Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Roach2004 - Evaluating School Climate and School Culture Andrew T. Roach - Thomas R. Kratochw

Uploaded by

Alice ChenOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Roach2004 - Evaluating School Climate and School Culture Andrew T. Roach - Thomas R. Kratochw

Uploaded by

Alice ChenCopyright:

Available Formats

Evaluating School

Climate and School

Culture

Andrew T. Roach • Thomas R. Kratochwill

When do trends in student behavior vention efforts. Ecological models have can enhance or restructure to better

demand schoolwide policies and plans? been proposed for the provision of edu- meet students' needs (Lehr &

How can we examine the school envi- cational services that embrace this sys- Christenson, 2002).

TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 10-17. Copyright 2004 CEC.

ronment to see what positive changes temic focus (e.g., Sheridan & Gutkin, Although researchers in school psy-

we can make to a school's climate or 2000). Within an ecological framework, chology and special education have cre-

culture? What tools are best suited to students' behavioral difficulties demand ated measures of classroom environ-

assessing how students and teachers an awareness of contextual variables ment and interaction, researchers have

view their school's climate or context (e.g., learning environment, community generally given less attention to meas-

for learning? This article takes a histori- resources, and home context), as well ures of school context. This is unfortu-

cal approach to evaluating school cli- as students' intra-individual characteris- nate because classrooms, nested within

mate and offers practical guidance to tics. schools, have climates that are directly

modern measures of school culture. In their attempts to remediate and or indirectly influenced by wider school

treat students' social-emotional and contexts (Anderson, 1982). By under-

Systemic School Improvement to behavioral difficulties, practitioners are standing and evaluating characteristics

Meet Changing Student Needs confronted with many extraneous fac- of the larger school context, educators

To meet the needs of increasingly tors that are difficult to address or recti- can become aware of the following:

diverse student populations and the fy (e.g., families' socioeconomic stand- • Schoolwide protective or risk factors

challenges of accountability-driven edu- ing, community safety and crime, and that may influence intervention out-

cation systems, many mental health and individual students' predisposition to comes.

education professionals have attempted disability and mental illness). School • Resources within the larger school

to broaden the scope of their practice to and classroom contexts, however, are community to address students'

include systemic prevention and inter- factors that educators and communities needs.

10 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

• Pervasive trends in student or staff concerning the construct of school cli-

behavior and attitudes that demand mate. This review process led to the cre- Most school climate

systemic intervention efforts. ation of an extensive model of the com-

The data that researchers have col- ponents of school environments, which measures are survey

lected in effectiveness studies of school- subsequently formed the foundation for instruments

wide behavior interventions have development of the Comprehensive

included the number and kinds of disci- Assessment of School Environ completed by

pline referrals, school demographic ments–Information Manage- teachers, students,

information, school vandalism costs, ment System (CASE-IMS):

and behavioral observations in class- • Instruments for assessing 34 input, and school

rooms (Sprague et al., 2001). Certainly, mediating, and output variables of a administrators.

these data are essential for demonstrat- school environment.

ing the effectiveness of a school's imple- • Computer software for scoring

mentation effort, but they may not pro- response sheets and for interpreting

Evidence of the reliability of the

vide a complete picture of the changes data.

School Climate Survey is adequate:

required and produced by schoolwide • Procedures for predicting the effect of

Internal consistency coefficients for the

behavioral interventions. alternative paths of action on school

surveys range from .63 to.92 and test-

Fullan and Steigelbauer (1991) sug- outcomes.

retest coefficients range from .63 to .92.

gested that educators need to attend to • Suggested interventions for positively

Unfortunately, the technical manual

"the phenomenology of change—that affecting selected variables.

provides no criterion-related evidence

is, how people actually experience • A step-by-step process for translating

for the validity of the CASE School

change" (p. 4). The school climate and assessment information into signifi-

Climate Survey. Moreover, no evidence

school culture measures described in cant school improvement projects

shows that the School Climate Scale dif-

this article are vehicles for achieving (Howard & Keefe, 1991, p. vii).

ferentiates between different school

this goal, providing policymakers and The CASE School Climate Survey

environments or reflects improvements

practitioners with methods to collect represents only one mediating variable

in climate brought about by interven-

information on stakeholders' perspec- within the larger CASE-IMS evaluation

tion efforts (Allen, 1992; Leong, 1992).

tives and "sense-making" regarding framework.

The CASE-IMS represents a promis-

The CASE School Climate Survey

schoolwide behavior interventions ing method for measuring a variety of

consists of 55 items and is administered

(Spillane et al., 2002; see box, components that contribute to school

to students (Grades 6 -12), teachers, and

“Theoretical Foundations for Evaluating effectiveness. Within the context of this

School Context.”) system, inferences made from results on

the CASE School Climate Surveys could

School Climate Instruments provide important information for

Most school climate measures are sur- school reform efforts. Until additional

vey instruments completed by teachers, evidence of construct and consequential

students, and school administrators. validity is available, however, you

The Comprehensive Assessment of should interpret CASE results with cau-

School Environments (CASE; National tion.

Association of Secondary School

Principals, 1986), the Organization Organization Health Inventory

(OHI) and Organizational Climate

Health Inventory (OHI; Hoy & Sabo,

Descriptive Questionnaire (OCDQ)

1998; Hoy et al., 1991), and the

parents to assess their perceptions Developed by Hoy and his colleagues,

Organizational Climate Descriptive

about 10 dimensions of school climate. the OHI and OCDQ have several techni-

Questionnaire (OCDQ; Hoy & Sabo,

You can administer the School Climate cal and practical features that enhance

1998; Hoy et al., 1991) are three school

Survey alone or as part of the larger their appeal for educators and program

climate instruments available to practi-

CASE evaluation package that includes evaluators. For example, both the OHI

tioners.

three components: and the OCDQ have separate instru-

The Comprehensive Assessment of • Satisfaction Surveys administered to ments for use in elementary, middle,

School Environments (CASE) parents, teachers, and students. and high schools. Although the instru-

The CASE is a product of the Task Force • Teacher Report Forms for collecting ments for each age group contain many

on School Climate, convened by the information about teachers' percep- of the same items and scales, they also

National Association of Secondary tions of school and district leadership. have features that reflect the differences

School Principals (NASSP) in 1982. Task • Student Report Forms for collecting between school environments and

information about students' academic organizations at the different grade lev-

force members conducted an extensive

self-concepts. els.

review of research and instrumentation

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ SEPT/OCT 2004 ■ 11

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

Theoretical Foundations for Evaluating School Context

In his seminal work, Brofenbrenner (1979) provided the fol- tially adaptations of individual personality theory (Hoy &

lowing definition of the ecological orientation: Sabo, 1998). Current measures of school climate grew out

The ecology of human development involves the sci- of a body of research on organizational climates in indus-

entific study of the progressive, mutual accommoda- try and university contexts. Early work by March and

tion between an active, growing human being and the Simon (1958) and Argyris (1964) focused on the charac-

changing properties of the immediate settings in teristics of business organizations that influenced employ-

which the developing person lives, as this process is ee morale, productivity, and commitment (Anderson,

affected by the relations between these settings, and 1982). Stern's (1964) research in university settings con-

by the larger contexts in which the settings are cerning "press" (i.e., students' perceptions of environmen-

embedded. (p. 21) tal pressures on students exerted by a given school) sug-

Using Apter and Conoley's (1984) framework, Sheridan gested: (a) students' collective perceptions of school cli-

and Gutkin (2000) modified the pivotal assumptions of eco- mate do reflect objective reality; (b) students' individual

logical theory to address students within the contexts of class- perceptions of school climate are not merely reflections of

rooms, schools, and communities. their personal characteristics; and (c) students' descrip-

tions of the school climate can be separated from their atti-

Assumption 1: Each student is an inseparable part of a small tudes (Anderson, 1982).

social system.

Assumption 2: Disturbance is not viewed as a disease located Thus, school climate can be defined as the pervasive qual-

within the body of the student but, rather, as ity of a school environment experienced by students and

discordance (a lack of balance) in the system. staff, which affects their behaviors (Hoy & Sabo, 1998).

Assumption 3: Discordance may be defined as a disparity According to Haynes, Emmons, and Ben-Avie (1997), school

between an individual's abilities and the climate refers to "the quality and consistency of interperson-

demands or expectations of the environ- al interactions within the school community that influences

ment—-"failure to match" between child and children's cognitive, social, and psychological development"

system. (p. 322).

Assumption 4: The goal of any intervention is to make the To gather information on the "personality" of schools,

system work. (p. 489) measures of school climate tend to focus on individuals'

behaviors and their perceptions of the patterns of communi-

If we embrace these assumptions, then the need for tech- cation and interactions within the school context.

niques to measure and evaluate school context becomes

apparent. Clearly, educators cannot "make the system work" • Definitions of School Culture. Reflecting the diversity of def-

without examining the influence of the school context on a initions for the term in the anthropological literature, defi-

particular student, the student's teachers, and his or her nitions of school culture vary. (According to Berger, 1995,

classmates. p. 136, "It has been estimated that anthropologists have

advanced more than 100 definitions of culture.") Research

Contrasting Constructs: Climate Versus Culture on organizational culture dates back to studies of business

Comprehensive reviews of school climate measures and industry in the 1930s and 1940s. Barnard (1938) and

(Anderson, 1982; Lehr & Christenson, 2002) have addressed Mayo (1945) originally conceptualized workplace culture

constructs and models used in school context research. The as the "norms, sentiments, values, and emergent interac-

differences between the terms setting, atmosphere, environ- tions" of an organization. School culture can be defined as

ment, culture, and climate are both subtle and important. "the way we do things around here" and consists of the

Creating a positive school context, however, is often a pri- organization's shared beliefs, rituals, and ceremonies, and

mary objective of school reform and restructuring efforts patterns of communication (Deal & Kennedy, 1982).

(e.g., Positive Behavior Support or the Yale Child Study

Center School Development Program). School culture represents the underlying assumptions and

A survey of the school context research suggests that cli- beliefs developed through earlier problem solutions, which

mate and culture are the generally preferred constructs for help to define reality within an organization (Angelides &

researchers' investigations of school context. Ainscow, 2000). In their definition, Hoy, Tarter, and Kottkamp

(1991) attempted to synthesize the various definitions of

• Definitions of School Climate. Researchers have often school culture and suggest it is "a system of shared orienta-

described climate as a school's personality; some early tions (norms, core values, and tacit assumptions) held by

conceptualizations of organizational climate were essen- members, which holds the unit together and gives it a distinct

identity" (p. 5). School culture is generally more abstract than

12 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

Theoretical Foundations for Evaluating School Context (continued)

school climate, focusing less on individuals' behavior and duce a "snapshot" of organizational and individual behavior

more on the assumptions, interpretations, and expectations for the expressed purpose of managing and changing that behavior.

that drive individuals' behaviors within the school context. For professionals serving as outside consultants or those

attempting to complete large-scale program evaluations with

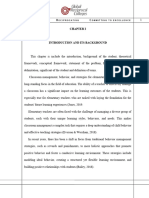

Climate or Culture: Which Construct Is More Meaningful numerous variables, school climate measures are probably

for Evaluating Schoolwide Behavior Interventions? the more reasonable choice. However, when considering

services within a particular school setting, the evaluation

In their review of the research on school climate and school techniques typically used within investigations of school cul-

culture, Hoy and Sabo (1998) indicate their preference for ture may provide more useful data for facilitating change.

using measures of school climate and suggest the following (Figure 1 provides a user-friendly overview of the advantages

advantages: (a) an emphasis on survey technology and sta- and disadvantages of each approach). As with any assess-

tistical analysis; (b) the utility of school climate as an inde- ment, practitioners interested in assessing school context are

pendent variable for explaining student outcomes and staff advised to consider their "referral questions" to facilitate

performance; and (c) school climate measures' ability to pro- selection of an appropriate assessment technology.

The three OHI instruments consist of items contribute to five or six scales that ments, the scales on the OCDQ for sec-

37 to 45 items (depending on the ver- describe teacher and administrator ondary schools do not conform to the

sion) that measure teachers' and admin- behavior. Potential users should note same second-order factor structure as

istrators' perceptions about the organi- the relatively inadequate internal con- those on the versions for elementary

zational health of their school. The sistency for some of the scales on the and middle schools. Therefore, the

items are organized into five to seven middle and secondary school versions Openness Index for secondary schools

distinct scales, each of which demon- of the OCDQ (e.g., Disengaged- can be determined using the standard

strates an acceptable level of reliability Elementary [internal consistency coeffi- scores from four of the five subscales.

(internal consistency coefficients ranged cient = .75]; Committed-Middle School The remaining scale standard score can

from .87 to .95). Administration of the [.60]; Disengaged-Middle [.46]; and be used as an index of Intimacy.

OHI takes about 10 minutes and can be Intimate-Secondary [.71].) Similar to their work with the OHI,

completed by each respondent inde- For the elementary and middle Hoy and colleagues have subsequently

pendently. Moreover, an index of school school versions of the OCDQ, factor used the three versions of the OCDQ in

health can be computed by summing analysis confirmed the existence of a numerous studies that provide con-

the standardized scores for each of the second-order factor structure. For exam- struct- and criterion-related evidence of

individual scales (Hoy & Sabo, 1998). ple, on the OCDQ for middle schools, the OCDQ's validity. Additional studies

Unfortunately, the OHI does not one factor was comprised of measures have examined the contribution of orga-

include instruments for measuring stu- of principal behavior (i.e., Supportive, nizational climate (i.e., openness) to

dents' perceptions of school health. Hoy Directive, and Restrictive), while the overall school achievement. For exam-

and his colleagues, however, have con- other factor consisted of measures of ple, Teacher Openness (r = .52) and

ducted extensive research to provide teacher behavior (i.e., Collegial, Principal Openness (r = .43) Indexes

construct and criterion-related evidence Committed, and Disengaged). The fac- were significantly correlated to a meas-

for the validity of the OHI. Moreover, tor structure was similar for the elemen- ure of academic press (i.e., the amount

some studies have examined the contri- tary version of the OCDQ with the a school stressed academic performance

bution of organizational health to over- Intimate scale replacing the Committed and students respected other students

all school functioning. scale in the factor that describes teacher who were academically successful; Hoy

Similar to the OHI, three separate behavior. These second-order factors et al., 1991).

versions of OCDQ exist to measure contribute to the equation of Principal

teachers' and administrators' percep- Openness and Teacher Openness Evaluating School Culture

tions of school climate at the elemen- Indices. The resulting standard scores Investigators of school culture have typ-

tary, middle, and secondary school lev- for Teacher Openness and Principal ically used ethnographic and participant

els. The questionnaires consist of 34 to Openness, which range from 200 to 800, observation methods to gather informa-

50 items (depending on the version) are used to determine whether the tion about school communities and

that ask respondents to rate the extent school climate is best described as their members. Although qualitative

to which statements (e.g., "Teachers Open, Engaged, Disengaged, or Closed. research methods may not attain the

help and support each other") are true Because of the complex organization reliability and validity of the question-

of behavior in their school. Individual of most secondary school environ- naires used in School Climate Research,

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ SEPT/OCT 2004 ■ 13

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

Figure 1. Evaluating School Context: Advantages and Disadvantages of the Different Approaches

Evaluating School Climate

Comprehensive Assessment of School Environments (CASE)-School Climate Survey

Advantages

• Part of a larger information management system that includes 34 variables regarding school environment

• Computerized software available for scoring and data management.

• Includes student, parent, and teacher surveys.

• Adequate reliability information provided by developers.

Disadvantages

• Only available for secondary schools (Grades 6-12).

• No information on construct and consequential validity provided by developers.

Organization Health Inventory (OHI) and Organizational Climate Descriptive Questionnaire (OCDQ)

Advantages

• Time-efficient administration (i.e., approximately 10 minutes to complete).

• Adequate reliability and validity provided by developers.

• Research conducted by developers suggests the measure is related to school effectiveness.

• Separate measures for elementary, middle, and high schools.

Disadvantages

• Only includes measures of teacher and administrator—Student and parent questionnaires are unavailable.

Evaluating School Culture

Critical Incident Analysis

Advantages

• Provides an opportunity for reflection on the assumptions and beliefs that guide student, teacher, or administrator

behavior.

• Utilizes the skills and knowledge of practitioners with training in conducting classroom observations (e.g., school

psychologists, administrators, and special educators).

Disadvantages

• The definition of a "critical incident" is not well defined.

• The observation and evaluation process has the potential to damage collegial relationships—An outside evaluator

may need to complete the process.

Quality Improvement Tools

Advantages

• Extensive professional literature on the use of Quality Improvement Tools is available.

• Provides a series of techniques for assessing and addressing "value gaps" (e.g., differences between a school's

culture and the goals of the behavior intervention program).

• Process provides opportunities for evaluators to probe stakeholders' responses and for stakeholders to participate

in evaluating the meaning of information produced.

Disadvantages

• Organizing and conducting focus groups can be time consuming.

14 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

interviews and focus groups assess- ical incident. The observer proceeds Angelides and Ainscow (2000) sug-

ments may provide useful information with an analysis, using the following gested that engaging in these reflective

that assists in analyzing school context. "probing questions": discussions could assist school staffs in

Climate questionnaires directly assess • Whose interests are served or denied identifying possible interventions for

descriptions, indirectly assess patterns by the actions of this critical incident? improving their school cultures. They

of relationship among these descrip- • What conditions sustain and preserve caution, however, that presentations of

tions, and do not assess organizational these actions? critical incidents should be both sensi-

members' interpretations of events. • What power relationships between tive and professional in tone to protect

Investigation of school culture focuses principal, teachers, pupils, and par- the feelings and reputations of involved

on assessing the meaning individuals ents are expressed in this incident? parties.

ascribe to interactions and events • What structural, organizational, and Critical Incident Analysis is a poten-

(Rentsch, 1990). cultural factors are likely to prevent tially appealing technique for practition-

Unfortunately, many qualitative teachers and pupils from engaging in ers who have extensive training and

research methods demand extensive alternative ways (Angelides & experience with conducting classroom

observation and participation within the Ainscow, 2000, p. 158)?

observations. Angelides and Ainscow

school context. This level of commit- Whenever possible, participants

(2000), however, recommended that

ment may be unreasonable for many (e.g., teachers and pupils) should be

schools hire an "outside" observer to

practitioners. interviewed about their perceptions and

complete the critical event observations.

Two approaches for data collection explanations of the critical incident.

This approach seems wise because crit-

and analysis may represent less time- Following the interview, the observer

ical incidents have the potential to pres-

intensive methods for evaluating school synthesizes the information from the

ent teachers and their classrooms in a

culture: Critical Incident Analysis and interviewees' multiple perspectives.

less-than-flattering light, leading to

Quality Improvement tools. This information is used to refine the

potentially strained professional rela-

observer's own analysis of the critical

Critical Incident Analysis event. tionships.

The term critical incident was originally Quality Improvement Tools

used by historians to describe turning

Quality Improvement tools represent a

points in the life of a person, an institu-

more appropriate evaluation technique

tion, or social movement (Tripp, 1993).

for practitioners who desire information

Angelides and Ainscow (2000) pro-

about their own school's culture.

posed that by observing and analyzing

Although many practitioners may not be

critical incidents in classrooms, school-

familiar with the Quality Improvement

yards, and teachers' lounges, research-

tools, these procedures are not new. In

ers can "uncover" underlying assump-

fact, their development can be traced

tions and beliefs that guide behavior

back to Deming's work with the

within a school. In a school context,

critical incidents do not need to be mon- Japanese Union of Scientists and

umental or "turning point" events. Engineers (JUSE) in post-World War II

Instead, Angelides and Ainscow (2000) Japan, and followed through the subse-

suggested that critical events can be rel- quent Total Quality Management (TQM)

atively minor incidents—everyday "revolution" in both Japanese and

events that happen in every school and When a collection of critical events American businesses (Brassard, 1996).

in every classroom. Events attain "criti- have been recorded and analyzed, the The application of Quality Improve-

cality" via the justification, the signifi- observer should present his or her find- ment processes to educational decision

cance, and the meaning given to them ings to the school staff and encourage making has been prompted by the need

by participants. Although this definition reflection about the information. The for educators to become more cost effi-

is appealing in its universality, without staff can use the following questions to cient and solution oriented in their eval-

further elaboration the classroom guide this discussion: uation of schools' work environments

observer would be at a loss to separate • What does this account tell us about and cultures. Snyder (1988) defined

critical incidents from everyday occur- ourselves? school culture as "the collective work

rences. Therefore, Angelides and • What can we learn from this analysis? patterns of a system (or school) …as

Ainscow (2000) recommended the fol- • What does this information point to perceived by its staff members"

lowing procedure for identifying and about the nature of the way in which (Johnson, Snyder, Anderson, &

analyzing critical incidents. we work together? Johnson, 1996, p. 140). The Quality

• Does this information help us to see Improvement evaluation process pro-

When something occurs in the class-

things that we could change vides practitioners with tools to exam-

room that surprises or intrigues the

(Angelides & Ainscow, 2000, p. 160)?

observer, it should be recorded as a crit- ine staff members' attitudes and beliefs

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ SEPT/OCT 2004 ■ 15

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

about the school's work patterns and mate's contribution to student behavior

organizational structure. Investigators of and connectedness are areas of interest,

Detert, Louis, and Schroeder (2001) practitioners should use techniques that

offered a series of propositions that school culture have directly assess students' perceptions of

attest to the importance of considering a typically used the school climate.

school's culture during implementation Use multiple methods of assessment.

of the Quality Improvement process. ethnographic and Information about school climate and

School change facilitators need to participant school culture may be more meaningful

address "value gaps" between a reform within the context of data gathered from

program and the underlying school cul- observation methods multiple sources. For example, results

ture. Moreover, school reformers should to gather information from school climate measures can be

deal not only with the aggregate of correlated with student achievement,

stakeholder values in relation to an about school attendance and discipline data, or meas-

existing culture, but also to how indi- communities and ures of teacher satisfaction and sense of

viduals' values align with the dominant efficacy to provide a more meaningful

values of the school community, and their members. picture of school functioning. Observa-

how potential incongruities affect their tions and interviews from school culture

well-being and productiveness (Detert evaluations can be analyzed with

et al., 2001). Therefore, one of the pri- intended to assist the decision-making behavior referrals and other artifacts

mary needs in most school improve- process when selecting a strategy for that provide evidence of the themes and

ment processes is the investigation of evaluating school climate or school cul- issues identified in the examination of

the school culture and its underlying ture. school culture. When evaluating the

values and the design of subsequent Consider the questions that need to be effects of systemic interventions on

interventions to align individuals' val- answered. Within the domain of school school contexts, educators should

ues and needs with those of the change climate, questionnaires are based on dif- attempt to follow the carpenter's rule:

initiative. ferent theories and definitions of organi- "Measure twice, cut once."

Recruiting focus groups that repre- zational climate. Therefore, practition- Consider combining measures of cli-

sent each group of key stakeholders and ers should read user manuals and sup- mate and culture. Information collected

completing a series of the Quality plemental information to make certain from school climate surveys can be

Improvement tools with each group is that survey instruments measure the enriched with interviews and observa-

one method for gathering important constructs of interest. Moreover, survey tions. Surveys and questionnaires are

information about current school cul- respondents, observation subjects, and useful for assessing descriptions of

ture and possible strategies for interven- interview participants should include events, but they do not assess the per-

tion. Unlike school climate question- members of the target group of the eval- sonally relevant meanings attached to

naires, the Quality Improvement uation. For example, if the school cli- events. To understand meaning in

process allows evaluators to schools, it is necessary to

probe participants' responses assess interpretations of stu-

and engage in collectively dents, staff, and other com-

drawing conclusions. A munity members (Rentsch,

potential drawback to using 1990). The combination of

the Quality Improvement quantitative and qualitative

tools is the time commitment methods can provide more

required to recruit and organ- meaningful information

ize representative focus about school contexts to

groups. guide systemic prevention

and intervention efforts,

Final Considerations: resulting in improved out-

Best Practices for comes for students.

Evaluating School

Context

Practitioners interested in References

evaluating school context are Allen, N. L. (1992). Review of the

confronted with a plethora of Comprehensive Assessment of

School Environments. In J. J.

options, including written Kramer & J. C. Conoley (Eds.),

questionnaires, ethnographic The eleventh mental measure-

methods, and focus groups. ments yearbook. Lincoln, NE:

The following guidelines are Buros Institute, University of

16 ■ COUNCIL FOR EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

Nebraska Press. Retrieved April 25, 2002 Leong, F. T. (1992). Review of the

from http://webdbs.library.wisc. Comprehensive Assessment of School

edu:8585/webspirs/start.ws?databases=s( Environments. In J. J. Kramer & J. C.

YB). Conoley (Eds.), The eleventh mental

Anderson, C. S. (1982). The search for school measurements yearbook. Lincoln, NE:

climate: A review of the research. Review Buros Institute - University of Nebraska

of Educational Research, 52, 368-420. Press. Retrieved April 25, 2002 from

Angelides, P., & Ainscow, M. (2000). Making http://webdbs.library.wisc.edu:8585/web

sense of the role of culture in school spirs/start.ws?databases=s(YB).

improvement. School Effectiveness and March, J., & Simon, H. (1958). Organiza-

School Improvement, 11, 145-163. tions. New York: John Wiley.

Apter, S. J., & Conoley, J. C. (1984). Mayo, E. (1945). The social problems of

Childhood behavior disorders and emo- industrial civilization. Boston, MA:

tional disturbance: An introduction to Graduate School of Business

teaching troubled children. Englewood Administration, Harvard University.

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. National Association of Secondary School

Argyris, C. (1964). Integrating the individual Principals. (1986). Comprehensive assess-

and the organization. New York: John ment of school environments (CASE).

Wiley. Reston, VA: Author.

Barnard, C. L. (1938). Functions of the executive. Rentsch, J. R. (1990). Climate and culture:

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Interaction and qualitative differences in

Berger, A. (1995). Cultural criticism. London: organizational meanings. Journal of

Rutledge. Applied Psychology, 75, 668-681.

Brassard, M. (1996). The memory jogger Sheridan, S. M., & Gutkin, T. B. (2000). The

plus: Featuring the seven management

ecology of school psychology: Examining

and planning tools. Salem, NH:

and changing our paradigm for the 21st

GOAL/QPC.

century. School Psychology Review, 29,

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of

485-502.

human development: Experiments in

Snyder, K. J. (1988). School work culture pro-

nature and design. Cambridge, MA:

file. Tampa, FL: School Management

Harvard University Press.

Institute.

Deal, T., & Kennedy, A. (1982). Corporate

Spillane, J. P., Diamond, J. B., Burch, P.,

cultures. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hallett, T., Jita, L., & Zoltners, J. (2002).

Detert, J. R., Louis, K. S., & Schroeder, R. G.

Managing in the middle: School leaders

(2001). A culture framework for educa-

and the enactment of accountability poli-

tion: Defining quality values and their

cy. Educational Policy, 16, 731-762.

impact in U.S. high schools. School

Effectiveness and School Improvement, 12, Sprague, J., Walker, H., Golly, A., White, K.,

183-212. Myers, D., & Shannon, T. (2001).

Fullan, M. G., & Steigelbauer, S. (1991). The Translating research into effective prac-

new meaning of educational change. New tice: The effects of a universal staff and

York: Teachers College Press. student intervention on indicators of dis-

Haynes, N. M., Emmons, C., & Ben-Avie, M. cipline and school safety. Education and

(1997). School climate as a factor in stu- Treatment of Children, 24, 495-511.

dent adjustment and achievement. The Stern, G. G. (1964). B=F(P,E). Journal of

Journal of Educational and Psychological Personality Assessment, 28, 161-168.

Consultation, 8, 321-329. Tripp, D. (1993). Critical incidents in teach-

Howard, E. R., & Keefe, J. W. (1991). The ing. London: Rutledge.

CASE-IMS school improvement process.

Andrew T. Roach (CEC #832), Doctoral

Reston, VA: National Association of

Candidate, School Psychology Program; and

Secondary School Principals.

Hoy, W. K., & Sabo, D. J. (1998). Quality Thomas R. Kratochwill, Professor,

middle schools: Open and healthy. Department of Educational Psychology,

Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Hoy, W. K., Tarter, C. J., & Kottkamp, R. B.

Address all correspondence concerning this

(1991). Open schools/healthy schools:

article to Andrew T. Roach, Wisconsin Center

Measuring organizational climate.

for Education Research, 1025 West Johnson

Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Street, Madison, WI 53706 (e-mail:

Johnson, W. L., Snyder, K. J., Anderson, R.

atroach@wisc.edu)

H., & Johnson, A. M. (1996). School work

culture and productivity. The Journal of We express appreciation to Lois Triemstra

Experimental Education, 64, 139-156. and Katherine Streit for their assistance with

Lehr, C. A., & Christenson, S. L. (2002). Best this manuscript.

practices in promoting a positive school

climate. In A. Thomas & J. Grimes (Eds.), TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 37,

Best practices in school psychology IV (pp. No. 1, pp. 10-17.

929-948). Bethesda, MD: National

Association of School Psychologists. Copyright 2004 CEC.

TEACHING EXCEPTIONAL CHILDREN ■ SEPT/OCT 2004 ■ 17

Downloaded from tcx.sagepub.com at UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN LIBRARY on February 24, 2016

You might also like

- Designing Teaching Strategies: An Applied Behavior Analysis Systems ApproachFrom EverandDesigning Teaching Strategies: An Applied Behavior Analysis Systems ApproachRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- The Influence of Student Teacher Relationship Towards Academic Performance of Senior High School Students.Document51 pagesThe Influence of Student Teacher Relationship Towards Academic Performance of Senior High School Students.Angeline Maquiso SumaoyNo ratings yet

- What Can A WES Evaluation Do For You?: Basic Evaluation Fees (7 Days)Document4 pagesWhat Can A WES Evaluation Do For You?: Basic Evaluation Fees (7 Days)BadshahNo ratings yet

- Ej 1137898Document14 pagesEj 1137898Bianca Nicole MantesNo ratings yet

- Language Management Handout Refugio, MaricrisDocument5 pagesLanguage Management Handout Refugio, MaricrisMaricris RefugioNo ratings yet

- Multisystemic Resilience Adaptation and Transforma... - (Section 3 Education Systems, Arts, and Well-Being)Document21 pagesMultisystemic Resilience Adaptation and Transforma... - (Section 3 Education Systems, Arts, and Well-Being)but thepNo ratings yet

- Chapter III Pre OralDocument9 pagesChapter III Pre OralToni KarlaNo ratings yet

- Culturally Responsive Classroom MGMT Strat2Document10 pagesCulturally Responsive Classroom MGMT Strat2api-300877581No ratings yet

- School Climate & Culture 2-6-16 - 1Document12 pagesSchool Climate & Culture 2-6-16 - 1Rubina SaffieNo ratings yet

- Theory Into Practice: To Cite This Article: J. Randy Mcginnis (2013) Teaching Science To Learners With Special NeedsDocument9 pagesTheory Into Practice: To Cite This Article: J. Randy Mcginnis (2013) Teaching Science To Learners With Special Needsรณกฤต ไชยทองNo ratings yet

- School Climate: Its Impact On Students' Behavior and Academic PerformanceDocument16 pagesSchool Climate: Its Impact On Students' Behavior and Academic PerformancePsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Bridging or Buffering?: The Impact of Schools' Adaptive Strategies On Student AchievementDocument12 pagesBridging or Buffering?: The Impact of Schools' Adaptive Strategies On Student AchievementTushar ChadhaNo ratings yet

- Introduction Chapter 1 3Document1 pageIntroduction Chapter 1 3Glaizel NicolasNo ratings yet

- Imrad 1Document10 pagesImrad 1Glaiza AbrenicaNo ratings yet

- Article 3 - Transactive Curriculum Guide To Adaptati - 230528 - 205511Document9 pagesArticle 3 - Transactive Curriculum Guide To Adaptati - 230528 - 205511Tanzeel SarwarNo ratings yet

- 2016 PE Chilean School FacadesDocument10 pages2016 PE Chilean School FacadesMiriam PriottiNo ratings yet

- Lizzi o 2002Document28 pagesLizzi o 2002MelisawiNo ratings yet

- Assignment 5 Related TopicsDocument4 pagesAssignment 5 Related Topicsapostolmarjorie219No ratings yet

- Assigned Topics For PROFED5 ReportingDocument6 pagesAssigned Topics For PROFED5 ReportingALTOVAR, CASSANDRA MARIELLE LUMBERANo ratings yet

- Intervention in School and ClinicDocument6 pagesIntervention in School and ClinicMuresan VasileNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Social Changes in The School SystemDocument39 pagesSociology of Social Changes in The School SystemMikael Sandino AndreyNo ratings yet

- A Multilevel Study of Predictors of Student Perceptions of School Climate: The Effect of Classroom-Level FactorsDocument9 pagesA Multilevel Study of Predictors of Student Perceptions of School Climate: The Effect of Classroom-Level FactorsPaul AsturbiarisNo ratings yet

- 3487 ArticleText 6553 1 10 202103061Document15 pages3487 ArticleText 6553 1 10 202103061redondojurishNo ratings yet

- BIOLOGIA8Document8 pagesBIOLOGIA8Ana SanchezNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Course Content While Fostering A More Learner Centered EnvironmentDocument5 pagesIncorporating Course Content While Fostering A More Learner Centered EnvironmentLucylle TsuNo ratings yet

- Research in Spec Educ Needs - 2021 - Sider - Inclusive School Leadership Examining The Experiences of Canadian SchoolDocument9 pagesResearch in Spec Educ Needs - 2021 - Sider - Inclusive School Leadership Examining The Experiences of Canadian Schoolcie92No ratings yet

- Inbound 1725399052553827455Document36 pagesInbound 1725399052553827455Crishia AnoosNo ratings yet

- School Climate Indicator PBISDocument9 pagesSchool Climate Indicator PBISCláudia Morais de SáNo ratings yet

- Research Topic Proposal FinalDocument6 pagesResearch Topic Proposal FinalAvegaile PaduaNo ratings yet

- The Organizational Context of Teaching and Learning PDFDocument27 pagesThe Organizational Context of Teaching and Learning PDFDoniekuswandi SaputraNo ratings yet

- Diversity Brief Highres PDFDocument12 pagesDiversity Brief Highres PDFJezreel GrefaldaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - ΟΜΙΛΟΙ ΣΥΝΟΛΙΚΟ2018-2019Document111 pagesMicrosoft Word - ΟΜΙΛΟΙ ΣΥΝΟΛΙΚΟ2018-2019Tina Mantikou100% (1)

- Research Revise Copy of OriginalDocument78 pagesResearch Revise Copy of Originalpincaberyljoan2324No ratings yet

- FRIA - Research Interest - Chapter1Document11 pagesFRIA - Research Interest - Chapter1Francis FriaNo ratings yet

- Rethinking SchoolDocument8 pagesRethinking Schoolriddhi patelNo ratings yet

- PR Final 1-3Document36 pagesPR Final 1-3thaliaozamaNo ratings yet

- "School Dropouts in Malaysia: Impact and Implications" by Assoc. Prof Dr. Samsilah Roslan, UPMDocument30 pages"School Dropouts in Malaysia: Impact and Implications" by Assoc. Prof Dr. Samsilah Roslan, UPMAhmad AmanNo ratings yet

- Kate Practical 2Document38 pagesKate Practical 2Elmar HernandezNo ratings yet

- Mapping The Indigenous Postcolonial Possibilities of Teacher PreparationDocument14 pagesMapping The Indigenous Postcolonial Possibilities of Teacher PreparationC TocciNo ratings yet

- FS 2 EPISODE 2 Coming DoneDocument4 pagesFS 2 EPISODE 2 Coming DoneVdham AcarNo ratings yet

- Forces That Influence Curriculum Design in Malaysian ContextDocument27 pagesForces That Influence Curriculum Design in Malaysian ContextYap Sze Miin0% (1)

- Check If UsefulDocument9 pagesCheck If Usefulrifatzaidi0506No ratings yet

- Connecting The Dots: Key Learning Strategies For Environmental Education, Citizenship, and SustainabilityDocument20 pagesConnecting The Dots: Key Learning Strategies For Environmental Education, Citizenship, and SustainabilityYash VermaNo ratings yet

- Practises and Classroom Management in Inclusive EducationDocument8 pagesPractises and Classroom Management in Inclusive EducationShreya Manjari (B.A. LLB 14)No ratings yet

- Final AssignmentDocument7 pagesFinal AssignmentEdelyn CagasNo ratings yet

- Specialty: Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis NumberDocument6 pagesSpecialty: Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis NumberalpNo ratings yet

- Key Elements of School As A Social System Scene/SituationDocument2 pagesKey Elements of School As A Social System Scene/SituationELJUN AGUDONo ratings yet

- Cbe.13 03 0047Document4 pagesCbe.13 03 0047Adriano AngeloNo ratings yet

- Reopening America:: Strategies For Safer SchoolsDocument16 pagesReopening America:: Strategies For Safer SchoolsMaria Fernanda Buleje GalaNo ratings yet

- CSTP 2 Sullivan 7Document10 pagesCSTP 2 Sullivan 7api-621945476No ratings yet

- Ead 529 Case Study Shaping SchoolcultureDocument5 pagesEad 529 Case Study Shaping Schoolcultureapi-671417127No ratings yet

- Salwa CheylaniDocument10 pagesSalwa CheylaniSalwa CheylaniNo ratings yet

- Social Emotional Learningin Schools The Importanceof Educator CompetenceDocument37 pagesSocial Emotional Learningin Schools The Importanceof Educator CompetenceStephanie FernandesNo ratings yet

- EDU 453 Hidden Curriculum CH 8Document13 pagesEDU 453 Hidden Curriculum CH 8Nor Anisa Musa100% (3)

- CSTP 2 - Semester 4 AssessmentDocument12 pagesCSTP 2 - Semester 4 Assessmentapi-622302174No ratings yet

- Receiving Teachers Teaching Efficacy and Performance in A Secondary SchoolDocument7 pagesReceiving Teachers Teaching Efficacy and Performance in A Secondary SchoolPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Designing ClassroomsDocument9 pagesDesigning ClassroomsPatrícia ValérioNo ratings yet

- Antecedente Internacional. MexicoDocument7 pagesAntecedente Internacional. MexicoKEVIN DAMIAN REYES RODRIGUEZNo ratings yet

- Local Media8674470670761638698Document14 pagesLocal Media8674470670761638698NashNo ratings yet

- VASS Preparing Teachers For CRSDocument12 pagesVASS Preparing Teachers For CRSCelesteNo ratings yet

- National Science Education Standards (1996) : This PDF Is Available atDocument29 pagesNational Science Education Standards (1996) : This PDF Is Available atajifatkhurNo ratings yet

- Prep 003Document2 pagesPrep 003Jim JoseNo ratings yet

- Principals ' Digital Instructional Leadership During The Pandemic: Impact On Teachers ' Intrinsic Motivation and Students ' LearningDocument21 pagesPrincipals ' Digital Instructional Leadership During The Pandemic: Impact On Teachers ' Intrinsic Motivation and Students ' LearningRENIEL MARK BASENo ratings yet

- Lazenby 2016Document12 pagesLazenby 2016Alice ChenNo ratings yet

- Prep 004Document2 pagesPrep 004OtinebOnerec100% (1)

- Prep001 Prepositions PDFDocument2 pagesPrep001 Prepositions PDFEnrique bayo100% (1)

- Effects On Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction - Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job StressDocument16 pagesEffects On Teachers' Self-Efficacy and Job Satisfaction - Teacher Gender, Years of Experience, and Job StressJay GalangNo ratings yet

- To Stay or Not To Stay: Retention of Asian International Faculty in STEM FieldsDocument21 pagesTo Stay or Not To Stay: Retention of Asian International Faculty in STEM FieldsAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Yasser2023 - Principal Support and Teacher Turnover Intention in KuwaitDocument18 pagesYasser2023 - Principal Support and Teacher Turnover Intention in KuwaitAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Teacher Education: Einar M. Skaalvik, Sidsel SkaalvikDocument9 pagesTeaching and Teacher Education: Einar M. Skaalvik, Sidsel SkaalvikAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Tummers LG and Bakker AB (2021) - Leadership and Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Systematic Review.Document13 pagesTummers LG and Bakker AB (2021) - Leadership and Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Systematic Review.Alice ChenNo ratings yet

- LI2023-TeacherTurnoverMetaAnalysisDocument17 pagesLI2023-TeacherTurnoverMetaAnalysisAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument23 pagesUntitledAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Teacher Burnout and Turnover Intention in Higher Education: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and The Moderating Role of Proactive PersonalityDocument17 pagesTeacher Burnout and Turnover Intention in Higher Education: The Mediating Role of Job Satisfaction and The Moderating Role of Proactive PersonalityAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Journal American Educational Research: Turnover? What Are The Effects of Induction and Mentoring On Beginning TeacherDocument35 pagesJournal American Educational Research: Turnover? What Are The Effects of Induction and Mentoring On Beginning TeacherAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Educational Management: Article InformationDocument22 pagesInternational Journal of Educational Management: Article InformationAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Modeling The Nonlinearities Between Coaching Leadership and Turnover Intention by Artificial Neural NetworksDocument12 pagesModeling The Nonlinearities Between Coaching Leadership and Turnover Intention by Artificial Neural NetworksAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Commitment and Self-Efficacy As Predictors of Work Engagement and Well-BeingDocument7 pagesTeachers' Commitment and Self-Efficacy As Predictors of Work Engagement and Well-BeingAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Understanding Media Exposure and post-COVID-19 Travel IntentionsDocument7 pagesA Framework For Understanding Media Exposure and post-COVID-19 Travel IntentionsAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Modeling The Nonlinearities Between Coaching Leadership and Turnover Intention by Artificial Neural NetworksDocument12 pagesModeling The Nonlinearities Between Coaching Leadership and Turnover Intention by Artificial Neural NetworksAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Newly Qualified Teachers' Work Engagement and Teacher Efficacy Influences On Job Satisfaction, Burnout, and The Intention To QuitDocument12 pagesNewly Qualified Teachers' Work Engagement and Teacher Efficacy Influences On Job Satisfaction, Burnout, and The Intention To QuitAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Zhou2022-OrganizationalJusticeTeacherTurnoverIntentionDocument18 pagesZhou2022-OrganizationalJusticeTeacherTurnoverIntentionAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- LI2023-TeacherTurnoverMetaAnalysisDocument17 pagesLI2023-TeacherTurnoverMetaAnalysisAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Tummers LG and Bakker AB (2021) - Leadership and Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Systematic Review.Document13 pagesTummers LG and Bakker AB (2021) - Leadership and Job Demands-Resources Theory: A Systematic Review.Alice ChenNo ratings yet

- Yasser2023 - Principal Support and Teacher Turnover Intention in KuwaitDocument18 pagesYasser2023 - Principal Support and Teacher Turnover Intention in KuwaitAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Zhou2022-OrganizationalJusticeTeacherTurnoverIntentionDocument18 pagesZhou2022-OrganizationalJusticeTeacherTurnoverIntentionAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Leong Sok Yee2021 - Recruitment Criteria For Teachers' Retention in Malaysian International Schools: A Concept PaperDocument9 pagesLeong Sok Yee2021 - Recruitment Criteria For Teachers' Retention in Malaysian International Schools: A Concept PaperAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Hidayati Arshad2015 - Determinants of Turnover Intention Among EmployeesDocument15 pagesHidayati Arshad2015 - Determinants of Turnover Intention Among EmployeesAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Boyd2010 - The Influence of School Administrators On Teacher Retention DecisionsDocument32 pagesBoyd2010 - The Influence of School Administrators On Teacher Retention DecisionsAlice ChenNo ratings yet

- Shifrer2017 - Do Teacher Financial Awards Improve Teacher Retention and Student Achievement in An Urban Disadvantaged School District?Document37 pagesShifrer2017 - Do Teacher Financial Awards Improve Teacher Retention and Student Achievement in An Urban Disadvantaged School District?Alice ChenNo ratings yet

- Teejiesheng2019 - The Cause of Teacher Turnover Intention in JB Private PreschoolDocument56 pagesTeejiesheng2019 - The Cause of Teacher Turnover Intention in JB Private PreschoolAlice Chen100% (1)

- Application Form 2020-21Document2 pagesApplication Form 2020-21aqsa soomroNo ratings yet

- National Policy On Education (NEP 2020) - UPSC NotesDocument5 pagesNational Policy On Education (NEP 2020) - UPSC NotessrinadhNo ratings yet

- Syllabus NWU - ACA - 010: Laoag CityDocument12 pagesSyllabus NWU - ACA - 010: Laoag CityLombroso's followerNo ratings yet

- EDTCOL Module or Handouts 4Document61 pagesEDTCOL Module or Handouts 4Cesar Verden AbellarNo ratings yet

- The Enp Board Review SeriesDocument16 pagesThe Enp Board Review SeriesArthur MericoNo ratings yet

- 7.09 Training Tcgg41 DGR Cabin CrewDocument2 pages7.09 Training Tcgg41 DGR Cabin CrewSHERIEFNo ratings yet

- Sir Mohamed Yusuf Seamen Welfare Foundation Training Ship Rahaman Entrance Exam Exam Admit CardDocument1 pageSir Mohamed Yusuf Seamen Welfare Foundation Training Ship Rahaman Entrance Exam Exam Admit CardSadik YtNo ratings yet

- Application Form: Professional Regulation CommissionDocument1 pageApplication Form: Professional Regulation CommissionREY ANTHONY MIGUELNo ratings yet

- DBA BrochureDocument16 pagesDBA BrochureMarcelguilaNo ratings yet

- TPG-AC7114 - Audit Criteria For Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Suppliers Accreditation ProgramDocument37 pagesTPG-AC7114 - Audit Criteria For Nondestructive Testing (NDT) Suppliers Accreditation ProgramNayan VyasNo ratings yet

- Practical Research 3Document146 pagesPractical Research 3James NanoNo ratings yet

- Admission Policy - NFAT-2023Document37 pagesAdmission Policy - NFAT-2023Rishabh YadavNo ratings yet

- MAT 1033 Syllabus On-Line 91928Document2 pagesMAT 1033 Syllabus On-Line 91928John SchumerNo ratings yet

- Different Methods of Multiple-Choice Test: Implications and Design For Further ResearchDocument7 pagesDifferent Methods of Multiple-Choice Test: Implications and Design For Further Researchrohita kumar dahNo ratings yet

- Sales and DistributionDocument7 pagesSales and DistributionZANJAT SHIVAM ANILRAONo ratings yet

- Statutes-And-Regulations SZABMU EXAMDocument49 pagesStatutes-And-Regulations SZABMU EXAMSyedHammadAhmadNo ratings yet

- Admission Methodology 2024Document6 pagesAdmission Methodology 2024codrinanicoletabargaoanuNo ratings yet

- UEL-Important Rules and GuidelinesDocument2 pagesUEL-Important Rules and GuidelinesIfeanyi AnanyiNo ratings yet

- Professional Education - Elementary Set B: General InstructionsDocument10 pagesProfessional Education - Elementary Set B: General InstructionsNelson PiojoNo ratings yet

- Markaz Nagar, Karanthur - Calicut: Markaz Oasis College of ManagementDocument4 pagesMarkaz Nagar, Karanthur - Calicut: Markaz Oasis College of ManagementMaster EnglishNo ratings yet

- Assessment in LearningDocument22 pagesAssessment in LearningJhavee Shienallaine Dagsaan Quilab100% (2)

- Rule 138 A Section 5 AmendmentDocument3 pagesRule 138 A Section 5 AmendmentJinnelyn LiNo ratings yet

- Skills Checklist: Pre-Final Period: and HospitalityDocument2 pagesSkills Checklist: Pre-Final Period: and Hospitalityanon_230648432No ratings yet

- AE 9-STATISTICAL TOOLS FinalsDocument2 pagesAE 9-STATISTICAL TOOLS FinalsJohn Mark PalapuzNo ratings yet

- Tos-Teacher-Made-Test-Group-3Document10 pagesTos-Teacher-Made-Test-Group-3Maestro MotovlogNo ratings yet

- Becas de Corea KOICA - Formulario 2Document3 pagesBecas de Corea KOICA - Formulario 2kler MatosNo ratings yet

- Physics Portfolios: Science Teacher (Normal, Ill.) January 2013Document7 pagesPhysics Portfolios: Science Teacher (Normal, Ill.) January 2013Saikat SenguptaNo ratings yet

- BEU, Patna - Results Official Website - .Document2 pagesBEU, Patna - Results Official Website - .Nitish agnarNo ratings yet

- Statistics For Business: Course IntroductionDocument31 pagesStatistics For Business: Course IntroductionYin YinNo ratings yet