Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Physiotherapy in Rural and Regional Australia

Uploaded by

Tiwari VikashOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Physiotherapy in Rural and Regional Australia

Uploaded by

Tiwari VikashCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/5875245

Physiotherapy in rural and regional Australia

Article in Australian Journal of Rural Health · January 2008

DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00931.x · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

35 2,131

3 authors, including:

Elizabeth Williams

University of Melbourne

9 PUBLICATIONS 378 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Development of head control in the infant View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Elizabeth Williams on 05 January 2018.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Aust. J. Rural Health (2007) 15, 380–386

Original Article

Physiotherapy in rural and regional Australia

Elizabeth Williams, Wendy D’Amore and Joan McMeeken

School of Physiotherapy at the School of Rural Health, The University of Melbourne, Shepparton,

Victoria, Australia

Abstract with tangible rewards and recognition of physiothera-

pists’ contribution to the health care of Australians are

Objective: To inform rural physiotherapy recruitment recommended.

and retention strategies by describing physiotherapists

in the Shepparton region: reasons for career choice, KEY WORDS: physiotherapy, rural, workforce, allied

education and physiotherapy professional issues. health.

Design: Survey.

Setting: Health service providers. Introduction

Participants: Practising and non-practising physio-

therapists. The Australian Government1 has a vision that rural,

Main outcome measure: Survey responses. regional and remote Australians will be as healthy as

Results: Survey response rate 79%. Eighty four physio- other Australians. Currently the health of rural and

therapists (79 practicing and 5 non-practicing; 80% remote Australians lags behind city counterparts partly

female) clustered in main regional centres responded. due to shortages of health professionals,2 a situation

Two-thirds worked part-time with most in the public predicted to worsen as the population ages.3 Physio-

sector (70%), with one third holding more than one therapists are primary care health professionals who

position. One-third considered themselves generalists maximise mobility and quality of life by using clinical

and one-third specialists. Physiotherapy was first career reasoning to select and apply appropriate management

choice for 83% who made this decision between 14 and and treatment strategies to promote health, prevent

19 years old (16.8–2.5 years) because of contact with a injury and maintain function. For example, physiothera-

physiotherapist. Professional issues challenging physio- pists reduce waiting lists and improve patient satisfac-

therapists in a rural location are compounded by lack of tion in orthopaedic surgery outpatients and emergency

career path, professional support, access to professional departments.

development and postgraduate education. Additional Physiotherapy consultations for people aged over

issues are the costs and time to attend courses and 65 years have risen 43% between 2001 and 2005.4

conferences, travel/distance, and inadequate resources. However, the Department of Employment and Work-

Positive elements of rural practice were part-time place Relations identifies a national shortage of physio-

employment opportunities, independence as primary therapists for 9 of the last 10 years.5 This is greatest in

health providers, practice variety and community rural and remote areas, with only 18% of the workforce

recognition. located in rural Victoria.6

Conclusion: Rural physiotherapy recruitment and Previous investigation of workforce problems in rural

retention strategies must address resource shortcomings medicine has focused on government investment in

by developing career paths, access to postgraduate strategies to increase and support the medical work-

education and support. Enhancing workforce capacity force.7,8 There is little in the peer-reviewed literature

could enable more students to have meaningful rural that explicitly presents strategies for enhancing the

experience to assist recruitment. Strategies highlighting rural physiotherapy or broader allied health work-

existing positive features of rural practice, reinforced force.9 Models for sustainable service delivery for

remote areas where the shortage of health professionals

is acute have been described,10 but there is limited tar-

Correspondence: Elizabeth Williams, School of Physiotherapy, geted investment for physiotherapy. Additionally, in

School of Rural Health, University of Melbourne, Graham general there is poor recognition by governments that

Street, Shepparton, Victoria, 3630, Australia. Email: physiotherapy is a discrete profession, as it is generally

e.williams@unimelb.edu.au aggregated into ‘allied health’ with a range of different

Accepted for publication 13 July 2007. professionals as disparate as audiology and podiatry.

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2007.00931.x

PHYSIOTHERAPY IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 381

What is already known on this subject: What this study adds:

• There are many papers on the rural work- • Describes the distribution and work charac-

force shortage of medical practitioners and teristics of physiotherapists in a region of

nurses but only a small number on physio- rural Victoria.

therapy, which has had a severe national, • Identifies barriers to professional practice in

state and regional workforce shortage for rural physiotherapy.

decades. • Recommendations to promote rural physio-

• Some recent reports provide aggregated data therapy as a preferred career for students and

which do not identify issues specific to the clinicians, and review employment planning,

physiotherapy profession. including improved resources and promotion

of positive elements.

Recently, allied health professions including physio-

and retention of the workforce and, therefore, access to

therapy have been considered in projects to address

physiotherapy in the region.

recruitment and retention of rural allied health

professionals.11–13 One paper identifies rural and remote

physiotherapy as its own discipline.14 The assumption Method

that results from one profession can be generalised to

others is a limitation, and current research strongly rec- The Human Research Ethics Committee of the Univer-

ommends that issues related to specific professions sity of Melbourne granted ethics approval.

should be addressed.15 Increasing recognition of the sig-

nificant contribution to health and wellbeing by phys- Survey design

iotherapists is beginning to be reflected by government

initiatives,16 although to date no strategic, national The survey contained sections on education and profes-

workforce planning has been done.6 sional practice. Education referred to qualifications,

Physiotherapists, as one of the largest clinical profes- the age and reasons for respondents’ decisions to study

sions and one with the most critical workforce shortages physiotherapy, experiences of physiotherapy, and fami-

and high attrition rates,17 was selected for this study as ly’s professional backgrounds. Professional practice

an exemplar profession to develop and implement a recorded respondents’ current work situations, nature

model for determining key professional practice issues of employment, hours worked in physiotherapy and

to inform recruitment and retention strategies in additional occupations. Questions explored issues in

regional Australia. There is no currently available local working as a physiotherapist, whether these were

rural physiotherapy workforce information in areas related to the rural location, and the community’s per-

such as Shepparton. ception of them as primary rural health care providers.

Shepparton is a regional city in the Goulburn river The final section invited physiotherapists to propose

valley in Victoria, Australia. It is renowned for dairying solutions.

and fruit growing, with the City of Greater Shepparton

as the site of secondary industries such as food process- Participants

ing and supporting agricultural activities. Greater Shep-

parton has a population around 59 000 and is classified Names of physiotherapists were obtained from publicly

rural. The catchment area of 100-km radius (population available resources, including the telephone directory,

135 000) defines the distribution of patients who attend the Physiotherapists Registration Board of Victoria

the region’s health services, and this region was selected and the Australian Physiotherapy Association. Non-

for the project. practising physiotherapists were identified by personal

The project aim was to describe the demographics of referrals.

practising and non-practising physiotherapists in the

Shepparton region, their distribution, reasons for career

Data collection and analysis

choice, education and professional issues to rural prac-

tice. Physiotherapists would be invited to provide solu- Physiotherapists provided informed consent and surveys

tions for issues identified. Responses of subgroups such were completed by telephone interview or mail.

as public and private practitioners would be examined Responses to questions were numeric or categorical

to provide recommendations to improve recruitment with additional opportunities for open-ended or mul-

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc.

382 E. WILLIAMS ET AL.

FIGURE 1: Distribution of physiotherapists in the Shepparton region.

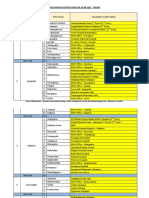

TABLE 1: Work-related travel

Distance travelled per day (km)

Travel n (%) 0–25 26–50 51–100 >100 Maximum Mean (range)

Home to work 79 (100) 57 15 6 1 120 20 (1–120)

For work 25 (32) 12 3 7 3 200 52 (0–200)

Between workplaces 18 (23) 7 8 3 0 100 32 (0–100)

tiple responses. Data were entered into Microsoft Excel ing and five non-practising physiotherapists completed

coded for anonymity. Open-ended responses were tran- the survey (n = 84; 79% response rate, 80% female,

scribed and the data coded using descriptive thematic 57% aged less than 40 years), with most working in the

analysis. Coding tables were developed from the most regional centres of Shepparton, Benalla and Wangaratta

prevalent answers to each question. Data were extracted (Fig. 1). Most physiotherapists travelled less than 25 km

into SPSS v.12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago IL, USA) for to work, but 55% travelled for work or between

descriptive statistical analysis. workplaces (Table 1).

Results

Education and career choice

Participants Physiotherapy studies were undertaken in Victoria

Physiotherapists were contacted for the survey between (69%), interstate (26%) and overseas. Baccalaureate

January and June 2005 (n = 107). Seventy-nine practis- degrees were most common (82%) with others holding

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc.

PHYSIOTHERAPY IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 383

TABLE 2: Summary of full- or part-time positions by 30

Number of physiotherapists

gender

25

Part-time (%) Full-time (%) Total (%) 20

Male 5 (31) 11 (69) 16 (20) 15

Female 46 (76) 17 (24) 63 (80) 10

Total 51 28 79 5

0

1 or less >1–2 >2–3 >3–4 >4–5 >5

diplomas. Twelve (14%) had completed postgraduate Days worked per week

masters degrees or diplomas, and two PhDs were in

progress. FIGURE 2: Total number of days physiotherapists worked

Physiotherapists chose their careers at 16.8 ⫾ per week.

2.5 years. Three-quarters had previous experience of

physiotherapy as patients or through work experience.

Two-thirds had family backgrounds in health or educa-

Health-promotion activities and illness-prevention

tion. Those with no previous physiotherapy experience

programs were delivered by both public and private

wanted to work in health or with people, had sporting

physiotherapists (53%). These activities included

interests, or received information from career/open

strength and balance programs for older persons,

days. Physiotherapy was first career choice for 83%,

groups for hydrotherapy, cardiopulmonary rehabilita-

and 81% were accepted into physiotherapy on their first

tion and community presentations. Fifteen per cent of

application. Half (n = 7) of those who stated that phys-

health promotion activities was volunteered time.

iotherapy was not their first choice were among those

Nearly all respondents considered that they were

who had no previous experience of physiotherapy.

primary health care providers with patients self-

referring. Sixty per cent perceived that their community

Employment characteristics regarded physiotherapists as primary health care pro-

The 79 physiotherapists held 114 clinical positions, gen- viders, but were concerned at lack of recognition by

erally located in the public sector (70%). These were: some medical GPs and specialists. While over half per-

public hospitals 40%; community centres 15%; and ceived that their community knew physiotherapy’s

academic or government departments 15%. Private roles, some considered that the public were confused

practitioners comprised 30%. More than one position between similar fields and had inadequate knowledge of

was held by 37%. Physiotherapists worked an average physiotherapy.

four days per week (range 0.5–6.5); 35% working four

to five days, with 19% working two days (Table 2,

Fig. 2). Half preferred part-time work owing to family Professional issues in physiotherapy

commitments. Seven of 11 practicing physiotherapists

who had other than physiotherapy work described

and physiotherapy rural practice

themselves as farmers. Questions determining issues in rural physiotherapy

Public-sector physiotherapists included managers, practice differentiated between those related to physio-

senior clinicians and those in recent graduate rotation therapy generally or rural practice specifically. General

positions. Fifteen per cent of those in private practices issues were needs for professional satisfaction and

were owner/managers, the others employees. rewards, support and supervision, and opportunities for

Including public and private physiotherapy, clinical professional development. There was no difference

practice areas were described as outpatients (32%), between public or private practitioners’ response to this

general physiotherapy (25%) or musculoskeletal phys- question. The 187 responses regarding professional

iotherapy (22%). Thirty-eight per cent considered that issues for rural physiotherapists are aggregated themati-

they specialised in a particular aspect of clinical practice. cally in Table 3.

Most wished to be recognised as specialists, some as Respondents offered solutions to resolve the issues

specialist generalists in ‘rural physiotherapy’. Many identified as specific to rural practice. These included

responded that generalist skills were needed in rural accessible and appropriate professional development.

areas, owing to small communities, varied client base, They identified that the self-funding required for profes-

variety of treatments required and being a sole sional development often precluded participation by

practitioner. respondents. Additional funding was necessary to

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc.

384 E. WILLIAMS ET AL.

TABLE 3: Professional issues for rural physiotherapists TABLE 4: Solutions or strategies for professional issues

Category Total† Category Total†

Professional development Professional development

Lack of access to professional development 38 Provide accessible and appropriate professional 25

Lack of access to postgraduate education 35 development

Lack of time for postgraduate/professional 2 Provide accessible and appropriate postgraduate 9

development education

Total 75 Provide teleconferencing, video-conferencing, 6

online education

Support and supervision Rotate hospital staff (between hospitals) 4

Lack of professional and peer support 30 Total 44

Isolation 9

Lack of networking: professional and 6 Support and supervision

community Set up links and meetings of 14

Lack of physiotherapy specialists/senior 3 physiotherapists/special interest groups

clinicians support

Total 48 Professional association provide more rural 12

representation, professional support and

Professional satisfaction mentoring

Lack of career path, career development and 17 Total 26

specialisation

Required to be a generalist 11 Professional satisfaction

Lack of job satisfaction and recognition 9 Develop career pathways/opportunities with 7

Total 37 acknowledgement of specialisation, including

as ‘rural generalist’

Recruitment, retention and lack of resources Improve medical practitioner and community 4

Staff shortages/inadequate staffing 13 awareness/understanding of physiotherapy

levels/difficulty recruiting Total 11

Personal financial return poor/lack of funding 11

Lack of locum availability 3 n = 84, †More than one response per person.

Total 27

n = 84, †More than one response per person. data indicate that in the Shepparton area, the ratio is

much less, at 45 per 100 000. Extrapolating from the

response rate where 6% were non-practising, there

improve salaries, to enable scholarships, and to facilitate could be 6 or 7 additional physiotherapists potentially

recruitment and retention of physiotherapists (Table 4). available. With the chronic and severe shortages of

physiotherapists, there might be potential to attract

non-practising physiotherapists back into the work-

Discussion force, provided that their professional and personal

This study is the first to identify the work patterns and concerns are addressed.

workforce concerns of physiotherapists within a defined

rural health service catchment area. It revealed a

complex workforce that is fragmented by part-time Education and career choice

work, multiple workplaces, and overlap within the The critical age for career choice of these physiothera-

public and private sector. pists was nearly in the final stage of secondary school-

ing. For students to study physiotherapy in Australia,

prerequisites in science subjects are required. Potential

Participants

rural physiotherapists are influenced by a rural second-

Nearly all physiotherapists in the survey area were in ary school background17 and need exposure to the pro-

practice. The most recent national physiotherapy work- fession before they have made irrevocable school subject

force data4 indicate that there are 70 full-time equivalent choices. Aside from family, physiotherapy work experi-

(EFT) physiotherapists per 100 000 Victorians. Our ence and being treated by a physiotherapist were major

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc.

PHYSIOTHERAPY IN RURAL AUSTRALIA 385

career influencers for these respondents. Baldwin and infrastructure, requires financial commitment by Gov-

Agdo15 showed that although practitioners are influen- ernment at local, State and Federal levels.9,14

tial, secondary school careers’ counsellors might be an Specific concerns related to practice were poor career

important information source for potential physiothera- paths for both public and private clinical physiothera-

pists. The shortage of rural clinical physiotherapists pists who received inadequate recognition from govern-

precludes work experience for many applicants. ments and the medical profession and consequent

Innovations, which do not compromise the existing under-use of their knowledge and skills, particularly in

clinical practice of busy professionals, are required for the areas of illness and disability prevention, health

secondary students to learn about health careers in rural promotion and primary care. Concomitantly, there was

areas. lack of professional development through postgraduate

and continuing education and professional support.

These were compounded by the cost and time to attend

distant courses and conferences, sometimes limited by

Modification to employment to enhance

workplace restrictions on time off work, no availability

workforce efficiency

of locums, or lack of staff expertise to cover workload.

Physiotherapists in this region were predominantly All issues were affected by lack of resources and sus-

female (80%), higher than the Victorian physiotherapy tained concerns regarding recruitment and retention.

workforce average (72%).6 Female physiotherapists are The impositions put upon physiotherapists for clinical

more likely to be working part-time and within the service where there are acute and/or chronic workforce

public sector.4 In Victoria, 37% of the physiotherapy shortages and their roles are indispensable,11 are leading

workforce is part-time, compared with 51% in this to significant attrition.6

survey, where the average time worked was six hours As the community’s need for physiotherapists grows,

per week less than the State average.6 Family responsi- reinforcement with tangible rewards and recognition

bilities were cited for part-time work preference, but this of the positive elements of rural practice is necessary.

might also reflect lack of flexibility in positions or Flexible employment opportunities, independence and

factors such as inadequate child or after-school care. autonomy as primary health providers, variety in prac-

Increased employer responsiveness to the needs of tice and community recognition are required. While

female health professionals is essential.5 senior physiotherapists must be retained, strategies to

Many practitioners held more than one physiotherapy recruit physiotherapists through rural internships for

position, leading to inefficiencies when travel is required junior physiotherapists or bonded scholarships for

between positions or work sites. Although travel for senior students have the potential to improve recruit-

work for most physiotherapists was less than 25 km, ment and service delivery, and might assist staff

30% were required to travel longer distances. This retention.7,8

might be an additional factor limiting time available or Further research is indicated replicating the study at

desired for professional practice. Expansion of roles and other rural and regional centres so that targeted work-

funding to cover the existing 15% of time spent in force strategies for recruitment and retention could be

volunteer work might also increase necessary service measured. It is recommended that questions be

provision, while accommodating professional aspira- expanded to include ‘intention to stay’. In order to

tions. increase the opportunities for student physiotherapists

Clinical practice focused on the breadth of general to experience rural practice, the perceived capacity and

physiotherapy with a large musculoskeletal component; concerns regarding having physiotherapy students for

however, many physiotherapists desired recognition clinical placements should be obtained.

for their specialist work as ‘rural physiotherapists’.

Sheppard and Nielsen14 reinforce supporting physio-

therapists’ frequent role as single practitioners needing

Conclusions

both to be generalists in physiotherapy and to overlap Most physiotherapists living in a regional area of

into other disciplines where there are fewer medical Victoria are in practice, although they work shorter

specialists and other allied health professionals. The hours than metropolitan contemporaries, but often

increasing importance of physiotherapy’s role in the holding more than one part-time physiotherapy position

promotion and maintenance of health, particularly as by choice, sometimes in both public and private sectors.

it applies to an ageing population with several The project showed that time, cost and distance are

co-morbidities, is identified in the range of programs barriers to profession-specific and specialist postgradu-

described by the study physiotherapists. Recognition of ate education. Positive elements of rural practice are

roles and responsibilities, largely in the public sector, part-time employment opportunities, independence as

and the development of area resource networks and primary health providers, variety in practice and some

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc.

386 E. WILLIAMS ET AL.

community recognition. Workforce strategies must be 7 Brooks RG, Walsh M, Mardon RE, Lewis M, Clawson A.

reviewed and resourced to address the growing need The roles of nature and nurture in the recruitment and

for clinical placements, reward unremunerated health- retention of primary care physicians in rural areas: a

promotion activities, and address shortcomings of review of the literature. Academic Medicine, 2002; 77:

790–798.

access to postgraduate qualifications, career paths and

8 Dunbabin JS, McEwin K, Cameron I. Postgraduate

providing professional support.

medical placements in rural areas: their impact on the

rural medical workforce. Rural and Remote Health,

Author contributions 2006; 6: 481.

9 Williams E, McMeeken JM. Relations and Rewards Are

Elizabeth Williams developed the survey design, Key Strategies in Recruitment and Retention of Rural

methods, applied for ethics approval, contributed to Physiotherapists. Melbourne: Department of Human Ser-

analysis, and drafted and finalised the manuscript. vices, State Government of Victoria, 2005.

Wendy D’Amore conducted the survey, acquired the 10 Battye KM, McTaggart K. Development of a model for

data, analysed the results and contributed to writing the sustainable delivery of outreach allied health services to

manuscript. Joan McMeeken made a substantive intel- remote north-west Queensland, Australia. Rural Remote

Health 2003; 3: 194.

lectual contribution, reviewed the survey methods and

11 Belcher S, Kealey J, Jones J, Humphreys J. The VURHC

ethics application, and contributed to interpretation of

Rural Allied Health Professionals Recruitment and

results and writing and finalising the manuscript. Retention Study. Melbourne: Victorian Universities Rural

Health Consortium, Department of Human Services,

State Government of Victoria, 2005.

References 12 Cuss K. Allied Health Recruitment & Retention Project.

1 Australian Government Healthy Horizons.Outlook Central Hume Primary Care Partnership. Melbourne:

2003–2007. 2002. [Last updated 15 September 2004; Department of Human Services, State Government of

Cited 16 March 2006] Available from URL: http:// Victoria, 2005.

www.health.gov.au/internet/wcms/publishing.nsf/ 13 Schoo A, Stagnitti K, Mercer C, Dunbar J. A conceptual

Content/ruralhealth-policy-healthyhorizons.htm model for recruitment and retention: allied health work-

2 Schofield DJ, Earnest A. Demographic change and the force enhancement in western Victoria, Australia. Rural

future demand for public hospital care in Australia, 2005 and Remote Health 2005; 5: 477.

to 2050. Australian Health Review 2006; 30: 507–515. 14 Sheppard L, Nielsen I. Rural and remote physiotherapy:

3 Mathers CD, Vos ET, Stevenson CE, Begg SJ. The burden its own discipline. The Australian Journal of Rural Health

of disease and injury in Australia. Bulletin of the World 2005; 13: 135–136.

Health Organization 2001; 79: 11. 15 Baldwin A, Agho AO. Student recruitment in allied health

4 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Physiotherapy educational programs: the importance of initial source of

Labour Force 2002. AIHW Cat. No. HOWL 37. Health contact. Journal of Allied Health 2003; 32: 65–70.

and Labour Force Series no. 36. Canberra: AIHW, 2006. 16 Productivity Commission. Australia’s Health Workforce

5 Human Capital Alliance. Recruitment and Retention of Research Report. Canberra: Australian Government,

allied Health Professionals in Victoria – A literature 2005.

review. Report to the Victorian. Government Department 17 Carroll S, McMeeken JM. Establishing the Value of Rural

of Human Services. Melbourne: Human Capital Alliance, Clinical Placements During Undergraduate Allied Health

2005. Education. Melbourne: Co-ordinating Unit for Rural

6 Department of Human Services. Physiotherapy labour Health Education in Victoria, 2000.

force, Victoria 2003–2004. Melbourne: State Govern-

ment of Victoria, 2006.

© 2007 The Authors

Journal Compilation © 2007 National Rural Health Alliance Inc.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Correctional Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third EditionFrom EverandCorrectional Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, Third EditionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Occupational Therapy in Australian Acute Hospitals: A Modified PracticeDocument9 pagesOccupational Therapy in Australian Acute Hospitals: A Modified Practicesarawu9911No ratings yet

- Physiotherapy Awareness Among Doctors in NepalDocument15 pagesPhysiotherapy Awareness Among Doctors in NepalValentina Dela Fuente GarroneNo ratings yet

- Nova ScotiaDocument8 pagesNova ScotiadelbojNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Occupational Therapists Practising in Rural Australia: A Graduate PerspectiveDocument6 pagesPerceptions of Occupational Therapists Practising in Rural Australia: A Graduate PerspectiveMagno NunesNo ratings yet

- Physical Therapy Research in Professional Clinical PracticeDocument5 pagesPhysical Therapy Research in Professional Clinical PracticeProductivity 100No ratings yet

- Creating A Sustainable Rural General Surgery WorkforceDocument13 pagesCreating A Sustainable Rural General Surgery WorkforceJeff CrocombeNo ratings yet

- ARTG - 2011 - PT Practice in Acute Care SettingDocument14 pagesARTG - 2011 - PT Practice in Acute Care SettingSM199021No ratings yet

- (Laura Lee (Dolly) Swisher PT PHD, Catherine G. P PDFDocument228 pages(Laura Lee (Dolly) Swisher PT PHD, Catherine G. P PDFmemonsabaa61100% (1)

- Nursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An IntegrativeDocument13 pagesNursing Competency Standards in Primary Health Care - An Integrativecarlos treichelNo ratings yet

- Assessing Physiotherapists' Knowledge of Perineal CareDocument5 pagesAssessing Physiotherapists' Knowledge of Perineal CareTomi AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Learning Activity No. 6Document13 pagesLearning Activity No. 6Jonah MaasinNo ratings yet

- Reading Nurse DutiesDocument6 pagesReading Nurse DutiesJannatu RNo ratings yet

- End of Life Care: Leadership and Quality in End of Life Care in AustraliaDocument28 pagesEnd of Life Care: Leadership and Quality in End of Life Care in AustraliaUniversityofMelbourneNo ratings yet

- Saudi Aramco Q&ADocument12 pagesSaudi Aramco Q&AAzad pravesh khanNo ratings yet

- Aquatic Therapy For Occupational Therapy Education and PracticeDocument123 pagesAquatic Therapy For Occupational Therapy Education and PracticeAURORA BADIALINo ratings yet

- Analyzing The Role of Advanced Practice Nursing in The PhilippineDocument35 pagesAnalyzing The Role of Advanced Practice Nursing in The PhilippineAnalyn SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Awareness and Knowledge of Physical Therapy Among Medical Interns A Pilot StudyDocument7 pagesAwareness and Knowledge of Physical Therapy Among Medical Interns A Pilot StudyInternational Journal of PhysiotherapyNo ratings yet

- Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners in Specialty Care. CALIFORNIA HEALTHCARE FOUNDATIONDocument0 pagesPhysician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners in Specialty Care. CALIFORNIA HEALTHCARE FOUNDATIONJuanPablo OrdovásNo ratings yet

- Child Obesity Service Provision A Cross-Sectional Survey of Physiotherapy Practice Trends and Professional NeedsDocument8 pagesChild Obesity Service Provision A Cross-Sectional Survey of Physiotherapy Practice Trends and Professional Needsanggie mosqueraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1836955319300803 MainDocument3 pages1 s2.0 S1836955319300803 MainRegina CeballosNo ratings yet

- BrothertonDocument7 pagesBrothertonMaya HammoudNo ratings yet

- Advanced Practice Nursing in The Philippines: Are We There Yet?Document5 pagesAdvanced Practice Nursing in The Philippines: Are We There Yet?Alex LavadiaNo ratings yet

- Contamproary Practice IssuesDocument22 pagesContamproary Practice Issuespihabo3594No ratings yet

- Aot 69 625Document12 pagesAot 69 625NataliaNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity Promotion in Physiotherapy Practice: A Systematic Scoping Review of A Decade of LiteratureDocument7 pagesPhysical Activity Promotion in Physiotherapy Practice: A Systematic Scoping Review of A Decade of Literaturearaaela 25No ratings yet

- Knowledge of Physiotherapy Services Among Hospital-Based Health Care Professionals in Papua New GuineaDocument7 pagesKnowledge of Physiotherapy Services Among Hospital-Based Health Care Professionals in Papua New GuineaMuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ama Changemeded International Webinar SeriesDocument46 pagesAma Changemeded International Webinar Seriesqwerty123No ratings yet

- Usual Care Physiotherapy During Acute Hospitalization in Subjects Admitted To The ICU: An Observational Cohort StudyDocument10 pagesUsual Care Physiotherapy During Acute Hospitalization in Subjects Admitted To The ICU: An Observational Cohort StudyJhon F. GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Awareness of Physiotherapy Fields Among Medical ResidentsDocument6 pagesAwareness of Physiotherapy Fields Among Medical ResidentsValentina Dela Fuente GarroneNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion 2Document7 pagesHealth Promotion 2Murad KurdiNo ratings yet

- PA Final Report Jan 09 Version 5Document47 pagesPA Final Report Jan 09 Version 5Sean HalliganNo ratings yet

- Asian Nursing ResearchDocument7 pagesAsian Nursing ResearchnandangNo ratings yet

- Cahpter 1 Health Care Professional: MasrulDocument7 pagesCahpter 1 Health Care Professional: Masrulvera syahrinisyaNo ratings yet

- Physiotherapy MahsaDocument6 pagesPhysiotherapy Mahsanicky214No ratings yet

- hw499 Ass 6Document2 pageshw499 Ass 6api-518578297No ratings yet

- Recovering Mind and Body (Mental Health)Document24 pagesRecovering Mind and Body (Mental Health)Shivamani143100% (1)

- An International Survey On Advanced Practice Nursing Education, Practice, and RegulationDocument10 pagesAn International Survey On Advanced Practice Nursing Education, Practice, and RegulationCarmela Lacsa DomocmatNo ratings yet

- Extending The Nursing Role in Emergency Departments: Challenges For AustraliaDocument10 pagesExtending The Nursing Role in Emergency Departments: Challenges For AustraliaAnonymous nEQNlgbYQCNo ratings yet

- Physical Therapy in Occupational Health and ErgonomicsDocument3 pagesPhysical Therapy in Occupational Health and ErgonomicsgaboinklNo ratings yet

- Can Physiotherapists Contribute To Care in The Emergency Department?Document3 pagesCan Physiotherapists Contribute To Care in The Emergency Department?J Roberto Meza OntiverosNo ratings yet

- Current Recommendations For Reform in Education For Health ProfessionalsDocument76 pagesCurrent Recommendations For Reform in Education For Health ProfessionalsAurora Violeta Zapata RuedaNo ratings yet

- How Primary Health Care Staff Working in Rural andDocument8 pagesHow Primary Health Care Staff Working in Rural andsafa haddadNo ratings yet

- KLD Entry - Extended AbstractDocument9 pagesKLD Entry - Extended AbstractDianne NuñalNo ratings yet

- Description of Physical Therapy: Policy StatementDocument10 pagesDescription of Physical Therapy: Policy StatementBenny WirawanNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction of Rural Nurses in District Hospitals in The Province of Leyte - CompressDocument64 pagesJob Satisfaction of Rural Nurses in District Hospitals in The Province of Leyte - CompressArdiene Shallouvette GamosoNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing The Choice of Specialty of Australian Medical GraduatesDocument6 pagesFactors Influencing The Choice of Specialty of Australian Medical GraduatesOlgaNo ratings yet

- WFC Industry Skills Report Primary Health Care 2012-09-24Document24 pagesWFC Industry Skills Report Primary Health Care 2012-09-24farah goharNo ratings yet

- Iphac CHN Comp SkillsDocument54 pagesIphac CHN Comp SkillsRoscelie KhoNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesDocument9 pagesReview Article: Advanced Practice Nursing Education: Challenges and StrategiesluNo ratings yet

- Complementary Therapies in MedicineDocument8 pagesComplementary Therapies in Medicinekhadesakshi55No ratings yet

- Guidelines To Physical Therapist Practice APTADocument1,006 pagesGuidelines To Physical Therapist Practice APTAGustavo Cabanas82% (11)

- Research Seminar FinalDocument15 pagesResearch Seminar FinalAmanda ScarletNo ratings yet

- Ruba Naz Siddiqui Objective: Bachelor in PhysiotherapyDocument4 pagesRuba Naz Siddiqui Objective: Bachelor in PhysiotherapyASHUMEHMOODNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Occupational TherapyDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Occupational Therapygz8reqdc100% (1)

- Espana Boulevard, Sampaloc, Manila, Philippines 1015 Tel. No. 406-1611 Loc.8241 - Telefax: 731-5738 - WebsiteDocument4 pagesEspana Boulevard, Sampaloc, Manila, Philippines 1015 Tel. No. 406-1611 Loc.8241 - Telefax: 731-5738 - WebsiteNikkie SalazarNo ratings yet

- Spinal Cord InjuryDocument6 pagesSpinal Cord InjuryAngela ValeroNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument5 pagesAnnotated BibliographynishthaNo ratings yet

- Revised Curriculum DPT-UHS (15!09!15)Document294 pagesRevised Curriculum DPT-UHS (15!09!15)Iqra Iftikhar50% (2)

- Structured Mentoring StrategiesDocument31 pagesStructured Mentoring Strategiesrandy gallegoNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Traditional Complementary and Alternative MedicineDocument16 pagesIndonesian Traditional Complementary and Alternative MedicineIrene RaphaNo ratings yet

- Waiver For Organizations Accreditation and Oathtaking at Tanghalang Meycaueno - New Cityhall Saluysoy - On December 13 2022 - 1PM To 4PMDocument1 pageWaiver For Organizations Accreditation and Oathtaking at Tanghalang Meycaueno - New Cityhall Saluysoy - On December 13 2022 - 1PM To 4PMGuenevere EsguerraNo ratings yet

- Risk-Assessment-Clean Agent - 369852Document10 pagesRisk-Assessment-Clean Agent - 369852Mohammed Amer Pasha100% (1)

- Psychological Theories of Crime ChartDocument1 pagePsychological Theories of Crime ChartTayyaba HafeezNo ratings yet

- Patient Satisfaction With Hospital Care and Nurses in England: An Observational StudyDocument10 pagesPatient Satisfaction With Hospital Care and Nurses in England: An Observational StudySelfa YunitaNo ratings yet

- Dehradun Distributor RetailersDocument238 pagesDehradun Distributor RetailersAmit DesaiNo ratings yet

- Vaccination Centers On 20.08.2021Document10 pagesVaccination Centers On 20.08.2021Chanu On CTNo ratings yet

- ID Gambaran Status Gizi Pasien Diabetes Mel PDFDocument12 pagesID Gambaran Status Gizi Pasien Diabetes Mel PDFcatur rinawatiNo ratings yet

- Hazards and Risks of Catalyst Replacement at Butane TreaterDocument32 pagesHazards and Risks of Catalyst Replacement at Butane TreaterIhdaNo ratings yet

- Lemon Grass-Shruti RanadeDocument6 pagesLemon Grass-Shruti RanadeMarites ParaguaNo ratings yet

- JMS - Filling Up New GravelDocument6 pagesJMS - Filling Up New GravelSilver SelwayneNo ratings yet

- Dialog Patient AdmissionDocument3 pagesDialog Patient AdmissionYunita TriscaNo ratings yet

- How Do Organisms Reproduce Class 10 Notes Science Chapter 8 - Learn CBSEDocument20 pagesHow Do Organisms Reproduce Class 10 Notes Science Chapter 8 - Learn CBSEPranav MurkumbiNo ratings yet

- Nursing Leadership Theory Paper ErDocument9 pagesNursing Leadership Theory Paper Erapi-642989736No ratings yet

- Daily Pattern of Energy Distribution and Weight LossDocument6 pagesDaily Pattern of Energy Distribution and Weight LossAldehydeNo ratings yet

- Coping Mechanism of Grade 12 Students of Birbira High School On The Face-To-FaceDocument25 pagesCoping Mechanism of Grade 12 Students of Birbira High School On The Face-To-FaceaiyahnuevaNo ratings yet

- Evaluasi Tumbang & Gangguan PertumbuhanDocument38 pagesEvaluasi Tumbang & Gangguan PertumbuhanAdliah ZahiraNo ratings yet

- Shouldice Hospital Case Study SolutionDocument10 pagesShouldice Hospital Case Study SolutionSambit Rath89% (9)

- Good Morning, I Love You Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Practices To Rewire Your Brain For Calm, Clarity, and Joy by Shauna ShapiroDocument163 pagesGood Morning, I Love You Mindfulness and Self-Compassion Practices To Rewire Your Brain For Calm, Clarity, and Joy by Shauna ShapiropimpamtomalacasitosNo ratings yet

- Career Fair ReflectionDocument5 pagesCareer Fair Reflectionapi-533449252No ratings yet

- FALL 2023 Career Exploration Presentation 25% Chatham Final RubricDocument3 pagesFALL 2023 Career Exploration Presentation 25% Chatham Final RubricShyann HollandNo ratings yet

- Leadership That Get Results PPT (FINAL)Document11 pagesLeadership That Get Results PPT (FINAL)vicky gaikwadNo ratings yet

- Research ObisitasDocument21 pagesResearch ObisitasDhikaRhNo ratings yet

- Method of Statement For Survey & Setting Out MakkahDocument17 pagesMethod of Statement For Survey & Setting Out MakkahToufeeq.HSE AbrarNo ratings yet

- Old School Bulking 101Document52 pagesOld School Bulking 101Vladimir Filciu80% (5)

- Research Methodology MCQ 180629120038 PDFDocument95 pagesResearch Methodology MCQ 180629120038 PDFbmk2k450% (2)

- (2014) Pneumonia CURSDocument46 pages(2014) Pneumonia CURSAna-MariaCiotiNo ratings yet

- Prevention and Management of Occupational Diseases in Hong KongDocument56 pagesPrevention and Management of Occupational Diseases in Hong KongB AuNo ratings yet

- Supplier Audit ChecklistDocument11 pagesSupplier Audit ChecklistOlexei Smart100% (1)

- Medical Form Brandon 2020 PDFDocument1 pageMedical Form Brandon 2020 PDFAliceCameronRussellNo ratings yet

- The Five Dysfunctions of a Team SummaryFrom EverandThe Five Dysfunctions of a Team SummaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Irresistible: The Seven Secrets of the World's Most Enduring, Employee-Focused OrganizationsFrom EverandIrresistible: The Seven Secrets of the World's Most Enduring, Employee-Focused OrganizationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- The Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceFrom EverandThe Power of People Skills: How to Eliminate 90% of Your HR Problems and Dramatically Increase Team and Company Morale and PerformanceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (22)

- Scaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0From EverandScaling Up: How a Few Companies Make It...and Why the Rest Don't, Rockefeller Habits 2.0Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Powerful Phrases for Dealing with Difficult People: Over 325 Ready-to-Use Words and Phrases for Working with Challenging PersonalitiesFrom EverandPowerful Phrases for Dealing with Difficult People: Over 325 Ready-to-Use Words and Phrases for Working with Challenging PersonalitiesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- Getting Along: How to Work with Anyone (Even Difficult People)From EverandGetting Along: How to Work with Anyone (Even Difficult People)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- The Art of Active Listening: How People at Work Feel Heard, Valued, and UnderstoodFrom EverandThe Art of Active Listening: How People at Work Feel Heard, Valued, and UnderstoodRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- DEI Deconstructed: Your No-Nonsense Guide to Doing the Work and Doing It RightFrom EverandDEI Deconstructed: Your No-Nonsense Guide to Doing the Work and Doing It RightRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- Developing Coaching Skills: A Concise IntroductionFrom EverandDeveloping Coaching Skills: A Concise IntroductionRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- The Way of the Shepherd: Seven Secrets to Managing Productive PeopleFrom EverandThe Way of the Shepherd: Seven Secrets to Managing Productive PeopleRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (112)

- The 5 Languages of Appreciation in the Workplace: Empowering Organizations by Encouraging PeopleFrom EverandThe 5 Languages of Appreciation in the Workplace: Empowering Organizations by Encouraging PeopleRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (46)

- Strength-Based Leadership Coaching in Organizations: An Evidence-Based Guide to Positive Leadership DevelopmentFrom EverandStrength-Based Leadership Coaching in Organizations: An Evidence-Based Guide to Positive Leadership DevelopmentRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Summary: Who Moved My Cheese?: An A-Mazing Way to Deal with Change in Your Work and in Your Life by Spencer Johnson M.D. and Kenneth Blanchard: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Who Moved My Cheese?: An A-Mazing Way to Deal with Change in Your Work and in Your Life by Spencer Johnson M.D. and Kenneth Blanchard: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and GrowthFrom EverandThe Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and GrowthRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (101)

- 50 Top Tools for Coaching, 3rd Edition: A Complete Toolkit for Developing and Empowering PeopleFrom Everand50 Top Tools for Coaching, 3rd Edition: A Complete Toolkit for Developing and Empowering PeopleRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Crucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High, Second EditionFrom EverandCrucial Conversations Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High, Second EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (432)

- The SHRM Essential Guide to Talent Management: A Handbook for HR Professionals, Managers, Businesses, and OrganizationsFrom EverandThe SHRM Essential Guide to Talent Management: A Handbook for HR Professionals, Managers, Businesses, and OrganizationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High, Third EditionFrom EverandCrucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes are High, Third EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Radical Focus SECOND EDITION: Achieving Your Goals with Objectives and Key ResultsFrom EverandRadical Focus SECOND EDITION: Achieving Your Goals with Objectives and Key ResultsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- The Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and GrowthFrom EverandThe Fearless Organization: Creating Psychological Safety in the Workplace for Learning, Innovation, and GrowthRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Organizational Behaviour: People, Process, Work and Human Resource ManagementFrom EverandOrganizational Behaviour: People, Process, Work and Human Resource ManagementNo ratings yet

- Finding the Next Steve Jobs: How to Find, Keep, and Nurture TalentFrom EverandFinding the Next Steve Jobs: How to Find, Keep, and Nurture TalentRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- HBR's 10 Must Reads 2023: The Definitive Management Ideas of the Year from Harvard Business Review (with bonus article "Persuading the Unpersuadable" By Adam Grant)From EverandHBR's 10 Must Reads 2023: The Definitive Management Ideas of the Year from Harvard Business Review (with bonus article "Persuading the Unpersuadable" By Adam Grant)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Recruiter's Handbook: A Complete Guide for Sourcing, Selecting, and Engaging the Best TalentFrom EverandThe Recruiter's Handbook: A Complete Guide for Sourcing, Selecting, and Engaging the Best TalentRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Leadership Coaching, 2nd Edition: Working with Leaders to Develop Elite PerformanceFrom EverandLeadership Coaching, 2nd Edition: Working with Leaders to Develop Elite PerformanceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- The New Executive Assistant : Exceptional Executive Office ManagementFrom EverandThe New Executive Assistant : Exceptional Executive Office ManagementNo ratings yet

- Getting to Yes with Yourself: (and Other Worthy Opponents)From EverandGetting to Yes with Yourself: (and Other Worthy Opponents)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (27)

- Mastering the Instructional Design Process: A Systematic ApproachFrom EverandMastering the Instructional Design Process: A Systematic ApproachNo ratings yet