Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dosing Botanical Medicines - Eric Yarnell

Uploaded by

boob bobsonnnCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dosing Botanical Medicines - Eric Yarnell

Uploaded by

boob bobsonnnCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/7667607

Dosing Botanical Medicines

Article in Journal of Herbal Pharmacotherapy · February 2005

DOI: 10.1300/J157v05n01_08 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

2 2,321

1 author:

Eric Yarnell

Bastyr University

184 PUBLICATIONS 1,508 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Artemisia absinthium review View project

Natural Approach to Urology and Men's Health 2nd Ed View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Eric Yarnell on 30 August 2017.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQ)

K. P. Khalsa, Column Editor

Dosing Botanical Medicines

Eric Yarnell, ND, RH (AHG)

Therapeutic effects in herbal medicine depend on proper dosing.

With few exceptions, traditional medical systems tend to recommend

what are considered large or physiologic doses (several grams daily of

safe herbs). Many modern botanical systems, particularly those that

arose in Europe, tend to use similarly large doses. This article will fo-

cus on crude herbs and extracts in wide use, but will not address spe-

cific standardized extracts or other dose forms that have not been used

in traditional medicine and require clinical trials to determine specific

optimal doses.

However, there has been a tendency, particularly in North Amer-

ica, toward lower doses. For example, health food stores generally

sell only 1 oz bottles of herbal tinctures, enough for only 1-2 days use

at physiologic doses. The economic basis of this situation is apparent

but still unacceptable. Clinicians looking to prescribe herbs effec-

tively must not get caught in the 1 oz bottle trap. This article deals

only with the dosing of generally safe herbs. Herbs with known toxic

effects must be dosed on an individual basis and are not discussed

here.

Eric Yarnell is affiliated with the Bastyr University, Department of Botanical Medi-

cine, 6300 Ninth Avenue, NE, Suite 362, Seattle, WA 98115 (E-mail: dryarnell@

earthlink.net).

Journal of Herbal Pharmacotherapy, Vol. 5(1) 2005

Available online at http://www.haworthpress.com/web/JHP

© 2005 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.

Digital Object Identifier:10.1300/J157v05n01_08 73

74 JOURNAL OF HERBAL PHARMACOTHERAPY

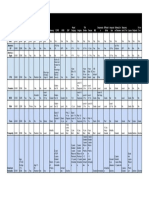

TABLE 1. Traditional Chinese Medicine Doses for Tonic Herbs

Latin name Typical Equivalent Equivalent

(common name) recommended tincture tincture

part daily dose daily dose (1:2)* daily dose (1:5)

Angelica sinensis 3-15 g 6-30 ml 15-75 ml

(dang gui) root

Astragalus 9-30 g (up to 60 g 18-60 ml 45-150 ml (up to 300

membranaceus occasionally) ml)

(huang qi) root

Codonopsis pilulosa 6-30 g 12-60 ml 30-150 ml

(dang shen) root

Glycyrrhiza uralensis 2-12 g (use of this 4-24 ml 10-60 ml

(gan cao, licorice) dose continuously for

root several weeks can

cause pseudohy

peraldosteronism)

Panax ginseng 1-10 g chronic (up to 2-20 ml (up to 60 ml) 5-50 ml (up to 150

(Asian ginseng) root 30 g acutely) ml)

Paeonia lactiflora 6-15 g (up to 30 g 12-30 ml (up to 60 30-75 ml (up to 150

(white peony, bai occasionally) ml) ml)

shao) root

Polygonum 9-30 g 18-60 ml 45-150 ml

multiflorum (fo-ti, he

shou wu) root

Rehmannia glutinosa 9-30 g 18-60 ml 45-150 ml

(shu di huang) root

Zizyphus jujuba 10-30 g 20-60 ml 50-150 ml

(jujube) fruit

* Ratios refer to the weight of raw material to volume of solvent used to make the tincture. Thus a 1:2 tinc-

ture contains the extract of 500 mg herb per 1 ml.

Traditional Chinese medicine is arguably one of the oldest systems

that employees herbs heavily and that has a written history extending

back many millennia. Thus one can look to this system for some sense

of what typical doses for safe botanicals should be. Daily doses of

some common tonic herbs according to two respected sources on tra-

ditional Chinese herbal medicine are given in Table 1, along with

equivalent tincture doses.1,2

The transmission of doses from ancient times to today in western

herbal medicine has been fragmented at best, and thus one cannot refer

to a 5,000-year-old history of dosing as easily. Nevertheless, there is no

reason to assume that doses of western tonic herbs should be any differ-

ent than that of Chinese tonic herbs.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) 75

BASIC CHRONIC DOSING RECOMMENDATIONS

At a minimum, this author recommends administering 5-10 g daily in

divided doses of any nontoxic herb used as a “simple,” meaning it is

given by itself. Translated to tincture doses, this means 10-20 ml daily

of a 1:2 tincture and 25-50 ml daily of a 1:5 tincture. Very often, 5 ml

(one measuring teaspoon) is recommended three times daily, which will

underdose herbs in dilute tinctures (1:5) but provide a good dose of

those in concentrated tinctures (1:2) or fluid extracts (1:1). For this rea-

son, the author avoids 1:5 tinctures as much as possible, as it is difficult

to provide sufficient dose economically.

The dose form in which herbs are delivered must always be consid-

ered, as quantity and quality both matter. Powdered herbs are generally

cheaper than tinctures. However, they have a much shorter shelf life

(6-12 months maximum, compared to at least 10 years for tinctures)

given their enormous surface area and lack of preservatives. Though

easy to take if simply mixed into water or other liquids, they can become

problematic to swallow if used as capsules, which can hold 500-750 mg

in the largest sizes. Tinctures and powders can both be objectionable

taste-wise, whereas capsules tend to mask flavor. Crude herbs can also

be made into infusions and decoctions. The dose recommendations are

the same as powders. Crude herbs have longer shelf-lives than powders

as they have not been ground. Flavor is often a serious issue, as well as

preparation time. The addition of water delivered by teas can be thera-

peutically valuable in some situations.

Ultimately the quality of the raw material is crucial in efficacy of the

final extract or dose form. A huge amount of very low quality herb will

have no effect compared to small amounts of very high quality herb.

Much effort is going into attempting to quantify quality of herbs, a de-

bate that is beyond the scope of this article.

The use of multiple daily doses cannot be overly emphasized. Though

patients often find it difficult to take a dose in the middle of their work

or school day, it is imperative that they do so. Part of what makes herbs

so safe is that the body is efficient at clearing most botanical constitu-

ents. It is presumed that the half-lives of most herbal constituents are

3-4 hours, though there is little research in this area and some studies

have shown they can be substantially longer.3,4 If a patient takes only

one or two doses daily of most herbs, they may have negligible blood

levels in the middle of the day and lose many of the benefits of the herbs.

It must always be remembered that individuals may have different met-

abolic capacities and thus doses must be tailored to the individual.5

76 JOURNAL OF HERBAL PHARMACOTHERAPY

Intrarectal administration of botanicals by enema or suppository

should also be considered. It is estimated that approximately 30% of

constituents delivered per rectum bypass first pass hepatic metabolism,

thus increasing half-life and overall potency. This benefit may be over-

come by relatively poor absorption from the rectum. It is recommended

that usual oral doses be used as a starting point for intrarectal dosing,

though probably 10-20% lower doses will still be effective. This route

of administration is particularly indicated when patients are nauseated

or unable to swallow medicines. Much work remains to determine

optimal intrarectal doses of herbs.

BASIC ACUTE DOSING RECOMMENDATIONS

When a patient has an acute condition, dose requirements of herbs go

up to around 10-30 g daily (Table 2). Instead of taking larger doses,

more frequent dosing is preferable to insure continuous blood levels of

therapeutic constituents are maintained. Of a 1:2 tincture, the typical

recommendation is to take 5 ml six to eight times daily. It must also be

remembered that with oral dosing, it can take an hour or more after in-

take before blood levels begin to rise and physiological effects are

noticed.

THE SYNERGY CONUNDRUM

Many sophisticated botanical practitioners do not use simples, but in-

stead formulate many herbs together. This is certainly true of the most

advanced and well-documented traditional herbal systems from Asia

(China, Southeast Asia, India). It quickly becomes impractical to ad-

minister the full dose of each herb in a formula. If one gives just five

herbs, the patient is looking at consuming 50-100 g of herbs a day,

which is too expensive and unpalatable for almost all.

Instead, the total dose of the formula is generally about the same as

the dose for any single herb. It is believed that although the absolute

doses of each herb in the formula are below normal therapeutic levels,

the synergistic and/or additive effects among the herbs still makes the

formula effective. It is difficult to understand otherwise how formulas

with 10⫹ herbs can be found to be effective in double-blind, pla-

cebo-controlled trials, given than the dose of any one herb in the for-

mula is < 1 g daily unless synergy occurs.6

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) 77

The usual chronic adult dose of most crude herbal formulae is 5-10 g

daily. For acute situations this rises to 10-30 g.

CONFLICTS BETWEEN DOSE RECOMMENDATIONS

The doses recommended by various authoritative texts on herbal

medicine vary widely, leading to confusion in practice and concern

among medical practitioners familiar with the apparent uniformity of

drug dosing. The example of Echinacea spp. will highlight the wide

range of recommendations.

Thus in Melchart et al.’s10 clinical trial, they were using 3-10% the dose

recommended by Mills and Bone8 or Yarnell et al.7 Not surprisingly, the

Melchart et al.’s,10 clinical trial reported a lack of efficacy, though the pos-

sibility that the extremely low dose caused the failure was barely even con-

sidered. Low doses are seen in almost every clinical trial of echinacea.

This author suggests that dose recommendations be considered in

light of traditional dose ranges discussed above and clinical trial data. It is

very difficult to evaluate the relevance of recommendations outside these

ranges from single practitioners claiming efficacy, because regression to

the mean and other factors could just as easily explain the perceived bene-

fit of very low doses of herbs. The statistical controls in clinical trials and

the sheer accumulated mass of thousands of years of traditional practice

are much better at counteracting subjectivity. Nevertheless, it is clear that

a research agenda is needed to determine what are truly effective doses

for crude herb products given their widespread use.

CONCLUSION

Dosing traditional herbal medicines has been largely neglected, though

it is of pivotal importance. Scientific research on crude herbs should al-

TABLE 2. Differing Acute Echinacea spp. Dosing Recommendations

Reference Recommended adult Recommended Equivalent daily

daily dose* preparation raw material

7 30-60 ml 1:3 tincture 9-18 g

8 10-30 ml 1:2 tincture 5-15 g

9 4.5-9 ml (90-180 drops) 1:5 tincture 0.9-1.8 g

10 5 ml (100 drops) 1:11 tincture 0.45 g

78 JOURNAL OF HERBAL PHARMACOTHERAPY

ways include a component to determine optimal dosing. The author’s

experience is that insufficient dosing is a common cause of apparent

therapeutic failure of herbal medicines, and that those trends that rec-

ommend low doses are doing a disservice to their patients. Based on the

accumulated experience over thousands of years of use of herbs in

China and India, higher doses are most often associated with efficacy of

herbal medicines.

REFERENCES

1. Bensky D, Gamble A, Kaptchuk T. Chinese herbal medicine materia medica

(revised edition). Seattle: Eastland Press, 1993.

2. Chen JK, Chen TT. Chinese medical herbology and pharmacology. City of In-

dustry, CA: Art of Medicine Press, 2004.

3. De Smet PAGM, Brouwers JRBJ. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of herbal

remedies: basic introduction, applicability, current status and regulatory needs. Clin.

Pharmacokinet. 1997;32:427-36.

4. Brockmöller J, Reum T, Bauer S, et al. Hypericin and pseudohypericin: pharma-

cokinetics and effects on photosensitivity in humans. Pharmacopsychiatr. 1997;30

(suppl 2):94-101.

5. Li C, Homma M, Oka K. Characteristics of delayed excretion of flavonoids in

human urine after administration of shosaiko-to, a herbal medicine. Biol. Pharm. Bull.

1998;21:1251-7.

6. Hirayama C, Okumura M, Tanikawa K, et al. A multicenter randomized con-

trolled clinical trial of shosaiko-to in chronic active hepatitis. Gastroenterol. Jpn.

1989;24:715-

7. Yarnell E, Abascal K, Hooper K. Clinical botanical medicine. New York: Mary

Ann Liebert Inc., 2003.

8. Mills S, Bone K. Principles and practice of phytotherapy: Modern herbal medi-

cine. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

9. Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A, et al. (eds). The Complete German

commission E monographs: Therapeutic guide to herbal medicines, Austin: American

Botanical Council and Boston: Integrative Medicine Communications, 1998.

10. Melchart D, Walther E, Linde K, et al. Echinacea root extracts for the preven-

tion of upper respiratory tract infections: A double-blind, placebo-controlled random-

ized trial. Arch. Fam. Med. 1998;7:541-5.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Classical Pearls - Natur Terapi - Behandla - GuDocument89 pagesClassical Pearls - Natur Terapi - Behandla - Gufriend717No ratings yet

- Alternative Health & Herbs Remedies 425 Jackson SE, Albany, OR 97321 1-541-791-8400Document159 pagesAlternative Health & Herbs Remedies 425 Jackson SE, Albany, OR 97321 1-541-791-8400Marvin T Verna100% (2)

- HerbalsDocument3 pagesHerbalsJewn BergsteinNo ratings yet

- Gynura PrecumbensDocument4 pagesGynura PrecumbenslololololololoolololNo ratings yet

- Growing Herbs For HomeDocument8 pagesGrowing Herbs For HomeTomsondealNo ratings yet

- Urtica Dioica Urtica Urens (Nettle) : MonographDocument5 pagesUrtica Dioica Urtica Urens (Nettle) : Monographرمضان كريم100% (1)

- 1 PDF Herbal Dosing For Adults and ChildrenDocument8 pages1 PDF Herbal Dosing For Adults and Childrenxixoh97200No ratings yet

- TheHerbs PDFDocument128 pagesTheHerbs PDFIma6_100% (2)

- Best of The Best HerbsDocument128 pagesBest of The Best HerbsDil Nagar100% (4)

- Medicinal Uses For Herbal Teas: Evidence, Dosing, and Preparation MethodsDocument7 pagesMedicinal Uses For Herbal Teas: Evidence, Dosing, and Preparation MethodsJose Ph YuNo ratings yet

- CancerDocument1 pageCanceresivaks2000No ratings yet

- Herbal Cleanses OnlineDocument8 pagesHerbal Cleanses OnlineKhalid IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Aiki Dit Da JowDocument8 pagesAiki Dit Da Jowkosen58No ratings yet

- Ashwagandha DosageDocument6 pagesAshwagandha Dosagenvenkatesh485No ratings yet

- Description: Astragalus Family, Astragalus Membranaceus Is The Sole Medicinal Type. The Plant Is Found OnlyDocument8 pagesDescription: Astragalus Family, Astragalus Membranaceus Is The Sole Medicinal Type. The Plant Is Found Onlysdamo_darNo ratings yet

- Tsaang GubatDocument23 pagesTsaang GubatAngelica Magahis SuneNo ratings yet

- Hibiscus SabdariffaDocument6 pagesHibiscus SabdariffaShashikant DrShashikant BagadeNo ratings yet

- Taleb 2015Document5 pagesTaleb 2015skkbd415No ratings yet

- Chinese Herbal MedicineDocument4 pagesChinese Herbal Medicineapi-319505742No ratings yet

- Herbs of Sanpete County Feb 2017 EditionDocument106 pagesHerbs of Sanpete County Feb 2017 EditionKip PrisbreyNo ratings yet

- Blessed Thistle and Blue VervainDocument4 pagesBlessed Thistle and Blue VervainSoror OnyxNo ratings yet

- Using Herbs For Support When Transitioning Off Psychiatric MedicationDocument4 pagesUsing Herbs For Support When Transitioning Off Psychiatric MedicationMelissa NorthNo ratings yet

- What Is Herbal MedicineDocument6 pagesWhat Is Herbal MedicineNiere UmadhayNo ratings yet

- Medicinal Plants and Their Traditional Uses: ArticleDocument6 pagesMedicinal Plants and Their Traditional Uses: ArticleMuhammadimran AliNo ratings yet

- Veterinary PhytotherapyDocument2 pagesVeterinary PhytotherapyConstanza Ruiz0% (1)

- ContinueDocument2 pagesContinueGroot 0786No ratings yet

- Infertility Chinese HerbsDocument5 pagesInfertility Chinese Herbsxman17No ratings yet

- Uji Efek Analgetik Infusa Daun Beluntas (Mencit Jantan Galur SwissDocument7 pagesUji Efek Analgetik Infusa Daun Beluntas (Mencit Jantan Galur SwissBerliana Via AnggeliNo ratings yet

- 2008 - Science AsiaDocument5 pages2008 - Science Asiabakru248326No ratings yet

- For Emergency Use The Top 10 Herbs 2003+Document8 pagesFor Emergency Use The Top 10 Herbs 2003+emily fisherNo ratings yet

- Lactones, Polyketides As Neurotoxin in Oncogenic Genins of Soursop: A Holistic MiracleDocument9 pagesLactones, Polyketides As Neurotoxin in Oncogenic Genins of Soursop: A Holistic MiracleRebeca MaciasNo ratings yet

- Sheep and HerbsDocument4 pagesSheep and HerbsPerpetua KamikadzeNo ratings yet

- List of Adaptogens, and What These Adaptogenic Herbs Can Do For You - Gardening ChannelDocument9 pagesList of Adaptogens, and What These Adaptogenic Herbs Can Do For You - Gardening ChannelJoshNo ratings yet

- HahayysDocument30 pagesHahayys2BGrp3Plaza, Anna MaeNo ratings yet

- Cancer Treatment With Soursop LeafDocument4 pagesCancer Treatment With Soursop LeafSueEverethNo ratings yet

- Philippine Traditional and Alternative MedicineDocument4 pagesPhilippine Traditional and Alternative MedicineButchay LumbabNo ratings yet

- Mphil Bio-Chemistry ProjectDocument98 pagesMphil Bio-Chemistry ProjectBalaji Rao NNo ratings yet

- Medical PlantsDocument8 pagesMedical PlantsjhammyNo ratings yet

- Herbal Medicine What Is Herbal Medicine?Document4 pagesHerbal Medicine What Is Herbal Medicine?Tary RambeNo ratings yet

- Doh ApprovedDocument10 pagesDoh ApprovedAlliyah SalindoNo ratings yet

- Making Chinese Herbal Formulas Into Alcohol Extracts by Jake Paul Fratkin, OMDDocument7 pagesMaking Chinese Herbal Formulas Into Alcohol Extracts by Jake Paul Fratkin, OMDSkyNo ratings yet

- Nalda Gosling - Successful Herbal Remedies For Treating Numerous Common AilmentsDocument71 pagesNalda Gosling - Successful Herbal Remedies For Treating Numerous Common AilmentshascribdNo ratings yet

- Herbal Support DiabetesDocument3 pagesHerbal Support DiabetesShoshannah100% (1)

- Papaya Leaf Papaya TreeDocument4 pagesPapaya Leaf Papaya TreeRam NarayNo ratings yet

- Your Brain On Plants: Improve the Way You Think and Feel with Safe—and Proven—Medicinal Plants and HerbsFrom EverandYour Brain On Plants: Improve the Way You Think and Feel with Safe—and Proven—Medicinal Plants and HerbsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1)

- Andrographis PaniculataDocument34 pagesAndrographis Paniculatadeepak_143No ratings yet

- Philippine Traditional and Alternative MedicineDocument3 pagesPhilippine Traditional and Alternative MedicineMetchie Rico RafaelNo ratings yet

- Nourishing Herbal Infusions Ebookv2Document43 pagesNourishing Herbal Infusions Ebookv2Anything_Nottaken100% (13)

- Chamomile (Matricaria Recutita) As A Valuable Medicinal PlantDocument7 pagesChamomile (Matricaria Recutita) As A Valuable Medicinal PlantBrandon LeonNo ratings yet

- Medicinal Herbs and Remedies: A Beginner’s Guide to Learning Which Plants to Grow and Use in Healing: Natural Antibiotics & Alternative MedicineFrom EverandMedicinal Herbs and Remedies: A Beginner’s Guide to Learning Which Plants to Grow and Use in Healing: Natural Antibiotics & Alternative MedicineNo ratings yet

- Bloodroot: Sanguinaria CanadensisDocument6 pagesBloodroot: Sanguinaria Canadensiswangha666No ratings yet

- Advantages in Using Herbal MedicineDocument8 pagesAdvantages in Using Herbal MedicineTerence Cerbolles SerranoNo ratings yet

- Dosage AND Dosage Form in Herbal Medicine: Apt. Yohana Krisostoma Anduk Mbulang, M.FarmDocument23 pagesDosage AND Dosage Form in Herbal Medicine: Apt. Yohana Krisostoma Anduk Mbulang, M.FarmEdwin WonkayNo ratings yet

- Plants Used in Hepatoprotective Remedies in Traditional Indian MedicineDocument6 pagesPlants Used in Hepatoprotective Remedies in Traditional Indian Medicineprachichanyal1No ratings yet

- Herbal Healing & Natural Cures Book: A herbal medicine book covering herbalism & herbal recipes for vibrant health, herbal apothecary rituals, cleanses, baths, natural antibiotics & herbal remediesFrom EverandHerbal Healing & Natural Cures Book: A herbal medicine book covering herbalism & herbal recipes for vibrant health, herbal apothecary rituals, cleanses, baths, natural antibiotics & herbal remediesNo ratings yet

- Simbai Muchabaiwa Hit 400 ProposalDocument9 pagesSimbai Muchabaiwa Hit 400 ProposalsimbaiNo ratings yet

- Growing Wellness: A Complete Guide to 20 Plants That Promote Wellness & VitalityFrom EverandGrowing Wellness: A Complete Guide to 20 Plants That Promote Wellness & VitalityNo ratings yet

- Terapi Oxygen Pada Pasien Covd-19Document24 pagesTerapi Oxygen Pada Pasien Covd-19normamNo ratings yet

- Exercise On Word Formation 2 (Unit 2 - Advanced) : Tran Dai Nghia High School For The GiftedDocument3 pagesExercise On Word Formation 2 (Unit 2 - Advanced) : Tran Dai Nghia High School For The GiftedEveryonehateshiuzo 2.0No ratings yet

- For More Information: WWW - Kimiafarma.co - IdDocument2 pagesFor More Information: WWW - Kimiafarma.co - IdcucuNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kinerja Lab Per Pasien Pemeriksaan 2022-10-14 S - D 2022-10-14Document72 pagesLaporan Kinerja Lab Per Pasien Pemeriksaan 2022-10-14 S - D 2022-10-14LaboratoriumNo ratings yet

- Philippine Informal Reading Inventory - Silent Reading: (Antas NG Bilis Sa Pagbasa) (Antas NG Pang-Unawa)Document4 pagesPhilippine Informal Reading Inventory - Silent Reading: (Antas NG Bilis Sa Pagbasa) (Antas NG Pang-Unawa)bodenz_dvp100% (1)

- Record Keeping A Pocket Guide 005 343Document6 pagesRecord Keeping A Pocket Guide 005 343ryanbucoNo ratings yet

- C3IS Course HandbookDocument73 pagesC3IS Course HandbookFouzia HannounNo ratings yet

- Kelompok Tugas Farmakoterapi LanjutanDocument2 pagesKelompok Tugas Farmakoterapi LanjutanWahyu Mafrudin .ANo ratings yet

- Adrakha (Fresh), Sunthi (Dry)Document3 pagesAdrakha (Fresh), Sunthi (Dry)dssbNo ratings yet

- Materi TE 172Document48 pagesMateri TE 172susilo50% (2)

- HyWhite by ContiproDocument2 pagesHyWhite by Contipro61p2bjx5No ratings yet

- Jurnal No 3 (Learning Cycle 5E)Document7 pagesJurnal No 3 (Learning Cycle 5E)Alma SiwiNo ratings yet

- Gordons PerosDocument5 pagesGordons PerosDoneva Lyn MedinaNo ratings yet

- Normal Vital Signs and Flow RateDocument3 pagesNormal Vital Signs and Flow RaterojamierNo ratings yet

- Final Expense Color Cheat SheetDocument1 pageFinal Expense Color Cheat Sheetapi-622084072No ratings yet

- Measurement and Active Passive Control oDocument12 pagesMeasurement and Active Passive Control oJosé Antonio Ayala AguilarNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Academy Stars Flashcards © Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2017Document21 pagesLesson 1: Academy Stars Flashcards © Macmillan Publishers Limited, 2017KuIl PhạmNo ratings yet

- GMP 2024 Final - English - PDF 102607294Document30 pagesGMP 2024 Final - English - PDF 102607294ahmedzahi964No ratings yet

- Organizing Patient CareDocument18 pagesOrganizing Patient CareAqmarindaLailyaGhassani80% (5)

- Trombektomi Mekanikal Pada Stroke Iskemik Dengan Awitan Kurang Dari 6 JamDocument12 pagesTrombektomi Mekanikal Pada Stroke Iskemik Dengan Awitan Kurang Dari 6 JamYulinda MoteNo ratings yet

- Indigenous Health Knowledge Systems in The Philippines: A Literature Survey byDocument31 pagesIndigenous Health Knowledge Systems in The Philippines: A Literature Survey bykarl_poorNo ratings yet

- Medical Oxy Life Oxygen Concentrator 10lDocument12 pagesMedical Oxy Life Oxygen Concentrator 10lsoheil alizadehNo ratings yet

- Case Studies (Analytics) Dbn-2.Xlsx111Document42 pagesCase Studies (Analytics) Dbn-2.Xlsx111Ali HamzaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Nama Obat Paten A - Z 1Document6 pagesDaftar Nama Obat Paten A - Z 1didy putra wijayaNo ratings yet

- WK No. - (Month) 2022 SEPDC-CENTRAL - WEEKLY KPI - (Project Name) - REV. 02 (INDIVIDUAL)Document5 pagesWK No. - (Month) 2022 SEPDC-CENTRAL - WEEKLY KPI - (Project Name) - REV. 02 (INDIVIDUAL)Shafie ZubierNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Health Assessment in Nursing 3 Har CDR Edition Janet R WeberDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Health Assessment in Nursing 3 Har CDR Edition Janet R Weberexundateseller.mqr0ps100% (40)

- Purdue University Global Grade Report 1Document4 pagesPurdue University Global Grade Report 1api-529055115No ratings yet

- Chapter 03Document23 pagesChapter 03alqahtaniabdullah271No ratings yet

- ACJ Grievance Process For Health ComplaintsDocument3 pagesACJ Grievance Process For Health ComplaintsAllegheny JOB WatchNo ratings yet

- Bisoprolol NehaDocument16 pagesBisoprolol NehasadafNo ratings yet