Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Children's Judgements of

Uploaded by

lianna340Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Children's Judgements of

Uploaded by

lianna340Copyright:

Available Formats

Psychology of Music

http://pom.sagepub.com

Children's judgements of emotion in song

J. Bruce Morton and Sandra E. Trehub

Psychology of Music 2007; 35; 629 originally published online Aug 16, 2007;

DOI: 10.1177/0305735607076445

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://pom.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/35/4/629

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Society for Education, Music and Psychology Research

Additional services and information for Psychology of Music can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://pom.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://pom.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations http://pom.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/35/4/629

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

A RT I C L E 629

Children’s judgements of Psychology of Music

Psychology of Music

emotion in song Copyright © 2007

Society for Education, Music

and Psychology Research

vol 35(4): 629‒639 [0305-7356

(200710) 35:4; 629‒639

10.1177⁄0305735607076445

http://pom.sagepub.com

J . B RU C E M O R T O N

U N I V E R S I T Y O F W E S T E R N O N TA R I O , C A N A DA

SANDRA E. TREHUB

U N I V E R S I T Y O F T O RO N T O AT M I S S I S S AU G A , C A N A DA

A B S T R A C T Songs convey emotion by means of expressive performance cues (e.g.

pitch level, tempo, vocal tone) and lyrics. Although children can interpret both

types of cues, it is unclear whether they would focus on performance cues or

salient verbal cues when judging the feelings of a singer. To investigate this

question, we had 5- to 10-year-old children and adults listen to song fragments

that combined emotive performance cues with meaningless syllables or with

lyrics that had emotional implications. In both cases, listeners were asked to

judge the singer’s feelings from the sound of her voice. In the context of

meaningless lyrics, children and adults successfully judged the singer’s feelings

from performance cues. When the lyrics were emotive, adults reliably judged the

singer’s feelings from performance cues, but children based their judgements on

the lyrics. These findings have implications for children’s interpretation of vocal

emotion in general and sung performances in particular.

KEYWORDS: development, music, perception, songs, vocal emotion

Introduction

Songs are important for their role in social and emotional regulation across

age and culture. Infants in all societies are routinely exposed to lullabies or

play songs performed by their caregivers (Trehub and Trainor, 1998).

Preschool and school-age children commonly sing as they play, their invented

playground songs exhibiting similarities across cultures (Kartomi, 1980;

Opie and Opie, 1960). In addition to the emotion regulatory role of songs for

adolescents and adults (Sloboda and O’Neill, 2001), songs also enhance

identity and group solidarity (Pantaleoni, 1985), mark significant rites of

passage (Finnegan, 1977) and provide socially acceptable means of

expressing negative sentiments (Merriam, 1964).

sempre :

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

630 Psychology of Music 35(4)

The most obvious means of conveying basic emotions (e.g. happiness,

sadness) in song is through aspects of performance, including pitch level (e.g.

higher pitch for more joyful purposes), tempo (e.g. faster tempo for happier

renditions) and vocal tone. Song lyrics also contribute to the emotional

interpretation of songs, but the extent to which child and adult listeners

focus on the meaning of sung lyrics as opposed to their form is unclear. For

example, children commonly produce the ABC song before they have any

conception of letters, although the memorized words become useful in sub-

sequent years. Moreover, they readily learn the words of foreign songs (e.g.

‘Frère Jacques’), which, like the songs of their culture, may sacrifice meaning

to meet metrical constraints of the music (Rubin, 1995).

In general, the lyrics and performing style of songs are consistent in

valence, as in the case of ‘You are My Sunshine’. At times, however, grue-

some lyrics occur in the context of cheerful children’s songs (e.g. the three

blind mice who had their tails cut off) or soothing lullabies (e.g. the falling

cradle in ‘Rock-a-bye Baby’). In such cases, the negative text does not disrupt

the mood of the song, which implies that casual singers and listeners do not

pay close attention to the verbal details but rather to the sound effects created

by rhyme, alliteration, assonance or repetition. In other cases, the lyrics are

critical, as when they tell a story (‘There Was an Old Lady who Swallowed a

Fly’) or invite singers or listeners to action (‘If You’re Happy and You Know It,

Clap your Hands’).

Aspects of sung performance are highly salient to listeners from the early

days of life. For example, newborns prefer infant-directed performances of

songs, which are infused with positive emotion, to informal but non-infant-

directed performances of the same song by the same singer (Masataka,

1999). Preschool and school-age children manipulate tempo and pitch level

to produce happy and sad renditions of familiar songs (Adachi and Trehub,

1998), and same-age listeners readily discern the intended emotion (Adachi

and Trehub, 2000).

Prosodic aspects of speech, which are analogous to melodic and expressive

aspects of song, provide cues to a speaker’s feelings, attitudes and communi-

cative intentions (Bolinger, 1989; Frick, 1985). When children are asked to

judge the speaker’s feelings from the sound of their voice, they base their

judgements on the message content (Friend, 2001; Morton and Trehub,

2001). Specifically, they regard the speaker as happy when they talk about

pleasant events and as sad when they talk about unpleasant events, in spite of

obvious prosodic and paralinguistic cues to the opposite feelings. Unlike

adults, who readily set aside salient but irrelevant cues, children have

difficulty altering their characteristic focus on message content to meet the

demands of the task (Morton et al., 2003). Their performance is not

attributable to an inability to label paralinguistic cues to emotion. When the

words are indecipherable (Morton and Trehub, 2001) or emotionally neutral

(Dimitrovsky, 1964; Morton et al., 2003), children successfully identify the

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

Morton and Trehub: Children’s judgements of emotion in song 631

speaker’s feelings from the prosodic and paralinguistic cues, which confirms

their understanding of the emotional implications of those cues.

If expressive vocal features are more salient in songs than in speech, then

children should judge the singer’s feelings on the basis of performing style,

regardless of the lyrics. The possibility remains, however, that children’s

attention would be dominated by events portrayed in the lyrics of songs. If so,

they would judge the singer’s feelings primarily from verbal cues, even when

the performing style conveys very different feelings. The present study is the

first to examine this issue in the context of music. Specifically, we sought to

determine whether children would judge the feelings of a singer (happy or

sad) from the valence of the expressive cues or from the valence of events

depicted in the lyrics.

Children 5–10 years of age and adults listened to song fragments con-

sisting of tunes specially composed for one-sentence descriptions of happy or

sad events (from Morton and Trehub, 2001). For each song sample, listeners

were asked to attend to the singer’s voice and to judge her feelings as happy or

sad. The use of verbal materials from Morton and Trehub (2001) made it

possible to determine whether the singing context eliminated the bias to

verbal emotion cues that children exhibited in the speech context.

The happy performances were sung in the major mode and at a higher

pitch level and faster tempo than the corresponding sad performances, which

were sung in the minor mode. Children in the age range of interest readily

identify the emotional valence of music from pitch, mode and tempo cues

(Adachi and Trehub, 2000; Dalla Bella et al., 2001; Kastner and Crowder,

1990). To confirm listeners’ understanding of the emotional connotations of

these features, a supplementary task was included in which they judged the

singer’s feelings from tunes sung to the repeated syllable ‘da’. As noted, the

overriding goal was to determine whether listeners judged the singer’s

feelings from her performance style or from the lyrics.

Method

PARTICIPANTS

Participants included 25 5- to 6-year-olds (13 boys, 12 girls; M = 6 years, 1

month), 25 7- to 8-year-olds (10 boys, 15 girls; M = 7 years, 9 months), 25

9- to 10-year-olds (12 boys, 13 girls; M = 9 years, 11 months) and 25 adults

(11 men, 14 women; M = 20 years, 6 months). Children were recruited from

the general community and through local schools. Adults were undergrad-

uate students in an introductory psychology class who received partial course

credit. English was the native or dominant language of all participants.

APPARATUS

Testing was conducted individually in a quiet room, either at a university

laboratory (for 5- and 6-year-olds, and adults) or in community schools (for

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

632 Psychology of Music 35(4)

7- to 10-year-olds). Stimuli were presented by means of a Macintosh®

computer and PsyScope software (Cohen et al., 1993) or a PC and E-Prime

software (from Psychology Software Tools, Inc.) and Altec computer speakers.

Responses were entered by means of a two-button response box, one button

labeled with a happy face, the other with a sad face.

Children sat facing the computer monitor and an adult experimenter sat

beside them. The experimenter used the computer keyboard to initiate trials,

and children used the button box to indicate their responses. The computer

randomized the order of stimuli and recorded responses to each stimulus. A

self-administered version of the task was used for adults.

STIMULI

The stimuli consisted of 20 song fragments written specifically for 20

different sentences, 10 describing happy events (e.g. ‘My mommy gave me a

treat’) and 10 describing sad events (e.g. ‘My dog ran away from home’)

adopted from Morton and Trehub (2001) (see appendix).

Each of the 20 tunes was sung once in a happy style (i.e. in the relative

major key with rapid tempo – around 120 b.p.m) and once in a sad style (i.e.

in the relative minor key with slow tempo – around 60 b.p.m), creating a total

of 40 songs, 20 with consistent musical and verbal cues to emotion (e.g.

happy tune, happy melody), 20 with conflicting musical and verbal cues (e.g.

happy tune, sad melody). Five of these tunes were also sung once in a happy

style and once in a sad style to the repeated syllable ‘da’, creating a total of 10

songs with musical cues to emotion but no verbal cues. All songs were

performed by the same musically trained female singer and were digitally

recorded by means of a Radius computer and SoundScope software (GW

Instruments Inc.).

PROCEDURE

The task was self-administered in the case of adults and experimenter-

administered for the children. Listeners were instructed to listen to the sound

of the singer’s voice and to indicate whether she felt happy or sad by pressing

the appropriate button on the button box. After two practice trials with

congruent musical and verbal cues (happy in one case, sad in the other),

listeners proceeded to the test phase, which consisted of the remaining 38

tunes with words presented in random order followed by the 10 tunes sung to

meaningless syllables, also in random order.1 The entire session was

approximately 20 minutes in duration.

Results

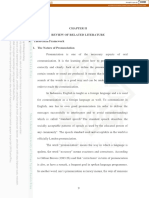

When the verbal and musical cues to emotion were consistent (both happy or

both sad), judgements based on word or musical cues were indistinguishable.

Therefore, the analysis focused on judgements of the 20 tunes with

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

Morton and Trehub: Children’s judgements of emotion in song 633

1

0.9

0.8

Average proportion

0.7

0.6 Lyrics

0.5 Syllables

0.4 Words

0.3

0.2

0.1

0

5–6 7–8 9–10 Adults

Age group

FIGURE 1 Proportion of judgements based on musical cues for children and adults.

contradictory cues to emotion from the words and music (e.g. happy verbal

events and sad musical cues), and 10 tunes with nonsense syllables (i.e.

happy or sad tunes sung to ‘da’). Mean proportions for the four age groups

are presented in Figure 1.

For tunes sung with nonsense syllables, all groups performed near ceiling,

judging stereotypically happy versions (relative major, rapid tempo) as happy

and stereotypically sad versions (relative minor, slow tempo) as sad. For tunes

sung with lyrics depicting positive or negative events, most adults based their

judgements on the musical cues. By contrast, most children based their

judgements on the emotional implications of the lyrics, regardless of whether

the lyrics described happy or sad events. A two-way mixed analysis of

variance (ANOVA) on the proportion of responses based on musical cues

with Age as a between-subjects variable and Lyrics (Words vs Syllables) as a

within-subjects variable revealed significant main effects of Age, F(3,96) =

21.9, p < .01, and Lyrics, F(1,96) = 212.2, p < .01, and a significant Age ×

Lyrics interaction, F (3,96) = 16.2, p < .01. To identify the source of the

interaction, separate one-way ANOVAs examined the effect of Age at each

level of Lyrics. Age had no effect on responses to songs with nonsense

syllables, F(3,96) = 2.27, NS, but it had a significant effect on responses to

songs with positive or negative lyrics, F(3,96) = 20.8, p < .01. Post-hoc

analyses using Tukey’s HSD (honestly significantly different) procedure

revealed that the proportion of adults’ responses to musical cues exceeded

those of 5- to 6-year-olds (HSD = 0.66, p < .05), 7- to 8-year-olds (HSD =

0.52, p < .05), and 9- to 10-year-olds (HSD = 0.53, p < .05), but the three

child groups did not differ from each other.

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

634 Psychology of Music 35(4)

Discussion

Regardless of the prominence of pitch, tempo and mode cues in the sung

samples, children judged the singer’s feelings mainly from the content of the

lyrics, in contrast to adults, whose responses were based on expressive cues to

emotion. Although expressive musical cues to happiness (i.e. pitch level, rapid

tempo, major mode) or sadness (i.e. low pitch level, slow tempo, minor mode)

led to correct judgements in the absence of meaningful lyrics, the same cues

were fairly ineffectual for 5- to 10-year-old children when the lyrics depicted

events with the opposite emotional implications. Children seemingly ignored

the instructions to listen to the singer’s voice, focusing on what she sang

about rather than how she sang. Their problem was not one of emotion

decoding but rather of verbal cues to emotion overshadowing expressive cues

to emotion.

Children’s failure to judge the singer’s feelings from expressive cues in her

sung performance parallels their use of verbal rather than expressive cues

(i.e. prosody and paralanguage) in speech contexts with the same verbal

materials (Morton and Trehub, 2001). Children hesitate in the face of

conflicting verbal and expressive cues to emotion in speech (Morton and

Trehub, 2001), suggesting they process the emotional implications of both

speech content and prosody.2 Nevertheless, very detailed instructions are

ineffective in eliminating children’s inclination to judge a speaker’s feelings

from verbal content unless they are combined with immediate feedback

(correct or incorrect; Morton et al., 2003), suggesting possible constraints on

children’s attention flexibility (Morton and Munakata, 2002) or reasoning

about communicative intentions (Tomasello, 1999).

The present findings have parallels in research on memory of songs. For

children and adults, the words and melodies of songs are integrated in

memory (Feierabend et al., 1998; Serafine et al., 1986) such that melodies

help listeners remember the lyrics, and lyrics help them remember the

melodies. There are indications, however, that children’s representation of

words and music is less integrated than that of adults, and that the lyrics of

songs provide better memory cues than do the melodies (Feierabend et al.,

1998; Morrongiello and Roes, 1990). These studies, which focused primarily

on memory, were unconcerned with emotional aspects of sung perform-

ances. Thus, listeners’ recognition of the words or melodies of songs does not

shed light on their emotional interpretations of the songs or the basis for

those interpretations.

Although children focused on the emotional implications of the lyrics in

the context of contradictory cues from expressive and verbal aspects of the

song fragments, it is unclear whether they would do so in the context of more

conventional lyrics. Note that the lyrics in the present study did not use poetic

devices such as rhyme, alliteration, assonance and repetition. Instead, they

consisted of utterances sung only for the present purposes. Lyrics that depict

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

Morton and Trehub: Children’s judgements of emotion in song 635

events may attract more attention to their meaning than do poetic lyrics that

create a mood. Thus, an important question for future research is whether

children would be more inclined to focus on expressive musical cues for songs

with poetic lyrics.

Finally, there may be pedagogical implications of the present findings. If

children accord greater attention to the words than to the melodies of songs

(Feierabend et al., 1998; Morrongiello and Roes, 1990) and if they have

difficulty focusing on expressive aspects of sung performances, as in the

present study, then there may be situations in which Gordon’s (1993)

suggestion of introducing songs initially without words warrants serious

consideration.

NOTES

1. A within-subjects design was used to increase statistical power, but melody-only

stimuli were always presented last to avoid order effects (see Morton et al., 2003).

2. Variation in the length of stimuli used in the present study made it impossible to

compare response times across songs with consistent and inconsistent emotional

cues.

REFERENCES

Adachi, M. and Trehub, S. (1998) ‘Children’s Expression of Emotion in Song’,

Psychology of Music 26: 133–53.

Adachi, M. and Trehub, S. (2000) ‘Decoding the Expressive Intentions in Children’s

Songs’, Music Perception 18: 213–24.

Bolinger, D. (1989) Intonation and its Uses: Melody in Grammar and Discourse. Stanford,

CA: Stanford University Press.

Cohen, J.D., MacWhinney, B., Flatt, M. and Provost, J. (1993) ‘PsyScope: A New

Graphic Interactive Environment for Designing Psychology Experiments’,

Behavioral Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 25(2): 257–71.

Dalla Bella, S., Peretz, I., Rousseau, L. and Gosselin, N. (2001) ‘A Developmental

Study of the Affective Value of Tempo and Mode in Music’, Cognition 80:

B1–B10.

Dimitrovsky, L. (1964). ‘The Ability to Identify the Emotional Meaning of Vocal

Expression at Successive Age Levels’, in J.R. Davitz (ed.) The Communication of

Emotional Meaning, pp. 69–86. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Feierabend, J., Saunders, T., Holahan, J. and Getnick, P. (1998) ‘Song Recognition

among Preschool-Age Children: An Investigation of Words and Music’, Journal of

Research in Music Education 46: 351–9.

Finnegan, R.H. (1977) Oral Poetry: Its Nature, Significance, and Social Context.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frick, R. (1985) ‘Communicating Emotion: The role of Prosodic Features’,

Psychological Bulletin 97: 412–29.

Friend, M. (2001) ‘The Transition from Affective to Linguistic Meaning’, First

Language 21: 219–43.

Gordon, E. (1993) Learning Sequences in Music: Skill, Content, and Patterns: A Music

Learning Theory. Chicago: GIA Publications.

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

636 Psychology of Music 35(4)

Kartomi, M. (1980) ‘Childlikeness in Play Songs – A Case Study Among the

Pitjantjara at Yalata, South Australia’, Miscellanea Musicologica 11: 172–214.

Kastner, M. and Crowder, R. (1990) ‘Perception of the Major/Minor Distinction: IV.

Emotional Connotations in Young Children’, Music Perception 8: 189–202.

Masataka, N. (1999) ‘Preference for Infant-directed Singing in 2-Day-Old Hearing

Infants of Deaf Parents’, Developmental Psychology 35: 1001–5.

Merriam, A. (1964) The Anthropology of Music. Evanston, IL: Northwestern

University Press.

Morrongiello, B. and Roes, C. (1990) ‘Children’s Memory for New Songs: Integration

or Independent Storage of Words and Tunes?’, Journal of Experimental Child

Psychology 50: 25–38.

Morton, J.B. and Munakata, Y. (2002) ‘Active Versus Latent Representations: A

Neural Network Model of Perseveration, Dissociation, and Decalage in Early

Childhood’, Developmental Psychobiology 40: 255–65.

Morton, J.B. and Trehub, S. (2001) ‘Children’s Understanding of Emotion in Speech’,

Child Development 72: 834–43.

Morton, J.B., Trehub, S. and Zelazo, P.D. (2003) ‘Sources of Inflexibility in 6-Year-

Olds’ Understanding of Emotion in Speech’, Child Development 74: 1857–68.

Opie, I. and Opie, P. (1960) The Lore and Language of School Children. Oxford:

Clarendon.

Pantaleoni, H. (1985) On the Nature of Music. Oneonta, NY: Welkin.

Rubin, D. (1995) Memory in Oral Traditions: The Cognitive Psychology of Epic, Ballads,

and Counting-Out Rhymes. New York: Oxford University Press.

Serafine, M., Davidson, J., Crowder, R. and Repp, B. (1986) ‘On the Nature of

Melody–Text Integration in Memory for Songs’, Journal of Memory and Language

25: 123–35.

Sloboda, J.A. and O’Neill, S. (2001) ‘Emotions in Everyday Listening to Music’, in P.N.

Juslin and J.A. Sloboda (eds) Music and Emotion: Theory and Research, pp. 415–29.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tomasello, M. (1999) ‘Having Intentions, Understanding Intentions, and

Understanding Communicative Intentions’, in P.D. Zelazo, J.W. Astington and

D.R. Olsen (eds) Developing Theories of Intention: Social Understanding and Self-

control. pp. 63–75. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Trehub, S. and Trainor, L. (1998) ‘Singing to Infants: Lullabies and Play Songs’,

Advances in Infant Research 12: 43–77.

Appendix

Song fragments combining lyrics from Morton and Trehub (2001) and short

melodies were used as stimuli. Happy melodies (shown) were performed in

major keys with fast tempi. Sad melodies were performed in the diatonic

minor with slow tempi.

MELODY 1

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

Morton and Trehub: Children’s judgements of emotion in song 637

MELODY 2

MELODY 3

MELODY 4

MELODY 5

MELODY 6

MELODY 7

MELODY 8

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

638 Psychology of Music 35(4)

MELODY 9

MELODY 10

MELODY 11

MELODY 12

MELODY 13

MELODY 14

MELODY 15

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

Morton and Trehub: Children’s judgements of emotion in song 639

MELODY 16

MELODY 17

MELODY 18

MELODY 19

MELODY 20

J . B RU C E M O RT O N , PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychology at

the University of Western Ontario. Bruce received his PhD from the University of

Toronto in 2002 where he studied with Dr Sandra E. Trehub and spent two years at

the University of Denver as a post-doctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr Yuko

Munakata.

Address: Department of Psychology, University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario,

N6A 5C2 Canada. [email: bmorton3@uwo.ca]

SANDRA E. TREHUB is a Full Professor in the Department of Psychology at the

University of Toronto at Mississauga. Her research interests concern infant music

perception.

Downloaded from http://pom.sagepub.com by on April 28, 2010

You might also like

- Tunes for Teachers: Teaching....Thematic Units, Thinking Skills, Time-On-Task and TransitionsFrom EverandTunes for Teachers: Teaching....Thematic Units, Thinking Skills, Time-On-Task and TransitionsNo ratings yet

- Competency 1 AY 2023 2024 TEACHING MUSICDocument12 pagesCompetency 1 AY 2023 2024 TEACHING MUSICchaibalinNo ratings yet

- Using Music Intentionally: A handbook for all early childhood educatorsFrom EverandUsing Music Intentionally: A handbook for all early childhood educatorsNo ratings yet

- Emotion Review 2015 Swaminathan 189 97Document9 pagesEmotion Review 2015 Swaminathan 189 97Jose FloresNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument13 pagesResearch Paperapi-300790514No ratings yet

- Songs and Emotions. Are Lyrics and Melodies Equal PartnersDocument24 pagesSongs and Emotions. Are Lyrics and Melodies Equal PartnersSofía AldanaNo ratings yet

- 2introduction To MusicDocument8 pages2introduction To MusicPranav ArageNo ratings yet

- The Beneficial Impact of Music Evan ThompsonDocument5 pagesThe Beneficial Impact of Music Evan Thompsonapi-645919810No ratings yet

- 'Songese' LonghiDocument20 pages'Songese' LonghiJoão Pedro ReigadoNo ratings yet

- Assignment Child Growth & DevelopmentDocument12 pagesAssignment Child Growth & DevelopmentwannyNo ratings yet

- Music Assignment 1Document3 pagesMusic Assignment 1Rubina Devi DHOOMUNNo ratings yet

- Big Brain, Little Hands:: How to Develop Children’s Musical Skills Through Songs, Arts, and CraftsFrom EverandBig Brain, Little Hands:: How to Develop Children’s Musical Skills Through Songs, Arts, and CraftsNo ratings yet

- Rhythm and Melody As Social Signals For Infants - 221110 - 142524Document23 pagesRhythm and Melody As Social Signals For Infants - 221110 - 142524Karla MinNo ratings yet

- Behavioral and Emotional Effects of Music - 1Document6 pagesBehavioral and Emotional Effects of Music - 1Mia Lorena JandocNo ratings yet

- Music: The Language of Emotion: October 2013Document28 pagesMusic: The Language of Emotion: October 2013Eduardo PortugalNo ratings yet

- Children and Music: Benefits of Music in Child DevelopmentDocument42 pagesChildren and Music: Benefits of Music in Child DevelopmentMarvin TabilinNo ratings yet

- Senior Paper OutlineDocument23 pagesSenior Paper Outlineapi-592374634No ratings yet

- EMU PerceptionofsixbasicemotionsinmusicDocument15 pagesEMU PerceptionofsixbasicemotionsinmusicMaría Hernández MiraveteNo ratings yet

- Current Emotion Research in Music Psychology - Swathi Swaminathan, E. Glenn SchellenbergDocument9 pagesCurrent Emotion Research in Music Psychology - Swathi Swaminathan, E. Glenn SchellenbergAabirNo ratings yet

- E 7 A 87124 e 7 BF 01111 B 24Document9 pagesE 7 A 87124 e 7 BF 01111 B 24api-668536957No ratings yet

- Infants Memory For Musical PerformancesDocument8 pagesInfants Memory For Musical PerformancesLeonardo PunshonNo ratings yet

- Perception of Six Basic Emotions in MusicDocument16 pagesPerception of Six Basic Emotions in MusicOana Rusu100% (2)

- Precursors To The Performing Arts in Infancy and Early ChildhoodDocument18 pagesPrecursors To The Performing Arts in Infancy and Early ChildhoodJoão Pedro ReigadoNo ratings yet

- Music 1Document4 pagesMusic 1fuji michaelNo ratings yet

- Competency 2 AY 2023 2024 TEACHING MUSICDocument14 pagesCompetency 2 AY 2023 2024 TEACHING MUSICchaibalinNo ratings yet

- Background Music Its Effect On The Emotional Responsiveness of Psychology Students On ICI College at Santa Maria BulacanDocument3 pagesBackground Music Its Effect On The Emotional Responsiveness of Psychology Students On ICI College at Santa Maria BulacanVenus Mae MeñequeNo ratings yet

- Music and Positive DevelopmentDocument7 pagesMusic and Positive DevelopmentDillon SlaterNo ratings yet

- Emotion Perception in MusicDocument5 pagesEmotion Perception in Musicnefeli123No ratings yet

- Claudia Gluschankof MERYC 2007Document7 pagesClaudia Gluschankof MERYC 2007Shir MusicNo ratings yet

- Harris2019 - "They'Re Playing Our Song"Document17 pagesHarris2019 - "They'Re Playing Our Song"alvaro_arroyo17No ratings yet

- Classical Music vs. Preferred Music Genre: Effect On Memory RecallDocument14 pagesClassical Music vs. Preferred Music Genre: Effect On Memory RecallAGLDNo ratings yet

- REVIEWER: Betty Starobinsky TITLE: "Music Listening Preferences in Early Life: Infants' Responses ToDocument6 pagesREVIEWER: Betty Starobinsky TITLE: "Music Listening Preferences in Early Life: Infants' Responses Toapi-263171218No ratings yet

- + 2002 ART - Boal-Palheiros - Hargreaves-BCMREDocument7 pages+ 2002 ART - Boal-Palheiros - Hargreaves-BCMREBirgita Solange SantosNo ratings yet

- Creating Centers For Musical PlayDocument8 pagesCreating Centers For Musical Playapi-235065651No ratings yet

- Using Music With Infants Toddlers1Document6 pagesUsing Music With Infants Toddlers1api-233310437100% (1)

- Musical Predispositions in InfancyDocument17 pagesMusical Predispositions in InfancydanielabanderasNo ratings yet

- Miranda 2011Document11 pagesMiranda 2011rnuevo2No ratings yet

- SMMC-THESIS-PAPER Educ Chapter123Document24 pagesSMMC-THESIS-PAPER Educ Chapter123Adorio JillianNo ratings yet

- 10.4324 9781315294575-4 ChapterpdfDocument25 pages10.4324 9781315294575-4 ChapterpdfOwzic Music SchoolNo ratings yet

- Pre-K Music and The Emergent ReaderDocument11 pagesPre-K Music and The Emergent ReaderAli Erin100% (1)

- Final For DefenseDocument33 pagesFinal For DefenseRALPH JOSEPH SANTOSNo ratings yet

- Individual Essay ExampleDocument11 pagesIndividual Essay ExampleQuyen HoangNo ratings yet

- Music Makes You SmarterDocument9 pagesMusic Makes You SmarterkajsdkjqwelNo ratings yet

- Analisis Pola Ritme Dan Bentuk Lagu AnakDocument10 pagesAnalisis Pola Ritme Dan Bentuk Lagu AnakTernakayam SurabayaNo ratings yet

- Importance of Musicin ECEDocument10 pagesImportance of Musicin ECEdasaiyahslb957No ratings yet

- Music Makes People HappyDocument2 pagesMusic Makes People HappyLudwig Santos-Mindo De Varona-LptNo ratings yet

- Word PlayDocument7 pagesWord Playapi-358036775No ratings yet

- LessonPlans VocalDocument53 pagesLessonPlans VocalLorena Do Val100% (2)

- Sadness Along Music and Its Impact in Mental BalanceDocument2 pagesSadness Along Music and Its Impact in Mental BalanceFrancisco RuizNo ratings yet

- GerryUnrauTrainor 2012 PDFDocument11 pagesGerryUnrauTrainor 2012 PDFLaura F MerinoNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0163638398900558-Main 2Document12 pages1-S2.0-S0163638398900558-Main 2Ivan OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Indonesian Children's Song in The Educational PerspectiveDocument12 pagesIndonesian Children's Song in The Educational PerspectiveAyu Susantina Pusparani PribadiNo ratings yet

- The 337 Final PaperDocument6 pagesThe 337 Final Paperapi-310604850No ratings yet

- Art Research IIDocument5 pagesArt Research IIhonelyn r saguranNo ratings yet

- Musical Play ChapterDocument22 pagesMusical Play ChapterColegio CercantesNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Music Genres (Pop & Classical) On Critical Thinking of Grade 10 Students of Marian College.Document22 pagesThe Effect of Music Genres (Pop & Classical) On Critical Thinking of Grade 10 Students of Marian College.Gift Cyrl SilabayNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 016Document5 pagesJurnal 016Yuli RohmiyatiNo ratings yet

- Bemusi 203 Course Coverage 1st Sem.2023Document102 pagesBemusi 203 Course Coverage 1st Sem.2023Keysee EgcaNo ratings yet

- A Semi Detailed Lesson Plan inDocument10 pagesA Semi Detailed Lesson Plan indez umeranNo ratings yet

- Word AccentDocument21 pagesWord AccentRahul SangwanNo ratings yet

- Types of Metrical FeetDocument3 pagesTypes of Metrical FeetДжинси МілаNo ratings yet

- First Quarter: Prosodic Features of SpeechDocument5 pagesFirst Quarter: Prosodic Features of SpeechAbi Ramirez Ramos-Sadang100% (1)

- TRTRDocument53 pagesTRTRAxel AgeasNo ratings yet

- Group 4-Concepts and TestsDocument21 pagesGroup 4-Concepts and TestsTikuNo ratings yet

- Altmann - History of PsycholinguisticsDocument42 pagesAltmann - History of PsycholinguisticsChristiano TitoneliNo ratings yet

- Lesson Exemplar: Learning Task 1: Examine The Jumbled Letters Below and Identify TheDocument7 pagesLesson Exemplar: Learning Task 1: Examine The Jumbled Letters Below and Identify TheGinelyn Maralit100% (3)

- English Grade 9 q1Document46 pagesEnglish Grade 9 q1Amayo100% (1)

- Topic and FocusDocument299 pagesTopic and FocusAli Muhammad YousifNo ratings yet

- Lesson-Plans-Week-6-6th-Grade-Band-Sept-8-12 2014Document4 pagesLesson-Plans-Week-6-6th-Grade-Band-Sept-8-12 2014api-263088653No ratings yet

- Quezonian Educational College, Inc.: - Introduction To LinguisticsDocument6 pagesQuezonian Educational College, Inc.: - Introduction To LinguisticsBelle VillasinNo ratings yet

- 0 Voice ConversionDocument26 pages0 Voice ConversiontileNo ratings yet

- Sir ShakeelDocument55 pagesSir ShakeelShakeel Amjad100% (1)

- Daily Lesson Log Grade 7 EnglishDocument2 pagesDaily Lesson Log Grade 7 EnglishMylene83% (6)

- Cur Map in English 8Document9 pagesCur Map in English 8Eliza Marie Lisbe100% (1)

- English Suprasegmentals 1. Stress 2. Pitch Levels 3. Juncture 4. Terminal Contours 5. IntonationDocument66 pagesEnglish Suprasegmentals 1. Stress 2. Pitch Levels 3. Juncture 4. Terminal Contours 5. IntonationNurli GirsangNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language PDFDocument484 pagesThe Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language PDFClaudia Moreno Ruiz100% (3)

- Introduction To Artificial IntelligenceDocument19 pagesIntroduction To Artificial IntelligenceMard GeerNo ratings yet

- Goodwins Assessment ContextDocument45 pagesGoodwins Assessment ContextJosh GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Module TSLB3013Document88 pagesModule TSLB3013TESLSJKC-0620 Wong Ben LuNo ratings yet

- Seminar 7Document2 pagesSeminar 7anusichkaNo ratings yet

- Grade 8 English 3rd Quarter DLL 3rd WeekDocument3 pagesGrade 8 English 3rd Quarter DLL 3rd WeekFil AnneNo ratings yet

- Death of Hired ManDocument17 pagesDeath of Hired ManZahra KhanNo ratings yet

- The Concepts of Style and StylisticsDocument26 pagesThe Concepts of Style and Stylisticsere chanNo ratings yet

- 9m.2-L.6@by The Railway Side & Prosodic Features of SpeechDocument3 pages9m.2-L.6@by The Railway Side & Prosodic Features of SpeechMaria BuizonNo ratings yet

- First Quarter: Lcs For Reading - Grade 7Document8 pagesFirst Quarter: Lcs For Reading - Grade 7elms heyresNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature A. Theoretical Framework 1. The Nature of PronunciationDocument25 pagesReview of Related Literature A. Theoretical Framework 1. The Nature of PronunciationMike Nurmalia SariNo ratings yet

- Introduction To PhonologyDocument6 pagesIntroduction To PhonologyAgus sumardyNo ratings yet

- Narrow and Broad FocusDocument4 pagesNarrow and Broad FocussebasarauzoNo ratings yet