Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rnoti p1007

Uploaded by

Ranko0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views2 pagesTerence Tao struggled with studying in graduate school, often procrastinating and not preparing adequately for his qualifying exams, known as "generals". During his generals, Tao was only able to answer basic questions on some topics due to his lack of preparation, but was saved by luck when the examiners asked him easier questions on another topic that he had studied more. He narrowly passed his exams, but his experience showed him that he needed to develop better study habits to succeed in his graduate studies and career.

Original Description:

Original Title

rnoti-p1007

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentTerence Tao struggled with studying in graduate school, often procrastinating and not preparing adequately for his qualifying exams, known as "generals". During his generals, Tao was only able to answer basic questions on some topics due to his lack of preparation, but was saved by luck when the examiners asked him easier questions on another topic that he had studied more. He narrowly passed his exams, but his experience showed him that he needed to develop better study habits to succeed in his graduate studies and career.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views2 pagesRnoti p1007

Uploaded by

RankoTerence Tao struggled with studying in graduate school, often procrastinating and not preparing adequately for his qualifying exams, known as "generals". During his generals, Tao was only able to answer basic questions on some topics due to his lack of preparation, but was saved by luck when the examiners asked him easier questions on another topic that he had studied more. He narrowly passed his exams, but his experience showed him that he needed to develop better study habits to succeed in his graduate studies and career.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Early Career

A Close Call: How a When I entered graduate study at Princeton, I brought

my study habits (or lack thereof) with me. At the time in

Near Failure Propelled Princeton, the graduate classes did not have any home-

work or tests; the only major examination one had to pass

Me to Succeed (apart from some fairly easy language requirements) were

the dreaded “generals’’—the oral qualifying exams, often

lasting over two hours, that one would take in front of

Terence Tao three faculty members, usually in one’s second year. The

questions would be drawn from five topics: real analysis,

For as long as I can remember, I was always fascinated by complex analysis, algebra, and two topics of the student’s

numbers and the formal symbolic operations of mathe- choice. For most of the other graduate students in my year,

matics, even before I knew the uses of mathematics in the preparing for the generals was a top priority; they would

real world. One of my earliest childhood memories was read textbooks from cover to cover, organise study groups,

demanding that my grandmother, who was washing the and give each other mock exams. It had become a tradition

windows, put detergent on the windows in the shape of for every graduate student taking the generals to write up

numbers. When I was particularly rowdy as a child, my the questions they received and the answers they gave for

parents would sometimes give me a math workbook to future students to practice. There were even skits performed

work on instead, which I was more than happy to do. To (with much gallows humor) on hypothetical general exams

me, mathematics was an activity to do for fun, and I would with a “death committee’’ of three faculty that were partic-

play with it endlessly. ularly notorious for being harsh on the examinee.

Perhaps because of this, I found my mathematics classes I managed to brush off almost all of this. I went to the

at school to be easy—perhaps too easy—even after skipping classes that I enjoyed, dropped out of the ones I did not,

a number of grades. If a lecture was on a topic I found in- and did some desultory reading of textbooks but spent an

teresting, I would use the class time to experiment with the embarrassingly large fraction of my early graduate years

material, perhaps finding alternate derivations of some step messing around online (having discovered the World Wide

Web in my first year) or playing computer games until late

the teacher did on the board, or to plug in some numbers

at night at the graduate dormitory computer room. For

to try out special cases and look for patterns. If instead I

my general topics, I chose harmonic analysis—which I

found the topic to be dull, I would doodle like any other

had studied for my master’s degree back in Australia—and

bored student. In either case, I did not take particularly

analytic number theory. Feeling that analysis was my strong

detailed notes, nor did I ever develop any systematic study

suit, I only spent a few days reviewing real, complex, and

habits. I would be able to improvise my way through my

harmonic analysis; the bulk of my study, such as it was,

homework and exams, for instance, by cramming through was devoted instead to algebra and analytic number theory.

the textbook a few days before a final exam and perhaps All in all, I probably only did about two weeks’ worth of

playing a bit more with the parts of the class material that preparation for the generals, while my fellow classmates

I really liked. It tended to work fairly well all the way up had devoted months. Nevertheless, I felt quite confident

to my undergraduate classes. The courses that I enjoyed, I going into the exam.

aced; classes that I found boring, I only barely passed, or The exam started off reasonably well, as they asked me

(in two cases) failed altogether. (One class was a FORTRAN to present the harmonic analysis that I had prepared, which

programming class in which I had refused to learn FOR- was mostly material based on my master’s thesis and specif-

TRAN on the grounds that I already knew how to program ically on a theorem in harmonic analysis known as the T(b)

in BASIC; the other was a quantum mechanics class in theorem. However, as they moved away from that topic,

which we were warned well ahead of time that the final the shallowness of my preparation in the subject showed

exam would require us to write a short essay on the history quite badly. I would be able to vaguely recall a basic result

of the subject, which I totally ignored until the day of the in the field, but not state it accurately, give a correct proof,

exam, during which I still recall having to be escorted from or describe what it was used for or connected to. I have a

the examination room in tears.) Despite this, I ended up distinct memory of the examiners asking easier and easier

graduating from my university with honors at the top of questions, to get me to a point where I would actually be

my class—but it was a small university with a tiny honors able to give a satisfactory answer; they spent several min-

program, and in fact, there were only two other honors utes, for instance, painfully walking me through a deriva-

students in mathematics in my year! tion of the fundamental solution for the Laplacian. I had

enjoyed playing with harmonic analysis for its own sake

Terence Tao is a professor of mathematics at the University of California, and had never paid much attention as to how it was used

Los Angeles. His email address is tao@math.ucla.edu. in other fields such as PDEs or complex analysis. Presented,

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1090/noti2122 for instance, with the Fourier multiplier for the propagator

August 2020 Notices of the American Mathematical Society 1007

Early Career

of the wave equation, I did not recognise it at all, and was

unable to say anything interesting about it. My Journey from

At this point, I was saved by a stroke of pure luck as

the questioning then turned to my other topic of analytic

Slippery Rock to Duluth

number theory. Only one of the examiners had an exten-

sive background in number theory, but he had mistakenly Joseph Gallian

thought I had selected algebraic number theory as my

topic, and so all the questions he had prepared were not My journey from Slippery Rock State College in Pennsyl-

appropriate. As such, I only got very standard questions vania in 1966 to the University of Minnesota Duluth in

in analytic number theory (e.g., prove the prime number 1972 had quite a few twists and turns. In 1966, I received

theorem, Dirichlet’s theorem, etc.), and these were topics TA offers from Minnesota, Kansas, Purdue, and Michigan

that I actually did prepare for, so I was able to answer these State. About a week before the deadline for accepting offers,

questions quite easily. The rest of the exam then went fairly I selected Minnesota. A few days later, Kansas called to ask

quickly as none of the examiners had prepared any truly me if I would be willing to come to KU on a five-year NASA

challenging algebra questions. Fellowship. I was delighted to accept.

After many nerve-wracking minutes of closed-door de-

Because the Rock was almost exclusively a school for

liberation, the examiners did decide to (barely) pass me;

the preparation of K–12 teachers, my course work there

however, my advisor gently explained his disappointment

did not adequately prepare me for graduate-level courses.

at my performance, and how I needed to do better in the

Instead, I took courses intended for juniors and seniors.

future. I was still largely in a state of shock—this was the

Fortunately, I had a charismatic abstract algebra teacher

first time I had performed poorly on an exam that I was

genuinely interested in performing well in. But it served as named Lee Sonneborn for both semesters. I was so en-

an important wake-up call and a turning point in my career. thralled with that course that I took an independent study

I began to take my classes and studying more seriously. I course in permutation groups and participated in a weekly

listened more to my fellow students and other faculty, and seminar on infinite group theory. By the middle of my

I cut back on my gaming. I worked particularly hard on all second semester, I decided to do a PhD thesis on infinite

of the problems that my advisor gave me, in the hopes of groups under Sonneborn. This plan abruptly changed a few

finally impressing him. I certainly didn’t always succeed at months later when Sonneborn moved to Michigan State.

this—for instance, the first problem my advisor gave me, I Disappointed, but not deterred, I decided that I would do

was only able to solve five years after my PhD—but I poured a thesis with Dick Phillips, who was another infinite group

substantial effort into the last two years of my graduate theorist participating in the infinite group theory seminar.

study, wrote up a decent thesis and a number of publi- But it was not to be. In the fall of 1967, Phillips told me

cations, and began the rest of my career as a professional that he would be going to Michigan State the next year.

mathematician. In retrospect, nearly failing the generals The departure of both of my potential thesis advisors

was probably the best thing that could have happened to prompted me to apply to grad school at Michigan State,

me at the time. Utah, Illinois, and Notre Dame, all of which had infinite

My write-up of my general exams experience is still avail- group theorists. When I received a three-year fellowship

able online. I have been told that it has been a significant from Notre Dame, I accepted. Shortly after arriving at

source of comfort to the more recent graduate students at Notre Dame, I approached the infinite group theorist about

Princeton. working with him. As luck would have it, he told me that

this was his final year at Notre Dame. The next best option

was to work with Warren Wong, who was one of hundreds

of people working on the classification of finite simple

groups. Wong agreed to take me on, but he said he would

be on sabbatical the next year in New Zealand and I was

welcome to join him there. This did not appeal to me and

my wife, so I declined. That left me with three options:

transfer, abandon group theory, or do a thesis with Karl

Kronstein, whose only publication was on representations

Terence Tao of finite groups, a subject about which I knew nothing. I

opted for the last.

Credits

Author photo is courtesy of Reed Hutchinson/UCLA. Joseph Gallian is a professor of mathematics at the University of Minnesota

Duluth. His email address is jgallian@d.umn.edu.

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1090/noti2119

1008 Notices of the American Mathematical Society Volume 67, Number 7

You might also like

- An Inquiry Into Science Education Where The Rubber Meets The RoadDocument38 pagesAn Inquiry Into Science Education Where The Rubber Meets The RoadImam A. RamadhanNo ratings yet

- An Open Letter To The Next Generation: James D. PattersonDocument2 pagesAn Open Letter To The Next Generation: James D. PattersonLuis Gerardo Tequia TequiaNo ratings yet

- 2004 Patterson Open LetterDocument2 pages2004 Patterson Open LetterIvan Alexander Salazar VargasNo ratings yet

- Secrets Straight A StudentsDocument2 pagesSecrets Straight A StudentsRainbow ITGNo ratings yet

- The Pleasure of Finding Things Out: Amanda BeesonDocument3 pagesThe Pleasure of Finding Things Out: Amanda BeesonAnand KrishNo ratings yet

- Interview With Peter SarnakDocument4 pagesInterview With Peter SarnakFrederickSharmaNo ratings yet

- Math10 Essay1 Parungao JhaylordeDocument2 pagesMath10 Essay1 Parungao JhaylordeLorde FloresNo ratings yet

- Open Letter To Next GenerationDocument0 pagesOpen Letter To Next GenerationJose CornettNo ratings yet

- TrigonometryDocument20 pagesTrigonometryteachopensourceNo ratings yet

- Academic Acheivement ReflectionDocument2 pagesAcademic Acheivement Reflectionapi-631061361No ratings yet

- Maths Reduced SizeDocument943 pagesMaths Reduced SizeTuan TranNo ratings yet

- How To Become A Straight-A Student - The Unconventional Strategies Real College Students Use To Score High While Studying Less (PDFDrive)Document315 pagesHow To Become A Straight-A Student - The Unconventional Strategies Real College Students Use To Score High While Studying Less (PDFDrive)Jorge Alejandro Acosta Bravo33% (3)

- MathsDocument975 pagesMathsAbdul Wares100% (1)

- 614 - 12 - GW B2 Workbook AudioscriptDocument12 pages614 - 12 - GW B2 Workbook AudioscriptЕвгения СенинаNo ratings yet

- Action Research in Science - Assessment StrategiesDocument19 pagesAction Research in Science - Assessment StrategiesGracie O. ChingNo ratings yet

- Peer Instruction With ArticleDocument21 pagesPeer Instruction With ArticleMilica JovkovicNo ratings yet

- Interviews With Prof. P.A.M. Dirac - Symmetry SeekerDocument415 pagesInterviews With Prof. P.A.M. Dirac - Symmetry SeekerDeepak HNo ratings yet

- ReflectionDocument4 pagesReflectionapi-288668714No ratings yet

- BSCS Final Term Paper, 021.Document2 pagesBSCS Final Term Paper, 021.Bilal UsmanNo ratings yet

- Chem Camp From The Other SideDocument5 pagesChem Camp From The Other SideAnonymous Qy7ATd0nNo ratings yet

- MathsDocument917 pagesMathsNguyễn Hữu Quốc Khánh100% (1)

- Vignette Draft 3Document2 pagesVignette Draft 3api-250452657No ratings yet

- The Making of A Radical Teacher - James FulcherDocument4 pagesThe Making of A Radical Teacher - James Fulchersaba amiriNo ratings yet

- Never Too Old To Learn: Ronald G. DriggersDocument2 pagesNever Too Old To Learn: Ronald G. DriggerssankhaNo ratings yet

- (Math Horizons 2005-Sep Vol. 13 Iss. 1) Review by - Elizabeth D. Russell - All The Math You Missed (2005) (10.2307 - 25678565) - Libgen - LiDocument2 pages(Math Horizons 2005-Sep Vol. 13 Iss. 1) Review by - Elizabeth D. Russell - All The Math You Missed (2005) (10.2307 - 25678565) - Libgen - LiFurkan Bilgekagan ErtugrulNo ratings yet

- Boaler 2015 Why Growth Mindsets Are Necessary To Save Math ClassDocument8 pagesBoaler 2015 Why Growth Mindsets Are Necessary To Save Math ClasscynthiaNo ratings yet

- My Physics PortfolioDocument14 pagesMy Physics PortfolioPauline Ann QuitonNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Reading Comp. C.CDocument2 pagesUnit 2 Reading Comp. C.Chbat saidNo ratings yet

- Torch Firehose Chapter5Document6 pagesTorch Firehose Chapter5Bob SmithNo ratings yet

- Read AloudDocument5 pagesRead Aloudapi-610714301No ratings yet

- 489 SyllabusnewmanDocument3 pages489 Syllabusnewmanapi-330479285No ratings yet

- Ch09 PDF Official Sat Study Guide Sample Reading Test QuestionsDocument32 pagesCh09 PDF Official Sat Study Guide Sample Reading Test QuestionsyawahabNo ratings yet

- An Infinitely Large NapkinDocument617 pagesAn Infinitely Large Napkinilea.cristianNo ratings yet

- A Life in EducationDocument19 pagesA Life in EducationMayank AjugiaNo ratings yet

- Why Science Fair Sucks and How You Can Save It: A Survival Manual for Science TeachersFrom EverandWhy Science Fair Sucks and How You Can Save It: A Survival Manual for Science TeachersNo ratings yet

- Perry's Stages of Cognitive Development: Rapaport's Speculation, Part 1: Perhaps We Begin As Dualists Because We Begin byDocument10 pagesPerry's Stages of Cognitive Development: Rapaport's Speculation, Part 1: Perhaps We Begin As Dualists Because We Begin bynicduni0% (1)

- What I Learned by Teaching Real AnalysisDocument3 pagesWhat I Learned by Teaching Real AnalysisB.y. NgNo ratings yet

- 11 Perrys Stages of Cognitive Development PDFDocument10 pages11 Perrys Stages of Cognitive Development PDFPardon Tanaka MatyakaNo ratings yet

- CEP Lesson Plan Form: Colorado State University College of Health and Human SciencesDocument4 pagesCEP Lesson Plan Form: Colorado State University College of Health and Human Sciencesapi-502132722No ratings yet

- Computational PhysicsDocument3 pagesComputational Physicsnatnael kahsayNo ratings yet

- Reflective Essay A Lessons Learned in High School - 760 Words CramDocument1 pageReflective Essay A Lessons Learned in High School - 760 Words Cramhitakshiverma01No ratings yet

- Intervention/Innovation: Research QuestionsDocument15 pagesIntervention/Innovation: Research Questionsapi-621535429No ratings yet

- Blog 1Document2 pagesBlog 1api-334752450No ratings yet

- CEP Lesson Plan Form: Colorado State University College of Health and Human SciencesDocument4 pagesCEP Lesson Plan Form: Colorado State University College of Health and Human Sciencesapi-502132722No ratings yet

- MathsDocument1,061 pagesMaths鹿与旧都No ratings yet

- Cougar News: The Mayor Visited Carver Middle SchoolDocument4 pagesCougar News: The Mayor Visited Carver Middle SchoolbrooksgrayNo ratings yet

- How To Become A Good Theoretical PhysicistDocument16 pagesHow To Become A Good Theoretical PhysicistrasromeoNo ratings yet

- 2018 - Book - Physics From Symmetry PDFDocument294 pages2018 - Book - Physics From Symmetry PDFPablo Marinho100% (2)

- A Limestone Way of Learning-1Document4 pagesA Limestone Way of Learning-1Susan Naomi BernsteinNo ratings yet

- Making Mathematics Relevant To Engineering StudentsDocument10 pagesMaking Mathematics Relevant To Engineering StudentsJames WangNo ratings yet

- Grade/ Content Area Lesson Title: Motivations of The Characters in of Mice and MenDocument6 pagesGrade/ Content Area Lesson Title: Motivations of The Characters in of Mice and Menapi-399568661No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Re EctionDocument5 pagesLesson Plan Re EctionbarryjglNo ratings yet

- Santas Stuck LessonDocument3 pagesSantas Stuck Lessonapi-552864014No ratings yet

- Grade 12 Physics Exam Questions and AnswersDocument3 pagesGrade 12 Physics Exam Questions and AnswersGinger80% (5)

- Parent BrochureDocument3 pagesParent Brochureapi-564220362No ratings yet

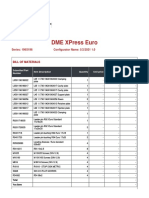

- Dme Xpress Euro: Series: 196X196 Configurator Name: 5/2/2021 1.0Document3 pagesDme Xpress Euro: Series: 196X196 Configurator Name: 5/2/2021 1.0Ahmed SamirNo ratings yet

- Urban Planning in IndiaDocument22 pagesUrban Planning in IndiaSakshi MohataNo ratings yet

- Pavers - ACN - PCN - Advantages and Shortfalls of The SystemDocument1 pagePavers - ACN - PCN - Advantages and Shortfalls of The Systemanant11235No ratings yet

- MarketingDocument15 pagesMarketingrinnimaruNo ratings yet

- 17 CDTC SolutionsDocument18 pages17 CDTC SolutionsJohn Paul Marin ManzanoNo ratings yet

- 400kv Bhachunda-SBC ReportDocument72 pages400kv Bhachunda-SBC Report400KVNo ratings yet

- DriveworksXpress TutorialDocument21 pagesDriveworksXpress TutorialErcan AkkayaNo ratings yet

- Slurry Pumps Service ClassesDocument2 pagesSlurry Pumps Service ClassesCarlos Esaú López Gómez100% (1)

- 3 - Phase Power SupplyDocument12 pages3 - Phase Power SupplyGrojean David CañedoNo ratings yet

- Histology: Neuron Cells Types and StructureDocument7 pagesHistology: Neuron Cells Types and StructureAli HayderNo ratings yet

- DISC 322-Optimization Methods For Management Science - Sec 2 - Dr. Muhammad Tayyab - Spring 2020 PDFDocument6 pagesDISC 322-Optimization Methods For Management Science - Sec 2 - Dr. Muhammad Tayyab - Spring 2020 PDFMuhammad UsmanNo ratings yet

- Siddaganga Institute Technology: Injection MouldingDocument12 pagesSiddaganga Institute Technology: Injection MouldingPRAVEEN BOODAGOLINo ratings yet

- 170 Python ProjectsDocument15 pages170 Python Projectsrajeswari.bommanaboinaNo ratings yet

- The Foundations: Logic and Proofs Kenneth H. Rosen 7 EditionDocument17 pagesThe Foundations: Logic and Proofs Kenneth H. Rosen 7 EditionMahir SohanNo ratings yet

- Customer Segmentation With RFM AnalysisDocument3 pagesCustomer Segmentation With RFM Analysissatishjb29No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1526612521006551 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S1526612521006551 MainIyan MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Ebook PDF Designing The User Interface Strategies For Effective Human Computer Interaction Global EditionDocument41 pagesEbook PDF Designing The User Interface Strategies For Effective Human Computer Interaction Global Editionmichael.green973No ratings yet

- Retention of Special Education TeachersDocument15 pagesRetention of Special Education TeachersAmanda JohnsonNo ratings yet

- E-Fact 14 - Hazards and Risks Associated With Manual Handling in The WorkplaceDocument30 pagesE-Fact 14 - Hazards and Risks Associated With Manual Handling in The WorkplaceFar-East MessiNo ratings yet

- DLL 10-11Document5 pagesDLL 10-11LORIBELLE MALDEPENANo ratings yet

- Coding Decoding Study NotesDocument10 pagesCoding Decoding Study NotesDhanashree ShahareNo ratings yet

- Oaa000009 Sigtran Protocol Issue2.0-20051111-ADocument37 pagesOaa000009 Sigtran Protocol Issue2.0-20051111-AFranceNo ratings yet

- Battle Without Honor or HumanityDocument28 pagesBattle Without Honor or Humanityguillaumejb100% (3)

- Lesson Presentation Risk Identification: Prepared By: Jamaal T. Villapaña, MBADocument5 pagesLesson Presentation Risk Identification: Prepared By: Jamaal T. Villapaña, MBAJolina PahayacNo ratings yet

- 09 - Introdution 01Document28 pages09 - Introdution 01DiveshNo ratings yet

- Practice Test (1-10)Document40 pagesPractice Test (1-10)tamNo ratings yet

- Condensing Unit and Refrigeration System Installation & Operations ManualDocument43 pagesCondensing Unit and Refrigeration System Installation & Operations ManualdarwinNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Development Partnerships Gap BDDocument13 pagesBridging The Development Partnerships Gap BDVipul JainNo ratings yet

- Character CreationDocument39 pagesCharacter Creationotaku PaiNo ratings yet

- Trading With Advance Technical Tools & Options Strategy Delhi BrochureDocument3 pagesTrading With Advance Technical Tools & Options Strategy Delhi BrochureKrishnendu ChowdhuryNo ratings yet