Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diébédo Francis Kéré - Pritzker

Uploaded by

Nancy Xu0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views4 pagesFrancis Kéré is named the 2022 Pritzker Prize Laureate for his work designing buildings in rural Africa that are tailored to local needs and materials. His projects, such as a primary school in Gando, Burkina Faso, use sustainable methods like double roofs, ventilation, and shade to create comfortable spaces. Kéré combines his architectural training in Berlin with traditional knowledge from his home country. He sees architecture as a way to elevate communities and empower people through accessible education. His work demonstrates how attention to place, culture and people's needs can create meaningful architecture globally.

Original Description:

Original Title

Diébédo Francis Kéré | Pritzker

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFrancis Kéré is named the 2022 Pritzker Prize Laureate for his work designing buildings in rural Africa that are tailored to local needs and materials. His projects, such as a primary school in Gando, Burkina Faso, use sustainable methods like double roofs, ventilation, and shade to create comfortable spaces. Kéré combines his architectural training in Berlin with traditional knowledge from his home country. He sees architecture as a way to elevate communities and empower people through accessible education. His work demonstrates how attention to place, culture and people's needs can create meaningful architecture globally.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views4 pagesDiébédo Francis Kéré - Pritzker

Uploaded by

Nancy XuFrancis Kéré is named the 2022 Pritzker Prize Laureate for his work designing buildings in rural Africa that are tailored to local needs and materials. His projects, such as a primary school in Gando, Burkina Faso, use sustainable methods like double roofs, ventilation, and shade to create comfortable spaces. Kéré combines his architectural training in Berlin with traditional knowledge from his home country. He sees architecture as a way to elevate communities and empower people through accessible education. His work demonstrates how attention to place, culture and people's needs can create meaningful architecture globally.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

!

What is the role of architecture in contexts

of extreme scarcity? What is the right

approach to the practice when working

against all odds? Should it be modest and

risk succumbing to adverse

circumstances? Or is modesty the only

way to be pertinent and achieve results?

Should it be ambitious in order to inspire

change? Or does ambition run the risk of

being out of place and of resulting in

architecture of mere wishful thinking?

Francis Kéré has found brilliant, inspiring

and game-changing ways to answer these

questions over the last decades. His

cultural sensitivity not only delivers social

and environmental justice, but guides his

entire process, in the awareness that it is

the path towards the legitimacy of a

building in a community. He knows, from

within, that architecture is not about the

object but the objective; not the product,

but the process.

Xylem, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Francis Kéré’s entire body of work shows

us the power of materiality rooted in place.

His buildings, for and with communities,

are directly of those communities – in their

making, their materials, their programs

and their unique characters. They are tied

to the ground on which they sit and to the

people who sit within them. They have

presence without pretense and an impact

shaped by grace.

Born in Burkina Faso to parents who

insisted that their son be educated,

Francis Kéré went on to the study of

architecture in Berlin. Over and over, he

has, in a sense returned to his roots. He

has drawn from his European architectural

formation and work, combining them with

the traditions, needs and customs of his

country. He was determined to bring

resources in education from one of the

leading Technical Universities in the world

back to his native land and to have those

resources elevate the indigenous know-

how, culture and society of his region.

LycÇe Schorge, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

He has continuously pursued this task in

ways at once highly respectful of place

and tradition and yet transformational in

what can be o!ered, as in the primary

school in Gando which served as an

example to so many even beyond the

borders of Burkina Faso, and to which he

later added a complex of teachers’

housing and a library. There, Kéré

understood that an apparently simple

goal, namely, to make it possible for

children to attend school comfortably, had

to be at the heart of his architectural

project. Sustainability for a great majority

of the world is not preventing undesirable

energy loss so much as undesirable

energy gains. For too many people in

developing countries, the problem is

extreme heat, rather than cold.

In response he developed an ad-hoc,

highly performative and expressive

architectural vocabulary: double roofs,

thermal mass, wind towers, indirect

lighting, cross ventilation and shade

chambers (instead of conventional

windows, doors and columns) have not

only become his core strategies, but have

actually acquired the status of built dignity.

Since completing the school in his native

village, Kéré has pursued the ethos and

the method of working with local craft and

skills to elevate not only the civic life of

small villages, but soon also of national

deliberations in legislative buildings. This

is the case of his two projects underway

for the Benin National Assembly, in

advanced construction, and for the

Burkina Faso National Assembly,

temporarily halted by the current political

situation in the country.

Léo Doctors’ Housing, photo courtesy of Jaime

Herraiz

Francis Kéré’s work is, by its essence and

its presence, fruit of its circumstances. In

a world where architects are building

projects in the most diverse contexts – not

without controversies – Kéré contributes

to the debate by incorporating local,

national, regional and global dimensions in

a very personal balance of grass roots

experience, academic quality, low tech,

high tech, and truly sophisticated

multiculturalism. In the Serpentine

pavilion, for example, he successfully

translated into a universal visual language

and in a particularly e!ective way, a long-

forgotten essential symbol of primordial

architecture worldwide: the tree.

He has developed a sensitive, bottom-up

approach in its embrace of community

participation. At the same time, he has no

problem incorporating the best possible

type of top-down process in his devotion

to advanced architectural solutions. His

simultaneously local and global

perspective goes well beyond aesthetics

and good intentions, allowing him to

integrate the traditional with the

contemporary.

Serpentine Pavilion, photo courtesy of Iwan Baan

Francis Kéré’s work also reminds us of the

necessary struggle to change

unsustainable patterns of production and

consumption, as we strive to provide

adequate buildings and infrastructure for

billions in need. He raises fundamental

questions of the meaning of permanence

and durability of construction in a context

of constant technological changes and of

use and re-use of structures. At the same

time his development of a contemporary

humanism merges a deep respect for

history, tradition, precision, written and

unwritten rules.

Since the world began to pay attention to

the remarkable work and life story of

Francis Kéré, he has served as a singular

beacon in architecture. He has shown us

how architecture today can re"ect and

serve needs, including the aesthetic

needs, of peoples throughout the world.

He has shown us how locality becomes a

universal possibility. In a world in crisis,

amidst changing values and generations,

he reminds us of what has been, and will

undoubtably continue to be a cornerstone

of architectural practice: a sense of

community and narrative quality, which he

himself is so able to recount with

compassion and pride. In this he provides

a narrative in which architecture can

become a source of continued and lasting

happiness and joy.

For the gifts he has created through his

work, gifts that go beyond the realm of the

architecture discipline, Francis Kéré is

named the 2022 Pritzker Prize Laureate.

Jury Members

Alejandro Aravena, Chair

Barry Bergdoll

Deborah Berke

Stephen Breyer

You might also like

- Rotating Double Rack Electric Oven ManualDocument44 pagesRotating Double Rack Electric Oven Manualyeneneh14No ratings yet

- Appendix 1 BICSc Cleaning Standards SpecificationsDocument5 pagesAppendix 1 BICSc Cleaning Standards SpecificationsKifah Zaidan75% (4)

- Cultural Centre ThesisDocument45 pagesCultural Centre ThesisEsther Akpan100% (3)

- Offer Letter To Land Owner 3 Katha I Block (11.07.2020) ...Document11 pagesOffer Letter To Land Owner 3 Katha I Block (11.07.2020) ...AB Rakib Ahmed100% (9)

- The Vernacular Architecture As A Model For Sustainable Design in Africa.Document36 pagesThe Vernacular Architecture As A Model For Sustainable Design in Africa.mabakks92% (13)

- Interpreting Kigali, Rwanda: Architectural Inquiries and Prospects for a Developing African CityFrom EverandInterpreting Kigali, Rwanda: Architectural Inquiries and Prospects for a Developing African CityNo ratings yet

- Design of SHEVSDocument19 pagesDesign of SHEVSsmcsamindaNo ratings yet

- Francis KereDocument2 pagesFrancis KereTanaya ChiplunkarNo ratings yet

- Kerstin Pinther 2016 Francis KereDocument8 pagesKerstin Pinther 2016 Francis KerehooyekNo ratings yet

- IJMSHR - Volume 2 - Issue 2 - Pages 48-53Document6 pagesIJMSHR - Volume 2 - Issue 2 - Pages 48-53Tasnim ElzeinNo ratings yet

- Ehrlich, Steven - Multicultural Modernism - Architectural Balance in A Changing World, 2009 PDFDocument7 pagesEhrlich, Steven - Multicultural Modernism - Architectural Balance in A Changing World, 2009 PDFIzel IsmailNo ratings yet

- Vernacular Ques 1Document1 pageVernacular Ques 1Aastha SainiNo ratings yet

- Multicultural Modernism - Architectural Balance in A Changing WorlDocument7 pagesMulticultural Modernism - Architectural Balance in A Changing WorlDannel PaningbatanNo ratings yet

- Cc2 Statement: Yusuf RahmanDocument4 pagesCc2 Statement: Yusuf RahmanMohammed RahmanNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Level of Responsiveness of Vernacular Architecture To The Needs of Citizens in Sari, IranDocument13 pagesInvestigating The Level of Responsiveness of Vernacular Architecture To The Needs of Citizens in Sari, IranHarshita BhanawatNo ratings yet

- Arianna Fornasiero + Paolo Turconi's Flexible Housing Plan Fits Ethiopian Social-FrameDocument12 pagesArianna Fornasiero + Paolo Turconi's Flexible Housing Plan Fits Ethiopian Social-FramegioanelaNo ratings yet

- 2519 6773 1 PBDocument7 pages2519 6773 1 PBKritika SalwanNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument21 pagesBackground of The StudyLain PadernillaNo ratings yet

- Philippine Vernacular ArchitectureDocument24 pagesPhilippine Vernacular ArchitectureArianne Joy Quiba DullasNo ratings yet

- The Interior Design of The Egyptian Residence Between Originality and ModernityDocument15 pagesThe Interior Design of The Egyptian Residence Between Originality and Modernity2ron ron2No ratings yet

- Literature Review Vernacular ArchitectureDocument8 pagesLiterature Review Vernacular Architectureafmzfxfaalkjcj100% (2)

- CWE Vol10 SPL (1) P 448-458Document11 pagesCWE Vol10 SPL (1) P 448-458M Hammad ManzoorNo ratings yet

- VASSA Journal 12 Dec 2004Document33 pagesVASSA Journal 12 Dec 2004hans_viljoenNo ratings yet

- Hassan FathyDocument29 pagesHassan Fathyrevathisasikumar5420No ratings yet

- The Radicant Architecture and Migration: Caroline Sohie and Cecilia ChiappiniDocument12 pagesThe Radicant Architecture and Migration: Caroline Sohie and Cecilia ChiappiniAlejandra Lamprea VélezNo ratings yet

- Architecture in Northern Ghana: A Study of Forms and FunctionsFrom EverandArchitecture in Northern Ghana: A Study of Forms and FunctionsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-2Document22 pagesChapter 1-2Lain PadernillaNo ratings yet

- 13 Proposition of Post Modern ArchitectureDocument1 page13 Proposition of Post Modern ArchitectureMin Costillas ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Design Research Process: Reviving Culture Through ArchitectureDocument17 pagesThesis Design Research Process: Reviving Culture Through ArchitectureRAFIA IMRANNo ratings yet

- CPAR M4 Week 4 Filipino Contemporary ArtistsDocument24 pagesCPAR M4 Week 4 Filipino Contemporary Artistsmanago.abuNo ratings yet

- Dissertation: SynopsisDocument10 pagesDissertation: Synopsisdeepshikha purohitNo ratings yet

- Uas BitDocument2 pagesUas BitFredrik M4t4No ratings yet

- A Lesson From Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria: Contemporary Urban AffairsDocument12 pagesA Lesson From Vernacular Architecture in Nigeria: Contemporary Urban AffairsnnubiaNo ratings yet

- A Simple Analysis On The Combination of Modernism and Regional Culture in The Construction by Geoffrey BawaDocument4 pagesA Simple Analysis On The Combination of Modernism and Regional Culture in The Construction by Geoffrey BawaPadma S. AbhimanueNo ratings yet

- ARTS02A - 02 Cultural MappingDocument8 pagesARTS02A - 02 Cultural MappingMJ TaclobNo ratings yet

- Representation and Context Based DesignDocument10 pagesRepresentation and Context Based DesignIpek DurukanNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 14 13564Document21 pagesSustainability 14 13564Naveen kishoreNo ratings yet

- Transformation (Baiga) in Vernacular Architecture of Baiga Tribes of Central India Page No 115Document276 pagesTransformation (Baiga) in Vernacular Architecture of Baiga Tribes of Central India Page No 115alankarNo ratings yet

- Cultural Continuum and Regional Identity in Architecture PDFDocument5 pagesCultural Continuum and Regional Identity in Architecture PDFValdriana CorreaNo ratings yet

- Considering Afrocentrism in Hausa Traditional ArchitectureDocument6 pagesConsidering Afrocentrism in Hausa Traditional ArchitectureInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- From The Ground UpDocument2 pagesFrom The Ground Upis03lcmNo ratings yet

- Jadenlimkaijie Fracturesinsegregation Essay RevisionDocument8 pagesJadenlimkaijie Fracturesinsegregation Essay Revisionapi-518329636No ratings yet

- Tradition in Transition Reflections On The Architecture of EthiopiaDocument11 pagesTradition in Transition Reflections On The Architecture of EthiopiaNatnael YeshiwasNo ratings yet

- Personal StatementDocument2 pagesPersonal StatementChirita in proviniteNo ratings yet

- Edwin Jurriens - The Countryside in Indonesian Contemporary Art and MediaDocument29 pagesEdwin Jurriens - The Countryside in Indonesian Contemporary Art and MediaRirin Septi AmbarwatiNo ratings yet

- Cultural Identity Research Paper ReviewDocument2 pagesCultural Identity Research Paper ReviewSagar RajyaguruNo ratings yet

- Summary Paper For Week 2&3 (Prof - Prac 3)Document5 pagesSummary Paper For Week 2&3 (Prof - Prac 3)rymndNo ratings yet

- Why Is It Important To The Filipino Architects To Understand Filipino Culture and Society Before They Practice Their ProfessionDocument1 pageWhy Is It Important To The Filipino Architects To Understand Filipino Culture and Society Before They Practice Their ProfessionSiahara GarciaNo ratings yet

- Regeneration and Sustainable Development of Vernacular ArchitectureDocument6 pagesRegeneration and Sustainable Development of Vernacular ArchitectureDUAT Préfecture A.S.H.MNo ratings yet

- FinalDocument11 pagesFinalapi-243853404No ratings yet

- Trans Local ActDocument212 pagesTrans Local ActEvangelina Guerra Luján TheNomadNetworkNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture Iii: (Written Report)Document16 pagesHistory of Architecture Iii: (Written Report)Rod NajarroNo ratings yet

- Kinetic Architecture ThesisDocument14 pagesKinetic Architecture ThesisElsa JohnNo ratings yet

- The Countryside in Indonesian Contemporary Art andDocument28 pagesThe Countryside in Indonesian Contemporary Art andNuris CahyaningtyasNo ratings yet

- Portfolio MAE - Eng (3) - CompressedDocument19 pagesPortfolio MAE - Eng (3) - CompressedMariela YereguiNo ratings yet

- Geospaces: Continuities Between Humans, Spaces, and the EarthFrom EverandGeospaces: Continuities Between Humans, Spaces, and the EarthNo ratings yet

- Philippine Vernacular HousesDocument36 pagesPhilippine Vernacular Housesanamontana2356% (16)

- Hassan Fathy - Architecture and EnvironmentDocument4 pagesHassan Fathy - Architecture and EnvironmentHäuser TrigoNo ratings yet

- GARCIA - External SeminarDocument4 pagesGARCIA - External SeminarKIMBERLY GARCIANo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - 2-4Document33 pagesUnit 1 - 2-4Vinoth KumarNo ratings yet

- Cultural Conflict Related To Ankara S Ho PDFDocument8 pagesCultural Conflict Related To Ankara S Ho PDFAnjun SharmiNo ratings yet

- Bale Kultura: An Incorporation of Filipino Neo Vernacular Architecture On A World Class Multi-Use Convention CenterDocument9 pagesBale Kultura: An Incorporation of Filipino Neo Vernacular Architecture On A World Class Multi-Use Convention CenterMary Alexien GamuacNo ratings yet

- Anzani Maroldi ADocument46 pagesAnzani Maroldi AAnna AnzaniNo ratings yet

- Expository EssayDocument2 pagesExpository EssayBlessed Jamaeca RiveraNo ratings yet

- 巴黎 officeDocument12 pages巴黎 officeNancy XuNo ratings yet

- Look Inside PDFDocument2 pagesLook Inside PDFNancy XuNo ratings yet

- 北欧公司Document13 pages北欧公司Nancy XuNo ratings yet

- Rethinking The Urban EnvironmentDocument8 pagesRethinking The Urban EnvironmentNancy XuNo ratings yet

- Virtual Art PaperDocument5 pagesVirtual Art Paperbrandy oldfieldNo ratings yet

- PileDesignGuide PDFDocument46 pagesPileDesignGuide PDFthakrarhitsNo ratings yet

- Exercise 1 The Map Show Part of The Town of Poulton in 1900 and 1935Document2 pagesExercise 1 The Map Show Part of The Town of Poulton in 1900 and 1935Khoa DoNo ratings yet

- Rate Analysis For Renovation Work of Konabari Branch, GazipurDocument5 pagesRate Analysis For Renovation Work of Konabari Branch, Gazipurrumnaz khanNo ratings yet

- Taedo AndoDocument6 pagesTaedo AndoSuleimanNo ratings yet

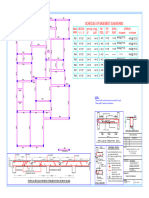

- VRB Design For ParwanDocument39 pagesVRB Design For ParwanSUPERINTENDING ENGINEERNo ratings yet

- Plinth BeamDocument1 pagePlinth BeamMCADDiS Centre for Design ,Analysis& ProjectNo ratings yet

- Vida Downtown Floorplans v3Document7 pagesVida Downtown Floorplans v3rafajr189No ratings yet

- Godrej Icon Floor PlanDocument13 pagesGodrej Icon Floor PlanRahul ChadharNo ratings yet

- Floor PlanDocument1 pageFloor PlanMuradNo ratings yet

- Water LeakageDocument20 pagesWater LeakageErdinc OzerNo ratings yet

- Air ConditioningDocument87 pagesAir ConditioningadiNo ratings yet

- Design of BridgesDocument64 pagesDesign of BridgesSukhwinder Singh Gill89% (9)

- Swing Check Valve BSP Threaded Type: Ref.: CB 2143.pasDocument1 pageSwing Check Valve BSP Threaded Type: Ref.: CB 2143.pasTien LamNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Ibs ScoreDocument59 pagesChapter 3 Ibs ScoreNur HazwaniNo ratings yet

- Glosario de Terminos en Ingenieria de PuentesDocument99 pagesGlosario de Terminos en Ingenieria de Puentesymaseda100% (1)

- Department of Architecture: A Report On False CeilingDocument12 pagesDepartment of Architecture: A Report On False CeilingAlisha PradhanNo ratings yet

- CE 405 Construction Material and Testing: Technological Institute of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesCE 405 Construction Material and Testing: Technological Institute of The PhilippinesAdrian Neil PabloNo ratings yet

- Sylvania: Stadium Pro IIDocument2 pagesSylvania: Stadium Pro IIIndra FatahNo ratings yet

- Multi Faceted Role of Temples in MedievaDocument24 pagesMulti Faceted Role of Temples in Medievasiddius85No ratings yet

- Hollow Core SpecificationsDocument8 pagesHollow Core SpecificationsJohn Carpenter100% (1)

- SkyAir R32delpage1Document17 pagesSkyAir R32delpage1HANDOYO RNo ratings yet

- Brick CalculationsDocument13 pagesBrick CalculationsMirza Mustansir BaigNo ratings yet

- KramikDocument1 pageKramikmuhammad rizal a'rofiNo ratings yet

- Daftar Harga: Push - On Fitting Untuk Pipa 25 JANUARI 2021 Rusli SaktiDocument2 pagesDaftar Harga: Push - On Fitting Untuk Pipa 25 JANUARI 2021 Rusli SaktiArif HidayatNo ratings yet

- 15-Formwork and ScaffoldingDocument21 pages15-Formwork and ScaffoldingJetty CruzNo ratings yet