Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adaptación Ocupacional. Ingles

Uploaded by

Terapia OcupacionalCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adaptación Ocupacional. Ingles

Uploaded by

Terapia OcupacionalCopyright:

Available Formats

Occupational

T

hiS paper presents the implications for practice of

the theoretical concepts discussed in "Occupation-

Adaptation: Toward a al Adaptation: Toward a Holistic Approach for Con-

temporary Practice, Part 1" (Schkade & Schultz, 1992).

Holistic Approach for The present paper discusses the occupational adaptation

construct presented in Part 1 and illustrates how that

Contemporary Practice, construct becomes operationalizecl in therapy, Although

the occupational therapy literature contains many refer-

Part 2 ences that discuss the relationship between occupation

and adaptation (Breines, 1986; Clark, 1979; Fidler, 1981;

Fidler & Fidler, 1978; Fine, 1990; Gilfoyle, Grady, &

Moore, 1990; Kielhofner, 1985; King, 1978; KJeinman &

Sally Schultz, Janette K. Schkade Bulkley, 1982; Lindquist, Mack, & Parham, 1982; Llorens,

1984,1990; Mosey, 1968; Nelson, 1988; Reed, 1984; Reilly,

1962; Yerxa, 1967, 1989), this paper proposes treatment

Key Words: environment. process, that is based, not on a relationshifl between occupation

occupational therapy and adaptation, but on occupational adaptation, a sin-

gle internal phenomenon within the patient (Schkade &

Schultz, 1992). Parts 1 and 2 are offered to enhance the

unclero,tanuing of occupational therapy as a vital

This paper introduces a practice model based on the intervention.

occupational adaptation frame of reference (Schkade The proposed practice model is based on the occu-

& Schultz, 1992) The occupational adaptation prac-

pational adaptation construct. This normative construct,

tice model emphasizes the creation of a therapeutic

which is conceptualized as both a state ami a rrocess, was

climate, the use of occupational acti/'ity. and the im-

portance of relatiue mastery. Practice hased on occu- discussed in Pan 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992). The pres-

pational adaptation differs ji~om treatment that focus- ent papel' Focuses on interventions based on this con-

es on acqu.isition o/jimctional skills hecause the struct with its associated concepts ami assumptions. Oc-

practice model directs occupational therapy interven- cupational adaptation treatment is directed at improving

tions toward the patient's internal processes and how the patient's occupational adaptation process, a norma-

such processes arefacilitated to improue occupational tive process that is used throughout tbe life span as the

functioning The occupational adaptation practice pel'son faces occupational challenges. Numerous events

model is holistic. The patient's occupational environ- ancl conditions, such as traumatic injurv, chronic illness,

ments (as influenced hy physical, social, and cultural phvsical abuse, congenital anomailes, chemical depend-

properties) are as important as the patienl's sensori- ency, and mental iJlness, can greatlv impail' the patient's

motor, cognitive, and psvchosocial/iAnclioning and

occupational adaptation process. Traditional approaches

the patient's experience of personal limitations and

potenlial is oatidaled The integration of these con- in occupational thet'apv have Focused treatment on im-

cepts drives the treatment process. Through a descrip- proving the patient's sensorimotor, cognitive, and psy-

tion of Irealment with a varlet)' ofpalienls Ihis paper chosocial systems, which together compose the patient's

presents Ihe model's diversit1' and illustrates the rela- person svstem. The occupational adaptation practice

lionshlp helween the concepts. The occupational ad- model leads the therapist into a new layer of intervention,

aptation praclice model reflecls the uniqueness of oc- that is, treatment directecl at affecting the patient's inter-

cupational therapy and integrates the profession's nal abiJitv to generate, evaluate, and integrate aclaptive

hislorical practice wilh contemporarl' interventions responses in which relative mastel)' is exrerienced. Al-

and methods. though the importance of improvement in the person

svstem is a given, we suggest that the most beneficial

effect of occupational therapv mav occur wben the occu-

pational therapist focuses on the intel'l1al workings of the

patient's occupational adaptation process, because that

proceso, lealls to the patient'S abilitv to adapt and to ap-

Sally Schultz. PhD. aiR is Associate Professor. School of Occu-

pational Therapv, Texas Woman's Universir\, PO Box 2.3718, rroach each occup3tional challenge with greater success

Demon, Texas 76204. and sa tis f~lction.

Manv occupational therapists have shifted their ori-

]anerre K Schkade, rhD om. is Associate Professor, School of

entation awav From phenomenological processes to Focus

Occuparional Therapy, Texas Wmnan's (Jniversitv, Dallas,

on functional perfonnance that can be measured more

TeX3~.

objectively (Mattinglv, 1991). The current demand Fur

This article Leas accepted},,!' publicalion ,11m' ff. J')').l

therapists to hase occupational thel'apv on acquisition of

The American journal of Occupational Thempl' 917

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

functional skills illustrates this trend. We believe, howev- man beings have an occupational nature anc! can influ-

er, that a focus on the patient's functional skills may ence their health through occupation; (b) human de-

actuallv limit the colltribution of occupational therapy velopment is a continuous process of adaptation; (c)

and mav deny patients the opportunity to make vital biologicaL sociologicaL and psychological factors may

changes in their occupational aclaptation process until interrupt and impair the adaptation process at any

they arc discharged from the treatment setting. At home, point in the life cycle; and (d) appropriate occupation

fonner patients often discard techniques and assistive can facilitate the adartive process (American Occupa-

devices that they have received and design more efficient tional Therapy Association /AOTAJ, 1979; Meyer, 1922;

or effective methods for meeting their needs and going West, 1989). Occupational adaptation practice focuses

about their activities with greater satisfaction. The pa- on identifying and treating impairment or interference

tient's resulting occupational adaptation may bear little in the patient's occupational adaptation process. The

resemblance to the occupational therapy that was following discussion identifies the conditions and pa-

received. rameters of practice that is based on the occupational

The Occupational Adaptation Practice Model does adaptation frame of reference cJiscussed in Part 1

not disregard the necessity of functional skills. However, (Schkade & Schultz, 1992).

in this modeJ, the occupational adaptation process has a

more direct link to futme occupational functioning than

Facilitating the Therapeutic Climate

does the acquisition of specific functional skills. There-

fore, the model focuses primarily on the patient's internal Through exchange of knowledge, exrerience, ahility,

rrocess of occurational adaptation. Because the present analysis of motivation, and shared vision, the therapeutic

paper incorporates the assumptions and terminology in- climate is created. Practice based on this frame of refer-

troduced in Part 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992), a review of ence (Schkade & Schultz, 1992) requires the therapist to

that paper will be necessary for complete understanding establish a close therapeutic relationship with the patient

of the perspectives rresented in the present paper. Addi- (Fidler & Fidler, 1963; Peloquin, 1990). The treatment

tionally, four concepts that are required to apply the con- process is an ongoing collaboration with mutual identifi-

cepts introduced in Part 1 must be defined: occupational cation of goals between therapist and patient. It depends

activities, occupational readiness, occupations of daily liv- on an exchange of "needs, visions, and expectations" (Pe-

ing, and therapeutic climate. loquin, 1990, p. 13). Such an exchange is made rossible

Occupational activities are discrete activities that through the roles of agency that are assumed by the

are occupational (i.e., active, meaningful, and process- patient ancJ the occupational therapist. The role of the

oriented with a tangihle or intangible product) and are patient is to function as his or her own agent. The role of

incorporated into treatment because they can promote the therapist is to function as the agent of the patient's

the occupational adaptation process. Occupational occupational environment. This approach directs the

readiness includes skill-based activities and other such therapist to base treatment on the patient's occupational

interventions that focus on change in the person systems environments and the associated expectations of occupa-

in rreparation for occupational activities (e.g., the use of tional performance. Treatment guided by mutual agency

preparatory techniques, instruction, or assistive devices may free each party to act in a way that empowers both to

necessary for the patient to engage in occupational activ- make optimal contributions to the treatment rrocess.

ity). Occupations o/dailv living are the unique patterns Aspects of the therapeutic climate will change over

of occupations in which the person regularly engages as a time. In the initial stages of therapy, the therapist's role is

result of the interaction between his or her occupational greater than the patient's, but as therapy progresses, the

environments and related occupational roles. Thaapeu- patient's role becomes greater. Although the therapist is

tic climate is the product of an interdependent exchange the primary catalyst in this evolutional)l rrocess, the con-

wherein the therapist, as the primary facilitator, functions cept of agency empowers each party to assume a unique

as the agent of the patient's occupational environment and vital role. As the therapist fulfills the identified role

and the patient functions as the agent of his or her unique and function, therapeutic use of self may become the

person systems. The climate defines the role of each most important element in both the process and out-

party, the goal of therapy, and the expected outcome; come of therarY.

both parties are empowered to make their optimal The overarching goal of therapy is improvement in

contribu tion. the patient's internal occupational adaptation process

(Schkacle & Schultz, 1992). To meet this goal, the therapy

program must be directly related to the patient's occupa-

Occupational Adaptation: A Practice Model

tions of daily living.

The Occurational Adaptation Practice Model is hased on Assumption: For maximal effect on occupational

the same essential beliefs stated by the founders and adaptation, the activities, tasks, methods, and tech-

leaders of the occupational therapy profession: (3) hu- niques o/intervention must be centered 011 occupation-

918 Oclober 1992, votume 46, Number 10

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

al activi~y that promotes satisfaction for the patient and guide matches our understanding of the occupational

socie~y. adaptation process and how that process may be affected

by therapeutic intervention. The format of the guide pro-

vides the therapist with a sequence of questions to he

Perspective on iv/otivation

asked, rather than an identification of specific treatment

The therapist incorporates all sources of motivation, such methods or techniques. The intent of this format is to free

as the patient's desires, potential, limitations, and societal the therapist to address the uniqueness of each patient

expectations, to facilitate the therapeutic climate. The and each treatment setting. Specific interventions will

experience of mastery is accepted as a major component vary greatly. It is hoped that therarists will find the prac-

of motivation. In this practice model, mastery is concep- tice guide useful in the development of porularion-

tualized as a relative phenomenon rather than an ahso- specific practice models. The occupational adartation

lute condition; therefore, the term relative mastery is practice guide has three main parts: data gathering and

used. Relative mastery is incorporated in occupational :.lssessment, programming, and evaluation. The follOWing

adaptation practice as a patient-centered concept be- discussion provides further explanation of the practice

cause it measures performance from the patient's orien- guide and an example of each pan of the guide

tation. This perspective is based on the beliefs that each

person is endowed with a desire for mastery, that the

occupational environment also has a demand for mastery, Occupational Adaptation Data Galhering and

and that together these internal and external motivational Assessmenl

forces provide an interactive press for mastery (Schkade

& Schultz, 1992) An occupational adaptation assessment is conducted in

Assumptions' (a) Change in the occupational ad the follOWing sequence. Fir,st, information is collected

aptation process occurs as a result ofboth internal and about the patient's occurational environments ami the

external sources o{motivarion that interact to prompt a resreetive occupational role expectations (pa,st, present.

strivingfor mastery. (h) Masterv is more than the abitit)' and future). Next, the effect of the pre,,,enting problem

to perform a discrete task; it is a reflection of the pa- (eg" illness, condition, behavior) on the patient's person

tient's experience as an occupational bein{', (c) Relatiue systems (i.e., sensorimotor, cognitive, ami psychosocial

mastery has three major properties: eUiciency. ef{ectii'e- functioning) is cV:.lluatcd. Traditional occupational ther-

ness, and scttis{action to sel{and others. These properties apy tests and instruments are used as indicated, On the

are operative explanations o{ the interaetiue inf7uence basis of the accumulated information, [he patient and [he

of internal and e.xternal motivat ion therapist determine the relative match between the [1a-

The occupational adaptation practice model is orga- tient's current occupational functioning ami the role ex-

nized around a set of concepts and assumptions that add pectations of the occupational environments, Last, the

a unique perspective to the current body of knowkdge thel'a[1ist estimates the patient's present potential for oc-

on the efficacy of occupational therapv. The follov,,Iing cupational adaptation and how this potential can he facili-

statements summarize this perspective. First, the pa- tated over the course of occupational therapy interven-

tient's level of relative mastery is c!irectly rdated to the tion, Identifying the sources of dysfunction in the

degree that the internal occupational adaptation process components of the occupational adaptation process and

is activated and affected hy therapy. Second, a change in their effect on relative mastery is an underlying theme of

the patient's occupational adaptation process is more occupational adaptation practice. Such identification en

predictive of future occupational functioning than is the ables the therapist to clarify the points in the patient's

patient's ahility to perform discrete function:.ll tasks. occupational adaptation process where intervention will

Third, the patient's internal occupational adaptation he mos[ effective. During the initial [1hase of thera[1Y, the

process is the optimal pathway for occupational therapv therapist's essential task is to transform [he patient's as-

to affect occupational functioning. The assumptions of sessment into an occupational adaptation treatment pro-

the Occupational Adaptation Practice Model are consid- gt-am that reflects [he pa[ient as an occupational being.

ered to be universal regardless of age, race, culture, gen- The following t'xam[1le demonstrates responses for pa-

der, condition, or other classifications. tients with similar person systems hut different occupa-

tional roles,

'1\~'O patients complain of pain, edema, and limited range of mo-

Occupational Adaptation Practice Guide lion due to traumatic tcn(]o'l and l1l'n'(' dal1lage in their clominanl

hands. For Patient A, the mother of four ,'oung chiklrel', the

The systematic guide for applying the occupational adap- greatest concern might he rerforming rhe occupation, of preIJal'-

tation concepts and assumptions to a variety of settings ing meah, doing laumlr\', ami ba[hlng hn children. Assessment of

and populations (see the Appendix) is hased on the nor- rhe person .'I's[eI11S rc\'eals sensorimOlor dcfiuts in rangc of mo-

tiOIl. "rrcngth. scn:.. allon, and dL'xtcrity: Ill) (oglllIi\'c Impairment;

mative construct of occupational adaptation presented in ami ps,·chosocial 3nxlct,' abou[ abilil'· to earn' out hn occurati(lI1-

Part 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992). The flow of the practice al role. The primary treatment focw. would become het' work

The American .Jou171Cl1 uf' Occupatiunal Therapl' 919

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

environment Jnd the role of mother. In conrrast, Patient 13', great- increased In this more challenging occupational environ-

e,1 concC!'n might he relurning 10 her occupation :lS a .secretaJ"\'.

The per.son "',Iem assessrnent i, com par'ahle to that of Pal ienr A.

ment. the opportunity for experiencing relative mastery is

Although hOlh p~tients pre,ent ",ith simibritie, in thc stalUS of enhanced. and motivation is therefore increased,

their person svstern,. there ;lrc' suhswnrial differenccs in their For Parient B, occupational readiness would also fo-

(JCCllp~lional erwir'onrncnts (\\ork) ,md [he rchHi\'c role

cxpel'lalions.

CUS on addressing edema, range of motion, dexterity, and

sensory loss. However, the specific form would be rel-

evant to the type of secretarial work performed hy the

patient. Occupational activities for this patient may range

Occupational Adaptation Programming

from putting a floppy disk into a computer to completing

The occupational adaptation assessment is used to de- segments of real work brought from her office. A~ with

sign an intervention program focused on helping the pa- Patient A, occupational activity enhances the opportu-

tient achieve the highest level of internal occupational nity for experiencing relative mastery and increasing

adaptation. The program is designed to improve the oc- motivation.

cupational adaptation process to help the patient narrow Throughout the course of therapy, the therapist

the gap between present occupational functioning and must continually critique the therapy program to ensure

the role performance required hy both the patient and that its design offers the patient the optimal opportunity

the occupational environments. A5 the gap narrows, it is to improve the occupational adaptation process, Changes

expected that the patient's experience of relative mastery in relative mastery indicate that the therapy program is

will improve. All therapy activities and methods should be appropriately designed.

consonant with these two effects, On the basis of a thor- Assumption: Although the patient may be improv-

ough review of the occupational adaptation assessment ing inJunctional skills, change in occupational adapta-

and patient and family collaboration, a primary occupa- tion mc~v not be OCCUlTing An increase in relatiue mas-

tional environment is selected and the expected role per- ter)' is the best indicator that change in the occupational

formance within that occupational environment is identi- adaptation process is taking place.

fied as the primary treatment focus.

The resulting treatment program for Patients A and B

would vary hecause the primary treatment focus is differ-

FlJClluctiion 0/ the Occupational Adaptation Process

ent for each, The activities and associated tasks planned

by the patient and therapist would give the patient the In the Occupational Adaptation Practice Model, treat-

maximum opportunity to improve her internal occupa- ment effectiveness uepends on a view of the patient as a

tional adaptation process relative to the primary treat- whole person with a unique occupational nature. For

ment focus. example, even though the chief complaint may be phys-

Improvement in the patient's occupational adapta- ical, other aspects of the patient's occupational environ-

tion process is accomplished through a therapy program ments and relative roles may affect treatment outcome

that includes both occupational readiness and occupa- more than physiological deficits. Consequently, the

tional activitv. It is expected that both aspects of treat- therapist should consiuer the patient as a whole occupa-

ment would be indicated for most patients. Examples of tional system when documenting progress. In addition to

occupational readiness are progressive resistive exercise, reporting traditional measures of patient improvement,

assertiveness training, social skill development, and pas- such as level of functional independence, the therapist

sive or active range of motion. Occupational activities should note the patient's change in occupational adapta-

allow the patient and the therapist to put into meaningful tion hy documenting the patient's energy level, adaptive

action the benefit derived from occupational readiness. response mode, adaptive response behaVior, and result-

Both the occupational reauiness and the occupational ing reJative mastery (Schkade & Schultz, 1992) HolistiC

activities used in treatment must be directly related to the evaluation and documentation are essential for an undcr-

primary treatment focus. standing of the effect of programming on the patient's

For Patient A, the occupational readiness should fo- occupational adaptation process and potential for occu-

cus on addressing edema, range of motion, dexterity, and pational performance.

sensory loss relevant to meal preparation or other aplJro- Occupational adaptation is an internal phenomenon

priate role expectations. The therapist may use a variety and therefore seems to be less measurahle than ohserv-

of occu pational readiness techniques such as assistive able hehaviors that can be counted or functional skills

devices, alternarive methods, and a home exercise pro- that can he objectively measured. However, a systematic

gram. Occupational activities would be progressive, For approach hased on both observahle and phenomenologi-

example, therapy may be initiated with the patient pre- cal criteria could be generated to measure change in oc-

paring a simple lunch with the therapist and then may cuparional adaptation. We helieve that change in the oc-

progress to a real-life situation in which the children are cupational adaptation process is manifested by three

present and the demand for occupational ad8ptation is predictable outcomes: improvement in self-initiation,

920 Octuher 1992, Votume 46, Number 10

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

generalization, and relative mastely. Many practitioners telY can be translated into quantitative information, as is

have obselved these outcomes and have noted their posi- described below.

tive effect on the patient's empowerment. The three properties of relative mastery, as dis-

Assumption: As tbe internal occupational adapta- cussed in Pan 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992), arc efficiency,

lion process changes, thelol/owing outcomes result· (aJ effectiveness, and satisfaction to seJf and others. A proce-

the patient hegins to initiate changes in the wayoccupa- dure to measure change in relative mastery involves three

tional activities are approached; (b) the patient begins steps. First, the patient and the therapist select one or

to spontaneousl!' generalize knowledge and competen- more occupational activities for outcome measurement.

cies acquired in therapy to other occupational activi- The activity selected is drawn from those identified as

ties; and (c) the patient begins to experience gretlter part of the primary treatment focus during the initial

relative mastelY occupational adaptation assessment. The occupational

Periodic measurement of these outcomes may show activity selected to measure change in relative mastery

the changes that are occurring in the patient's occupa- must not be one in which the patient has had direct

tional adaptation process. Self-initiation and generaliza- training or experience in occupational therapy. A degree

tion may be readily measured hy frequency counts. How- of novelty in the occupational activity is necessary for the

ever, thc measurement of relative mastcn' requires a therapist to determine whether the associated outcomes

different approach, such as a framework that practition- of self·initiation and generalization are occurring. Second,

ers may use to measure relative mastcry as an outcome of the patient and the therapist detcrmine the criteria that

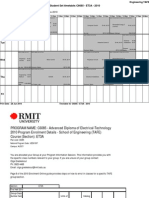

change in occupational aclapration (see FiguI'c 1). AJ- desnihe the levels of expected occupational performance

though it is a phenomenological cxperience, rdative mas- for each propenv of rdative masterv (i.e., what will (on-

Occupational Environment:

Occupational Role: _

Occupational Activity: _

Composite of

Efficiency: % Relative Mastery

... 90-:

3~ 80 --

Level of t

Occupational 2"":

Performance

1 .

0-

=====-=--

Outcome Measurement Inlervals

Effectiveness:

.5-.

50 -

14-

Level of

3J Level of

Occupational 12" Occupational 40 -

Performance Performance

1 ..

30--'

Outcome Measuremenllnlervals

Satisfaction: 20-

10 -

Level of

Occupallonal

Performance 0-

1-'

Outcome Measurement Intervals Outcome Measurement Intervals

Figure 1. Measurement of relative mastery.

TiJe AmericUI? journat or OccujJUlional '{hempy 921

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

stitutc the fivc levels of efficiency, effectiveness, and satis- qUired for a cornplete understanding. The treatment pre-

faerion). Third, the patient anc! therapist decide how of- sented in these examples is based on three factors: the

ten mcasurement lS to occur. After each measurement of normative construct of occupational adaptation dis-

relative masten', the patient anc! the therapist collaborate cussed in Parr 1, the conditions and parameters of occu-

[0 plm [he I·c.~ults The relative weigh[ of e3ch rropeny is pational adaptation practice discussed in the present pa-

determined by the patient. per, and the questions posed in the occupational

Assumption The patient will weight the three adaptation practice guide (see the Appendix).

elements of relative mastery according to personal

priorities.

£,ample 1: Outpatient Rehabilitation for Carpal

For example, a patient with many competing respon-

Tunnel Svndrome

sibilities may weight efficiency as the most important

property, whereas a patient with few demands on time For the patient in this example, occupational therapy was

may pJace more importancc on satisfaction. The patient initiated after surgery. As the patient began to experience

dctermines the relative weight of each property given the increased occupational functioning, the therapist trans-

selected occupational environment and relative role ex- ferred more and more of the responsibility for planning

pectations. One can calculate the compOSite measure of and managing the therapeutic outcome to the patient.

the patient's relative mastery by adding the ordinal data With the therapist's facilitation, the patient designed a

paints from each property and computing a composite home program that would incorporate essential move-

percentage for relative mastery. For example, if on the ment patterns and precautions into her occupations of

first occurrence of outcome measurement the patient daily living. This process increased the magnitude of the

ratcd efficiencv as 1, effectiveness as 2, and satisfaerion as patient'S agency and empowered the patient to make

4, the sum would be 7. One would compute a compOSite changes in her occupational adaptation process. The pri-

percentagc of relative mastery by dividing the calculated mary focus throughout treatment was on helping the

value into the highest possible total value (7 -:- 15 = patient experience greater relative mastery in her occupa-

47%) The percentage is then plotted (see Figure 1). A tional environment of work and role of mother. The pa-

comparison of the composite percentage on admission tient placed the most importance on the property of satis-

with the percentage at different points during therapy faction. As the patient began to change her approach to

proVides a measure of change in relative mastery over occupational challenges, such as doing the laundry, her

time Such comparison may be useful in determining overall relative mastery increased. She found that the

whether the patient is ready for discharge, reqUires con- splints recommended by the therapist helped her to

tinued inpatient treatment, or requires referral to outpa- maintain proper wrist position and enabled her to make

tient rehabilitation services. An analysis of performance necessary hand motions with less pain. However, al-

within each of the three properties of relative mastery though hcr efficiency and effectiveness were increasing,

may clarify where therapy should be concentrated for her satisfaction was not. In response, the therapist en-

greater effect on relatjve mastery and the overall occupa- couraged the patient to reassess her occupational role

tional adaptation process. A graphic rerxesentation of expectations. The patient revealed that before surgery,

outcome effect may provide the patient, the therapist, she had always taken great pride in methodically folding

family members, and concerned professionals with a visu- and putting away the laundry. She now realized that the

al record of therapeutic effect (see Figure 1). task took so much of her energy and ability that it gave

Two caveats should be kept in mind about this meth- her little satisfaction. She began to see folding laundry as

od of measuring relative mastery. First, the measurement an unnecessary task and a performance expectation that,

assumptions have not been fully tested. Second, a 5-point if eliminated, would allow her to focus on occupational

scale was used within each property of relative mastery to activities with greater potential for satisfaction. Her as-

suggest one approach to measurement. Different treat- sessment had a similar effect on the occupational role

ment settings or patient conditions may call for either a expectations relative to her occupational environment.

smaller or greelter number of levels. This decision is left to Family members began to verbalize their desire to do

the discretion of the therapist. Examples of program eval- tasks that would help prevent exacerbation of the pa-

uation can be found in the illustrations that follow. tient's carpal tunnel syndrome. The children changed

their expectations of their mother and began to help with

the laundry, although they had never done so before.

Illustrations of Occupational Adaptation Practice

Other tasks that were related to performance expecta-

The follOWing examples are excerpts from the course of tions were also modified by the patient. The patient's

therapy with four hypothctical patients. They are pro- change in occupational role expectations relative to her

vided to illustrate various aspects of practice applications occupational environment had a positive influence on the

based on the occupational adaptation frame of reference patient's satisfaction and her overall experience of rela-

Familiarity with Part 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992) is re- tive mastcry.

922 October 1992. Volume 46, Number 10

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

E.xample 2. Inpatient Rehabilitation for Traumatic gan to improve; efficiency was the biggest obstacle for the

Brain Injury patient. The therapist encouraged the use of the garden-

ing modality by other members of the treatment team.

The patient in this example had deficits in upper extrem-

Speech therarY began to focus on words associated with

ity movement and sensation in his dominant arm. The

gardening. Physical therapy engaged the patient by relat-

initial therapy program emphasized activities designed to

ing necessary exercises to his hobby. A plan was designed

promote sensorimotOr functioning and independence in

with the ratient ancl the family to extend the gardening

self-care. The primary occupational environment was self-

maintenance, and the relative role was that of inde- occupation into his occupational environments and relat-

ed roles upon discharge.

pendent adult. Although he was making satisfactory pro-

gress in self-care, discussion with the paticnr revealed

that the treatment program was not meaningful. The pa- Example 4: Public Scbool Special Education for

tient was experiencing lirtle relative mastery. The thera- Behavior Disorder, Attention DefiCit, and Fine iViotor

pist suggested a change in the occupational environment Problems

and role. The patient and the therapist selected the pa-

The 15-year-old student was referred to the occupational

tient's work and the role of architect to guide treatment.

therapist for handwriting and attention problems. She

Occupational activities were incorporated to provide a

had a severe behavior disorder, an attention deficit disor-

better fit with what the patient found meaningful. Occu-

der, and fine motor problems. She came from a dysfunc-

pational challenges were included that engaged his occu-

tional family and was failing in school. Her intelligence

pational adaptation process. For example, the patient's

was within average range. She was described as explosive,

drafting tools were brought in and the patient and thera-

phvsicallv aggressive, and at risk for dropping out of

pist obselV'ed the patient's adaptiveness, identified the

sources of interference with relative masterv, and de- schooL She had no vocational interests or goals. The

therapist's occupational adaptation assessment revealed

signed a rlan to help the ratient become more adaptive

and increase relative mastery. that the student was occupationally dvsadaptive in all of

her occupational environments and roles and experi-

enced no relative mastelY When faced with an occupa-

tional challenge, the student used rrimalY energv most of

E\wnple 3: Inpatienl Rehabilitation for Post-Cerebral

the time Her fine motor deficits interfered with perform-

Vascular Accident

ance tasks. Her adaptive response behaviors were largel\'

After 1 month of rehabilitation, this patient's occupation- hypersrabilil.cd, which usually resulted in her being fixat-

al skills were lirtle improved. Aphasia and depression ed with no action occurring. She would finallv respond, "I

q

continued to interfere with therarv. It seemed to the can't do it. At other times, she was hypermobile and

therapist and the patienr's wife that the patient was not approached tasks randomly with no apparent plan of

meeting his potential. To the extent possible, the thera- action. She perseverared in the use of existing but ineffec-

pist reviewed the treatment program with the patient. tive adaptive response modes. Her ability to generate,

The patient showed little response to an\1 of the activities evaluate, and integrate adaptive responses was dvsadap-

being used and was not experiencing any relative mas- tive. She was markedly inefficient and ineffective and ex-

tery. The therapist determined that, although the patient perienced little satisfaction.

needed much more occupational readiness. it was essen- The tberapist collaborated with the special eduGl-

tial to begin occupational activitv to increase motivation. tion teacher to develor a holistic program to tre,1I the

Further discussion with family members resulted in a new student's occupational dysadaptation. Occupational

treatment plan that emphasized occupational activit\'. readiness was instituted with a varietv of media designed

Gardening became the primarv moclalitv for occupational to improve the student's fine motor skil1s, develop inter-

therapy because it bad been the patient's main Icisure ests. and increase self-control. As the therapeutic climate

occupation. Occupational readiness training that empha- I..'volved, the student began to express how, as a child. she

sized strength and sensorimotor skills related to garden- had always loved to stvle her do]I's hair. As her interest in

ing was begun by a certified occupational therapv assis- hairstvling became more apparent, the thet-apist expand-

tant The occupational therapist emphasized to the ed the occupational readiness program by giving her in-

patient the connection between the exercises and the formation about the role expectations of a hairstylist and

new program. Occupational activitv was incorporated the knowledge required to be licensed and by giving her

when possible (e.g., following oral and written directions home therapy assignments to visit and discuss work with

in the care of seedlings, managing the plants in the clinic, practicing hairstvlists As a result of the occupational

using more complex gardening tools, tcnding plants in readine~s, the student decided she wanted to become a

the outdoor garden). Sen.sorimotor, cognitive, and ps\'- hairstvlist. Occupational readiness was further tailored to

chosocial systems improved through occupational readi- he consistenr with her goal: A home rrogram that empha-

ness and occupational actiVity. Relative masterv also be- sized fine motor tasks and other coordination activities

The American Journal of Occu.pational Tberapr 923

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

specific to her work goal, and relevant behavioral goals ence to a theoretical framework that concentrates treat-

such as timeliness, dependability, and impulse control ment on the patient's internal occupational adaptation

were instituted in the classroom process. The construct of occupational adaptation dis-

In addition, the therapist gUided the student into cussed in Part 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992) provides an

extracurricular aetivitie~ (0 widen her exposure to occu- overall exp\ana[ion of [his process and how the patient

pational challenges (e.g., decorating for the school dance, generates, evaluates, and integrates adaptive responses.

collecting and sorting food for a community food panuy). We believe that interventions that affect relative mastelY

She began to display more mature adaptive response are instrumental in helping the patient become more

behaviors and to modify her existing adaptive response adaptive, thus enhancing the potential for a productive

modes. For example, as the student became more aware and satisfying life.

of her dysadaptation, she began to anticipate the ways in In treatment based on the occupational adaptation

which her adaptive response modes were obstacles to frame of reference, the occupational environment is as

relative mastery and to generate alternative modes and important as the patient's physical or mental condition

modified responses. These changes in her occupational and is conceptualized as a blend of the physical, SOCial,

adaptation process resulted in greater relative mastery. and cultural influences that affect the patient. The style of

The most dramatic improvements occurred in satisfac- patient-therapist interaction is process oriented rather

tion to self and others. than performance driven. The therapist's primaly gauge

As therapy continued, the student integrated these of effectiveness is change in the patient's internal occupa-

changes and began to generalize her new occupational tional adaptation as opposed to improvement in self-care

adaptation process. She was able to see the relevance of or other function-oriented criteria. The concept of rela-

school and the need to develop her fine motor skills, self- tive mastery is introduced as an outcome of change in

control, and social skills as part of her future life goals. occupational adaptation. The occupational adaptation

The fine motor exercises were improving her handwriting practice model views mastery as a relative phenomenon

and she noted her improved efficiency in the use of hair- that can, however, be understood in terms of three pre-

styling tools and eqUipment. dictable outcomes. Such outcomes are identified and

Additional occupational activity was begun in which methods for measurement are proposed. The effect of

the student began to style the hair of other students. She relative mastelY on treatment is described in practical

achieved positive recognition and acceptance from her illustrations that provide an oven/iew of occupational ad-

peers for her competency in this activity. Her relative aptation concepts and assumptions and their effect on

mastery increased substantially. As therary progressed, the nature of practice. These illustrations clarify the con-

the teacher noted to the therapist that the student was struct of occupational adaptation, the conditions and pa-

modifying her way of doing things by attempting to plan rameters of occupational adaptation practice, and use of

her approach to tasks, displaying more organization, and the occupational adaptation practice guide.

showing more neatness and pride in her handwriting. We believe that the occupational adaptation frame of

Behavioral problems in the classroom declined. The stu- reference (Schkade & Schultz, 1992) and model for prac-

dent had begun to initiate changes in how she responded tice have potential benefits for the occupational therapist.

to other occupational challenges (e.g., occupational per- First, they may formally articulate the current practice of

formance at home ancJ at her part-time job). therapists who use a similar approach but have lacked a

The occupational therapist discontinued direct ser- formal structure, thus validating what has been perceived

vice but periodically monitored the student's progress. as intuitive by many therapists. Second, they may provide

She made suggestions to the teacher on ways to proVide a fresh perspective for therapists who have practiced

the student opportunities to increase relative mastery in within the medical model but arc searching for a practice

the occurational environment of school. To the student model that is more holistic. Third, the model offers a

she suggested ways to increase her awareness of her generic perspective; it is not specific to any particular

adaptive response behaviors, to develop new adaptive dysfunction or condition. Consequently, the model is ap-

response modes, and to evaluate and affect her relative plicable to many settings, such as schools, hospitals, and

mastery when faced with new occupational challenges. home health care. It is an appropriate practice model for

patients with a variet)' of conditions such as behavioral

problems, physical dysfunction, developmental disability,

or psychosocial dysfunction.

Conclusion

The concepts and assumptions presented in this pa-

The Occupational Adaptation Practice Model integrates per and in Part 1 (Schkade & Schultz, 1992) remain to be

the beliefs, principles, and techniques that have been formally tested. We hope that these writings will lead to

addressed by many theorists and are reflected taCitly in increased scholarly debate and research on the integra-

the practice of many clinicians. The uniqueness of the tive nature of occupation and adaptation with regard to

Occupational Adaptation Practice Model lies in the adher- the discipline and the practice of occupational therapy...

924 October 1992. Volume 46, Number 10

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Acknowledgments Breines, E. (1986). Or~gins and adaptations A philosophy

ofpractice. Lebanon, NJ: Geri-Rehab.

We acknowledge the impetus, support, and challenging critical Clark, P. N. (1979), Human clevelopment through occupa-

comments rrovided by the doctoral planning committee at Tex- tion: A philosophy and conceptual moclel for practice, part 2,

as Woman's University: Grace Gilkeson, EliD, on, hIOTA, Adelaide American journal of Occupational Therapy, 33, 577-585,

Flower, "'lA, OTR: Harriett Davidson, MA, OTR, Carol Freeman, ,Il~. fidler, G. S (1981). From craftS to competence, American

0l'R; Nancy Griffin, EclD,OTR: Nancy Nashiro, PhD, OTI{; Jean Spen-

journal of Occupational Therapy, 35, 567-573.

cer, PhD, OTR (Chair); and Virginia White, PhD, OTR We also appre- Fidler, G. S" & Fidler,] W. (1963). OccupationalthempJl

ciate the input from Lela Llorens. PhD, om. rA01A Anne Hender- A communication process in psychiatry New York: MacMillan,

son, PhD, OTR, fAOTA: and Kathlyn Reed, PhD. om, FAOTA, who Fidler, G. S., & Fidler, J, W, (1978), Doing and becoming:

provided thoughtful reading of earlier versions, Purposeful aCtion and self-actualization, American journal of

Occupational Therapy, 32, 305-310.

Fine, S. (1990). Resilience and human adaptability: Who

Appendix rises above aclversity7-1990 Eleanor Clark Slagle lecture.

Occupational Adaptation Guide to Practice American journal 0/ Occupational Therapy, 45, 493-503,

GilfoyJe, E, Gracly, A., & Moore.] (1990) Children adapt

Occupational Adaptation Data Gathering/Assessment (2nd ed.). Thorofare, N] Slack.

What are the patient's occupational environments and roles?

Kielhofner, G. (Ed.). (1985). A Model o/Human Occupa-

Which role is of primary concern to patient and family?

tion.' TheOl]' and application. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

What occupational performance is expeCted in the primary oc-

King, L, (1978). Toward a science of adaptive responses-

cupational environment and role,?

1978 Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecture. American journal o/Occu-

What are the physical, SOCial, cultural features of the primary

pational Tberapy. 32, 429-437.

occupational environment and role?

Kleinman, B, L., & Bulkley, B. L. (1982), Some implications

What is the patient's sensorimotor, cognitive, and psychosocial

of a science of adaptive responses. American journal ofOccu-

status?

pational Therapy. 36, 15-19.

What is the patient'S level of relative mastelY in the primary

Lindquist,J E, Mack, \XI, & Parham, L. D (1982). Asynthe·

occupational environment and role,?

sis of occupational behavior and semory integration concepts in

What is faCilitating or limiting relative mastery in the primary

theory and practice, Parr 1. Theoretical foundations, American

occupational environment and role.? journal of Occupational Therapy, 36, 36'5-374,

Occupational Adaptation Programming

Llorens, L. (1984). Theoretical conceptualiLations of occu-

What combination of occupational readiness and occupational

pational therapy: 1960-1982. Occupational Therapl' in /II/ental

activity is needecl ro promme the patienr's occupational ad-

Health. 4(2). 1-14

aptation proces.,?

Llorens, L. (1990), Foreword, In E. Gilfoyle, A, Gracly, &]

What help will the patient need to assess occupational re-

Moore, Cbildren adapt (2nd eel., pp, xi-xii), Thorofare, NJ:

sponses and use the results to affect the occupational adapta- Slack,

tion process?

Marringly, C. (1991). What is clinical reasoning? American

What is the best method to engage the patient in the occupa-

Journal 0/ Occupational TherapF, 45, 979-986

tional adaptation program?

Meyer, A. (1922), The philosophy of occupational therapy,

Evaluation of the Occupational Adaptation Process Arcbil'es of Occupational Therapl', 1. 1-3,

lIow is the program affecting the patient's occupational adap-

Mosev, A. (1968) Recapitulation of onrogenesis: A theory

tation process? for practic'e of occupational therapy. American Journal of Oc-

• Which energy level is used most often (primary or

cupational Therapr. 22. 426-432.

secondarl')I Nelson, D. (1988). Occupation: Form and performance.

• What adaptive response mode is used most often (pree.xist-

American journal of Occupational Therapy. 42. 633-641,

ing, modified, or new)? . PeloqUin, S. )'vI. (1990), The patient-therapist relationship

• What is the most common adaptive response hehavlOr

in occupational therapv Understanding visions and images,

(primitive, transitional, or mature)?

American journal 0/ Occupational Therapl', 44, U-21.

What outcomes does the patienr show that reflect change in the

Reed. K. (1984). Models ofpractice in occupational ther-

occupational adaptation process? apl' Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

• Self-initiated adaptations?

Reill\', M, (1962) Occupational thet'apy can be one of the

• Enhanced relative mastery? great ide'as of 20th century medicine American Journal of

• Generali/.ation to novel activities?

Occupational Therapy, 16, 1.

What program changes are needed to provide maximum oppor-

tunity for occupational adaptation to occur?

Schkade, .r K, & Schult/., S. (1992) Occupational auapta-

tion: Toward a holistic approach for conternporalY practice,

Note, The italicized terms at'e constructs in the Occupational parr 1. American journal of Occupational Therapy. 46,

Adaptation frame of Reference (Schkade & Schultz, 1992), 829-H37

West, W (1989), Perspectives on the past and future, parr

1. American joU/ned of Occupational Tberapj', 43, 787-790,

Yerxa, E. (1967), Authentic occupational therapy -1966 El-

References

eanor Clarke Slagle lecture Americanjournalo/Occupational

American Occupational Therapy A'isociation (1979). The Therapy, 21, 1-9

philosophical base of occupational therapl', Americanjoui7wl Yerxa, E, (1989, October 30), What is this thing called occu-

of Occupational Tberapy, 33, 78'5. pation 7 Adl'ance for Occupational Therapists, p, 5.

The American Journal or Occupational tberapl' 925

Downloaded from http://ajot.aota.org on 07/22/2021 Terms of use: http://AOTA.org/terms

You might also like

- ASV PT30 Parts ManualDocument23 pagesASV PT30 Parts ManualTrevorNo ratings yet

- Venn Diagram: Learning OutcomesDocument9 pagesVenn Diagram: Learning OutcomesRosemarie GoNo ratings yet

- OT For Children With ADHDDocument12 pagesOT For Children With ADHDBeatrizIgelmo100% (1)

- Doll's House As A Feminist PlayDocument6 pagesDoll's House As A Feminist PlayAyesha ButtNo ratings yet

- Hollow Structural Sections LRFD Column Load TablesDocument128 pagesHollow Structural Sections LRFD Column Load TablesJhonny AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Occupational TherapyDocument13 pagesOccupational TherapyRiris NariswariNo ratings yet

- Uniform Terminology AOTA PDFDocument8 pagesUniform Terminology AOTA PDFLaura GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Tenses For SpeakingDocument34 pagesTenses For Speakingdsekulic_1100% (1)

- The Self From Various PerspectiveDocument31 pagesThe Self From Various PerspectiveMariezen FernandoNo ratings yet

- Business AgilityDocument40 pagesBusiness Agilityqtrang_1911No ratings yet

- Integration of Medication Management Into Occupational Therapy PracticeDocument7 pagesIntegration of Medication Management Into Occupational Therapy PracticeManuel PérezNo ratings yet

- Nursing TheoryDocument15 pagesNursing TheoryZahrah Maulidia Septimar0% (1)

- EntopiaDocument19 pagesEntopiadpanadeoNo ratings yet

- Reflection in and On Nursing Practices - How NursesDocument7 pagesReflection in and On Nursing Practices - How NursesChris LeeNo ratings yet

- Documenting Progress: Hand Therapy Treatment Shift From Biomechanical To Occupational AdaptationDocument6 pagesDocumenting Progress: Hand Therapy Treatment Shift From Biomechanical To Occupational AdaptationMarina ENo ratings yet

- Uniform Terminology For Occupationall THDocument8 pagesUniform Terminology For Occupationall THcjNo ratings yet

- 'The Appraisal Model of Coping: Assessment and Intervention Model For Occupational 'TherapyDocument10 pages'The Appraisal Model of Coping: Assessment and Intervention Model For Occupational 'TherapyAxeliaNo ratings yet

- Occupation-Centered Assessment of Children: Wendy CosterDocument8 pagesOccupation-Centered Assessment of Children: Wendy CosterAna Claudia GomesNo ratings yet

- Emotional Labour of Nursing Revisited - Caring and Learning 2000 (2001)Document8 pagesEmotional Labour of Nursing Revisited - Caring and Learning 2000 (2001)lightloomNo ratings yet

- The Use of Conceptual Modelos in Clinical PracticeDocument6 pagesThe Use of Conceptual Modelos in Clinical PracticeMeeLoLooZzaShzNo ratings yet

- ComparaçãoDocument7 pagesComparaçãoCarolina CruzNo ratings yet

- What Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisDocument14 pagesWhat Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisNataliaNo ratings yet

- Psychobiological Responses To Critically Evaluated M - 2017 - Neurobiology of STDocument6 pagesPsychobiological Responses To Critically Evaluated M - 2017 - Neurobiology of STTanushree BNo ratings yet

- 2022 - Weber - Physical Workplace Adjustments To Support Neurodivergent Workers - A Systematic ReviewDocument53 pages2022 - Weber - Physical Workplace Adjustments To Support Neurodivergent Workers - A Systematic ReviewRodrigo Assunção RosaNo ratings yet

- Work Transitions After Serious Hand Injury: Current Occupational Therapy Practice in A Middle-Income CountryDocument14 pagesWork Transitions After Serious Hand Injury: Current Occupational Therapy Practice in A Middle-Income CountryNataliaNo ratings yet

- Brazen, L. (1992) - The Difference Between Conceptual Models, Practice Models. AORN Journal, 56 (5), 840-844Document4 pagesBrazen, L. (1992) - The Difference Between Conceptual Models, Practice Models. AORN Journal, 56 (5), 840-844Murti SaniyaNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Occupational Therapy Approaches For Perceptual Deficits in Adults With Brain InjuryDocument6 pagesA Critical Analysis of Occupational Therapy Approaches For Perceptual Deficits in Adults With Brain InjurysaranottenNo ratings yet

- PDF Editor: Occupational Science Is MultidimensionalDocument3 pagesPDF Editor: Occupational Science Is Multidimensionalsergiotasio8349No ratings yet

- Application of Simplified Complexity Theory Concepts For Healthcare Social Systems To Explain The Implementation of Evidence Into PracticeDocument20 pagesApplication of Simplified Complexity Theory Concepts For Healthcare Social Systems To Explain The Implementation of Evidence Into PracticeMelika FerdiantiNo ratings yet

- ADocument7 pagesARaphael AguiarNo ratings yet

- Mckenna 2013Document4 pagesMckenna 2013zettaknNo ratings yet

- Met A CognitionDocument10 pagesMet A CognitionPaulina Medina RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Mary - Law - PEO - Model With Cover Page v2Document16 pagesMary - Law - PEO - Model With Cover Page v2RepositorioNo ratings yet

- Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in Primary Care: A Profile of PracticeDocument8 pagesCanadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM) in Primary Care: A Profile of Practiceisabel gomezNo ratings yet

- Using Trauma Informed Care As A Nursing Model of CDocument7 pagesUsing Trauma Informed Care As A Nursing Model of CWinda KasyemNo ratings yet

- Contributions From Neuroscience To The Practice of Cognitive Behaviour T TherapyDocument7 pagesContributions From Neuroscience To The Practice of Cognitive Behaviour T TherapyNathalyNo ratings yet

- Mary Law PEO Model PDFDocument15 pagesMary Law PEO Model PDFalepati29No ratings yet

- Professional Strategies in Work-Related Practice: An Exploration of Occupational and Physical Therapy Roles and ApproachesDocument9 pagesProfessional Strategies in Work-Related Practice: An Exploration of Occupational and Physical Therapy Roles and Approachesasr27No ratings yet

- CmopeDocument3 pagesCmopeEdu EduNo ratings yet

- ROYEEN Occupation ReconsideredDocument10 pagesROYEEN Occupation Reconsideredbruno.becharaNo ratings yet

- 00 A Consensus Definition of Occupation-Based Intervention From A Malaysian PerspectiveDocument9 pages00 A Consensus Definition of Occupation-Based Intervention From A Malaysian Perspectivesarawu9911No ratings yet

- 569 PDFDocument7 pages569 PDFferas ahmedNo ratings yet

- TFN Finals ReviewerDocument3 pagesTFN Finals Reviewerediyette parduaNo ratings yet

- Adaptation Model AnalysisDocument3 pagesAdaptation Model AnalysisDana FlorenceNo ratings yet

- Occupational Stress: Reflections On Theory and PracticeDocument16 pagesOccupational Stress: Reflections On Theory and PracticeAnonymous N9bM1y6HhjNo ratings yet

- 16-29 The Role of Theory in Clinical PracticeDocument15 pages16-29 The Role of Theory in Clinical Practicesara mohamedNo ratings yet

- Nursing Theories MISS KUSIDocument55 pagesNursing Theories MISS KUSISuleiman KikulweNo ratings yet

- September 2014 1492840775 36Document4 pagesSeptember 2014 1492840775 36Metiku DigieNo ratings yet

- Shaping The Goal Setting Process in OtDocument16 pagesShaping The Goal Setting Process in Otapi-291380671No ratings yet

- Simulation and Its Role in Medical Education: Contemporary IssueDocument6 pagesSimulation and Its Role in Medical Education: Contemporary IssueYorim Sora PasilaNo ratings yet

- Otd PsychosocialDocument4 pagesOtd PsychosocialIzzah PijayNo ratings yet

- The Value of Peplau's Theory For Mental Health Nursing.: Jones ADocument13 pagesThe Value of Peplau's Theory For Mental Health Nursing.: Jones AmejulNo ratings yet

- ¿09. A. Professional Knowledge and The Epistemology of Reflective PracticeDocument12 pages¿09. A. Professional Knowledge and The Epistemology of Reflective PracticeEventos IINDEQNo ratings yet

- 01 Devonport PCDocument12 pages01 Devonport PCInten Dwi Puspa DewiNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1356689X01904266 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1356689X01904266 MainaramNo ratings yet

- Group1 - Models TheoriesDocument5 pagesGroup1 - Models TheoriesDEVORAH CARUZNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Professional Nursing Practice Behaviors in Hospital SettingsDocument7 pagesPredictors of Professional Nursing Practice Behaviors in Hospital SettingsSriMathi Kasi Malini ArmugamNo ratings yet

- Reeducative TherapyDocument2 pagesReeducative TherapyYoshita AgarwalNo ratings yet

- A Complex View of Professional Competence: Amanda - Torr@weltec - Ac.nzDocument16 pagesA Complex View of Professional Competence: Amanda - Torr@weltec - Ac.nzDEVINA GURRIAHNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Professionalism A Consolidation of Current ThinkingDocument6 pagesAssessment of Professionalism A Consolidation of Current ThinkingAnonymous GOUaH7FNo ratings yet

- Boswelletal2010integrativecompetency (1) - 220312 - 165927Document10 pagesBoswelletal2010integrativecompetency (1) - 220312 - 165927Luciano RestrepoNo ratings yet

- Occupational Health Physical TherapyDocument4 pagesOccupational Health Physical Therapyphfisio007No ratings yet

- Research Article AotaDocument9 pagesResearch Article AotasarahNo ratings yet

- Therapist Competence in Case Conceptualization and Outcome in CBT For depression-OPTIONALDocument20 pagesTherapist Competence in Case Conceptualization and Outcome in CBT For depression-OPTIONALMissDee515No ratings yet

- Peplau's Theory of Interpersonal Relations: Application in Emergency and Rural NursingDocument5 pagesPeplau's Theory of Interpersonal Relations: Application in Emergency and Rural NursingxicaNo ratings yet

- Multiprofessional Healthcare Team: Concept and Typology: Marina PeduzziDocument6 pagesMultiprofessional Healthcare Team: Concept and Typology: Marina PeduzziAhmad FauzanNo ratings yet

- LIT Sullair OFD1550 Tier 4 Final Brochure - PAP1550OFDT4F202102-7 - ENDocument4 pagesLIT Sullair OFD1550 Tier 4 Final Brochure - PAP1550OFDT4F202102-7 - ENbajabusinessNo ratings yet

- Crack Prelims in 60 DaysDocument4 pagesCrack Prelims in 60 Dayssmanju291702No ratings yet

- Список Сводеша Уточнение СемантикиDocument44 pagesСписок Сводеша Уточнение СемантикиalexNo ratings yet

- AN2799 Application Note: Measuring Mains Power Consumption With The STM32x and STPM01Document14 pagesAN2799 Application Note: Measuring Mains Power Consumption With The STM32x and STPM01am1liNo ratings yet

- SQL Queries PDFDocument10 pagesSQL Queries PDFmfarooq28No ratings yet

- Test Bank For Campbell Biology, 10th Edition, Jane B. Reece, Lisa A. Urry, Michael L. Cain, Steven A. Wasserman, Peter V. Minorsky Robert B. JacksonDocument35 pagesTest Bank For Campbell Biology, 10th Edition, Jane B. Reece, Lisa A. Urry, Michael L. Cain, Steven A. Wasserman, Peter V. Minorsky Robert B. Jacksonhermeticfairhoodr2ygm100% (10)

- PLP 26 PDFDocument29 pagesPLP 26 PDFdeepaklovesuNo ratings yet

- C6085 - Et3aDocument2 pagesC6085 - Et3aCu TiNo ratings yet

- Development Learning Media Based Interactive Multimedia To Increase Students Learning Motivation On Plant Movement MaterialsDocument7 pagesDevelopment Learning Media Based Interactive Multimedia To Increase Students Learning Motivation On Plant Movement MaterialsFandi Achmad RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Improving Efficiency Thru ModellingDocument5 pagesImproving Efficiency Thru ModellingAli AliNo ratings yet

- LS - Group 07Document14 pagesLS - Group 07ABHIJEET SAHOONo ratings yet

- (ECM) X1 (Diesel)Document5 pages(ECM) X1 (Diesel)Jairo CoxNo ratings yet

- Design of FIR Filter Using Window Method: IPASJ International Journal of Electronics & Communication (IIJEC)Document5 pagesDesign of FIR Filter Using Window Method: IPASJ International Journal of Electronics & Communication (IIJEC)International Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- CIS Apple IOS 15 and IPadOS 15 Benchmark v1.0.0Document237 pagesCIS Apple IOS 15 and IPadOS 15 Benchmark v1.0.0aguereyNo ratings yet

- Advance Shoes For Blind PeopleDocument19 pagesAdvance Shoes For Blind PeopleMoiz Iqbal100% (1)

- IHRMDocument14 pagesIHRMPranayNo ratings yet

- The Martian ChroniclesDocument23 pagesThe Martian ChroniclesIlana GuttmanNo ratings yet

- Guias de Inspeccion Cheyenne IIDocument23 pagesGuias de Inspeccion Cheyenne IIesedgar100% (1)

- Star Matching ChartDocument3 pagesStar Matching ChartAsmNo ratings yet

- Today's Class: Opera&ng) Systems CMPSCI) 377 Introduc&onDocument20 pagesToday's Class: Opera&ng) Systems CMPSCI) 377 Introduc&onRajesh SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Microscopic Examination of Human Hair and Animal Hair DoneDocument5 pagesMicroscopic Examination of Human Hair and Animal Hair Doneangeliquezyrahangdaan29No ratings yet

- Tesis Damian TDocument359 pagesTesis Damian TpalfrancaNo ratings yet