Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hong 2011

Uploaded by

jamilkhannOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hong 2011

Uploaded by

jamilkhannCopyright:

Available Formats

48(11) 2339–2354, August 2011

Information and Communication

Technologies and the Geographical

Concentration of Manufacturing

Industries: Evidence from China

Junjie Hong and Shihe Fu

[Paper first received, December 2009; in final form, August 2010]

Abstract

Using the 2004 China economic census database, this paper examines the impact of

information and communication technologies (ICT) on the geographical concentration

of manufacturing industries, controlling for a broad set of other determinants of

industrial agglomeration. Contrary to the argument that ICT leads to more dispersion,

it is found that ICT promotes geographical concentration of industries. The results

are robust to different measures of ICT, at different geographical levels and to the

consideration of endogeneity.

1. Introduction

Economists have long recognised that of agglomeration economies is geographical

agglomeration—of both population and proximity. To be more specific, the demand

firms—in cities, yields economic benefits. for geographical proximity stems from the

In Marshall’s view (Marshall, 1920), firms demand for face-to-face communications,

of the same industry concentrate in a city to especially in an innovative business environ-

incorporate specialised labour pooling and ment where tacit, uncodifiable and rapidly

the availability of intermediate inputs, as well changing information is crucial to decision-

as information and knowledge spillovers. In making (Storper and Venables, 2004).

Jacobs’ opinion (Jacobs, 1961), firms of dif- Many recent studies have confirmed the

ferent industries concentrating in a city can existence and significance of agglomera-

facilitate cross-fertilisation of new ideas. In tion economies among firms and among

both arguments, the underlining determinant workers in cities. Further, economists have

Junjie Hong is in the School of International Trade and Economics, University of International Business

and Economics, Beijing, 100029, China. E-mail: hongjunjie@alumni.nus.edu.sg.

Shihe Fu is in the Research Institute of Economics and Management, Southwestern University of

Finance and Economics, Chengdu, China. E-mail: fush@swufe.edu.cn.

0042-0980 Print/1360-063X Online

© 2010 Urban Studies Journal Limited

DOI: 10.1177/0042098010388956

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2340 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

tried to disentangle the foundations of firm that agglomeration economies are localised

agglomeration. For example, Rosenthal and and decay with geographical distances. For

Strange (2001) examined the impact of example, Jaffe et al. (1993) found that pat-

knowledge spillovers, labour market pool- ent citations decrease when distance from

ing, input-sharing and natural advantage the company holding the patent increases.

on industrial agglomeration. Audretsch and Previous studies also found that business

Feldman (1996) found that industries that agglomeration economies (Rosenthal and

emphasise research and development (R&D) Strange, 2003) and labour market agglom-

are more likely to concentrate in an area. eration economies (Fu, 2007; Rosenthal and

Lovely et al. (2005) investigated whether the Strange, 2008) attenuate rapidly with distance.

need to acquire information contributes to Although these studies did not explicitly pre-

spatial concentration, while Nakamura (2005) dict the impact of ICT on agglomeration, the

focused on the forward and backward linkage implication is that a decrease in the cost of

externalities.1 communication and transport over distance

Along with the rapid progress and wide will attenuate agglomeration and lead to more

application of information and communica- dispersion.

tion technologies (ICTs) during the past few The second strand of literature predicts

decades, an interesting research question has that ICT will attenuate the demand for face-

been debated: if people can communicate over to-face communications and thus will result

a long distance at decreasing cost via phones, in greater dispersion of economic activities.

fax machines, the Internet and e-mails, is Ota and Fujita (1993) constructed a general

it still necessary for people and firms to be equilibrium model of multiunit firms’ loca-

located close to each other? Or, put in another tion and showed that the development of

way, will the improvement of ICT attenuate, information technology will lead to a greater

or even eliminate the geographical concen- concentration of front-units in the city cen-

tration of economic activities, or even cities? tre and to a dispersion of back-units in the

There is no consensus, either theoretically or far suburbs. Sivitanidou (1997) found that

empirically. between 1989 and 1994 the office-commercial

Theoretically speaking, while ICTs have land value gradients within polycentric Los

led to the de-agglomeration or dispersion Angeles flattened. His interpretation was

of some routine activities, ICTs have also that the recent information revolution had

created a knowledge-based economy result- weakened the attractiveness of large business

ing in more new complex opportunities centres to office-commercial activities, result-

that continue to require face-to-face contact ing in the increasingly dispersed patterns of

(Storper and Venables, 2004). In addition, business locations. Ioannides et al. (2007)

it is argued that information is inevitably developed a formal model showing that the

embedded in social relations since learn- improvement of ICT will increase the disper-

ing (transforming information to people’s sion of economic activities across cities, sug-

knowledge) relies on complex social interac- gesting that city sizes would be more uniform.

tions (Brown and Duguid, 2002). Therefore, They also used cross-country city size data

whether ICT promotes agglomeration or not and found supportive evidence.2

is an empirical question. The third strand, however, has an opposite

Existing empirical studies on the relation- viewpoint. Gaspar and Glaeser (1998) devel-

ship between ICT and the geographical con- oped a theoretical model and demonstrated

centration of industries can be grouped into that ICT and face-to-face interactions could be

roughly three strands. The first strand found complementary, rather than substitute goods.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2341

The reason is that, while some face-to-face out separately, at these three geographical

contacts will be replaced and conducted elec- levels. The empirical results show a positive

tronically, the improved ICT may result in more and strong association between the adoption

face-to-face interactions. If the second force is of ICT and the geographical concentration

dominant, then ICT may strengthen agglomer- of industries. These results are quite robust

ation. They also provided some suggestive evi- to different measures of ICT as well as at

dence, such as the negative correlation between different geographical levels. To deal with

geographical distance and number of phone the concerns on omitted variables and endo-

calls, the complementary relationship between geneity issues, we add two-digit industry

business travel and telecommunications, and dummies and control for government policy

the increase in co-authorship in economics. that might have affected both ICT usage and

Panayides and Kern (2005) extended Gaspar geographical concentration. We also use an

and Glaeser’s model and found that improve- instrumental variable approach based on a

ments in ICT may increase or decrease the predetermined value of ICT. The estimation

demand for face-to-face interactions, depend- results provide further support to the argu-

ing on the cross-price elasticity. If the cross- ment that the adoption of ICT promotes the

elasticity is negative, then city size may increase geographical concentration of industries.

with electronic communications. Kolko (2000) The next section describes the measurement

found that commercial Internet domain density of variables, the econometric model specifica-

(the ratio of commercial Internet domains to tions and identification issues and strategies.

commercial establishments) is higher in larger Section 3 introduces the data and provides

cities, controlling for a broad range of other summary statistics. Section 4 presents the

factors. He interpreted this as evidence that estimation results and section 5 concludes.

face-to-face contact is a complement to elec-

tronic communication.3

2. Variable Definitions and

This study contributes to the literature by

Econometric Model Specification

providing new evidence for unravelling the

dispute between the competing hypotheses This section begins by discussing the mea-

regarding the relationship between ICT and surement of geographical concentration.

the geographical concentration of manufac- The variables that proxy for ICT, and other

turing industries. Specifically, we examine determinants of industrial agglomeration,

the impact of ICT on the spatial concentra- are then defined, followed by the specification

tion of manufacturing industries in China, of econometric models and identification

controlling for other main determinants of strategies.

geographical concentration. The data used in

this research are drawn from the 2004 China 2.1 Measuring Geographical

economic census database, which is believed Concentration

to be the most comprehensive micro-level The two widely used indexes of geographical

database in China thus far. It contains detailed concentration are the Gini coefficient, pro-

information on the entire universe of manu- posed by Krugman (1991), and the Ellison–

facturing firms in China. For each four-digit Glaeser index (Ellison and Glaeser, 1997). The

manufacturing industry, we compute the difficulty with the Gini coefficient is that an

Ellison–Glaeser index (Ellison and Glaeser, industry will be regarded as highly localised if

1997) to measure the level of geographical there are several very large firms concentrat-

concentration at the county, city and province ing in a limited number of locations. The EG

levels. The econometric analyses are carried index, however, can control for differences

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2342 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

in firm size. This paper uses the EG index, own websites where relevant information is

calculated according to the following formula posted, including descriptions of companies

and products, company and industrial news,

G − (1 − ∑ mi2 )H career information and after-sale services.

γ=

i (1) Some company sites also support business

(1 − ∑ mi )(1 − H )

2

transactions and electronic commerce. With

i

the popularity of the Internet, a company’s

where, γ is the EG index (also called the website has become increasingly important.

Gamma index), for a particular industry; One can expect that the companies that have

G = ∑ i (si − mi )2; and s is the ratio of location

i their own website may have more advanced

i’s employment in a particular industry to the information technology. Thus, we use share of

national employment in that industry; mi is companies that have a website in an industry,

the ratio of location i’s total employment to as a proxy of ICT.

the national employment; and H = ∑ j z j

2

E-mails and fax machines have also been

denotes the (employment) Herfindahl index widely used in business and generate new

of the J plants in the industry, with z j repre- options for communication. Some rela-

senting the employment share of the jth plant. tionships that previously would have been

The Gamma index has been widely conducted face-to-face have been replaced

employed in recent studies on industrial by telecommunications. For instance, a com-

agglomeration (for example, Lovely et al., pany manager now can send an e-mail to the

2005; Rosenthal and Strange, 2001). Values clients instead of meeting them in person.

of the Gamma index usually range between Business partners can fax or e-mail draft

-1 and 1. γ takes on a value of zero when contracts to each other instead of delivering

an industry is as concentrated as one would them by hand. However, as noted by Gaspar

expect if the plants in the industry choose and Glaeser (1998), there is an opposing

locations by throwing darts at a map. A posi- effect when telecommunication improves:

tive value of γ indicates excess concentration, advanced ICT makes communication easier

while a negative value of γ implies an excess and hence increases the number of relation-

diffusion of employment. ships. For example, with improved ICT, a

company manager can contact more clients

2.2 Measuring Information and and run more projects, which implies that the

Communication Technologies manager needs more face-to-face contacts.

Geographical distance is a hindrance to face- Since the requirement of face-to-face contacts

to-face contacts and the communication of contributes to agglomeration, the net effect of

ideas. With the improvement of ICT, some telecommunication improvement on indus-

face-to-face contacts are replaced electroni- trial agglomeration is unknown. Therefore,

cally and the costs of communicating ideas we use the share of firms that have a fax number

over distance are reduced, implying that or an e-mail address in an industry, as a proxy

advanced ICT may affect agglomeration for ICT. Since firms that have more computers

forces. The focus of this paper is to test the per worker are believed to have better ICT,

impact of ICT on industrial agglomeration. we also try share of firms with above-average

The rapid development of ICT has been computer share, as an additional proxy.5

characterised by the ever-increasing use of

phones, fax machines, personal comput- 2.3 Controls for Other Variables

ers, the Internet and e-mails, over the past Our model includes a set of control variables

few decades.4 Many companies have their that may affect industrial agglomeration. The

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2343

first set of control variables concern labour officials and help to maintain social stability

market pooling. We use share of workers with and serve other social purposes (Bai et al., 2004;

a master’s or college degree6 in an industry Lu and Tao, 2009). Therefore, share of employ-

respectively, as proxies for labour pooling. ment in state-owned enterprises in an industry

We also define average labour intensity in an is used to measure local protectionism.

industry as proportion of number of employ- Our model also considers the impact of

ees over total asset to examine the impact of firm age. Rosenthal and Strange (2001) found

labour markets. The basic idea is that the that, compared with the agglomeration of all

need for human capital and labour intensity establishments, agglomeration of new estab-

may have an impact on a firm’s motivation lishments is not as strongly related to agglom-

to concentrate. erative spillovers and natural advantages. We

The second set of variables controls for include share of young firms in an industry in

natural advantages and knowledge spillovers. the model, where young firms are defined as

Industries concentrate partially due to natural those that are five years old or younger.

advantages, as discussed in Ellison and Glaeser

(1999). We use share of firms in the industry 2.4 Econometric Model Specification

that are located in coastal provinces as a proxy and Identification

for natural advantage, because coastal regions We are interested in how the Gamma index is

in China tend to have flatter terrain, a bet- affected by ICT, controlling for other determi-

ter climate and easier access to seaports and nants of industrial agglomeration, as defined

international markets. Knowledge spillover earlier. The econometric model is specified

is also an important factor in determining as follows

industrial concentration. Because knowledge γ ij = δ X j + eij

(2)

spillover is found to be more significant in

R&D intensive industries, industries that are where, γ ij is the Gamma index for industry j

highly innovative are expected to have higher (four-digit code) at geographical level i; X j is

levels of agglomeration (Lovely et al., 2005). a vector of industry characteristics, including

Similar to previous studies (for example, variables that proxy for ICT, labour pooling,

Lovely et al., 2005), we use number of innova- knowledge spillovers and natural advantages;

tions per worker in an industry, as a proxy for δ is the coefficient vector to be estimated; and

knowledge spillover.7 eij is the error term, assumed to be indepen-

Previous studies have shown that local dently and identically distributed.

protectionism is an important and special The benchmark model is estimated at the

determinant of geographical concentra- county level. To test the robustness of our

tion in China (Bai et al., 2004; Lu and Tao, specification, we also estimate the model at

2009). Local governments have motivation the city and province levels. In China, a city

to protect local firms and industries due to is larger than a county, in terms of land area.

fiscal decentralisation after China’s economic A city normally contains a number of coun-

reform. There was a rise of local protection- ties. There are 31 provinces, 345 cities and

ism in China during the reform era (Young, 2831 counties in mainland China.

2000), creating barriers to trade and imped- The key identification assumption is that,

ing the process of industrial agglomeration. after including the control variables in the

Local governments give more protection to model, the ICT variables are uncorrelated

industries with higher shares of state owner- with the error term. This assumption may

ship, because state-owned enterprises can cre- be violated if there are important omitted

ate much more benefit for local government variables or if firms in highly concentrated

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2344 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

industries have a stronger preference to between ICT adoption in an industry and

adopt ICT, generating omitted variable bias geographical concentration. However, the

and an endogeneity problem. To address the causality direction can run both ways.10 It is

omitted variable bias problem, we add to possible that ICT causes more concentration

the benchmark model two sets of variables by facilitating more face-to-face interactions

that may affect ICT adoption as well as geo- or through other channels; it is also possible

graphical concentration. Since unobservable that concentration causes firms to adopt more

industrial characteristics may affect both ICT because of the harsh competition among

ICT and geographical concentration, we firms in the same geographical cluster. To deal

add 29 two-digit industry dummies to the with the causality problem, we use instrumen-

model. Another important omitted variable tal variable estimation. A valid instrument

that we can think of is government policy. should be correlated with ICT variables, but

In China, government zoning policies have orthogonal to the error term. Following previ-

played an important role in both business ous studies (for example, Henderson, 2003),

location and ICT adoption. Local govern- we use a predetermined value of ICT as an

ments have established high-tech industrial instrument. We use another dataset—the

parks to promote high-tech industrial clus- 2003 State Statistical Bureau enterprises sur-

tering, and some other special zones (such vey dataset, which covers all manufacturing

as export-processing zones and free trade enterprises that are state-owned or are above

zones) to promote export. Within high-tech a designated size.11 The database contains

industrial parks, some preferential policies information on firms’ e-mail addresses, but

(such as tax holidays, preferential account- does not provide information on website,

ing treatment) are implemented to promote fax and computer usage. Therefore, we use

adoption of new technologies like ICT. Within the share of firms in each industry that had

export-processing zones and free trade zones, e-mail addresses in 2003 as an instrument.

export-oriented firms tend to locate close

to each other. Because these firms are more

3. Data and Summary Statistics

exposed to international trading practices

and standards, they are more likely to adopt The data used for this research are drawn

ICT as well.8 Therefore, the government from the first economic census in China,

zoning policies could have driven up both conducted by the Chinese government from

geographical concentration and ICT usage. 2004 to 2005. It is believed to be the most

To deal with this concern, two proxy variables comprehensive micro-level database on

are added to the model. The first is a dummy Chinese industries thus far. We obtained

for high-tech industries, used to capture the the manufacturing industry data from the

effect of government policy towards high-tech State Statistical Bureau of China. The dataset

industries. The classification of high-tech contains detailed information on all manufac-

industries is based on the standard used by turing firms (over 1.3 million) at the end of

the State Statistical Bureau of China. There 2004, including firm location, year of entry,

are 59 high-tech manufacturing industries at ownership, employees and the like.

the four-digit level. The second variable is to Two characteristics of this database make

measure the export orientation of an industry, it distinct from those used in previous stud-

which equals one if an industry has an above- ies. First, the dataset contains information

average export share and zero otherwise.9 on the entire universe of manufacturing

The estimation results based on equation firms in China, while many recent studies

(2) provide evidence on the correlation (for example, Lovely et al., 2005; Maurel and

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2345

Sedillot, 1999; Rosenthal and Strange, 2001) be very high, but the EG index at the county

used only a proportion of manufacturing level may not be so high. These results are

firms in a country.12 Secondly, all data used also consistent with those of previous studies

in this research are from the same census (for example, Rosenthal and Strange, 2001),

database, therefore the consistency of data suggesting that spillovers go beyond a small

is guaranteed. However, the census database area (Ellison and Glaeser, 1997).

available for research is only at the firm level Table 2 indicates that there are large varia-

and not at the establishment or plant level. tions in spatial concentration across two-

One concern is that, if a firm has several plants digit industries. At the county level, the most

located in different places, and all employees localised industries are cultural, educational

are assigned to the headquarter, a measure- and sports goods, and smelting and pressing

ment error arises when we calculate industrial of non-ferrous metals. At the city and prov-

agglomeration. Fortunately, only a very small ince levels, the most concentrated industries

proportion (about 1.778 per cent) of firms are smelting and pressing of non-ferrous met-

have multiple plants. In addition, according als, and electronics and telecommunication.

to the rule of the State Statistical Bureau of We note that some high-tech industries are

China, all employees of a multiplant firm are highly concentrated (for example, electronics

allocated to the address where the main pro- and telecommunication), while other high-

duction takes place. Thus, we believe that this tech industries are much less concentrated

issue does not lead to serious bias, especially, (for example, medical and pharmaceutical

at the higher geographical levels. products). The pattern of traditional indus-

The data cover 482 four-digit manufac- tries is also mixed. For instance, cultural, edu-

turing industries. Based on the firm-level cational and sports goods are very localised,

data, we calculate the Gamma index at the while the tobacco processing industry is quite

county, city and province levels, for each dispersed.

four-digit industry. Table 1 shows that there An industry is as concentrated as a ran-

is substantially more concentration at the dom allocation when the EG index equals

higher geographical levels: the mean value zero and is excessively concentrated when

of the Gamma index at the province level the index is positive. Using manufacturing

is 0.0657, while at the county level it is only census data for the US, Ellison and Glaeser

0.0155. These results are as expected, since (1997) defined not very localised (state level

provinces are larger than cities and counties. 0 < γ < 0.02), intermediate, and very localised

If employment in an industry is spread over a (state level γ > 0.05) ranges. When we apply

number of counties within one province, the the same classification criteria of Ellison and

Gamma index at the provincial level would Glaeser (1997) to Chinese manufacturing

Table 1. Summary of the EG Gamma index at the four-digit industry level

Correlation with γ at

the level of

γ Mean SD Minimum Maximum City Province

County 0.0155 0.0231 –0.0188 0.1931 0.8482 0.6531

City 0.0287 0.0370 –0.0186 0.2919 0.7373

Province 0.0657 0.0718 –0.0812 0.5195

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2346 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

Table 2. Mean value of the Gamma index in two-digit industries

Industry code and name County γ City γ Province γ

13 Food production 0.0118 0.0261 0.0829

14 Food manufacturing 0.0089 0.0176 0.0473

15 Beverage production 0.0052 0.0167 0.0465

16 Tobacco processing 0.0030 0.0034 0.0663

17 Textile industry 0.0219 0.0330 0.0703

18 Garments and other fibre products 0.0112 0.0173 0.0334

19 Leather, furs, down and related products 0.0264 0.0471 0.0866

20 Timber processing, bamboo products 0.0136 0.0260 0.0519

21 Furniture manufacturing 0.0153 0.0195 0.0640

22 Paper making and paper products 0.0111 0.0142 0.0319

23 Printing and medium reproduction 0.0053 0.0126 0.0250

24 Cultural, educational and sports goods 0.0375 0.0506 0.0947

25 Petroleum refining and coking 0.0049 0.0087 0.0665

26 Raw chemical materials and chemical products 0.0098 0.0182 0.0493

27 Medical and pharmaceutical products 0.0037 0.0099 0.0270

28 Chemical products 0.0083 0.0124 0.0296

29 Rubber products 0.0063 0.0123 0.0281

30 Plastic products 0.0176 0.0257 0.0646

31 Non-metal mineral products 0.0207 0.0323 0.0593

32 Smelting and pressing of ferrous metals 0.0045 0.0189 0.0814

33 Smelting and pressing of non-ferrous metals 0.0317 0.0583 0.1516

34 Metal products 0.0161 0.0283 0.0479

35 Ordinary machinery 0.0091 0.0170 0.0436

36 Special-purpose equipment 0.0098 0.0209 0.0528

37 Transport equipment 0.0154 0.0445 0.0726

39 Electrical machinery and equipment 0.0182 0.0266 0.0768

40 Electronics and telecommunication 0.0206 0.0538 0.1119

41 Instruments and meters 0.0156 0.0308 0.0721

42 Artwork and others 0.0269 0.0460 0.0988

43 Recycling and disposal of waste 0.0109 0.0119 0.0138

Table 3. Distribution of the Gamma index at the four-digit industry level

Number of four-digit industries

Gamma γ at the county level γ at the city level γ at the province level

γ≤0 286 144 45

0 < γ ≤ 0.02 135 197 107

0.02 < γ ≤ 0.05 44 92 147

0.05 < γ ≤ 0.10 9 33 113

0.10 < γ ≤ 0.20 8 9 47

γ > 0.20 0 7 23

industries, 107 out of 482 four-digit industries Compared with the spatial concentration

are not very localised at the province level, of US manufacturing industries (for example,

while 183 of them are very localised, as shown Rosenthal and Strange, 2001), Chinese indus-

in Table 3. tries are more concentrated on average. For

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2347

example, the average EG index equals 0.0657 websites, e-mail addresses and fax numbers

at the province level in China, while that for are, on average, 6.58 per cent, 8.16 per cent

the US is 0.0485 at the state level (Rosenthal and 42.04 per cent respectively. There are 33.4

and Strange, 2001). However, we need to be per cent of firms with a computer share above

cautious when making such comparisons, the average level. The correlation coefficients

since the Chinese provinces are normally among these ICT-related variables are quite

larger than American states in terms of land high. To avoid multicollinearity, we will not

area. In addition, the official classification of include them in the same equation.

industries is different. Table 4 also reports descriptive statistics for

Table 4 reports descriptive statistics of other control variables. The variable of num-

the explanatory variables. In the census, all ber of innovations per worker is at the three-

firms were required to report their websites, digit industry level and is drawn from the

fax numbers, e-mail addresses and number China Economic Census Yearbook 2004 (State

of computers, if any. There was an auditor, Statistical Bureau, 2006). All other variables

who has been trained formally by the State are computed directly from the census data-

Statistical Bureau, to recheck the data and base and are at the four-digit industry level.

information reported after a firm filled in

the census form, which guarantees the qual- 4. Estimation Results

ity of the database. The value takes one if a

firm has a website, fax or e-mail, and zero 4.1 Benchmark model results

otherwise, based on which we compute ICT- Table 5 presents the estimation results for

related variables at the four-digit industry the benchmark model, with the EG index

level. The shares of firms that have their own at the county level as the explained variable.

Table 4. Descriptive statistics of explanatory variables

Variable Definition Mean S.D.

Master’s degree Share of workers with master’s degree 0.0044 0.0094

College degree Share of workers with college degree 0.0910 0.0443

Average labour intensity Number of employees/total asset 0.0385 0.1038

Innovations per worker Number of innovations per worker in an industry 0.0006 0.0006

Natural advantage Share of firms in the industry that are located in 0.6973 0.1691

coastal provinces

Local protectionism Share of employment in state-owned enterprises 0.1025 0.1472

in an industry

Young firms Share of young firms (5 years old or younger) 0.5166 0.0800

Website Share of firms that have website 0.0658 0.05197

Fax Share of firms that have fax 0.4204 0.1534

E-mail Share of firms that have e-mail 0.0816 0.0580

Computer Share of firms with above-average computer 0.3340 0.0982

share

High-tech dummy A dummy variable, which equals to 1 for 0.1224 0.3281

high-tech industries, and 0 otherwise

Export orientation The ratio of export sales over total sales 0.3838 0.4868

Notes: The variable of innovations per worker is at the three-digit industry level, drawn from the

China Economic Census Yearbook (State Statistical Bureau, 2006). All other variables are at the four-

digit industry level, computed by the authors, based on the census database.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2348 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

Huber–White’s robust standard error is used effect on the geographical concentration of

to control for heterogeneity. The adjusted Chinese industries at the county level.

R2 ranges from 0.097 to 0.113. The labour Table 5 consistently shows that coefficient

market pooling effect is represented by three estimates for local protectionism are posi-

variables: share of workers with master’s degree, tive and insignificant. This is in contrast to

share of workers with college degree, and aver- the findings of Bai et al. (2004), who found

age labour intensity. The results in Table 5 that stronger local government protection

consistently show that share of workers with decreases the degree of geographical concen-

college degree has negative and significant tration during the period of 1985–97. One

impact. The coefficient estimates range from possible interpretation is that our sample

–0.159 to –0.191. The variable share of workers includes all manufacturing firms, but Bai

with master’s degree is negative and significant et al. (2004) considered only firms that are

in one out of the four models. These results above designated size and state-owned.

show that labour quality, in terms of educa- Another possible interpretation is the differ-

tion, is negatively associated with geographi- ent periods studied. Lu and Tao (2009) found

cal concentration of manufacturers. These that the impacts of local protectionism may

results are consistent with some of the previous have become weaker over time. The variable

studies (for example, Shaver and Flyer, 2000; share of young firms, the percentage of firms

Hong, 2009), which find that firms with that are five years old or younger, in an indus-

better human capital are less likely to locate try, is worth noting. The coefficient is positive

close to other firms in an industry. One pos- and significant in most models, suggesting

sible reason is that such firms gain little from that industries with more young firms are

access to competitors’ human capital, while associated with a higher degree of geographi-

firms with weaker human capital greatly cal concentration. Since young firms are easily

benefit from proximity to competitors. This exposed to ICT, this may suggest that ICTs

asymmetry in returns to agglomeration may have not weakened the incentives of new firms

motivate firms with better human capital to concentrate.

not to cluster geographically (Shaver and The key interest of this paper is to inves-

Flyer, 2000). The coefficient of average labour tigate the impact of ICT on geographical

intensity is positive and significant in two of concentration. Four variables are used to

the four models. Taken together, these results measure the adoption of ICT in an industry:

provide supportive evidence that labour share of firms that have websites, share of firms

market pooling has a significant effect on that have fax numbers, share of firms that have

industrial agglomeration. e-mail addresses and share of firms with above-

We also examine the impact of natural average computer share. Table 5 indicates that

advantages and knowledge spillovers. Share of the coefficients for website, fax, e-mail and

firms in the industry that are located in coastal computer share are 0.088, 0.037, 0.095 and

provinces is used as a proxy for natural advan- 0.031 respectively. All coefficient estimates are

tages and its impact is insignificant, consistent significant at the 5 per cent level. Contrary to

with Rosenthal and Strange (2001). The the argument that ICT leads to more disper-

impact of number of innovations per worker, sion, these results provide strong evidence

a proxy for knowledge spillovers, is positive that the adoption of ICT is associated with a

and marginally significant in two of the four higher degree of geographical concentration

models. These results suggest that natural of manufacturers. This evidence is consistent

advantage has an insignificant impact, while with the view that improved ICT may result

knowledge spillover has a moderate and positive in more face-to-face relationships (Gaspar

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2349

Table 5. Benchmark model: regression results at the county level (N = 482)

Variables (1) (2) (3) (4)

Master’s degree -0.129 -0.092 -0.163* -0.094

(-1.46) (-1.35) (-1.80) (-1.48)

College degree -0.181*** -0.191*** -0.185*** -0.159***

(-4.31) (-5.12) (-4.50) (-4.81)

Average labour intensity 0.008** 0.006 0.008** 0.006

(2.20) (1.42) (2.32) (1.38)

Innovations per worker 4.270* 4.056 3.961 5.016*

(1.72) (1.46) (1.58) (1.80)

Natural advantage 0.003 -0.009 -0.001 0.004

(0.33) (-0.78) (-0.11) (0.49)

Local protectionism 0.024 0.016 0.023 0.029

(1.03) (0.72) (1.03) (1.42)

Young firms 0.034** 0.032* 0.034** 0.034**

(2.17) (1.95) (2.11) (2.01)

Website 0.088**

(2.52)

Fax 0.037***

(3.53)

E-mail 0.095***

(3.55)

Computer 0.031***

(2.83)

Adjusted R2 0.105 0.109 0.113 0.097

Notes: Dependent variable is g at the county level. Constants are not reported in order to conserve

space. T-values are given in parentheses. Huber–White’s robust standard error is used to control

for heterogeneity. *, ** and *** denote significance at the 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent level

respectively.

and Glaeser, 1998; Panayides and Kern, levels. One interesting finding is that the

2005), which motivates firms to agglomerate magnitude of all four ICT variables increases

geographically. at higher geographical levels. For instance,

the coefficient for website is 0.088 at the

4.2 Robustness Tests county level; it increases to 0.113 at the city

In the benchmark model, we regress the level and to 0.280 at the province level. We

Gamma index on possible determinants also note that model fitness is improved sig-

at the county level. Readers might wonder nificantly at higher geographical levels. This

whether our results are sensitive to different pattern is consistent with that in Rosenthal

levels of geography. To address this concern, and Strange (2001).

we estimate the model at the city and prov- Another concern is that our results may be

ince levels. The results are reported in Table 6, subject to outlier bias. Compared with other

where each estimate is taken from a separate industries, the electronics and telecommu-

regression. It shows that all ICT variables are nication industry has a significantly higher

significant at both the city and the province Gamma index, as well as ICT adoption.

levels. This provides supportive evidence that A natural concern is that the estimation

our results are robust at different geographical results may be biased by the inclusion of

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2350 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

Table 6. Robustness test: regression results Table 7. Estimation results: inclusion of

at the city and province levels two-digit industry dummies and policy effects

Variables City level γ Province level γ County City Province

level γ level γ level γ

Website 0.113* 0.280***

(1.94) (2.74) Website 0.062 0.033 0.011

Fax 0.067*** 0.210*** (1.26) (0.39) (0.08)

(3.94) (4.45) Fax 0.019* 0.038** 0.132***

E-mail 0.147*** 0.427*** (1.68) (1.98) (2.95)

(3.54) (4.54) E-mail 0.071* 0.078 0.229*

Computer 0.054*** 0.148*** (1.71) (1.13) (1.84)

(2.69) (3.11) Computer 0.009 0.017 0.036

(0.64) (0.72) (0.65)

Notes: Each estimate is taken from a separate

regression. All other variables in Table 5 are Notes: Each estimate is taken from a separate

included, but the coefficients are not reported regression with 29 two-digit industry dummies

here. T-values are given in parentheses. Huber– and policy effects (high-tech dummy and

White’s robust standard error is used to control export orientation) included. High-tech

for heterogeneity. *, ** and *** denotes the industries are at the four-digit level and cross

significance at the 10 per cent, 5 per cent and 1 nine two-digit industries. The coefficient

per cent level respectively. estimates for the high-tech dummy range

between -0.009 and 0.013, and are insignificant

in all regressions. The estimated coefficients

this outlier industry. We experiment to drop

of export orientation range between 0.006

this industry and re-run the regressions. The and 0.029, and are significant at the 1 per cent

results show that dropping the electronics and level in all regressions. All other variables in

telecommunication industry does not change Table 5 are included, but the coefficients are

the coefficient estimates substantially.13 Most not reported here. T-values are given in the

ICT variables are still significantly and posi- parentheses. Huber–White’s robust standard

tively associated with geographical concen- error is used to control for heterogeneity.

tration. This provides an additional piece of *, ** and *** denote the significance at the 10 per

evidence that our regression results are robust. cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent level respectively.

4.3 Endogeneity Issues other control variables are quite consistent

To deal with possible endogeneity issues, we with those in Table 5, in terms of both signifi-

try two experiments. The first experiment cance and magnitude (to save space, the results

concerns possible omitted variable bias. We for other variables are not reported here).

add to the benchmark model two sets of The other experiment involves instrumen-

variables that may affect ICT adoption as well tation. A valid instrument should be cor-

as geographical concentration, including 29 related with ICT variables but orthogonal

two-digit industry dummies and two proxies to the error term. We use the share of state-

for government policies (a high-tech dummy owned or above-designated-size firms in an

and the export-orientation of an industry). industry that had e-mail addresses in 2003

The results are reported in Table 7. The results as an instrument (lagged e-mail thereafter).

are still robust: all coefficient estimates for The correlation coefficients between ICT

ICT variables are positive. The variable fax variables and lagged e-mail range from 0.408

is significant at all three geographical levels, to 0.606 (column 1 of Table 8). We regress

while e-mail is significant at both county and each ICT variable on lagged e-mail, and find

province levels. The coefficient estimates of that all coefficients are positive and significant

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2351

Table 8. Correlation between ICT variables instrument. With regard to the exclusion

and the instrumental variable restriction (i.e. the instrumental variable does

not affect geographical concentration through

Correlation

between ICT with channels other than the ICT variables), we

instrumental believe that the causality of lagged e-mail is

variablea Coefficientb irreversible: new firm location can respond

to past industry ICT adoption, but not vice

Website 0.557 0.507*** versa. We do a test related to the exclusion

(5.58)

Fax 0.536 1.388*** restriction by regressing the residuals from

(6.39) the second-stage estimations on the instru-

E-mail 0.606 0.593*** mental variable. If the instrumental variable

(6.42) affects the industrial agglomeration through

Computer 0.408 0.678***

(5.19) other channels, the residuals from the second-

stage estimations should be correlated with

a

The instrumental variable is the share of the instrumental variable (Lu and Tao, 2009).

state-owned or above-designated-size firms that

The regression results consistently show that the

have e-mail in an industry in 2003.

b

Coefficient is on the instrumental variable correlation between the two is close to zero in

(lagged e-mail) in a regression of ICT variables magnitude and is statistically insignificant.14

(website, fax, e-mail, computer respectively) on In summary, these tests show that lagged

lagged e-mail. e-mail is a good instrument.

Note: *** indicates the significance at the Table 9 shows that all ICT coefficient esti-

1 per cent level. mates are positive and significant, although

the coefficient estimates lose some signifi-

at the 1 per cent level (column 2 of Table 8), cance compared with the benchmark models.

which indicates the instrument strength. The As in previous studies (for example, Alfaro

IV regression results are reported in Table 9. et al., 2004), the coefficients increase consid-

F-values greater than 10 in the first-stage erably in values compared with the earlier

regressions confirm again the validity of the OLS results in Tables 5 and 6. One possible

Table 9. IV estimation results

First-stage partial

County level γ City level γ Province level γ R2 and F-value

Website 0.381* 0.649** 0.809** [0.167, 14.749]

(1.77) (2.09) (2.29)

Fax 0.126* 0.215** 0.267** [0.147, 22.518]

(1.87) (2.29) (2.54)

E-mail 0.301** 0.513** 0.640** [0.207, 22.150]

(1.97) (2.32) (2.54)

Computer 0.300* 0.510** 0.636** [0.059, 13.083]

(1.83) (2.07) (2.22)

Notes: Each estimate is taken from a separate regression. All control variables in Table 5 are included

in the model. The ICT variables are instrumented by the share of state-owned or above-designated-

size firms that have e-mail in an industry in 2003. T-values are shown in parentheses. Huber–White’s

robust standard error is used to control for heterogeneity. *, ** and *** denotes significance at the 10

per cent, 5 per cent and 1 per cent levels respectively. Partial R2 and F-value based on the first-stage

regression are shown in brackets.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2352 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

interpretation is that instrumental variable exact mechanisms through which ICT affects

estimation here corrects for measurement industrial agglomeration are left for future

error, which biases the OLS coefficients to research agenda.

zero. Taken together, the results in this sec-

tion lend additional support to the view that

modern information and communication Notes

technologies have resulted in a higher degree 1. For more related studies, see the literature

of industrial agglomeration. review by Duranton and Puga (2004) and

Rosenthal and Strange (2004).

2. There are a few futurists predicting the

5. Conclusions disappearance of cities, see Toffler (1980) and

It has long been speculated that adoption of Naisbitt (1995).

ICT may decrease industrial agglomeration 3. Using individual on-line and off-line

shopping behaviour data, Sinai and Waldfogel

because developments in telecommunications

(2004) found that the Internet can be both

have generated new options for communica- a complement to cities and a substitute for

tions and have replaced face-to-face contacts. cities.

Some people even predict that industrial 4. We do not test the impact of phone lines,

clusters will decline or disappear because because almost all firms use telephones.

firms have no need to locate close to each 5. We do not use average computer share of an

other with improvements in telecommuni- industry as a proxy, because a small proportion

cations technologies. However, others argue of companies have a very large number of

that face-to-face communication and tele- computers. We use share of firms with above-

communication can be complements, since average computer share to avoid outlier bias.

6. The variable share of workers with bachelor’s

face-to-face contact is necessary for learning

degree is not included, since it is highly

and creative activities, and adoption of ICT correlated with other variables. In China,

can increase the number of business relation- college-degree holders normally receive a

ships. Our research examines the impact of three-year education, while bachelor-degree

advanced information and communication holders require a four-year education.

technologies on the geographical concentra- 7. Following Rosenthal and Strange (2001), we

tion of manufacturing industries in China. have also tried to use energy consumption per

We use the 2004 China economic census worker and technological funds per worker

data and compute the Ellison–Glaeser index to measure natural advantage and knowledge

to measure the geographical concentration spillover respectively, and find quite consistent

estimation results.

of four-digit industries. After controlling for

8. Lovely et al. (2005) found that exporter

the main industrial characteristics that may headquarters are more agglomerated when

influence geographical concentration, such foreign market information is difficult to

as labour pooling and natural advantage, we obtain.

find that adoption of ICT actually increases 9. We do not use average export share of an

geographical concentration. These results industry as a proxy, because a small proportion

are quite robust to various measures of ICT, of companies have a very high export share.

at different geographical levels, the inclusion In order to avoid outlier bias, we use share of

of other determinants of agglomeration and firms with above-average export share instead.

10. The causality direction between some

consideration of endogeneity. Our findings

industrial characteristics (such as labour

suggest that knowledge spillovers through quality) and agglomeration can run both

face-to-face contact might still be important ways. For these variables, the coefficients may

for manufacturing industries. However, the reflect the equilibrium relationship rather than

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

ICT AND MANUFACTURING IN CHINA 2353

causal effects. Since our focus is the impact of Vol. IV, pp. 2063–2117. Amsterdam: Elsevier

ICT, we will conduct causality analysis only North-Holland.

on ICT effects. Ellison, G. and Glaeser, E. (1997) Geographic

11. Firms that are above designated size are defined concentration in U.S. manufacturing indus-

as those with annual sales of over 5 million tries: a dartboard approach, Journal of Political

Chinese yuan. We did not use predetermined Economy, 105, pp. 879–927.

values of ICT in earlier years as instruments, Ellison, G. and Glaeser, E. (1999) The geographic

because the industry category and code by concentration of an industry: does natural

State Statistical Bureau changed significantly advantage explain agglomeration?, American

in 2003. Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, 89,

12. An exception is a recent paper by Lu (2010) pp. 311–316.

that used the first and second Chinese national Fu, S. (2007) Smart café cities: testing human

establishment censuses in 1996 and 2001, capital externalities in the Boston metropolitan

which cover all manufacturing establishments area, Journal of Urban Economics, 61, pp. 86–111.

in China. Gaspar, J. and Glaeser, E. (1998) Information

13. To save space, the estimation results are not technology and the future of cities, Journal of

reported here, but are available from the Urban Economics, 43, pp. 136–156.

authors upon request. Henderson, J. (2003) Marshall’s scale economies,

14. To save space, the estimation results are not Journal of Urban Economics, 53, pp. 1–28.

reported here, but are available from the Hong, J. (2009) Firm heterogeneity and location

authors upon request. choices: evidence from foreign manufacturing

investments in China, Urban Studies, 46(10),

pp. 2143–2157.

Acknowledgement Ioannides, Y., Overman, H., Rossi-Hansberg, E.

and Schmidheiny, K. (2007) The effect of

Shihe Fu gratefully acknowledges financial support

information and communication technologies

from Project 211 (Phase III) of the Southwestern

on urban structure. Discussion Paper No. 812,

University of Finance and Economics, Chengdu,

Centre for Economic Performance, London

China.

School of Economics.

Jacobs, J. (1961) The Death and Life of Great

References American Cities. New York: Vintage Books.

Jaffe, A. B., Trajtenberg, M. and Henderson, R.

Alfaro, L., Chanda, A., Kalemli-Ozcan, S. and (1993) Geographic localization of knowl-

Sayek, S. (2004) FDI and economic growth: edge spillovers as evidenced by patent cita-

the role of local financial markets, Journal of tions, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108,

International Economics, 64, pp. 89–112. pp. 577–598.

Audretsch, D. B. and Feldman, M. (1996) R&D Kolko, J. (2000) The death of cities? The death

spillovers and the geography of innovation of distance? Evidence from the geography of

and production, American Economic Review, commercial internet usage, in: I. Vogelsang and

86, pp. 630–640. B. Compaine (Eds) The Internet Upheaval: Raising

Bai, C., Du, Y., Tao, Z. and Tong, S. (2004) Local Questions, Seeking Answers in Communications

protectionism and regional specialization: Policy, pp. 73–97. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

evidence from China’s industries, Journal of Krugman, P. (1991) Geography and Trade.

International Economics, 63, pp. 397–417. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Brown, J. S. and Duguid, P. (2002) The Social Lovely, M., Rosenthal, S. and Sharma, S. (2005)

Life of Information. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Information, agglomeration, and the head-

Business School Press. quarters of U.S. exporters, Regional Science and

D u r a n t o n , G . a n d P u g a , D. ( 2 0 0 4 ) Urban Economics, 35, pp. 167–191.

Microfoundations of urban agglomeration Lu, J. (2010) Agglomeration of economic activi-

economies, in: V. Henderson and J. Thisse (Eds) ties in China: evidence from establishment

Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, censuses, Regional Studies, 44(3), pp. 281–297.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

2354 JUNJIE HONG AND SHIHE FU

Lu, J. and Tao, Z. (2009) Trends and determinants Rosenthal, S. and Strange, W. (2004) Evidence on the

of China’s industrial agglomeration, Journal of nature and sources of agglomeration economies,

Urban Economics, 65(2), pp. 167–180. in: V. Henderson and J. Thisse (Eds) Handbook

Marshall, A. (1920) Principles of Economics. of Regional and Urban Economics, Vol. IV,

London: Macmillan. pp. 2119–2171. Amsterdam: Elsevier North-

Maurel, F. and Sedillot, B. (1999) A measure of the Holland.

geographic concentration in French manufac- Rosenthal, S. and Strange, W. (2008) The attenu-

turing industries, Regional Science and Urban ation of human capital spillovers, Journal of

Economics, 29, pp. 575–604. Urban Economics, 64(2), pp. 373–389.

Naisbitt, J. (1995) The Global Paradox. New York: Shaver, J. and Flyer, E. (2000) Agglomeration

Avon Books. economies, firm heterogeneity, and foreign

Nakamura, R. (2005) Agglomeration economies direct investment in the United States, Strategic

and linkage externalities in urban manufacturing Management Journal, 21, pp. 1175–1193.

industries: a case study of Japanese cities. Paper Sinai, T. and Waldfogel, J. (2004) Geography

presented at the 45th Congress of the European and the Internet: is the Internet a substitute

Regional Science Association, Amsterdam, or a complement for cities?, Journal of Urban

August. Economics, 56, pp. 1–24.

Ota, M. and Fujita, M. (1993) Communication Sivitanidou, R. (1997) Are center access advantages

technologies and spatial organization of multi- weakening? The case of office-commercial mar-

unit plants in metropolitan areas, Regional kets, Journal of Urban Economics, 42, pp. 79–97.

Science and Urban Economics, 23, pp. 695–729. State Statistical Bureau (2006) China Economic Census

Panayides, A. and Kern, C. (2005) Information Yearbook 2004. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

technology and the future of cities: an alterna- Storper, M. and Venables, A. J. (2004) Buzz: face-

tive analysis, Urban Studies, 42, pp. 263–267. to-face contact and the urban economy, Journal

Rosenthal, S. and Strange, W. (2001) The deter- of Economic Geography, 4, pp. 351–370.

minants of agglomeration, Journal of Urban Toffler, A. (1980) The Third Wave. New York:

Economics, 50, pp. 191–229. Bantam Books.

Rosenthal, S. and Strange, W. (2003) Geography, Young, A. (2000) The razor’s edge: distortions and

industrial organization, and agglomera- incremental reform in the People’s Republic of

tion, Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, China, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4),

pp. 377–393. pp. 1091–1135.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on April 4, 2015

You might also like

- Teachers Book - Smarty 4 PDFDocument77 pagesTeachers Book - Smarty 4 PDFFlorenciaRivichini50% (2)

- Captiva 2013 Systema Electric 3.0Document13 pagesCaptiva 2013 Systema Electric 3.0carlos martinez50% (2)

- The Practice of Medicinal Chemistry, 4th EditionDocument2 pagesThe Practice of Medicinal Chemistry, 4th Editionlibrary25400% (1)

- How Might The Interconnectedness of Knowledge Spaces and Technological Relatedness Promote Regional Diversity?Document9 pagesHow Might The Interconnectedness of Knowledge Spaces and Technological Relatedness Promote Regional Diversity?Ijbmm JournalNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of The Xingwang Industrial Park in Be (PDFDrive)Document18 pagesA Case Study of The Xingwang Industrial Park in Be (PDFDrive)jonathanNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 91.93.237.116 On Tue, 25 Oct 2022 08:23:22 UTCDocument42 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 91.93.237.116 On Tue, 25 Oct 2022 08:23:22 UTCLatify NazirNo ratings yet

- 10.1177_0042098018820241Document19 pages10.1177_0042098018820241amirhayat15No ratings yet

- Geography, Inequality, and the Impact of New TechnologiesDocument35 pagesGeography, Inequality, and the Impact of New TechnologiesPedro Jose Jimenez DiazNo ratings yet

- Britton2003 Electronics in TorontoDocument24 pagesBritton2003 Electronics in Torontoa.bogodukhov.98No ratings yet

- Digital Entrepreneurship Indicator (DEI) : An Analysis of The Case of The Greater Paris Metropolitan AreaDocument28 pagesDigital Entrepreneurship Indicator (DEI) : An Analysis of The Case of The Greater Paris Metropolitan AreaEriicpratamaNo ratings yet

- Fallah Et Al (2010)Document23 pagesFallah Et Al (2010)212011414No ratings yet

- Van Oort & Bosma Aglomeration Economies, Inventor and EntrepreneursDocument33 pagesVan Oort & Bosma Aglomeration Economies, Inventor and EntrepreneursLautaroNo ratings yet

- Aray - 2019 - A New Approach To Test The Effects of Decentralization On Public Infraestructure InvestmentDocument17 pagesAray - 2019 - A New Approach To Test The Effects of Decentralization On Public Infraestructure InvestmentBrandi ReynoldsNo ratings yet

- Christoper Hoggins - ICT Driven Projects For Land Governance in Kenya Disruption and E-Government FrameworksDocument21 pagesChristoper Hoggins - ICT Driven Projects For Land Governance in Kenya Disruption and E-Government FrameworksCyrillus Fishio FNo ratings yet

- GVC 1103Document18 pagesGVC 1103Shubham JadhwansiNo ratings yet

- Convergence in Information and Communication TechnDocument12 pagesConvergence in Information and Communication Technpatricia roseNo ratings yet

- Impact of ICT on Organizational CompetitivenessDocument7 pagesImpact of ICT on Organizational CompetitivenessimzeeroNo ratings yet

- Exploring Smartness in Public Sector Innovation - Creating Smart Public Services With The Internet of ThingsDocument20 pagesExploring Smartness in Public Sector Innovation - Creating Smart Public Services With The Internet of ThingsDaniela Gabriela CazanNo ratings yet

- E GIS A D T I C D C: T C E: Devries@itc - NLDocument16 pagesE GIS A D T I C D C: T C E: Devries@itc - NLClaudiaMCamposNo ratings yet

- Are Machines Stealing Our Jobs?: Andrea Gentili, Fabiano Compagnucci, Mauro Gallegati and Enzo ValentiniDocument21 pagesAre Machines Stealing Our Jobs?: Andrea Gentili, Fabiano Compagnucci, Mauro Gallegati and Enzo ValentiniShahid AhmedNo ratings yet

- Biblio Metric Tool To Assess ThereDocument21 pagesBiblio Metric Tool To Assess ThereMiguel MazaNo ratings yet

- Pillay - Geyer - 2016 - Business Clustering Along The M1-N3-N1 Corridor Between Johannesburg and Pretoria, South Africa-1Document18 pagesPillay - Geyer - 2016 - Business Clustering Along The M1-N3-N1 Corridor Between Johannesburg and Pretoria, South Africa-1Minnie.NNo ratings yet

- Knowledge SpilloversDocument10 pagesKnowledge SpilloversGligorcheNo ratings yet

- Emerald Article: The Use of ICT in Rural Firms: A Policy-Orientated Literature ReviewDocument15 pagesEmerald Article: The Use of ICT in Rural Firms: A Policy-Orientated Literature Reviewmrabie2004No ratings yet

- Evolution of WebDocument12 pagesEvolution of Websuraina sulongNo ratings yet

- Evolutions of The WebDocument13 pagesEvolutions of The WebNikita ParidaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0743016715300176 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0743016715300176 MainJoiner Alexánder Hoyos MuñozNo ratings yet

- DRUID Working Paper No. 05-05Document31 pagesDRUID Working Paper No. 05-05FakhrudinNo ratings yet

- Information Technology, Strategic Decision Making Approaches and Organizational Performance in Different Industrial SettingsDocument19 pagesInformation Technology, Strategic Decision Making Approaches and Organizational Performance in Different Industrial SettingsNabeeha66No ratings yet

- Working Paper Series: Jarle Hildrum, Dieter Ernst and Jan FagerbergDocument33 pagesWorking Paper Series: Jarle Hildrum, Dieter Ernst and Jan FagerbergJose Leonardo Simancas GarciaNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument19 pagesResearch Paperniket mehtaNo ratings yet

- The ICT RevolutionDocument26 pagesThe ICT Revolutionlouis_alfaNo ratings yet

- Emerging Ict Trends in Construction Project Teams: A Delphi SurveyDocument17 pagesEmerging Ict Trends in Construction Project Teams: A Delphi SurveybigeazyeNo ratings yet

- 4fibre To The Countryside - A Comparison of Public and CommunityDocument13 pages4fibre To The Countryside - A Comparison of Public and CommunityCamilo OtaloraNo ratings yet

- Internet N Tourism IndustryDocument13 pagesInternet N Tourism IndustryAbhimanyu VermaNo ratings yet

- Routine Production or Symbolic Analysis? India and The Globalization of Architectural Services Paolo TombesiDocument19 pagesRoutine Production or Symbolic Analysis? India and The Globalization of Architectural Services Paolo TombesiJasmine AroraNo ratings yet

- 2019 - EM - Hein - Schreieck - Wiesche - Böhm - Krcmar - The Emergence of Native Multi-Sided Platforms and Their Influence On IncumbentsDocument17 pages2019 - EM - Hein - Schreieck - Wiesche - Böhm - Krcmar - The Emergence of Native Multi-Sided Platforms and Their Influence On IncumbentsWesley MarcosNo ratings yet

- A Multiple Buyer Supplier Relationship in The Context of SMEs Digital Supply Chain ManagementDocument12 pagesA Multiple Buyer Supplier Relationship in The Context of SMEs Digital Supply Chain ManagementMuhamad Aldi RafsanjaniNo ratings yet

- ferreira2015Document20 pagesferreira2015amirhayat15No ratings yet

- Smart Innovative CitiesDocument11 pagesSmart Innovative CitiesTam NguyenNo ratings yet

- Information and Communication TechnologyDocument10 pagesInformation and Communication TechnologyPetar N NeychevNo ratings yet

- Digital Disruption and its Societal ImpactsDocument4 pagesDigital Disruption and its Societal ImpactsRichard RamsawakNo ratings yet

- Digital EconomyDocument22 pagesDigital EconomyPretty PraveenNo ratings yet

- Economic Implications of FTTH Networks: A Cross-Sectional AnalysisDocument26 pagesEconomic Implications of FTTH Networks: A Cross-Sectional AnalysisMikaelBomholtNo ratings yet

- The Determinants of Investment in Information and Communication TechnologiesDocument23 pagesThe Determinants of Investment in Information and Communication TechnologiesKarl JockerNo ratings yet

- KeywordsDocument31 pagesKeywordsayanfeoluwa odeyemiNo ratings yet

- J3ashaolu EnvironmentalbenefitsandDocument6 pagesJ3ashaolu EnvironmentalbenefitsandKevin GovenderNo ratings yet

- The Adoption of Digital Technologies - Investment, Skills, Work OrganisationDocument17 pagesThe Adoption of Digital Technologies - Investment, Skills, Work Organisationalbertus tuhuNo ratings yet

- Abhay Joshi Efficiency and Agglomeration EconomiesDocument22 pagesAbhay Joshi Efficiency and Agglomeration EconomiesAnanya SaikiaNo ratings yet

- Task 4a. Chen & Kamal (2016)Document14 pagesTask 4a. Chen & Kamal (2016)Niek KlaverNo ratings yet

- DigitizationDocument13 pagesDigitizationRICHMOND GYAMFI BOATENGNo ratings yet

- Ei 926Document18 pagesEi 926Jackson DenerNo ratings yet

- Misq 42 1 25Document32 pagesMisq 42 1 25406536927No ratings yet

- Holtgrewe14 NewnewtechDocument17 pagesHoltgrewe14 NewnewtechJagvinder SinghNo ratings yet

- The Magnitude and Causes of Agglomeration Economies: IMDEA, Universidad Carlos III and CEPRDocument19 pagesThe Magnitude and Causes of Agglomeration Economies: IMDEA, Universidad Carlos III and CEPRThoon ThoonNo ratings yet

- Returns To ICT SkillsDocument94 pagesReturns To ICT SkillsAugustine MalijaNo ratings yet

- Special Issue Introduction Digital TechnologiesDocument48 pagesSpecial Issue Introduction Digital TechnologiessarathNo ratings yet

- Building A Complementary Agenda For Business Process Management and Digital InnovationDocument13 pagesBuilding A Complementary Agenda For Business Process Management and Digital InnovationharutojoshuaNo ratings yet

- Changing Trade Pattern, ICT, and Employment Evidence Across CountriesDocument20 pagesChanging Trade Pattern, ICT, and Employment Evidence Across CountriesJosip IžakovićNo ratings yet

- Conceptual Model For Agro-Based Entrepreneur's ICT Engagement, Usage, and Economic EmpowermentDocument7 pagesConceptual Model For Agro-Based Entrepreneur's ICT Engagement, Usage, and Economic EmpowermentCenter for Promoting Education and Research(CPER), USANo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument17 pagesChapter OneAndrew JamesNo ratings yet

- Agglomeration Economies - A Literature ReviewDocument15 pagesAgglomeration Economies - A Literature ReviewWang XiaoNo ratings yet

- Protocols for Tracking Information Content in the Existing BIMFrom EverandProtocols for Tracking Information Content in the Existing BIMNo ratings yet

- GAT MCQs Finance Management SciencesDocument5 pagesGAT MCQs Finance Management SciencesMuhammad NajeebNo ratings yet

- Interest Rate NotesDocument11 pagesInterest Rate NotesjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Data VisulizationDocument2 pagesData VisulizationjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Money and Banking (Money Multiplier Assignment)Document2 pagesMoney and Banking (Money Multiplier Assignment)jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- TheoilsectorDocument24 pagesTheoilsectorjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- E3sconf Uesf2021 05010Document10 pagesE3sconf Uesf2021 05010jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- GAT Subject Economics MCQs 1 50Document6 pagesGAT Subject Economics MCQs 1 50Nadeem ZiaNo ratings yet

- Mediation ModelsDocument10 pagesMediation ModelsJaap Van NesNo ratings yet

- FF OverheadsDocument8 pagesFF OverheadsjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- EDIG-Research-Paper-No.-1 BanglaDocument70 pagesEDIG-Research-Paper-No.-1 BanglajamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 04 Irfan Ul Haque FinalDocument30 pages04 Irfan Ul Haque FinaljamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 95-Harunnurrasyid Et Al. (pp.2060-2078)Document19 pages95-Harunnurrasyid Et Al. (pp.2060-2078)jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Zzzhao 2000Document33 pagesZzzhao 2000jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- w19898 2014Document13 pagesw19898 2014jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Li XiangDocument10 pagesLi XiangjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Zheng 2010Document7 pagesZheng 2010jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Global Concentration FinalDocument28 pagesGlobal Concentration FinaljamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Gearing Up For The Future of Manufacturing in BangladeshDocument90 pagesGearing Up For The Future of Manufacturing in BangladeshjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 6058 BanglaDocument30 pages6058 BanglajamilkhannNo ratings yet

- A412-Final BanglaDocument7 pagesA412-Final BanglajamilkhannNo ratings yet

- IJSE 10 2016 0281banglaDocument30 pagesIJSE 10 2016 0281banglajamilkhannNo ratings yet

- CPSD BangladeshDocument172 pagesCPSD BangladeshjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- J Jtrangeo 2020 102653Document10 pagesJ Jtrangeo 2020 102653jamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 9-Concentration-and-Competition-in-the-Non BanglaDocument9 pages9-Concentration-and-Competition-in-the-Non BanglajamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 1678-Article Text-6479-1-10-20220218 IndiaDocument18 pages1678-Article Text-6479-1-10-20220218 IndiajamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Sub Rah Many Am 2009Document16 pagesSub Rah Many Am 2009eng1858260No ratings yet

- Economic Reforms and Market Competition in India AssessmentDocument19 pagesEconomic Reforms and Market Competition in India AssessmentjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 0703 HirtDocument19 pages0703 HirtjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- 7up2 BangladeshDocument24 pages7up2 BangladeshjamilkhannNo ratings yet

- Final Portfolio Cover LetterDocument2 pagesFinal Portfolio Cover Letterapi-321017157No ratings yet

- Achmad Nurdianto, S.PD: About MeDocument2 pagesAchmad Nurdianto, S.PD: About Medidon knowrezNo ratings yet

- Dyno InstructionsDocument2 pagesDyno InstructionsAlicia CarrNo ratings yet

- D Series: Instruction ManualDocument2 pagesD Series: Instruction ManualMartin del ValleNo ratings yet

- Switches Demystified Assembly PDFDocument1 pageSwitches Demystified Assembly PDFkocekoNo ratings yet

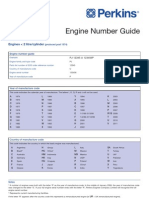

- Perkins Engine Number Guide PP827Document6 pagesPerkins Engine Number Guide PP827Muthu Manikandan100% (1)

- Internship Reflection PaperDocument8 pagesInternship Reflection Paperapi-622170417No ratings yet

- Günter Fella: Head of Purchasing AutomotiveDocument2 pagesGünter Fella: Head of Purchasing AutomotiveHeart Touching VideosNo ratings yet

- Ett 531 Motion Visual AnalysisDocument4 pagesEtt 531 Motion Visual Analysisapi-266466498No ratings yet

- MDP Module 2Document84 pagesMDP Module 2ADITYA RAJ CHOUDHARYNo ratings yet

- Call Log ReportDocument44 pagesCall Log ReportHun JhayNo ratings yet

- Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 LicenseDocument4 pagesCreative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 LicenseAnindito W WicaksonoNo ratings yet

- Synopsis MphilDocument10 pagesSynopsis MphilAyesha AhmadNo ratings yet

- ASM Product Opportunity Spreadsheet2Document48 pagesASM Product Opportunity Spreadsheet2Yash SNo ratings yet

- Economics Not An Evolutionary ScienceDocument17 pagesEconomics Not An Evolutionary SciencemariorossiNo ratings yet

- Word ShortcutsDocument3 pagesWord ShortcutsRaju BNo ratings yet

- jrc122457 Dts Survey Deliverable Ver. 5.0-3Document46 pagesjrc122457 Dts Survey Deliverable Ver. 5.0-3Boris Van CyrulnikNo ratings yet

- Challan FormDocument2 pagesChallan FormSingh KaramvirNo ratings yet

- Operations Management (Zheng) SU2016 PDFDocument9 pagesOperations Management (Zheng) SU2016 PDFdarwin12No ratings yet

- Ac and DC MeasurementsDocument29 pagesAc and DC MeasurementsRudra ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Homework1 SKKK1113 1112-2Document1 pageHomework1 SKKK1113 1112-2Khairul Anwar Abd HamidNo ratings yet

- CV Template DixieDocument3 pagesCV Template DixieDarybelle BusacayNo ratings yet

- KiaOptima Seccion 002Document7 pagesKiaOptima Seccion 002Luis Enrique PeñaNo ratings yet

- Technical Report Writing For Ca2 ExaminationDocument6 pagesTechnical Report Writing For Ca2 ExaminationAishee DuttaNo ratings yet

- G8 - Light& Heat and TemperatureDocument49 pagesG8 - Light& Heat and TemperatureJhen BonNo ratings yet

- Power Transformer Fundamentals: CourseDocument5 pagesPower Transformer Fundamentals: CoursemhNo ratings yet

- Grade7Research 1st Quarter MeasuringDocument17 pagesGrade7Research 1st Quarter Measuringrojen pielagoNo ratings yet