0% found this document useful (0 votes)

588 views9 pagesUnderstanding Form Follows Function

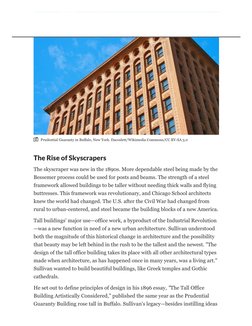

The phrase "form follows function" was coined by architect Louis Sullivan in 1896 to describe how a building's exterior should reflect its interior functions. Sullivan designed skyscrapers like the Wainwright Building whose three-part facade changed to match the different functions within. Frank Lloyd Wright expanded on the phrase to mean that form and function are inherently connected and influenced by environmental factors. The phrase has remained influential in architecture for over a century.

Uploaded by

Salim DubrehCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

588 views9 pagesUnderstanding Form Follows Function

The phrase "form follows function" was coined by architect Louis Sullivan in 1896 to describe how a building's exterior should reflect its interior functions. Sullivan designed skyscrapers like the Wainwright Building whose three-part facade changed to match the different functions within. Frank Lloyd Wright expanded on the phrase to mean that form and function are inherently connected and influenced by environmental factors. The phrase has remained influential in architecture for over a century.

Uploaded by

Salim DubrehCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd