Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Factors Associated With Quality of Life in Arab Patients With Heart Failure

Uploaded by

شبلي غرايبهOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Factors Associated With Quality of Life in Arab Patients With Heart Failure

Uploaded by

شبلي غرايبهCopyright:

Available Formats

EMPIRICAL STUDIES doi: 10.1111/scs.

12324

Factors associated with quality of life in Arab patients with

heart failure

Fawwaz Alaloul PhD, MPH, RN (Assistant Professor)1, Mohannad E. AbuRuz PhD, RN (Assistant Professor)2,

Debra K. Moser PhD, RN, FAAN (Professor)3, Lynne A. Hall DrPH, RN (Professor)1 and Ahmad Al-Sadi

MSN, RN, CNS (Lecturer)4

1

School of Nursing, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY, USA, 2College of Nursing, Applied Science University, Amman, Jordan, 3College

of Nursing, University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY, USA and 4School of Nursing, University of Hail, Hail, Saudi Arabia

Scand J Caring Sci; 2016 was significantly associated with most QOL domains.

Other social support dimensions were not significantly

Factors associated with quality of life in Arab patients

related to QOL domains. Most patients with heart failure

with heart failure

had significant disrupting pain and limitations in per-

The aim of this study was to examine the relationships forming activities which interfered with their usual role.

of demographic characteristics, medical variables and per- Due to the importance of understanding QOL and its

ceived social support with quality of life (QOL) in Arab determinants within the context of culture, the outcomes

patients with heart failure. A cross-sectional study was of this study may provide valuable guidance to health-

conducted to identify factors associated with QOL in care providers in Arabic countries as well as Western

Arab patients with heart failure. Participants with heart society in caring for these patients. Further studies are

failure (N = 99) were enrolled from a nonprofit hospital needed to explore the relationship between social sup-

and an educational hospital. Data were collected on QOL port and QOL among patients with heart failure in the

using the Short Form-36 survey. Perceived social support Arabic culture.

was measured with the Medical Outcomes Study Social

Support Survey. The majority of the patients reported Keywords: quality of life, heart failure, Arabs, culture,

significant impairment in QOL as evidenced by subscale social support.

scored. Left ventricular ejection fraction was the stron-

gest correlate of most QOL domains. Tangible support Submitted 6 April 2015, Accepted 30 November 2015

Heart failure (HF) affects circulatory, neural and hor- mortality (11) and economic burden (9). A major focus

monal functions resulting in many signs and symptoms of HF treatment is optimisation of QOL (12).

(1). Approximately 5.7 million adults in the United States Identification of factors associated with changes in QOL

had HF in 2008 (2) while 10 million adult had HF in among patients with HF could help in determining

Europe in 2005 (3). In the United States, the number of patients in need of health services (12). Demographic

new cases is 550 000 yearly (4) which costs over $33 bil- characteristics (e.g. age, sex, educational level), medical

lion annually (5). The estimated population in Jordan is factors (e.g. left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF], New

5 611 202. The extrapolated prevalence of HF in Jordan York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class, duration

is 99 021; the estimated incidence is 8251 annually (6). of HF, number of comorbidities) and social factors (e.g.

Patients with HF commonly experience fatigue, dry social support) could influence HF patients’ QOL (12, 13).

mouth, shortness of breath, insomnia, drowsiness, Most of the research to date on the effect of HF on QOL

oedema, depressive symptoms and anxiety (7, 8). Heart was conducted among Western patient populations. Cul-

failure adversely affects all aspects of patients’ physical, ture is important in understanding and facilitating mean-

social, psychological, emotional (9, 10) and economic (8) ing in life in health and in sickness (14). The World

well-being as well as their QOL (8, 9). Poor QOL con- Health Organization Group (15) defined QOL as ‘Individu-

tributes to an increase in hospital admissions, high als’ perception of their position in life in the context of the

culture and value systems in which they live and in rela-

tion to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns’.

Correspondence to: Jordan is an Arabic and Islamic country. Because the

Fawwaz Alaloul, School of Nursing, University of Louisville, 555 S. culture of Arabic and Islamic countries differs in social

Floyd St., K Building, Louisville, KY 40202, USA. structure, religious beliefs and healthcare delivery

E-mail: f0alal02@louisville.edu

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science 1

2 F. Alaloul et al.

systems, outcomes of research conducted in the Western with QOL of adults with HF, (ii) evaluate the relation-

culture may or may not apply to these individuals (16, ships of multiple dimensions of perceived social support

17). Specific characteristics of the Arab Muslim popula- with QOL, and (iii) identify predictors of QOL, given

tion that differ from Western countries include strong demographic and medical variables and dimensions of

family and community relations, abiding faith, reticence social support.

to disclose personal matters in public (18) and male dom-

inance (19). Men in Arabic culture are responsible for

Methods

family members’ safety and supporting them financially.

They are also responsible for making final decisions after

Design, sample and setting

discussion with family members (19, 20). Men in the

Arabic culture do not express their emotions and control A cross-sectional study of 99 outpatients with HF

their responses to maintain their traditional norms of the recruited from a nonprofit hospital and an educational

male role in terms of strength and control (21). Women hospital was conducted. The inclusion criteria were as

integrate and adjust their needs and interests to satisfy all follows: (i) HF diagnosis, (ii) not known to have another

family members’ needs including themselves (22). chronic disease that might affect QOL (e.g. cancer, liver

Islam, whether practiced in the Western countries or failure, kidney failure), (iii) no major psychiatric prob-

Jordan, can have a major impact on an individual’s lems that could interfere with the completion of the

health and involvement with the healthcare system (16). questionnaires or that might affect QOL, and (iv) able to

For example, although Muslims understand the impor- read and write Arabic.

tance of seeking medical treatment, some Muslims may

delay or refuse certain diagnostic tests or be less adherent

Measures

to treatment based on their religious belief in God’s heal-

ing power. Although Muslims with certain illness are SF-36 Survey, Version 2. Quality of life was defined as a

excused from fasting during their Holy month (Rama- multidimensional construct that addresses the physical,

dan), some Arab Muslim patients with HF may prefer to psychological and social aspects of life as perceived by

fast, thus interfering with their treatment schedule. the individuals. It was measured using the Short Form-

Social support has a beneficial effect on a wide range 36 version 2, a 36-item multiple-response option ques-

of health outcomes. Social support reduces mortality tionnaire with eight scales: physical functioning (10

(23), contributes to a healthy lifestyle (24) and improves items), role physical functioning (four items), role emo-

QOL (25). The Arabic and Islamic culture is characterised tional functioning (three items), vitality (four items),

by extended families who provide the individual with mental health (five items), social functioning (two

physical and psychological social support during wellness items), body pain (two items) and general health (five

and illness (18). Families and other relatives in Arabic items) (26). All are measured on a 0–100 scale. Higher

culture make a concerted effort to provide patients with scores indicate better QOL in each domain. Domain

continuous support. According to the beliefs of the Islam scales of the SF-36 were analysed using norm-based scor-

and Arabic culture, individuals should visit and provide ing methods in accordance with the 1998 US general

support to others in times of sickness to get rewards from population. Quality of life domain scores below 47 are

God and meet social obligations (18). Being physically considered below the average general population score

available may or may not provide the patient with the and indicate impairment in this domain (27). This instru-

appropriate support. Examination of the relationships of ment has been translated into Arabic and had satisfactory

a variety of dimensions of social support with QOL in psychometric properties (28). Cronbach’s alphas for the

patients with HF is essential to determine those that are eight scales in this study were: 0.88 for physical function-

most critical for patients’ well-being. ing, 0.94 for role physical, 0.82 for social functioning,

Understanding the factors associated with domains of 0.95 for role emotional, 0.91 for bodily pain, 0.71 for

QOL for patients with HF is important for determining general health, 0.84 for vitality and 0.82 for mental

their needs, developing interventions and evaluating the health.

outcomes of interventions. In addition to improving the

care of Arab Muslims who reside in their country of ori- Medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS). The

gin, findings of this study may have the potential to assist MOS-SSS is a 19-item self-report questionnaire designed

healthcare providers in Western countries, including Eur- to assess perceived social support (29). The first 18 items

ope, to provide appropriate care for Arab Muslim patients form four subscales: emotional/informational support

with HF. The specific aims of this study were to: (i) iden- (eight items), affectionate support (three items), tangible

tify demographic characteristics (age, gender, education support (four items) and positive social interaction (three

level) and medical variables (LVEF, HF duration, pres- items). Respondents indicate how often support is avail-

ence of diabetes mellitus and hypertension) associated able, if needed, on a five-point Likert scale ranging from

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

Factors associated with quality of life 3

1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time). Raw scale MOS-SSS subscale scores. An independent-samples t-test

scores can be standardised by transforming them into a was used to determine if there were differences in the

0–100 scale. Item number 19 measures the availability of QOL domain scores of male and female HF patients. To

people with whom the respondent can do things. Higher identify the potential of multicollinearity among the

scores for the subscales and the overall support index independent variables, the Variance Inflation Factor

indicate a higher level of support (29). The MOS-SSS has (VIF) and tolerance statistics were computed. Stepwise

been tested in a sample of 2987 patients with chronic regression analysis was used to evaluate the strength of

conditions and found to be reliable and valid (29). This association of demographic characteristics (age, gender

instrument was translated into Arabic by the principal and level of education), medical variables (LVEF, dura-

investigator and had good internal consistency in a sam- tion of HF and the presence of hypertension or diabetes)

ple of 63 Arabic stem cell transplant survivors; Cron- and the four social support subscales with each of the

bach’s alphas ranged from 0.79 to 0.87 (30). Cronbach’s eight SF-36 subscales scores.

alphas for the subscales in this study were: 0.88 for tangi-

ble support, 0.88 for emotional–informational support,

Results

0.96 for affectionate support and 0.87 for positive social

interaction support.

Demographic, medical variables, perceived social support and

QOL domains

Demographic and medical characteristics. Data were col-

lected on participants’ age, sex, marital status, educa- A total of 111 patients with HF were assessed to deter-

tional status, employment status and annual income. mine their eligibility for the study. Of these, nine were

Medical variables including time since diagnosis, LVEF not eligible and three patients refused to participate.

and presence of diabetes or hypertension were obtained Ninety-nine patients agreed to participate in this study

from patients’ medical records. and provided written consent. The mean age of the par-

ticipants was 56.9 years (SD = 11.3, range = 29–80).

Other demographic characteristics of the participants are

Procedure

shown in Table 1. The patients’ duration of HF ranged

Institutional ethics committee approval (the equivalent of from 1 to 11 years, with a mean of 3.62 years. Their

institutional review board approval) was obtained from a mean ejection fraction was 37.9% (SD = 5.8,

nonprofit hospital and an educational hospital in Jordan. range = 20–48). Seventy per cent of participants were

The principal investigator met with administrators, physi- hypertensive and 35% were diabetic. Data on perceived

cians and nursing directors to describe the purpose and social support are presented in Table 2. The dimension of

nature of the study. Consecutive HF patients who met the the emotional/informational support had the lowest

inclusion criteria were contacted by two nurse research mean score and the highest was for affectionate support.

assistants during their visit to the outpatient clinic. A The mean scores for the QOL domains are presented in

detailed explanation of the study including the purpose, Table 3. Overall, the patients’ scores were low for all

risks, benefits and procedures was provided to participants

verbally and in written form. Signed, informed consent Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the Arabic patients with

was obtained from patients who agreed to participate. A heart failure (N = 99)

quiet place was provided for participants at the hospital.

Two trained nurse research assistants obtained patient Characteristics n (%)

age, time since diagnosis, LVEF and information about

Gender

other comorbidities (e.g. cancer, liver failure, kidney fail-

Male 64 (64.6)

ure, major psychiatric problems) from patients’ medical

Marital status

records. Data were collected over a 12-month period. Married 85 (85.9)

Divorced/widowed 14 (14.1)

Employment

Data analysis

Employed 37 (37.43)

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Educational level

Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chi- School degree 75 (75.8)

cago, IL, USA). This sample size provided 80% power Diploma 15 (15.2)

based on an alpha of 0.05, 11 independent variables and University degree 9 (9.1)

Annual income

an estimated effect size of 0.2 (31). Alpha was set at

Less than $3500 16 (16.2)

<0.05 for all analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to

$3500–$8600 64 (64.6)

describe the demographic and medical characteristics of More than $8600 19 (19.2)

the sample, the eight domains of the SF-36, and the

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

4 F. Alaloul et al.

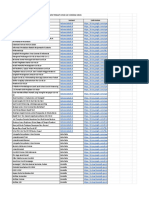

Table 2 Medical outcomes study social support survey scores of the Table 4 Stepwise regression analyses for predictors of the SF-36

Arabic patients with heart failure (N = 99)a subscale scores (N = 99)

Possible Actual Standardised

Scale/subscale Mean SD range range Outcomes/predictors b t Model statistics

Emotional/information 65.0 19.8 0–100 6.3–100 Physical functioning

support Age 0.29 3.17**

Tangible support 81.6 23.4 0–100 6.3–100 Male gender 0.31 3.57**

Affectionate support 86.3 23.2 0–100 0–100 LVEF 0.27 2.98**

Positive social interaction 75.4 22.4 0–100 0–100 Tangible support 0.21 2.34* R2 = 0.38;

Total score 73.8 18.1 0–100 15.8–100 F(4,98) = 14.68,

a

p < 0.001

A higher score indicates greater social support.

Role physical

Age 0.22 0.2.36*

Male gender 0.20 2.22*

Table 3 Scores for the SF-36 quality of life domains of the partici- LVEF 0.30 3.19**

pants (N = 99)a Tangible support 0.30 3.26** R2 = 0.34;

F(4,98) = 12.27,

Possible Actual p < 0.001

Scale/subscale Mean SD range range Bodily pain

Male gender 0.20 2.20*

Physical functioning (level of 38.9 23.7 0–100 0–90

LVEF 0.34 3.67**

limitation in physical activities)

Tangible support 0.33 3.70** R2 = 0.27;

Role physical (problems with 36.4 24.6 0–100 0–100

F(3,98) = 11.63,

usual role related to

p < 0.001

physical health)

General health perception

Social functioning (interference 42.8 25.2 0–100 0–100

LVEF 0.27 2.81**

with social activities)

Presence of 0.23 2.40* R2 = 0.14;

Role emotional (problems with 42.3 26.5 0–100 0–100

diabetes F(2,98) = 7.87,

usual role related to

p < 0.001

emotional health)

Vitality

Bodily pain (level of pain) 37.9 21.9 0–100 0–100

LVEF 0.32 3.54**

General health (general 40.8 15.1 0–100 5–95

Tangible support 0.38 4.14** R2 = 0.21;

perception about health)

F(2,98) = 13.09,

Vitality (energy and fatigue) 34.8 19.7 0–100 0–81

p < 0.001

Mental health (level of 47.2 17.3 0–100 0–90

Social functioning

psychological status)

LVEF 0.35 3.87**

a

A higher score indicates better quality of life. Presence of 0.28 3.02**

diabetes

Presence of 0.21 2.23*

domains indicating poor QOL. The lowest mean score hypertension

was for vitality (i.e. lack of energy and presence of fati- Tangible support 0.20 2.19* R2 = 0.27;

gue), whereas their mental health score was the highest. F(4,98) = 8.52,

The patients reported problems with carrying out their p < 0.001

usual role due to poor physical health, significant bodily Role emotional

pain and limitations performing role activities. Education 0.27 2.87**

LVEF 0.26 2.74** R2 = 0.17;

F(2,98) = 9.91,

Multivariate analyses p < 0.001

Multicollinearity was not a problem as VIF values were *p < 0.05.

less than three (32). The findings of the stepwise regres- **p < 0.01.

sion analyses are presented in Table 4. LVEF was a signif- LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction.

icant independent variable for all of the QOL subscales

except mental health. Presence of diabetes mellitus was and social functioning. Female sex was negatively associ-

associated with low general health perception and low ated with physical functioning, role physical and bodily

social functioning QOL domain scores. Tangible support pain. Those who were younger and had less tangible sup-

was a significant independent variable for the subscales port had better physical functioning. These variables

of physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, vitality accounted for the greatest amount of variance in all of

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

Factors associated with quality of life 5

the SF-36 subscales. The independent variables explained of purifying their sin, and consequently may interfere

the least amount of variance for role emotional and gen- with their seeking pain management (38, 44). For that

eral health perception. reason, it is important for healthcare providers to pay

more attention to pain assessment and management

among Arab patients.

Discussion

This study also examined the demographic and medical

Heart failure has a negative impact on patients’ QOL, variables associated with QOL in Arab patients with HF.

which may lead to increased healthcare demands and The most interesting finding was that LVEF was the

expenses and contribute to an increase in mortality (9, strongest correlate of QOL among Arab patients with HF;

12). Because one goal of HF treatment is optimising however, this finding is contrary to previous research

QOL, it is important to understand QOL and its determi- (13, 36, 37). Low LVEF, which is an objective clinical

nants within the context of culture to assess patient measurement of HF, leads to fluid accumulation in lungs

needs and improve QOL. In this study, we aimed to and lower limbs resulting in fatigue and dyspnoea (45).

understand the impact of different factors on Arab Mus- Previous studies showed that LVEF is a strong predictor

lim HF patients’ QOL. We attempted to understand the of mortality (46, 47) and hospital admissions (48) but

impact of these factors within the context of Arab Mus- not QOL. Effective management of LVEF might improve

lim culture based on the literature. patients’ QOL, reduce mortality rate and decrease hospi-

Most of the Arab patients with HF participating in this talisation admission. Different pharmacological (49) and

study reported poor QOL in all domains. They reported nonpharmacological modalities such as implantable car-

significant disruptive pain and fatigue, interference with dioverter defibrillator, cardiac resynchronisation therapy

social activities, impaired psychological status, and limita- or myocardial revascularisation can be used to improve

tions performing activities associated with their usual LVEF (49, 50). In addition to the disease process, culture

role. Similarly, Turkish patients with HF reported impair- may negatively affect LVEF. Although seeking medical

ment in QOL (33). In other studies conducted in Western treatment is considered important in Islam, some Arab

countries (Germany and Sweden) (13, 34) and in Brazil Muslim HF patients may not adhere to their diagnostic

(35), social functioning, role emotional and mental procedure or HF treatment regimen based on their belief

health were slightly impaired among patients with HF. in God’s healing power. Poor adherence may intensify

Mental health and pain QOL domains were slightly com- symptoms and impact disease progression (51). Nurses

promised among patients with HF from the Netherlands are in a unique position to play a major role in educating

(36). Cultural or healthcare system issues are potential patients from different cultures about the importance of

explanations for these differences in emotional, mental, treatment adherence.

social and pain QOL domains scores in the current sam- Another interesting finding was that none of the vari-

ple compared to samples from other countries (37). Arabs ables in this study was associated with mental health.

prefer not to disclose their emotions during illness in Diabetes mellitus was associated with general health per-

public (38) and thus, may avoid seeking emotional and ception and social functioning QOL domains. This finding

social help from healthcare providers (39). Therefore, is consistent with previous studies (52, 53). These results

emotional and social issues should be addressed directly may signify the importance of collaboration among

by healthcare providers, not waiting for patients to bring health providers in the planning of care for patients with

them up. Among this sample of Arabs with HF, the great- HF. The role of the primary care specialist is not well

est impairment in QOL was in vitality. The patients established in Jordan (54). Availability of these health-

reported severe fatigue and lack of energy which is con- care providers may help in coordinating the care of

sistent with the common clinical manifestations of HF. patients with HF across the care system.

Further studies are needed to explore the differences in Being older and female were associated with poorer

QOL among different cultures. QOL. Older age is associated with poor physical and role

Inconsistent findings on the pain domain of QOL were physical QOL domains. The findings were inconsistent in

found in prior HF studies. In the current study and some prior studies conducted in the Western culture (11, 55).

previous studies (40, 41), the pain QOL domain was In this sample, the association between age and QOL

impaired while in other studies (35, 42) the pain domain could be due to the adverse changes that occur with age-

was not significantly compromised. Differences in patient ing and limited resources available for them. Arab

perception and expression of pain might be related to women with HF were more impaired in the physical, role

many physical, psychosocial, cognitive, behavioural, spir- physical and bodily pain QOL domains than Arab men.

itual, religious and cultural factors (43). In the present Conflicting findings regarding the relationship between

study, the Arabic and Islamic culture may have effected sex and QOL were found among studies conducted in

patients’ expression of pain. For Arab patients, pain is the Western culture (13, 55, 56). In addition to the phys-

part of their chronic illness and may be viewed as a way iological differences (57), a possible explanation for

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

6 F. Alaloul et al.

higher QOL among Arab men is that men in the Arabic to optimising QOL within the context of culture as a

and Islamic culture try to suppress their feelings to main- major focus of HF treatment. One of the more signifi-

tain their gender role in the community and show their cant findings was that LVEF had the strongest relation-

control over the negative consequences of HF (21). Due ship with QOL among Arab patients with HF. Effective

to the significant role of Arab Muslim women in the fam- management of LVEF using pharmacological and non-

ily dynamics, women try to integrate and adjust their pharmacological interventions may improve QOL among

physical and psychological needs and interests to satisfy this population. Expansion of the role of the primary

all family members’ needs including themselves (22). care specialist is important to provide comprehensive

Another aim of this study was to describe the associa- care for patients with chronic diseases. Nurses and other

tion of perceived social support with QOL among Arab healthcare providers may need to support Arab patients

patients with HF. In this study, patients reported that in general and male patients specifically to express their

they received a moderate to high level of social support. feelings so that their needs can be identified. Further

This level of perceived support is consistent with previous investigation of the relationship between perceived

studies conducted in the United States and Turkey (25, social support and QOL among Arab and Western

58). Turkish HF patients mainly received social support patients with HF is warranted. While we expect our

from their families (25). Patients in the present study findings are relevant to Arab Muslim patients with HF

who received more tangible support had lower scores on currently living in Western countries, future research

the domains of physical functioning, role physical, bodily should focus specifically on understanding the experi-

pain, vitality and social functioning. This is not surprising ence of Arab Muslim with HF residing in Western

since Arab patients with these compromised domains due countries.

to the disease process and treatment complexity were

more in need of tangible support (17). Other social sup-

Author contribution

port subscales were not significantly related to QOL

domains. The few studies that examined the relationship Fawwaz Alaloul, PhD, MPH, RN; Mohannad E. AbuRuz,

between social support and QOL among HF patients PhD, RN; Debra K. Moser, DNSc, RN, FAAN; Lynne A.

yielded, inconsistent findings (25, 58). The inconsisten- Hall, DrPH, RN; and Ahmad Al-Sadi, MSN, RN, involved

cies in the current study and previous studies may be in study conception and design. Fawwaz Alaloul, PhD,

due to the use of different instruments to measure social MPH, RN, and Ahmad Al-Sadi, MSN, RN, involved in

support and QOL (58). Further studies are needed to acquisition of data. Fawwaz Alaloul, PhD, MPH, RN;

explore the relationship between social support and QOL Mohannad E. AbuRuz, PhD, RN; Debra K. Moser, DNSc,

among patients with HF in the Arabic and Islamic RN, FAAN; and Lynne A. Hall, DrPH, RN, involved in

culture. analysis and interpretation of data. Fawwaz Alaloul, PhD,

The cross-sectional nature of this study limits causal MPH, RN; Mohannad E. AbuRuz, PhD, RN; Debra K.

inferences and is a weakness in terms of understanding Moser, DNSc, RN, FAAN; and Lynne A. Hall, DrPH, RN,

factors that affect HF patients’ QOL over time. In this involved in drafting of the manuscript.

study, data on physical and depressive symptoms were

not collected. Arab community values discourage the

Ethical approval

expression of depression and other mental issues out-

side the family. Further studies are needed to explore Institutional ethics committee approval (the equivalent of

the influence of these factors on QOL in this institutional review board approval) was obtained from

population. the two hospitals and the Hashemite University in

Jordan.

Conclusions

Funding

This study addressed QOL in Arab patients with HF and

showed that most Arab patients with HF reported poor Financial support for this research was provided by the

QOL. Healthcare providers need to pay more attention Hashemite University.

References failure. J Eval Clin Pract 2006; 12: report from the American Heart

334–40. Association. Circulation 2012; 125:

1 Dobre D, van Jaarsveld CH, Ranchor 2 Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, e2–220.

AV, Arnold R, de Jongste MJ, Haai- Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, 3 Jaarsma T, Stromberg A, De Geest S,

jer Ruskamp FM. Evidence-based . . . Turner MB. Heart disease and Fridlund B, Heikkila J, Martensson J,

treatment and quality of life in heart stroke statistics – 2012 update: a Moons P, Scholte op Reimer W,

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

Factors associated with quality of life 7

Smith K, Stewart S, Thompson DR. and provider-related determinants of social ties in relation to subsequent

Heart failure management pro- generic and specific health-related total and cause-specific mortality and

grammes in Europe. Eur J Cardiovasc quality of life of patients with coronary heart disease incidence in

Nurs. 2006; 5: 197–205. chronic systolic heart failure in pri- men. Am J Epidemiol 2002; 155: 700–

4 Martin M, Blaisdell-Gross B, Fortin mary care: a cross-sectional study. 9.

EW, Maruish ME, Manocchia M, Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010; 8: 98. 24 Pirie PL, Rooney BL, Pechacek TF,

Sun X, . . . Ware JE. Health-related doi:10.1186/1477-7525-8-98-108. Lando HA, Schmid LA. Incorporating

quality of life of heart failure and 14 Padilla GV, Kagawa-Singer M, Ash- social support into a community-

coronary artery disease patients ing-Giwa T. Quality of life, health wide smoking-cessation contest.

improved during participation in dis- and culture. In Quality of Life from Addict Behav 1997; 22: 131–7.

ease management programs: a longi- Nursing and Patient Perspectives. (King 25 Barutcu CD, Mert H. The relation-

tudinal observational study. Dis GL, Hinds PS eds), 2012, Jones and ship between social support and

Manag 2007; 10: 164–78. Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, MA, quality of life in patients with heart

5 Smith DH, Johnson ES, Blough DK, 105–35. failure. J Pak Med Assoc 2013; 63:

Thorp ML, Yang X, Petrik AF, Cris- 15 The World Health Organization 463–7.

pell KA. Predicting costs of care in Group. The World Health Organiza- 26 Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS

heart failure patients. BMC Health tion quality of life assessment (WHO- 36-item Short-Form Health Survey

Serv Res 2012; 12: 434. QOL): position paper from the World (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework

6 Health Grades Inc. Statistics by Country Health Organization. Soc Sci Med and item selection. Med Care 1992;

for Congestive Heart Failure. 2012, 1995; 41: 1403–9. 30: 473–83.

http://cureresearch.com/c/congestive 16 Silbermann M, Hassan EA. Cultural 27 Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB,

_heart_failure/stats-country.htm (last perspectives in cancer care: impact of Turner-Bowker DM, Gandek B,

accessed 8 December 2012). Islamic traditions and practices in Maruish ME. SF-36v2â Health Survey:

7 Heo S, Doering LV, Widener J, Middle Eastern countries. J Pediatr Administration guide for Clinical Trial

Moser DK. Predictors and effect of Hematol Oncol 2011; 33(Suppl 2): Investigators. 2008, QualityMetric

physical symptom status on health- S81–6. Incorporated, Lincoln, RI.

related quality of life in patients with 17 Tajvar M, Fletcher A, Grundy E, 28 Coons SJ, Alabdulmohsin SA, Drau-

heart failure. Am J Crit Care 2008; Arab M. Social support and health of galis JR, Hays RD. Reliability of an

17: 124–32. older people in Middle Eastern coun- Arabic version of the RAND-36

8 Heo S, Lennie TA, Okoli C, Moser tries: a systematic review. Australas J Health Survey and its equivalence to

DK. Quality of life in patients with Ageing 2013; 32: 71–78. the US-English version. Med Care

heart failure: ask the patients. Heart 18 Wehbe-Alamah H. Bridging generic 1998; 36: 428–32.

Lung 2009; 38: 100–8. and professional care practices for 29 Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The

9 Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Zam- Muslim patients through use of Lei- MOS social support survey. Soc Sci

broski CH, Chung ML. A comparison ninger’s culture care modes. Contemp Med 1991; 32: 705–14.

of health-related quality of life Nurse 2008; 28: 83–97. 30 Alaloul, F. Examination of the validity

between older adults with heart fail- 19 al-Krenawi A, Graham JR. Culturally of the Arabic version of the Medical Out-

ure and healthy older adults. Heart sensitive social work practice with come Study (MOS) Social Support Survey

Lung 2007; 36: 16–24. Arab clients in mental health settings. using confirmatory factor analysis. (Mas-

10 Chen HM, Clark AP, Tsai LM, Lin Health Soc Work 2000; 25: 9–22. ter Thesis), 2007, University of Ken-

CC. Self-reported health-related 20 Saca-Hazboun H, Glennon CA. Cul- tucky, Lexington.

quality of life and sleep disturbances tural influences on health care in 31 Soper DS. A-priori Sample Size Calcula-

in Taiwanese people with heart fail- Palestine. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2011; 15: tor for Multiple Regression [Software].

ure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010; 25: 503– 281–6. 2015, http://www.danielsoper.com/

13. 21 Vogel DL, Heimerdinger-Edwards SR, statcalc (last accessed 8 January

11 Iqbal J, Francis L, Reid J, Murray S, Hammer JH, Hubbard A. “Boys don’t 2015).

Denvir M. Quality of life in patients cry”: examination of the links 32 Shieh G. Clarifying the role of mean

with chronic heart failure and their between endorsement of masculine centring in multicollinearity of inter-

carers: a 3-year follow-up study norms, self-stigma, and help-seeking action effects. Br J Math Stat Psychol

assessing hospitalization and mortal- attitudes for men from diverse back- 2011; 64: 462–77.

ity. Eur J Heart Fail 2010; 12: 1002–8. grounds. J Couns Psychol 2011; 58: 33 Demir M, Unsar S. Assessment of

12 Son YJ, Song Y, Nam S, Shin WY, 368–82. quality of life and activities of daily

Lee SJ, Jin DK. Factors associated 22 Joseph S. Gender and Family in the living in Turkish patients with heart

with health-related quality of life in Arab World. In Arab Women: Between failure. Int J Nurs Pract 2011; 17:

elderly Korean patients with heart Defiance and Restraint. (Sabbah S ed), 607–14.

failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012; 27: 1996, Olive Branch Press, New York, 34 Ekman I, Fagerberg B, Lundman B.

528–38. 194–202. Health-related quality of life and

13 Peters-Klimm F, Kunz CU, Laux G, 23 Eng PM, Rimm EB, Fitzmaurice G, sense of coherence among elderly

Szecsenyi J, Muller-Tasch T. Patient- Kawachi I. Social ties and change in patients with severe chronic heart

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

8 F. Alaloul et al.

failure in comparison with healthy Minnesota Living with Heart Failure comparison of techniques. Am Heart

controls. Heart Lung 2002; 31: 94– Questionnaire (MLHF-Q). [Validation Hosp J 2011; 9: 107–11.

101. Studies]. Clin Rehabil 2001; 15: 489– 51 Stamp KD. Women with heart fail-

35 Saccomann IC, Cintra FA, Gallani 500. ure: do they require a special

MC. Health-related quality of life 43 Goodlin SJ, Wingate S, Pressler SJ, approach for improving adherence to

among the elderly with heart failure: Teerlink JR, Storey CP. Investigating self-care? Curr Heart Fail Rep 2014;

a generic measurement. Sao Paulo pain in heart failure patients: ratio- 11: 307–13.

Med J 2010; 128: 192–6. nale and design of the Pain Assess- 52 Fotos NV, Giakoumidakis K, Kollia Z,

36 Hoekstra T, Lesman-Leegte I, van ment, Incidence & Nature in Heart Galanis P, Copanitsanou P, Pananou-

Veldhuisen DJ, Sanderman R, Failure (PAIN-HF) study. J Cardiac daki E, . . . Hero B. Health-related

Jaarsma T. Quality of life is impaired Fail 2008; 14: 276–82. quality of life of patients with severe

similarly in heart failure patients 44 Van den Branden S, Broeckaert B. heart failure. A cross-sectional multi-

with preserved and reduced ejection Necessary interventions: Muslim centre study. Scand J Caring Sci 2012;

fraction. Eur J Heart Fail 2011; 13: views on pain and symptom control 27: 686–94.

1013–8. in English Sunni e-Fatwas. Ethical 53 Franzen K, Saveman BI, Blomqvist

37 Huang TY, Moser DK, Hwang SL, Perspect 2010; 17: 626–51. K. Predictors for health related qual-

Lennie TA, Chung M, Heo S. Com- 45 King M, Kingery J, Casey B. Diag- ity of life in persons 65 years or

parison of health-related quality of nosis and evaluation of heart fail- older with chronic heart failure. Eur

life between American and Tai- ure. Am Fam Physician 2012; 85: J Cardiovasc Nurs 2007; 6: 112–20.

wanese heart failure patients. J Tran- 1161–8. 54 Barghouti F, Halaseh L, Said T,

scult Nurs 2010; 21: 212–9. 46 Rizzello V, Poldermans D, Biagini E, Mousa AH, Dabdoub A. Evidence-

38 Hollins S. Religions, Culture, and Schinkel AF, Elhendy A, Leone AM, based medicine among Jordanian

Healthcare: A Practical Handbook for . . . Bax JJ. Relation of improvement family physicians: awareness, atti-

Use in Healthcare Environments. 2009, in left ventricular ejection fraction tude, and knowledge. Can Fam Physi-

Radcliffe Publishing, Oxford; New versus improvement in heart failure cian 2009; 55: e6–13.

York. symptoms after coronary revascular- 55 Lewis EF, Lamas GA, O’Meara E,

39 Al-Busaidi ZQ. A qualitative study ization in patients with ischemic car- Granger CB, Dunlap ME, McKelvie

on the attitudes and beliefs towards diomyopathy. Am J Cardiol 2005; 96: RS, . . . Pfeffer MA. Characterization

help seeking for emotional distress in 386–9. of health-related quality of life in

Omani women and Omani general 47 Solomon SD, Anavekar N, Skali H, heart failure patients with preserved

practitioners: implications for post- McMurray JJ, Swedberg K, Yusuf S, versus low ejection fraction in

graduate training. Oman Med J 2010; . . . Pfeffer MA. Influence of ejection CHARM. Eur J Heart Fail 2007; 9:

25: 190–8. fraction on cardiovascular outcomes 83–91.

40 Rustoen T, Stubhaug A, Eidsmo I, in a broad spectrum of heart failure 56 Rector TS, Anand IS, Cohn JN. Rela-

Westheim A, Paul SM, Miaskowski C. patients. Circulation 2005; 112: 3738– tionships between clinical assess-

Pain and quality of life in hospitalized 44. ments and patients’ perceptions of

patients with heart failure. J Pain 48 Chaudhry SI, McAvay G, Chen S, the effects of heart failure on their

Symptom Manage 2008; 36: 497–504. Whitson H, Newman AB, Krumholz quality of life. J Cardiac Fail 2006;

41 Spiraki C, Kaitelidou D, Papakon- HM, Gill T. Risk factors for hospital 12: 87–92.

stantinou V, Prezerakos P, Mani- admission among older persons with 57 Bennett SJ, Perkins SM, Lane KA,

adakis N. Health-related quality of newly diagnosed heart failure: find- Deer M, Brater DC, Murray MD.

life measurement in patients admit- ings from the Cardiovascular Health Social support and health-related

ted with coronary heart disease and Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61: quality of life in chronic heart failure

heart failure to a cardiology depart- 635–42. patients. Qual Life Res 2001; 10: 671–

ment of a secondary urban hospital 49 Bartos JA, Francis GS. The high-risk 82.

in Greece. Hellenic J Cardiol 2008; 49: patient with heart failure with 58 Heo S, Moser DK, Chung ML, Len-

241–7. reduced ejection fraction: treatment nie TA. Social status, health-related

42 Middel B, Bouma J, de Jongste M, options and challenges. [Review]. quality of life, and event-free sur-

van Sonderen E, Niemeijer MG, Cri- Clin Pharmacol Ther 2013; 94: 509–18. vival in patients with heart fail-

jns H, . . . van den Heuvel W. Psy- 50 Kireyev D, Adib K, Pohl KK, Khalil ure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012; 11:

chometric properties of the M, Wilson MF. Viability studies- 141–9.

© 2016 Nordic College of Caring Science

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Bulle: Support and Prevention of Psychological Decompensation of Health Care Workers During The Trauma of The COVID-19 EpidemicDocument7 pagesThe Bulle: Support and Prevention of Psychological Decompensation of Health Care Workers During The Trauma of The COVID-19 Epidemicشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice Behaviour of Midwives Concerning Periodontal Health of Pregnant PatientsDocument18 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes and Practice Behaviour of Midwives Concerning Periodontal Health of Pregnant Patientsشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Secondary School Students Toward COVID-19 Epidemic in Italy: A Cross Selectional StudyDocument11 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Practice of Secondary School Students Toward COVID-19 Epidemic in Italy: A Cross Selectional Studyشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Cross-Sectional Study: Comparing The Attitude and Knowledge of Medical and Non-Medical Students Toward 2019 Novel CoronavirusDocument5 pagesA Cross-Sectional Study: Comparing The Attitude and Knowledge of Medical and Non-Medical Students Toward 2019 Novel Coronavirusشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- An International Comparison of Factors Affecting Quality of Life Among Patients With Congestive Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument15 pagesAn International Comparison of Factors Affecting Quality of Life Among Patients With Congestive Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Studyشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Cardiac Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study From PalestineDocument13 pagesCardiac Self-Efficacy and Quality of Life in Patients With Coronary Heart Disease: A Cross-Sectional Study From Palestineشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Chaos, Solitons and Fractals: João A.M. Gondim, Larissa MachadoDocument7 pagesChaos, Solitons and Fractals: João A.M. Gondim, Larissa Machadoشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Yogi Tri Prasetyo, Allysa Mae Castillo, Louie John Salonga, John Allen Sia, Joshua Adam SenetaDocument12 pagesYogi Tri Prasetyo, Allysa Mae Castillo, Louie John Salonga, John Allen Sia, Joshua Adam SenetaArgonne Robert AblanqueNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Journal of A Ffective Disorders: Research PaperDocument6 pagesJournal of A Ffective Disorders: Research Paperشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Journal of Infection and Public Health: Qianqian Cui, Zengyun Hu, Yingke Li, Junmei Han, Zhidong Teng, Jing QianDocument7 pagesJournal of Infection and Public Health: Qianqian Cui, Zengyun Hu, Yingke Li, Junmei Han, Zhidong Teng, Jing Qianشبلي غرايبهNo ratings yet

- Res Ipsa Loquitor-Application in Medical Negligence: Journal of South India Medicolegal Association January 2014Document13 pagesRes Ipsa Loquitor-Application in Medical Negligence: Journal of South India Medicolegal Association January 2014Ian GreyNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Narcissists' Perceptions of Narcissistic Behavior: William Hart, Gregory K. Tortoriello, and Kyle RichardsonDocument8 pagesNarcissists' Perceptions of Narcissistic Behavior: William Hart, Gregory K. Tortoriello, and Kyle RichardsonNaufal Hilmy FarrasNo ratings yet

- Premium Resistance Bands: Exercise GuideDocument25 pagesPremium Resistance Bands: Exercise GuideSimão Pedro MartinsNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Clear Aligners, A Milestone in Invisible Orthodontics - A Literature ReviewDocument4 pagesClear Aligners, A Milestone in Invisible Orthodontics - A Literature ReviewInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Avery's Neonatology PDFDocument3,845 pagesAvery's Neonatology PDFviaviatan100% (3)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- NR527 Module 2 (Reflection 2)Document3 pagesNR527 Module 2 (Reflection 2)96rubadiri96No ratings yet

- 07 Crash Cart Medication - (App-Pha-007-V2)Document4 pages07 Crash Cart Medication - (App-Pha-007-V2)سلمىNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Foundations of Addictions Counseling 4th Edition David Capuzzi Mark D StaufferDocument8 pagesTest Bank For Foundations of Addictions Counseling 4th Edition David Capuzzi Mark D StaufferLucille Alexander100% (36)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Jurnal Kapita Selekta Kelompok 3 Kapita SelektaDocument7 pagesJurnal Kapita Selekta Kelompok 3 Kapita SelektaQonita MaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Cv-Update For DoctorDocument2 pagesCv-Update For DoctorRATANRAJ SINGHDEONo ratings yet

- Syllabus Small Bowel ObstructionDocument4 pagesSyllabus Small Bowel ObstructionHARVEY SELIM0% (1)

- Chapter 14 Pathogenesis of Infectious DiseasesDocument18 pagesChapter 14 Pathogenesis of Infectious DiseasesedemcantosumjiNo ratings yet

- Ten CentersDocument4 pagesTen CentersJohn Christopher ReguindinNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Kompilasi Konten Covid-19Document50 pagesKompilasi Konten Covid-19Wa UdNo ratings yet

- Labor Nursing Care PlansDocument58 pagesLabor Nursing Care PlansMuhamad AriNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Sports Recreational Satisfaction, and Involvement in Physical Activity Among Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia (UTHM) StudentsDocument8 pagesThe Relationship Between Sports Recreational Satisfaction, and Involvement in Physical Activity Among Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia (UTHM) StudentsIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- (PEDIA) 2.04 Pediatric Neurologic Exam - Dr. Rivera PDFDocument15 pages(PEDIA) 2.04 Pediatric Neurologic Exam - Dr. Rivera PDFJudith Dianne IgnacioNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Analyctical 3Document22 pagesAnalyctical 3Bunda LembayungNo ratings yet

- Work Place Law Scenario AnalysisDocument3 pagesWork Place Law Scenario AnalysisMaria SyedNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Eyes and EarsDocument1 pageAssessment of Eyes and EarsBabyJane GRomeroNo ratings yet

- Ehc - 242 Dermal Exposure OMS PDFDocument528 pagesEhc - 242 Dermal Exposure OMS PDFAndrea DuarteNo ratings yet

- Lingua - Anatomi Dan Kelainan LidahDocument51 pagesLingua - Anatomi Dan Kelainan LidahKemalLuthfanHindamiNo ratings yet

- Sirona C4+ Dental Unit - User ManualDocument110 pagesSirona C4+ Dental Unit - User ManualOsamah AlshehriNo ratings yet

- 10 Symptoms of PneumoniaDocument3 pages10 Symptoms of PneumoniaYidnekachew Girma AssefaNo ratings yet

- Amoebiasis CBCDocument2 pagesAmoebiasis CBCImongheartNo ratings yet

- A Short Article About Stress (Eng-Rus)Document2 pagesA Short Article About Stress (Eng-Rus)Егор ШульгинNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana Stroke VertebrobasilarDocument20 pagesTatalaksana Stroke VertebrobasilarMarest AskynaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Rekapitulasi Desember 2021 SipDocument555 pagesRekapitulasi Desember 2021 SipadminIHC cakramedikaNo ratings yet

- Dealing With EmotionsDocument26 pagesDealing With EmotionsAli Ijaz100% (1)

- Textbook of Pediatric Dentistry-3rd EditionDocument18 pagesTextbook of Pediatric Dentistry-3rd EditionAnna NgNo ratings yet