Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pronóstico Sammet

Uploaded by

Cindy Bernal MOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pronóstico Sammet

Uploaded by

Cindy Bernal MCopyright:

Available Formats

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Classification and prognosis evaluation of

individual teeth—A comprehensive approach

Nachum Samet, DMD1/Anna Jotkowitz, BDS2

Following a complete evaluation of the patient, treatment planning requires the analysis of

individual teeth, accurate diagnosis, and prognosis evaluation. Currently, there is no

accepted comprehensive, standardized, and meaningful classification system for the

evaluation of individual teeth that offers a common language for dental professionals.

A search was conducted reviewing existing literature relating to classification and prognos-

tication of individual teeth. The dimensions determined to be of importance to gain an

overall perspective of the individual relative tooth prognosis were the periodontal, restora-

tive, endodontic, and occlusal plane perspectives. The authors present a comprehensive

classification system by conjugating the literature and currently accepted concepts in

dentistry. This easy-to-use system assesses the condition of individual teeth and enables

a relative prognostic value to be attached to those teeth based on tooth condition and

patient-level factors. (Quintessence Int 2009;40:377–387)

Key words: classification, dental assessment, endodontic, diagnosis, occlusal plane,

periodontic, prognosis, restorability, tooth, treatment planning

Currently there is no accepted standardized individual teeth. The classification system

tool for assessing the overall status of teeth. enables a relative prognostic value to be

Predicting whether a tooth is likely to be long- attached to each evaluated tooth for treat-

standing in the patient’s mouth, making it ment planning purposes.

appropriate to be part of the overall rehabili- The proposed classification aims to

tation of a patient, is one of the most chal- become a systematic tool that would

lenging tasks in dentistry. An accurate enhance communication among dental pro-

diagnosis and prognosis evaluation are the fessionals, be used for evaluation of cases

basis of solid treatment planning and are from a medicolegal perspective, generate a

essential when treatment options are consid- baseline for outcome assessment of treat-

ered. The aim of this article is to propose a ment modalities, and enable young and

comprehensive, standardized, and meaning- experienced clinicians alike to evaluate den-

ful classification system for the evaluation of tal conditions in a uniform way. It could also

facilitate patient understanding of the condi-

tion of their teeth, enabling them to make

informed decisions before they consent to

Assistant

1

Professor of Restorative Dentistry; Director, various treatment options.

Predoctoral Prosthodontics, Department of Restorative

Prognosis is defined as “a prediction of

Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of Dental

Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA. the probable course and outcome of a dis-

Instructor in Restorative Dentistry, Department of Restorative

2 ease, and the likelihood of recovery from a

Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of Dental disease.”1 However, evidence-based pub-

Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

lished data aimed at evaluating the relevance

Dr Nachum Samet, Department of Re-

of clinical and radiographic findings as pre-

storative Dentistry and Biomaterials Science, Harvard School of

Dental Medicine, 188 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115. Fax:

dictors for long-term prognosis are lacking in

(617) 432-0901. Email: nachum_samet@hsdm.harvard.edu the dental literature.2,3

VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009 377

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

Being aware of the complexities and limi- Periodontal literature

tations of any tool that aims to attach prog- Most of the attempts to attach a classification

nostic values to teeth, the authors used a for the prognosis of individual teeth come

“Delphi method” process4,5 to receive input from the periodontal literature. The tradition-

and feedback from clinicians and specialists al systems were based on tooth mortality19

from various backgrounds. This enabled the and did not look at the possibility of classify-

proposed classification to be based on both ing a tooth’s prognosis, based on the ability

evidence-based data, whenever available, to control the disease process and success-

and commonly accepted best practices of fully maintain the tooth as a working unit in

the profession. the dentition. In general, these studies look at

whether a tooth “survived,” and not whether

it would be appropriate to be included into a

restorative-treatment plan.

REVIEW OF CURRENT In 1978, a 22-year retrospective study by

LITERATURE Hirschfeld and Wasserman20 looked at 600

patients and compared prognosis of “favor-

Current literature does not present sufficient able” and “questionable” to actual tooth loss

evidence to enable clinicians to attach an in patients that had similar periodontal con-

absolute prognostic value to individual teeth. ditions and underwent similar treatments.

The difficulty in attaching a prognostic value Teeth considered questionable were those

to individual teeth and predicting their sur- with deep probing depths, furcation involve-

vival has been well-documented.2,6–8 In the ment, bone loss, and mobility. Although

age of evidence-based dentistry, clinicians deep probing depth is still considered a

strive to reach decisions made on sound sci- good indicator of the presence of active peri-

entific research. In the periodontal literature, odontal disease, furcation involvement and

the search for clinical and radiographic bone loss more accurately indicate past dis-

markers that can accurately predict tooth ease. Similarly, mobility may be related to

loss has proven to be quite limited.8–11 In the occlusal factors and therefore is not a reliable

restorative literature, very few attempts have indicator of the presence of active periodon-

been made to make such predictions. tal disease.21

Previously published articles look at the In 1984, Becker et al22,23 looked at the

longevity of varioous types of restorations12–15 influence that a strict periodontal mainte-

and the question of when to consider one nance program had on tooth loss.

treatment option for a particular tooth over Prognostic categories of “good,” “question-

another.16–18 However, these articles focus on able,” and “hopeless” were used. Teeth with

the success of the procedures or the suc- a least one of the following—50% bone loss,

cess of a particular restorative type rather 6- to 8-mm probing depth, Class 2 furcation,

than on the tooth itself. or anatomic variables such as a deep palatal

The difficulty is enhanced by the fact that groove on the maxillary incisors or a mesial

multiple factors may influence the prognosis furcation involvement of the maxillary first

of teeth. These include certain diseases and premolar—were classified as questionable.

systemic conditions that affect tooth progno- Teeth with more than one of the following—

sis, the patient’s motivation for treatment and more than 75% bone loss, more than 8-mm

maintenance of oral health, the quality of probing depth, Class 3 furcation involve-

treatment rendered, etc. For these reasons, ment, Class 3 mobility, poor crown-root ratio,

the goal of this classification is not to deter- unfavorable root proximity, or repeated peri-

mine an absolute prognostic value for indi- odontal abscess formation—were considered

vidual teeth, but rather to attach a relative hopeless. This study showed that it was pos-

prognostic value, which aims to enable cli- sible to accurately predict chances of tooth

nicians to distinguish between favorable survival in a well-maintained group, but those

teeth and those that are compromised to a that were not well-maintained were not as

certain degree. predictable. In the well-maintained group, the

378 VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

disease process was controlled, whereas in ment rather than just looking at the relation-

the nonmaintained group, the above-men- ship of initial prognosis to tooth mortality as

tioned factors were not all indicators of dis- is done in previous systems.19 Furthermore,

ease activity. Hence, these factors may not the need to differentiate between individual

have been accurate at predicting disease tooth prognosis and overall prognosis for the

progression. The study illustrates how peri- patient is recognized. Kwok and Caton’s19

odontal maintenance and patient compli- system focuses on only periodontal factors,

ance influence long-term prognosis. although it gives consideration to both local

In the 1990s, McGuire and Nunn docu- and systemic risk factors, which need to be

mented a series of papers based on a longi- reassessed over time.

tudinal investigation that followed 100

patients at 5, 8, and 15 years. The system Restorative literature

categorized teeth as “good,” “fair,” “poor,” The restorative literature includes effective

“questionable,” and “hopeless.” Their first 2 classification systems, but lacks a classifica-

studies,9,10 similar to previously published arti- tion system that gives clinicians a tool to

cles, based the assessment of prognosis on assess the condition and the prognostic

commonly accepted clinical findings such as value of individual teeth. It has been widely

probing depth, bone loss, furcation involve- documented that the key to long-term suc-

ment, mobility, crown-root ratio, and root cess in the restoration of endodontically

form, and concluded that these clinical treated teeth is directly related to the amount

parameters were ineffective at predicting any of remaining sound coronal tooth struc-

outcome other than “good.” The third arti- ture.25–31 A recent systematic review25 con-

cle11 evaluated the relationship of the above cluded that the most critical aspect when

clinical parameters to tooth loss. They con- dealing with a nonvital tooth is “tissue preser-

cluded that although there is a relationship vation.” Similarly, the importance of providing

between prognosis and tooth loss, initial an adequate ferrule is generally accept-

prognosis did not adequately predict tooth ed.25,27,29 Thus, the amount of remaining

survival. This led them to their fourth and final sound tooth structure should be considered

article,24 in which they began looking at host key in assessing restorability.30,31

susceptibility as a further influencing factor. Few attempts have been made to create

From this study, it seems that host factors an index that measures actual remaining

such as the presence of interleukin-1 geno- coronal dentin or grades tooth restorability.

type improved the accuracy of predicting The main problem with the development of

tooth loss, as did smoking. such an index lies in the need to assess actu-

In 2006, Muzzi et al8 directed a 10-year ret- al remaining sound tooth structure before

rospective study to evaluate the ability of clin- actual caries removal. Bandlish et al32 took

ical, radiographic, and genetic variables to 20 teeth, produced casts, and derived a

accurately predict tooth loss in a population technique to assess the amount of remain-

undergoing a strict maintenance regimen. ing dentin present after crown preparation. A

They concluded that the infrabony compo- tooth restorability index was developed to

nent of the defect and the amount of residual assess the strategic value of the remaining

bone may be good prognostic factors for dentin. This divided the teeth into sextants,

predicting tooth loss; however, more tradi- and a score of 0 to 3 was attributed whether

tional methods were proven to be of little the amount of remaining dentin was “none,”

value. “inadequate,” “questionable,” or “adequate,”

More recently, an attempt to classify prog- such that a maximum of 18 could be scored

nosis by the ability, or inability, to achieve for each tooth. The 20 teeth were analyzed

periodontal stability was made.19 Periodontal by 3 experienced dentists, who used the

stability can be monitored by routine clinical combined cast of remaining coronal dentin

examinations and radiographs, and this sys- to score the tooth restorability index for each

tem aims to help clinicians make decisions tooth. This study concluded that the sug-

for treatment planning and patient manage- gested system provided “moderate to good”

VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009 379

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

agreement among the examiners and sug- Literature related to the occlusal

gested that it was a good way of assessing plane

restorability of a tooth. No literature was found to measure the

No other articles included for review degree of super-eruption or amount of tooth

attempted to produce a quantitative system tipping within an arch that determines at what

to assess how much tooth structure remains. point a tooth becomes nonsalvageable or

Other attempts at assessing restorability33 are inappropriate for inclusion in a restorative

less didactic and avoid quantification, leaving treatment plan. However, current accepted

a nonprecise, subjective assessment as to concepts30,31,46 suggest that it is beneficial to

how much remaining tooth structure is restore teeth to the correct occlusal plane

enough to make a tooth restorable. and that over-erupted and tilted teeth can

potentially prevent normal tooth contact dur-

Endodontic literature ing function and therefore require treat-

The endodontic prognosis of a tooth in isola- ment.47–49 In partly edentulous patients, such

tion of the other categories is largely linked to teeth may create a problem when restoring

the difficulty of the case at hand.34 Potential the opposing arch.50 The scope of potential

problems include calcifications, inability to treatment ranges from enameloplasty or

isolate the tooth, resorptive defects, extra orthodontic treatment to extraction of severe-

roots and/or canals, retreatment cases, ly tilted or over-erupted teeth.51 Moderate

existing posts, ledges, and perforations. cases may require a partial or a full-coverage

Many different guides have been compiled restoration. However, some cases may require

to help clinicians determine the degree of a combination of endodontic treatment,

treatment difficulty for a given case. These crown-lengthening surgery, and a restoration

include the UCSF (University of California, to achieve a functional tooth that lies correctly

San Francisco) Endodontic Case Selection within the occlusal plane. Special attention is

System, guidelines put out by the American required when analyzing these cases, since

Association of Endodontics, the Canadian such procedures may result in a tooth that has

Academy of Endodontics, and the Dutch an unfavorable crown-root ratio, and in certain

Endodontic Treatment Index.35 The other cases may cause periodontal damage to itself

factor influencing the endodontic prognosis and/or to neighboring teeth.21,30,31 Aggressive

is the presence of a periapical radiolucency. surgical procedures in which segments of

Clinical trials have shown a lower success the maxilla or the mandible are shifted from

rate in endodontic cases with periapical radi- their original position have also been pub-

olucencies because the causative pathology lished; however, since these treatment

has been present for a longer period.36 The modalities are not readily available, they are

ability to determine the cause of a radiolu- excluded from this classification.

cency is key to understanding if a root canal

can be predictably treated.

A strong association has been noted

between the crowning of endodontically RATIONALE

treated teeth and their long-term survival.37–41 OF THE PROPOSED

This emphasizes the closely intertwined rela- CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

tionship between endodontic and restorative

prognosis. It is commonly stated that There are many types of classification system.

endodontic therapy is not complete until a Simple but powerful classifications like

coronal restoration has been placed,42–44 and Angle’s classification and the Kennedy classi-

that the coronal seal is at least as important, fication have been used in dentistry for

if not more important, than the apical seal decades. This proposed classification system

when looking at the long-term success of similarly aims to be simple while being com-

endodontically treated teeth.37,42–45 prehensive, standardized, and meaningful.

380 VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

It does not aim to allow for perfect differenti-

Ta b l e 1 Examples of patient-level risk factors

ation among all potential situations. Rather, it

includes those criteria that generally make a

Biologic risk factors

significant impact on the condition of a spe- Medical conditions that impair immune function and healing

cific tooth and therefore on its relative prog- Impaired salivary flow/function

nostic value. Medical condition or disability limiting oral hygiene

An assumption is made that current High Streptococcus mutans and Lactobacillus salivary count

Positive for interleukin-1 genotype

accepted dental standards and best prac-

Family history

tices will be employed to treat the diagnoses. Other missing teeth

Dental patient evaluation involves 2 Behavioral risk factors

sequential phases. The first phase takes Compromised or poor oral hygiene

patient-level considerations into account, and Cariogenic diet

Low exposure to fluoride

a second phase aims to classify individual

Parafunctional habits

teeth. Ability and willingness to adhere to a long-term maintenance protocol

Smoking

Patient-level considerations Financial/personal risk factors

Multiple patient-level factors play a significant Motivation for treatment

Available resources for dental care

role in the prognosis of teeth. These can be

Willingness to commit finances, time, and effort

divided into 3 main categories: biologic risks, Attitude toward losing teeth

environmental risks, and financial and behav- Understanding of one’s condition and needed treatment

ioral/personal risks (Table 1). A fourth signifi- Esthetic expectations

cant factor relates to the quality of the dental Low dental IQ

treatment and the frequency and quality of

oral health maintenance. Each of these cate-

gories affects the progression of the disease,

be it periodontal disease, caries, malocclu-

sion, etc, and will influence the likelihood of Parafunction may also increase the risk to

recovery. individual teeth or to the entire dentition.

The number of risk factors present and Because only some risk factors can be

their severity will determine the extent of their diminished or even eliminated, these should

impact, as will the ability to modify and/or be divided into modifiable and nonmodifiable

eliminate the risk factors. In general, risk fac- risk factors. If modifiable risk factors are man-

tors that are associated with high caries rate aged during and following treatment, overall

and periodontal disease are those that will tooth prognosis should be reassessed. An

challenge prognosis evaluation. These can alert can be captured in the patient chart to

be best assessed by the various caries risk emphasize the need for appropriate manage-

assessment (CAMBRA [caries management ment. Such treatments aim to diminish

by risk assessment])52–56 and periodontal risk patient likelihood of further disease progres-

assessment57,58 tools available. Such tools sion often through lifestyle changes.

categorize patients into high, medium, or low However, those patients who have multiple

risk groups, and management can be cus- nonmodifiable or unsuccessfully controlled

tomized to control disease progression. risk factors display an overall inferior case

Conditions that increase patient risk for prognosis. There are publications presenting

caries—dry mouth, diet, habits, hygiene, unfa- long-term success of oral rehabilitation of

vorable microflora, root exposure, and limited compromised dentitions. 59–61 These are

fluoride exposure—and factors that may examples of how the prognosis evaluation of

result in future deterioration of the periodon- a tooth may be improved based on positive

tal apparatus—oral hygiene, metabolic/sys- alterations of modifiable risk factors.

temic disease, unfavorable microflora, family Financial constraints, as well as a patient’s

history, smoking, age, and existing periodon- behavior and personal factors (level of moti-

tal disease—potentially increase the patient’s vation for treatment, adherence to mainte-

likelihood of further disease progression. nance care protocols, phobia, unwillingness

VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009 381

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

or inability to endure lengthy and involved is suggested when considerable patient-level

procedures, refusing treatment, etc), may risk factors are diagnosed. Patient-level risk

result in further deterioration. Therefore, they factors are reassessed over time. A decrease

should also be factored into the overall rela- in class should be considered when no

tive prognosis of all teeth and will influence change in modifiable risk factors is observed,

treatment decisions. Esthetic considerations or when significant nonmodifiable factors are

play a significant role in a patient’s treatment present. An increase in class should be con-

choice, although they do not alter tooth prog- sidered when an obvious change in modifi-

nosis per se. In certain cases, these factors able risk factors is observed.

may bring about a decision to extract a tooth

that otherwise could be saved. The system may be included into routine

clinical examination and recorded on a peri-

Evaluation of individual teeth odontal and hard tissue chart. A suggestion

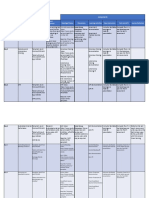

Criteria for analysis. Four main criteria and is demonstrated based on the chart used at

2 additional factors that may compromise Harvard School of Dental Medicine (Fig 1).

these criteria are evaluated:

1. Periodontal condition and alveolar bone

support DISCUSSION

2. Restorability, ie, remaining sound tooth

structure Treatment planning is a multistage process

3. Endodontic condition that involves the analysis of each tooth from

4. Occlusal plane and tooth position various aspects. Many of the diseases affect-

ing the dental structures are bacterial or

The 2 additional factors, which may com- infectious in nature. Other etiologies may

promise the above, are evaluated when appli- also cause the destruction of tooth and sup-

cable. These include: porting structures. Any chosen treatment

modality requires management and monitor-

1. Anatomic irregularities ing of the cause and of the disease process

2. Iatrogenic compromising factors in addition to mechanical/surgical treatment,

as well as the adherence to a long-term

The classification rules. The proposed maintenance protocol.59–61,69,70

classification comprises 5 classes—A, B, C, Based on the reviewed literature and

D, and X—and requires 2 steps of analysis. accepted best practices, this proposal bases

An assumption is made that current accept- the classification of the condition of teeth and

ed dental standards and best practices will their relative prognosis on 4 main criteria and

be employed to treat the diagnoses. 2 additional factors. Patient-level factors may

Step 1. Each tooth is evaluated for each alter the overall prognosis of a case, espe-

of the 4 criteria independently. The level of cially when these factors cannot be modified

severity is evaluated both based on the pre- by the patient or by treatment.

sented condition and with consideration to Periodontal status, endodontic status,

the foreseen tooth status after caries tooth position, and iatrogenic and anatomic

removal. The single most severe of these cri- factors can be assessed based on clinical

teria determines the tooth’s class (Table 2). and radiographic indicators. Understanding

Step 2. Anatomic risk factors and/or iatro- of caries progression by using the CAMBRA

genic compromising factors may result in a protocol should help clinicians assess caries

drop of a class for an individual tooth. More progression so a class can be determined.

than 2 such findings in a tooth may require a However, there may be cases in which the

further drop in class (Table 3). extent of tooth destruction by caries can only

Step 3. Patient-level risk factors may be accurately determined after mechanical

result in a decreased prognosis for the denti- removal.

tion. Therefore, a drop of 1 class for all teeth

382 VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

Ta b l e 2 An evaluation of pathology and the scale of severity

Class A A tooth in this category is one that is considered to have a good prognosis. Such a tooth is assumed

to have minimal risk of being lost in the foreseen future.

Periodontal health and 80% to 100% bone support. Can be easily maintained.

alveolar support

Remaining tooth structure 80% to 100% remaining sound coronal tooth structure. Can be easily restored.

Endodontic condition A tooth that can receive a straightforward primary endodontic treatment, or already has good

endodontic therapy.

Occlusal plane and tooth A tooth that is in the correct occlusal plane and/or position, or one that is slightly deviated from ideal

position and may require minimal enameloplasty.

Class B A tooth in this category does not belong to Class A but has a fair prognosis such that treatment out-

come is considered predictable. Such a tooth poses a low risk of being lost in the foreseen future.

Periodontal health and 50% to 80% bone support, which can be well maintained with rigorous periodontal and maintenance

alveolar support therapy. Vertical defects or furcations that can be periodontally treated to become easily cleansable or

treated predictably with regenerative therapy.62 Molars are at higher risk than single-rooted teeth.8,63

Remaining tooth structure 50% to 80% remaining sound coronal tooth structure. Involved restorative procedures result in no

infringement of biologic width, adequate ferrule,26,27,34 or good crown-root ratio and would minimally

affect adjacent structures (if at all).

Endodontic condition A failing endodontic treatment with obvious causes of failure and that can be predictably retreated, Or a

tooth that requires a difficult primary endodontic treatment.

Occlusal plane and tooth A tooth that is out of the occlusal plane and can be adjusted so that it functions within the correct

position occlusal plane. Such a tooth may require additional treatment to seal exposed dentin.

Class C A tooth in this category is one that has one or more problems and can be treated and maintained,

but its prognosis remains questionable. Such a tooth has a medium risk of being lost.

Periodontal health and 30% to 50% remaining bone support. No ongoing acute outbreaks, but maintaining cleansability is

alveolar support difficult. Periodontal therapy and a thorough maintenance program will enable the tooth to be main-

tained for an acceptable period of time.64

Remaining tooth structure 30% to 50% remaining sound coronal tooth structure. Or a tooth with so little tooth structure that achiev-

ing adequate ferrule would result in compromising the crown-root ratio to some extent, and/or may

affect adjacent structures.

Endodontic condition An acute/chronic failing endodontic treatment that presents difficulty to predictably retreat.

Occlusal plane and tooth A tooth that is out of the occlusal plane and requires multiple procedures to function within the occlusal

position plane.

Class D This category is for a compromised tooth that has a high risk of being lost. This includes those teeth

that have no active pathologic conditions requiring immediate extraction, but it may not be in the

patient’s best interest to invest in such a tooth. Since there is no obvious indication for extraction,

external factors influencing the overall case and patient factors will play a major role in determining

how to approach such a tooth.

Periodontal health and A tooth with < 30% bone support, and/or one that cannot be cleansed or maintained well and has

alveolar support evidence of active periodontal disease.

Remaining tooth structure A tooth with < 30% sound tooth structure, or one in which the extent of the lost tooth structure does not

enable a good ferrule to be achieved without totally compromising the support of the adjacent tooth

structures or crown-root ratio.

Endodontic condition A tooth with a failing endodontic treatment that cannot predictably be retreated.

Occlusal plane and tooth A tooth so severely out of the occlusal plane or severely tilted that after extensive treatment will exhibit

position reduced crown-root ratio, which will prevent it from serving as a long-term unit in the arch. Or a tooth

whose position impacts the health of the adjacent structures.

Class X A tooth in this category is nonsalvageable and is indicated for extraction. Such teeth cannot be

restored or present pathologies that currently dentistry does not have a solution for. These include

teeth that may pose risk to the patient’s health.

Periodontal health and A tooth with < 30% bone support and cannot be cleansed or maintained without acute outbreaks of

alveolar support periodontal infection.

Remaining tooth structure No remaining supragingival sound coronal tooth structure.65,66 Loss of tooth structure deep into the root

dentin/canals.30,67

Endodontic condition A vertical root fracture,3,68 or a tooth that has been retreated several times endodontically and/or surgi-

cally without resolution.

Occlusal plane and tooth A tooth so far super-erupted or tilted out of the occlusal plane that it cannot be restored into correct

position function, or would interfere with the restoration of that arch or the restoration of the opposing arch.

VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009 383

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

Ta b l e 3 Factors that result in a drop of the determined class

Examples of findings that may compromise tooth relative prognosis

Anatomic Irregularly shaped roots, multiple canals and/or roots, thin and/or short roots, and excessively conical roots cause a

drop in the prognosis and increase the risk to that tooth.30,31 This can often render a tooth with an otherwise fair or

irregularities

poor prognosis as critical or hopeless.

Iatrogenic Perforations, extensive post preparations, minimal tooth structure thickness left after preparation, dental materials that

compromising cannot be removed, etc. Without evidence of active pathology, the prognosis of a tooth with iatrogenic dentistry may even

factors be fair or good; however, if further treatment is planned or the tooth is found with other pathology or clinical or radiograph-

ic signs and symptoms, the prognosis level drops.30,31 In some cases, the tooth may even be indicated for extraction.

A proposal for the incorporation of individual tooth analysis into a conventional periodontal and hard tissue chart.

384 VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

The proposed classification system aims to who did not use this classification system.

help clinicians in the treatment planning Furthermore, students were able to devise

process, by focusing on individual and overall better and more appropriate treatment plan

prognostic value of teeth. Thus, if a tooth that options for their patients.

was originally planned to serve as an abut- This article presents a classification sys-

ment for a prosthetic unit is found to be a tem that aims to create a meaningful and

questionable tooth (Class C) or a compro- standardized tool for use among dental pro-

mised tooth (Class D), an alternative treatment fessionals. The authors are aware of the com-

plan should be considered. On the other plexities and the limitations of any tool that

hand, if these teeth were supposed to be aims to attach prognostic values to teeth.

restored as individual units, the patient goals, However, modern dentistry would benefit

financial considerations, and plans may lead from having a classification system that is

to preserving them as an interim solution. comprehensive and standardized.

Patient-level factors influence the overall

prognosis and the likelihood of recovery from

the disease, be it periodontal disease, caries,

trauma, malocclusion, etc, resulting in alter- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

native clinical decisions being reached that

are more appropriate for the overall rehabili- The authors wish to acknowledge the following special-

ists and faculty for their input (by alphabetic order): Dr

tation on the patient. The success of a par-

John Da Silva, Harvard University; Dr Renee Duff,

ticular treatment modality may also affect

University of Michigan; Dr Jacqueline Duncan,

long-term prognosis of individual teeth, but University of Connecticut; Dr Bernard Friedland, Harvard

since this is determined by the knowledge, University; Dr German Gallucci, Harvard University; Dr

skills, and comfort zone of the treating clini- Hamasat Gedaf-Dam, Geneva, Switzerland; Dr Foroud

Hakim, University of the Pacific; Dr Nadeem Karimbux,

cian, incorporating it into the classification

Harvard University; Dr David Kim, Harvard University; Dr

would impair its main purpose—which is to

Natalie Leow, Sydney, Australia; Dr Jarshen Lin, Harvard

focus on the patient’s condition. University; Dr Zeev Ormianer, Ramat Gan, Israel; Dr

Sharon Siegel, Nova University; Dr Noah Stern, Hebrew

University, Israel; Dr Hans-Peter Weber, Harvard

University; Dr Robert White, Harvard University; and Dr

Robert Wright, Harvard University.

SUMMARY

Although the dental literature presents limit-

ed evidence-based data to support the use REFERENCES

of specific criteria as prognostic tools, the

profession has developed accepted guide- 1. The American Heritage Medical Dictionary. Boston:

lines for the evaluation of teeth. The authors Houghton Mifflin, 2007.

developed the classsification system, based 2. Mordohai N, Reshad M, Jivraj S, Chee W. Factors that

on evidence-based data whenever available affect individual tooth prognosis and choices in

contemporary treatment planning. Br Dent J

and on a Delphi method process so as to

2007;202:63–72.

accumulate the profession’s accepted best

3. Simon JF. Retain or extract: The decision process.

practices.

Quintessence Int 1999;30:851–854.

Preliminary evaluation of this classification

4. Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application

system has been well received upon expert of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Man-

peer-review analysis. In the last few years, agement Science 1963;9:458–467.

dental students at Harvard School of Dental 5. Scapolo F, Miles I. Eliciting experts’ knowledge: A

Medicine have been using this classification comparison of two methods. Technological Fore-

casting Social Change 2006;73:679–704.

system as an educational tool. Although they

6. McGuire MK. Prognosis vs outcome: Predicting

had no previous experience in evaluating

tooth survival. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2000;

teeth, they were able to attach realistic prog-

21:217–220, 222, 224 passim.

nostic values to teeth more accurately and

more promptly than their predecessors,

VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009 385

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

7. Mordohai N, Reshad M, Jivraj SA.To extract or not to 21. Newman MG, Takei HH, Carranza FA. Carranza’s

extract? Factors that affect individual tooth prog- Clinical Periodontology, ed 10. St Louis: Saunders

nosis. J Calif Dent Assoc 2005;33:319–328. Elsevier, 2006.

8. Muzzi L, Nieri M, Cattabriga M, Rotundo R, Cairo F, 22. Becker W, Berg L, Becker BE. The long-term evalua-

Pini Prato GP. The potential prognostic value of tion of periodontal treatment and maintenance in

some periodontal factors for tooth loss: A retro- 95 patients. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent

spective multilevel analysis on periodontal patients 1984;4:54–71.

treated and maintained over 10 years. J Periodontol 23. Becker W, Becker BE, Berg LE. Periodontal treatment

2006;77:2084–2089. without maintenance. A retrospective study in 44

9. McGuire MK. Prognosis versus actual outcome: A patients. J Periodontol 1984;55:505–509.

long-term survey of 100 treated periodontal 24. McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual out-

patients under maintenance care. J Periodontol come. IV.The effectiveness of clinical parameters and

1991;62:51–58. IL-1 genotype in accurately predicting prognoses

10. McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual out- and tooth survival. J Periodontol 1999;70:49–56.

come. II. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in 25. Dietschi D, Duc O, Krejci I, Sadan A. Biomechanical

developing an accurate prognosis. J Periodontol considerations for the restoration of endodontically

1996;67:658–665. treated teeth: A systematic review of the literature—

11. McGuire MK, Nunn ME. Prognosis versus actual out- Part 1. Composition and micro- and macrostructure

come. III. The effectiveness of clinical parameters in alterations. Quintessence Int 2007;38:733–743.

accurately predicting tooth survival. J Periodontol 26. Pereira JR, de Ornelas F, Conti PC, do Valle AL. Effect

1996;67:666–674. of a crown ferrule on the fracture resistance of

12. Donovan TE. Longevity of the tooth/restoration com- endodontically treated teeth restored with prefab-

plex: A review. J Calif Dent Assoc 2006;34:122–128. ricated posts. J Prosthet Dent 2006;95:50–54.

13. Pjetursson BE, Sailer I, Zwahlen M, Hammerle CH. A 27. Sorensen JA, Engelman MJ. Ferrule design and frac-

systematic review of the survival and complication ture resistance of endodontically treated teeth.

rates of all-ceramic and metal-ceramic reconstruc- J Prosthet Dent 1990;63:529–536.

tions after an observation period of at least 3 years. 28. Stankiewicz N, Wilson P. The ferrule effect. Dent

Part I: Single crowns. Clin Oral Implants Res 2007;18 Update 2008;35:222–224, 227–228.

(suppl 3):73–85.

29. Stankiewicz NR, Wilson PR. The ferrule effect: A liter-

14. Pjetursson BE, Bragger U, Lang NP, Zwahlen M. ature review. Int Endod J 2002;35:575–581.

Comparison of survival and complication rates of

30. Rosenstiel SF, Land MF, Fujimoto J. Contemporary

tooth-supported fixed dental prostheses (FDPs) and

Fixed Prosthodontics, ed 4. St Louis: Mosby Elsevier,

implant-supported FDPs and single crowns (SCs).

2006.

Clin Oral Implants Res 2007;18(suppl 3):97–113.

31. Hobo S, Whitsett LD, Jacobi R, Brackett SE,

15. Sailer I, Pjetursson BE, Zwahlen M, Hammerle CH. A

Shillingburg HT. Fundamentals of Fixed Prostho-

systematic review of the survival and complication

dontics. Chicago: Quintessence, 1997.

rates of all-ceramic and metal-ceramic reconstruc-

32. Bandlish RB, McDonald AV, Setchell DJ. Assessment

tions after an observation period of at least 3 years.

of the amount of remaining coronal dentine in

Part II: Fixed dental prostheses. Clin Oral Implants

root-treated teeth. J Dent 2006;34:699–708.

Res 2007;18(suppl 3):86–96.

33. Smith CT, Schuman N. Restoration of endodontical-

16. Davarpanah M, Martinez H, Tecucianu JF, Fromentin

ly treated teeth: A guide for the restorative dentist.

O, Celletti R.To conserve or implant:Which choice of

Quintessence Int 1997;28:457–462.

therapy? Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2000;

20:412–422. 34. Yeng T, Messer HH, Parashos P. Treatment planning

the endodontic case. Aust Dent J 2007;52:S32–37.

17. Iqbal MK, Kim S. A review of factors influencing

treatment planning decisions of single-tooth 35. Pothukuchi K. Case assessment and treatment plan-

implants versus preserving natural teeth with non- ning: What governs your decision to treat, refer or

surgical endodontic therapy. J Endod 2008;34: replace a tooth that potentially requires endodon-

519–529. tic treatment? Aust Endod J 2006;32:79–84.

18. Torabinejad M, Goodacre CJ. Endodontic or dental 36. Messer HH. Clinical judgement and decision mak-

implant therapy: The factors affecting treatment ing in endodontics. Aust Endod J 1999;25:124–132.

planning. J Am Dent Assoc 2006;137:973–977. 37. Aquilino SA, Caplan DJ. Relationship between

19. Kwok V, Caton JG. Commentary: Prognosis revisited: crown placement and the survival of endodontical-

A system for assigning periodontal prognosis. ly treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent 2002;87:256–263.

J Periodontol 2007;78:2063–2071. 38. Salehrabi R, Rotstein I. Endodontic treatment out-

20. Hirschfeld L, Wasserman B. A long-term survey of comes in a large patient population in the USA: An

tooth loss in 600 treated periodontal patients. epidemiological study. J Endod 2004;30:846–850.

J Periodontol 1978;49:225–237.

386 VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009

Q U I N T E S S E N C E I N T E R N AT I O N A L

Samet/Jotkowitz

39. Tilashalski KR, Gilbert GH, Boykin MJ, Shelton BJ. 54. Featherstone JD, Adair SM, Anderson MH, et al.

Root canal treatment in a population-based adult Caries management by risk assessment: Consensus

sample: Status of teeth after endodontic treatment. statement, April 2002. J Calif Dent Assoc 2003;31:

J Endod 2004;30:577–581. 257–269.

40. Nagasiri R, Chitmongkolsuk S. Long-term survival of 55. Young DA, Buchanan PM, Lubman RG, Badway NN.

endodontically treated molars without crown cov- New directions in interorganizational collaboration

erage: A retrospective cohort study. J Prosthet Dent in dentistry: The CAMBRA Coalition model. J Dent

2005;93:164–170. Educ 2007;71:595–600.

41. Stavropoulou AF, Koidis PT. A systematic review of 56. Young DA, Featherstone JD, Roth JR, et al. Caries

single crowns on endodontically treated teeth. management by risk assessment: Implementation

Dent 2007;35:761–767. guidelines. J Calif Dent Assoc 2007;35:799–805.

42. Begotka BA, Hartwell GR. The importance of the 57. Page RC, Krall EA, Martin J, Mancl L, Garcia RI.Validity

coronal seal following root canal treatment.Va Dent and accuracy of a risk calculator in predicting peri-

J 1996;73:8–10. odontal disease. J Am Dent Assoc 2002;133:

43. Chugal NM, Clive JM, Spangberg LS. Endodontic 569–576.

treatment outcome: Effect of the permanent 58. Page RC, Martin J, Krall EA, Mancl L, Garcia R.

restoration. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Longitudinal validation of a risk calculator for perio-

Radiol Endod 2007;104:576–582. dontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2003;30:819–827.

44. Saunders WP, Saunders EM. Coronal leakage as a 59. Amsterdam M, Weisgold AS. Periodontal prosthesis:

cause of failure in root-canal therapy: A review. A 50-year perspective. Alpha Omegan 2000;93:

Endod Dent Traumatol 1994;10:105–108. 23–30.

45. Hommez GM, Verhelst R, Claeys G, Vaneechoutte M, 60. Libby G, Arcuri MR, LaVelle WE, Hebl L. Longevity of

De Moor RJ. Investigation of the effect of the coro- fixed partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1997;78:

nal restoration quality on the composition of the 127–131.

root canal microflora in teeth with apical periodon- 61. Lulic M, Bragger U, Lang NP, Zwahlen M, Salvi GE.

titis by means of T-RFLP analysis. Int Endod J Ante’s (1926) law revisited: A systematic review on

2004;37:819–827. survival rates and complications of fixed dental

46. Dawson PE. Functional occlusion: From TMJ to smile prostheses (FDPs) on severely reduced periodontal

design. St Louis: Mosby, 2006. tissue support. Clin Oral Implants Res 2007;18(suppl

47. Craddock HL, Youngson CC, Manogue M, Blance A. 3):63–72.

Occlusal changes following posterior tooth loss in 62. Cortellini P, Stalpers G, Pini Prato G, Tonetti MS.

adults. Part 2. Clinical parameters associated with Long-term clinical outcomes of abutments treated

movement of teeth adjacent to the site of posterior with guided tissue regeneration. J Prosthet Dent

tooth loss. J Prosthodont 2007;16:495–501. 1999;81:305–311.

48. Craddock HL, Youngson CC, Manogue M, Blance A. 63. Checchi L, Montevecchi M, Gatto MR, Trombelli L.

Occlusal changes following posterior tooth loss in Retrospective study of tooth loss in 92 treated peri-

adults. Part 1: A study of clinical parameters associ- odontal patients. J Clin Periodontol 2002;29:

ated with the extent and type of supraeruption in 651–656.

unopposed posterior teeth. J Prosthodont 2007;16: 64. Fardal O, Johannessen AC, Linden GJ.Tooth loss dur-

485–494. ing maintenance following periodontal treatment

49. Craddock HL, Youngson CC. Eruptive tooth move- in a periodontal practice in Norway. J Clin Perio-

ment—The current state of knowledge. Br Dent J dontol 2004;31:550–555.

2004;197:385–391. 65. Sorensen JA. Preservation of tooth structure. J Calif

50. McGivney GP, Castleberry DJ, McCracken WL. Dent Assoc 1988;16:15–22.

McCracken’s Removable Partial Prosthodontics. St 66. Sorensen JA, Martinoff JT. Clinically significant fac-

Louis: Mosby, 1994. tors in dowel design. J Prosthet Dent 1984;52:

51. Graber TM, Vanarsdall RL, Vig KWL. Orthodontics: 28–35.

Current Principles and Techniques, ed 4. St Louis: 67. Spear F. When to restore, when to remove: The sin-

Mosby, 2005. gle debilitated tooth. Compend Contin Educ Dent

52. Jenson L, Budenz AW, Featherstone JD, Ramos- 1999;20:316–318, 322–323, 327–328.

Gomez FJ, Spolsky VW, Young DA. Clinical protocols 68. Weine FS. Endodontic Therapy. St Louis: Mosby,

for caries management by risk assessment. J Calif 2004.

Dent Assoc 2007;35:714–723.

69. Holm-Pedersen P, Lang NP, Muller F. What are the

53. Featherstone JD. The caries balance: The basis for longevities of teeth and oral implants? Clin Oral

caries management by risk assessment. Oral Health Implants Res 2007;18(suppl 3):15–19.

Prev Dent 2004;2(suppl 1):259–264.

70. Tomasi C, Wennstrom JL, Berglundh T. Longevity of

teeth and implants—A systematic review. J Oral

Rehabil 2008;35(suppl 1):23–32.

VOLUME 40 • NUMBER 5 • MAY 2009 387

You might also like

- Self Love Inner Child Healing With EFTDocument11 pagesSelf Love Inner Child Healing With EFTAnonymous fUL4SPRsAf100% (1)

- Unit IG2: Risk AssessmentDocument22 pagesUnit IG2: Risk Assessmentprijith j100% (6)

- Automation of Drug Dispensing: Feedback From A Hospital PharmacyDocument5 pagesAutomation of Drug Dispensing: Feedback From A Hospital PharmacyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Lyons Et Al-2017-Periodontology 2000Document4 pagesLyons Et Al-2017-Periodontology 2000Julio César PlataNo ratings yet

- Effect of Gingival Biotype On Orthodontic TreatmenDocument8 pagesEffect of Gingival Biotype On Orthodontic Treatmensolodont1No ratings yet

- KS3 Science Revision - Worksheets With AnswersDocument108 pagesKS3 Science Revision - Worksheets With AnswersTony TitanicNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Study On Stressors Stress Symptoms and Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students PASCALDocument47 pagesA Qualitative Study On Stressors Stress Symptoms and Coping Mechanisms Among High School Students PASCALASh tabaog0% (1)

- 11 - Novel Decision Tree Algorithms For The Treatment Planning of Compromised TeethDocument10 pages11 - Novel Decision Tree Algorithms For The Treatment Planning of Compromised TeethkochikaghochiNo ratings yet

- Open-Bite Malocclusion: Treatment and StabilityFrom EverandOpen-Bite Malocclusion: Treatment and StabilityGuilherme JansonRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 2009 Avila A Novel Decision-Making Process For Tooth Retention or ExtractionDocument12 pages2009 Avila A Novel Decision-Making Process For Tooth Retention or ExtractionDiego LemurNo ratings yet

- Sametclassificationarticle PDFDocument12 pagesSametclassificationarticle PDFAmada GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Samet Pronostico Samet Pronostico: Odontologia (Universidad Antonio Nariño) Odontologia (Universidad Antonio Nariño)Document13 pagesSamet Pronostico Samet Pronostico: Odontologia (Universidad Antonio Nariño) Odontologia (Universidad Antonio Nariño)SebastianRomeroCarmonaNo ratings yet

- Samet Clasificacion de PronosticoDocument13 pagesSamet Clasificacion de PronosticoAna María ReyesNo ratings yet

- 2009 Samet Classification Prognosis Evaluation Individual Teeth Comprehensive ApproachDocument12 pages2009 Samet Classification Prognosis Evaluation Individual Teeth Comprehensive ApproachFabian SanabriaNo ratings yet

- Classification and PrognosisDocument12 pagesClassification and Prognosisjuan esteban soto estradaNo ratings yet

- Kao 2009 Strategic Extraction PerioDocument7 pagesKao 2009 Strategic Extraction PeriojeremyvoNo ratings yet

- New Paradigms in Prosthodontic Treatment PlanningDocument8 pagesNew Paradigms in Prosthodontic Treatment PlanningNanda Iswa MaysferaNo ratings yet

- Bilhan 2012Document7 pagesBilhan 2012laur112233No ratings yet

- The Future of Complete Dentures inDocument15 pagesThe Future of Complete Dentures inFabian ArangoNo ratings yet

- Commentary: Prognosis Revisited: A System For Assigning Periodontal PrognosisDocument9 pagesCommentary: Prognosis Revisited: A System For Assigning Periodontal PrognosisAd AlNo ratings yet

- Factores Relacionados-Dientes Fisurados - RCTDocument23 pagesFactores Relacionados-Dientes Fisurados - RCTVitall Dent Endodoncia Odontologia integralNo ratings yet

- Prognosis CatonDocument9 pagesPrognosis CatonMariana Moraga RoblesNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Development of Prognostic Indicators Using Classification and Regression Trees (CART) For SurvivalDocument17 pagesNIH Public Access: Development of Prognostic Indicators Using Classification and Regression Trees (CART) For Survivalregina marthaNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic treatment stability and periodontal condition with fiberotomyDocument14 pagesOrthodontic treatment stability and periodontal condition with fiberotomysergioloamNo ratings yet

- Jap 4 109Document7 pagesJap 4 109Buzatu IonelNo ratings yet

- Perio-Prosthodontics Considerations in Removable Partial Denture: The Role of The ProsthodontistDocument9 pagesPerio-Prosthodontics Considerations in Removable Partial Denture: The Role of The ProsthodontistAira Grace PadillaNo ratings yet

- Jurnall 1Document8 pagesJurnall 1Yon AditamaNo ratings yet

- Tooth-Implant Supported RemovableDocument29 pagesTooth-Implant Supported RemovabletaniaNo ratings yet

- Removable Partial Dentures: ReferencesDocument5 pagesRemovable Partial Dentures: ReferencesKakak AdekNo ratings yet

- Clinical factors predict periodontal prognosisDocument8 pagesClinical factors predict periodontal prognosissnowy19No ratings yet

- Denture Adhesives Improve Denture PerformanceDocument2 pagesDenture Adhesives Improve Denture PerformancepaulinaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S153233821830071X Main PDFDocument4 pages1 s2.0 S153233821830071X Main PDFOrtodoncia UNAL 2020No ratings yet

- Prevalence of Peg-Shaped Maxillary Permanent Lateral Incisors: A Meta-AnalysisDocument13 pagesPrevalence of Peg-Shaped Maxillary Permanent Lateral Incisors: A Meta-Analysisplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Longetivity of DentureDocument9 pagesLongetivity of DentureShyam DangarNo ratings yet

- Prosthodontic Treatment Planning Current Practice Principles and TechniquesDocument4 pagesProsthodontic Treatment Planning Current Practice Principles and TechniquesZiad RabieNo ratings yet

- Gugnani 2020Document2 pagesGugnani 2020Dr. Daniel DeluizNo ratings yet

- GOBBATODocument11 pagesGOBBATOBianca MarcheziNo ratings yet

- Adj 12440Document9 pagesAdj 12440ShreyaNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Periodontology Best Evidence Consensus Statement On Modifying Peridontal Phenotype in Preparation For Orthodontic and Restorative Treatment 2019Document10 pagesAmerican Academy of Periodontology Best Evidence Consensus Statement On Modifying Peridontal Phenotype in Preparation For Orthodontic and Restorative Treatment 2019Implant DentNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Root Resorption After Dental TraumaDocument15 pagesPathophysiological Mechanisms of Root Resorption After Dental TraumadianaNo ratings yet

- Journal of Periodontology - 2018 - Ercoli - Dental Prostheses and Tooth Related FactorsDocument14 pagesJournal of Periodontology - 2018 - Ercoli - Dental Prostheses and Tooth Related FactorsTesis Luisa MariaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Denture Quality Attributes On Satisfaction and Eating DifficultiesDocument10 pagesThe Effect of Denture Quality Attributes On Satisfaction and Eating Difficultieslaur112233No ratings yet

- Full Mouth Rehabilitation of Adult Rampant Caries With Pragmatic ApproachDocument6 pagesFull Mouth Rehabilitation of Adult Rampant Caries With Pragmatic ApproachNur Muhammad GhifariNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0300571213001917 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0300571213001917 MainAldrinNo ratings yet

- Dental Prostheses and Tooth-Related FactorsDocument14 pagesDental Prostheses and Tooth-Related FactorsMartty BaNo ratings yet

- Disease Staging Index For Aggressive Periodontitis: Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry August 2017Document9 pagesDisease Staging Index For Aggressive Periodontitis: Oral Health & Preventive Dentistry August 2017Jayne MaryNo ratings yet

- Vitali - 2021 - Asociación Entre Tto Ortodoncia y Cambios PulparesDocument14 pagesVitali - 2021 - Asociación Entre Tto Ortodoncia y Cambios PulparesMICHAEL ERNESTO QUINCHE RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsDocument8 pagesEffectiveness of Interceptive Orthodontic Treatment in Reducing MalocclusionsAriana de LeonNo ratings yet

- Clinical Decision-Making For Caries Management in Primary TeethDocument10 pagesClinical Decision-Making For Caries Management in Primary TeethbradleycampbellNo ratings yet

- 2007 Mordohai Factors That Affect Individual Tooth Prognosis and Choices in Contemporary Treatment Planning British Dental JournalDocument10 pages2007 Mordohai Factors That Affect Individual Tooth Prognosis and Choices in Contemporary Treatment Planning British Dental Journalplayer osamaNo ratings yet

- Functional Assessment of Removable Complete Dentures: Riginal RticleDocument3 pagesFunctional Assessment of Removable Complete Dentures: Riginal Rticlelaur112233No ratings yet

- Dental Anomalies in Different Growth and Skeletal Malocclusion PatternsDocument7 pagesDental Anomalies in Different Growth and Skeletal Malocclusion PatternsShruthi KamarajNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Prosto 3Document6 pagesJurnal Prosto 3Naima Rifda AnitammaNo ratings yet

- Prosthetic Rehabilitation and Treatment Outcome of Partially Edentulous Patients With Severe Tooth Wear: 3-Years ResultsDocument21 pagesProsthetic Rehabilitation and Treatment Outcome of Partially Edentulous Patients With Severe Tooth Wear: 3-Years ResultsAlina AlinaNo ratings yet

- The Removable Partial Denture EquationDocument10 pagesThe Removable Partial Denture Equationapi-3710948100% (1)

- Impacted Central Incisors Factors Affecting Prognosis and Treatment Duration 2015 American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial OrthopedicsDocument8 pagesImpacted Central Incisors Factors Affecting Prognosis and Treatment Duration 2015 American Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial OrthopedicskjunaidNo ratings yet

- Dentists Decisions Regarding The Need For Cuspal PDFDocument10 pagesDentists Decisions Regarding The Need For Cuspal PDFRohma DwiNo ratings yet

- Dentists Decisions Regarding The Need For Cuspal PDFDocument10 pagesDentists Decisions Regarding The Need For Cuspal PDFRohma DwiNo ratings yet

- Recommended Treatment of Cracked Teeth: Results From The National Dental Practice-Based Research NetworkDocument8 pagesRecommended Treatment of Cracked Teeth: Results From The National Dental Practice-Based Research NetworkNetra TaleleNo ratings yet

- Evidence-Based Orthodontics For The 21st Century: Cover StoryDocument6 pagesEvidence-Based Orthodontics For The 21st Century: Cover StoryDeep GargNo ratings yet

- Management of The Developing Dentition and Occlusion in Pediatric DentistryDocument18 pagesManagement of The Developing Dentition and Occlusion in Pediatric DentistryPAULA ANDREA RAMIREZ ALARCONNo ratings yet

- Oral Health - JKCD 2019Document6 pagesOral Health - JKCD 2019Jawad TariqNo ratings yet

- The Viazis Classification of Malocclusion: Journal of Dental Health Oral Disorders & TherapyDocument9 pagesThe Viazis Classification of Malocclusion: Journal of Dental Health Oral Disorders & TherapyWilmer Yanquen VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Esthetic Oral Rehabilitation with Veneers: A Guide to Treatment Preparation and Clinical ConceptsFrom EverandEsthetic Oral Rehabilitation with Veneers: A Guide to Treatment Preparation and Clinical ConceptsRichard D. TrushkowskyNo ratings yet

- Latex Allergy ManagementDocument7 pagesLatex Allergy ManagementCindy Bernal MNo ratings yet

- Manejo Pacientes Anticoagulados en Cirugía OralDocument9 pagesManejo Pacientes Anticoagulados en Cirugía OralCindy Bernal MNo ratings yet

- CamScanner Scanned Doc PagesDocument12 pagesCamScanner Scanned Doc PagesCindy Bernal MNo ratings yet

- Clasificación Dolor OrofacialDocument8 pagesClasificación Dolor OrofacialCindy Bernal MNo ratings yet

- Oral Malignant Melanoma A Review of The LiteratureDocument7 pagesOral Malignant Melanoma A Review of The Literaturecapau87No ratings yet

- Brien Et Al - 2012Document21 pagesBrien Et Al - 2012Marzia SmitaNo ratings yet

- Nursing DiagnosisDocument16 pagesNursing DiagnosisShemie TutorNo ratings yet

- Jurnal VaskularDocument6 pagesJurnal VaskulardrelvNo ratings yet

- Patient Assessment Marking SheetDocument2 pagesPatient Assessment Marking SheetJim Courtney100% (4)

- Overcome Anxiety, Depression and Gain ControlDocument3 pagesOvercome Anxiety, Depression and Gain ControlPranavNo ratings yet

- He Izard Heet: Wizard SchoolDocument3 pagesHe Izard Heet: Wizard SchoolItay OrgilNo ratings yet

- Zombie Apocalypse Synthesis Group EssayDocument4 pagesZombie Apocalypse Synthesis Group Essayapi-514832443No ratings yet

- MHN MUHS External and InternalDocument5 pagesMHN MUHS External and Internalanupa sukalikarNo ratings yet

- Washington HospitalsDocument9 pagesWashington HospitalsJoe FrascaNo ratings yet

- Graft vs. Host Disease ExplainedDocument35 pagesGraft vs. Host Disease ExplainedSaad KhanNo ratings yet

- ORGS 1136 - Week 4 Notes ORGS 1136 - Week 4 NotesDocument3 pagesORGS 1136 - Week 4 Notes ORGS 1136 - Week 4 NotesTara FGNo ratings yet

- Hiv and Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission (PMTCT) : by Gebremaryam TDocument100 pagesHiv and Prevention of Mother-To-Child Transmission (PMTCT) : by Gebremaryam THambal AhamedNo ratings yet

- CefabroxilDocument12 pagesCefabroxilRawdatul JannahNo ratings yet

- DUPHAT 2016 LeafletDocument2 pagesDUPHAT 2016 LeafletIPSF EMRONo ratings yet

- DR Preeti UdaipurDocument19 pagesDR Preeti Udaipurpreeti senthiyaNo ratings yet

- Final OcTa Nov 16 OCTA Research Monitoring ReportDocument36 pagesFinal OcTa Nov 16 OCTA Research Monitoring ReportRappler100% (1)

- Suicide Ideation and Attempts in A Pediatric Emergency Department Before and During COVID-19Document8 pagesSuicide Ideation and Attempts in A Pediatric Emergency Department Before and During COVID-19mikoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 06 Try inDocument18 pagesChapter 06 Try inمحمد حسنNo ratings yet

- Assignment: TopicDocument12 pagesAssignment: TopicAthul RNo ratings yet

- Red Cross Training Content MapDocument2 pagesRed Cross Training Content MapHoward SeibertNo ratings yet

- I STATDocument24 pagesI STATPraveen RamasamyNo ratings yet

- Neuritis VestibularisDocument2 pagesNeuritis VestibularisMahesa Kurnianti PutriNo ratings yet

- Transcultural Nursing: Madeleine LeiningerDocument28 pagesTranscultural Nursing: Madeleine LeiningerJoyce EricaNo ratings yet

- Public HealthDocument28 pagesPublic HealthDoc Weh Akut-Salutan100% (1)

- Mohammadi 202. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among A Iranian Computer UsersDocument6 pagesMohammadi 202. Work-Related Musculoskeletal Disorders Among A Iranian Computer UsersFioriAmeliaHathawayNo ratings yet