Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 188.26.199.150 On Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

Uploaded by

Paula1412Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 188.26.199.150 On Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

Uploaded by

Paula1412Copyright:

Available Formats

The Candombe, a Dramatic Dance from Afro-Uruguayan Folklore

Author(s): Paulo de Carvalho Neto

Source: Ethnomusicology , Sep., 1962, Vol. 6, No. 3 (Sep., 1962), pp. 164-174

Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of Society for Ethnomusicology

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/924459

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Illinois Press and Society for Ethnomusicology are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Ethnomusicology

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE CANDOMBE, A DRAMATIC DANCE FROM

AFRO-URUGUAYAN FOLKLORE

Paulo de Carvalho Neto

Introduction: Social Strata of the Uruguayan

Negro in our Time

y way of introduction, we should state that we divide the integral study

of the Uruguayan Negro into two large periods: A) Before the aboli-

tion; and B) From the abolition to the present. These periods, respectively,

give rise to separate study of: A) 1. Enslaved Negroes; 2. Freed Negroes;

3. the folklore common to both; and B) 1. Demographic, stratigraphic, eco-

logical and cultural problems in racial relations and contacts of the Negro

citizen; 2. Negro folklore.

With respect to the first part there are many works, some of them

good ones, although a general coordinating manual is lacking, a gap which

we intend to fill with a special book. However, on the Uruguayan Negro of

today the state of knowledge is deplorable. Above all, his demographic,

stratigraphic, ecological and cultural problems and his problems of racial

relations and contacts, etc., continue to be unknown.

In approaching and investigating the theme we had to recognize, from

the start, the existence of two social layers of Negroes which are well dif-

ferentiated. The first layer, that of the proletarian condition, is quite evi-

dent, it is the layer which lives in tenements and takes part in the carni-

vals, bringing to the latter folkloric dances which are exceedingly interesting.

The second, which is more difficult to see, enjoys a more elevated status,

frequenting cultural centers, writing and directing meetings, painting and ex-

pounding, displaying good clothes and forming social clubs among and for

themselves. It is a layer which manages periodicals, discusses ideals, pre-

sents claims and, in a certain manner, acts with the psychology of the lead-

er, attributing to itself the responsibilities of saving the present and the fu-

ture of the Uruguayan Negroes as a whole.

When we initiated in 1952 our field investigations about the Uruguayan

Negro, we selected first the proletarian layer mentioned. We still do not

know the demographic, stratigraphic, and ecological problems mentioned

above, but we have already obtained excellent data about its folklore, which

was explained in our monograph concerning the carnival in Montevideo.

We will not transcribe them in extenso in the present essay, but, re-

ferring to them, we shall discuss here the interpretation of these data and

demonstrate that a part of them constitutes an authentic dramatic survival-

ship.

Therefore, we begin this interpretation by analyzing the concept of the

dramatic dance in general.

The Concept of Dramatic Dance

This concept derives from that old classification which divides poetic

folklore into epic, lyric, satiric and dramatic folklore.

164

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NETO: THE CANDOMBE 165

-~lliiii~~ii-iii-i-Isi~~iii~iiii~ii~ B--iiii:-ii:BD.i~'i:::- : : :::?::;::::;:: :--1:::::::::::: -:::::?:::?i-jn:::;

::-::'::-- -:::---:::-:~::?:-:'-:-

:?-::: --- :-:-,-:?:;: i:::~: :-::-::::::: ::::::-:-~:a~ii~~ii~~~i;;j-;ji~,I:::

~~i;~~-i-i~~-i-;_i~iii- :I_~i-~ii~y:~-i;l::i-~i~~:~~:~:~iiiiiiis .isii~;-~-.~

~iiiaiii~--i-z-i-;-~iiiii ~:i-i:i------_:---::-:::i:-::-r-::----::I:iiss~~~:i~...-.?~------~i:i:l-i:~~i~s~ia~~,~m:~,~--s:a-i:-,i :::: ir:?:: i:::::?-i::::2;:::-:i:i':- -~:::: :i::

:::::::1:::::::::::: ::::::::::::??:: ::::-:.:-:r;:::::;-:":',2::::~-'-'::_'b

?-:-:::;::::?_i?:j:;-:-:::":::

~-ii:".~i~i-i"i--i-:-:-i-i-o--s---:-:~i:--l _$---~~i i~-:--:_-:-:--ui~i~~8-:-:s:-'::-~:i:i'B ~:?i_

I-:::-::-:-:-::ai~iiiiiiii~---i-i~i~i'~~

a-i~.i~ii?~:i-"-:_--~_-::--_u---~i~-i~i _::: . . :;. .- : ::::: .... :::: ::::::::::?: ::: i -::::;-:: _:::::-:::-: ::::-: ii_:_~-_:-~::i~::-: ii:::: -_--.. :-. :','::i?:-_~4':----':-i-'-:i?i-i"ia-i ~

_:i:--:i,::_::i:::::: --:::-:-- :;:;:???::i~~~i-~.i~ii~i;:-iilii~ii:~.i?

.8:::::::,-:::::::::._-_~-i-_~,i_-~---:_ :-1--_-----ii:i:i:~- i;..:-:_--s::::::::-_:::::

:~::

li-i:~i~i-iiii-i-:i-i~-i-ii~iiii---:~~i

::- -:-~:iii-i-~-:ii:~:i:-i~i:iii-i ~:i-iii--idi-i-iiili:i-i- ::i:-i::~iilsiii~,i-.~-a-~:i-iii~.ii~,

-:: : :::::::igiii:i~iiiiii ~:iiiiliidl'-i-:`i--il~--~i-i-~ii:~--: i.:::: ....:: .:.:_ ::.::: ::::::::::::? ~,li_~,l?":~i-i-~~~~i

~iiD-i i:::_::::-:-:_::-::::::-

ii-i-iii:i:iii~:::ii:-iii-i :~-ii;i'~i::ii~-i-iiiii-, ~~~''C''-=i'~-:':: : ? -i:iil-~i:~::l`i- ii-ii:i-i:i-iiiiii --:--:-~i:i-iici~~iiiii-i: ~-i:i~iiii.i~:: -::-:-:-::-':-:::--:-:::-: ::::::: :::::::::::::-:-:-::--:::? ::::::i:j:::::

~:!*?ir;" ?~r

::i:::::-:: ::j:::::::::::: -.-. 1:?: ::i:::::--:-:_ ; ,,iii i?:i-i:ii::ii-iii~i:il(-~:il-~--if-iii i-l-i-~-i-i ~i~'i/i:~~ii- i~i-i~iii-.:iii:i/i:i:ii:ii, '-:i:l -:---'-- -.:: i-ii::-: ?-:::-::-:?:::: :i::::: ::::jj::::::-:--:-

iiiiii~iiiiiii iiiiiiiiiii~iiiiii: i: ?i:i-.__.i :::::, :-:?::

i:iiiiiiiiiiii:-iiii?-iii:--:_ ?:;?:;iii~ii;i:ii~i:ii

..:.. ::-.::::::.:_ :_::: -~iiiiiiiiPiiii Fii.~_i.~ii,;~ii/~i::::ii-:i-i-:.-

iiiiiiiiiiiiiiii i::li:ii-i.i-.liii--: ?~-:--:--:---:-:-:----::::- :.--:- i:i-i--;i:i-. -?-: --::::::::: ::: ::::: :::: :-::--?--::iii.ii::iii:'ii--i:-.--:~:i:'~iiiii:i-iii:i-ii'i'l':'i':';? ii:i:.s i:i:i::.: :::: ---::::: iiiiii:i.:ii~i:i:~ ~:ii:i-i iiii~i??~-?-i '`'l:?$:::'':.:~i'i':''' '.'''''' ::'':':''-'"'-":':"'.'''''':'

~ii:ii-8i~iiii-iii~i-~ i:;ii:;:iiiii-i"i:

::- :..::

:i::-.-iiiii:i;-iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii~iiiiir ~iii:Di?iliiii

...: -iiil -ii- _ iiii ::: - ~~--?- -: i''' - '-'-? ''-"'-'-'-:"'''- ? ::: :::'i'i i i'i'i'iii'iiiiii :'.: iieiiii:iiiiiiii:i:.ii-::i~'i:-i~.ii:iiiiiii:iiiiiiiii~i:iiiii?i:~iiiii~iiiiii iiiiiiii ':,:''-:'-.:"'(::- :.::'::- --::il_-,--:::1 i:i-i-i: :i-iiiii--ii'ii

i;i:_i_ ::_: :.... i -::-- i:-::_-i-:i?i :.'. :::.' ':--

iiiiiiii-iiiii'i;iiiii:ii:::::::: :--:i:ia-ia:i-i:~ :-::::: i:i:iii? .:. iiiiiiiii'iiiii iii?i:i-iii-i-iii~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii-i

a:li~

:i -iiii-i i iiii: -:'i-i: i i-:-i:i :: i -iii-i-i i:i:iii:i ii~i~i:i:i:i:~-i:ii-i:i_-iii:i:i-iiii: -::::::-- iiiiiiii:siii:il,;ii::iii:i5iii:ii:iiii :iii-ni:i:i: ;:isi:ii:iii:iiii-i-iii-e ii~iiiiiiliii-i:i:,-ifi~j ::... ---:-:_.:- ::.::E :::-i:::::::-:::-::: : :: ::.::: ..:----- ;::::L::::::

;I?:.iii~:i-i,:::l-:iiiiii -i?iiiiiri:iiii:''l':-.iii:iii:iii~~ --_-,--i::-?:

iiiii-i:ii---iii- i-i:i-i-i--i-i-i~iii ...':- -i-i:i-i i:::::::::::: :ii:_ ::.: :?--_. --:::::_-i-i:i:---::?::;::? :iiiii`iiii:iiiii~i:iil~:::-:j-:::::~_-:-:;-i:~-i:::-:.-:-

iii?i:i:i-i:i-e i:~i:?ii:-_'-:~:~~_i~-:--~-:~~~B::i :ii:i~:-_:i--ii:ii:i-ii~:i:i:i:ij-i:i-i: :..: ij-j:~: * jl?i- iiiji-:::_:: iiii-~iiijiis:i:,iiiiis~iii--~iiiii~-

.:i::-:_/- i::_:ij:iiiii~;iiiiliiiiiili:i:j~iiiii-

:-ii:i:i:i-iii:i;iiiiii:i?i?iiiiii:-iii- ii-iliiiiiii,::'z,'::iiiii ,?:iiiiii:i;:i'i-i:il:'i:~:i:i

Ci-i-'li-?::ii.Ziiiiij

:~~i:?ii:i:i:iiiii~lii:si:i?i,:i:ii :i:?i~l i: -i;~~ iiii;ir-.iii-i:i-i-i-::. -:_::::: -: ii;~:i'ii :i':i:i'il-'-:-::'::: ::::?::':':'::::: ':-:"-:'"':::':::::':I::

: -i::)i: iiiii:iii:ijii'iii iiiiii~i:i-iiiili:i:iiiiiiiiiiii

iiii~iiiiisiii(iii:--~.:-:i":i:~i~~~T- : :::::1::::::::I -. -:::::::::::::::i::::::j:: :::::-.:::-:-::: : :: -r:~i?s-ili:~iiii~iliii~i~I~i~iii':%~ ia~ iiii_~~i-:i-i~si~:

iii~iili--:i--:i:i-" iiiiiiiiiiiiii::-- i-?-::~_:-::-;:::ii:::-;-:-::: i:: ::;::::: :: :ii~iiia, ,':li?ilie:iii''~_i-i-iiii

i~s:i?s-;~':;?i;: -i:i-i:~ iliiii~iiiiii-i~iiiiiiii~'"~ ~""~''"-:?-~.:BOaii~i'i~i-iii~iiiiii ::::i::il:-Xi-il-

~?~-1-:4~~~~-~',_ -------:. II::::: - -.-.-; ::-::.i--_ _:_:----::-:--_::::-:i.-;;::::::: :;:?i-:-::?:-:I:::-:: -:_-;:::: :::::::::: --- :-: i-i~iiii=ii-r:ioiii:S:i":1:::~?.::'-:: ::::-_(_:-:-:-:_::-:8\::::::~li~: ::_:_:::::i:j:i::

ii:-:-:~::::-: i.iii~iiiid~i'i~:-i8~~iF

.iiii~ii?i~ii:i-~.iiiii~i~iii-~i-ii-~i::

i~~?iiii~i~iii~i~ii-i:ii iiiii~iiiiiii :i:::::i-~ ;iiii~-:isii:i:s'i-i~iiii~-i-;-i-i~i-- ::-iiii--:-::: &:i:~--l- :i~~:S ~~~_ii~iiii~ii~j- :i-~::~,?~.:~:~i'i'i~':-'l~':"~'ii~iii~

_ii;iiDiii~~-:i:-~ iiiii,~ii i~iiii:i:i-i-::-i~iiiiiiir~i-i-:~ i. ii_:::i?i:i-:- ?i.i $-iii:i::i i i~ --iiii:i-~iiii~-i ~--:-:-:-:?:----:-iiii,--~~~~~~~.:~.~i~ :i-:w-:M:-:L::-:--:::::: :-:-,_:I ~;:::~_::::

,:::._ : :::: i--i::-:: .:--.- :-i-::-_:;i~i:i-:---r--aiiiiiiii~i-a~ aii:-ii;?:sasi:i~~ ~iiir~iiii~iii I'-ii~-iiB '~iii~?i.ii?i.-?-i-.~iiiiiii~Piiii: ii--i-i-s-i-~~iiiii-_::i:i 1-__ c~i-i:~~~~;;:il-~~ii

::. ii'ii~i~ -:~i- i ::i-i-i:i i-: i-~~~-i- -i~:i:i-i-i-~~-i:iii~~-iii ~i i:i-_:i~:ii~~ii-i

E?B~~i---~i - i ~~-:_: lii-iiiii ii-ii_:iiii~ :::--::.::?;:-::-:::::::::I:-:-:--:-:-:- ~,~g~-'''"'~'""':'-"'''''"'--"'':- i~l~-:~~::~,~~~=_~~:-~:i-~,: :-i--'i--:x-i:-i-i~?i--

"-'i~i-i ~ii~ii:~: ::-:ii:.:::?-5-'' :-- -:-:-:'-'' ':.:------------ --:-'- li~~:i:i: ~-i~5~- ;',liri~-iiiii

II ~'-'~- l ??-__ ?i-:i:i:: iiiiii:~iii~_i-ii~iii: ~ ~i-i-i-ii-- ia-~~ii-:i:-iii~--ii ?

i?i:i:iiili?i iiii-i:i-i :iiii:iiiii:i::li:_::::i:?ri-._ ;,:: i~iiiii:i:i i~-~~ai::s~: I:::;:-~~:-i;:':_--;;

?------: -':'-'- ::::- :a:-i-?:-~::, --?iii:i-i i-i:---: -i:ii:-i-i-~i:i:i-ii~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

iii iiiiiii ~:i--i-i:i-i-i-i F::-::?:::i::::-.- -:_-:.?:?:-:::;I_:, . :... ::::::::::ii-i-i:i _ --:i- i-::i:i-ii~ii-iii~i-iii:-?i i:i:--i:i?i i ....

.- I-' -i-lli I:i-l ii ii ii:i::- ii "-~''''''''' .~~il::i::.i:l:i-:~-:--:: i- i:i:?:-iiii-ii-iiii-iiiiiiiijiii- ~iiii; i

_?-,_ i. i--: ~"' Il-i-??.*:._*-- -:1-? :: iiii ::. --ili ..... -i:i:::::i?~:i::i-_ :..:. -i-i:i-i ..::-:.: --:i--- -'i'i'i 'ii:~_I-:iiii~l-iii:i

I~~_~ ? iii-i ..:.. .':'. :?i- i i:i i ii : -:-:-: ~iiiiiiiiilii?-:-:_::::- i-iiiii~iiiiiiw -iiiii iiiii-i -,-, :.:::..' :::::::: : .:. ::::: :::::

-i---iiiii iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii:: - -:-:-:-::- --:-:

i-ii? .i:i_::ii i-ii: . ii:ii:iii-i::-i-ii-i:i-iii-i ?i-iii-i --i:i-iigi:ii-iii:iiiii:ii-_--::- ::.-.-. :::::. ----:iii::- ---_:-::-_

i~..~ --: :i-i.i:i.i ii-- iiii?i-iiiii:i~i-i ?i-~ iii-:iiii-i; ; -'-?-Fiiiii:i_?'i:i:i-iii:i-i _i-i:::-_----i~:- -:::::::: : :: ::i-ii :i:i:i-i iiii:ii-i:-:i-ii:~-~-::-:i:iiiilili`i:- -----:~?-;----?:-:-:i-i-:

?i ~:;i l~:i l~ ::-:_-_.- i~i:

:: iiii-

:.... -iiiii --i-i_:i;i-ii:i~-:i-iii-i--i~isiiiiii~i-iiiiiiiiii~iii iiiiiiiiiiiiiiii

iiii-ili?i: i4i

*iii-~:~iii -i~i-i-i i- :- -i --~.--_:-:_ -----:-i:----:::--

-:i-::i:?- iii ::::----:-:--:i-::: :::::i::::

iiiiiZ,,i:i - -::i -iii:~i- ai i~iiii;~~iii-lilii~iii~ ~iiiBi-:-i-~i-i-iiiiitic-i-i-

iliijii~ii~iii is~iiiiiiii i-i-~zi?i-i -:.:---- i-i__:;:--_~-

--ii,?-s~--j:--_ ?--_i-

:_::::- : :::I-:::::::::si~aii:=iiji~iiiiii9i~iiiii;~ iiiiriiili~i~--:-:::::-::--

,~iiii~iiiii~iiS

ii -:iii~iii:~ ~::~- -:::::,i ii--i:~~ili:-~~iii-~~i~,i~Fiii~

:::?:-:-?::-::::: a-_::-i::;~--''~!~-:I~i~~~li~_iiiiii:_ iiii:~i__i _i_~iii~~~iii~::_

-:::--~~.-:::::

~.~~ :i:,:~ii:- ~;ii--i -ii~:i: iii-~iiiPi-i-ii~ iiii-x-i:i:~-ei::-:-i :

-ii-~iiiiii

:: ---~-

::~i iiii:: i -- --i:i:i-_-: i::-8-i-i':_l I-ii i i:- --i-i::iii:::

- ----iii~i: ...

.-.--. .

:': r-!ili-l~j_ --lii -~ iiiii: i-iii:

: -iiii~iiiiF' ''":" '-' :?-:' "''::'- ::':' -':'''- - ::'li :--I-:I:-_I - :::i -. . :

i:ii:iiii ii-:::i ::: -:i-:::iiiiii::--i iiiiii:-i,-i -.....: .... :::

i-i-~iii-i-i::-:- ::::::::i:iiij

-i -i:i:~i-i_-i- ;-i:ir-i;i- l-l

:

":~-:i-:?. ~"? 'L I ~_~?-::-.--:::-: :--':':. -::::---- :':':' :----:--:--:::---: -~

:~: ~::::

-kiiii~-'a ~:::: :ii~iil~ ~i:::: iii-i::'li:- -:l-iii-_-i-:_:::::_-i::~i-iii-ii::: :::_::-:___::::_:_::ii-:~:iiii:i:::-iii-

B ::.:..: -~::::-:: -:-: -:'i-:-:: ::i-i:: .......- .... .. --.... -i-ii-ii::

--i:: ::-::i?- :i-i-::::::::::::::-i::: :--:i:iiS ?-:-i::-;j:-

:'zp~ ~:$ ::: - -ii-::-i-::iiii

-- -:---- -:-:- -i-i:-i-i--::;i::: :i:: :::::--::::-::

---:~

:~iiiiiii~~ ::::::::-:---:_- ...- :: -ii-i-~.:-.i-i~-ii ii --: i~i:: :iiii:--i::ii

_---: ::-i-

:: ---_~:: : :

i-::~i:i-~i.._- -

--..:;E.... ::ii -: . _ : _::::-

-:::iii-: :::::: _- i:

ii-i: ii-~i Q --- '-ii' : -.-i::--::::::-: : ---: ::-:s - - I: :::

..... :?: . i:- : : : - :-...:::.:-_

--~~;~-:i-~-~--:- i

iii-....

_il:- -.

ilii.

ii .:... ii:-a -?:

-i ii ...... ii:-iir i

-::i-iii ii-:iiii

: : ii i:--B

:-i:?i-:-:i : i:iii~::iiiii . iii::-iii:: _--i:iiiiii-ii iiiiii-

?ii- : :: i-_-i:i;:-ii-ii: iiiii-iiiiii~i : i:: i ---- :i-:liii:iiii_:r

:::

:i-iisiii:i :~:::::: ::-:::il

;''-"~~~i:B ~:::-~:i:--~-_ _ :::-:-::

?:: :::: -- :-

::---ii:---:ii-:::-: :--:::-----r:~

-:i::::::-: :-:

-i

:-i-ii

ii:i

:' _i---

i--iii

---:-:

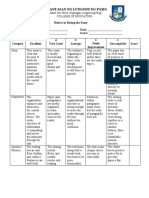

Fig. 1. El Gramillero.

Epic folk poetry, like epic poetry generally, is objective; that is to say,

its contents preexist to the singer. As such, it generally treats historic and

heroic themes which really happened and which have been the object of ex-

clamative commentaries. Hence, epic poetry is narrative poetry, always

reviewing a sequence of events. Such are, for example, the romances.

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

166 NETO: THE CANDOMBE

On the other hand, lyric poetry is subjective, that is, it lives as a

function of the internal world of the poet, foreign to the external events, and

only resorting to the latter for the emotions which they produce in him.

Therefore, it lacks narrative essence. Etymologically, it is poetry which

can be accompanied by music. The rondelet, for example.

In turn, satiric poetry is characterized by making criticism. It differs

from the others by its implicit social intent. With it, the poet subjects his

thematic object, whatever it be-society, man, etc.-to the sieve of his moral,

sharp and biting judgments. The end goal is to unmask, at times in order

to educate. It appears in various folkloric species, above all in the popular

songs and the "mnemonias."

Finally, dramatic poetry is "par excellence" performance. In fact, all

drama is acted out. Therefore, this poetry, named dramatic poetry, is bound

almost always to a play which frequently supports a mixture of dances. Con-

sequently, dramatic dances and "dramatis personae" are elements common to

the general poetic and dramatic folklore.

Mario de Andrade, 1946:49 who created the term, unites, "under the

generic name of dramatic dances, not only the dances which develop a dra-

matic action as such, but also the collective dances which observe the formal

principle of the Suite, that is to say, of a musical work composed of the se-

ries of various choreographic parts, besides obeying a traditional and char-

acterizing theme."

As examples, I cite the taieras, the cucumbis, the caiap6s, the

mo9ambique, the pastoris, the reisados, the cabocolinhos, the marcatu, the

quilombos, etc. of Brazilian folklore. In addition, according to Cdmara

Cascudo, the fandango or marujada, the cheganga, the congo or congada and

the bumba-meu-boi. (Camara Cascudo 1952:393-448.)

More details are discussed in my book on the general theory of poetic

folklore .1

The Candombe or dance of the Lubola masquerade

Now then, the Candombe-an old name--or dance of the Lubola mas-

querade-the new name-is a dramatic dance because it involves a collective

dance with its specific dramatis personae, which develop various choreo-

graphic styles, learned by folkloric transmission through the years. More-

over, in it there survive suggestive mimic dialogues.

Thus, the Candombe of today is not something which came out of nothing,

a creation ex-nihilo of the twentieth century. It is, I repeat, a dramatic

dance with well-defined characters, inherited by social transmission, across

generations and generations of Negroes, and which manifests itself especially

during the carnival.

We are even more convinced of its dramatic essence when going back

to its origins which, according to Arthur Ramos, are the same as those for

the dramatic dance "Congo" or "Congada" in Brazil, which also belongs to

yesterday and today. In other words, the Candombe is the "Congo" of Brazil.

(Ramos 1946:246.) It was called Candombe on the Rio de la Plata whereas

in Brazil it retained the same name as the ethnic group which danced it.

This is to say that the Uruguayan Candombe is an artistic manifestation of

the Congo Negroes living along the Rio de la Plata.

The difficulty in identifying the Candombe at first sight as a variant of

the Congo lies in the profound transformations which it underwent with the

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NETO: THE CANDOMBE 167

passing of the years. While formerly one noted an intimate connection be-

tween the choreography and the characters of both plays-the Uruguayan play

and the Brazilian one-, at the present time, the Saint, the King and Queen

for example have disappeared from the Candombe whereas they live on in

the Congo.

This Candombe, transfigured by its cultural changes, is characterized

nowadays, as we have stated in our investigation of the Montevidean Carnival

to which we referred above, by presenting the following characters: 1) the

Gramillero; 2) the old Negro woman; 3) the Broom maker; 4) the Drummer

and 5) the Trophy Bearer.

Briefly the gramillero (see Fig. 1) is a young dancer, very agile, who

plays the role of an old man, a poor little old man, hump-backed by age,

leaning on his cane. He wears a traditional costume, consisting of a frock

coat, a "buzo," a hat, pants, hose and slippers. For adornment he wears a

beard, glasses and the walking cane already mentioned. He dances from the

feet to the head an entire movement of shakes, doing his "figures," which

are: the "shake," the "small runs" and the "gestures," gestures with the

cane ("rotating" or "pointing") and gestures with the hand or the hat ("salut-

ing"). 2

The old Negro woman, in turn, may also be young and somewhat fat.

She plays the role of companion to the old Negro, or gramillero, or "grand-

father." In noq way is she the companion of the broom maker as the latter

has no companion, but dances only with his broom. Her traditional costume

is the "pollera," the blouse, the skirt and the shawl.

The broom maker is a "malabar" dancer, who is necessarily young,

wearing a tight, unbuttoned jacket, baggy pants, a "cuero," a sash and black

slippers. His "broom" is small, with the straw covered with red cellophane

and the smooth stick is painted red with helicoidal white lines. With it the

"escobero" (see Fig. 3) or even "escobillero" makes equilibrium figures and

rotation figures. The equilibrium figures are: the ear, the nose, the fore-

head, the shoulder, the chest and the fingers. Among the figures of rotation

there is the famous "whirl."

As regards the Drummer and the Trophy Bearer their very names sug-

gest what they are. The former plays his Afro-American instruments-the

small drum, the bells, the piano and the big drum-and the latter carries

his war trophies, the "star," the "half moon," the "flags" and the "banners."

The Drama

Now then, we affirm that the Candombe is a dramatic dance because

these characters act out a story, in other words, a drama whose outlines

and meaning were lost in the night of time, its acting out being in the eyes

of the inexperienced, a dance, a simple dance. But no! Back of this dance

there is something more, which, now, we intend to reconstruct.

Among other things the folkloric song has been lost. And without it,

of course, the dialogue, i.e., the principal key to the plot. De Maria,

Granada, Rossi, etc., although precursors, collected hardly any songs with

the exception of one or another verse, like this one-recorded in passing-

and which is repeated laboriously in the Afro-Uruguayan bibliography:

"calunga, cangue

eee llumbi

eee llumbi" (Maria 1938:82)

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 U76 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

168 NETO: THE CANDOMBE

Ayestaran, searching for them in the memory of old Negro informants,

confirmed De Maria's version and obtained this other piece which was being

sung in the "Court of the Congos," about 1870 (Ayesteran 1953:88):

M LM. L72

Lo an-da Lo an-da Lo an-da ye !

Fig. 2.

With the folkloric song gone-which was the process of magic rein-

forcement and the oral substance of the drama-there remained the dance,

with residues of mimic dialogue.

It continues to be a smooth and free dance which can be danced to the

sound of the drums, high-sounding, insistent and monotonous.

All of the dramatis personae appear at the same time, and what ap-

pears to be a disorderly dance is, in its internal mechanism, an extremely

complex and coordinated dance. A single rhythm with an extraordinary

richness of "passes" or "figures."

The Gramillero does a "shaking movement with the left leg" while the

old Negro woman turns about him at the same time that the Broom maker

exhibits a "whirl" and then does a "nose," at the side of the Gramillero who

"salutes," etc. All this in the lapse of a second, which hardly gives time

for the spectator to orient himself, leaving him dizzy with so much chore-

ographie variety and stirred by the nervousness of the drummers. It is as

if they were all possessed, possessed in a disciplined manner.

I ask myself what mysterious tongue they spoke, what they wanted to

say to each other, without articulated words and ignoring completely the

essence of the motives which led them to these representations.

Today, the gramillero "salutes" addressing himself to the public. But,

formerly, to whom did he address himself? Would this "salute" not be a

fragment of a passage of dialogue with the King or the Queen? Moreover,

he "points" with the cane. To what or to whom does he point? We know

this is not a pantomime which is done in vain. The speech was lost because

its memory stopped talking. But this salute, nevertheless, can indeed be in-

terpreted as a ceremonial permission, also as a signalling gesture, like an

accusation, to the King, of some traitor being present.

On the other hand, to what is due the respect the other characters

lavish on him? Only because he is "old"? Would we not have here an un-

conscious psychological displacement of all of them, which came to consider

him, because he is "old," as a substitute of the King who vanished from the

masquerade? I venture to think so because, almost always, the old men in

the popular plays are the object of satires and criticisms, and this does not

happen to the "old" gramillero of the Afro-Uruguayan play.

In contrast, the broom maker only inspires fear. Nobody comes close

to him during his circumvolutions, brandishing the broom as if it were a

weapon. This fear is now somewhat ambivalent, edged with a mixture of

admiration for his skill and his bravery. Many pay attention to the "cuero"

which he wears around the waist, in front and in back, covering his legs,

as his characteristic costume. And he turns and turns as if to show it off,

making its small broken mirrors--whose significance he himself does not

know--glitter. However, small mirrors of this type, aren't they authentic

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NETO: THE CANDOMBE 169

amulets-in world folklore-of primitive magic, protectors against the enemy,

the evil eye, etc? What then does the broom maker pretend to say with his

agile and dangerous circumvolutions, brandishing a broom as if it was the

"tacape" of the "Caboclo" of the Brazilian "Congada" and protected by a

"cuero" which makes him brave? He can not dance without the "cuero."

One of the broom makers, whom we questioned, frankly confessed that with-

out the "cuero" it is impossible, he does not like it.

.... ....

Fig. 3. El Escobero.

Nowadays the "cuero" is made of fox skin, an animal which incarnates

cunning in various folklores. We are led to think, inclusively, of a totemic

hypothesis under which the psychic identification takes place of the broom

maker with some furry animal whose presence he announces by shaking

large and small bells which are purposely fastened to the "cuero," inter-

mingled with the "small mirrors."

Moreover, the idea of the "cuero" is so powerful that it subsists in

its entirety in those cases in which the broom maker substitutes cloth for

the fox skin or other skins for economic reasons. We saw broom makers

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

170 NETO: THE CANDOMBE

with fox skin and others with cloth. But both, without distinction, said they

wore the "cuero." And a few, to show the difference, told us "cuero" and

"cuero of cloth," they never said simply cloth.

If, the gramillero is grossly respected and the broom maker feared,

the trophy bearer, again grossly, is exalted in glory. The Star, the Half

Moon, the Flags and the Banners are like the live torch of a marathonic

crusade across the centuries. They attest to a past of struggles, as in the

Brazilian "Congada." They are, undoubtedly, a survival of historical disputes

for the hegemony of power among the Negro "nations" or tribes, struggles

which took place in Africa and which were transported to the New World

with the slave traffic. Notwithstanding their general condition of being

slaves, they among themselves, pursued here the historic process started

overseas. Hence many Negroes killed each other, above all in Brazil, with-

out anybody being able to understand the phenomenon. One could not under-

stand the reasons for the self-annihilation of Negroes which occurred in

Brazil in the years 1807, 1809, 1813, 1816, 1826, 1827, 1828, 1830 and 1835.

Today, the studies of Nina Rodriguez and Arthur Ramos have revealed the

causes (Ramos 1946:316; 1948:168-74). These rebellions were, in substance,

"holy wars," provoked by the Islamized Negroes of the Sudan against the

whites, i.e., the Masters, but "also against all the Negroes who did not want

to join the movement." What is certain is that, whether as religious wars

or as political wars, there were left from them the usual trophies.3

Thus, the Star, Flags, Banners, etc., were the very trophies of that

epoch, though they now have a medieval flavor. In mute language, symbolic

and expressive, they testify, in Montevideo, about the struggles, even though

latent ones, entered into by the "nations" of the Congos, Benguelas, Luandas,

Minas and other existing along the Rio de la Plata.

Proofs of these rivalries, perhaps ignored as such, were the "Courts"

existing in Montevideo about the middle and the end of the 19th century.

Documents in the Afro-Uruguayan bibliography reveal that distrusts hung

above them and that they were accused of being "secret" (Pereda Valdds

1941:157). They necessarily had to be secret associations of racial and cul-

tural protectionism against the whites, yes, but also against the other

"Courts" directed by Negroes of other cultures.

This is, at least, the essence of the testimony of the Negro writer

Lino Suarez Peiia in his recollections of the court of the "African Congos,"

located on Ibicui street, corner Soriano, with its King Jose G6mez and Queen

Catalina G6mez; of the "Minas Magis" court, the "Minas Nag6" court, of the

"Banguela," "Lubolos," "Murema," "Angunga" and "Minas Carabori" courts,

all of them with their different locations and different kings (Suarez Pefia

1924).

Even now there survive those trophies which represent in their mute

language the last historic vestiges of remote epochs in which old Africa

possessed ostentatious reigns. One by one, however, the historical elements,

whatever they may be, continue to fall under the action of time, the princi-

pal ally of social dynamics, implacable in the destruction of values which

seemed to be eternal. In Montevideo, there are no longer any Kings, nor

Courts, nor Cults, nor an African language. . . . The epic past of its Negroes

is in agony. We witness it with vivid emotion in the stertors of its defini-

tive disappearance. A few more generations and the crossing of the races

and death will take away the last representative of the race, leaving only the

Afro-Uruguayan studies, i.e., the studies and monographs of those who

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NETO: THE CANDOMBE 171

investigate the truth about the th

terity faithful records of these important moments.

We convinced ourselves even more about this hypothesis concerning the

Afro-Uruguayan dramatic folklore when we considered the recollections of

old Negro informants which we recorded in personal interviews.

It is attested, for example, that although the "courts" disappeared and

were replaced by the "masquerades," that is to say, changed from fixed as-

sociations into mobile associations on the streets, the tensions of hatred

reigning among them survived. Thus, not many years ago, the broom maker

even danced "a la buena" in addition to "al lujo." In dancing "a la buena"

he defended the honor of his masquerade, with an original symbolism which

degenerated into a serious and mortal struggle during the encounter of the

masquerades in the Palermo precinct. These broom makers began with a

"dance counterpoint" doing "tripping tricks" to each other, by means of which

each one of them, dancing on one leg, proceeded to pull the other one to the

ground. And since the loser never resigned himself to defeat, "battle" was

declared between the two entire masquerades, each mortally wounding the

other. One thing they defended with the maximum determination: the "flag,"

that is to say, the standard of the association. For this purpose, it was

surrounded by the "lancers" and the "axemen." The former were on horse-

back carrying their lances, which, even though they were made of brass,

were reinforced with bronze and steel, resembling authentic war lances. In

view of this, when it was possible, the hostile masquerades always managed

mutually to avoid actual struggle, passing by without stopping and without

saluting, that is, with the flags carried back and forth and the drums silent.

They gave their "salutes" only to other friendly masquerades, waving the

flags and the other trophies.

Integration into the Carnival, and Cultural Change

Surely, nowadays it is very difficult to read the dramatic significance

of the candombe, as we did, due to the integration of the latter into the

carnival and its resulting cultural change.

The candombe passed from the "courts" to the "masquerade," i.e.,

from its celebrations on Epiphany it passed to its celebrations on the days

of carnival. In so doing, there was an admixing with cultural groups which

had no African origins but Spanish roots, such as the band of street musi-

cians. On the other hand, it ceased to be an independent entity, forming

part of the "Lubola masquerade" mentioned above, which now comprises

about 70 varied components. We could say that a Lubola masquerade is not

made up of one candombe, but of more than one, since, generally, it is com-

posed of 3 gramilleros, 3 broom makers, 4 or 5 bearers, 5 women dancers,

1 or 2 men dancers, 20 to 25 drummers and chorus singers.

Moreover, the general orientation of the Montevidean carnival is to-

wards the revue types, i.e., theatrical phantasies. This, undoubtedly, also

contributes to obliterating the last vestiges of a popular performance of the

old candombe. This is true to the point that the word candombe has come

to mean also a musical genre, of the kind that any composer can exploit,

composing "candombes" which are recorded, sold and popularized by radio.

Therefore, I repeat, much care is necessary for distinguishing that

which is historic Afro-Uruguayan survival and that which only lives next to

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

172 NETO: THE CANDOMBE

it as a parasite, causing confusion, assimilating the true candombe and al-

lowing itself to be assimilated, with constant interaction which results in a

picturesque and exotic syncretism.

Exploring this syncretism, we would say that the following elements

are now mixed with that initial nucleus of the candombe, deforming it: new

characters, transculturations between whites and Negroes, economic pres-

sures and the revue orientation of the Montevidean carnival.

In fact, at the side of the folkloric nucleus of the masquerade, there

appear also "the female dancer," the "candombera," the "chorus girl" and

the "chorus leader," entirely new characters. The woman dancer in brief

tights and "bandeau" shows her increasing nudity, although at times she ap-

pears in a large costume in showy colors (green, red, yellow, etc.) and

large spangles, arranged here and there. Her shoes are gilt or yellow, var-

ying in color according to the costume. On the head are placed feathers,

which are also colored and, in the hand, a small parasol.

The candombera is also a woman dancer although she is different. She

shows off a costume which may be white in color with green piping and yel-

low embroidery; red belt, sleeveless bodice and a part of the shoulder bare.

Why not recognize that the very presence of these new characters is a

product of white-Negro transculturations? The figure of the naked woman

dancer is a contribution of the whites, imposed against all the resistances

of the "Old Negro women" who consider her an attack upon their large cos-

tumes, adorned with stars, and an argument for the deformed prenotions of

the public about the "sexual disposition" of the Negro race. Vice versa, if

the nudity of the Negro woman referred to is a product of the influences of

the white woman, the love which the white man now demonstrates for the

drum is the product of Negro influences. There were never any white drum-

mers in the past, but there are now. Neither were there whites painted as

Negroes or "lubolos," another example of the "blackening" of the whites.

Now then, "blackening" of the whites and "whitening" of the Negro, in

my opinion, are transculturations which obey economic factors. I disagree

with some national authors who pretend to see them as products of spiritual

effusions, resulting from mysterious appeals of the "tan-tan" of the Africans,

in other words, a product of psychological identification, rhythmic and con-

fraternalizing vibrations. In Brazil, yes, this phenomenon does occur. In-

deed, few Brazilians resist the Negro masses descending from the "hills" to

the street with the samba of their "cuicas" (comic singers), challengers,

drums, chorus, "tamancos" (clogs), flags and general semi-madness. But in

Uruguay, never! The whites who "blacken" themselves in Montevideo are

those who share with the Negroes the same economic situation, living with

them in the tenements and vicinity. To the "offer" which the carnival makes

to them they respond with their "demand." And all of them jointly make

their good money "working" in the most popular festival of the Banda Ori-

ental of our times.

Said transculturations, therefore, are, I repeat, economic products.

They can and must be understood only after the study of the binomial area

versus folklore, in other words, tenement versus candombe.

The tenement is a point of reunion in mass and a natural school for

drummers, broom makers, gramilleros, old Negro women and trophy bearers.

Why do the Negroes of improved social status not "lower" themselves to

enter a masquerade? Because they are removed from it geographically.

And why are they? Because they can afford to be, thanks to the economic

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NETO: THE CANDOMBE 173

factors. Hence, only by exploring more deeply the social life of the tene-

ment will we understand better the cultural change of the candombe. But I

hasten to conclude, unequivocally, that the candombe is an expression of the

productive forces of today's Montevidean society as well as a folkloric sur-

vival.

There should be pointed out right now, however, the contradiction en-

closed by the tenement. That is to say, if it is, to be sure, a factor in the

survivalship of the candombe, it is, at the same time, a factor in its disap-

pearance or death. It defends it and transmits it from generation to gener-

ation, by virtue of the Negroes who live inside its walls, but also transforms

it by virtue of the whites who proceeded to live there, in these last decades,

driven by a growing proletarization.

Finally, the carnival repertory-another consequence of the revue ori-

entation of the Montevidean carnival-is also exerting pressure on the cul-

tural change of the candombe. In fact, just as the actual carnival characters

should not be confused with the dramatis personae of the candombe, the folk-

loric drama should not be confused with the so-called "repertory" of the

Lubola masquerade.

In the repertory of a Lubola masquerade there are, in the order of

their appearance, the Entry, the Animator, the Spectacle, and the Retreat.

As a consequence, under such an obligatory sequence, the nucleus of the

dramatis personae of the drama undergoes a considerable change in function,

losing the spontaneity of its representation in order to subject itself to the

masquerade. It loses its spontaneity altogether during the parade along the

avenues.

In the actual carnival of 1954, the Lubola masquerade marched in re-

view in the following form: Ahead of all of them, the broom makers; then

the bearers with the women dancers in the middle; then the gramilleros and

their old Negro women; behind them the chorus singers, and last, the line

of drummers. They were all "spread apart" from one sidewalk of the street

to the other. It was not so, formerly. According to our informants, the

candombe proper paraded freely. It was common to see the Negroes seated

on the edges of the sidewalks, drinking wine and eating. The old Negro

woman walked together with the gramillero and carried a large basket to

gather fruits from the market and the houses. She said simply "excuse me"

and carried away the fruit.

Conclusions

The candombe is the survival of a dramatic dance with a few of its

dramatis personae still perfectly recognizable but with the drama already

almost imperceptible by virtue of the transformations experienced throughout

the times. Only under the efforts of cultural anthropology can we capture

the silenced language of this drama. The candombe survives by non-

institutionalized and anonymous transmissions and is, at the same time, an

expression of the productive forces of Uruguayan society, which confine it to

the poor area of the tenements. At a certain point, it abandoned its cele-

bration of Epiphany and tied onto the carnival. From then on, its process

of deformation became accentuated with the continuous transculturations

which it experiences, both influencing and being influenced. Nothing can hold

back its social dynamics. We are fortunate in being able to be present at

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

174 NETO: THE CANDOMBE

its final agony, as witnesses to the death of one of the most expressive cul-

tural features of the Uruguayan Negro people.

FOOTNOTES

1. Unpublished. Regarding the characteristics of dramatic dance, see also

Neto 1958.

2. In the drama "Boi dos Reis" in Ceara, Brazil, there are also a velho and

a velha, besides other characters. And the old man in the Ceara version, like the

one in Uruguay, also dances a trembling dance. See Azevedo 1953:47.

3. According to my informants, the "pino" or "chico" drum once had the name

"congo." If that is so, it is more evidence that the candombe is in fact a play of the

Congo Negroes.

REFERENCES CITED

Andrade, Mario de

1946 "As danqas dramaticas do Brasil," Boletin Latino-Americano de Musica

(Rio de Janeiro) 6:49-97.

Ayesteran, Lauro

1953 La misica en el Uruguay, vol. 1. Montevideo: Servicio Oficial de Difusion

Electrica.

Azevedo, Luis Heiror Correa de

1953 Autos tradiconais no Ceara. Rio de Janeiro: Universidade do Brasil, Escola

Nacional de Misica. Publicaq5es do Centro de Pesquisas Folkl6ricas no. 3,

p. 44-51.

Camara Cascudo, Luis da

1952' Literatura oral. Rio de Janeiro: Livraria Jose Olympio Edit6ra (vol. 6 in

the series Hist6ria da Literatura Brasileira).

Maria, Isidoro de

1938 Montevideo antiguo, 2d edition. Montevideo: Edici6n de la Sociedad Amigos

del Libro Rioplatense, vol. 49, 20 tomo.

Neto, Paulo de Carvalho

1958 "La Rua; una danza dramrtica de moros y cristianos en el folklore para-

guayo" in Miscellanea Paul Rivet, octogenario dicata, vol. 2. (Mexico: Uni-

versidad Nacional Aut6noma de Mexico) p. 617-644.

Pereda Vald6s, Ildefonso

1941 Negros esclavos y negros libres; esquema de una sociedad esclavista y

aporte del negro en nuestra formacion nacional. Montevideo.

Ramos, Arthur

1946 As culturas negras no Novo Mundo, 2d edition. Rio de Janeiro: Companhia

Editora Nacional.

1948 "O negro no Brasil: escravidio e hist6ria social" in Estudios de historia de

America (Mexico: Instituto Panamericano de Geografia e Historia), p. 155-

196.

Suarez Pefia, Lino

1924 Apuntes y datos referentes a la raza negra. Montevideo, June 19. Manu-

script in the Biblioteca Pablo Acevedo del Museo Hist6rico Nacional, Monte-

video.

Quito, Ecuador

This content downloaded from

188.26.199.150 on Sun, 27 Nov 2022 12:37:59 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Language VarietyDocument2 pagesLanguage VarietyFatima Aslam100% (2)

- Wire Wrapping Ideas For The Universal Wire Wrapping JigDocument3 pagesWire Wrapping Ideas For The Universal Wire Wrapping JigJS50% (2)

- Third Imperium Issue 4Document20 pagesThird Imperium Issue 4atpollard50% (2)

- An Interview With Kazuo Ishiguro PDFDocument15 pagesAn Interview With Kazuo Ishiguro PDFInés BellesiNo ratings yet

- The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and Modern OblivionDocument219 pagesThe Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and Modern OblivionLheo HR100% (1)

- SM-615 Manual Tecnico ECG 20-32Document443 pagesSM-615 Manual Tecnico ECG 20-32Rouni AñazcoNo ratings yet

- Clock Gear Calculator InstructionsDocument2 pagesClock Gear Calculator InstructionsDaksh Dhingra0% (1)

- Corrective Feedback in Second Language ClassroomsDocument10 pagesCorrective Feedback in Second Language ClassroomsIarisma Chaves100% (1)

- Coast Artillery Journal - Feb 1940Document100 pagesCoast Artillery Journal - Feb 1940CAP History Library100% (2)

- 18 - Hoahoc HuuCo - DangNhuTaiDocument302 pages18 - Hoahoc HuuCo - DangNhuTaibi_hpu2No ratings yet

- Jensen Locust YearsDocument41 pagesJensen Locust Yearstomspy7145100% (3)

- The Maddest Idea: An Isaac Biddlecomb NovelFrom EverandThe Maddest Idea: An Isaac Biddlecomb NovelRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- Sim The-Instrumentalist 1956-10-11 2Document77 pagesSim The-Instrumentalist 1956-10-11 2Paula1412No ratings yet

- Birth of The Classic Guitar and Its Cultivation in Vienna Reflected in The Career and Composition of Mauro Giuliani PDFDocument534 pagesBirth of The Classic Guitar and Its Cultivation in Vienna Reflected in The Career and Composition of Mauro Giuliani PDFMichael Bonnes100% (2)

- FOSTER, Hal. An Art of Missing PartsDocument30 pagesFOSTER, Hal. An Art of Missing PartsjanNo ratings yet

- The Art of HitlerDocument39 pagesThe Art of HitlerLuísa Coimbra100% (1)

- Johannes Ockeghem: Changing Image, Songs & New SourceDocument15 pagesJohannes Ockeghem: Changing Image, Songs & New Sourcetrabajos y tareas urabá100% (1)

- Roger Caillois, Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia, OctoberDocument18 pagesRoger Caillois, Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia, OctobergaNo ratings yet

- Mimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia Author(s) : Roger Caillois and John Shepley Source: October, Winter, 1984, Vol. 31 (Winter, 1984), Pp. 16-32 Published By: The MIT PressDocument18 pagesMimicry and Legendary Psychasthenia Author(s) : Roger Caillois and John Shepley Source: October, Winter, 1984, Vol. 31 (Winter, 1984), Pp. 16-32 Published By: The MIT PressSole PintoNo ratings yet

- The Count of St. Germain: Musical Virtuoso or Mystical FigureDocument16 pagesThe Count of St. Germain: Musical Virtuoso or Mystical FigureAnonymous oCJZ8LSV7BNo ratings yet

- Waddell, Dale - Estimatin The Weight of Tree BolesDocument26 pagesWaddell, Dale - Estimatin The Weight of Tree BolesQvbgr QkhdrNo ratings yet

- Doane - Womans Stake Filming The Female BodyDocument16 pagesDoane - Womans Stake Filming The Female BodyJose Rubens LealNo ratings yet

- Yellow Earth Western Analysis and A Non-Western TextDocument13 pagesYellow Earth Western Analysis and A Non-Western TextvionnaNo ratings yet

- Southeast Asia Program Publications at Cornell UniversityDocument26 pagesSoutheast Asia Program Publications at Cornell UniversityI Gde MikaNo ratings yet

- Adat and Islam Taufik AbdullahDocument26 pagesAdat and Islam Taufik Abdullahhalimatus sa'diyahNo ratings yet

- Anderson and The NovelDocument22 pagesAnderson and The NoveliminthinkermodeNo ratings yet

- ARTHUR C. DANTO Embodied Meanings, Isotypes, and AestheticalDocument10 pagesARTHUR C. DANTO Embodied Meanings, Isotypes, and AestheticalBarbora ŽeleznáNo ratings yet

- Lant. Haptical CinemaDocument30 pagesLant. Haptical CinemaIrene Depetris-ChauvinNo ratings yet

- Powersound00gurngoog PDFDocument571 pagesPowersound00gurngoog PDFApramayNo ratings yet

- Gough, Clenshaw, Pollard - Some Experiments On The Resistance of Metals To Fatigue Under Combined Stresses PDFDocument155 pagesGough, Clenshaw, Pollard - Some Experiments On The Resistance of Metals To Fatigue Under Combined Stresses PDFDavid C HouserNo ratings yet

- Buddha As MusicianDocument10 pagesBuddha As MusicianArastoo MihanNo ratings yet

- Environment Internal AnswerDocument21 pagesEnvironment Internal AnswerkiranNo ratings yet

- Basalla, George - Transformed Utilitarian Objects - Winterthur Portfolio 1982 Vol. 17 Pp. 183-201Document20 pagesBasalla, George - Transformed Utilitarian Objects - Winterthur Portfolio 1982 Vol. 17 Pp. 183-201GerardoNo ratings yet

- Juan Ponce EnrileDocument1 pageJuan Ponce EnrileVERA FilesNo ratings yet

- Clark SM 615 Service ManualDocument20 pagesClark SM 615 Service Manualjames100% (26)

- The Mayans: Vade Mecum, Ventibus AnnisDocument11 pagesThe Mayans: Vade Mecum, Ventibus AnnisOnenessNo ratings yet

- Eigen DarkSpaceEarly 2001Document23 pagesEigen DarkSpaceEarly 2001ValeriaTellezNiemeyerNo ratings yet

- CirqueParadise by Yago García RodríguezDocument40 pagesCirqueParadise by Yago García Rodríguezyaguete1983No ratings yet

- Sex ProblemDocument6 pagesSex ProblemIceblueNo ratings yet

- Closure of Tidal BasinsDocument30 pagesClosure of Tidal BasinsAyman Al HasaarNo ratings yet

- Bent Plates in Violin ConstructionDocument8 pagesBent Plates in Violin ConstructionponbohacopNo ratings yet

- Dwell July-August 2010Document5 pagesDwell July-August 2010DiamondFoamAndFabricNo ratings yet

- Delhi Public School: Neha Ma'Am TeacherDocument13 pagesDelhi Public School: Neha Ma'Am TeacherKhushi JainNo ratings yet

- Acc PG 64 PDFDocument1 pageAcc PG 64 PDFSatyaprasad KNo ratings yet

- Gi in Ihi, CAP L I Glly PL I I: NX PUE A XDocument1 pageGi in Ihi, CAP L I Glly PL I I: NX PUE A Xvo van ducNo ratings yet

- Case - Cirque Du Soleil Can It Burn BrighterDocument8 pagesCase - Cirque Du Soleil Can It Burn BrighterRiju HasanNo ratings yet

- Iffl Oi' Lu-Ll REPUBLIC of INDIA T6246166: S S T6246166 0IND9810282F2906106 0Document1 pageIffl Oi' Lu-Ll REPUBLIC of INDIA T6246166: S S T6246166 0IND9810282F2906106 0Sawant MadhyaNo ratings yet

- D. Talbot Rice 1932 Trebizond A Mediaeval Citadel and PalaceDocument9 pagesD. Talbot Rice 1932 Trebizond A Mediaeval Citadel and PalaceΣπύρος ΑNo ratings yet

- E. Marcel Duchamp The Woolworth Building As ReadymadeDocument12 pagesE. Marcel Duchamp The Woolworth Building As ReadymadeDavid LópezNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 177.12.9.71 On Tue, 19 Mar 2024 00:09:06 +00:00Document23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 177.12.9.71 On Tue, 19 Mar 2024 00:09:06 +00:00MirianMarquesNo ratings yet

- The MIT Press TDR (1988-) : This Content Downloaded From 200.13.105.111 On Thu, 15 Nov 2018 00:25:43 UTCDocument20 pagesThe MIT Press TDR (1988-) : This Content Downloaded From 200.13.105.111 On Thu, 15 Nov 2018 00:25:43 UTCClaudia KaramazovNo ratings yet

- Adrian SisonDocument1 pageAdrian SisonVERA FilesNo ratings yet

- The Astrological Vault of the Camera di Griselda from RoccabiancaDocument38 pagesThe Astrological Vault of the Camera di Griselda from Roccabiancakamblineha0No ratings yet

- Civics CH 2 Sample PaperDocument13 pagesCivics CH 2 Sample PaperKrishna gNo ratings yet

- (October Vol. 45) Eric Michaud and Rosalind Krauss - The Ends of Art According To Beuys (1988) (10.2307 - 779042) - Libgen - LiDocument12 pages(October Vol. 45) Eric Michaud and Rosalind Krauss - The Ends of Art According To Beuys (1988) (10.2307 - 779042) - Libgen - LijkNo ratings yet

- 1453 - 1997 - PVC Coated Nylon AwningsDocument22 pages1453 - 1997 - PVC Coated Nylon AwningsgvsairamchennaiNo ratings yet

- 01 11Document222 pages01 11Steve BarrowNo ratings yet

- 33P PDFDocument31 pages33P PDFد. سامي أبو جهادNo ratings yet

- The Stony Brook Press - Volume 23, Issue 8Document16 pagesThe Stony Brook Press - Volume 23, Issue 8The Stony Brook PressNo ratings yet

- Sydney Boys 2015 Year 10 Maths Yearly & SolutionsDocument48 pagesSydney Boys 2015 Year 10 Maths Yearly & Solutionschloe.paleoNo ratings yet

- O Ii:: It:: Jethouj'ClDocument2 pagesO Ii:: It:: Jethouj'ClSUKANT JHA 19BIT0359No ratings yet

- Work of ArtDocument12 pagesWork of Artd pNo ratings yet

- L : TL ! E: - ( IorllesDocument1 pageL : TL ! E: - ( IorllesGuilhermeBragaNo ratings yet

- Have You Heard a Kangaroo Buzz?: Learn About Animal SoundsFrom EverandHave You Heard a Kangaroo Buzz?: Learn About Animal SoundsNo ratings yet

- La Crítica Musical en Las Modernas Ciencias de La ComunicaciónDocument17 pagesLa Crítica Musical en Las Modernas Ciencias de La ComunicaciónPaula1412No ratings yet

- Journal of Food Science - 2007 - No - Applications of Chitosan For Improvement of Quality and Shelf Life of Foods A ReviewDocument14 pagesJournal of Food Science - 2007 - No - Applications of Chitosan For Improvement of Quality and Shelf Life of Foods A ReviewPaula1412No ratings yet

- Assessing Biofilm Production in StaphylococciDocument10 pagesAssessing Biofilm Production in StaphylococciPaula1412No ratings yet

- E47 FullDocument7 pagesE47 FullPaula1412No ratings yet

- Carbon Dots Emerging Light Emitters ForDocument14 pagesCarbon Dots Emerging Light Emitters ForPaula1412No ratings yet

- Bossa Novanovo Brasil The Significance of Bossa Nova As A Brazilian Popular MusicDocument13 pagesBossa Novanovo Brasil The Significance of Bossa Nova As A Brazilian Popular MusicPaula1412No ratings yet

- Musicalisches OpferDocument67 pagesMusicalisches OpferPaula1412No ratings yet

- Violin 1 Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim String Quartet EPRINTDocument11 pagesViolin 1 Music of Antonio Carlos Jobim String Quartet EPRINTPaula1412No ratings yet

- Estudios Sobre La Obra de Astor PiazzollDocument3 pagesEstudios Sobre La Obra de Astor PiazzollPaula1412No ratings yet

- 965019Document3 pages965019Paula1412No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 176.83.90.165 On Tue, 05 Apr 2022 09:31:01 UTCDocument12 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 176.83.90.165 On Tue, 05 Apr 2022 09:31:01 UTCPaula1412No ratings yet

- Music For Flute and GuitarDocument4 pagesMusic For Flute and GuitarPaula1412No ratings yet

- Discussion On Fisherman and JinneeDocument24 pagesDiscussion On Fisherman and JinneeAdrian Paul ConozaNo ratings yet

- ORACLE UNDO SPACE ANALYSISDocument13 pagesORACLE UNDO SPACE ANALYSISKoushikKc ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 - Free Time and HobbiesDocument3 pagesUnit 4 - Free Time and HobbiesMouhamadou Tidiane SeckNo ratings yet

- Task 3 - Solution To Quadratic ProbingDocument5 pagesTask 3 - Solution To Quadratic ProbingMuhammad Faiz Alam KhanNo ratings yet

- LinuxCBT Security Edition Encompasses 9 Pivotal Security ModulesDocument29 pagesLinuxCBT Security Edition Encompasses 9 Pivotal Security Modulesashutosh1180No ratings yet

- IELTS Pub QuizDocument8 pagesIELTS Pub Quizmadmaxjune17557No ratings yet

- Sim7000G: Emtc/Nb-Iot/Edge ModuleDocument2 pagesSim7000G: Emtc/Nb-Iot/Edge ModuleAnjar PriyatnaNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub Classics of Semiotics 176 200Document25 pagesVdoc - Pub Classics of Semiotics 176 200limberthNo ratings yet

- Roberto ClementeDocument1 pageRoberto Clementeapi-293783723No ratings yet

- Java Programming: Lab Assessment - 5Document45 pagesJava Programming: Lab Assessment - 5Varanasi MounikaNo ratings yet

- Lkc-Fes Y1S3 L1 Ms. Tan Jue XinDocument3 pagesLkc-Fes Y1S3 L1 Ms. Tan Jue XinXin HuiNo ratings yet

- 5rubric in Rating An EssayDocument3 pages5rubric in Rating An EssayAndy GlovaNo ratings yet

- Ishtiaq and Hussain, 2017 PDFDocument12 pagesIshtiaq and Hussain, 2017 PDFMuhammad IshtiaqNo ratings yet

- What Is MongoDB - Introduction, Architecture, Features & ExampleDocument8 pagesWhat Is MongoDB - Introduction, Architecture, Features & Examplejppn33No ratings yet

- Network Monitoring With ZabbixDocument6 pagesNetwork Monitoring With ZabbixGustavo Sánchez CotoNo ratings yet

- Expert Project Manager with 12+ Years ExperienceDocument3 pagesExpert Project Manager with 12+ Years ExperienceAshish SharmaNo ratings yet

- Bennett - Comparative Semitc Linguistics - A ManualDocument284 pagesBennett - Comparative Semitc Linguistics - A ManualdwilmsenNo ratings yet

- Aspen Production Record Manager V9: Release NotesDocument16 pagesAspen Production Record Manager V9: Release Noteszubair1951No ratings yet

- Numerical Methods For Graduate School: JP Bersamina October 11,2018Document67 pagesNumerical Methods For Graduate School: JP Bersamina October 11,2018MARKCHRISTMASNo ratings yet

- EmbeddedsystemDocument64 pagesEmbeddedsystemAby K ThomasNo ratings yet

- A Microprocessor Is One of The Most Exciting Technological InnovationsDocument16 pagesA Microprocessor Is One of The Most Exciting Technological InnovationsTrixieNo ratings yet

- Wangeela YohaannisVOL04 Oromo-1Document446 pagesWangeela YohaannisVOL04 Oromo-1Chala GetaNo ratings yet

- Eigenvalues, Eigenvectors (CDT-28) : April 2020Document11 pagesEigenvalues, Eigenvectors (CDT-28) : April 2020Jorge LeandroNo ratings yet

- B I I B (BIIB) : Curriculum - Vitae DisciplineDocument4 pagesB I I B (BIIB) : Curriculum - Vitae DisciplinechinmayshastryNo ratings yet

- 546 1031 1 SMDocument9 pages546 1031 1 SMRenitaNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of FrequencyDocument6 pagesAdverbs of FrequencyJoana PereiraNo ratings yet

- Everything You Wanted To Know About OpensslDocument10 pagesEverything You Wanted To Know About OpensslnakhomNo ratings yet