Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Progress in Human Geography: From Resilience To Resourcefulness: A Critique of Resilience Policy and Activism

Uploaded by

Alberto A PerezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Progress in Human Geography: From Resilience To Resourcefulness: A Critique of Resilience Policy and Activism

Uploaded by

Alberto A PerezCopyright:

Available Formats

Progress in Human Geography

http://phg.sagepub.com/

From resilience to resourcefulness: A critique of resilience policy and activism

Danny MacKinnon and Kate Driscoll Derickson

Prog Hum Geogr 2013 37: 253 originally published online 8 August 2012

DOI: 10.1177/0309132512454775

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://phg.sagepub.com/content/37/2/253

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Progress in Human Geography can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://phg.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://phg.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - Mar 11, 2013

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Aug 8, 2012

What is This?

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

Article

Progress in Human Geography

37(2) 253–270

From resilience to ª The Author(s) 2012

Reprints and permission:

resourcefulness: A critique of sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0309132512454775

phg.sagepub.com

resilience policy and activism

Danny MacKinnon

University of Glasgow, UK

Kate Driscoll Derickson

Georgia State University, USA

Abstract

This paper provides a theoretical and political critique of how the concept of resilience has been applied to

places. It is based upon three main points. First, the ecological concept of resilience is conservative when

applied to social relations. Second, resilience is externally defined by state agencies and expert knowledge.

Third, a concern with the resilience of places is misplaced in terms of spatial scale, since the processes which

shape resilience operate primary at the scale of capitalist social relations. In place of resilience, we offer the

concept of resourcefulness as an alternative approach for community groups to foster.

Keywords

communities, ecology, resilience, resourcefulness, social relations

Concepts of resilience are used to describe I Introduction

the relationship between the system under

observation and externally induced disruption, The concept of ‘resilience’ has migrated from

stress, disturbance or crisis. In a more general the natural and physical sciences into the social

sense, resilience is about the stability of a sys- sciences and public policy as the identification

tem against interference. It is, however, more of global threats such as economic crisis, cli-

than a response to or coping with particular mate change and international terrorism has

challenges. Resilience can be seen as a kind focused attention on the responsive capacities

of systemic property. (Lang, 2010: 16) of places and social systems (Hill et al., 2008;

Swanstrom et al., 2009). The question of how

In its tendency to metabolize all countervailing to build up the resilience of places and organiza-

forces and insulate itself against critique, ‘resi-

tions is attracting great interest, especially in the

lience thinking’ cannot be challenged from

within the terms of complex systems theory

but must be contested, if at all, on completely Corresponding author:

different terms, by a movement of thought that Danny MacKinnon, School of Geographical and Earth

is truly counter-systemic. (Walker and Cooper, Sciences, University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK.

2011: 157) Email: Daniel.MacKinnon@glasgow.ac.uk

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

254 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

‘grey literature’ produced by government agen- that resilient spaces are precisely what capital-

cies, think tanks, consultancies and environ- ism needs – spaces that are periodically rein-

mental interest groups. As Walker and Cooper vented to meet the changing demands of

(2011: 144) observe, the concept of resilience capital accumulation in an increasingly globa-

has become ‘a pervasive idiom of global gov- lized economy. From this perspective, both the

ernance’, being ‘abstract and malleable enough sources of resilience and the forces generating

to encompass the worlds of high finance, disruption and crisis are internal to the capitalist

defence and urban infrastructure’. In particular, ‘system’. Crucially, the resilience of capitalism

the frequency by which resilience is invoked by is achieved at the expense of certain social

progressive activists and movements underlines groups and regions that bear the costs of peri-

the need for critical appraisal of both the term odic waves of adaptation and restructuring.

itself and the politics it animates. Through our Our critique of resilience is based upon three

own ongoing engagement with a grassroots points. First, we argue that the concept of resili-

project in Govan, a post-industrial neighbour- ence, derived from ecology and systems theory,

hood in Glasgow, as well as through attending is conservative when applied to the social

a variety of events in Britain over the past year sphere, referring to the stability of a system

that have attracted representatives of environ- against interference as emphasized in the first

mental groups and campaigns such as Transi- of our opening quotations (Lang, 2010). This

tion Towns, Grow Heathrow, and Coexist,1 it apolitical ecology not only privileges estab-

is clear that ‘resilience’ is helping to frame par- lished social structures, which are often shaped

ticular forms of activism, some of which are by unequal power relations and injustice

anti-capitalist in nature. (Harvey, 1996; Swyngedouw and Heynen,

This paper aims to provide a theoretical and 2003), but also closes off wider questions of

political critique of how the concept of resili- progressive social change which require inter-

ence has been applied to places. In particular, ference with, and transformation of, established

we are concerned with the spatial politics and ‘systems’. Thus, while Larner and Moreton

associated implications of resilience discourse, (2012) suggest that resilience can generate a

something which we consider to have been politics that prefigures alternative social

neglected in the burgeoning social science liter- relations, we do not regard it as the best way

ature (Agder, 2000; Norris et al., 2008; to animate such a politics. Second, resilience

O’Malley, 2010; Simmie and Martin, 2010).2 is externally defined by state agencies and

A key issue here concerns the importation of expert knowledge in spheres such as security,

naturalistic concepts and metaphors to the social emergency planning, economic development

sciences and the need to problematize social and urban design (Coaffee and Rogers, 2008;

relations and structures, rather than taking them Walker and Cooper, 2011). Such ‘top-down’

for granted (Barnes, 1997). This requires recog- strategies invariably place the onus on individu-

nition of the ecological dominance of capitalism als, communities and places to become more

in terms of its capacity to imprint its develop- resilient and adaptable to a range of external

mental logic on associated social relations, threats (O’Malley, 2010), serving to reproduce

institutions and spaces (Jessop, 2000).3 From a the wider social and spatial relations that gener-

geographical perspective, urban and regional ate turbulence and inequality. Third, we contend

‘resilience’ as an objective must be understood that the concern with the resilience of places is

in relation to the uneven spatial development misconceived in terms of spatial scale. Here,

of capitalism across a range of spatial sites and resilience policy seems to rely on an underlying

scales (Smith, 1990). In this context, we suggest local-global divide whereby different scales

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 255

such as the national, regional, urban and local conditions in which communities can develop

are defined as arenas for ensuring adaptability alternative visions of social relations. It is

in the face of immutable global threats.4 This intended to foster a ‘counter-systemic’ mode

fosters an internalist conception which locates of thought (and practice) that transcends sys-

the sources of resilience as lying within the par- tems theory and resilience thinking in the spirit

ticular scale in question. As a result, resilience of our second opening quotation (Walker and

policy is devolving what Peck and Tickell Cooper, 2011: 157).

(2002: 386) call ‘responsibility without power’ The remainder of the paper is divided into six

by effectively setting up communities and sections. The next section discusses the concept

places to take what our collaborator Gehan and discourse of resilience, tracing its migration

MacLeod has called ‘knock after knock’ and from the natural sciences to the realm of urban

keep getting up again. By contrast, we contend and regional policy and activism. We then

that the processes which shape resilience address the three points of our critique in turn.

operate primarily at the scale of capitalist social This is followed by a consideration of the possi-

relations (Hudson, 2010). bilities of resourcefulness as an alternative

Beyond this critique, our approach is atten- approach for communities and oppositional

tive to what we understand to be the normative groups. Finally, we summarize our arguments

political yearnings that underpin resilience talk and consider their implications.

among oppositional groups and campaigns. In

these contexts, we recognize that resilience is

meant to prefigure alternative social relations II Resilience and its uses

in which social and environmental well-being The concept of resilience has roots in both phy-

is the system which is to be privileged (i.e. the sics and mathematics, where it refers to the

resilient system), with capitalism seen as one capacity of a system or material to recover its

of a number of disruptive and destructive forces. shape following a displacement or disturbance

Without intending to belittle such activism, we (Norris et al., 2008), and ecology where it

view the cultivation of what Spivak (2012) has emphasizes the capacity of an ecosystem to

termed a will to social justice as a first step absorb shocks and maintain functioning (Folke,

towards realizing the vision that we understand 2006; Holling, 1973). Subsequent applications

resilience activism as attempting to ‘prefigure’. to a number of objects from the built environ-

Put another way, if alternative social relations ment to individuals, social systems and commu-

are to be realized democratically and sustain- nities have spawned a range of definitions

ably, and in ways that are wide-reaching and (Table 1). The work of the American ecologist

inclusive (as opposed to uneven or vanguard- C.S. Holling (1973, 2001) has proved particu-

driven), then uneven access to material larly influential, not least through his role in

resources and the levers of social change must groups such as the Resilience Alliance of scien-

be redressed. To that end, we offer resourceful- tists and the Stockholm Resilience Centre, a

ness as an alternative concept to animate poli- high-profile think-tank (Walker and Cooper,

tics and activism that seek to transform social 2011). Researchers often distinguish between

relations in more progressive, anti-capitalist and resistance and ‘bounce back’, where the former

socially just ways. In contrast to resilience, refers to the ability of a system to block disrup-

resourcefulness as an animating concept specifi- tive changes and remain relatively undisturbed,

cally seeks to both problematize and redress while the latter is defined in terms of the capac-

issues of recognition and redistribution (Fraser, ity to recover from shock and return to normal

1996; Young, 1990) and work toward cultivating functioning.

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

256 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

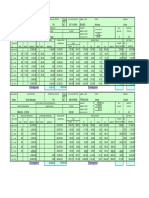

Table 1. Selected definitions of resilience.

Author, date Discipline Level of analysis Definition

Gordon, 1978 Physics Physical system The ability to store energy and deflect

elasticity under a load without breaking

or being deformed

Holling, 1973 Ecology Ecological system The persistence of relationships within a

system; the ability of systems to absorb

change and still persist

Resilience Alliance, Ecology Ecological system The capacity to tolerate disturbance

undated without collapsing into a qualitatively

different state (http://

www.resalliance.org/index.php/

resilience)

Egeland et al., 1993 Psychology Individual The capacity for successful adaptation and

functioning despite high risk, stress or

trauma

Agder, 2000 Geography Community The ability of communities to withstand

external shocks to their social

infrastructure

Katz, 2004 Geography Community Ways in which people adapt to changing

circumstances to get by and ‘make do’

through the exercising of autonomous

initiative

Hill et al., 2008 Urban and regional Region The ability of a region to recover

development successfully from shocks to its economy

Source: Adapted and extended from Norris et al. (2008: 129).

In the ecological literature, two types of resi- with caution as it relies on a conception of exter-

lience are commonly identified (Folke, 2006; nal shocks triggering a shift from one relatively

Holling, 1973). The first is ‘engineering resili- stable regime to another, simply recognizing

ence’, which is concerned with the stability of that equilibria are multiple rather than single.

a system near to an equilibrium or steady state, In recent years, the ecologically rooted con-

where resilience is defined in terms of elasticity cept of resilience has rapidly infiltrated public

which emphasizes resistance to disruption and policy fields such as national security, financial

speed of return to the pre-existing equilibrium. management, public health, economic develop-

Second, ‘ecological resilience’ refers to exter- ment and urban planning as policy-makers and

nal disturbances and shocks that result in a expert advisors have adopted the concept

system becoming transformed through the (Walker and Cooper, 2011). For instance,

emergence of new structures and behaviours. increased concerns about terrorism in the wake

This understanding of resilience appears to be of the 11 September 2001 attacks have led to

complex and open-ended, making it more suit- widespread securitization though increased

able for the study of social phenomena charac- electronic surveillance, the establishment of

terized by ongoing adaptation and learning bounded and secure zones in cities and key

(Pickett et al., 2004; Pike et al., 2010). Yet transport hubs, and the adoption of increasingly

Simmie and Martin (2010) suggest that even the complex forms of contingency and scenario

ecological model of resilience should be treated planning (Coaffee and Murakami Wood,

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 257

2006). Lentzos and Rose (2009) distinguish Policy-makers in the UK have also placed an

between three national models of biosecurity: increasing emphasis on the social and commu-

a contingency planning approach in France; an nity aspects of resilience in recent years, seek-

emphasis on protection in Germany; and the ing to raise public awareness of potential

UK strategy of resilience. UK resilience threats and to encourage increased ‘responsibili-

amounts to more than simply preparedness, zation’ by involving citizens and communities in

implying a systematic programme of measures their own risk management (O’Malley, 2010).

and structures to enable organizations and This resulted in the publication of a Strategic

communities to better anticipate and tolerate National Framework on Community Resilience

disruption and turbulence (Anderson, 2010). (Cabinet Office, 2011), defined in terms of ‘com-

This requires what has been termed a ‘multi- munities and individuals harnessing local

scale governance fix’ (Coaffee and Murakami resources and expertise to help themselves in

Wood, 2006: 509), involving the establishment an emergency’ (p. 4). Here, community resili-

of Local Resilience Forums and Regional Resi- ence is viewed in terms of the Conservative-

lience Teams within each of the Government Liberal Democrat Coalition Government’s ‘Big

Offices for the Regions in England, overseen Society’ agenda, which is intended to promote

by the Civil Contingencies Secretariat in the greater community self-reliance and empower-

Cabinet Office (Cabinet Office, 2010).5 ment by reducing the powers of the state and

Walker and Cooper (2011: 144) argue that encouraging volunteering and community activ-

the success of resilience in ‘colonizing multiple ity (HM Government, 2010).

arenas of governance’ reflects its ideological fit The recent upsurge of interest in community

with neoliberalism. Contemporary forms of resilience is not only a product of the ‘top-

securitization overlap substantially with neolib- down’ strategies of government, but also of the

eral discourses of competitiveness, which ‘bottom-up’ activities of a wide variety of com-

emphasize the need to promote economic munity groups and environmental campaigns.

growth (Bristow, 2010). Such discourses sup- In the context of the rapidly growing Transition

port a framework of interregional competition Towns movement (Bailey et al., 2010; Mason

in which cities and regions have effectively and Whitehead, 2012), for instance, resilience

become ‘hostile brothers’ which compete for seems to be supplanting ‘sustainability’, provid-

investment, markets and resources (Peck and ing a renewed focus for initiatives seeking to

Tickell, 1994). Enhanced regional competi- localize the supply of food and energy in partic-

tiveness is seen as the key to success in glo- ular (Mason and Whitehead, 2012). In the case

bal markets by policy-makers and business of Govan Together, a project with which we

leaders, based upon the harnessing of local have worked closely over the past year as colla-

resources and assets through initiatives which borators and researchers, the language of resili-

seek to upgrade workforce skills, stimulate ence was meant to promote thinking about

the formation of new firms, and foster inno- nature and society in a systemic way, influenced

vation and learning (Bristow, 2010; MacKin- in large part by the intellectual framework of

non et al., 2002). Increasingly, resilience and ‘human ecology’. Informed by such initiatives,

security strategies have been linked to com- the Carnegie UK Trust (2011) has produced a

petition for footloose global capital with handbook on community resilience which

urban marketing strategies, for instance, emphasizes the need for people to come

stressing the ‘safety’ and ‘security’ of cities together to ‘future-proof their communities on

as places to conduct business (Coaffee and the basis of agreed values’ (p. 4). The second

Murakami Wood, 2006). part of the handbook outlines a ‘compass’ of

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

258 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

community resilience based upon: healthy, in relation to the technical mastery of cities.

engaged people; an inclusive and creative (Gandy, 2002: 8)

culture that generates a positive and welcoming

sense of place; a localized economy that oper- In the context of scientific efforts to create more

ates within ecological limits; and the fostering resilient urban infrastructures, Evans (2011:

of supportive intercommunity links. Research- 224) suggests that ecologists may come to play

ers have noted, however, that this burgeoning an analogous role in the shaping of 21st-century

sphere of action tends to operate through a kind cities to that of the sanitarians in the 19th cen-

of inclusive localism that is largely apolitical tury. Informed by the work of ecological author-

and pragmatic in character (Mason and White- ities such as Holling, Arthur Tansley and the

head, 2012; Trapese Collective, 2008). Resilience Alliance on ecosystems as complex

adaptive systems, this new urban ecology con-

ceives of the city as a social-ecological system,

III Resilience and the privileging of in which biophysical and social factors are

existing social relations linked by multiple feedback loops and exhibit

Resilience can be seen as the latest in a long line the common properties of resilience and com-

of naturalistic metaphors to be applied to cities plexity (Evans, 2011; Folke, 2006). The effect

and regions (Barnes, 1997; Evans, 2011; Gandy, is to naturalize cities and regions as self-

2002). Organic conceptions of cities as systems contained systems by divorcing them ‘from

displaying natural traits such as growth, compe- wider determinants of urban form’ such as flows

tition and self-organization have proven partic- of capital and modes of state regulation (Gandy,

ularly influential, informing the urban ecologies 2002: 8). The abstract language of systems the-

of Patrick Geddes, Ebenezer Howard and the ory and complexity science offers a mode of

Chicago School (Evans, 2011). The notion of intellectual colonization which serves to objec-

the ‘sanitary’ or ‘bacteriological’ city took tify and depoliticize the spheres of urban and

shape from the mid- to late 19th century, based regional governance, normalizing the emphasis

upon the application of the nascent sciences of on adaptation to prevailing environmental and

epidemiology and microbiology, alongside the economic conditions and foreclosing wider

emerging professions of planning and civil sociopolitical questions of power and represen-

engineering (Gandy, 2002; Pincetl, 2010). The tation (Evans, 2011).

use of natural metaphors had implications for The implication of the extension of ecologi-

the governance and management of cities, as cal thinking to the social sphere is that human

Gandy (2002) observes: society should mimic the decentralized and resi-

lient processes of nature (Swanstrom, 2008: 15).

In the twentieth century, a range of technologi- Resilience is fundamentally about how best to

cal advances facilitated a new mediation maintain the functioning of an existing system

between organic metaphors and the production in the face of externally derived disturbance.

of urban space. In 1965, for example, the engi-

Both the ontological nature of ‘the system’ and

neer Abel Wolman outlined ‘the complete

its normative desirability escape critical scru-

metabolism of the modern city’ as the culmina-

tion of advances in the technical organization tiny. As a result, the existence of social divisions

of urban space. Yet these metabolic metaphors and inequalities tends to be glossed over when

treat the city as a discrete physical entity. The resilience thinking is extended to society

‘body of the city’ is considered in isolation (p. 15). Ecological models of resilience are fun-

from wider determinants of urban form, and damentally anti-political, viewing adaptation to

the social production of space is downplayed change in terms of decentralized actors, systems

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 259

and relationships and failing to accommodate individuals, they often have the effect of sup-

the critical role of the state and politics (Evans, pressing social difference (according to class,

2011; Swanstrom, 2008). Deference to ‘the gender, race, etc.) and masking inequality and

emergent order of nature’ (Swanstrom, 2008: hierarchy (DeFilippis et al., 2006; Joseph,

16) is implicitly extended to society as existing 2002; Young, 1990). As such, the bracketing

social networks and institutions are taken for of resilience with community works to reinforce

granted as ‘natural’ and harmonious. This the underlying imperative of resilience-building

reflects the origins of resilience thinking in the through the abstract identification of its

writings of Holling and others as a critique of sociospatial object (the community in question),

the methods of scientific resource management fostering a sense of common purpose and unity.

employed by state agencies in the 1960s and The effect is to further naturalize not only

1970s (Ostrom, 2005), fostering a suspicion of resilience itself as a common project, but also

central authority that has affinities with the the social and political relations which are to

work of Hayek (Walker and Cooper, 2011).6 be mobilized in the pursuit of this project.

In response, Swanstrom (2008: 16) argues that

the neglect of the role of the state and politics

and the privileging of harmonious social net-

IV Resilience as an externally

works renders the ecological model of resilience defined imperative

‘profoundly conservative’ when it is exported The second point of our critique is concerned

into a social context. This conservatism is rein- with the external definition of resilience by state

forced by the normative aspect of resilience agencies and expert analysts across a range of

(O’Malley, 2010), which is assumed to be policy spheres (Coaffee and Rogers, 2008;

always a positive quality, imbued with notions Walker and Cooper, 2011). In this context, the

of individual self-reliance and triumph over ‘pseudo-scientific discourse’ of resilience pre-

adversity. sents something of a paradox of change: empha-

Both government agencies and local environ- sizing the prevalence of turbulence and crisis,

mental groups emphasize the need for commu- yet accepting them passively and placing the

nities to become more resilient and self-reliant onus on communities to get on with the business

(Cabinet Office, 2011; Carnegie UK Trust, of adapting (Evans, 2011: 234). The effect is to

2011). In common with transition thinking, this naturalize crisis, resonating with neoliberal dis-

agenda favours community self-organization in courses which stress the inevitability of globali-

terms of the agency of local people to make their zation (Held and McGrew, 2002). In the sphere

communities more resilient, while overlooking of security, for instance, the identification of

the affinities with neoliberal thinking. Yet, as ‘new’ global risks, coupled with political lead-

a number of critical scholars have argued, the ers’ claims of ‘unique’ and ‘classified’ knowl-

nebulous but tremendously evocative concept edge of potential threats, justified ‘the

of community is commonly deployed to bestow implementation of a raft of resilience policies

particular initiatives with unequivocally posi- without critical civic consultation’ following

tive connotations as being undertaken in the the events of 11 September 2001 (Coaffee and

common interest of a social collectivity (DeFi- Rogers, 2008: 115). In the context of urban and

lippis et al., 2006; Joseph, 2002). Rather than regional development, resilience has become

referring to a pre-existing collective interest, the latest policy imperative by which cities and

invocations of community attempt to construct regions are entreated to mobilize their endogen-

and mobilize such a collectivity. By generating ous assets and resources to compete in global

a discourse of equivalence between groups and markets (Wolfe, 2010).

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

260 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

The emerging literature on regional resili- ‘creative cities’ craze of the mid-2000s (Florida,

ence policy emphasizes that resilience should 2002; Peck, 2010). Like the creative cities

be seen as a dynamic process such that particu- script, resilience is a mobilizing discourse, con-

lar shocks or crises must be situated in the fronting organizations, individuals and commu-

context of longer run processes of change such nities with the imperative of ongoing adaptation

as deindustrialization (Dawley et al., 2010). The to the challenges of an increasingly turbulent

role of regional institutions is to foster the adap- environment. Beyond the recurring appeal to

tive capacity to enable the renewal and ‘branch- innovation and strategic leadership, resilience

ing out’ of economic activity from existing can be seen as a more socially inclusive narra-

assets, echoing the processes that seem to have tive, requiring all sections of the community,

underpinned the development of successful and not just policy-makers serving the needs

regions such as Cambridge (Dawley et al., of privileged ‘creatives’, to foster permanent

2010; Simmie and Martin, 2010). A key theme adaptability in the face of external threats

concerns the importance of civic capacity and (O’Malley, 2010). In the context of national

strategic leadership in framing and responding security, this calls for a ‘culture of resilience’

to particular crises and challenges. According which integrates ‘emergency preparedness into

to Wolfe (2010: 145), ‘Successful regions must the infrastructures of everyday life and the

be able to engage in strategic planning exercises psychology of citizens’ (Walker and Cooper,

that identify and cultivate their assets, undertake 2011: 159).

collaborative processes to plan and implement Research on urban resilience tends to opera-

change and encourage a regional mindset that tionalize the term ‘resilience’ as it pertains to

fosters growth’. A key task is the undertaking the ability of cities to either continue to replicate

of detailed foresight and horizon-scanning work their day-to-day functions in the face of major

to identify and assess emergent market trends shocks such as a terrorist attack or an extreme

and technologies. Such anticipatory exercises weather event, or to adapt to longer-term disrup-

reflect how resilience thinking is associated tive forces such as climate change (Otto-

with the adoption of a range of non-predictive and Zimmerman, 2011). While it is common for

futurological methods of risk analysis and man- work in this vein to describe cities as ‘complex’

agement such as scenario planning (Anderson, or ‘dynamic’ systems, in this work the term

2010; Lentzos and Rose, 2009; Walker and ‘system’ appears to refer merely to the everyday

Cooper, 2011). functioning of cities, rather than some fully con-

As indicated above, resilience is serving to ceptualized and empirically validated abstract

reinforce and extend existing trends in urban model. Typically, ‘urban resilience’ mobilizes

regional development policy towards increased a coupled human and natural systems frame-

responsiveness to market conditions, strategic work for conceptualizing urban systems.

management and the harnessing of endogenous Whereas Pickett et al. (2004) describe ‘resili-

regional assets. In this sense, resilience policy ence’ as a metaphor for integrating analyses of

fits closely with pre-established discourses of urban design, ecology and social science, a

spatial competition and urban entrepreneurial- more recent articulation of a framework for

ism (Bristow, 2010; Peck, 2010). Its proximity urban resilience research identifies ‘metabolic

to the prior understandings and outlooks of flows’, ‘governance networks’, ‘social

urban and regional policy-makers helps to dynamics’ and the ‘built environment’ as the

account for the widespread adoption of resili- key features of the urban ‘system’ (CSIRO,

ence in economic development circles, provid- 2007). The Long Term Ecological Research

ing a somewhat more muted successor to the programme in the United States (USA)

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 261

incorporates sites in Baltimore and Phoenix arenas for fostering local adaptation in the face

where scientists have been undertaking adaptive of global threats. Yet the question of whether

experiments in urban governance, defining the the spatial unit in question can be usefully or

city as a social-ecological system. As Evans accurately understood as a self-organizing

(2011) argues, the ‘scientific assumptions of entity modelled after ecosystems remains unad-

resilience ecology run the risk of political dressed. Informed by the extensive literature on

foreclosure because they frame the governance scale (Brenner, 2004; MacKinnon, 2011), we

choices that are available, often in feedback argue that viewing cities and regions as self-

mechanisms that are seemingly neutral’ (p. 232). organizing units is fundamentally misplaced,

Some scientists associated with the Resili- serving to divorce them from wider processes

ence Alliance have emphasized the need to of capital accumulation and state regulation.

insert politics into research on resilience, partic- Discussions of resilience in the social

ularly in terms of how governance can enhance sciences have tended to move from responses

the capacity to manage resilience (Folke, 2006; to natural disasters to consider the effects of

Lebel et al., 2006). Accordingly, Lebel et al. economic shocks without recognizing the spe-

(2006) identify three key dimensions of this cific properties and characteristics of capitalism

capacity: public participation and deliberation; as the ecologically dominant system (Jessop,

polycentric and multi-layered institutions; and 2000). The result has been to take capitalism for

accountable and just institutions. While this rep- granted as an immutable external force akin to

resents a welcome advance in many respects, the forces of nature, while focusing attention

the proffered solutions of greater public partici- on the self-organizing capacities of places to

pation and accountability seem inadequate, become more resilient. As Hudson (2010)

since they continue to be underpinned by a observes, capitalism is itself highly resilient at

notion of adaptive management that subordi- a systemic level, confounding successive pre-

nates communities and local groups to the dictions of its imminent demise through its

imperative of greater resilience as defined by capacity for periodic reinvention and restructur-

external experts and policy-makers. At the same ing, as captured by Schumpeter’s notion of crea-

time, the characteristic ecological emphasis on tive destruction (Schumpeter, 1943). This

self-organization and polycentric institutions means that the sources of instability and crisis

(Folke, 2006; Ostrom, 2005) remains divorced that affect urban and regional economies can

from the sociopolitical realities of state author- be seen as internal to capitalism as a system,

ity and unequal power relations. rather than as immutable external forces to

which local groups and communities must con-

tinually adapt. Paradoxically, the long-term suc-

V Scale and the localization of cess of capitalism is predicated upon the

resilience thinking periodic undermining of the resilience of certain

The importation of the ecological approach into local and regional economies, which are vulner-

the social sciences has served to privilege spa- able to capital flight and crisis in the face of

tial sites and scales such as cities, regions and competition from other places offering more

local communities, which are implicitly equated profitable investment opportunities (Smith,

with ecosystems, and viewed as autonomous 1990). The extent of such vulnerability is condi-

and subject to the same principles of self- tioned by the operation of different forms and

organization. In this sense, resilience thinking varieties of capitalism (Peck and Theodore,

is characterized by a certain imprecision in sca- 2007), with ‘liberal market economies’, for

lar terms, treating different scales similarly as instance, proving more permissive of uneven

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

262 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

spatial development and regional crises than (2008) with reference to the foreclosure crisis

‘coordinated market economies’ which tend to in the USA, whereby forms of federal deregula-

have maintained ameliorative policy frameworks tion in the 1980s encouraged a wave of innova-

(Hall and Soskice, 2001; Peck and Theodore, tion through the introduction of new financial

2007). As the contemporary politics of austerity instruments which actually undermined house-

in Europe and the USA demonstrate, the costs hold resilience in the long run. In another study,

of adaptation and restructuring are often externa- Swanstrom et al. (2009) examine how metropol-

lized by capital and the state onto particular com- itan areas in the USA have responded to the

munities and segments of labour at times of crisis foreclosure crisis, defining resilience in terms

and restructuring in the interests of ‘general’ eco- of three main processes: the redeployment of

nomic recovery and renewal. assets or alteration of organizational routines;

The equation of cities and regions with eco- collaboration within and across the public, pri-

systems reinforces the neoliberalization of vate and non-profit sectors; and the mobiliza-

urban and regional development policy, foster- tion and capturing of resources from external

ing an internalist conception which locates the sources. Crucially, while ‘horizontal’ collabora-

sources of resilience as lying within the scale tion between public, private and non-profit

in question. By contrast, the need to position cit- actors within metropolitan areas is important,

ies and regions within wider circuits of capital Swanstrom et al. (2009) argue that the effects

and modes of state intervention is apparent from of this will remain limited without support from

some preliminary empirical analyses of the ‘vertical’ policies emanating from the state and

dynamics of regional resilience (Martin, 2011; federal scales of government. Only these insti-

Simmie and Martin, 2010). Defining resilience tutions can provide the necessary level of

in terms of regions’ resistance to, and recovery resources to support local foreclosure preven-

from, major economic shocks, Martin (2011) tion and neighbourhood recovery activities.

examines the responses of UK regions to the The vacuous yet ubiquitous notion that com-

major recessions of 1979–1983, 1990–1993 and munities ought to be ‘resilient’ can be seen as

2008–2010. While prosperous regions such as particularly troubling in the context of austerity

South East England invariably tend to emerge and reinforced neoliberalism (Peck et al., 2010).

as more resilient than less favoured ones such In the UK, this is being accompanied by a

as North East England, this is not simply the renewed invocation of localism and community

result of divergent endogenous capacities for through the government’s ‘Big Society’

innovation and leadership, but is bound up with programme (Featherstone et al., 2012). This

the operation of a range of wider political and provides a crucial supplement to neoliberal dis-

economic relations which have positioned the courses (see Joseph, 2002), serving to fill an

former as a global ‘hot-spot’ and the latter as underlying void created by the privileging of

economically marginal (Massey, 2007). As market rationalities over social needs (Derrida,

neoliberal modes of regulation have supported 1976; Sheppard and Leitner, 2010). The effect

the interests of advanced finance in the City of is to maintain and legitimize existing forms of

London, regions such as the North East have social hierarchy and control (Joseph, 2002),

borne the economic and social costs of capitalist drawing upon long-standing Conservative tradi-

adaptation in terms of deindustrialization and tions of middle-class voluntarism and social

attendant levels of social disadvantage (Hudson, responsibility (Featherstone et al., 2012). We

1989). cite the ‘Big Society’ agenda here to emphasize

The crucial role of national states in shaping the potential relationship between reductions in

levels of resilience is illustrated by Swanstrom public expenditure and attacks on the state as an

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 263

active agent of redistribution and service provi- conservative insofar as it privileges the restora-

sion, on the one hand, and arguments for greater tion of existing systemic relations rather than

local and community resilience, on the other their transformation. Yet calls for alternative

(Cabinet Office, 2011). This discursive and utopian visions and transformations of social

material policy milieu promises to have relations are themselves not inherently socially

profoundly uneven effects, with disadvantaged just and progressive. Nor does the history of the

communities having fewer material resources, 20th century suggest that decommodification

professional skill sets, and stocks of social and state socialism necessarily lead to ethical

capital to ‘step up’ to fill the gaps created by and desirable social relations. Rather, as we

state retrenchment (Cox and Schmuecker, noted earlier, Spivak (2012) suggests that the

2010; Fyfe, 2005). It is in this context that the immediate and most pressing task is to ‘culti-

promotion of resilience among low-income vate the will to social justice’ among everyday

communities strikes us as particularly danger- people.

ous, insofar as it normalizes the uneven effects As a first step in that direction, we offer a

of neoliberal governance and invigorates the politics of resourcefulness. Developed in close

trope of individual responsibility with a conversation with our collaborators in the

renewed ‘community’ twist. At the same time, Govan Together project, resourcefulness is

resilience-oriented policy discursively and meant to problematize both the uneven distribu-

ideologically absolves capital and the state from tion of material resources and the associated

accountability to remediate the impacts of their inability of disadvantaged groups and commu-

practices and policies. Implicit, then, in resili- nities to access the levers of social change. In

ence discourse is the notion that urban and this sense, a politics of resourcefulness attempts

regional policy should enable communities to to engage with injustice in terms of both redis-

constantly remake themselves in a manner that tribution and recognition towards a vision of

suits the fickle whims of capital with limited resourceful communities, cities and regions.

support from the state. Not only does this The normative vision that underpins resource-

approach hold little promise of fostering greater fulness is one in which communities have the

social justice, it also elevates the operation of capacity to engage in genuinely deliberative

the market over the well-being of the commu- democratic dialogue to develop contestable

nities that are meant to be resilient. alternative agendas and work in ways that

meaningfully challenge existing power rela-

tions. In particular, our approach is conscious

VI Towards a politics of of the need for progressively orientated groups,

resourcefulness organizations and communities to avoid forms

In this section, we outline our favoured concept of politics and praxis that are prone to vanguard-

of resourcefulness as an alternative to resili- ism, whereby a small group leads in a top-down,

ence, which we have argued is ill suited to the ideologically driven way, and the often uninten-

animation of more progressive and just social tional recreation of unequal social relations

relations. Acknowledging that the concept itself (Cumbers et al., 2008; Mason and Whitehead,

requires more empirical research in conversa- 2012).

tion with a wide range of communities and Second, rather than being externally defined

groups, we argue that resourcefulness has the by government agencies and experts, resource-

potential to overcome the three main limitations fulness emphasizes forms of learning and mobi-

of resilience that we have emphasized. As lization based upon local priorities and needs as

we have argued, resilience is inherently identified and developed by community activists

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

264 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

and residents. In this sense, our conception of clearly identifiable condition amenable to

resourcefulness takes the normative desirability empirical measurement or quantification. As a

of democratic self-determination as its funda- relational concept, resourcefulness cannot be

mental starting point. The issue of community understood as something communities possess

influence and control has been explored in the to varying degrees. It is the act of fostering

geographical literature, specifically with respect resourcefulness, not measuring it or achieving

to autonomy (Clark, 1984; Lake, 1994). While it, that should motivate policy and activism.

some have defined autonomy as an objective We identify the following four key elements as

condition in which localities are somehow inde- an initial framework, recognizing that additional

pendent of wider social relations, DeFilippis research is needed to further elaborate the con-

(2004) usefully argues that autonomy is a rela- cept and practice of community resourcefulness.

tional concept, which should be understood as a

process, not as a property that an entity might (1) Resources. While foregrounding the

possess. Following Lake (1994), DeFilippis importance of resources in a conception

(2004: 30) argues that local autonomy is ‘the of resourcefulness might seem somewhat

ever-contested and never complete ability of tautological, we want to emphasize the

those within the locality to control the institutions extent to which our conception of resour-

and relationships that define and produce the cefulness emphasizes material inequality

locality’. and issues of maldistribution. This point

Third, as we have emphasized, resilience is crucial in distinguishing resourcefulness

policy tends to reify different spatial scales such from mainstream conceptions of resilience

as the urban and regional as discrete, self- which take existing social relations for

organizing units, requiring local actors to adapt granted (Swanstrom, 2008). Rather than

to a turbulent external environment which is functioning as an internal characteristic

taken for granted and naturalized. By contrast, of a community, resourcefulness is a mate-

the concept of resourcefulness is both more rial property and a relational term that

scale-specific in focusing attention on the need seeks to problematize the often profound

to build capacities at community level, and inequalities in the distribution of resources

outward-looking in emphasizing the need to by the state that further disadvantage low-

foster and maintain relational links across space income communities. The resources to

(Cumbers et al., 2008). In this sense, we which we refer here include not only orga-

advocate resourcefulness as part of a progres- nizing capacity, spare time and social cap-

sive and expansive scalar politics that both ital, but also public- and third-sector

addresses local issues and appreciates systemic resources and investments on a par with

challenges. The conception of the local that the wealthiest communities.

underpins resourcefulness is not only spatially (2) Skill sets and technical knowledge. Com-

grounded in identifiable local spaces, but also munities with expertise in governmental

open and relational in terms of both recognizing procedures, financial and economic

the wider politics of justice that often underpin knowledge, basic computing and technol-

local activism and emphasizing the need for ogy are much better positioned to take

alliances between community groups and nuanced positions on public policy issues,

broader social movements (Cumbers et al., as well as to propose policies and imagine

2008). feasible alternatives and the concrete steps

Resourcefulness, as we conceive of it, is necessary to enact those alternatives.

better understood as a process, rather than as a While, like Fischer (2000), we regret the

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 265

turn towards technocratic public policy- of existing resources and argue for and

making and away from a model based pursue new resources. Additionally, rec-

upon the democratic debate of normative ognition confers group status upon the

ideals, we argue that resourceful commu- community in question on the basis of

nities must have at least some technical common attributes and a shared under-

knowledge and skill for communicating standing that the community is itself a sub-

that knowledge. ject of rights and a receiving body for state

(3) Indigenous and ‘folk’ knowledge. Alter- resources.

native and shared ways of knowing gener-

ated by experiences, practices and A politics of resourcefulness highlights the

perceptions are important spaces of material and enduring challenges that margina-

knowledge production about the world: lized communities face in conceiving of and

what Escobar (2008) terms ‘alternative engaging in the kinds of activism and politics

modernities’. Moreover, they can also pro- that are likely to facilitate transformative

duce critical ‘myths’ from which resource- change. Unlike resilience policy and activism,

ful communities may draw. Here, the concept of resourcefulness emphasizes the

following Innes (1990), ‘myth’ refers not challenges that many grassroots endeavours

to made-up stories, but rather to origin face in terms of organizational capacity. While

stories (Haraway, 1991) and explanatory many Marxist-influenced geographers are quick

frameworks that weave together norma- to point out the need for anti-capitalist endea-

tive and observational knowledge, and vours to link up (Brenner et al., 2010; Harvey,

serve as the guiding framework for shared 1996), they often overlook the very immediate

visions. For example, a group of commu- challenges that organizations and individual

nity activists in the disadvantaged district activists face. These include time, access to

of Govan, Glasgow (UK), with whom we knowledge and essential skill sets, and the capa-

collaborated, mobilized the myth of past cities for organizing and maintaining associated

Gaelic Highlander life, and the folk ways organizational structures to facilitate the kind of

and knowledges that emerged from that holistic, ongoing critique that might support

mythology, as a grounding for their alter- sustained activism, the lack of which many

native vision of social relations. There are critical political economists have lamented

a whole number of ways in which this kind (Brenner et al., 2010; Harvey, 1996). In this

of knowledge could become inward- sense, a politics of resourcefulness challenges the

looking and nostalgic, but the kinds of folk conservatism of resilience policy and activism by

knowledge that ultimately cultivate attempting to foster the tools and capacities for

resourcefulness will necessarily be as communities to carve out the discursive space

attentive to difference as they are to and material time that sustained efforts at civic

commonality. engagement and activism, as well as more radical

(4) Recognition. Philosophers of justice and campaigns, require.

oppression have emphasized the impor- None of the four dimensions outlined above

tance and value of cultural recognition as should be seen as sole preserves of resourceful-

a requisite condition of justice (Taylor, ness, operating, instead, as sites of contestation

1994; Young, 1990). Recognition pro- and struggle between different social forces.

motes a sense of confidence, self-worth Each is vulnerable to capture and co-option by

and self- and community-affirmation that powerful political and economic actors such as

can be drawn upon to fuel the mobilization the state (Bohm et al., 2010). This is apparent,

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

266 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

for instance, in the growing emphasis on public away from the glare and intensity of globaliza-

participation, local institutions and the harnes- tion to consider how they might make them-

sing of community knowledge within main- selves less vulnerable to future economic and

stream conceptions of resilience derived from environmental catastrophe. Nor are we intrinsi-

ecology (Folke, 2006; Lebel et al., 2006). In cally opposed to the integration of social and

essence, it is the interrelations between the four ecological perspectives; rather, we emphasize

dimensions and their yoking to a democratic the need to pay close attention to the terms upon

politics of self-determination (independent of which such integration takes place (Agder,

the imperative of adaptation to external forces 2000). Yet, as we have argued, promoting resi-

such as climate change or globalization) that lience in the face of the urgent crises of climate

distinguishes our concept of resourcefulness. change and global recession actually serves to

At the same time, the adoption of a relational naturalize the ecologically dominant system of

approach helps to ensure that a politics of global capitalism. It is the ‘internal’ workings

resourcefulness can transcend the long- of this ‘system’, we contend, that generate dis-

standing tension between autonomous action turbance and instability and shape the uneven

and dependence upon the state (Bohm et al., ability of communities, cities and regions to

2010). As part of an expansive spatial politics, cope with crisis. Our fundamental problem with

there is scope for community groups to feed into the mobilizing discourse of resilience is that it

broader campaigns and social movements that places the onus squarely on local actors and

seek to challenge neoliberal policy frameworks communities to further adapt to the logics and

at the national and supranational scales (Bren- implications of global capitalism and climate

ner et al., 2010; Cumbers et al., 2008). By fos- change. This apolitical ecology entails the

tering such wider connections, resourceful and subordination and corralling of the social within

progressive forms of localism (see Featherstone the framework of socio-ecological systems.

et al., 2012) can overcome the ‘local trap’ iden- Convergence of thinking around the notion of

tified by radical scholars (Purcell, 2006), repre- resilience is resulting in the evacuation of the

senting more than particularisms or ‘mere political as the underlying question of what kind

irritants’ to the neoliberal capitalist machine of communities and social relations we want to

(Brenner et al., 2010; Harvey, 1996). create is masked beneath the imperative of tran-

sition (Swyngedouw, 2007).

This intervention has been prompted by our

VII Conclusions particular concern about the adoption of resili-

While we have spent the bulk of this article cri- ence thinking by community activists, opposi-

ticizing the conception of resilience as it has tional groups and critical social scientists and

been deployed by policy-makers, social scien- geographers, in addition to government agen-

tists and progressive campaign groups, we cies, policy-makers and business organizations.

recognize the motives of these actors in being As we have argued, by uncovering its origins,

drawn towards resilience as a desirable quality affiliations and consequences, resilience think-

to foster. Having weathered a rapid and unfor- ing has become implicated within the hegemo-

giving shift in the global political economy and nic modes of thought that support global

the associated fracturing of the welfare state and capitalism, providing a further source of natura-

social democracy over the past 30 years, to be lization through complex systems theory. While

faced with a new economic and fiscal crisis the unsuitability of resilience in the social

since 2008, it is understandable that activists sphere is rooted in the underlying ecological

and policy-makers would be inclined to turn concept, its regressive effects have been greatly

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 267

accentuated by its entanglement in neoliberal Notes

modes of governance. This makes its adoption 1. Thanks to Wendy Larner for bringing the work of this

by oppositional groups and critical analysts organization to our attention.

deeply problematic. In response, we offer the 2. As such, our purpose is not to examine the geographical

alterative concept of resourcefulness as a more circulation and mutation of resilience policy through a

productive means of challenging the hegemony range of elite networks as per the ‘policy mobilities’ lit-

of neoliberal capitalism. This is designed to erature (Peck, 2011), but to assess the ramifications of

open up debate beyond the closures of resilience this discourse in terms of the framing of local and

regional development.

thinking, foregrounding the fundamental ques-

3. This is not meant to suggest that capitalism is always

tion of transition ‘to where, and from what’

the most pressing process or dominant social relation,

(Trapese Collective, 2008: 3). Resourcefulness and nor is it to suggest that all manner of politics must

focuses attention upon the uneven distribution be overtly anti-capitalist in order to have potential to

of resources within and between communities undermine oppressive social relations. In relation to

and maintains an openness to the possibilities urban and regional development, however, we maintain

of community self-determination through local that capitalism is the most powerful set of processes at

skills and ‘folk’ knowledge. For resourcefulness work.

to become part of a ‘movement of thought that is 4. Our critique follows resilience thinking in moving

truly counter-systematic’ is, however, depen- between these different scales, reflecting their common

dent upon more than the intellectual abandon- social and ideological construction.

ment of complex systems theory (Walker and 5. The Government Offices for the Regions were abol-

ished by the incoming Coalition Government in 2010

Cooper, 2011: 157). It also requires the cultiva-

and the roles of the Regional Resilience Teams have

tion of links with community groups and social

been largely absorbed by Civil Contingencies Secretar-

movements as part of an expansive spatial poli- iat in the Cabinet Office.

tics that aims to both foster translocal relations 6. As Walker and Cooper (2011) argue, Holling’s later

between particular sites and exemplars and work on adaptive cycles and social-ecological systems

challenge the national and supranational institu- (Holling, 2001) resonates with the writings of Hayek

tions that support the operation of global (1945), whose notion of ‘spontaneous order’ through

capitalism. market exchange informed a growing engagement with

complexity science and systems theory in his late career.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Paul Routledge, Gehan MacLeod, Wendy References

Larner, Andrew Cumbers, Andy Pike, Robert Agder WN (2000) Social and ecological resilience: Are

McMaster, Dave Featherstone, Kendra Strauss, they related? Progress in Human Geography 24:

Denis Fischbacher-Smith, Katherine Hankins and 347–364.

Verene Nicolas for conversations around resilience Anderson B (2010) Preemption, precaution, preparedness:

and resourcefulness and for comments on previous Anticipatory action and future geographies. Progress in

versions of this paper. As always, we remain Human Geography 34: 777–798.

solely responsible for any remaining errors or Bailey I, Hopkins R, and Wilson G (2010) Some things

misrepresentations. old, some things new: The spatial representations of the

peak oil relocalisation movement. Geoforum 41:

595–605.

Funding Barnes TJ (1997) Theories of accumulation and regulation:

This research received no specific grant from any Bringing life back into economic geography – introduc-

funding agency in the public, commercial, or not- tion to section three. In Lee R and Wills J (eds) Geogra-

for-profit sectors. phies of Economies. London: Edward Arnold, 231–247.

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

268 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

Bohm D, Dinerstein A, and Spicer A (2010) (Im)possibil- DeFilippis J (2004) Unmaking Goliath: Community

ities of autonomy: Social movements in and beyond Control in the Face of Global Capital. New York:

capital, the state and development. Social Movement Routledge.

Studies 9: 17–32. DeFilippis J, Fisher R, and Shragge E (2006) Neither

Brenner N (2004) New State Spaces: Urban Governance romance nor regulation: Re-evaluating community.

and the Rescaling of Statehood. Oxford: Oxford International Journal of Urban and Regional Research

University Press. 30: 673–689.

Brenner N, Peck J, and Theodore N (2010) Variegated Derrida J (1976) Of Grammatology. Baltimore, MD: Johns

neoliberalisation: Geographies, modalities, pathways. Hopkins University Press.

Global Networks 10: 182–222. Egeland B, Carlson E, and Sroufe L (1993) Resilience as

Bristow G (2010) Critical Reflections on Regional Compe- process. Development and Psychopathology 5:

titiveness. Abingdon: Routledge. 517–528.

Cabinet Office (2010) Emergency response and recovery: Escobar A (2008) Territories of Difference: Place, Move-

Regional arrangements. V3: last updated 05/04/2010. ments, Life, Redes. Durham, NC: Duke University

London: UK Government. Available at: http://www. Press.

cabinetoffice.gov.uk/content/emergency-response-reg Evans JP (2011) Resilience, ecology and adaptation in the

ional-arrangements. experimental city. Transactions of the Institute of Brit-

Cabinet Office (2011) Strategic National Framework on ish Geographers 36: 223–237.

Community Resilience. London: UK Government. Featherstone D, Ince A, MacKinnon D, Cumbers A, and

Available at: http://www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk/sites/ Strauss K (2012) Progressive localism and the con-

default/files/resources/Strategic-National-Framework- struction of political alternatives. Transactions of the

on-Community-Resilience_0.pdf. Institute of British Geographers 37: 177–182.

Carnegie UK Trust (2011) Exploring Community Resili- Fischer F (2000) Citizens, Experts and the Environment:

ence in Times of Rapid Change. Dunfermline: Fiery The Politics of Local Knowledge. Durham, NC: Duke

Spirits Community of Practice. University Press.

Clark G (1984) A theory of local autonomy. Annals of Florida R (2002) The Rise of the Creative Classes. New

the Association of American Geographers 74: 195– York: Basic Books.

208. Folke C (2006) Resilience: The emergence of a perspec-

Coaffee J and Murakami Wood D (2006) Security is com- tive for social-ecological systems analysis. Global

ing home: Rethinking scale and constructing resilience Environmental Change 16: 253–267.

in the global urban response to terrorist risk. Interna- Fraser N (1996) Justice Interruptus: Critical Reflec-

tional Relations 20: 503–517. tions on the Post-Socialist Condition. New York:

Coaffee J and Rogers P (2008) Rebordering the city for Routledge.

new security challenges: From counter-terrorism to Fyfe NR (2005) Making space for ‘neo-communitarian-

community resilience. Space and Polity 12: 101–118. ism’? The third sector, state and civil society in the

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Organization UK. Antipode 37: 536–557.

(CSIRO) (2007) Urban Resilience Research Prospec- Gandy M (2002) Concrete and Clay: Reworking Nature

tus. Australia: CSIRO. in New York City. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Cox E and Schmuecker K (2010) Growing the Big Society: Gordon J (1978) Structures. London: Penguin.

Encouraging Success in Social and Community Enter- Hall P and Soskice D (eds) (2001) Varieties of Capitalism:

prises in Deprived Communities. Newcastle-upon- The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advan-

Tyne: Institute for Public Policy Research. tage. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cumbers A, Nativel C, and Routledge P (2008) Labour Haraway D (1991) Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The

agency and union postionalities in global production reinvention of nature. New York: Routledge.

networks. Journal of Economic Geography 8: Harvey D (1996) Justice, Nature and the Geography of

369–387. Difference. Oxford: Blackwell.

Dawley S, Pike A, and Tomaney J (2010) Towards the resi- Hayekvon F (1945) The use of knowledge in society.

lient region? Local Economy 25: 650–667. American Economic Review 25: 519–530.

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

MacKinnon and Derickson 269

Held D and McGrew A (2002) Globalisation/anti-globali- Lentzos F and Rose N (2009) Governing insecurity: Con-

sation. Cambridge: Polity Press. tingency planning, protection, resilience. Economy and

Hill EW, Wial H, and Wolman H (2008) Exploring Society 38: 230–254.

regional resilience. Working Paper 2008-04. Berkeley, MacKinnon D (2011) Reconstructing scale: Towards a

CA: Macarthur Foundation Research Network on new scalar politics. Progress in Human Geography

Building Resilient Regions, Institute for Urban and 35: 21–36.

Regional Development, University of California. MacKinnon D, Cumbers A, and Chapman K (2002) Learn-

HM Government (2010) Decentralisation and the ing, innovation and regional development: A critical

Localism Bill: An Essential Guide. London: HM appraisal of recent debates. Progress in Human

Government. Geography 26: 293–311.

Holling CS (1973) Resilience and stability of ecological Martin R (2011) Regional economic resilience, hysteresis

systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics and recessionary shocks. Plenary paper presented at the

4: 1–23. Annual International Conference of the Regional

Holling CS (2001) Understanding the complexity of Studies Association, Newcastle, 17–20 April.

economic, ecological and social systems. Ecosystems Mason K and Whitehead M (2012) Transition urbanism

4: 390–405. and the contested politics of ethical place making.

Hudson R (1989) Wrecking a Region: State Policies, Party Antipode 44: 493–516.

Politics and Regional Change in North East England. Massey D (2007) World City. Cambridge: Polity Press.

London: Pion. Norris FH, Stevens SP, Pfefferbaum B, Wyche KF, and

Hudson R (2010) Resilient regions in an uncertain world: Pfefferbaum RL (2008) Community resilience as a

Wishful thinking or a practical reality? Cambridge metaphor, theory, set of capacities, and strategy for

Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3: 11–25. disaster readiness. American Journal of Community

Innes J (1990) Knowledge and Public Policy: The Search Psychology 41: 127–150.

for Meaningful Indicators. New Brunswick: Transac- O’Malley P (2010) Resilient subjects: Uncertainty, war-

tion Publishers. fare and liberalism. Economy and Society 39: 488–508.

Jessop B (2000) The crisis of the national spatio-temporal Ostrom E (2005) Understanding Institutional Diversity.

fix and the tendential ecological dominance of globalis- Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

ing capitalism. International Journal of Urban and Otto-Zimmerman K (2011) Building the global adaptation

Regional Research 24: 323–360. community. Local Sustainability 1: 3–9.

Joseph M (2002) Against the Romance of Community. Peck J (2010) Constructions of Neoliberal Reason.

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Katz C (2004) Growing Up Global: Economic Restructur- Peck J (2011) Geographies of policy: From transfer-

ing and Children’s Everyday Lives. Minneapolis, MN: diffusion to mobility-mutation. Progress in Human

University of Minnesota Press Geography 35: 773–797.

Lake R (1994) Negotiating local autonomy. Political Peck J and Theodore N (2007) Variegated capitalism.

Geography 13: 423–442. Progress in Human Geography 31: 731–772.

Lang T (2010) Urban resilience and new institutional the- Peck J and Tickell A (1994) Searching for a new institu-

ory: A happy couple for urban and regional studies. In: tional fix: The after-Fordist crisis and the global-local

Müller B (ed.) German Annual of Spatial Research and disorder. In Amin A (ed.) Post-Fordism: A Reader.

Policy 2010. Berlin: Springer, 15–24. Oxford: Blackwell, 280–315.

Larner W and Moreton S (2012) Regeneration, resistance, Peck J and Tickell A (2002) Neoliberalising space. Anti-

or resilience: The Co-exist Project. Unpublished paper pode 34: 380–404.

presented at ‘In, Against, and Beyond Neoliberalism’ Peck J, Theodore N, and Brenner N (2010) Postneoliberal-

Conference, 21–23 March, University of Glasgow. ism and its malcontents. Antipode 42: 94–116.

Lebel L, Anderies J, Campbell B, Folke C, Hatfield-Dodds Pickett STA, Cadenasso ML, and Grove JM (2004) Resili-

S, Hughes TP, et al. (2006) Governance and the capac- ent cities: Meanings, models, and metaphor for inte-

ity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological grating the ecological, socio-economic, and planning

systems. Ecology and Society 11(1): Article 19. realms. Landscape and Urban Planning 69: 369–384.

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

270 Progress in Human Geography 37(2)

Pike A, Dawley S, and Tomaney J (2010) Resilience, adap- Swanstrom T, Chapple K, and Immergluck D (2009)

tation and adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Regional resilience in the face of foreclosures: Evi-

Economy and Society 3: 59–70. dence from six metropolitan areas. Working Paper

Pincetl S (2010) From the sanitary city to the sustainable 2009-05. Berkeley, CA: Macarthur Foundation

city: Challenges to institutionalising biogenic (nature’s Research Network on Building Resilient Regions,

services) infrastructure. Local Environment 15: 43–58. Institute for Urban and Regional Development, Univer-

Purcell M (2006) Urban democracy and the local trap. sity of California.

Urban Studies 43: 1921–1941. Swyngedouw E (2007) Impossible/undesirable ‘sustain-

Schumpeter JA (1943) Capitalism, Socialism and Democ- ability’ and the post-political condition. In Krueger R

racy. London: Allen and Unwin. and Gibbs D (eds) The Sustainable Development Para-

Sheppard E and Leitner H (2010) Quo vadis neoliberal- dox. New York: Guilford Press, 13–40.

ism? The remaking of global capitalist governance Swyngedouw E and Heynen N (2003) Urban political ecol-

after the Washington Consensus. Geoforum 45: ogy, justice and the politics of scale. Antipode 35:

185–194. 898–918.

Simmie J and Martin R (2010) The economic resilience of Taylor C (1994) Multiculturalism. Princeton, NJ: Prince-

regions: Towards an evolutionary approach. Cambridge ton University Press.

Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 3: 27–44. Trapese Collective (2008) The rocky road to a real transi-

Smith N (1990) Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and tion: The Transition Towns Movement and what it

the Production of Space, second edition. Oxford: means for social change. Available at: http://trapese.

Blackwell. clearerchannel.org/resources/rocky-road-a5-web.pdf.

Spivak G (2012) A conversation with Gayatri Spivak. Paper Walker J and Cooper M (2011) Genealogies of resilience:

presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of From systems ecology to the political economy of crisis

American Geographers, 24–29 February, New York. adaptation. Security Dialogue 43: 143–160.

Swanstrom T (2008) Regional resilience: A critical Wolfe DA (2010) The strategic management of core cities:

examination of the ecological framework. Working Path dependence and economic adjustment in resilient

Paper 2008-7. Berkeley, CA: Macarthur Foundation regions. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and

Research Network on Building Resilient Regions, Insti- Society 3: 139–152.

tute for Urban and Regional Development, University of Young IM (1990) Justice and the Politics of Difference.

California. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Downloaded from phg.sagepub.com at MEMORIAL UNIV OF NEWFOUNDLAND on July 31, 2014

You might also like

- PiHG Published VersionDocument18 pagesPiHG Published Versionfirdausar08No ratings yet

- Situating Social Change in Resilience ResearchDocument16 pagesSituating Social Change in Resilience ResearchDavid Alejandro FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Beins 2019 Societal Dynamics inDocument17 pagesBeins 2019 Societal Dynamics inherfitagurningNo ratings yet

- Society For American Archaeology American AntiquityDocument38 pagesSociety For American Archaeology American AntiquityAdriana BernalNo ratings yet

- Nothing Lasts Forever Environmental Discourses On The Collapse of Past SocietiesDocument52 pagesNothing Lasts Forever Environmental Discourses On The Collapse of Past SocietiesBüşra Özlem YağanNo ratings yet

- Social Vulnerability To Disasters 2nd Thomas Solution ManualDocument11 pagesSocial Vulnerability To Disasters 2nd Thomas Solution ManualDanielle Searfoss100% (39)

- rsq004Document8 pagesrsq004diecagonosNo ratings yet

- Sapiens 1626Document13 pagesSapiens 1626eftychidisNo ratings yet

- Middleton2012 Article NothingLastsForeverEnvironment PDFDocument51 pagesMiddleton2012 Article NothingLastsForeverEnvironment PDFmark_schwartz_41No ratings yet

- Structure and Process in The Study of Disaster Resilience: K. J. TierneyDocument8 pagesStructure and Process in The Study of Disaster Resilience: K. J. TierneyNofrita Gracella Sampo-MbataNo ratings yet

- (2013) Joseph - Resilience As Embedded Neoliberalism. A Governmentality ApproachDocument16 pages(2013) Joseph - Resilience As Embedded Neoliberalism. A Governmentality ApproachCarlos Araneda-UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- Sociological Imagination in A Time of Climate ChangeDocument6 pagesSociological Imagination in A Time of Climate ChangeNowrin MohineeNo ratings yet

- Less and More - Conceptualising Degrowth TransformationsDocument9 pagesLess and More - Conceptualising Degrowth TransformationstalaNo ratings yet

- Demeritt 2002Document25 pagesDemeritt 2002Janak TripathiNo ratings yet

- Governing Resilience Building in Thailand's Tourism-Dependent Coastal Communities: Conceptualising Stakeholder Agency in Social-Ecological SystemsDocument12 pagesGoverning Resilience Building in Thailand's Tourism-Dependent Coastal Communities: Conceptualising Stakeholder Agency in Social-Ecological SystemsJAIME ANTONIO MARTINEZ HERNANDEZNo ratings yet