Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dan Heisman 12 - Analisys and Evaluation

Dan Heisman 12 - Analisys and Evaluation

Uploaded by

Leandro SakOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dan Heisman 12 - Analisys and Evaluation

Dan Heisman 12 - Analisys and Evaluation

Uploaded by

Leandro SakCopyright:

Available Formats

Novice Nook

Analysis and Evaluation

Dan’s saying of the month: Your rating doesn't mean

anything. Your playing strength is the only thing that

matters. In the long run your rating will always follow

your playing strength.

Many players confuse the concepts of analysis and

evaluation. A definition of each might be:

Novice Nook Analysis is the process by which a player, usually

through a process of “I move here, he moves there”

Dan Heisman logic, reaches positions to evaluate in order to

determine the best move. A more general definition of

analysis is “the thinking process used to determine a

best move.” This contrasts to the strategic thinking

process, which is used to arrive at a plan, although

these two processes are not completely independent.

Analysis makes use of many skills such as deductive

logic and visualization.

Evaluation is the process of examining a position and

deciding which side is better, by how much, and

why (the “why” is usually the key to your plan). You

can consider evaluation to happen “after” each

candidate move is analyzed or, by the more general

definition of analysis, evaluation is just a part of

analysis. Evaluation requires experience; a talented

beginner is often good at analysis but less so at

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (1 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

evaluation (unless one side is way ahead).

Analysis is inherently dynamic, while evaluation - and

planning - are primarily static. A dynamic process

involves “mental” movement of the pieces, while a

static process works with a particular “unmoving”

board position. For example, a combination or a knight

maneuver is dynamic, while a bad pawn structure or an

open file is static (not that these cannot be changed,

but determining if a file is open only depends whether,

in a particular position, there are any pawns on it.)

When you analyze a position, you often have to

evaluate dozens of positions to compare the relative

merits of each. How you choose which moves to

analyze (candidate moves) is a big subject outside the

scope of this article (but an upcoming Novice Nook

called A Generic Thought Process will!); when to stop

analyzing and evaluate is discussed below.

This leads to a key point: When analyzing candidate

moves, how do you decide when an evaluation of a

foreseen position is required and meaningful?

The answer is the concept of quiescence. In most

positions, one cannot evaluate a position until it is

“quiet”; that is, all the most forcing moves, such as

checks, captures, and strong threats, have been

resolved. As a trivial example, it would be silly to

think, “I will capture his queen with my queen and that

is my best move since after that I will be up a queen”

when you have not analyzed his obvious recapture that

restores material equality! Only a young beginner

would do that in the hope his queen is not recaptured.

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (2 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

When should you stop your analysis because you

cannot reach a positive goal? This is complicated, but

for sacrificial lines you should usually abandon your

analysis as fruitless when the material sacrificed

becomes greater than the potential gain. At that point

it is not likely you will attain a reasonable goal, so the

sacrifice should be rejected. For example, if you are

conducting a mating attack you would not stop

analyzing after sacrificing a queen unless you are sure

that there is no possible mate in that line. On the other

hand, if you are analyzing a line where you sacrifice a

queen and all you might possibly win back is a pawn,

no further analysis is necessary even if there are more

checks, captures, and threats – analyzing the sacrifice

further is a waste of time. Of course if you find you do

get back more than your sacrificed material by force,

your goal is reached immediately and you have an

excellent candidate move!

However, you may still sacrifice even if you do not see

that you get all your material back and/or more. With

some sacrifices, your compensation may be long term,

such as your superior piece play, the opponent’s unsafe

King, or his badly wrecked pawn structure. You just

have to make sure the potential gain is greater than the

sacrifice. Since checkmate is greater than any sacrifice,

a sacrifice that you think may likely lead to mate, even

if you have no hope of calculating all the lines, is

always worth consideration. Further, some positions

have either unclear quiescence or such complexity you

cannot achieve quiescence – they still have to be

evaluated, even though doing so may require a “feel”

or “intuition” based on your experience in similar

positions.

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (3 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

When you analyze a position, you should select sets of

candidate (reasonable) moves using deductive logic,

visual perception, etc. If possible, consider and resolve

the all potential checks, captures, and threats for both

sides, and try for each to eventually arrive at a

quiescent position. This position is then evaluated

using the player’s best knowledge of positional

aspects: material, piece activity, king safety, pawn

structure, square control, etc.

You should do much of this for all candidate moves,

arriving at an evaluation of each for the purpose of

selecting the move you evaluate as best. Ideally, this

selection is done by performing a “minimax” of these

evaluations. Minimax is an artificial intelligence term

meaning you have to assume each side will choose his

best moves, which in turn is that player’s “highest”

evaluation. In many/most cases, a conscious

calculation of a minimax is not always necessary or

practical – with practice the process of best move

assumption and its effects becomes more intuitive

(qualitative) and not very quantitative.

There are many sources of possible error in this

process that can lead to selecting the wrong move. The

most common sources of error are listed below. The

player either:

1. Does not understand the process and stops his

selection after he has found what he thinks is a

reasonable move, but does not attempt to find the

best move;

2. Uses bad deductive logic and erroneously thinks

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (4 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

a particular sequence is likely to occur, when in

fact it likely would not;

3. Overlooks an opponent’s move, causing a tactical

error;

4. Makes a mistake in visualization and thus misses

a tactic or causes a misevaluation of the position,

5. Does not analyze until quiescence and thus

misses a tactic;

6. Uses bad time management and for various

reasons either plays too fast or too slow, the latter

resulting in time trouble where he has to play too

fast;

7. Selects a bad “plan” which he thinks will lead to

future good (or equal) positions but which in fact

leads to less favorable positions than expected;

and/or

8. Mis-evaluates the position and erroneously

selects the wrong move.

These help explain which methods of study improve

which aspect of the process.

Studying tactical problems helps you learn to use

deductive logic and visualization to create solutions. It

also increases one’s pattern recognition so that future

similar patterns can be recognized more quickly.

However, it does not help one learn to evaluate

positions, because by their nature tactical problems

have a solution (evaluation: I am up a piece, rook, or

have mate) and thus do not need to be “evaluated”.

Nevertheless, making a tactical mistake is so decisive

that studying tactics is the single most important non-

playing practice one can do. A few recent problem

books now includes positions that do not have tactical

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (5 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

solutions, and that keeps the reader “on their toes.”

At the other extreme, studying positional concepts

helps you evaluate a quiescent position better. If you

are playing good opponents and constantly

misevaluating the position, then your opponent’s

position will constantly improve as you both allow

certain variations to happen which are better and better

for him, because you think they are not (at least until

you realize you must have done something wrong!).

Interestingly, the mistake of missing a tactic is

characteristic of almost all beginner and most

intermediate games, while the latter mistake of

misevaluating a position is a critical factor in many

intermediate and advanced contests. The reason is that

stronger players often can play without a large tactical

miscalculation, but instead get “squeezed” by an

opponent who is evaluating slightly better.

Of course, you can study other things that improve

your chances of finding the correct move: general

principles in the opening and endgame, specific

opening and endgame positions, or books on planning.

But the player who wishes to improve his planning

skills should be warned: planning is not something you

consciously need to do every move based on a

tabulation of the strengths and weaknesses of each

side’s forces. I agree with ChessCafe.com columnist

GM Mark Dvoretsky, who wrote in his book Attack

and Defense, “In some books you can read that the

process of evaluating a position consists in isolating

and weighing up all the positional factors that play a

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (6 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

part in it. Nonsense! In actual fact, most of this task is

performed subconsciously. The art of evaluation lies in

understanding the essence of a position - identifying

the crucial problem (either positional or tactical) that

needs solving - sensing the right direction for our

investigations and detecting the desirability or

otherwise of a particular operation.” I think the reader

can determine from the last part of this quote that

Dvoretsky was discussing planning, and not just

evaluating a position after analysis.

It is interesting that there are many books on tactics,

fewer on planning and positional play, and almost

none exclusively on evaluation”. To be fair, most

books on planning have a sub-focus on evaluation. For

example, this type of book (like IM Jeremy Silman’s

excellent series) might ask, “What are both sides

strengths and weaknesses, and what kind of plan does

that suggest to you?”

A different way to approach this same question would

be to show a series of positions and ask, “Who is

better, why, and by how much?” Because this is so

difficult to do objectively, this kind of question often

leaves out the “…and by how much?” part. For tactical

positions, you can use a computer program’s estimate:

have the program analyze the position in parallel with

yours, and when you are finished compare your result

with its. Most importantly, compare your principal

variation (PV) – the one that is most likely to occur. If

you chose a move that is significantly worse than its,

you are also likely to have an erroneous evaluation!

Examples of Analysis and (Overall) Evaluation

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (7 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

The following examples give (summary) analysis and

evaluation for each position. Of course, the actual

process of performing the analysis and evaluation may

be somewhat lengthy!

In this well known “Is it

a back-rank mate?”

position it is White to

play.

Analysis: White is down

material so needs to look

for ways to get back in

the game. If he does

nothing he will surely

lose, so he looks for a back-rank mate, which is a

reasonable hope given the three pawns blocking in

the king in the classical back-rank mate setup. If

1.Rd8+ Rxd8?? 2.Rxd8+ Re8 3.Rxe8 is mate, so

1…Re8! is forced and White has nothing since the

Black rooks guard each other through the White

rook – a good pattern to remember!

Evaluation: Count the material at the end of the

critical line 1…Re8!: Black has three extra pawns –

this is such a large lead that smaller positional

considerations, if any, don’t matter too much. Since

1.Rd8+ is the only line to worry about and after

1…Re8 White has no mate, Black has an easy win.

The following position occurred in a recent club

game where I was Black against a 1900 player. After

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 Bg7 4.e4 d6 5.f3 O-O 6.Be3

c5!? 7.Nge2 Nc6 8.dxc6 dxc6 9.Qc2 what is Black’s

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (8 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

best move?

Analysis: Black has no

reasonable checks and

the capture 9…Nxe4

leads to little after either

recapture, so he should

look for a reasonable

threat and, if he does not

find one, he should just

develop. The most

interesting threats are

9…Nb4 and 9…Nd4. But notice that 9…Nb4 has

the additional follow-up that after the queen moves,

10…Nd3+ may lead to a discovered check if White

does not play 10.Qd2. But then after 9…Nb4

10.Qd2 Nd3+ 11.Kd1 Nxb2+ When looking ahead,

did you see that the queen was pinned and that this

was possible? 12.Kc2, Black wins yet another pawn

after 12…Nxc4 or 12…Qxd2+ followed by

13…Nxc4 as played in the game.

Evaluation: Count material at the end of the forced

line: After 13…Nxc4 Black is up two pawns and has

no noticeable weaknesses; White’s exposed king,

which would be a big detriment should the queens

still be on the board, may actually be somewhat a

benefit in the upcoming endgame, but is not nearly

enough to compensate for the loss of two pawns.

Therefore, Black is winning easily.

After 1.Nf3 d5 2.g3 Nc6 3.Bg2 e5 4.d3 Be6 5.O-O

Qd7 6.e4 d4 7.Nbd2 Bh3 who is better and why?

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (9 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

Analysis: Again, start by

looking at checks,

captures, and threats and,

if there are none, look for

a way to develop the

pieces, for example by

planning the thematic

“break” move f4. There

are no checks and the

two captures are 8.Nxe5

and 8.Bxh3. 8.Bxh3 looks questionable as the g2

square is weak, but it is always worth looking to see

if, say, 8…Qxh3 9.Ng5 traps the queen, which it

does not, so there is nothing to recommend it. And

8.Nxe5 does not look too promising, but you always

have to check these things out, and not stop just

because 8…Nxe5 seems to win a piece because the

position is not yet quiescent: 9.Qh5 double attacks,

and the knight cannot guard the bishop nor the

bishop the knight, so 9…Nxd3 or 9…Bxg2 looks

forced. But 9…Nxd3 10.Bxh3 attacks the queen

(followed by cxd3), and the main line 9…Bxg2

allows 10.Qxe5+ and then 10…Qe7 11. Qxe7+

Bxe7 12.Kxg2 or other Black moves allow 11.Kxg2,

so the surprising 8.Nxe5 is best, winning a pawn.

Evaluation: Count material: after the principal

variation starting with 8.Nxe5 White sneaks away

with a pawn and is left with a better position as well,

including an imposing kingside pawn majority that

will get rolling after a later f2-f4. The general rule is

that an evaluation of +one pawn is about the

dividing line between a theoretical win and a draw.

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (10 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

If the opponent has compensation for the pawn you

are not likely winning yet, but if he has no

compensation (or you have some!) then you are

winning.

How far do you need to see ahead?:

Analysis: Hmm.

Whoever gets to the open

file first has a big

advantage. Since the goal

is almost always to find

the best move, and not

necessarily to tell the

future (although

sometimes that is

necessary to find the best

move), here 1.Rd1 grabs the file and threatens to

penetrate to the 7th rank, so I can make this move

with no other calculation at all. This type of position

reminds me of the memorable answer a famous

player gave when asked how far he looks ahead:

“Only one move – the best one.” (Actually, I prefer,

“As far ahead as necessary!”).

Evaluation: Count material: even so far, but with the

prospect of possibly winning a pawn once the rook

gets to the 7th rank. Since the best move is obvious,

a detailed evaluation is not necessary since I don’t

have to compare this line with any other. However,

after I get to the 7th rank the Black pawns are weak,

but capturing them too soon gives Black the d-file

and the threat of a back-rank mate, so I am likely

winning but some care is required. I will figure out

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (11 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

what to play and whether it is a forced win when I

get there…

Funsy Finish:

In case you have not seen it, the shortest possible

stalemate: 1.e3 a5 2.Qh5 Ra6 3.Qxa5 h5 4.h4 Rah6

5.Qxc7 f6 6.Qxd7+ Kf7 7.Qxb7 Qd3 8.Qxb8 Qh7

9.Qxc8 Kg6 10.Qe6. Black never gets to make his

10th move!

Reader Question: “You

recommend playing at

least 2 "slow" games per

week for improvement.

But, for purposes of this

advice, how slow is

slow? G/30? G/120? I

realize, of course, that

playing as slowly as

possible is best, but

where's the dividing line (or dividing grey area) you

are thinking of?”

Answer: Good question. Most internet players think

that 30 5 is slow, but that is unlikely slow enough to

play "real" chess. You need a game slow enough so

that for most of the game you have time to consider

all your candidate moves as well as your opponent’s

possible replies that at least include his checks,

captures, and serious threats, to make sure you can

meet all of them. For the average OTB player G/90

is about the fastest, which might be roughly 60 10 on-

line, where there is some delay. But there is no

absolute; some people think faster than others and

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (12 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

Novice Nook

others can play real chess faster because of

experience. Many internet players are reluctant to

play slower than 30 5 so you might have to settle for

that as a "slow" game.

Copyright 2002 Dan Heisman. All rights reserved.

Dan teaches on the ICC as Phillytutor.

[The Chess Cafe Home Page] [Book Reviews] [Bulletin Board] [Columnists]

[Endgame Studies] [The Skittles Room] [Archives] [Inside Chess]

[Links] [Online Bookstore] [About The Chess Cafe] [Contact Us]

Copyright 2002 CyberCafes, LLC. All Rights Reserved.

"The Chess Cafe®" is a registered trademark of Russell Enterprises, Inc.

file:///C|/Cafe/heisman/heisman.htm (13 of 13) [01/14/2002 11:40:25 PM]

You might also like

- Communist States in The 20th Century 1nbsped 1447985273 9781447985273 CompressDocument408 pagesCommunist States in The 20th Century 1nbsped 1447985273 9781447985273 CompressR R100% (1)

- Evaluate Like A GrandmasterDocument132 pagesEvaluate Like A Grandmasterrjdimo98100% (1)

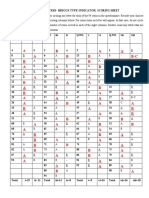

- MBTI Scoring SheetDocument1 pageMBTI Scoring SheetAditi100% (1)

- Haskins - A Practical Guide To Critical ThinkingDocument18 pagesHaskins - A Practical Guide To Critical ThinkingCiprian Hanga100% (1)

- Catawba Indians Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesCatawba Indians Lesson Planapi-301878021No ratings yet

- Novice Nook: Hand-Waving Is Worse Than Hope ChessDocument7 pagesNovice Nook: Hand-Waving Is Worse Than Hope ChessPera PericNo ratings yet

- CRTW FinalsDocument12 pagesCRTW FinalsMarianne GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinkinf & ReasoningDocument6 pagesCritical Thinkinf & ReasoningJhadeNo ratings yet

- CRWT FinalsDocument11 pagesCRWT FinalsKENSEY MOORE EBROLENo ratings yet

- Novice Nook: Principles of Analytical EfficiencyDocument5 pagesNovice Nook: Principles of Analytical EfficiencyPera Peric100% (1)

- Is Your Move Safe?: Dan HeismanDocument10 pagesIs Your Move Safe?: Dan Heismanseptembre2016No ratings yet

- LLT - Chapter 13 - Presentation Group 1&2Document11 pagesLLT - Chapter 13 - Presentation Group 1&2Greacia MayoNo ratings yet

- Critical ReadingDocument48 pagesCritical ReadingAirah SantiagoNo ratings yet

- ExcerptDocument10 pagesExcerptKatty UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- 02 - Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing CH 1Document7 pages02 - Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing CH 1MARIA ALEJANDRA JIMENEZ MEJIANo ratings yet

- CriticalThinking Value PDFDocument2 pagesCriticalThinking Value PDFAnaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Critical Thinking 1Document17 pages2 - Critical Thinking 1harkaranvirsingh358No ratings yet

- (Quarter 4 in English 9 - MODULE # 3) - Value Judgment, Critical Thinking and Call To ActionDocument8 pages(Quarter 4 in English 9 - MODULE # 3) - Value Judgment, Critical Thinking and Call To ActionMaria Buizon0% (1)

- CRWT111 FinalDocument7 pagesCRWT111 FinalReyna Lea MandaweNo ratings yet

- C T Value R: Ritical Hinking UbricDocument3 pagesC T Value R: Ritical Hinking Ubricclaudina silvaNo ratings yet

- O'Peer: by Jess H. Brewer 20 February 2012Document3 pagesO'Peer: by Jess H. Brewer 20 February 2012Kribaharan VasudevanNo ratings yet

- Text and Subtext: Scene AnalysisDocument3 pagesText and Subtext: Scene AnalysisAndrew MNo ratings yet

- Module in EthicsDocument2 pagesModule in EthicsRolando Cruzada Jr.No ratings yet

- Alkin SectionA RotatedDocument8 pagesAlkin SectionA RotatedJeffrey LedonNo ratings yet

- Finals crwt111Document13 pagesFinals crwt111rieehatesuNo ratings yet

- CCTM Session 1Document49 pagesCCTM Session 1Jaswinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Intelligence-How Do We Know The TRUTH?Document33 pagesAnalysis and Intelligence-How Do We Know The TRUTH?Melba Grullon100% (5)

- Chess Decision MakingDocument6 pagesChess Decision MakingsalihNo ratings yet

- PhilosophyDocument402 pagesPhilosophythvstm95No ratings yet

- Defining and Describing ReasonDocument9 pagesDefining and Describing ReasonInsaf Ali Farman AliNo ratings yet

- The Art of ReviewingDocument5 pagesThe Art of ReviewingVarga ZsófiNo ratings yet

- 5.1analyzing and Evaluating For DecidingDocument15 pages5.1analyzing and Evaluating For DecidingCesar Augusto Tabares LondoñoNo ratings yet

- D.03. Skill, Luck, Control, and Intentional Action (T. Nadelhoffer)Document12 pagesD.03. Skill, Luck, Control, and Intentional Action (T. Nadelhoffer)lanx ywekNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Skills of Critical ThinkingDocument11 pagesCognitive Skills of Critical ThinkingKlarisi VidalNo ratings yet

- Aacu Value Rubrics Core CompetenciesDocument10 pagesAacu Value Rubrics Core Competenciessonia reysNo ratings yet

- (NCM 203 LEC) Funda Midterms TRANSES PDFDocument11 pages(NCM 203 LEC) Funda Midterms TRANSES PDFedle maeNo ratings yet

- Ej 1143316Document4 pagesEj 1143316Victor CantuárioNo ratings yet

- A Practical Guide To Critical ThinkingDocument16 pagesA Practical Guide To Critical ThinkingAndy PurnomoNo ratings yet

- Virtue-As-A-Skill Cap 6Document25 pagesVirtue-As-A-Skill Cap 6Paulo Borges de Santana JuniorNo ratings yet

- Philo Additional ActsDocument3 pagesPhilo Additional ActsPatrick GarciaNo ratings yet

- Lecture - Thinking Like A Data Analyst - TaggedDocument16 pagesLecture - Thinking Like A Data Analyst - TaggedRajNo ratings yet

- Value Affect DriveDocument35 pagesValue Affect Drivepkat12No ratings yet

- Activity!: For A Strong Argument Reading Should Possible Barrier To Critical ThinkingDocument29 pagesActivity!: For A Strong Argument Reading Should Possible Barrier To Critical ThinkingJoannaNo ratings yet

- Hypotheses and Instrumental LogiciansDocument9 pagesHypotheses and Instrumental LogicianslimuviNo ratings yet

- Chap13 PDFDocument34 pagesChap13 PDFNadir HussainNo ratings yet

- 拉岡講座224 Transference and the Drive 移情與驅力Document6 pages拉岡講座224 Transference and the Drive 移情與驅力Chun-hsiung ChenNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Critical Thinking: Week 13Document28 pagesThe Nature of Critical Thinking: Week 13AC NaurgenNo ratings yet

- Critical ThinkingDocument8 pagesCritical ThinkingBK Blak100% (1)

- Critical Thinking For Testers: Why Don't People Think Well?Document33 pagesCritical Thinking For Testers: Why Don't People Think Well?hungbkpro90No ratings yet

- Reviewer's GuideDocument5 pagesReviewer's Guideamine.bouaineNo ratings yet

- Week 13 - The Nature of Critical ThinkingDocument5 pagesWeek 13 - The Nature of Critical ThinkingIRENE GARDONNo ratings yet

- 1.8 DECISION MAKING ANALYSIS at INTUITIONDocument23 pages1.8 DECISION MAKING ANALYSIS at INTUITIONEverlyn Cabacungan AustriaNo ratings yet

- CWRWT111 FinalsDocument6 pagesCWRWT111 FinalsAlexander Miguel SalazarNo ratings yet

- Week 3Document13 pagesWeek 3Arishragawendhra NagarajanNo ratings yet

- Trends L5 Critical ThinkingDocument41 pagesTrends L5 Critical ThinkingSherry GonzagaNo ratings yet

- 1192-1592201226511-HND MSCP W14 Reflection Performance of ProjectDocument15 pages1192-1592201226511-HND MSCP W14 Reflection Performance of ProjectBarath TharmartnamNo ratings yet

- April 8th - Session2 - What Is Critical ThinkingDocument16 pagesApril 8th - Session2 - What Is Critical ThinkingYanire Orjuela QuinaNo ratings yet

- Thinking, Fast and Slow (By Daniel Kahneman) : ArticleDocument3 pagesThinking, Fast and Slow (By Daniel Kahneman) : ArticleAdnan HalapaNo ratings yet

- The Art of Judgment: 10 Steps to Becoming a More Effective Decision-MakerFrom EverandThe Art of Judgment: 10 Steps to Becoming a More Effective Decision-MakerNo ratings yet

- Poster Presentation WCD: WyDocument1 pagePoster Presentation WCD: WyKopo Sentral MedikaNo ratings yet

- Secularism 1 PDFDocument5 pagesSecularism 1 PDFManish KumarNo ratings yet

- Osmoregulasi Pada Hewan AkuatikDocument6 pagesOsmoregulasi Pada Hewan AkuatikAde YantiNo ratings yet

- Brooks (1971) The Language of ParadoxDocument17 pagesBrooks (1971) The Language of ParadoxElisoSuxitashviliNo ratings yet

- (SAGE Series On Men and Masculinity) Harry Brod, Michael Kaufman - Theorizing Masculinities-SAGE Publications, Inc (1994)Document314 pages(SAGE Series On Men and Masculinity) Harry Brod, Michael Kaufman - Theorizing Masculinities-SAGE Publications, Inc (1994)Daniel Arias OsorioNo ratings yet

- Semiotic Analysis of An Advertising ImageDocument4 pagesSemiotic Analysis of An Advertising ImageArchana VijayNo ratings yet

- System Modelling (ESL)Document45 pagesSystem Modelling (ESL)xilvenkatNo ratings yet

- Solution Thermodynamics 2020Document49 pagesSolution Thermodynamics 2020Esha ChohanNo ratings yet

- School of Engineering and Architecture: Ateneo de Davao UniversityDocument3 pagesSchool of Engineering and Architecture: Ateneo de Davao UniversityJose Angelo GutierrezNo ratings yet

- 8 Grade - Workbook - Unit 6Document4 pages8 Grade - Workbook - Unit 6Esli AvendañoNo ratings yet

- Law of Contract: Prepared by Pn. Norazlina Abdul AzizDocument48 pagesLaw of Contract: Prepared by Pn. Norazlina Abdul AzizHairulanuar SuliNo ratings yet

- MCQs Basic Statistics 1Document6 pagesMCQs Basic Statistics 1secret student100% (1)

- Aristophanes 1Document590 pagesAristophanes 1Sean GrantNo ratings yet

- Sourabh Chandra - ResumeDocument4 pagesSourabh Chandra - ResumeNitin MahawarNo ratings yet

- Proteccion Agua de FPH-CDDocument25 pagesProteccion Agua de FPH-CDWilmer Solorzano ViedaNo ratings yet

- Research DesignDocument38 pagesResearch DesignhaslindaNo ratings yet

- Arab Abd Chinese Navigators in Malaysian Waters in About Ad 1500Document92 pagesArab Abd Chinese Navigators in Malaysian Waters in About Ad 1500Surinder ParmarNo ratings yet

- Yr 9 Speed Graphs PDFDocument0 pagesYr 9 Speed Graphs PDFDilini WijayasingheNo ratings yet

- Adi ReferenceDocument17 pagesAdi ReferenceKriszzamae FrofungaNo ratings yet

- Order of Succession - Muslim Code of The PHDocument37 pagesOrder of Succession - Muslim Code of The PHPARANG DISTRICT JailNo ratings yet

- Is Astrology A ScienceDocument2 pagesIs Astrology A SciencejasminnexNo ratings yet

- Digital Death (Missing Bits)Document48 pagesDigital Death (Missing Bits)Stacey Pitsillides100% (1)

- 9 Women of RizalDocument2 pages9 Women of RizalRizza LimNo ratings yet

- Principles of Agricultural Extension and Communication: Take IntoDocument12 pagesPrinciples of Agricultural Extension and Communication: Take IntoRheamar Angel MolinaNo ratings yet

- Cambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/23 October/November 2020Document18 pagesCambridge International AS & A Level: History 9389/23 October/November 2020SylvainNo ratings yet

- Grade 3 Paragraph Insert Words 2Document2 pagesGrade 3 Paragraph Insert Words 2anaya bilalNo ratings yet

- After Sales ServiceDocument4 pagesAfter Sales ServiceDan John KarikottuNo ratings yet