Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Papachristou2009 1

Uploaded by

Leopoldo MagañaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Papachristou2009 1

Uploaded by

Leopoldo MagañaCopyright:

Available Formats

nature publishing group ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTIONS 435

see related editorial on page 443

CME

PANCREAS

Comparison of BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE-II, and CTSI

Scores in Predicting Organ Failure, Complications, and

Mortality in Acute Pancreatitis

Georgios I. Papachristou, MD1,2, Venkata Muddana, MD1, Dhiraj Yadav, MD1, Michael O’Connell, PhD1, Michael K. Sanders, MD1,

Adam Slivka, MD, PhD1 and David C. Whitcomb, MD, PhD1,3,4

OBJECTIVES: Identification of patients at risk for severe disease early in the course of acute pancreatitis (AP)

is an important step to guiding management and improving outcomes. A new prognostic scoring

system, the bedside index for severity in AP (BISAP), has been proposed as an accurate method

for early identification of patients at risk for in-hospital mortality. The aim of this study was to

compare BISAP (blood urea nitrogen >25 mg/dl, impaired mental status, systemic inflammatory

response syndrome (SIRS), age > 60 years, and pleural effusions) with the “traditional”

multifactorial scoring systems: Ranson’s, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination

(APACHE)-II, and computed tomography severity index (CTSI) in predicting severity, pancreatic

necrosis (PNec), and mortality in a prospective cohort of patients with AP.

METHODS: Extensive demographic, radiographic, and laboratory data from consecutive patients with AP

admitted or transferred to our institution was collected between June 2003 and September

2007. The BISAP and APACHE-II scores were calculated using data from the first 24 h from

admission. Predictive accuracy of the scoring systems was measured by the area under the

receiver-operating curve (AUC).

RESULTS: There were 185 patients with AP (mean age 51.7, 51% males), of which 73% underwent contrast-

enhanced CT scan. Forty patients developed organ failure and were classified as severe AP (SAP;

22%). Thirty-six developed PNec (19%), and 7 died (mortality 3.8%). The number of patients with a

BISAP score of ≥3 was 26; Ranson’s ≥3 was 47, APACHE-II ≥8 was 66, and CTSI ≥3 was 59. Of the

seven patients that died, one had a BISAP score of 1, two had a score of 2, and four had a score of

3. AUCs for BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE-II, and CTSI in predicting SAP are 0.81 (confidence interval

(CI) 0.74–0.87), 0.94 (CI 0.89–0.97), 0.78 (CI 0.71–0.84), and 0.84 (CI 0.76–0.89), respectively.

CONCLUSIONS: We confirmed that the BISAP score is an accurate means for risk stratification in patients with

AP. Its components are clinically relevant and easy to obtain. The prognostic accuracy of BISAP is

similar to those of the other scoring systems. We conclude that simple scoring systems may have

reached their maximal utility and novel models are needed to further improve predictive accuracy.

Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:435–441; doi:10.1038/ajg.2009.622; published online 27 October 2009

INTRODUCTION hospital admissions per annum in the United States (1–4). It is a

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is a common disorder with substan- complex process in which pancreatic enzyme activation causes

tial burden on the health-care system. AP accounts for 210,000 local pancreatic damage, resulting in an acute inflammatory

1

Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA;

2

Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Medicine, Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Health System, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; 3Department of Cell Biology

& Physiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA; 4Department of Human Genetics, University of Pittsburgh School

of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA. Correspondence: Georgios I. Papachristou, MD, Department of Medicine, UPMC Presbyterian, M2 C Wing, 200

Lothrop Street, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15213, USA. E-mail: papachri@pitt.edu

Received 21 February 2009; accepted 24 June 2009

© 2010 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

436 Papachristou et al.

response. The clinical course of AP is usually mild and often The BISAP score was retrospectively derived and validated

resolves without sequelae. Nonetheless, between 10 and 20% based on a large population data set (Cardinal Health Clini-

of patients experience a severe AP (SAP) attack, resulting in cal Outcomes Research Database, Cardinal Health, Marl-

PANCREAS

an intense inflammatory response, a variety of local and sys- borough, MA, USA) (14). A prospective validation of BISAP

temic complications, a prolonged hospital course, significant as a prognostic scoring system in AP was recently published

morbidity and mortality (5–8). In such patients, the acute (15), concluding that it is indeed a reliable and accurate means

inflammatory response may progress to systemic inflamma- of stratifying patients with AP for clinical care and research.

tory response syndrome (SIRS), multiorgan failure, and/or The aim of this study is (1) to evaluate the BISAP score in an

pancreatic necrosis (PNec). However, the individual patient independent prospectively enrolled cohort of patients from

response to pancreatic injury is highly variable and often a different geographic area, and (2) to compare its accuracy

unpredictable. Clinical biomarkers that predict the develop- to the “traditional” multifactorial scoring systems: Ranson’s,

ment of these life-threatening complications are important APACHE-II, and CTSI in predicting disease severity, PNec,

to help guide patient triage and management. However, no and mortality.

simple test or group of tests have proven to perform signifi-

cantly better in clinical settings than good clinical judgment

(1), and the available scoring systems are used primarily for METHODS

comparing clinical research studies. The Severity of Acute Pancreatitis Study protocol was approved

The Ranson’s (9) score represented a major advance in evalu- by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pitts-

ating the severity of AP and has been used for over three dec- burgh. Enrollment was conducted at two tertiary care hospitals

ades to assess AP severity. The Ranson’s score is moderately of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Informed con-

accurate in classifying patients in terms of severity, but has the sent was obtained from all patients or appropriate surrogates

disadvantage of requiring a full 48 h to be completed, missing a before study enrollment. The diagnosis of AP was based on the

potentially valuable early therapeutic window (10). In addition, presence of two of the following three features: (i) abdominal

it contains data not routinely ordered or collected during hos- pain characteristic of AP, (ii) serum amylase and/or lipase ≥3

pitalization at the current time (eg, lactate dehydrogenase, fluid times the upper limit of normal, and (iii) characteristic find-

sequestration, and base deficit). In the United States, the most ings of AP on abdominal CT scan.

commonly used prediction scoring system for clinical research Extensive demographic, radiographic, and laboratory data

studies in AP is the Acute Physiology and Chronic Health from consecutive patients with AP admitted or transferred

Examination (APACHE)-II (11,12). The APACHE-II score is to our institution was collected. On rare occasions not all

as accurate as Ranson’s score and can be administered on any the laboratory values or vital signs were available in patients

day. However, as a tool that was originally designed to predict included in the study who were transferred to our institution

intensive care unit survival, APACHE-II requires the collection from outside hospitals. No points were added to the scoring

of a large number of parameters, some of which may not be systems for missing values. The BISAP and APACHE-II scores

relevant to AP prognosis, whereas other important measures, were calculated using data from the first 24 h from admission

such as pancreatic injury and significant regional complications and the Ranson’s score using data from the first 48 h. CTSI was

are missed. Balthazar et al. (13) developed a grading system calculated in patients who underwent CECT within 48 h from

based on contrast-enhanced CT scan (CECT) findings. This admission.

prognostic score uses CT scan features of AP and PNec, allow- Patients were classified as mild AP or severe AP, based on

ing the calculation of a CT severity index (CTSI). The CTSI, the presence of organ failure for more than 48 h. Organ failure

however, is based on local complications and has the drawback included shock (systolic blood pressure < 90 mm Hg), pulmo-

of not reflecting the systemic inflammatory response. Other nary insufficiency (arterial PO2 < 60 mm Hg at room air or the

scoring systems have also been evaluated, but most of them are need for mechanical ventilation), or renal failure (serum cre-

modifications of the three systems outlined above. atinine level >2 mg/dl after rehydration or hemodialysis). PNec

Recently, a new prognostic scoring system, the bedside index was assessed by CECT. Evidence of PNec on CT was defined as

for severity in AP (BISAP), has been proposed as an accurate lack of enhancement of pancreatic parenchyma with contrast

method for early identification of patients at risk for in-hospital (18). All CT scans were reviewed by radiologists dedicated to

mortality. The BISAP uses five points: urea nitrogen (BUN) abdominal imaging, who were blinded to laboratory data and

>25 mg/dl, impaired mental status by evidence of disorienta- clinical course.

tion or disturbance in mental status, presence of the SIRS, age

>60 years, and pleural effusions (14,15). SIRS is defined by the Statistics

presence of ≥2 of the following criteria: pulse >90 beats/min, Descriptive data are presented as median and interquartile

respirations >20 per min, or PaCO2 < 32 mm Hg, temperature range for continuous variables. Categorical data are pres-

>100.4 °F or < 96.8 °F and white blood cell count >12,000 ented as proportions. Bivariate relationship for categorical

or < 4,000 cells per mm3 or >10% immature neutrophils variables was assessed using odds ratios (OR) calculated

(bands) (16,17). based on Pearson’s χ2-test. The distribution of severity, PNec,

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 105 | FEBRUARY 2010 www.amjgastro.com

Comparison of BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE, and CTSI Scores 437

and mortality by the BISAP point score was assessed using A significant trend for disease severity, PNec, and mortality

the Cochran–Armitage trend test. Sensitivity, specificity, was seen with increasing BISAP score.

positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive

PANCREAS

value (NPV) were calculated for individual scoring systems. Comparison of scoring systems in predicting SAP, PNec, and

Receiver-operating characteristic curves for SAP, PNec, and mortality

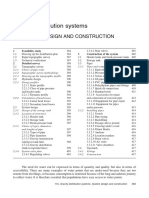

mortality were calculated for BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE- Receiver-operating characteristic curves yielded an AUC of

II, and CTSI scores using cutoff values, and the predictive 0.81 (95% confidence intervals (CI) 0.74–0.87) for BISAP

accuracy of each scoring system was measured by the area in predicting disease severity, 0.78 (CI 0.69–0.85) in pre-

under the receiver-operating curve (AUC). Pairwise AUC dicting the development of PNec and 0.82 (CI 0.67–0.91)

comparisons were also performed between two scoring sys- in predicting mortality. AUCs for each scoring system in

tems at a time using the nonparametric approach developed predicting SAP, PNec, and mortality are shown in Table 2.

by DeLong et al. (19). Ranson’s score showed a slightly higher accuracy for pre-

dicting SAP 0.94 (CI 0.89–0.97) and mortality 0.95 (CI

0.90–0.98). CTSI, as expected, was the most accurate in

RESULTS predicting PNec, as evidence of PNec is based on CT scan

Patient characteristics readings, with an AUC of 0.98 (CI 0.94–1.00). Pairwise

A total of 185 patients with AP were prospectively enrolled comparison revealed an AUC of 0.83 (CI 0.76–0.88) for

between June 2003 and September 2007. All patients were BISAP score and 0.93 (CI 0.88–0.97) for Ranson’s score in

recruited within 24 h from the time of admission or transfer predicting severe disease with a small overlap between the

(18). Of these, 83 (44.8%) patients were initially admitted at 95% CI (Figure 1a). Pairwise comparison of BISAP with

outside hospitals and subsequently transferred to our institu- APACHE-II score revealed similar accuracy in predicting

tion. Data within 24 h from the initial admission were collected SAP (AUC 0.83 (CI 0.76–0.88) and 0.78 (CI 0.68–0.85),

in all transferred patients and used for the calculation of the respectively; Figure 1b).

BISAP and APACHE-II scores. Only 3% of the laboratory val- On the basis of highest sensitivity and specificity values

ues or vital signs required were not available in these patients. generated from the receiver-operating characteristic curves,

The median age was 52 years (interquartile range 37–66; the following cutoffs were selected for further analysis:

range 15–90), with 51% men and 87% white. The etiolo- BISAP score ≥3, Ranson’s ≥3, APACHE-II ≥8, and CTSI ≥3.

gies of AP included biliary (36%), idiopathic (27%), alcohol The observed incidence of severe disease, PNec, and mortal-

(14%), post-endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatogra- ity stratified by the above BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE-II, and

phy (14%), hypertriglyceridemia (4%), and others (5%). One CTSI cutoffs with the corresponding OR are seen in Table 3.

hundred-thirty five (73%) patients underwent CECT early in The number of patients with a BISAP score of ≥3 was 26,

their hospitalization. Forty patients (22%) developed persist- Ranson’s ≥3 was 47, APACHE-II ≥8 was 66, and CTSI ≥3 was

ent organ failure for ≥48 h and were classified as SAP (multi- 59. On χ2-test, patients with a BISAP score ≥3 had a 7-fold

organ failure 48%). Thirty-six patients (19%) had evidence of higher likelihood of developing SAP (OR 7.3), five times for

PNec on CECT. The median length of stay was 7 days (inter- PNec (OR 4.8) and 10-fold higher likelihood of death (OR

quartile range 4–16; range 1–105). Seven patients died during 9.5). In regards to mortality, all seven patients who died had

hospitalization (mortality 3.8%). a Ranson’s score ≥3 and APACHE-II score ≥8. On the other

hand, one patient who died had a BISAP score of 1, two

BISAP score patients had a score of 2, four patients had a BISAP score of

The proportion of subjects with severe disease, PNec, and mor- 3, and no such patients had a score of 4 or 5. Using the above

tality stratified by the BISAP point score is presented in Table 1. cutoffs, the sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of different

Table 1. Number of patients and their proportion with SAP, PNec, and mortality stratified by the BISAP point score

BISAP score Number of patients SAP PNec Mortality

0 64 1 (1.6%) 3 (4.7%) 0 (0%)

1 59 10 (16.9%) 6 (10.2%) 1 (1.7%)

2 36 14 (38.9%) 15 (41.7%) 2 (5.6%)

3 18 11 (61.1%) 7 (38.9%) 4 (22.2%)

4 8 4 (50%) 5 (62.5%) 0 (0%)

5 0 NA NA NA

BISAP, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis; PNec, pancreatic necrosis; SAP, severe AP.

Cochran–Armitage trend test P values for disease severity, PNec, and mortality were < 0.001, < 0.001, and < 0.01, respectively.

© 2010 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

438 Papachristou et al.

Table 2. AUC of different scoring systems in predicting SAP, PNec, and mortality

AUC (95% CI) Severity PNec Mortality

PANCREAS

BISAP 0.81 (0.74 – 0.87) 0.78 (0.69 – 0.85) 0.82 (0.67 – 0.91)

Ranson’s 0.94 (0.89 – 0.97) 0.85 (0.79 – 0.90) 0.95 (0.90 – 0.98)

APACHE-II 0.78 (0.71 – 0.84) 0.72 (0.64 – 0.78) 0.94 (0.89 – 0.97)

CTSI 0.84 (0.76 – 0.89) 0.98 (0.94 – 1.00) 0.83 (0.75 – 0.89)

APACHE-II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination-II; AUC, area under the receiver-operating curve; BISAP, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis;

CTSI, computed tomography severity index; PNec, pancreatic necrosis; SAP, severe AP.

a ROC curve of severity b ROC curve of severity

1.00 1.00

Criteria Criteria

0.75 BISAP 0.75 BISAP

Ranson’s APACHE-II

Sensitivity

Sensitivity

0.50 0.50

0.25 0.25

0.00 0.00

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00 0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

1–Specificity 1–Specificity

Figure 1. Pairwise AUC comparison of BISAP with Ranson’s and APACHE-II scores in predicting severe disease. (a) Pairwise area under the receiver-

operating curve (AUC) comparison of bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis (BISAP) and Ranson’s scores in predicting severe AP (SAP).

(b) Pairwise AUC comparison of BISAP and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination (APACHE)-II scores in predicting SAP.

Table 3. Incidence of SAP, PNec, and mortality stratified by BISAP score, Ranson’s, APACHE-II, and CTSI with corresponding OR

Number of patients SAP PNec Mortality

BISAP

≤2 159 25 (15.7%) 24 (15.1%) 3 (1.9%)

>3 26 15 (57.7%) 12 (46.2%) 4 (15.4%)

OR (CI) 7.3 (2.7–19.6) 4.8 (1.8 –12.7) 9.5 (1.5 – 67.4)

Ranson’s

≤2 131 6 (4.6%) 7 (5.3%) 0 (0%)

>3 47 32 (68.0%) 24 (51.1%) 7 (14.9%)

OR (CI) 44.4 (14.7–146.5) 18.5 (6.6 – 55.7) 49.2 (4.0 – 244.7)

APACHE-II

<7 112 11 (9.8%) 11 (9.8%) 0 (0%)

>8 66 26 (39.4%) 19 (28.8%) 7 (10.6%)

OR (CI) 6.0 (2.5 –14.6) 3.7 (1.5 – 9.3) 28.6 (2.3 –141.8)

CTSI

<2 76 5 (6.6%) 1 (1.3%) 0 (0%)

>3 59 30 (50.8%) 35 (59.3%) 5 (8.5%)

OR (CI) 14.7 (4.9 – 52.1) 72.9 (13.4 – 397.7) 15.4 (1.2 –73.4)

APACHE-II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination-II; BISAP, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis; CI, confidence interval; CTSI, computed

tomography severity index; OR, odds ratio; PNec, pancreatic necrosis; SAP, severe AP.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 105 | FEBRUARY 2010 www.amjgastro.com

Comparison of BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE, and CTSI Scores 439

Table 4. Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of different scoring systems in predicting SAP, PNec, and mortality

% Sensitivity (95% CI) Specificity (95% CI) PPV (95% CI) NPV (95% CI)

PANCREAS

Severity

BISAP 37.5 (24.2 – 53.0) 92.4 (86.9 – 95.7) 57.7 (38.9 –74.5) 84.3 (77.8 – 89.1)

Ranson’s 84.2 (69.6 – 92.6) 89.8 (83.6 – 93.8) 69.6 (55.2 – 80.9) 95.3 (90.2– 97.9)

APACHE-II 70.3 (54.2 – 82.5) 71.9 (64.0 –78.7) 40.0 (29.0 – 52.1) 90.1 (83.1– 94.4)

CTSI 85.7 (70.6 – 93.7) 71.0 (61.5 –79.0) 50.8 (34.4 – 63.2) 93.4 (85.5 – 97.2)

PNec

BISAP 33.3 (20.2 – 49.7) 90.6 (84.8 – 94.3) 46.2 (28.8 – 64.5) 84.9 (78.5 – 89.6)

Ranson’s 77.4 (60.2 – 88.6) 88.4 (82.0 – 92.7) 52.2 (38.1– 65.9) 94.6 (89.2– 97.3)

APACHE-II 63.3 (45.5 –78.1) 68.5 (60.6 –75.5) 29.2 (19.6 – 41.2) 90.1 (83.1– 94.4)

CTSI 97.2 (85.8 – 99.5) 75.8 (66.5 – 83.1) 59.3 (46.6 –70.9) 98.7 (92.9 – 99.8)

Mortality

BISAP 57.1 (25.0 – 84.2) 87.6 (82.0 – 91.7) 15.4 (6.2– 33.5) 98.1 (94.6 – 99.4)

Ranson’s 100 (64.6 –100) 76.8 (69.8 – 82.5) 15.2 (7.6 – 23.2) 100 (97.1–100)

APACHE-II 100 (64.6 –100) 65.7 (58.2 – 72.4) 10.8 (5.3 – 20.6) 100 (96.7–100)

CTSI 100 (56.6 –100) 58.5 (49.9 – 66.6) 8.5 (3.7–18.4) 100 (95.2 –100)

APACHE-II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Examination-II; BISAP, bedside index for severity in acute pancreatitis; CI, confidence interval; CTSI, computed

tomography severity index; NPV, negative predictive value; PNec, pancreatic necrosis; PPV, positive predictive value; SAP, severe AP.

scoring systems in predicting SAP, PNec, and mortality are especially in the early identification of patients with AP

seen in Table 4. at increased risk of in-hospital mortality (14). BISAP uses

findings of physical examination, vital signs, routine lab-

oratory data, and imaging findings to derive a five-point

DISCUSSION score (15). It has been proposed that the primary advantage

In this study, we compared the accuracy of three repre- of BISAP to the “traditional” scoring systems is simplicity.

sentative prognostic multifactorial scoring systems and the However, our experience from this study is that the calcu-

new BISAP system in a prospectively collected cohort of lation of the BISAP score is more complicated than previ-

patients with AP. We confirmed that the newly proposed ously suggested. Even though, this is a five-point index,

BISAP index is a reliable means of stratifying patients with SIRS calculation require the collection of multiple variables

AP within 24 h from admission. In our cohort, the BISAP (see Introduction); making it an eight-variable system to

score performed similar to the three “traditional” clinical calculate five points.

scoring systems. Ranson’s score is composed of 11 measures that are recorded

This study was conducted at two tertiary care hospitals of the as binary values on admission and at 48 h, and its primary aim

University of Pittsburgh. The overall mortality in our cohort was to evaluate the function of early operative intervention in

was 3.8%, and 15.4% of the patients had a BISAP score ≥3. Our patients with AP (9). A composite score of 3 or more is com-

cohort was appropriate for comparing BISAP point-score strat- monly used to classify a patient as having severe disease. An

ification and the mortality rates with the tertiary care single- analysis of the components of Ranson’s score reveals that it is

center study performed at the Brigham and Woman’s Medical weighted toward detecting multiorgan failure linked to sys-

Center in Boston (mortality 3.5% and BISAP ≥3: 14.4%) (15). temic inflammatory response and vascular leak syndromes.

As expected, the proportion of patients with severe disease in Another commonly used severity index is the APACHE-II

our cohort was higher than the initial population-based study index (11,12). This clinical tool measures the physiological

(mortality 1.2% and BISAP ≥3: 9.9%), which used data col- response to injury- and inflammation-driven stress and was

lected from both community hospitals and tertiary care centers initially designed to predict prolonged intensive care unit

(14). Because only a very small number of patients died in our treatment and mortality.

cohort (n = 7), all results related to mortality should be evalu- BISAP has the advantage over Ranson’s score of being cal-

ated with caution. culated within 24 h of admission. BISAP appears to be more

BISAP is a newly developed prognostic scoring system, heavily weighted toward the immune response to injury and

which was reported to perform well in preliminary studies, older age (>60 vs. >55 years with higher likelihood of elderly

© 2010 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

440 Papachristou et al.

being confused or disoriented), whereas Ranson’s scoring biomarkers, which measure each of the potentially pathologic

system seems to perform with higher accuracy in the predic- steps and are linked to specific end points and outcomes, may

tion of persistent organ dysfunction over 48 h. Thus, BISAP be required. Additional structured analysis may be needed to

PANCREAS

may be disadvantaged in that it cannot easily distinguish determine the effect of interacting pathways and the impact of

transient organ dysfunction from persistent organ dysfunc- multiple factors in accurately predicting specific outcomes on

tion at 24 h (sensitivity of 38%, specificity 92%, PPV 58%, a patient-by-patient basis. Currently, all of the major scoring

and NPV 84%), with the latter group suffering nearly all of systems, including BISAP, use threshold values to change con-

the morbidity and morality of AP (20). On the other hand, tinuous variables into binary values, and use the binary values

BISAP score may be useful in the triage of patients to closer as equally weighted “points” to calculate a score. This second

observation and intensive care on initial evaluation rather derivative is then used to classify an episode of pancreatitis as

than being used to assess persistent organ failure and its mild or severe, again based on selection of a cutoff value and

consequences. dependent on the definition of “severe”. The limitations of the

In this study, the Ranson’s score performed well (sensitivity first step are shown by the use of artificial neural networks that

of 84%, specificity 90%, PPV 70%, and NPV 95%), as we used outperform Ranson’s score, APACHE-II, and similar systems

a definition of SAP based on presence of organ dysfunction for using the same data sets (23). The limitations of the second

at least 48 h. In contrast, Ranson’s score has performed with step may be shown by the current analysis, in which it appears

moderate accuracy in previous studies, especially when sever- that Ranson’s score outperforms BISAP based on our defini-

ity was defined by the Atlanta Criteria, which also include local tion of severity.

pancreatic injury in the definition of severity. A meta-analysis In conclusion, BISAP is a reliable prognostic tool to classify

encompassing 1,300 patients reported that Ranson’s score has patients with AP into mild and severe groups, and its com-

an overall sensitivity of 75%, specificity 77%, PPV of 49%, and ponents are clinically relevant and easy to obtain. However,

NPV of 91% (3). However, the low PPV of Ranson’s score in when used to assess persistent organ dysfunction, PNec, and

these studies may only reflect that half of the patients with a mortality, the BISAP index was not found to be either sim-

score ≥3 did not meet the definition of severe disease that was pler or more accurate than the existing multifactorial scoring

chosen for patient classification. On the other hand, inclusion systems in our cohort. The limitation of all scoring systems

of similar measures for the calculation of Ranson’s score and discussed here may be that they convert continuous variables

the definition of severity, as in our study, may bias the results into binary values of equal weight, and fail to capture syn-

favorably compared to other scoring systems in terms of per- ergistic or multiplicative effects based on the interactions of

formance characteristics. On stepwise comparison, APACHE- interdependent systems. Future research could focus on com-

II score performed similar to BISAP, as reported in previous prehensive reassessment of the pathologic mechanisms of AP

studies (14). with attention to the effects of preexisting risk factors (eg, age,

All the above multifactorial clinical scoring systems have obesity, genetic factors) and well-defined end points, identifi-

been very helpful in evaluating the severity of AP and start- cation of accurate biomarkers to assess activity on these path-

ing with Ranson’s score, and have been used for over three ways, and mathematical models that have strong predictive

decades to assess AP severity. However, the overall disadvan- accuracy.

tage of such scoring systems, including the BISAP, is that they

are not designed to predict potentially preventable compli- CONFLICT OF INTEREST

cations in AP, and are least useful in the middle prediction Guarantor of the article: Georgios I. Papachristou, MD.

range where the clinician needs most guidance. Therefore, Specific author contributions: Georgios I. Papachristou:

their use seems to be confined in medical decision-making conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis

at the extreme of the prediction range, such as triaging inten- and interpretation of data, drafting of the paper, and obtain-

sive care unit admission (20,21), and as enrollment criteria for ing funding; Venkata Muddana: acquisition and analysis of

clinical trials. data and drafting of the paper; Dhiraj Yadav: analysis and

AP is a dynamic and evolving process that involves multi- interpretation of data and drafting of the paper; Michael

ple systems and the risk for multiple organ complications. O’Connell: statistical analysis; Michael K. Sanders: interpreta-

Despite the complex and highly variable nature of AP, the tion of data and drafting of the paper; Adam Slivka: critical

evaluation of the dynamic steps involved and the prediction revision of the paper for important intellectual content and

of future outcomes have followed the simplistic approach supervision; David C. Whitcomb: critical revision of the

of Ranson et al. (9,10) in dividing all patients with AP into paper for important intellectual content, obtaining funding,

one of two categories—mild and severe. The Atlanta classifi- and supervision.

cation has not significantly contributed to our understand- Financial support: This work was supported by the VA Stars

ing of this dynamic process by classifying patients as mild or and Stripes Healthcare Network 2007 Competitive Pilot

severe, based on a wide variety of criteria and end points (22). Project Fund (GIP).

To improve the predictive accuracy of clinical tools, series of Potential competing interests: None.

The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY VOLUME 105 | FEBRUARY 2010 www.amjgastro.com

Comparison of BISAP, Ranson’s, APACHE, and CTSI Scores 441

Study Highlights 6. Whitcomb DC. Clinical practice. Acute pancreatitis. N Engl J Med

2006;354:2142–50.

7. Fagenholz PJ, Castillo CF, Harris NS et al. Increasing United States hospital

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE admissions for acute pancreatitis, 1988–2003. Ann Epidemiol 2007;17:491–7.

3 8. Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J

PANCREAS

The individual patient response to pancreatic injury is

Gastroenterol 2006;101:2379–400.

highly variable and often unpredictable. 9. Ranson JH, Rifkind KM, Roses DF et al. Objective early identification of

3Traditional prognostic clinical scoring systems, such as severe acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol 1974;61:443–51.

10. Ranson JH, Pasternack BS. Statistical methods for quantifying the severity

Ranson’s and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health

of clinical acute pancreatitis. J Surg Res 1977;22:79–91.

Examination (APACHE)-II, have been helpful in evaluating

11. Yeung YP, Lam BY, Yip AW. APACHE system is better than Ranson system

the severity of acute pancreatitis (AP) and have been in the prediction of severity of acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat

used for three decades. Dis Int 2006;5:294–9.

3A new prognostic scoring system, the bedside index 12. Larvin M, McMahon MJ. APACHE-II score for assessment and monitoring

of acute pancreatitis. Lancet 1989;2:201–5.

for severity in AP (BISAP), has been proposed as an

13. Balthazar EJ, Roinson DL, Megibow AJ et al. Acute pancreatitis: value of CT

accurate method for early identification of patients at in establishing prognosis. Radiology 1990;174:331–6.

risk for in-hospital mortality. 14. Wu BU, Johannes RS, Sun X et al. The early prediction of mortality in acute

WHAT IS NEW HERE pancreatitis: a large population-based study. Gut 2008;57:1698–703.

15. Singh VK, Wu BU, Bollen TL et al. A prospective evaluation of the bedside

3We confirmed that the BISAP score is an accurate index for severity in acute pancreatitis score in assessing mortality and

means for risk stratification in patients with AP. Its com- intermediate markers of severity in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol

ponents are clinically relevant and easy to obtain. 2009;104:966–71.

3The prognostic accuracy of BISAP is similar to those of

16. Mofidi R, Duff MD, Wigmore SJ et al. Association between early systemic

inflammatory response, severity of multiorgan dysfunction and death in

the other scoring systems. acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2006;93:738–44.

3Clinical scoring systems may have reached their 17. Buter A, Imrie CW, Carter CR et al. Dynamic nature of early organ dysfunc-

tion determines outcome in acute pancreatitis. Br J Surg 2002;89:298–302.

maximal utility and novel models are needed to further

18. Papachristou GI, Papachristou DJ, Avula H et al. Obesity increases the

improve early predictive accuracy in patients with AP. severity of acute pancreatitis: performance of APACHE-O score and cor-

relation with the inflammatory response. Pancreatology 2006;6:279–85.

19. DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under

two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonpara-

REFERENCES metric approach. Biometrics 1988;44:837–45.

1. Papachristou GI, Clermont G, Sharma A et al. Risk and markers of severe 20. Zimmerman JE, Rousseau DM, Duffy J et al. Intensive care at two

acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2007;36:277–96, viii. teaching hospitals: an organizational case study. Am J Crit Care

2. Swaroop VS, Chari ST, Clain JE. Severe acute pancreatitis. JAMA 1994;3:129–38.

2004;291:2865–8. 21. Papachristou GI. Prediction of severe acute pancreatitis: current knowledge

3. Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreati- and novel insights. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:6273–5.

tis. Gastroenterology 2007;132:2022–44. 22. Bradley EL III. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis.

4. Hughes SJ, Papachristou GI, Federle MP et al. Necrotizing pancreatitis. Arch Surg 1993;128:586–90.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2007;36:313–23, viii. 23. Atkinson AJJ, Colburn WA, DeGruttola VG et al. Biomarkers and surrogate

5. Isenmann R, Beger HG. Natural history of acute pancreatitis and the role of endpoints: preferred definitions and conceptual framework. Clin Pharmacol

infection. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 1999;13:291–301. Ther 2001;69:89–95.

© 2010 by the American College of Gastroenterology The American Journal of GASTROENTEROLOGY

You might also like

- The 4 Hour Work SummaryDocument6 pagesThe 4 Hour Work SummaryhgfhgNo ratings yet

- IE54500 - Exam 1: Dr. David Johnson Fall 2020Document7 pagesIE54500 - Exam 1: Dr. David Johnson Fall 2020MNo ratings yet

- Generative NLP Robert Dilts PDFDocument11 pagesGenerative NLP Robert Dilts PDFCristina LorinczNo ratings yet

- Reinstatement Management PlanDocument38 pagesReinstatement Management Planvesgacarlos-1No ratings yet

- NDX DolsonDocument67 pagesNDX DolsonMahanta BorahNo ratings yet

- PRISM ScoreDocument13 pagesPRISM ScoreTammy Utami DewiNo ratings yet

- WWW - Smccnasipit.edu - PH: Saint Michael College of CaragaDocument5 pagesWWW - Smccnasipit.edu - PH: Saint Michael College of CaragaDivine CompendioNo ratings yet

- Mathematics 9 DLPDocument10 pagesMathematics 9 DLPAljohaila GulamNo ratings yet

- AP Early MortalityDocument7 pagesAP Early MortalityarifNo ratings yet

- Kjim 28 322Document8 pagesKjim 28 322Fiaz medicoNo ratings yet

- Thesis TopicsDocument14 pagesThesis TopicskiranNo ratings yet

- The Golden Hours in Treatment Am J Gastroenterol 2012 Aug 107 (8) 1146Document5 pagesThe Golden Hours in Treatment Am J Gastroenterol 2012 Aug 107 (8) 1146hojadecoca1313No ratings yet

- Iarjmsr 1 (3) 116-120Document5 pagesIarjmsr 1 (3) 116-120jinuNo ratings yet

- Blood Urea Nitrogen in The Early Assessment of Acute PancreatitisDocument8 pagesBlood Urea Nitrogen in The Early Assessment of Acute PancreatitisRicardo Uzcategui ArreguiNo ratings yet

- Modelo Preictivo PancreatitisDocument9 pagesModelo Preictivo PancreatitisJesus PugaNo ratings yet

- Articulo GuiaDocument12 pagesArticulo GuiaEduardo miñanoNo ratings yet

- Classifying Patients Suspected of Appendicitis With Regard To LikelihoodDocument6 pagesClassifying Patients Suspected of Appendicitis With Regard To LikelihoodabybmusNo ratings yet

- REZUMAT TEZĂ - EnglpetreDocument27 pagesREZUMAT TEZĂ - EnglpetreDaniel StaniloaieNo ratings yet

- Lactated Ringer Solution Is Superior To Normal Saline Solution in Managing Acute PancreatitisDocument7 pagesLactated Ringer Solution Is Superior To Normal Saline Solution in Managing Acute PancreatitisJulieth QuinteroNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Prognostic Markers in Acute Pancreatitis: Internist 'S Point of ViewDocument9 pagesThe Challenge of Prognostic Markers in Acute Pancreatitis: Internist 'S Point of ViewGdfgdFdfdfNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of 880 Patients Diagnosed With Acute Pancreatitis According To The Revised Atlanta Classification: A Single-Center ExperienceDocument6 pagesEvaluation of 880 Patients Diagnosed With Acute Pancreatitis According To The Revised Atlanta Classification: A Single-Center ExperienceGabriel PessoaNo ratings yet

- Antibiotic Timing Sepsis MortalityDocument15 pagesAntibiotic Timing Sepsis MortalityRichard BunNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Acute Kidney Injury in Acute Pancreatitis: Riginal RticleDocument6 pagesRisk Factors For Acute Kidney Injury in Acute Pancreatitis: Riginal RticleDavid Sebastian Boada PeñaNo ratings yet

- Acute PancreatitsiDocument8 pagesAcute PancreatitsiAnty FftNo ratings yet

- Vaugh Alimentacio nPancreatitisAguda AnnInternMed 2017-2Document15 pagesVaugh Alimentacio nPancreatitisAguda AnnInternMed 2017-2Paula RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Vital-Sign Abnormalities As Predictors of Pneumonia in Adults With Acute Cough IllnessDocument6 pagesVital-Sign Abnormalities As Predictors of Pneumonia in Adults With Acute Cough IllnessMazKha BudNo ratings yet

- Indicación RelaparotomiaDocument6 pagesIndicación RelaparotomiaJohnHarvardNo ratings yet

- Índice Clínico de Gravedad en Pancreatitis Aguda: BISAP ("Bedside Dos Años de Experiencia en El Hospital Clínico Universidad de ChileDocument7 pagesÍndice Clínico de Gravedad en Pancreatitis Aguda: BISAP ("Bedside Dos Años de Experiencia en El Hospital Clínico Universidad de ChileChristian QuantNo ratings yet

- Bowel Ultrasound For Predicting Surgical Management of Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesBowel Ultrasound For Predicting Surgical Management of Necrotizing Enterocolitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisPukaatiq DionisioNo ratings yet

- Wong1991 PDFDocument10 pagesWong1991 PDFBeladiena Citra SiregarNo ratings yet

- Early Enteral Nutrition Compared With Parenteral Nutrition For Esophageal Cancer Patients After Esophagectomy: A Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesEarly Enteral Nutrition Compared With Parenteral Nutrition For Esophageal Cancer Patients After Esophagectomy: A Meta-AnalysisEndah Rahayu MulyaniNo ratings yet

- American College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute PancreatitisDocument16 pagesAmerican College of Gastroenterology Guidelines: Management of Acute PancreatitisCarinka VidañosNo ratings yet

- En - 2308 0531 RFMH 20 04 574Document7 pagesEn - 2308 0531 RFMH 20 04 574Jhonatan GroverNo ratings yet

- March 2015 1492842860 67Document4 pagesMarch 2015 1492842860 67Jhanu JaguarNo ratings yet

- Medical ScienceDocument14 pagesMedical Sciencerppawar_321203003No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0090429522003478 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0090429522003478 MainMisna AriyahNo ratings yet

- L Arvin 1989Document5 pagesL Arvin 1989Ciprian SebastianNo ratings yet

- 00005Document11 pages00005Oscar PerezNo ratings yet

- Diagnostics 12 01974 v2Document35 pagesDiagnostics 12 01974 v2leizer RoblesNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Radio 2Document9 pagesJurnal Radio 2Wahyu ApriantoNo ratings yet

- Sofa ScoreDocument6 pagesSofa ScoreNadiah Umniati SyarifahNo ratings yet

- Early Laboratory Biomarkers For Severity in Acute PancreatitisDocument10 pagesEarly Laboratory Biomarkers For Severity in Acute PancreatitisRoberto MaresNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s11605 019 04424 5Document8 pages10.1007@s11605 019 04424 5Rika Sartyca IlhamNo ratings yet

- Journal of Critical CareDocument8 pagesJournal of Critical CareMuhammad HidayantoNo ratings yet

- Risk of Venous Thromboembolism in Acute.10Document6 pagesRisk of Venous Thromboembolism in Acute.10Dr WittyNo ratings yet

- Etm 07 03 0604Document5 pagesEtm 07 03 0604Raissa Metasari TantoNo ratings yet

- Deniz 2022Document10 pagesDeniz 2022syakurNo ratings yet

- SMART-COP - A Tool For Predicting The Need For Intensive Respiratory or Vasopressor Support in Community-Acquired PneumoniaDocument10 pagesSMART-COP - A Tool For Predicting The Need For Intensive Respiratory or Vasopressor Support in Community-Acquired PneumoniaelhierofanteNo ratings yet

- Bedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) Score For Predicting Prognosis in Acute PancreatitisDocument9 pagesBedside Index of Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (BISAP) Score For Predicting Prognosis in Acute PancreatitisEditor_IAIMNo ratings yet

- PB3 7820 R2Document10 pagesPB3 7820 R2Lissaberti AmaliahNo ratings yet

- Zhao, 2021 PDFDocument10 pagesZhao, 2021 PDFiaw iawNo ratings yet

- Procalcitonin Is It The End of Road To Sepsis Diagnosis - February - 2022 - 6546541022 - 2629943Document2 pagesProcalcitonin Is It The End of Road To Sepsis Diagnosis - February - 2022 - 6546541022 - 2629943RateeshNo ratings yet

- Buck 2011Document9 pagesBuck 2011siti hanifahNo ratings yet

- Application of A Modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score To Critically Ill PatientsDocument8 pagesApplication of A Modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score To Critically Ill Patientssonali boranaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S0300957218309092 Main PDFBirhanu MuletaNo ratings yet

- 2017 Article 591Document7 pages2017 Article 591Denisse Tinajero SánchezNo ratings yet

- Mortality and Overall and Specific Infection Complication Rates inDocument11 pagesMortality and Overall and Specific Infection Complication Rates inKarla LapendaNo ratings yet

- Correlation of The International Prostate Symptom Score Bother Question With The Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index in A Clinical Practice SettingDocument7 pagesCorrelation of The International Prostate Symptom Score Bother Question With The Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Impact Index in A Clinical Practice SettingAuliadi AnsharNo ratings yet

- Comparitive Study of Panc-3 and Bedside Index For Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (Bisap) Scoring System To Identify Severity of PancreatitisDocument10 pagesComparitive Study of Panc-3 and Bedside Index For Severity in Acute Pancreatitis (Bisap) Scoring System To Identify Severity of PancreatitisIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- The Ideal Time Interval For Critical Care Severity-of-Illness AssessmentDocument6 pagesThe Ideal Time Interval For Critical Care Severity-of-Illness AssessmentAdlla SwanNo ratings yet

- Meta-Analysis On The Efficacy of High-Dose Statin Loading Before Percutaneous CoronaryDocument8 pagesMeta-Analysis On The Efficacy of High-Dose Statin Loading Before Percutaneous CoronaryPir Mudassar Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- SAPS in Acta Medica AcademicaDocument7 pagesSAPS in Acta Medica AcademicaAminaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0009898118300500 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0009898118300500 MainMohamed AmineNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Accuracy of Presepsin For Sepsis by The New Sepsis-3 DefinitionDocument6 pagesDiagnostic Accuracy of Presepsin For Sepsis by The New Sepsis-3 Definitionfaraz.mirza1No ratings yet

- Core Concepts in Acute Kidney InjuryFrom EverandCore Concepts in Acute Kidney InjurySushrut S. WaikarNo ratings yet

- Precision in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine: A Clinical and Research GuideFrom EverandPrecision in Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine: A Clinical and Research GuideJose L. GomezNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Criteria and Severity Grading of Acute J Hepato Biliary Pancreat - 2017 - Kiriyama - Tokyo Guidelines 2018Document14 pagesDiagnostic Criteria and Severity Grading of Acute J Hepato Biliary Pancreat - 2017 - Kiriyama - Tokyo Guidelines 2018Muhammad RifkiNo ratings yet

- Prediction of Outcome in Acute Pancreatitis by The qSOFA and The New ERAP ScoreDocument8 pagesPrediction of Outcome in Acute Pancreatitis by The qSOFA and The New ERAP ScoreLeopoldo MagañaNo ratings yet

- 3939 Whitcomb CRNP AGA Aug2014Document27 pages3939 Whitcomb CRNP AGA Aug2014Leopoldo MagañaNo ratings yet

- Autoimmune Pancreatitis - Sajan NagpalDocument9 pagesAutoimmune Pancreatitis - Sajan NagpalLeopoldo MagañaNo ratings yet

- 003 Users Manuel of Safir 2016 - MechanicalDocument74 pages003 Users Manuel of Safir 2016 - Mechanicalenrico_britaiNo ratings yet

- TanDocument8 pagesTanShourya RathodNo ratings yet

- R.M. M, J. C, S.L. I S.M. H R C. M P J. M G : Aier Horover Verson AND Ayes Odney Aier and Eter C OldrickDocument1 pageR.M. M, J. C, S.L. I S.M. H R C. M P J. M G : Aier Horover Verson AND Ayes Odney Aier and Eter C OldrickPeter McGoldrickNo ratings yet

- Engineering Physics - PHY 1701 N. Punithavelan, Assistant Professor, Physics Division, VIT-ChennaiDocument6 pagesEngineering Physics - PHY 1701 N. Punithavelan, Assistant Professor, Physics Division, VIT-ChennaiRamyasai MunnangiNo ratings yet

- (IMP) Ancient Indian JurisprudenceDocument28 pages(IMP) Ancient Indian JurisprudenceSuraj AgarwalNo ratings yet

- h1 Styleclearboth Idcontentsection0the Only Guide To Commercial Fisheries Reviewh1jbfch PDFDocument14 pagesh1 Styleclearboth Idcontentsection0the Only Guide To Commercial Fisheries Reviewh1jbfch PDFgalleymark22No ratings yet

- OLET1139 - Essay - July 21 - InstructionDocument3 pagesOLET1139 - Essay - July 21 - InstructionPriscaNo ratings yet

- Multifocal AntennaDocument5 pagesMultifocal AntennaLazni NalogNo ratings yet

- Final Exam For EappDocument2 pagesFinal Exam For EappReychel NecorNo ratings yet

- Skills Development PlanDocument1 pageSkills Development PlanJES MARIES MENDEZNo ratings yet

- ADM - DIASS 11 Q4 Weeks 1-8 - LatestDocument28 pagesADM - DIASS 11 Q4 Weeks 1-8 - LatestjoyceNo ratings yet

- Soal TPS Bahasa InggrisDocument3 pagesSoal TPS Bahasa InggrisMaya Putri EkasariNo ratings yet

- StringDocument4 pagesStringAadyant BhadauriaNo ratings yet

- Abstract On Face Recognition TechnologyDocument1 pageAbstract On Face Recognition TechnologyParas Pareek60% (5)

- Gravity Distribution Systems: A System Design and ConstructionDocument40 pagesGravity Distribution Systems: A System Design and ConstructionTooma DavidNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology and Biostatistics - Syllabus & Curriculum - M.D (Hom) - WBUHSDocument5 pagesResearch Methodology and Biostatistics - Syllabus & Curriculum - M.D (Hom) - WBUHSSumanta KamilaNo ratings yet

- Ficha Tecnica: KN 95 (Non - Medical)Document13 pagesFicha Tecnica: KN 95 (Non - Medical)Luis Buitrón RamírezNo ratings yet

- DSS+ SH Risk Management HandbookDocument20 pagesDSS+ SH Risk Management HandbookAlan PicazzoNo ratings yet

- Mai 4.9 Discrete DistributionsDocument16 pagesMai 4.9 Discrete DistributionsAvatNo ratings yet

- SP Q4 Week 2 HandoutDocument10 pagesSP Q4 Week 2 HandoutLenard BelanoNo ratings yet

- Reduced Adjective ClausesDocument1 pageReduced Adjective Clausesmetoeflgrammar100% (1)

- FNCPDocument3 pagesFNCPDarcey NicholeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8Document3 pagesChapter 8JULLIE CARMELLE H. CHATTONo ratings yet