Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Globalisation and Social Justice

Uploaded by

Hriidaii ChettriOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Globalisation and Social Justice

Uploaded by

Hriidaii ChettriCopyright:

Available Formats

Kapur Surya Foundation

Globalisation, Social Justice And Marginalised Groups In India

Author(s): VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

Source: World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues , Vol. 19, No. 4 (WINTER

(OCTOBER-DECEMBER) 2015), pp. 60-73

Published by: Kapur Surya Foundation

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/48505247

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Kapur Surya Foundation is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

World Affairs: The Journal of International Issues

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

GLOBALISATION, SOCIAL JUSTICE AND

MARGINALISED GROUPS IN INDIA

Globalisation has led to the opening up of the Indian economy to foreign

direct investment by providing facilities for foreign companies to invest in

different fields of economic activity and removing barriers and obstacles for

the entry of multinational corporations. Supporters of globalisation see it as

an engine of growth and technical advancement. Critics argue that it has

widened the gap between nations, led to the exploitation of resources, the

destruction of the environment and a loss of national sovereignty. In the Indian

context, while globalisation has accelerated the flow and interconnectedness

of capital, goods, information, people and technology, it has also intensified

disconnection, exclusion and marginalisation while creating a new privileged

minority within the disadvantaged section of society. This article shows how

globalisation touches upon issues of well-being and social justice and analyses

its effects on the marginalised to understand rising inequalities in India.

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

INTRODUCTION

T

he term “globalisation” refers to the integration of economies and

societies across countries through the flow of capital, finance, ideas,

information, goods, people, services and technologies. The International

Monetary Fund (World Economic Outlook, Washington DC, May 1997, p45)

defines it as:

60 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

“The growing economic interdependence of countries worldwide through

increasing volume and variety of crossborder transactions in goods and services,

freer international capital flows and the more rapid and widespread diffusion

of technology”.

Jagdish N Bhagwati (In Defence of Globalisation, New Delhi: Oxford University

Press, 2007, p3) sees economic globalisation as:

“The integration of national economies into the international economy

through trade, direct foreign investment (by corporations and multinationals),

short term capital flows, international flows of workers and humanity generally

and flows of technology”.

Globalisation may be interpreted as a natural force that is impossible to direct or

control in the contemporary world scenario. As per Japanese economist Kenichi

Ohmae (“Putting Global Logic First”, Harvard Business Review: The Evolving

Global Economy, Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1995, p12):

“No more than Canute’s soldiers can we oppose the tides of the borderless

world’s ebb and flow of economic activity”.

As a consequence, the room for political initiatives has become limited and

the only option for politics is to adjust to globalisation to benefit from it.

Noam Chomsky (“Corporate Globalisation, Korea and International Affairs”,

Interview with Sun Woo Lee, ZNet: The Spirit of Resistance Lives, 22 February

2006) describes it as the neoliberal form of economic globalisation.

“The strongest proponents of globalisation have always been the left and

the labour movements. ... The strongest advocates of globalisation are the

remarkable and unprecedented global justice movements, which get together

annually in the World Social Forum and by now in regional and local social

forums. In the rigid Western-run doctrinal system, the strongest advocates of

globalisation are called ‘anti-globalisation’. The mechanism for this absurdity

is to give a technical meaning to the term ‘globalisation’—it is used within

the doctrinal system to refer to a very specific form of international economic

integration designed in meticulous detail by a network of closely interconnected

concentrations of power—multinational corporations, financial institutions,

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 61

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

the few powerful states with which they are closely linked and their international

economic institutions (International Monetary Fund, World Bank, World Trade

Organisation, etc). Not surprisingly, this form of ‘globalisation’ is designed to

serve the interests of the designers. The interests of people are largely irrelevant”.

Globalisation has severe implications for the marginalised and poor in the

form of increasing individualism and a growing culture of consumerism as

well as expanding and exploiting material desires, creating identity dislocation

and a collective relative deprivation in a large section of people (Sagar Sharma

and Monica Sharma, “Globalisation, Threatened Identities, Coping and Well-

Being”, Psychological Studies, vol55, no4, October–December 2010, p313). The

issues of globalisation are not confined to the economic field but also deeply

affect the sociocultural sphere. The changes associated with it are important for

understanding the impact on and responses of individuals, communities, cultures

and governments to its consequences (ibid, p314). The changes have a direct

bearing on the well-being of individuals and groups. The uneven distribution

of economic gains that excludes many increases the level of stress, alienation

and feeling of injustice among the majority of vulnerable individuals and

marginalised groups (ibid). According to Zygmunt Bauman (Globalisation: The

Human Consequences, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2000), globalisation has changed

the way people think about the world and themselves. A traditional model of

stable and reliable employment has given way to a new experience of a working

life characterised by the absence of contracts, outsourcing, unstable working

conditions, labour market deregulations as well as social and job insecurity

(Vishal Bhavsar and Dinesh Bugra, “Globalisation: Mental Health and Social

Economic Factors”, Global Social Policy, vol8, December 2008, p380).

Globalisation in India is an amalgam of cultural, economic and social

outcomes resulting from the “opening up” of the Indian economy to the global

market (Ruchira Ganguly and Timothy J Scrase, Globalisation and the Middle

Classes in India: The Social and Cultural Impact of Neoliberal Reform, New York:

Routledge, 2009, p4). The Indian economy experienced major policy changes in

the early 1990s and new economic reforms, popularly known as liberalisation,

privatisation and globalisation (the LPG model), aimed at making the economy

a fast growing and globally competitive one. A series of reforms were undertaken

in the financial, industrial and trade sectors to make the economy more efficient.

Many aver that the policy of economic liberalisation has resulted in a mass of

wealthy middle class people—the principal beneficiaries of the globalisation

62 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

process. While they have benefited from consumption and new opportunities

for education and jobs and are seen an engine of growth, on the other hand

the lives of the marginalised and poor have become more difficult due to rising

prices, increasing debt and competition for jobs. Although opportunities have

undoubtedly increased, they have been accompanied by higher levels of financial

and personal stress (ibid, p3). The process of globalisation is guided by the

principle of neoliberalism, which offers consumers a freedom of choice but at

the cost of liberal values like equality and liberty.

SOCIAL JUSTICE AND MARGINALISED GROUPS

A welfare state guarantees provisions for elementary education, minimum

standards of healthcare, economic security and a civilised life. It attempts

to redress existing economic and social inequalities in society and maintain a

balance of power by ensuring social advancement for the marginalised sections

(Sarbeswar Sahoo, Globalisation and the Politics of the Governed: Redefining

Governance in Liberalised India, Research Paper 184, Department of Sociology,

National University of Singapore, 2007, p5). Social justice is a multidimensional

concept that has been viewed variously by scholars and some define it as:

“The right of the weak, aged, destitute, poor, women, children and other

underprivileged persons” (Maddela Abel, Remade in India: Political Modernisation

in the Indian Context, Hyderabad: Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts of

India University Press, 2006, p246).

It is a social value for providing a stable society and securing the unity of a

country. This article is based on distributive justice and the principle of John

Rawls’s (A Theory of Justice, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1971) theory

of justice based on the “difference principle”, which implies an alternative, more

morally sound scheme for the global economic order then the prevalent one. It

leaves open the possibility of a free market as long as the “least advantaged groups

benefit from it”. According to Rawls (ibid), “circumstances, institutions and

historical traditions” decide which economic systems and social institutions best

serve the realisation of justice. He applies socially institutionalised mechanisms

for redistribution.

The concept of marginality is generally used to analyse cultural, political and

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 63

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

socioeconomic spheres, where disadvantaged and poor people struggle to gain

access to resources and a full participation in social life (Ghana S Gurung and

Michael Kollmair, Marginality: Concepts and their Limitations, Swiss National

Centre of Competence in Research North-South, Zurich, IP6 Working Paper 4,

2005, p10). Marginality may be defined as:

“The temporary state of having been put aside, of living in relative isolation,

at the edge of a system (cultural, economic, political or social) ... when one

excludes certain domains or phenomena from one’s thinking because they do

not correspond to the mainstream philosophy” (“Homepage”, International

Geographical Union, online at http://www.swissgeography.ch).

The marginalised are groups of people that are economically, legally, politically

or socially excluded, ignored or neglected and therefore vulnerable to livelihood

changes (ibid). Marginalisation is a multilayered concept. Sometimes, whole

societies may be marginalised at national or global levels, while classes and

communities may be marginalised from the dominant social order at the local level

(Carolyn Kagan and Mark Burton, “Working with People who are Marginalised

by the Social System: Challenges for Community Psychological Work”, online

at http://www.compsy.org.uk). Thus, marginalisation is a complex, shifting

phenomenon linked to social status.

“Marginalisation denies opportunities and outcomes to those living on the

margins, while enhancing opportunities and outcomes for those at the centre.

Marginalisation combines discrimination and social exclusion. It offends

human dignity and denies human rights, especially the right to live effectively

as equal citizens” (“Globalisation and Marginalisation: Discussion Guide to the

Jesuit Task Force Report”, Sydney, July 2007, online at http://www.sjweb.info).

In India, caste and class prejudices exclude many communities and hinder

their participation in economic and social development. Globalisation too has

promoted development at the cost of equity. It has enhanced the gap between the

“haves” and “have-nots” and furthered marginalisation. It is well known, India is a

multicultural, plural society with many groups and sections based on caste, class,

religion, etc. These groups are heterogeneous in nature, facing diverse problems.

Many are marginalised groups that are not empowered to tackle the challenges of

competing for equality even more than sixty years after independence.

64 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

GLOBALISATION AND THE MARGINALISED IN INDIA

A n important point of analysis is not whether globalisation is anti-poor, but

rather if it is “pro-poor”. Social policies in India are formulated to compensate

for asset inequalities and equity losses in the country. Government intervention

in education, employment, the environment, food security, healthcare and

technology is specifically to ensure that

apart from efficiency gains economic

Social policies in India are

reform measures have a positive impact formulated to compensate

on equity as well (Kalpana C Satija, for asset inequalities and

“Economic Reforms and Social Justice equity losses in the country.

in India”, International Journal of Social Government intervention in

Economics, vol36, no9, p956). While education, employment, the

“equity” is not an explicit goal of

economic reforms, it is a necessity and

environment, food security,

a clear definition of what equity should healthcare and technology is

imply in the Indian context must be specifically to ensure that apart

developed. Globalisation has been from efficiency gains economic

accompanied by a debate on whether reform measures have a positive

it is at the cost of growing inequality or impact on equity as well.

not. Critics of globalisation argue that

it accentuates inequality both within and between countries (Melinda Mills,

“Globalisation and Inequality”, Oxford Journals: European Sociological Review,

vol25, no1, 2009, p1). Some finding shows that there are clear winners and

losers, while others argue that globalisation has disintegrated national inequality

gap borders, prompted economic integration and lifted millions out of poverty

(ibid).

Inequality and the gap between the rich and poor are important issues of the

Indian liberalisation programme. In their work, India: Perspectives on Equitable

Development (New Delhi: Academic Foundation, 2009, p102), S Mahendra Dev

and N Chandrashekhara Rao state:

“Inequality has becomes a crucial factor determining the long-term

sustainability of the reform programme, for at least two major reasons. Firstly,

the impact of growth on poverty alleviation is critically dependent on the level

of initial inequality in a society. Secondly, high levels of inequality are inhibitive

of the development and survival of democratic norms in a society. Inequality

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 65

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

undermines good public policy, by eroding collective decision-making processes

and social institutions critical to a healthy functioning of democracy—the so-

called ‘vanishing’ middle class syndrome”.

India is the world’s largest democracy with a federal setup. Inequalities in the

country have two main dimensions—regional inequality between states and

interpersonal inequality. Globalisation has had an adverse impact on regional

inequality, which has the potential to create political tensions in a society where

regional loyalties have been traditionally powerful. Interpersonal inequality in

the wake of the globalisation process in India has also attracted the attention

of academics and policymakers (DM Nachane, Liberalisation, Globalisation and

the Dynamics of Democracy in India, London School of Economics and Political

Science, Asia Research Centre Working Paper 32, June 2010, p21). Privatisation

in India has often led to the rapid concentration of wealth in the hands of the

elite, high service charges by privatised utilities, employment restructuring and

the erosion of regulatory control, which have all impacted marginalised groups

unfavourably (ibid). Even subsidy policies at times do not achieve their short-

term goals of providing greater resources to the poor, as they are either not

targeted at the poor or are hijacked by the rich. The public distribution system

in which a fixed amount of food grain is given per person and a few essential

commodities are sold at subsidised prices has had a negligible impact on rural

poverty, while the central government alone spends four rupees to distribute

one among the intended beneficiaries (Elias Dinopoulos, Pravin Krishna, Arvind

Panagriya and Kar-yiu Wong (Eds), Trade Globalisation and Poverty, New York:

Routledge, 2008, p24).

India’s success owes more to its democratic institutions and processes and

less to external stimuli provided by globalisation. Its economic growth record has

been fairly impressive so far and the country has been steadily marching forward

since independence. India is among the developing countries that have enjoyed

sustained though slow growth in per capita incomes since 1950. Its economy has

been improving since the adoption of economic reforms and in recent years it has

averaged a rate of nearly six to seven per cent (Gowher Rizvi, “Emergent India:

Globalisation, Democracy and Social Justice”, International Journal, Canadian

International Council, Toronto, vol62, no4, Autumn 2007, p760). According to

a World Bank report (The Economic Times, 30 April 2014), India has displaced

Japan to become the world’s third biggest economy in terms of purchasing power

66 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

parity. However, while its share of goods and services has increased globally and

there is every indication that the growth of the economy will accelerate, India’s

development has been characterised by persistent inequality.

India’s record for dealing with the marginalised and disadvantaged while

substantial is far from satisfactory (Rizvi, ibid). The marginalised groups are

poor, mostly illiterate, the least healthy and secure, malnourished, and without

an effective voice. These groups, especially those that have suffered historic

discrimination, have received less than a fair share of the benefits of development

(ibid). They are predominantly dalit and adivasi (tribal)—the worst affected

marginalised groups. The conditions of both communities are at the bottom of

almost all indicators of the Human Development Index. Modern development

has largely bypassed these politically

Privatisation in India has often

and socially disadvantaged people.

Globalisation too has hurt them— led to the rapid concentration

while it has created opportunities of wealth in the hands of the

for employment in the services elite, high service charges by

sector, particularly in information privatised utilities, employment

technology, financial services and the restructuring and the erosion of

retail sector, most jobs are at the lower

regulatory control, which have

levels of business process outsourcing

(JS Sondhi, “An Analysis of India’s all impacted marginalised groups

Development: Before and After unfavourably.

Globalisation”, Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, vol43, no3, January 2008,

p329). Even internet access is differentiated by education, gender, location

and social class—collectively referred to as the digital divide. Information

and communication technologies play an important role in shaping uneven

development within the economy. In India, the development of the shrinking

world due to “time-space compression” has led to new social divisions between

those who have access to information and communication technologies and

those marginalised from them. There is a wide gap between the opportunities

available to those who speak English and operate computers and the rest of

the population. Such inequities at times result in localised conflicts between the

“haves” and “have-nots”, often reinforced by traditional social divisions based

on caste, region and religion (Surya Deva, “Globalisation and its Impact on the

Realisation of Human Rights: Indian Perspective on a Global Canvas” in C Raj

Kumar and K Chockalingam (Eds), Human Rights, Justice and Constitutional

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 67

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

Empowerment, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2007, pp237–8).

Globalisation gives a premium to people with high levels of education

and entrepreneurial skills who are better equipped to survive and succeed in

a competitive world (Manisha Tripathy Pandey, “Globalisation and Social

Transformation in India: Theorising the Transition”, International Journal of

Sociology and Anthropology, vol3, no8, August 2011, p258). As a consequence,

uneducated workers and the marginalised population benefit less in a more

competitive economy with both public and private players in the market. The

process of globalisation has meant a loss of livelihood to many people in traditional

jobs (ibid). According to Joseph E Stiglitz (Globalisation and its Discontents, New

York: WW Norton, 2002, p4), globalisation has created dual economies and

technological divides in societies. It divides as much as it unites. An integral part

of globalisation is “progressive segregation, separation and exclusion” (Stephen

Vertigans and Philip W Sutton, “Globalisation Theory and Islamic Praxis”,

Global Society, vol16, no1, 2002, p12).

India’s economic reforms lay excessive reliance on foreign investment

not only for industrial development but also for solving the unemployment

problem. While multinational corporations and their associate companies have

made considerable investments in India, they have not generated significant

employment for marginalised groups. According to a 2013 National Sample

Survey of India report (Third Annual Employment and Unemployment Survey

Report 2012–13, Labour Bureau, Government of India, online at http://

labourbureau.nic.in), in terms of unemployment the most affected sections are

the marginalised:

“The unemployment rate at 36 persons out of 1000 persons at an all India level

is lowest in the scheduled tribes category, followed by 44 persons under the

other backward classes category, 45 persons under the scheduled castes category

and 56 persons out of 1000 persons each under the general category”.

India has now moved away from the concept of government towards governance.

In the governance paradigm, in large part reflecting the changed circumstances

resulting from economic liberalisation, technological advances and the rise of

market ideology, governments are moving away from being operational agencies

to regulatory authorities. From the perspective of the poor, the rollback of

government’s operational role in the management of the economy does not

68 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

augur well. Through economic reforms, the government has downsized many

state enterprises and privatised many public sector ones leading to a loss of jobs

for marginalised groups that had reservations under a policy of affirmative action

(Rizvi, ibid, p765). As Rizvi (ibid) adds:

“While it is true that as the economy expands and privatised state enterprises

flourish, new and better paid jobs will be created ... in a knowledge-based

economy, only those who are well-educated, skilled, information-savvy,

English-speaking and internationally connected will be able to take advantage

of the opportunities”.

However, without a commitment to affirmative action, private sector jobs are

unlikely to go to rural, locally educated people, especially the marginalised.

Market liberalisation without an adequate social safety net widens the gap

between the rich and the poor and leads to the possibility of the poor being

further marginalised (Gowher Rizvi, “Benefits of State, Monopolised by the

Powerful”, The Hindu, Chennai, 9 May 2007). Nonetheless, the marginalised in

India remain poor neither due to a paucity of solutions nor a lack of resources but

because they are not empowered to enforce entitlements (Amartya Sen, Poverty

and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation, Oxford: Clarendon Press,

1981, p12).

According to Parthapratim Pal and Jayati Ghosh (Inequality in India: A

Survey of Recent Trends, United Nations Department of Economic and Social

Affairs, Working Paper 45, New York, July 2007, p24):

“The opening up of trade leads to job losses in import competing industries

and increases employment opportunities in export sectors. If socioeconomic

conditions prevent workers from making this transition smoothly or if the rate

of new job creation is not fast enough, then it may result in even higher levels

of inequality than those that already prevail in the Indian economy”.

The process of globalisation has adversely affected marginalised groups as they

lack requisite skills, access to technology, institutional credit, are dependent on

agriculture, unemployed, uneducated and unhealthy (ibid). Global experience

shows that those who do not have assets, are not educated, are wage earners and

unskilled have been the losers in the process of globalisation—by and large, as

a fallout of globalisation, the poor have been the losers (Sondhi, ibid, p327).

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 69

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

In India as well, the gap between the rich and the poor has widened and those

without requisite skills have been the losers. Post-globalisation there was much

churning amongst those below the poverty line. Although some have been pulled

out of poverty and enriched, others have been pushed into impoverishment

(ibid, p328).

The Indian caste system is structured and defined by principles of graded

inequality and as such produces economic disparities across caste groups. The

most deprived are the scheduled castes (scheduled refers to the government

schedule in which they are originally listed as eligible for affirmative action

benefits) also known as dalits, literally the oppressed/exploited (Sesha Kethineni

and Gail Diane Humiston, “Dalits, the ‘Oppressed People’ of India: How are

their Social, Economic and Human Rights Addressed”, War Crimes, Genocide

and Crimes against Humanity, vol4, no1, 2010, p100). They still face cultural,

economic, political and social discrimination in the name of caste. Perpetuated

discrimination has resulted in them accounting for a disproportionate number

of the poor in India and in the creation of obstacles that hinder their ability to

change their situation (Ellyn Artis, Chad Doobay and Karen Lyons, Economic,

Social and Cultural Rights for Dalits in India: Case study on Primary Education

in Gujarat, Princeton: Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International

Affairs, 2003, p9). About three-fourths of all dalits live in rural areas, where

the main sources of income are either wage labour in agriculture or non-farm

employment. In urban areas, there is also a big gap between dalits and the

advantaged groups. Moreover, the economic and social inequality of dalits maps

on to regional disparities—there is socioeconomic inequality of dalits versus

other communities and their economic deprivation has persisted over time. The

general process of globalisation and economic development has not reduced the

extent of inequality between dalits and non-dalits.

The Indian National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganised

Sector has introduced categories of the “marginal poor” and “vulnerable”. This

categorisation indicates the position of these groups in the socioeconomic hierarchy.

Table 1 below shows that marginalised groups are heavily underrepresented at

the top and overrepresented at the bottom of the hierarchy (Judith Heyer and

Niraja Gopal Jayal, The Challenge of Positive Discrimination in India, Centre

for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity Working Paper 55,

February 2009, p5).

70 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

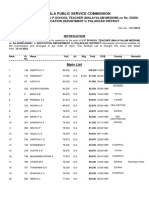

Table 1: Percentages of Major Social Groups by Expenditure Category 2004–05

All Muslims

Scheduled All other except

Castes/ Backward Scheduled

Others All

Scheduled Classes except Castes/

Tribes Muslims Scheduled

Tribes

High: >4 PL* 1.0 2.4 2.2 11.0 4.0

Middle: 2–4 PL 11.1 17.8 13.3 34.2 19.2

Vulnerable:

33.0 39.2 34.8 35.2 36.0

1.25–2 PL

Marginal Poor:

22.5 20.4 22.3 11.1 19.0

1–1.25 PL

Poor: 0.75–1 PL 21.5 15.1 19.2 6.4 15.4

Extremely Poor: <0.75

10.9 5.1 8.2 2.1 6.4

PL

All 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Per cent of Total

27.7 35.9 12.7 23.7 100.0

Proportion

* PL: the official

poverty line in India

Source: Based on National Sample Survey 2004–05 data, cited in Heyer and Jayal, ibid

Although scheduled castes/scheduled tribes are heavily underrepresented at the

top, a small minority are in the upper reaches of the distribution and a few have

reached significant positions in the private sector. Heyer and Jayal (ibid) add:

“The numbers in the ranks just below the top are increasing too. However, if

25 per cent of the total population has benefited from the growth of the Indian

economy in the 1990s and early 2000s, only about half of this proportion of

scheduled castes has done so”.

As per surveys of businesses conducted in 1990 and 1998 by the Centre for

Monitoring the Indian Economy, the total numbers of scheduled caste businesses

declined over the 1990s, a period in which the total number of businesses owned

by all other social groups including scheduled tribes increased (Barbara Harriss-

White and Kaushal Vidyarthee, “An Atlas of Dalits in the Indian Economy”,

unpublished paper, 2007, cited in Heyer and Jayal, ibid, p54). The amount of

public sector credit to scheduled castes also fell in the 1990s, contrary to the case

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 71

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIVEK KUMAR MISHRA

of non-scheduled castes (Pallavi Chavan, “Access to Bank Credit, Implications

for Dalit Rural Households”, Economic and Political Weekly, vol42, no31, 4

August 2007). Such figures support the claim that the declining role of the state

has been more damaging to dalits than to other marginalised groups in India.

While the Constitution of India enumerates separate provisions of

reservations for the economically and socially disadvantaged, there are concerns

about the benefits of quotas confined to dominant groups among scheduled

castes and scheduled tribes and the fact that these benefits tend to be reproduced

inter-generationally. Studies of reservation policies in admissions to the Indian

Institutes of Technology show that many (at times 50 per cent) reserved seats

for scheduled castes and scheduled tribes remain unfilled. In medical colleges,

enrolled scheduled caste students usually come from a few dominant sub-

castes, belong to relatively well-off urban families and have usually attended

private schools (Heyer and Jayal, ibid, p26). Thus, few dalits have benefitted

from affirmative action and globalisation in India. The marginalised have

limited economic opportunities in government jobs, as these are few in number

relative to the numbers of youth joining the workforce. Moreover, millions of

marginalised people obtain degrees without any real skills and quality education.

Thus, the time has come for academicians and leaders in the political process to

give serious thought to the consequences of globalisation for the marginalised in

India. The role of government in establishing the entitlement of the marginalised

has acquired urgency, especially as many of its functions are being rolled back

and the activities it performed in the past have been left to civil society or the

market. Investment in human resources development is essential to help the poor

realise their rights and develop capabilities to take advantage of the opportunities

offered by globalisation.

CONCLUSION

A lthough economic growth is important for any country, it is critical only

to the extent that it helps bring about a qualitative improvement in the

lives of the people—when the benefits of globalisation and development are

actually transferred to all sections of the population. Through the process of

globalisation the dominance of a few powerful people has not been beneficial

for the marginalised in India. Government policies and programmes must

72 WORLD AFFAIRS WINTER 2015 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) VOL 19 NO 4

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

G L O B A L I S AT I O N , S O C I A L J U S T I C E A N D M A RG I N A L I S E D G RO U P S I N I N D I A

be backed by the mobilisation of marginal groups as well as the building and

training of human capacity. Economic growth is a means to an end and not an

end in itself. The end is and must be quality of life and human wellbeing. The

effects of globalisation and the benefits of India’s economic growth have been

unequally distributed and the problems of the marginalised and poor need to

be urgently addressed. The contrasting fates of the rich and poor challenge the

belief in the centrality of government

to society as the custodian of social

The central policy challenge

justice. India’s success is due to its for the Indian government is

democracy and democratic institutions to sustain social gains while

and the processes that have empowered ensuring that the marginalised

a majority of its citizens to realise participate more meaningfully

their capabilities and entitlements in the economy, by sharing in

(Atul Kohli, Democracy and Dissent:

India’s Growing Crisis of Governability,

the fruits of economic growth

Cambridge: Cambridge University and contributing to it as well.

Press, 1990, p17). Amartya Sen has redefined the concept as the expansion of

freedoms, including political freedoms (Pulapre Balakrishnan, “Globalisation

and Development: India since 1991”, The Journal of Economic Asymmetries, vol8,

no2, December 2011, p56). Globalisation could contribute to the project of

development as the expansion of freedoms. India however has yet to achieve

the expansion of positive freedom as envisaged in Sen’s conceptualisation of

development. Politics, political mobilisation, political institutions and policy

frameworks intervene to refract the condition of the marginalised.

The central policy challenge for the Indian government is to sustain social

gains while ensuring that the marginalised participate more meaningfully in the

economy, by sharing in the fruits of economic growth and contributing to it as

well. In an address to the nation, Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed his

intention to “take a solemn pledge of working for ... the welfare of the poor, the

oppressed, the dalits, the exploited and the backward people of the country” (D

Shyam Babu and Chandra Bhan Prasad, “For a New Paradigm of Social Justice”,

The Hindu, New Delhi, 1 September 2014). The precise implementation of this

social justice vision in practice must promote a need based justice on the Rawls

and Sen models.

VOL 19 NO 4 (OCTOBER – DECEMBER) WINTER 2015 WORLD AFFAIRS 73

This content downloaded from

103.59.198.110 on Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:25:46 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Globalization and Increasing Role of BureaucracyDocument7 pagesGlobalization and Increasing Role of BureaucracySambeet SatapathyNo ratings yet

- FR - 30 - Globalization - Opportunities in Industrial Sector in BangladeshDocument19 pagesFR - 30 - Globalization - Opportunities in Industrial Sector in BangladeshRashedul Hasan RashedNo ratings yet

- Course: Introduction To Industrial Social Work (101) : Globalization: Opportunities in Industrial Sector in BangladeshDocument19 pagesCourse: Introduction To Industrial Social Work (101) : Globalization: Opportunities in Industrial Sector in BangladeshRashedul Hasan RashedNo ratings yet

- Module in Gec 3Document169 pagesModule in Gec 3Tam Mi100% (5)

- Contemporary World Lesson 12Document12 pagesContemporary World Lesson 12Zyrelle RuizNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World Module PDFDocument168 pagesContemporary World Module PDFjudi2685No ratings yet

- GlobalisationDocument10 pagesGlobalisationJanvi SinghiNo ratings yet

- Contempo Unit 1Document19 pagesContempo Unit 1PjungNo ratings yet

- Talent Management: A Review of Its Dimensions and Loci in Contemporary TimesDocument5 pagesTalent Management: A Review of Its Dimensions and Loci in Contemporary TimesThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Ge3 - The Contemporary WorldDocument11 pagesGe3 - The Contemporary WorldKein Irian BacuganNo ratings yet

- GiddensDocument1 pageGiddensGillisa VerdunNo ratings yet

- Globalization in 40 CharactersDocument133 pagesGlobalization in 40 CharactersShen Eugenio100% (1)

- Globalization and Education in India: The Issue of Higher EducationDocument5 pagesGlobalization and Education in India: The Issue of Higher EducationUzma SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Manjari Goel_Mid Term PaperDocument12 pagesManjari Goel_Mid Term PaperManjari GoelNo ratings yet

- EEB Assignment: Globalisation and The Developing CountriesDocument8 pagesEEB Assignment: Globalisation and The Developing CountriesDipanita DashNo ratings yet

- Challenges of Globalization For BangladeshDocument11 pagesChallenges of Globalization For Bangladeshziaulh23No ratings yet

- The Contemporary World: Learner'SguideDocument176 pagesThe Contemporary World: Learner'SguideJERWIN SAMSONNo ratings yet

- Contemporary World Module 1Document5 pagesContemporary World Module 1Arnel BoholstNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheet No 1Document8 pagesActivity Sheet No 1Noah Ras LobitañaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 13 TCWDocument33 pagesModule 1 13 TCWCristobal JoverNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Economic Development IDocument7 pagesGlobalization and Economic Development INyarumwe KNo ratings yet

- Forming Connection:: "No Generation Has Had The Opportunity, AsDocument12 pagesForming Connection:: "No Generation Has Had The Opportunity, AsArvie TVNo ratings yet

- Tsoeu KJ 35920580-WVNS211Document5 pagesTsoeu KJ 35920580-WVNS211kamohelo tsoeuNo ratings yet

- GE CW - Module 1Document25 pagesGE CW - Module 1gio rizaladoNo ratings yet

- Globalization A Search For DefinitionDocument16 pagesGlobalization A Search For DefinitionDonald MalenabNo ratings yet

- Globalization (INTRO)Document19 pagesGlobalization (INTRO)Pam RomeroNo ratings yet

- Globalization's Impact on IndiaDocument21 pagesGlobalization's Impact on IndiaLliahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Defining Globalization Without BGDocument11 pagesChapter 1 Defining Globalization Without BGSherelyn LumabaoNo ratings yet

- GlobalizationDocument5 pagesGlobalizationJohn Justine Jay HernandezNo ratings yet

- Who Really Benefits From Tourism? - Working Paper Series 2008-09Document76 pagesWho Really Benefits From Tourism? - Working Paper Series 2008-09Equitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS)No ratings yet

- Contemporary WorldDocument25 pagesContemporary WorldAnne MolinaNo ratings yet

- Force Driving GlobalizationDocument12 pagesForce Driving GlobalizationLuu Ngoc Phuong (FGW HCM)No ratings yet

- Globalization Research PaperDocument19 pagesGlobalization Research PapernehaNo ratings yet

- Globalization DebateDocument18 pagesGlobalization DebateijagraviNo ratings yet

- Globalization in India: The Key Issues : September 2012Document19 pagesGlobalization in India: The Key Issues : September 2012ShashankNo ratings yet

- 2 E Globalization and PakistanDocument9 pages2 E Globalization and PakistanNabeelapakNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi: Pashyantu, Maa Kaschit Dukhabhag Bhavet . The Saints and Seers in Ancient India HadDocument25 pagesMahatma Gandhi: Pashyantu, Maa Kaschit Dukhabhag Bhavet . The Saints and Seers in Ancient India HaddevagnanamNo ratings yet

- It Pi Journal 2009Document9 pagesIt Pi Journal 2009password123resetNo ratings yet

- Lesson2-Theories of GlobalizationDocument36 pagesLesson2-Theories of GlobalizationJembogs JemersNo ratings yet

- GE3 Forum#1Document4 pagesGE3 Forum#1Lalaine EspinaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalization on Indian SocietyDocument10 pagesImpact of Globalization on Indian SocietyShivam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-4 SS 1DDocument8 pagesChapter 1-4 SS 1DDanes Mhikail San JoseNo ratings yet

- Process of Globalisation - NotesDocument5 pagesProcess of Globalisation - NotesSweet tripathiNo ratings yet

- Final Impact of Globalization On EmployementDocument43 pagesFinal Impact of Globalization On EmployementShubhangi GhadgeNo ratings yet

- POLSC 188 | Global Civil Society and Democratizing GlobalizationDocument5 pagesPOLSC 188 | Global Civil Society and Democratizing Globalizationredbutterfly_766No ratings yet

- Globalization and Human Rights: The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries March 2018Document5 pagesGlobalization and Human Rights: The Journal of Infection in Developing Countries March 2018Ofarouk7No ratings yet

- GlobalisationDocument5 pagesGlobalisationiResearchers OnlineNo ratings yet

- FSFSCI-1.9 - GLOBALIZACIÓN-Globalisation-Shalmali GuttalDocument10 pagesFSFSCI-1.9 - GLOBALIZACIÓN-Globalisation-Shalmali GuttalNorman AlburquerqueNo ratings yet

- Global Iast I OnDocument29 pagesGlobal Iast I OnShuen NyinNo ratings yet

- Academic Writing Assigment 1st Attempt of Lit. ReviewDocument6 pagesAcademic Writing Assigment 1st Attempt of Lit. ReviewAhmed EmadNo ratings yet

- Dimension, Theories, Advantages and Disadvantages of GlobalizationDocument25 pagesDimension, Theories, Advantages and Disadvantages of GlobalizationFilipinas YabesNo ratings yet

- Impact of Globalization On The Growth of Economies in Developing CountriesDocument18 pagesImpact of Globalization On The Growth of Economies in Developing Countriesreyad binNo ratings yet

- Impactof Globalizationon AfricaDocument10 pagesImpactof Globalizationon Africayared sitotawNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Study of Globalization: Ge103 - The Contemporary WorldDocument4 pagesIntroduction To The Study of Globalization: Ge103 - The Contemporary Worldmaelyn calindongNo ratings yet

- Human Rights ProjectDocument27 pagesHuman Rights ProjectAnubhutiVarmaNo ratings yet

- The Social Commons: Rethinking Social Justice in Post-Neoliberal SocietiesFrom EverandThe Social Commons: Rethinking Social Justice in Post-Neoliberal SocietiesNo ratings yet

- Building Financial Resilience: Do Credit and Finance Schemes Serve or Impoverish Vulnerable People?From EverandBuilding Financial Resilience: Do Credit and Finance Schemes Serve or Impoverish Vulnerable People?No ratings yet

- May 2014 1400155571 f3d33 41Document2 pagesMay 2014 1400155571 f3d33 41Hriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Mid Term Examinations Sociology Course Instructor: Bhavneet KaurDocument6 pagesMid Term Examinations Sociology Course Instructor: Bhavneet KaurHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Amba Lal V Union of IndiaDocument7 pagesAmba Lal V Union of IndiaHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Mediation Round Problem - 2023Document3 pagesMediation Round Problem - 2023Himanshu MukimNo ratings yet

- Wendy Brown and Janet Halley Critique of Left LegalismDocument37 pagesWendy Brown and Janet Halley Critique of Left Legalismkabir kapoorNo ratings yet

- Critique HandoutDocument1 pageCritique HandoutHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Does Globalisation Shape Income InequalityDocument21 pagesDoes Globalisation Shape Income InequalityHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Globalisation and Climate ChangeDocument32 pagesGlobalisation and Climate ChangeHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Baxi, Rationalist and Hedonist TeachersDocument1 pageBaxi, Rationalist and Hedonist TeachersHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 103.59.198.110 On Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:20:07 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 103.59.198.110 On Mon, 06 Mar 2023 15:20:07 UTCHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- .Stephens - 2018 - The Politics of Muslim Rage Secular Law and Religious Sentiment in Late Colonial India The Politics of Muslim Rage SDocument21 pages.Stephens - 2018 - The Politics of Muslim Rage Secular Law and Religious Sentiment in Late Colonial India The Politics of Muslim Rage SHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Property Law Case Analysis and Problem Solving AssessmentDocument5 pagesProperty Law Case Analysis and Problem Solving AssessmentHriidaii ChettriNo ratings yet

- Sociology B.sc. (N) II YearDocument5 pagesSociology B.sc. (N) II Yearmuthukumar75% (4)

- 14E. Dr. Ambedkar With The Simon Commission E PDFDocument12 pages14E. Dr. Ambedkar With The Simon Commission E PDFVeeramani ManiNo ratings yet

- Decay of Village Community PDFDocument19 pagesDecay of Village Community PDFAbhijeet JhaNo ratings yet

- Women and The Perpetuation of Caste System in NepalDocument9 pagesWomen and The Perpetuation of Caste System in NepaldentsavvyNo ratings yet

- Social Stratification: Caste, Class and RaceDocument41 pagesSocial Stratification: Caste, Class and RacesudhadkNo ratings yet

- Conceptualizing Brahmanical Patriarchy in Early IndiaDocument7 pagesConceptualizing Brahmanical Patriarchy in Early IndiaKiruba MunusamyNo ratings yet

- SelvarajDocument6 pagesSelvarajkamal joshiNo ratings yet

- Show PDFDocument166 pagesShow PDFSantanuNo ratings yet

- Caste INTERVIEW QUESTIONS-Sanjay-Sonawani-finalDocument14 pagesCaste INTERVIEW QUESTIONS-Sanjay-Sonawani-finaldrsunilarrakhNo ratings yet

- Analysis Approach Source Strategy Sociology Mains Paper I Vision Ias V PDFDocument20 pagesAnalysis Approach Source Strategy Sociology Mains Paper I Vision Ias V PDFJagadeesh YVNo ratings yet

- Anthro - Chapter - Wise - Previous - Questions - 2 by PDFDocument14 pagesAnthro - Chapter - Wise - Previous - Questions - 2 by PDFAshish ShekhawatNo ratings yet

- Banaras Essay PDFDocument9 pagesBanaras Essay PDFAtul JainNo ratings yet

- Socio ProjectDocument18 pagesSocio ProjectAakashBhattNo ratings yet

- Guidance for Hindus from their own ScripturesDocument35 pagesGuidance for Hindus from their own Scripturesislamicdawah centerNo ratings yet

- Sample Rbi Social Issues - 230514 - 191216Document26 pagesSample Rbi Social Issues - 230514 - 191216jenyNo ratings yet

- Mithila Art HistoriographyDocument23 pagesMithila Art HistoriographyBilal AhmadNo ratings yet

- Article 15 of The Constitution Contents FinalDocument15 pagesArticle 15 of The Constitution Contents FinalRAUNAK SHUKLANo ratings yet

- The Art of IndiaDocument36 pagesThe Art of IndiaAnalee Regalado LumadayNo ratings yet

- Caste PoliticsDocument3 pagesCaste PoliticsZaheen Nuz ZamanNo ratings yet

- Development Research in BiharDocument483 pagesDevelopment Research in BiharAvishek RanjanNo ratings yet

- CLAT 2019 PG 3rd List - TNNLU Vacant Seats & AllotmentsDocument2 pagesCLAT 2019 PG 3rd List - TNNLU Vacant Seats & AllotmentsPratiyush KumarNo ratings yet

- Annex 51Document19 pagesAnnex 51Bharath KumarNo ratings yet

- Social Stratification Types, Characteristics and ExamplesDocument6 pagesSocial Stratification Types, Characteristics and ExamplesAshfaq KhanNo ratings yet

- Kerala UPS Teacher Ranked ListDocument28 pagesKerala UPS Teacher Ranked ListHusna ahmadNo ratings yet

- 08 Chapter 3Document32 pages08 Chapter 3Maha LakshmiNo ratings yet

- Sociology 3 Module 1-2 Amity UniversityDocument25 pagesSociology 3 Module 1-2 Amity UniversityAnushka SharmaNo ratings yet

- Gotra and Social System in Ancient India: By-Manas NemaDocument7 pagesGotra and Social System in Ancient India: By-Manas NemaManas NemaNo ratings yet

- Satra: Its Impact On Assamese SocietyDocument8 pagesSatra: Its Impact On Assamese SocietyIJASRETNo ratings yet

- Interpreting Untouchability: The Performance of Caste in Andhra Pradesh, South IndiaDocument24 pagesInterpreting Untouchability: The Performance of Caste in Andhra Pradesh, South IndiabhasmakarNo ratings yet

- The Story of My EnglishDocument10 pagesThe Story of My Englishsruthi kavinNo ratings yet