- most recent argument against deleting specific categories,

vide more coverage for atypical or unique PD. pointing out that ‘‘there is perhaps nothing more significant

to the field of personality disorder research than the inclusion

of diagnostic categories within the professional society’s offi-

Criticisms of the DSM-5 PD Constructs cial diagnostic manual.’’ They argue that there is not ‘‘a broad

There have been far too many criticisms of the alternative consensus of expert clinical opinion’’ to eliminate any PD cate-

DSM-5 PD constructs to include them all in this article. How- gory; nor is there a sufficient lack of validity or utility in any

ever, most criticisms have been addressed in the Work Group’s PD to remove it from the DSM. Consensus and validity/utility

Rationale for the Proposed Changes to the Personality Disor- were requirements explicitly declared by the PD Work Group

ders Classification in DSM-5, published on the DSM-5 website for the deletion of any PD category.

in May 2012 (APA, 2012). Therefore, the following section To demonstrate this, Mullins-Sweatt et al. (2012) asked

will focus on relevant critiques that have been written or members of the Association for Research on Personality Disor-

printed after May 2012. Other than Livesley and Verheul, none ders and the International Society for the Study of Personality

of the authors of the following criticisms were affiliated with Disorders to participate in an online survey concerning the util-

the DSM-5 PD Work Group. ity and validity of the DSM-IV-TR PD categories (n ¼ 520).

There was a 28% response rate, but only 130 surveys were

completed sufficiently to be included in analysis. The most

A ‘‘Hybrid’’ Model important findings were that a substantial majority of respon-

According to the Work Group, DSM-5 uses a ‘‘hybrid’’ catego- dents believed all PDs—especially antisocial and BPDs—to

rical/dimensional model for the PD constructs (APA, 2012, p. have validity, a majority considered all PDs except histrionic

4). This amounts to an implicit assertion that PDs make up dis- PD (HPD) to be ‘‘important’’ or ‘‘very important’’ in treatment

crete classes of persons but are ultimately constituted by incre- decisions, a majority felt that all PDs except HPD should

mental trait expression and functional impairment. However, ‘‘probably’’ or ‘‘definitely’’ not be deleted, and no majority

according to Conway et al. (2012), this assertion is incorrect, supported the deletion of any PD, including HPD.

at least when attributed to BPD, which is one of the DSM- To explain the dichotomy between ‘‘expert clinical opin-

IV-TR PD categories with the most existing research. To reach ion’’ and the Work Group’s decision to eliminate many of the

this conclusion, they used latent trait, latent class, and factor PDs in DSM-5, the researchers point to a literature review on

mixture modeling on data obtained from 700 twenty-year- the retention of PD categories conducted by the Work Group

olds using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis members themselves. The review ‘‘does not really appear to

II PDs (Conway et al., 2012). have been systematic or comprehensive in its coverage of its

In the analysis of the three modeling types, it was found that, validity and utility research’’ (Mullins-Sweatt, Bernstein, &

while there could be as many as four classes of BPD, it is more Widiger, 2012, p. 698). Specifically, the Work Group members

likely that these classes represent severity levels, and that a did not include a description of their inclusion/exclusion

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

54 Research on Social Work Practice 24(1)

criteria and failed to cover a significant number of studies that single, well-received study. Likewise, the specific dimensional

are pertinent to the validity and utility of PDs. Furthermore, ratings for the categories retained from DSM-IV-TR are based

summaries found within the literature review were sometimes on the opinions of various Work Group members, rather than

completely wrong (Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2012). As Mullins- on specific research.

Sweatt et al. (2012) take note, the Work Group asserts that Verheul’s (2012) next criticism is that the DSM-5 PD con-

there has been relatively little research done on the deleted structs are far too complex to be considered user-friendly

categories to establish their utility and validity. In response, among clinicians. First, Criterion B combines both pure dimen-

however, Mullins-Sweatt et al. make two points. First, absence sions (e.g., suspiciousness and hostility) and multidimensional

of evidence is not evidence of absence. Second, the lack of per- types (e.g., negative affectivity and detachment) within the

tinent research could just as easily be accounted for by a failure general criteria and the various retained PD categories. Second,

on the part of the PD field as by a lack of validity of the PD the alternative DSM-5 model for PDs has increased complexity

categories. Arguably, a consensus of opinion among research- when compared with DSM-IV-TR, as can be seen in terms of

ers is not sufficient reason to retain a PD category, but it should sheer number of criteria and words: DSM-IV-TR BPD involves

inspire some caution in the process of deleting that category. 9 criteria and 180 words, while the alternative DSM-5 BPD

involves 29 subcriteria and 375 words.

Third, the alternative DSM-5 criteria require significantly

Co-Occurrence of PDs and Schizophrenia Spectrum

more inference and interpretation than those in DSM-IV-TR.

Disorders (SSD) in DSM-5 For example, one criterion of BPD in DSM-IV-TR reads,

It was one of the implicit goals of the DSM-5 PD Work Group ‘‘markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of

to resolve the problem of excessive co-occurrence among the self,’’ while the corresponding criterion in DSM-5 reads,

PDs. While the new alternative DSM-5 Criteria A and B have ‘‘markedly impoverished, poorly developed or unstable self-

been successful in this regard concerning DSM-IV-TR Axis II image, often associated with excessive self-criticism’’ (APA,

disorders, the problem of high comorbidity between PDs and 2000, p. 710, 2013, p. 766). Finally, the new alternative DSM

DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders may have been exacerbated. model draws on sundry theoretical frameworks, including trait

Schroeder et al. (2012) conducted a study of day-clinic patients psychology (e.g., unstable emotional experiences and frequent

between 18 and 65 with SSD (n ¼ 45) in order to find the pre- mood changes) and psychoanalytic theory (e.g., ongoing

valence of PDs among this population. awareness of a unique self and maintains role-appropriate

The results showed that SSD subjects had a 20% likelihood of boundaries), making the criteria difficult to use for anyone

being diagnosable with a DSM-IV-TR PD category. While this without extensive knowledge in the pertinent areas. Not only

finding pertains to the DSM-IV-TR categories, the high level of does the complexity threaten acceptability among clinicians,

interrater agreement between the DSM-IV-TR and alternative but it also predicts poor interrater reliability, which has argu-

DSM-5 categories makes this relevant to the new DSM-5 PD ably been confirmed in field trials, depending on one’s statisti-

constructs. In addition, four correlations between study partici- cal threshold of acceptability (Verheul, 2012). ‘‘Interrater

pants and PD traits were found that were both significant and reliability is conditional to validity and utility,’’ writes Verheul,

medium to high in effect strength: schizotypy, paranoia, depres- ‘‘therefore, insufficient reliability is unacceptable and should

sivity, and avoidance (Schroeder et al., 2012). These levels of be followed by a rejection of the proposal in its current form’’

co-occurrence constitute a baseline by which we can judge the (2012, p. 370).

DSM-5 PD constructs. Schroeder et al. (2012) argue that we can John Livesley (2012), also a former member of the DSM-5

expect co-occurrence to increase with the use of DSM-5. This is PD Work Group, insists that, while a radical change is needed

because SSD patients typically meet PDTS Criterion A as a to address the poor structural and discriminant validity of

direct consequence of their SSD symptoms, often meet Criterion DSM-IV-TR, the final DSM-5 proposal, which is almost iden-

C, and necessarily meet Criteria D and E based on their overlap tical to the published alternative DSM-5 PD model, was too

with the respective SSD criteria. The only other requirement is flawed to accept. The first problem Livesley has is with the use

the presence of any of the 25 trait facets in Criterion B. This of categories in DSM-5 to describe PDs despite voluminous

problem is a threat to the construct validity of the DSM-5 PD evidence that such a framework is incorrect. Especially per-

criteria because it indicates that they have less than optimal spe- plexing is the Work Group’s own admission that this is the case

cificity. This study’s primary limitation is a small sample size. when they say that most DSM-IV-TR PD problems ‘‘can well

be understood as examples of the fact that personality features

and psychopathological tendencies do not tend to delineate

Criticisms by Former DSM-5 PD Work Group Members categories of persons in nature [emphasis added] . . . ’’ (2012,

Two of the 11 members of the DSM-5 PD Work Group p. 85). Livesley points out that the Work Group had a choice

resigned in protest in 2012 and have since written scathing cri- between tradition and empirical evidence and chose tradition.

ticisms of the alternative DSM-5 PD constructs. Verheul The problem is compounded by the attempt to combine both

(2012) calls attention first to the lack of empirical support for categories and dimensions. Livesley (2012) objects to the Work

the new general criteria, especially Criterion A, the levels of Group’s claim that the model is a ‘‘hybrid’’ of these two frame-

personality functioning, the support for which is limited to a works. In fact, by their very definitions, the two cannot be

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

Porter and Risler 55

united in a single system. The categorical framework assumes model is generally viewed positively, the continued use of cate-

that the features of the construct are discontinuous, while the gories alongside the dimensions is confounding.

dimensional framework makes the opposite assumption that The changes in the alternative DSM-5 PD model are no

features are continuous. doubt the correct categories of changes. The idea of using lev-

Livesley (2012) then calls attention to the fact that trait defi- els of functional impairment to measure PD has been well

nitions are not uniform across all PD categories in the alternative received, as has been the dimensional use of personality traits,

DSM-5 PD model. Impulsivity, for example, is found in both but the integral model selected by the Work Group appears to

antisocial and BPD categories; yet the phrase, ‘‘a sense of be seriously flawed. The state of PD diagnostics in the alterna-

urgency and self-harming behavior under emotional distress,’’ tive model seems to be only minimally and superficially

is only found within the BPD category, and not the antisocial improved as compared with DSM-IV-TR. While this article

PD category (p. 86). This inconsistent use of traits breaches the should not be perceived as an endorsement of the alternative

basic tenet of trait psychology that trait definitions are universal model, the decision to annex the alternative model to the main

across all people, with the only difference between individuals diagnostic section of DSM-5 may ultimately be a painful but

being their level of trait expression (Livesley, 2012). It is true necessary step that will bring us closer to a more valid DSM,

that the word ‘‘impulsivity’’ is traditionally used equivocally sixth edition revision.

in clinical settings, but Livesely sees this as another example The multiaxial system of previous editions of the DSM has

of the Work Group choosing tradition over empirical research. been eliminated in DSM-5. This involved the removal of Axis

Finally, Livesley (2012) questions the basis of Criterion B. IV, which was devoted to psychosocial and environmental prob-

The Work Group chose its own model, rather than choosing lems. The DSM-5 Task Force opted not to replace Axis IV with

one from the extant literature. This can be compared to the a new and original set of codes but rather refers clinicians to the

International Classification of Diseases (ICD)–11th Revision, relevant ICD–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification and ICD-

which will base differences between PDs on the FFM (Lives- 10 Z codes. Regardless of the acceptability of the ICD codes, the

ley, 2012). In fact, within the section of the Work Group’s most lack of attention devoted to psychosocial and environmental

recent rationale for the Criterion B trait model, of the seven problems by the DSM-5 work groups indicates that the social

citations made to lend it direct support, four of these were pri- work perspective was not given due consideration in the new

marily authored within the last 3 years by Robert Kreuger, a DSM. Indeed, it appears from the list of Task Force members

member of the DSM-5 PD Work Group (APA, 2012, p. 7). It that no one with a master of social work degree was included

appears that the Work Group may have opted for self- in any of the various DSM-5 work groups and study groups.

promotion over empirical evidence in formulating Criterion B. However, it is still possible that social workers may be able

to benefit from the alternative DSM-5 PD model. All clients

can be assessed using the personality trait domains and facets,

Discussion and Applications to Social Work whether or not they have a PD or any mental disorder at all.

The question that this article aims to address (are the DSM-5 Problems that maladaptive personality traits can pose for cli-

alternative PD diagnostic constructs an improvement over the ents range from barriers to employment to alienation of family

DSM-IV-TR constructs?) is difficult to answer: In some ways members or even social workers. Therefore, the DSM-5 system

they are better and in other ways they are not. It would seem that of personality trait domains (see APA, 2013, pp. 779–781),

the poor construct validity of the DSM-IV-TR PDs evidenced by which have shown good reliability, may prove to be a very use-

excessive comorbidity—they were too broadly constructed—has ful assessment tool for social workers and have the potential to

been replaced with a different type of poor construct validity— improve treatment plans, even if their validity is doubtful on

they are now too narrow. In a sense, coverage has been improved grounds other than reliability.

with the addition of the PDTS category, but coverage has been

diminished by the deletion of four other categories that, accord- Declaration of Conflicting Interests

ing to the PD research community, were both highly useful and The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to

valid (Mullins-Sweatt et al., 2012). The diagnostic reliability of the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

the new trait model (Criterion B) is a significant advancement,

but the reliability of the functional impairment (Criterion A) Funding

rating system could be far worse than that for any of the The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship,

DSM-IV-TR PD constructs. and/or publication of this article.

The lack of empirical evidence for the validity and associated

treatments of the PDs is as much of a problem for the alternative References

DSM-5 model as it was for DSM-IV-TR. The adjustment of American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical

Criterion C from ‘‘stable’’ to ‘‘relatively stable across time’’ is manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC:

a small step toward correcting the pejorative connotations of the Author.

PDs. Widespread disagreement about specific PD criteria in the American Psychiatric Association. (2012). Rationale for the pro-

alternative DSM-5 model is already underway. Finally, while the posed changes to the personality disorders classification in

use of dimensions to measure PDs in the alternative DSM-5 DSM-5. Retrieved from http://www.dsm5.org/Documents/

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

56 Research on Social Work Practice 24(1)

Personality%20Disorders/Rationale%20for%20the%20Proposed via dimensional personality traits? Implications for the DSM-5

%20changes%20to%20the%20Personality%20Disorders%20in% personality disorder proposal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology,

20DSM-5%205-1-12.pdf 121, 944–950.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical Mullins-Sweatt, S. N., Bernstein, D. P., & Widiger, T. A. (2012).

manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. Retention or deletion of personality disorder diagnoses for DSM-

Bradley, R., Conklin, C. Z., & Westen, D. (2007). Borderline person- 5: An expert consensus approach. Journal of Personality Disor-

ality disorder. In W. O’Donohue, K. Fowler & S. Lilienfeld (Eds.), ders, 26, 689–703.

Personality disorders: Toward the DSM-V (pp. 167–201). Thou- O’Donohue, W., Fowler, K. A., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (Eds.). (2007).

sand Oaks, CA: Sage. Personality disorders: Toward the DSM-V (1-19). Thousand Oaks,

Conway, C., Hammen, C., & Brennan, P. (2012). A comparison of CA: Sage.

latent class, latent trait, and factor mixture models of DSM-IV bor- Schroeder, K., Hoppe, A., Andresen, B., Naber, D., Lammers, C., &

derline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 26, Huber, C. G. (2012). Considering DSM-5: Personality diagnostics

793–803. in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Psychiatry:

Dowson, J. H., & Grounds, A. T. (1995). Personality disorders: Rec- Interpersonal and Biological Processes, 75, 120–134.

ognition and clinical management. Cambridge, England: Cam- Verheul, R. (2012). Personality disorder proposal for DSM-5:

bridge University Press. A heroic and innovative but nevertheless fundamentally flawed

Livesley, J. (2012). Tradition versus empiricism in the current DSM-5 attempt to improve DSM-IV. Clinical Psychology and Psychother-

proposal for revising the classification of personality disorders. apy, 19, 369–371.

Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 22, 81–90. Widiger, T. A. (2007). Alternatives to DSM-IV. In W. O’Donohue, K.

Miller, J. D., Morse, J. Q., Nolf, K., Stepp, S. D., & Pilkonis, P. A. Fowler & S. Lilienfeld (Eds.), Personality disorders: Toward the

(2012). Can DSM-IV borderline personality disorder be diagnosed DSM-V (pp. 21–40). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Downloaded from rsw.sagepub.com at GEORGIAN COURT UNIV on April 16, 2015

You might also like

- Dimensional PsychopathologyFrom EverandDimensional PsychopathologyMassimo BiondiNo ratings yet

- Art 2Document8 pagesArt 2Altin CeveliNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality DisordersDocument7 pagesAn Overview of The DSM-5 Alternative Model of Personality DisordersJosé Ignacio SáezNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Personality DisorderDocument19 pagesAssessment of Personality DisorderTanyu Mbuli TidolineNo ratings yet

- APA - DSM 5 Personality Disorder PDFDocument2 pagesAPA - DSM 5 Personality Disorder PDFKremlin PandaanNo ratings yet

- 2012 - Krueger Et Al - Initial Construction of A Maladaptive Personality TraitDocument12 pages2012 - Krueger Et Al - Initial Construction of A Maladaptive Personality TraitMaria Emilia WagnerNo ratings yet

- Art 1Document10 pagesArt 1Altin CeveliNo ratings yet

- The Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Version 2 (PDM-2) : Assessing Patients For Improved Clinical Practice and ResearchDocument25 pagesThe Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual Version 2 (PDM-2) : Assessing Patients For Improved Clinical Practice and ResearchSilvia R. AcostaNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 Personality Disorder PDFDocument2 pagesDSM 5 Personality Disorder PDFRita HenriquesNo ratings yet

- Personality Disorder Intro SampleDocument17 pagesPersonality Disorder Intro SampleCess NardoNo ratings yet

- Personality Disorders DSM-V Fact SheetDocument2 pagesPersonality Disorders DSM-V Fact SheetTinaLiuNo ratings yet

- PID5IPIPIRT AcceptedDocument40 pagesPID5IPIPIRT AcceptedIoana VoinaNo ratings yet

- Busch 2016Document9 pagesBusch 2016Jane DoeNo ratings yet

- Zimmermann 2012Document12 pagesZimmermann 2012Ekatterina DavilaNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 Brief Overview: Course OutlineDocument13 pagesDSM-5 Brief Overview: Course OutlineFranz Sobrejuanite GuillemNo ratings yet

- DSM 5 - DSM 5Document7 pagesDSM 5 - DSM 5Roxana ClsNo ratings yet

- Opinions of People Who Self-Identify With Autism and Asperger's On DSM-5 CriteriaDocument11 pagesOpinions of People Who Self-Identify With Autism and Asperger's On DSM-5 CriteriaAndrés SánchezNo ratings yet

- S169726001400012XDocument11 pagesS169726001400012XAna SandovalNo ratings yet

- World Psychiatry - 2021 - Mulder - The Evolving Nosology of Personality Disorder and Its Clinical UtilityDocument2 pagesWorld Psychiatry - 2021 - Mulder - The Evolving Nosology of Personality Disorder and Its Clinical UtilityPedro Gabriel LorencettiNo ratings yet

- Psychometric Properties of The Personality Inventory For Dsm-5 in A Romanian Community SampleDocument18 pagesPsychometric Properties of The Personality Inventory For Dsm-5 in A Romanian Community SampleDianaStanciuNo ratings yet

- Issues Regarding The Proposed DSM 5 Personality Disorders in Geriatric Psychology and PsychiatryDocument5 pagesIssues Regarding The Proposed DSM 5 Personality Disorders in Geriatric Psychology and PsychiatryRangga YudhaNo ratings yet

- Furnham Et Al Psychology 2014: A Review of The Measures Designed To Assess DSM-5 Personality DisordersDocument43 pagesFurnham Et Al Psychology 2014: A Review of The Measures Designed To Assess DSM-5 Personality DisordersRiverNo ratings yet

- Clinical Utility of The Alternative Model of Personality Disorders: A 10th Year Anniversary ReviewDocument35 pagesClinical Utility of The Alternative Model of Personality Disorders: A 10th Year Anniversary ReviewAnusha KumarasiriNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Disorders - Narcissistic and Histrionic Personality Disorders 2020Document15 pagesThe Cambridge Handbook of Personality Disorders - Narcissistic and Histrionic Personality Disorders 2020Aline RangelNo ratings yet

- Personality Inventory For DSM-5 (PID-5) in Clinical Versus Nonclinical Individuals: Generalizability of Psychometric FeaturesDocument12 pagesPersonality Inventory For DSM-5 (PID-5) in Clinical Versus Nonclinical Individuals: Generalizability of Psychometric FeaturesJasmine BurgosNo ratings yet

- Personality Traits in The DSM-5: Journal of Personality AssessmentDocument9 pagesPersonality Traits in The DSM-5: Journal of Personality AssessmentFlorin IancNo ratings yet

- Psych 2014093011461253 PDFDocument42 pagesPsych 2014093011461253 PDFjuanpaulomunera2No ratings yet

- Berghuis Et Al., GAPD CP&P 2012Document14 pagesBerghuis Et Al., GAPD CP&P 2012Feras ZidiNo ratings yet

- Skodol Et Al 2011 Part IIDocument18 pagesSkodol Et Al 2011 Part IIssanagavNo ratings yet

- Professional Psychology: Research and PracticeDocument14 pagesProfessional Psychology: Research and PracticeRodica FloreaNo ratings yet

- Waugh 2017Document22 pagesWaugh 2017Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Implications of DSM-5 Personality Traits For Forensic (Hopwood y Sellbom, 2013)Document10 pagesImplications of DSM-5 Personality Traits For Forensic (Hopwood y Sellbom, 2013)carmenNo ratings yet

- ZimmermannDocument19 pagesZimmermannarielNo ratings yet

- Bender 2011Document16 pagesBender 2011Alissa EspejoNo ratings yet

- El DSM VDocument19 pagesEl DSM VRoxanaSantillan100% (1)

- Dsm-5 and Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) : An Opportunity For Identifying Asd SubtypesDocument6 pagesDsm-5 and Autism Spectrum Disorders (Asds) : An Opportunity For Identifying Asd SubtypesLuis SeixasNo ratings yet

- Pedophilia ASBDocument14 pagesPedophilia ASBbarakaNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 and Psychotic and Mood Disorders: George F. Parker, MDDocument9 pagesDSM-5 and Psychotic and Mood Disorders: George F. Parker, MDMonika LangngagNo ratings yet

- Critically Evaluate The Difference Between DSM 4 and DSM 5EVFDocument3 pagesCritically Evaluate The Difference Between DSM 4 and DSM 5EVFNaganajita ChongthamNo ratings yet

- Personality Inventory For DSMDocument11 pagesPersonality Inventory For DSMSubhan UllahNo ratings yet

- The Future Arrived: ViewpointDocument2 pagesThe Future Arrived: ViewpointDaniela Ocampo BoteroNo ratings yet

- NIH Public AccessDocument39 pagesNIH Public AccessnigoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 2Document21 pagesJurnal 2Mega MuzdalifahNo ratings yet

- Yoa15011 827 837Document11 pagesYoa15011 827 837Junior BonfáNo ratings yet

- Escalas de Funcionamiento y GravedadDocument12 pagesEscalas de Funcionamiento y Gravedadantonio vallenasNo ratings yet

- Latent Structure Analysis of DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder CriteriaDocument8 pagesLatent Structure Analysis of DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder CriteriaDanutza CezNo ratings yet

- Schema Therapy Conceptualization of Personality Functioning and Traits in ICD 11 and DSM 5Document12 pagesSchema Therapy Conceptualization of Personality Functioning and Traits in ICD 11 and DSM 5María González MartínNo ratings yet

- Díaz-Batanero 2017 - Spanish PID-5-SF in Dual Diagnosis PatientsDocument16 pagesDíaz-Batanero 2017 - Spanish PID-5-SF in Dual Diagnosis PatientsNeider Castro ZúñigaNo ratings yet

- The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)Document14 pagesThe Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)PeepsNo ratings yet

- The Addiction Casebook - Chap 01Document10 pagesThe Addiction Casebook - Chap 01Glaucia MarollaNo ratings yet

- A Psychometric Review of The Personality Inventory For DSM 5 PID 5 Current Status and Future DirectionsDocument21 pagesA Psychometric Review of The Personality Inventory For DSM 5 PID 5 Current Status and Future DirectionsMilan StefanovicNo ratings yet

- Thomasetal 2015 Prevalenceof ADHDAsystematicreviewandmetaaDocument11 pagesThomasetal 2015 Prevalenceof ADHDAsystematicreviewandmetaajuliana toledoNo ratings yet

- Schema Therapy Conceptualization of Personality Functioning and Traits in ICD-11 and DSM-5Document13 pagesSchema Therapy Conceptualization of Personality Functioning and Traits in ICD-11 and DSM-5benoitmonchotteNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument32 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptAltin CeveliNo ratings yet

- Final DSM 5 Approved by American Psychiatric AssociationDocument2 pagesFinal DSM 5 Approved by American Psychiatric Associationdjwa163No ratings yet

- ++PTSD in DSM5 Și ICD 11 PDFDocument10 pages++PTSD in DSM5 Și ICD 11 PDFBianca DineaNo ratings yet

- DSM-5 Essentials: The Savvy Clinician's Guide to the Changes in CriteriaFrom EverandDSM-5 Essentials: The Savvy Clinician's Guide to the Changes in CriteriaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Exploring What It Effectively Means to Manage Carpal Tunnel Syndrome’S: Physical, Social, and Emotional Crucibles in a Return to Work ProgramFrom EverandExploring What It Effectively Means to Manage Carpal Tunnel Syndrome’S: Physical, Social, and Emotional Crucibles in a Return to Work ProgramNo ratings yet

- Dobkin 1994Document10 pagesDobkin 1994Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Edwards 2004Document24 pagesEdwards 2004Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Post 1996Document12 pagesPost 1996Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Hazarika 2018Document15 pagesHazarika 2018Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Gibbins 1960Document24 pagesGibbins 1960Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Solty 2009Document10 pagesSolty 2009Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Pozolotina 2017Document7 pagesPozolotina 2017Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Neutralization and SublimationDocument18 pagesNeutralization and SublimationStella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Crockett 2009Document19 pagesCrockett 2009Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Sansone 2013Document8 pagesSansone 2013Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Adams2009 CheckDocument6 pagesAdams2009 CheckStella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Racine 2020Document3 pagesRacine 2020Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Cropley 1999Document9 pagesCropley 1999Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- CE Definitions Biz ModelDocument12 pagesCE Definitions Biz ModelPradip sahNo ratings yet

- Bremner 2000Document12 pagesBremner 2000Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Frissa 2016Document9 pagesFrissa 2016Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Waugh 2017Document22 pagesWaugh 2017Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Briere 2001Document14 pagesBriere 2001Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Cristofaro 2013Document8 pagesCristofaro 2013Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- Form Pain DetectDocument2 pagesForm Pain Detectalvin100% (4)

- POST ACTIVITY REPORT-MH Caravan-PalananDocument5 pagesPOST ACTIVITY REPORT-MH Caravan-PalananKeith Clarence BunaganNo ratings yet

- Nursingcrib Com NURSING CARE PLAN Spontaneous AbortionDocument2 pagesNursingcrib Com NURSING CARE PLAN Spontaneous AbortionMina RacadioNo ratings yet

- Lyme, CF ProtocolDocument36 pagesLyme, CF ProtocolTheresa Dale100% (1)

- Lecture 1Document38 pagesLecture 1Yong Hao Jordan JinNo ratings yet

- Vaginal DischargeDocument1 pageVaginal DischargeRAHMANo ratings yet

- GMP and Preparation in Hospital Pharmacies - Bouwman and Andersen 19 (5) - 469 - European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy - Science and PracticeDocument4 pagesGMP and Preparation in Hospital Pharmacies - Bouwman and Andersen 19 (5) - 469 - European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy - Science and Practicecarbou0% (1)

- IMAEC Disinfectant Product Catalogue - DigitalCopy - April - 2023Document32 pagesIMAEC Disinfectant Product Catalogue - DigitalCopy - April - 2023ToureNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavior Modification: Characteristics ChartDocument9 pagesCognitive Behavior Modification: Characteristics ChartMadhu sudarshan ReddyNo ratings yet

- Patients Discharged From Medium Secure Forensic Psychiatry Services: Reconvictions and Risk FactorsDocument9 pagesPatients Discharged From Medium Secure Forensic Psychiatry Services: Reconvictions and Risk FactorsIrisha AnandNo ratings yet

- Telemetry Recognition WorkbookDocument29 pagesTelemetry Recognition WorkbookQueenNo ratings yet

- Argumentative Essay REGDocument18 pagesArgumentative Essay REGMaeva AlexandreNo ratings yet

- Aat Dementia PDFDocument3 pagesAat Dementia PDFMinodora MilenaNo ratings yet

- Retirement Planning Mistakes Undermining The Post Retirement Adjustment and Well BeingDocument17 pagesRetirement Planning Mistakes Undermining The Post Retirement Adjustment and Well BeingMehedi HasanNo ratings yet

- Golden - Plaza: Evolution of Health and FitnessDocument11 pagesGolden - Plaza: Evolution of Health and FitnessGodzilla555100% (1)

- ThesisDocument35 pagesThesisMuhdFaris67% (3)

- Mcgill OsceDocument77 pagesMcgill OsceandrahlynNo ratings yet

- Case Study Stroke RehabilitationDocument1 pageCase Study Stroke RehabilitationJanantik PandyaNo ratings yet

- Urine Indican Excretion in Malabsorptive DisordersDocument8 pagesUrine Indican Excretion in Malabsorptive DisordersBiancake Sta. AnaNo ratings yet

- Uwinnipeg Homestay Handbook For Short Term Students v111919Document11 pagesUwinnipeg Homestay Handbook For Short Term Students v111919MUSSIE MIHRETABNo ratings yet

- IV ScriptDocument3 pagesIV ScriptRica AcuninNo ratings yet

- Megan Haky: M.M.Haky@eagle - Clarion.eduDocument2 pagesMegan Haky: M.M.Haky@eagle - Clarion.eduapi-285540869No ratings yet

- Management of Patients With Special Health Care NeedsDocument30 pagesManagement of Patients With Special Health Care NeedsEslam HafezNo ratings yet

- MPCE 024-2nd Yr En.2101329657 - Sekhar ViswabDocument34 pagesMPCE 024-2nd Yr En.2101329657 - Sekhar ViswabSekhar ViswabNo ratings yet

- 7 Benefits and Uses of CBD Oil (Plus Side Effects) : NutritionDocument18 pages7 Benefits and Uses of CBD Oil (Plus Side Effects) : NutritionAnonymous yCpjZF1rFNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Nutrition Education On Knowledge, Attitude, and Practiceregarding Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Female Adolescent Studentsin JordanDocument7 pagesThe Impact of Nutrition Education On Knowledge, Attitude, and Practiceregarding Iron Deficiency Anemia Among Female Adolescent Studentsin JordanAppierien 4No ratings yet

- Confined Space RescueDocument490 pagesConfined Space RescueleeNo ratings yet

- Drug Study and LaboratoryDocument13 pagesDrug Study and LaboratoryGEOMHAI CATBAGANNo ratings yet

- Drug Study Case 1Document37 pagesDrug Study Case 1Maria Charis Anne IndananNo ratings yet