0% found this document useful (0 votes)

106 views6 pagesVertical Curve Design and Computation

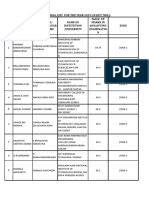

Vertical curves are parabolic curves used to connect intersecting gradients in the vertical plane at changes in gradient. They provide comfort for drivers by having a low rate of change of grade and allow safe stopping through adequate sight distances given design speeds. Simple parabolas are commonly used, with gradients expressed as percentages. Approximations can be used in computations by treating the curve as horizontal, with offsets proportional to the square of the distance. Design considers sight distances on crest curves and headlight visibility on sag curves. An example problem demonstrates computing offsets, gradients, and curve levels at intervals to check computations.

Uploaded by

Paulpablo ZaireCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

106 views6 pagesVertical Curve Design and Computation

Vertical curves are parabolic curves used to connect intersecting gradients in the vertical plane at changes in gradient. They provide comfort for drivers by having a low rate of change of grade and allow safe stopping through adequate sight distances given design speeds. Simple parabolas are commonly used, with gradients expressed as percentages. Approximations can be used in computations by treating the curve as horizontal, with offsets proportional to the square of the distance. Design considers sight distances on crest curves and headlight visibility on sag curves. An example problem demonstrates computing offsets, gradients, and curve levels at intervals to check computations.

Uploaded by

Paulpablo ZaireCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd