Professional Documents

Culture Documents

(Report) International Monetary Fund (1976) - Summary Proceedings of The Thirty-First Annual Meeting of The Board of Governor, October 4-8, 1976.

(Report) International Monetary Fund (1976) - Summary Proceedings of The Thirty-First Annual Meeting of The Board of Governor, October 4-8, 1976.

Uploaded by

ZafaratOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

(Report) International Monetary Fund (1976) - Summary Proceedings of The Thirty-First Annual Meeting of The Board of Governor, October 4-8, 1976.

(Report) International Monetary Fund (1976) - Summary Proceedings of The Thirty-First Annual Meeting of The Board of Governor, October 4-8, 1976.

Uploaded by

ZafaratCopyright:

Available Formats

SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS

1976

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

This page intentionally left blank

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Copyright

Clearance RightsLink®

Center

INTERNATIONAL

MONETARY FUND

SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS

OF THE THIRTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING

OF THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS

OCTOBER 4-8, 1976

WASHINGTON, D.C.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

This page intentionally left blank

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

CONTENTS

PAGE

Introductory Note xi

Address by the President of the Philippines, Ferdinand E. Marcos 1

Opening Address by the Co-Chairman of the Boards of Governors,

the Governor of the Fund for the Syrian Arab Republic,

Mohammed Imady 4

Presentation of the Thirty-First Annual Report by the Chairman of

the Executive Board and Managing Director of the Inter-

national Monetary Fund, H. Johannes Witteveen 12

Discussion of Fund Policy at Second Joint Session

Report by the Chairman of the Interim Committee of the Board

of Governors on the International Monetary System, Willy

De Clercq 22

Statements by the Governors for

Netherlands—W. F. Duisenberg 25

Norway—Per Kleppe 30

Canada—Donald S. Macdonald 33

Japan—Teiichiro Morinaga 37

Ireland—Richie Ryan 44

Korea—Yong Hwan Kim 47

New Zealand—R. D. Muldoon 49

Thailand—Amnuay Viravan 52

Greece—Xenophon Zolotas 53

Malta—Daniel M. Cremona 57

Discussion of Fund Policy at Third Joint Session

Statements by the Governors for

India—C. Subramaniam 61

Italy—Gaetano Stammati 66

France—Bernard Clappier 71

United Kingdom—Sir Douglas Wass 79

Indonesia—AH Wardhana 82

Philippines—Cesar E. A. Virata 85

United States—William E. Simon 87

v

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

vi CONTENTS

PAGE

Austria—Hannes Androsch 103

Germany, Federal Republic of—Karl Otto Poehl 106

Algeria—Abdelmalek Temam 109

Discussion of Fund Policy at Fourth Joint Session

Report by the Chairman of the Joint Ministerial Committee of

the Boards of Governors on the Transfer of Real Resources to

Developing Countries (Development Committee), Henri

Konan Bedie 116

Statements by the Governors for

Central African Republic—Marie-Christiane Gbokou 119

Belgium—Willy De Clercq 127

Malaysia—Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah 132

Spain—Jose Maria Lopez de Letona 138

Mauritius—Sir Veerasamy Ringadoo 140

Guinea—N'Faly Sangare 143

Tanzania—A. H. Jamal 146

Luxembourg—Jacques-Frangois Poos 152

Singapore—Hon Sui Sen 158

Discussion of Fund Policy at Fifth Joint Session

Statements by the Governors for

Nepal—Bhekh B. Thapa 161

Pakistan—Rana Mohammad Hanif Khan 164

Iceland—Matthias A. Mathiesen 170

Costa Rica—Bernal Jimenez M 170

Australia—Phillip Lynch 177

Jamaica—David H. Coore 184

Israel—Moshe Sanbar 187

Yugoslavia—Momcilo Cemovic 189

Mexico—Ernesto Fernandez Hurtado 191

Bangladesh—M. N. Huda 197

Sri Lanka—Felix R. Dias Bandaranaike 200

Paraguay—Carlos Chaves Bareiro 205

Discussion of Fund Policy at Sixth Joint Session

Statements by the Governors for

Fiji—C. A. Stinson 210

Viet Nam—Tran Duong 213

Western Samoa—Vaovasamanaia R. P. Phillips 215

Papua New Guinea—Julius Chan 218

Egypt—Mohamed Zaki Shafei 222

Grenada—George F. Hosten 229

Afghanistan—Abdullah Malikyar 233

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

CONTENTS vii

PAGE

Lao People's Democratic Republic—Bousbong Souvannavong 236

China, Republic of—Kuo-Hwa Yu 238

Concluding Remarks

Statements by

The Governor of the Fund and Bank for Ireland, Richie Ryan 241

The Governor of the Fund for the Philippines, Gregorio S.

Licaros 241

The Chairman of the Executive Board and Managing Director

of the International Monetary Fund, H. Johannes Witteveen 243

The Co-Chairman of the Boards of Governors, the Governor

of the Fund for the Syrian Arab Republic, Mohammed

Imady 246

Schedule of Meetings 251

Provisions Relating to the Conduct of the Meetings 252

Agenda 253

Reports of the Joint Procedures Committee

Report 1 254

Annex I Review of Performance of the Development Com-

mittee—Recommendation of the Development Committee

and Report by the Executive Directors of the Bank and the

Fund 255

Annex II Transmittal of Proposed Resolution on Review of

Performance of the Development Committee 260

Report II 261

Annex I Report of the Development Committee 263

Annex II Rules for the Conduct of the 1976 Regular Election

of Executive Directors of the Fund 279

Statement of Results of Elections, October 5, 1976 285

Annex III Amendments of Rules and Regulations 289

Annex IV Membership for Guinea-Bissau 291

Annex V Membership for Surinam 292

Report IV 293

Resolutions

31-1 Remuneration of Executive Directors and Their Alter-

nates 294

31-2 Increases in Quotas of Members—Sixth General Review 295

31-3 Fifth General Review of Quotas—Nepal 299

31-4 Proposed Second Amendment to the Articles of Agree-

ment 300

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

viii CONTENTS

PAGE

31-5 Benefits of Executive Directors and Their Alternates 301

31-6 Membership for the Comoros 302

31-7 Membership for Seychelles 305

31-8 1976 Regular Election of Executive Directors 307

31-9 Review of Performance of the Development Committee. 308

31-10 Financial Statements, Report on Audit, and Administra-

tive Budget 308

31-11 Amendments of the Rules and Regulations 309

31-12 Membership for Guinea-Bissau 309

31-13 Membership for Surinam 311

31-14 1976 Regular Election—Ballots of Governors for Bahrain

and Oman 313

31-15 Appreciation. 314

Interim Committee of the Board of Governors on the International

Monetary System

Press Communique, October 2, 1976 315

Composition (as of October 2, 1976) 318

Announcement, October 6, 1976 319

Composition (as of October 6, 1976) 319

Joint Ministerial Committee of the Boards of Governors of the Bank

and the Fund on the Transfer of Real Resources to Developing

Countries (Development Committee)

Press Communique, October 3, 1976 320

Composition (as of October 3, 1976) 323

Announcement, October 6, 1976 324

Composition (as of October 6, 1976) 324

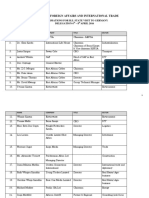

Attendance

Members of Fund Delegations 325

Observers 341

Executive Directors, Alternates, and Advisors 344

Reference List of Principal Topics Discussed 345

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

STATEMENTS BY GOVERNORS

Listed in Alphabetical Order by Country

PAGE

Afghanistan—Abdullah Malikyar 233

Algeria—Abdelmalek Temam 109

Australia—Phillip Lynch 177

Austria—Hannes Androsch 103

Bangladesh—M. N. Huda 197

Belgium—Willy De Clercq 127

Canada—Donald S. Macdonald 33

Central African Republic—Marie-Christiane Gbokou 119

China, Republic of—Kuo-Hwa Yu 238

Costa Rica—Bernal Jimenez M 170

Egypt—Mohamed Zaki Shafei 222

Fiji—C. A. Stinson 210

France—Bernard Clappier 71

Germany, Federal Republic of—Karl Otto Poehl 106

Greece—Xenophon Zolotas 53

Grenada—George F. Hosten 229

Guinea—N'Faly Sangare 143

Iceland—Matthias A. Mathiesen 170

India—C. Subramaniam 61

Indonesia—Ali Wardhana 82

Ireland—Richie Ryan 44

Israel—Moshe Sanbar 187

Italy—Gaetano Stammati 66

Jamaica—David H. Coore 184

Japan—Teiichiro Morinaga 37

Korea—Yong Hwan Kim 47

Lao People's Democratic Republic—Bousbong Souvannavong. . . 236

Luxembourg—Jacques-Frangois Poos 152

Malaysia—Tengku Razaleigh Hamzah 132

Malta—Daniel M. Cremona 57

Mauritius—Sir Veerasamy Ringadoo 140

Mexico—Ernesto Fernandez Hurtado 191

Nepal—Bhekh B. Thapa 161

Netherlands—W. F. Duisenberg 25

ix

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

x STATEMENTS BY GOVERNORS

PAGE

New Zealand—R. D. Muldoon 49

Norway—Per Kleppe 30

Pakistan—Rana Mohammad Hanif Khan 164

Papua New Guinea—Julius Chan 218

Paraguay—Carlos Chaves Bareiro 205

Philippines—Gregorio S. Licaros 241

Cesar E. A. Virata 85

Singapore—Hon Sui Sen 158

Spain—Jose Maria Lopez de Letona 138

Sri Lanka—Felix R. Dias Bandaranaike 200

Tanzania—A. H. Jamal 146

Thailand—Amnuay Viravan 52

United Kingdom—Sir Douglas Wass 79

United States—William E. Simon 87

Viet Nam—Tran Duong 213

Western Samoa—Vaovasamanaia R. P. Phillips 215

Yugoslavia—Momcilo Cemovic 189

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Copyright

Clearance RightsLink®

Center

INTRODUCTORY NOTE

The Thirty-First Annual Meeting of the Board of Governors of the

International Monetary Fund was held in Manila, Philippines, from

October 4 through October 8, 1976, jointly with the Annual Meetings

of the Boards of Governors of the International Bank for Reconstruc-

tion and Development, the International Finance Corporation, and the

International Development Association. The Hon. Mohammed Imady,

Governor of the Fund for the Syrian Arab Republic, and the Hon. Sadek

Ayoubi, Governor of the Bank and its affiliates for the Syrian Arab

Republic, served as Chairmen.

These Summary Proceedings include statements (or portions of state-

ments) relating to the work of the Fund presented by Governors during

the Meetings, resolutions adopted by the Board of Governors of the

Fund over the past year, reports and recommendations of the Joint

Procedures Committee, material pertinent to the 1976 regular election

of Executive Directors, and other documents relating to the Meetings.

The statements are arranged in chronological order; the insertion of

dots ( . . . ) within statements indicates where passages have been omitted.

Many of the statements at the Meetings referred to international

monetary reform and the proposed amendment to the Fund Agreement.

A separate Supplement to these Summary Proceedings reproduces the

text of the Proposed Second Amendment to the Articles of Agreement

of the International Monetary Fund: A Report by the Executive Direc-

tors to the Board of Governors, initially issued by the Fund in March

1976. The Supplement contains the Report by the Executive Directors,

including the text of the proposed amendment to the Articles of Agree-

ment, and an index to the proposed Articles. The Appendix to Part II

of the Report containing a comparison of the present and the proposed

Articles of Agreement has not been included in the Supplement.

A reference list of principal topics discussed in the statements will

be found on pages 347-49.

XI

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

xii SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

Statements relating to the work of the Bank are reproduced in the

Summary Proceedings of the Annual Meetings of the Bank and its

affiliates, issued by the Bank.

W. LAWRENCE HEBBARD

Secretary

International Monetary Fund

Washington, D. C.

November 16, 1976

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Copyright

Clearance RightsLink®

Center

ADDRESS BY THE PRESIDENT OF THE

PHILIPPINES1

Ferdinand E. Marcos

It is a pleasure for me to welcome, on behalf of the Government and

people of the Philippines, the distinguished officials, delegates, and

guests at these joint Annual Meetings of the Governors of the Inter-

national Monetary Fund and the International Bank for Reconstruction

and Development.

We are singularly honored that on their first conference in Southeast

Asia, the Bank and the Fund have chosen to meet here in the

Philippines. We have looked forward to this event, and we are confident

that it will have far-reaching effects on the welfare of nations and

millions of peoples around the world.

In the last few years, a world in crisis has made of these Annual

Meetings of the Bank and the Fund a forum for searching deliberations

on the overriding economic and social problems of this decade. The

severity of the crisis has ebbed but we have not entirely overcome its

effects. As the Governors so clearly appreciated in previous meetings,

urgent, specific problems have merely underlined the larger issues.

To the simultaneous incidence of inflation and recession, both

developed and less developed countries have addressed substantial

parts of their energies over the last few years. A combination of

national and transnational strategies has succeeded in restoring growth

to many economies. The developing countries, upon whom the burdens

of inflation and material shortages weighed the heaviest, by a remark-

able exercise of national will have shown themselves stronger than the

grimmest prognosis.

Yet recovery is shadowed by fears and actual perils of a relapse into

crisis. The full results of policies and actions taken in earlier years still

have to materialize in forms that truly enhance the well-being of all

our countries. We stand on the threshold of great expectations, antici-

pating the best from all those policies and actions, but it is doubtful

that what we have done is enough to meet all the residual, recurrent,

and altogether new problems.

1

Delivered at the Opening Joint Session, October 4, 1976.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

2 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

Already, published studies of the world economic outlook, and in

particular of the prospects of the developing countries, project unprece-

dented payments deficits at the end of the year and grave problems for

the rest of the decade. While official development assistance has de-

clined from 0.52 per cent in 1960 to 0.32 per cent in 1975, substantial

amounts now need to be channeled to the developing countries if

reasonable growth targets are to be achieved.

We have learned that behind the many problems of specific urgency

and effect is the implacable face of human poverty. This is the real

beast we have to subdue. In the case of the Philippines, ours is a free en-

terprise society with an egalitarian base. We are restructuring that society,

on the basis of the rebellion of the poor, without necessarily converting

the neediest of these into mendicants. Commensurate with every effort we

have taken to combat inflation and recession, we have taken cognizance of

the need to restructure the economic relationships among nations. But

sentiment alone, though it may travel at an unusually high velocity, will

not suffice; proposals must now pass into programs that work. We

must step into authentic expansion and growth.

Needless to say, substantive differences remain as to how each nation

or a group of nations looks at the new order that we must evolve.

Whatever these differences between nations or groups of nations, they

do not postpone the need to rectify global conditions. The global rebel-

lion of the poor has begun. It must succeed. Unless we conquer poverty

in our time, we shall forever continue to move from problems caused

by poverty to problems that cause more poverty.

For this reason, we look to the International Monetary Fund and

the World Bank for relief. Both institutions have an impressive record

of service to the world community. In recent years, the Bank has

adopted a new approach to world development that stresses above all

the need to confront poverty. It has insisted that the pressures of crisis,

though they require urgent treatment of specific problems such as infla-

tion and payments deficits, must at no time obscure, let alone com-

promise, meaningful programs of social change.

In the Fund, some beginning has been made toward international

monetary reform. Governors of the Fund have approved a far-reaching

series of amendments to the IMF Articles of Agreement concerning

exchange rate arrangements, special drawing rights, and the role of gold

in the emerging system. I hereby announce today the acceptance by the

Philippine Government of the second amendment of the Articles of

Agreement of the IMF, and call upon other member countries to accept

this amendment, which may yet rectify the regrettably small role of the

developing countries in the Fund's decision-making process and which

conforms to the Manila Declaration and Program of Action.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY PRESIDENT OF PHILIPPINES 3

But these developments, although commendable and significant, form

only part of a necessarily larger transformation process. Policies must

now be matched with sufficient will and resources. Commitment to the

development of Third World countries must now support the develop-

ment not only of the poor but of the poorest.

Specifically, there is need to generate capital that would be available

for those in need, to reform the terms and conditions of capital trans-

fers or lending programs and policies. The replenishment of IDA funds

and the selective increase of capital of the Bank directly support these

objectives. It accords to the ideal of a reformed international order to

sustain the flow of capital from the developed to the developing coun-

tries as well as to have the latter find greater access to more stable

markets and receive the consideration that they deserve in the servicing

of payment of their foreign debts.

Today, the IMF and the IBRD have the historic opportunity of

bringing to a denouement the infinite and patient efforts akin to those

being waged in the United Nations General Assembly, the Economic

and Social Council of the United Nations, the United Nations Con-

ference on Trade and Development, the North-South dialogue, and

many other organizations and forums to bring about a reformed global

environment. By their definitive act, they can alter the social equation

for those who have until now borne the weight of human poverty and

want.

The limit of the possible has not been reached. This meeting in

Manila affords these two great world institutions the historic occasion

to go now beyond it. In all realism, it invites you to undertake the

effort that would extend for millions the dimensions of life on this planet.

I wish you all success in this endeavor.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Copyright

Clearance RightsLink®

Center

OPENING ADDRESS BY THE CO-CHAIRMAN OF THE

BOARDS OF GOVERNORS, THE GOVERNOR OF THE

FUND FOR THE SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC1

Mohammed Imady

It is a great privilege to follow the distinguished President of the

Republic of the Philippines in addressing this thirty-first joint meeting

of the Boards of Governors of the International Monetary Fund and

the World Bank. The welcoming speech of President Marcos reflects

the gracious friendship and hospitality with which the Philippines has

received us. Indeed, the cordial welcome extended to us by the delightful

city of Manila will long remain in our memories. May I voice at this

time the appreciation of all participants at this joint meeting for the

personal efforts of the President and the First Lady to provide us with

this magnificent new convention center designed by the talented Filipino

architect, Leandro Locsin, whose building combines innovative effi-

ciency with artistic design.

As Chairmen of the Boards of Governors, Chairman Ayoubi and I

wish to add our greetings to those of President Marcos. We welcome

the Governors, their alternates, our observers, and special guests. A

special welcome is extended to the Governor for Papua New Guinea,

which is participating for the first time as a member of our institutions,

and to the Fund's newest member, the state of the Comoros. Special

greetings are also offered the observers from Cape Verde, Maldives,

and Sao Tome and Principe, which have applied for membership, and

from Seychelles, whose membership Governors have already approved,

and to Guinea-Bissau and Surinam, whose memberships are on our

agenda here.

To these expressions of good will, I am pleased to add the greetings

and best wishes of my own country, the Syrian Arab Republic, which

I am honored to represent as Governor of the Fund. Throughout the

ages many phrases have been coined to describe Syria—land of

prophecies, birthplace of the world's earliest alphabet, cradle of civili-

1

Delivered at the Opening Joint Session, October 4, 1976. Mr. Mohammed

Imady, Governor of the Fund for the Syrian Arab Republic, and Mr. Sadek

Ayoubi, Governor of the Bank, IFC and IDA for the Syrian Arab Republic,

acted as Chairmen of the Annual Meetings.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY CO-CHAIRMAN OF BOARDS OF GOVERNORS 5

zation, and crossroads of three continents. Ancient in its proud Arab

heritage, and modern in its aspirations, Syria is all these things. It is

also a developing country, involved in a struggle to help restore pros-

perity and a just peace to the troubled Middle East.

Our Annual Meetings provide the occasion once again for reviewing

the state of the world economy and the important developments in the

work of the Fund and the World Bank.

This year, 1976, is expected to be a favorable one for the industrial

countries in particular and consequently—although to a lesser degree—

for the world economy as a whole. Recovery is now well under way

and firmly established in the industrial countries. These countries,

which suffered from a negative rate of growth in 1975, are now

expected to achieve a rate of around 6 per cent in real gross national

product. Moreover, they have also achieved during this year a some-

what limited success in combating inflation, though its expected rate

remains high when compared with the average during 1962-72.

There is no doubt that these favorable developments in the industrial

countries will have a positive impact on the economy of the non-oil

developing countries. The export volume of these countries, which

stagnated in 1975, is expected to grow by more than 8 per cent in

1976. Partly as a result of these developments, it is expected that their

current deficits will decline from $37 billion in 1975 to $32 billion

in 1976.

Despite these favorable developments, the undeniable fact remains

that the current balance of payments situation of the non-oil developing

countries remains a source of serious concern. This becomes very clear

when one realizes that their cumulative current deficits during the

three-year period 1974-76 are expected to reach around $98 billion—

far higher than during any previous three-year period. Indeed, the ratio

of current deficits to exports of a major group of non-oil debtor coun-

tries increased from 10.8 per cent in 1973 to around 30 per cent in

1976. As a result, the external debt of developing countries reached a

very high level which is estimated to be more than $130 billion. The

seriousness of the problem is intensified by the fact that most of the net

capital inflow to non-oil developing countries during the last three years

was contracted on terms harder than before.

While concern is warranted, exaggerated fears are not justified.

These countries cannot continue incurring such large current deficits

and financing them on hardened terms without facing serious external

debt problems in the near future. Action is required to avoid the emer-

gence of such problems. This action must be taken by the developing

countries, the industrial countries, and the international financial

institutions.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

6 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

The developing countries have asserted in many international forums

that the task of their development devolves primarily upon themselves.

Indeed, many of them have taken measures to improve the mobilization

of their domestic resources and to diversify their exports. The savings

of poor people in poor countries have provided a far larger proportion

of development investment than have external resources. But the effec-

tiveness of national development efforts is adversely affected by unfa-

vorable international developments and a lack of positive action in the

fields of trade, commodity stabilization, and concessionary aid.

There is no doubt in my mind that the growing current deficits of

the non-oil developing countries during the last three years and the

subsequent sharp increase in their indebtedness are mainly attributable

to the external forces of inflation and recession in the industrial world.

The limited recovery of the past year has had some favorable impact

on the developing nations. Regrettably, no discernible progress has yet

been made in the cooperative struggle needed to achieve a new, and

more equitable, international economic order. Such a new order re-

quires the development of institutions and practices to redress the

imbalances of present international market forces. Market forces can

be an equitable and efficient means of allocation when wealth and

economic power are fairly balanced. When large disparities exist, as

they do in today's world, the market works only in favor of the rich

and the powerful.

In the industrial countries themselves, the social progress of the past

century has centered on the efforts of progressive people, governments,

and labor unions to humanize the market's blind forces. The developing

countries now urge a similar effort at the international level.

The means necessary to this end have been discussed at length at

international meetings in Lima, Nairobi, Colombo, and'the continuing

dialogue in Paris. The essentials are a common fund for buffer stock

financing and real progress in winning developing countries freer access

to developed countries' markets to help improve their terms of trade

and export performance.

The industrial countries must intensify their efforts to reach the sec-

ond development decade's target of devoting 0.7 per cent of their gross

national product to development assistance; their present rate is less

than half that target. The need for such increased aid flows has been

dramatically underlined by a World Bank study showing that additional

capital transfers of $30 billion to $40 billion a year will be needed to

meet the United Nations' goal of 6 per cent annual growth in the 1970s.

The aid performance of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting

Countries during the last three years, and particularly of the Middle

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY CO-CHAIRMAN OF BOARDS OF GOVERNORS 7

East oil producers, has been remarkable. This performance is even

more commendable when it is remembered that it is based on the

exportation of depletable wealth, rather than renewable income sur-

pluses, and that it is not tied to donor country procurement or used as

a mechanism for utilizing idle capacity or for alleviating unemployment.

Against this background, the International Monetary Fund has

recently taken an important step in the process of international mone-

tary reform toward which it has been moving since the collapse of the

Bretton Woods system in late 1971. As Chairman of the Board of

Governors of the International Monetary Fund, I had the privilege

earlier this year of bringing before the Board the proposals of the

Executive Directors for modifications of the Articles of Agreement that

will provide a more realistic international monetary system.

These proposals—embodied in a draft amendment—were approved

by a resolution of the Board of Governors on April 30, 1976 and now

await acceptance by member governments. They bear witness both to

the ability of the Fund, through its members, to reach compromises on

difficult issues and to the Fund's concern for the interests of all mem-

bers. I urge all members to speedily ratify these amendments.

This second amendment of the Articles of Agreement leaves the

time-honored purposes of the Fund unchanged. It also does not alter

substantially members' entitlement to access to the general resources of

the Fund or the conditionality of their use, features which are intended,

as before, to safeguard both the Fund and its members. The amend-

ment does, however, bring substantial changes in regard to exchange

arrangements, gold, and the SDR.

The new Article IV on exchange arrangements will legalize the float-

ing of exchange rates that has been widely practiced since 1973 by

permitting member countries to have exchange arrangements of their

choice. The amendment reflects a sense of realism and creates possi-

bilities for a more effective adjustment process.

But floating is not and cannot be totally free—for the simple reason

that no country can realistically abstain from trying to influence such

an important economic variable as its exchange rate. It is, thus, all the

more necessary that international rules be agreed upon to ensure that

situations of serious conflicts do not emerge and that the burden of

adjustment is equitably shared.

Some rules may already exist in the form of implicit or explicit

understandings among major central banks. The issue of adjustment is,

however, the concern of the international community as a whole: its

failure affects all countries, and often the developing countries the

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

8 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

most. The rules for such adjustments should be agreed upon within the

Fund and administered by that institution.

The second amendment also brought important changes in reducing

the role of gold in the international monetary system with the objectives

of making the SDR the principal reserve asset. The SDR has begun to

establish itself in a variety of ways: as a currency peg, as a unit of

account in international transport, for bond issues, and as a definition

of obligation in many international agreements. The sale of IMF gold

goes a long way toward reducing the monetary role of gold. Never-

theless, if national gold reserves are valued at market-related prices—

in view of the expected legalization of the use of gold between central

banks—the share of SDRs in total international reserves would be

reduced to less than half the 7 per cent it constituted when the new

reserve unit was first distributed. Thus, further action is still needed to

enhance the SDR's role as a reserve asset. The growth of international

reserves must be internationally and cooperatively controlled if stability

is to be restored to the world monetary system.

The developing countries must also be given a fair share in non-

earned reserve increases. The share of the non-oil developing countries

in future SDR allocations should be greater than called for under the

present criteria, perhaps 50 per cent of the total reserves to be created.

The allocation of a larger share of new SDRs to the developing

countries is justified by the greater reserve needs of these countries:

their exports are more vulnerable, their flexibility in adjusting imports

more limited, and they lack the access to alternative sources of liquidity

and balance of payments support enjoyed by the industrial countries.

I would urge the Interim Committee to give due consideration to the

needs of the non-oil developing countries in recommending new alloca-

tions of SDRs.

In the past year, the Fund, under the competent leadership of

Mr. Witteveen, has made commendable progress in enlarging its role

in a number of fields. There has been a substantial expansion in mem-

bers' use of the Fund's resources, with drawings reaching an unprece-

dented SDR 6.6 billion. Both developed and developing countries have

benefited. The Sixth General Review of Quotas, the establishment of

the Trust Fund, the temporary enlargement of members' credit tranches

by 45 per cent, and the liberalization of the compensatory financing

facility will add greatly to the ability of the Fund to fulfill its objectives.

The World Bank Group—the Bank, the International Development

Association (IDA), and the International Finance Corporation (IFC)—

has made an increasingly valuable contribution to economic development

in the Third World in recent years. We are delighted to witness the

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY CO-CHAIRMAN OF BOARDS OF GOVERNORS 9

progress it has achieved under the dynamic leadership of Mr. McNamara

in a number of development fields, most notably in assisting the urban

and rural poor through projects aimed directly at increasing their

productivity.

We are concerned, however, that the Bank and IDA are making

decreasing use of one of their most effective aid mechanisms: program

lending. In its early years, when some developed countries still needed

Bank assistance, program loans constituted about 38 per cent of Bank

operations. For the immediate future, a level of only 4 to 7 per cent is

planned; we feel this should be raised to some 15 per cent. Many of

the balance of payments problems facing developing countries are

structural in nature, and cannot be adequately remedied by Fund

financing or short-term stabilization programs. The required solution to

such problems is quickly disbursing long-term financing which will

allow longer-term structural remedies to be devised. This can only be

provided through Bank program lending.

Increases in the level of assistance the World Bank can offer the

developing world are also urgently needed.

After prolonged and arduous negotiations, the Bank's Executive

Directors have approved a recommendation to the Board of Governors

to selectively increase its capital by $8.2 billion, the minimum amount

needed to avoid an actual slowdown in lending because of the statutory

limits imposed by the Bank's Articles of Agreement. Under the pro-

posed selective capital increase, the Board has been able to approve a

Bank lending program of $5.8 billion for the present fiscal year.

We fully support this proposed capital increase. We recommend its

speedy approval by the Board of Governors, and urge all our member

countries to fully subscribe to the shares offered to them.

It must be noted, however, that the agreement to recommend the

selective capital increase was won only at a high price. This price will

be paid by the developing countries—those very countries that the

Bank was created to assist. The price included an understanding that

future yearly lending programs would be based on an assumption that

no general increase in the Bank's capital would be forthcoming. Thus,

the Bank's annual lending will be frozen at $5.8 billion current dollars,

with shortened grace and maturity periods. In real terms, this agree-

ment means a decline in future lending.

Such a decline was probably inevitable, in the absence of a general

increase in the Bank's capital. But to insist—as did certain member

countries—on such a freeze in lending as an explicit condition for the

selective capital increase was constrictive and contrary to the spirit of

international cooperation for development.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

10 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

A further price was paid in the adoption of an automatic formula

under which the Bank's lending rate will be set automatically each

quarter at a level Vi of 1 per cent higher than its borrowing costs in

the previous quarter. This formula was initiated in July and forced an

increase in the lending rate to 8.9 per cent.

We firmly believe that this formula is not necessary to ensure the

Bank's financial soundness. The World Bank is very sound already;

the new lending rates will have a nearly negligible impact on the finan-

cial ratios which demonstrate this soundness. Worst of all, the price

will be paid directly by the developing countries—at a time when they

are already faced with serious payments and external debt problems.

Continuation of this formula could transform the World Bank from the

world's leading development institution into a commercial institution.

We urge the Executive Directors to reconsider this decision. It should

be abolished as soon as practicably possible.

The World Bank is clearly the most important of the world's multi-

lateral development institutions. A continued expansion of its oper-

ations is of paramount importance to the developing countries. We

urge that planning for a vitally necessary general increase in its capital

be undertaken as quickly as possible.

Negotiations toward a Fifth Replenishment of the IDA have been

under way for more than a year. The urgency of this replenishment

has increased with the realization that quick action is necessary if

IDA's commitment power is to be extended beyond July 1977, a very

short nine months from now.

I cannot overly stress the importance of IDA. It is the strongest

financial link—now amounting to more than $10 billion—between the

international community and its poorest members. The developing

countries attach the greatest importance to replenishing its resources,

at the very least, to the real level of IDA IV.

Most unfortunately, the very slow progress of negotiations so far has

given rise to fears that the whole future of IDA may be at stake. We

urge those industrial countries which have fallen behind in their efforts

to reach the United Nations' target of devoting 0.7 per cent of their

gross national product to official development assistance to show their

determination to reach this goal by agreeing to a generous Fifth

Replenishment of IDA.

The Executive Directors have also acted to strengthen the World

Bank's potential involvement in the private sector of developing country

economies by authorizing a major increase—from $107 million to $480

million—in the capital of the IFC. In its 20 years, IFC—the only inter-

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY CO-CHAIRMAN OF BOARDS OF GOVERNORS 11

national financial institution focusing on the private sector—has com-

mitted $1.5 billion to 271 enterprises in 61 countries. Last year, the

Corporation and its associated investors accounted for some 7 per cent

of net nonpetroleum investment in the developing countries.

Increasing IFC's resources more than fourfold would allow the Cor-

poration a much greater impact. It would enable it to expand its role

as promoter and honest broker to undertake more and larger projects

and to join more fully with private capital sources in such fields as

natural resource development. Increased capital would also allow IFC

a deeper involvement in both projects and financial institutions in

smaller and less developed countries—in Africa and elsewhere—in

which market structures do not yet allow small entrepreneurs to fulfill

their potential.

The activities of the International Monetary Fund and the World

Bank—under the imaginative leadership of Mr. Witteveen and Mr.

McNamara—have contributed significantly to improving the well-being

of the world community. The need for further monetary reform and

expanded development assistance is still great. The disparity between

the wealth of nations continues to widen; stability in their financial

relationships has not yet been achieved.

Greater economic security and prosperity in the developing countries

will allow for the increase in international production and trade which

is the only real answer to the need for growth without inflation: ulti-

mately, it will benefit the industrialized countries as much as their de-

veloping neighbors. A stable, equitable, and internationally controlled

monetary framework must be created as the basis for this relationship.

Until these twin goals are achieved, world progress—and, indeed,

world peace—will continually be threatened.

Two hundred years ago, Adam Smith wrote of the wealth of nations.

Since then that wealth has multiplied to a level unimaginable in 1776.

The question before our international community is not one of sharing

the wealth a few nations possess today. Our goal instead must be the

creation of a new order that will put today's wealth to its most produc-

tive uses, to join in a cooperative effort to invest in a more prosperous

future for all nations.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Copyright

Clearance RightsLink®

Center

PRESENTATION OF THE THIRTY-FIRST

ANNUAL REPORT1

BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE EXECUTIVE BOARD AND

MANAGING DIRECTOR OF THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

H. Johannes Witteveen

Mr. Chairman, I join you in thanking President Marcos for his

cordial welcome, and in expressing our gratitude to the Government

and people of the Philippines for the friendship with which we have

been received. We are tremendously impressed by this beautiful inter-

national convention center, which provides facilities that are perhaps

unequaled anywhere else in the world. In greeting assembled delegates

and guests, may I extend a special welcome to the Comoros, our newest

member, and also to the representatives of the several prospective mem-

bers who are attending our deliberations for the first time.

In my remarks today, I will deal first with the current economic

recovery, and what I see as the principal dangers in the way of a

successful transition to sustainable growth. Next, I want to discuss the

international adjustment process. I will also report on the work of the

Fund and comment on the Fund's role under the amended Articles.

The Annual Report of the Executive Directors, which I have the

privilege of presenting to you, traces a number of encouraging develop-

ments since we met last year in Washington. The world economy is

completing its first year of recovery from the most severe recession in

four decades. Production in the industrial countries has, in general,

expanded at a satisfactory pace, and rates of inflation have been

brought down from the very high levels of 1974 and 1975. The impact

of these improvements in the industrial countries is being felt in

primary producing countries throughout the world.

One disturbing aspect of the present recovery, however, is that rates

of price increase are still very high. Among industrial countries, infla-

tion is running at an annual rate of 7 per cent this year. The continuing

high rate of unemployment is equally a cause for serious concern.

Although this rate may be expected to move down as recovery pro-

October 4, 1976.

12

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY MANAGING DIRECTOR 13

ceeds, unemployment in the industrial countries seems likely to remain

for some time at a high level by postwar standards.

National authorities are now confronted with the disturbing prospect

that policies to expand production and reduce unemployment may at the

same time aggravate the problem of inflation. Assessment of this risk is

clouded by uncertainties as to both the degree of existing spare capacity

and the response of inflation to the speed with which capacity is

absorbed. Although the 1974-75 international recession was severe, the

actual extent of available economic slack may be considerably less

than would be indicated by unemployment statistics and other conven-

tional measures of the utilization of resources. There is a danger, there-

fore, that the sense of repugnance we all feel for the social injustice of

unemployment might engender political pressures that will work for a

more rapid absorption of spare capacity than can be achieved without

producing a renewed acceleration of price increases.

I must stress that the social and economic costs of inflation, though

less immediate and less obvious than those of unemployment, can prove

to be even more corrosive. In present circumstances, continuation of

the recovery would be threatened by policies that resulted in higher

inflation. In a longer-term perspective, inflation redistributes wealth

and income arbitrarily, undermines confidence, reduces investment

incentives, and misallocates resources.

One of the elements in this chain of consequences may be a reduc-

tion in real profit margins. The recent international recession, which

was itself a consequence of various inflationary developments analyzed

in the Fund's Annual Report for 1975, had a particularly unfavorable

impact on business profits.

Even before this, the authorities in several of the industrial countries

were concerned over an apparent tendency in the past decade or so for

profit margins to become eroded. Such a tendency runs counter to the

textbook theory that profits benefit in an inflationary environment. But

this theory has perhaps not made sufficient allowance for certain phe-

nomena, such as the adverse effects on economic growth of "stop-and-

go" demand policies, directed alternately to checking inflation and

sustaining expansion, and the strength of cost-push forces in a climate

where political pressures often lead to price controls—with a result that

the share of profits may not be maintained. Pressures on the profit posi-

tion, in turn, have tended to undermine the incentive to invest and to

retard the growth of economic capacity, thus creating concern over the

possible emergence of supply bottlenecks as the current economic

recovery becomes further advanced. In some countries, such difficulties

may be compounded by the size of the government's claim on the

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

14 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

national product, and a reduction in the growth of the public sector

over the medium term may in these cases be a major policy require-

ment for the achievement of higher levels of saving and investment. For

reasons such as these, the growth of output is retarded in an infla-

tionary environment, and the objective of sustained full employment

becomes harder and harder to achieve.

As testified by the Annual Report, there is now a wide measure of

agreement that it would be a mistake to base policies on the assumption

of any long-run "trade-off" between inflation and unemployment. As

the Report points out, recent experience clearly indicates that the

effects of policies aimed at stimulating growth and employment are

likely to be short lived unless the currently high rate of price inflation

is brought down and inflationary expectations are greatly reduced.

Abatement of inflation will not come about unless fiscal and monetary

policies are able to achieve and maintain restraint over the rate of

growth in aggregate demand. These policies must be adhered to firmly,

and policy risks must not be shaded—as they often were in the later

1960s and early 1970s—so as to extract additional output in the

short term.

Restraint over the expansion of demand will be more effective, and

is likely to command wider support, if it is accompanied by various

supplementary policy measures. Depending on the particular circum-

stances of countries, such measures might include antitrust measures,

action on supply bottlenecks, specific measures of relief and retraining

to cushion the hardships of unemployment and help reduce its level,

and incomes policies to reconcile the claims of competing groups on the

national product. These measures, however, must not be allowed to

distract attention from the central need to retain control over the

national budget and over the rate of monetary expansion.

If faithfully adhered to, this type of policy should enable the indus-

trial countries to lay the basis for sustained economic growth and a

reduction of unemployment. These countries have a responsibility not

only to their own populations but also to the primary producing coun-

tries, whose prospects depend so much on developments in the indus-

trial world. A policy of cautious demand expansion in the industrial

countries, although creating the best possible prospects under the cir-

cumstances, may nevertheless mean a slower growth of their imports

than would have been visualized a few years ago. This change may

have particular impact on the non-oil developing countries.

Cautious demand policies in the industrial countries therefore need

to be supplemented by measures to improve market access for the

exports of non-oil developing countries and to increase the flow of

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY MANAGING DIRECTOR 15

official development assistance. In this regard, it is gratifying that the

industrial countries increased the real volume of official development

assistance during the recent international recession, thereby reversing

the downward trend in previous years, and that the oil exporting coun-

tries have sharply expanded their flows of aid. Nevertheless, the general

level of assistance being provided remains very inadequate in face of

the huge disparities in wealth and income among countries.

The approach to economic policy in the industrial countries that I

have outlined focuses attention on the medium-term objectives of

policy. It is not an easy strategy to follow, and will undoubtedly be

subject to short-term pressures for change. Adherence to this policy

will require skill, patience, and courage over an extended period.

I turn now to the international environment more generally. In

recent years, trade and capital flows have been affected to an extra-

ordinary degree by abnormal events and cyclical influences: a com-

modity boom, sharply higher energy prices, accelerated inflation, reces-

sion, and now resumption of economic expansion. These developments

have taken place in the context of an international monetary system

in flux.

The traditional pattern of current account balances that prevailed

until 1973 has changed substantially. Particularly striking are the huge

increase in the surplus of the major oil exporting countries and the

roughly similar increase in the deficit of other primary producing

countries.

In 1974, when the surplus of the oil exporting countries rose steeply

to some $65 billion, the three largest industrial countries—the United

States, the Federal Republic of Germany, and Japan—were embarking

on resolute anti-inflation measures. The impact of these measures on

their current account positions was dramatic. Oil-related deficits in the

three countries were rapidly offset by positive changes elsewhere in the

current account; indeed, the non-oil components of their current

account balances showed improvements from 1973 to 1974 that totaled

more than $30 billion. Inevitably, these big shifts—though not in

themselves an objective of policy—put strong downward pressure on

the current account positions of other oil importing countries. In par-

ticular, the combined deficit of primary producing countries rose from

$8 billion in 1973 to $43 billion in 1974.

The deepening and spreading of the international recession during

1975 had further pronounced effects on current account balances. The

balances of industrial countries improved as their demand for oil

declined and their exports to oil surplus countries grew rapidly. In part

because of the recession, but mainly because of rapid import expansion,

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

16 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

the combined current account surplus of the oil exporting countries fell

substantially in 1975. The non-oil primary producing countries suffered

from a weakening of demand in their principal markets and a sharp

deterioration in their terms of trade, and their combined deficit rose

further in 1975, to more than $50 billion.

Now, however, the resumption of economic expansion and import

growth in the industrial world is providing a new and different setting

for international payments adjustment. A number of the industrial

countries are running current account deficits, and in Italy and the

United Kingdom recurrent weakness in the current account was com-

pounded earlier this year by pressures in the capital account. In the

United States, the very large current account surplus that was realized

in 1975 seems likely to disappear this year—a predominantly cyclical

development tending to improve the positions of many other countries.

However, according to Fund staff estimates, the traditionally large

current account surplus of the Federal Republic of Germany will be

maintained in 1976, while the Japanese balance will move from a small

deficit in 1975 to a sizable surplus.

With the volume of world trade expected to grow by more than

10 per cent in 1976, prospects for current account improvement are

generally more favorable for the non-oil deficit countries than at any

time since 1973. It will be very important to seize this opportunity to

put the pattern of world payments on a more sustainable basis—a

development which will require internationally cooperative policies on

the part of surplus countries, as well as effective actions by deficit

countries.

Balance of payments deficits present problems of financing and of

adjustment. The emphasis that should be given to these two aspects of

the problem naturally differs according to the situation. At the time of

the oil price increase at the beginning of 1974, the immediate danger

was that countries would adopt measures of adjustment that would have

been deflationary and self-defeating, inasmuch as it was not possible for

the oil exporting countries to absorb, in the short run, sufficient imports

to eliminate their surpluses. Therefore, the Fund supported arrange-

ments designed to finance oil deficits for a time and established its own

011 facility for this purpose. Undoubtedly, these policies were successful

in preventing external restrictions and aggravation of the international

recession. But the world economy is now recovering, and is moving into

a situation where the main danger is no longer a deepening of recession

but a resurgence of inflation.

For this reason, the time has come to lay more stress on the adjust-

ment of external positions and less emphasis on the mere financing of

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY MANAGING DIRECTOR 17

deficits. Additional urgency is lent to this need by the buildup of

short-term and medium-term debt resulting from the financing of recent

years. This is beginning to affect the creditworthiness of some bor-

rowers and to create the possibility of economic and financial diffi-

culties. I may recall that the central principle of the Fund is the revolv-

ing character of its financial resources. It was never intended that these

resources should be used to help perpetuate balance of payments

disequilibria. They are intended to cushion the costs of adjustment to

a more sustainable equilibrium.

The increased flexibility of exchange rates in recent years should

help the process of adjustment. Until now, exchange rate movements

have compensated fairly well for differences in inflation among coun-

tries. But beyond this, they have not contributed as much to adjustment

as might have been hoped. There are several reasons for this.

The oil exporting countries want to diversify their economies. Under-

standably, they have not been prepared to accept an adjustment of their

exchange rates that would render their non-oil sectors uncompetitive,

and have preferred to accumulate financial assets. Other surplus coun-

tries, although not under the same compulsion to protect their competi-

tive position, have channeled their surpluses easily and almost auto-

matically into international capital markets. In this way, real adjustment

that might involve a loss of competitiveness for domestic industry has

also been avoided by those countries. At the same time, financing has

been readily available to deficit countries. And while capital markets

have given deficit countries the means to borrow, domestic objectives

have given them the incentive. The goal of stemming inflation has

prompted some deficit countries to borrow rather than allow their

exchange rates to change, because they fear that exchange rate depre-

ciation would give a further twist to the spiral of domestic inflation.

This fear is heightened by the knowledge that social and institutional

factors, such as wage indexation, can magnify a small price stimulus

into an inflationary surge. Thus, there is a temptation to leave adjust-

ment to the future in the hope that conditions may then be more

propitious.

In this process, however, the real costs of the inevitable adjustment

may, in the end, be increased. Effective adjustment involves a change

in the pattern of domestic and foreign demands on national output.

Exchange rate depreciation can help to bring about such a change, but

cannot make its full contribution if it is used as a substitute for action

on domestic demand. In order to make the required adjustment of

current account deficits, domestic policies must be arranged so as to

restrain domestic demand and to permit a shift of resources to the

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

18 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

external sector. At the same time, the adverse consequences for domestic

inflation of adjustment of the exchange rate to a level consistent with

balance of payments equilibrium need to be minimized by specific

measures outside the exchange rate field.

For industrial countries in strong payments positions, adjustment

requires in the first place that they ensure an adequate recovery in

domestic demand. But, as I mentioned earlier, the growth of demand

must be kept within prudent limits in order to avoid a rekindling of

inflationary forces. Beyond this, adjustment will have to be brought

about by increased flows of long-term capital exports and development

aid and, to the extent necessary, by an appreciation of exchange rates.

These various aspects of adjustment will have to be kept clearly in

mind in the Fund's consultations and in establishing conditions for the

use of the Fund credit tranches. They also have important implications

for the new task of the Fund under its amended Articles: the surveil-

lance of exchange rate policies. Among their obligations under the

proposed Article IV, members are to avoid manipulating exchange

rates or the international monetary system in order to prevent effective

balance of payments adjustment or to gain an unfair competitive

advantage over ether members.

In performing its duty under Article IV to ensure the effective oper-

ation of the international monetary system, to exercise firm surveillance

over the exchange rate policies of members, and to adopt specific prin-

ciples to guide members in connection with those policies, the Fund

will rely heavily on an intensification of its consultation procedures with

members. I can see a close interconnection between the regular consul-

tations that now take place under Article VIII and Article XIV and

the role of consultations to be held under Article IV. Furthermore, it

will become more important for the Fund to take the initiative to hold

special, ad hoc consultations with members whenever, in its judgment,

developments related to the exchange rate field warrant this.

To encourage adoption of the adjustment policies I have outlined, it

may be desirable for unconditional balance of payments financing to be

somewhat less readily available than it has been for some countries in

the recent past. The largest amounts of this kind of financing have been

provided by commercial banks. Through the financing they provided to

member countries in 1974 and 1975, these banks performed a valuable

service that helped to sustain world economic activity. However, in the

different situation that has now emerged, there is perhaps the risk that

too ready availability of commercial bank lending may in some cases

retard the needed adjustment. I therefore welcome the increasing

tendency for commercial banks to gear their lending to Fund stand-by

arrangements.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY MANAGING DIRECTOR 19

I know that there is concern in developing countries that balance of

payments adjustment might be harmful to development efforts, but

there is no reason to expect this to be the case. On the contrary, where

domestic prices have moved out of line, exchange rate adjustment is

an essential precondition for rapid expansion of exports. Moreover,

insofar as adjustment requires a reduction in domestic expenditure,

well-designed policies should make it possible to direct this reduction to

less essential elements of expenditure, rather than to investment. We

have recently seen that a number of developing countries have improved

their economic growth after putting into effect a successful program of

exchange rate adjustment and domestic policy measures.

The Fund's role in providing financial support to its member coun-

tries must continually adjust to changing conditions. In fact, the evolv-

ing pattern of world payments has been reflected clearly in the Fund's

financial transactions. I have already mentioned the oil facility and the

role it played in helping overcome the dangers of an overhasty response

to the sharp rise in the price of oil. This facility was established in 1974

and terminated, according to plan, in early 1976. During its two-year

life, an amount equivalent to nearly SDR 7 billion was channeled

through the facility.

In response to the 1974-75 recession, the Fund modified and lib-

eralized its compensatory financing facility in December 1975. During

the nine months since then, 40 members have drawn a total of SDR 1.9

billion on the facility, an amount one and a half times as large as the

total use of the facility over the 12 preceding years. I would expect

that, with the progress of the recovery in world trade, requests for

drawings under the facility will subside by the end of this year. The

review of the facility set for early in 1977 comes, therefore, at an

appropriate time.

The compensatory financing facility has been of considerable assist-

ance in counteracting the effects of export shortfalls after the event.

But the recession has also rekindled interest in measures that might

help to avoid excessive price fluctuations of primary products, partic-

ularly through buffer stock schemes. We have followed with great

interest the discussions that have taken place on this subject in various

forums. I might recall in this connection that the Fund itself took a

decision in 1969 to assist members with the financing of their contribu-

tions to internationally approved buffer stocks; this was followed by

decisions making the Fund's resources available to members in connec-

tion with buffer stocks for tin and cocoa and, more recently, by a

liberalization of the buffer stock facility. Without prejudice to more

general arrangements that may be negotiated, the Fund would be able

to assist members in connection with contributions to buffer stocks for

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

20 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

other commodities that might be established by agreement between

producers and consumers.

The oil facility, the compensatory financing facility, and the buffer

stock facility were all primarily designed to assist members in dealing

with payments difficulties mostly attributable to factors beyond their

immediate control. This fact is reflected in the slight degree of policy

conditionality that characterizes these facilities. But payments difficulties

do not arise from extraneous causes only. They are frequently due,

wholly or in part, to inappropriate policies in the deficit country. Even

when they are not, adjustment cannot be postponed indefinitely. As I

said earlier, there is now a need for all countries in external disequi-

librium to intensify their adjustment effort, and to give the correction of

disequilibrium a higher priority than it presently enjoys. The Fund has

the essential task of assisting members in the formulation of adjustment

programs and of providing financial assistance to deal with payments

problems while the program is taking hold.

Experience shows that, for the Fund to be effective in promoting

adequate adjustment, the amounts it can make available in support of

a satisfactory program should be substantial. This applies particularly

when payments disequilibria are large, as at present. It is therefore

gratifying to note that the Sixth General Review of Quotas will increase

the access of members to the Fund's resources by about one third on

average. Pending the entry into effect of the new quotas, access to the

Fund's resources in the credit tranches has been temporarily enlarged

by 45 per cent. Looking beyond these two steps and bearing in mind

the crucial importance of having a Fund that is adequate in size to

perform its adjustment role effectively, I attach particular importance

to the fact that the Seventh General Review of Quotas will be accel-

erated and is to be concluded by February 1978, two years ahead of

the usual schedule.

An important milestone for the Fund will be the second amendment

of the Fund's Articles of Agreement. This comprehensive amendment,

when accepted by the necessary majorities of members, will go a long

way toward adapting the Fund and its operations to present-day condi-

tions. It is therefore important that it should go into effect as soon as

possible; this will also permit the enlarged quotas under the Sixth

General Review of Quotas to become effective.

The new Articles will give members both new rights and new obliga-

tions. Since Governors are familiar with the many and important

changes to be introduced into the Articles, I do not propose to go into

detail on these matters here. I wish simply to stress that the Fund is

meant to play an increasingly important role through consultations with

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

ADDRESS BY MANAGING DIRECTOR 21

members and surveillance over the international adjustment process

and international liquidity.

Mr. Chairman, I have indicated a number of fields in which the Fund

and its members will face crucial tests. A transition must be made to

sustainable rates of economic growth and to lower rates of inflation.

At the same time, the industrial countries should take specific measures

to support the economic growth of developing countries. Balance of

payments adjustment must be pursued vigorously. And we have the

new task of establishing surveillance over exchange rate policies and

international liquidity. These are all vitally important tasks, and I trust

that we will be able to measure up to them.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

Copyright

Clearance RightsLink®

Center

DISCUSSION OF FUND POLICY AT

SECOND JOINT SESSION1

REPORT TO THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

BY THE CHAIRMAN OF THE INTERIM COMMITTEE OF THE

BOARD OF GOVERNORS ON THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM

Willy De Clercq

I want to report to Governors on the two meetings held by the Interim

Committee since last year's Annual Meeting, the first in Kingston,

Jamaica, on January 7-8, 1976 and the second last Saturday, October 2.

These two meetings, which I had the honor to chair, were the fifth and

sixth meetings of the Committee since its establishment by the Board of

Governors on October 2, 1974.

The topics on which the Committee focused its attention at its

Jamaica meeting were the world economic situation and outlook, the

policies of the Fund on the use of its resources, a number of issues

relating to the Sixth General Review of Quotas and to the disposition of

a part of the Fund's gold holdings, and, last but not least, the proposals

for amendment of the Fund's Articles of Agreement.

The Jamaica meeting took place at a time when recovery from the

severe international recession of the 1974-75 period was already under

way in much of the industrial world. In the circumstances, the Com-

mittee agreed to call on the industrial countries, especially those in

relatively strong payments positions, to conduct their policies so as to

ensure a satisfactory and sustained rate of economic expansion in the

period ahead while continuing to combat inflation. At the same time,

special concern was expressed by the Committee about the deteriora-

tion in the external position of the primary producing countries, espe-

cially the developing ones, and the difficulties of many of them to

maintain an adequate flow of imports in 1976 and to follow appropriate

adjustment policies.

In the light of its assessment of the world economic outlook, the

projected pattern of international payments, and the availability of

October 4, 1976.

22

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

CHAIRMAN OF INTERIM COMMITTEE 23

financing from other sources, the Committee was able to agree, after

considerable discussion, that the Fund should take the following actions

regarding the use of its resources and the granting of balance of

payments assistance to developing countries:

First, it was agreed that, until the effective date of the second amend-

ment of the Fund's Articles, the size of each credit tranche should be

increased by 45 per cent, which meant that the total access under the

credit tranches should be increased from 100 per cent to 145 per cent

of quota, with the possibility of further assistance in exceptional cir-

cumstances. The agreement reached in the Committee was put into effect

by a decision taken by the Executive Directors on January 19, 1976.

Second, it was agreed that the necessary steps should be taken to

establish the Trust Fund to provide balance of payments assistance on

concessionary terms to members with low per capita incomes. In May

1976 the Executive Directors adopted a Decision and an Instrument

establishing the Trust Fund, and have since then taken decisions to

enable loans to be granted.

With respect to the disposition of part of the Fund's holdings of

gold, agreement was reached on the simultaneous implementation of

(1) the restitution of one sixth of the Fund's gold to members on the

basis of quotas, and (2) the disposition of another sixth for the benefit

of developing members, with the sales of gold by the Fund as Trustee

to be made in public auctions over a four-year period. It was under-

stood that the Bank for International Settlements would be able to bid

in these auctions. These understandings provided the framework for the

decisions of the Executive Directors under which the Fund has already

held three auctions.

The Sixth General Review of Quotas had been the subject of con-

sideration at previous meetings of the Interim Committee. In Jamaica,

the Executive Directors presented to the Interim Committee a report

on the review including proposed increases in the quotas of individual

members. The Committee considered and endorsed the recommenda-

tions contained in the report and the proposed resolution to be sub-

mitted to the Board of Governors. It also agreed that, within six

months after the date of the adoption of the proposed resolution on

increases in quotas, each member that had not already done so should

make arrangements satisfactory to the Fund for the use of the member's

currency in operations and transactions of the Fund in accordance with

its policies. The proposed resolution was submitted to the Board of

Governors on February 20, 1976 and was approved by it, effective

March 22, 1976.2

1

See pages 295-99.

©International Monetary Fund. Not for Redistribution

24 SUMMARY PROCEEDINGS, 1976

Finally, with regard to the amendment of the Fund's Articles, the

Committee was able to find solutions to the few remaining issues on

which the Executive Directors had sought its guidance. Most of the

issues had already been solved through the arduous efforts of the

Executive Directors, who were able to take into account the under-

standings that had been reached by members in negotiations among

themselves or in the Committee. The Committee in particular welcomed

and endorsed the new provisions of the Articles of Agreement on

exchange arrangements that had resulted from the breakthrough

achieved in bilateral discussions.

In accordance with the understandings and the expectations of the

Committee, in March this year the Executive Directors submitted to the

Board of Governors for their approval a proposed amendment of the

Articles of Agreement together with a report containing an extensive

commentary on the proposed modifications of the Articles. The pro-

posed amendment was approved by the Board of Governors under a

resolution adopted on April 30, 1976. The proposed amendment is now

before the members of the Fund for their acceptance.

In the Jamaica meeting as in all previous meetings of the Interim