Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Passivation of Stainless Steel

Uploaded by

Aleksandar StojanovicOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Passivation of Stainless Steel

Uploaded by

Aleksandar StojanovicCopyright:

Available Formats

Passivation of Stainless Steel

Stainless steel is an alloy of steel – more iron than anything else – with chromium and sometimes another element such

as nickel or molybdenum. Stainless steel is not resistant to chemical or physical attack. The corrosion resistance

depends on the formation of a passive surface. Stainless steel is only “stainless” when the surface oxidizes with

chromium and other elements to develop a protective film that resists further oxidation. This protected oxide film is

considered a passive surface.

To passivate stainless steel, a minimum of 10.5-12% chromium is

needed. Oxygen combines with chromium to create a film of

chromium oxide (Cr2O3) on the surface. Oxygen must be present to

replenish this film.

When stainless steel is newly made, it is cleaned of oils and greases

used in the fabrication process. Acid, usually nitric, is used to remove

free iron from the surface. Slowly and naturally, a passive layer

develops on the surface as the chromium reacts with oxygen in the

air. This layer is invisible and only a few molecules thick, but it

provides a barrier to prevent oxygen and moisture from reaching the

iron underneath.

Surface Damage

After stainless steel equipment has been installed and is in operation, the existing passive layer can be damaged or

removed by physical abrasion (brushing, grinding, scraping) or by chemical reactions. It can also be weakened by

physical damage due to expansion and contraction caused by heating and cooling. If this damage happens faster than

the passive layer can heal itself naturally, rusting will result.

The natural reaction of oxygen from the air combining with chromium from the steel to produce chromium oxide may

be interfered with by the processing going on or chemicals that are in contact with the surface. The regeneration of the

passive oxide layer might not be adequate to provide constant protection. A more effective passive layer can be

produced by chemical methods.

What is Chemical Passivation?

Chemical passivation is a two-step process. The first step is to remove any free iron or iron compound that is on the

surface, otherwise this iron will create a localized site where corrosion can continue. Acid is used to dissolve away the

iron and its compounds. The surface itself is not affected by this process. The second step is to use an oxidizer to force

the conversion of chromium metal on the surface to the oxide form. This will create the uniform chromium oxide

protective layer.

Greensboro Division / Corporate Headquarters Louisville Division Nashville Division

Phone: 336.393.0100 / 800.334.0231 Phone: 502.459.7475 / 800.459.7475 Phone: 615.822.3030 / 855.749.4820

Fax: 336.393.0140 Fax: 502.459.7633 Fax: 615.822.3031

www.mgnewell.com sales@mgnewell.com espanol@mgnewell.com

Historically, nitric acid was the most commonly used chemical method to passivate a stainless steel surface. Nitric is a

strong mineral acid so it can quickly dissolve all iron compounds and other trace metals that are on the surface. Nitric

acid is also a strong oxidizer so it can generate the chromium oxide layer at the same time. On the negative side, nitric

acid can be difficult to handle and dispose of after use.

Citric acid is becoming the choice for most processors for passivation. Citric acid is safer to use than nitric acid, is

biodegradable, produces fewer effluent concerns and is commonly used as a food ingredient itself. Citric acid does an

excellent job of cleaning iron from the surface, however it is not an oxidizer, so it cannot oxidize chromium – the

traditional 2nd step. Build-up of the protective layer is typically done with air oxidation.

“Confusion exists regarding the meaning of the term passivation. It is not necessary to chemically

treat a stainless steel to obtain the passive film; it forms spontaneously in the presence of oxygen.

Most frequently, the function of passivation is to remove free iron, oxides and other surface

contamination. For example, in the steel mill, the stainless steel may be pickled in an acid

solution, often a mixture of nitric and hydrofluoric acids to remove oxides formed in heat

treatment. Once the surface is cleaned and the bulk composition of the stainless steel is exposed

to air, the passive film forms immediately”

ASM Metals Handbook, Ninth edition, Vol. 13, page 550

When to Passivate

There is no simple rule that says when a piece of equipment must be passivated. The need will vary according to how

the equipment is being used and whether the surface has been damaged. Some companies will choose to passivate

processing equipment once per year as a scheduled maintenance procedure. Other companies will do it more frequently

because they are processing foods that are aggressive on the stainless steel. Aggressive foods are those that contain

high chloride levels and are acidic, for example salsa, tomato juice, etc. Plants that use water that has a naturally high

chloride level may have to passivate more frequently since the chloride will disrupt the protective layer.

Pharmaceutical companies that use ultra-pure water for injection (WFI) are known to passivate 4 times per year because

the high purity water itself is hard on the surface layer! Many times companies will passivate when they notice iron

deposits forming on the stainless steel and it is not coming from the water. There are test kits available from chemical

supply firms that will test for free surface iron. If a high level is found, it could be time to passivate.

www.mgnewell.com sales@mgnewell.com espanol@mgnewell.com

You might also like

- Why Do Metals Rust? An Easy Read Chemistry Book for Kids | Children's Chemistry BooksFrom EverandWhy Do Metals Rust? An Easy Read Chemistry Book for Kids | Children's Chemistry BooksNo ratings yet

- Pickling and Passivation - VecomDocument2 pagesPickling and Passivation - VecomSUmith K RNo ratings yet

- Corrosion and RustDocument9 pagesCorrosion and RustahmedNo ratings yet

- What Is PassivationDocument1 pageWhat Is PassivationTelma DavilaNo ratings yet

- Pickling and Passivation Processes ExplainedDocument4 pagesPickling and Passivation Processes ExplainedSHAOSHAN MANo ratings yet

- Pickling and PassivationDocument2 pagesPickling and PassivationJignesh ShahNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Chemical Treatment for Welding Stainless Steel and AluminiumDocument6 pagesThe Importance of Chemical Treatment for Welding Stainless Steel and AluminiumRahul MoottolikandyNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Pre FinalsDocument11 pagesCorrosion Pre FinalsbnolascoNo ratings yet

- Rusting of IronDocument11 pagesRusting of Ironharsh100% (1)

- Diversey PassivationofStainlessSteelDocument4 pagesDiversey PassivationofStainlessSteelSo MayeNo ratings yet

- Passivation ProcessDocument1 pagePassivation ProcesszlatkoNo ratings yet

- Maintaining Repairing and Cleaning Stainless SteelDocument2 pagesMaintaining Repairing and Cleaning Stainless SteelsaudimanNo ratings yet

- Sea Transport of Liquid Chemicals in Bulk PDFDocument131 pagesSea Transport of Liquid Chemicals in Bulk PDFDiana MoralesNo ratings yet

- Rust On Stainless Steel: (Oh My God. - . !)Document9 pagesRust On Stainless Steel: (Oh My God. - . !)pvirgosharmaNo ratings yet

- Corrosion and Protective CoatingDocument54 pagesCorrosion and Protective CoatingNeo MeltonNo ratings yet

- General Corrosion of Structural Steel LectureDocument81 pagesGeneral Corrosion of Structural Steel Lecturesureshs83No ratings yet

- Care and Cleaning of Iron - CCI Notes 9-6Document4 pagesCare and Cleaning of Iron - CCI Notes 9-6Dan Octavian PaulNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Sku3073Document13 pagesAssignment 2 Sku3073KHISHALINNI A/P M.MEGANATHANNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapter5Document10 pages10 Chapter5Dhananjay ShimpiNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Metal Coupling on Rusting of IronDocument14 pagesThe Effect of Metal Coupling on Rusting of IronSudhasathvik ReddyNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Prevention in Railway Coaches PDFDocument7 pagesCorrosion Prevention in Railway Coaches PDFnaveenjoy84No ratings yet

- Prevent Rust with Metal AlloysDocument14 pagesPrevent Rust with Metal AlloysSudhasathvik ReddyNo ratings yet

- Passivation and De-Passivation of Mild Steel SampleDocument3 pagesPassivation and De-Passivation of Mild Steel SampleRaza AliNo ratings yet

- Afsa Corrosion Pocket GuideDocument36 pagesAfsa Corrosion Pocket GuideNuno PachecoNo ratings yet

- Diversey PassivationofStainlessSteel PDFDocument4 pagesDiversey PassivationofStainlessSteel PDFYhing YingNo ratings yet

- What Is CorrosionDocument4 pagesWhat Is CorrosionOsransyah Os100% (1)

- Aluminium's Corrosion Resistance - Aluminium DesignDocument7 pagesAluminium's Corrosion Resistance - Aluminium DesignCarlos LuNo ratings yet

- Why Is Stainless Steel Corrosion ResistantDocument4 pagesWhy Is Stainless Steel Corrosion ResistantMELVIN MAGBANUANo ratings yet

- Galvanic Series: Why Metals Corrode?Document7 pagesGalvanic Series: Why Metals Corrode?Rey Francis FamulaganNo ratings yet

- Corrosion of Stainless SteelDocument10 pagesCorrosion of Stainless SteelRizky Ilham DescarianNo ratings yet

- Corrosion and Corrosion Theory 1.: Q 1.0.1 What Is Corrosion. or Define CorrosionDocument8 pagesCorrosion and Corrosion Theory 1.: Q 1.0.1 What Is Corrosion. or Define CorrosionmudassarNo ratings yet

- White Paper - Technical Guide To Engraving and Laser Passivation For Medical TechnologyDocument4 pagesWhite Paper - Technical Guide To Engraving and Laser Passivation For Medical Technologyjulianpellegrini860No ratings yet

- CorrosionDocument16 pagesCorrosionAerocfdfreakNo ratings yet

- Aluminium and CorrosionDocument12 pagesAluminium and CorrosionMehman NasibovNo ratings yet

- RUSTING OF IRON AND CORROSION PREVENTIONDocument15 pagesRUSTING OF IRON AND CORROSION PREVENTIONShamil Azha Ibrahim0% (1)

- PICKLING AN EXCELLENT SURFACE TREATMENT FOR ALUMINIUMDocument2 pagesPICKLING AN EXCELLENT SURFACE TREATMENT FOR ALUMINIUMMuchamadAsyhariNo ratings yet

- L O-3 4Document3 pagesL O-3 4KALOY SANTOSNo ratings yet

- CORROSION (Chapter 4)Document25 pagesCORROSION (Chapter 4)tanjali333No ratings yet

- File 574354919Document3 pagesFile 574354919lonaab33No ratings yet

- HeliCoil Technical Information Corrosion Screw ThreadsDocument6 pagesHeliCoil Technical Information Corrosion Screw ThreadsAce Industrial SuppliesNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Protection of Steel - Part Two - KEY To METALS ArticleDocument3 pagesCorrosion Protection of Steel - Part Two - KEY To METALS Articlekumarpankaj030No ratings yet

- Stainless Steel Chemical Tankers SUS 316 LNDocument66 pagesStainless Steel Chemical Tankers SUS 316 LNnarutoNo ratings yet

- Why Is Rusting An Undesirable PhenomenonDocument4 pagesWhy Is Rusting An Undesirable PhenomenonVon Jezzrel Jumao-asNo ratings yet

- IB1 MoreraMoisés RojasStiven TrejosGabrielDocument4 pagesIB1 MoreraMoisés RojasStiven TrejosGabrielGabriel TrejosNo ratings yet

- Proteksi InggrisDocument9 pagesProteksi Inggrisbo_lankNo ratings yet

- Corrosion and Protective CoatingsDocument51 pagesCorrosion and Protective CoatingsMuhammad AsifNo ratings yet

- RustDocument9 pagesRustxia luoNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Removal: Metals Oxygen Rusting Iron Oxide Salt Ceramics PolymersDocument1 pageCorrosion Removal: Metals Oxygen Rusting Iron Oxide Salt Ceramics PolymersIshan ChughNo ratings yet

- Materials and ProcessesDocument21 pagesMaterials and Processessamluvhouse05No ratings yet

- Passivation HistoryDocument5 pagesPassivation Historytahn eisNo ratings yet

- Aluminum OxidationDocument9 pagesAluminum OxidationTarkan OdabasiNo ratings yet

- BZG Chrome PlatingDocument4 pagesBZG Chrome PlatingCarl Jerome AustriaNo ratings yet

- Surface FinishingDocument7 pagesSurface Finishingcanveraza3122No ratings yet

- Spray Painting Unit 1.2Document17 pagesSpray Painting Unit 1.2arun3kumar00_7691821No ratings yet

- Stainless SteelDocument16 pagesStainless SteelAsfaq SumraNo ratings yet

- SchoolDocument17 pagesSchoolEjaz ul Haq kakarNo ratings yet

- Corrosion Problems Associated With Stainless SteelDocument11 pagesCorrosion Problems Associated With Stainless SteelVivek RathodNo ratings yet

- Pickling and PassivationDocument2 pagesPickling and PassivationVivi OktaviantiNo ratings yet

- Sheet Metalwork on the Farm - Containing Information on Materials, Soldering, Tools and Methods of Sheet MetalworkFrom EverandSheet Metalwork on the Farm - Containing Information on Materials, Soldering, Tools and Methods of Sheet MetalworkNo ratings yet

- To Begin: MantraDocument9 pagesTo Begin: MantraashissahooNo ratings yet

- Monthly Fire Extinguisher Inspection ChecklistDocument2 pagesMonthly Fire Extinguisher Inspection ChecklistisaacbombayNo ratings yet

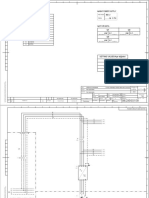

- EKO75 KW VST Air Cooled Electrical DiagramDocument13 pagesEKO75 KW VST Air Cooled Electrical DiagramBerat DeğirmenciNo ratings yet

- Fiber Crops - FlaxDocument33 pagesFiber Crops - Flaxmalath bashNo ratings yet

- Philips HD5 enDocument5 pagesPhilips HD5 enmohamed boufasNo ratings yet

- PDM TempDocument2 pagesPDM Tempamit rajputNo ratings yet

- Module 2 Chem 1Document25 pagesModule 2 Chem 1melissa cabreraNo ratings yet

- White Lies - Core RulebookDocument136 pagesWhite Lies - Core RulebookThiago AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- ON Code (Aci 318-77) : Commentary Building Requirements For Reinforced ConcreteDocument132 pagesON Code (Aci 318-77) : Commentary Building Requirements For Reinforced ConcreteAzmi BazazouNo ratings yet

- Tutorial - DGA AnalysisDocument17 pagesTutorial - DGA Analysisw automationNo ratings yet

- Dog Cake Recipe For Dozer's Birthday! - RecipeTin EatsDocument36 pagesDog Cake Recipe For Dozer's Birthday! - RecipeTin EatsZyreen Kate CataquisNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Level in A Tank Using Capacitive Type Level ProbeDocument13 pagesMeasurement of Level in A Tank Using Capacitive Type Level ProbeChandra Sekar100% (1)

- Fundamental aim training routines and benchmarksDocument8 pagesFundamental aim training routines and benchmarksAchilles SeventySevenNo ratings yet

- Aula 4 - Wooten - Organizational FieldsDocument28 pagesAula 4 - Wooten - Organizational FieldsferreiraccarolinaNo ratings yet

- HSB Julian Reyes 4ab 1Document3 pagesHSB Julian Reyes 4ab 1Kéññy RèqüēñåNo ratings yet

- Slovakia C1 TestDocument7 pagesSlovakia C1 TestĐăng LêNo ratings yet

- CH 2.2: Separable Equations: X F DX DyDocument9 pagesCH 2.2: Separable Equations: X F DX DyPFENo ratings yet

- Part 1Document52 pagesPart 1Jeffry Daud BarrungNo ratings yet

- Singaporean Notices To Mariners: Section ContentDocument35 pagesSingaporean Notices To Mariners: Section ContentGaurav SoodNo ratings yet

- Marketing 5 0Document23 pagesMarketing 5 0gmusicestudioNo ratings yet

- Tugas Bahasa Inggris-1Document8 pagesTugas Bahasa Inggris-1Nur KomariyahNo ratings yet

- 2 1 Flash Klasa 6 Mod 1b Test ExtendedDocument4 pages2 1 Flash Klasa 6 Mod 1b Test ExtendedMonika Ciepłuch-Jarema100% (1)

- Biologic License ApplicationDocument16 pagesBiologic License ApplicationJean Sandra PintoNo ratings yet

- Regulation 1 Regulation 2 Regulation 3 Regulation 4 Regulation 5 Regulation 6 Regulation 7 Regulation 8 Regulation 9 AppendixDocument10 pagesRegulation 1 Regulation 2 Regulation 3 Regulation 4 Regulation 5 Regulation 6 Regulation 7 Regulation 8 Regulation 9 AppendixAnonymous 7gJ9alpNo ratings yet

- Rainas, Lamjung: Office of Rainas MunicipalityDocument5 pagesRainas, Lamjung: Office of Rainas MunicipalityLakshman KhanalNo ratings yet

- GREEN AIR CONDITIONER Mechanical Presentation TopicsDocument9 pagesGREEN AIR CONDITIONER Mechanical Presentation TopicsCerin91No ratings yet

- Audit Keselamatan Jalan Pada Jalan Yogyakarta-Purworejo KM 35-40, Kulon Progo, YogyakartaDocument10 pagesAudit Keselamatan Jalan Pada Jalan Yogyakarta-Purworejo KM 35-40, Kulon Progo, YogyakartaSawaluddin SawalNo ratings yet

- Determining The Thickness of Glass in Airport Traffic Control Tower CabsDocument17 pagesDetermining The Thickness of Glass in Airport Traffic Control Tower CabsAdán Cogley CantoNo ratings yet

- CFD Answer KeyDocument12 pagesCFD Answer KeyRaahini IzanaNo ratings yet

- Surat Kecil Untuk TuhanDocument9 pagesSurat Kecil Untuk TuhanAsgarPurnamaNo ratings yet