Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Baudrillard's Simulacrum: The End of Visibility

Uploaded by

k0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views2 pagesOriginal Title

Untitled

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

3 views2 pagesBaudrillard's Simulacrum: The End of Visibility

Uploaded by

kCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Baudrillard’s Simulacrum:

The End of Visibility

The involuntary Platonist

Baudrillard has been often criticized for his bleak interpretation of

postmodern culture. In place of his “‘sour’ post-structuralism,” we are

urged to accept “a ‘sweet’ post-structuralism…for example, Derridean

post-structuralism, with its emphasis upon the delirious free play of the

signifier” (Coulter-Smith 1997: 92). Baudrillard is strangely out of place

in this technological age because he is too apocalyptic and at the same

time too ‘romantic’ (read ‘neo-Platonic’) in his inability to overcome the

melancholy provoked by “the loss of the real, the natural and the hu-

man” (98). Scott Durham’s Phantom Communities: the Simulacrum and

the Limits of Postmodernism is representative of this line of criticism.

Durham distinguishes two different interpretations of the simulacrum—

that of Jameson and Baudrillard and, on the other hand, that of Foucault

and Deleuze. Durham finds Baudrillard’s version of the simulacrum as

“the non-representation of the object or as the non-participation in the

Idea” (1998: 8) a “strangely inverted Platonism, where the desire to

pass judgment on existence has survived the belief in any ‘true world’

in the name of which it might be judged”(86). Deleuze, on the other

hand, presents the simulacrum “in its daemonic aspect, as the positive

expression of metaphoric and creative ‘powers of the false’ (8). The

Deleuzian simulacrum is not a simple imitation but rather the challeng-

ing of the very idea of a model or a privileged position; it is rooted in

Deleuze’s interpretation of Nietzsche’s will to power as a creative power

of falsification, metamorphosis and becoming (11). That Durham prefers

the Deleuzian simulacrum to Baudrillard’s “performative simulation

model” (54) is clear from his decision to link the simulacrum to memory

rather than to communication, thereby recuperating the simulacrum as

that through which “one recalls, awaits, or imagines what is virtual or

unactualized in the very object that one sees” (17-18).

172 The Image in French Philosophy

Echoing some of the familiar criticisms of Bergson, other critics warn

against Baudrillard’s seductive, aphoristic style, which merely disguises

what are generally insubstantial ideas or, if we were to go with Durham,

merely an inverted form of Platonism. Finally, there are those who point

out that the simple fact that much of the criticism on Baudrillard has

been written by his devoted confirms that his works “[can] be regarded

as little more than strings of aphorisms, and thus not worthy of critical

engagement” (Willis 1997: 138). There is a strange incongruity between

these two critiques: according to the first, Baudrillard is not sufficiently

postmodernist, and according to the second he is too postmodernist,

as his fragmented, aphoristic style testifies. Rather than discrediting

Baudrillard’s work these criticisms present it as worthy of critical atten-

tion, especially now that postmodernism is drawing closer and closer to

the brink of self-exhaustion and we are less and less interested in “the

sweet and delirious free play of the signifier.”

The real: Bergson and Baudrillard

In many ways Baudrillard’s ontology of the image gestures back to,

while also reworking, Bergson’s image ontology in Matter and Memory.

Although both Bergson and Baudrillard begin their analyses by exam-

ining the ontological and epistemological significance of light as the

prime guarantor of the real, their concepts of the image, and therefore

of the real, differ significantly. As we saw in chapter one, Bergson does

not distinguish an image from a thing: things do not ‘have’ images

and neither do we ‘produce’ their images. Insofar as they are made of

light vibrations, things are already images or, taken more metaphori-

cally, a thing is an image (or a representation) of the totality of images

from which perception isolates it like a picture. However, Baudrillard

regards images as capable of detaching themselves from things and ei-

ther preceding or following them: having lost their solidity things have

been dematerialized into images, reduced to their pre-given meanings.

Images, as such, are neither exclusively visual nor exclusively mental;

rather, Baudrillard emphasizes their pre(over)determination, their ex-

treme proximity to us, which makes them virtually invisible.

In Baudrillard’s work, then, the image becomes a metaphor, and a

deliberate misnomer, for the end of visibility. When everything has been

rendered visible, nothing is visible any more and we are left with im-

ages. The image is a sign of overexposure or oversignification. Bergson

describes the ‘production’ of images as a process of dissociation or

You might also like

- Iconography and Postmodernity, Literature and TheologyDocument25 pagesIconography and Postmodernity, Literature and TheologySPIROS LOUISNo ratings yet

- Harman Baudrillard EssayDocument16 pagesHarman Baudrillard EssayanarcisticNo ratings yet

- Anthro Capital FinalDocument26 pagesAnthro Capital FinalChristopher FuttyNo ratings yet

- Adorno LyotardDocument15 pagesAdorno LyotardBen FortisNo ratings yet

- Simulacra and Simulation Baudrillard and The MatrixDocument12 pagesSimulacra and Simulation Baudrillard and The MatrixJoseph MathenyNo ratings yet

- WWW Ubishops CA Baudrillardstudies Vol11 1 v11 1 Mcqueen HTMDocument36 pagesWWW Ubishops CA Baudrillardstudies Vol11 1 v11 1 Mcqueen HTMRene PerezNo ratings yet

- The Medusa Complex: A Theory of Stoned Posthumanism: Ted HiebertDocument16 pagesThe Medusa Complex: A Theory of Stoned Posthumanism: Ted Hiebertqaylyt09No ratings yet

- Thoughts On Simulacrum: Semiotics Postmodernism Consciousness RealityDocument2 pagesThoughts On Simulacrum: Semiotics Postmodernism Consciousness RealitygraceyyyNo ratings yet

- Just An Image Godard PhilosophyDocument23 pagesJust An Image Godard PhilosophyWilliam Joseph CarringtonNo ratings yet

- Baudrillard by Shree AwsareDocument12 pagesBaudrillard by Shree AwsareWilliam CheungNo ratings yet

- Chari Larsson Suspicious Images Iconophobia and The EtDocument9 pagesChari Larsson Suspicious Images Iconophobia and The EttobyNo ratings yet

- Representation and the Image in Heidegger and DerridaDocument14 pagesRepresentation and the Image in Heidegger and DerridaJamie DodsonNo ratings yet

- The Dual Nature of Figures in Art and LanguageDocument7 pagesThe Dual Nature of Figures in Art and LanguageJames Carro0% (1)

- Levin_Charles__Baudrillard_Critical Theory_and PsychoanalysisDocument19 pagesLevin_Charles__Baudrillard_Critical Theory_and PsychoanalysiszhangcypriotNo ratings yet

- Theory163 PDFDocument5 pagesTheory163 PDFmetamorfosisgirlNo ratings yet

- HyperrealityDocument1 pageHyperrealityCAMELIA BELGHAZINo ratings yet

- The Face on the Screen: Questions of Death, Recognition and Public MemoryFrom EverandThe Face on the Screen: Questions of Death, Recognition and Public MemoryNo ratings yet

- Simulacra and SimulationDocument3 pagesSimulacra and SimulationErin ZhanNo ratings yet

- Del Rio, On GodardDocument17 pagesDel Rio, On GodardMark TrentonNo ratings yet

- Simulacra and Simulation BackgroundDocument34 pagesSimulacra and Simulation BackgroundFreángel Pacheco67% (3)

- Jean BaudrillardDocument4 pagesJean BaudrillardHiram Tinoco100% (1)

- The Very Soil: An Unauthorized Critical Study of Puella Magi Madoka MagicaFrom EverandThe Very Soil: An Unauthorized Critical Study of Puella Magi Madoka MagicaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Burke Aesthetics and Postmodern CinemaDocument57 pagesBurke Aesthetics and Postmodern CinemaLefteris MakedonasNo ratings yet

- POWER AND SEDUCTION: BAUDILLARD'S CRITIQUE OF REIFICATIONDocument14 pagesPOWER AND SEDUCTION: BAUDILLARD'S CRITIQUE OF REIFICATIONgabay123No ratings yet

- Baudrillard's Simulacrum and Hyperreality in Alice and The MatrixDocument13 pagesBaudrillard's Simulacrum and Hyperreality in Alice and The MatrixMc Vharn CatreNo ratings yet

- Constructivism in The Works of GaimanDocument7 pagesConstructivism in The Works of GaimanensantisNo ratings yet

- Baudrillard and The MatrixDocument10 pagesBaudrillard and The MatrixcurupiradigitalNo ratings yet

- SimulacrumDocument1 pageSimulacrumJUANJOSEFOXNo ratings yet

- Blom2021 Chapter BachelardSPhenomenologyAndVertDocument18 pagesBlom2021 Chapter BachelardSPhenomenologyAndVertMaria HackerottNo ratings yet

- Georges Didi-Huberman - Picture Rupture. Visual Experience, Form and Symptom According To Carl EinsteinDocument25 pagesGeorges Didi-Huberman - Picture Rupture. Visual Experience, Form and Symptom According To Carl Einsteinkast7478No ratings yet

- Primary and SecondaryDocument1 pagePrimary and SecondaryGiovanni Mozo LaguraNo ratings yet

- Primary & Secondary ReflectionDocument1 pagePrimary & Secondary Reflectionsolidbhok86% (7)

- Echoing Hamlet, Anticipating Baudrillard in Dorian GrayDocument21 pagesEchoing Hamlet, Anticipating Baudrillard in Dorian GrayHristo BoevNo ratings yet

- Some Paradoxes of McLuhan's TetradDocument15 pagesSome Paradoxes of McLuhan's TetradKostasBaliotisNo ratings yet

- Adorno Subject ObjectDocument11 pagesAdorno Subject ObjectIsmar CestariNo ratings yet

- 9Document2 pages9japonpuntocomNo ratings yet

- Partial Glimpses of The Infinite - Borges and The Simulacrum JOnathan StuartDocument24 pagesPartial Glimpses of The Infinite - Borges and The Simulacrum JOnathan StuartLuciaNo ratings yet

- The Substance of Shadow: A Darkening Trope in Poetic HistoryFrom EverandThe Substance of Shadow: A Darkening Trope in Poetic HistoryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- JG Ballard and The Death of Affect, Part 2Document9 pagesJG Ballard and The Death of Affect, Part 2Jon MoodieNo ratings yet

- Derrida's Memoirs of The BlindDocument9 pagesDerrida's Memoirs of The BlindPaul WilsonNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Force in Baudrillard and DeleuzeDocument226 pagesAesthetic Force in Baudrillard and DeleuzerevocablesNo ratings yet

- Salvador Dali On Creative WritingDocument1 pageSalvador Dali On Creative WritingDanny DansecoNo ratings yet

- S. Malpas - Postmodern Consumption and SimulationDocument3 pagesS. Malpas - Postmodern Consumption and SimulationSakura Rei100% (1)

- Voldemort as an Anti-Philosopher (Plato) and as the Whole (Plutarch): On Harry Potter and its Philosophy of Freemasonry and Ancient Mystery CultsFrom EverandVoldemort as an Anti-Philosopher (Plato) and as the Whole (Plutarch): On Harry Potter and its Philosophy of Freemasonry and Ancient Mystery CultsNo ratings yet

- Prosopopoeia & DuererDocument1 pageProsopopoeia & Duererashley scarlettNo ratings yet

- AbsurdityDocument10 pagesAbsurdityBerkay TuncayNo ratings yet

- Understanding Baudrillard's Views on Media, Reality and Symbolic ExchangeDocument24 pagesUnderstanding Baudrillard's Views on Media, Reality and Symbolic ExchangeJuno ParungaoNo ratings yet

- Art Is Messianicity... by Anselm Haverkamp, Kritikos V.12, May - Dec. 2015Document15 pagesArt Is Messianicity... by Anselm Haverkamp, Kritikos V.12, May - Dec. 2015Anonymous uwoXOvNo ratings yet

- Simulacrum ADocument1 pageSimulacrum AJUANJOSEFOXNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Self and the Other: A Levinasian Reading of the Postmodern NovelFrom EverandEthics, Self and the Other: A Levinasian Reading of the Postmodern NovelNo ratings yet

- Geoffrey Bennington - "Aesthetics Interrupted The Art of Deconstruction"Document17 pagesGeoffrey Bennington - "Aesthetics Interrupted The Art of Deconstruction"XUNo ratings yet

- Adono Kafka Mimesis PDFDocument30 pagesAdono Kafka Mimesis PDFjdiego10No ratings yet

- The Ambiguity of Micro-UtopiasDocument8 pagesThe Ambiguity of Micro-UtopiaspolkleNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of Film: An Industry of Sex, A Form of Seduction (On Jean Baudrillard's Seduction and The Cinema)Document21 pagesThe Paradox of Film: An Industry of Sex, A Form of Seduction (On Jean Baudrillard's Seduction and The Cinema)cIrculoCienfuegosNo ratings yet

- Before the Law: Humans and Other Animals in a Biopolitical FrameFrom EverandBefore the Law: Humans and Other Animals in a Biopolitical FrameRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Kaja Silverman, "Fassbinder and Lacan: A Reconsideration of Gaze, Look, and Image"Document32 pagesKaja Silverman, "Fassbinder and Lacan: A Reconsideration of Gaze, Look, and Image"Chris Alan Jones100% (1)

- Guy Debord S Film Act A Matter of PerspeDocument12 pagesGuy Debord S Film Act A Matter of PerspePaolo TizonNo ratings yet

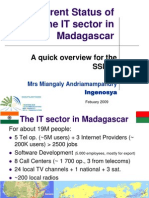

- Madagascar SslevMg v2Document11 pagesMadagascar SslevMg v2Thyan AndrianiainaNo ratings yet

- Assignments - 2017 09 15 182103 - PDFDocument49 pagesAssignments - 2017 09 15 182103 - PDFMena AlzahawyNo ratings yet

- MKTM028 FathimathDocument23 pagesMKTM028 FathimathShyamly DeepuNo ratings yet

- Consumer Notebook Price List For September 2010Document4 pagesConsumer Notebook Price List For September 2010Anand AryaNo ratings yet

- Standard JKR Spec For Bridge LoadingDocument5 pagesStandard JKR Spec For Bridge LoadingHong Rui ChongNo ratings yet

- What ATF - CVTF To Use For ToyotaDocument7 pagesWhat ATF - CVTF To Use For ToyotaSydneyKasongoNo ratings yet

- Chapter (3) Simple Stresses in Machine Parts: Design of Machine Elements I (ME-41031)Document80 pagesChapter (3) Simple Stresses in Machine Parts: Design of Machine Elements I (ME-41031)Dr. Aung Ko LattNo ratings yet

- OYO Case Study SolutionDocument4 pagesOYO Case Study SolutionVIKASH GARGNo ratings yet

- Mens Care Active Concepts PDFDocument19 pagesMens Care Active Concepts PDFFredy MendocillaNo ratings yet

- "A Study Consumer Satisfaction Towards Royal Enfield BikesDocument72 pages"A Study Consumer Satisfaction Towards Royal Enfield BikesKotresh Kp100% (1)

- Pizza Hut Final!Document15 pagesPizza Hut Final!Alisha ParabNo ratings yet

- Ffective Riting Kills: Training & Discussion OnDocument37 pagesFfective Riting Kills: Training & Discussion OnKasi ReddyNo ratings yet

- Junguian PsychotherapyDocument194 pagesJunguian PsychotherapyRene Galvan Heim100% (13)

- DP-10/DP-10T/DP-11/DP-15/DP-18 Digital Ultrasonic Diagnostic Imaging SystemDocument213 pagesDP-10/DP-10T/DP-11/DP-15/DP-18 Digital Ultrasonic Diagnostic Imaging SystemDaniel JuarezNo ratings yet

- Slide Detail For SCADADocument20 pagesSlide Detail For SCADAhakimNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics L4 Consumer BehaviourDocument50 pagesManagerial Economics L4 Consumer BehaviourRifat al haque DhruboNo ratings yet

- 2011 Mena Annual Reportv1Document73 pages2011 Mena Annual Reportv1Yasmeen LayallieNo ratings yet

- Opera Arias and Sinfonias: VivaldiDocument22 pagesOpera Arias and Sinfonias: VivaldiDardo CocettaNo ratings yet

- Mazda 6 2014 - Automatic Transaxle Workshop Manual FW6A-EL PDFDocument405 pagesMazda 6 2014 - Automatic Transaxle Workshop Manual FW6A-EL PDFFelipe CalleNo ratings yet

- Accounting For Non Specialists Australian 7th Edition Atrill Test BankDocument26 pagesAccounting For Non Specialists Australian 7th Edition Atrill Test BankJessicaMitchelleokj100% (49)

- Exam Unit 1 Out and About 1º BachilleratoDocument5 pagesExam Unit 1 Out and About 1º Bachilleratolisikratis1980No ratings yet

- Sop For FatDocument6 pagesSop For Fatahmed ismailNo ratings yet

- Battle Bikes 2.4 PDFDocument56 pagesBattle Bikes 2.4 PDFfranzyland100% (1)

- Edited SCHOOL IN SERVICE TRAINING FOR TEACHERS MID YEAR 2023Document11 pagesEdited SCHOOL IN SERVICE TRAINING FOR TEACHERS MID YEAR 2023Lordennisa MacawileNo ratings yet

- (Jean Oliver and Alison Middleditch (Auth.) ) Funct (B-Ok - CC)Document332 pages(Jean Oliver and Alison Middleditch (Auth.) ) Funct (B-Ok - CC)Lorena BurdujocNo ratings yet

- IM PS Fashion-Business-Digital-Communication-And-Media 3Y Course Pathway MI 04Document7 pagesIM PS Fashion-Business-Digital-Communication-And-Media 3Y Course Pathway MI 04oliwia bujalskaNo ratings yet

- S-H Polarimeter Polartronic-532 Eng - 062015 PDFDocument2 pagesS-H Polarimeter Polartronic-532 Eng - 062015 PDFSuresh KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 Study QuestionsDocument3 pagesChapter 24 Study QuestionsAline de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Rotorvane Tea OrthodoxDocument9 pagesRotorvane Tea OrthodoxyurinaNo ratings yet

- LAWO PI - MADI - SRC - enDocument2 pagesLAWO PI - MADI - SRC - enfjavierpoloNo ratings yet