Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Aluminum

Uploaded by

Ivana JocicCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Aluminum

Uploaded by

Ivana JocicCopyright:

Available Formats

Q&A: How aluminum changed the

world, for good and bad

by Matt Erickson, Drexel University

For many of the pieces of modern life that emerged and spread during the 20th

century, from air travel to electric service to cans of soda, you have aluminum to

thank.

The strong but lightweight metal helped change the world in ways previously

unimaginable. But the quest for more aluminum has also had damaging ripple effects

on the environment and indigenous populations around the world.

Those two sides of the aluminum story help explain why Drexel sociologist Mimi

Sheller has written a book about it. Sheller, a professor of sociology and the director

of the Center for Mobilities Research and Policy, studies how new infrastructure and

technology developments are changing the way people move around the earth—and

whether they can avoid damaging the earth in the process. Her book "Aluminum

Dreams: The Making of Light Modernity" was published by MIT Press earlier this

year, and DrexelNow spoke with her about why this is a metal worth writing about.

How does a sociologist come to write a book about an element in the periodic

table?

The kind of sociology I'm interested in has started to look at the intersection of social

or human processes with material and environmental processes. That's a really big

emerging field for research right now, sometimes called human and natural systems

research.

But my real interest in aluminum itself came out of my background of Caribbean

studies. The Caribbean region throughout the 20th century was the biggest source of

bauxite ore, the material mined to produce aluminum. When I started looking into the

impacts of bauxite mining and its role in Caribbean history, it connected me to the

global history of aluminum.

As far as its properties as a metal, what makes aluminum so useful?

Aluminum is very strong in proportion to its weight. So compared to steel or copper,

it has this lightness and yet a great strength at the same time. It's also nonmagnetic

and has corrosion-resistant properties. The weight and strength factors make it really

good for transportation, both in vehicles and in packaging. Its corrosion resistance

and nonmagnetic qualities make it really useful in building applications and electrical

equipment of any kind. When you put those things together, it became the ideal

metal for spaceships and satellites.

What has been its social and historical significance?

The book looks at what I call the light side and the dark side. The light side is that the

development of uses for aluminum and the accompanying innovation, creativity and

design brought us all sorts of wonderful things in the 20th century. It helped the

takeoff of civil aviation. It helped in bringing electric grids across the country. It

brought us all kinds of things around the home that were lighter and more durable,

and, of course, faster vehicles. And above all, I think the thing people think of most is

packaging: aluminum cans and aluminum foil.

The dark side is about a different kind of social impact: the impact on the regions of

the world where the mining takes place, and the pollutants that result. After bauxite

ore is mined, you're left with a substance called red mud, which has all kinds of

heavy metals and caustic substances in it. And the smelting of the ore into actual

metal is a really energy-intensive process. It required the building of huge

hydroelectric dams, many of the biggest in the world. And though hydroelectric

power is a "clean" energy in terms of carbon dioxide, it floods tens of thousands of

acres of land. Many of the places where that happened were on land appropriated

from indigenous, tribal or aboriginal peoples. So there have been a lot of human

rights violations that have helped make what I call "light modernity" possible.

What's the answer for the future?

The project took me from the red mud lakes left behind in Jamaica to the

hydroelectric projects being built in Iceland. When I went to Iceland, there was a big

protest movement against smelting. But what I found was that the activists

themselves were very dependent on aluminum. We flew in airplanes to get there. We

put up aluminum tent poles. We cooked vegan community meals in aluminum pots. It

made me think that there are some contradictions here. We can't just easily get rid of

this metal.

Aluminum is really valuable, and we actually need to value it more. As consumers,

we need to appreciate it and not just throw it away. It only takes 5 percent as much

energy to recycle your aluminum as it does to make it new. In the U.S., we throw

away about 55 billion cans each year, all of which could go back into production

quickly. But I realized that the other side that needs to be addressed is the

production side. A handful of big transnational corporations control the industry, and

they really need more transparency, accountability and corporate responsibility.

You might also like

- How Aluminum Changed The World A Metallurgical Revolution Through Technological and Cultural PerspectivesDocument13 pagesHow Aluminum Changed The World A Metallurgical Revolution Through Technological and Cultural PerspectivesGilberto Giner AlvídrezNo ratings yet

- The Metallurgy of Anodizing Aluminum: Connecting Science to PracticeFrom EverandThe Metallurgy of Anodizing Aluminum: Connecting Science to PracticeNo ratings yet

- What Is The History of Aluminum and Aluminum Welding?Document8 pagesWhat Is The History of Aluminum and Aluminum Welding?edgar zamoranNo ratings yet

- English Ironwork of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries - An Historical and Analytical Account of the Development of Exterior SmithcraftFrom EverandEnglish Ironwork of the XVIIth and XVIIIth Centuries - An Historical and Analytical Account of the Development of Exterior SmithcraftNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Midterm EssayDocument5 pagesChemistry Midterm EssayIrakli NatroshviliNo ratings yet

- Ironwork - Part III - A Complete Survey of the Artistic Working of Iron in Great Britain from the Earliest TimesFrom EverandIronwork - Part III - A Complete Survey of the Artistic Working of Iron in Great Britain from the Earliest TimesNo ratings yet

- What Is AluminumDocument2 pagesWhat Is AluminumHeath FletcherNo ratings yet

- METALLURGY AND WHEELS - The Story of Men, Metals and MotorsFrom EverandMETALLURGY AND WHEELS - The Story of Men, Metals and MotorsNo ratings yet

- Concrete - The GuardianDocument5 pagesConcrete - The GuardianmarianasantangeloNo ratings yet

- The Substance of Civilization: Materials and Human History from the Stone Age to the Age of SiliconFrom EverandThe Substance of Civilization: Materials and Human History from the Stone Age to the Age of SiliconNo ratings yet

- Material WorldDocument188 pagesMaterial WorldYahaya HassanNo ratings yet

- Gr8 EVM - Lithosphere Home Notes - 2023-24 - Final EditedDocument6 pagesGr8 EVM - Lithosphere Home Notes - 2023-24 - Final Editedparijaatwaghmare21No ratings yet

- Ironwork - Part I - From the Earliest Times to the End of the Mediaeval PeriodFrom EverandIronwork - Part I - From the Earliest Times to the End of the Mediaeval PeriodRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 202 Introduction To Materials ScienceDocument435 pages202 Introduction To Materials ScienceRK SinghNo ratings yet

- Engineering MaterialDocument399 pagesEngineering MaterialMario ParhanNo ratings yet

- Ironwork - Part II - Being a Continuation of the First Handbook, and Comprising from the Close of the Mediaeval Period to the End of the Eighteenth Century, Excluding English WorkFrom EverandIronwork - Part II - Being a Continuation of the First Handbook, and Comprising from the Close of the Mediaeval Period to the End of the Eighteenth Century, Excluding English WorkNo ratings yet

- Assignment of Chemistry: Govt - Postgraduate College GojraDocument10 pagesAssignment of Chemistry: Govt - Postgraduate College GojraAmjid AliNo ratings yet

- High-Speed Steel - The Development, Nature, Treatment, and use of High-Speed Steels, Together with Some Suggestions as to the Problems Involved in their UseFrom EverandHigh-Speed Steel - The Development, Nature, Treatment, and use of High-Speed Steels, Together with Some Suggestions as to the Problems Involved in their UseNo ratings yet

- Chapter 26 OutlineDocument4 pagesChapter 26 OutlineFerrari80% (5)

- Summary of Atomic Accidents: by James Mahaffey | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of Atomic Accidents: by James Mahaffey | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- 4000 Years Later - HyLDocument48 pages4000 Years Later - HyLRodrigo Morales AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Technological BreakthroughsDocument7 pagesTechnological BreakthroughsHareem TahirNo ratings yet

- Heat-Treatment of Steel: A Comprehensive Treatise on the Hardening, Tempering, Annealing and Casehardening of Various Kinds of Steel: Including High-speed, High-Carbon, Alloy and Low Carbon Steels, Together with Chapters on Heat-Treating Furnaces and on Hardness TestingFrom EverandHeat-Treatment of Steel: A Comprehensive Treatise on the Hardening, Tempering, Annealing and Casehardening of Various Kinds of Steel: Including High-speed, High-Carbon, Alloy and Low Carbon Steels, Together with Chapters on Heat-Treating Furnaces and on Hardness TestingRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Concrete The Most Destructive Material On EarthDocument14 pagesConcrete The Most Destructive Material On Earthlynnha09No ratings yet

- The Journey of Silicon From The Big Bang To Adoption in Nanotechnology To Tri-Gate TechnologyDocument13 pagesThe Journey of Silicon From The Big Bang To Adoption in Nanotechnology To Tri-Gate TechnologyAbdulrahman Suleman AhmedNo ratings yet

- Material Science IISc BookDocument810 pagesMaterial Science IISc BookSoumyadeep MannaNo ratings yet

- Materials Science: Course Motivation and HighlightsDocument4 pagesMaterials Science: Course Motivation and Highlightskh_gallardoNo ratings yet

- Aluminum Patio Furniture: Chemistry AdsDocument4 pagesAluminum Patio Furniture: Chemistry AdsBookfanatic13No ratings yet

- Need To FinishDocument6 pagesNeed To FinishCely Marie VillarazaNo ratings yet

- Out of The Fiery Furnace The Impact of Metals On The History ofDocument296 pagesOut of The Fiery Furnace The Impact of Metals On The History ofLeland Stanford0% (1)

- Metallurgy and ShipbuildingDocument3 pagesMetallurgy and Shipbuildingbrandondavis1011No ratings yet

- Material Science Multiple ChoiceDocument946 pagesMaterial Science Multiple ChoiceMs. D. Shruthi Keerthi100% (1)

- The Second Industrial RevolutionDocument4 pagesThe Second Industrial RevolutionNeko ShiroNo ratings yet

- Af5 2077430Document6 pagesAf5 2077430Lesly Michell Rubio CanobbioNo ratings yet

- GSG101Document20 pagesGSG101MaishaNo ratings yet

- Material ScienceDocument810 pagesMaterial ScienceNikhil Batham67% (3)

- Materials ScienceDocument368 pagesMaterials ScienceHarinderpal Singh Pannu100% (1)

- Uses - Periodic Table, FromDocument2 pagesUses - Periodic Table, FromReihan JajiminNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument18 pagesBackground of The StudyCely Marie VillarazaNo ratings yet

- ALUMINUM - Chemistry PresentationDocument8 pagesALUMINUM - Chemistry PresentationAkshay BankayNo ratings yet

- Unit 2: Begining of A New Era Industrial RevolutionDocument27 pagesUnit 2: Begining of A New Era Industrial RevolutionManoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Bakelite Materials Landmark Lesson PlanDocument11 pagesBakelite Materials Landmark Lesson Planmohammedtaher mohammed saeed mulapeerNo ratings yet

- 125 Years of Developments in DentistryDocument4 pages125 Years of Developments in DentistryShoaib A. KaziNo ratings yet

- The Industrial RevolutionDocument9 pagesThe Industrial RevolutionMihaela OlaruNo ratings yet

- TOP 10 Inventions in Human HistoryDocument2 pagesTOP 10 Inventions in Human HistoryAEHYUN YENVYNo ratings yet

- Impact of Industrial Revolution On World ArchitectureDocument3 pagesImpact of Industrial Revolution On World ArchitectureMohd Asif AnsariNo ratings yet

- Assignment No-02: (Document Subtitle)Document18 pagesAssignment No-02: (Document Subtitle)Mah NoorNo ratings yet

- Valeri Consulenza IndustrialeDocument4 pagesValeri Consulenza IndustrialeGualtiero A.N.ValeriNo ratings yet

- Poslovne Komunikacije SkriptaDocument86 pagesPoslovne Komunikacije SkriptaMarijana StanisavljevicNo ratings yet

- Bensaude - Plastics Materials Dematerialization - Capítulo - 2013Document19 pagesBensaude - Plastics Materials Dematerialization - Capítulo - 2013Alexandra BejaranoNo ratings yet

- History of AluminumDocument13 pagesHistory of AluminumJohn Paul Cristobal100% (1)

- Foudary ProjectDocument10 pagesFoudary ProjectTochukwu TimothyNo ratings yet

- Schatzberg Aircraft, Engineering HistoryDocument37 pagesSchatzberg Aircraft, Engineering HistoryLuigi CervantesNo ratings yet

- Material Science (IISc Bangalore)Document272 pagesMaterial Science (IISc Bangalore)Suresh Khangembam100% (9)

- The Bronze Age Article by Kumkum RoyDocument25 pagesThe Bronze Age Article by Kumkum RoyShruti JainNo ratings yet

- Ea The NassirDocument1 pageEa The NassirCannolo Di MercaNo ratings yet

- Paper 2 Paper With Solution ChemistryDocument14 pagesPaper 2 Paper With Solution ChemistryddssdsfsNo ratings yet

- 175 171500Document3 pages175 171500balajiNo ratings yet

- Berol PBX Peroxide CleanersDocument7 pagesBerol PBX Peroxide CleanersjcriveroNo ratings yet

- NS-BP112/NS-BP102 CRX-B370/CRX-B370D: MCR-B370/MCR-B270/ MCR-B370D/MCR-B270DDocument65 pagesNS-BP112/NS-BP102 CRX-B370/CRX-B370D: MCR-B370/MCR-B270/ MCR-B370D/MCR-B270DVicente Fernandez100% (1)

- Gas Dehydration and Molecular Sieves FPSO SaquaremaDocument28 pagesGas Dehydration and Molecular Sieves FPSO SaquaremamohammedNo ratings yet

- Ion Exchange Resins Selectivity - 45-D01458-EnDocument4 pagesIon Exchange Resins Selectivity - 45-D01458-EnDFMNo ratings yet

- Fisa - Tehnica - DH PFM922I 5EUN C 100 - enDocument2 pagesFisa - Tehnica - DH PFM922I 5EUN C 100 - enCosmin CurticapeanNo ratings yet

- Enzymatic Assay of XYLANASE (EC 3.2.1.8) PrincipleDocument4 pagesEnzymatic Assay of XYLANASE (EC 3.2.1.8) Principlesyaza amiliaNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Operational Inspection of A Fluidised Bed Combustion BoilerDocument31 pagesCase Study On Operational Inspection of A Fluidised Bed Combustion Boilerparthi20065768No ratings yet

- Rotary CoatingDocument5 pagesRotary Coatinggalati12345No ratings yet

- 2018 ThermogravimetricAnalysisofPolymersBookChapter PDFDocument30 pages2018 ThermogravimetricAnalysisofPolymersBookChapter PDFA1234 AJEFNo ratings yet

- Ceramic CatalogDocument5 pagesCeramic CatalogJose Manuel Sánchez LópezNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Building Materials For Fire Protection - Engineering ReferenceDocument5 pagesHandbook of Building Materials For Fire Protection - Engineering ReferenceDorinNo ratings yet

- Materials Comparison DIN / EN / ASTM: Pipes / Tubes Flanges Buttwelding FittingsDocument1 pageMaterials Comparison DIN / EN / ASTM: Pipes / Tubes Flanges Buttwelding Fittingsnaseema1No ratings yet

- Review On Metallization Approaches For High-Efficiency Silicon Heterojunction Solar CellsDocument16 pagesReview On Metallization Approaches For High-Efficiency Silicon Heterojunction Solar Cells蕭佩杰No ratings yet

- GL005 PIPE ROUTING GUIDELINE Rev 2Document22 pagesGL005 PIPE ROUTING GUIDELINE Rev 2MIlanNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Mechanical Stress On Semiconductor DevicesDocument3 pagesThe Effects of Mechanical Stress On Semiconductor Devicesvishnu vardhanNo ratings yet

- Diaphragm Design GuideDocument29 pagesDiaphragm Design GuideJaher Wasim100% (1)

- Pro To Tools Catalog PR 621201962Document84 pagesPro To Tools Catalog PR 621201962OSEAS GOMEZNo ratings yet

- Add AcidDocument4 pagesAdd AcidKathir KiranNo ratings yet

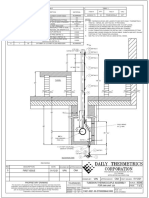

- Proprietary Drawing: CAA VPN 01/12/21 First Issue 0Document2 pagesProprietary Drawing: CAA VPN 01/12/21 First Issue 0Francelina VegaNo ratings yet

- Structure and Properties of WaterDocument6 pagesStructure and Properties of WaterBrendan Lewis DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Noble Metalfree Hydrogen Evolution Catalysts For Water Splitting2015chemical Society ReviewsDocument34 pagesNoble Metalfree Hydrogen Evolution Catalysts For Water Splitting2015chemical Society ReviewsDaniel Camilo CanoNo ratings yet

- 4860 Molenaar IIIDocument165 pages4860 Molenaar IIIJhinson BriceñoNo ratings yet

- BT Reviewer PrelimsDocument3 pagesBT Reviewer PrelimsDianalen RosalesNo ratings yet

- Smith Industries WaterBath Indirect Heater PDFDocument29 pagesSmith Industries WaterBath Indirect Heater PDFcassindromeNo ratings yet

- Traffic Analysis and Design of Flexible Pavement With Cemented Base and SubbaseDocument7 pagesTraffic Analysis and Design of Flexible Pavement With Cemented Base and Subbasemspark futuristicNo ratings yet

- Technical Bulletin: Valdisk TX3 Triple Offset Butterfly Control ValveDocument20 pagesTechnical Bulletin: Valdisk TX3 Triple Offset Butterfly Control ValveAhmed KhairiNo ratings yet

- Astm C1567 - 13 PDFDocument6 pagesAstm C1567 - 13 PDFAnonymous SBjNS7Gw0qNo ratings yet

- Tankguard Plus PDFDocument11 pagesTankguard Plus PDFAbrar HussainNo ratings yet

- Dark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseFrom EverandDark Matter and the Dinosaurs: The Astounding Interconnectedness of the UniverseRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (69)

- The Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsFrom EverandThe Other End of the Leash: Why We Do What We Do Around DogsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (65)

- The Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildFrom EverandThe Lives of Bees: The Untold Story of the Honey Bee in the WildRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (44)

- Alex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessFrom EverandAlex & Me: How a Scientist and a Parrot Discovered a Hidden World of Animal Intelligence—and Formed a Deep Bond in the ProcessNo ratings yet

- Spoiled Rotten America: Outrages of Everyday LifeFrom EverandSpoiled Rotten America: Outrages of Everyday LifeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (19)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (812)

- The Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorFrom EverandThe Revolutionary Genius of Plants: A New Understanding of Plant Intelligence and BehaviorRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (137)

- When You Find Out the World Is Against You: And Other Funny Memories About Awful MomentsFrom EverandWhen You Find Out the World Is Against You: And Other Funny Memories About Awful MomentsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldFrom EverandThe Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A New History of a Lost WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (597)

- Fire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness LookoutFrom EverandFire Season: Field Notes from a Wilderness LookoutRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (142)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- World of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsFrom EverandWorld of Wonders: In Praise of Fireflies, Whale Sharks, and Other AstonishmentsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (223)

- Come Back, Como: Winning the Heart of a Reluctant DogFrom EverandCome Back, Como: Winning the Heart of a Reluctant DogRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (10)

- Remnants of Ancient Life: The New Science of Old FossilsFrom EverandRemnants of Ancient Life: The New Science of Old FossilsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Darwin's Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent DesignFrom EverandDarwin's Doubt: The Explosive Origin of Animal Life and the Case for Intelligent DesignRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Wayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldFrom EverandWayfinding: The Science and Mystery of How Humans Navigate the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- The Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceFrom EverandThe Mind of Plants: Narratives of Vegetal IntelligenceRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Roxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingFrom EverandRoxane Gay & Everand Originals: My Year of Psychedelics: Lessons on Better LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (35)

- The Hawk's Way: Encounters with Fierce BeautyFrom EverandThe Hawk's Way: Encounters with Fierce BeautyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (19)