Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jurnal 1 About Tooth Health

Uploaded by

Abdi SiregarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jurnal 1 About Tooth Health

Uploaded by

Abdi SiregarCopyright:

Available Formats

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH

OPINION

Improving the response to future pandemics

requires an improved understanding of the

role played by institutions, politics,

organization, and governance

Peter Berman1*, Maxwell A. Cameron ID1, Sarthak Gaurav ID2, George Gotsadze ID3, Md

Zabir Hasan4, Kristina Jenei ID1, Shelly Keidar1, Yoel Kornreich ID5, Chris Lovato1, David

M. Patrick1,6, Malabika Sarker ID7, Paolo Sosa-Villagarcia ID8, Veena Sriram1,

Candice Ruck1

a1111111111 1 School of Population and Public Health, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada, 2 Shailesh J.

a1111111111 Mehta School of Management, Indian Institute of Technology Bombay, Mumbai, India, 3 Curatio International

a1111111111 Foundation, Tbilisi, Georgia, 4 Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland,

United States of America, 5 Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel, 6 British Columbia Center for Disease

a1111111111

Control, Vancouver, Canada, 7 James P. Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Dhaka,

a1111111111 Bangladesh, 8 Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, Lima, Peru

* peter.berman@ubc.ca

OPEN ACCESS

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a global crisis that continues to challenge the resil-

Citation: Berman P, Cameron MA, Gaurav S, ience of health systems worldwide. Although most jurisdictions had timely access to knowl-

Gotsadze G, Hasan MZ, Jenei K, et al. (2023) edge emerging globally, there was great diversity in actual responses–including timing, choice

Improving the response to future pandemics

of action, and intensity of implementation—across different jurisdictions, with resulting varia-

requires an improved understanding of the role

played by institutions, politics, organization, and tions in health and social outcomes. As countries emerge from the pandemic, global efforts are

governance. PLOS Glob Public Health 3(1): taking shape to use the lessons from COVID-19 to improve preparedness for future pandem-

e0001501. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. ics. Although many assessments have already been made regarding overall national perfor-

pgph.0001501 mance in responding to COVID-19, these have mostly focused on more ‘downstream’ actions

Editor: Boghuma K. Titanji, Emory University and factors such as measures taken to reduce infection, clinical approaches to disease manage-

School of Medicine, UNITED STATES ment, and technical capacity and have overlooked the ‘upstream’ forces that shaped and drove

Published: January 20, 2023 those responses. However, for the proposed reform initiatives to be effective will require a

more in-depth understanding of the ‘upstream’ factors that drove the wide variation in

Copyright: © 2023 Berman et al. This is an open

responses to COVID-19. To address this, an interdisciplinary team at the University of British

access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which Columbia has proposed a framework to unite scholarship into the institutional, political, orga-

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and nizational, and governance (IPOG) aspects of the COVID-19 response.

reproduction in any medium, provided the original One of the most notable features of the response to COVID-19 has been how actual

author and source are credited. responses had little association with prior technical assessments of health systems’ prepared-

Funding: This work has benefitted from generous ness and capacities, even in countries at similar economic levels. Others have observed the

financial support from the University of British extent to which the outcomes of the real-world response differed from pre-pandemic rankings

Columbia’s Faculty of Medicine (GR004683) and conferred by preparedness indicators such as the Global Health Security Index (GHSI) [1] and

Peter Wall Institute for Advanced Studies

the Joint External Evaluations under the International Health Regulations [2], suggesting that

(GR016648). The Canadian Institute for Health

Research has also provided support for developing

factors influencing the effectiveness of real-world pandemic responses were not captured well

and applying for this work in British Columbia by these approaches. While large differences in financial and physical resources were pre-

through a 2020 Operating Grant: COVID-19 sumed to be determinative, analyses have shown that differences in policy interventions were

Research Gaps and Priorities award (GR019157). more heavily responsible than socio-economic differences for the wide range in mortality fig-

None of the sponsors were involved in the research ures between nations [3]. The available evidence suggests that the vastly different experiences

nor writing of this manuscript.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001501 January 20, 2023 1/5

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH

Competing interests: The authors have declared of many countries were driven largely by the wide range of contextual factors and social deter-

that no competing interests exist. minants that shaped countries’ response strategies to COVID-19 [4]. Given this diversity in

responses, implementation, and subsequent health outcomes, it is apparent that there is a need

to focus more inquiry on those key ‘upstream’ factors, such as institutional norms, processes of

governance, politics, and the organization of health systems including the elements tasked

with public health response, that influence effective decision-making and response during

health emergencies such as COVID-19. These upstream factors must be better understood and

the knowledge thus gained applied in improving preparedness for future public health crises.

Even prior to the pandemic, awareness was growing of how vital governance is in the func-

tion of health systems. Shortcomings in performance linked to governance exacerbate inequal-

ity. A critical feature of effective governance is that it can enable better performance even in

the absence of good leadership, and can function as a defense in the face of poor leadership.

More recently, there has already been substantial acknowledgment of the role that governance

has played in pandemic responses. COVID-19 clearly demonstrated that public health capacity

alone is not a guarantor of a robust crisis response, and that governance has been a key deter-

minant of an effective pandemic response [5].

The influence of political factors has also been identified as a driver of pandemic responses.

Researchers have assessed how the pandemic response differed between centralized and decen-

tralized political systems [6], as well as between more democratic and more authoritarian sys-

tems [7]. Political partisanship has also been identified as a driver of pandemic responses at

the level of both governments and individuals.

What has been largely overlooked, however, is that politics and governance do not exist in a

vacuum, but rather influence and are influenced by other factors such as institutional norms

and the structure and functioning of key organizations tasked with public health response.

There are major gaps in our research here as well, such as the absence of system-level and com-

parable descriptors for organizational structure. For example, it has been acknowledged that

South Korea’s institutions, shaped and reformed in the aftermath of MERS, have been instru-

mental to that nation’s successful response to COVID-19 [8]. Recent calls to expand National

Public Health Institutes in support of future pandemic responses need further study. A recent

scoping review of NPHI’s cited the paucity of systematic research available on this topic and

identified several specific areas that would benefit from more in-depth investigation [9]

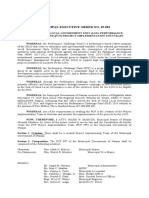

What is particularly interesting is that, although institutions, politics, governance, and pub-

lic health organization have all been given some degree of individual consideration in prior

analyses of the pandemic response, research has seldom incorporated a broader view of the

interconnectedness of these upstream factors and the need to consider that in future response

design. It is our contention that COVID-19 has exposed the need to expand, deepen, and

sharpen the focus of investigation to explore the intersection of all of these key contextual fac-

tors and how they combine to influence outcomes. This assertion drove the development of

our IPOG analytical framework, the details of which have been published elsewhere [10]. We

have applied this framework, elaborated on in Fig 1, with colleagues in multiple jurisdictions

both within Canada as well as internationally. We posit that by incorporating these upstream

factors into a single analytical framework, we can better understand how they interact with

and influence one another in the development and deployment of a pandemic response. It

would then be possible to propose improvements that could enable better responses to future

pandemic threats and other health emergencies.

Although we initially elaborated and applied this framework to jurisdictions’ responses to

COVID-19, we are encouraged by the relevance of the intersecting role of these factors to

improving understanding of the social response to other health needs. Global responses, such

as the weak capacities of multinational organizations to assure vaccine equity across countries

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001501 January 20, 2023 2/5

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH

Fig 1. An analytical framework for investigating the impact of institutions, politics, organizations, and governance on the response to COVID-19.

(Brubacher LJ, Hasan MZ, Sriram V, et al. Investigating the Influence of Institutions, Politics, Organizations, and Governance on the COVID-19 Response in

British Columbia, Canada: a Jurisdictional Case Study Protocol).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001501.g001

during COVID-19, can be linked to the interface between global organization structures and

national political dynamics. Emerging population health needs such as those related to mental

health and substance use or food and diet-related causes of chronic disease epidemics require

a broader view of relevant organizational actors and political channels of influence on policy

and implementation. We feel these and other domains of emerging policy action would benefit

from greater attention to the linkages we have explored that enhance more narrow discipline-

based modes of enquiry.

COVID-19 has prompted governments around the world to reflect on how to better pre-

pare for the next pandemic. Increasingly, it is evident that to be truly successful, future prepa-

rations must also be designed to address the contextual factors that influence societal

responses. Greater attention is needed to how IPOG factors have influenced the range of

responses and outcomes or how evidence on these factors can support proposed reforms. This

requires incorporating these considerations in ongoing planning for new investments in pre-

paredness and resilience. This must be supported by broadening the scope of research to

include these factors. However, nearly two and a half years into the pandemic, what we see

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001501 January 20, 2023 3/5

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH

instead is a desire among societies to move on without fully understanding how we got here or

what reforms are necessary to improve future health system resilience and prevent similar out-

comes when the next pandemic strikes. We need to learn more about IPOG and how these fac-

tors can be managed to improve future preparedness and outcomes. We strongly urge that the

current efforts to strengthen and invest in preparedness, such as those proposed recently by

the G20 and the new Financial Intermediary Facility at the World Bank, along with the next

iterations of the International Health Regulations, explicitly incorporate analyses of IPOG fac-

tors in national and sub-national settings. As governments seek to improve preparations for

future pandemics, we ignore these considerations at our peril.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the members of the UBC Working Group on Health Systems

Response toCOVID-19 (Michael Cheng, Dr. Milind Kandlikar, Dr.Tammi Whelan, Austin

Wu, & Mahrukh Zahid), as well as our former Graduate Research Assistant Sydney Whiteford

that contributed their wisdom and expertise to this work. We additionally wish to acknowl-

edge the work of our International IPOG teams in Bangladesh (Syeda Tahmina Ahmed, Dr.

Mrittika Barua, Susmita Chakma, Protyasha Ghosh, Shams Shabab Haider, Suhi Hanif, & Tas-

nim Kabir), Georgia (Dr. Maia Uchaneishvili), India (Dr. Satish Agnihotri, Arpit Arora,

Khushboo Balani, Dr. Sambuddha Chaudhuri, & Sujata Saunik), and Peru (Veronica Hur-

tado). We also want to acknowledge the comments and suggestions received from participants

in three international virtual roundtable discussions to further the development of the Interna-

tional Working Group on Health Systems Response to COVID-19 (healthsystems.pwias.ubc.

ca) and students in UBC’s SPPH 581Y graduate student research seminar in Spring 2021.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Peter Berman, Maxwell A. Cameron, Md Zabir Hasan, Kristina Jenei,

Shelly Keidar, Yoel Kornreich, Chris Lovato, David M. Patrick.

Data curation: Yoel Kornreich.

Formal analysis: Peter Berman, Yoel Kornreich, Candice Ruck.

Funding acquisition: Peter Berman.

Investigation: Peter Berman, Maxwell A. Cameron, Md Zabir Hasan, Kristina Jenei, Shelly

Keidar, Chris Lovato, David M. Patrick, Veena Sriram.

Methodology: Peter Berman, Maxwell A. Cameron, Md Zabir Hasan, Kristina Jenei, Shelly

Keidar, Chris Lovato, David M. Patrick, Veena Sriram.

Project administration: Kristina Jenei, Shelly Keidar, Candice Ruck.

Supervision: Peter Berman, Shelly Keidar.

Validation: Maxwell A. Cameron, Sarthak Gaurav, George Gotsadze, Md Zabir Hasan, Kris-

tina Jenei, Shelly Keidar, Chris Lovato, David M. Patrick, Malabika Sarker, Paolo Sosa-Vil-

lagarcia, Veena Sriram.

Visualization: Peter Berman, Maxwell A. Cameron, Md Zabir Hasan, Kristina Jenei, Shelly

Keidar, Yoel Kornreich, Chris Lovato, David M. Patrick, Veena Sriram, Candice Ruck.

Writing – original draft: Peter Berman, Maxwell A. Cameron, Md Zabir Hasan, Kristina

Jenei, Shelly Keidar, Chris Lovato, David M. Patrick, Veena Sriram.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001501 January 20, 2023 4/5

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH

Writing – review & editing: Peter Berman, Maxwell A. Cameron, Sarthak Gaurav, George

Gotsadze, Kristina Jenei, Yoel Kornreich, Malabika Sarker, Paolo Sosa-Villagarcia, Veena

Sriram, Candice Ruck.

References

1. Cameron EE, Nuzzo JB, Bell JA, Nalabandian M, O’Brien J, League A, et al. Global Health Security

Index: Building Collective Action and Accountability. Nuclear Threat Initiative and Johns Hopkins Centre

for Health Security. 2019 [cited 2022 September 13]. Available from: https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-

content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf.

2. https://www.ghsindex.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/2019-Global-Health-Security-Index.pdf Stowell

D, Garfield R How can we strengthen the Joint External Evaluation? BMJ Global Health 2021; 6:

e004545. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004545 PMID: 34006517

3. Balmford B, Annan JD, Hargreaves JC, Altoe M, Bateman IJ. Cross-Country Comparisons of Covid-19:

Policy, Politics and the Price of Life. Environ Resource Econ 2020; 76: 525–551. https://doi.org/10.

1007/s10640-020-00466-5 PMID: 32836862

4. Abrams EM, Szefler SJ. COVID-19 and the impact of social determinants of health. Lancet Respir Med

2020; 8: 659–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30234-4 PMID: 32437646

5. Al Saidi AMO, Nur FA, Al-Mandhari AS, El Rabbat M, Hafeez A, Abubakar A. Decisive leadership is a

necessity in the COVID-19 response. Lancet 2020; 396: 295–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736

(20)31493-8 PMID: 32628904

6. Greer SL, Rozenblum S, Falkenbach M, Loblova O, Jarman H, Williams N, et al. Centralizing and

decentralizing governance in the COVID-19 pandemic: The politics of credit and blame. Health Policy

2022; 126: 408–417. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2022.03.004 PMID: 35331575

7. Saam NJ, Friedrich C, Engelhardt H. The value conflict between freedom and security: Explaining the

variation of COVID-19 policies in democracies and autocracies. PloS One 2022; 17: e0274270. https://

doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0274270 PMID: 36083998

8. Park J. Institutions Matter I Fighting COVID-19: Public Health, Social Policies, and the Control Tower in

South Korea. In: Greer S, King E, Massard da Fonseca E, Peralta-Santos A. Coronavirus Politics: The

Comparative Politics and Policy of COVID-19 [Internet]. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

2021 [cited 2022 Sept 13]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/fulcrum.jq085n03q.

9. Myhre SL, French SD, Bergh A. National public health institutes: A scoping review. Global Public Health

2022; 17: 1055–1072. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1910966 PMID: 33870871

10. [Preprint] Wu A, Khanna S, Keidar S, Berman P, UBC Working Group on Health Systems Response to

COVID-19, Brubacher LJ. How have researchers defined institutions, politics, organizations, and gover-

nance in research related to pandemic an epidemic response? A scoping study. Health Policy and Plan-

ning 2022.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001501 January 20, 2023 5/5

You might also like

- Nampsp 2021 202104cDocument29 pagesNampsp 2021 202104cHarto LinelejanNo ratings yet

- The Need For A Comprehensive Public Health Approach To Preventing Child Sexual AbuseDocument7 pagesThe Need For A Comprehensive Public Health Approach To Preventing Child Sexual Abusesopi julianaNo ratings yet

- BMJ 2011 343d4163Document3 pagesBMJ 2011 343d4163Lula BilloudNo ratings yet

- 201205infectious Disease PDFDocument94 pages201205infectious Disease PDFHaya KhanNo ratings yet

- An Ecological Perspective On Health Promotion ProgramsDocument27 pagesAn Ecological Perspective On Health Promotion ProgramsDaniel MesaNo ratings yet

- Combined ReadingsDocument137 pagesCombined Readingsfaustina lim shu enNo ratings yet

- How Should We Define Health?: BMJ (Online) July 2011Document4 pagesHow Should We Define Health?: BMJ (Online) July 2011DigiferNo ratings yet

- What Makes Health Systems Resilient Against Infectious Disease Outbreaks and Natural Hazards? Results From A Scoping ReviewDocument9 pagesWhat Makes Health Systems Resilient Against Infectious Disease Outbreaks and Natural Hazards? Results From A Scoping ReviewmalatebusNo ratings yet

- Public Health Delivery in The Information Age - The Role of Informatics and TechnologyDocument22 pagesPublic Health Delivery in The Information Age - The Role of Informatics and Technologysbaracaldo2No ratings yet

- Frieden - Health Impact Pyramid PDFDocument6 pagesFrieden - Health Impact Pyramid PDFFernanda PachecoNo ratings yet

- Healthy Trees Make A Healthy WoodDocument2 pagesHealthy Trees Make A Healthy WoodMailey GanNo ratings yet

- Tacking The Wider Determinants of Health InequalityDocument8 pagesTacking The Wider Determinants of Health InequalitymammaofxyzNo ratings yet

- Utilizing Evidence-Based Decision Making in Responding Public Health EmergencyDocument18 pagesUtilizing Evidence-Based Decision Making in Responding Public Health EmergencyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- What Matters Most Quantifying An Epidemiology of ConsequenceDocument7 pagesWhat Matters Most Quantifying An Epidemiology of ConsequenceRicardo SantanaNo ratings yet

- The Global Health System Actors, Norms, andDocument4 pagesThe Global Health System Actors, Norms, andMayra Sánchez CabanillasNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease 2019: Covid-19 Pandemic, States of Confusion and Disorderliness of the Public Health Policy-making ProcessFrom EverandCoronavirus Disease 2019: Covid-19 Pandemic, States of Confusion and Disorderliness of the Public Health Policy-making ProcessNo ratings yet

- Structural Interventions Concepts Challenges and ODocument15 pagesStructural Interventions Concepts Challenges and Oranahimani1310No ratings yet

- Articulo Salud InglesDocument10 pagesArticulo Salud InglesmaryNo ratings yet

- Exploring Indirect Impacts of COBID-19 On Local HCWsDocument12 pagesExploring Indirect Impacts of COBID-19 On Local HCWsDeanne Morris-DeveauxNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Public HealthDocument13 pagesEthics and Public HealthSalman ArshadNo ratings yet

- Callahan PDFDocument8 pagesCallahan PDFvanyywalters1987No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0033350619300368 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0033350619300368 MainmayuribachhavmarchNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Promotion Interventions For Children and Adolescents Using An Ecological FrameworkDocument14 pagesSystematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Health Promotion Interventions For Children and Adolescents Using An Ecological FrameworkFikran Ahmad Ahmad Al-HadiNo ratings yet

- The Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems As The Next Step For Global ProgressDocument4 pagesThe Global Health System: Strengthening National Health Systems As The Next Step For Global Progresslaksono nugrohoNo ratings yet

- Socialdeterminantsof Health:Anoverviewforthe PrimarycareproviderDocument19 pagesSocialdeterminantsof Health:Anoverviewforthe PrimarycareproviderCarlos Hernan Castañeda RuizNo ratings yet

- Monitoring The Implementation of The WHO Global Code of Practice On The International Recruitment of Health Personnel: The Case of IndonesiaDocument63 pagesMonitoring The Implementation of The WHO Global Code of Practice On The International Recruitment of Health Personnel: The Case of IndonesiaFerry EfendiNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology, Health Policy and PlanningDocument18 pagesEpidemiology, Health Policy and PlanningMorgen Pangaila100% (1)

- Implications of Health Dynamic On The EconomyDocument6 pagesImplications of Health Dynamic On The EconomyYagyansh KapoorNo ratings yet

- Bibliography About The Effectiveness of COVID-19 Preventive Measures in Luzon, PhilippinesDocument5 pagesBibliography About The Effectiveness of COVID-19 Preventive Measures in Luzon, PhilippinesIVAN LUIS MARTINEZNo ratings yet

- 2015 Article 54Document3 pages2015 Article 54Damin FyeNo ratings yet

- Managment Process - Sahira JastaniyhDocument10 pagesManagment Process - Sahira Jastaniyhsahira.jas96No ratings yet

- Mae Shiro 2010Document9 pagesMae Shiro 2010timtimNo ratings yet

- Claar Sbu 333 Assignment 8Document7 pagesClaar Sbu 333 Assignment 8api-607585906No ratings yet

- Fpubh 10 1053932Document15 pagesFpubh 10 1053932MelinMelianaNo ratings yet

- Health - System - Quality - SDG PDFDocument4 pagesHealth - System - Quality - SDG PDFDumitru BiniucNo ratings yet

- Concept of Population Health (2005)Document10 pagesConcept of Population Health (2005)ransackmooseNo ratings yet

- A Framework For The Evidence Base To Support Health Impact AssessmentDocument7 pagesA Framework For The Evidence Base To Support Health Impact Assessmentujangketul62No ratings yet

- BMJ m4074 FullDocument4 pagesBMJ m4074 FullRebeca Olmedo AntolínNo ratings yet

- Socsci 05 00002 PDFDocument17 pagesSocsci 05 00002 PDFBinod KhatiwadaNo ratings yet

- SAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inDocument21 pagesSAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inascarolineeNo ratings yet

- Health System Quality and COVID-19 Vaccination. A Cross-Sectional Analysis in 14 CountriesDocument10 pagesHealth System Quality and COVID-19 Vaccination. A Cross-Sectional Analysis in 14 Countriesluis sanchezNo ratings yet

- Oliver 2006Document41 pagesOliver 2006ariniNo ratings yet

- Global Health Architecture Hoffman Cole PearceyDocument42 pagesGlobal Health Architecture Hoffman Cole PearceysanjnuNo ratings yet

- CP - Building Resilient Health Systems A Propos1Document9 pagesCP - Building Resilient Health Systems A Propos1Claudia CortesNo ratings yet

- The Medicalization of Human Conditions and Health Care A Public Health PerspectiveDocument2 pagesThe Medicalization of Human Conditions and Health Care A Public Health PerspectiveKrisna Meidiyantoro100% (1)

- Oliver (2006) Politics of PolicyDocument41 pagesOliver (2006) Politics of PolicyJuan Pablo MoralesNo ratings yet

- How Should We Define Health?: BMJ Clinical Research July 2011Document4 pagesHow Should We Define Health?: BMJ Clinical Research July 2011Rej HaanNo ratings yet

- Guest Editorial: From Theory To Action: Applying Social Determinants of Health To Public Health PracticeDocument4 pagesGuest Editorial: From Theory To Action: Applying Social Determinants of Health To Public Health PracticeSarvat KazmiNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Sophie WitterDocument8 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Sophie WitterAswarNo ratings yet

- How Should We Define Health?: BMJ Clinical Research July 2011Document4 pagesHow Should We Define Health?: BMJ Clinical Research July 2011AbysekaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KedokteranDocument18 pagesJurnal KedokteranelvandryNo ratings yet

- Puac 022Document14 pagesPuac 022Merve Sibel GungorenNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Relationships Between Health Literacy, Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Self-Management in Adults With Multiple Chronic DiseasesDocument10 pagesExploring The Relationships Between Health Literacy, Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Self-Management in Adults With Multiple Chronic Diseasesfriestwister3No ratings yet

- A Systematic Review On Professional Regulation andDocument24 pagesA Systematic Review On Professional Regulation andPaula FrancineideNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0168851020303171 MainDocument12 pages1 s2.0 S0168851020303171 MaindestiaNo ratings yet

- Citizens and Health Care: Participation and Planning for Social ChangeFrom EverandCitizens and Health Care: Participation and Planning for Social ChangeNo ratings yet

- Gha 9 29329Document19 pagesGha 9 29329Bahtiar AfandiNo ratings yet

- Oliver 2006Document41 pagesOliver 2006barkat cikomNo ratings yet

- ABEL Critical Health Literacy in Pandemics: The Special Case of COVID-19Document9 pagesABEL Critical Health Literacy in Pandemics: The Special Case of COVID-19kelseyNo ratings yet

- Critique: Economics & Ethics of The COVID-19 Vaccine: How Prepared Are We?Document3 pagesCritique: Economics & Ethics of The COVID-19 Vaccine: How Prepared Are We?fareha riazNo ratings yet

- A Problem Fro Skin PandemicDocument14 pagesA Problem Fro Skin PandemicAbdi SiregarNo ratings yet

- Willingness and Eligibility To Donate Blood Under 12-Month and 3-Month Deferral Policies Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men in Ontario, CanadaDocument16 pagesWillingness and Eligibility To Donate Blood Under 12-Month and 3-Month Deferral Policies Among Gay, Bisexual, and Other Men Who Have Sex With Men in Ontario, CanadaAbdi SiregarNo ratings yet

- Why We Thik About Desease We Cant AvoidDocument26 pagesWhy We Thik About Desease We Cant AvoidAbdi SiregarNo ratings yet

- A Multi-Country Qualitative Study To Increase The Representation of Women in Global Health LeadershipDocument18 pagesA Multi-Country Qualitative Study To Increase The Representation of Women in Global Health LeadershipAbdi SiregarNo ratings yet

- Independence Day Speech 2023Document2 pagesIndependence Day Speech 2023Abdi SiregarNo ratings yet

- Romualdez-Marcos v. COMELECDocument2 pagesRomualdez-Marcos v. COMELECLawiswis67% (3)

- Collector of Customs vs. Torres Gr. No. L-22977, May 31, 1972Document11 pagesCollector of Customs vs. Torres Gr. No. L-22977, May 31, 1972Ron LaurelNo ratings yet

- Educational Language Policy in Spain and Its Complex Social ImplicationsDocument4 pagesEducational Language Policy in Spain and Its Complex Social ImplicationsIjahss JournalNo ratings yet

- JOEB M Aliviado Vs PDocument5 pagesJOEB M Aliviado Vs PbubblingbrookNo ratings yet

- BC Law 12 - Chapter 1 Notes "All About Law"Document1 pageBC Law 12 - Chapter 1 Notes "All About Law"Jordan ChiuNo ratings yet

- A Crime by Any Other NameDocument2 pagesA Crime by Any Other NameDorel CurtescuNo ratings yet

- G 20 July TopicsDocument5 pagesG 20 July TopicsSynergy BhavaniNo ratings yet

- Procurement Manual For LGUS - Procurement System & OrganizationsDocument72 pagesProcurement Manual For LGUS - Procurement System & OrganizationsjejemonchNo ratings yet

- Revised Rules of Evidence 2019Document33 pagesRevised Rules of Evidence 2019Michael James Madrid Malingin100% (1)

- Fred W Powell - The Politics of Social Work (Sage Politics Texts) (2001)Document193 pagesFred W Powell - The Politics of Social Work (Sage Politics Texts) (2001)Anonymous 8asfqEDWf100% (1)

- Tudor V Board of EducationDocument2 pagesTudor V Board of EducationThea BarteNo ratings yet

- Bangsamoro Organic LawDocument34 pagesBangsamoro Organic LawGle CieNo ratings yet

- Gandhi and Mass MobilisationDocument2 pagesGandhi and Mass MobilisationYoshi XinghNo ratings yet

- The Birth Certificate Discussion - Part 1 by Anna Von ReitzDocument1 pageThe Birth Certificate Discussion - Part 1 by Anna Von ReitzNadah850% (6)

- TV Broad ScriptDocument2 pagesTV Broad Scriptjohnlourence cabilinNo ratings yet

- Fifteenth Congress of The Federation of OSEA Thirteenth MeetDocument4 pagesFifteenth Congress of The Federation of OSEA Thirteenth MeetKaylee SteinNo ratings yet

- Free SpeechDocument9 pagesFree SpeechChristopher Jan DotimasNo ratings yet

- Safe Streets Alliance Et. Al. v. John Hickenlooper Et. Al.Document90 pagesSafe Streets Alliance Et. Al. v. John Hickenlooper Et. Al.Michael_Lee_RobertsNo ratings yet

- The Use and Abuse of The Holocaust: Historiography and Politics in MoldovaDocument25 pagesThe Use and Abuse of The Holocaust: Historiography and Politics in Moldovai CristianNo ratings yet

- INTERNATIONAL LAW NotesDocument8 pagesINTERNATIONAL LAW NotesDipansha GargNo ratings yet

- Pichay, Jr. v. SandiganbayanDocument3 pagesPichay, Jr. v. SandiganbayanHanna Bulacan100% (1)

- Media Law FDDocument17 pagesMedia Law FDNiharika BhatiNo ratings yet

- 19 - PCFDocument2 pages19 - PCFMateo TVNo ratings yet

- Salcedo vs. SandiganbayanDocument3 pagesSalcedo vs. Sandiganbayanlinlin_17No ratings yet

- A Book Review On Rudy Rodil's The Minorization of The Indigenous Communities of Mindanao and The Sulu ArchipelagoDocument6 pagesA Book Review On Rudy Rodil's The Minorization of The Indigenous Communities of Mindanao and The Sulu ArchipelagoShane NakhuiNo ratings yet

- 10 Manufacturers Hanover Trust Vs GuerreroDocument157 pages10 Manufacturers Hanover Trust Vs GuerreroChara GalaNo ratings yet

- Revocation and Reduction of DonationsDocument5 pagesRevocation and Reduction of DonationsFhem WagisNo ratings yet

- Case Digest Legaspi Vs - Sec of FinanceDocument2 pagesCase Digest Legaspi Vs - Sec of FinanceVivian BNNo ratings yet

- What Is The Golden Hour in A Murder Investigation?Document3 pagesWhat Is The Golden Hour in A Murder Investigation?Batara J Carpo AtoyNo ratings yet

- Philippine Politics and Governance: Quarter 2 - Module 10: Elections and Political Parties in The PhilippinesDocument28 pagesPhilippine Politics and Governance: Quarter 2 - Module 10: Elections and Political Parties in The PhilippinesAlexis kaye HingabayNo ratings yet