Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Contest For A Royal Title Herod Ver

Uploaded by

Jack WestOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Contest For A Royal Title Herod Ver

Uploaded by

Jack WestCopyright:

Available Formats

ASE 28/2(2011) 93-106

Gabriella Gelardini

The Contest for a Royal Title:

Herod versus Jesus in the

Gospel According to Mark

(6,14-29; 15,6-15)*

I. INTRODUCTION

Personal titles, e.g., titles of honor, nobility, and office, or academic ti-

tles, are the subject of psycho- and socio-onomatology. Its theory teaches

us that titles confer prestige upon individuals and thus allocate them to

social positions. Furthermore, titles entitle persons to take possession of

something and endow them with the authority to defend their possession

by force.1

It is therefore evident that titles potentially bear a great deal of po-

litical as well as social conflict, as the trend researcher and futurologist

Karl-Heinz W. Smola has suggested: «The name (title included) is not ev-

erything, but without a good name everything is nothing».2

The Gospel according to Mark narrates inter alia the story of a

conflict-laden contest for a title, namely, a royal title. The tragic adver-

saries in this narrative – who may not seem obvious at first glance but

all the more during a close reading – are Herod Antipas and Jesus. The

rivalry between these two opponents dramatically exemplifies the truth

of Smola’s dictum.

In what follows, I first consider linguistic renditions of title and

name, of political achievements and failures, and of Herod’s demise. Sec-

––––––––––––

* I am grateful to Dr. Mark Kyburz for proofreading this essay and to Brinthanan Puva-

neswaran for his support in gathering the needed literature.

1 Dieter Stellmacher, “Namen und soziale Identität: Namentraditionen in Familien und

Sippen”, in: Ernst Eichler et al. (eds.), Namenforschung: Ein internationales Handbuch zur

Onomastik, 3 vols. (Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, 11), Berlin:

de Gruyter, 1995-1996, II, 1726-31; Iwar Werlen, “Namenprestige, Nameneinschätzung”, in:

Eichler et al., Namenforschung..., II, 1738-43.

2 N.N., “Name”, n.p. [cited 27 March 2011]. Online: http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Name.

93

09. Gelardini.pdf 1 23/02/12 12.44

ondly, I juxtapose these issues in regard to Jesus and thereby demon-

strate – particularly based on Mark 6,14-29 – that the narrative con-

strues Herod unpredictably as the kingmaker of the Messiah.

II. HEROD ANTIPAS

1. Herod’s Titles and Names According to Mark

The key Greek word denoting the royal title in Mark is basileus.

The term appears for the first time in Mark 6,14, that is, the opening

verse of the account of John the Baptist’s death. As a title, the term re-

fers to Herod Antipas.

Overall, the title basileus occurs twelve times in Mark (6,14.22.25.

26.27; 13,9; 15,2.9.12.18.26.32). Out of these twelve instances, it re-

fers on five occasions, and exclusively in this pericope Mark 6,14-29,

to Herod (Mark 6,14.22.25.26.27), and on six and exclusively in the fif-

teenth chapter to Jesus (Mark 15,2.9.12.18.26.32). Only once does it re-

fer to unspecific rulers in the plural (Mark 13,9).

Semantically, basileus in the singular may mean – apart from «king

and emperor» – «prince, lord, and also ruler». The term hence points gen-

erally to a most potent holder of a particular political – and along with

this military – power over a limited geographical area.3

The key Greek word denoting the king’s kingdom is basileia. Over-

all, the term recurs twenty times in Mark (1,15; 3,242; 4,11.26.30; 6,23;

9,1.47; 10,14.15.23.24.25; 11,10; 12,34; 13,82; 14,25; 15,43). Out of

these twenty instances, it refers only once to Herod’s kingdom (Mark

6,23), but on fifteen occasions to the kingdom of God (David) (Mark 1,

15; 4,11.26.30; 9,1.47; 10,14.15.23.24.25; 11,10; 12,34; 14,25; 15,43),

and on four to other kingdoms (twice in Mark 3,24; twice in 13,8). While

Herod uses this word only once, the author places it in Jesus’ mouth on

seventeen occasions.

Semantically, basileia may mean in a functional sense «kingly of-

fice, kingdom, hereditary monarchy, kingly reign» or in a geographical

sense «kingly dominion».4

––––––––––––

3 “Basileus”, in: H.G. Liddell – R. Scott (eds.), A Greek-English Lexicon: With a Revised

Supplement. With the assistance of Roderick McKenzie, rev. and enl. by Henry Stuart Jones,

Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1996 (Reprint of the 9th ed. 1940), 309-10; Menge-Güthling,

“basileus”, in: Langenscheidts Großwörterbuch Altgriechisch-Deutsch, Berlin, Langen-

scheidt, 199428, 133; Walter Bauer, “basileus”, Griechisch-deutsches Wörterbuch zu den

Schriften des Neuen Testaments und der frühchristlichen Literatur. In the Institut für Neu-

testamentliche Textforschung, Münster, with the assistance of Viktor Reichmann, ed. by Kurt

Aland and Barbara Aland, Berlin, de Gruyter, 19886, 272-73.

4 Liddell–Scott, “basileia”, in: A Greek-English Lexicon..., 309; Menge-Güthling, “basi-

leia”, in: Langenscheidts Großwörterbuch..., 132; W. Bauer, “basileia”, in: Griechisch-deut-

94

09. Gelardini.pdf 2 23/02/12 12.44

In summary, the royal title in Mark is only used for Herod and Je-

sus. While Herod speaks only once of «his kingdom», Jesus – and only

he – speaks exclusively of the «kingdom of God».

The one and only Greek name that Herod is granted in Mark is Hē-

rōdēs. Overall, this name is used on eight occasions and almost exclu-

sively in the pericope of concern (Mark 6,14.16.17.18.20.21.22; 8,15).

Out of these eight instances, the name is used on seven occasions by

the author himself, and once by Jesus (Mark 8,15). Apart from Herod,

the feminine version of this name, Hērōdias, is given to his wife on

three occasions, again in the pericope of concern (Mark 6,17.19.22),

and beyond it twice to a collective, Hērōdianoi, which is obviously not

only associated with the Herodian court but also equipped with power

(Mark 3,6; 12,13).

Semantically, the word stem Hērōd- derives from the Greek noun

hērōs, which stands for the English word «hero, demigod», and assigns

to this theophoric name the meaning «heroic [s]cion».5

In summary, Herod Antipas is addressed only as «Herod», that is,

by the only Greek name that semantically implies a heroic, or even

semi-divine descent.

Based on this brief linguistic rendition of titles and names in Mark,

I conclude firstly that the author intentionally addresses Herod as «king»,

particularly because he has him speak of “his kingdom”, and secondly

that the author seems to purposefully construct a narrative competition

between Herod and Jesus, who are both royal and heroic individuals of

divine descent.

2. Herod’s Titles and Names According to Other Sources

Comparing the above statistical evidence on Herod’s title and name

in Mark with other sources, particularly Josephus, but also different New

Testament texts, along with epigraphical and numismatic evidence, re-

veals a discrepancy in regard to Herod’s title but not in regard to his

name.

Within the New Testament, the only other passage in which Herod

is addressed as «king» is Matt 14,9.6 Apart from that, Herod – and only

––––––––––––

sches Wörterbuch..., 270-71; Ulrich Lutz, “basileia”, in: Horst Balz – Gerhard Schneider (eds.),

Exegetisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament, 3 vols., Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 19922, I,

481-91.

5 Hellmut Haug, “Herodes”, in: Hellmut Haug (ed.), Namen und Orte der Bibel (Bibel-

wissen), Stuttgart, Deutsche Bibelgesellschaft, 2002, 148-49.

6 The only other minor literary source besides the New Testament that addresses Herod

Antipas twice as “king” is Justin (Dial. 103.4).

95

09. Gelardini.pdf 3 23/02/12 12.44

he – is addressed on four occasions as tetraarchēs (Matt 14,1; Luke 3,

19; 9,7; Acts 13,1).

More differentiated is the account of Josephus. He tells us that Herod’s

father, King Herod the Great, had altered his penultimate will by ar-

ranging for Herod to succeed him on the throne, while placing the lat-

ter’s older brother Archelaus and his younger half-brother Philip under

his authority (B.J. 1.562,646; A.J. 17.146). Endless court litigations prompt-

ed their father to alter his will once more on his deathbed, yet this time

in favor of Archelaus, who was supposed to become king, while placing

Herod and Philip as «tetrarchs» under the elder’s authority (B.J. 1.664;

2.182; A.J. 17.188; 18.36,102, 109,122,148,240).

In his final will, Herod the Great also decreed that this should be af-

firmed by the emperor, that is, Augustus. After Herod’s death, Arche-

laus thus prepared to depart for Rome. Shortly before his departure,

however, at Pessach in the year 4 B.C.E., he faced a revolt in Jerusa-

lem, sparked by the mourning for those men that Herod had executed

shortly before dying (B.J. 1.648-655), because they had cut down the

golden eagle hanging above the gate of the temple. In an uprise inten-

tionally perpetrated to test his power, Archelaus’s attempts to appease

the people failed. In order to contain what could end in conflagration,

he summoned his entire army and ordered it to confront the rioters in

the temple precincts. To widespread dismay, his move resulted in the

death of 3,000 citizens – and, as one may suspect, this was taken as a

bad omen (B.J. 2.1-13; A.J. 17.206-218).

Possibly encouraged by these troubles, Herod Antipas also boarded

a ship bound for Rome, in order to strive for the kingdom and to chal-

lenge his brother’s claim to the throne in the emperor’s presence, based

on his father’s penultimate will. He received counsel to proceed thus

not only from the orator Ireneus and from Ptolemy, the brother of the

influential court historian Nicolaus of Damascus, but also from his

mother and his aunt Salome, along with the majority of his relatives.

The latter favored self-government under Roman supremacy; should

such an arrangement fail, they considered Herod preferable to Arche-

laus (B.J. 2.20-22; A.J. 17.224-227).

Both Sabinus and Salome accused Archelaus before Caesar, partic-

ularly for the crime committed in the temple immediately before his

departure for Rome. In ordering the death of the offenders, he prema-

turely decreed capital punishment, a power not yet granted to him by

Caesar. When Augustus had carefully considered both parties’ claims, he

assembled the principal persons among the Romans and gave the peti-

tioners leave to speak (B.J. 2.23-25; A.J. 17.228-229, 231).

The accusations against Archelaus were eloquently brought forth by

Salome’s son Antipater. His main argument was that Herod the Great

had made his last will during his fatal illness, that is, when his father’s

96

09. Gelardini.pdf 4 23/02/12 12.44

mind was more infirm than his body and thus unable to reason soundly

(B.J. 2.26-33; A.J. 17.230-239). This argument was invalidated by Nico-

laus’s plea on behalf of Archelaus, who reasoned that the latter will

should be deemed valid, because Herod the Great had therein appoint-

ed Caesar as the person who should confirm the proposed succession,

and «for he who showed such prudence as to recede from his power, and

yield it up to the lord of the world, cannot be supposed mistaken in his

judgment about [...] his heir» (B.J. 2.36).7 After Caesar had declared that

Archelaus was basically «worthy» of succeeding his father and after he

had dismissed the assembly, the mother of the two competing brothers,

as another bad omen, died (B.J. 2.34-39; A.J. 17.240-250).

Only a few days after a second assembly, in which fifty Jewish am-

bassadors – along with the 8,000 Jews of Rome – reiterated not only

Antipater’s accusation against Archelaus but also the plea for self-gov-

ernment (B.J. 2.80-92; A.J. 17.299-316), Augustus apportioned one

half of Herod the Great’s kingdom to Archelaus, who would bear the

name Ethnarch. Augustus promised to make Archelaus king if he ren-

dered himself worthy of that dignity. Augustus divided the other half

of the kingdom into two “tetrarchies”, and assigned these equally to

Herod and Philip (B.J. 2.93-95,167-168,183; A.J. 17.317-320; 18.27,

136,252). Thus, the brethren followed in the footsteps of their father

Herod and their uncle Phasaelus, who had each been granted a tetrar-

chy by Antonius (B.J. 1.244; A.J. 14.326).

As is well known, Archelaus did not prove worthy of the royal dig-

nity, and was deposed after ten years of regency in 6 C.E. Herod, by

contrast, was reconfirmed as tetrarch of Galilee and Perea, and once

again in 14 C.E. when Tiberius took office (B.J. 2.167-168).

The tetrarchy allotted to Herod is also mentioned once in Strabo

(Geogr. 16.2.46). Besides, the title “tetrarch” occurs in the fragments of

Nicolaus of Damascus on the one hand (FGrH 90, frag. 136 § 11), and

in the two known inscriptions relating to Herod on the Greek islands of

Cos and Delos on the other. Finally, it also appears on every coin per-

taining to a total of six mintings discovered so far (while the first bears

no date, the following were minted in the 24th, 33rd, 34th, 37th, and

43rd year of his reign).8

In summary, considering all available sources in regard to Herod’s

title makes clear that the observed literary discrepancy is rooted in a

longstanding conflict between him and his brother Archelaus about who

––––––––––––

7 Flavius Josephus, The Works of Flavius Josephus: Complete and Unabridged (Version

1.3). Accordance 9: Bible Software. OakTree Software Version 9.2.1, 2011, print transl. by

William Whiston, Rev. ed., Peabody, Hendrickson, 1987, n.p.

8 Morten Hørning Jensen, Herod Antipas in Galilee: The Literary and Archaeological

Sources on the Reign of Herod Antipas and its Socio-Economic Impact on Galilee (WUNT,

2/215), Tübingen, Mohr Siebeck, 20102, 204-14.

97

09. Gelardini.pdf 5 23/02/12 12.44

was to succeed their father on the throne. Neither Archelaus nor Herod

asserted themselves before Augustus in Rome. Thus, they remained in

their father’s shadow, who had been granted kingship in this very city

by the Senate and later by the same Caesar (B.J. 1.182-185,386-400; A.J.

14.381-389). But Archelaus’s loss was greater compared to Herod’s, as

the latter’s journey to Rome at least met with the success to avert his

brother’s kingship.

Comparing the statistical evidence on Herod’s name with other

sources, particularly Josephus, but also different New Testament texts,

along with epigraphy and numismatics, reveals no discrepancy in re-

gard to his name. Neither the New Testament and Josephus, nor the sur-

viving inscriptions and coins, bear the name «Herod Antipas».

In general, and just as in Mark, the tetrarch is addressed solely as

«Herod».9 Apart from Mark, this name occurs on nineteen occasions in

the New Testament (Matt 14,1.3.6; Luke 3,1.192; 8,3; 9,7.9; 13,31; 23,72.

8.11.12.15; Acts 4,27; 13,1), on thirty-nine occasions in Josephus (B.J.

2.167,168,181,183; A.J. 18.27,27,36,102,104,105,106,1092,111,1122,1142,

115,116,117,118,1192,122,136,148,1502,240,243,247,2482,250,2512,2552),

once in Cassius Dio (55.27.6), twice in Justin (Dial. 103.4), twice in

the inscriptions, and also on every coin.

Apart from Nicolaus of Damascus (FGrH 90, frag. 136 § 11), only

Josephus uses Herod’s first name «Antipas», on seventeen occasions in

total, and mostly in the older text The Jewish-Roman War (B.J. 1.562,

646,664,668; 2.20,22,23,94,167; A.J. 17.202,188,224,2272,229,318).

As the son of his father’s fourth Samaritan wife, by the name of Mal-

thake (B.J. 1.562), Herod was given the praenomen Antipas at his birth

in the year 20 B.C.E.10 This seems to be the short form of both his

great-grandfather’s and his grandfather’s Greek name Antipatros, which

means «the father’s representative» (B.J. 1.181; A.J. 14.10).11 Obvious-

ly, Herod opted in public to strip himself of his praenomen – did he do

so on account of its meaning? – and named himself only by the patro-

nymic nomen gentile.12 Did he hope to be perceived “in place of his

father” instead, so as to compensate for the refused title by alluding to

his father as a nominal king of divine descent?13

––––––––––––

9 David C. Braund, “Herod Antipas”, in: The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary on CD-ROM

(Version 3.0). 1992. Accordance 9: Bible Software. OakTree Software Version 9.2.1, 2011,

n.p. [print ed. by David Noel Freedman, 6 vols., New York, Doubleday, 1992].

10 Abraham Schalit, “Antipas, Herod”, in: Encyclopaedia Judaica2, II, 204.

11 According to Josephus, this great-grandfather was first called Antipas (A.J. 14.10).

12 Helmut Rix, “Römische Personennamen”, in: Eichler et al., Namenforschung..., I, 724-32.

13 Harold W. Hoehner, Herod Antipas (SNTS.MS, 17), Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press, 1972, 105-09: Hoehner reads B.J. 2.167 as implicitly indicating that with the dismissal

of Archelaus in 6 C.E. the name “Herod” was granted to Antipas as a «dynastic title».

98

09. Gelardini.pdf 6 23/02/12 12.44

In summary, the onomastic conventions in regard to Herod’s use only

of his nomen gentile correspond more or less in all available sources. Col-

lating the data in Mark and other sources reveals that Herod is tetrarch

not king. That Mark nevertheless addresses him as «king» can safely be

perceived as an instance of literary irony14 based on a historic quarrel

regarding royal succession. Given this fraternal contest the narratively

constructed competition between Herod and Jesus is by all means plau-

sible.

3. Herod’s Political Life and End According to Mark

An encounter between Herod and Jesus is not reported in the Gos-

pel. However, the author reports in Mark 6,14-16 that Herod had «heard»

of him, «for his name – Jesus’ name – had become known». The nar-

rator continues with three unidentified collectives, which each express

their opinion regarding who Jesus could be. Interestingly, the author

suppresses the context in which these – shall we say – witnesses speak to

Herod. Did this perhaps take place during an interrogation?

After the testimonies, Herod concludes that Jesus is the risen Bap-

tist, whom he had beheaded, and hence neither Elijah nor a prophet.

Herod’s conclusion is alarming, as Jesus could possibly meet with the

same fate as did the Baptist. Why so? Because the ensuing account of

John’s decapitation in Mark 6,17-29 – it is the one and only, albeit also

illuminating account of Herod in Mark – shows that in the context of

certain constellations Herod comes across as a weak and tragic regent,

who is not able to guarantee his subjects legal security.

In what follows, it is not my purpose to analyze John the Baptist’s

life in great detail, as various scholars – and none less than Edmondo

Lupieri – have done this rigorously and impressively.15 Instead, I offer a

few general observations that allow for a systematic comparison of this

account with Jesus’ trial in Mark 15,6-15.

Mark 6,17-29 suppresses both Jesus’ name and also any spatial ref-

erence. Where Herod interrogates his witnesses, where the symposium

takes place, where the Baptist is beheaded, and in which tomb his

corpse is placed, remains concealed.16

––––––––––––

14 Jerry Camery-Hoggatt, Irony in Mark’s Gospel: Text and Subtext (SNTS.MS, 72),

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1992, 144-46. On the trope of irony (eirōneia) cf.

book 8.6.54 of Marcus Fabius. Quintilianus, Institutionis oratoriae Libri XII.

15 Edmondo Lupieri, “Johannes der Täufer”, in: Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart4,

IV, 514-17. The bibliography includes further publications of his on this topic.

16 Jürgen Zangenberg, “Jesus – Galiläa – Archäologie: Neue Forschungen zu einer Region

im Wandel”, in: Carsten Claußen – Jörg Frey (eds.), Jesus und die Archäologie Galiläas,

Neukirchen-Vluyn, Neukirchener Verlag, 2008, 7-38, esp. 11.

99

09. Gelardini.pdf 7 23/02/12 12.44

This silence about names17 bestows a sense of conspirative oppres-

sion upon the incident.18 Herod imprisoned John, as is reported, because

of his sister-in-law and niece Herodias (Mark 6,17), who wished to kill

the Baptist because he had criticized their unlawful marriage (cf. Lev

18,16). Herod could have avoided this situation had he learned from

the mistakes of his brother Archelaus, who had also transgressed the

laws of the fathers by marrying his brother’s wife Glaphyra (A.J.

17.341,350-352). But Herod, who esteemed John as a righteous and

holy man, protected him instead (Mark 6,18-20).

Herodias’s opportunity came on Herod’s birthday. While surrounded

by court officials, military, and Galilean nobility at a solemn banquet, Hero-

dias – as it seems – sends her daughter, against the customs for educated

baronial offsprings – to dance for the assembled dignitaries. Her dance

pleases Herod and his guests to that extent – an erotic-incestuous conno-

tation seems implied – that he swears to give her whatever she pleases,

indeed up to half of his kingdom (Mark 6,21-23).19 Ignorant of a wish

she asks her mother, and thereupon calls for John’s head. Against his bet-

ter judgment, Herod grants Herodias her wish because of the pledge he

uttered in the presence of the gathered guests (Mark 6,24-28).

In summary, Mark’s Herod identifies Jesus – possibly in the con-

text of an interrogation – as John the Baptist, whom he beheaded. The in-

terpretation of this information remains difficult. Should we read it as

an admission of guilt that he beheaded a divine favorite, or possibly as

implicit acknowledgment that this powerful Baptist redivivus, i.e. Je-

sus, could once again be endangered in his life? For his power would

stand in stark contrast to the weakness Herod exhibits in this account.

By no means is Herod the “kingly hero” that he wishes to be. Much

rather, he is the pitiable sport of fate, who is neither able to contain and

see through his wife’s fury, nor in command of his erotic inclination

towards the gal, nor indeed of his fear for his reputation in the presence

––––––––––––

17 Ingrid Kühn, “Decknamen – ein neues Untersuchungsgebiet”, in: Ernst Eichler et al.,

Namenforschung..., I, 515-20.

18 Elsa Tamez, “The Conflict in Mark: A Reading from the Armed Conflict in Colombia”,

in: Nicole Wilkinson Duran – Teresa Okure – Daniel Patte (eds.), Mark, Minneapolis, For-

tress Press, 2011, 101-25: Tamez convincingly points to the fact that silencing is an integral

part of suppression and armed conflicts.

19 Joanna Dewey, “The Gospel of Mark”, in: Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza (ed.), Search-

ing the Scriptures: A Feminist Commentary, 2 vols., London, SCM, 1995, II, 470-509, esp.

482-83; Monika Fander, “Das Evangelium nach Markus: Frauen als wahre Nachfolgerinnen

Jesu”, in: Schottroff Luise – Marie-Theres Wacker (eds.), Kompendium Feministische Bibel-

auslegung, Gütersloh, Kaiser, Gütersloher Verlagshaus, 19992, 499-512, esp. 503-04; Adela

Yarbro Collins, Mark: A Commentary, ed. by Harold W. Attridge, Minneapolis, Fortress, 2007,

309. Whereas Herod appears only weak, both Herodias and her daughter are portrayed as dis-

reputable women who are mainly responsible for the death of a just man. To discredit influ-

ential women as inadequate is a classic motif, which Josephus in view of Herodias has in

common with Mark (see 2.4).

100

09. Gelardini.pdf 8 23/02/12 12.44

of the dignitaries. Due to this weakness, he becomes accountable for an

execution devoid of a fair trial. Moreover, this crime bears all the hall-

marks of tragedy so aptly described by Aristotle: it is unrighteous, ar-

bitrary, and dreadful (Poetics).

4. Herod’s Political Life and Demise According to Other Sources

That it was Herod’s weakness – and not his strength – that drove him

to eliminate John is explicitly stated in Matt 14,5 and also in Josephus’s

account. In the latter’s narrative, Herod fears John’s great influence

over the people and guards himself against the Baptist’s possible incli-

nation to raise a rebellion by putting him to death as a measure of pre-

caution. Only secondarily is his marriage with Herodias linked to John

in that the people thought of his disastrous defeat against Aretas IV,

Nabatean king and father of Herod’s first and now repudiated wife, as

divine punishment for what he had done to John, and as a sign of God’s

displeasure with him (A.J. 18.116-119).

While neither Mark nor Josephus mention an encounter between

Herod and Jesus, such an event occurs in the Gospel according to Luke.

There the Pharisees come to Jesus in order to warn him about Herod’s

desire to kill him (Luke 13,31-33), notwithstanding that later in the nar-

rative he cannot find deeds that would justify Jesus’ death (Luke 23,6-

12.15-16).

One last account of Herod in Josephus deserves mention. This story

not only marks Herod’s demise, but it also shows that his claim for the

royal title stands as an inclusion, i.e. it stands at the beginning and end

of his reign that lasted for as long as forty-three years. Herodias’s broth-

er, Agrippa I, an extravagant and thus highly indebted bon viveur, pur-

posely sought Caligula’s company while residing in Rome, possibly

because Herod had become and remained friends with Tiberius all his

life (A.J. 18.36). This proved beneficial, because as soon as Caligula

took office, he released Agrippa from prison, where Tiberius had detain-

ed him, and gave him Philip’s tetrarchy, which had been under Syrian

control since his death in 33/34 C.E. Along with this, Caligula be-

stowed the royal title upon him, a move that greatly humiliated Herod,

as one may imagine.

Herod, encouraged by Herodias, once more embarked for Rome in

order to plea for the royal title. Agrippa heard about his intention, and

decided to send his freedman Fortunatus to Caligula with a complaint

against Herod. Agrippa bore a grudge against Herod for insulting him

while being entrusted to his care in Tiberias, a circumstance that had

forced Agrippa to flee. An earlier complaint related to this instance had

101

09. Gelardini.pdf 9 23/02/12 12.44

apparently not met with Tiberius’ favor (B.J. 2.178), but instead was deem-

ed an apt opportunity for revenge finally within his grasp. Fortunatus en-

joyed such a swift passage to Rome that he was able to hand over Agrip-

pa’s complaint to Caligula only very shortly after Herod’s arrival. Ag-

rippa’s letters accused Herod of being in league with the Parthian king

Artabanus in opposition to Caligula’s government. To substantiate this

allegation, he observed that Herod had armor sufficient for seventy thou-

sand men. Since Herod could not falsify this information about his weap-

onry, Caligula considered this proof of the accusation that Herod was

considering an insurgency. Rather than the royal title, Caligula impos-

ed eternal banishment upon Herod, and attached his domain to Agrip-

pa’s kingdom (A.J. 18.143-239). Herodias, while offered the opportunity

to be spared her husband’s calamity, decided to follow Herod to Lyons

(Lugdunum). Josephus concludes: «And thus did God punish [...] Herod

[...] for giving ear to the vain discourses of a woman» (B.J. 2.181-183;

A.J. 18.240-255).20

In summary, Mark’s portrayal of Herod as a humbled and thus weak –

yet nevertheless hazardous regent – is confirmed in Josephus’ accounts.21

It seems that Herod left nothing undone to aggrandize his power, and to

rid himself of everything that could jeopardize his ambitions. But what

goes around comes around, as modern parlance puts it.

Some claim that Caligula killed Herod, others believe that he died

in exile. Irrespective of his death, Herod, the «kingly hero of divine de-

scent», was cheated out of his royal title just as he had cheated his broth-

er Archelaus out of his, namely, by accusations brought forth through a

close relative. Secondly, Herod’s demise occurred for the same reason

as he had put John to death, namely, an imputed revolt. Herod’s dual as-

piration for the royal title induced him to violate earthly laws and re-

sulted in his dual rejection by the rulers of the world – i.e., Caesar as

well as God – and ultimately left him with nothing. Smola’s dictum –

one may conclude – assumed proverbial significance: «The name (title

included) is not everything, but without a good name everything is

nothing».

––––––––––––

Josephus, The Works of Flavius Josephus..., n.p.

20

Whether Herod was hazardous from historical perspective has been variously assessed.

21

For instance, whereas Jensen (Herod Antipas in Galilee..., 254) quite convincingly judges

him as a «minor, moderate, adjusted, and unremarkable ruler», Abraham Smith [“Tyranny Ex-

posed: Mark's Typological Characterization of Herod Antipas (Mark 6:14–29)”, Biblical In-

terpretation, 14/3 (2006) 259-93] and Peter-Ben Smit [“Eine neutestamentliche Geburtstags-

feier und die Charakterisierung des ‘Königs’ Herodes Antipas (Mk 6,21-29)”, Biblische Zeit-

schrift, 53/1 (2009) 29-46] regard him as a dangerous tyrant.

102

09. Gelardini.pdf 10 23/02/12 12.44

III. JESUS CHRIST

1. Jesus’ Titles and Names According to Mark

Just as with Herod, the royal (Mark 15,2.9.12.18.26.32) – in this

case messianic (Mark 1,1; 8,29; 9,41; 14,61; 15,32) – title stands both

at the beginning and at the end of Jesus’ life according to Mark. Unlike

Herod, Jesus’ heavenly father considers him worthy of this title by ap-

proving him as his one and only son, and thus as his heir (Mark 1,11;

9,7; 12,1-12). Unlike Herod, moreover, Jesus claims no authority over

“his” kingdom, but only over that pertaining to his father.

Unlike Herod, Jesus does not strive to replace his father, but instead

he is content with representing him. Consequently, an attempt to rid

himself of his praenomen “Iēsous”, which stands for Hebrew “Joshua”

and means «God helps, God is salvation»,22 is not apparent since the

name is used eighty-one times.23 Because of the meaning of his name,

for which the high priests ridiculed him in the light of his crucifixion

(Mark 15,31), Jesus does not act on the basis of his own power but on

his father’s power, i.e., God’s dynamis.

And finally, unlike Herod in the narrator’s surely ideal portrayal,

Jesus does not serve his own purposes, but instead those of the people,

which in turn are God’s.

2. Jesus’ Political Life and Demise According to Mark

Just as Herod, Jesus claims authority over the entire territory: un-

ambiguously in Judaea, more explicitly in Philip’s tetrarchy, and cau-

tiously in Galilee.

In each of these three dominions, Jesus heads directly towards its

power centers, Jerusalem on the one hand (Mark 11,11), Caesarea Phil-

ippi on the other (Mark 8,27), and finally the insinuated Sepphoris and

Tiberias. In each of these capitals, the quest for his identity is virulent

(Mark 6,14-16; 8,27-30; e.g. 11,7-10).

Herod’s capitals, as noted, are not mentioned explicitly,24 but im-

plicitly, for instance, when the narrator reports that Jesus goes to Naz-

––––––––––––

22 Gerhard Schneider, “Iēsous”, in: Balz–Schneider, Exegetisches Wörterbuch..., II, 440-

52, esp. 442-43; Hellmut Haug, “Jesus”, in: Haug, Namen und Orte der Bibel..., 190-93; Ru-

dolf Hoppe, “Jesus von Nazaret”, in: Josef Hainz – Martin Schmidl – Josef Sunckel (eds.),

Personenlexikon zum Neuen Testament, Düsseldorf, Patmos, 2004, 124-33.

23 Mark 1,1.9.14.17.24.25; 2,5.8.15.17.19; 3,7; 5,6.7.15.20.21.27.30.36; 6,4.30; 8,27; 9,2.

4.5.8.23.25.27.39; 10,5.14.18.21.23.24.27.29.32.38.39.42.472.49.50.51.52; 11,6.7.22.29.332; 2,

17.24.29.34.35; 13,2.5; 14,6.18.27.30.48.53.55.60.62.67.72; 15,1; 15,5.15.34.37.43; 16,6.8.

24 Zangenberg, “Jesus – Galiläa...”, 11.

103

09. Gelardini.pdf 11 23/02/12 12.44

areth, which is located only six kilometers – that is, 3,7 miles – south-

east of Sepphoris, to whose catchment area Nazareth belongs.

Jesus experiences rejection in Nazareth (Mark 6,1-6). Similar to

Herod’s kingly title, this narrative information might mirror historical

facts, since Sepphoris, on account of its rebels – e.g., Judas, son of

Hezekiah (B.J. 2.56; A.J. 17.271-272) – and its rebellion against Rome,

was captured, burnt down, and its habitants sold into slavery in the

year 4 B.C.E. by the Syrian legate Varus. Notably, these events oc-

curred while Herod and Archelaus were quarreling over the royal title

before the emperor. Upon his return as tetrarch, Herod rebuilt Seppho-

ris, fortified the town, and dedicated it as his capital to Augustus (B.J.

2.68; A.J. 17.289). Later he built the new capital Tiberias thirty kilo-

meters east of Sepphoris – that is, 18,6 miles – in honor of the succes-

sor on the throne. Sepphoris had learned from its traumatic experience

and remained loyal to Rome, even during the Jewish-Roman war, as it

welcomed both Cestius Gallus (B.J. 2.511) and Vespasian (B.J. 3.29-

34; Vita 38).

It is noticeable that Jesus seems to avoid a direct encounter with

Herod, and instead sends forth his disciples in the scene that frames the

pericope under investigation (Mark 6,7-13.30-32). This approach is nar-

ratively plausible, since firstly Jesus knows of John’s imprisonment

since his arrival in Galilee (Mark 1,14), and secondly he seems to iden-

tify himself in relation to Herod with the elected King David, who was

fleeing from the rejected King Saul in Mark 2,25-26. This is thirdly

confirmed when the narrator reports that the Pharisees seek to kill him

together with the Herodians (Mark 3,6), so that fourthly Jesus deems it

necessary to explicitly warn his disciples about Herod (Mark 8,15),

whereas fifthly Jesus does not want anyone to know when he and his

disciples pass through Galilee for the last time (Mark 9,30-32).

Luke 23,6 draws an even more precise picture in stating that Jesus

belongs to the territory of Herod, where the latter was legally granted

the ius gladii, the power over death and life. Given Jesus’ specific mes-

sianic claim, dying in Galilee would have meant to die prematurely and

prior to achieving his mission in Jerusalem, as Luke 13,33 explicitly

states.

Just as the narrative Herod does in Mark 6,14-16, the narrator es-

tablishes a strong link between John and Jesus, particularly in regard to

their demises; thus, there are numerous parallels between Mark 6,17-

29 and Mark 15,6-15:

- The wrongdoer in Jerusalem is Pilate, who, according to Luke’s ac-

count, became – although originally his foe – friends with Herod

through Jesus (Luke 23,12). Just as Herod is only tetrarch, Pi-

late is only proconsul.

104

09. Gelardini.pdf 12 23/02/12 12.44

- While John’s verdict over his claim to represent the law was

deemed lèse-majesty, Jesus’ royal claim was deemed a political

offence.

- While John was killed on the ruler’s birthday without a trial,

Jesus is killed on Pessach following a mock trial.

- Like Herod, Pilate is benevolent towards his prominent pris-

oner.

- Like Herod lent the gal his ear, so does Pilate lend his to the

people.

- Just as the gal listens to her mother, so do the people listen to

the high priests.

- Just as the gal opted for John’s death, so do the people opt for

Jesus’ death.

- Just as Herod felt bound by his oaths, so does Pilate bound by

his amnesty.

- And just as Herod was portrayed as a victim of his own weak-

ness, so, too, is Pilate.

- Further, just as Herod’s claim for the royal title was criminal-

ized and punished by the world’s ruler, so is Jesus punished by

his representative Pilate, who in turn will be banished like his

friend Herod (A.J. 18.89).

- And just as the narrator ridicules Herod’s claim, so do the tem-

ple elites ridicule Jesus’.

IV. CONCLUSION

In conclusion, it is comprehensible that the aspiring “king” Herod

is unable to recognize the one that the narrator perceives as the legiti-

mate king. But it is exactly this failure that spares Jesus’ life in Galilee.

It is precisely this circumstance that paves the way for Jesus to intro-

duce and prove himself in a first attempt to the entire kingdom as God’s

chosen and future king for the difficult times to come.

In no less than four instances Jesus announces his second return in

power – an event situated beyond narrative time (Mark 8,38; 9,1; 13,26;

14,61) and that possibly refers to the looming Jewish-Roman war.25

––––––––––––

25 Most scholars relate the Gospel in one way or the other to the Jewish-Roman war,

which lasted from 66 to 74 C.E. A dating prior to the temple’s destruction is claimed by Peter

105

09. Gelardini.pdf 13 23/02/12 12.44

According to the narrator, the Messiah’s return will not occur in order

to reclaim authority – as in the case of Herod – but in order to execute

it. The starting point for this victorious campaign will once again be

Galilee, from where Herod – for once the kingmaker – will have long

been swept away (Mark 14,28; 16,7).26 For this reason, the author may

have entitled his narrative with the beginning of the euangelion, the

news about the victory of this Messiah (Mark 1,1), one whose messiah-

ship he possibly redefines over against the numerous messianic pretend-

ers in the forefront of and during a disastrous war.27

I return in closing to Smola’s dictum, albeit with a variation: «The

name (title included) is not everything, but with a good name nothing be-

comes everything».

Gabriella Gelardini

Faculty of Theology

University of Basel

Nadelberg 10

CH-4051 Basel

Switzerland

gabriella.gelardini@unibas.ch

––––––––––––

Dschulnigg, Das Markusevangelium (ThKNT, 2), Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 2007, 56: between

64 and 66 C.E.; William L. Lane, The Gospel According to Mark: The English Text with In-

troduction, Exposition, and Notes (NICNT), Grand Rapids, Eerdmans, 1974, 21: between 60

and 70 C.E.; Collins, Mark..., 14: before 70 C.E. And a dating after the temple’s destruction

is argued for by Joachim Gnilka, Das Evangelium nach Markus, 2 vols. (EKK, 2), Zurich,

Benziger and Neukirchen-Vluyn, Neukirchener, 1978-1979), I, 34: between 70 and 73 C.E.

26 Narratively speaking, the starting point is thus not that Jesus came because of Herod

Antipas, which Morten Hørning Jensen (“Herodes Antipas in Galiläa”, in: Claußen–Frey,

Jesus und die Archäologie..., 39-73) dismisses on the basis of historical evidence, but rather

vice versa, namely, that Herod came and failed because of Jesus.

27 Cf. Collins, Mark..., 102; Martin Ebner – Stefan Schreiber (eds.), Einleitung in das

Neue Testament (Studienbücher Theologie, 6), Stuttgart, Kohlhammer, 2008, 175-80.

106

09. Gelardini.pdf 14 23/02/12 12.44

You might also like

- Hans K. LaRondelle - The Etymology of Har-Magedon (Rev 16,16)Document5 pagesHans K. LaRondelle - The Etymology of Har-Magedon (Rev 16,16)Eliane Barbosa do Prado Lima RodriguesNo ratings yet

- The Interpretation of Parables: Exploring "Imaginary Gardens With Real Toads"Document15 pagesThe Interpretation of Parables: Exploring "Imaginary Gardens With Real Toads"Lijo DevadhasNo ratings yet

- I Am That I Am PDFDocument16 pagesI Am That I Am PDFAlvaro Martinez100% (1)

- The Battle of Gog and MagogDocument30 pagesThe Battle of Gog and MagogAnonymous gtMsV5O6zH0% (1)

- Parable of The SowerDocument19 pagesParable of The Sower31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of The Book of EstherDocument13 pagesSynopsis of The Book of EstherTomasz Krazek100% (1)

- John P. Meier (2000) - The Historical Jesus and The Historical Herodians. Journal of Biblical Literature 119.4, Pp. 740-746Document8 pagesJohn P. Meier (2000) - The Historical Jesus and The Historical Herodians. Journal of Biblical Literature 119.4, Pp. 740-746Olestar 2023-06-22No ratings yet

- RS-2-I-Titles-and-Images-of-Jesus-Version-2 - WPS PDF Convert PDFDocument74 pagesRS-2-I-Titles-and-Images-of-Jesus-Version-2 - WPS PDF Convert PDFCharles Kim ManongdoNo ratings yet

- Moses The Magician: Gary A. RendsburgDocument16 pagesMoses The Magician: Gary A. RendsburgMehmet KusakNo ratings yet

- Moses The Magician: Gary A. RendsburgDocument16 pagesMoses The Magician: Gary A. RendsburgMehmet KusakNo ratings yet

- Study On ObadiahDocument20 pagesStudy On ObadiahKenneth KhooNo ratings yet

- A Modified Swadesh ListDocument19 pagesA Modified Swadesh ListRichter, JoannesNo ratings yet

- Dominion and Dynasty: Book ReviewDocument6 pagesDominion and Dynasty: Book Reviewboverman3042100% (1)

- Christological Titles in The New TestamentDocument10 pagesChristological Titles in The New TestamentKevin Rey CaballedaNo ratings yet

- Messianic Motifs in The Scriptures UpdatedDocument16 pagesMessianic Motifs in The Scriptures UpdatedBusayomi AladesidaNo ratings yet

- Exegesis Mk12 RevisedDocument8 pagesExegesis Mk12 RevisedyapbengchuanNo ratings yet

- Divine Insinuation in The 'Panegyrici Latini'Document37 pagesDivine Insinuation in The 'Panegyrici Latini'hNo ratings yet

- Terjemahan PB MatiusDocument11 pagesTerjemahan PB Matiusabraham pakpahanNo ratings yet

- Malbon Review of Broadhead - Mark CommentaryDocument4 pagesMalbon Review of Broadhead - Mark CommentaryMike WhitentonNo ratings yet

- He Enre of The Riestly Lessing: Ofnumbers (Eds. C. FDocument21 pagesHe Enre of The Riestly Lessing: Ofnumbers (Eds. C. FWilian CardosoNo ratings yet

- Messianic Movements 1st CentDocument28 pagesMessianic Movements 1st CentFernando HutahaeanNo ratings yet

- 1 2 Kings A CommentaryDocument44 pages1 2 Kings A CommentaryAnthony George100% (1)

- Jude and Ot - AspDocument17 pagesJude and Ot - Asplundc9603No ratings yet

- JOSHUAS OF HEBREWS 3 AND 4 Bryan J WhitfieldDocument16 pagesJOSHUAS OF HEBREWS 3 AND 4 Bryan J WhitfieldRichard Mayer Macedo SierraNo ratings yet

- WƎ Ni Daq Qó Eš "Then Shall The Sanctuary Be Granted Justice."Document23 pagesWƎ Ni Daq Qó Eš "Then Shall The Sanctuary Be Granted Justice."Gabriel AdamNo ratings yet

- Hubert Critical Approach PaperDocument6 pagesHubert Critical Approach PaperAgustinNo ratings yet

- WHEELER - Sing, Muse The Introit From Homer To ApolloniusDocument18 pagesWHEELER - Sing, Muse The Introit From Homer To ApolloniusÍvina GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Bohak, Mystical Texts, Magic, and Divination (In The DSS)Document11 pagesBohak, Mystical Texts, Magic, and Divination (In The DSS)gbohakNo ratings yet

- 3.sons of SethDocument24 pages3.sons of SethmarcaurelioperseuNo ratings yet

- Reading Translation Divine Name in MT LXX RoselDocument19 pagesReading Translation Divine Name in MT LXX RoselTaviNo ratings yet

- Dularidze T. The Institution of Envoys With Homer - Origin of Diplomacy in Antiquity. 2011Document7 pagesDularidze T. The Institution of Envoys With Homer - Origin of Diplomacy in Antiquity. 2011Nikoloz NikolozishviliNo ratings yet

- The Names and Epithets of The DagdaDocument9 pagesThe Names and Epithets of The Dagdaincoldhellinthicket100% (1)

- A Commentary On The Epistles of Peter and Jude, BNTC (Reprint, Grand RapidsDocument4 pagesA Commentary On The Epistles of Peter and Jude, BNTC (Reprint, Grand RapidsNikola PapNo ratings yet

- A Pardes Reading of The Gospel AccordingDocument147 pagesA Pardes Reading of The Gospel AccordingJorgeYehezkelNo ratings yet

- Redditt KingDocument21 pagesRedditt KingprophetminalumNo ratings yet

- Ben Blackwell, Immortal Glory and The Problem of Death in RM 3,23Document24 pagesBen Blackwell, Immortal Glory and The Problem of Death in RM 3,23robert guimaraesNo ratings yet

- 31 - Obadiah PDFDocument26 pages31 - Obadiah PDFGuZsolNo ratings yet

- Female Pillar Figurines of The Iron Age: A Study I N Text and ArtifactDocument27 pagesFemale Pillar Figurines of The Iron Age: A Study I N Text and Artifactvalia1No ratings yet

- Pages From Koester-2020-The Oxford Handbook of The Book o PDFDocument17 pagesPages From Koester-2020-The Oxford Handbook of The Book o PDFtaras_bNo ratings yet

- The Battle of ArmageddonDocument10 pagesThe Battle of ArmageddonIsaque ResendeNo ratings yet

- A Critical and Exegetical Commentary On The Book of ProverbsDocument21 pagesA Critical and Exegetical Commentary On The Book of ProverbsAll-in-Fishing100% (1)

- Zechariah 11 and The Eschatological Shep PDFDocument38 pagesZechariah 11 and The Eschatological Shep PDFDelvon TaylorNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Sommer, A Commentary On Psalm 24Document22 pagesBenjamin Sommer, A Commentary On Psalm 24stelianpascatusaNo ratings yet

- Brenk (2011) Hierosolyma. The Greek Name of JerusalemDocument23 pagesBrenk (2011) Hierosolyma. The Greek Name of JerusalemJonathan Schabbi100% (1)

- Controversial Distinction in Jesus TeachingDocument23 pagesControversial Distinction in Jesus Teaching31songofjoyNo ratings yet

- The Deuteronomistic HistoryDocument7 pagesThe Deuteronomistic Historyxi liNo ratings yet

- Darius The MedeDocument23 pagesDarius The MedebaguenaraNo ratings yet

- The Commentary On The Book of Ruth by Claudius of Turin by I. M. DOUGLASDocument26 pagesThe Commentary On The Book of Ruth by Claudius of Turin by I. M. DOUGLASneddyteddyNo ratings yet

- Paul Evans Bakhtin 2008Document24 pagesPaul Evans Bakhtin 2008Abu MuawiyahNo ratings yet

- The Lucan Christ and Jerusalem - τελειοῦμαι (Lk 13,32) - J Duncan M. DerretDocument8 pagesThe Lucan Christ and Jerusalem - τελειοῦμαι (Lk 13,32) - J Duncan M. DerretDolores MonteroNo ratings yet

- Exegesis of Luke 13:31-35 "As A Mother Hen... "Document16 pagesExegesis of Luke 13:31-35 "As A Mother Hen... "bruddalarryNo ratings yet

- DeuteronomyDocument137 pagesDeuteronomymarfosdNo ratings yet

- Demonology 32893204Document6 pagesDemonology 32893204Mike LeeNo ratings yet

- 1999 EmertonDocument24 pages1999 Emertonmeaningiseverything meaningiseverythingNo ratings yet

- ChinaDocument47 pagesChinaPeter Salemi100% (1)

- Theo1 NotesDocument17 pagesTheo1 NotesKhemgee EspedosaNo ratings yet

- FinalDocument5 pagesFinalJustine CailingNo ratings yet

- Deuteronomy- Everyman's Bible CommentaryFrom EverandDeuteronomy- Everyman's Bible CommentaryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Lab L-2 CinCar SatelliteDocument2 pagesLab L-2 CinCar SatelliteJack WestNo ratings yet

- Frangold Real Estate Budget - Assignment 2Document3 pagesFrangold Real Estate Budget - Assignment 2Jack WestNo ratings yet

- SC EX 2 Klapore WESTDocument2 pagesSC EX 2 Klapore WESTJack WestNo ratings yet

- Lab 3-1 Adaptive Solutions Online Eight-Year Financial Projection - WilliamsDocument2 pagesLab 3-1 Adaptive Solutions Online Eight-Year Financial Projection - WilliamsJack WestNo ratings yet

- SC EX 1 DeltonDocument3 pagesSC EX 1 DeltonJack WestNo ratings yet

- Monarchy Scavenger HuntDocument3 pagesMonarchy Scavenger HuntJemuel CuramengNo ratings yet

- Accountability Self AssessmentDocument1 pageAccountability Self AssessmentReizel Jane PascuaNo ratings yet

- N° DatosDocument15 pagesN° Datossarah mezaNo ratings yet

- Michelangelo - Painter, Sculptor, and ArchitectDocument154 pagesMichelangelo - Painter, Sculptor, and Architectandrejcenko67% (3)

- Cbse Roll NoDocument6 pagesCbse Roll Noapi-19730754No ratings yet

- JCE-61-2009-03-05 - Ždrelac - Građevinar PDFDocument9 pagesJCE-61-2009-03-05 - Ždrelac - Građevinar PDFMilena KatičinNo ratings yet

- Mughal SubahdarsDocument9 pagesMughal Subahdarssohamtube40No ratings yet

- If Cartoon Is Primarily Based On A Principle of StereotypeDocument2 pagesIf Cartoon Is Primarily Based On A Principle of Stereotypenameisnahid19No ratings yet

- FI52Document9 pagesFI52DELTANETO SLIMANENo ratings yet

- I Will Survive Trumpet in BBDocument2 pagesI Will Survive Trumpet in BBDejair RodolfiNo ratings yet

- 1586 5555 1 PB PDFDocument17 pages1586 5555 1 PB PDFJomel Sotea AladoNo ratings yet

- Ctesias IndikaDocument252 pagesCtesias IndikaBenne Dose100% (2)

- Jesus The MessiahDocument5 pagesJesus The MessiahTuTuTajNo ratings yet

- Architecture PowerPointDocument45 pagesArchitecture PowerPointEzra El AngusNo ratings yet

- A Presentation of Rizal S Childhood LifeDocument13 pagesA Presentation of Rizal S Childhood LifeRico Badilla100% (3)

- Credit, Markets The Agrarian Economy of Colonial India: Sugata BoseDocument340 pagesCredit, Markets The Agrarian Economy of Colonial India: Sugata BoseANJALI0% (1)

- Chuyên Sâu Tiếng Anh 4Document146 pagesChuyên Sâu Tiếng Anh 4Hà VươngNo ratings yet

- Fall 2021 NSE 211 Lab Schedule (Updated Sept 7th 2021)Document9 pagesFall 2021 NSE 211 Lab Schedule (Updated Sept 7th 2021)Saad QureshiNo ratings yet

- L396 PDFDocument458 pagesL396 PDFWessel van DamNo ratings yet

- Information To Users: University InternationalDocument221 pagesInformation To Users: University InternationalDüzce SinemaNo ratings yet

- MQM VS Government Reply by GovernmentDocument75 pagesMQM VS Government Reply by GovernmentSani Panhwar100% (3)

- The Golden Compasses The History of The House of Plantin-Moretus - Leon VoetDocument1,502 pagesThe Golden Compasses The History of The House of Plantin-Moretus - Leon VoetLance Kirby100% (2)

- Harry Potter DetailsDocument3 pagesHarry Potter Detailscalvin.bloodaxe4478No ratings yet

- Shakespeare MonologuesDocument18 pagesShakespeare MonologuesRobert WagnerNo ratings yet

- English ProjectDocument6 pagesEnglish ProjectTaneesha RathiNo ratings yet

- Thomas SankaraDocument7 pagesThomas SankaraKarisMN100% (2)

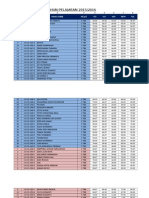

- Rekap Nilai Uts 2015 - 2016Document252 pagesRekap Nilai Uts 2015 - 2016muyunscribdNo ratings yet

- Cards (Character)Document4 pagesCards (Character)ZiaNo ratings yet

- Ya Rasool AllahDocument10 pagesYa Rasool AllahEhteshamNo ratings yet

- National Artists of The PhilippinesDocument133 pagesNational Artists of The PhilippinesKaila Enolpe100% (1)