Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1博物馆背景

Uploaded by

波唐Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1博物馆背景

Uploaded by

波唐Copyright:

Available Formats

4 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT

The presence of computers and other technologies is increasingly evident in museums of

all kinds. Aside from changing visitor expectations of what might be encountered in a

leisurely afternoon museum trip, technology is having a profound impact on the ways in

which individuals interact in the museum environment, both with each other and with the

information museums contain. This is not to imply that artifact-based exhibits - historically

the basis of museums as storehouses for art, history, nature, and culture - are disappearing.

On the contrary, technology is being used to highlight the significance of the artifact by

providing contextual, historical, or theoretical information, thereby complementing and

strengthening the complete museum experience.

Underlying this move to provide broader learning experiences through multiple media,

is a recognition of the importance of interactivity in helping to gain new understanding. By

immersing the visitor in exhibit experiences and activities, giving them greater control and

more options for exploration, visitors discover that fun can also mean learning. Interac-

tivity, in all of its forms, is increasingly seen as the true key to enhancing learning for the

museum visitor.

The Educational Purposes of Museums

The museum environment has evolved over time to become a rich opportunity for mem-

bers of society to enjoy learning about history, art, science, technology, and nature. Interac-

tivity and technology-based exhibits are reflections of the changes toward public education

that have taken place in museums, and both are both are playing important roles in defining

future museums. The attention to public education that we see today, however, has not al-

ways been an important focus for museum professionals.

. .

The word "museum" is defined in the A m e r i c a n (2nd ed.) as "an in-

stitution for the acquisition, preservation, study and exhibition of works of artistic, histori-

cal, or scientific value." Originally from the Latin mouseion, which signified a temple

dedicated to the nine Muses who served as guiding spirits and sources of inspiration for

song, poetry, the arts, and sciences, the word museum has always connoted a place which of-

fers access to objects valued for their aesthetic or historic importance (Alexander, E., 1979,

p. 6). Although this common thread has persisted since the first museums, there have been

significant changes regarding the function of museums and methods of exhibition, mainly

since the turn of the century.

The first museums are frequently traced back to the Greek Temples which housed votive

offerings of statues, paintings, gold, silver, and bronze objects in order to attract religious

worshipers. But according to Schildt (1988, p. 85), the true beginning of museums as we

know them today, as places to admire art and other artifacts, occurred when King Attalus

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT 5

raided ancient Aegina and acquired a large number of statues that he greatly admired.

Having taken the statues from their natural setting he needed to create a substitute, and

that became the museum. Later, Romans began displaying paintings and sculptures in

forums and public gardens, or more commonly, in the homes of wealthy families

(Alexander, E., 1979). Churches and monasteries throughout western Europe upheld the

museum concept by collecting religious relics and icons. These collections grew significant-

ly after conquests and invasions, and for the most part remained the personal property of

society's aristocrats.

The primary function of museums in these early stages was to collect and study objects of

material, aesthetic or historic wealth (Zetterberg, 1968). This association of "collecting"

and "scholarly study" with the aristocrats led to the perception that art and scholarship were

for a closed circle, namely society's "upper crust." Collections were formed by individuals

who wished to show their masterpieces only to the connoisseurs and scholars whom they

considered to be their equals (Hudson, 1977). In the 16th century these great collections

brought prestige and power to their owners, who did not wish to share their treasures nor

their elite position with those outside their social class (Alexander, E., 1979) .

Access to these artistic and historical collections began to increase as monarchies were

overthrown, churches opened their monasteries to the masses, and as a greater number of

individuals claimed it as their right to see the collections (Hudson, 1975; Zetterberg, 1968).

The Imperial Gallery in Vienna as well as other museums around Europe started a trend of

requiring payment for the privilege to see the art work (Hudson, 1975), but it was not until

later in the seventeenth century that museums began to serve the public at large, starting

with university museums at Base1 in 1671, then at Oxford 12 years later (Alexander, E.,

1979, p. 8). Yet even as communities began to gain more widespread access, the attitudes

of the museum curators remained the same: visitors were seen as having been granted

entrance as a privilege, not as a right (Fisher, 1988, p.47; Hudson, 1977). Museums were

run by autocrats who did not consult with anyone about how to collect or organize their col-

lections for viewing - not the state which funded them, nor the public whom they supposed-

ly now served. The collection and exhibition process remained fairly personal and aimless

in terms of a public service plan.

Public demand and growing collections fueled the opening of more and more public

museums in the eighteenth century. The Vatican established several museums around

1750, and the British Parliament opened the British Museum in 1753 when it purchased Sir

Hans Sloane's natural science collection (Alexander, E., 1979). Another great European

museum opened in 1793 when France proclaimed its Palace of the Louvre as the Museum

of the Republic. Napoleon augmented the Louvre collections through his conquests and

confiscations until his fall from power. It was his obsession with the museum as an instru-

ment of national glory that aroused the desires of other European nations to devise similar

plans for their museums (Alexander, E., 1979). With the birth of the great European na-

tional museums came the desire to open these institutions to the entire population as well

as make efforts to attract visitors who could then admire the artifacts (Zetterberg, 1968). In

this patriotic function, museums became concerned with display techniques that would help

iopyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

6 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

the lay person appreciate museum collections; labels, docents, and guide-books became

standard informational tools (Zetterberg, 1968).

The development of museums in the United States was slower than in Europe but more

democratic. The first was the public Charleston Museum founded in 1773, in contrast to

the private beginnings of European museums. Other vanguard museums included the

Peale Museum in 1782, and the Salem Museum in 1799 (Hudson, 1977). In the mid-1800's

the Smithsonian Institution was formed with the goal of aiding in the "increase and diffusion

of knowledge" (Alexander, E., 1979, p. 11). Twenty-five years later came three of the

greatest American museums, the American Museum of Natural History and the

Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which

by theknd of the nineteenth century were being visited by large numbers of people ( ~ u d -

son, 1975).

The success of the Great Exhibition in London in 1851 and of the world fairs thereafter

are reported to have given museums the social importance and political power that they had

previously lacked (Alexander, E., 1979; Hudson, 1977). These great exhibitions brought to

light the necessity to display objects and information in a way that would attract

visitors"since they were commercial venturesUandspeak to the wide class of people that

came to them. The exhibitions also compelled governments to view information about the

sciences and arts as important for the entire community (Hudson, 1977), and sometimes the

buildings and collections were converted into museums after the expositions were over, e.g.,

The Exploratorium in San Francisco. By 1900, American museums were seen as places for

artistic enlightenment and education (Alexander, E., 1979).

For quite some time, however, museum education was based on a belief that people

could and should use their access to the artifacts that museums contain as a way to educate

themselves. Hudson (1975) referred to this as "open-education," where the only educational

responsibility of the museum was to provide the opportunity for learning to take place by

collecting and displaying the objects during scheduled hours (p. 61). The method of exhibi-

tion used by curators was to show as many objects and artifacts as possible (Finlay, 1977).

Adam (1939) called this approach "cafeteria" style display, where you serve yourself to the

information contained in the artifact (p.32). In the early 1900's this open-education attitude

was modified as more museum curators realized that they would need to provide an ele-

ment of entertainment and enjoyment for visitors if they were to draw the size audience

that would generate adequate funding for these growing publicly funded institutions

(Alexander, E., 1979). The goal of the curator became, in part, to increase public appeal of

the artifacts by making the past understandable in relation to the present (Booth, Krock-

over, & Woods, 1982, p. 10). After World War 11, more and more museums began to hire

professionally trained designers to help curators mount their exhibitions in the most aes-

thetic, appealing, and information-rich way, selectively displaying and calling attention to

their chief treasures (Finlay, 1977, p. 57; Maton-Howarth, 1990, p. 189; Miles, Alt, Gosling,

Lewis, & Tout, 1988). Today, most museums have specially trained exhibit designers whose

function is to attract, engage, and inform the visitor (Alexander, E., 1979; Miles, et al.,

1988).

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT 7

........................... .

:{;>!:>; . ; : : : : : : : $ ~ ~ ~ ~ m , . . f i : . : : : i : { : : ? : : ~ :

...:., .i::i:i:!:!:::::.i:.

:i.............................................................................................

:,;:.>:-:;:;::::: . : ........................

... ..........................

.':.:. . .:... :.:.::.:.:...:...:.:.:.: : .........>

. . . :.:.....:............

.......................

>i.i:<X::-.: :'!::;::;.-l:$:j":;.Ij : . ....................

::.::>;:;:;>:: : ... .

.........'.'.:.'-::::. .:.....................

..: :.:.:.-:-.:.::.:

..:.;................................................................

Recent research indicates that an increasing number of museum professionals are ac-

knowledging and capitalizing on the drawing power of having an element of entertainment

or fun in their exhibits (Boram, 1991; Cassedy, 1992; Vance & Schroeder, 1991; Interviews:

New England Technology Group, 1992). As examples, the Science Museum of Minnesota

describes their exhibits as having a "strong element of entertainment" (Dawson, 1992, p.

la); many of the interactive multimedia exhibits at the American Museum of Natural His-

tory employ learning games to maintain an element of fun (Wertheim, 1992); visitors to the

Boston Children's Museum can explore amusing topics, as in the "Bubbles" exhibit which

teaches visitors about the properties of bubble film (Feber, 1987). Although this perspec-

tive may be more evident in science and children's museums which typically employ the

most hands-on and playful exhibits, the personalities of educator and entertainer seem to

have merged in many museum environments (Alexander, E., 1979; Hudson, 1977; Miles et

al., 1988).

Combining learning and enjoyment helps define the museum as an alternative form of

public entertainment that competes with a trip to the movies or other weekend leisure ac-

tivities (Feber, 1987; Hooper-Greenhill, 1990). It is at least partially in response to this

competition that museums are incorporating interactive exhibits and activities that appeal

to a media saturated society (Feber, 1987; Ogintz, 1992b). This "infotainment" - informa-

tion combined with entertainment (also referred to as "edutainment", combined with educa-

tion) - approach to museum exhibit design has resulted in a number of attention getting

strategies. The use of hands-on exhibits, for example, has encouraged visitor participation

and enjoyment, and "blockbuster" exhibits such as The Treasures of Tutankhamen, represent

non-interactive examples of the edutainment strategy (Booth et al., 1982).

Desires to socialize and enrich ourselves intellectually have continued to shape today's

museum functions of collection, conservation, research, interpretation and exhibition

(Alexander, E., 1979; Weil, 1990). While each of these functions ultimately serves to pro-

vide information to the visitor, the heart of the museum as an educational asset is repre-

sented in meaningful exhibition which highlights the significance of the artifact to the

public. Museums are increasingly being recognized as offering a unique opportunity for

people of all ages and cultures to gain information that may not be as accessible to them

through traditional school channels and practices (Kelly, 1992), and most museums are in-

tent on heightening community awareness of this characteristic. In addition, the increasing

number of museums is allowing more opportunity for this learning to take place.

A study commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) estimated the

number of museums with operating budgets of at least $1,000 per month in 1974 to be 1,821

(NEA, 1974). This figure included art, history, science, and combination museums. The

study noted that there were more museums than the 1,821 that did not meet the inclusion

criteria, but not how many were omitted. In 1984, the AAM estimated there to be 5,000

museums (which included art and natural history museums, historical sites, science and

technology centers, arboretums, planetariums, children's museums, zoos, and botanical gar-

dens) in the US. By 1991, the AAM number rose to approximately 8,100, while the In-

stitute of Museum Services (IMS) estimated the number of museums to be 11,000.

Whatever the causes, the growth rates are impressive, even at the conservative estimate of

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

8 INTERACTIVE MULTIMEDIA IN AMERICAN MUSEUMS

9% per year (AAM, 1992). Concurrent with the growth in numbers of museums has been a

growth in the number of visitors. Museum visitation increased by 50 million between 1975

through 1979 (National Center for Educational Statistics, cited in Booth et al., 1982).

Booth et al. attribute these increases to greater public appeal of the exhibits being

mounted, increased leisure time, mobility and educational status of visitors, and expanded

media coverage of museum events (p. 5). Total annual attendance in all US museums was

estimated at approximately 515 million in 1986,540 million in 1987, and 565 million in 1988

(American Association of Museums, 1992).

As with any developed industry, an infrastructure has emerged as the museum field has

grown. In developing a nationwide accreditation program in the 1970's, the American As-

sociation of Museums (AAM) defined a museum as "an organized and permanent non-

profit institution, essentially educational or aesthetic in purpose, with professional staff,

which owns and utilizes tangible objects, cares for them and exhibits them to the public on

some regular schedule" (Alexander, E., 1979). The accreditation program was instituted to

provide museum professionals with consistent, clear guidelines by which they could judge

themselves and others, and to help donors evaluate contribution and grant requests.

Yet the guidelines are not as simple as they purport to be. For example, learning about

artifacts cannot take place without collection and study, but the efforts to conserve the ar-

tifacts are tested by the need to display them in a public setting, prone to dirt, moisture, and

light (Adam, 1939, p. 39; Hooper-Greenhill, 1988, p. 226). The conflicts between objectives

have created a dichotomy between museum functions, instead of, as Weil (1990) and Finlay

(1939) point out, a more beneficial fusion. According to Weil(1990) this is most evident in

the existence of separate education and exhibition departments within many art and history

museums (p.60). Hooper-Greenhill states the problem more generally: "the words educa-

tion, communication, and interpretation are a confused section of museum vocabula ry..."

(Greenhill, 1985, cited in Maton-Howarth, 1990, p. 191).

Historical differences in museum philosophies and content have lead to numerous

debates over what qualifies as a museum and what are the most important museum func-

tions (Miles et al., 1988). Some museums see collection or conservation as most important,

(Booth, Krockover, & Woods, 1982; Interviews: Behind the Scenes Publishing, 1992;

Museum Education Consortium, 1992). Similarly, there have been long-lasting debates

about what "educational purpose" means, as its definition has also varied among museums

(Adam, 1939; Miles et al., 1988). Some curators might consider an informational database

containing the contextual information on an exhibit as education, while others may consider

encouragement of academic research a sufficient educational goal. Maton-Howarth (1990)

believes that this lack of a clearly defined educational purpose continues to prevent the

educational wealth of museums from being fully realized (p. 186). She states that among

those museums which have adopted a clearly experiential or interactive approach to educa-

tional exhibits are many which have no clear educational policy at all.

These debates show some of the varied perspectives that have existed in the museum

community. While the issue of what qualifies as a museum seems to have faded somewhat,

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

I. THE MUSEUM CONTEXT 9

the importance of a museum's educational purpose has only grown (Booth et al. 1982;

Chapin & Klein, 1992; Rxcellence & Equity, 1992; Gable, 1992). The latest modification to

the AAM definition now describes museums as "institutions of public service and educa-

tion, a term that includes exploration, study, observation, critical thinking, contemplation

and dialogue" (Excellence & Eauiu, 1992, p. 6). This new definition clearly aims to

promote the informal educational role of museums by encouraging activities that induce in-

dividual responses to exhibits. More specifically, it focuses on non-traditional methods of

teaching, encouraging learning in an open, exploratory, user-paced environment. While the

official definition may merely represent another nobly worded goal not necessarily sup-

ported by actual museum activities, recent research and results from the interviews con-

ducted for this study reflect this new AAM definition.

The History of Interactive Multimedia in Museums

Among the many similarities across the categories of museums is the fact that all

museums present visitors with multimedia experiences (Alsford, & Granger, 1987; Bear-

man, 1993). Multimedia refers to any combination of two or more media used to present in-

formation, such as a slide show accompanied by narration or an artifact displayed near

descriptive signage. Museums are multimedia experiences since the visitor to any museum

is typically exposed to a number of media, such as paintings, historical artifacts, live animals,

or informational labels, each of which represents a different communicatisn medium.

Museums are also interactive in that a visitor need not experience the exhibits in a linear

manner - visitors can move at will from one exhibition room to the next, making use of

whatever available media (artifact, brochure, label, audio tape, guide, etc.) they choose to

help them explore the museum. In science and children's museums this notion of offering

interactive multimedia experiences has a slightly different meaning; visitors of these

museums are encouraged and expected to use their senses of sight, hearing, and touch to

physically interact with the exhibits. Interactive multimedia technologies are yet another

element of the multimedia experience that can be found in museums. These refer to the

computer-generation technologies that incorporate multiple media, such as text, sound,

video, or graphics, into an integrated computer system, which then serves as an exhibit that

can inform the visitor on a relevant museum topic using the most appropriate communica-

tions media. Throughout this report the phrase interactive multimedia will generally refer

to this more recent usage of the term multimedia as opposed to the non-technological

definitions.

The use of interactivity and technology in museums has been influenced by the differing

objectives and educational philosophies customary to different types of museums. Consider

each of the five museum categories examined in this study in turn: art; history; science and

technology; children's; and botanical gardens, arboretums, zoos, and aquariums.

Art museum contain collections of paintings, sculptures, pottery, and other noteworthy

artistic artifacts. The educational goal of these museums is typically to "train the taste and

aesthetic receptiveness of the visitor" (Zetterberg, 1968, p. 47). The interpretation of art,

Copyright Archives & Museum Informatics, 1993

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (842)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5806)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- National Geographic Almanac of World History, 2nd EditionDocument388 pagesNational Geographic Almanac of World History, 2nd EditionJared Zehm100% (2)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Lott, Eric. Love and TheftDocument342 pagesLott, Eric. Love and TheftgeorgelifeNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- African Histoty VDocument511 pagesAfrican Histoty VJohan Westerholm100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Typology and Universal William Croft PDFDocument27 pagesTypology and Universal William Croft PDFNia KariyaniNo ratings yet

- October 2017 CAIE P1 Mark Schemes 0837 English As A Second Language Cambridge Primary CheckpointDocument2 pagesOctober 2017 CAIE P1 Mark Schemes 0837 English As A Second Language Cambridge Primary CheckpointSsuzie Ana100% (1)

- Chapter 1.3 Activity 4Document2 pagesChapter 1.3 Activity 4Makiyo linNo ratings yet

- 5optimization of Microstructure and Properties of As-Cast Various Si Containing Cu-Cr-Zr Alloy by Experiments and First-Principles CalculationDocument10 pages5optimization of Microstructure and Properties of As-Cast Various Si Containing Cu-Cr-Zr Alloy by Experiments and First-Principles Calculation波唐No ratings yet

- Failure Pressure in Corroded Pipelines Based On Equivalent Solutions For Undamaged PipeDocument8 pagesFailure Pressure in Corroded Pipelines Based On Equivalent Solutions For Undamaged Pipe波唐No ratings yet

- JGR Solid Earth - 2013 - Qiu - in Situ Calibration of and Algorithm For Strain Monitoring Using Four Gauge BoreholeDocument10 pagesJGR Solid Earth - 2013 - Qiu - in Situ Calibration of and Algorithm For Strain Monitoring Using Four Gauge Borehole波唐No ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction Theory in Public Administration Education Revisiting Student Evaluation of Teaching PDFDocument8 pagesCustomer Satisfaction Theory in Public Administration Education Revisiting Student Evaluation of Teaching PDF波唐No ratings yet

- BR J Haematol - 2023 - Hokland - Thalassaemia A Global View PDFDocument16 pagesBR J Haematol - 2023 - Hokland - Thalassaemia A Global View PDF波唐No ratings yet

- Regression PDFDocument33 pagesRegression PDF波唐No ratings yet

- 5研究中的博物馆概况Document6 pages5研究中的博物馆概况波唐No ratings yet

- 4博物馆作为一种学习Document7 pages4博物馆作为一种学习波唐No ratings yet

- 3博物馆参观者Document3 pages3博物馆参观者波唐No ratings yet

- 2博物馆互动多媒体的历史Document7 pages2博物馆互动多媒体的历史波唐No ratings yet

- Bri Ame Identity and Lifestyle 6.2021 CTC+CLC UpdatedDocument5 pagesBri Ame Identity and Lifestyle 6.2021 CTC+CLC UpdatedThien Van Phan PhucNo ratings yet

- 1 SMDocument15 pages1 SMkeiarakyutaroNo ratings yet

- Purposive CommunicationDocument2 pagesPurposive CommunicationRodemae OrtizNo ratings yet

- l2 U1 WordlistDocument2 pagesl2 U1 Wordlistbube isijanovskaNo ratings yet

- Indian EnglishDocument3 pagesIndian EnglishZamfir AlinaNo ratings yet

- ELIA 112 Final Speaking Exam Rating Scale 2022.23Document1 pageELIA 112 Final Speaking Exam Rating Scale 2022.23Happiness BankNo ratings yet

- Theories of Translation and Interpreting Mid Term Test - Muhamad Dzaky Robith - 0920013771Document2 pagesTheories of Translation and Interpreting Mid Term Test - Muhamad Dzaky Robith - 0920013771dzakyrobithNo ratings yet

- Morphemic AnalysisDocument7 pagesMorphemic Analysisapi-309214138100% (3)

- England TodayDocument11 pagesEngland TodayCorina FlorentinaNo ratings yet

- 1 English Camp DetailsDocument3 pages1 English Camp DetailsFirdaus HoNo ratings yet

- Language Learning at An Early AgeDocument51 pagesLanguage Learning at An Early AgeHanah MocoyNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 8 Q1 W1 Determine The Meaning of Words and Expressions That Reflect The Local Culture by Noting Context CluesDocument7 pagesENGLISH 8 Q1 W1 Determine The Meaning of Words and Expressions That Reflect The Local Culture by Noting Context CluesMA. VICTORIA EBUÑANo ratings yet

- Right-Side Elevation Plan Front Elevation Plan: 1 2 3 4 6 5 4 A B C D EDocument1 pageRight-Side Elevation Plan Front Elevation Plan: 1 2 3 4 6 5 4 A B C D EVerna Balang MartinezNo ratings yet

- Teacher's Guide For Grade 5Document55 pagesTeacher's Guide For Grade 5hawa ahmedNo ratings yet

- КТП 7 кл 2022-2023 1 полугDocument7 pagesКТП 7 кл 2022-2023 1 полугкатяNo ratings yet

- School Form 1 (SF 1) School RegisterDocument6 pagesSchool Form 1 (SF 1) School RegisterTek CasoneteNo ratings yet

- Colladod2119721197 8Document85 pagesColladod2119721197 8whysignupagainNo ratings yet

- Antonius H Cillessen - David Schwartz - Lara Mayeux - Popularity in The Peer System-Guilford Press (2011)Document320 pagesAntonius H Cillessen - David Schwartz - Lara Mayeux - Popularity in The Peer System-Guilford Press (2011)Marie-Amour KASSANo ratings yet

- Bai Tap Tieng Anh 9 Bai 9Document16 pagesBai Tap Tieng Anh 9 Bai 9nguyenhaphong04052002No ratings yet

- 8A (2nd) Looking After YourselfDocument27 pages8A (2nd) Looking After YourselfHuy Nguyễn Phan TrườngNo ratings yet

- English-Tests - Aprobados Por La Embajada Britanica para VisaDocument20 pagesEnglish-Tests - Aprobados Por La Embajada Britanica para VisaAndres SarmientoNo ratings yet

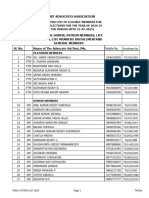

- Final Voter List Thcaa 2024-25Document155 pagesFinal Voter List Thcaa 2024-25Vinod KumarNo ratings yet

- Unit V Grammar V - ExplanationDocument2 pagesUnit V Grammar V - ExplanationNarotama Hayu BasundaraNo ratings yet

- CASE METHOD Psycholinguistic Sindhyka BanureaDocument4 pagesCASE METHOD Psycholinguistic Sindhyka Banureasindhyka banureaNo ratings yet