Professional Documents

Culture Documents

CA and BCR Abl Mut in Nilotinib Response PDF

Uploaded by

Ryan ViantinoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

CA and BCR Abl Mut in Nilotinib Response PDF

Uploaded by

Ryan ViantinoCopyright:

Available Formats

Original Articles

Impact of additional chromosomal aberrations and BCR-ABL kinase domain

mutations on the response to nilotinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive

chronic myeloid leukemia

Theo D. Kim1, Seval Türkmen2, Michaela Schwarz1, Gökben Koca1, Hendrik Nogai1, Christiane Bommer2,

Bernd Dörken1, Peter Daniel1, and Philipp le Coutre1

1

Klinik für Hämatologie und Onkologie and 2Institut für Medizinische Genetik, Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus

Virchow-Klinikum, Berlin, Germany

ABSTRACT

Acknowledgments: the authors

would like to thank

Background B. Pawlaczyk-Peter, P. Grille

Additional chromosomal aberrations in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid and K. Dietze for expert

leukemia are non-random and strongly associated with disease progression, but their prognos- technical assistance and

n

tic impact and effect on treatment response is not clear. Point mutations in the BCR-ABL kinase C. Haferlach for critical review

io

domain are probably the most common mechanisms of imatinib resistance. of the manuscript.

t

Design and Methods Manuscript received on

da

We assessed the influence of additional chromosomal aberrations and BCR-ABL kinase domain July 21, 2009. Revised

mutations on the response to the second-generation tyrosine kinase inhibitor nilotinib after version arrived on September 9,

un

imatinib-failure. Standard cytogenetic analysis of metaphases was performed to detect addi- 2009. Manuscript accepted

tional chromosomal aberrations and the BCR-ABL kinase domain was sequenced to detect on October 9, 2009.

point mutations.

Fo

Correspondence:

Results Theo D. Kim, Klinik für

Among 53 patients with a median follow-up of 16 months, of whom 38, 5 and 10 were in Hämatologie und Onkologie,

Charité - Universitätsmedizin

ti

chronic phase, accelerated phase and blast crisis, respectively, 19 (36%) had additional chromo-

Berlin, Campus Virchow-

or

somal aberrations and 20 (38%) had BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations. The 2-year overall Klinikum, Augustenburger Platz

survival rate of all patients without additional chromosomal aberrations (89%) was higher than 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany,

St

that of patients with such aberrations (54%) (P=0.0025). Among patients with chronic phase Phone: +49.30.450.553.077,

disease, overall survival at 2 years was 100% and 62% for patients without or with additional Fax: +49.30.450.553.964;

chromosomal aberrations, respectively (P=0.0024). BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations were E-mail: theo.kim@charite.de

ta

associated with lower remission rates in response to nilotinib, with 9 of 20 (45%) of these

patients achieving a major cytogenetic remission as compared to 26 of 33 (79%) patients with-

ra

out mutations (P<0.05). However, overall survival was not affected by BCR-ABL kinase domain

mutations.

r

Fe

Conclusions

Whereas BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations may confer more specific resistance to nilotinib,

©

which will predominantly affect response rates, the presence of additional chromosomal aber-

rations may reflect genetic instability and, therefore, intrinsic aggressiveness of the disease

which will be less amenable to subsequent alternative treatments and thus negatively affect

overall survival. Conventional cytogenetic analyses remain mandatory during follow-up of

patients with chronic myeloid leukemia under tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy.

Key words: chronic myeloid leukemia, nilotinib, additionl chromosomal aberrations.

Citation: Kim TD, Türkmen S, Schwarz M, Koca G, Nogai H, Bommer C, Dörken B, Daniel P,

and le Coutre P. Impact of additional chromosomal aberrations and BCR-ABL kinase domain muta-

tions on the response to nilotinib in Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic myeloid leukemia.

Haematologica. 2010;95:582-588. doi:10.3324/haematol.2009.014712.

©2010 Ferrata Storti Foundation. This is an open-access paper.

582 haematologica | 2010; 95(4)

Additional chromosomal aberrations and nilotinib

Introduction clinical trials (registered at Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00109707 and

NCT00905593). Both trials were conducted in accordance with

In chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) the pathogenic role the applicable regulatory requirements. Patients gave their written

of the oncogenic BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase, which results informed consent to participate in a clinical trial or to have their

from a reciprocal translocation between chromosomes 9 data analyzed retrospectively. All procedures were performed in

and 22 to form the Philadelphia chromosome (Ph), accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the

sparked the development of the orally active small mole- local ethics committee. Patients received nilotinib 400 mg twice

cule kinase inhibitor, imatinib.1 Unprecedented clinical daily with dose reductions, as necessary, in the case of toxicity.

activity established imatinib as standard first-line therapy Patients were followed regularly at intervals of 3 to 6 months.

for Ph-positive CML and as a successful paradigm for tar- Follow-up included clinical assessment and bone marrow evalua-

geted therapy. However, more than 30% of patients with tion with metaphase cytogenetics and determination of BCR-ABL

newly diagnosed chronic phase CML discontinued ima- transcript levels in bone marrow or peripheral blood samples by

tinib within 6 years2 and acquired resistance after initial quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. Disease

response develops in a substantial proportion of patients. stage and response were determined according to standard crite-

Various mechanisms have been described to cause resist- ria.5,9

ance, but point mutations within the kinase domain of

BCR-ABL are probably the clinically most relevant and

best characterized.3,4 Several types of mutations, causing Karyotype analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization

varying degrees of resistance in vitro and in vivo, have been Cytogenetic analysis of metaphases and fluorescence in situ

described.4 hybridization (FISH) of bone marrow samples were performed

n

Nilotinib is a second-generation tyrosine kinase according to standard protocols. Results are reported using the

io

inhibitor that was designed to be both more specific and International System for Human Cytogenetic Nomenclature.

more potent than imatinib in inhibiting the wild-type ABL Cytogenetic responses, based on the analysis of at least 20

t

da

tyrosine kinase, as well as most kinase domain mutations metaphases, were defined as complete (no Ph-positive metaphas-

conferring resistance to imatinib.5,6 Given its significant es), partial (1-35% Ph-positive metaphases), minor (36-65% Ph-

clinical activity in imatinib-resistant or -intolerant patients positive metaphases) or minimal (66-95% Ph-positive metaphas-

with Ph-positive CML, nilotinib has been approved as a

second-line agent in chronic and accelerated phases of this un

es). Major cytogenetic responses included complete and partial

cytogenetic responses.

Fo

disease.7-9 Resistance to nilotinib due to BCR-ABL kinase

domain mutations has been predicted from in vitro BCR-ABL sequencing

screens,10-13 but clinical evidence on the relevance of these In order to detect mutations in the kinase domain of BCR-ABL,

mutations is still incomplete. RNA from either bone marrow or peripheral blood samples was

ti

The occurrence of additional chromosomal aberrations reverse transcribed and amplified by nested PCR using previously

or

(ACA) in Ph-positive CML is strongly associated with dis- published primers to generate an amplicon covering the entire

ease progression and has been interpreted as both a sign of BCR-ABL kinase domain.22 Sequencing was performed on an ABI

St

clonal evolution and chromosomal instability.14 These PRISM 310 Genetic Analyzer 310 (Applied Biosystems, Foster

abnormalities are non-random, with the most common City, CA, USA). At least one sample was sequenced for each

being +8, +Ph, i(17q), +19, -Y, +21, +17, and -7, which

ta

patient: (i) preferentially before the start of nilotinib treatment,

have, therefore, been dubbed major route abnormalities. and (ii) in each case of disease progression or loss of response.

ra

Although their clinical impact is variable,14 in the pre-ima-

tinib era abnormalities involving chromosome 17 seemed Statistical analysis

r

to be associated with an inferior prognosis.15 Several stud- Descriptive statistical analyses were performed using the χ2-test

Fe

ies have assessed the impact of ACA on the clinical effica- or the Mann-Whitney-test when appropriate. Kaplan-Meier

cy of imatinib under the assumption that these abnormal- curves were constructed for overall survival and progression-free

ities may confer BCR-ABL-independent proliferation and survival. Differences were analyzed with the log-rank test. Overall

©

decrease sensitivity to imatinib.16-21 Results have been vari- survival was calculated from the start of nilotinib therapy to death.

able, with evidence for an impact on the duration of Progression-free survival was calculated from the time of the first

remission,17 survival,16 risk of hematologic relapse,18 and major cytogenetic response to loss of this response, disease pro-

response.21 However, clonal evolution did not necessarily gression to accelerated phase or blast crisis, discontinuation of

impair prognosis when considered as the sole criterion for nilotinib because of resistant disease, or death, whichever

acceleration of disease19 or within separate disease occurred first. Patients were censored at the last follow-up. A P-

stages.20 value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All

Given the clinical importance of predicting resistance to tests were two-sided.

nilotinib we investigated the influence of ACA and BCR-

ABL mutations on the clinical efficacy of nilotinib in

patients with Ph-positive CML. Results

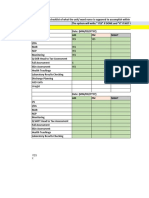

Patients’ characteristics

Design and Methods In total, 53 patients (median age, 63 years; range, 36 -

85) with a median follow-up of 16 months (range, 1 - 50)

Patients and samples were analyzed (Table 1). Of these, 38, 5 and 10 patients

Between September 2004 and February 2009, 53 patients with were in chronic phase, accelerated phase and blast crisis,

Ph-positive CML and imatinib-resistance or -intolerance were respectively. The median duration of previous treatment

treated with nilotinib in our center and are analyzed in this study. with imatinib was 33 months (range, 1 - 107). Prior to ima-

Most patients (>90 %) received nilotinib as part of still ongoing tinib 45 of 53 (85%) had received hydroxyurea and 22 of

haematologica | 2010; 95(4) 583

T.D. Kim et al.

53 (42%) interferon. The median duration of nilotinib somal aberrations in Ph-negative clones at baseline. One

therapy was 14 months (range, 1 - 50). Thirty-five of the patient with +8 is in complete molecular remission at the

53 patients (66%) had a major cytogenetic response. last follow-up and one patient with two different clones,

Twenty-two of the 53 patients (42%) discontinued nilo- with +12, -18, +mar and +1, -5, +12, died after 17 months.

tinib treatment, mostly (16 of 22, 73%) because of clinical

resistance, e.g. loss of response or disease progression. Of Frequency and spectrum of BCR-ABL kinase domain

these 22 patients, 11 were either in accelerated phase mutations prior to and during nilotinib therapy

(n=3) or blast crisis (n=8) at baseline. Nine patients Overall, sequencing identified BCR-ABL kinase domain

received treatment after nilotinib including dasatinib mutations in 20 of 53 patients (38%, Tables 3 and 4). Most

(n=6), INNO-406 (n=4), homoharringtonin (n=1), conven- of these patients (14 of 20, 70%) had a single mutation.

tional chemotherapy (n=3) and/or hematopoetic stem cell However, five patients presented with two different

transplantation (n=2). mutations (either in a single clone or in two different

clones) and one patient had three mutations. Nine of 38

Identification of additional cytogenetic aberrations patients (26%) who were assessed at baseline had muta-

prior to nilotinib therapy tions prior to nilotinib therapy. Of these, four had com-

Cytogenetic analysis on bone marrow metaphases iden- pletely different mutations at later time points with loss of

tified ACA in 19 patients (36%), with 44 single abnormal- the mutation present at baseline mutation, three acquired

ities detected. About half of the ACA (21 of 44, 48%) con- mutations in addition to the baseline mutation, one

sisted of the previously described major route aberra- patient (with H396R) lost his mutation and one patient

tions,14 including +8, +Ph, i(17q), +19, -Y, +21, +17, and -7 (with E255K) had the same mutation at the end of nilo-

n

(Table 2). Five of the 44 abnormalities involved chromo- tinib therapy. Six of 53 patients (11%) had more than one

io

some 17. The occurrence of ACA was significantly associ-

ated with disease stage and was detected in 24%, 80%

t

da

and 60% of the patients in chronic phase, accelerated

phase and blast crisis, respectively (Table 1). There were Table 2. Additional chromosomal aberrations detected after imatinib

and before nilotinib treatment.

no significant differences with respect to age, disease

duration or duration of imatinib therapy between patients

with or without ACA. During therapy with nilotinib three

N.

6 un Aberration

+Ph

Route

Major

Fo

patients developed new ACA. After 3 months, one patient 6 +8 Major

in blast crisis with +Ph at baseline developed del(7)(q21),

3 i(17q) Major

followed by an additional del(6)(q2?1) 1 month later. Of

two other patients in chronic phase without ACA at base- 3 +14

ti

line, one developed der(17)t(17;?)(p13;?)del(17)(p13)t(17;?) 2 -Y Major

or

(q25;?) with progression to blast crisis after 6 months and 2 +21 Major

the other +Ph after 7 months. Two patients had chromo-

St

2 +19 Major

1 each +X, +1, +2, +6, +11, 15, +der(2), -21,

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with or without additional chromo- add(17)(q10), ider(22)(q10)t(9;22)(q34;q11),

ta

somal aberrations (ACA). +C, +mar, t(8;17)(q13;q23), -13, del(2)(p11),

del(3)(p13p21), del(7)(p11p15), del(7)(q22),

ra

Ph+ ACA Ph p del(9)(p11p22), der(9)t(9;22)(q34;q11)inv(9)

N. 19 34 (p13q34)

r

Fe

Male/Female 12/7 11/23

Median age (years, range) 63 (41-85) 62 (36-84) NS

Stage

©

Chronic phase (%) 9 (47) 29 (85) Table 3. Relative frequency of BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations

Accelerated phase (%) 4 (21) 1 (3) 0.0109 detected before and after treatment with nilotinib.

Blast crisis (%) 6 (32) 4 (12) Before Nilotinib After Nilotinib

myeloid/lymphoid 5/1 2/1* N. Mutation Sensitivity N. Mutation Sensitivity

Previous treatment 2 E255K resistant 4 Y253H resistant

Hydroxyurea (%) 17 (89) 28 (82) NS

Busulfan (%) 0 (0) 2 (6) 1 G250E sensitive 4 F359I unknown

Interferon (%) 7 (37) 15 (44) 1 Q252H sensitive 3 G250E sensitive

Other (%) 2 (11) 10 (29) 1 F311Y unknown 3 E255K resistant

Stem cell transplantation (%) 2 (11) 0 (0)

1 T315I resistant 3 T315I resistant

Follow-up (months, range) 15 (5-40) 23.5 (1-50) NS

1 M351T sensitive 2 M351T sensitive

Median disease duration 75 (3-156) 67.5 (3-180) NS

1 L387M unknown 1 Y253F unknown

(months, range)

1 H396R unknown 1 E255V resistant

Median duration on imatinib 22 (2-61) 36.5 (1-107) NS

(months, range) 1 A397P unknown 1 D276G sensitive

Median duration on nilotinib 11 (1-40) 14.5 (1-50) NS 1 E292V unknown

(months, range) 1 F317L sensitive

Ph: Philadelphia chromosome-positive; NA: not applicable; NS: not significant; *one

1 F359V resistant

patient in blast crisis was not assessable. Categories are based on an IC50 cut-off value of 150 nM.23

584 haematologica | 2010; 95(4)

Additional chromosomal aberrations and nilotinib

mutation at baseline or during follow-up with the follow- Table 4. Response to nilotinib and spectrum of BCR-ABL kinase

ing genotypes: M351T/D276G/F359I, Y253H/F359V, domain mutations in patients with or without additional chromosomal

Y253F/E255K, G250E/T315I (twice), G250E/F359I, aberrations.

G250E/M351T. One patient had two different combina- Ph + ACA Ph P

tions at baseline and during follow-up. BCR-ABL point Best response

mutations tended to occur more often in patients with NEL or worse (%) 7 (37) 5 (15) NS

ACA (53%) than in patients without ACA (29%). Overall, Complete hematologic response (%) 1 (5) 5 (15)

ten patients had ACA with mutations, nine patients had Major cytogenetic response (%) 1 (5) 5 (15)

ACA without mutations, ten patients had mutations with- Complete cytogenetic response (%) 8 (43) 8 (23)

out ACA, and 24 patients had neither ACA nor mutations. Major molecular response (%) 1 (5) 2 (6)

Mutations predicted to confer resistance to nilotinib with Complete molecular response (%) 1 (5) 9 (26)

an IC50 of greater than 150 nM23 (Y253H, E255K/V, T315I Response Kinetics

and F359V) were found in 15 cases. Six had sensitive MCyR at 3 months (%) 8/11 (73) 19/24 (79) NS

mutations (IC50 <150 nM) and ten cases had mutations MCyR at 6 months (%) 9/11 (82) 21/24 (88) NS

with unknown sensitivity to nilotinib (Table 4). CCyR at 3 months (%) 5/10 (50) 11/18 (61) NS

CCyR at 6 months (%) 8/10 (80) 14/18 (78) NS

Clinical response to nilotinib in patients with additional Discontinuation of nilotinib (%) 10 (53) 12 (35) NS

chromosome aberrations and BCR-ABL point mutations Resistance 9 7 0.0417

Overall, the rate of major cytogenetic response in chron- Intolerance 0 4 NS

ic phase was 74%, and the rate of any response in acceler- Other* 1 1 NS

n

ated phase or blast crisis was 73%. There was no statisti- Deaths (%) 9 (47) 3 (9) 0.0269

io

cally significant difference with respect to response Death from disease progression (%) 7 (37) 3 (9) 0.0124

between patients with and without ACA (Table 4).

t

Disease-unrelated death (%) 2 (11) 0 (0) NS

da

However, more patients with ACA discontinued nilotinib New cytogenetic aberrations

(53% versus 35%), mostly due to resistant disease (47% New chromosomal aberrations (%) 1 (5) 1 (3) NS

versus 21%, P<0.05). Three of the five patients with abnor- Chromosomal aberrations in Ph-

malities of chromosome 17 had resistant disease (60%).

Patients with ACA more frequently tended to have BCR- unnegative metaphases (%)

BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations

0 (0) 2 (6) NS

Fo

ABL mutations (53% versus 29%) and more resistant Patients with mutations (%) 10 (53) 10 (29) NS

mutations (60% versus 38%, Table 4). Patients with muta- Resistant (%) 9 (60) 6 (38) NS

tions were less likely to respond to nilotinib, with 9 of 20 Sensitive (%) 2 (13) 4 (25)

(45%) having a major cytogenetic response as compared

ti

Unknown (%) 4 (27) 6 (38)

to 26 of 33 (79%) patients without kinase domain muta-

or

NEL: no evidence of leukemia; MCyR: major cytogenetic response; CCyR: complete cyto-

tions (P<0.05). None of four patients with T315I had a genetic response; MMolR: major molecular response; NS: not significant. *Other: 1 seri-

ous adverse event (mucositis and fever), 1 withdrawal of consent.

cytogenetic response. In terms of response kinetics, there

St

ta

ra

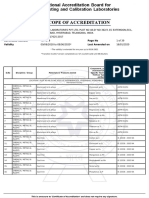

A All patients C ACA and BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations

r

Fe

100 Ph 100 Ph P=0.029

Percent survival

Percent survival

Ph+ ACA Ph+ ACA

75 P=0.0025 75 Ph + Mutations

P=0.0136

©

Ph + ACA + Mutations

50 50

25 25

0 0

0 12 24 36 48 0 12 24 36 48

Months Months

Numbers at risk Numbers at risk

Ph 34 26 17 11 Ph 24 17 9 8

Ph + ACA 19 12 7 5 Ph + ACA 9 7 5 3

Ph + Mutations 10 10 8 4

Ph + ACA + Mutations 10 6 4 3

B Patients in CP

100 Ph

Percent survival

Ph+ ACA

75

P=0.0024

50

25 Figure 1. The presence of additional chromosomal aberrations

0 (ACA) negatively affects overall survival. (A) Overall survival of

0 12 24 36 48 the entire population. (B) Overall survival for patients in chronic

Months phase (CP) only. (C) Overall survival of the entire population strat-

Numbers at risk ified for the presence of ACA and BCR-ABL kinase domain muta-

Ph 28 23 15 9 tions.

Ph + ACA 9 8 5 3

haematologica | 2010; 95(4) 585

T.D. Kim et al.

was no difference between patients with our without associated with decreased overall survival which may be

ACA (Table 4) or patients with or without BCR-ABL attributable to the relatively long disease duration of our

kinase domain mutations (data not shown). chronic phase study cohort. The presence of ACA had no

impact on overall survival among patients in accelerated

Additional chromosomal aberrations negatively affect phase or blast crisis (data not shown), perhaps due to the

overall survival independently of BCR-ABL kinase low number of patients in these groups or a true lesser

domain mutations biological importance. The progression-free survival rate

The overall survival and progression-free survival of the was lower among patients with ACA, but the difference

whole cohort at 2 years was 76% and 58%, respectively. was not statistically significant. One possible explanation

Patients with ACA had significantly worse overall survival for this is the higher number of patients in the ACA group

(54%) than patients without ACA (89%, P=0.0025, Figure who had died without having any response. It is unknown

1A). The progression-free survival rates at 2 years were when ACA occurred during imatinib therapy. Indeed, the

37% and 69%, respectively (P=NS). Since the presence of duration of ACA could be an important factor. However,

ACA was significantly associated with disease stage, we at present there is no evidence to favor a clinical decision,

assessed the influence of ACA for each disease stage. such as switching treatment or increasing the dose of ima-

Overall survival at 2 years among patients in chronic tinib, based on the detection of ACA.

phase was 62% and 100% for patients with or without ACA were identified in 36% of patients, of which about

ACA, respectively (P=0.0024) (Figure 1B). In multivariate half were so-called major route aberrations that are found

analysis, only stage was significantly associated with sur- in more than 5% of cases with ACA.14 Several patterns of

vival, while ACA was not statistically significant (P=0.09, karyotypic evolution have been correlated with previous

n

data not shown). Survival was not different for patients treatment. Although limited by the comparatively small

io

with accelerated phase or blast crisis (data not shown). number of patients and the heterogeneous treatment

Three patients with ACA (16%) and six patients without before imatinib, there was no increase of unusual aberra-

t

da

ACA (18%) received treatment after nilotinib. Both tions with the possible exception of trisomy 14 which

patients who underwent hematopoietic stem cell trans- appeared slightly more common than described in the lit-

plantation had ACA. One died of disease progression, and erature. Abnormalities involving chromosome 17 or a

one is in complete molecular remission 18 months after

transplantation. Abnormalities involving chromosome 17 un

duplication of the Philadelphia chromosome were found

in five and six cases, respectively, but did not seem to con-

Fo

and duplication of the Philadelphia chromosome did not fer a worse prognosis. Chromosomal aberrations in Ph-

affect survival. The presence of BCR-ABL kinase domain negative clones have previously been observed after treat-

mutations did not affect survival when analyzed inde- ment with imatinib,26 dasatinib,27 and nilotinib28 with

pendently or in the context of ACA (Figure 1C). However, undetermined significance.

ti

when stratified for presumed sensitivity to nilotinib, there Several mechanisms of resistance to imatinib have been

or

was a trend towards an elevated survival with higher sen- described. However, mutations within the kinase domain

sitivity to nilotinib (data not shown). of BCR-ABL are probably the clinically most important.4

St

Although nilotinib has been described to be effective

against most mutations conferring resistance to imatinib,23

Discussion screening assays were performed to analyze potential

ta

resistance mechanisms against this second-generation

ra

In patients with Ph-positive CML the prediction of tyrosine kinase inhibitor.10,11,13 Several nilotinib-resistant

resistance to targeted therapy with tyrosine kinase mutations that are only partly overlapping with imatinib

r

inhibitors may help timely identification of those who and dasatinib were identified with the T315I mutation

Fe

would benefit from alternative therapies. Based on clinical being completely resistant to all currently approved tyro-

response to imatinib, criteria have been established to sine kinase inhibitors. In vitro and in vivo, there is evidence

define failure or suboptimal response in early chronic that the Y253H, E255K/V and F359C/V mutations are rel-

©

phase CML.24 Achievement of a cytogenetic response at 3- atively resistant to nilotinib23,29-32 and may negatively affect

6 months under treatment with a second generation tyro- the response to nilotinib.33 Alternative mechanisms of

sine kinase inhibitor was highly predictive for a major resistance to nilotinib include the relative insensitivity of

cytogenetic response at 12 months and was associated CML progenitors,34,35 survival factors,36,37 src kinase overex-

with increased progression-free and overall survival.25 pression,38 and the protective bone marrow environment.39

However, these criteria are time-dependent and require BCR-ABL kinase domain mutations were frequent in

observation for several months. our population, which is in agreement with previous

In our series of patients receiving nilotinib after imatinib results8 and the generally advanced stage after imatinib-

had failed, we found that the presence of ACA prior to failure. Patients with mutations had significantly less

nilotinib treatment predicted worse overall survival. response to nilotinib than patients with wild-type BCR-

Clinical results with imatinib have been conflicting with ABL, but this did not translate into worse overall survival.

variable impact on the duration of remission, survival, risk In addition, the presence of BCR-ABL kinase domain

of hematologic relapse or response.16-21 One reason for the mutations did not enable further stratification of patients

differences between these studies and our findings may be with ACA. The correlation of single point mutations with

that our study population included patients in whom ima- clinical outcome is confounded by various issues.

tinib had failed and who, therefore, had advanced disease, Heterogeneous definitions of resistance, e.g. cut-off values

in which differences may become more apparent. The for IC50, the assays that these IC50 values are based upon,

correlation of ACA with advanced disease stage may have and the lack of information for a number of mutations

contributed to the worse outcome of patients with ACA. must all be taken into account. In addition, correlating the

But even among patients in chronic phase, ACA were IC50 with Cmax and/or Cmin as in vivo parameters may better

586 haematologica | 2010; 95(4)

Additional chromosomal aberrations and nilotinib

reflect the physiological significance of individual muta- are evidence for a generally more aggressive disease that

tions. Here, defining resistance with an IC50 cut-off of 150 may or may not have additional mutations. Obviously,

nM, we found evidence for selection of resistant muta- patients in whom nilotinib had failed received subsequent

tions with nilotinib in vivo. Overall, there were more muta- treatment with alternative substances with different

tions after nilotinib therapy than before, with a relative resistance profiles, which could circumvent resistance to

increase of resistant mutations. Most (7 of 8) patients with nilotinib but would address the intrinsic aggressiveness of

wild-type BCR-ABL at baseline and a point mutation dur- the disease to a lesser degree.

ing nilotinib therapy had a resistant mutation, e.g. Y253H, In conclusion, ACA were frequently detected and were

E255K/V or T315I. A recent analysis did not find a worse significantly associated with worse overall survival in

outcome for patients with T315I after failure of treatment patients with Ph-positive CML after imatinib treatment

with imatinib or a second generation tyrosine kinase had failed. This indicates that conventional cytogenetics

inhibitor.40 However, none of four patients with T315I had on metaphases remains mandatory at diagnosis and dur-

a cytogenetic response and three had completely resistant ing follow-up and should not be replaced by techniques

disease and died in blast crisis. One patient retrospective- that analyze only BCR-ABL. The decreased efficacy of

ly found to harbor T315I and G250E had lost T315I, while nilotinib in the context of ACA may reflect intrinsic

additionally acquiring F359I more than 3 years later, indi- aggressiveness of the disease that should, therefore, be

cating that T315I is not invariably selected during progres- monitored more closely. Point mutations of the BCR-ABL

sion.22 The timing of screening for BCR-ABL kinase kinase domain were common and associated with resist-

domain mutations triggered by rising transcript levels has ant disease. However, differential sensitivities to nilotinib

been addressed in several reports.41-43 However, there are and varying clinical courses with the same mutation ham-

n

currently no consensus guidelines similar to those for per clinical decision-making based solely on mutational

io

defining failure and suboptimal response in early chronic analysis, with the notable exception of T315I.

phase.24 A practical approach to monitoring patients with

t

da

CML has recently been proposed.44

Despite the relatively small sample size and retrospec- Authorship and Disclosures

tive nature of this single center analysis, the presence of

ACA significantly affected overall survival and to a lesser

degree response to nilotinib. However, BCR-ABL kinase un TDK and PlC wrote the paper and analyzed data; ST

and CB performed the cytogenetic analysis; PD performed

Fo

domain mutations conferred resistance to nilotinib, as evi- the sequencing; MS, GK, HN and BD analyzed data; all

denced by fewer cytogenetic remissions, but did not affect authors approved the paper.

survival. One possible explanation for this apparent dis- PlC received honoraria from Novartis. No other poten-

crepancy is a direct and rather specific resistance to nilo- tial conflicts of interests relevant to this article were

ti

tinib through BCR-ABL point mutations, whereas ACA reported.

or

St

References Nilotinib (formerly AMN107), a highly Sanger J, Peschel C, Duyster J. Bcr-Abl

ta

selective BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase resistance screening predicts a limited spec-

inhibitor, is effective in patients with trum of point mutations to be associated

ra

1. Druker BJ. Translation of the Philadelphia Philadelphia chromosome-positive chronic with clinical resistance to the Abl kinase

chromosome into therapy for CML. Blood. myelogenous leukemia in chronic phase inhibitor nilotinib (AMN107). Blood. 2006;

2008;112(13):4808-17. following imatinib resistance and intoler- 108(4):1328-33.

r

2. Hochhaus A, O'Brien SG, Guilhot F, Druker ance. Blood. 2007;110(10):3540-6. 14. Johansson B, Fioretos T, Mitelman F.

Fe

BJ, Branford S, Foroni L, et al. Six-year fol- 9. le Coutre P, Ottmann OG, Giles F, Kim DW, Cytogenetic and molecular genetic evolu-

low-up of patients receiving imatinib for Cortes J, Gattermann N, et al. Nilotinib tion of chronic myeloid leukemia. Acta

the first-line treatment of chronic myeloid (formerly AMN107), a highly selective Haematol. 2002;107(2):76-94.

©

leukemia. Leukemia. 2009;23(6):1054-61. BCR-ABL tyrosine kinase inhibitor, is 15. Majlis A, Smith TL, Talpaz M, O'Brien S,

3. Apperley JF. Part I: mechanisms of resist- active in patients with imatinib-resistant or Rios MB, Kantarjian HM. Significance of

ance to imatinib in chronic myeloid -intolerant accelerated-phase chronic myel- cytogenetic clonal evolution in chronic

leukaemia. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8(11):1018- ogenous leukemia. Blood. 2008;111(4): myelogenous leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 1996;

29. 1834-9. 14(1):196-203.

4. O'Hare T, Eide CA, Deininger MW. Bcr-Abl 10. Bradeen HA, Eide CA, O'Hare T, Johnson 16. Cortes JE, Talpaz M, Giles F, O'Brien S, Rios

kinase domain mutations, drug resistance, KJ, Willis SG, Lee FY, et al. Comparison of MB, Shan J, et al. Prognostic significance of

and the road to a cure for chronic myeloid imatinib mesylate, dasatinib (BMS- cytogenetic clonal evolution in patients

leukemia. Blood. 2007;110(7):2242-9. 354825), and nilotinib (AMN107) in an N- with chronic myelogenous leukemia on

5. Kim TD, Dörken B, le Coutre P. Nilotinib ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)-based mutagen- imatinib mesylate therapy. Blood. 2003;

for the treatment of chronic myeloid esis screen: high efficacy of drug combina- 101(10):3794-800.

leukemia. Expert Rev Hematol. 2008;1(1): tions. Blood. 2006;108(7):2332-8. 17. Mohamed AN, Pemberton P, Zonder J,

29-39. 11. Ray A, Cowan-Jacob SW, Manley PW, Schiffer CA. The effect of imatinib mesy-

6. Weisberg E, Manley PW, Breitenstein W, Mestan J, Griffin JD. Identification of BCR- late on patients with Philadelphia chromo-

Bruggen J, Cowan-Jacob SW, Ray A, et al. ABL point mutations conferring resistance some-positive chronic myeloid leukemia

Characterization of AMN107, a selective to the Abl kinase inhibitor AMN107 (nilo- with secondary chromosomal aberrations.

inhibitor of native and mutant Bcr-Abl. tinib) by a random mutagenesis study. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(4):1333-7.

Cancer Cell. 2005;7(2):129-41. Blood. 2007;109(11):5011-5. 18. O'Dwyer ME, Mauro MJ, Blasdel C,

7. Kantarjian H, Giles F, Wunderle L, Bhalla K, 12. Redaelli S, Piazza R, Rostagno R, Farnsworth M, Kurilik G, Hsieh YC, et al.

O'Brien S, Wassmann B, et al. Nilotinib in Magistroni V, Perini P, Marega M, et al. Clonal evolution and lack of cytogenetic

imatinib-resistant CML and Philadelphia Activity of bosutinib, dasatinib, and nilo- response are adverse prognostic factors for

chromosome-positive ALL. N Engl J Med. tinib against 18 imatinib-resistant hematologic relapse of chronic phase CML

2006;354(24):2542-51. BCR/ABL mutants. J Clin Oncol. 2009; patients treated with imatinib mesylate.

8. Kantarjian HM, Giles F, Gattermann N, 27(3):469-71. Blood. 2004;103(2):451-5.

Bhalla K, Alimena G, Palandri F, et al. 13. von Bubnoff N, Manley PW, Mestan J, 19. O'Dwyer ME, Mauro MJ, Kurilik G, Mori

haematologica | 2010; 95(4) 587

T.D. Kim et al.

M, Balleisen S, Olson S, et al. The impact of Stacchini M, Gamberini C, Castagnetti F, et pression in CML progenitors. Leukemia.

clonal evolution on response to imatinib al. Emergence of clonal chromosomal 2008;22(4):748-55.

mesylate (STI571) in accelerated phase abnormalities in Philadelphia negative 36. Belloc F, Airiau K, Jeanneteau M, Garcia M,

CML. Blood. 2002;100(5):1628-33. hematopoiesis in chronic myeloid Guerin E, Lippert E, et al. The stem cell fac-

20. Schoch C, Haferlach T, Kern W, Schnittger leukemia patients treated with nilotinib tor-c-KIT pathway must be inhibited to

S, Berger U, Hehlmann R, et al. Occurrence after failure of imatinib therapy. Leuk Res. enable apoptosis induced by BCR-ABL

of additional chromosome aberrations in 2009;33(12):e218-20. inhibitors in chronic myelogenous

chronic myeloid leukemia patients treated 29. Cortes J, Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Yin CC, leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2009;23(4):679-

with imatinib mesylate. Leukemia. 2003; Shan J, O'Brien S, et al. Dynamics of BCR- 85.

17(2):461-3. ABL kinase domain mutations in chronic 37. Wang Y, Cai D, Brendel C, Barett C, Erben

21. Palandri F, Testoni N, Luatti S, Marzocchi myeloid leukemia after sequential treat- P, Manley PW, et al. Adaptive secretion of

G, Baldazzi C, Stacchini M, et al. Influence ment with multiple tyrosine kinase granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulat-

of additional cytogenetic abnormalities on inhibitors. Blood. 2007;110(12):4005-11. ing factor (GM-CSF) mediates imatinib and

the response and survival in late chronic 30. Hochhaus A, Erben P, Branford S, Radich J, nilotinib resistance in BCR/ABL+ progeni-

phase chronic myeloid leukemia patients Kim DW, Martinelli G, et al. Hematologic tors via JAK-2/STAT-5 pathway activation.

treated with imatinib: long-term results. and cytogenetic response dynamics to nilo- Blood. 2007;109(5):2147-55.

Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50(1):114-8. tinib (AMN107) depend on the type of 38. Mahon FX, Hayette S, Lagarde V, Belloc F,

22. Willis SG, Lange T, Demehri S, Otto S, BCR-ABL mutations in patients with Turcq B, Nicolini F, et al. Evidence that

Crossman L, Niederwieser D, et al. High- chronic myelogeneous leukemia (CML) resistance to nilotinib may be due to BCR-

sensitivity detection of BCR-ABL kinase after imatinib failure. ASH Annual Meeting ABL, Pgp, or Src kinase overexpression.

domain mutations in imatinib-naive Abstracts. 2006 November 16, 2006; Cancer Res. 2008;68(23):9809-16.

patients: correlation with clonal cytogenet- 108(11):749. 39. Dillmann F, Veldwijk MR, Laufs S,

ic evolution but not response to therapy. 31. Hughes T, Saglio G, Martinelli G, Kim D- Sperandio M, Calandra G, Wenz F, et al.

Blood. 2005;106(6):2128-37. W, Soverini S, Mueller M, et al. Responses Plerixafor inhibits chemotaxis toward SDF-

23. Weisberg E, Manley P, Mestan J, Cowan- and disease progression in CML-CP 1 and CXCR4-mediated stroma contact in a

n

Jacob S, Ray A, Griffin JD. AMN107 (nilo- patients treated with nilotinib after ima- dose-dependent manner resulting in

tinib): a novel and selective inhibitor of tinib failure appear to be affected by the increased susceptibility of BCR-ABL(+) cell

io

BCR-ABL. Br J Cancer. 2006;94(12): 1765-9. BCR-ABL mutation status and types. ASH to imatinib and nilotinib. Leuk Lymphoma.

24. Baccarani M, Saglio G, Goldman J, Annual Meeting Abstracts. 2007 November 2009;50(10):1676-86.

t

Hochhaus A, Simonsson B, Appelbaum F, 16, 2007;110(11):320. 40. Jabbour E, Kantarjian H, Jones D, Breeden

da

et al. Evolving concepts in the management 32. Soverini S, Gnani A, Colarossi S, M, Garcia-Manero G, O'Brien S, et al.

of chronic myeloid leukemia: recommen- Castagnetti F, Palandri F, Giannoulia P, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients

dations from an expert panel on behalf of Philadelphia chromosome-positive with chronic myeloid leukemia and T315I

25.

the European LeukemiaNet. Blood. 2006;

108(6):1809-20.

Tam CS, Kantarjian H, Garcia-Manero G, un

leukemia patients who harbor imatinib-

resistant mutations have a higher likeli-

hood of developing additional mutations 41.

mutation following failure of imatinib

mesylate therapy. Blood. 2008;112(1):53-5.

Branford S, Rudzki Z, Parkinson I, Grigg A,

Fo

Borthakur G, O'Brien S, Ravandi F, et al. associated with resistance to novel tyrosine Taylor K, Seymour JF, et al. Real-time quan-

Failure to achieve a major cytogenetic kinase inhibitors. ASH Annual Meeting titative PCR analysis can be used as a pri-

response by 12 months defines inadequate Abstracts. 2007 November 16, mary screen to identify patients with CML

response in patients receiving nilotinib or 2007;110(11):322. treated with imatinib who have BCR-ABL

ti

dasatinib as second or subsequent line ther- 33. Hughes T, Saglio G, Branford S, Soverini S, kinase domain mutations. Blood. 2004;

or

apy for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. Kim DW, Muller MC, et al. Impact of base- 104(9):2926-32.

2008;112(3):516-8. line BCR-ABL mutations on response to 42. Press RD, Willis SG, Laudadio J, Mauro MJ,

26. Bumm T, Muller C, Al-Ali HK, Krohn K, nilotinib in patients with chronic myeloid Deininger MW. Determining the rise in

St

Shepherd P, Schmidt E, et al. Emergence of leukemia in chronic phase. J Clin Oncol. BCR-ABL RNA that optimally predicts a

clonal cytogenetic abnormalities in Ph- cells 2009;27(25):4204-10. kinase domain mutation in patients with

in some CML patients in cytogenetic remis- 34. Jorgensen HG, Allan EK, Jordanides NE, chronic myeloid leukemia on imatinib.

ta

sion to imatinib but restoration of poly- Mountford JC, Holyoake TL. Nilotinib Blood. 2009;114(13):2598-605.

clonal hematopoiesis in the majority. exerts equipotent antiproliferative effects 43. Wang L, Knight K, Lucas C, Clark RE. The

Blood. 2003;101(5):1941-9. to imatinib and does not induce apoptosis role of serial BCR-ABL transcript monitor-

ra

27. De Melo VA, Milojkovic D, Khorashad JS, in CD34+ CML cells. Blood. 2007;109(9): ing in predicting the emergence of BCR-

Marin D, Goldman JM, Apperley JF, et al. 4016-9. ABL kinase mutations in imatinib-treated

r

Philadelphia-negative clonal hematopoiesis 35. Konig H, Holtz M, Modi H, Manley P, patients with chronic myeloid leukemia.

Fe

is a significant feature of dasatinib therapy Holyoake TL, Forman SJ, et al. Enhanced Haematologica. 2006;91(2):235-9.

for chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood. BCR-ABL kinase inhibition does not result 44. Radich JP. How I monitor residual disease

2007;110(8):3086-7. in increased inhibition of downstream sig- in chronic myeloid leukemia. Blood.

2009;114(16):3376-81.

©

28. Baldazzi C, Luatti S, Marzocchi G, naling pathways or increased growth sup-

588 haematologica | 2010; 95(4)

You might also like

- Gastrulation in BirdsDocument20 pagesGastrulation in Birdskashif manzoor75% (4)

- Going Concern ChecklistDocument1 pageGoing Concern Checklisttunlinoo.067433No ratings yet

- Molecular and Chromosomal Mechanisms of Resistance To Imatinib (STI571) TherapyDocument8 pagesMolecular and Chromosomal Mechanisms of Resistance To Imatinib (STI571) TherapythainaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Myeloid LeukemiaDocument18 pagesChronic Myeloid LeukemiaNour AngriniNo ratings yet

- RTK InhDocument9 pagesRTK InhmonamustafaNo ratings yet

- Steegmann 1996Document6 pagesSteegmann 1996pishoi gergesNo ratings yet

- CML EsmoDocument3 pagesCML EsmowidweedNo ratings yet

- Ol 07 03 0791Document6 pagesOl 07 03 0791Irmagian PaleonNo ratings yet

- Mechanisms of Resistance To Imatinib and Second-GenerationDocument10 pagesMechanisms of Resistance To Imatinib and Second-GenerationRiyadh Z. MawloodNo ratings yet

- 2018 CML Updates and Case Presentations: Washington University in ST Louis Medical SchoolDocument113 pages2018 CML Updates and Case Presentations: Washington University in ST Louis Medical SchoolIris GzlzNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of Dasatinib in A CML Patient in Blast Crisis With F317L Mutation: A Case Report and Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesEfficacy of Dasatinib in A CML Patient in Blast Crisis With F317L Mutation: A Case Report and Literature ReviewMax Linares PatiñoNo ratings yet

- Neil Shah - Optimal Management of CML in 2015Document143 pagesNeil Shah - Optimal Management of CML in 2015Larrin StewartNo ratings yet

- Novel Targeted Therapies For Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in Elderly Patients: A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesNovel Targeted Therapies For Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia in Elderly Patients: A Systematic ReviewVishal BondeNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts in Pediatric Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument21 pagesCurrent Concepts in Pediatric Philadelphia Chromosome-Positive Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaCaballero X CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Imatinib: A Breakthrough of Targeted Therapy in CancerDocument10 pagesReview Article: Imatinib: A Breakthrough of Targeted Therapy in CancerMohammad AdhinNo ratings yet

- A Novel Somatic K-Ras Mutation in Juvenile Myelomonocytic LeukemiaDocument2 pagesA Novel Somatic K-Ras Mutation in Juvenile Myelomonocytic LeukemiamahanteshNo ratings yet

- Formulation and Evaluation of Dsatinib TabletsDocument9 pagesFormulation and Evaluation of Dsatinib TabletsSyed Abdul Haleem AkmalNo ratings yet

- Review Article On ImatinibDocument11 pagesReview Article On ImatinibNathan ColleyNo ratings yet

- Proliferation Inhibition and Apoptosis Induction of Imatinib-Resistant Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells Via PPP2R5C Down-RegulationDocument12 pagesProliferation Inhibition and Apoptosis Induction of Imatinib-Resistant Chronic Myeloid Leukemia Cells Via PPP2R5C Down-RegulationjessicaNo ratings yet

- Mecanismos Genómicos Que Influyen en El Resultado de La Leucemia Mieloide CrónicaDocument20 pagesMecanismos Genómicos Que Influyen en El Resultado de La Leucemia Mieloide Crónicamejia_jpNo ratings yet

- Ertao 2016Document7 pagesErtao 2016chemistpl420No ratings yet

- Jco 2001 19 18 3852Document9 pagesJco 2001 19 18 3852Luis SanchezNo ratings yet

- MR 25Document9 pagesMR 25Riko JumattullahNo ratings yet

- 2019 Article 729Document14 pages2019 Article 729Angel “LoveIsLove” RiveraNo ratings yet

- OncolyticDocument14 pagesOncolytichasna muhadzibNo ratings yet

- Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 Possible Involvement With - COR 2020 9 111Document6 pagesTransforming Growth Factor Beta 1 Possible Involvement With - COR 2020 9 111Melisa ClaireNo ratings yet

- Boll Et Al-2023-Scientific ReportsDocument14 pagesBoll Et Al-2023-Scientific ReportsJoy IsmailNo ratings yet

- LinfomaDocument9 pagesLinfomaRocio HaroNo ratings yet

- The Role of Polymorphic Cytochrome P450 Gene CYP2B 2Document13 pagesThe Role of Polymorphic Cytochrome P450 Gene CYP2B 2sherifref3atNo ratings yet

- Aberrations of MYC Are A Common Event in B-Cell Prolymphocytic LeukemiaDocument9 pagesAberrations of MYC Are A Common Event in B-Cell Prolymphocytic LeukemiaRafa AssidiqNo ratings yet

- Medical Progress: Review ArticlesDocument11 pagesMedical Progress: Review ArticlesEllie satrianiNo ratings yet

- CML Was Once Considered An Incurable DiseaseDocument2 pagesCML Was Once Considered An Incurable DiseaseAlison HinesNo ratings yet

- Practical Management of Patients With Chronic Myeloid LeukemiaDocument12 pagesPractical Management of Patients With Chronic Myeloid LeukemiakatevancuteNo ratings yet

- Identification of Recurring Tumor Specific Somatic Mutations in AML by Transcriptome Seq Greif2011Document7 pagesIdentification of Recurring Tumor Specific Somatic Mutations in AML by Transcriptome Seq Greif2011mrkhprojectNo ratings yet

- Biology Investigatory Project CMLDocument16 pagesBiology Investigatory Project CMLABHISHEK AjithkumarNo ratings yet

- MainDocument7 pagesMainKamila MuyasarahNo ratings yet

- A Case Report of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia With E8a2 BCR/ABL1 Fusion TranscriptDocument6 pagesA Case Report of Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia With E8a2 BCR/ABL1 Fusion TranscriptArdiles Robinson Rohi LagaNo ratings yet

- Leukemia & LymphomaDocument6 pagesLeukemia & LymphomaInggitaDarmawanNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Classification of Hematologic Malignancies On The Basis of GeneticsDocument16 pagesDiagnosis and Classification of Hematologic Malignancies On The Basis of GeneticsyunusaqNo ratings yet

- Molecular Detection of BCR-ABL Fusion GeneDocument14 pagesMolecular Detection of BCR-ABL Fusion GeneNimra ZulfiqarNo ratings yet

- Fphar 09 01497Document11 pagesFphar 09 01497Atina IraniNo ratings yet

- New Directions For Mantle Cell Lymphoma in 2022Document15 pagesNew Directions For Mantle Cell Lymphoma in 2022Luana MNo ratings yet

- DH76 坦桑尼亚慢性粒细胞白血病患者对伊马替尼的分子反应Document9 pagesDH76 坦桑尼亚慢性粒细胞白血病患者对伊马替尼的分子反应郑伟健No ratings yet

- ARTICULODocument9 pagesARTICULOJoOrge Victor Pichilingue CabelloNo ratings yet

- Imatinib Phase3 NEJM2003Document11 pagesImatinib Phase3 NEJM2003Stefán Broddi DaníelssonNo ratings yet

- Leukemia Thesis PDFDocument5 pagesLeukemia Thesis PDFjpwvbhiig100% (2)

- Tgf-b1 Expression as a Biomarker of Poor Prognosis Prostate Cancer هام جدا جدا نهايه محمد الاربعDocument5 pagesTgf-b1 Expression as a Biomarker of Poor Prognosis Prostate Cancer هام جدا جدا نهايه محمد الاربعMohammed SherifNo ratings yet

- 1999 DLBCL CD56Document7 pages1999 DLBCL CD56maomaochongNo ratings yet

- Chronic Myeloid LeukemiaDocument7 pagesChronic Myeloid LeukemiahemendreNo ratings yet

- Small Molecule Kinase Inhibitors From Lab Bench To ClinicDocument4 pagesSmall Molecule Kinase Inhibitors From Lab Bench To Clinicsatya_chagantiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 620355Document23 pagesNihms 620355JONATHAN ANDRE MORA QUIMBAYONo ratings yet

- Atypical CMLDocument5 pagesAtypical CMLBenyam ZenebeNo ratings yet

- Blastic Phase of Chronic Myelogenous LeukemiaDocument11 pagesBlastic Phase of Chronic Myelogenous LeukemiaMax Linares PatiñoNo ratings yet

- Review: Sti-571 in Chronic Myelogenous LeukaemiaDocument10 pagesReview: Sti-571 in Chronic Myelogenous Leukaemiatalenthero9xNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of C3435T MDR1 Gene Polymorphism in Adult Patient With Acute Lymphoblastic LeukemiaDocument4 pagesEvaluation of C3435T MDR1 Gene Polymorphism in Adult Patient With Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemiaali99No ratings yet

- Brown 2014Document9 pagesBrown 2014Rafaela Queiroz MascarenhasNo ratings yet

- Resistenci LLCDocument11 pagesResistenci LLCmarioNo ratings yet

- Cho Et Al-2019-International Journal of CancerDocument12 pagesCho Et Al-2019-International Journal of Cancerlouisehip UFCNo ratings yet

- Acute Myeloid Leukemia...Document20 pagesAcute Myeloid Leukemia...hemendre0% (1)

- Artigo OncoDocument14 pagesArtigo OncoCatarina LuísNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Factors For Chronic Lymphocytic LeukemiaDocument6 pagesPrognostic Factors For Chronic Lymphocytic LeukemiaJose AbadiaNo ratings yet

- Fast Facts: Treatment-Free Remission in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: From concept to practice and beyondFrom EverandFast Facts: Treatment-Free Remission in Chronic Myeloid Leukemia: From concept to practice and beyondNo ratings yet

- ResearchDocument52 pagesResearchhisyam_muhd8No ratings yet

- Nouvelle France Industrielle EnglishDocument76 pagesNouvelle France Industrielle EnglishasdasdNo ratings yet

- MorphineDocument3 pagesMorphineAizat KamalNo ratings yet

- Quiz Question 1 - MKSAP 17Document3 pagesQuiz Question 1 - MKSAP 17alaaNo ratings yet

- Instant Russia 6 NightsDocument7 pagesInstant Russia 6 Nightsshivam vermaNo ratings yet

- Problem Identification - Illuminate EducationDocument6 pagesProblem Identification - Illuminate Educationhailemecaile kfileNo ratings yet

- Bekele MirkenaDocument127 pagesBekele MirkenaSAIMA ZAMEER100% (1)

- Faculty of Applied SciencesDocument8 pagesFaculty of Applied SciencesShafiqahFazyaziqahNo ratings yet

- Iridology: The Iris Can Indicate A Problem in Its Earlier Inception, Long Before Disease Symptoms Are Present.Document3 pagesIridology: The Iris Can Indicate A Problem in Its Earlier Inception, Long Before Disease Symptoms Are Present.Shoeb MohammedNo ratings yet

- Wastewater TreatmentDocument60 pagesWastewater TreatmentPC YeapNo ratings yet

- Pediatrics: The Journal ofDocument11 pagesPediatrics: The Journal ofRohini TondaNo ratings yet

- Sinamics G180: Converters - Compact Units, Cabinet Systems, Cabinet Units Air-Cooled and Liquid-CooledDocument240 pagesSinamics G180: Converters - Compact Units, Cabinet Systems, Cabinet Units Air-Cooled and Liquid-CooledAnonymous PDNToMmNmRNo ratings yet

- Suicidal Ideation and Behavior in Adults - UpToDate PDFDocument36 pagesSuicidal Ideation and Behavior in Adults - UpToDate PDFLemuel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Early Adolescent Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Injury: A Case StudyDocument7 pagesEarly Adolescent Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Injury: A Case StudyfeliNo ratings yet

- 49366mss39118 3 PDFDocument6 pages49366mss39118 3 PDFManas Kumar SahooNo ratings yet

- Kharif Crops Vs Rabi CropsDocument1 pageKharif Crops Vs Rabi CropsAsim MushtaqNo ratings yet

- p385 90Document35 pagesp385 90Edward MacDermidNo ratings yet

- Input Data Sheet For E-Class Record: Region Division School Name School Id School YearDocument18 pagesInput Data Sheet For E-Class Record: Region Division School Name School Id School YearRonie DacubaNo ratings yet

- CSL Final - 3Document132 pagesCSL Final - 3adarshkalladayilNo ratings yet

- MODULE in Stat Week 6Document10 pagesMODULE in Stat Week 6Joshua GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Research-2 SynthesisDocument11 pagesResearch-2 SynthesisJesusValenciaNo ratings yet

- Vaginal Birth After Cesarean DeliveryDocument3 pagesVaginal Birth After Cesarean DeliveryShaira SariaNo ratings yet

- Owner's Manual: ST-series DDocument21 pagesOwner's Manual: ST-series DHarun ARIKNo ratings yet

- Daily Checklist: YES YES YES YES YES X YESDocument47 pagesDaily Checklist: YES YES YES YES YES X YESEdmar TabinasNo ratings yet

- DC Generator Equation of Induced Emf (Sample Problems)Document2 pagesDC Generator Equation of Induced Emf (Sample Problems)vincent gonzalesNo ratings yet

- Wire Edm, Edg, EddgDocument23 pagesWire Edm, Edg, EddgKrishna GopalNo ratings yet

- SANRAYDocument39 pagesSANRAYgopinadh57No ratings yet

- 1-Global Trends in Opencast Mining HemmDocument46 pages1-Global Trends in Opencast Mining Hemmjimcorbett099No ratings yet