Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lord Harold Pilgrimage

Uploaded by

Vanessa RidolfiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lord Harold Pilgrimage

Uploaded by

Vanessa RidolfiCopyright:

Available Formats

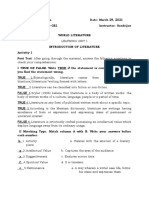

‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’

is divided into four cantos, or the poetic version of chapters, that are

written in Spenserian stanzas. This means that in each stanza (including those below), readers can find

eight lines written in iambic pentameter and a final line that’s structured as an Alexandrine. This means

that the ninth line of every stanza has twelve iambic syllables. The poet also chose to use a pattern of

ABABBCDCC throughout this poem.

Byron famously woke up to find himself famous after the publication of cantos I and II of Childe Harold

when he was 24. Those cantos are more or less the poetic journal of a trip Byron took with friends (in

particular his close confidant John Cam Hobhouse) through the regions of Europe not occupied by

Napoleon Bonaparte’s French forces; the areas held by Napoleon were enemy territory for an Englishman.

Accordingly, Byron traveled through Portugal, Spain, Malta, Albania, Greece, and Turkey, whose Ottoman

Empire extended over Greece, and Byron would die championing the cause of Greek independence, the

loss of which he laments in Childe Harold.

Indeed, the poem is about the meaning of freedom in all its forms - personal, political, poetic. In canto I,

Byron joins with William Wordsworth and with a host of others to heap scorn on the Convention of Cintra,

the terms by which the British bureaucracy agreed to allow the French forces Admiral Arthur Wellesley

had soundly defeated in Portugal in 1808 (a major incident in the Peninsular War against Napoleon) to

leave Portugal and Spain with their loot intact. For Byron, Britain was on the right side of the Peninsular

War, since Napoleon had come to represent conquest and tyranny. He accordingly celebrates Iberian

resistance to Napoleon’s superior forces, and throughout Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage he takes the side of

the conquered over their conquerors.

In particular, this takes the form of commitment to Greek independence, a cause for which Byron would

later fight and die. In the poem, what he sees everywhere he goes is emptiness and loss. In Greece the

loss is that of the glorious past and the great writers who belong to that past; in Albania it is the sublime

emptiness of the wilderness. Everywhere it is the indifference of time and fate and nature to human

ambition. Byron’s predilection for battlefields (which he explicitly mentions in a footnote to canto III) is for

them as a place in which the most intense passion and pain display their ultimate pointlessness.

It is this sense of pointlessness—to be found in the ultimate insignificance of poetry as well as of political

power—that Byron finds everywhere. The work of the poem is to transmute that feeling into one of

freedom. Harold, who barely exists in the poem (he was originally to be called Burun, the old spelling of

the Byron family name), is attempting to escape his own past by leaving England for the wastes of ocean

and of a fabulous elsewhereness. He is Byron reduced to his own poetic perception, judgment, and

feeling, “The wandering outlaw of his own dark mind” (III, l. 20). Indeed, Byron sees him as a kind of

avatar by whose creation he can transform his nothingness into “A being more intense,” by an

apprehension of that very nothingness, “feeling still with thee”—his fictional avatar Harold—“in my crush’d

feelings’ dearth” (III, ll. 47–54).

All experience testifies to the nothingness that affords Byron the intensity of its own apprehension: “There

is a very life in our despair” (III, l. 298). The final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, the battlefield Byron

visits in canto III (and describes in a passage that will incite William Makepeace Thackeray’s great

Waterloo scene in Vanity Fair), the later autobiographical projection he undertakes in his praise of “the

selftorturing sophist, wild Rousseau” (III, l. 725; cantos III and IV are significant influences on Percy

Bysshe Shelley’s The Triumph of Life, which also contains a memorable account of the French philosopher

JeanJacques Rousseau, perhaps the first romantic) all lead to the placement of nature above any human

significance. As Byron explains in one of his many footnotes, which are essential to the poem’s integrity,

when describing the scenery of the Alps where Rousseau set his novel Julie: “If Rousseau had never

written, nor lived, the same associations would not less have belonged to such scenes. He has added to

the interest of his works by their adoption; he has shown his sense of their beauty by the selection; but

they have done that for him which no human being could do for them” (note to III, l. 940).

This is a telling claim. When canto III of Childe Harold came out, Wordsworth complained about Byron

(who, like Shelley, is often talking about the still-living Wordsworth when he refers to Rousseau) that his

hymn to nature was derived from Tintern Abbey. There is much justice in this claim. Byron had described

himself in canto II as the child of nature, as “Her neverwean’d, though not her favour’d child” (II, l. 328).

If we take Wordsworth to be her favorite child (as he himself often claimed), then we can see that Byron’s

relationship to nature is not quite Wordsworthian. For Wordsworth, it is nature that instills within him his

vocation as a poet, even if in the end he can transcend nature and plumb the depths of his own soul.

Indeed, it is that exploration of selfhood that makes poetic vocation greater and deeper than the

experience of nature that catalyzes it. But for Byron, nature is greater than the poet who celebrates her.

Poetry is our trivial human way of recording our experience of nature. However, nature is all in all.

(Shelley’s “Mont Blanc,” written during the summer he and Byron both visited the mountain and the

surrounding regions, is a kind of rebuttal of this conclusion.)

The odd and paradoxical effect of Childe Harold is that it testifies to the most important fact about Byron

as a poet: Unlike any of the other romantics, he did not imagine being a poet as a transcendent fact. His

refusal of such a claim is part of his greatness, but it is a refusal nonetheless. In comparing himself with

Napoleon and with Rousseau, he is acknowledging the ultimate triviality of what he is doing, even while

using the language of overweening pride. His poetry is more fully about nature than that of any other

romantic poet, because it is least about the depths of selfhood. Of course, Byron’s overwhelming and

intoxicating personality can be felt in every page he writes. But he refuses to go deep, and this refusal

returns us to the nature and freedom from self that he found in nature. Poetry is for Byron a means, and

not an end: a means to finding freedom finally in the nature it celebrates. It is this fact—most palpable

in Childe Harold—that displays both Byron’s greatness and his limitations. Those limitations are the very

subject of his poetry; they are what make it great, and they are also where he finds the freedom to be

overwhelming and intoxicating, a freedom he preferred to the implacable demands of the uncompromising

poetic vocation of the other romantics.

The first lines of this section of ‘Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage’ are some of the poet’s best-known. He writes

of the “pathless woods,” “lonely shore,” and his love for nature. The celebration of nature’s beauty and

power is a theme found throughout Byron’s work (and the work of others from this period).

The poet opens this section by speaking of all the pleasures that can be taken from nature and how his

love for the natural world does not decrease his love of humankind. The two things exist at the same

time. The poet’s speaker emphasizes the fact that when he spends time in nature, he feels as though he’s

mingled with the Universe or merged with the world and all its complex pieces. He’s hoping to convey this

connection to the reader and inspire them to consider nature in the same way. It’s hard for him to

express the way that these experiences make him feel, he continues on to say, but he also has a hard

time “conceal[ing]” or hiding his feelings. These two facts of his experience are what drive the following

lines.

In the section entitled “Apostrophe to the Ocean” Byron does his best to explain the overwhelming power

and justice of the ocean. While he acknowledges his inability to fully describe these characteristics, he

also proclaims the truth of his statements. He writes, “ . . . I steal / From all I may be, or have been

before, / To mingle with the Universe, and feel / What I can ne’er express, yet can not all conceal” (lines

1599-1602). He describes leaving behind his previous self—somewhat like shedding a skin—and looking

with honesty at the truth of things or the things which cannot be concealed. He writes of facts that cannot

be hidden either through intentional disguises or through a lack of appropriate words. Byron appears to be

rejecting the falseness of men, the claims of human dominance, and the façade of civilization. Byron looks

at the works of men that were designed to conquer lesser things and sees failure and pretence. He writes,

“Ten thousand fleets sweep over thee in vain; / Man marks the earth with ruin—his control / Stops with

the shore” (lines 1604-1606).

You might also like

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Last Ride Together As A Dramatic MonologueDocument2 pagesLast Ride Together As A Dramatic MonologueJuhi Neogi90% (10)

- The Waste Land Section IDocument5 pagesThe Waste Land Section ILinaNo ratings yet

- 6 Poem AnalysisDocument4 pages6 Poem AnalysisSadieMillsNo ratings yet

- Independent Reading Journal PromptsDocument3 pagesIndependent Reading Journal PromptsRegina DeBeathamNo ratings yet

- Summary of WastelanddDocument12 pagesSummary of Wastelanddfiza imranNo ratings yet

- Enotes Childe Harolds Pilgrimage GuideDocument18 pagesEnotes Childe Harolds Pilgrimage GuideMEGHA GNo ratings yet

- Emily Bronte and German PoetsDocument4 pagesEmily Bronte and German Poetsgiwrgos25No ratings yet

- The Issue of Subjective Narration in Paradise LostDocument3 pagesThe Issue of Subjective Narration in Paradise LostLaurent Alibert100% (1)

- Mam SalmaDocument14 pagesMam Salmaunique technology100% (2)

- The Second ComingDocument26 pagesThe Second ComingMuhammadAmin100% (1)

- HD ModernismDocument22 pagesHD ModernismVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- HD ModernismDocument22 pagesHD ModernismVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Romanticism and ByronDocument3 pagesRomanticism and ByronPaulescu Daniela AnetaNo ratings yet

- Wellek Name and Nature of Comparative LiteratureDocument17 pagesWellek Name and Nature of Comparative Literatureresistancetotheory100% (6)

- Introduction To Age of Milton: Important McqsDocument13 pagesIntroduction To Age of Milton: Important Mcqsahdia ahmed50% (2)

- Pathless WoodsDocument3 pagesPathless WoodsSURESH GUPTANo ratings yet

- Byron CH Canto 3Document2 pagesByron CH Canto 3Sahildeep 1035No ratings yet

- LORD ByronDocument14 pagesLORD ByronManu JamesNo ratings yet

- The Ocean Lord Byron: Childe Harold's Pilgrimage Continues The Poet's JourneyDocument6 pagesThe Ocean Lord Byron: Childe Harold's Pilgrimage Continues The Poet's JourneyPushpanathan ThiruNo ratings yet

- Childe Harold by G. G. ByronDocument2 pagesChilde Harold by G. G. ByronMarina VasilicNo ratings yet

- Lord Byron's Poetry Explored Romantic Themes of Nature, Love, and ArtDocument3 pagesLord Byron's Poetry Explored Romantic Themes of Nature, Love, and ArtPaulescu Daniela AnetaNo ratings yet

- Lord Byron On MarmoreDocument7 pagesLord Byron On MarmoreThalNo ratings yet

- Lord Byron's 'She Walks in Beauty' AnalysisDocument7 pagesLord Byron's 'She Walks in Beauty' Analysiskspalmo100% (1)

- PoemsDocument17 pagesPoemsGheorghe AlexandraNo ratings yet

- RomanticismDocument7 pagesRomanticismklau2No ratings yet

- English Romantics 2Document6 pagesEnglish Romantics 2natassayannakouliNo ratings yet

- Is All Wandering The "Worst of Sinning"? Don Juan by Lord ByronDocument12 pagesIs All Wandering The "Worst of Sinning"? Don Juan by Lord ByronJulian ScuttsNo ratings yet

- The Byronic HeroDocument5 pagesThe Byronic HeroStanley Sfekas0% (1)

- Summary of Child Harold Canto IIIDocument3 pagesSummary of Child Harold Canto IIISr Chandrodaya JNo ratings yet

- Philip Larkin Is One of BritainDocument7 pagesPhilip Larkin Is One of Britainchandravinita100% (1)

- 19 B THE ROMANTIC PERIOD First GenerationDocument6 pages19 B THE ROMANTIC PERIOD First GenerationGalo2142No ratings yet

- Lord Byron's Influence on English LiteratureDocument10 pagesLord Byron's Influence on English LiteratureMadalina BivolaruNo ratings yet

- Lazer, Hank - Gregory Orr Resources of The Personal Lyric, American Poetry ReviewDocument20 pagesLazer, Hank - Gregory Orr Resources of The Personal Lyric, American Poetry ReviewRES2014No ratings yet

- The Byronic Hero: Abstract: George Gordon Byron Wrote Poetry of An Extraordinary Range and DiversityDocument6 pagesThe Byronic Hero: Abstract: George Gordon Byron Wrote Poetry of An Extraordinary Range and DiversityMohammed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Lord Byron' S Don JuanDocument5 pagesLord Byron' S Don JuanIrina DabijaNo ratings yet

- Summary of The Waste Land Section IDocument3 pagesSummary of The Waste Land Section IaniNo ratings yet

- The Waste LandDocument14 pagesThe Waste LandMartina AquinoNo ratings yet

- America Formalism Approach - Melissa HalimDocument3 pagesAmerica Formalism Approach - Melissa HalimMelissahalimNo ratings yet

- Seminar PaperDocument14 pagesSeminar PaperEmira RamićNo ratings yet

- Victorian Poetry With Special Reference To Tennyson and BrowningDocument3 pagesVictorian Poetry With Special Reference To Tennyson and BrowningTaibur Rahaman100% (2)

- SarratDocument8 pagesSarratSutanu SahuNo ratings yet

- The Mechanism of The Imagination in Coleridge - S WritingDocument2 pagesThe Mechanism of The Imagination in Coleridge - S WritingCracan Ruxandra IoanaNo ratings yet

- Wordsworth, Coleridge and Realism Critical EssayDocument17 pagesWordsworth, Coleridge and Realism Critical EssayMartyn SmithNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes by Ananya Bose - Lord ByronDocument4 pagesLecture Notes by Ananya Bose - Lord ByronpoojaNo ratings yet

- P B ShellyDocument60 pagesP B ShellyStudy GuideNo ratings yet

- Evaluate Tennyson, Browning and Mathew Arnold As The Representative Poets of The Victorian AgeDocument3 pagesEvaluate Tennyson, Browning and Mathew Arnold As The Representative Poets of The Victorian AgePriyanka DasNo ratings yet

- 8.philip LarkinDocument3 pages8.philip Larkinazmat.pti.ikNo ratings yet

- BYRON'S CHILDE HAROLDDocument4 pagesBYRON'S CHILDE HAROLDLeonia StingaciNo ratings yet

- Strange Meeting: 1. Lake Poet, Any of The English PoetsDocument5 pagesStrange Meeting: 1. Lake Poet, Any of The English Poetszeeshanali1No ratings yet

- She Walks in Beaut1Document4 pagesShe Walks in Beaut1Faisal JahangeerNo ratings yet

- Modernist_poetry_lectures-1 (1)Document7 pagesModernist_poetry_lectures-1 (1)aminaimo33No ratings yet

- Dalrev Vol47 Iss4 Pp526 534Document9 pagesDalrev Vol47 Iss4 Pp526 53499 SAJNo ratings yet

- Poetry Is A Genre of LiteratureDocument10 pagesPoetry Is A Genre of LiteratureMohsin IftikharNo ratings yet

- ELT-313-3rd-exam-reviewer-1Document8 pagesELT-313-3rd-exam-reviewer-1kylamendiola543No ratings yet

- DocumentDocument3 pagesDocumentZaid AliNo ratings yet

- Tinternabbey: William WordsorthDocument9 pagesTinternabbey: William WordsorthFayyaz Ahmed IlkalNo ratings yet

- WORDSWORTHDocument9 pagesWORDSWORTHfrancesca giustizieriNo ratings yet

- Poetry: 2. The Essentials of PoetryDocument7 pagesPoetry: 2. The Essentials of PoetryMohsin IftikharNo ratings yet

- Dramatic MonologueDocument4 pagesDramatic MonologuebushreeNo ratings yet

- Zadorojniac MirabelaDocument4 pagesZadorojniac MirabelaMira ZadorojniacNo ratings yet

- Manitou Telehandler Mt420h Repair Manual 647781Document22 pagesManitou Telehandler Mt420h Repair Manual 647781vanessaroth010300kxg100% (125)

- Ocean_imagery_in_Don_Juan_the_symbolismDocument16 pagesOcean_imagery_in_Don_Juan_the_symbolismVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- BYRON'S LIFE_BloomDocument3 pagesBYRON'S LIFE_BloomVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- COMPARING QUANTITESDocument1 pageCOMPARING QUANTITESVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- She Walks in BeautyDocument3 pagesShe Walks in BeautyVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Ocean_imagery_in_Don_Juan_the_symbolismDocument16 pagesOcean_imagery_in_Don_Juan_the_symbolismVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- From Old English To Middle EglishDocument3 pagesFrom Old English To Middle EglishVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Conrad's LanguageDocument2 pagesConrad's LanguageVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Heart of Darkness - 1Document22 pagesHeart of Darkness - 1Vanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Poe's Psychological HorrorDocument3 pagesPoe's Psychological HorrorVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- PuritanismDocument1 pagePuritanismVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- From Old English To Middle EglishDocument3 pagesFrom Old English To Middle EglishVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- c1 Word FormationDocument1 pagec1 Word FormationVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- P.b.shelley - RamsesDocument1 pageP.b.shelley - RamsesVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- The Bluest EyesDocument3 pagesThe Bluest EyesVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- The Sugar BoycottDocument2 pagesThe Sugar BoycottVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Poe's Psychological HorrorDocument3 pagesPoe's Psychological HorrorVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- Eveline AnalysisDocument2 pagesEveline AnalysisVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- The Bluest EyesDocument3 pagesThe Bluest EyesVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- DR Jeckill Textual AnalysisDocument1 pageDR Jeckill Textual AnalysisVanessa RidolfiNo ratings yet

- 11th Grade Best Work Reflective Essay-2Document2 pages11th Grade Best Work Reflective Essay-2api-546077527No ratings yet

- Chapter7 - Evaluating and Selecting Yal - WreportDocument23 pagesChapter7 - Evaluating and Selecting Yal - WreportJade Nathalie SalesNo ratings yet

- Unit One 1.1 The Concept of Creative WritingDocument40 pagesUnit One 1.1 The Concept of Creative WritingMuhammedNo ratings yet

- Daddy by Silvia Plath'sDocument5 pagesDaddy by Silvia Plath'sTaufiqEm-sNo ratings yet

- M A Englishfortheexaminations2021Document137 pagesM A Englishfortheexaminations2021RadhikaNo ratings yet

- Fil Literature CompilationDocument15 pagesFil Literature Compilationbeafalla76No ratings yet

- Group 4 PPT ContempoDocument18 pagesGroup 4 PPT ContempoPatricia AmparoNo ratings yet

- English Language and Literature OBSPriceListDocument176 pagesEnglish Language and Literature OBSPriceListhdsjhNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals Writing Prompts: TechnicalDocument25 pagesFundamentals Writing Prompts: TechnicalFjvhjvgNo ratings yet

- Group 9 AbikuDocument3 pagesGroup 9 AbikuSegun AlongeNo ratings yet

- Figurative Language Lesson on Robert Louis Stevenson's Poem "The WindDocument13 pagesFigurative Language Lesson on Robert Louis Stevenson's Poem "The WindShekaena Angela G. AndayaNo ratings yet

- Poetry - Rhythm, Rhyme, and Other Useful Areas!Document76 pagesPoetry - Rhythm, Rhyme, and Other Useful Areas!maullinNo ratings yet

- 366 Attachement CatalogueDocument67 pages366 Attachement CatalogueAlexNo ratings yet

- Vivaan Daga - Paper-1 LiteratureDocument7 pagesVivaan Daga - Paper-1 Literaturejosephfren21No ratings yet

- Elements of Poetry: Meter and FormDocument2 pagesElements of Poetry: Meter and FormNany NoNo ratings yet

- Nta Ugc Net June 2023 – English Shift 1Document33 pagesNta Ugc Net June 2023 – English Shift 1anuzbaluNo ratings yet

- LESSON 2-Japanese LiteratureDocument11 pagesLESSON 2-Japanese LiteratureArriane ReyesNo ratings yet

- Ruby in The DuuDocument373 pagesRuby in The DuuGaneshNo ratings yet

- The Beauty of Nature in an Unexpected PlaceDocument11 pagesThe Beauty of Nature in an Unexpected Place04 10 B Parth ChotaliyaNo ratings yet

- How Our Forebears Transmitted LiteratureDocument2 pagesHow Our Forebears Transmitted LiteraturePagobo Beerich MarieNo ratings yet

- Survey of Philippine LiteratureDocument15 pagesSurvey of Philippine LiteratureKayzel ManglicmotNo ratings yet

- 21ST Century Literature - Q3 - Las 2Document6 pages21ST Century Literature - Q3 - Las 2Shiva Avel YeeNo ratings yet

- Xi 2.2 The SowerDocument10 pagesXi 2.2 The SoweryashviNo ratings yet

- Word Literature Act.1Document2 pagesWord Literature Act.1Rhacell Palapar RutaNo ratings yet

- ĐỀ TEST CỦA BI READING & WRITINGDocument6 pagesĐỀ TEST CỦA BI READING & WRITINGMai Huong NguyenNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Franklin Autobiography Part IDocument5 pagesBenjamin Franklin Autobiography Part ILucía Olmo de la TorreNo ratings yet

- JabberwockyDocument2 pagesJabberwockyapi-241172875No ratings yet