Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part3

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part3

Uploaded by

DCOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part3

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part3

Uploaded by

DCCopyright:

Available Formats

Practical guide on admissibility criteria

Parliament of an autonomous community. In such a case, the rights and freedoms invoked by the

applicants concern them individually and are not attributable to the Parliament as an institution

(Forcadell i Lluis and Others v. Spain (dec.)).

3. Victim status

17. The Court has consistently held that the Convention does not provide for the institution of an

actio popularis and that its task is not normally to review the relevant law and practice in abstracto,

but to determine whether the manner in which they were applied to or affected the applicant gave

rise to a violation of the Convention (for example, Roman Zakharov v. Russia [GC], § 164).

a. Notion of “victim”

18. The word “victim”, in the context of Article 34 of the Convention, denotes the person or persons

directly or indirectly affected by the alleged violation. Hence, Article 34 concerns not just the direct

victim or victims of the alleged violation, but also any indirect victims to whom the violation would

cause harm or who would have a valid and personal interest in seeing it brought to an end

(Vallianatos and Others v. Greece [GC], § 47). The notion of “victim” is interpreted autonomously

and irrespective of domestic rules such as those concerning interest in or capacity to take action

(Gorraiz Lizarraga and Others v. Spain, § 35), even though the Court should have regard to the fact

that an applicant was a party to the domestic proceedings (Aksu v. Turkey [GC], § 52; Micallef

v. Malta [GC], § 48; Bursa Barosu Başkanliği and Others v. Turkey, §§ 109-117). It does not imply the

existence of prejudice (Brumărescu v. Romania [GC], § 50), and an act that has only temporary legal

effects may suffice (Monnat v. Switzerland, § 33).

19. The interpretation of the term “victim” is liable to evolve in the light of conditions in

contemporary society and it must be applied without excessive formalism (ibid., §§ 30-33; Gorraiz

Lizarraga and Others v. Spain, § 38; Stukus and Others v. Poland, § 35; Ziętal v. Poland, §§ 54-59).

The Court has held that the issue of victim status may be linked to the merits of the case (Siliadin

v. France, § 63; Hirsi Jamaa and Others v. Italy [GC], § 111). The Court can examine the question of

victim status and locus standi ex officio, since it concerns a matter which goes to the Court’s

jurisdiction (Buzadji v. the Republic of Moldova [GC], § 70; Satakunnan Markkinapörssi Oy and

Satamedia Oy v. Finland [GC], § 93; Unifaun Theatre Productions Limited and Others v. Malta,

§§ 63-66; Jakovljević v. Serbia (dec.), § 29).

20. The distribution of the burden of proof is intrinsically linked to the specificity of the facts, the

nature of the allegation made and the Convention right at stake (N.D. and N.T. v. Spain [GC], §§ 83-

88).

b. Direct victim

21. In order to be able to lodge an application in accordance with Article 34, an applicant must be

able to show that he or she was “directly affected” by the measure complained of (Tănase

v. Moldova [GC], § 104; Burden v. the United Kingdom [GC], § 33; Lambert and Others v. France [GC],

§ 89). This is indispensable for putting the protection mechanism of the Convention into motion

(Hristozov and Others v. Bulgaria, § 73), although this criterion is not to be applied in a rigid,

mechanical and inflexible way throughout the proceedings (Micallef v. Malta [GC], § 45; Karner

v. Austria, § 25; Aksu v. Turkey [GC], § 51). For instance, a person cannot complain of a violation of

his or her rights in proceedings to which he or she was not a party (Centro Europa 7 S.r.l. and Di

Stefano v. Italy [GC], § 92). However, in Margulev v. Russia, the Court considered the applicant to be

a direct victim of defamation proceedings although he was only admitted as a third party to the

proceedings. Since domestic law granted the status of third party to proceedings where “the

judgment may affect the third party’s rights and obligations vis-à-vis the claimant or defendant”, the

Court considered that the domestic courts had tacitly accepted that the applicant’s rights might have

European Court of Human Rights 11/110 Last update: 31.08.2022

Practical guide on admissibility criteria

been affected by the outcome of the defamation proceedings (§ 36). In Mukhin v. Russia, the Court

recognised that the editor-in-chief of a newspaper could claim to be a victim of the domestic courts’

decisions divesting that newspaper of its media-outlet status and annulling the document certifying

its registration (§§ 158-160). Further, in some specific circumstances, direct victims who had not

participated in the domestic proceedings were accepted as applicants before the Court (Beizaras and

Levickas v. Lithuania, §§ 78-81). Standing in domestic proceedings is therefore not decisive, as the

notion of “victim” is interpreted autonomously in the Convention system (see, for instance,

Kalfagiannis and Pospert v. Greece (dec.), §§ 44-48, concerning the financial administrator of a

public service broadcaster whose victim status was accepted by the domestic courts but not by the

Court).

22. Moreover, in accordance with the Court’s practice and with Article 34 of the Convention,

applications can only be lodged by, or in the name of, individuals who are alive (Centre for Legal

Resources on behalf of Valentin Câmpeanu v. Romania [GC], § 96). However, particular

considerations may arise in the case of victims of alleged breaches of Articles 2, 3 and 8 at the hands

of the national authorities. Applications lodged by individuals or associations on behalf of the

victim(s), even though no valid form of authority was presented, have thus been declared admissible

(§§ 103-114).3

c. Indirect victim

23. If the alleged victim of a violation has died before the introduction of the application, it may be

possible for the person with the requisite legal interest as next-of-kin to introduce an application

raising complaints related to the death or disappearance of his or her relative (Varnava and Others

v. Turkey [GC], § 112). This is because of the particular situation governed by the nature of the

violation alleged and considerations of the effective implementation of one of the most fundamental

provisions in the Convention system (Fairfield v. the United Kingdom (dec.)).

24. In such cases, the Court has accepted that close family members, such as parents, of a person

whose death or disappearance is alleged to engage the responsibility of the State can themselves

claim to be indirect victims of the alleged violation of Article 2, the question of whether they were

legal heirs of the deceased not being relevant (Van Colle v. the United Kingdom, § 86; Tsalikidis and

Others v. Greece, § 64; Kotilainen and Others v. Finland, §§ 51-52).

25. The next-of-kin can also bring other complaints, such as under Articles 3 and 5 of the Convention

on behalf of deceased or disappeared relatives, provided that the alleged violation is closely linked

to the death or disappearance giving rise to issues under Article 2. For example, see Khayrullina

v. Russia, §§ 91-92 and §§ 100-107, regarding the next-of-kin’s standing to lodge a complaint under

Article 5 § 1 and Article 5 § 5. The same logic could be applied to a complaint under Article 6 if a

person had died during the criminal proceedings against him or her and if the death had occurred in

circumstances engaging the State’s responsibility (Magnitskiy and Others v. Russia, §§ 278-279).

26. For married partners, see McCann and Others v. the United Kingdom, Salman v. Turkey [GC]; for

unmarried partners, see Velikova v. Bulgaria (dec.); for parents, see Ramsahai and Others v. the

Netherlands [GC], Giuliani and Gaggio v. Italy [GC]; for siblings, see Andronicou and Constantinou

v. Cyprus; for children, see McKerr v. the United Kingdom; for nephews, see Yaşa v. Turkey;

conversely, for a divorced partner who was not considered to have a sufficient link to her deceased

ex-husband, see Trivkanović v. Croatia, §§ 49-50; for an uncle and a first cousin, see Fabris and

Parziale v. Italy, §§ 37-41 and the recapitulation of the case-law. With regard to missing persons

whose bodies have not been found following a boat accident, the Court has accepted that the next-

of-kin can lodge an application under Article 2, in particular where the State has not found all the

3. See section Representation.

European Court of Human Rights 12/110 Last update: 31.08.2022

You might also like

- Affidavit of Two Disinterested Persons - MarriageDocument1 pageAffidavit of Two Disinterested Persons - MarriageJennifer Tinagan83% (6)

- Mavrommatis CaseDocument3 pagesMavrommatis CaseClarisseOsteria100% (2)

- Submitted To: Sir Imran Asghar Submitted By: Waqas Saeed Roll No: B-21730 (Section A) Subject: International Law Topic: TreatiesDocument5 pagesSubmitted To: Sir Imran Asghar Submitted By: Waqas Saeed Roll No: B-21730 (Section A) Subject: International Law Topic: TreatiesSeemab MalikNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part4Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part4DCNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part7Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part7DCNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part8Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part8DCNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part10Document1 pageAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part10DCNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part12Document1 pageAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part12DCNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part11Document1 pageAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part11DCNo ratings yet

- (04b) The Varvarin Case - Excerpts of The Judgment of The Civil Court of Bonn of 10 December 2003, Case No. 1 O 361 02Document4 pages(04b) The Varvarin Case - Excerpts of The Judgment of The Civil Court of Bonn of 10 December 2003, Case No. 1 O 361 02beserious928No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Moduel AnswerDocument3 pagesAssignment 1 Moduel AnswerMariam amirNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part13Document1 pageAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part13DCNo ratings yet

- Legal System and Method Casenote (UofL 2019)Document3 pagesLegal System and Method Casenote (UofL 2019)Izmail PirzadaNo ratings yet

- Revisiting-Order 22Document10 pagesRevisiting-Order 22Alextro MaxonNo ratings yet

- Death of Party in Civil CaseDocument3 pagesDeath of Party in Civil CaseRosanna Beceira-Coloso Y MugotNo ratings yet

- Very Imp. For Tomorrowland.: No Violation of Pace Futura I. Rules of Release: Article 60 of The Vienna ConventionDocument4 pagesVery Imp. For Tomorrowland.: No Violation of Pace Futura I. Rules of Release: Article 60 of The Vienna ConventionShourya SarinNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Essay - Main BodyDocument9 pagesHuman Rights Essay - Main BodyNiyree81No ratings yet

- Rough Memo Special IntraDocument8 pagesRough Memo Special IntraDivya RaunakNo ratings yet

- Nicaragua V USDocument14 pagesNicaragua V USAnonymous KZEIDzYrONo ratings yet

- Erga OmnesDocument2 pagesErga OmnesLamar LakersInsider BryantNo ratings yet

- Materials IVDocument9 pagesMaterials IVJoão PraçaNo ratings yet

- State V Mohit I 2015 SCJDocument17 pagesState V Mohit I 2015 SCJHemant HurlollNo ratings yet

- Not Iss1 ApplicaDocument4 pagesNot Iss1 ApplicaMulugeta BarisoNo ratings yet

- 8 A. ECHR Saadi2008Document9 pages8 A. ECHR Saadi2008Assassin GamingNo ratings yet

- Conaglen - Contests Between Rival Trust BeneficiariesDocument57 pagesConaglen - Contests Between Rival Trust BeneficiariesTom DohertyNo ratings yet

- Dip Pro 2Document30 pagesDip Pro 2Juned AkhterNo ratings yet

- Treaty Mechanism and Procedures: 1. Individual CommunicationsDocument6 pagesTreaty Mechanism and Procedures: 1. Individual CommunicationsSharmaine It-itNo ratings yet

- Torts DoctrinesDocument7 pagesTorts DoctrinesAdi AumentadoNo ratings yet

- Five ICCPR Cases - SummaryDocument11 pagesFive ICCPR Cases - Summarywilfred poliquit alfecheNo ratings yet

- The Rights of Access To Justice Under Customary International LawDocument56 pagesThe Rights of Access To Justice Under Customary International LawJuan L. LagosNo ratings yet

- Trabalho DidhDocument6 pagesTrabalho DidhAirton DuarteNo ratings yet

- Zoeteweij-Turhan - State Jurisdiction and The Scope of The ECHR's Protection (Article 1 ECHR)Document15 pagesZoeteweij-Turhan - State Jurisdiction and The Scope of The ECHR's Protection (Article 1 ECHR)Leontien SchoenmakerNo ratings yet

- Osman V United Kingdom (2345294)Document61 pagesOsman V United Kingdom (2345294)Heronna WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Violation of TreatyDocument21 pagesViolation of TreatydevytaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Discussion QuestionsDocument4 pagesChapter 3 Discussion Questionslexyjay1980No ratings yet

- Against Unreasonable Searches and SeizuresDocument10 pagesAgainst Unreasonable Searches and SeizuresAliyah SandersNo ratings yet

- AdmisitltyDocument6 pagesAdmisitltynasraidah454No ratings yet

- Book Edcoll 9789004298712 B9789004298712-S004-PreviewDocument2 pagesBook Edcoll 9789004298712 B9789004298712-S004-PreviewhanwinNo ratings yet

- Research Report Safe Third Country ENGDocument21 pagesResearch Report Safe Third Country ENGeeeNo ratings yet

- Equal ProtectionDocument6 pagesEqual ProtectionRose AnnNo ratings yet

- Erga OmnesDocument5 pagesErga OmnesTrexPutiNo ratings yet

- The Courts and The COVID-19Document6 pagesThe Courts and The COVID-19Tuguldur EnkhboldNo ratings yet

- 5nov KURT V TurkeyDocument57 pages5nov KURT V Turkeyneil peirceNo ratings yet

- Al-Adsani v. The United Kingdom (GC)Document3 pagesAl-Adsani v. The United Kingdom (GC)DenisaNo ratings yet

- Jus Cogens and Erga OmnesDocument41 pagesJus Cogens and Erga OmnesDanny QuioyoNo ratings yet

- Urbaser V Argentine RepublicDocument30 pagesUrbaser V Argentine RepublicShirat MohsinNo ratings yet

- The Principle of State LiabilityDocument2 pagesThe Principle of State LiabilitygayathiremathibalanNo ratings yet

- Hrdp-State V Makwanyane (1995)Document3 pagesHrdp-State V Makwanyane (1995)Robert Walusimbi100% (1)

- Flores v. Mallare-PhillippsDocument6 pagesFlores v. Mallare-PhillippsGelo AngNo ratings yet

- The Kadi Case: What Relationship Is There Between The Universal Legal Order Under The Auspices of The United Nations and The EU Legal Order?Document11 pagesThe Kadi Case: What Relationship Is There Between The Universal Legal Order Under The Auspices of The United Nations and The EU Legal Order?shahab88No ratings yet

- The Clean Hands Doctrine in International LawDocument33 pagesThe Clean Hands Doctrine in International LawPatricia BenildaNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet Article 3 ECHR. UNHCR Manual On Refugee Protection and The ECHR.Document52 pagesFact Sheet Article 3 ECHR. UNHCR Manual On Refugee Protection and The ECHR.Sara Taira HuierNo ratings yet

- 2052 Article p372Document14 pages2052 Article p372Anas ArifynNo ratings yet

- CASE OF BÍRÓ AND OTHERS v. UKRAINEDocument8 pagesCASE OF BÍRÓ AND OTHERS v. UKRAINEJHON EDWIN JAIME PAUCARNo ratings yet

- Case Notes: and Human Dignity's Role in Article 3 EchrDocument20 pagesCase Notes: and Human Dignity's Role in Article 3 EchrEseosa EnorenseegheNo ratings yet

- Uganda Martyrs UniversityDocument17 pagesUganda Martyrs UniversityOnoke John ValentineNo ratings yet

- Sources of LawDocument44 pagesSources of LawrokeahmedNo ratings yet

- CASE OF TURGAY AND OTHERS v. TURKEY (No. 4)Document10 pagesCASE OF TURGAY AND OTHERS v. TURKEY (No. 4)Deepanksha WadhwaNo ratings yet

- EPIL Treaties Multilateral Reservations ToDocument14 pagesEPIL Treaties Multilateral Reservations ToAnonymous007No ratings yet

- Third Geneva Convention: Prisoners of War, Rules, Rights, and RealitiesFrom EverandThird Geneva Convention: Prisoners of War, Rules, Rights, and RealitiesNo ratings yet

- Subscription Voucher: Doc Type Sub Type Number DateDocument2 pagesSubscription Voucher: Doc Type Sub Type Number Dateadarsh trivediNo ratings yet

- Sample CRPC Constitution of Criminal CourtsDocument9 pagesSample CRPC Constitution of Criminal CourtsKhan OvaiceNo ratings yet

- EU Approval ProcessDocument2 pagesEU Approval ProcessJaker SauravNo ratings yet

- Chanakya National Law University, PatnaDocument9 pagesChanakya National Law University, Patnamihir khannaNo ratings yet

- (Triplicate For Supplier) : Sl. No Description Unit Price Qty Net Amount Tax Rate Tax Type Tax Amount Total AmountDocument1 page(Triplicate For Supplier) : Sl. No Description Unit Price Qty Net Amount Tax Rate Tax Type Tax Amount Total AmountSreedharNo ratings yet

- Memo On Tree PlantingDocument6 pagesMemo On Tree Plantingjojo zamNo ratings yet

- Ghauker Khandsari Sugar Mills VDocument5 pagesGhauker Khandsari Sugar Mills VHarsh GargNo ratings yet

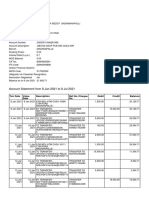

- Account Statement From 8 Jan 2021 To 8 Jul 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument16 pagesAccount Statement From 8 Jan 2021 To 8 Jul 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceMUTHYALA NEERAJANo ratings yet

- How To Live Without Social Security NumberDocument227 pagesHow To Live Without Social Security NumberCarol0% (1)

- Declaration of TrustDocument39 pagesDeclaration of TrustIvory RosewoodNo ratings yet

- CFP Risk Analysis and Insurance Planning Practice Book SampleDocument34 pagesCFP Risk Analysis and Insurance Planning Practice Book SampleMeenakshi100% (7)

- Work Terms and ConditionsDocument3 pagesWork Terms and ConditionsYubaraj AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Labor and Social Legislation I - 26 October 2020 - Atty. Jerwin LimDocument6 pagesLabor and Social Legislation I - 26 October 2020 - Atty. Jerwin LimAndrei Da JoseNo ratings yet

- Leave Application FormDocument2 pagesLeave Application FormAftab AlamNo ratings yet

- 4 (A) Declaration (In Case of Assignment)Document1 page4 (A) Declaration (In Case of Assignment)sajeer n FORWARDNo ratings yet

- The Role of TreatiesDocument5 pagesThe Role of TreatiesGizelle DeffanyNo ratings yet

- Top 3 Smart Townships: Cedar & DeodarDocument15 pagesTop 3 Smart Townships: Cedar & DeodarYogeshNo ratings yet

- OSHA Decision in Metro-North Whistleblower CaseDocument12 pagesOSHA Decision in Metro-North Whistleblower CaseestannardNo ratings yet

- Reyes v. Bagatsing, GR No. L-65366Document1 pageReyes v. Bagatsing, GR No. L-65366Melvin John RegisNo ratings yet

- Sr. No Manager Rera No TL Name CP Firm NameDocument5 pagesSr. No Manager Rera No TL Name CP Firm Namedarshan shettyNo ratings yet

- PBD Motorcycle Patrol Vehicle - April 25 2018Document94 pagesPBD Motorcycle Patrol Vehicle - April 25 2018jomarNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Maria Lourdes P.A. Sereno G.R. No. 237428 June 19 2018Document4 pagesRepublic of The Philippines vs. Maria Lourdes P.A. Sereno G.R. No. 237428 June 19 2018Arianne AstilleroNo ratings yet

- Spouses Barraza v. CamposDocument1 pageSpouses Barraza v. CamposAbegail GaledoNo ratings yet

- Jipr 10 (6) 480-490Document11 pagesJipr 10 (6) 480-490Karthik SNo ratings yet

- Sponsorship Certificate: (To Be Filled in Duplicate by The Indian Referee of PN)Document2 pagesSponsorship Certificate: (To Be Filled in Duplicate by The Indian Referee of PN)Pa YalNo ratings yet

- Role of Media in Democracy and Good GovernanceDocument12 pagesRole of Media in Democracy and Good GovernanceFareed IjazNo ratings yet

- Indemnity CaseDocument16 pagesIndemnity CaseArima KNo ratings yet

- Attestation ProjectDocument15 pagesAttestation ProjectVidhi GoyalNo ratings yet

- Extra-Judicial Settlement CaselesDocument6 pagesExtra-Judicial Settlement CaselesRoy PersonalNo ratings yet