Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ornament and Structure in Beethoven Charles Rosen

Uploaded by

Sebastian Hayn0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views4 pagesUi

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentUi

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views4 pagesOrnament and Structure in Beethoven Charles Rosen

Uploaded by

Sebastian HaynUi

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Ornament and Structure in Beethoven

Author(s): Charles Rosen

Source: The Musical Times , Dec., 1970, Vol. 111, No. 1534, Beethoven Bicentenary Issue

(Dec., 1970), pp. 1198-1199+1201

Published by: Musical Times Publications Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/955820

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Musical Times Publications Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Musical Times

This content downloaded from

178.191.134.120 on Thu, 13 Oct 2022 14:19:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ah, vous dirai-je, maman (a theme on which Tomagek Although in both cases these might be presumed to

heard Beethoven improvise in 1798). Here the be drafts with an intended destination, they never

element of conjecture is considerable, for the most seem to have reached it, and the suspicion grows

we really know is that these are sketches for move- that they served another function: that they were

ments apparently involving piano, bassoon and 'improvisations on paper', used by Beethoven to

'ho I.' (hohe Instrumente, or, as I read it, 'B. I.', keep his hand in even if he had nothing definite in

Blasende Instrumente). mind. The accurate transcription of such doodles

can scarcely be done by anyone who is less than

I have left myself little space to discuss other dedicated. I might add: less than courageous, for

sketches. But two particular types, singled out by Kerman must have required a good measure of

Kerman, call for comment. 'Kafka' contains a courage in order to press on with this great enterprise

profusion of short fragments consisting of no more when so often faced not only with the indecipherable

than a few bars of music in piano score, as well asbut a with the unintelligible, the inconsequential and

the trivial.

very large number of briefly notated dance melodies.

Ornament and Structure in Beethoven

Charles Rosen

identical. The basic ornament, from the 17th

In all the arts, the taste for ornamentation changed

century to our day, is the appoggiatura; to this may

radically during the last half of the 18th century.

The solid body of aesthetic doctrine which con- be added the trill, which was originally an extended

demned ornament as immoral dominated the appoggiatura. Yet the appoggiatura is perhaps the

period, and there were few pockets of resistance. fundamental expressive device for a good part of

To equate the practice of Mozart and Haydn the three

aftercenturies of music from 1600 to 1900. It

1780 with that of Bach, or even C.P.E. Bach, is even the traditional way of indicating sobs in

is to

ignore one of history's most sweeping revolutions opera. Ifin decoration is therefore both necessary,

taste. The musical ornamentation of the first half and even somehow central, to the musical composi-

of the 18th century is an essential element in the tion, how is one to distinguish it from structure?

achievement of continuity. Decoration not only Indeed, why bother? With a work like the slow

covers the underlying musical structure but keeps movement it of the Italian Concerto, would it not be

always flowing. The High Baroque in music hassimpler a to abandon the distinction and to declare

horror of the void, and the agrements fill what empty the decorative arabesque to be structure rather than

space has been left. In the opening bars of the ornament ?

Goldberg Variations, for example, the ornaments The opposition of structure and ornament, it

completely disguise the structure. The first two bars seems to me, must be maintained, but not if the

are melodically almost identical with the third and idea of ornament is considered either inessential or

fourth; with the ornamentation added, it is almost inexpressive. In music, the idea of structure and

impossible to realize this. The decoration of the ornament is a metaphor derived from architecture.

classical style, on the other hand, articulates struc- There, the distinction presents no problem: the

ture. The chief ornament retained from the baroque structural elements of the building are those which

is significantly the final cadential trill. Other make it stand up, that attack the force of gravity;

ornaments are used more rarely, and are almost the decorative elements are all the rest, and they are

always fully written out-necessarily so, as they as essential as the structural elements when the

have become thematic. This development in orna- purpose of the building is symbolic or expressive, as

mentation was carried by Beethoven as far as it it so often is. It is also clear that the structural

could go. In his later music, the trill has entirely lost elements can at times be themselves expressive or

its decorative status; it is no longer an ornament, symbolic. The force in music analogous to the

but either an essential motive, as in the Archduke force of gravity in architecture is the irreversible

Trio, or a suspension of rhythm, a way of turning a direction of time. The structural elements of music

long sustained note into an indistinct vibration are those which regulate the movement of a work in

which creates an intense and inward stillness. time and which make it coherent. In spite of the

It is often assumed that the decorative and the fact that no part of a work can take place in per-

expressive elements of a work are separable. This formance at the same time as another, that which

view is an inheritance from the neo-classical feeling gives the work an ideal existence as a simultaneous

that decoration is immoral, a view that has never whole may be called its structure. The rest is

died out and which we can still see today in decoration.

some architecture and in minimal art. The logic goes But if we must abandon the pejorative implica-

like this: art is essentially expressive; decoration istions of decoration, we ought not to forget that these

by definition that which is inessential; therefore theimplications held sway in the latter part of the 18th

expression and the decoration cannot be the same. century and that they are still valid for Beethoven.

In reality, the decorative and the expressive are oftenThere are, for example, arguments raging about

1198

This content downloaded from

178.191.134.120 on Thu, 13 Oct 2022 14:19:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

whether or not we should add ornaments to Mozart to the principles which Haydn and Mozart had

and, if so, where and how much; about Beethoven, worked with, developing and expanding them

there is no question that he wanted nothing addedbeyond anything that could have been predicted.

and made violent scenes when someone attemptedWhether

it. this withdrawal had anything to do with

We know what he thought of performers who added his increased suffering from his growing deafness can

anything to his music from his explosion when only be surmised. In any case, the removal of the

decorative Andante Favori from the Waldstein and

Czerny did so, and his subsequent letter of apology:

'you must pardon a composer who would have the substitution of the much more severe slow

preferred to hear his work exactly as he wrote it, no introduction to the finale that we now find there is

matter how beautifully you played in general'. an important step that marks the change in attitude.

Czerny had only done what we are told every The movement of a baroque piece is regulated by

pianist of the time did, added a few trills and used a harmonic sequence, and while the sequence re-

few octave doublings. mained indispensable later, it lost its central place in

What happened in the last quarter of the 18th the music of the later 18th century, to regain it only

century is that composers began to make structure with Schumann and Chopin. What replaced it were

take over the expressive function of ornament. The two musical devices-thematic development (or

tension of a work, its dramatic interest, came less diminution technique) and modulation. Both had

and less from its decorative element and more from existed before, but neither had been so used to

its shape and from its proportions and their weight. regulate the proportions as well as the flow of a

This is the reason for the down-grading of decora- work of music. The movement on a small scale was

tion, even when it retains part of its expressivedetermined in Haydn and Mozart by thematic

importance. In this tradition, Beethoven stands development and to a lesser extent by thematic

ambiguously at first, and with good reason. Around contrast. On the large scale, the sense of time and

1800, there was a fashionable revival of decoration the significant tempo, weight and mass of a work

inspired by Italian opera-it is clear in the works was of directed by modulation, no longer a gradual

Hummel, and it was eventually to lead to Chopin, drift in or a chromatic colouring as it has been earlier

whose music the expression is once again carriedin the century, but an articulated and dramatic

chiefly by the ornamental detail as it was in so much series of actions. Haydn and Mozart had used

of Bach, whom Chopin idolized. ornaments to emphasize this change in procedure-

Beethoven, as we are acutely aware this year, was to outline it and set it in relief. But Beethoven's use

born in 1770 in a town somewhat outside the main- was even more radical. As in Haydn and Mozart,

stream of musical development. We are accustomed his ornaments became thematic. The turn in the

to think of him as part of the generation that minuet of the E flat Sonata op 31 no 3 (ex 1) is still

followed Mozart, but we forget the geographical Ex 1

displacement which closes part of the gap. He was,

it is true, almost a generation younger than Mozart,

but the small musical world of Bonn was not as

quickly aware of international changes in style as

an expressive decoration, but the same turn in the

main theme of the Emperor Concerto (ex 2) has

was Mozart, who had been a traveller to the principal

musical centres from a very early age. At least

Bonn did not react as fast as Vienna did. The Ex 2

sonatas that Beethoven wrote when he was 13 in

1783 are very like the works that Haydn had com-

posed 10 to 15 years before, and they show no now become purely thematic and non-decorative.

knowledge of more recent developments-while One may even say that it has lost its expressive

Mozart in 1773 was already imitating Haydn's quality to become more neutral. Above all, the

op 20 quartets which had appeared only one year turn is a source of motion, charged with energy as

before. In other words, when we think in terms of at the opening of the cadenza that Beethoven wrote

stylistic development, we must close the gap between as an integral part of the first movement.

Beethoven and Mozart by ten years. Beethoven was Beethoven's trills are as thematic as his turns.

in fact closer to Mozart than Mozart was to Haydn. The opening of the Violin Sonata in G, op 96 (ex 3)

Nevertheless, as a young man of 21 arriving in Ex 3

Vienna (after one short previous visit when he had

been 16), he was at first swept off his feet by some of

the new modes of musical thought. There are

experiments in lavish operatic ornamentation that treats the trill as neither ornamental nor particularly

far exceed anything that Mozart had ever attempted, expressive. It is almost truly thematic here, expres-

even in the ornamental concert arias. The luxuriance

sive only in its establishment of the lyrical and

of the slow movement of the Sonata in G, op 31delicate character of the work, but it is not an

no 1, is a good example of Beethoven's interest affective

in nuance or an enlargement of the basic

this operatic ornamentation; the slow movement motive.

of The two fugues in Beethoven's late piano

the Piano Concerto in C minor is even more sonatas-the finale of the Hammerklavier and the

fantastically decorated, and far more dramatic in its

development section of the finale of op 101-both

intention.

use the trill in the way that deprives it of all orna-

With the Waldstein Sonata, Beethoven began to mental significance. The trill in op 101 comically

turn his back on this fashionable style and returned loses all decorative quality by having its end

1199

This content downloaded from

178.191.134.120 on Thu, 13 Oct 2022 14:19:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The slow movement of the last sonata, op 111,

combines at its climax a series of trills with the

only modulation in the movement. Once again it

is the return of the theme that is being prepared.

chopped off (ex 4), and nothing better enforces its And once again the illusion of motion is achieved,

non-ornamental function than this surgery. A trill an illusion that creates a spectacular dramatic

of this kind is generally meant to ornament a tension while never weakening the stability that

cadence: to cut off the last note of the cadential lies at the centre of the form. What Beethoven does

phrase is entirely to change the sense of it. The trill

is to expand the cadential trill before the return. The

in the theme of the Hammerklavier finale is even immense passage that opens with the trill and

more firmly motivated in that it is derived from the its expansion and finishes with the return of the

opening of the first movement (ex 5). If we remember theme is a withholding of the resolution of the

Ex 5

trill by a sequence-a circular sequence that appears

(finale) (first movernetit

to progress but in fact only revolves. This passage

occurs towards the end of the movement, after

almost a quarter of an hour of the purest C major.

that a trill is an extended appoggiatura, the we

And when deriva-

reach the trill we must remember the

tion is a simple one.

temporal weight and mass of the preceding C

Later in the movement the trill is even separated

major in order to understand what follows.

from everything else in the theme except the opening

The trill

leap, and used for an extensive thematic is the culminating point in the rhythmic

develop-

scheme of the movement. The variation-set which

ment at the end of the augmentation of the theme.

proceeds by

But in this powerful and terrifying passage gradual

the use acceleration-in which each

successive variation is faster than the last-is

of the trill goes beyond the thematic and starts to

common

have a fundamental effect on the larger enough

sense ofsince the 16th century, but in no

work as

movement, on the way in which the piece before op 111 are the gradations so carefully

a whole

worked

fills time. It represents the creation out. The sequence may be represented by

of a tension

the basic rhythm of each unit as shown in ex 6.

unresolved until the cessation of the trill. In this

role it is analogous to the use of modulation in a

classical work, and Beethoven indeed uses it to Ex 6

Theme 1 I1 Id"iV

create the tension that a modulation to a foreign

key can induce at moments when such harmonic

movement is not possible. This is the reason that

the long trills in some of Beethoven's later works The fourth variation reaches almost undifferentiated

create a sense both of stillness and of excitement. pulsation, enforced by the continuous pianissimo

The most striking examples of long trills in and by the omission of the melody note from the

Beethoven are found within variation form. As its opening of every beat. The trill represents the com-

name indicates this is basically an ornamental form, plete dissolution of even this rhythmic articulation:

like the fugue an inheritance from an earlier period. the movement reaches the extremes of rapidity and

The transformation of the variation was one of of immobility. Its importance in the rhythmic

Beethoven's most considerable achievements. It is structure of the movement as a whole accounts for

easy to see in what way the trill was useful to Beet- the length of the trill and for its sonorous transfor-

hoven for his variation sets. A long trill creates anmation into a triple trill. The trill returns on the

insistent tension while remaining completely static;last page, and the rhythm here is a synthesis of all

it helped Beethoven both to accept the static formthat went before: the rhythmic accompaniment of

of the variation set and to transcend it. For most of Variation IV (the fastest measured motion) and the

the time the trill retains its essential function as a theme in its original form (the slowest) are both

cadence. That is, even when it is combined with suspended under the unmeasured stillness of the

other simultaneous musical activity, it nullifies the trill. It is in this way that the most typical ornamen-

dynamic effect of these other motions. For example, tal device is turned into an essential element of

at the end of Mozart's own cadenza to his F major large-scale structure.

concerto, K459, the theme is played under a length-

ened final trill, and the trill in the right hand tells us

that the changes of harmony below cannot lead

anywhere. In the same way the trill of the

last variation of Beethoven's Sonata in E, op 109, on

a much larger scale, implies that the work is aboutThayer's Life of Beethoven, edited by Elliot Forbes, has been

to come to an end. The acceleration of the trill is reissued as a paperback (Princeton/Oxford, 60s): for Alan

Tyson's review, see 'Thayer-Deiters-Riemann-Krehbiel-Forbes',

carefully calculated from the slowest possible

MT March 1965, p.192, and for corrections see MT July 1965,

opening on single beats; and its immense growth isp.525.

accentuated by transferring it into different registers.

The Musical Times 1844-1969 is available on microfilm front

This trill charges a static moment with the fullWorld Microfilms, 62 Queen's

for complete set, ?510.

Grove, London NW8. Price

dynamic force; a dynamism that could be achieved

otherwise only by the kind of successive modulationsMusicology is the title of a first microfilm catalogue devoted to

musical books and periodicals available from Inter Documenta-

that Beethoven attempted in the F major variationstion Co AG, Poststrasse 4, Zug, Switzerland.

op 34. After the trill, the simple lyricism of theBlackwell's new music shop was opened by Sir Adrian Boult on

theme returns, as if after an enormous modulation.Nov 9; it is at 38 Holywell, Oxford.

1201

This content downloaded from

178.191.134.120 on Thu, 13 Oct 2022 14:19:36 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Blues Guitar MasteryDocument48 pagesBlues Guitar Masterybubblejo100% (8)

- Major and Minor Scales by J.K. MertzDocument21 pagesMajor and Minor Scales by J.K. Mertzwilburroberts20034852100% (10)

- Alfred Brendel A Pianists A Z - A Piano Lovers Reader PDFDocument91 pagesAlfred Brendel A Pianists A Z - A Piano Lovers Reader PDFSofia100% (1)

- The Art of Accompaniment from a Thorough-Bass: As Practiced in the XVII and XVIII Centuries, Volume IFrom EverandThe Art of Accompaniment from a Thorough-Bass: As Practiced in the XVII and XVIII Centuries, Volume IRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- How To Read MusicDocument29 pagesHow To Read MusicSafiyyah NajwaNo ratings yet

- Brad Mehldau - Analisi Blues Charlie ParkerDocument8 pagesBrad Mehldau - Analisi Blues Charlie ParkerClaudio Maioli100% (2)

- Violin Music of BeethovenDocument119 pagesViolin Music of Beethovenchircu100% (5)

- Broken City Percussion 2019 Front Ensemble PacketDocument7 pagesBroken City Percussion 2019 Front Ensemble PacketJillian Seitz100% (2)

- Trinity Theory Grade 1 (Part 2)Document25 pagesTrinity Theory Grade 1 (Part 2)robin pereiraNo ratings yet

- The Violin Music of Beethoven (1902)Document127 pagesThe Violin Music of Beethoven (1902)kyfkyf2100% (3)

- Review of 18th-Century Singing TreatisesDocument4 pagesReview of 18th-Century Singing TreatisesSandra Myers BrownNo ratings yet

- Anger - Form in Music - With Special Reference To The Bach Fugue and The Beethoven Sonata (1900)Document140 pagesAnger - Form in Music - With Special Reference To The Bach Fugue and The Beethoven Sonata (1900)Gregory Moore100% (1)

- Bartok - The Influence of Peasant MusicDocument7 pagesBartok - The Influence of Peasant MusicTom MacMillan100% (1)

- Chamber Music: Selections from Essays in Musical AnalysisFrom EverandChamber Music: Selections from Essays in Musical AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ross, David J. - Ornamentation in The Bassoon Music of Vivaldi and Mozart 1Document7 pagesRoss, David J. - Ornamentation in The Bassoon Music of Vivaldi and Mozart 1massiminoNo ratings yet

- Kiki's Delivery Service-PianoDocument6 pagesKiki's Delivery Service-PianofammicanNo ratings yet

- Harmonic Functionalism in Russian Music Theory: A PrimerDocument24 pagesHarmonic Functionalism in Russian Music Theory: A Primerscribd100% (1)

- Renaissance & Baroque OverviewDocument8 pagesRenaissance & Baroque OverviewWaltWritmanNo ratings yet

- Form in MusicDocument124 pagesForm in Musicpodleader100% (3)

- Martha Bixler - Renaissance OrnamentationDocument13 pagesMartha Bixler - Renaissance OrnamentationXavier VerhelstNo ratings yet

- Musica Secundum Imaginationem - Notation, Complexity, and Possibility in The Ars SubtiliorDocument14 pagesMusica Secundum Imaginationem - Notation, Complexity, and Possibility in The Ars SubtiliorThomas PattesonNo ratings yet

- Bach - 6a.embellishments IDocument5 pagesBach - 6a.embellishments IPailo76No ratings yet

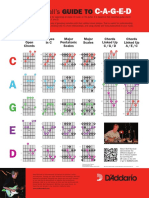

- Caged System PDFDocument1 pageCaged System PDFGuitar ProNo ratings yet

- ItalianMadrigalVerse EinsteinDocument18 pagesItalianMadrigalVerse EinsteinAlessandra Rossi100% (1)

- The Tartini Style Sigurd ImsenDocument95 pagesThe Tartini Style Sigurd ImsenTomas CabreraNo ratings yet

- GB-LBL Add. Ms. 30387 Unveiled, by MCardinDocument97 pagesGB-LBL Add. Ms. 30387 Unveiled, by MCardinIvan JellinekNo ratings yet

- MbiraDocument25 pagesMbiraAhmet ErenNo ratings yet

- Webern and Atonality - The Path From The Old AestheticDocument7 pagesWebern and Atonality - The Path From The Old Aestheticmetronomme100% (1)

- Early Baroque OperaDocument19 pagesEarly Baroque OperaRasmiNo ratings yet

- Bach's Italian Concerto analyzed through its transcription originsDocument22 pagesBach's Italian Concerto analyzed through its transcription originsspinalzoNo ratings yet

- Dannreuther - Musical OrnamentationDocument246 pagesDannreuther - Musical OrnamentationMaria Petrescu100% (5)

- Analysis and Performing Mozart Joel LesterDocument16 pagesAnalysis and Performing Mozart Joel LesterSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Performing Mozart Joel LesterDocument16 pagesAnalysis and Performing Mozart Joel LesterSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Heinrich Schütz Edition: Sacred Choral WorksDocument124 pagesHeinrich Schütz Edition: Sacred Choral WorksJosé TelecheaNo ratings yet

- The Toccatas: Mahan EsfahaniDocument20 pagesThe Toccatas: Mahan EsfahaniPaul DeleuzeNo ratings yet

- Baroque StyleDocument15 pagesBaroque StyleColeen BendanilloNo ratings yet

- Weiss COMPLETE Liner Notes Download PDFDocument53 pagesWeiss COMPLETE Liner Notes Download PDFEmad Vashahi100% (1)

- Styles of Articulation in Italian Woodwind Sonatas of The Early Eighteenth Century: Evidence From Contemporary Prints and Manuscripts, With Particular Reference To The Sibley Sammartini ManuscriptDocument18 pagesStyles of Articulation in Italian Woodwind Sonatas of The Early Eighteenth Century: Evidence From Contemporary Prints and Manuscripts, With Particular Reference To The Sibley Sammartini ManuscriptTom MooreNo ratings yet

- Theory and practice of basso continuo in baroque musicDocument7 pagesTheory and practice of basso continuo in baroque musicNuno Oliveira100% (1)

- The Tonal-Metric Hierarchy - A Corpus Analysis Jon B. Prince, Mark A. SchmucklerDocument18 pagesThe Tonal-Metric Hierarchy - A Corpus Analysis Jon B. Prince, Mark A. SchmucklerSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- Dolmetsch - The Interpretation ofDocument518 pagesDolmetsch - The Interpretation ofMaria Petrescu100% (3)

- Ligeti QuintetDocument26 pagesLigeti QuintetSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- INGARDEN, Roman, Jean G. Harrell (Eds.) - The Work of Music and The Problem of Its IdentityDocument195 pagesINGARDEN, Roman, Jean G. Harrell (Eds.) - The Work of Music and The Problem of Its IdentityGlaucio Adriano Zangheri100% (1)

- Analysis Conclusions PDFDocument10 pagesAnalysis Conclusions PDFEmad VashahiNo ratings yet

- 19th Century Musical Performance PracticesDocument29 pages19th Century Musical Performance Practicesdarina slavovaNo ratings yet

- Genre and content in midcentury Verdi Addio delDocument29 pagesGenre and content in midcentury Verdi Addio delYasmini VargazNo ratings yet

- 11. Performance of Older MusicDocument4 pages11. Performance of Older MusiccadshoNo ratings yet

- Facing The Music Author(s) : Philip Brett Source: Early Music, Jul., 1982, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Jul., 1982), Pp. 347-350 Published By: Oxford University PressDocument5 pagesFacing The Music Author(s) : Philip Brett Source: Early Music, Jul., 1982, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Jul., 1982), Pp. 347-350 Published By: Oxford University PressPatrizia MandolinoNo ratings yet

- Grace (1921) - Bach and TranscriptionDocument5 pagesGrace (1921) - Bach and TranscriptionDimitris ChrisanthakopoulosNo ratings yet

- Sequenza I For Solo Flute by Berio Riccorenze For Wind Quintet by Berio Rendering by BerioDocument3 pagesSequenza I For Solo Flute by Berio Riccorenze For Wind Quintet by Berio Rendering by BerioZacharias TarpagkosNo ratings yet

- Butt-ImprovisedVocalOrnamentation-1991Document23 pagesButt-ImprovisedVocalOrnamentation-1991cevezamusNo ratings yet

- Musical Times Publications Ltd. The Musical TimesDocument3 pagesMusical Times Publications Ltd. The Musical TimesVassilis BoutopoulosNo ratings yet

- Download The Science Of Sleep The Path To Healthy Sleep The Scientific Guide To Ideal Sleep Balancing Body And Mind Through Sleep Neuroessentials Pathways To Mental Clarity And Well Being Book 2 full chapterDocument68 pagesDownload The Science Of Sleep The Path To Healthy Sleep The Scientific Guide To Ideal Sleep Balancing Body And Mind Through Sleep Neuroessentials Pathways To Mental Clarity And Well Being Book 2 full chaptermatthew.ferguson216100% (3)

- Ornamental-Potential-Of-The-Pan-Flute-Illustrated-In-Baroque-Transcriptions - Content File PDFDocument11 pagesOrnamental-Potential-Of-The-Pan-Flute-Illustrated-In-Baroque-Transcriptions - Content File PDFAndrei DrutaNo ratings yet

- Who Were The Major Baroque Composers and Where Were They From?Document5 pagesWho Were The Major Baroque Composers and Where Were They From?Athina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of 20th Century HarmonyDocument6 pagesThe Evolution of 20th Century Harmonypascumal0% (1)

- deocument_153Document22 pagesdeocument_153dorothy.delgado482No ratings yet

- Caldara 1Document8 pagesCaldara 1chiaradezuaniNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 82.49.19.160 On Fri, 11 Dec 2020 14:09:58 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 82.49.19.160 On Fri, 11 Dec 2020 14:09:58 UTCPatrizia MandolinoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument21 pagesUntitledLuis SavaNo ratings yet

- Johann Sebastian Bach - Cello Suites BWV 1007-1012Document4 pagesJohann Sebastian Bach - Cello Suites BWV 1007-1012Heidi Lara0% (1)

- Musical Times Publications LTD.: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPDocument5 pagesMusical Times Publications LTD.: Info/about/policies/terms - JSPGuilherme Estevam AraujoNo ratings yet

- Distance PDocument24 pagesDistance PLilly VarakliotiNo ratings yet

- Heinrich Schütz EditionDocument124 pagesHeinrich Schütz EditionJoão SassacamiNo ratings yet

- Portrait Gallery of The Great Composers Author(s) : Gustav Kobbé Source: The Lotus Magazine, May, 1911, Vol. 2, No. 5 (May, 1911), Pp. 140-160 Published byDocument22 pagesPortrait Gallery of The Great Composers Author(s) : Gustav Kobbé Source: The Lotus Magazine, May, 1911, Vol. 2, No. 5 (May, 1911), Pp. 140-160 Published byStrawaNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Background of MozartDocument20 pagesAnalysis and Background of MozartAnonymous BBs1xxk96VNo ratings yet

- 13 Cambridge Recorder Facsimiles and Editing0001Document14 pages13 Cambridge Recorder Facsimiles and Editing0001Gabi SilvaNo ratings yet

- Blum Minor ComposersDocument12 pagesBlum Minor ComposersKatherine QcNo ratings yet

- Originally Published in The Book That Came With The Vinyl Boxed Edition of Soft Verdict's Maximizing The Audience TWI 485Document7 pagesOriginally Published in The Book That Came With The Vinyl Boxed Edition of Soft Verdict's Maximizing The Audience TWI 485EduardoNo ratings yet

- Mozart Keyboard Sonatas Contain Topical ElementsDocument6 pagesMozart Keyboard Sonatas Contain Topical ElementsRobison PoreliNo ratings yet

- Style_brise_Style_luthe_and_the_Choses_lDocument17 pagesStyle_brise_Style_luthe_and_the_Choses_lfrannerja2No ratings yet

- Form and Function of The Classical Cadenza Joseph P. SwainDocument34 pagesForm and Function of The Classical Cadenza Joseph P. SwainSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Form and Function of The Classical Cadenza Joseph P. SwainDocument34 pagesForm and Function of The Classical Cadenza Joseph P. SwainSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Major-Minor Concepts and Modal Theory in Germany, 1592-1680 Joel LesterDocument47 pagesMajor-Minor Concepts and Modal Theory in Germany, 1592-1680 Joel LesterSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- Effect of Voice-Part Training and Music Complexity On Focus of Attention To Melody or Harmony Lindsey R. WilliamsDocument14 pagesEffect of Voice-Part Training and Music Complexity On Focus of Attention To Melody or Harmony Lindsey R. WilliamsSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Debussy, Pentatonicism, and The Tonal Tradition Jeremy Day-O'ConnellDocument38 pagesDebussy, Pentatonicism, and The Tonal Tradition Jeremy Day-O'ConnellSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Classical Harmony - Rules of Inference and The Meaning of The Logical Constants Peter MilneDocument47 pagesClassical Harmony - Rules of Inference and The Meaning of The Logical Constants Peter MilneSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- A Recurring Pattern in Mozart's "Music" David Beach, MozartDocument30 pagesA Recurring Pattern in Mozart's "Music" David Beach, MozartSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Debussy, Pentatonicism, and The Tonal Tradition Jeremy Day-O'ConnellDocument38 pagesDebussy, Pentatonicism, and The Tonal Tradition Jeremy Day-O'ConnellSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- A Recurring Pattern in Mozart's "Music" David Beach, MozartDocument30 pagesA Recurring Pattern in Mozart's "Music" David Beach, MozartSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Tonal and Motivic Process in Mozart's Expositions Scott L. BalthazarDocument47 pagesTonal and Motivic Process in Mozart's Expositions Scott L. BalthazarSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- Major-Minor Concepts and Modal Theory in Germany, 1592-1680 Joel LesterDocument47 pagesMajor-Minor Concepts and Modal Theory in Germany, 1592-1680 Joel LesterSebastian Hayn100% (1)

- Effect of Voice-Part Training and Music Complexity On Focus of Attention To Melody or Harmony Lindsey R. WilliamsDocument14 pagesEffect of Voice-Part Training and Music Complexity On Focus of Attention To Melody or Harmony Lindsey R. WilliamsSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Modern QuintetsDocument2 pagesModern QuintetsSebastian HaynNo ratings yet

- Dall'Abaco, Evaristo FeliceDocument4 pagesDall'Abaco, Evaristo FeliceJorge Andrés Garzón RuizNo ratings yet

- Performance Problems in Akira Miyoshi ConversationDocument20 pagesPerformance Problems in Akira Miyoshi ConversationCristiano PirolaNo ratings yet

- Tonnetz PDFDocument4 pagesTonnetz PDFMatia Campora0% (2)

- Chord Relationships and EmotionDocument4 pagesChord Relationships and EmotionraissaNo ratings yet

- Filipino folk music elementsDocument26 pagesFilipino folk music elementsBawit, Bryan V.No ratings yet

- Giuseppe TartiniDocument16 pagesGiuseppe Tartiniapi-240173867No ratings yet

- Erik Satie Vexations PDFDocument2 pagesErik Satie Vexations PDFRaulNo ratings yet

- CA Prekindergarten Music StandardsDocument31 pagesCA Prekindergarten Music StandardscmcintronNo ratings yet

- Drive My CarDocument2 pagesDrive My CarYunhan ShengNo ratings yet

- In Resurrectione Tua: Superius (Soprano)Document4 pagesIn Resurrectione Tua: Superius (Soprano)Jacob Perry Jr.No ratings yet

- World's Smallest Violin - AJRDocument1 pageWorld's Smallest Violin - AJRLaof76No ratings yet

- Pop Music PDFDocument6 pagesPop Music PDFEnea LleshiNo ratings yet

- Dynamics and elements of musicDocument8 pagesDynamics and elements of musicmark ebaoNo ratings yet

- Comperisson So WhatDocument3 pagesComperisson So WhatMarvin FreyNo ratings yet

- Goo Goo Dolls "IrisDocument1 pageGoo Goo Dolls "IrisRaffi HolzerNo ratings yet

- Full Orchestra PartituraDocument2 pagesFull Orchestra PartituraAlexandruUdreaNo ratings yet

- How to map CAGED chord and pentatonic scale shapes up the neckDocument7 pagesHow to map CAGED chord and pentatonic scale shapes up the neckSheila RamosNo ratings yet

- Jazz Guitar: The History, The Players Jazz Guitar: The History, The PlayersDocument40 pagesJazz Guitar: The History, The Players Jazz Guitar: The History, The PlayersKleber Alexander TavaresNo ratings yet

- Allegro Maestoso (From Water Music) : (An Arrangement For The Wedding of Rolando & Vera - 2019)Document3 pagesAllegro Maestoso (From Water Music) : (An Arrangement For The Wedding of Rolando & Vera - 2019)Joana De Paula MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Music (Diagnostic Test)Document2 pagesMusic (Diagnostic Test)Sarah mae EmbalsadoNo ratings yet