Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Efficient Management of Randomised Controlled Trials: Nature or Nurture

Uploaded by

Juan Manuel Fernández LópezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Efficient Management of Randomised Controlled Trials: Nature or Nurture

Uploaded by

Juan Manuel Fernández LópezCopyright:

Available Formats

Education and debate

5 Meldrum M. Departures from the design: the randomized clinical trial in 14 Hart Van Riper to Thomas Francis, January 11, 1954. TF-BLUM, Box 6,

historical perspective, 1946-1970 [dissertation]. Stony Brook: State Folder National Foundation—Van Riper.

University of New York, 1994. 15 Thomas Francis to Harry Weaver, December 29, 1953. TF-BLUM, Box 6,

6 Enders J. Recent advances in the study of poliomyelitis. Medicine Folder National Foundation—Weaver.

1954;33:87-95. 16 Named to direct study on polio vaccine tests. New York Times 1954

7 Thomas Dublin to Hart Van Riper. Predicting poliomyelitis incidence for February 10:16.

the 1954 field trial. Thomas Francis Papers, Bentley Historical Library, 17 School tests set for polio vaccine. New York Times 1954 February 15:25.

University of Michigan, (hereafter TF-BLUM), Box 21, Folder

18 Minutes of the Meeting of Advisory Group on Evaluation of Vaccine

Vaccine—Selection of Counties.

Field Trials, January 11, 1954. TF-BLUM, Box 18, Folder Meeting—New

8 Hart Van Riper to NFIP Staff. Brief background statement for the vaccine

field trial, December 1, 1953. TF-BLUM, Box 18, Folder NFIP—1954. York, January 11, 1954.

9 Carter R. Breakthrough: the saga of Jonas Salk. New York: Trident, 1966. 19 Minutes of the Advisory Committee on Technical Aspects of the

10 New tests on polio to dwarf old ones. New York Times 1953 November Poliomyelitis Field Trials, January 30-31, 1954. TF-BLUM, Box 18, Folder

10:32. Meeting—Atlanta, Advisory Committee, January 30-31, 1954.

11 Hart Van Riper to Carl N Neupert, November 19, 1953. TF-BLUM, Box 20 Thomas Francis, handwritten notes. TF-BLUM, Box 18, Folder Meeting—

18, Folder NFIP—Van Riper. New York, January 11, 1954.

12 Thomas Dublin to Hart Van Riper, Response from state health officers 21 For discussion with Van Riper. Thomas Francis’ typed notes, nd.

regarding selection of field trial areas, December 9, 1953. TF-BLUM, TF-BLUM, Box 18, Folder Meeting—Detroit, February 23-24, 1954.

Folder NFIP—Memos.

13 Stella Barlow to Hart Van Riper, November 16, 1953. TF-BLUM, Box 6,

Folder National Foundation—Van Riper. (Accepted 6 October 1998)

Efficient management of randomised controlled trials:

nature or nurture

Barbara Farrell

Institute of Health A randomised controlled trial sets out to do just one

Sciences, Oxford

OX3 7LF

thing—to discover the truth. Pick up any medical jour- Summary points

Barbara Farrell, nal, and you can read about the need for a good

trial manager randomised clinical trial to answer a burning clinical

Although the scientific validity of a randomised

Barbara.Farrell@ question. A trial that will inform, enhance, and, when

controlled trial is subject to intense scrutiny, the

ndm.ox.ac.uk applicable, change clinical practice. Experienced

actual management of the trial often receives little

research committees prioritise the clinical questions

BMJ 1998;317:1236–9 attention

that need answering to ensure the health of the nation.

They also set guidelines on what constitutes good clini- The knowledge and expertise gained on running

cal practice within a research context.1 Furthermore, earlier trials are not widely disseminated, so new

the scientific and clinical communities ensure that trials are begun from scratch

good scientific modelling is central to trial method-

ology. How a trial actually happens and how the Trials need to be marketed properly to ensure

conclusions that affect clinical practice are arrived at that sufficient numbers of participating centres

are often less prescribed. and patients are recruited

Little is written about the day to day and strategic

management of such trials. There are no clearly For the day to day running of the trial, robust

defined operational models established or any code of systems and procedures must be designed that

practice for managing a randomised controlled trial. are efficient, effective, and flexible (generic models

The apparent lack of recognition for the role of that can be customised)

efficient management in the effective delivery of a trial

needs to be addressed. Randomised controlled trials A trial team is needed for the efficient

need to be managed like any other organisation. Many management of a trial and to ease the burden on

clinical trials fail to deliver because of the lack of a collaborating groups

practical businesslike approach to getting the job done.

Reinventing the wheel alongside a recently appointed coordinator, giving

The past 50 years has produced many successful clini- support and guidance through the setting up phase of

cal trials, which have changed clinical practice. a trial on areas unique to clinical trials. The system can

However, the knowledge and expertise gained on how also offer ongoing advice and aftercare. Courses on

to run those trials have not been widely disseminated. clinical trial management are being developed and will

Again and again, trials are begun from scratch. Often provide training for new and experienced coordina-

there is nothing but the scientific question along with tors. The expertise developed in a clinical trial should

the enthusiasm and commitment of the principal be valued and not lost as a result of a lack of career

investigator to make it happen. structure or a recognised body that could offer

A system of “mentoring” and training is being direction to individual trialists.

developed by the Medical Research Council and

Health Services Research Collaboration to help allevi-

ate needless duplication and provide a network of sup-

What makes a trial happen?

port for trial teams—in effect, a little “nurturing.” In A randomised controlled trial has a basic scientific

mentoring an experienced trial coordinator works methodology. During the long phase of developing a

1236 BMJ VOLUME 317 31 OCTOBER 1998 www.bmj.com

Education and debate

However, when the recruitment target is translated to

Tips for marketing a randomised controlled “Two patients a month from your centre” it becomes a

trial challenge that even a busy clinician can meet. A poster

• Budget for costs of marketing when planning the campaign was mounted putting out this message, and

trial the trial reached its target and delivered on time. In the

• Striking logo and letterhead CLASP (collaborative low-dose aspirin study in

• Editorials or flyers in medical journals pregnancy) trial the strategy used to encourage

• User friendly, attractive, and stylish trial materials recruitment was: “We are already the biggest trial ever.

along with tips to ensure their prominence within CLASP can make a major contribution to the world

centres literature.” The trial sample made the biggest single

• Site visits—meet everyone who is involved, directly contribution to the meta-analyses, more than doubling

or indirectly, in the trial the number of women studied worldwide.

• Targeted poster campaign to encourage recruitment A clinical trial is a very odd commodity to manage

• Regular newsletters distributed to collaborators and and “sell.” It means, in effect, marketing a club—an

other interested people esprit de corps.3 Marketing something as nebulous as

• Collaborators’ meetings that engender a purpose this is difficult, exciting, and challenging. Clinical trials

and esprit de corps—seek opportunities to need to be packaged in such a way that they offer some

“piggy-back” small meetings on to other conferences, a sort of kudos or recognition to those willing to partici-

cost effective method of getting the message to a wider

pate. These aspects of a trial involve delicate,

audience

sometimes controversial, management and marketing

• Incentives or profile raising products—badges,

notepads, pens, certificates of participation skills.

• Partnership with consumer groups—articles in

consumer publications Systems, procedures, and plans

Randomised controlled trials depend on systems,

plans, and procedures. Recruitment, randomisation,

data entry systems, customised filing, and plans for

protocol, it will be customised to suit the question

analysis have to be systematised and systematic. In

being addressed. How the protocol will be put into

order to maintain these systems the trial team and col-

practice on a day to day basis is rarely considered in

laborators need to understand them. The simplest task

any depth until the funding is secured and the clock

has to be taken seriously. Every piece of paper that

starts ticking. Trial management involves lateral think-

comes into a coordinating centre must be logged and

ing, good communication, ethical marketing, and com-

tracked. There needs to be a logical structure,

mon sense. A randomised controlled trial is a huge

documentation, and accountability. A large ran-

investment in time, money, and people. For reviewing

domised trial brings together a variety of disciplines

the literature,2 developing a protocol, applying for

with one aim, to provide reliable evidence. To do this

funding, and designing data collection forms there is

there has to be clear written procedures that can be

lengthy consultation and a considered approach, but

followed by everyone involved and that take into

rarely is this thinking applied to how the trial will actu-

account differing practices and working environments.

ally be managed.

A trial team must be focused. In the CLASP trial

Each trial needs to develop a management

the first version of the follow up form did not ask

blueprint. Setting achievable targets, developing an

whether the women had suffered from eclampsia: team

enthusiastic team, and securing the time and budget to

members working on the document had become side-

make the whole process efficient and deliverable are

tracked by “wouldn’t it be interesting” questions. The

part of that blueprint. Assuming that the scientific and

trial team must never lose sight of the main question

clinical questions have been thoroughly reviewed and

that the trial has attracted funding on the basis of good

science, what are the practical aspects that can lead to

the success or failure of a randomised controlled trial? Systems, procedures, and plans needed in a

clinical trial

Marketing • Computerised systems—customised programs

A trial needs to be marketed. A “mentor” working with • Customised trial documentation—protocol,

a trial coordinator on a trial that was failing to recruit information leaflet, data collection forms

subjects asked a simple question, “How do you identify • Recruitment systems—plans for raising awareness,

simple entry forms, poster campaign

the patients?” The problem turned out to be that gen-

eral practitioners were unaware that the trial was • Randomisation systems—entry forms, telephone

service, randomisation envelopes, fax machines

recruiting patients and needed referrals—an obvious

• Data and patient tracking—Office of National

but not uncommon omission. The trial needed to be

Statistics (Britain), overseas offices of national statistics,

marketed nationally to achieve its target recruitment. in house logging systems, unique patient numbering

Trial fatigue can be a problem. Large sample sizes • Data entry—computer programs, simple data

and long recruitment periods can be overwhelming. collection forms, validation systems

The trial should always try to reflect routine clinical • Analysis plans—timelines for data cleaning,

practice at a local level. When the international stroke validation and close out, programs for analysing

trial had been running for three years it still needed to sample size

recruit a further 6000 patients at a rate of 700 a month. • 24 hour, on call, pager service—human interface

These numbers have no practical meaning for a work- with the collaborative group

ing clinician in a small district general hospital.

BMJ VOLUME 317 31 OCTOBER 1998 www.bmj.com 1237

Education and debate

when tempted to take the opportunity to collect data

on anything and everything. The catch phrase for ran- Key members of the trial team

domised controlled trials of the 1980s and ’90s has • Principal investigator

been “large and simple,” but simplifying everything is • Trial coordinator or manager

not always useful. Too few data can actually miss the

• Trial programmer

answer to the problem being addressed.

• Data manager or clerks

Good quality data are the result of good trial man-

• Trial statistician

agement. Collecting information on a form and enter-

• Trial secretary

ing it onto a computer is simple. However, ensuring

that the data are sensible and reliable is a complicated

and detailed process. Validation and quality control are

crucial. Technology enables us to do this quickly and trial team will depend on the size and design of the trial

efficiently, and trials should be managed whenever and what institution the trial is affiliated to. The trial

possible with the most up to date technology. However, team will often be made up of experienced secretaries,

there must be an interface with people, and systems administrators, and data managers. Initially, they are

must therefore be flexible and bend, within certain unlikely to have any specific knowledge or experience

boundaries, according to the needs of the people par- of what constitutes good clinical trial management.

ticipating in the trial. If there is no flexibility in the sys- Principal investigator—A clinical trial must have a

tems used for collecting, checking, and entering data, leader who is able to command the respect of fellow

the data will be less useful and the end product will be collaborators, other clinicians, and the trial team.3 The

unreliable. principal investigator should show that he or she

values the trial team, be supportive and committed,

and be available to take the lead on clinical or scientific

Communication

issues. However, it is not necessary for this person to be

Information technology has enabled countries

engaged with the day to day running of the trial,

throughout the world to be included in collaborative

although this can bring added value. The principal

research efforts with little extra cost. The telephone has

investigator and the trial coordinator have overall

been used for the past 20 years as the most secure form

responsibility for delivering the trial.

of randomisation and continues to be the most used

Trial coordinator or manager is a key person, respon-

form of communication. Telephone conferencing has

sible for the day to day management of the trial,3

meant much cheaper discussions with collaborators on

although the title for this role is arbitrary. “Administra-

the other side of the world. The most useful communi-

tor” is often used, but it does not reflect the uniqueness

cation tool developed over the past 20 years has been

of the knowledge required. The trial coordinator man-

the fax machine. In a randomised controlled trial

ages all aspects of the trial—marketing, finance, staff

paper is always a problem, and sending it around the

issues, data collection, centre enrolment, and strategic

world by “snail mail” is inefficient, especially to destina-

development of the trial. How do you get a patient

tions where there is no guarantee of its arrival. Email is

“flagged” in Britain? How do you export a drug to

fast becoming the most efficient means of communica-

Thailand? Who will provide a 24 hour randomisation

tion, but its use may be limited in clinical trials, where a

service? These are the sort of questions that face a trial

paper trail is obligatory. We should take the

coordinator on the first day of a new trial. Often trial

opportunity to use up to date technology to pass on

coordinators work in isolation, going through the

not only the scientific information but models that

painful process of developing complicated systems that

have been used to develop and manage successful

have probably been used elsewhere but never written

clinical trials, thereby helping to reduce long and costly

down. There is no manual to use as a reference point.

learning curves.

Trial programmer—A trial needs customised compu-

ter programs. The trial programmer should be

The trial team involved early on in the planning stages, because intri-

Developing a multiskilled enthusiastic trial team is a cate programs take months to develop. Lack of early

long term investment. The size and composition of the input from the programmer can make it necessary to

extend the life of a trial, and this has all sorts of

knock-on effects for budgets and contracts.

Data managers and data clerks work closely with the

trial coordinator in developing systems and getting to

know the participating centres and the data on

individual patients intimately.

Trial statistician—A randomised controlled trial

must have statistical input, but a statistician does not

need to be employed full time. In most cases statistical

input is required during the planning phase, interim

analyses, and final analysis. Therefore, it is possible to

employ a statistician on a consultancy basis. When pos-

sible, it is preferable to use the services of a statistician

in the institution to which the trial is affiliated who

could be available at short notice.

Trial secretary—The value of the trial secretary is

often underestimated. A randomised controlled trial

1238 BMJ VOLUME 317 31 OCTOBER 1998 www.bmj.com

Education and debate

will generate an inordinate number of telephone calls mundane aspects of a trial. Nothing should be too

and mountains of correspondence, mailshots, newslet- much trouble for the trial team: the team should not

ters, faxes, and emails. It is crucial that the secretary is wait for collaborators to ask for help but should be

pleasant and efficient on the telephone and is able to proactive and make life easier for them. Most

prioritise his or her work. importantly, the team should motivate and instil a

Large trials must not produce huge amounts of sense of ownership among the collaborators. This

work for the body of clinicians willing to participate. should lead to swift recruitment and good quality data.

Consequently, this means a great deal of work for the A trial cannot be managed by a committee.

team of the coordinating centre. Efficiency is Although a large randomised trial needs a steering

paramount. The systems and procedures within the committee to give direction on policy, oversee the

coordinating centre must be simple and focused on the professional conduct of the group, and give an

task. Even simply date stamping every piece of paper independent opinion on management matters, it is not

that comes into the trial office has a purpose, and its a substitute for trial management. As trial coordinators

value cannot be overemphasised. A data manager or managers, we should seek to increase the knowledge

working on the long term follow up of a trial should be base from which trials operate. In order to do this we

focused on that particular task and not be distracted by must value our trial management skills, pass on experi-

other needs of the trial office. Members of the trial ence, and develop clinical trial management in a

team need to be familiar with all aspects of the trial but meaningful and professional way.

should have an in depth knowledge of their own area

of work, not only for the trial but for their job satisfac- 1 The Cochrane Library [database on disk and CD ROM]. Cochrane

tion and career development. Collaboration. Oxford: Update Software, 1997. Updated quarterly.

2 UK Medical Research Council. Good clinical practice guidelines for clinical

A group of clinicians come together because they trials. London: UK Medical Research Council, 1998.

want to contribute to the science that forms the basis of 3 Warlow CP. How to do it: Organise a multicentre trial. BMJ 1990;300:

their everyday practice. The trial team needs to nurture 180-3.

the collaborative group by helping with the boring (Accepted 5 October 1998)

Experimentation and social interventions: a forgotten but

important history

Ann Oakley

The research design of the randomised controlled trial Social Science

Research Unit,

is primarily associated today with medicine. It tends Summary points University of

either to be ignored or regarded with suspicion by London Institute of

many in such disciplines as health promotion, public Education, London

Many social scientists argue that randomised WC1H 0NS

policy, social welfare, criminal justice, and education.

controlled trials are inappropriate for evaluating Ann Oakley,

However, all professional interventions in people’s lives professor

social interventions, but they ignore a considerable

are subject to essentially the same questions about a.oakley@ioe.ac.uk

history, mainly in the United States, of the use of

acceptability and effectiveness. As the social reformers

randomised controlled trials to assess different

Sidney and Beatrice Webb pointed out in 1932, there is approaches to public policy and health promotion BMJ 1998;317:1239–42

far more experimentation going on in “the world

sociological laboratory in which we all live” than in any A tradition of experimental sociology was well

other kind of laboratory, but most of this social experi- established by the 1930s, built on the early use of

mentation is “wrapped in secrecy” and thus yields controlled experiments in psychology and

“nothing to science.”1 education

The Webbs argued for a more “scientific” social

policy, with social scientists being trained in experi- From the early 1960s to early 1980s randomised

mental methods and evaluations of social interven- experiments were considered the optimal design

tions being carried out by independent investigators. for evaluating public policy interventions in the

They were apparently unaware that a strong tradition United States, and major evaluations using this

in experimental sociology had already been estab- design were carried out

lished, mainly in the United States. This was a

precursor to a period between the early 1960s and the This approach became less popular as policy

late 1980s when randomised controlled trials became makers reacted negatively to evidence of “near

the ideal for American evaluators assessing a wide zero” effects

range of public policy interventions. This history is

conveniently overlooked by those who contend that Lessons to be learnt about implementing

randomised controlled trials have no place in evaluat- randomised controlled trials in real life settings

ing social interventions. It shows clearly that prospec- include the difficulty of assessing complex

tive experimental studies with random allocation to multi-level interventions and the challenge of

generate one or more control groups is perfectly integrating qualitative data

possible in social settings. Notably, too, the history of

BMJ VOLUME 317 31 OCTOBER 1998 www.bmj.com 1239

You might also like

- Milton Erickson - THE CONFUSION TECHNIQUE PDFDocument10 pagesMilton Erickson - THE CONFUSION TECHNIQUE PDFhitchhiker25100% (1)

- Code of Practice For Design, Installation and Maintenance For Overhead Power LinesDocument19 pagesCode of Practice For Design, Installation and Maintenance For Overhead Power LinesPrashant TrivediNo ratings yet

- Bicycle Engine Kit Installation Guide - Raw 80ccDocument9 pagesBicycle Engine Kit Installation Guide - Raw 80ccSokitome0% (1)

- Understanding Clinical Trials - PDDocument7 pagesUnderstanding Clinical Trials - PDCristina SalcianuNo ratings yet

- 1 - Coating Solutions For Centrifugal Compressor Fouling (LR)Document4 pages1 - Coating Solutions For Centrifugal Compressor Fouling (LR)Mokhammad Fahmi Izdiharrudin100% (1)

- By: Kris Traver and Nitin JainDocument14 pagesBy: Kris Traver and Nitin JainMahesh BhagwatNo ratings yet

- GSM Network SDCCH Congestion & Solutions-16Document15 pagesGSM Network SDCCH Congestion & Solutions-16abdullaaNo ratings yet

- Essential GCP by Prof David Hutchinson 2017Document78 pagesEssential GCP by Prof David Hutchinson 2017Luis Marcas VilaNo ratings yet

- Key Concepts of Clinical Trials A Narrative ReviewDocument12 pagesKey Concepts of Clinical Trials A Narrative ReviewLaura CampañaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 EDITEDDocument38 pagesUnit 5 EDITEDKaye ViolaNo ratings yet

- Phenomenological Research Ethical ConsiderationDocument10 pagesPhenomenological Research Ethical ConsiderationKay Cee RayaNo ratings yet

- Teacher Preparation ProgramDocument30 pagesTeacher Preparation ProgramFarha100% (2)

- Architecture: Passive Design With ClimateDocument39 pagesArchitecture: Passive Design With ClimateamenrareptNo ratings yet

- All Health Researchers Should Begin Their Training by Preparing at Least One Systematic ReviewDocument5 pagesAll Health Researchers Should Begin Their Training by Preparing at Least One Systematic ReviewAhmad GhiffariNo ratings yet

- GCP PDFDocument4 pagesGCP PDFbudiutom8307No ratings yet

- Resumo Tipos EstudoDocument5 pagesResumo Tipos EstudosusanammNo ratings yet

- Artikel RandomizedDocument8 pagesArtikel RandomizedUtari Meria NadaNo ratings yet

- Schramm, W. (1971, December) - Notes On Case Studies of Instructional Mediaprojects. WorkingDocument43 pagesSchramm, W. (1971, December) - Notes On Case Studies of Instructional Mediaprojects. WorkingLuiz CarlosNo ratings yet

- Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2018 - Bhide - A Simplified Guide To Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument8 pagesActa Obstet Gynecol Scand - 2018 - Bhide - A Simplified Guide To Randomized Controlled Trialscogiw65923No ratings yet

- RCT LectureDocument64 pagesRCT LectureAKNTAI002No ratings yet

- Clinical Trial Design Issues at Least 10 Things You Should Look For in Clinical TrialsDocument11 pagesClinical Trial Design Issues at Least 10 Things You Should Look For in Clinical TrialsLuciana OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Case Controls Studies Lancet PDFDocument4 pagesCase Controls Studies Lancet PDFAhira Susana Mendoza de RiveraNo ratings yet

- The Need For Evidence-Based Conservation: Trends in Ecology & Evolution July 2004Document5 pagesThe Need For Evidence-Based Conservation: Trends in Ecology & Evolution July 2004NCPKNo ratings yet

- Art2 - Design - Req, 07 OricDocument7 pagesArt2 - Design - Req, 07 OricAfifa ZeeshanNo ratings yet

- Sessler, Methodology 1, Sources of ErrorDocument9 pagesSessler, Methodology 1, Sources of ErrorMarcia Alvarez ZeballosNo ratings yet

- T C C R C: Raining Ourse For Linical Esearch OordinatorsDocument54 pagesT C C R C: Raining Ourse For Linical Esearch OordinatorsMV FranNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Observational Research Methods. Research Design II Cohort, Cross Sectional, and Case-Control StudiesDocument8 pages2016 - Observational Research Methods. Research Design II Cohort, Cross Sectional, and Case-Control StudiesamarillonoexpectaNo ratings yet

- Reporting Results of Research Involving Human Subjects - An Ethical ObligationDocument3 pagesReporting Results of Research Involving Human Subjects - An Ethical ObligationAlenka TabakovićNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmic Pharmaceutical Clinical Trials: Design ConsiderationsDocument20 pagesOphthalmic Pharmaceutical Clinical Trials: Design ConsiderationsNguyen Minh PhuNo ratings yet

- Contoh ArtikelDocument6 pagesContoh ArtikelMilka Salma SolemanNo ratings yet

- Baack Kukreja, Janet Thompson, Ian M Chapin, Brian F. Organizing A Clinical Trial For The New InvestigatorDocument6 pagesBaack Kukreja, Janet Thompson, Ian M Chapin, Brian F. Organizing A Clinical Trial For The New InvestigatorKarla QuinteroNo ratings yet

- CREDE GCP Beginner Webinar Lecture Notes 2023Document19 pagesCREDE GCP Beginner Webinar Lecture Notes 2023kaylawilliam01No ratings yet

- Factors That Influence Validity (1) : Study Design, Doses and PowerDocument2 pagesFactors That Influence Validity (1) : Study Design, Doses and PowerHabib DawarNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Versus Clinical Reasoning Versus Clinical JudgmentDocument3 pagesCritical Thinking Versus Clinical Reasoning Versus Clinical JudgmentWinda ArfinaNo ratings yet

- Clinical Trials BookDocument11 pagesClinical Trials BookMaria SpatariNo ratings yet

- The Randomized Controlled Trial: Gold Standard, or Merely Standard?Document20 pagesThe Randomized Controlled Trial: Gold Standard, or Merely Standard?ShervieNo ratings yet

- Angell M. The Ethics of Clinical ResearchDocument9 pagesAngell M. The Ethics of Clinical ResearchMaria RivasNo ratings yet

- Lectura 3 - Algoritmo de Movilización Temprana.Document18 pagesLectura 3 - Algoritmo de Movilización Temprana.PilarSolanoPalominoNo ratings yet

- Covid-19 Vaccine Trial Protocols ReleasedDocument2 pagesCovid-19 Vaccine Trial Protocols ReleasedChafik MegherbiNo ratings yet

- Lancet 2002 Schulz Casos y ControlesDocument4 pagesLancet 2002 Schulz Casos y ControlesAndres Suarez UsbeckNo ratings yet

- 2 CREDE GCP Beginner Webinar Lecture Notes 2023Document19 pages2 CREDE GCP Beginner Webinar Lecture Notes 2023kaylawilliam01No ratings yet

- A Short Introduction To Epidemiology 2nd EdDocument152 pagesA Short Introduction To Epidemiology 2nd EdTatiana SirbuNo ratings yet

- 1980.02.28 Policy Statement, Research On Human Subjects, 1980 Hon'ble Justice H.R. Khanna 11pp.Document11 pages1980.02.28 Policy Statement, Research On Human Subjects, 1980 Hon'ble Justice H.R. Khanna 11pp.Sarvadaman OberoiNo ratings yet

- Designing A Cardiology Research Project - Research Questions, Study Designs and Practical ConsiderationsDocument11 pagesDesigning A Cardiology Research Project - Research Questions, Study Designs and Practical ConsiderationsDrSohil ClinicNo ratings yet

- HLTH2024 Research TermsDocument10 pagesHLTH2024 Research TermsCemre KuzeyNo ratings yet

- Essential GCP by Prof David Hutchinson 2017Document78 pagesEssential GCP by Prof David Hutchinson 2017Andrea Violetta ÁcsNo ratings yet

- Quasi-Experimental Design PDFDocument4 pagesQuasi-Experimental Design PDFNino Alic100% (1)

- Scriven - Evaluation of RCT MethodologyDocument14 pagesScriven - Evaluation of RCT MethodologyGastón Andrés CiprianoNo ratings yet

- Decentralizing Research - How Reducing Patient Burden Improves Trial DiversityDocument12 pagesDecentralizing Research - How Reducing Patient Burden Improves Trial DiversitynatjanebNo ratings yet

- Inter Per Ting Clinical TrialsDocument10 pagesInter Per Ting Clinical TrialsJulianaCerqueiraCésarNo ratings yet

- Clinicalresearchfocus: The Research QuestionDocument4 pagesClinicalresearchfocus: The Research QuestionNiputu CintyadewiNo ratings yet

- Fogg and Gross 2000 - Threats To Validity in Randomized Clinical TrialsDocument11 pagesFogg and Gross 2000 - Threats To Validity in Randomized Clinical TrialsChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Development of A Clinical Examination in Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Delphi TechniqueDocument5 pagesDevelopment of A Clinical Examination in Non-Specific Low Back Pain: A Delphi TechniqueVizaNo ratings yet

- The Uses and Abuses of Meta-Analysis: Bruce G CharltonDocument5 pagesThe Uses and Abuses of Meta-Analysis: Bruce G Charltonmaanka aliNo ratings yet

- Current Perspectives: Research in Clinical Reasoning: Past History and Current TrendsDocument10 pagesCurrent Perspectives: Research in Clinical Reasoning: Past History and Current TrendsPablo IgnacioNo ratings yet

- Cohort and Casecontrol StudiesDocument2 pagesCohort and Casecontrol StudiesCitiNo ratings yet

- James 2015Document5 pagesJames 2015Consuelo VegaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Narrative Based Medicine in A Evidence World 1999Document3 pagesArtigo Narrative Based Medicine in A Evidence World 1999antonio campelloNo ratings yet

- Objectives: - Key Points To Remember - ReferencesDocument12 pagesObjectives: - Key Points To Remember - Referencesmunny000No ratings yet

- Examples of Unethical Trials PDFDocument16 pagesExamples of Unethical Trials PDFpatrickNo ratings yet

- Observational Study - WikipediaDocument4 pagesObservational Study - WikipediaDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- Ten Essential Papers For The Practice of Evidencebased MedicineDocument4 pagesTen Essential Papers For The Practice of Evidencebased MedicineAndrieli TodescatoNo ratings yet

- Munroetal FIGOFlexible System Seminars Reprod Med 2011Document10 pagesMunroetal FIGOFlexible System Seminars Reprod Med 2011tadayeNo ratings yet

- Pilot Study What Why HowDocument10 pagesPilot Study What Why Howsiti fatimahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13 - Research in General PracticeDocument16 pagesChapter 13 - Research in General Practiceprofarmah6150No ratings yet

- 2019 Article 3634Document11 pages2019 Article 3634Juan Manuel Fernández LópezNo ratings yet

- 2018 Article 2765Document13 pages2018 Article 2765Juan Manuel Fernández LópezNo ratings yet

- Trial Analytics Ñ A Tool For Clinical Trial Management: GeneralDocument11 pagesTrial Analytics Ñ A Tool For Clinical Trial Management: GeneralJuan Manuel Fernández LópezNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0263786300000181 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S0263786300000181 MainJuan Manuel Fernández LópezNo ratings yet

- Executive SummaryDocument14 pagesExecutive SummarySriharsha Thammishetty100% (1)

- Star Bazaar Koramangala - Google SearchDocument1 pageStar Bazaar Koramangala - Google SearchChris AlphonsoNo ratings yet

- The Current Status of The "Food Security Doctrine" Implementation in The Russian Federation and Tasks For 2013-2020Document5 pagesThe Current Status of The "Food Security Doctrine" Implementation in The Russian Federation and Tasks For 2013-2020gautham28No ratings yet

- Gender Neutrality of Criminal Law in India A Myth or Reality With Special Reference To Criminal Law Amendment Bill 2019Document19 pagesGender Neutrality of Criminal Law in India A Myth or Reality With Special Reference To Criminal Law Amendment Bill 2019AbhiNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 11: The Human Eye and The Colourful WorldDocument23 pagesChapter - 11: The Human Eye and The Colourful WorldVarunveer DubeyNo ratings yet

- System 4 Med G 7831 - PG 85362Document76 pagesSystem 4 Med G 7831 - PG 85362jerimiah_manzonNo ratings yet

- Air Cargo (Assignment 1)Document5 pagesAir Cargo (Assignment 1)Sara khanNo ratings yet

- TRACHEOSTOMYDocument4 pagesTRACHEOSTOMYRheza AltimoNo ratings yet

- 2019 IWA WDCE SriLanka Programme-Book Website PDFDocument75 pages2019 IWA WDCE SriLanka Programme-Book Website PDFPradeep KumaraNo ratings yet

- 2018 - Shiau - Evaluation of A Flipped Classroom Approach To Learning Introductory EpidemiologyDocument9 pages2018 - Shiau - Evaluation of A Flipped Classroom Approach To Learning Introductory EpidemiologySocorro Moreno LunaNo ratings yet

- IcdDocument111 pagesIcdMedical Record RSFMNo ratings yet

- ELL 100 Introduction To Electrical Engineering: L 4: C A Delta - Star TDocument68 pagesELL 100 Introduction To Electrical Engineering: L 4: C A Delta - Star TJesús RomeroNo ratings yet

- Lymph Node - Any of The Small, Oval or Round Bodies, Located Along The Lymphatic VesselsDocument2 pagesLymph Node - Any of The Small, Oval or Round Bodies, Located Along The Lymphatic VesselsKaren ParraNo ratings yet

- Pops Test ResultsDocument3 pagesPops Test Resultsguydennnooo2No ratings yet

- Zool 322 Lecture 2 2019-2020Document24 pagesZool 322 Lecture 2 2019-2020Timothy MutaiNo ratings yet

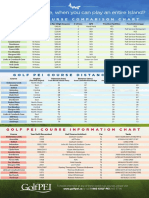

- Golf Pei Course Comparison ChartDocument1 pageGolf Pei Course Comparison ChartSteve DimondNo ratings yet

- KFCDocument41 pagesKFCSumit Kumar100% (1)

- Digi-Flex v. Gripmaster PDFDocument12 pagesDigi-Flex v. Gripmaster PDFMark JaffeNo ratings yet

- Case Study PanajiDocument28 pagesCase Study PanajiKris Kiran100% (1)

- Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004 (Republic Act No. 9262)Document5 pagesAnti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act of 2004 (Republic Act No. 9262)Tobythe BullyNo ratings yet

- Fatty AlcoholsDocument15 pagesFatty AlcoholsUtkarsh MankarNo ratings yet

- Bio 11.1 LE 2 NotesDocument7 pagesBio 11.1 LE 2 NotesCode BlueNo ratings yet

- Till Saxby Electric Pallet Truck Egv 10-12-0240 0242 0300 0302 Workshop ManualDocument22 pagesTill Saxby Electric Pallet Truck Egv 10-12-0240 0242 0300 0302 Workshop Manualmichaelfisher030690fgaNo ratings yet