Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Significance of Studying and Investigating Art Crime - Old Reasons, New World B. Dobovšek & B.Slak's 2

Uploaded by

anaueneOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Significance of Studying and Investigating Art Crime - Old Reasons, New World B. Dobovšek & B.Slak's 2

Uploaded by

anaueneCopyright:

Available Formats

VARSTVOSLOVJE,

Journal of Criminal

Justice and Security

The Significance of Studying

year 13

no. 4 and Investigation Art Crime:

Old Reasons, New World

pp. 392-405

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

Purpose:

The purpose of this paper is to demonstrate the basic importance of studying

and investigating art crime.

Design/Methods/Approach:

This paper presents a literature review with new commentary.

Findings:

Art crime has a long history and there has been some good research done

on the topic. However it is still unrecognised in broader circles, even among

professionals, and only a portion of the importance of art crime has been studied,

o en without a strong analysis of the complexities of the field. This paper will seek

to fill in some of the gaps in scholarship, while summarizing much of the available

literature.

Research limitations/implications:

A lack of proper and comprehensive academic literature limits the extent of

this study, but this is the very reason why this paper is important.

Practical implications:

This paper represents a summary of the significance of art crime studies and

investigation.

Originality/Value:

The main value is to those who are not yet familiar with art crime. This paper

will further bring in some new views to complement the existing scholarship, and

will be of interest to those who are keen on knowing about art crime.

UDC: 343.3/.7

Keywords: art crime, insurance premiums, looting, war art crime, organised crime,

money laundering, corruption

Zakaj je pomembno kriminalistično preiskovanje in akademsko razisko-

vanje kaznivih dejanj povezanih z umetninami: stari razlogi v sodobnem

svetu

Namen prispevka:

Namen prispevka je pravzaprav prikazati osnovne, a pomembne razloge za

preučevanje in preiskovanje z umetninami povezanih kaznivih dejanj.

392

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 392 9.1.2012 6:21:15

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

Metode:

Pregled literature z dodatnim komentarjem.

Ugotovitve:

Kazniva dejanja v povezavi z umetninami imajo dolgo zgodovino in zatorej je

bilo do sedaj narejenih nekaj dobrih raziskav. A kljub temu pomembnost preiskovanja

in raziskovanja tovrstne kriminalitete ostaja neprepoznana pri širši populaciji pa

tudi med strokovnjaki. Le del celotnega spektra tovrstne kriminalitete je bil vzet

pod drobnogled, pa še to pogosto brez močne (empirične) analize kompleksnosti

področja. Ta prispevek bo skušal zapolniti te nekatere vrzeli različnih spektrov

pomembnosti preko pregleda dosegljive literature.

Omejitve/uporabnost raziskave:

Pomanjkanje ustrezne in celovite akademske literature omejuje argumentacijo,

vendar pa je ta isti razlog pravzaprav vzrok temu prispevku.

Praktična uporabnost:

Prispevek prinaša povzetek razlogov za kriminalistično preiskovanje in

akademsko raziskovanje z umetninami povezanih kaznivih dejanj.

Izvirnost/pomembnost prispevka:

Prispevek bo najbolj uporaben za tiste, ki še niso seznanjeni s tovrstno

kriminaliteto. Prinaša pa tudi nekaj novih pogledov k že obstoječim zbirkam

znanja in bo zatorej v korist tudi tistim, ki že imajo določeno znanje s področja

obravnavane tematike.

UDK: 343.3/.7

Ključne besede: z umetninami povezana kazniva dejanja, zavarovalne premije,

plenjenje, vojni zločini, organizirana kriminaliteta, pranje denarja, korupcija

1 DEFINING ART CRIME

Assessing the significance of art crime investigation must by all means start with

a definition of art crime. Here of course, we have a problem in that some experts

would argue that this typology of crime is too broad to properly define. The term

“art crime” shares an integrated notation of its subject of definition. Similar to art,

where every piece of art can and is interpreted by any individual differently and

yet similarly (i.e. agreeing that a picture is abstract, yet disagreeing as to what

it represents), art crime is similarly ambiguous. The artefact in question may not

have a practical value, like a television, but it may be difficult to define whether the

object constitutes art, décor, or cultural heritage. In avoidance of those typological

problems, the term “art crime” hierarchically prevails upon all crimes and unites

the crime wherein the artefact in question is a one that may be termed “cultural

heritage”, one of modern art, medieval art, or other such periods. Art crime is

similarly described by Durney and Proulx (2011) or Passas and Proulx (2011: 52),

when they state that “subsumed under the rubric of art crime are such activities as diverse

as art the s and confiscations, vandalism, faked and forged art, illicit excavation and

export of antiquities and other archaeological materials.” Art crime therefore includes

all “criminally punishable acts that involve works of art” (Conklin, 1994: 3). In general,

393

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 393 9.1.2012 6:21:15

The Significance of Studying and Investigation Art Crime: Old Reasons, New World

we might state that this combines all artefacts that hold more characteristics of

sentimental and social value than of practical value. We must, however, keep in

mind that practical value changes through time. Antiques swords and paintings

may have had practical value when they were first created (swords for combat

and painting for sacral or documentary purposes). Of course we cannot judge and

characterise an item as being artefact of art by the sole purpose of practicality. Art

must have some consensual approval and has to be seen as art by some broader

scope of the population. Art is therefore irreproducible and has in its practicality

artistic characteristics (Mole in Dobovšek & Škrbec, 2007).

Even then, a er an artefact has been consensually designated as an artefact

of art, there can be terrible inconsistencies in the opinion of the expert witnesses,

who are sometimes called upon to testify on a work’s originality, damage, worth

etc. As seen in the cases of art the s, gathered and described by Esterow (1967),

these inconsistencies prolong and complicate trials, especially in Anglo-‐‑American

judicial systems, where jury and judges have limited knowledge of art.

2 DIFFERENT ASPECTS OF SIGNIFICANCE: WHY ART CRIME

SHOULD BE INVESTIGATED AND STUDIED

The investigation of art-‐‑related crime should not be of prevailing interest to one

region or country, rather it should be more than just thought of interest to almost

every county in world. There is no nation that is without cultural heritage or

culture-‐‑specific art.

2.1 The Matter of Value

No ma er how developed the country or where on the world map it is located,

a nation’s art is of enormous value. Values of art are o en ascribed to two points:

monetary or social-‐‑sentimental.

In the first case, the value of art is measured by the amount of money for

which it is purchased. Here we come across two worlds, one of the legal trade,

and one of the illegal one. Prices of artefacts in illegal interactions can be higher

or lower (in case of money laundering) than on one of the legal markets. Even

though it seems that there is an agreement that illegal cultural trafficking (note that

this includes all forms of art, not just paintings but all cultural artefacts) is about

second largest criminal trade, first being drug trafficking (Conklin, 1994; Gilgan in

Lane, Bromley, Hicks, & Mahoney, 2008). Here we do encounter some problems

with confirming this, for the monetary value of art is never fixed (Passas & Proulx,

2011: 60). As Durney and Proulx (2011) discuss this statement of art crime being

the second largest market, by quoting Interpol’s FAQ (2011) response, that there is

no data that could corroborate that sort of statement. Being true or not, the value

is still extremely high.

In addition to the (i)llegal market value there is what Durney and Proulx

(2011: 126) describe as a motivational multi-‐‑faceted value because the value of art is

394

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 394 9.1.2012 6:21:15

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

multi-‐‑faceted and differs for a buyer, a seller, an archaeologist, an insurer, an auctioneer, an

art historian, a gallery owner, and even a thief all have different assessments of the worth of

an artwork (Massy in Durney & Proulx, 2011: 216).

In the second case we mentioned, social-‐‑sentimental value is measured by the

originality and rarity or uniqueness of the artefact in question. This sentimental

a ribute of artefacts can be on a micro level, where artefacts have sentimental

value only to the owner (most o en these are works in private collections) or

on a macro level, in which case the artefacts represent the cultural heritage and

society itself, wherein the society collectively feels some sentimentality towards

the artefacts. In a pilot research project, conducted by Dobovšek and Škrbec (2007),

respondents were asked to express their opinions on a 5-‐‑point scale on the severity

of crime types – damaging cultural heritage is seen as the most serious, compared

to stealing artefacts from a river or seabed, spraying public sculpture with paint,

possessing a stolen picture (with the knowledge that it was stolen), stealing a

painting from a national gallery, damaging public sculpture or art, and taking

that piece for “personal memory”, vandalism, and art trafficking. More serious

than damaging cultural heritage was the international trade in weapons or drugs

trafficking, terrorism and human trafficking.

These two aforementioned reasons are not miles a part, because as Smith (in

Conklin, 1994: 7) says, the value of art isn’t intrinsic, it’s socially constructed. Also

these two main points are important enough that art-‐‑related crime should be taken

seriously. However they also stand for a foundation of several more unnoticed

sociological, criminological and criminalistic rationales for devoting more a ention

towards art related crime, to which we now turn.

2.2 When Art Means More

From a sociological point of view art, especially artefacts related to cultural

heritage, represents a form of informational bond between the past and the present,

enabling a form of cultural identification (Samardžić, 2010; Passas & Proulx, 2011).

Suro (in Conklin, 1994) and Wilkerson (in Conklin, 1994) give the example of the

lost cultural identity and personal grief of people residing in an area from which a

cultural artefact was stolen. For example we might consider the disappearance of a

painting used in community rituals, or sculptures of religious importance.

Individual pieces of art that gain extreme publicity and recognition can

transform from works of art into cultural icons (Brisman, 2011: 20). And such high

recognition can lead to tourist a ractions – making museums and cultural heritage

sites into overnight tourist destinations, thereby helping the economy of the country

in question (Durney & Proulx, 2011). Art is sometimes used by corporations or

individuals to improve their public image (Naylor, 2008). This pedestal on which

art sits causes a world-‐‑wide perception that art can be beneficial to mankind – all

leading to the special treatment of art creators, sellers, buyers, and possessors. Tax

write-‐‑offs are one example (Naylor, 2008). Interesting are Brisman’s (2011) thoughts

on art crime, stating that when an artwork is stolen, vandalised or in some other

form “victimised”, the meaning of the work changes. Other a ributes are ascribed

395

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 395 9.1.2012 6:21:15

The Significance of Studying and Investigation Art Crime: Old Reasons, New World

to it – now it is more famous because of the the or because of the vandalism, now

it has more meaning, because it was changed through the act of vandalism.

Greater intake of the sociological view of art is o en (ab)used by (counter)

intelligence agencies, most o en in war-‐‑time, when art is used as an indirect

means of warfare. The cultural space and intellectualism is seemingly a sort of war

front, where specific art styles try to dominate one another. This “trend” began in

ancient times, when conquerors destroyed the cultural heritage of the conquered

nation as a means of emphasising their strength (Gerstenblith, 2009: 19). Art is

therefore another ba leground, where wining is as importance as it is in armed

conflicts. Also art is being used as anti-‐‑propaganda (Saunders, 1999; Wilford, 2008;

Naylor, 2008) and sometimes art was (and still is) used as a diversionary tactic.

Most notably this was seen during Cold War era (Saunders, 1999; Wilford, 2008).

It seems that intelligence agencies gave or intended to give substantial funds to

cultural and art events (for art its self, or to art as a front, a diversion for other

activities). Some anecdotal rumours about such diversions appear even in 1914,

when the Germans and the French where close to entering into a conflict over

Morocco. But just then, the Mona Lisa was stolen from Louvre (Esterow, 1967) -‐‑

without a doubt, the a ention of the French was refocused (McLeave, 1981). As it

was later discovered the the of Mona Lisa was not intended as a diversion, it was

more an act of patriotism (Esterow, 1967; McLeave, 1981).

2.3 Art and Crime

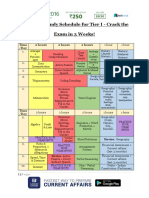

We can use deferent categories by which to divide art crime into several different

groups or types of crimes against art. The following scheme shows these

categories.

All of the listed crimes (Figure 1), except for the last one, have one thing in

common -‐‑ art is the primary target of the act. Only when regarding those acts in

greater detail do we discover the complexity of art crime, and the even greater

partition of art crimes. The best example of this is the from archaeological site,

which could be done by an archaeologist, residents of nearby se lements (Lane

et al., 2008), organised criminal groups (Bowman, 2008), tourists, and so on.

Vandalism also is a good example as Brisman, (2011: 6) notes that vandalism can

take the form of performance art—when one artist a acks the work of another

artist with vandalism as a medium of expression, rather than as a mere example of

hooliganism. Here the question of graffiti arises. Can graffiti be considered a work

of art, or is it an act of vandalism? What does graffiti hide in its sub-‐‑context and

who is indirectly responsible for graffiti (D’Amico & Block, 2007)?1 Art crime is

therefore extremely complex. Further a ention should be devoted to all subtypes

of art crime, because as of now, most of the researchers either research art crime in

1 D’Amico & Block, (2007) do give all the answers to those questions, representing the graffitists in

a totally different light, showing a graffiti artist as an artist who sometimes engages in a just war.

Graffiti that is predominantly painted on governmental and public property are not always acts of

vandalism, as public areas are in the ownership of all, and so artistic expression should be allowed

(as the place was also built with public money).

396

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 396 9.1.2012 6:21:16

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

Figure 1:

Categorisation

of art crime

types, including

Conklin’s (1994)

categorisation

types of

vandalism and

the s.

general (as we do in this article) or they focus primarily on interesting cases. Art

the and forgery are of more interest than other types. War-‐‑time crimes differ from

other crimes because in war there is less formal control, and previously punishable

acts are now “morally acceptable”. The same might be said for instances of public

disorder, when looters receive strong localized social support (Quarantelli &

Dynes, 1968). A soldier perhaps in his civil life would not show such behaviour,

and would even condemn it. War looting has existed as long mankind has existed,

with most the notable example during World War Two, when Nazis were able

to obtain thousands of looted treasures (McLeave, 1981). War-‐‑time art crime can

have low or high magnitude (“low” describing acts of greed by a soldier, while

“high magnitude” may be seen through orders of high command, like Napoleon’s

or Hitler’s idea of cultural capital in their homelands). There can also be strategic

destruction of cultural heritage as a tactic for lowering the morale of the enemy,

or as part of the final war agenda, such as ethnic cleansing in the Balkan region

where churches and mosques, as well as symbols of ethnic diversity and cultural

history, such as the ancient Roman city of Dubrovnik, the Sarajevo Library, and the

Neretva Bridge in Mostar were targeted (Gerstenblith, 2009: 25).2 War-‐‑time looting

continues in present times, where the primary victims are the cultural treasures

of Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan. Here a sort of hypocrisy and mixture of all war art

crime types occurs. Terrorist cells sell their own cultural art (and other art in their

possession), those acts being permissible as the money goes to support Jihad or

other terrorist activities.3 Occupying soldiers unfortunately also loot, however their

2 Gerstenblith, (2009: 29) also notes that when there was a trial for war crimes in this region, nota-

tion of crime against cultural heritage were included and “the first defendant, Pavle Strugar, was

convicted in 2005 for the intentional a ack on the Old Town of Dubrovnik, a World Heritage Site,

as well as for other war crimes”.

3 Terrorists and art have one more thing in common. Besides selling cultural artefacts to finance their

acts, those very acts can damage the art and the cultural heritage of the nation under a ack. Such

danger is expressed by Hill (2008), referring to the threat of terrorists a acking the 2012 London

Olympics.

397

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 397 9.1.2012 6:21:16

The Significance of Studying and Investigation Art Crime: Old Reasons, New World

acts are not officially permissible. Local residents can seldom know who robbed

them of their heritage (terrorists or occupying soldiers). Recruiting future terrorists

becomes easier when there is “proof” that the occupying forces are trying to rob

locals of their history, even though the thief did not always come from beyond the

borders. Similar consequences in lower morale and unethical behaviour that may

result in looting and the s may be found when locals take advantage of the chaos

that follows natural disasters or riots – a more and more frequent occurrence these

days.

Looting by itself is also a complex phenomenon, gaining strength in silent

approval and from the cooperation of many notable collectors and museums, who

accept artefacts without proper provenance, sometime even openly knowing their

illegal origin (Conklin, 1994; Bowman, 2008; Lane et al., 2008; Samardžić, 2010; Urice,

2010; Manacorda & Chappell, 2011). Going a step further, there are now instances

when museums have hidden artefacts until the end of the statute of limitations for

their recovery has past (ibid.). All this influences the whole experience of visiting

cultural places and raises a number of legal questions (Urice, 2010), investigative

questions, and of course broader social ones (Lane et al., 2008), such as how one can

claim to support culture while admiring stolen artefacts at a museum?

The looting of archaeological sites is o en done by those who are struggling to

survive, or just want to earn some extra money (Bowman, 2008). Here again it may

be seen that the only victim of the looting of archaeological sites is our history.

Looting crimes have an interesting criminological nature, specifically in that

looting archaeological sites is a form of a “victimless crime”.4 Sometimes when

artefacts are stolen from museums or private collections, the general public or

investigators don’t show interest in the ma er, due to the classist assumption

that the art world is the realm of the elitist “high class”, and that it is therefore

not of significant import to the wider public (Charney, 2009; Durney & Proulx,

2011). The general population assumes that “normal hard-working people would not

spend their hard-‐‑earned money for such overvalued objects.”5 This results in the lack of

informational flow that would help investigations, and is now helping traffickers

to more easily persuade Customs personnel to become complicit in the crime,

because “a er all, the person whose artefact was stolen can afford another one.” Art crime

in general isn’t popular or interesting for the wider masses. This is most reflected

in low media coverage of art crime, only reporting about high profile cases (when

a famous person or artefact is involved), and by doing so the media continues to

shape an improper perception of art crime (Dobovšek, Charney, & Vučko, 2009).

Hollywood with its portrayal of glamorous art thieves in the form of Thomas

Crown and the like further influences that improper perception (Durney & Proulx,

2011). Lack of proper press releases of course does not help in the investigation of

art crime, where investigators need public assistance.

4 Not to mention that these looted artefacts are not catalogued, described, or in any other way docu-

mented – all of which makes the investigation and prosecution of such crimes extremely difficult

(Conklin, 1994; Bowman, 2008; Durney & Proulx, 2011).

5 This was empirically confirmed in Dobovšek and Škrbec (2007) wherein respondents admi ed that

they would be least affected if a rich collector’s painting is stolen.

398

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 398 9.1.2012 6:21:16

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

From a criminological point of view there are several more aspects to

be considered. Among them is the global safety and well-‐‑being of a specific

population. One example is how art crimes financially affect not just the owners of

the artefacts in question, but also all of us. Aside from the social-‐‑sentimental value,

this factor can be viewed in insurance premiums. When an extremely valuable

artefact is stolen, insurance companies must pay off the insurance. Sometimes the

insurance company may be contacted to pay off a ransom demand for safe return

of the artwork, for the ransom demand may be smaller than the insured value of

the object (Naylor, 2008). We probably will never know how many acts of this kind

are commi ed each year, as the insurance companies, police, and victims of art

the do not always “go public” in fear of inspiring similar criminal acts (McLeave,

1981), or in fear of scaring off investors.6 The capitalistic world in which we live

demands that those insurance or ransom amounts must be regained. Higher

insurance premiums are one of the ways for insurance companies to regain this

lost amount (Kerr, 2010). More financial losses that can affect wider populations

are the effect of thieves resorting to violence against security guards, causing

hospital expenses and time devoted by emergency response units (Conklin, 1994;

Bowman, 2008). Furthermore due to the complexity of art crime, investigations are

o en demanding, drawn out over long and costly periods, transcending borders,

and thereby accumulating cost and time spent on an extended investigation.

Other damages include loss of income from tourism (Durney & Proulx, 2011) and

impairing the whole experience of museum-‐‑going, as every time that an artwork is

stolen or damaged due to lack of security, the owners might feel obliged to engage

in an upgrade of security measures. This sometimes affects the whole experience

of museum visits (Brisman, 2011) – prolonging queues, displaying the artefact in a

manner that thwarts proper admiration, and so on. Conklin (1994) also noticed that

improved security does lead to fewer the s, instead forcing perpetrators to resolve

to daytime robberies using violence, and so increasing the danger for injuries and

loss of life in the commi ing of the crime.

The criminological impact may be seen when noting how art crime correlates

with other types of crime. This correlation can be either direct, with art as a motive/

link to a murder or other violent crime, which might be commi ed in order to

gain possession of an artefact. Secondly there can be a correlation because of the

characteristics of the works in question. This is also one of the prevailing reasons

why art crime should be studied more, as it enables a hidden in plain sight method of

conducting illegal business in various more general delinquency fields.

2.3.1 Correlation with Other Types of Crime

Art crime most is most o en seen connected with organised crime, and where art

or cultural heritage play different roles. Those are:

− When the artefact itself is the interest of the organised crime group, who steals

and then sells the stolen object (Conklin, 1994). Another option is when the

6 Where antiquities collectors refuse to report their stolen artefact because that could alert the countries

from which the antiquity was initially smuggled. Tax evasion is also o en listed as a reason not to

report a the (Conklin, 1994).

399

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 399 9.1.2012 6:21:16

The Significance of Studying and Investigation Art Crime: Old Reasons, New World

criminal group makes a copy of the stolen object, and then sells the forgeries,

holding the original for future replication. Artefacts of cultural heritage are of

interest as well. Cross border trafficking of cultural objects demands organization

and o en involves the illegal removal and exportation of cultural material from

source countries, satisfying the demand generated from developed, rich, market

economies (Alder & Polk in Bowman, 2008).

− Art crime as a means of money laundering, wherein the origin of criminal

money may be blurred (Finckenauer & Voronin in Bowman, 2008; Watson

in Bowman, 2008) when art is purchased. Auctions may also be undertaken

anonymously, with paintings bought with cash, making it an easy situation

by which to launder money. Turkey, for instance, has created a “List of Liable

Persons” that can engage in money laundering, a list that includes banks,

insurance companies, notaries, collectors of historical arts and antiques, as

well as dealers and auctioneers (Türkşen, Mısırlıoğlu, & Yükseltürk, 2011: 291).

Similarly, the United Kingdom acknowledges that the art world is a potential

source of money laundering, and tries to regulate it, to that end, yet in practice

this has been mostly fruitless (Hill, 2008).

− Art as means of corruption: One can sell low-‐‑priced paintings at a high price

and thus disguise the true meaning of the transaction. Alternatively, high-‐‑

valued pictures may be sold for a small amount, or may be given as a gi and

then bought back for the real value (Naylor, 2008; Ou, 2011). “Elegant bribery”

is the Chinese term for using works of art as a medium of corruption. Three

predominant reasons explain why people sometimes use art instead of stocks

or other goods. First, the a ribute of good taste is a factor in addition to gaining

some illegal benefit. The criminal may think that, in involving themselves in

art, he appears to be a man of taste. Second, the constant increase in the value

of art makes it a good investment. Third, it is extremely difficult to trace and

investigate bribery acts that involve works of art (Ou, 2011).

− Illicit art as form of payment is another category to consider, wherein art is

used instead of money for buying drugs (Durney & Proulx, 2011; Naylor, 2008;

Charney, 2009) or weapons.

− Fraud: the motivation for fraud in the art world can be money, but it may also be

revenge (making art dealers and art critics look foolish) (Conklin, 1994), etc.

− Organised crime groups using art for drug and other illegal merchandise

trafficking (art as a container for drug or arms, for example).

Not all of above listed criminal acts are done solely by organised crime.

They can also be commi ed by individuals, usually on a smaller scale. A form of

business crime or basic, general delinquent behaviour, like a drug addict stealing

an artwork as crime of opportunity7 being the best example, and then selling those

items, considerably undervalue, so they can buy drugs. Some art crime researchers

7 Opportunistic art the s seem to be extremely problematic for several reasons. First as Pečar (2002)

noted, opportunity is the main basis for commi ing the crime. This regards all crime, not just art

crime. Low level art the s occur mainly in unsecured, unmonitored facilities (like churches, storage

facilities, and private residences) and o en include poorly documented or undocumented artefacts

(sacral statues or privately-owned paintings that are neither photographed nor inventoried). This

all influences the investigation. Also there is a lack of interest on the part of churches and the ma-

400

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 400 9.1.2012 6:21:16

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

see this as the only correlation with other crimes, heavily disputing art crime’s

connection with organised crime. They argue that aforementioned correlation

is a product of sensationalistic journalism (Naylor, 2008). Tijhuis (2009) further

disclaims these presumptions with his study of 50 solved cases of art the s, in

which organised crime does appears to be involved, however not as extensively

as generally believed. One must take into account that his study focused solely

on solved cases of art the (of which the sample was very small, a fact that he

acknowledges), dismissing antiques looting. We do highly commend his research

and list it as an example for further studies that should follow to further (dis)prove

the relationship between organised crime and art crime. By its very nature, art crime

shares some similarities with organised crime. We might take for instance Gill’s

(2006: 280) definition8 of organised crime, where organised crime may be defined as

the ongoing activities of those collectively engaged in production, supply and financing for

illegal markets in goods and services. Taking into account Gill’s fairly simplistic yet in

all views true definition and combining it with notes from the footnote, we then

discover that rather than speaking of definition, one must speak of characteristics

and of a way of doing things that is shared by art crime and organised crime. This

is best explained in Conklin’s (1994: 3) statement about looting, that: “requires an

elaborate, multi-‐‑layered network of grave-‐‑robbers, middlemen, and dealers”. Forgery also

demands a similar network, as do other types of art crime. As Mackenzie (2011:

69) puts it: “We might therefore suggest that this illicit part of the trade is an example of

‘organised’ crime”.

Hill (2008) sees the risk of future organised crime involvement escalating, such

art crime commi ed by immigration groups that come to the UK. Currently lacking

proper organisation and contacts, as they develop their network, they could be

more interested in art crime. Organised crime therefore does not undertake all of

the aforementioned types of art crime, but it is clear that art crime is sometimes

commi ed by organised crime group.

Varios roles of art noted above in connection with organised crime have one

thing in common: art is bought, sold, shipped, or stolen in order to mask the true

meaning of some other delinquent act, making the real reason (and motive) for the

commission of an “art” crime very hard to find and even harder to prove. We have

seen that this misuse of art was not only discover and done by organised crime but

also by intelligence agencies. This burden of detection and uncovering evidence

when art masks other delinquent behaviour falls on the shoulders of criminal

investigators.

jority of private owners to properly document and secure the artwork in their possession – further

maintaining low security status quo.

8 Here again we collide with problem of non-‐‑unified definition of organised crime as a debate what

actually defines organised crime and to what extend the “organised crime” term expanses and what

form of crimes it comprises is a continuing one (Kregar & Petričušić, 2010).

401

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 401 9.1.2012 6:21:16

The Significance of Studying and Investigation Art Crime: Old Reasons, New World

2.4 For Those Who Investigate Art Crime and Proper Legislation

Throughout this article there have been several notations regarding the problems

of the criminal investigation of art-‐‑related crime (such as the problem of non-‐‑

reporting of crimes, the influence of organised crime, involvement of elite dealers,

etc). And as mentioned before, art crime strongly correlates with other types of

crime. Knowing how to investigate art-‐‑related crime can highly increase the rate

of effectively closing a case, even if the case itself is not of artistic nature and art is

only “collateral damage” rather than the primary victim. This o en happens when

investigation leads to drug addicts who stole art, or in cases of money laundering.

In the first case art is the goal, while in second case, art is the means. Both cases

demand different approaches, and they also demand knowledge about art crime.

The overall problem when dealing with art crime is that, even though experts

agree that this is an important type of crime, globally there isn’t much a ention

paid to this criminal activity. Correspondingly investigators assigned to art

crimes are o en untrained, unqualified and do not have the full support of their

colleagues and managers. Departments that investigate homicide are seen as the

most important and are the desired working place for most investigators, followed

by sex/vice crimes, then the s and burglaries.

Here of course there is a need for proper legislation and art crime prosecution,

to deter those who are connected with organised crime, war-‐‑time art crime

(Gerstenblith, 2009), looting (Urice, 2010), etc.

More support and knowledge are in the hands of insurance investigators. They

also have access to private and sometimes paid databases (like IADAA, PERCELL

or Looted Art). The mere fact that this data is private and more difficult to access

limits the accessibility and benefits of such databases.

And a er all, from a penology standpoint, how we shall punish the perpetrator?

How long of a prison sentence should we give him? Taking into account the worth

of the artefact, the manner in which the criminal act was commi ed. And in the

end, if the artefact was not a piece of art to which the broader community heavily

relates (like “Mona Lisa”), and if it was stolen from a wealthy collector, then the

public will not harshly judge the thief, and the act will be seen by the public as

relatively harmless (like tax evasion).9

Even though barring the heaviest burden, criminal investigators or other

repressive organs on the whole are seen as those who prevent art crime with the

least efficacy, as art crime is so extensive that other institutions and means must be

used as well (Passas & Proulx, 2011). Yet this is true for all types of crime.

3 CONCLUSION

Listing all of the reasons for studying art crime in manner above, does not enable

us to give enough space and form for representing the subject in detail. Yet this

9 To read about the severity and punishment levels of specific types of art crime in the public eye, see

Dobovšek and Škrbec (2007).

402

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 402 9.1.2012 6:21:16

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

could not be done, even if we chose another approach and style of presentation.

As we have discovered, in presenting art crime, we collide with what Durney

and Proulx (2011) have described as a multi-‐‑faceted crime type. Even though one

makes a choice of standpoint in how to approach this subject (a criminological

angle, a cultural one, etc) if one wishes to research art crime, one still encounters

difficulties. Having only anecdotal evidence, having an intrapersonal dilemma of

what to publish, as we do not wish to spread know-‐‑how to criminals, and therefore

make the jobs of the future perpetrators even easier. Although INTERPOL, ALR,

EUROPOL or crime units of Carabinieri, FBI etc. do have extensive lists and data on

crimes commi ed, there is a problem of cross-‐‑border linkage, enabling proper art

crime analysis from those data bases only for a country-‐‑by-‐‑country basis (Durney

& Proulx, 2011). This is also the reason why so few criminologists have studied

art crime, as they rely on statistical data, which is in short supply (Dobovšek et

al., 2009). An international free of charge database, from which scholars could

research, would be beneficial (ibid.). As our title mentioned, the reasons for

studying art crime are old, and yet they reflect differently in modern world, where

globalisation has had a worldwide effect, and stolen art in one corner of the globe

can have a “bu erfly” effect on other part of the world. Reasons of pure monetary

value, in the current age, are set aside as art crime is under scrutiny because of

its role in terrorism and financial delinquency. And yet though the seriousness of

art crime’s involvement with other types of crime is increasing, investigators are

still untrained in art-‐‑related investigations, and are not financed (with exception

of FBI, Scotland Yard, Spain, Belgium, Carabinieri and several other which have

their art crime departments, yet still too few) and most of all those who investigate

o en have a bad reputation, because they are seen as having devoted their time

to a crime type that is not “sexy” in the eyes of police, who consider burglary and

murder to be “actual” crimes, those worth investigating.

It seems that as art o en masks the true motive of some criminal act, so it

unfortunately also “masks” some importance of studying art crime.

REFERENCES

Bowman, B. A. (2008). Transnational crimes against culture: Looting at archaeological

sites and the ‘’grey’’ market in antiquities. Journal of Contemporary Criminal

Justice, 24(3), 225-‐‑242.

Brisman, A. (2011). Vandalizing meaning, stealing memory: Artistic, cultural, and

theoretical implications of crime in galleries and museums. Critical Criminology,

19(1), 15-‐‑28.

Charney, N. (2009). Art crime in context. In N. Charney (Ed.), Art crime: Exploring the

dark side of the art world (pp. xvii-‐‑xxv). Santa Barbara: Praeger/ABC-‐‑CLIO.

Conklin, J. E. (1994). Art crime. Westport: Praeger Publishers.

D’Amico, D. J., & Block, W. (2007). A legal and economic analysis of graffiti.

Humanomics, 23(1), 29-‐‑38.

Dobovšek, B., & Škrbec, J. (2007). Kriminaliteta v zvezi z umetninami v Sloveniji

[Art crime in Slovenia]. Varstvoslovje, 9(3/4), 204-‐‑214.

403

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 403 9.1.2012 6:21:16

The Significance of Studying and Investigation Art Crime: Old Reasons, New World

Dobovšek, B., Charney, N., & Vučko, S. (2009). Art crime archives. The Journal of Art

Crime, 2(1), 25-‐‑34.

Durney, M., & Proulx, B. (2011). Art crime: A brief introduction. Crime, Law and Social

Change, 56(2), 115-‐‑132.

Esterow, M. (1967). The art stealers. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Gerstenblith, P. (2009). Archaeology in the context of war: Legal frameworks for

protecting cultural heritage during armed conflict. Archaeologies: Journal of the

World Archaeological Congress, 5(1), 18-‐‑31.

Gill, P. (2006). Organized crime. In E. McLaughlin, & J. Muncie (Eds.), The Sage

dictionary of criminology. London: Sage.

Hill, C. (2008). Art crime and the wealth of nations. Journal of Financial Crime, 15(4),

444-‐‑448.

INTERPOL FAQ. (2011). Retrieved October 17, 2011, from h p://www.interpol.int/

Crime-‐‑areas/Works-‐‑of-‐‑art/Frequently-‐‑asked-‐‑questions

Kerr, J. (2010). Presentation at international conference “Art Crime Investigation”.

Ljubljana, Faculty of Criminal Justice and Security, 13-‐‑14 October, 2010.

Kregar, J., & Petričušić, A. (2010). Crime as a business, business as a crime.

Varstvoslovje, 12(4), 367-‐‑377.

Lane, D. C., Bromley, D. G., Hicks, R. D., & Mahoney, J. S. (2008). Time crime: The

transnational organization of art and antiquities the . Journal of Contemporary

Criminal Justice, 24(3), 243-‐‑262.

Mackenzie, S. (2011). The market as criminal and criminals in the market: Reducing

opportunities for organised crime in the international antiquities market. In S.

Manacorda, & D. Chappell (Eds.), Crime in the art and antiquities world: Illegal

trafficking in cultural property (pp. 69-‐‑85). New York: Springer.

Manacorda, S., & Chappell, D. (2011). Introduction: From Cairo to Vienna and

beyond: Contemporary perspectives on the dialogue about protecting cultural

artefacts from plunder. In S. Manacorda, & D. Chappell (Eds.), Crime in the art

and antiquities world: Illegal trafficking in cultural property (pp. 1-‐‑15). New York:

Springer.

McLeave, H. (1981). Rogues in the gallery. Boston: David R. Godine, Publisher.

Naylor, R. T. (2008). The underworld of art. Crime, Law and Social Change, 50(4-‐‑5),

263–291.

Ou, A. (2011, June 25). The Chinese art of elegant bribery. Retrieved November 15,

2011, from h p://www.opendemocracy.net/openeconomy/antony-‐‑ou/chinese-‐‑

art-‐‑of-‐‑elegant-‐‑bribery

Passas, N., & Proulx, B. B. (2011). Overview of crimes and antiquities. In S.

Manacorda, & D. Chappell (Eds.), Crime in the art and antiquities world: Illegal

trafficking in cultural property (pp. 51-‐‑67). New York: Springer.

Pečar, J. (2002). Capacities and efficiency of prevention of crime -‐‑ some dilemmas.

Revija za kriminalistiko in kriminologijo, 54(4), 316-‐‑325.

Quarantelli, E. L., & Dynes, R. (1968). Looting in civil disorders: An index of social

change. American Behavioral Scientist, 11(4), 7-‐‑10.

Samardžić, R. (2010). Pogled na krađe umetničkih dela i antikviteta u Srbiji [A view

on stealing works of art in Serbia]. In B. Dobovšek (Ed.), Preiskovanje kriminalitete

404

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 404 9.1.2012 6:21:16

Bojan Dobovšek, Boštjan Slak

v zvezi z umetninami [Art Crime Investigation] (pp. 157-‐‑168). Ljubljana: Ministrstvo

za notranje zadeve, Policija.

Saunders, F. S. (1999). Who paid the piper?. London: Granta Books.

Tijhuis, A. (2009). Who is stealing all those paintings?. In N. Charney (Ed.), Art

crime: Exploring the dark side of the art world (pp. 41-‐‑51). Santa Barbara: Praeger/

ABC-‐‑CLIO.

Türkşen, U., Mısırlıoğlu, İ. U., & Yükseltürk, O. (2011). Anti-‐‑money laundering law

of Turkey and the EU: An example of convergence?. Journal of Money Laundering

Control, 14(3), 279-‐‑296.

Urice, S. K. (2010). Between rocks and hard places: Unprovenanced antiquities and

the National stolen property act. New Mexico Law Review, 40(winter), 123-‐‑161.

Wilford, H. (2008). The mighty wurlitzer: How the CIA played America. Cambridge:

Harvard University Press.

Abouth the Authors:

Bojan Dobovšek, PhD, Associate Professor and Vice-‐‑Dean of the Faculty of

Criminal Justice and Security, University of Maribor, Slovenia; Bojan.Dobovsek@

fvv.uni-‐‑mb.si

Boštjan Slak, postgraduate student at Faculty of Criminal Justice and Security,

University of Maribor, Slovenia; bostjan.slak@gmail.com

405

VS_Notranjost_2011_04.indd 405 9.1.2012 6:21:16

You might also like

- Value Investors Club - Treasure ASA (TRE ASA)Document9 pagesValue Investors Club - Treasure ASA (TRE ASA)Lukas Savickas100% (1)

- Art and CrimeDocument283 pagesArt and CrimeanaueneNo ratings yet

- Thomas Crow Unwritten Histories of Conceptual ArtDocument6 pagesThomas Crow Unwritten Histories of Conceptual Artarp_mNo ratings yet

- CBLM Bartending Ncii # 1 & 4aDocument265 pagesCBLM Bartending Ncii # 1 & 4aQueenly Mendoza Aguilar81% (21)

- Theorizing DocumentaryDocument18 pagesTheorizing DocumentaryIsabel Cadenas CañónNo ratings yet

- Comptia Linux Xk0 004 Exam Objectives (1 0)Document16 pagesComptia Linux Xk0 004 Exam Objectives (1 0)mueramon100% (1)

- SSC CHSL Study Schedule For Tier I - Crack The Exam in 3 Weeks!Document3 pagesSSC CHSL Study Schedule For Tier I - Crack The Exam in 3 Weeks!Tushita80% (15)

- Henk Borgdorff Dialogues Between Artistic Research and Science and Technology StudiesDocument225 pagesHenk Borgdorff Dialogues Between Artistic Research and Science and Technology StudiesMADSKILLS MOTASNo ratings yet

- ONCURATING Issue9Document94 pagesONCURATING Issue9William ChanNo ratings yet

- Gopnik: The Failure of Aesthetic ScienceDocument41 pagesGopnik: The Failure of Aesthetic ScienceBlake GopnikNo ratings yet

- The Artistic Turn: A ManifestoDocument190 pagesThe Artistic Turn: A ManifestoØliver Thurley100% (2)

- Mika Hannula - Juha Suoranta - Tere VadenDocument29 pagesMika Hannula - Juha Suoranta - Tere VadenAnonymous oqEdC54eDNo ratings yet

- The or Not Reflecting On Factish Field: Art and Anthropology Summer School, Kirsteen MacdonaldDocument31 pagesThe or Not Reflecting On Factish Field: Art and Anthropology Summer School, Kirsteen MacdonaldLUX67% (3)

- Object Studies in Art History: Research PerspectivesDocument12 pagesObject Studies in Art History: Research PerspectivesToshiro HitsugayaNo ratings yet

- Sorry, The Question Is Wrongly Put, Good Man (1978) - We ShouldDocument8 pagesSorry, The Question Is Wrongly Put, Good Man (1978) - We Shouldasujeha-8647No ratings yet

- 2010 Artistic Research JKleinDocument8 pages2010 Artistic Research JKleingonipelesNo ratings yet

- Smejkalova ArtasanargumentincourtDocument13 pagesSmejkalova ArtasanargumentincourtadvajayltiwariNo ratings yet

- Logos, Ethos, PathosDocument9 pagesLogos, Ethos, Pathosjean constantNo ratings yet

- Art and Speculative FuturesDocument9 pagesArt and Speculative FuturesKizu KataneNo ratings yet

- The Blindness of Justice - An Iconographic Dialogue Between Art and LawDocument39 pagesThe Blindness of Justice - An Iconographic Dialogue Between Art and LawDaniela DorfmanNo ratings yet

- 1887 - 3220730-Introduction BorgdorffDocument9 pages1887 - 3220730-Introduction BorgdorffCarlos Mario RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Art Criticism and The Objectivity or The Judgement of Taste PDFDocument39 pagesArt Criticism and The Objectivity or The Judgement of Taste PDFPro Deo Et EcclesiaNo ratings yet

- A Critique of Functionalist Definition of ArtDocument20 pagesA Critique of Functionalist Definition of Artomphalos15No ratings yet

- Nordbladh - Images As Messages of SocietiesDocument17 pagesNordbladh - Images As Messages of SocietiesAnastasia BurganovaNo ratings yet

- Art History and Multimedia: An Artefactual ApproachDocument8 pagesArt History and Multimedia: An Artefactual ApproachLily FakhreddineNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Artists and Colour MeaningDocument12 pagesContemporary Artists and Colour MeaningFriction MohammadNo ratings yet

- Elli Doulkaridou - Reframing Art History PDFDocument18 pagesElli Doulkaridou - Reframing Art History PDFWongaNo ratings yet

- EAEA11 PAPER T03 p451 KEPCZYNSKA WALCZAKDocument8 pagesEAEA11 PAPER T03 p451 KEPCZYNSKA WALCZAKtaqwa alhasaniNo ratings yet

- Visual Culture's HistoryDocument12 pagesVisual Culture's HistoryCarlos Felipe Suárez SánchezNo ratings yet

- Neer, ConnoisseurshipDocument26 pagesNeer, ConnoisseurshipjoacimsprungNo ratings yet

- Allen Anthropology 2008 PDFDocument94 pagesAllen Anthropology 2008 PDFjofrastjNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Art History and Sociology of ArtDocument5 pagesReflections On Art History and Sociology of ArtDoğan AkbulutNo ratings yet

- Wiley and The American Society For Aesthetics Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Journal of Aesthetics and Art CriticismDocument19 pagesWiley and The American Society For Aesthetics Are Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To The Journal of Aesthetics and Art CriticismvolodeaTis100% (1)

- Schubert - SwitchingWorlds - Englisch (Dragged) 3Document3 pagesSchubert - SwitchingWorlds - Englisch (Dragged) 3lolilolNo ratings yet

- 2 PDFDocument15 pages2 PDFHJNo ratings yet

- Processing HandbookDocument31 pagesProcessing HandbookIM_5727No ratings yet

- J Milo Taylor-YCT2008 Paper SubmissionDocument8 pagesJ Milo Taylor-YCT2008 Paper SubmissionRicardo AriasNo ratings yet

- Uncovering Creative Writing In: AnthropologyDocument1 pageUncovering Creative Writing In: AnthropologyJoean BetoNo ratings yet

- Creativity in The Visual Arts: October 2017Document31 pagesCreativity in The Visual Arts: October 2017Doru Constantin ColibaNo ratings yet

- Dessoir Art History and Systematics 1961Document8 pagesDessoir Art History and Systematics 1961Andrea PinottiNo ratings yet

- JW28Document7 pagesJW28Sarabjeet KaurNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On PaintingDocument8 pagesResearch Paper On Paintingijxnwybnd100% (1)

- A Philosophical Inquiry Into The Nature of Computer ArtDocument20 pagesA Philosophical Inquiry Into The Nature of Computer Artfreiheit137174No ratings yet

- MURPHY, Howard - The Antropology of ArtDocument22 pagesMURPHY, Howard - The Antropology of ArtjoseanapNo ratings yet

- Leuven University Press - The Artistic Turn A Manifesto - 2013-08-08Document3 pagesLeuven University Press - The Artistic Turn A Manifesto - 2013-08-08Lixo Electronico100% (1)

- Living Matter Materiality Maker and OrnaDocument21 pagesLiving Matter Materiality Maker and OrnamrrlrNo ratings yet

- What MattersDocument7 pagesWhat Matterspaulx93xNo ratings yet

- MullerDocument13 pagesMullerAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- ARt&Science Program The Hague - Studyguide2010-2011-ADocument44 pagesARt&Science Program The Hague - Studyguide2010-2011-AfedoerigoNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Aesthetics and Cognitive ScienceDocument15 pagesPhilosophical Aesthetics and Cognitive ScienceSamuel PimmontNo ratings yet

- Art History As Art CriticismDocument5 pagesArt History As Art CriticismOleksandraNo ratings yet

- 10821-Article Text-12435-1-10-20061123 PDFDocument4 pages10821-Article Text-12435-1-10-20061123 PDFdaniel martinNo ratings yet

- Conoisseurship EssayDocument12 pagesConoisseurship EssayEadaoin Mc DonaghNo ratings yet

- The H.W. Wilson Company/WilsonwebDocument5 pagesThe H.W. Wilson Company/WilsonwebDenisse Sánchez PintoraNo ratings yet

- Art, Meaning, and Perception: A Question of Methods For A Cognitive Neuroscience of ArtDocument18 pagesArt, Meaning, and Perception: A Question of Methods For A Cognitive Neuroscience of ArtLuciano LeonNo ratings yet

- Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical SciencesDocument11 pagesStudies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical SciencesErinnNo ratings yet

- The University of Chicago Press Bard Graduate CenterDocument18 pagesThe University of Chicago Press Bard Graduate CenterEdgaras GerasimovičiusNo ratings yet

- Generative Art With Processing and P5jsDocument37 pagesGenerative Art With Processing and P5jsgmconNo ratings yet

- Why Do Arts Based Research?Document15 pagesWhy Do Arts Based Research?Nicolás Lamas100% (1)

- Chaos/Appearance/Baroque: Contemporary Art. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007Document7 pagesChaos/Appearance/Baroque: Contemporary Art. Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007thot777No ratings yet

- TOK EssayDocument4 pagesTOK Essay7arthakendroNo ratings yet

- S. Fokt The Cultural Definition of Art 002Document27 pagesS. Fokt The Cultural Definition of Art 002Raffy Superales MarquezNo ratings yet

- Panofsky-Concept of KunstwollenDocument18 pagesPanofsky-Concept of KunstwollenderhegerNo ratings yet

- The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and SocietyDocument15 pagesThe Journal of Arts Management, Law, and SocietyanaueneNo ratings yet

- Sending Art Back by Toby Orford 2Document7 pagesSending Art Back by Toby Orford 2anaueneNo ratings yet

- Transnational Crimes Against Culture - Looting at Archaeological Sites and The ''Grey'' Market in Antiquities - Blythe A. BowmanDocument19 pagesTransnational Crimes Against Culture - Looting at Archaeological Sites and The ''Grey'' Market in Antiquities - Blythe A. BowmananaueneNo ratings yet

- Anna Louise Sussman - The New Collector's Guide To Understanding Art Pricing 2Document6 pagesAnna Louise Sussman - The New Collector's Guide To Understanding Art Pricing 2anaueneNo ratings yet

- Can White Men Sing The Blues - Joris Kila 2Document19 pagesCan White Men Sing The Blues - Joris Kila 2anaueneNo ratings yet

- AAMD - Art Museums by The Numbers 2016Document10 pagesAAMD - Art Museums by The Numbers 2016anaueneNo ratings yet

- Cuno James 2016 Responsibility To Protect TheDocument14 pagesCuno James 2016 Responsibility To Protect TheanaueneNo ratings yet

- Neoidealism in IRsDocument17 pagesNeoidealism in IRsanaueneNo ratings yet

- 2014 Art Market Intelligence 2Document6 pages2014 Art Market Intelligence 2anaueneNo ratings yet

- Non-Western International Relations Theorisation: Reflexive StocktakingDocument8 pagesNon-Western International Relations Theorisation: Reflexive StocktakinganaueneNo ratings yet

- Expert Meeting On The Responsibility To Protect' and The Protection of Cultural Heritage RecommendationsDocument2 pagesExpert Meeting On The Responsibility To Protect' and The Protection of Cultural Heritage RecommendationsanaueneNo ratings yet

- Long Quiz 1 Eim Tools, MaterialsDocument1 pageLong Quiz 1 Eim Tools, MaterialsLea Ann PalaciosNo ratings yet

- Normalization ExercisesDocument2 pagesNormalization ExercisesAnh DiệuNo ratings yet

- Vairamuthu Karuvachi Kaviyam PDFDocument1 pageVairamuthu Karuvachi Kaviyam PDFsabapathi13150% (2)

- Chem ReviseDocument206 pagesChem ReviseAmir ArifNo ratings yet

- CHN ReportingDocument24 pagesCHN ReportingMatth N. ErejerNo ratings yet

- Schema Theory Revisited Schema As SocialDocument37 pagesSchema Theory Revisited Schema As SocialpangphylisNo ratings yet

- Keeper of The Lost Cities - CGDocument4 pagesKeeper of The Lost Cities - CGat ur disposalNo ratings yet

- Jeselo O. Gorme, RN, MNDocument109 pagesJeselo O. Gorme, RN, MNcoosa liquorsNo ratings yet

- Attention and Effort. (1973)Document253 pagesAttention and Effort. (1973)Robert C. CasasNo ratings yet

- Star Wars FFG Homebrew - HOW TO USE SKILLS For Social SkillsDocument4 pagesStar Wars FFG Homebrew - HOW TO USE SKILLS For Social SkillsilkayNo ratings yet

- Performance APDocument29 pagesPerformance APMay Ann100% (1)

- Current Logk VkbaDocument8 pagesCurrent Logk Vkba21muhammad ilham thabariNo ratings yet

- Decanal Working Group On Indigenous Teaching and Learning ReportDocument73 pagesDecanal Working Group On Indigenous Teaching and Learning ReportIlya BanaresNo ratings yet

- English NotesDocument39 pagesEnglish NotesNorAini MohamadNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of DerivativesDocument12 pagesA Brief History of DerivativesPranab SahooNo ratings yet

- Rapes, Attacks, and Murders of Buddhists by MuslimsDocument11 pagesRapes, Attacks, and Murders of Buddhists by MuslimsPulp Ark100% (1)

- Marxist - Political Science IGNOUDocument15 pagesMarxist - Political Science IGNOUDesi Boy100% (2)

- NSFDCDocument10 pagesNSFDCAniket AhireNo ratings yet

- Workplace Health Promotion at Eska Rafinerska (Oil Refinery) 1. Organisations Involved 2. Description of The CaseDocument2 pagesWorkplace Health Promotion at Eska Rafinerska (Oil Refinery) 1. Organisations Involved 2. Description of The CaseDiana Vanessa GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Lecture-3: Market Equilibrium and Applications: Abdul Quadir XlriDocument37 pagesLecture-3: Market Equilibrium and Applications: Abdul Quadir Xlrianu balakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Surfactants and Emulsifying Agents: January 2009Document7 pagesSurfactants and Emulsifying Agents: January 2009Jocc Dee LightNo ratings yet

- Tan Shuy v. MaulawinDocument10 pagesTan Shuy v. MaulawinheyoooNo ratings yet

- APU CSLLT - 6 - Introduction To Assembly LanguageDocument23 pagesAPU CSLLT - 6 - Introduction To Assembly LanguageAli AtifNo ratings yet

- Gian Jyoti Institute of Management and Technology, Mohali Assignment No-1 Academic Session January-May 202Document4 pagesGian Jyoti Institute of Management and Technology, Mohali Assignment No-1 Academic Session January-May 202Isha aggarwalNo ratings yet

- DM Plan Manda Upazila Noagaon District - English Version-2014Document104 pagesDM Plan Manda Upazila Noagaon District - English Version-2014CDMP BangladeshNo ratings yet

- Identify The Industry - Case 5Document2 pagesIdentify The Industry - Case 5yuki_akitsu0% (1)