Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and The Postpartum Period - ACOG

Uploaded by

André MesquitaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and The Postpartum Period - ACOG

Uploaded by

André MesquitaCopyright:

Available Formats

Login

Desktop Site

Menu ̘

Home Resources & Publications Committee Opinions

Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

Page Navigation ̘

Number 650, December 2015 (Replaces Committee Opinion Number 267, January 2002)

Committee on Obstetric Practice

This document reflects emerging clinical and scientific advances as of the date issued and is subject to

change. The information should not be construed as dictating an exclusive course of treatment or

procedure to be followed.

PDF Format

Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the

Postpartum Period

ABSTRACT: Physical activity in all stages of life maintains and improves cardiorespiratory fitness,

reduces the risk of obesity and associated comorbidities, and results in greater longevity. Physical

activity in pregnancy has minimal risks and has been shown to benefit most women, although some

modification to exercise routines may be necessary because of normal anatomic and physiologic

changes and fetal requirements. Women with uncomplicated pregnancies should be encouraged to

engage in aerobic and strength-conditioning exercises before, during, and after pregnancy.

Obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers should carefully evaluate women with

medical or obstetric complications before making recommendations on physical activity participation

during pregnancy. Although frequently prescribed, bed rest is only rarely indicated and, in most cases,

allowing ambulation should be considered. Regular physical activity during pregnancy improves or

maintains physical fitness, helps with weight management, reduces the risk of gestational diabetes in

obese women, and enhances psychologic well-being. An exercise program that leads to an eventual

goal of moderate-intensity exercise for at least 20–30 minutes per day on most or all days of the week

should be developed with the patient and adjusted as medically indicated. Additional research is

needed to study the effects of exercise on pregnancy-specific outcomes and to clarify the most effective

behavioral counseling methods, and the optimal intensity and frequency of exercise. Similar work is

needed to create an improved evidence base concerning the effects of occupational physical activity on

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 1 de 12

maternal–fetal health.

Recommendations

Regular physical activity in all phases of life, including pregnancy, promotes health benefits. Pregnancy

is an ideal time for maintaining or adopting a healthy lifestyle and the American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists makes the following recommendations:

Physical activity in pregnancy has minimal risks and has been shown to benefit most women, although some

modification to exercise routines may be necessary because of normal anatomic and physiologic changes and

fetal requirements.

A thorough clinical evaluation should be conducted before recommending an exercise program to ensure that a

patient does not have a medical reason to avoid exercise.

Women with uncomplicated pregnancies should be encouraged to engage in aerobic and strength-conditioning

exercises before, during, and after pregnancy.

Obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers should carefully evaluate women with medical or

obstetric complications before making recommendations on physical activity participation during pregnancy.

Although frequently prescribed, bed rest is only rarely indicated and, in most cases, allowing ambulation should be

considered.

Regular physical activity during pregnancy improves or maintains physical fitness, helps with weight management,

reduces the risk of gestational diabetes in obese women, and enhances psychologic well-being.

Additional research is needed to study the effects of exercise on pregnancy-specific outcomes, and to clarify the

most effective behavioral counseling methods and the optimal intensity and frequency of exercise. Similar work is

needed to create an improved evidence base concerning the effects of occupational physical activity on maternal–

fetal health.

Introduction

Physical activity, defined as any bodily movement produced by the contraction of skeletal muscles (1)

in all stages of life maintains and improves cardiorespiratory fitness, reduces the risk of obesity and

associated comorbidities, and results in greater longevity. Women who begin their pregnancy with a

healthy lifestyle (eg, exercise, good nutrition, nonsmoking) should be encouraged to maintain those

healthy habits. Those who do not have healthy lifestyles should be encouraged to view the

preconception period and pregnancy as opportunities to embrace healthier routines. Exercise, defined

as physical activity consisting of planned, structured, and repetitive bodily movements done to improve

one or more components of physical fitness (1), is an essential element of a healthy lifestyle, and

obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers should encourage their patients to

continue or to commence exercise as an important component of optimal health.

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 2 de 12

In 2008, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services issued physical activity guidelines for

Americans (2). For healthy pregnant and postpartum women, the guidelines recommend at least 150

minutes per week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity (ie, equivalent to brisk walking). This activity

should be spread throughout the week and adjusted as medically indicated. The guidelines advise that

pregnant women who habitually engage in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity (ie, the equivalent of

running or jogging) or who are highly active “can continue physical activity during pregnancy and the

postpartum period, provided that they remain healthy and discuss with their health care provider how

and when activity should be adjusted over time” (2). The World Health Organization and the American

College of Sports Medicine have issued evidence-based recommendations indicating that the beneficial

effects of exercise in most adults are indisputable and that the benefits far outweigh the risks (3, 4).

Physical inactivity is the fourth-leading risk factor for early mortality worldwide (3). In pregnancy,

physical inactivity and excessive weight gain have been recognized as independent risk factors for

maternal obesity and related pregnancy complications, including gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

(5–7). Some patients, obstetrician–gynecologists, and other obstetric care providers are concerned that

regular physical activity during pregnancy may cause miscarriage, poor fetal growth, musculoskeletal

injury, or premature delivery. For uncomplicated pregnancies, these concerns have not been

substantiated (8–12). In the absence of obstetric or medical complications or contraindications (Box 1,

Box 2), physical activity in pregnancy is safe and desirable, and pregnant women should be encouraged

to continue or to initiate safe physical activities (Box 3). In women who have obstetric or medical

comorbidities, exercise regimens should be individualized. Obstetrician–gynecologists and other

obstetric care providers should carefully evaluate women with medical or obstetric complications before

making recommendations on physical activity participation during pregnancy.

Anatomic and Physiologic Aspects of Exercise in Pregnancy

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 3 de 12

Pregnancy results in anatomic and physiologic changes that should be considered when prescribing

exercise. The most distinct changes during pregnancy are increased weight gain and a shift in the point

of gravity that results in progressive lordosis. These changes lead to an increase in the forces across

joints and the spine during weight-bearing exercise. As a result, more than 60% of all pregnant women

experience low back pain (13). Strengthening of abdominal and back muscles could minimize this risk.

Blood volume, heart rate, stroke volume, and cardiac output normally increase during pregnancy, while

systemic vascular resistance decreases. These hemodynamic changes establish the circulatory reserve

necessary to sustain the pregnant woman and fetus at rest and during exercise. Motionless postures,

such as certain yoga positions and the supine position, may result in decreased venous return and

hypotension in 10–20% of all pregnant women and should be avoided as much as possible (14).

In pregnancy, there are also profound respiratory changes. Minute ventilation increases up to 50%,

primarily as a result of the increased tidal volume. Because of a physiologic decrease in pulmonary

reserve, the ability to exercise anaerobically is impaired, and oxygen availability for strenuous aerobic

exercise and increased work load consistently lags. The physiologic respiratory alkalosis of pregnancy

may not be sufficient to compensate for the developing metabolic acidosis of strenuous exercise.

Decreases in subjective work load and maximum exercise performance in pregnant women, particularly

in those who are overweight or obese, limit their ability to engage in more strenuous physical activities

(15). Aerobic training in pregnancy has been shown to increase aerobic capacity in normal weight and

overweight pregnant women (16–18).

Temperature regulation is highly dependent on hydration and environmental conditions. During

exercise, pregnant women should stay well-hydrated, wear loose-fitting clothing, and avoid high heat

and humidity to protect against heat stress, particularly during the first trimester (19). Although

exposure to heat from sources like hot tubs, saunas, or fever has been associated with an increased

risk of neural tube defects (20), exercise would not be expected to increase core body temperature into

the range of concern. At least one study found no association between exercise and neural tube defects

(21).

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 4 de 12

Despite the fact that pregnancy is associated with profound anatomic and physiologic changes, exercise

has minimal risks and has been shown to benefit most women. The most common sports-related

injuries in pregnancy are musculoskeletal, by and large related to lower extremities edema (80%) and

joint laxity (22).

Fetal Response to Maternal Exercise

Most of the studies addressing fetal response to maternal exercise have focused on fetal heart rate

changes and birth weight. Studies have demonstrated minimum-to-moderate increases in fetal heart

rate by 10–30 beats per minute over the baseline during or after exercise (23–26). Three meta-

analyses concluded that the differences in birth weight were minimal to none in women who exercised

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 5 de 12

during pregnancy compared with controls (27–29). However, women who continued to exercise

vigorously during the third trimester were more likely to deliver infants weighing 200–400 g less than

comparable controls, although there was not an increased risk of fetal growth restriction (27–29). A

cohort study that assessed umbilical artery blood flow, fetal heart rates, and biophysical profiles before

and after strenuous exercise in the second trimester demonstrated that 30 minutes of strenuous

exercise was well tolerated by women and fetuses in active and inactive pregnant women. (26).

Benefits of Exercise During Pregnancy

Regular aerobic exercise during pregnancy has been shown to improve or maintain physical fitness (8,

9, 27). Although the evidence is limited, some benefit to pregnancy outcomes has been shown, and

there is no evidence of harm when not contraindicated. Observational studies of women who exercise

during pregnancy have shown benefits such as decreased GDM (6, 30–32), cesarean and operative

vaginal delivery (9, 33, 34), and postpartum recovery time (9), although evidence from randomized

controlled trials is limited. In those instances where women experience low-back pain, water exercise is

an excellent alternative (35). Studies have shown that exercise during pregnancy can lower glucose

levels in women with GDM (36, 37), or help prevent preeclampsia (38). Exercise has shown only a

modest decrease in overall weight gain (1–2 kg) in normal weight, overweight, and obese women (39,

40).

Recommending an Exercise Program

Motivational Counseling

Pregnancy is an ideal time for behavior modification and for adopting a healthy lifestyle because of

increased motivation and frequent access to medical supervision. Patients are more likely to control

weight, increase physical activity, and improve their diet if their physician recommends that they do so

(41). Motivational counseling tools such as the Five A’s (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, and Arrange),

originally developed for smoking cessation, have been used successfully for diet and exercise

counseling (42, 43). Obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers can consider

adopting the Five A’s approach for women with uncomplicated pregnancies who have no

contraindications to exercise.

Prescribing an Individualized Exercise Program

The principles of exercise prescription for pregnant women do not differ from those for the general

population (2). A thorough clinical evaluation should be conducted before recommending an exercise

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 6 de 12

program to ensure that a patient does not have medical reasons to avoid exercise. An exercise program

that leads to an eventual goal of moderate-intensity exercise for at least 20–30 minutes per day on

most or all days of the week should be developed with the patient and adjusted as medically indicated.

Box 3 lists examples of safe and unsafe physical activities in pregnancy. Women with uncomplicated

pregnancies should be encouraged to engage in physical activities before, during, and after pregnancy.

Because blunted and normal heart-rate responses to exercise have been reported in pregnant women,

the use of ratings of perceived exertion may be a more effective means to monitor exercise intensity

during pregnancy than heart-rate parameters (44). For moderate-intensity exercise, ratings of

perceived exertion should be 13–14 (somewhat hard) on the 6–20 Borg scale of perceived exertion

(Table 1). Using the “talk test” is another way to measure exertion. As long as a woman can carry on a

conversation while exercising, she is likely not overexerting herself (45). Women should be advised to

remain well hydrated, avoid long periods of lying flat on their backs, and stop exercising if they have

any of the warning signs shown in Box 4.

Pregnant women who were sedentary before pregnancy should follow a more gradual progression of

exercise. Although an upper level of safe exercise intensity has not been established, women who were

regular exercisers before pregnancy and who have uncomplicated, healthy pregnancies should be able

to engage in high-intensity exercise programs, such as jogging and aerobics, with no adverse effects.

High-intensity or prolonged exercise in excess of 45 minutes can lead to hypoglycemia; therefore,

adequate caloric intake before exercise, or limiting the exercise session, is essential to minimize this

risk (46).

Prolonged exercise should be performed in a thermoneutral environment or in controlled environmental

conditions (air conditioning) with close attention paid to proper hydration and caloric intake. In studies

of pregnant women who exercised in which physical activity was self-paced in a temperature-controlled

environment, core body temperatures rose less than 1.5°C over 30 minutes and stayed within safe

limits (46). Finally, although physical activity and dehydration in pregnancy have been associated with

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 7 de 12

a small increase in uterine contractions (47), there is only anecdotal evidence that even strenuous

training causes preterm labor or delivery.

Recreational Activities

Participation in a wide range of recreational activities is safe. Activities with high risk of abdominal

trauma should be avoided (Box 3). Scuba diving should be avoided in pregnancy because of the

inability of the fetal pulmonary circulation to filter bubble formation (48). For lowlanders, physical

activity up to 6,000 feet altitude is safe in pregnancy (49).

Special Populations

Several reviews have determined that there is no credible evidence to prescribe bed rest in pregnancy,

which is most commonly prescribed for the prevention of preterm labor. It is the American College of

Obstetrician and Gynecologists’ position that “bed rest is not effective for the prevention of preterm

birth and should not be routinely recommended” (50, 51). Patients prescribed prolonged bed rest or

restricted physical activity are at risk of venous thromboembolism, bone demineralization, and

deconditioning. Although frequently prescribed, bed rest is only rarely indicated and, in most cases,

allowing ambulation should be considered.

Obese pregnant women should be encouraged to engage in healthy lifestyle modification in pregnancy

that includes physical activities and judicious diets (5). Obese women should start with low-intensity,

short periods of exercise and gradually increase as able. In recent studies examining the effects of

exercise among pregnant, obese women, the women have demonstrated modest reductions in weight

gain and no adverse outcomes among those assigned to exercise (39, 52).

Competitive athletes require frequent and closer supervision because they tend to maintain a more

strenuous training schedule throughout pregnancy and resume high-intensity postpartum training

sooner as compared to others. Such athletes should pay particular attention to avoiding hyperthermia,

maintaining proper hydration, and sustaining adequate caloric intake to prevent weight loss, which may

adversely affect fetal growth.

Occupational Physical Activity

The evidence regarding any possible association between fetal–maternal health outcomes and

occupational physical activity is mixed and limited. A meta-analysis based on 62 reports assessed the

evidence relating preterm delivery, low birth weight, small for gestational age, preeclampsia, and

gestational hypertension to five occupational exposures (work hours, shift work, lifting, standing, and

physical work load) (53). Although the analysis was limited by the heterogeneity of exposure

definitions, especially for lifting and heavy work load, most of the estimates of risk pointed to small or

null effects. In contrast, a cohort study of more than 62,000 Danish women reported a dose–response

relationship between total daily burden lifted and preterm birth with loads more than 1,000 kg per day

(54). In this study, lifting heavy loads (greater than 20 kg) more than 10 times per day was associated

with an increased risk of preterm birth.

The American Medical Association Council on Scientific Affairs 1984 guidelines on weight limits for

occupational lifting during pregnancy have been used by clinicians for many years but are not specific,

do not define the terms repetitive and intermittent lifting, and do not consider the type of lifting (55). A

more recent proposed guideline addresses these issues and is based on the National Institute for

Occupational Safety and Health equation that determines the maximum recommended weight limit.

The recommended weight limit equation provides weight limits for lifting that would be acceptable to

90% of healthy women (56). A study applied the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health’s

lifting equation to define recommended weight limits for a broad range of lifting patterns for pregnant

women in an effort to define lifting thresholds that most pregnant workers with uncomplicated

pregnancies should be able to perform without increased risk to maternal or fetal health (57). The

same authors identified lifting conditions that pose higher risk of musculoskeletal injury and suggested

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 8 de 12

that obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers use their best clinical judgment to

determine a recommendation plan for the patient, which might include a formal request for an

occupational health professional to perform an analysis to determine maximum weight limits based on

actual lifting conditions.

Exercise in the Postpartum Period

The postpartum period is an opportune time for obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care

providers to initiate, recommend, and reinforce a healthy behavior lifestyle. Resuming exercise

activities or incorporating new exercise routines after delivery is important in supporting lifelong

healthy habits. Several reports indicate that women’s level of participation in exercise programs

diminishes after childbirth, frequently leading to overweight and obesity (58, 59). Exercise routines

may be resumed gradually after pregnancy as soon as medically safe, depending on the mode of

delivery, vaginal or cesarean, and the presence or absence of medical or surgical complications. Some

women are capable of resuming physical activities within days of delivery. In the absence of medical or

surgical complications, rapid resumption of these activities has not been found to result in adverse

effects. Pelvic floor exercises could be initiated in the immediate postpartum period.

Regular aerobic exercise in lactating women has been shown to improve maternal cardiovascular fitness

without affecting milk production, composition, or infant growth. (60). Nursing women should consider

feeding their infants before exercising in order to avoid exercise discomfort of engorged breast. Nursing

women

also should ensure adequate hydration before commencing physical activity.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that pregnancy is associated with profound anatomic and physiologic changes, exercise

has minimal risks and has been shown to benefit most women. Women with uncomplicated pregnancies

should be encouraged to engage in physical activities before, during, and after pregnancy.

Obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers should carefully evaluate women with

medical or obstetric complications before making recommendations on physical activity participation

during pregnancy. Although the evidence is limited, some benefit to pregnancy outcomes has been

shown and there is no evidence of harm when not contraindicated. Physical activity and exercise during

pregnancy promotes physical fitness and may prevent excessive gestational weight gain. Exercise may

reduce the risk of gestational diabetes, preeclampsia, and cesarean deliveries. Additional research is

needed to study the effects of exercise on pregnancy-specific conditions and outcomes, and to further

clarify effective behavioral counseling methods and optimal type, frequency, and intensity of exercise.

Similar research is needed to improve evidence-based information concerning the effects of

occupational physical activity on maternal–fetal health.

Resource

Artal R, Hopkins S. Exercise. Clin Update Womens Health Care 2013;XII(2):1–105.

References

1. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 9th ed.

Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. ꔃ

2. Department of Health and Human Services. 2008 physical activity guidelines for Americans. Washington, DC:

DHHS; 2008. Available at: http://health.gov/paguidelines. Retrieved August 18, 2015. ꔃ

3. World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Available at: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/9789241599979/en. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

ꔃ

4. Garber CE, Blissmer B, Deschenes MR, Franklin BA, Lamonte MJ, Lee IM, et al. American College of Sports

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 9 de 12

Medicine position stand. Quantity and quality of exercise for developing and maintaining cardiorespiratory,

musculoskeletal, and neuromotor fitness in apparently healthy adults: guidance for prescribing exercise. American

College of Sports Medicine. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2011;43:1334–59. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

5. Obesity in pregnancy. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 549. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Obstet Gynecol 2013;121:213–7. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] ꔃ

6. Dye TD, Knox KL, Artal R, Aubry RH, Wojtowycz MA. Physical activity, obesity, and diabetes in pregnancy. Am J

Epidemiol 1997;146:961–5. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

7. Artal R. The role of exercise in reducing the risks of gestational diabetes mellitus in obese women. Best Pract Res

Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2015;29:123–32. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

8. de Oliveria Melo AS, Silva JL, Tavares JS, Barros VO, Leite DF, Amorim MM. Effect of a physical exercise

program during pregnancy on uteroplacental and fetal blood flow and fetal growth: a randomized controlled trial.

Obstet Gynecol 2012;120:302–10. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] ꔃ

9. Price BB, Amini SB, Kappeler K. Exercise in pregnancy: effect on fitness and obstetric outcomes-a randomized

trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:2263–9. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

10. Barakat R, Pelaez M, Montejo R, Refoyo I, Coteron J. Exercise throughout pregnancy does not cause preterm

delivery: a randomized, controlled trial. J Phys Act Health 2014;11:1012–7. [PubMed] ꔃ

11. Owe KM, Nystad W, Skjaerven R, Stigum H, Bo K. Exercise during pregnancy and the gestational age

distribution: a cohort study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2012;44:1067–74. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

12. Thangaratinam S, Rogozinska E, Jolly K, Glinkowski S, Duda W, Borowiack E, et al. Interventions to reduce or

prevent obesity in pregnant women: a systematic review. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:iii–iv, 1–191. [PubMed]

[Full Text] ꔃ

13. Wang SM, Dezinno P, Maranets I, Berman MR, Caldwell-Andrews AA, Kain ZN. Low back pain during pregnancy:

prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(1):65–70. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology]

ꔃ

14. Clark SL, Cotton DB, Pivarnik JM, Lee W, Hankins GD, Benedetti TJ, et al. Position change and central

hemodynamic profile during normal third-trimester pregnancy and post partum [published erratum appears in Am

J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165:241]. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:883–7. [PubMed] ꔃ

15. Artal R, Wiswell R, Romem Y, Dorey F. Pulmonary responses to exercise in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol

1986;154:378–83. [PubMed] ꔃ

16. South-Paul JE, Rajagopal KR, Tenholder MF. The effect of participation in a regular exercise program upon

aerobic capacity during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 1988;71:175–9. [PubMed] ꔃ

17. Marquez-Sterling S, Perry AC, Kaplan TA, Halberstein RA, Signorile JF. Physical and psychological changes with

vigorous exercise in sedentary primigravidae. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:58–62. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

18. Santos IA, Stein R, Fuchs SC, Duncan BB, Ribeiro JP, Kroeff LR, et al. Aerobic exercise and submaximal

functional capacity in overweight pregnant women: a randomized trial. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:243–9. [PubMed]

[Obstetrics & Gynecology] ꔃ

19. American College of Sports Medicine. Exercise during pregnancy. ACSM Current Comment. Available at:

https://www.acsm.org/docs/current-comments/exerciseduringpregnancy.pdf. Retrieved August 18, 2015. ꔃ

20. Milunsky A, Ulcickas M, Rothman KJ, Willett W, Jick SS, Jick H. Maternal heat exposure and neural tube defects.

JAMA 1992;268:882–5. [PubMed] ꔃ

21. Carmichael SL, Shaw GM, Neri E, Schaffer DM, Selvin S. Physical activity and risk of neural tube defects. Matern

Child Health J 2002;6:151–7. [PubMed] ꔃ

22. Robertson EG. The natural history of oedema during pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw 1971;78:520–9.

[PubMed] ꔃ

23. Carpenter MW, Sady SP, Hoegsberg B, Sady MA, Haydon B, Cullinane EM, et al. Fetal heart rate response to

maternal exertion. JAMA 1988;259:3006–9. [PubMed] ꔃ

24. Wolfe LA, Lowe-Wyldem SJ, Tanmer JE, McGrath MJ. Fetal heart rate during maternal static exercise [abstract].

Can J Sport Sci 1988;13:95–6. ꔃ

25. Artal R, Rutherford S, Romem Y, Kammula RK, Dorey FJ, Wiswell RA. Fetal heart rate responses to maternal

exercise. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1986;155:729–33. [PubMed] ꔃ

26. Szymanski LM, Satin AJ. Exercise during pregnancy: fetal responses to current public health guidelines. Obstet

Gynecol 2012;119:603–10. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] ꔃ

27. Kramer MS, McDonald SW. Aerobic exercise for women during pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews 2006, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000180. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000180.pub2. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 10 de 12

28. Lokey EA, Tran ZV, Wells CL, Myers BC, Tran AC. Effects of physical exercise on pregnancy outcomes: a meta-

analytic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1991;23:1234–9. [PubMed] ꔃ

29. Leet T, Flick L. Effect of exercise on birthweight. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2003;46:423–31. [PubMed] ꔃ

30. Cordero Y, Mottola MF, Vargas J, Blanco M, Barakat R. Exercise is associated with a reduction in gestational

diabetes mellitus. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2015;47:1328–33. [PubMed] ꔃ

31. Dempsey JC, Sorensen TK, Williams MA, Lee IM, Miller RS, Dashow EE, et al. Prospective study of gestational

diabetes mellitus risk in relation to maternal recreational physical activity before and during pregnancy. Am J

Epidemiol 2004;159:663–70. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

32. Liu J, Laditka JN, Mayer-Davis EJ, Pate RR. Does physical activity during pregnancy reduce the risk of

gestational diabetes among previously inactive women? Birth 2008;35:188–95. [PubMed] ꔃ

33. Barakat R, Pelaez M, Lopez C, Montejo R, Coteron J. Exercise during pregnancy reduces the rate of cesarean

and instrumental deliveries: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25:2372–

6. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

34. Pennick V, Liddle SD. Interventions for preventing and treating pelvic and back pain in pregnancy. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 8. Art. No.: CD001139. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001139.pub3.

[PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

35. Kihlstrand M, Stenman B, Nilsson S, Axelsson O. Water-gymnastics reduced the intensity of back/low back pain in

pregnant women. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1999;78:180–5. [PubMed] ꔃ

36. Jovanovic-Peterson L, Durak EP, Peterson CM. Randomized trial of diet versus diet plus cardiovascular

conditioning on glucose levels in gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1989;161:415–9. [PubMed] ꔃ

37. Garcia-Patterson A, Martin E, Ubeda J, Maria MA, de Leiva A, Corcoy R. Evaluation of light exercise in the

treatment of gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care 2001;24:2006–7. [PubMed] ꔃ

38. Meher S, Duley L. Exercise or other physical activity for preventing pre-eclampsia and its complications. Cochrane

Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD005942. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

39. Choi J, Fukuoka Y, Lee JH. The effects of physical activity and physical activity plus diet interventions on body

weight in overweight or obese women who are pregnant or in postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis

of randomized controlled trials. Prev Med 2013;56:351–64. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

40. Muktabhant B, Lawrie TA, Lumbiganon P, Laopaiboon M. Diet or exercise, or both, for preventing excessive

weight gain in pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015, Issue 6. Art. No.: CD007145. DOI:

10.1002/14651858.CD007145.pub3. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

41. Nawaz H, Adams ML, Katz DL. Physician-patient interactions regarding diet, exercise, and smoking. Prev Med

2000;31:652–7. [PubMed] ꔃ

42. Serdula MK, Khan LK, Dietz WH. Weight loss counseling revisited. JAMA 2003;289:1747–50. [PubMed] [Full

Text] ꔃ

43. Alexander SC, Cox ME, Boling Turer CL, Lyna P, Ostbye T, Tulsky JA, et al. Do the five A’s work when physicians

counsel about weight loss? Fam Med 2011;43:179–84. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

44. McMurray RG, Mottola MF, Wolfe LA, Artal R, Millar L, Pivarnik JM. Recent advances in understanding maternal

and fetal responses to exercise. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1993;25:1305–21. [PubMed] ꔃ

45. Persinger R, Foster C, Gibson M, Fater DC, Porcari JP. Consistency of the talk test for exercise prescription. Med

Sci Sports Exerc 2004;36:1632–6. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

46. Soultanakis HN, Artal R, Wiswell RA. Prolonged exercise in pregnancy: glucose homeostasis, ventilatory and

cardiovascular responses. Semin Perinatol 1996;20:315–27. [PubMed] ꔃ

47. Grisso JA, Main DM, Chiu G, Synder ES, Holmes JH. Effects of physical activity and life-style factors on uterine

contraction frequency. Am J Perinatol 1992;9:489–92. [PubMed] ꔃ

48. Camporesi EM. Diving and pregnancy. Semin Perinatol 1996;20:292–302. [PubMed] ꔃ

49. Artal R, Fortunato V, Welton A, Constantino N, Khodiguian N, Villalobos L, et al. A comparison of cardiopulmonary

adaptations to exercise in pregnancy at sea level and altitude. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1995;172:1170–8; discussion

1178–80. [PubMed] ꔃ

50. Management of preterm labor. ACOG Practice Bulletin no. 127. American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:1308–17. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] ꔃ

51. Crowther CA, Han S. Hospitalisation and bed rest for multiple pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic

Reviews 2010, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD000110. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000110.pub2. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

52. Renault KM, Norgaard K, Nilas L, Carlsen EM, Cortes D, Pryds O, et al. The Treatment of Obese Pregnant

Women (TOP) study: a randomized controlled trial of the effect of physical activity intervention assessed by

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 11 de 12

pedometer with or without dietary intervention in obese pregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014;210:134.e1–

9. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

53. Palmer KT, Bonzini M, Harris EC, Linaker C, Bonde JP. Work activities and risk of prematurity, low birth weight

and pre-eclampsia: an updated review with meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:213–22. [PubMed] [Full

Text] ꔃ

54. Runge SB, Pedersen JK, Svendsen SW, Juhl M, Bonde JP, Nybo Andersen AM. Occupational lifting of heavy

loads and preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:782–8.

[PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

55. Effects of pregnancy on work performance. Council on Scientific Affairs. JAMA 1984;251:1995–7. [PubMed] ꔃ

56. Waters TR, Putz-Anderson V, Garg A, Fine LJ. Revised NIOSH equation for the design and evaluation of manual

lifting tasks. Ergonomics 1993;36:749–76. [PubMed] ꔃ

57. MacDonald LA, Waters TR, Napolitano PG, Goddard DE, Ryan MA, Nielsen P, et al. Clinical guidelines for

occupational lifting in pregnancy: evidence summary and provisional recommendations. Am J Obstet Gynecol

2013;209:80–8. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

58. Minig L, Trimble EL, Sarsotti C, Sebastiani MM, Spong CY. Building the evidence base for postoperative and

postpartum advice. Obstet Gynecol 2009;114:892–900. [PubMed] [Obstetrics & Gynecology] ꔃ

59. O’Toole ML, Sawicki MA, Artal R. Structured diet and physical activity prevent postpartum weight retention. J

Womens Health (Larchmt) 2003;12:991–8. [PubMed] [Full Text] ꔃ

60. Cary GB, Quinn TJ. Exercise and lactation: are they compatible? Can J Appl Physiol 2001;26:55–75. [PubMed] ꔃ

Copyright December 2015 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 409 12th Street, SW, PO

Box 96920, Washington, DC 20090-6920. All rights reserved.

ISSN 1074-861X

Physical activity and exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Committee Opinion No. 650.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e135–42.

About Us Contact Us Copyright Information Privacy Statement RSS Advertising Opportunities Careers at ACOG

Sitemap

American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists

409 12th Street SW, Washington, DC 20024-2188 | Mailing Address: PO Box 70620, Washington, DC 20024-9998

Copyright 2017. All rights reserved. Use of this Web site constitutes acceptance of our Terms of Use

http://m.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opi…uring-Pregnancy-and-the-Postpartum-Period?IsMobileSet=true 22/02/17 14H14

Página 12 de 12

You might also like

- Exercise and Sporting Activity During Pregnancy: Evidence-Based GuidelinesFrom EverandExercise and Sporting Activity During Pregnancy: Evidence-Based GuidelinesRita Santos-RochaNo ratings yet

- Preconception Lifestyle- Habits to Adopt for a Healthy PregnancyFrom EverandPreconception Lifestyle- Habits to Adopt for a Healthy PregnancyNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and The Postpartum PeriodDocument11 pagesPhysical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and The Postpartum Periodfariska amanizataNo ratings yet

- SMA Position Statement - Exercise in Pregnancy and - 220328 - 132739Document9 pagesSMA Position Statement - Exercise in Pregnancy and - 220328 - 132739bhuwan choudharyNo ratings yet

- ACTIVE-PREGNANCY-GUIDE-2023Document65 pagesACTIVE-PREGNANCY-GUIDE-2023Nuno RobertoNo ratings yet

- Exercise in PregnancyDocument7 pagesExercise in PregnancynirchennNo ratings yet

- 16-Full Paper (Without Author Information) - 102-1!4!20220302Document20 pages16-Full Paper (Without Author Information) - 102-1!4!20220302anjar ratihNo ratings yet

- Beneficios Del Ejercicio en La Mujer EmbarazadaDocument12 pagesBeneficios Del Ejercicio en La Mujer EmbarazadaRitaNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity During Pregnancy Past and Present: Miriam Katz, MDDocument5 pagesPhysical Activity During Pregnancy Past and Present: Miriam Katz, MDAnisNo ratings yet

- Exercise in PregnancyDocument6 pagesExercise in Pregnancymari netaNo ratings yet

- ACSM Exercise PregDocument2 pagesACSM Exercise PregVenugopal KadiyalaNo ratings yet

- The Best Way to Improve Health is Not Just Daily ExerciseDocument4 pagesThe Best Way to Improve Health is Not Just Daily ExerciseAlbert MuthomiNo ratings yet

- Bibliography Gestational DiabetesDocument3 pagesBibliography Gestational Diabetesregina.ann.gonsalvesNo ratings yet

- Exercise in PregnancyDocument2 pagesExercise in PregnancyAdvanced PhysiotherapyNo ratings yet

- E N A W M D P: Xercise, Utrition, ND Eight Anagement Uring RegnancyDocument9 pagesE N A W M D P: Xercise, Utrition, ND Eight Anagement Uring RegnancyRinda KurniawatiNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity Guidelines for Pregnant and Postpartum WomenDocument34 pagesPhysical Activity Guidelines for Pregnant and Postpartum WomenDavid Montoya DávilaNo ratings yet

- Mrs. Hannah Rajsekhar P. Sumalatha: BackgroundDocument6 pagesMrs. Hannah Rajsekhar P. Sumalatha: BackgroundKinjal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Exercise During Pregnancy: A Comparative Review of GuidelinesDocument7 pagesExercise During Pregnancy: A Comparative Review of GuidelinesYekkit TinitanaNo ratings yet

- Gfi Course Manual 07 PDFDocument26 pagesGfi Course Manual 07 PDFLouis Trần100% (1)

- Health and Fitness Final Paper 341 WordsDocument9 pagesHealth and Fitness Final Paper 341 WordsCYNTHIA WANGECINo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 PATHFIT 1Document17 pagesChapter 2 PATHFIT 1Gerald ElaugosNo ratings yet

- Effectivenes of PA Interventions On Pregnancy Related Outcomes Among Pregnant Women Systematic Review 42 OldDocument42 pagesEffectivenes of PA Interventions On Pregnancy Related Outcomes Among Pregnant Women Systematic Review 42 OldAisleenHNo ratings yet

- ExerciseDocument2 pagesExerciseyamanya.mlmNo ratings yet

- Maternal Dietary Intake and Physical Activity Habits During The Postpartum Period: Associations With Clinician Advice in A Sample of Australian First Time MothersDocument10 pagesMaternal Dietary Intake and Physical Activity Habits During The Postpartum Period: Associations With Clinician Advice in A Sample of Australian First Time MothersEva MulifahNo ratings yet

- ACOG Guidelines For Exercise During PregnancyDocument13 pagesACOG Guidelines For Exercise During Pregnancypptscribid100% (1)

- Guidelines of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists For Exercise During Pregnancy and The Postpartum PeriodDocument8 pagesGuidelines of The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists For Exercise During Pregnancy and The Postpartum PeriodDanaSkullyNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Exercise in PregnancyDocument4 pagesLiterature Review Exercise in Pregnancyc5nj94qn100% (1)

- Fit For LifeDocument22 pagesFit For LifeAniruddh448150% (2)

- Rehabilitation of The Postpartum Runner: A 4-Phase ApproachDocument14 pagesRehabilitation of The Postpartum Runner: A 4-Phase ApproachRichard CortezNo ratings yet

- Pe and Health 11Document139 pagesPe and Health 11Santos Jewel100% (3)

- Exercise For Fitness Lesson 1Document5 pagesExercise For Fitness Lesson 1Wendilyn PalaparNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity and Maternal Obesity: Cardiovascular Adaptations, Exercise Recommendations, and Pregnancy OutcomesDocument6 pagesPhysical Activity and Maternal Obesity: Cardiovascular Adaptations, Exercise Recommendations, and Pregnancy OutcomesΑχιλλέας ΚκκκκκκκκNo ratings yet

- Exercise DuringpregnancyDocument57 pagesExercise Duringpregnancysattala_1No ratings yet

- Menopause ExerciseDocument8 pagesMenopause ExerciseWittapong SinsoongsudNo ratings yet

- Effects of Circuit Training on Health Fitness of B.Ed. StudentsDocument24 pagesEffects of Circuit Training on Health Fitness of B.Ed. StudentsBilisuma MuletaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Postnatal Rehabilitation BRIEFDocument1 page2014 Postnatal Rehabilitation BRIEFsalva1310No ratings yet

- Exercise During Pregnancy GuidelinesDocument8 pagesExercise During Pregnancy GuidelineszazaregazaNo ratings yet

- Canadian Academy of Sports Medicine PregnancyPositionPaperDocument3 pagesCanadian Academy of Sports Medicine PregnancyPositionPapernirchennNo ratings yet

- Prescription of Resistance Training For Healthy PopulationsDocument12 pagesPrescription of Resistance Training For Healthy PopulationsChristine LeeNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy and Exercise: Benefits, Precautions and RecommendationsDocument25 pagesPregnancy and Exercise: Benefits, Precautions and RecommendationsBindu PhilipNo ratings yet

- A Cross-Sectional Survey of Australian Womens PerDocument43 pagesA Cross-Sectional Survey of Australian Womens PerMauricio CastroNo ratings yet

- Importance of physical activity, diet and exerciseDocument3 pagesImportance of physical activity, diet and exerciseNeniruth C. MaguensayNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Senam NifasDocument13 pagesJurnal Senam NifasRosi Yuniar RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Exercise PhysiologyDocument27 pagesExercise PhysiologyJericho PanisNo ratings yet

- Exercise Guidelines in Pregnancy: New PerspectivesDocument17 pagesExercise Guidelines in Pregnancy: New PerspectivesHeidy Bravo RamosNo ratings yet

- ENCL 2 Pregnancy-Postpartum PT GuidebookDocument33 pagesENCL 2 Pregnancy-Postpartum PT Guidebookleal thiagoNo ratings yet

- Financial Impact of A Comprehensive Multisite Workplace Health Promotion ProgramDocument7 pagesFinancial Impact of A Comprehensive Multisite Workplace Health Promotion ProgramGaurav SharmaNo ratings yet

- DiabetesasiaDocument13 pagesDiabetesasiadiabetes asiaNo ratings yet

- SPEAR 3 - CE 2A Donato A.Document5 pagesSPEAR 3 - CE 2A Donato A.Shesa Lou Suan ViñasNo ratings yet

- EmPower Physical Activity Guide PDFDocument136 pagesEmPower Physical Activity Guide PDFjha.sofcon5941No ratings yet

- Physiotherapy in The Planning Stage, During Pregnancy and The Post-Natal Period in Cystic FibrosisDocument4 pagesPhysiotherapy in The Planning Stage, During Pregnancy and The Post-Natal Period in Cystic FibrosisKuli AhNo ratings yet

- BPTH 322 Physiotherapy in Physical Fitness: Drusilla Asante Dasante@uhas - Edu.gh Lecture 8 & 9Document62 pagesBPTH 322 Physiotherapy in Physical Fitness: Drusilla Asante Dasante@uhas - Edu.gh Lecture 8 & 9michael adu aboagyeNo ratings yet

- HOPE 1 Module 1 (Exercise For Fitness)Document15 pagesHOPE 1 Module 1 (Exercise For Fitness)Jaslem KarilNo ratings yet

- Exercise For Special Populations 2nd Edition Ebook PDFDocument61 pagesExercise For Special Populations 2nd Edition Ebook PDFdavid.leroy848100% (42)

- Need, Importance and Benefits of Exercise in Daily Life: Aafid GulamDocument4 pagesNeed, Importance and Benefits of Exercise in Daily Life: Aafid GulamRechelle MarmolNo ratings yet

- Module 1 Introduction To Physical Activity and FitnessDocument34 pagesModule 1 Introduction To Physical Activity and Fitnessalisa leyNo ratings yet

- EXERCISE SCIENCE PRINCIPLES FOR FITNESSDocument5 pagesEXERCISE SCIENCE PRINCIPLES FOR FITNESSShivamNo ratings yet

- Module 10 ExerciseDocument9 pagesModule 10 Exerciselyca delaminoNo ratings yet

- What Is A Women Health PhysiotherapistDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Women Health PhysiotherapistHadia bilal KhanNo ratings yet

- Currie2013 PDFDocument12 pagesCurrie2013 PDFheningdesykartikaNo ratings yet

- Is Vitamin D Supplementation Useful For Weight LosDocument10 pagesIs Vitamin D Supplementation Useful For Weight LosAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- Abdul Wahid 2019Document40 pagesAbdul Wahid 2019André MesquitaNo ratings yet

- Rosti Otaj 2014Document118 pagesRosti Otaj 2014André MesquitaNo ratings yet

- s12891 019 2796 5 PDFDocument22 pagess12891 019 2796 5 PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Movement Tempo During Resistance PDFDocument23 pagesThe Influence of Movement Tempo During Resistance PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- PIIS1701216316303103Document12 pagesPIIS1701216316303103Yesica PerezNo ratings yet

- Rietberg 2005Document35 pagesRietberg 2005André MesquitaNo ratings yet

- Some Types of Exercise Are More Effective Than Others in People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Network Meta-AnalysisDocument11 pagesSome Types of Exercise Are More Effective Than Others in People With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Network Meta-AnalysisRukawa RyaNo ratings yet

- Is There Any Non-Functional Training? A Conceptual Review: October 2021Document28 pagesIs There Any Non-Functional Training? A Conceptual Review: October 2021André MesquitaNo ratings yet

- The Association Between Physical Activity and MentDocument15 pagesThe Association Between Physical Activity and MentAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- Two Brain Business Online TrainingDocument6 pagesTwo Brain Business Online TrainingAndré Mesquita100% (1)

- The Influence of Movement Tempo During Resistance PDFDocument23 pagesThe Influence of Movement Tempo During Resistance PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- s12891 019 2796 5 PDFDocument22 pagess12891 019 2796 5 PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- 2.ultimate Muscle Up Development WODDocument1 page2.ultimate Muscle Up Development WODAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- Whey Protein Supplementation During ResiDocument15 pagesWhey Protein Supplementation During ResiAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- EIM - RX For Health - Staying Active During Coronavirus Pandemic PDFDocument2 pagesEIM - RX For Health - Staying Active During Coronavirus Pandemic PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- Body Reading For BegginersDocument6 pagesBody Reading For BegginersRoxana NeculaNo ratings yet

- WODprep's Ultimate 7-Step Shoulder Warm UpDocument24 pagesWODprep's Ultimate 7-Step Shoulder Warm UpAhmed Ibrahim Elkomey100% (1)

- 2 Specific Stabilisation Exercise For Spinal and Pelvic PainDocument10 pages2 Specific Stabilisation Exercise For Spinal and Pelvic Painbarros6No ratings yet

- Carpal Tunnel PDFDocument7 pagesCarpal Tunnel PDFAnonymous hvOuCjNo ratings yet

- An Experimental Pain Model To Investigate The Specificity of PDFDocument6 pagesAn Experimental Pain Model To Investigate The Specificity of PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- The RKC Book of Strength and ConditioningDocument230 pagesThe RKC Book of Strength and ConditioningBence Kovács100% (27)

- Monografia Raul Oliveira (2006) - Scouting PDFDocument115 pagesMonografia Raul Oliveira (2006) - Scouting PDFAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- 2017 12 01 - MacLifeDocument100 pages2017 12 01 - MacLifeAndré MesquitaNo ratings yet

- The 2015 OSDUHS Mental Health and Well-Being Report Executive SummaryDocument11 pagesThe 2015 OSDUHS Mental Health and Well-Being Report Executive SummaryCityNewsTorontoNo ratings yet

- Pelvic Floor Physiotherapy HOACllDocument9 pagesPelvic Floor Physiotherapy HOACllEsteban CayuelasNo ratings yet

- Etec 500 Assignment 2b Final Draft - Research Analysis and CritiqueDocument11 pagesEtec 500 Assignment 2b Final Draft - Research Analysis and Critiqueapi-127920431No ratings yet

- Importance of Physical ActivityDocument28 pagesImportance of Physical ActivityRio TomasNo ratings yet

- Etextbook 978 1451176728 Acsms Introduction To Exercise Science Second EditionDocument61 pagesEtextbook 978 1451176728 Acsms Introduction To Exercise Science Second Editionroger.newton507100% (37)

- Large Analysis and Review of European Housing and Health Status (LARES)Document48 pagesLarge Analysis and Review of European Housing and Health Status (LARES)Hubert Gamarra SanchezNo ratings yet

- DLL Mapeh May 29 June 2 2023Document3 pagesDLL Mapeh May 29 June 2 2023Cezar John SantosNo ratings yet

- Hildebrandt 2000 PDFDocument12 pagesHildebrandt 2000 PDFAlexandre FerreiraNo ratings yet

- CHC50113 Diploma of Early Childhood Education and CareDocument14 pagesCHC50113 Diploma of Early Childhood Education and CareSandeep KaurNo ratings yet

- Omnibus Health Guidelines For The Elderly 2022Document81 pagesOmnibus Health Guidelines For The Elderly 2022Raymunda Rauto-avila100% (1)

- Validation of The Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire Class PDFDocument11 pagesValidation of The Godin Leisure-Time Exercise Questionnaire Class PDFKishenthi KerisnanNo ratings yet

- 5 Individualized Fitness ProgramDocument51 pages5 Individualized Fitness ProgramJevbszen RemiendoNo ratings yet

- Breaking Down Barriers To Fitness: Here Are Some of The More Common Barriers and Solutions For Overcoming ThemDocument1 pageBreaking Down Barriers To Fitness: Here Are Some of The More Common Barriers and Solutions For Overcoming ThemNiko ChavezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Example Physical EducationDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Example Physical Educationbzknsgvkg100% (1)

- Brochure PA Guidelines - A5 - 13-17yrs PDFDocument8 pagesBrochure PA Guidelines - A5 - 13-17yrs PDFJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- Cool Azul Sports GelDocument1 pageCool Azul Sports GelroslizamhNo ratings yet

- Pathfit 2 Unit 1 1Document19 pagesPathfit 2 Unit 1 1eljieolimba883No ratings yet

- Health Optimizing Physical Education-Quarter 4 (Module 4)Document6 pagesHealth Optimizing Physical Education-Quarter 4 (Module 4)Shanghai Ni Yoshinori100% (1)

- Fitt Final ExamDocument1 pageFitt Final ExamJohn ParrasNo ratings yet

- PE Coursework Guidelines BookletDocument200 pagesPE Coursework Guidelines BookletNambiNo ratings yet

- Letter To Legislator AssignmentDocument5 pagesLetter To Legislator Assignmentapi-638539712No ratings yet

- Optimizing Exercise and Physical Activity in Older PeopleDocument356 pagesOptimizing Exercise and Physical Activity in Older PeopleNimouzha Imho100% (1)

- Join Health and Fitness Events to Increase Physical Activity and AdvocacyDocument2 pagesJoin Health and Fitness Events to Increase Physical Activity and AdvocacyBenedict LumagueNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity Guidelines For Americans: Executive SummaryDocument7 pagesPhysical Activity Guidelines For Americans: Executive SummaryBenNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: A Brief To SupportDocument8 pagesPhysical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: A Brief To SupportPhilippe Ceasar C. BascoNo ratings yet

- Mastered and Least Mastered MAPEH CompetenciesDocument4 pagesMastered and Least Mastered MAPEH CompetenciesLyza SuribenNo ratings yet

- Physical Education (Hope 3) Grade 12Document2 pagesPhysical Education (Hope 3) Grade 12Lei DulayNo ratings yet

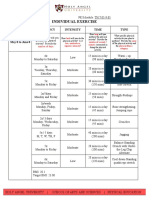

- Medical Conditions Frequency Intensity Time Type Progression Red Flags or Special ConsideratrionsDocument4 pagesMedical Conditions Frequency Intensity Time Type Progression Red Flags or Special ConsideratrionsClaire Madriaga GidoNo ratings yet

- Tos Mapeh 10 Second QuarterDocument2 pagesTos Mapeh 10 Second Quarterlee100% (3)

- Presentation HowtoorganizeSPORTSCLUBDocument104 pagesPresentation HowtoorganizeSPORTSCLUBThem poll CeloricoNo ratings yet