Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hojaqizi - Citizenship and Ethnicity

Hojaqizi - Citizenship and Ethnicity

Uploaded by

Rano TuraevaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hojaqizi - Citizenship and Ethnicity

Hojaqizi - Citizenship and Ethnicity

Uploaded by

Rano TuraevaCopyright:

Available Formats

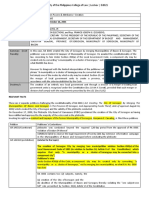

Citizenship and Ethnicity: Old Propiska and New Citizenship in Post-Soviet Uzbekistan

Author(s): GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

Source: Inner Asia, Vol. 10, No. 2 (2008), pp. 305-322

Published by: BRILL

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23615099 .

Accessed: 29/01/2015 09:34

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

BRILL is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Inner Asia.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Citizenship and Ethnicity: Old Propiska and New

Citizenship in Post-Soviet Uzbekistan

GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

Independent Researcher

ABSTRACT

This paper looks at two modes of 'belonging' in Uzbekistan: the firstas a full cit

izen and the second as an 'illegal' resident of the place, these being two different

ways of perceiving oneself as an Uzbek citizen. It is of crucial importance to con

sider the direct effect of existing internal registration regulations (propiska) on

the self-perception of being a citizen and an Uzbek. I argue that this local policy,

together with the failure of citizenship, has led to other kinds of memberships

within non state institutions. The overarching Uzbek national identity has

become a formal cover and an instrument for political discourse only at a higher

level. At the lower level, as local discourses indicate, 'ethnic' or regional net

works and identities have been strengthened and regained their importance in the

everyday lives of people in Uzbekistan. I will make use of contemporary

approaches to the studies of citizenship that focus on the experiences of citizens

and social constmction of citizenship frombelow. The data used in the article was

collected as part of fieldwork of thirteen months conducted in Uzbekistan.

Key words: citizenship, ethnic networks, nationalism,propiska

INTRODUCTION

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Uzbekistan faced numerous chal

lenges building an independent state. The Uzbek government system remains a

mirror image of its predecessor and is arguably a continuation of the soviet

regime in post-Soviet Central Asia (Humphrey 2002; Hann 1998,2002; Tishkov

1997). Humphrey (2002: 12) rightlypointed out:

First, there can never be a sudden and total emptying out of all social phenomena

and their replacement by other ways of life. Second, what Rudolf Bahro called

'actually existing socialism' was a deeply pervasive phenomenon, existing not

only as practices but also as public and covert ideologies and contestations. A third

assumption, more disputed perhaps, is that 'actually existing socialism' had a cer

tain foundational unity, derived in its public ideology from Marx and in its

dominant political practice from Lenin.

InnerAsia 10 (2008): 305-22

© 2008 Global Oriental Ltd

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

306 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

One salient difference between contemporary Uzbekistan and the Soviet era,

however, is the welfare system. During the Soviet era, the welfare system met

certain minimal guarantees in provisioning its citizens. In contemporary

Uzbekistan, it has fallen apart along with the other so-called advantages of the

Soviet system. The welfare system is one of the key functions of the state in pro

viding for its citizens. The lack of welfare support from the state has prompted

the decay in the importance and meaning of the sense of belonging to the state or

being part of the civil society. People have to search for other types of belonging

and support which is kinship or ethnic1and regional affiliations.2

Uzbekistan cherishes the centralised system of government it inherited from

the Soviet Union. The centralised political system established by the Bolsheviks

as an effective control-mechanism has remained in place; it was even expanded

to further strengthen the control by the post-Soviet Uzbek government.3

Resources in post-Soviet Uzbekistan are still allocated according to the old

Soviet doctrine of 'one city centralisation'. Under this policy, the government

allocates a disproportionate amount of investment to the capital city of Tashkent,

to the detriment of other cities and regions. Compared to other cities in

Uzbekistan, Tashkent has better employment opportunities, better medical care

facilities, better secondary education, and better services. Outside the capital city

all of these resources are in poor condition or even absent. All of the main offices

of businesses and international organisations are concentrated in the capital city.

This has led to extreme levels of poverty in the rural areas of the country and has

prompted out-migration from various regions with people mainly moving to

Tashkent. Ilkhamov (2001: 53), in his article about the creation of the 'new poor'

in Uzbekistan, identifies the huge gap that has been created between rich and

poor, rural and urban populations. He estimates that in the eight years before

2001, 90,000 people migrated annually to the capital, a total of half a million

people.

Migration to the capital, however, is not necessarily a matter of free choice.

Registration requirements forbid the free movement of people within

Uzbekistan. Nevertheless, internal migration, even in contravention of local

laws, has made Tashkent the most ethnically diverse city in the country. People

therefore have to develop strategies to establish themselves in the capital, either

legally or illegally. This requires specialised knowledge and access to social net

works. On the one hand, people have to resort to institutions and policies of

Soviet origin where propiska (residence permit)4 is of cmcial importance in this

context. On the other hand, networks of families, kin and friends come together,

supporting each other, organising day-to-day life and even reviving aspects of

regional culture in Tashkent. In the Soviet Union, the propiska and the internal

passport regime5 were legitimised as strategies to ensure and control the 'proper'

mixing of the population. The official aim was thus an internationalisation and

Sovietisation of the population of the Soviet Union. At the same time, the over

population of 'closed cities' (settlements with travel and residency restrictions)

(Buckley 1995: 905) was to be prevented (Suny 1999; Brubaker 1994;

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

307 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

Hôjdestrand 2003). 'Closed cities' were mainly the central cities that have

attracted more people than other cities due to the economic and other incentives.

Therefore the registration requirements in those cities were more restricted and

limited (Buckley 1995).

Uzbekpropiska policy has been inheritedfromthe Soviet system and took on

another meaning and nature in the regulation of citizens' mobility in Uzbekistan.

Thanks to internal regulations to 'improve a [proper] registration of citizens of

the Republic of Uzbekistan'6 it became almost impossible to obtain propiska,

especially after 1999 when 'terrorist' bombings took place in the centre of

Tashkent. These restrictionson the mobility of Uzbek citizens within the territory

of their own country have made most migrants at least 'half legal' if not 'illegal'.

The official legislation of residence permits or local registration policies in

fact contradicts the Constitution of Uzbekistan. Thanks to a dual legislation

system7 the internal legislation includes all the amendments and additional rules

that are absent in the official legislation. Without a propiska document, a citizen

is deprived of his/her civil and social rights, including rights to employment,

property ownership, health care, secondary schooling and so on as dictated by the

Constitution. This, in Kabeer's (2005:18) phrasing, is a 'brutal denial of rightsto

the majority of citizens' by the state that challenges the notion of citizenship and

political/national belonging.

In this paper I will limit the discussion and focus on the effectsof Soviet and

post-Soviet policies on local communities and on the experiences of Uzbek 'citi

zens' as internal migrants. Everyday experiences of the Uzbek 'citizens' will be

analysed in the scope ofpractices of citizenship in order to shed light on the defi

nitions of citizenship.

CITIZENS AND 'CITIZENS': THEORETICAL DEBATES AND THEIR

IMPLICATIONS FOR UZBEK CITIZENSHIP

The debates over citizenship have regained strength in the aftermath of the Soviet

collapse. Recent theoretical approaches to citizenship 'from below' analyse citi

zenship on the basis of citizens' experiences of everyday life (Kabeer ibid.). I will

follow this approach in my examination of internal migrants.8

Kabeer (2002, 2005) focused on the aspects of citizenship that were ignored

so far and suggested an alternative way of theorising it 'from below', in other

words from the stand point of the experiences of those who are largely excluded.

She states in her edited volume Inclusive Citizenship that:

[...] theoretical debate about citizenship is taking place in an 'empirical void',

where the views of 'ordinary' citizens are largely absent. We do

and perspectives

not know what citizenship means to people - particularly people whose status as

citizens is either non-existent or extremely precarious - or what these

meanings

tell us about the goal of building inclusive societies (2005:1; emphasis added).

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

308 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

The debate on citizenship has usually been approached from a systemic level and

citizenship was initially the domain of political sciences while social sciences

mainly analysed citizenship on the macro level (Marshall 1950; Steward 1995:

63). The actor-centred perspective, which Kabeer (2005) and others have intro

duced, leads to quite different results from those that are gained from a systemic

perspective. This approach allows one to draw on both ordinary people's under

standing of being citizens and belonging to a state as well as expectations of the

state in the exchange for the rights granted to its citizens. As Kabeer (ibid.: 3)

rightlystated 'there are certain values that people associate with the idea of citi

zenship which cut across the various boundaries that divide them'. She continues

to argue that these values and ideas people have of citizenship are so widely

spread that they influence their 'organisation of collective life and the way in

which people connect with each other'. Hall and Williamson (1999: 2) argued in

a similar vein regarding understanding citizenship fromthe people's lived experi

ences and 'the meaning that citizenship actually has in people's lives and the

ways in which people's social cultural backgrounds and material circumstances

affecttheir lives as citizens'.

The results of the kind of approach mentioned above offer answers to ques

tions such as where the two poles of offeringand receiving citizenship meet, if

they ever do, and if not, how both sides account for this disparity. In other words:

do people enjoy the rights of being a citizen, and does the state meet citizens'

expectations. The state expectations are that citizens comply with the Western

normative scheme of state-citizen relations including the paying of taxes, serving

in the army, respecting laws, and so forth.

When the focus of the analysis is on the actual practices of citizenship this

calls for a wider definition of citizenship as for example Turner (1990, 1993)

defined it. He (1993: 2) understood citizenship as a '[...] set of practices

(juridical, political, economic and cultural) which define a person as a competent

member of society, and which as a consequence shape the flow of resources to

persons and social groups'. This type of definition of citizenship reveals its

dynamic character, since Turner adds that this 'changes historically as a conse

quence of political [or social] struggles' (ibid.). To my mind it is fruitfulto define

citizenship as 'practices' rather than 'a set of rights', since this underlines its

dynamic character from a bottom-up perspective. Turner (ibid.) used the term

'practices' in order to avoid fixing citizenship to 'a collection of rights and obli

gations'. I use the term 'practices' in the meaning of everyday life experiences of

citizenship by 'citizens' on the local level.

He argued against generalising principles on defining and analysing citizen

ship. Turner (ibid.: 9) located the concept in a regional context: 'The notion of

citizenship can be traced [...] through the national cultures of differentregions

and nation-states'. In other words, Turner has shown citizenship's

implications

for different'practices' that are regionally and culturally specific and

depend on

the historical development of the concept. Moreover it is of no less to

importance

see what are the meanings attached to the term in the local context its

considering

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

309 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

local history and political culture. Different locales produce different meanings

thatare historically and politically shaped.

The notion of citizenship is variously defined in different countries by use of

different terms that have different etymological origins in different cultures. For

example, the French term is derived from cité, which refers to individuals who

enjoy limited rights within a city. In German and Dutch the term is associated

with the idea of civil society (biirgerliche Gesellschaft) (Turner ibid.: 9). In

Uzbek the term citizen, fuqaro, is derived from the Arabic faqir, meaning

poor/underprivileged. One Uzbek-Russian dictionary (Akbarov: 1988) when

explaining the word, uses as an example a sentence thatis cited fromlocally pub

lished Uzbek texts: 'men sizga aytsam, bizning Qamishkapa eskidan uruqqa

ajrab keladi: faqir va hoja' (I tell you that our Qamishkapa9 is divided by uruq [a

tribe, or descent group] since earlier times: faqir and hoja).10 Initially the term

was used for the ordinary population, which was usually poor and unprivileged.

The past use of the word ironically matches its actual practice and of course con

tradictsto the ideals of citizenship envisioned by the state.

The notion of citizenship, in the sense of rightsto social welfare and partici

pation in political life of the state, was introduced by the Soviets in the territoryof

Central Asia. That is why the notion of citizenship as 'grajdanstvo' has entered

the region and was translated into Uzbek as fuqaro without much investigation of

the etymology of the word fuqaro. To be a Soviet citizen meant to be entitled to

social and legal rights within the territoryof the Soviet Union. Free education,

health care and housing was provided by the Soviet welfare system. Social

equality was a central item promoted by the Soviet state in order to achieve class

less society throughout the Soviet Union. The idea of citizenship was presented

and more or less introduced in the light of its equal accessibility to all the Soviet

citizens. Having an idea about what citizenship means does not necessarily coin

cide with its actual practices on the ground. The simple example would be that

the Constitution grants freedom of movement within one's own country which is

a basic prerogative of any citizen and the actual practice is not necessarily the

same.

The concept of citizenship imported to the region by Soviets was successfully

adopted by the local state. The state and citizen relationship did not continue even

at the level it was during the soviet times. This relationship startedto vanish with

the collapse of the Soviet Union and has become blurred at the present time. It has

been replaced with other kinds of bonds and relationships between citizens and,

now, between members to kinship or ethnic networks. These 'informal' institu

tions to some degree replaced the functions of the state in relation to their

citizens. This new form of membership has more or less provided the advantages

that ideally citizenship would grant. Desforges (2005) pointed to the importance

of considering citizenship within certain places and spaces as this concept is terri

torially and structurallybound. When theorising citizenship it is helpful to use the

geographical terms of spatiality and scales and I would consider citizenship as

territoriallybound in the Uzbek context. Uzbek citizens do have their minimum

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

310 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

entitlements as citizens, only at the particular locales where they have permanent

registration(propiska). Whenever they starttravelling outside of their region of

permanent residence within the same national territory their rights as citizens

become limited if not the same as non-citizens.

'THE PROPISKA IS THE FIRST THING TO DO AND ORGANISE

BEFORE COMING TO TASHKENT; OTHERWISE YOU CANNOT

COME AND LIVE HERE ... '11

Obtaining a propiska12 remains the biggest problem that a person faces when

deciding to move to Tashkent, particularly after 1999, when Tashkent was shaken

by explosions in the city centre and the government consequently tightened its

control over the city and country.Uzbekistan has a dual legislation system: 'offi

cial' (zakonniy) and internal (vnutrenniy).Official decrees and laws exist and are

available for the general public. Internal decrees are issued strictlyfor internal

use of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Uzbek security services but nonethe

less bind the people regardless of whether they know of the decree.

Article 28 of the Constitution of Uzbekistan says 'Any citizen of the Republic

of Uzbekistan shall have the rightto freedom of movement in the territoryof the

Republic, as well as a free entryto and exit from it, except in events specified by

law.' The new internal regulations that restrict free movement of the citizens

within the country by means of controlling the propiska contradict the principles

of the constitution.

Internal registration requirements, particularly those for the capital city, are

similar to the registration requirements for foreigners. Foreigners must register in

- and the same

every place where they stay for more than three days goes for Uzbek

citizens. There are two types of registration for propiska: short-term and perma

nent. A short-term propiska limits the rights of its holder in a manner

corresponding to the rights of short-term registrations for foreigners, who do not

have employment and property ownership rights. Any Uzbek citizen who leaves

his or her place of permanent residence must comply with the local registration

system and obtain a short-term propiska if she or he stays at a place for more than

three days. A short-term propiska is given for a maximum of six months but

presently official practice is to grant short-termpropiskas for no more than three

months. After each expiry of a short-term propiska one must get it renewed. In

order to obtain a short-term propiska one should provide written proof of a 'legiti

mate' reason for staying in the new place of residence such as education,

employment, sickness, family reasons, etc. It is possible to obtain short-term

propiska by paying an amount equal to two average monthly salaries in cases

where one cannot provide proof of the legitimate reason. Although in theory it is

possible to get a permanentpropiska, in practice it is extraordinarilydifficultifnot

impossible.

In order to comply with the law and obtain a permanent propiska, internal

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

311 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

migrants must provide proof of employment, recommendations from local

authorities or some proof that they have close family living in the region, where

they want to migrate to. The most important document necessary for obtaining

both short-term and permanent propiska is written and notarised agreement of the

owner of the flat or house where the applicant intends to reside for purposes of

registration. By agreeing to 'accommodate' a person in his/her private house or

flat the owner runs the risk of his propertybeing divided if the new 'inhabitant'

claims part of the house or flat. This is usually only in cases of permanent regis

tration in the house or flat. Short-term registration in any house could only cause

a short-term delay for selling it as the registered persons in any house or flat have

to be de-registered. All of this described registering and deregistering in private

homes is the result of the absence of Renting Contracts which are avoided by

owners of accommodation so that they do not have to pay taxes on the rent and

additionally the process of entering the rental business is time consuming and

bureaucratically difficult. Consequently it is not an easy task to find a volunteer

owning a house or flat who would agree to risk his/her property even if the

requester is a relative.

Every citizen of Uzbekistan must comply with the mies of propiska when

ever he/she changes his/her place of residence be it a move within the same

neighbourhood or another city. Usually the procedure takes a few days, if the new

residence place is not a 'closed' city such as Tashkent. It becomes problematic

when people start moving to more 'attractive' places like Tashkent. As I men

tioned above the primary stream of internal migrants move to Tashkent as a result

of the old system of single-city centralisation - and the policy of closed cities

poses tremendous problems for the majority of migrants.

To apply for a city propiska in Tashkent an applicant must go to a special

department which is part of the unit which usually deals with foreigners, while

applicants who already have Tashkent registrationbut wish to move within the

city go to a normal registration office in the district where he/she wants to relo

can there are two of registration or propiska - the

cate. So one say types

restricted/closed type for places/cities that are 'closed' and the open type for

that are not closed. Once an applicant is granted the long awaited

places/cities

permanent propiska he/she will not have any problems with registrationwithin

the city and will be granted all the advantages of being a 'full' citizen such as

access to employment and other services. It is con

rights to buy and sell property,

sidered to be a very great accomplishment if one obtains a permanent propiska in

Tashkent.

The whole of applying for propiska is a long one. An applicant must

process

numerous types of harassment from different officials in different

undergo

instances and deal with the disappointment of being sent from one place to

another for a small of paper that certifies something that may even be irrel

piece

evant to the application. In addition to all the trouble they must go to an applicant

has to be ready to pay the expenses for transport and other administrative costs

and time is lost waiting in long queues or rescheduling appointments that are

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

312 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

continuously cancelled. The frustration and disappointment as a result of an

applicant going through this sort of contact with the 'state', as represented by the

bureaucracy, makes many lose any hopes they may have had to appeal to the state

for support. The sense of being a 'citizen' is replaced with feelings of becoming

an 'internal other'.13 Even if a migrant is able to comply with all the local proce

dures and meets all the requirements to receive a propiska, the waiting period is

between six months and two years, although he/she has already spent time on the

long application process described above.

Migrants must pass innumerable internal checkpoints on their way from their

home town or village to Tashkent, and these resemble international border check

points. The migrants also have to deal with a state culture that sees internal

migration as inherentlysuspicious, just as it perceives international migration as

such. This can be seen in the mass deportations of illegal residents from Tashkent

to their home regions approximately one week before national holidays, particu

larly such as Independence Day on the first of September. A week before

such holidays the checkpoints around Tashkent limit passage to travellers that

have a permanentpropiska stamp in their passports that verifytheir residency in

the capital.

The deportation process is usually implemented in the following way. In a

period starting around three months before a national holiday the police carefully

register the residents of each household, including 'formal' (registered) and

'physical' or informal inhabitants by asking neighbours and working in close

cooperation with the mahalla14 committee. In fact, each mahalla committee

building has an 'uchastkoviy militia', meaning the police offices are located

within the building. After the lists have been completed and compared with the

previous lists, the police implement the deportation process on theirassigned ter

ritories, which they call the 'chistka' (from Russian 'cleaning') of people in the

mahalla who only have a short-term propiska or with no documentation at all.

People are 'kindly' asked to leave the city within the three days; if they do not do

so, they are taken to the Ippodromli where buses go from Tashkent to the outlying

regions of the country. This practice of asking people who have short-term

propiska to leave their flats until the end of holiday celebrations is implemented

with extreme rigorousness in the central part of Tashkent. This surveillance by

state officials and the demand for constant compliance with registration require

ments leads internal migrants to live their lives in an almost perpetual state of

'immigration'. They must constantly be able to prove that they have permission

to live where they do, otherwise they face state sanctions. The journey from a

rural to Tashkent can take a long time - not in the sense of distance,

region just

but in legal and emotional terms. Migrants are directly affected by all these rules

and laws, but they are excluded from the processes of making law and at

policy

the national level.

While the state as a law giver is out of reach, people must face the police on a

day-to-day basis and find ways to come to terms with officials who enforce these

laws.

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

313 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

CITIZENSHIP AND NATIONALISM IN UZBEKISTAN

Citizenship is a necessary element of 'civil society' according to Western models

of a state based on democratic principles. But these models failed to be imported

'fully' into the new post-Soviet states (Hann 1996; Kandiyoti 2002). After

gaining independence, Uzbekistan adopted its current Constitution in 1992

which theoretically grants equal rightsto all the citizens of Uzbekistan, including

non-Uzbeks. But the citizenship types that have been considered in academic

research do not fullyfitthe understanding of citizenship in Uzbekistan.

Following the generally accepted views on citizenship as a necessary devel

opment of modernity, which implies some heterogeneity by its inclusive

character, one would assume the equality of legal status of all citizens in

Uzbekistan, including non-Uzbeks, as defined in the Constitution. What has been

called Uzbek National Ideology ( Uzbek Milliy Goyasi) in the national state lan

guage16 has been promoted as national state policy, discriminating against

non-Uzbeks and making 'Uzbekness' an important value for the most 'attractive'

This policy is formally implemented by means of promotion of Uzbek

identity.17

symbolic capital and national language policies, and by grantingUzbeks priority

to high-rankingpositions within the state system and so on. Uzbek Milliy Goyasi

is a political ideology adapted from the principles of Sovietisation. This puts

ideals of citizenship, promoted on the state political discourse, under the question

and its democratic principles based on the equality of all the citizens. Thus, one

may assume that citizenship in Uzbekistan has a nationalist character and theo

retically, therefore,all Uzbeks should at least enjoy basic rights of citizenship.

But it is not that simple, since in fact practices of citizenship have a more com

plex character.

I argue thatcitizenship and citizenship rightsare limited to the locale of 'per

manent legal residence'. 'Legally' one only enjoys 'basic' citizenship rights in

the place where one has a permanentpropiska. The state of illegality of 'citizens'

starts at the point when they leave 'their place of permanent residence' to go to

another region, but this is often not clear to them initially; they slowly come to

realise the limits on their rightsas a 'citizen' often aftertheir firstcontact with a

police officerin the city.

The notion of citizenship is challenged by an existing system of dual legisla

tion I mentioned above thatrestrictsand limits social, legal and political rightsof

citizens of Uzbekistan. Thus I use the word 'citizen' in quotation marks to

emphasise the malfunction and illegitimacy of this legal status.

During conversations with migrants about their lives in Tashkent, many of

them made statements like 'I don't understand these laws that do not allow

Uzbeks to live and work wherever they want to within Uzbekistan' or '[what is

this] if one can't move within Uzbekistan and be Uzbek'18 which I encountered in

many differentvariations and which challenged the legitimacy of the law in

Uzbekistan. This perception of being illegal in one's own country leads actors to

finding an alternative refuge within other structures of belonging. One way to

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

314 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

find these 'structures' or spaces of refuge is within kinship and regional net

works. When talking about the solidarity of the migrant group and their mutual

assistance, many proudly stated that 'they are known for their having one mouth'

(from the Uzbek saying 'ogzibirchilik' which means 'to be united or have soli

darity'). In similar conversations about the migrants' life in Tashkent the notion

of musofir (musafir) was introduced with reference to migrants in Tashkent,

which in earlier times referredto a traveller who is far away from his home. It is

often introduced in statements like 'we are all musofirs collecting our rizq (suste

nance19) here (in Tashkent)'. Calling themselves musofir is an explicit reference

to the perception of leaving home for a foreign country. If the notion of citizen

ship in terms of 'belonging' to the state does not exist, the question then, is how

can itbe defined, and whether belonging to a family or kinship network (and only

formally being a citizen) is sufficientreplacement for advantages of citizenship.

The migrant group members, like any other internal migrant group in

Tashkent who do not have a legal rightto reside in the city,are officially 'citizens'

of the state but do not practise 'the ways of belonging' to the state listed in Glick

Schiller's (1999, 2004) definition. According to that analytical distinction

between 'ways of being' and 'ways of belonging' the former is more of a passive

state of existence whereas the latter is a more active participation and engage

ment in the collectivity one belongs to. One can be an Uzbek citizen but not

necessarily identify with this identity and not be willing to participate in the

processes of social and political life expected of a citizen, such as getting

employed within the state agencies, participating in political life of the state or

performing other duties expected by the state. Instead one actively belongs to a

network or collectivity with which one identifies oneself and actively participates

both in social and political life inside. In the following case study of a workers'

team it is implied that the notion of the 'cruel outside' does not encourage efforts

to go outside the networks that provide a safe environment and trust. The latter is

of crucial importance particularly in the cases of 'illegal' existence and was

stressed often in the contexts of discussing relationships and networks.

Below I cite the experiences of migrants without propiska in Tashkent

focusing on the process of 'becoming illegal,' which means the gradual loss of

citizenship rights and the strengthening of regional or kinship networks when

leaving the locale of permanent residency.

DIFFICULTIES IN BEING ILLEGAL RESIDENTS AND LEGAL

CITIZENS

In this section I present a typical situation that internal migrants face after coming

to Tashkent. It demonstrates the process in which a person realises the significant

reduction of expectations of a citizen in Uzbekistan. It will also touch upon the

processes of everyday face-to-face interaction of ordinary people with govern

ment institutions through the police. I studied three teams of workers in my

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

315 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

fieldwork. Two of them were organised under the auspices of family and business

networks, and the other one was led by a foreman who himself had a contract

with a customer. The foreman assembled his team by going back to his home vil

lage. The case I present here involves a team organised by this foreman, who was

responsible for everything from the organisation of the work to its administra

tion. One day Husan,20 the foreman, told me about the trouble he and his group

had while walking in the streetthe day before:

I was walking with four of my men in Yunusabad [one of the quarters of Tashkent]

and two policemen approached us in the street, of course requesting our passports.

I had a short-term propiska that did not expire yet but the boys had no propiska for

Tashkent in their passports. I asked why they [policemen] only asked us for our

passports, and they [the policemen] answered that we looked 'suspicious'21 so

they had to stop us and check our documents. The policemen took all of our pass

ports and asked us to follow them to the police station. I refused and proposed that

the policemen check our bags and passports right there on the street without taking

us to the police station. I said to the policemen that the four men were my friends

and had only arrived today. I asked the policemen to only take my passport and

return the others as I was the one who lives in Tashkent and I told them

[policemen] that my friends were visiting me and had no intention of staying in

Tashkent longer than three days.22 The policemen didn't even bother to listen to

what I was saying and the boys felt lost and scared because it was their first day in

Tashkent and - imagine - they had never been outside of their village before.

Finally I had to tell them the truth. I said that we were not doing anything

wrong in the city but came to work and earn money to feed our families at home.

But the police replied by saying that if we work hard, using our tools to earn,

money, then they also worked hard, using their pens to earn their living. We had to

follow them to the police station as they started to use force. At the police station

the boys were forced to write a statement (obyasnitelnaya) which was dictated by

the policemen and it said: 'we, (full name), confirm that we were approached by

policemen. After they showed us their IDs23 they asked for our passports but we

lied by saying that we didn't have them with us. We apologised for that. We were

hired by (my full name) based on an oral agreement in which he was supposed to

take us out of the country to work in Kazakhstan'.

Husan and his team were on their way to Kazakhstan where they had an agree

ment to do some work in a private house. Husan said that those statements signed

by four scared and lost men would mean several years of imprisonment24 for him.

AfterI asked whether policemen had the rightto detain people without proof

and officially approved orders, Husan answered that they did and that it was

writtenin the regulations {codex) that they could detain anybody 'suspicious' to

them (policemen) for from three hours to three days. I responded that if a person

knows his rights then the police cannot do anything to them, even in Uzbekistan.

He replied that now 'the power is in their [the police's] hands (hukumaf5 hozir

ularning kolinda), they can do whatever they want and the only thingthey want is

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

316 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

money'. I asked him what would happen if a person had no money. He answered

that he would have to find money if he did not want to have problems all the time.

I asked if he (Husan) had left the police station by saying 'go ahead and file

charges in the court'. He said that that would not have worked; if the case were

passed on to the court then it would be very difficult to get out of there and 'in a

regional police station (ROVD) they beat you up in any case'. I tried to suggest

ways that he could have rid himself of the police, but he came up with answers

such as 'that doesn't work, they don't care and they aim to get money and they do

everything to get it'. The story ended with Husan paying the equivalent of 45

USD as a bribe which the policemen said was a fine forbreaking the law. I asked

if they were given receipts but they were not. In this context Husan used the word

ôldja (booty/prey) and asked 'Didn't you know thatthey go out to hunt?'

This metaphor of the police as hunterand ordinary people as prey is not ironic

or amusing. Husan depicts a central aspect of the relationship between migrants

in Tashkent and the authorities. Encounters can sometimes be even more dra

matic. The state institutions abuse their power on a regular basis. Husan said that

he and his team were used to this kind of behaviour; once they had even been

arrested in their own flat just before sitting down to have their evening meal. The

police usually accused them of living withoutpropiska. If they had propiska, then

they were accused of bringing girls and organising orgies or of being involved in

activities that are against the law. They would never release them until they paid

bribes. According to Husan, these conversations always start with a policeman

asking what he and his people do and why they were in Tashkent. Husan said that

the money used for the bribe after they were stopped in the street represented a

serious financial problem for him and his team. The money paid was the only

money they had left for buying necessary materials for their work. Husan

sounded very angry about it and indicated that he showed his anger to the police

at the end of the encounter saying that he told the police that what they did is

wrong since he and his team were poor men trying to make ends meet.

Most working teams are better organised, with official connections for organ

ising propiska and other legal requirements connected with registration and

employment. Their headmen have many contacts among the police but they also

have to pay bribes each month. Husan represents a lower level of organisation,

with a small working team and fewer contacts. Husan does not get very big deals.

The jobs he takes on are mostly small; if he is lucky he may find a job that is a

bigger deal that requires more work and more workers involved. Then he hires

more people and earns more money. In his small team there is usually one

foreman who is paid from 100 to 300 USD a month and two or three workers who

get around 40 to 70 USD depending on the workload. Accommodation, propiska

and food are provided by him. Husan earns an average of 700 USD per contract

which can be for up to several thousand USD in total, and is used for paying for

wages, accommodation and other expenses. His job is to organise eveiything and

to check the work, and if necessary to work himself.

The case illustrates the difficulties that 'Uzbek citizens' can encounter while

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

317 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

moving within their own country. In the following section I will describe

propiska regulations and their meanings for ordinary people, which lie at the

heart of the above outlined negative encounter of internal migrants with the

Uzbek state.

MIGRANT NETWORKS IN TASHKENT

As I described above, if the propiska is difficultand often impossible to obtain,

migrants in Tashkent are illegal and thereforedeprived of the basic rightsas citi

zens to be employed and enjoy medical and schooling benefits. There is another

option formigrantswho are to seek help within theirkinship or regional networks

that they come to know beforehand in their home town or a village. The contacts

are established through existing acquaintances before travelling. Networks of

support are crucial when arriving and becoming established in Tashkent as the

state support is absent for people in these circumstances. Mostly the networks are

constitutedon the basis of regional or kinship belonging. These networks support

their members and even propiska is sometimes obtained via 'brothers' within the

networks, so that not everybody has to get involved with police. Among the

informants interviewed for the study there was not a single case where a migrant

had not used his or her networks, particularly in the case of obtaining a propiska.

Another pattern that I discovered during my fieldwork was that a migrant would

always arrange his accommodation through relatives, friends and acquaintances

before he leaves home for Tashkent.

In an interview with workers in one of the teams, another foreman, that I shall

call Hudayor, entered with a set of passports and gave them to the members of his

team. I asked about this and Hudayor said that he had gone to obtain propiska for

the whole team.

Families are at the centre of these networks. One of the reasons for this is the

fact that family ties are the firstprioritywhen maintaining contacts. The second

choice for establishing contact is some other kinship tie, followed by neighbour

hood, village and finally regional ties. Migrants tend not to leave their networks

when looking for help or socialising. Network privileges give incentives for

staying within the group and even for marrying within these networks, that have

in effectcreated isolated spaces with their own internal rules and hierarchies in

which members are able to feel very comfortable.

Many of my informants stated that 'ozlarimiznikilar yahshi chujoylarga

ishonch yok' (Our people are better, the outsiders cannot be trusted) when rea

soning their unwillingness to have anything in common with the non-members of

their networks. One can say that such a network provides a kind of security

the 'cruel' world outside which requires a great deal more by way of

against

resources to survive in, and that some members cannot simply afford. In other

words migrants actively belong to these types of networks and avoid any contact

with the state. Ethnic and regional identities are constructed and reinforced in this

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

318 GULIATIR HOJ AQIZI

context, and these challenge overarching concepts of Uzbek national identity as

well as the sense of belonging to a common group called citizens. It would not be

true to say that belonging to these networks is rationally preferred to attachment

to the overarching national identity, simply because the former provides and the

latter fails to do so. In addition to the survival strategies described there are emo

tional attachments of group solidarity and kinship ties involved when making

decisions as to who to identifywith. One can only add thatthe political and social

conditions in which citizens find themselves lead them to challenge the idea of a

citizen and a nationality as primary structures of belonging.

CONCLUSIONS

This paper provides an example of the examination of citizenship 'from below',

based on the 'citizen's' everyday life experiences vis-à-vis the Uzbek state. I have

shown thatUzbek citizens do not necessarily enjoy the citizenship rightsoutlined

in the constitution. Post-Soviet Uzbek politics have given rise to a paradoxical

Uzbek nationalistic policy which fosters the fragmentation of the Uzbek nation

rather than promoting the desired unification. The differences between regional

and ethnic groups subsumed under the term 'Uzbek' become particularly obvious

in Tashkent. On the level of identity politics, local policies and the retreat of

migrants into ethnic enclaves have resulted in the reassertion and strengthening

of ethnic/regional identities that were once unified under an overarching Uzbek

identity.Examining the notion of citizenship frombelow sheds light on the 'prac

tices' of citizenship taking place at the level of ordinary people's everyday

encounters.

My theoretical arguments support the approach that Kabeer et al. (2005) took

in analysing citizenship from below focusing on citizens' experiences and prac

tices of citizenship as defined by Turner (1993). Moreover I argued that

citizenship should not be studied in isolation from its local context which sup

ports views stated by Desforges (2005) who suggested studying the geographies

and spaces of citizenship.

I hope that the situation described in this paper and the issues I have touched

upon may prompt further discussions and debate on the new dimensions of

power relations and internal politics, network formation and identity politics that

are closely connected with the notion and perception of citizenship; and may con

tribute to ongoing theoretical debates on the in

understanding citizenship

complex non-Western societies.

Acknowledgements

My gratitude and acknowledgements go to the institutions that have supported

my scientific work and supervision. I would like to thank anonymous reviewers

whose comments were constructive and helpful for final reworking of this paper.

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

319 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

Many of my colleagues have contributed while discussing the initial versions of

this paper but my special thanks go to Robert Freedman who has contributed not

only with proof reading the text but also with his valuable comments on the con

tent of the paper. I am also grateful to my informants and those who assisted me

in the field.

NOTES

1 The

adjective 'ethnic' is used in this paper for a group which is culturally and tradition

ally different from other groups within an overarching Uzbek nation. The difference is not

analytically defined but rather stressed by the group itself. 'Ethnic' in this context can also

be synonymous with regional group as these groups come from different regions; how

ever, a clear-cut distinction is not possible in this context, while in certain cases several

regional groups can represent one ethnic or culturally and historically distinct group.

2

See Edward Schatz (2000) for study of similar issues in Kazakhstan.

3 See Louise

Shelly (1990) for more detailed study on the state control system of soviet

militia during the Soviet Union.

4

This term refers to the old Soviet policy of registration of residents and the control of

mobility. After Uzbekistan gained its independence these policies remained in place and

even gained in rigidity through amendments and new regulations. Propiska will be dis

cussed in detail later in the paper.

s For a detailed of the origin and development of Russian and Soviet

retrospective account

passport regimes seeMervyn 1993.

6 This

phrasing is from the brochure of internal regulations.

7 See Johan

Rasanayagam (2003) for more theoretical insights on the informal markets in

Uzbekistan. He discusses in detail the concept of 'duality' shedding light on formal and

informal sectors of economy in Uzbekistan.

8 There are several some of

groups that are coming from different regions of Uzbekistan,

the groups are culturally more different than others and some assimilate to the local popu

lation and some have mainly endogamous life trying not to intermany with other groups.

The group that I have studied is more culturally distinct than other groups and endoga

mous. For the sake of anonymity 1 will not name the group I studied and further in the

paper 1 will use simply general term 'migrants'.

9 is a name of the place.

Qamishkapa

10

Hoja is a name of the noble tribe or clan and in this context it might have been used as

-

nobility as opposed to faqir poor/ordinary people by the author of the dictionary where

the example is taken from.

11This and similar statements were made in interviews about difficulties and incentives for

leaving home town or village.

12 For a detailed and internal passport in other Soviet countries

study ofpropiska policies

see Cynthia Buckley ( 1995).

131 would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers who has prompted this phrasing.

14A mahalla is a traditional of two to three thousand people. Each mahalla

neighbourhood

has its mahalla committee.

15 track where the biggest bazaar for clothes) in

Ippodrom is a former race (mainly

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

320 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

Tashkent is located and where private buses, small vans and taxis gather to take up

passengers.

16This is used as uzbekchilikpolicy in Western scholarly work on Uzbekistan which

policy

is misleading and a mistaken term. Uzbekchilik can be translated as uzbekness and can

also be found in the state discourse in the meaning of uzbekness but it is not the name of

national state ideology that scholars wanted to describe. The national ideology of

Uzbekistan that is meant by the term uzbekchilik is Uzbek Milliiy Goyasi from Uzbek

means Uzbek National Ideology.

17 and Finke &

See Finke (2006) Sancak (2002) for a detailed and insightful study of

'Uzbek national identity'.

18

'If' is used in the ironic sense and it is pronounced with a special tone meaning 'what is

'

thisif...

19

Rizq is from the Qoran and is often translated as sustenance or food, but people use this

word in the meaning of any form of earnings, material things or even abstractions like hap

piness, joy, etc.

20

The personal names that appear in the paper are changed to protect the anonymity of

those concerned.

21

The very 'famous' reason to stop people in the streets, metro stations or make check ups

even at private homes which is a person/s 'looked suspicious' to policemen. Police and

officials of other force structures have used and misused the recent developments against

Islamic terrorists and discourses around it as tools to detain and interrogate people.

22 to regulations, people have a right to stay in a place without being registered

According

for not more than three days, which is also the rule for foreigners, who are also given three

days to register upon arrival.

23 Police

usually ask for passports without introducing themselves first despite the fact that

this is prescribed by law. Usually people do not ask policemen to introduce themselves and

show their IDs, but even if they do so, the policemen take it as a threat and become angry

with them. However there is a possibility that the police might believe that the person

asking for his ID

either has contacts that could get him (the policeman) into trouble or

knows his rights and knows how to officially make a complaint about him (policeman). A

person could try it but if he has no luck there is a risk that in this case the police realizes

that neither of the above are true or will assume so then the policeman may become angry

and cause more trouble than they would have caused, had they not been asked for their

(policemen's) ID. The chances are like the game ofPrisoner's Dilemma

24

There is a law against trafficking people, which can result in several years of imprison

ment.

25 Hukumat means

government in Uzbek but is used in the meaning of power an analogy to

the people's understanding of power as the power of the state. It is understood that the

power is in the state while the people remain powerless.

REFERENCES

Akbarov, S.F. 1988. Üzbekca-rusca lugat: 50000ga jakin sûz va ibora [Uzbek-Russian

dictionary]. Üzbekiston SSR Fanlar Akademijasi A. S. ... Puskin Nomidagi Til va

Adabiët Instituti. S. F. Akbarov ... taljriri ostida, Toskent: Üzbek Sovet

Ènciklopedijasi Bos Red.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1994. Nationhood and the National Question in the Soviet Union and

Post-Soviet Eurasia: An Institutionalist Account, Theory and Society 23, 1: 47-78.

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

321 CITIZENSHIP AND ETHNICITY

Buckley, Cynthia. 1995. The Myth of Managed Migration: Migration Control and

Market in the Soviet Period Slavic Review 54,4: 896-916.

Desforges Luke et al. 2005. New Geographies of Citizenship Citizenship Studies 9, 5:

439-51.

Finke, Peter & Sanjak, Meltem. 2002-2003. Variations in Social Identity and Ethnic dif

ferentiation, in Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Report 2002-2003:

113-21. Halle/Saale: Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology.

Finke, Peter. 2006. Variations on Uzbek Identity: Concepts, Constraints and Local

Configurations. Professorial dissertation, Institute for Ethnology, University of

Leipzig.

Gleason, Gregory. 1991. Fealty and Loyalty: Informal Authority Structures in Soviet

Asia Soviet Studies 43,4: 613-28.

Glick Schiller, Nina. 1999. Transmigrants and Nation-States: Something Old and

Something New in US Immigrant Experience, in Charles Hirschman, Josh DeWind

and Philip Kasinitz (eds) Handbook of International Migration: The American

Experience: 94-119. New York (NY): Russell Sage.

Glick Schiller, Nina & Levitt, Peggy. 2004. Conceptualizing Simultaneity: A

Transnational Social Field Perspective on Society International Migration Review

38(3) : 1002—1039.

Hall, T. & Williamson, H. 1999. Citizenship and Community. Leicester: Youth Work

Press.

Hann, Chris. 1996. Introduction Political society and civil anthropology, in Chris Hann

& Elizabeth Dunn (eds), Civil Society: Challenging Western Models. London and

New York (NY): Routledge.

1998. Foreword, in Susan Bridger & Frances Pine (eds) Surviving post-socialism:

local strategies and regional responses in eastern Europe and the former Soviet

Union. London: Routledge. Routledge studies of Aocieties in Transition.

2002 Farewell to Socialist 'other', in Chris Hann (ed.) Postsocialism: Ideals,

Ideologies and Practices in Eurasia. London: Routledge

Hojdestrand, Tova. 2003. The Soviet-Russian production of homelessness. Propiska,

housing, privatisation, Web document: http://www.anthrobase.eom/Txt/H/

Hoejdestrand_T_01 .htm

Humphrey, Caroline. 2002. Does the category 'postsocialist' still make sense? in Chris

Hann (ed.) Postsocialism: Ideals, Ideologies and Practices in Eurasia: 12-15.

London & New York (NY): Routledge.

Il'khamov, Alisher. 2001. Impoverishment of the masses in the transition period: signs

of an emerging 'new poor' identity in Uzbekistan, Central Asia Survey 20(1):

33-54.

Kabeer, Naila. 2005. The search for inclusive citizenship: Meanings and expressions in

an interconnected world, in Naila Kabeer (ed.), Inclusive Citizenship: Meanings

and Expression : 1-30. London: Zed Books.

2002 Citizenship, Affiliation and Exclusion: Perspectives from the South, Institute of

Development Studies Bulletin 33(2): 12-23(12.)

Kandiyoti, Deniz. 2002. How far does the analysis of postsocialism travel? The case of

Central Asia, in Chris Hann (ed.), Postsocialism: Ideas, Ideologies and Practices in

Eurasia: 238-257. London: Routledge.

Marshall, Thomas Humphrey. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

322 GULIATIR HOJAQIZI

Mervyn, Matthews. 1993. The passport Society: Controlling Movement in Russia and

the USSR. San Francisco (CA) and Oxford: Westview Press.

Rasanayagam, Johan. 2003. Market, State and Community in Uzbekistan: Reworking

the Concept of the Informal Economy. Halle/Saale: Max Planck Institute for Social

Anthropology. Working paper no.59.

Schatz, Edward. 2000. The Politics of Multiple Identities: Lineage and Ethnicity in

Kazakhstan, Europe-Asia Studies 52(3): 489-506.

Shelly, Louise L. 1990. Policing Soviet Society: The Evolution of State Control, Law &

Social Inquiry 15(3): 479-520.

Stewart, Angus. 1995. Two Conceptions of Citizenship, The British Journal of

Sociology 46(1): 63-78.

Suny, Ronald Grigor. 1999. Provisional Stabilities: The Politics of Identities in Post

Soviet Eurasia, International Security 24(3): 139-78.

Tishkov, Valéry A. 1997. The Culture of Ethnic Violence: the Osh Conflict, in Valéry A.

Tishkov (ed.) Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict in and after the Soviet Union: The

Mind Aflame: 135-54. London: Sage Publications.

Turner, Bryan S. 1990. Outline of Theory of Citizenship, Sociology 24(2): 189-217.

1993. Contemporary Problems in The Theory of Citizenship, in Bryan S. Turner (ed.)

Citizenship and Social Theory. 1-18. London: Sage Publications.

This content downloaded from 195.37.16.155 on Thu, 29 Jan 2015 09:34:50 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Full Download Solution Manual For Predictive Analytics For Business Strategy 1st Edition Jeff Prince PDF Full ChapterDocument32 pagesFull Download Solution Manual For Predictive Analytics For Business Strategy 1st Edition Jeff Prince PDF Full Chaptercucumisinitial87qlh95% (21)

- Mou Job FairDocument4 pagesMou Job FairLoyola VijayawadaNo ratings yet

- Lac It Cert 832987 PDFDocument1 pageLac It Cert 832987 PDFManoj Kumar0% (1)

- Josip Broz TitoDocument39 pagesJosip Broz TitoGoran Maric100% (1)

- Hailemariam RedaDocument26 pagesHailemariam RedaWeldese100% (4)

- The Rosicrucian Sunshine Circle (1931-1967?)Document21 pagesThe Rosicrucian Sunshine Circle (1931-1967?)sauron385100% (7)

- The Iroquois ConstitutionDocument2 pagesThe Iroquois ConstitutionKevin16190% (2)

- Spetsnaz. The Inside Story of The Soviet Special ForcesDocument124 pagesSpetsnaz. The Inside Story of The Soviet Special ForcesV2100% (2)

- Post - Soviet Uncertainties: Micro - Orders of Central Asian Migrants in RussiaDocument20 pagesPost - Soviet Uncertainties: Micro - Orders of Central Asian Migrants in RussiaRano TuraevaNo ratings yet

- Tiejun Cheng and Mark Selden: The Origins and Social Consequences of China's Hukou SystemDocument25 pagesTiejun Cheng and Mark Selden: The Origins and Social Consequences of China's Hukou SystemAaditya JainNo ratings yet

- Chat Week 5Document51 pagesChat Week 5Raghaw KhattriNo ratings yet

- Building State Failure in Kosovo - Joseph Coelho (2015)Document10 pagesBuilding State Failure in Kosovo - Joseph Coelho (2015)annamdNo ratings yet

- Rasanayagam2014 PDFDocument15 pagesRasanayagam2014 PDFsomalilandNo ratings yet

- Rasanayagam2014 PDFDocument15 pagesRasanayagam2014 PDFsomalilandNo ratings yet

- 03 Wilkinson, Cai - Imagining Kyrgyzstan's Nationhood and Statehood - Reactions To The 2010 Osh ViolenceDocument21 pages03 Wilkinson, Cai - Imagining Kyrgyzstan's Nationhood and Statehood - Reactions To The 2010 Osh ViolencecetinjeNo ratings yet

- Why Is It Hard To Build A Strong Civil Society in Kazakhstan?Document22 pagesWhy Is It Hard To Build A Strong Civil Society in Kazakhstan?Central Asian StudiesNo ratings yet

- 185-Article Text-935-1-10-20220621Document14 pages185-Article Text-935-1-10-20220621Farrukh RahooNo ratings yet

- Trends in The Development of The Digital Economy in UzbekistanDocument3 pagesTrends in The Development of The Digital Economy in UzbekistanresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Imigrația Și Identitatea Cetățeniei Paradoxul UniversalismuluiDocument15 pagesImigrația Și Identitatea Cetățeniei Paradoxul UniversalismuluiCristian ChiruNo ratings yet

- 02 Isaacs, Rico - Nomads, Warriors and Bureaucrats - Nation-Building and Film in Post-Soviet KazakhstanDocument19 pages02 Isaacs, Rico - Nomads, Warriors and Bureaucrats - Nation-Building and Film in Post-Soviet KazakhstancetinjeNo ratings yet

- Corruption Networks in RussiaDocument16 pagesCorruption Networks in RussiaJason TaylorNo ratings yet

- Barriers and Challenges of Educational Development in China: An Analysis On Rural-Urban Migrant ResidentsDocument9 pagesBarriers and Challenges of Educational Development in China: An Analysis On Rural-Urban Migrant ResidentsRahayu SulistiyaniNo ratings yet

- State Civil Society Relationsin Zimbabwes Second RepublicDocument27 pagesState Civil Society Relationsin Zimbabwes Second RepublicLuyimbaazi DanielNo ratings yet

- 00 Isaacs, Rico Polese, Abel - Between "Imagined" and "Real" Nation-Building - Identities and Nationhood in Post-SovietDocument13 pages00 Isaacs, Rico Polese, Abel - Between "Imagined" and "Real" Nation-Building - Identities and Nationhood in Post-SovietcetinjeNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1862012Document5 pagesSSRN Id1862012jagadeeshsreeram2No ratings yet

- Davorin Trpeski - Cultural Policies and Cultural Heritage in Socialist Macedonia Establishment of The Macedonian State (2020)Document10 pagesDavorin Trpeski - Cultural Policies and Cultural Heritage in Socialist Macedonia Establishment of The Macedonian State (2020)Атанас ЧупоскиNo ratings yet

- Perceived Social Citizenship A Comparative Study Between Two Different HukousDocument18 pagesPerceived Social Citizenship A Comparative Study Between Two Different HukousKesi KNo ratings yet

- Botakoz Kasumbekova European Resttlement in TJK 2011Document18 pagesBotakoz Kasumbekova European Resttlement in TJK 2011amudaryoNo ratings yet

- Gellner 2Document4 pagesGellner 2Lalit SinghNo ratings yet

- From Russia With BlatDocument75 pagesFrom Russia With BlatThe Russia MonitorNo ratings yet

- Book CYEP 6 2 277 304Document28 pagesBook CYEP 6 2 277 304paravelloNo ratings yet

- Oak SDocument7 pagesOak SAbeeha KhanNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals - 274 - Articles - 36836 - Submission - Proof - 36836 3265 70811 1 10 20070823Document12 pagesAjol File Journals - 274 - Articles - 36836 - Submission - Proof - 36836 3265 70811 1 10 20070823shenterjerinaNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal Alisher PDFDocument14 pagesResearch Proposal Alisher PDFRaghu ShekarNo ratings yet

- From Strong State To A Strong Civil Society-Domestic Discourse of Civil Society in Post-Soviet UzbekistanDocument10 pagesFrom Strong State To A Strong Civil Society-Domestic Discourse of Civil Society in Post-Soviet UzbekistanAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Articol KakanienDocument9 pagesArticol KakanienSimona RodatNo ratings yet

- 09 Eua655653Document10 pages09 Eua6556539883786897No ratings yet

- Rebranding A Kleptocratic State Reputation Laundering in Uzbekistan Lasslett MatyakubovaDocument9 pagesRebranding A Kleptocratic State Reputation Laundering in Uzbekistan Lasslett MatyakubovaMira MatyakubovaNo ratings yet

- Russian Revolution and The Bolshevik Dictatorship: Journal of Russian & East European PsychologyDocument58 pagesRussian Revolution and The Bolshevik Dictatorship: Journal of Russian & East European PsychologyNtina KvnstaNo ratings yet

- Communist and Post-Communist Studies 2012 LaruelleDocument11 pagesCommunist and Post-Communist Studies 2012 LaruelleCara Kerven100% (1)

- Cultural and Social FactorsDocument19 pagesCultural and Social FactorsJulia MendezNo ratings yet

- Sreten VujovićDocument19 pagesSreten VujovićZoran RadmanNo ratings yet

- Unit - III Urban Sociology, Economics, GeographyDocument37 pagesUnit - III Urban Sociology, Economics, GeographyDivya Purushothaman100% (2)

- 1182-Article Text-8280-1-10-20230707Document12 pages1182-Article Text-8280-1-10-20230707Abdul Akeem Ibrahim MrGovernorNo ratings yet

- Lūse, Agita. 2009. I Am An Important and Needed Person.' A Study of A Support Group Movement in Post-Soviet LatviaDocument21 pagesLūse, Agita. 2009. I Am An Important and Needed Person.' A Study of A Support Group Movement in Post-Soviet LatviaAgitaNo ratings yet

- 14 Indonesian Culture HeritagesDocument10 pages14 Indonesian Culture Heritagesjauza.sllh23No ratings yet

- A Comparison and Contrast Between Chin and TanzaniaDocument21 pagesA Comparison and Contrast Between Chin and Tanzaniamrpboss1No ratings yet

- Applying Theoretical PerspectivesDocument5 pagesApplying Theoretical PerspectivesN ShahidNo ratings yet

- Adivasi Journal Vol-44Document104 pagesAdivasi Journal Vol-44hndashNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of "Civil Society" in Bolivia Shakow 2019Document15 pagesThe Rise and Fall of "Civil Society" in Bolivia Shakow 2019carolinecottademelloNo ratings yet

- Kim STATECIVILSOCIETY 2001Document21 pagesKim STATECIVILSOCIETY 2001Kiều Chinh TrầnNo ratings yet

- Caste and The Indian Economy: Kaivan MunshiDocument55 pagesCaste and The Indian Economy: Kaivan MunshiIsak PeuNo ratings yet

- Gender, Body and Intersectionality - Lola Merli PDFDocument13 pagesGender, Body and Intersectionality - Lola Merli PDFLola MerliNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.112 On Tue, 06 Jul 2021 16: Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.112 On Tue, 06 Jul 2021 16: Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTCAltafNo ratings yet

- China's Hukou System: Disparity Between Urban and Rural Residents Under The Chinese SystemDocument10 pagesChina's Hukou System: Disparity Between Urban and Rural Residents Under The Chinese SystemQuim EmbongNo ratings yet

- Ritual in UzbakistanDocument24 pagesRitual in UzbakistanElham RafighiNo ratings yet

- Of Private and Social in Socialist Cities: The Individualizing Turn in Housing in A Medium-Sized City in Socialist YugoslaviaDocument18 pagesOf Private and Social in Socialist Cities: The Individualizing Turn in Housing in A Medium-Sized City in Socialist YugoslaviaMatt BanksNo ratings yet

- Tajikistan: Civil Society: An OverviewDocument12 pagesTajikistan: Civil Society: An Overviewvivek tripathyNo ratings yet

- Samoupravljanje - Raspad YugeDocument13 pagesSamoupravljanje - Raspad YugenikidorsNo ratings yet

- 2009 ResourcingCultureDocument18 pages2009 ResourcingCultureAdrian RNo ratings yet

- The Modern Impact of Precolonial Centralization in AfricaDocument68 pagesThe Modern Impact of Precolonial Centralization in AfricaLearning Space TutorsNo ratings yet

- ch-010Document15 pagesch-010Ly LinyNo ratings yet

- Admir Cavalic The Curious Case of Decentralization in Bosnia and HerzegovinaDocument19 pagesAdmir Cavalic The Curious Case of Decentralization in Bosnia and HerzegovinaAdmir ČavalićNo ratings yet

- Reviewed - IJLL - Formt-Discipline and Subjection in The Social Construction of Leftover WomenDocument14 pagesReviewed - IJLL - Formt-Discipline and Subjection in The Social Construction of Leftover Womeniaset123No ratings yet

- Aleaz MadrasaEducationState 2005Document11 pagesAleaz MadrasaEducationState 2005Agniswar GhoshNo ratings yet

- Governing Neighborhoods in Urban China: Changing State-Society RelationsFrom EverandGoverning Neighborhoods in Urban China: Changing State-Society RelationsNo ratings yet

- The Right To Inhabit in The City: Yeni Sahra Squatter Settlement in IstanbulDocument18 pagesThe Right To Inhabit in The City: Yeni Sahra Squatter Settlement in IstanbulaharysaktiNo ratings yet

- Nationalism and Communism As Foes and Friends Comparing The Bolshevik and Chinese RevolutionariesDocument38 pagesNationalism and Communism As Foes and Friends Comparing The Bolshevik and Chinese Revolutionarieszt2003819abcNo ratings yet

- Written Submission by ADASA On 11.10.201.Document6 pagesWritten Submission by ADASA On 11.10.201.vadrevusriNo ratings yet

- Proposal Penelitian Yulius MadaDocument38 pagesProposal Penelitian Yulius MadaYulius MadakakaNo ratings yet

- 406 Parliamentary Procedure Lesson PlanDocument9 pages406 Parliamentary Procedure Lesson PlanJasmin AbasNo ratings yet

- CTPAT Info - BDocument4 pagesCTPAT Info - BmanikNo ratings yet

- RODOLFO G NAVARRO Et Al Versus EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITA G R No 180050 February 10 2010Document1 pageRODOLFO G NAVARRO Et Al Versus EXECUTIVE SECRETARY EDUARDO ERMITA G R No 180050 February 10 2010D'Judds ManggadNo ratings yet

- Field Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer KGDocument26 pagesField Marshal Sir Gerald Walter Robert Templer KGNur Izzati Farehah Yen100% (1)

- Unnatural Offences: A Comparitive Analysis With Special Reference To Uk and UsaDocument14 pagesUnnatural Offences: A Comparitive Analysis With Special Reference To Uk and UsaAnimesh Deep100% (1)

- Cawaling v. COMELECDocument3 pagesCawaling v. COMELECMaria Analyn100% (1)

- Brian - Thomas@ky - Gov Sam - Flynn@ky - GovDocument2 pagesBrian - Thomas@ky - Gov Sam - Flynn@ky - GovWKYTNo ratings yet

- 1944 21Document300 pages1944 21nofail eastNo ratings yet

- Geo State ReorganisationDocument5 pagesGeo State Reorganisationsaarika_saini1017No ratings yet

- Cayo NortheastDocument122 pagesCayo NortheastGarifuna NationNo ratings yet

- Ad For DVDocument18 pagesAd For DVDipayan MondalNo ratings yet

- Legal Studies Holiday Homework Grade Xii 2021-22Document3 pagesLegal Studies Holiday Homework Grade Xii 2021-22lolswxNo ratings yet

- SALES.09.Melliza Vs City of IloiloDocument2 pagesSALES.09.Melliza Vs City of IloiloPaolo Ervin PerezNo ratings yet

- Chap3 - Legal Analysis and WritingDocument28 pagesChap3 - Legal Analysis and WritingAldreje TuazonNo ratings yet

- Lea Final CoachingDocument286 pagesLea Final CoachingAlbert BermudezNo ratings yet

- Hko Ah Pao vs. Ting. GR No. 153476, September 27, 2006Document1 pageHko Ah Pao vs. Ting. GR No. 153476, September 27, 2006Erika Angela GalceranNo ratings yet

- Sukh Chan Employee CostingDocument2 pagesSukh Chan Employee CostingAbdul MateenNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of DemocracyDocument27 pagesDimensions of DemocracyBabita YadavNo ratings yet

- 4txZnSmGS7Sq ZcFgI9Wqw Module-7.Red-Power - Jan2023 REVISEDDocument30 pages4txZnSmGS7Sq ZcFgI9Wqw Module-7.Red-Power - Jan2023 REVISEDRay GillNo ratings yet

- Reyes Vs AlmanzorDocument1 pageReyes Vs AlmanzorBenedick LedesmaNo ratings yet