Professional Documents

Culture Documents

THEMEHELP LTD. v. WEST AND OTHERS (1993 T. N

THEMEHELP LTD. v. WEST AND OTHERS (1993 T. N

Uploaded by

Nguyễn Quang0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views24 pagesOriginal Title

THEMEHELP_LTD._v._WEST_AND_OTHERS_[1993_T._N

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views24 pagesTHEMEHELP LTD. v. WEST AND OTHERS (1993 T. N

THEMEHELP LTD. v. WEST AND OTHERS (1993 T. N

Uploaded by

Nguyễn QuangCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 24

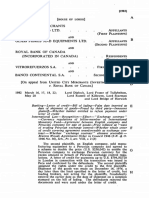

84

11996)

[CouRT OF APPEAL]

THEMEHELP LTD. v. WEST anp OTHERS

[1993 T. No. 7076}

1995 Feb. 21, 22; Balcombe, Evans and Waite L.JJ.

April 6

Guarantee—Performance guarantee—Enforcement—Purchase of busi-

ness—Part of price secured by guarantee—Buyers alleging fraud by

sellers—Action for rescission or damages—Guarantor not party to

‘action—Whether sellers to be restrained from enforcing guarantee

pending trial

The buyers agreed to purchase the sellers’ business for £1:6m.

under a contract which provided for payment of £100,000 on

completion and of the balance by subsequent instalments, the

third and largest of which was secured up to £775,000 by a third

party performance guarantee. After the first instalment had been

paid the buyers brought an action for rescission, alleging

fraudulent misrepresentation by the sellers, who denied the

allegation and proposed to give notice to the guarantors to

enforce the guarantee. The buyers applied for an interlocutory

injunction to restrain the sellers from giving notice to the

guarantors, who were not a party to the action, until trial. The

judge granted the injunction on the basis that the evidence was

sufficient to raise a seriously arguable case that the only

reasonable inference that could be drawn from the circumstances

was that the sellers had been fraudulent.

(On the sellers’ appeal:—

Held, dismissing the appeal (Evans L.J. dissenting), (1) that

although a performance guarantee was an autonomous contract

not to be interfered with on grounds extraneous to the guarantee

itself, where fraud was raised between the parties to the main

transaction before any question of enforcement of the guarantee

arose as between beneficiary and guarantor, to grant an injunction

restraining the beneficiary's rights of enforcement did not amount

to a threat to the integrity of the performance guarantee; and

that, accordingly, the judge had jurisdiction to entertain the

application for an injunction (post, pp. 98H-99c, 107F-G)

(2) That the judge had been entitled to conclude on the

evidence that the buyers had showed a seriously arguable case

that fraud was the only realistic inference; that, if the sellers were

allowed to claim under the guarantee, the guarantors would be

entitled to call for immediate recoupment of the £775,000 secured

and justice required that the buyers should not be obliged to

make payment to the guarantors of moneys which they had only

an uncertain prospect of recovering from the sellers at trial even

if wholly successful; and that, accordingly, the judge’s exercise of

his discretion could not be disturbed (post, pp. 100p-£, H-101c,

106B-C, &-G, 107F-<).

United City Merchants (Investments) Lid. v. Royal Bank of

Canada [1983] | A.C. 168, H.L(E) and United Trading

Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab Bank Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lloyd’s

Rep. 554, C.A. considered.

85

QB. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.)

Per Evans L.J. Unless the fraud exception applies, as to which

no finding has been made, the banks are liable to pay the sellers

the sums due under the sales agreement and the buyers cannot

prevent the sellers from recovering payment of that sum without

themselves acting unlawfully and in breach of the agreement.

Accordingly, the injunction is contrary to legal principle (post,

p. 102p-#).

Decision of Mr. Maurice Kay Q.C., sitting as a deputy High

Court judge in the Queen’s Bench Division, affirmed.

The following cases are referred to in the judgments:

American Cyanamid Co. v. Ethicon Ltd. [1975] A.C. 396; [1975] 2 W.L.R. 316;

(1975) 1 All E.R. 504, H.L.(E.)

Bolivinter Oil S.A. v. Chase Manhattan Bank N.A, (Practice Note) [1984]

1 WLR. 392; [1984] 1 AIL E.R. 351; [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 251, C.A.

"Elian and Rabbath v. Matsas [1966] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 495, C.A.

Hadmor Productions Ltd. v. Hamilton [1983] | A.C. 191; [1982] 2 W.L.R. 322;

[1982] | AN E.R. 1042, H.L.(E.)

Hamzeh Malas & Sons v. British Imex Industries Ltd. [1958] 2 Q.B. 127;

[1958] 2 W.L.R. 100; [1958] | All E.R. 262, C.A.

Harbottle (R. D.) (Mercantile) Ltd. v. National Westminster Bank Ltd. (1978)

QB. 146; [1977] 3 W.L.R. 752; [1977] 2 All E.R. 862

Howe Richardson Scale Co. Ltd. v. Polimex-Cekop [1978] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 161,

Iragi Ministry of Defence v. Arcepey Shipping Co. S.A. {1981] Q.B. 65; [1980]

2 W.L.R. 488; [1980] 1 All E.R. 480

Owen (Edward) Engineering Ltd. v. Barclays Bank International Lid. {1978}

QB. 159; [1977] 3 W.L.R. 764; [1978] | All E.R. 976, C.A.

Potton Homes Ltd. v. Coleman Contractors Ltd. (1984) 28 B.L.R. 19, C.A.

United City Merchants (Investments) Ltd. v. Royal Bank of Canada [1983]

1 A.C, 168; [1982] 2 W.L.R. 1039; [1982] 2 All E.R. 720, H.L.(E.)

United Norwest Co-operatives Ltd. y. Johnstone (unreported), 6 December

1994; Court of Appeal (Civil Division) Transcript No. 1482 of 1994,

CA.

United Trading Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab Bank Ltd. (Note) (1985

2 Lloyd’s Rep. 554, C.A.

The following additional cases were cited in argument:

Bellenden (formerly Satterthwaite) v. Satterthwaite [1948] | All E.R. 343, C.A.

G. v. G. (Minors: Custody Appeal) [1985] 1 W.L.R. 647; [1985] 2 All E.R.

225, H.L(E.)

INTERLOCUTORY APPEAL from Mr. Maurice Kay QC. sitting as a

deputy High Court judge in the Queen’s Bench Division.

The plaintiffs, Themehelp Ltd., agreed to purchase a business by

instalments from the defendants, Raymond West, Helga Patricia Pimm

and Anthony Jan O’Neill. The third and largest instalment was secured

up to a limit of £750,000 by a performance guarantee obtained from the

guarantors, 3i Group Plc. and Midland Montague Investments Ltd. Under

86

‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) [1996]

the share sale agreement the defendants were entitled to give notice to the

guarantors to make good any default by the plaintiffs up to the limit of

the guarantee. After the payment of the first instalment the plaintiffs

started proceedings for rescission and damages on the ground of fraudulent

misrepresentation by the defendants. It was alleged that there had been

included in the profit projections on which the sale price had been

negotiated, that demand from a major customer would continue, though

not necessarily at the same level, and that the defendants had been aware

by the date of execution of the agreement that there was no longer any

basis for that assumption. The defendants denied misrepresentation and

insisted on their right to treat the plaintiffs as being in default and to give

notice to the guarantors to enforce the guarantee. The plaintiffs applied in

the proceedings, to which the guarantors were not a party, for an

interlocutory injunction to restrain the defendants from giving notice to

the guarantors until trial. On 18 June 1993 the deputy judge granted the

injunction against the first and second defendants.

By a notice of appeal dated 9 July 1993 the first and second defendants

appealed on the grounds, inter alia, that (1) there was no sufficient or

proper evidence on which the judge could have concluded, as he had, that

there was a good arguable case that the only realisitic inference was that

the first and second defendants had been fraudulent in relation to the

entry by the plaintiff into the share sale agreement; (2) the judge had been

wrong in law in holding that it was open to him to grant an inj

the plaintiff in the terms granted without proof of fraud on the part of the

first and second defendants and to the knowledge of the guarantors,

and/or where the guarantors were not a party to the proceedings, and had

thereby exercised his discretion to grant the injunction contrary to

principle; (3) the judge had erred in law in holding that the plaintiff did

not have to demonstrate fraud on the part of the first and second

defendants in the calling down of the guarantees; (4) the judge ought to

have held that unless it was seriously arguable on the material available

to him that the only reasonable inference was that the defendants, were’

they to call on the guarantees, would be acting fraudulently, to the

knowledge of the guarantors, in so doing, he should not grant the

injunction sought and, on the material available to him, it was not so

arguable and, accordingly, he had exercised his discretion wrongly and

contrary to principle; (5) in coming to the conclusion he had and in

deciding to grant the injunction the judge had effectively applied the

argument which had been rejected by the Court of Appeal in Bolivinter

Oil S.A. v. Chase Manhattan Bank [1984] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 251 and ignored

the strictures of the Court of Appeal in that case and in United Trading

Corporation S.A. y. Allied Arab Bank Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lloyd’s

Rep. 554 as to the nature and quality of the evidence required to

satisfy the court that an injunction of that sort should be granted;

(6) in granting the injunction the judge had misdirected himself and

thereby exercised his discretion on erroneous grounds in that he had

applied principles and proceeded on grounds appropriate to the grant of

a Mareva injunction but irrelevant to the question whether or not he

should have granted the injunction which he had granted; and (7) in so

far as the judge had placed reliance upon the decision in Elian and

87

QB. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.)

Rabbath v. Matsas [1966] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 495, he had been wrong to do

so as (i) that case was distinguishable on its facts, and (ji) that case was

an exceptional case and was wholly inconsistent with subsequent

authorities governing the grant or refusal of injunctions of the type

granted in the case.

The facts are stated in the judgment of Waite L.J.

Michael Ashe Q.C. and Michael Roberts for the first and second

defendants. The judge was wrong in law in holding that he had power to

grant an injunction without proof of fraud between the defendants and

the guarantors and/or where the guarantors were not a party to the

proceedings. In coming to that conclusion the judge effectively applied the

argument which was rejected by the Court of Appeal in Bolivinter Oil S.A

v, Chase Manhattan Bank N.A. (Practice Note) [1984] 1 W.L.R. 392 and

in United Trading Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab Bank Ltd, (Note) (1985]

2 Lloyd’s Rep. 554 as to the nature and quality of the evidence required

to satisfy the court that such an injunction should be granted. In so far as

the judge placed reliance on Elian and Rabbath v. Matsas (1966] 2 Lloyd’s

Rep. 495 he was wrong to do so since that case is distinguishable on its

facts and is inconsistent with subsequent authorities governing the grant

of injunctions in such cases.

‘The relevant principles are set out in Jack, Documentary Credits, 2nd

ed. (1993), pp. 219-226, paras. 9.27-9.34. There is no practical distinction

between letters of credit and performance bonds or guarantees. The

overriding principle is the “autonomy rule:” see Howe Richardson Scale

Co. Ltd. v. Polimex-Cekop [1978] 1 Lloyd’s Rep. 161, 165 and Bolivinter

Oil S.A. v. Chase Manhattan Bank N.A. (Practice Note) [1984] 1 W.L.R.

392, 393. Performance guarantees are virtually promissory notes payable

on demand. The purpose of such guarantees is to protect a vendor from

being prejudiced by claims raised by a buyer: see Bolivinter Oil S.A. v.

Chase Manhattan Bank N.A. (Practice Note) [1984] 1 W.L.R. 392, 393.

The buyer takes the risk of the unconditional terms under which the

guarantees are given: see Edward Owen Engineering Ltd. v. Barclays Bank

International Ltd. (1978] Q.B. 159, 171, 172, 174.

To succeed an applicant must prove fraud on the part of the beneficiary

and to the knowledge of the paying bank. The strictness of this

requirement is the corollary of the autonomy rule from which there should

be no derogation. The fraud must be in the calling down of the credit.

The beneficiary must be dishonest in his approach to the paying bank: see

United City Merchants (Investments) Ltd. v. Royal Bank of Canada [1983]

1 A.C. 168, 183.

Kenneth Craig for the plaintiffs. There are exceptions to the general

rule that courts will not interfere with an autonomous, free-standing

guarantee on the application of a person not a party to the contract: see

Elian and Rabbath v. Matsas [1966] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 495, 497, 498. The

correct test is set out in United Trading Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab

Bank Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lioyd’s Rep. 554, 561. If established the court

must then consider the balance of convenience: see American Cyanamid

Co. v. Ethicon Ltd. [1975] A.C. 396.

88

Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996)

An appellate court is only entitled to interfere with an order made in

the exercise of a judge’s discretion where it is plainly wrong: see Bellenden

(formerly Satterthwaite) v. Satterthwaite [1948] | All E.R. 343, 345 and

G. v. G. (Minors: Custody Appeal) [1985] 1 W.L.R. 647, 651, 652.

Where there is an overwhelming inference that a contract, the

performance of which was secured by bankers’ guarantees, was induced

by fraudulent misrepresentations to an innocent party, equity can intervene

to protect that party from suffering an irretrievable injustice.

‘Ashe Q.C. replied.

The third defendant did not appear and was not represented.

Cur. adv. vult.

6 April. The following judgments were handed down.

Warre L.J. This appeal arises from a dispute between the buyers

and the sellers of a business. Under the contract of sale the purchase price

of £1,600,000 was payable as to £100,000 on completion and as to the

balance by subsequent instalments at stipulated dates. The third, and

largest, instalment was secured, up to a limit of £775,000, by a performance

guarantee obtained from a third party. In the évent of default by the

buyers the sellers were entitled to give notice to the guarantors to make

good the default up to the limit of the guarantee. If that happened, the

guarantors would be entitled to be indemnified by the buyers. At a stage

when only the first of the deferred instalments of the purchase price had

been paid and the bulk of it was still outstanding, the buyers started

proceedings for rescission of the contract and damages on the ground of

alleged fraudulent misrepresentation by the sellers. The nature of the

alleged fraud was concealment. There had been included in the profit

projections on which the purchase price was negotiated an assumption

that demand from a major customer of the business would continue,

though not necessarily at the same high level. The buyers alleged that the

sellers had become aware by the date of execution of the agreement that

there was no longer any basis for that assumption, because the customer

had decided to order all future supplies of the relevant product from a

competitor of the sellers. The sellers denied misrepresentation and insisted

upon their right to treat the buyers as being in default and to give notice

to the guarantors to enforce the guarantee. The buyers applied in the

proceedings, to which the guarantors were not a party, for an interlocutory

injunction to restrain the sellers from giving notice to the guarantors until

the trial of the action. On 11 June 1993 Mr. Maurice Kay Q.C,, sitting as

a deputy High Court judge in the Queen’s Bench Division, granted the

injunction. He did so upon the basis that he was satisfied that the evidence

was sufficient to raise a seriously arguable case at trial that the only

reasonable inference which could be drawn from the circumstances was

that the sellers were fraudulent. From that order the sellers now appeal to

89

QB. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Waite LJ.

this court. They contend firstly, that the grant of an injunction to restrain

the giving of notice was wrong in principle because it offended the status

of autonomy which the law accords to performance guarantees; secondly,

that in any event the evidence was insufficient to give rise to the arguable

case of fraud on which the injunction was founded; and thirdly that even

if, contrary to those contentions, there was jurisdiction to grant such an

injunction, the judge ought to have refused it on the ground that an

injunction was an unnecessary and/or excessive form of relief in the

particular circumstances.

The legal background

It will be convenient to consider this under two heads.

(a) Where at the date of the application there has already been a claim

under the guarantee by the beneficiary

If there has been a default by a party to the main contract in making

payment to the other party of a sum due under the contract of which

payment has been guaranteed by a third party, and the guarantor has

been called upon to make payment under the guarantee, in circumstances

which will entitle it to indemnity from the party in default, the principles

on which the court will act in dealing with an application by the party in

alleged default for an injunction to restrain the bank from paying over the

guaranteed sum to the beneficiary are well settled.

(1) Letters of credit, performance bonds and guarantees are all subject

to the general principle that they must be treated as autonomous contracts,

whose operation is not to be interfered with by the court on grounds

extraneous to the credit or guarantee itself: see Jack, Documentary Credits,

2nd ed. (1993), pp. 220-226, paras. 9.28-9.34 and the cases there cited of

Hamzeh Malas & Sons v. British Imex Industries Ltd. [1958] 2Q.B. 127;

Howe Richardson Scale Co. Ltd. v. Polimex-Cekop [1978] 1 Lloyd’s Rep.

161 and R. D. Harbottle (Mercantile) Ltd. v. National Westminster Bank

Ltd. [1978] Q.B. 146.

(2) The sole exception allowed to this principle is for instances of

fraud, although even in such instances the law recognises the prima facie

right of the guarantor to be the sole arbiter on the question whether

payment under the guarantee should be refused on the ground of fraud:

see United City Merchants (Investments) Ltd. v. Royal Bank of Canada

[1983] | A.C. 168 where Lord Diplock, speaking of a documentary credit,

said, at p. 183:

“the parties to it, the seller and the confirming bank, ‘deal in

documents and not in goods’ ... If, on their face, the documents

presented to the confirming bank by the seller conform with the

requirements of the credit as notified to him by the confirming bank,

that bank is under a contractual obligation to the seller to honour the

credit, notwithstanding that the bank has knowledge that the seller at

the time of presentation of the conforming documents is alleged by

the buyer to have, and in fact has already, committed a breach of his

contract with the buyer for the sale of the goods to which the

documents appear on their fact to relate, that would have entitled the

Q.B. 1996--5

90

Waite LJ. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) (1996)

buyer to treat the contract of sale as rescinded and to reject the goods

and refuse to pay the seller the purchase price. The whole commercial

purpose for which the system of confirmed irrevocable documentary

credits has been developed in international trade is to give the seller

an assured right to be paid before he parts with control of the goods

that does not permit of any dispute with the buyer as to the

performance of the contract of sale being used as a ground for non-

payment or reduction or deferment of payment. To this general

statement of principle as to the contractual obligations of the

confirming bank to the seller, there is one established exception: that

is, where the seller, for the purpose of drawing on the credit,

fraudulently presents to the confirming bank documents that contain,

expressly or by implication, material representations of fact that to

his knowledge are untrue.”

(3) Independently of the right of the guarantor to refuse payment on

the ground of fraud, a performing party may apply for an injunction to

restrain enforcement of a performance guarantee by the beneficiary if he

can prove fraud on the part of the beneficiary of which the guarantor has

knowledge: see Edward Owen Engineering Ltd. v. Barclays Bank

International Ltd. [1978] Q.B. 159; Bolivinter Oil S.A. v. Chase Manhattan

Bank N.A. (Practice Note) [1984] 1 W.L.R. 392 and United Trading

Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab Bank Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.

554,

(4) The standard of proof required of an applicant seeking to bring

himself within the exception in (3) was stated in the United Trading case.

That involved a case where the impugned party and beneficiary under the

performance guarantee was a buyer, not as in this case the seller, but the

test was plainly intended to be of general application. Ackner L.J. stated

it, at p. 561:

“The evidence of fraud must be clear, both as to the fact of fraud

and as to the (guarantor’s] knowledge. The mere assertion or

allegation of fraud would not be sufficient”—citing Bolivinter Oil S.A

v. Chase Manhattan Bank N.A. (Practice Note) [1984] 1 W.L.R.

392—“. .. We would expect the court to require strong corroborative

evidence of the allegation, usually in the form of contemporary

documents, particularly those emanating from the buyer. In general,

for the evidence of fraud to be clear, we would also expect the buyer

to have been given an opportunity to answer the allegation and to

have failed to provide any, or any adequate answer in circumstances

where one could properly be expected. If the court considers that on

the material before it the only realistic inference to draw is that of

fraud, then the seller would have made out a sufficient case of fraud.”

(b) Cases where a default has occurred but the beneficiary has not yet

claimed under the guarantee

There is no authority stating the principles to be applied when, as in

this case, the party in default under the main contract seeks, without

involving the guarantor in the proceedings at all, to restrain the beneficiary

91

QB. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Waite L.J.

from taking any step to enforce the performance guarantee. The judge

regarded the authorities under (a) above as applying by analogy. He held

that he had jurisdiction to grant the injunction, provided he was satisfied

that the buyers established an arguable case that fraud by the sellers is the

only realistic inference that can be drawn; he concluded that they had,

and he granted the injunction.

The facts

1. The background

The appellant defendants (“the sellers”) owned the share capital of

Lawgra (No. 153) Ltd. (“Lawgra”) a company which owned the trading

assets of an unincorporated business known as Shinecrest Engineering

(“Shinecrest”). The main business activity of Shinecrest was the

manufacture of stands for television sets. The defendants sought offers for

the purchase of the Lawgra share capital, for which purpose an

information memorandum was prepared by Price Waterhouse for

prospective purchasers in which it was stated that Shinecrest’s principal

customers were Sony (U.K.) Ltd. (“Sony”), Sony’s associated company in

Germany, Mitsubishi and Amstrad. Sony had been a customer for seven

years, and Shinecrest had been its exclusive supplier of television stands

for the last two years. At that date Shinecrest principally supplied to Sony

six models of stands, namely those numbered M214-SU305, M252-SU30S,

SU301, SUX31, E25, and E29. Sony’s demand for such models was

notified by means of forecasts supplied to Shinecrest on a monthly basis

giving particulars of anticipated demand for the period of some

10 months or so ahead. These will be referred to hereafter as “the monthly

forecasts.”

2. The pre-contract events

On the basis of the contents of the information memorandum the

plaintiffs Themehelp Ltd. (“the buyers”) entered into negotiations for the

acquisition of the share capital of Lawgra. While those negotiations were

proceeding the following events occurred. (1) On 17 December 1991

Mr. Richards of Sony sent a fax to Mr. West, one of the sellers, in these

terms:

“Subject: TV Stand Line up for 1992

“Due to new model introductions and related T.V. stand design

changes, existing stands will discontinue as follows:—{there then

followed drastically reduced demand figures for various models, and

a nil demand for one of them, with effect from April 1992,)”

(2), On 19 December 1991 Mr. West wrote to Mr. Powlesland, the

manager of Sony’s purchasing department, as follows:

“You would obviously be aware of the news that Paul [Richards]

related to me on Tuesday morning of this week regarding the virtual

conclusion of trade between Sony (U.K.) Ltd. and Shinecrest. I’m

sure you are conscious that Sony are our largest account by value of

sales. The percentage of our total sales to you is extremely large and

as such the decision of your company is extremely damaging. The

92

Waite LJ. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996}

‘right to choose’ a supplier I would not question. However I do feel

the apparent circumstances of the change of supplier would not

appear to be in line with the generally understood Sony philosophy

regarding the working relationship between customer and supplier.

Shinecrest commenced trading with Sony (U.K.) Ltd. in October

1985. At this time our company turnover was circa £500,000. During

the following six years we have shown a slightly erratic, but sustained

growth. What is conspicuous is the ever increasing spend by Sony

with Shinecrest. I believe it is also worth highlighting one other aspect

of the six years trading. With such a record of increased spend I feel

we should be able to feel confident that our performance is

satisfactory. Thus to find that for 1992-1993 T.V. stand requirements

we were not considered is very hard to accept. Surely we are right to

believe that as you roughly double each year the spend with us for

four or five years you are pleased. Please may I ask why I was not

considered for any of the future SU 301 T.V. stand business? The

implications for our company with the loss of this business are not

good. We do expect there to be a downturn in trade after Christmas

but such is the magnitude now it is inevitable that we shall be obliged

to reduce our staffing level. It is not possible to say yet how ‘many

and when.’ I shall advise in January. At this time it is very difficult

not to remember your strong suggestion that our company should

consider relocation to Bridgend so that we may be close to Sony.

Paul! too has said the same thing quite a few times during the past

year. To conclude I would obviously welcome intervention by yourself

that might allow us to compete for the SU-301 business of 1992,

however little, however late.”

To illustrate the point made in this letter, Mr. West incorporated figures

showing that Shinecrest’s turnover had increased between March 1986 and

March 1991 from £0:5m. to £3-Om. and that the Sony contribution to that

turnover had increased in the same period from one per cent. to 54 per

cent. (3) On 20 December 1991 Mr. Powlesland replied:

“Have noted your comments and supporting statistics. We will be

taking the issue further with senior managers of respective controlling

bodies in early January. In the meantime I would personally like to

extend my thanks for your continued support this year and (as you)

hope a more satisfactory conclusion can be reached to this matter.”

(4) On 15 January 1992 Price Waterhouse acting on the:instructions of

the sellers produced a supplement to the information memorandum on

Shinecrest, which was supplied to the buyers. It read, so far as relevant:

“Sony (U.K.) Limited

“In the information memorandum on Shinecrest it is explained

that Shinecrest has been the sole supplier of T.V. stands to Sony

(U.K.) for the last two years and has had a relationship with Sony

(U.K.) for the last seven years. In its relationship with Sony,

Shinecrest sells to Sony Bridgend, where Sony manufactures televisions

in the U.K. Sony Staines is the sales company for Sony in the U.K.

and it effectively buys Bridgend’s televisions and the T.V. stands

93

QB. Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Waite LJ.

which it then sells on. Shinecrest manufactures three classes of T.V.

stands for Sony, being a low price (LP) model; mid price (MP)

model; and high price (HP) model. On Tuesday 17 December 1991,

Ray West of Shinecrest received a telephone call from the purchasing

officer for Sony Bridgend and was told that Sony Staines had

informed Sony Bridgend that during 1992 they intended to commence

buying MP T.V. stands direct, rather than via Bridgend, and that the

supplier would not be Shinecrest; Sony Staines would continue to buy

Shinecrest’s HP model via Bridgend and a decision had been taken

by Sony Staines that they wanted a die cast LP stand rather than a

fabricated steel tube stand. Shinecrest do not produce die cast stands

and so this business has been placed with another company.

“Sony Staines organised a line-up meeting at Staines on

5 November 1991 at which it invited certain companies to put forward

their T.V. stand designs for Sony’s new 1992 range of televisions.

Bridgend were asked to put forward design concepts for a die cast LP

stand, but were not asked to put forward such concepts for a MP

stand. Thus Bridgend were not aware that a future alternative

sourcing of the MP stand was being considered by Staines. Indeed on

19 November 1991, the Bridgend purchasing officer asked for

Shinecrest to visit Bridgend for a meeting on 25 November 1991, the

same day as the line-up meeting. The purpose of this meeting was to

talk about Shinecrest’s MP stand designs for 1992.

“It is believed that Shinecrest was not invited to the line-up

because Staines wanted to go its own way in sourcing the MP T.V.

stands for internal reasons and was aware of Shinecrest’s strong

relationship with Bridgend. The result of this is that the production

of the MP stand has initially been placed with a competitor.

Correspondence from the Bridgend senior purchasing officer has

indicated the degree of ill—will now generated between Bridgend and

Staines. The matter is being taken up at the senior management level

of the respective operations and Shinecrest was asked on 19 December

1991 to prepare a resume of the business conducted between

Shinecrest and Sony to assist the Bridgend individuals in discussion

with Staines. As a result of Bridgend’s efforts on Shinecrest’s behalf

it is anticipated by Shinecrest that Sony will now dual source the MP

stand, and that Shinecrest will initially be asked to supply 50 per cent.

of the MP T.V. stands in 1992/93.”

Conclusion

“Shinecrest has thus endured, through what appear to be internal

factors within Sony (U.K.), rather than as a result of any

dissatisfaction with Shinecrest’s products, a reduction in turnover to

Sony (U.K.). This was unforeseeable but by the same token, is a

situation which is unlikely to recur. This is evidenced by the fact that

it is anticipated that at least part of the lost turnover will be replaced

by sales to Sony Germany. A revised turnover forecast for year ended

31 August 1992 is attached.”

The attachment showed sales projections to Sony diminishing from

£130,000 in January 1992 to £7,000 in May 1992 but increasing in June,

94

Waite LJ. ‘Themehelp Ltd, v. West (C.A.) 11996]

July and August 1992 to £42,000, £52,000 and £58,000, but with an

asterisk against those last three figures indicating that “this assumes the

recovery of 5,000 p.m. of the mid range stand @ £8 each.”

(5) Mr. Evans, the director of the buyers responsible for the negotiations,

wanted direct reassurance from Sony as to the anticipated continuance of

their custom. He pressed the sellers to appoint a meeting with an

appropriate Sony representative. Mr. West arranged a meeting on | April

1992 at Sony’s head office at Staines with a Sony representative Mr. Rose.

It was attended by Mr. Evans and Mr. West. Mr. Rose said that tooling

for the new medium-priced S stand had been placed with a competitor of

Shinecrest, but he was willing to discuss the possibility that Shinecrest

would obtain orders for the manufacture of some part of Sony’s

requirement for such stands. The meeting was cordial and concluded with

Mr. Rose’s compliments on past performance and his anticipation of a

long business future with Shinecrest. The buyers assert that the meeting

with Mr. Rose was arranged by the sellers as part of a devious stratagem

to conceal from the buyers the fact that Sony’s future requirements for an

S stand would be nil. The sellers were perfectly well aware, it is claimed,

that by the date of this meeting the decision to curtail demand had already

been taken firmly by Mr. Powlesland at Bridgend, they were also aware

that Mr. Rose was out of touch with developments at Bridgend, and they

accordingly arranged the Staines meeting with Mr. Rose, rather than

placing it at Bridgend, with a view to exploiting the ignorance of Sony’s

left hand at Staines as to what its right hand was doing at Bridgend.

(6) On 27 April 1992 there was a meeting between Mr. West and

Mr. Evans of the buyers to discuss the purchase price for the Shinecrest

business. The discussion proceeded upon the basis of a profit projection

calculated by reference to the figures in Sony’s monthly forecast for the

month of February 1992. In regard to anticipated future sales to Sony

Mr. West told Mr. Evans that there was a good probability that the new S

model stand would be dual-sourced by Sony and that Shinecrest had a

very good chance of obtaining that order. It is common ground that the

discussion concluded with an agreed calculation that current sales

projections would produce a total sales figure for Shinecrest of £4m.,

leading to an anticipated profit of £500,000. In their pleading, however,

the sellers assert that Mr. West's assent to that calculation was directed

solely to its mathematical accuracy and involved no element of

representation as to the projections on which it was founded. (7) At no

stage before the contract was any disclosure made to the buyers by the

sellers of the documents in (1) (2) and (3) above (“the December

correspondence”).

3. The contract and the guarantee

On 29 May 1992 two documents were executed as follows. (1) By a

written contract (“the contract”) made between the sellers and the buyers

it was agreed that the buyers would buy from the sellers the 2,210 ordinary

shares of Lawgra for the sum of £104,731 payable upon completion of the

contract which was due to take place, as it did, on the date of the contract.

Put and call options for the purchase and sale of the 107,800 redeemable

non-voting deferred shares of the company were granted and made

95

QB. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Waite LJ.

exercisable according to the terms of clause 6 of the schedule | to the

contract.

They were exercisable serially by instalments on specified dates. It was

an express term of the contract that a duly executed unconditional

guarantee from the guarantors should be provided by the buyers at

completion covering the consideration for the third option instalment. The

contract included warranties by the sellers in common form, including a

warranty that (i) there had been no deterioration in the turnover of the

financial or trading position or prospects of Shinecrest since the last

accounts date in August 1991; and (ii) so far as the sellers were aware no

material source of supply to Shinecrest or any material outlet for the sales

of Shinecrest was in jeopardy. Incorporated into the contract was a

disclosure letter of the same date, which included provisions (i) that:

“information provided direct by Sony and Mitsubishi at meetings

held with those customers attended by the [buyers’] representatives,

including information as to likely future customer relationships and

anticipated product demand were deemed to have been disclosed;

(ii) [the sellers] are involved in contracts with Sony U.K., Sony

Deutchland, Mitsubishi and Amstrad all of which exceed £270,000.

The [sellers] have already disclosed the relevant order books, sale

qualities, unit prices and budgetary forecasts to the [buyers] and

accordingly [the buyers are] deemed to have all information relevant

to the size of the purchases by these customers.”

(2) By two deeds of guarantee (“the guarantee”) made between the

sellers, other than the third defendant, and 3i Group Plc. in the one case

and Midland Montagu Investment Ltd. in the other ("the guarantors”) it

was agreed, after reciting the contract and the fact that under its terms the

sellers would become entitled at the exercise of the third instalment option

to receive an aggregate consideration of £775,000 (therein called “the

guaranteed amount”), that in consideration of the sellers entering into the

contract: (i) the guarantors irrevocably guaranteed to the sellers that if on

the date for completion of the third option the buyers defaulted in

payment of the guaranteed amount the guarantors would upon receipt by

the guarantors of notice from the sellers of such failure pay the guaranteed

amount to the sellers; (ii) liability under the guarantee would cease on

30 September 1993.

4, Events following completion

(1) The buyers, having made inquiry of Sony, learned for the first time

of the December correspondence which was not to be found anywhere in

the files of the Shinecrest business supplied to them upon completion of

the contract by the sellers. (2) Nor were Sony’s monthly forecasts for the

months of March and April 1992, which showed an acute down-turn in

Sony’s demand for Shinecrest stands, to be found in those files. There is

an issue on the pleadings as to whether those forecasts had been supplied

by Sony to the sellers before execution of the contract. In his evidence in

support of the application, the buyers’ solicitor Mr. Palmer deposed to a

meeting with Sony’s representatives at which he, Mr. Palmer, had been

informed that the March and April monthly forecasts had been sent by

96

Waite LJ. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v, West (C.A.) 11996]

Sony to the buyers well before the date of the contract; and that although

it could not be said for certain that the May monthly forecast had reached

them before the contract date, the information contained in it would have

been readily available on inquiry. (3) On 2 March 1993 the buyers, who

by that date had paid the first two instalments under the contract

amounting to £50,000 but refused to pay the third option payment covered

by the guarantee, issued the writ in the action indorsed with a statement

of claim alleging that the sellers had fraudulently suppressed details of the

downturn in demand from Sony and had made false representations as to

its expected continuance, and claiming rescission and/or damages for

misrepresentation. (4) On II June 1993 the judge heard the buyers’

application for an injunction to prevent the sellers from giving notice to

the guarantors of default in the payment of the third option tranche, and

granted it, subject to confirmation, which has been duly given, from the

guarantors that they would not enforce the time limit for the guarantee

due to expire on 30 September 1993 but extend it until after the conclusion

of these proceedings and any appeal.

The hearing below

(1) The material before the judge consisted of the pleadings, whose

gist I have already summarised, copies of relevant documents, including

the December correspondence and the monthly forecasts, and affidavits

from Mr. Palmer and Mr. West. In his affidavit Mr. West dealt with the

absence from the files of the December correspondence by asserting simply

that: “I did not remove the December correspondence from Shinecrest’s

files.” His answer to Mr. Palmer's report of the information he had

received from Sony that the monthly forecasts for March and April had

been duly dispatched well before the contract date, and his evidence that

no copy of those forecasts was to be found in the files was: “I did not see

or receive Sony Budget Forecasts dated March and April 1992 and

Mr. Palmer does not put forward any clear or direct evidence that they

were either sent or received.” His response to Mr. Palmer’s claim that,

even if the May monthly forecast was not received before the date of the

contract, the sellers ought to have obtained up to date information from

Sony regarding that forecast before entering into the contract, was limited

to an assertion that it amounted to: “no more than an improper exercise

in guilt by innuendo or implication.” Mr. West refuted the suggestion that

in arranging the meeting with Mr. Rose he had directed Mr Evans to the

wrong person, and denied that Mr. Rose was not qualified to give a view

on the future of the trading relationship.

(2) It was common ground before the judge that the sellers, effectively

for present purposes the first and second defendants, are resident outside

the jurisdiction in Portugal. Mr. West’s affidavit stated that they are

building a house there and intend to reside there permanently; they have

a property in England which is at present on the market.

The judgment below

(1) The judge referred to the authorities I have already mentioned,

with the addition of Elian & Rabbath v, Matsas [1966] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 495.

97

QB. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Waite L.J.

He commented that they all related to instances where the guarantor was

joined as a party to the injunction application, and the relief sought was a

restraint upon payment by the guarantor to the beneficiary. The present

case was exceptional, in that here the relief was sought at an earlier stage,

that is to say a restraint against the beneficiary alone in proceedings to

which the guarantor is not a party, to prevent the exercise by the

beneficiary of his power to enforce the guarantee by giving notice of

the other party’s alleged default in discharging the liability which was the

subject-matter of the guarantee. Before him, as before this court, it was

common ground that there is no authority deciding whether an application

of that nature is one which the court has power to grant by law, and if so

what principles should be applied to it.

(2) He took the view that this was an analogous case to those in which

relief is sought, after a claim has been made by the beneficiary, against the

guarantor as well as the beneficiary, and is subject to the same principle

that the court will only interfere with the autonomy of a performance

contract in the exceptional instance where the applicant establishes a

prima facie case of fraud. He said:

“I have come to the conclusion that where, as here, the issue falls to

be decided simply between buyer and seller where no demand has yet

been made on the banks and where the banks are not parties to this

action, I have the power to grant an injunction to restrain the making

of the demands without proof of fraud as between the defendant and

the banks. I also observe that in Elian and Rabbath v. Matsas [1966]

2 Lloyd’s Rep. 495 there was no evidence of fraud in the beneficiary's

dealing with the bank. That case may well illustrate the exceptional

rather than the usual, but although referred to in most of the

subsequent cases no one has ventured to suggest it is no longer good

law.”

(3) He held that the standard of proof of fraud should, again, by

analogy, be the same, i.e. the establishment of an arguable prospect of

satisfying the court at trial that the only realistic inference to draw is that

of fraud.

(4) The judge proceeded, after reciting the contentions of the parties,

to apply that test with a result which he stated in these terms:

“if I have to ask myself the question, drawing on the words of

Ackner L.J. in United Trading Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab Bank

Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 554, 561, has the plaintiff

established that it is seriously arguable that on the material available

the only reasonable inference is that the defendants were fraudulent

in relation to the share sale agreement, the answer, in my judgment,

is that the plaintiff has so established. I am not, of course, finally

deciding the matter and I appreciate that the defendants are

strenuously denying fraud, but it is, in my judgment, seriously

arguable that on the material presently available fraud is the only

reasonable inference.”

Although he did not in that passage specify which particular aspects

of the evidence he regarded as sufficient or insufficient to justify an

98

Waite L.J. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996]

inference of fraud, he has not been criticised on appeal for any insufficiency

in the statement of his reasons, and the appellant has been content to

attack his conclusion on the basis that the evidence as a whole was

inadequate to justify the judge’s conclusion.

The argument on appeal

(a) Was the remedy of an injunction available at all for the purpose

proposed?

Mr. Ashe for the sellers contends firstly that the judge erred in law in

regarding it as open to the court to grant the injunction sought. Although

the contract and the guarantee were interdependent in the sense that this

was a tripartite transaction involving the buyers, the sellers and the

guarantors, they were separate transactions. The guarantee was a wholly

independent bargain enjoying autonomy under the principle affirmed by

the House of Lords in United City Merchants (Investments) Ltd. v. Royal

Bank of Canada [1983] 1 A.C. 168. When the autonomy there claimed for

performance guarantees and other documentary credits is applied to the

present case, Mr. Ashe submits, the result is as follows. It is for the

guarantors, not for the court, to determine whether the case is one to

which the exception for fraud applies. If the sellers had served notice on

the guarantors claiming payment under the guarantee following a default

by the buyers, it would have been the exclusive right and duty of the

guarantors to decide whether, on the face of the notice or by implication

from what they know about the circumstances in which it has been served,

to comply with the notice or to reject it on the ground of fraud. The only

exception to that right which the law tolerates is the case where after a

demand has been made by the beneficiary the other party may apply in

proceedings against both the guarantor and the beneficiary for an order

restraining the guarantor from paying the beneficiary on the ground of the

latter’s fraud. To allow the other party to apply against the beneficiary

alone at the preliminary stage, before any notice has yet been served under

the guarantee, to restrain the service of notice altogether on the ground of

fraud alleged solely as between the buyers and the sellers would be to

deprive the guarantor of the right which the law accords to it of appraising

the element of fraud for itself. That is an unwarranted invasion of the

integrity of a performance guarantee, and would, if allowed, open the way

to similar invasions of autonomy in other cases.

This argument, with respect to the skill with which it was presented

and to the impressive support it has received from Evans L.J., whose

views I have had an opportunity of reading in draft, is in my view

mistaken. It amounts, in summary, to a contention that the very limited

exception which, in cases where a demand has been made under the

guarantee, the law allows to the autonomy of a performance guarantee by

permitting the other party to the main transaction to sue both the

beneficiary and the guarantor for an injunction restraining payment under

the guarantee is an exception which should not be extended any further.

The assumption upon which this argument proceeds is that the autonomy

of a performance guarantee is threatened if the beneficiary is placed under

a temporary restraint from enforcing it. That is not an assumption,

however, which appears to me to have any validity. In a case where fraud

99

QB. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Waite L.J.

is raised as between the parties to the main transaction at an early stage,

before any question of the enforcement of the guarantee, as between the

beneficiary and the guarantor, has yet arisen at all, it does not seem to me

that the slightest threat is involved to the autonomy of the performance

guarantee if the beneficiary is injuncted from enforcing it in proceedings

to which the guarantor is not a party. One can imagine, certainly,

circumstances where the guarantor might feel moved to express alarm, or

even resentment, if the buyer should obtain, in proceedings to which the

guarantor is not a party, injunctive relief placing a restriction on the

beneficiary’s rights of enforcement. But in truth the guarantor has nothing

to fear. There is no risk to the integrity of the performance guarantee, and

therefore no occasion for involving the guarantor at that stage in any

question as to whether or not fraud is established. It amounts to no more,

in the last analysis, than an instance of equity intervening to restrain the

beneficiary, until the day when his conscience stands trial at the main

hearing, from enforcement of his legal rights against a third party. Some

support for this view may, I think, be found in Andrews & Millett, The

Law of Guarantees (1992), at p. 421. Since this is a case where fraud is the

sole ground relied on by the party secking the injunction, I do not find it

necessary to consider whether the principle extends beyond instances of

fraud to cases where the beneficiary under the guarantee is alleged to be

in non-fraudulent breach of the main contract.

The judge was accordingly right, in my view, to hold that he had

jurisdiction to entertain the application for the injunction sought.

(b) Was the judge entitled on the evidence to find a prima facie case of

fraud established?

It is unnecessary for the purposes of this appeal to decide whether the

“sole realistic inference” test propounded by Ackner L.J. in United Trading

Corporation S.A. v. Allied Arab Bank Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lloyd’s Rep.

554 involves a more burdensome standard of proof than the standard

generally applied to proof of fraud, namely that fraud must be established

on the balance of probabilities after weighing the evidence with due regard

to the gravity of the particular allegation; or to decide whether the judge

was right to have treated the former test, rather than the latter, as applying

in this case. That is because Mr. Craig for the buyers has not sought to

argue in this appeal, though he would reserve the right to do so in another

case, that the judge adopted too stringent a test of fraud.

Mr. Ashe submitted that the evidence fell a long way short of

establishing fraud to that standard. The alleged fraud consists of a

deliberate or reckless failure on the part of the sellers to inform the buyers

of the full extent of the falling-off of future demand from Sony of which

they were aware by the date of the contract and of which, to their

knowledge, the buyers were not aware. How, asks Mr. Ashe, could a

fraud of that nature even begin to qualify for description as “the sole

realistic inference” in a case where the January update had contained a

very clear warning that Sony had undergone a change of buying policy

which would be bound to affect future demand, and where the buyers had

been provided with an opportunity of hearing a full account of Sony’s

future buying policy directly from Sony’s own management?

100

Waite L.J. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996]

Crucial to the answer to that question is the point of time at which it

is posed. At the date of the January update the sellers may well have had

grounds for genuine belief that Sony’s heart could be softened to the point

of maintaining the limited demand which it projected. That degree of

optimism may still have been a live possibility when they arranged the

meeting with Mr. Rose on | April. But what genuine grounds did they

have for optimism by 27 April, the date of the meeting between Mr. West

and Mr. Evans, and during the crucial four weeks thereafter leading up to

the signing of the contract on 29 May? If they had by that stage received

the February and March monthly forecasts, they could have been left in

no doubt that all prospect of Sony relenting the stern decision announced

in the December correspondence had vanished. The buyers countered

Mr. West's denial that those monthly forecasts had ever been received

before the contract date with evidence, albeit at this stage hearsay evidence

only, from Sony that Mr. Powlesland’s office at Bridgend had sent them

to the sellers well before that date. There was evidence from the same

source that the figures for the May monthly forecast would have been

available for the sellers’ information if they had made inquiry immediately

before the date of the contract, even though the document containing

them might not by then have been actually dispatched or received. There

was credible evidence from the buyers that the December correspondence

was missing from the files supplied to them at completion, and Mr. West’s

brief explanation, “I did not remove them,” invites more questions than it

answers,

The judge was entitled, in my judgment, to take all this into account

in reaching his conclusion that the buyers had satisfied the onus of

showing, for the purposes of interlocutory relief, that they had an arguable

case at trial that fraud was the only realistic inference. In his making of

that appraisal I cannot discern any error of principle or misappreciation

of the evidence on the judge’s part which would warrant interference by

this court with a conclusion that seems to me to have been fully open to

the court on the material at present available to it.

(c) The appropriateness of relief by way of injunction

Mr. Ashe’s final submission, assuming that contrary to his other

submissions an arguable case of fraud is established and that jurisdiction

to grant an injunction of the kind claimed in this case exists at all, was

that an injunction should be refused in the court’s discretion on the

ground that to grant it in such circumstances as these would be to give

the buyers relief going far beyond what was necessary to preserve their

rights pending trial, If they are to have injunctive relief at all, he says, let

it be limited to a Mareva order freezing the proceeds of payment under

the guarantee in the hands of the sellers until trial of the action.

Intervention to prohibit the sellers from claiming at all under the guarantee

until the trial of the action would amount, he claims, to giving the buyers

relief tantamount to attachment, which would be wholly inappropriate at

this interlocutory stage.

I am not impressed by that argument. If the sellers are allowed to

claim now under the guarantee, the guarantors will be entitled, by virtue

of their indemnity, to call for immediate recoupment by the buyers of the

101

QB. ‘Themehelp Ltd. y. West (C.A.) Waite LJ.

substantial sum, £775,000, which it secures. If the buyers succeed in

establishing fraud at the trial, they will only be able to recover that sum

in full if there are assets available to satisfy a judgment against the sellers

for an equivalent amount in damages for fraudulent misrepresentation,

this being a case where rescission is likely to prove wholly impracticable

and damages to be the only remedy. Bearing in mind that both defendants

are out of the jurisdiction, and that there is no evidence that they have

sufficient assets remaining in this country to satisfy any such judgment,

there must be an appreciable risk that it could not be wholly satisfied. If,

on the other hand, the buyers fail to establish fraud at trial, the sellers

will be fully protected by the continuing rights under the guarantee which

they will then be free to enforce; and if it be found that they have suffered

any damage as a result of having to delay enforcement, that will be

covered by the buyers’ undertaking in damages. There was evidence before

the judge that the buyers are a solvent concern with a turnover of £2m. It

seems to me, therefore, that justice to the buyers requires that they should

be spared the necessity of making a payment now of moneys which they

have only an uncertain prospect of recovering at trial, even if wholly

successful.

I would dismiss the appeal.

Evans L.J. (1) It is settled law that the holder of a bank’s written

undertaking to pay certain sums when specified conditions are met can

demand payment from the bank when those conditions are satisfied,

regardless of any contractual disputes which may have arisen between

himself and the bank’s customer, at whose request the undertaking was

issued. This is equally true of undertakings contained in letters of credit,

performance bonds and bank guarantees. The sole exception is in a case

of fraud, defined by Lord Diplock in United City Merchants (Investments)

Ltd. v. Royal Bank of Canada [1983] | A.C. 168, 183:

“where the seller, for the purpose of drawing on the credit,

fraudulently presents to the confirming bank documents that contain,

expressly or by implication, material representations of fact that to

his knowledge are untrue.”

(2) The standard of proof required of the bank’s customer if it secks

an interlocutory injunction to restrain payment by the bank is high,

though not so high as was contended in United Trading Corporation S.A.

v. Arab Allied Bank Ltd. (Note) [1985] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 554. The standard

was there defined, in accordance with the principles laid down in American

Cyanamid Co. v. Ethicon Ltd. [1975] A.C. 396, 561, in these terms:

“Have the plaintiffs established that it is seriously arguable that, on

the material available, the only realistic inference is that [the sellers}

could not honestly have believed in the validity of its demands on the

performance bonds?”

(3) In the present case, the bank guarantors have not been joined as

parties. The buyers contend that the share sale agreement (“‘S.S.A.”) under

which they purchased the sellers’ shareholdings in the Shinecrest business

was induced by fraudulent misrepresentation, that the S.S.A. therefore is

102

Evans LJ. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996}

voidable and that the sellers should be restrained from exercising their

rights under it pending trial, including the right to claim payment under

the bank guarantees.

(4) The judge found that “it is seriously arguable that on the material

available the only reasonable inference is that the defendants were

fraudulent in relation to the share sale agreement.” He expressly made no

finding, however, on the question whether there was fraud between the

sellers and the banks, and he rejected the submission on behalf of the

sellers that “even such a provisional finding is not enough to justify an

injunction because it does not encompass fraud in the calling down of the

credit.”

(5) Although the statement of claim includes in the prayer a formal

claim for rescission of the S.S.A., precedence is given in the pleading itself

to the claim for damages (paragraphs I1 and 13) and there is no allegation

that the buyers took any step to rescind or avoid the contract nor any

suggestion that the first tranche of shares and the business could or should

be restored to the sellers. It is not argued that the buyers are now entitled

to rescind the S.S.A., nor even that they were so entitled when the

injunction was granted in June 1993.

(6) In these circumstances, the S.S.A. is and will remain binding on

both parties. The buyers have taken over the business which they agreed

to pay for in accordance with its terms. Those terms included procuring

the bank guarantees which are now the subject matter of these

interlocutory proceedings, though not of the action in which they arise.

Unless the fraud exception applies, as to which no finding has been made,

the banks are liable to pay the sums due to the sellers under the S.S.A. In

my judgment, the buyers cannot prevent the sellers from recovering

payment of that sum without themselves acting unlawfully and in breach

of the S.S.A. itself. That is because they undertook that the sellers would

have the benefit of the guarantees in accordance with its terms, yet they

seek to resile from that undertaking. In my judgment, the court should

not permit them to do so.

(7) For these reasons, in my judgment, the injunction is contrary to

legal principle and the appeal should be allowed, In summary, the two

essential reasons are (i) the contract remains binding, even if the buyers’

allegation that they were induced to enter into it by fraudulent

misrepresentation by the sellers is sufficiently proved; and (ii) there is no

finding or evidence that fraud exception defence will be available to the

banks, if payment is demanded under the guarantees. Notwithstanding the

alleged fraud “in relation to” the S.S.A., once the contract is affirmed or

can no longer be avoided, the sellers are entitled to claim payment in

accordance with its terms. These include the set off provisions in clause 11

but these are less advantageous to the buyers, who do not rely upon them,

no doubt for that reason.

(8) Granting an injunction such as the present in these circumstances

is also harmful, in my judgment, to the integrity of the banking system

and to standards of commercial morality which the courts should uphold.

The reasons given by the buyer’s solicitor for seeking it are given in his

affidavit:

“T had assumed that the banks would resist any demand made by

the first and second defendants on the grounds of fraud, as they

103

QB. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Evans L.J.

would be entitled to do and certainly, on my instructions, the banks

have been very supportive of the plaintiff in this case. However, I was

informed by [the banks’ solicitors] that while the banks did not rule

out disputing the defendants’ right to these sums, on the grounds of

fraud as pleaded, the banks are reluctant to immediately allege fraud

based on the evidence of customers where the banks do not have first

hand knowledge of all the issues in dispute. Accordingly [they] could

not guarantee that the banks would take this point, although, as

Ihave indicated, it was certainly not ruled out and the banks will

continue to review the matter as it develops, with their solicitors.”

We were informed that there have in fact been close relations between

the buyers and their banks, through their respective solicitors, and that

these have continued. So the position is this. The banks have felt unable

or unwilling to rely upon the “fraud exception” defence. If they are

entitled to do so, no injunction against the sellers is necessary. The buyers

have attempted a pre-emptive strike which, if the injunction is granted,

relieves them of the need to decide whether to rescind their agreement or

not, thus retaining the business whilst disputing their liability to pay for

it, and which, if the court is concerned only with general allegations of

fraudulent misrepresentation “in relation to” the S.S.A., diverts attention

from the different question whether a demand for payment under the

guarantees would be fraudulent, or not. The commercial advantages-of

taking this alternative course for the bank and its customer are obvious.

If the injunction is granted, they obtain at least temporary relief from*the

bank’s obligation to pay in a situation where the bank cannot or may not

be able to rely upon its own “fraud exception” defence. A bank could

(I do not say that these banks have) encourage the customer to undertake

the lighter burden of proving merely that the underlying contract could

arguably be, or have been, rescinded, not necessarily for fraud. The

integrity of the bank’s separate undertaking in such a case would be

undermined.

(9) (i) The present case cries out for Mareva relief. This could extend,

if necessary, to requiring payment into court of whatever sums are due

from the banks: see United Norwest Co-operatives Ltd. v. Johnstone

(unreported), 6 December 1994; Court of Appeal (Civil Division)

Transcript No. 1482 of 1994. The buyers suggest that the sellers may have

other creditors and may be or become insolvent. That does not give them

a valid reason for withholding a payment which is otherwise due, and it is

no part of the Mareva jurisdiction to give priority over other creditors:

see Iragi Ministry of Defence v. Arcepey Shipping Co. S.A. [1981] Q.B. 65.

It is not sufficient, in my judgment, to consider whether the sellers or the

buyers should be out of pocket pending the trial. This is because there is

a binding contract between them, which requires the sums to be paid,

even in the circumstances which have arisen, subject to rights of set-off,

upon which the plaintiffs do not rely: compare Potton Homes Ltd. v.

Coleman Contractors Ltd. (1984) 28 B.L.R. 19. In my judgment, the

injunction is an unwarranted extension of the Mareva jurisdiction.

Gi) In my judgment, it is necessary to distinguish between cases where

the validity of the underlying contract is called in question and those

104

Evans L.J. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996]

where, for whatever reason, it is not. I would be prepared to agree that in

principle, if there was an arguable case that the contract was voidable or

otherwise invalid, then further performance of the contract might be

restrained pending the court’s resolution of that dispute. This would be

subject to possible complications such, as here, the time limit on the

operation of the guarantees. The clearest English authority in favour of

an injunction to this effect is Elian and Rabbath v. Matsas [1966] 2 Lloyd’s

Rep. 495 where the validity of the contract was disputed, though not

apparently on grounds of fraud: see Andrews & Millett, The Law of

Guarantees, at p. 423. This was later described by Roskill L.J. as “a very

special case” (see Howe Richardson Scale Co. Ltd. v. Polimex-Cekop [1978]

1 Lloyd’s Rep. 161, 165) and so it was, not least because attempts to

restrain the beneficiary rather than the bank/guarantor have been so rare.

The decision can also be regarded as an early example of the exercise of

the Mareva jurisdiction, 10 years before its time (see Elian and Rabath v.

Matsas [1966] 2 Lloyd’s Rep. 495, 498 where Danckwerts L.J. retired to

“an irretrievable injustice”). But, however that may be, the decision gives

no support to the proposition that the beneficiary can be restrained when

the validity of the contract, and therefore the beneficiary’s entitlement to

exercise his contractual rights, is no longer in issue.

(iii) The representation upon which the buyers rely was that the

forecast turnover for the year ending May 1993 was £4m., including

£980,000 sales to Sony which would continue at that same level thereafter

(statement of claim, paragraph 4) and that this would yield a profit of

£500,000 during that period. Since the buyers allege a misrepresentation

of fact, not of opinion, this must be taken to have amounted to a

representation that current, i.e. 27 April, forecasts were of those figures.

There is no evidence which shows what the actual figures were, apart from

the claim for £345,000 for loss of profits during the first year of trading:

statement of claim, paragraph 11, particulars. No breakdown of this figure

is given. Since the basis of the allegation that the representation was false

is the alleged shortfall on sales to Sony, this suggests that the expected

profit ratio was 345:980 which is greater than the ratio on which, it is

alleged, the purchase price was calculated and the claim is based. Even on

this basis, the claim is only justified if there were no sales to Sony in the

United Kingdom, and perhaps in Germany also, during the whole of the

twelve-month period, and that cannot be correct. In my judgment, there

is insufficient evidence to support the allegation that this representation

was untrue, and this matter was not dealt with by the judge.

(iv) There is no finding that the buyers were induced to enter into the

S.S.A. by the alleged misrepresentation. Such a finding is essential to the

right to avoid the 8.S.A.: see Halsbury's Laws of England, 4th ed., vol. 31

(1980), p. 649, para. 1066. On the evidence available, any such finding

would be unrealistic. The buyers purchased the sellers’ shareholdings in

the Shinecrest group of companies on terms negotiated over several

months and set out in the S.S.A. dated 29 May 1992. It is an elaborate

document, though apparently in common form. Both parties were

represented by experienced solicitors and each had access to financial

advisers (Price. Waterhouse for the sellers). The buyers were acting in

conjunction with their two bankers, 3i Group Plc. (“3i”) and Midland

105

QB. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) Evans LJ.

Montagu Investments Ltd., and Mr. Daniel of 3i accompanied Mr. Adrian

Evans, of the buyers, to all meetings with the sellers: except apparently a

visit which Mr. Evans made to the sellers on 27 April 1992 at which the

allegedly fraudulent misrepresentation was made. Moreover, in January

the buyers received Price Waterhouse’s “update” which included trading

and financial forecasts on the express assumption that the Sony U.K.

business would decline almost to zero. I find it difficult to accept that the

buyers, their bankers and advisers relied ultimately, even in part, on an

oral assurance given by the second defendant to Mr. Evans alone on

1 April or that Mr. Evans and Mr. Daniel, of 3i, who visited Sony’s

offices at Staines in order to establish the company’s trading prospects

with Sony, failed to discover either what the prospects were or that

Mr. Rose, the senior executive to whom they spoke, was not the

appropriate person within the Sony organisation for them to see, if such

was the case, without realising that they had not done so.

(v) There is a positive reason why no injunction should be granted in

the present case. The banks’ liability to respond under the guarantees is

limited to demands made within a certain time (by 30 September 1993).

The effect of the injunction was to prevent the sellers from making their

demands before that date. The buyers sought to overcome this difficulty

by offering an extension of time on behalf of the banks by virtue of

instructions obtained from the bank’s solicitor. This was a strange judicial

creature and was rejected, rightly in my view, by the judge. He therefore

gave the sellers “liberty to apply” if no agreed extension in writing was

obtained by 30 September. There was no such application and, presumably,

agreed extensions were obtained. In substance, therefore, the court has

imposed on the sellers a variation of their contracts of guarantee and has

deprived them for all time of the right to enforce the guarantees in

accordance with their terms. Such a variation would normally involve

charges by the banks, but there is no evidence as to what has occurred.

(10) I therefore would hold that the injunction granted in this case is

unjustified both generally as a matter of principle and in the circumstances

of this particular case. I would allow the appeal.

Batcompe LJ. The facts are fully set out in the judgment of

Waite L.J. and I need not repeat them. The following issues arise on this

appeal. (1) Was there evidence which entitled the judge to find that the

buyers had established that it was seriously arguabie that on the material

available the only reasonable inference was that the sellers were fraudulent

in relation to the share sale agreement? (2) If so, what are the legal

consequences of that fraud, if established, as between the buyers and the

sellers? (3) Is there any legal principle which precluded the judge from

granting an interlocutory injunction to restrain the sellers from giving

notice to the guarantors requiring payment under the guarantees pending

the trial of the action? (4) If not, is there any basis upon which this court

should interfere with the exercise by the judge of his discretion in granting

the interlocutory injunction? I consider these issues separately below.

1, Fraud

It is clear that the level of Shinecrest’s trade with Sony was a very

material factor in relation to the share sale agreement. The December

106

Balcombe L.J. ‘Themehelp Ltd. v. West (C.A.) 11996)

correspondence showed that the sellers knew that the loss of the Sony

trade was then possible, if not probable, and that this loss could have a

very damaging effect on Shinecrest’s future prospects. Whatever the sellers

may have hoped in January, if they received Sony’s monthly budget

forecasts in March, April or May 1992 they must have realised that what

the seller West had anticipated in his letter of 19 December 1991, “the

virtual conclusion of trade between Sony (U.K.) Ltd. and Shinecrest,”